3.1. Morphological, Elemental and Structural Characterization

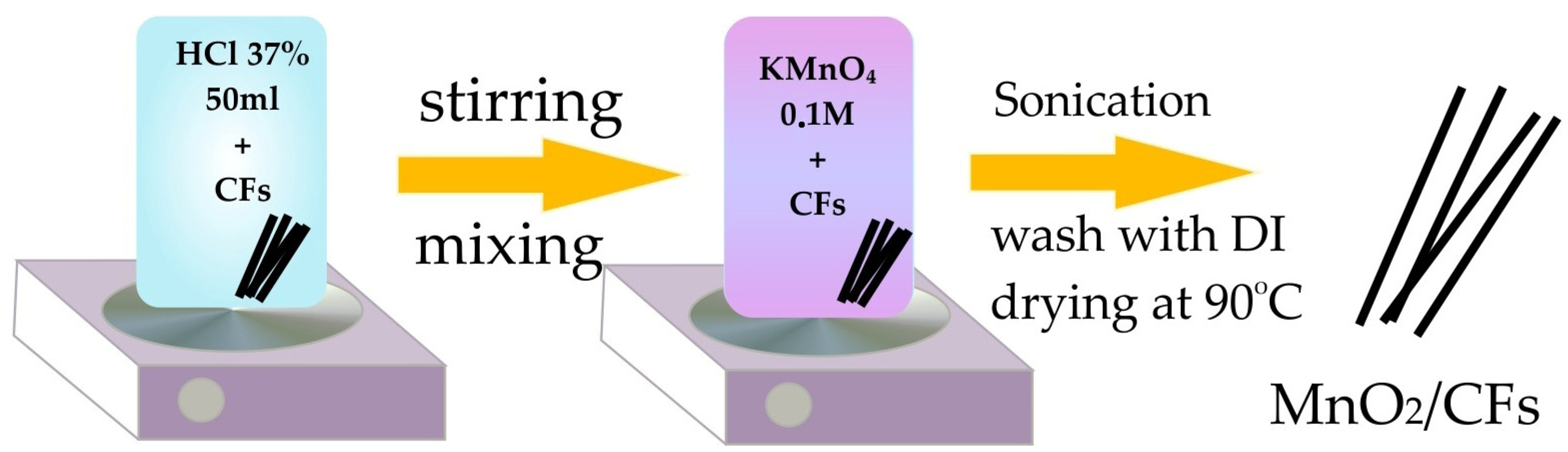

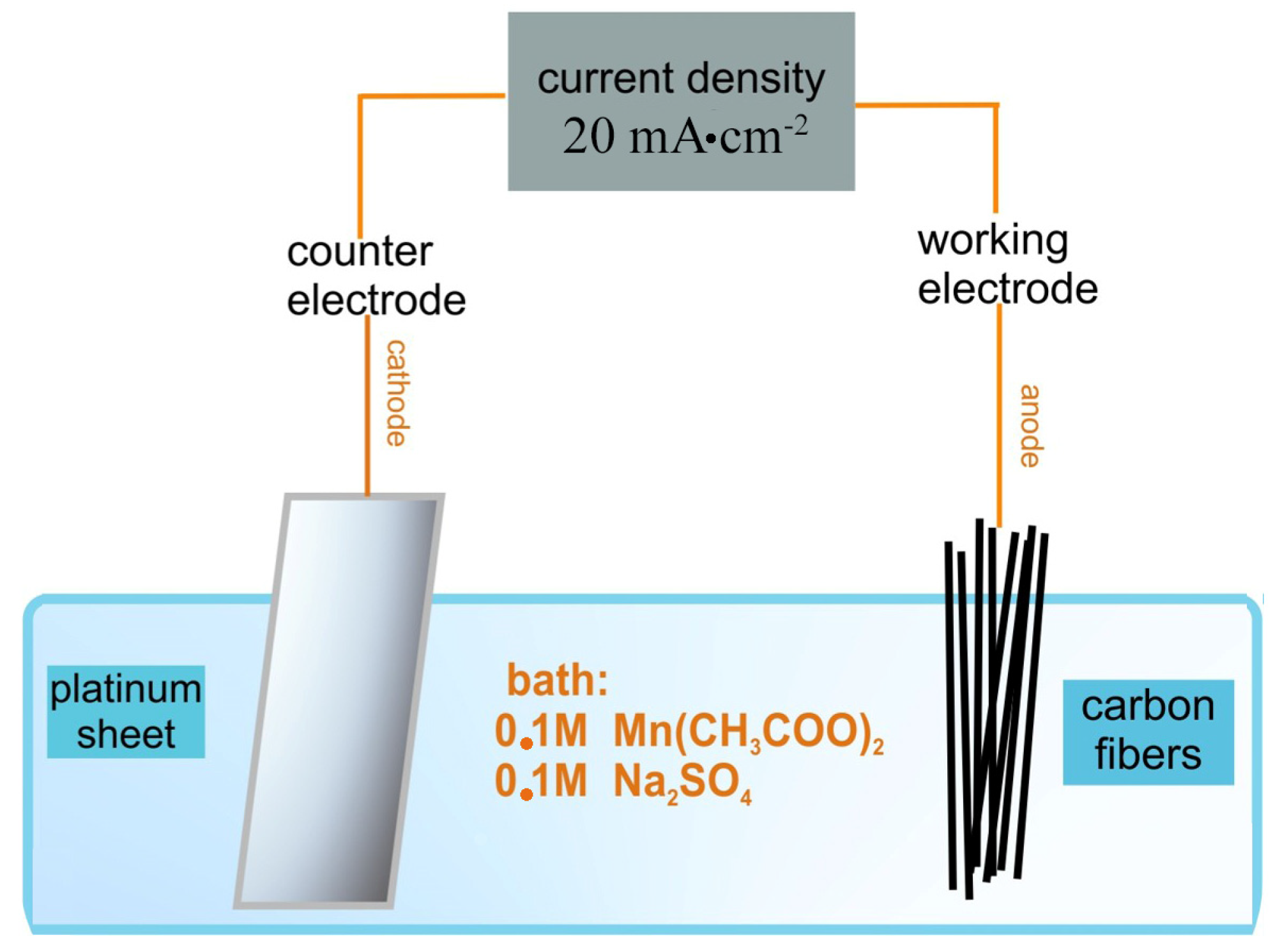

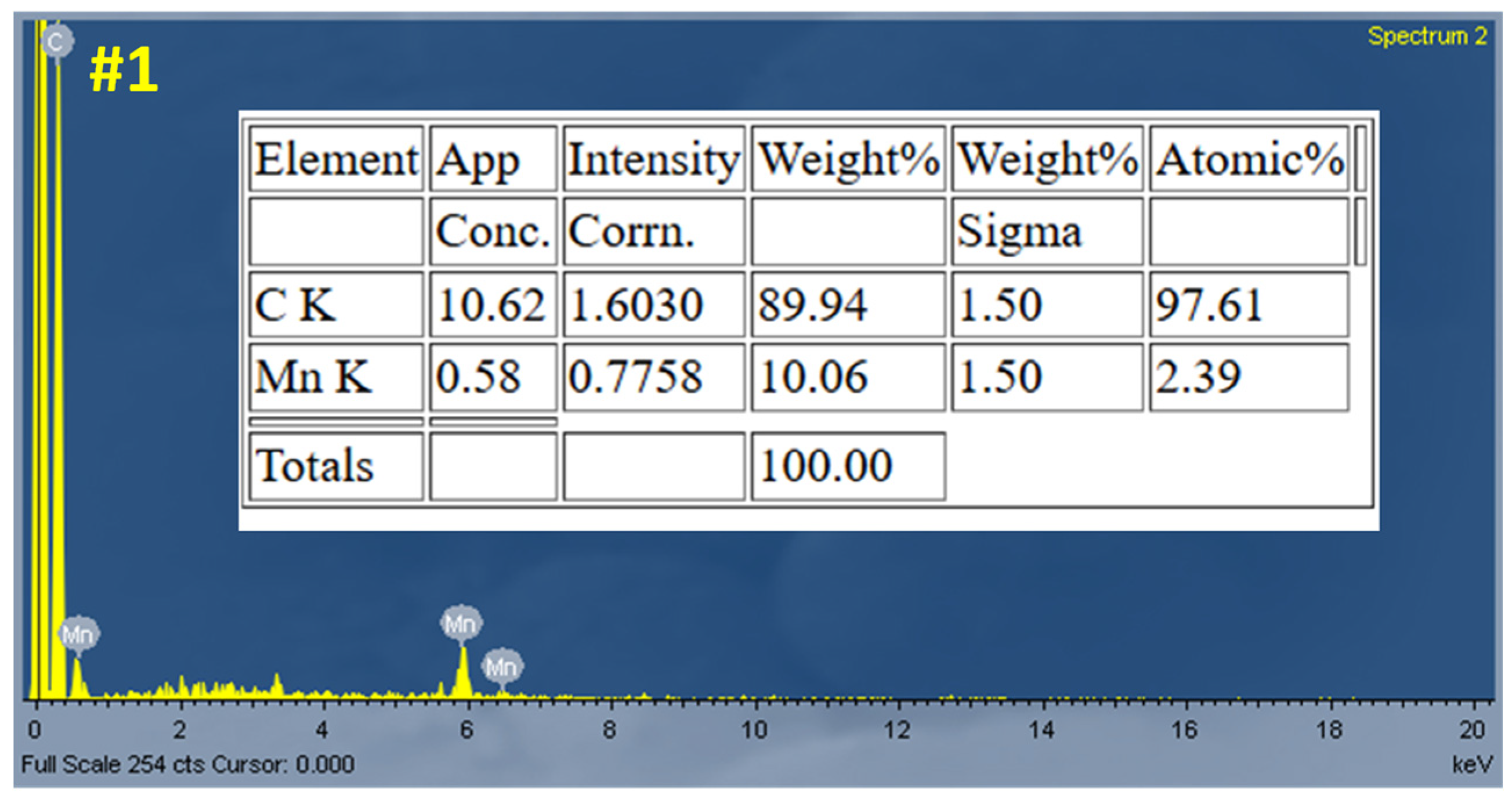

The final MnO2–CFs composite materials, synthesized via in situ redox deposition and electrochemical deposition methods prior to hydrogen exposure, were analyzed using EDS quantification to determine the manganese concentration, thereby evaluating the relative efficiency of each synthesis environment.

Theoretically, considering the redox deposition, a progressively increasing concentration of MnO

2 on the sample surface is expected as the contact time between the fibers and the reagent increases [

22]. This does not apply to the samples with reaction times of 2h and 6h respectively (

Table 3), which, due to inadvertent handling errors or uncontrolled variables during the setup, may have influenced the reproducibility. The pronounced decrease in Mn% observed between the repetitions b and c during electrochemical depletion could be the result of procedural inconsistencies during sample preparation or measurement.

Further characterization was conducted on the samples with the highest manganese

content from each synthesis method—specifically, the

in situ redox deposition sample with a reaction duration of 24 h (Sample #1) and the electrochemical deposition sample with a reaction time of 20 min at 28 °C (Sample #2) (

Table 4).

Based on the comparison of SEM/EDS results, conclusions can be drawn regarding the effectiveness of the in situ redox deposition method and electrodeposition synthesis for producing the desired material.

