Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Building Information Modelling (BIM)

| ▪ Country | BIM Adoption | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ▪ UK | 70% | 2019 | [33,35,45] |

| ▪ Brazil | 72% | 2015 | [46,47] |

| ▪ Germany | 71% | 2015 | [23,45,48] |

| ▪ France | 70% | 2015 | [23,47] |

| ▪ Canada | 70% | 2016 | [33,35,45] |

| ▪ New Zealand | 80% | 2019 | [49,50] |

| ▪ Australia | 80% | 2019 | [44,49,51] |

| ▪ China | 82% | 2016 | [35,52] |

| ▪ Denmark | 80% | 2016 | [33,45,48] |

3. Methodology

| ▪ | Architects | Engineers | Land Surveyors | Quantity Surveyors | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ▪ No. | 24 | 78 | 24 | 17 | 143 |

| ▪ %age | 16.8 | 54.5 | 16.8 | 11.9 | 100 |

4. Results

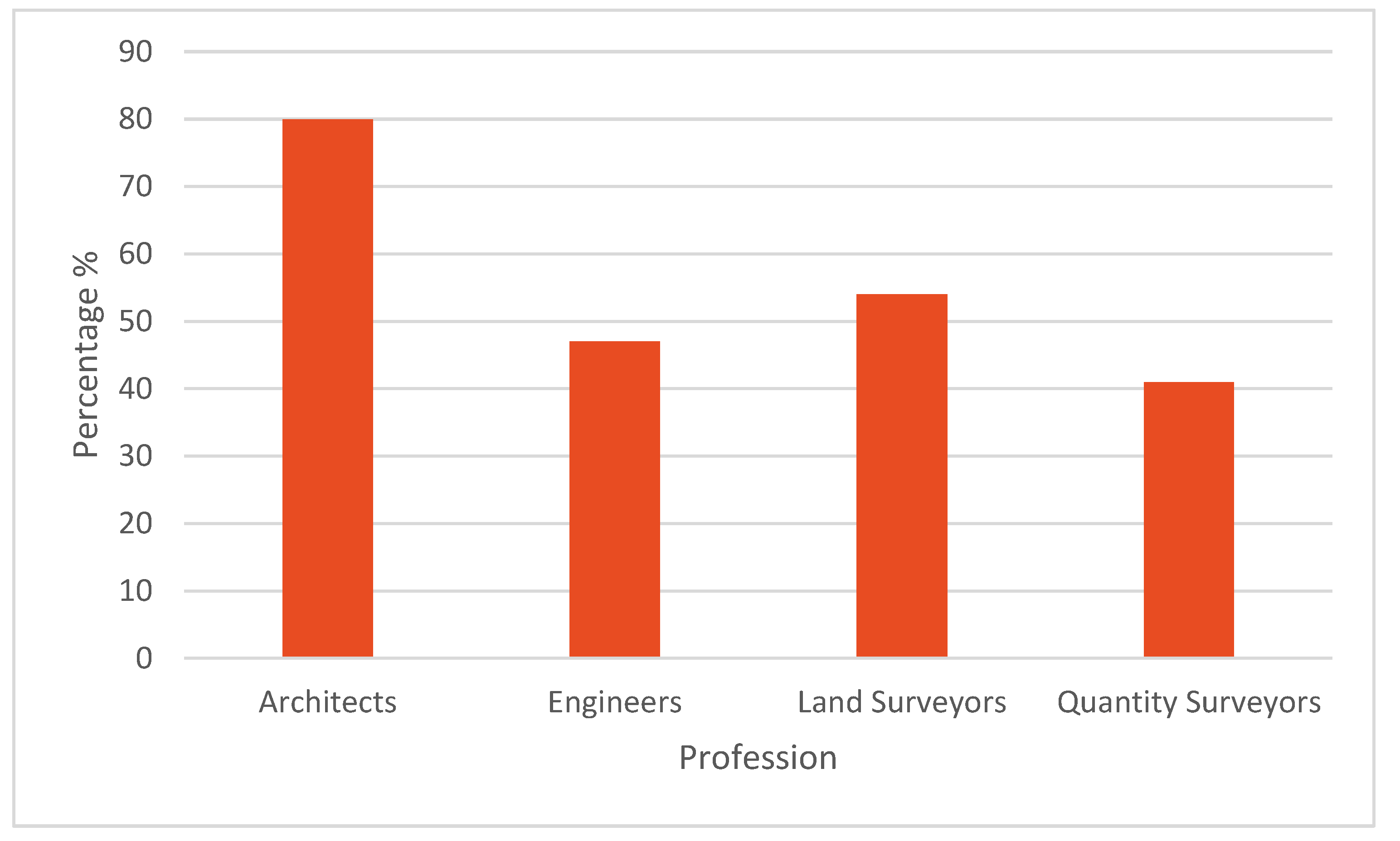