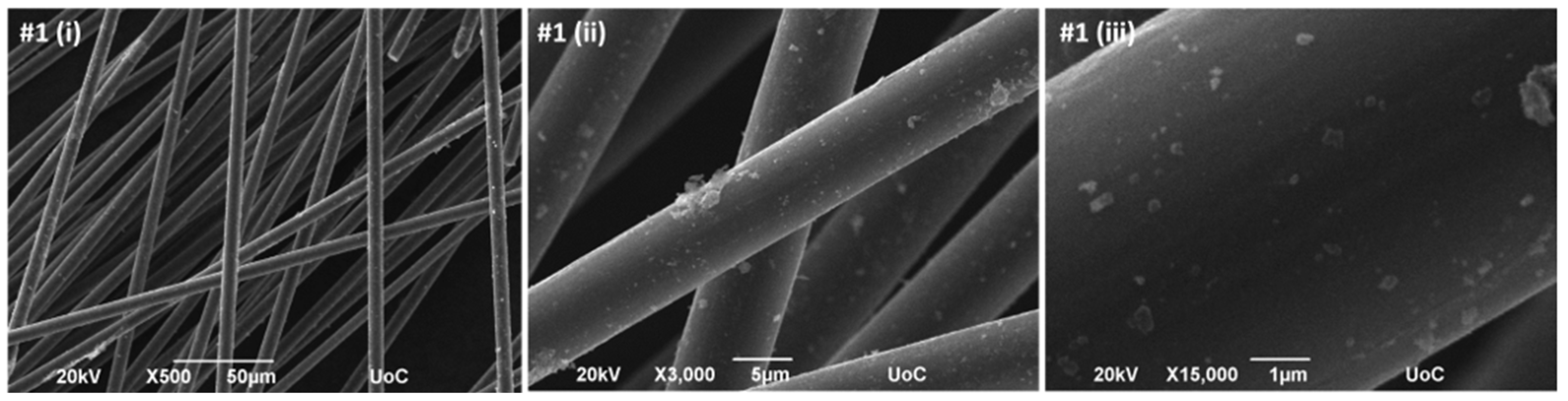

The SEM images of Sample #1 reveal dispersed bright speckled features across the carbon fiber surface (

Figure 3), corresponding to MnO

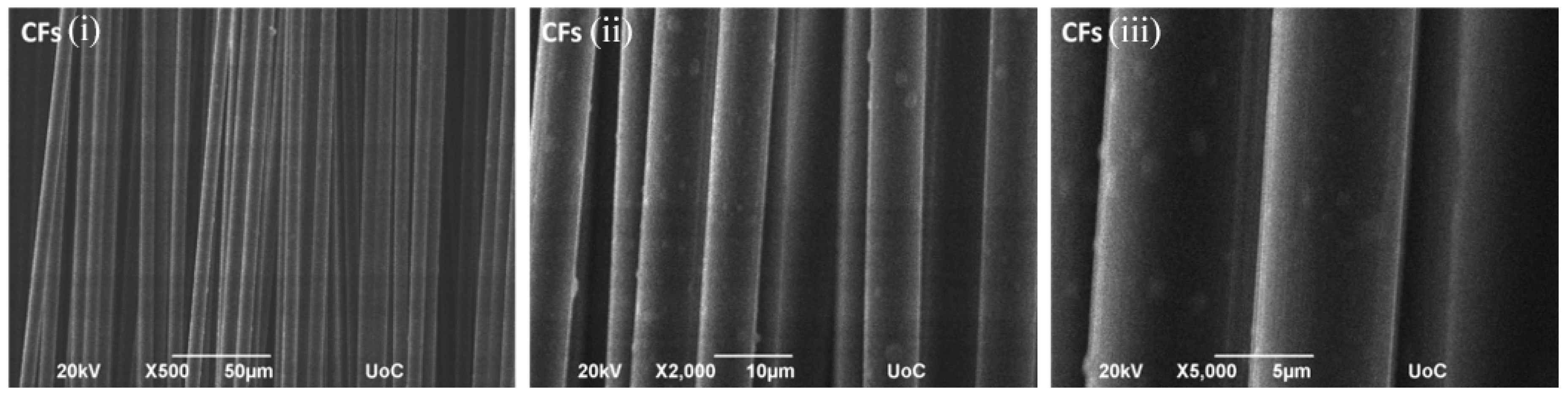

2 deposits. The distribution appears non-uniform, with areas of higher local concentration, while untreated CFs exhibit a relatively smooth and featureless surface (

Figure 4). The EDS results of Sample #1 (

Figure 5) confirm the presence of Mn on the fiber surface.

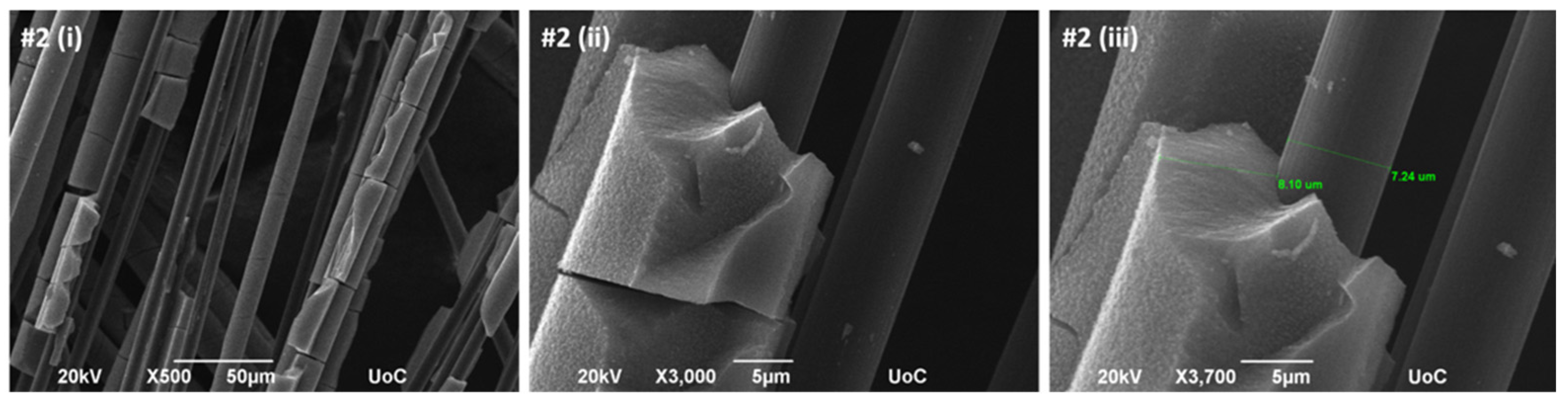

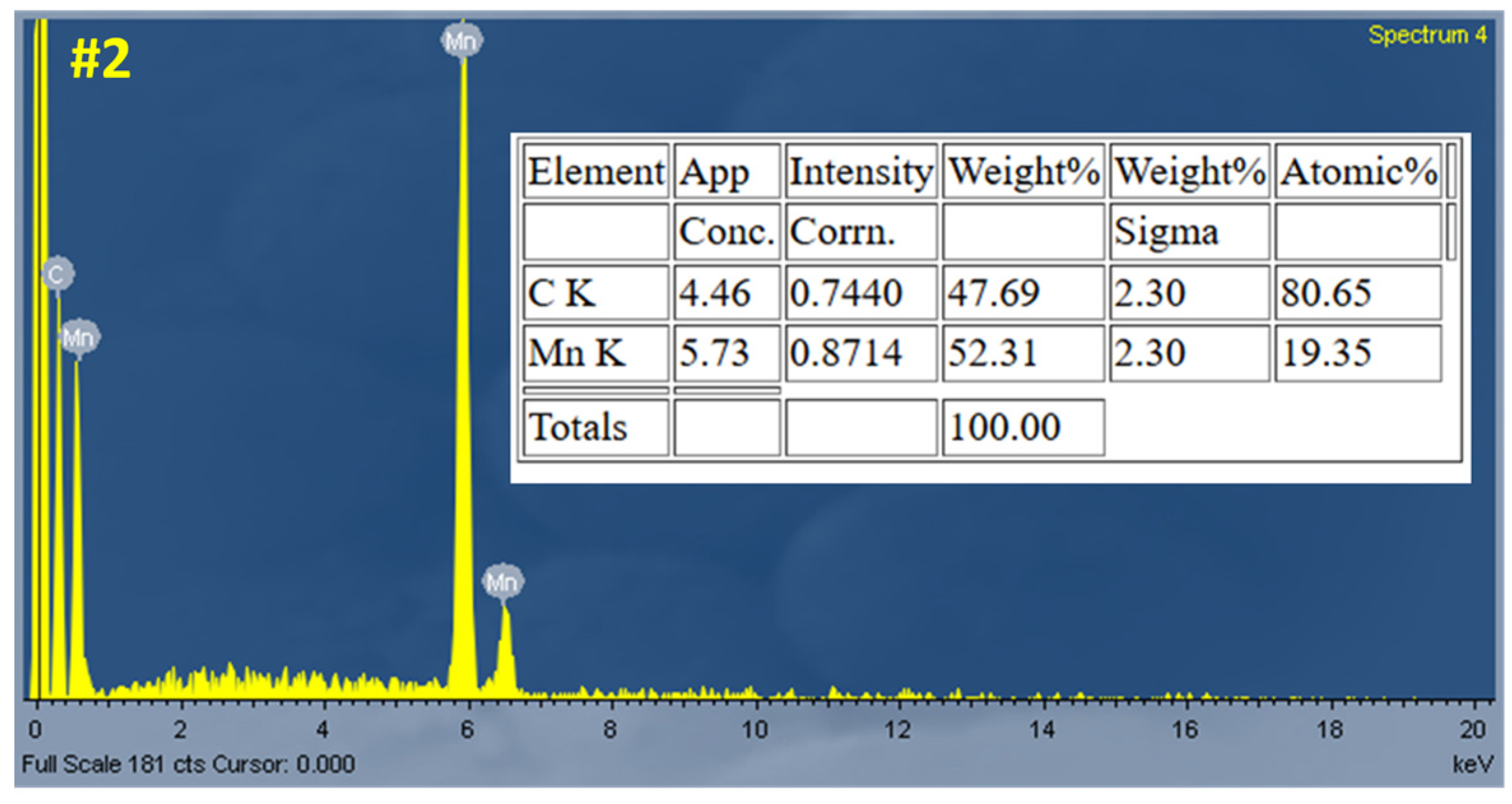

The electrochemically deposited MnO

2 layer is relatively dense and uniform, with an approximate thickness of 8.10 µm (

Figure 6). However, certain regions show thinner coverage or partial exposure of the underlying carbon fibers, indicating some degree of non-uniformity. The corresponding EDS analysis (

Figure 7) confirms the successful deposition, showing strong Mn peaks with minimal impurities.

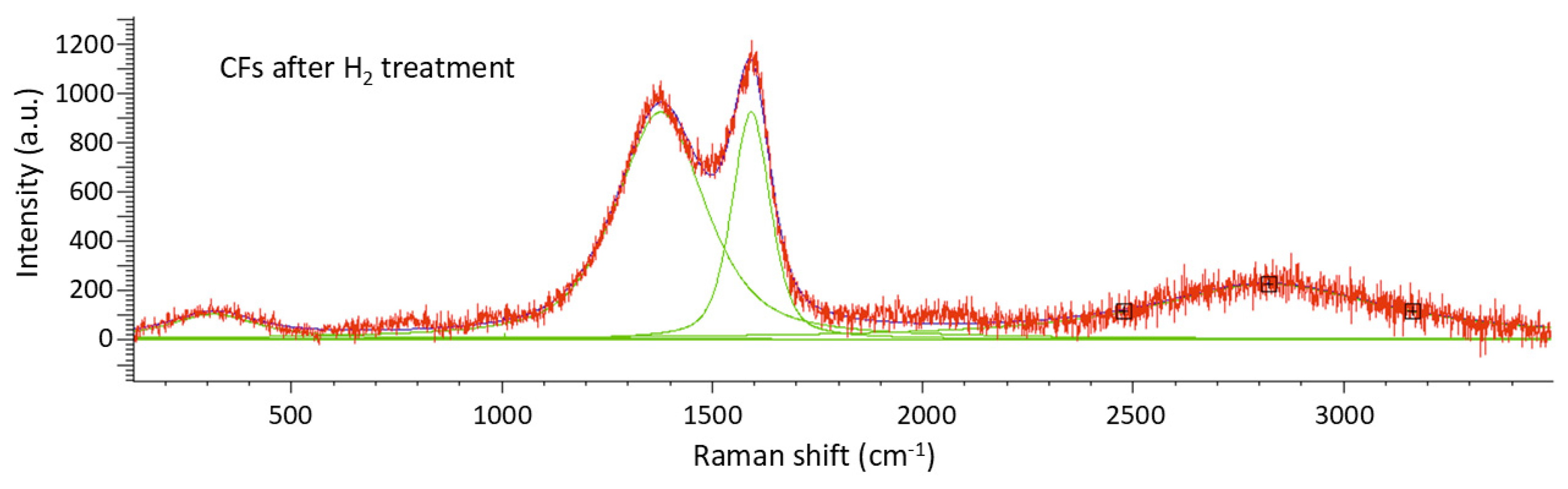

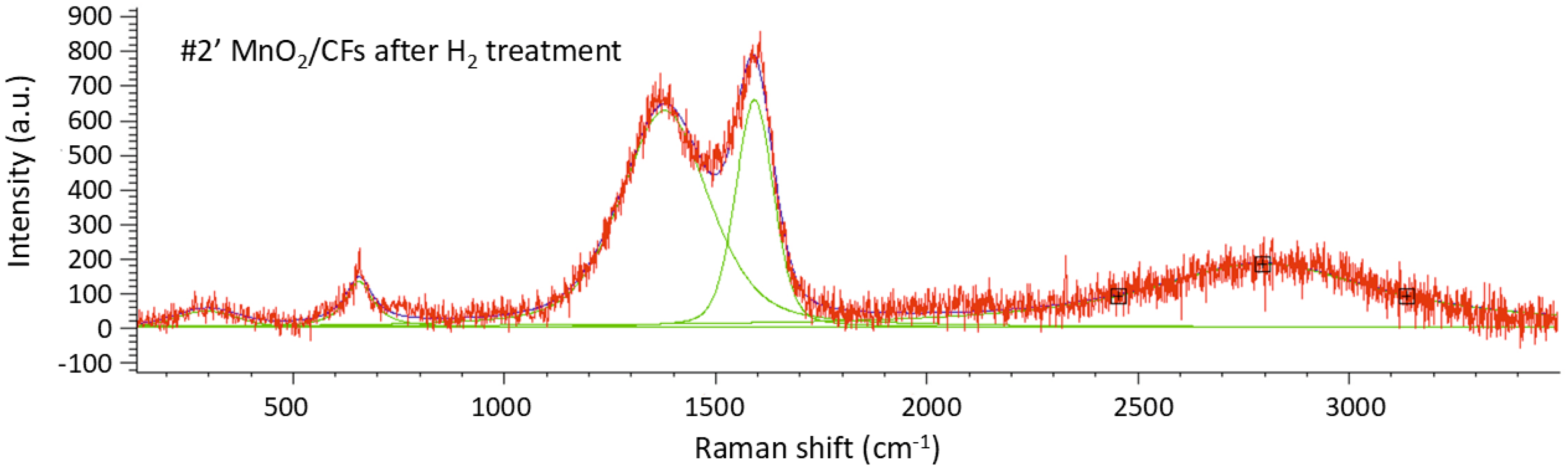

Raman spectroscopy reveals the characteristic D and G bands of carbon fibers at approximately 1350 cm

−1 and 1580 cm

−1, respectively, in plain activated carbon samples (

Figure 8,

Table 5) and the sample #2 composed electrochemically (

Figure 9,

Table 6). A comparative analysis between a MnO

2-free sample and a MnO

2-containing sample demonstrates the presence of a prominent phonon band at 650 cm

−1, attributed to Mn–O A

1g symmetric stretching vibrations, as well as a weaker band within the 200–500 cm

−1 range, corresponding to Mn–O bending vibrations. In general, the MnO

2-containing sample exhibits distinct peaks within the 200–800 cm

−1 region—characteristic of manganese dioxide—which are absent in the MnO

2-free sample. The ratio Id/Ig for sample #2 is equivalent to 2,51 using the peak areas while the sample number #9 exhibits Id/Ig = 2,38 both showcasing structural defects in the carbon structure. The structural defects were induced by acid treatment, conducted prior to deposition, which led to the formation of functional groups within the graphite matrix of the carbon fibers (CFs) [

23,

24]

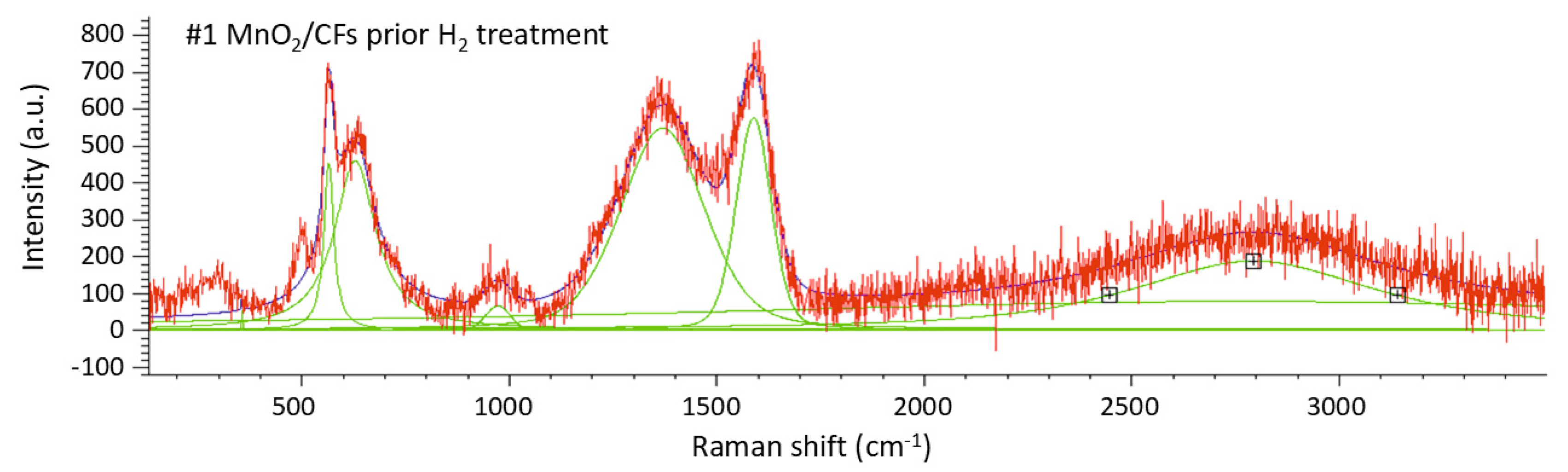

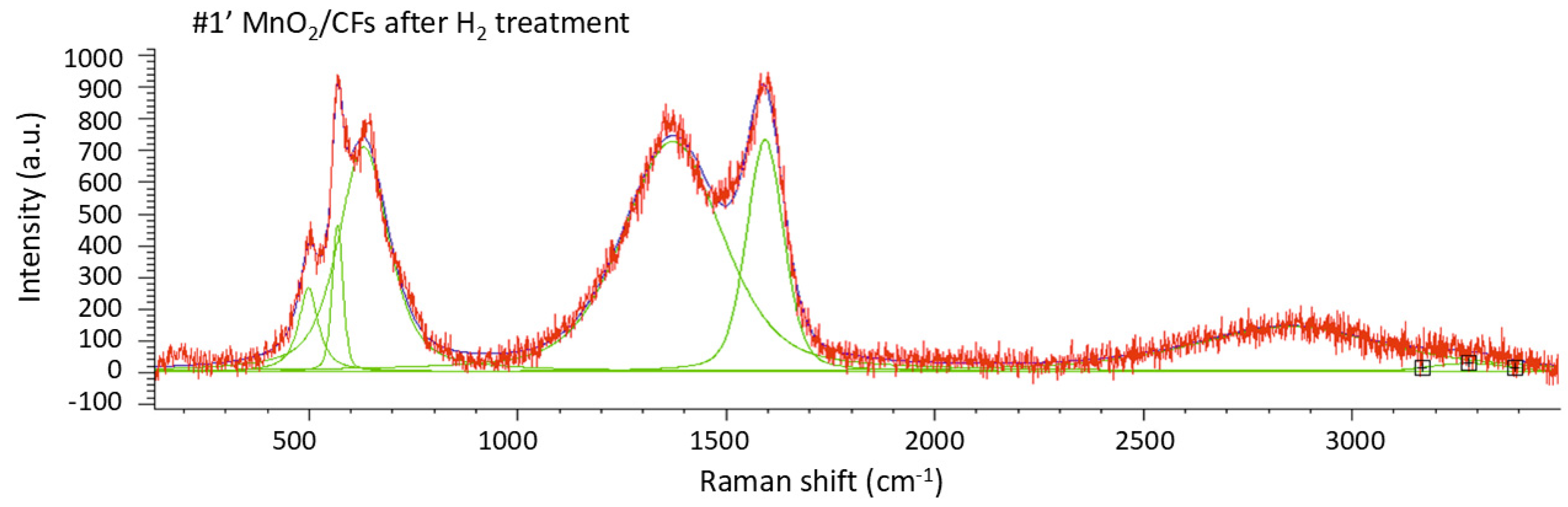

Raman spectroscopy was used to investigate the sample with a 24-hour chemical synthesis, both before (

Figure 10,

Table 7) and after exposure (

Figure 11,

Table 8) to hydrogen gas. The intensity ratio I

D/I

G for sample #1 is 2.37, calculated using the integrated areas of the respective peaks, while sample #1′ exhibits an I

D/I

G ratio of 2.81, indicating the presence of structural defects in the carbon framework in both cases.

The peaks observed in the range 200–800 cm

−1 in both spectra can be attributed to the presence of MnO

2. More specifically, for the sample prior to hydrogen exposure (

Figure 10,

Table 7), peaks 1 (~353 cm

−1), 2 (~562 cm

−1), 3 (~626 cm

−1), and 4 (~971 cm

−1) correspond to bending and twisting modes of Mn–O bonds (arising from Mn in different polymorphic forms). The highest of these four peaks (peak 4), which is absent in the spectrum of the hydrogen-exposed sample, may be associated with more stable or rigid MnO

2 structures, such as β-MnO

2. In the spectrum of the same material after hydrogen exposure (

Figure 11,

Table 8), the number of peaks within the 200–800 cm

−1 range is reduced, their intensity increases, and a shift toward higher wavenumbers is observed. This behavior may be attributed to a phase transformation of manganese and/or its partial reduction to lower oxidation states, such as the formation of MnO [

25,

26].