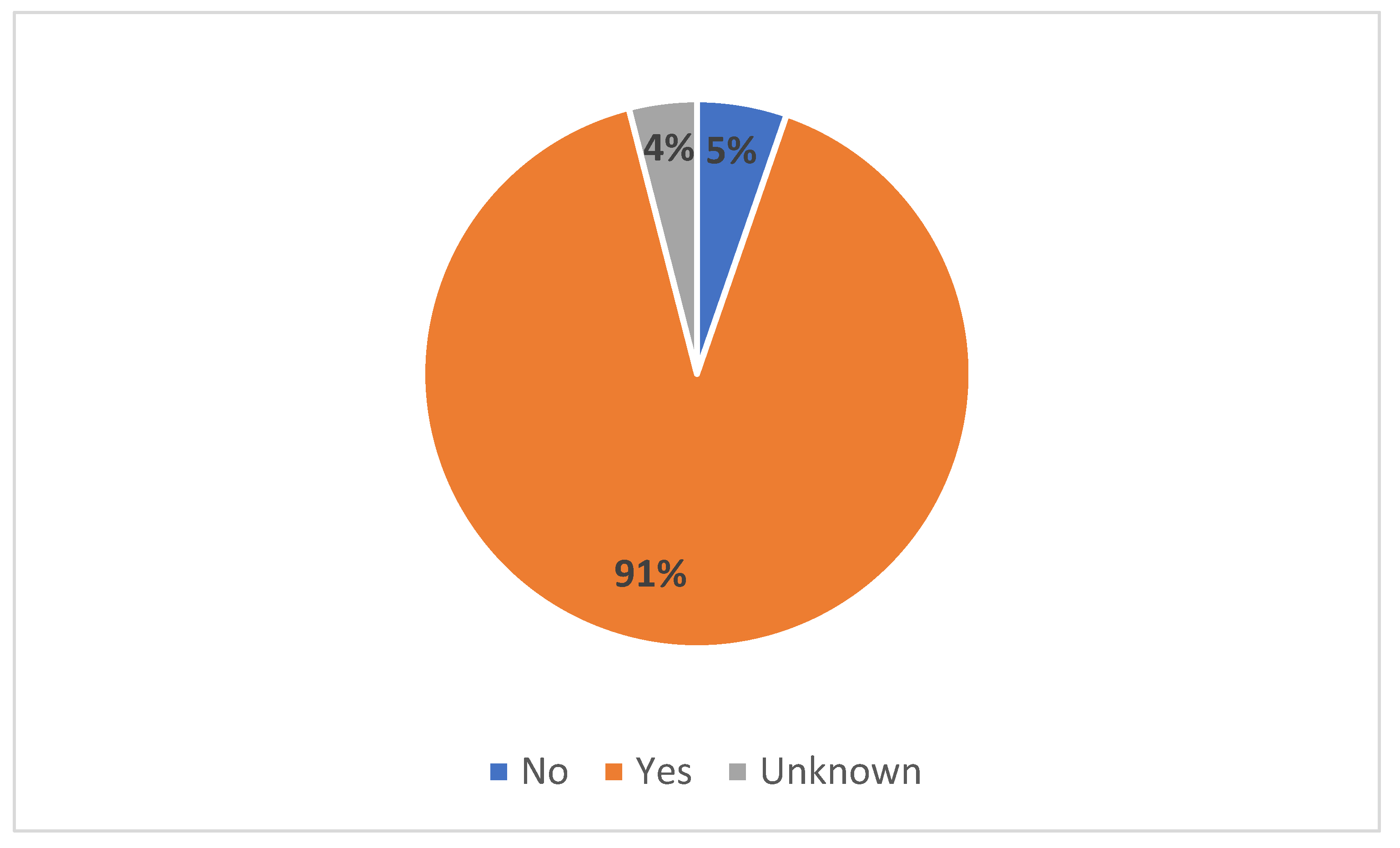

4.1. Awareness of BIM

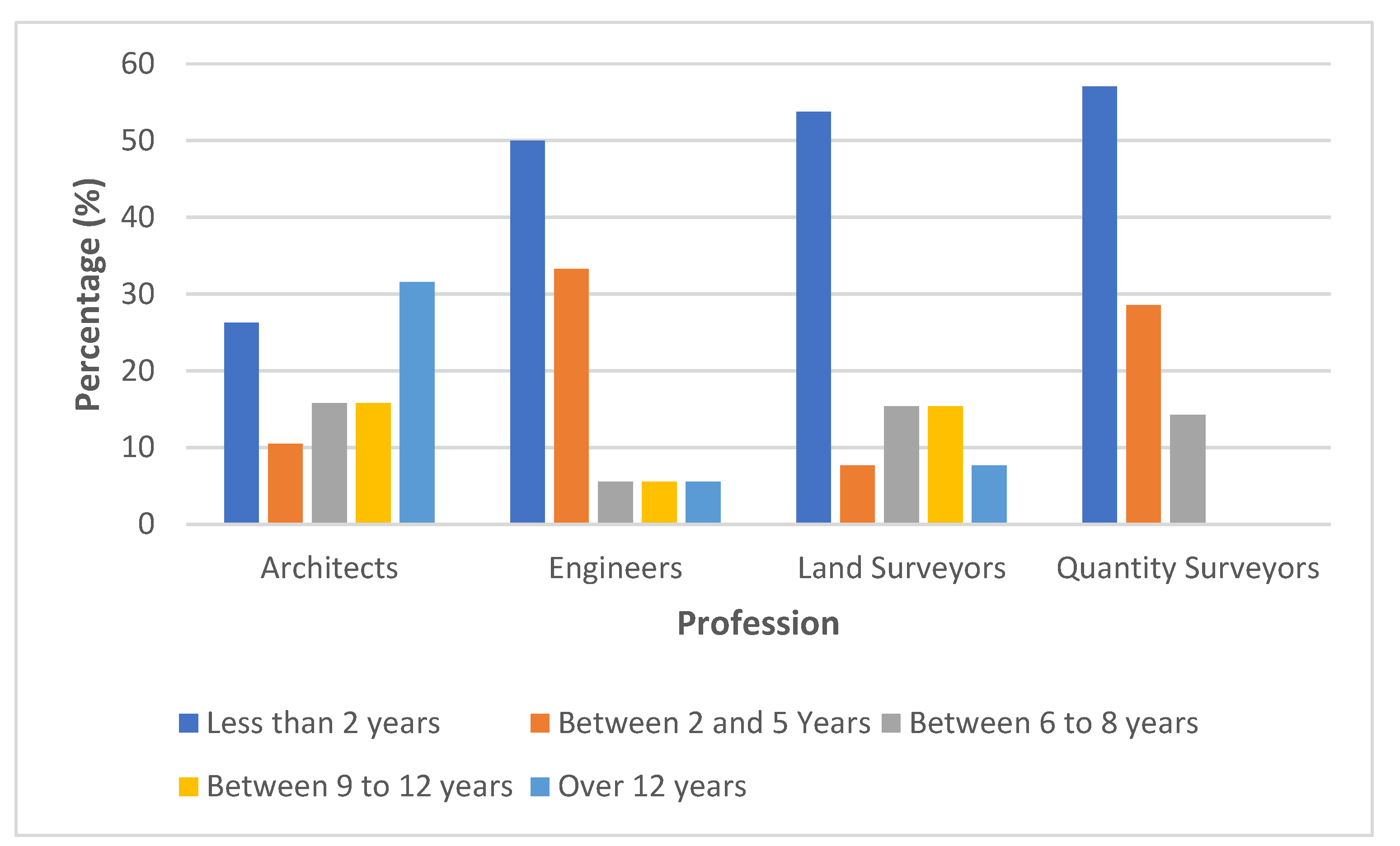

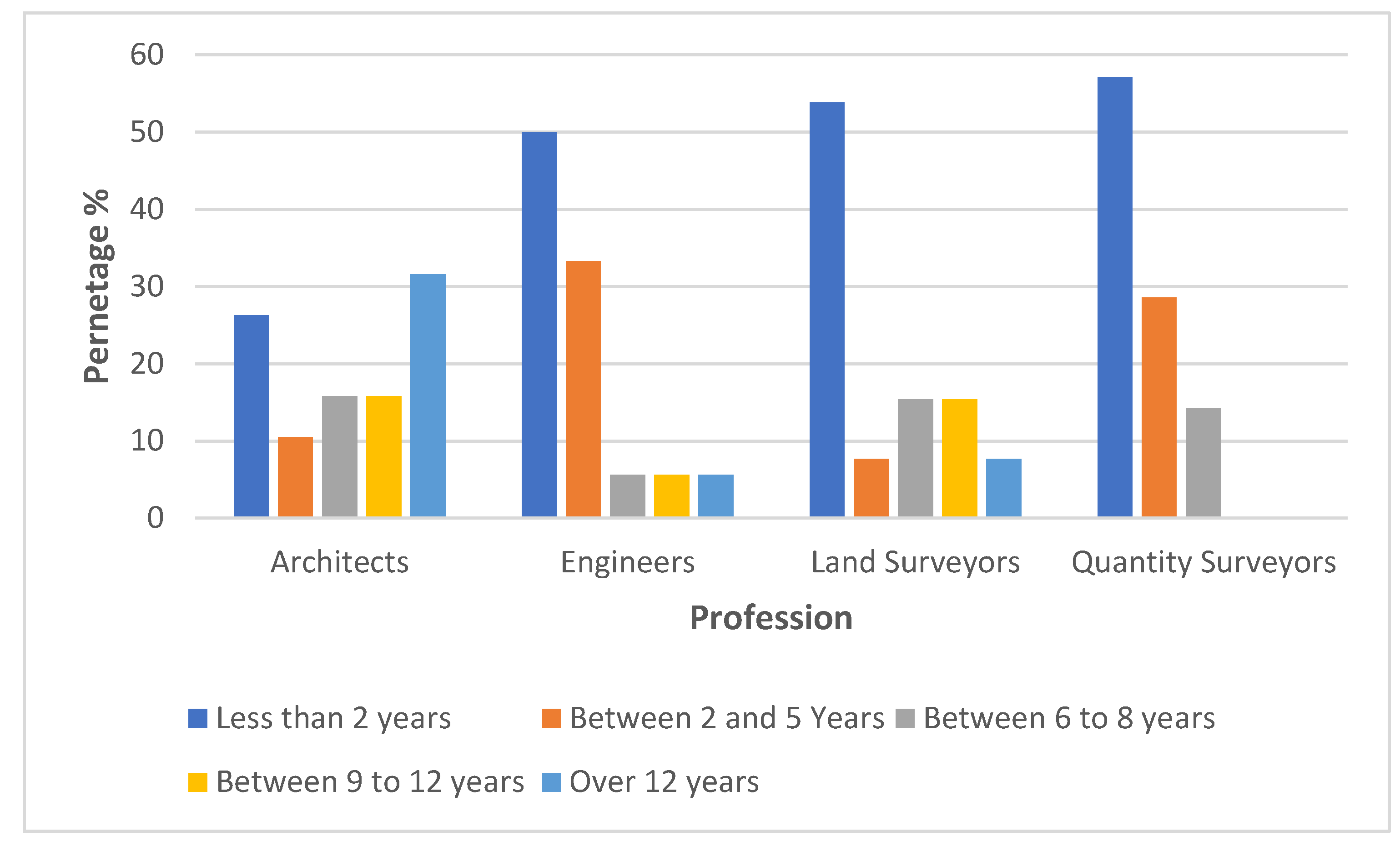

4.3. Years of Use of BIM

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Less than 2 years | 34 | 23.8 | 45.3 | 45.3 |