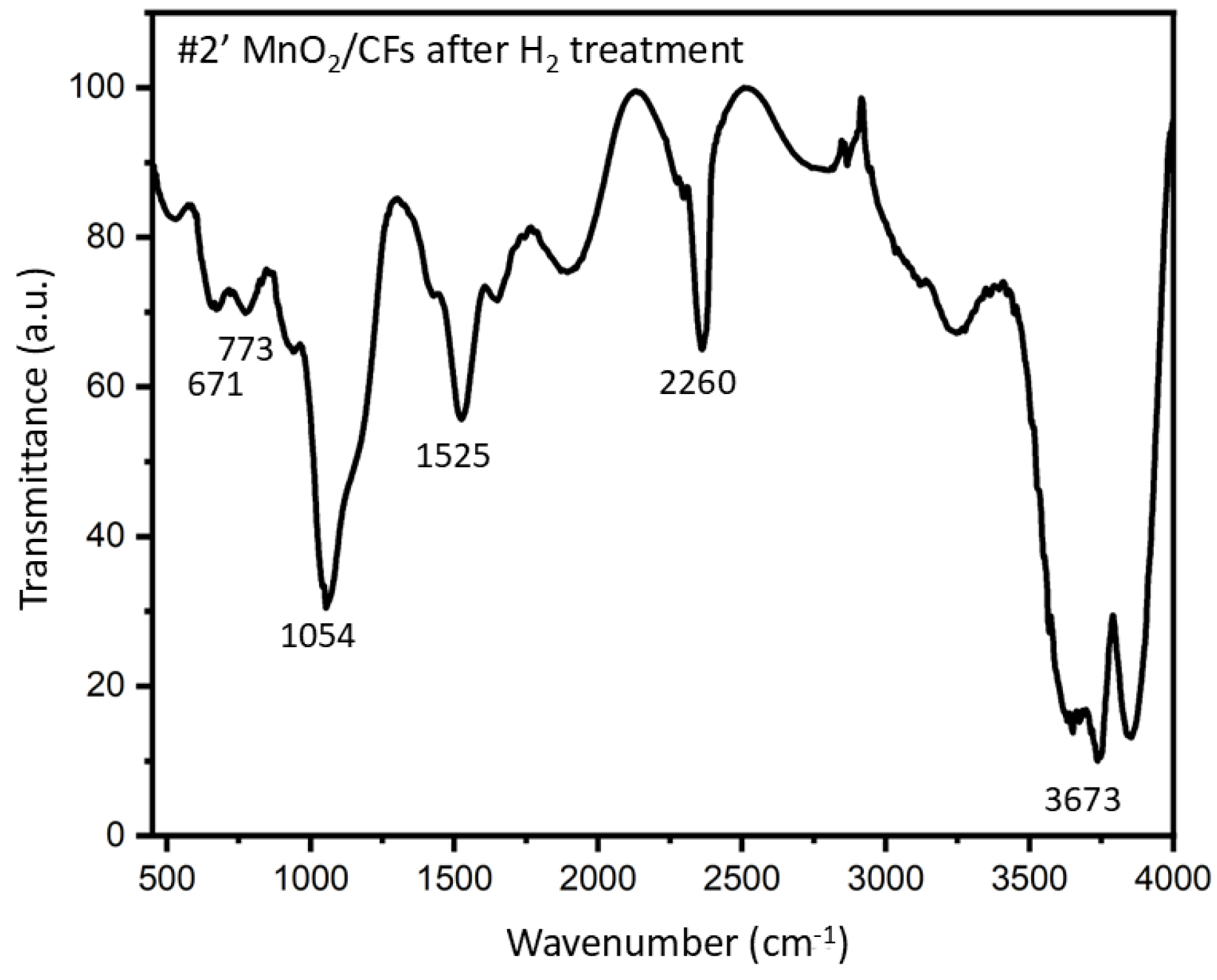

The structure of the synthesized fibers was further examined using FTIR spectroscopy. Specifically,

Figure 12 presents the FTIR spectrum of sample #2′, which was synthesized via electrochemical deposition for 20 minutes at 28 °C and subsequently exposed to H

2 treatment.

The broad band at 3500-3700 cm

−1, corresponding to O–H bending vibrations, indicates the presence of hydroxyl groups, which may be attributed to either adsorbed water or the partial reduction of MnO

2. The broad band at 2220-2260 cm

−1 is assigned to C≡N stretching vibration; CFs made from polyacrylonitrile often retain small amounts of nitrile (–C≡N) groups. The band observed at 1054 cm

−1 is likely associated with C–OH bending vibrations, suggesting surface oxidation of the carbon fibers. The peak at 1525 cm

−1 corresponds to C=C bending vibrations, characteristic of the carbon fiber backbone. Alternatively, it may arise from O–H bending involving oxygen atoms coordinated to manganese [

27,

28]. Expected Mn–O bending absorptions typically occur in the region of 400–700 cm

−1. In the recorded FTIR spectrum, several low-intensity peaks are indeed observed within this range, notably at 671 cm

−1, which supports the presence of manganese oxides. Additionally, the peak at 773 cm

−1 may be attributed to a characteristic absorption of manganese oxides with a tunnel-type structure [

29].

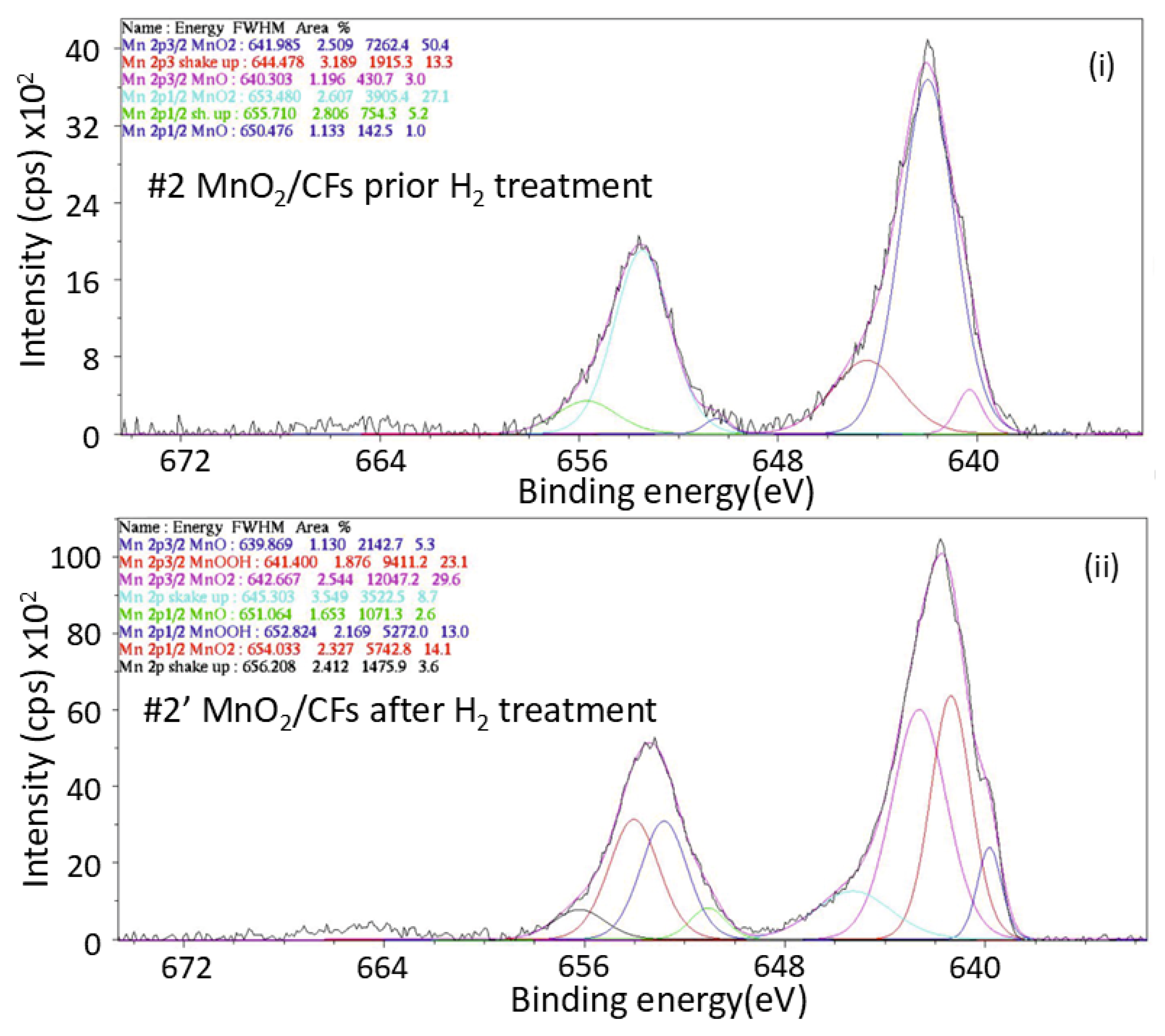

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of the MnO2/CFs produced electrochemically for 20min at 28℃ (sample #2) were used to determine the surface composition of the material before and after hydrogen exposure and to examine the oxidation state of Mn.

Figure 13.

XPS spectrum of Mn 2p orbital for: (i) sample #2 prior exposure to H2 treatment, and (ii) sample #2′ after exposure to H2 treatment; (electrochemical synthesis, t = 20 min, T = 28 ℃).

Figure 13.

XPS spectrum of Mn 2p orbital for: (i) sample #2 prior exposure to H2 treatment, and (ii) sample #2′ after exposure to H2 treatment; (electrochemical synthesis, t = 20 min, T = 28 ℃).

Based on the Mn 2p XPS spectra of Sample 2 prior to hydrogen exposure, the surface composition is predominantly manganese in the +4 oxidation state (Mn

4+), corresponding to MnO

2. This is evidenced by the characteristic Mn 2p

3/

2 and Mn 2p

1/

2 peaks observed at 641.985 eV and 653.480 eV, respectively (spin-energy difference of 11,495 eV), along with the presence of shake-up satellite features typically associated with Mn

4+ [

30]. Quantitative analysis indicates that Mn

4+ accounts for approximately 96% of the total manganese signal. A minor contribution from Mn

2+ (MnO) is also detected, represented by weaker peaks at 640.303 eV (2p

3/

2) and 650.476 eV (2p

1/

2), comprising about 4% of the surface Mn species.

Following hydrogen exposure, the Mn 2p spectrum reveals significant changes in the oxidation state distribution. New peaks appear at 639.869 eV (2p

3/

2) and 651.064 eV (2p

1/

2), corresponding to Mn

2+ species, now constituting approximately 7.9% of the manganese signal. Additionally, peaks at 641.400 eV (2p

3/

2) and 652.824 eV (2p

1/

2) are attributed to Mn

3+ species, which account for 36.1%. The proportion of Mn

4+ consequently decreases to 56%, indicating a partial surface reduction of MnO

2 upon hydrogen treatment. This suggests that not all Mn

4+ species participated in the hydrogen storage process. [

12,

31,

32]

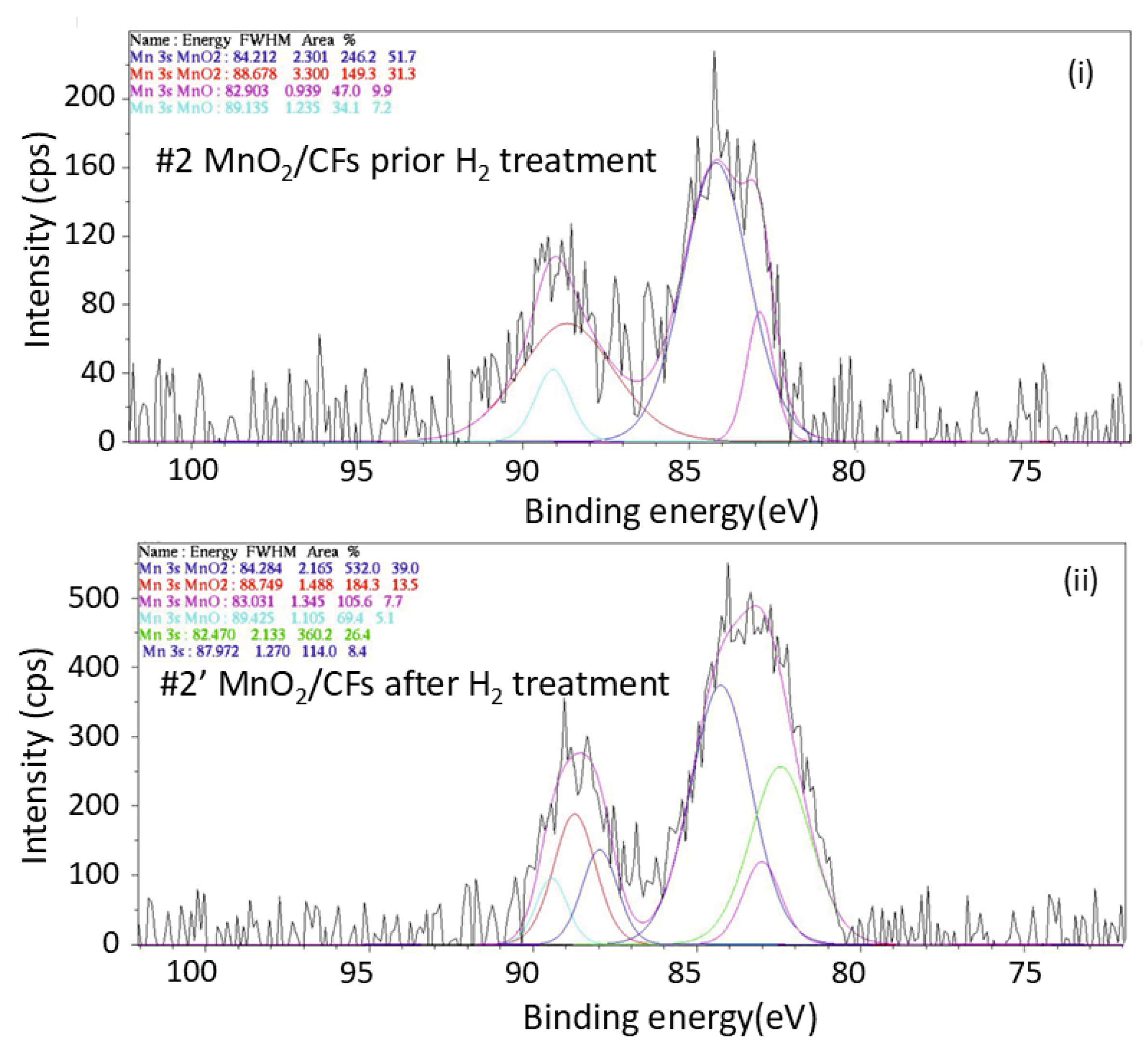

Figure 14.

XPS spectrum of Mn 3s orbital for: (i) sample #2 prior exposure to H2 treatment, and (ii) sample #2′ after exposure to H2 treatment; (electrochemical synthesis, t = 20 min, T = 28 ℃).

Figure 14.

XPS spectrum of Mn 3s orbital for: (i) sample #2 prior exposure to H2 treatment, and (ii) sample #2′ after exposure to H2 treatment; (electrochemical synthesis, t = 20 min, T = 28 ℃).

The comparison of Mn 3s XPS spectra between the two samples also confirms the partial reduction of MnO2 to lower oxidation states.

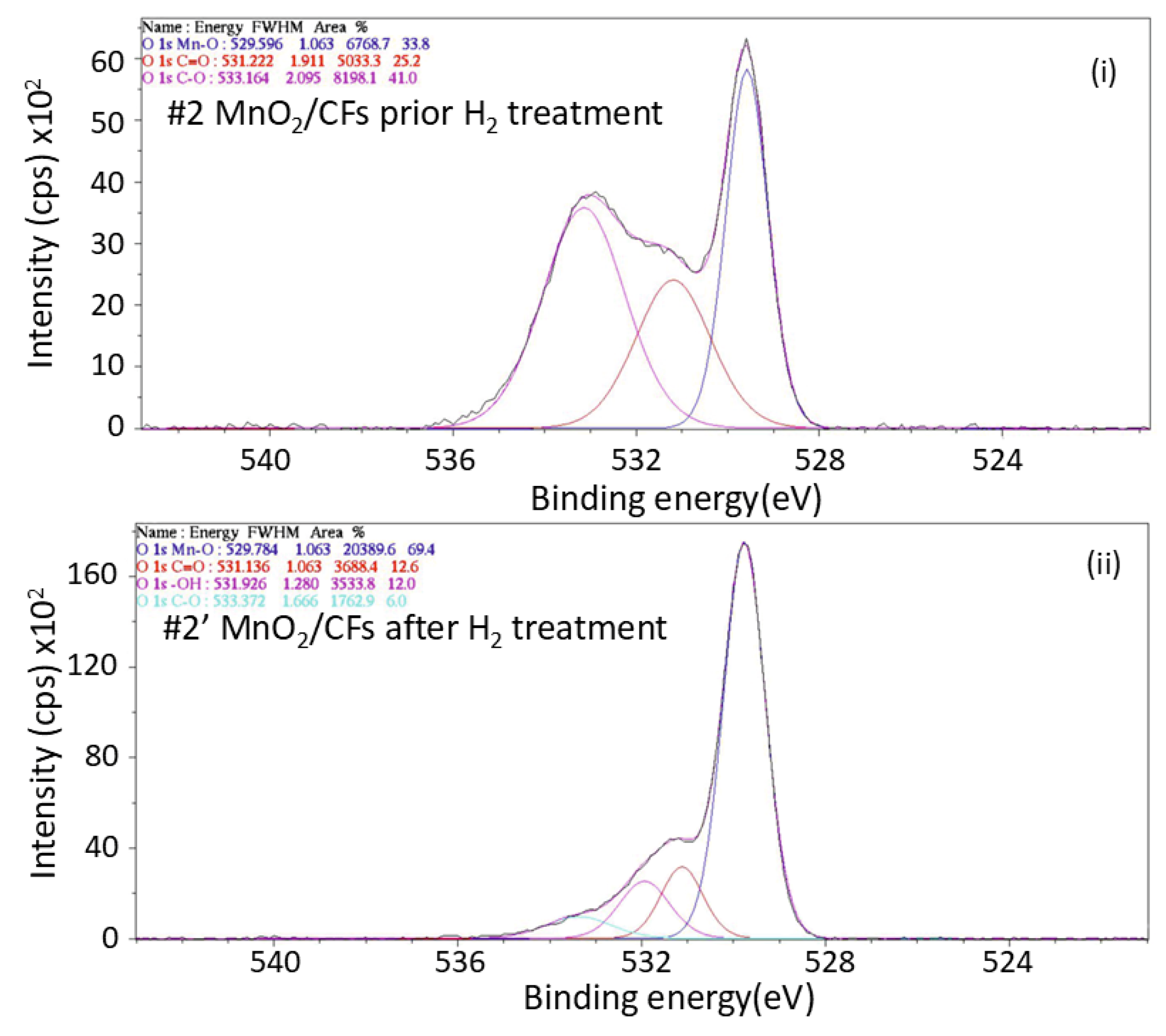

Figure 15.

XPS spectrum of the O 1s orbital for: (i) sample #2 prior exposure to H2 treatment, and (ii) sample #2′ after exposure to H2 treatment; (electrochemical synthesis, t = 20 min, T = 28 ℃).

Figure 15.

XPS spectrum of the O 1s orbital for: (i) sample #2 prior exposure to H2 treatment, and (ii) sample #2′ after exposure to H2 treatment; (electrochemical synthesis, t = 20 min, T = 28 ℃).

The O 1s XPS spectra of MnO

2/CFs provide information about the environment of O on the surface of the material before and after hydrogen exposure. In

Figure 17 the band at 529.56 eV (33,8%) is attributed to the lattice oxygen in metal oxides meaning Mn-O bonds within the MnO2 structure.The band at 531.222eV (25.2%) corresponds to carbonyl oxygen (C=O) groups which may appear due to the previous oxidation of the carbon surface while the band at 533.162eV reveals the presence of C-O bonds (41%) which may occur due to air exposure. The XPS spectrum of O 1s after H conditioning showcases the same bands increased in concentration (69,4%) for the Mn-O bond at 529.784 eV while the peaks for C=O at 531.136 eV and C-O at 533.372 eV decreace at 12.6% an 6.0%. This phenomenon suggests that the hydrogen treatment might have reacted with or removed some of these oxidized carbon species, possibly through hydrogenation reactions forming volatile products like water or hydrocarbons. The band at 531.926 eV corresponds to -OH meaning the formation of a hydrolized manganese oxide and proving the reduction of Mn [

14,

33,

34].

By integrating the data obtained from both the O 1s and Mn 2p XPS spectra, it is possible to quantify the percentage of MnO

2 present on the surface of the material before and after hydrogen conditioning, although the quantitative comparison of the two samples is not comparable due to uneven deposition of the material, further information will be addressed in the

Appendix A.

3.3. Thermal Behaviour Characterization-

The study of TGA diagrams of the synthesized MnO

2/CFs materials under inert and oxidative atmospheres provides insight into the fiber composition and their hydrogen adsorption capacity. The thermogravimetric curve reflects various mass changes occurring during the decomposition process. The inclusion of the first derivative (DTG) in the diagram aids in detecting subtle mass changes that may not be clearly visible in the standard mass loss curve as a function of temperature [

35].

TGA studies of carbon fibers in an oxidative environment (presence of O

2) show a gradual mass loss of 1.6% up to 450 °C, followed by a sharp mass reduction between 500–820 °C, attributed to oxidative activity on the fiber surface. In contrast, carbon fibers in an inert atmosphere (N

2), under the same heating rate (20 °C/min), exhibit minor mass changes, with a mass loss of approximately 1.2% between 200-450 °C [

36]. Manganese dioxide (MnO

2) in the presence of air (O

2) exhibits a mass change at T ≈ 250–400 °C due to the reaction:

and another mass change at 400–600 °C attributed to the transformation [

37]:

Under inert conditions (N

2), the same transformations occur but at higher temperatures, with a mass loss of approximately 9% at T ≈ 500–600 °C, and an additional ~3% mass loss at 700–800 °C, corresponding to the same respective conversions [

38].