| Between 2 and 5 years | 17 | 11.9 | 22.7 | 68.0 | |

| Between 6 and 8 years | 8 | 5.6 | 10.7 | 78.7 | |

| Between 9 and 12 years | 7 | 4.9 | 9.3 | 88.0 | |

| Over 12 years | 9 | 6.3 | 12.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 75 | 52.4 | 100.0 | ||

| Missing | 68 | 47.6 | |||

| Total | 143 | 100.0 | |||

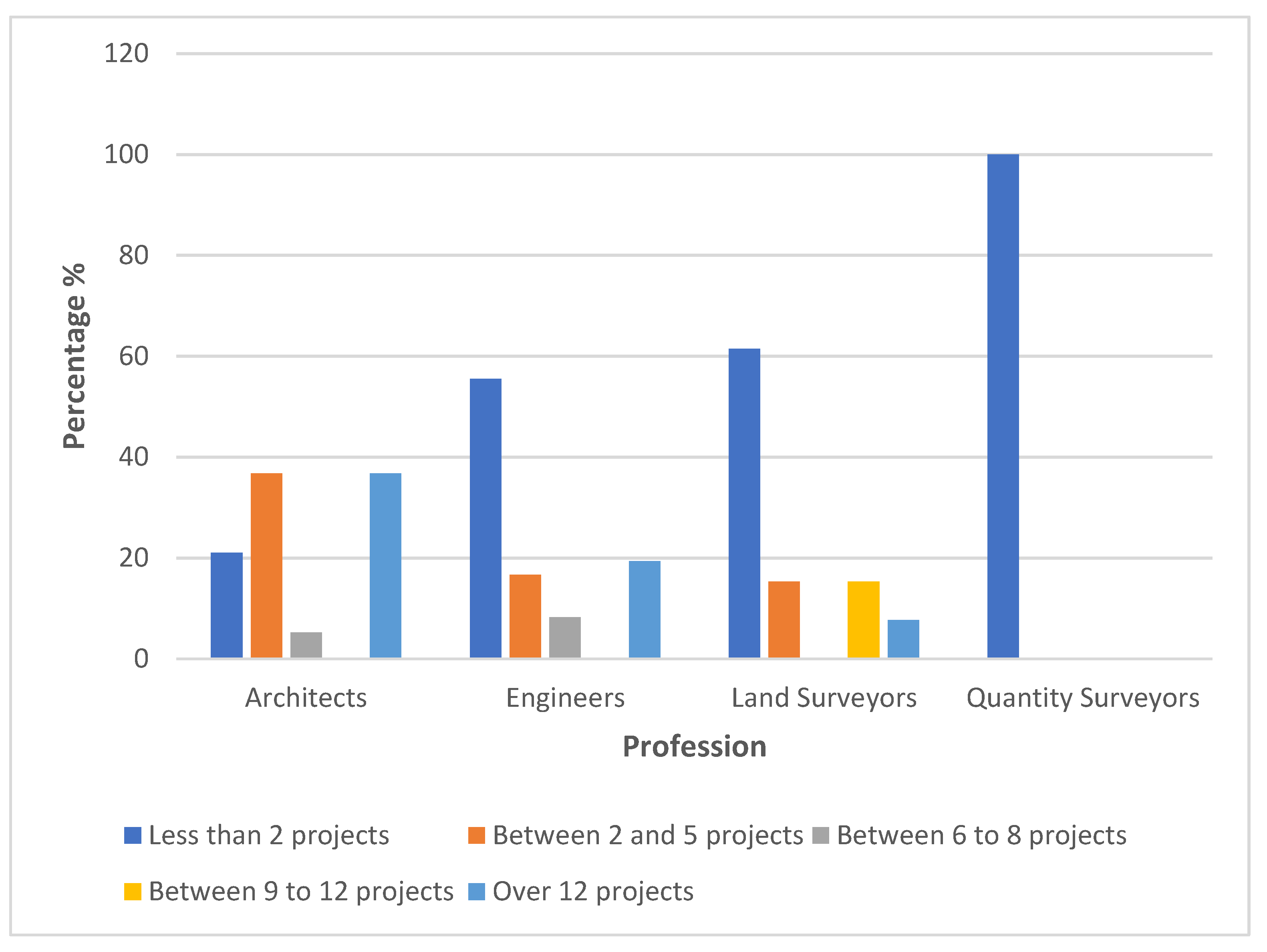

4.3. Number of Projects Done Using BIM

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Less than 2 projects | 39 | 27.3 | 52.0 | 52.0 |