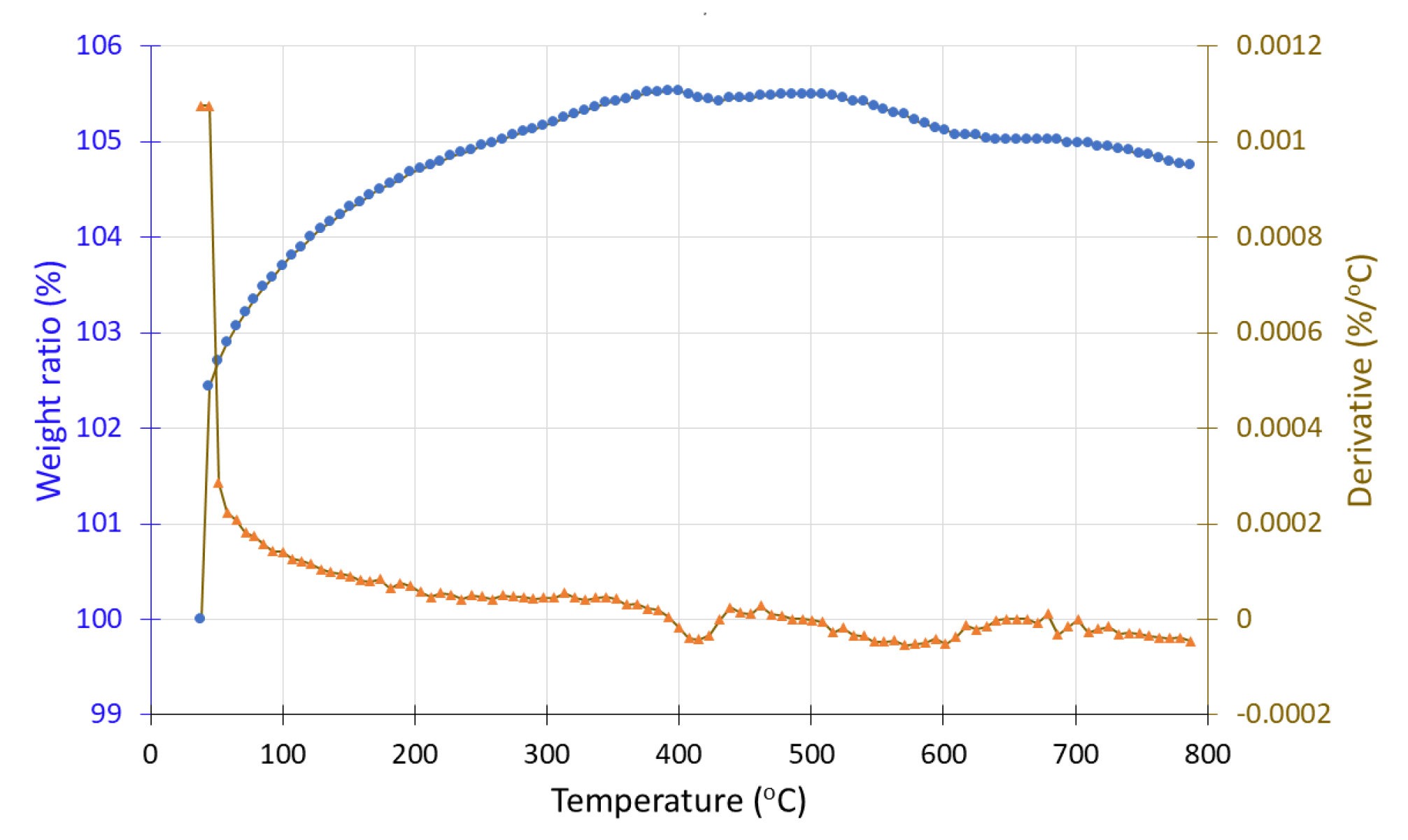

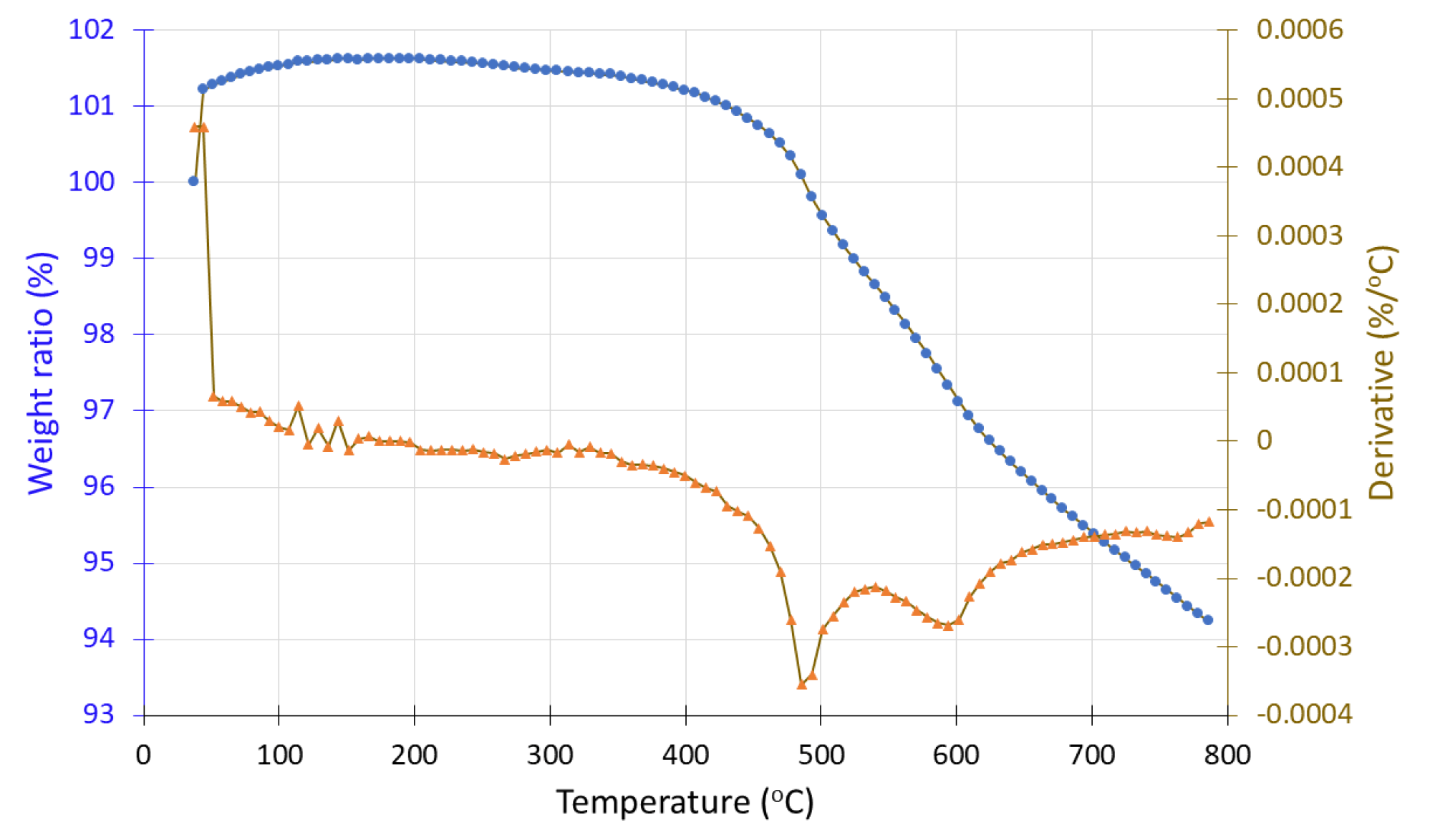

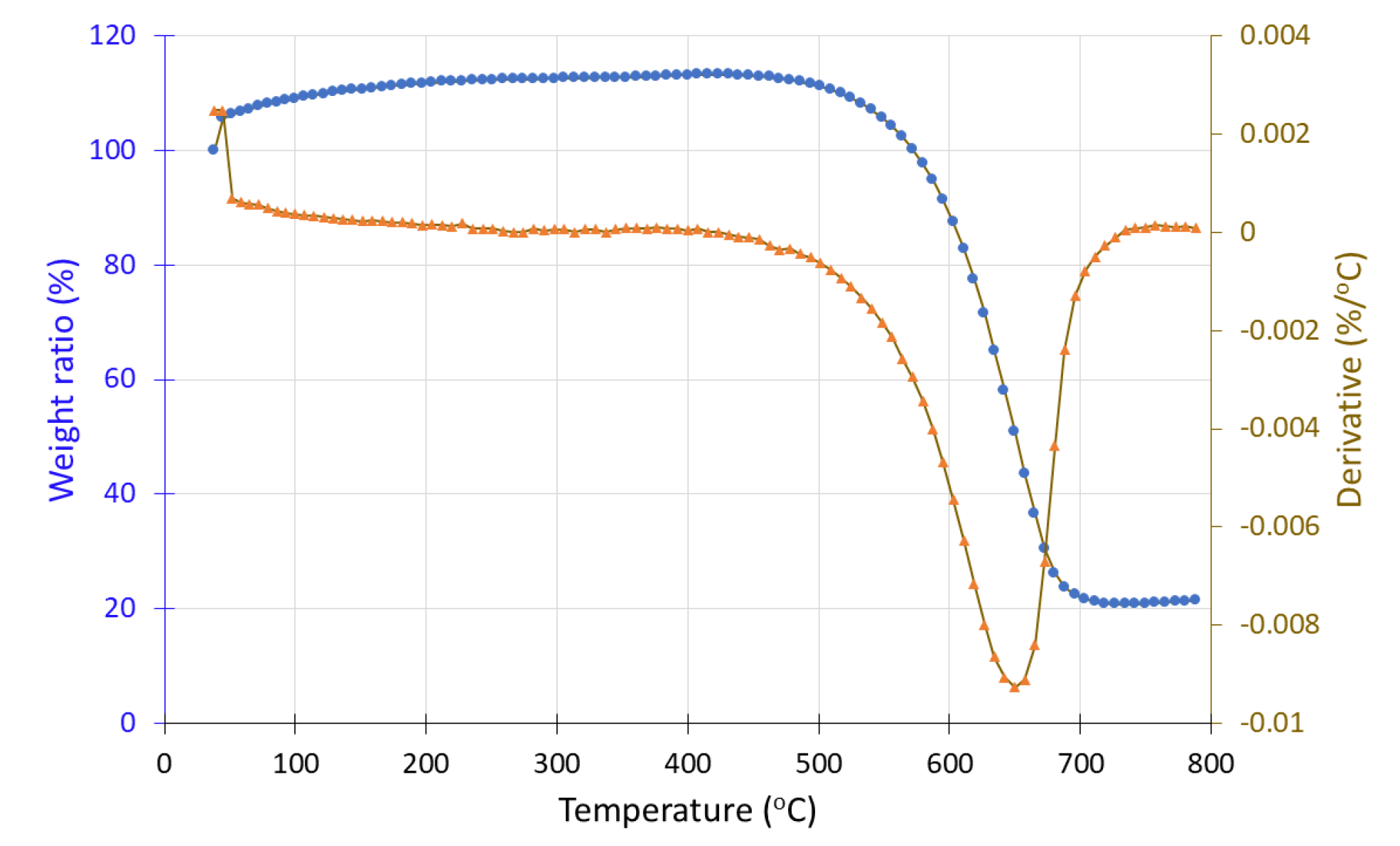

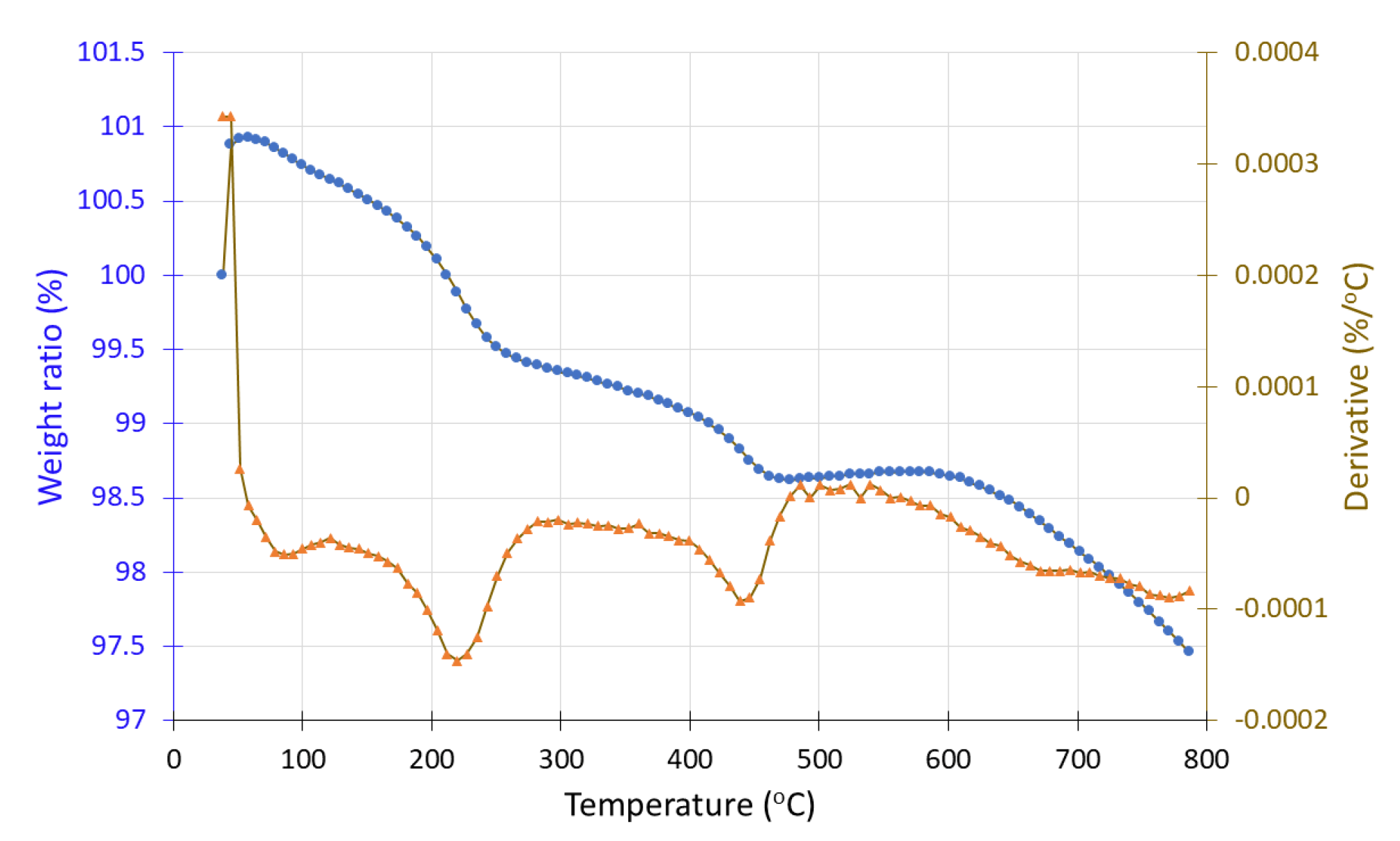

Both sample #1, before and sample #1′ after hydrogen exposure were studied under inert conditions (N2 atmosphere). In the case of sample #1, a mass increase from 100% to 105% is observed up to 500 °C, followed by a 1% mass loss. In contrast, the hydrogen-exposed sample (#1′) shows a continuous mass decrease from 400 °C to 800 °C. In DTG curve, a negative peak appears around 500 °C, corresponding to a mass loss of approximately 7%. A contradiction seems to exist because, according to the literature, MnO and Mn2O3, which are manganese oxide phases, are known to gain mass under inert conditions, and these forms should be present after hydrogen exposure (i.e., in sample #1′). However, the TGA results suggest its presence in the pre-exposure sample (#1), while the post-exposure sample (#1′) exhibits mass loss, indicative of MnO2 decomposition. This inconsistency may stem from an experimental error during sample handling, sampling procedures, or during the hydrogen exposure process.

Figure 16.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve of sample #1 (in situ redox deposition) before H2 treatment showing the weight loss (•) and the derivative (▲) as a function of temperature under inert atmosphere.

Figure 16.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve of sample #1 (in situ redox deposition) before H2 treatment showing the weight loss (•) and the derivative (▲) as a function of temperature under inert atmosphere.

Figure 17.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve of sample #1′ (in situ redox deposition) after H2 treatment showing the weight loss (•) and the derivative (▲) as a function of temperature under inert atmosphere.

Figure 17.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve of sample #1′ (in situ redox deposition) after H2 treatment showing the weight loss (•) and the derivative (▲) as a function of temperature under inert atmosphere.

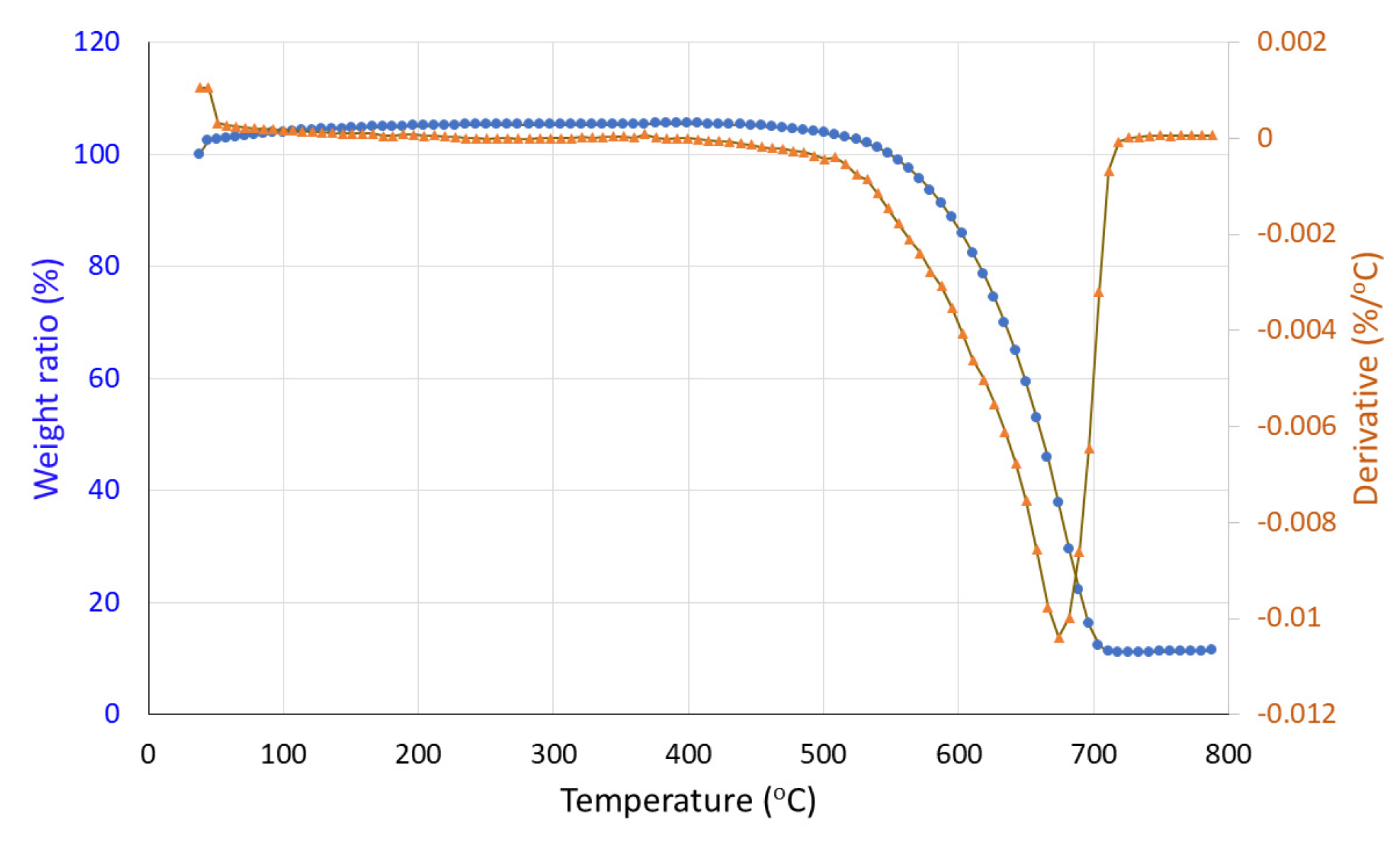

Samples #2 and #2′, before and after hydrogen exposure respectively, were analyzed under both inert (N

2) and oxidizing (O

2) atmospheres. In the TGA spectrum of sample #2, initial thermal stability is observed up to 500 °C, followed by a sharp mass loss of approximately 87%, reaching a plateau at 700 °C (

Figure 18). Beyond this temperature, the residual mass stabilizes at 13%. Comparing these results with known TGA profiles of pure carbon fibers suggests that the remaining mass likely corresponds to the presence of MnO

2 or other impurities. Weight loss in oxidizing environment may be attribued to the total decomposition of carbon fibers to gas CO

2 which takes place at 400-600 °C. Similarly, in the hydrogen-treated sample (#2′), thermal stability is also maintained up to 500 °C, followed by a sharp mass loss of around 75%, resulting in a final residual mass of approximately 25% (

Figure 19).The hydrogen treated sample is consisted of a bigger percent of MnO and MnOOH which are the reduction products of MnO

2 Thus, in the hydrogen-treated sample, an increase of about 12% in residual mass is observed. This increase may be attributed to MnO

2 transformations upon reduction, leading to the formation of manganese oxides with higher thermal stability and greater residual mass.

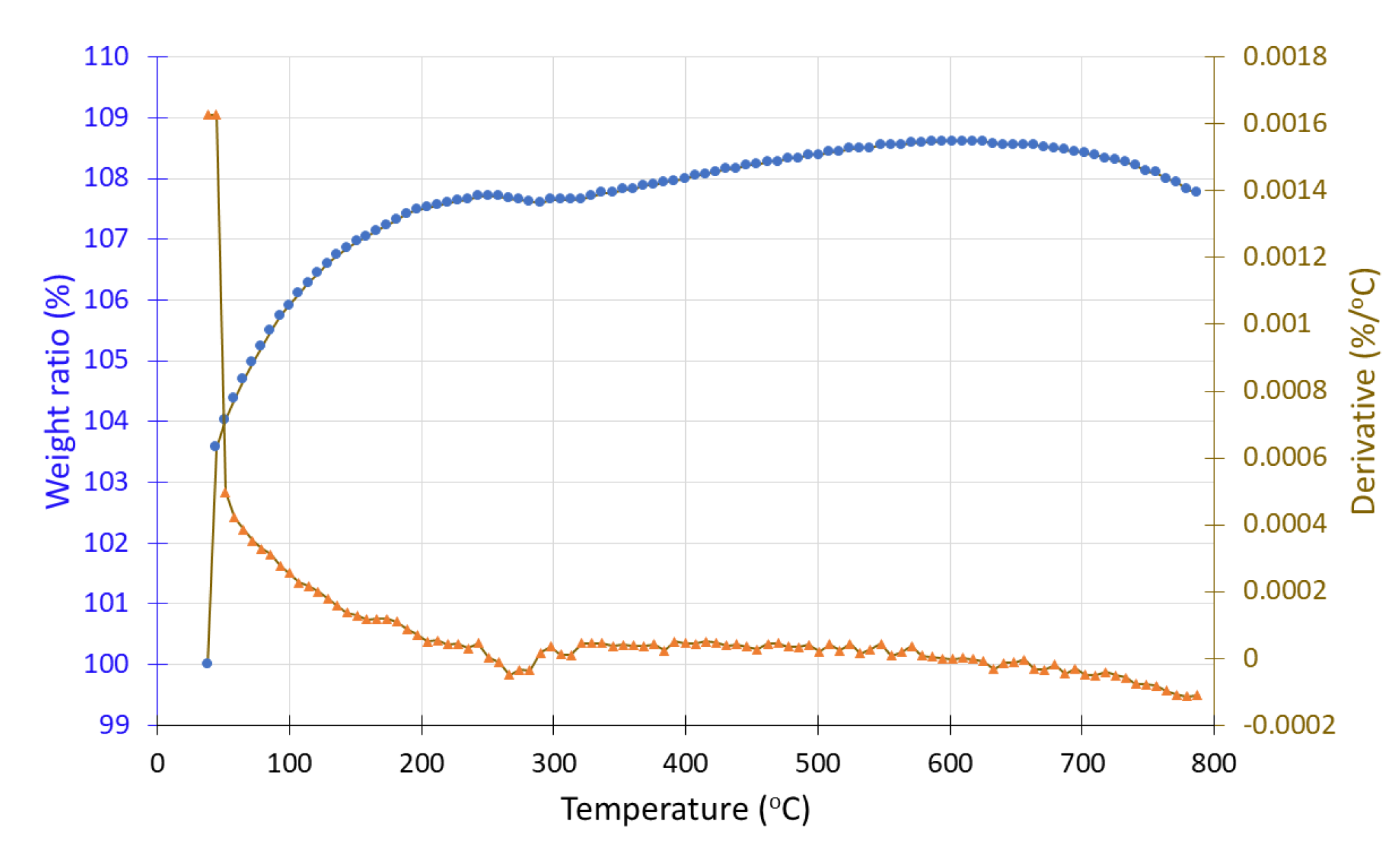

Under inert conditions (N

2), we observe the weight change attributed mainly on the behaviour of the deposited Mn oxides on the surface of CFs as the carbon fibers do not decompose under an inert atmosphere. More specifically, sample #2 exhibits a slight mass loss of approximately 0.5% up to 130 °C, with a DTG minimum peak at 70 °C (

Figure 20). Between 150–300 °C, a gradual 0.5% mass decrease is observed, with a DTG peak at 250 °C, consistent with the typical TGA behavior of carbon fibers. In the range of 350–500 °C, a minor additional mass loss may be attributed to the conversion of MnO

2 to Mn

2O

3 which occurs due to high temperature exposure and releases gas O

2.

In contrast, sample #2′, after exposure to hydrogen, shows a gradual mass increase from 100% to 108% with rising temperature, a behavior that aligns with TGA data for MnO and Mn

2O

3 phases, which are known to undergo mass gain in inert environments due to their thermal oxidation characteristics [

38].

Figure 21.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve of sample #2′ (electrochemical deposition) after H2 treatment showing the weight loss (•) and the derivative (▲) as a function of temperature under inert atmosphere.

Figure 21.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curve of sample #2′ (electrochemical deposition) after H2 treatment showing the weight loss (•) and the derivative (▲) as a function of temperature under inert atmosphere.

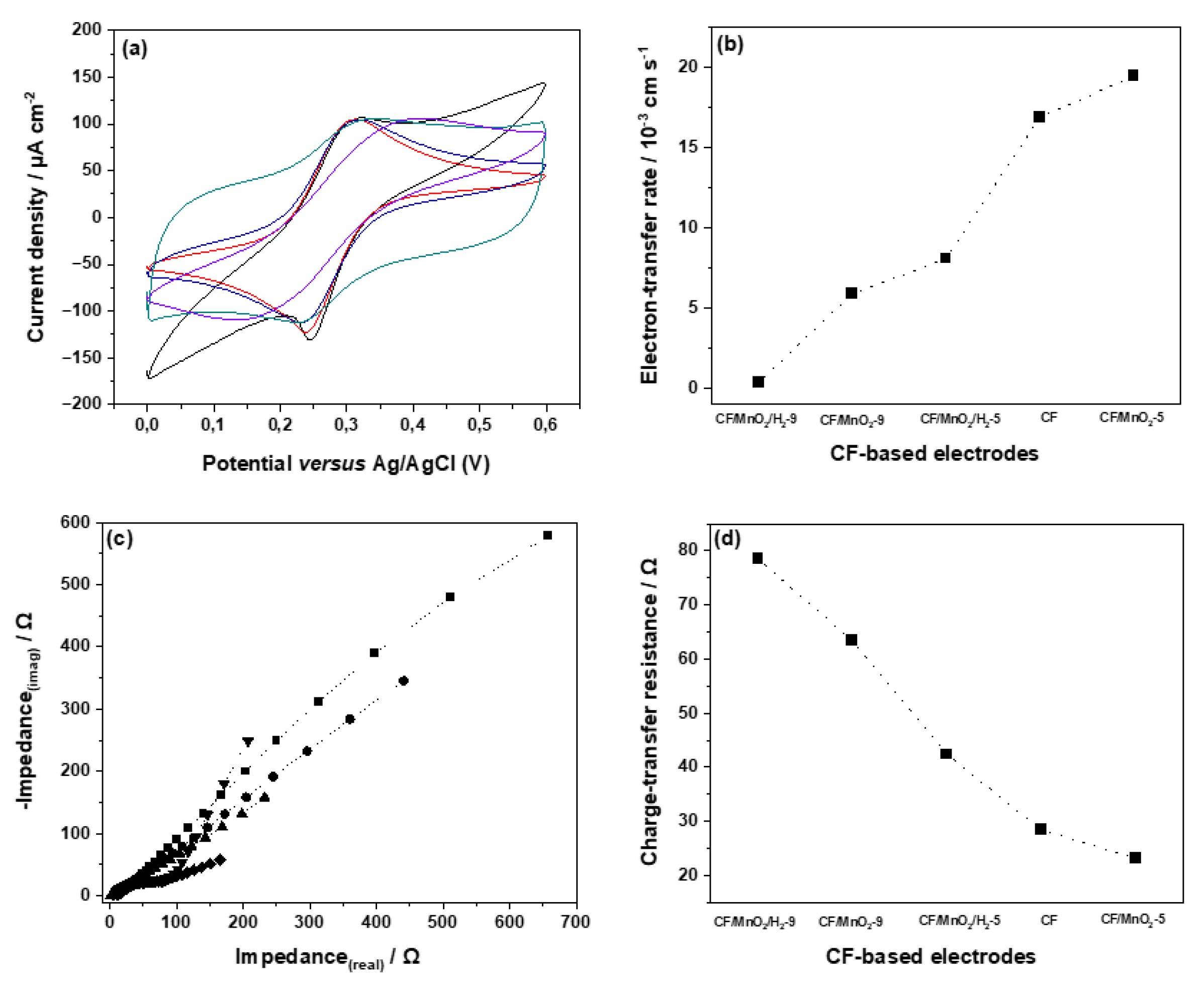

3.4. Electrochemical Response of CF-Electrodes Towards [Fe(CN)6]3-/4-

The electrochemical responses of bare CF and modified CF-based electrodes towards ferrocyanide/ferricyanide [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- standard redox system were studied by means of cyclic voltammetry method in aqueous KCl solution (1.0 mol∙L

-1). The results obtained for all studied electrodes are presented in

Table 9. Representative CVs are illustrated in

Figure 22a. In CV-curves depicted in

Figure 22a, the redox system [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- exhibits a pair of reversible redox peaks on CF-based electrodes. The oxidation-reduction peak current ratio is equal to unity and independent of applied scan rate, indicating that there are no parallel chemical reactions coupled to the electrochemical process. Similarly, the oxidative and reductive peak currents are constant for numerous cycles, indicating that there are no chemical reactions coupled to the electron transfer process and confirming that the redox system is stable in time frame of the experiment and that the charge-transfer process occurring on CF-based electrodes is quite reversible. The half-wave potential estimated for [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- redox system on CF-based electrodes appears to be similar within experimental error (E

1/2≈0,275 V

vs. Ag/AgCl), something that is quite expectable for reversible redox systems. Furthermore, the anodic and cathodic peak currents were found to vary linearly with the square root of scan rate in the investigated range of 0,02-0,10 V·s

-1, demonstrating that the studied redox system [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- is diffusion controlled on CF-based electrodes. From the extracted electrochemical parameters presented in

Table 9 it can be clearly seen that the anodic and cathodic peak potential separation (ΔE

p) estimated for [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- on bare CF and CF-based electrodes lies in the range from 0.068 to 0.236 V (at the scan rate of 0.02 V·s

-1) demonstrating differences between charge-transfer kinetics of [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- on various CF-based composite films studied. Namely, the large peak separation of

MnO2/CF #2 electrode (ΔE

p=0.086 V) indicates poorer electron-transfer kinetics of [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- on this particular electrode compared to other electrodes studied. The electron-transfer kinetics of

MnO2/CF #2 becomes even worse after the H

2-treatment. Thus, on

MnO2/CF/H2 #2 electrode fairly great value of peak potential separation has been estimated (ΔE

p=0.236 V). The smallest peak potential separation has been obtained for

MnO2/CF #1 electrode (ΔE

p=0.068V), which is slightly smaller compared to that of bare

CF electrode (ΔE

p=0.070V), and tends to increase after H

2-treatment. Consequently, on

MnO2/CF/H2 #1 slightly greater peak potential separation value has been obtained (ΔE

p=0.081 V) compared to untreated

MnO2/CF #1 electrode. Consequently, the heterogeneous electron transfer rate constants (

ks) determined for [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- on bare

CF and CF-based electrodes by means of electrochemical absolute rate relation tends to increase with the following order:

MnO2/CF/H2 #2 <

MnO2/CF #2 <

MnO2/CF/H2 #1 <

CF <

MnO2/CF #1 (

Figure 22b). The EIS measurements were carried out on CF-based electrodes in presence of [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- redox system for the estimation of charge-transfer resistance (

Rct) (

Figure 22c). This parameter provides an estimation of the barrier to overall heterogeneous electron-transfer occurring at the electrode-electrolyte interface. The estimated

Rct values are included in

Table 9 along with the other electrochemical parameters of [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- on various CF-based electrodes. The

Rct values obtained on various CF-based electrodes are presented graphically in

Figure 22d. It is quite interesting that the charge-transfer resistance estimated by means of EIS tends to decrease with the order:

MnO2/CF/H2 #2 <

MnO2/CF #2 <

MnO2/CF/H2 #1 <

CF <

MnO2/CF #1 (similarly to

ks parameter), indicating that a diminishing of barrier of redox process with the simultaneous enhancement of electron-transfer kinetics takes place. For the estimation of lower limit of detection and sensitivity of CF and CF-based electrodes towards [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- the variation of oxidation peak current with the concentration of redox system in concentration range of 7.0×10

-5-1.0×10

-3 mol∙L

-1 was examined. The electrochemical response of CF and CF-based electrodes towards [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- plotted as oxidation peak current density

versus concentration of electroactive compound appears to be linear in investigated concentration range. From the standard deviation of electrochemical response and the slope of linear oxidation current-concentration plots, the lower limit of detections of bare CF and CF-based electrodes towards [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- were estimated and are included in

Table 9. The results exhibit that the electrochemical quality of CF-based electrodes can be considered quite good.