| Between 2 and 5 projects | 15 | 10.5 | 20.0 | 72.0 | |

| Between 6 and 8 projects | 4 | 2.8 | 5.3 | 77.3 | |

| Between 9 and 12 projects | 2 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 80.0 | |

| Over 12 projects | 15 | 10.5 | 20.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 75 | 52.4 | 100.0 | ||

| Missing | 68 | 47.6 | |||

| Total | 143 | 100.0 | |||

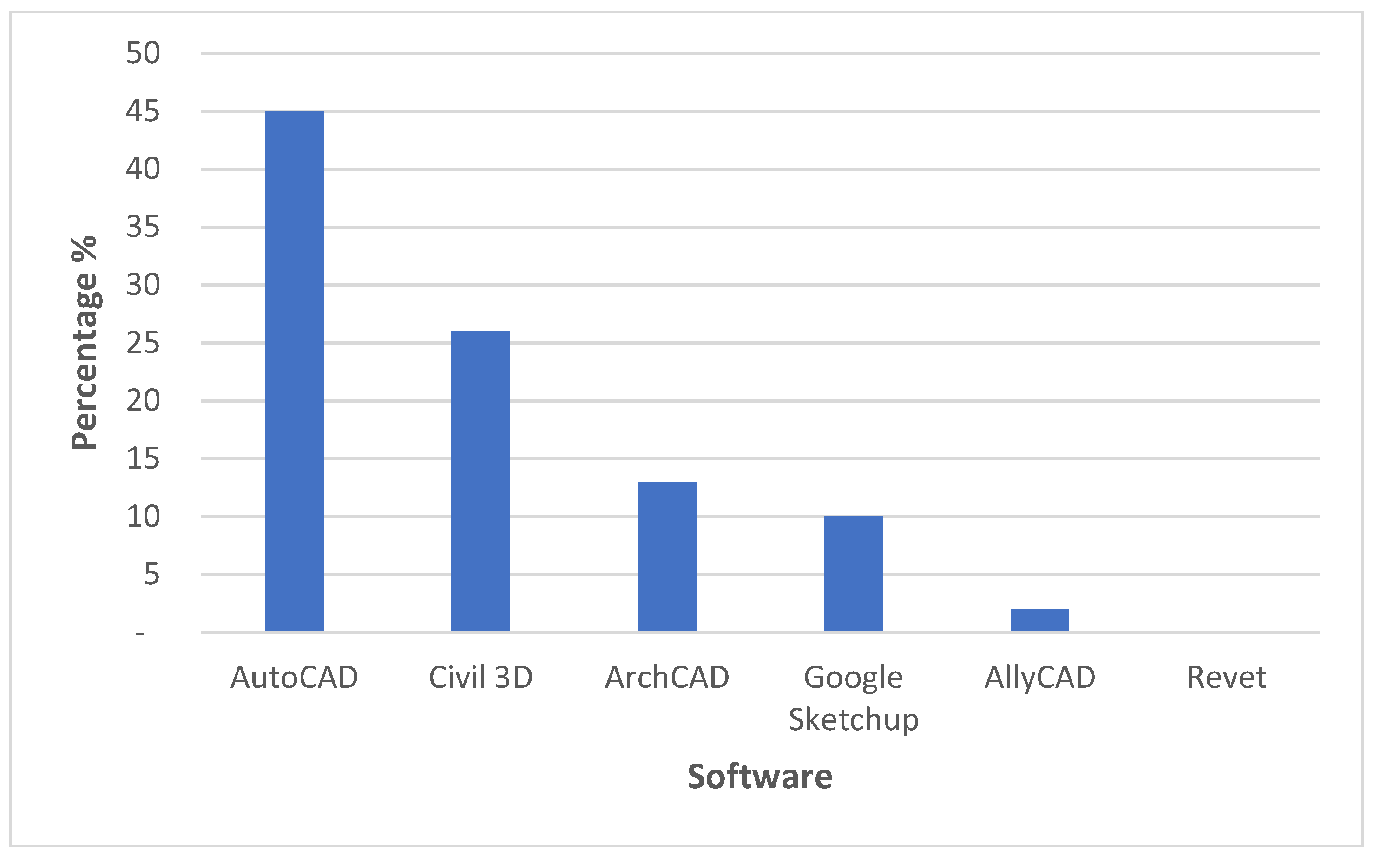

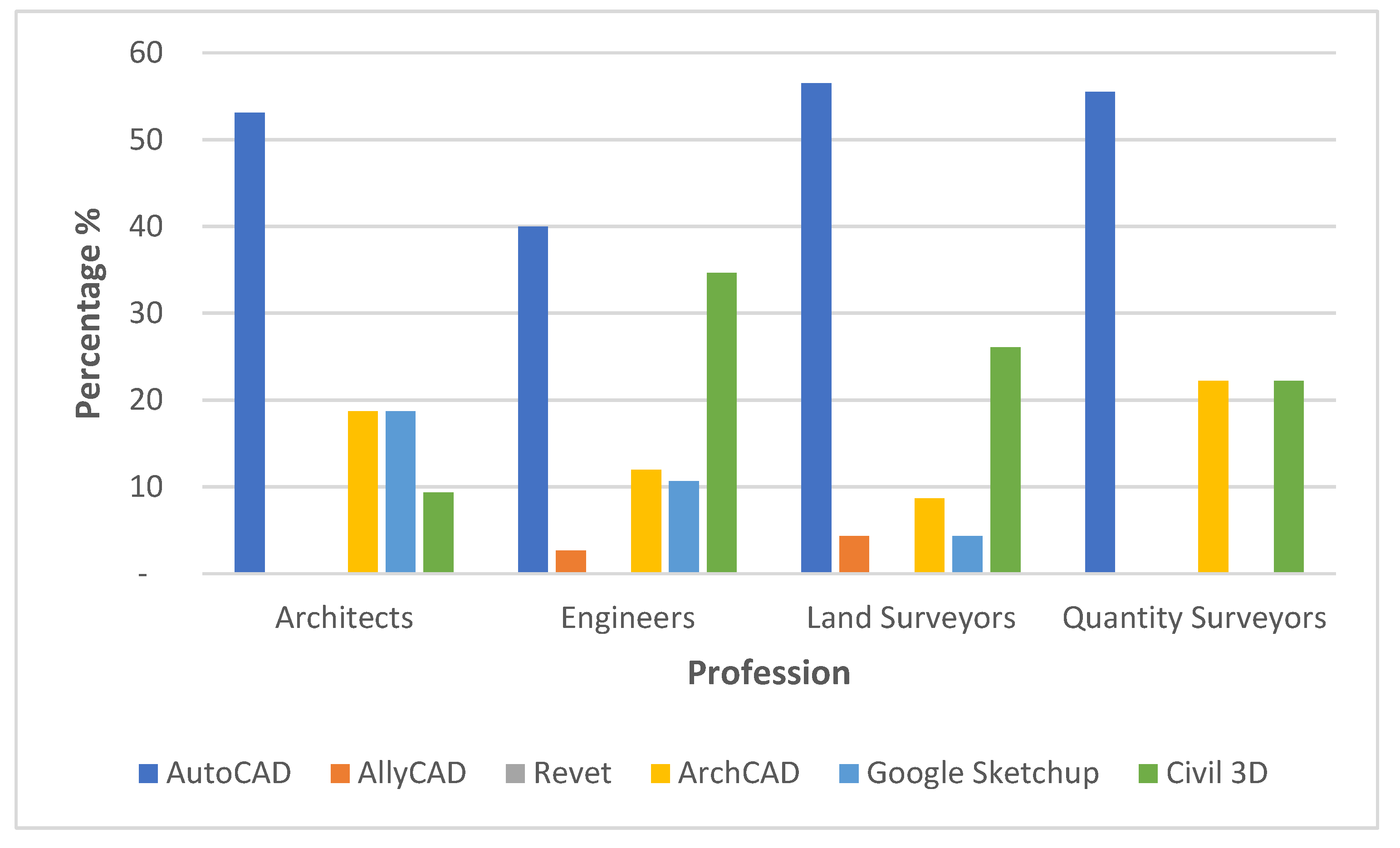

4.3. Software used for BIM

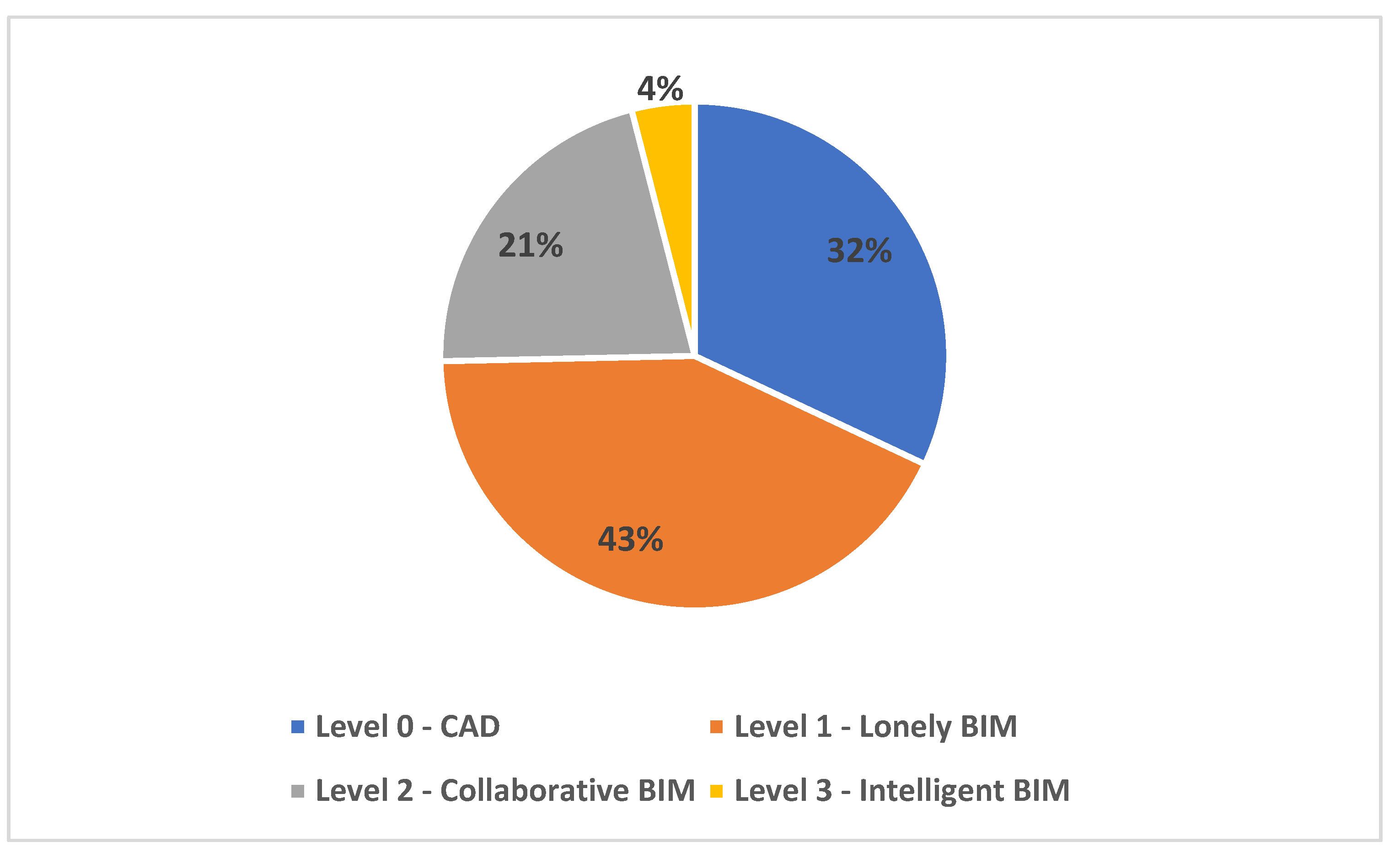

4.3. Level of Use of BIM

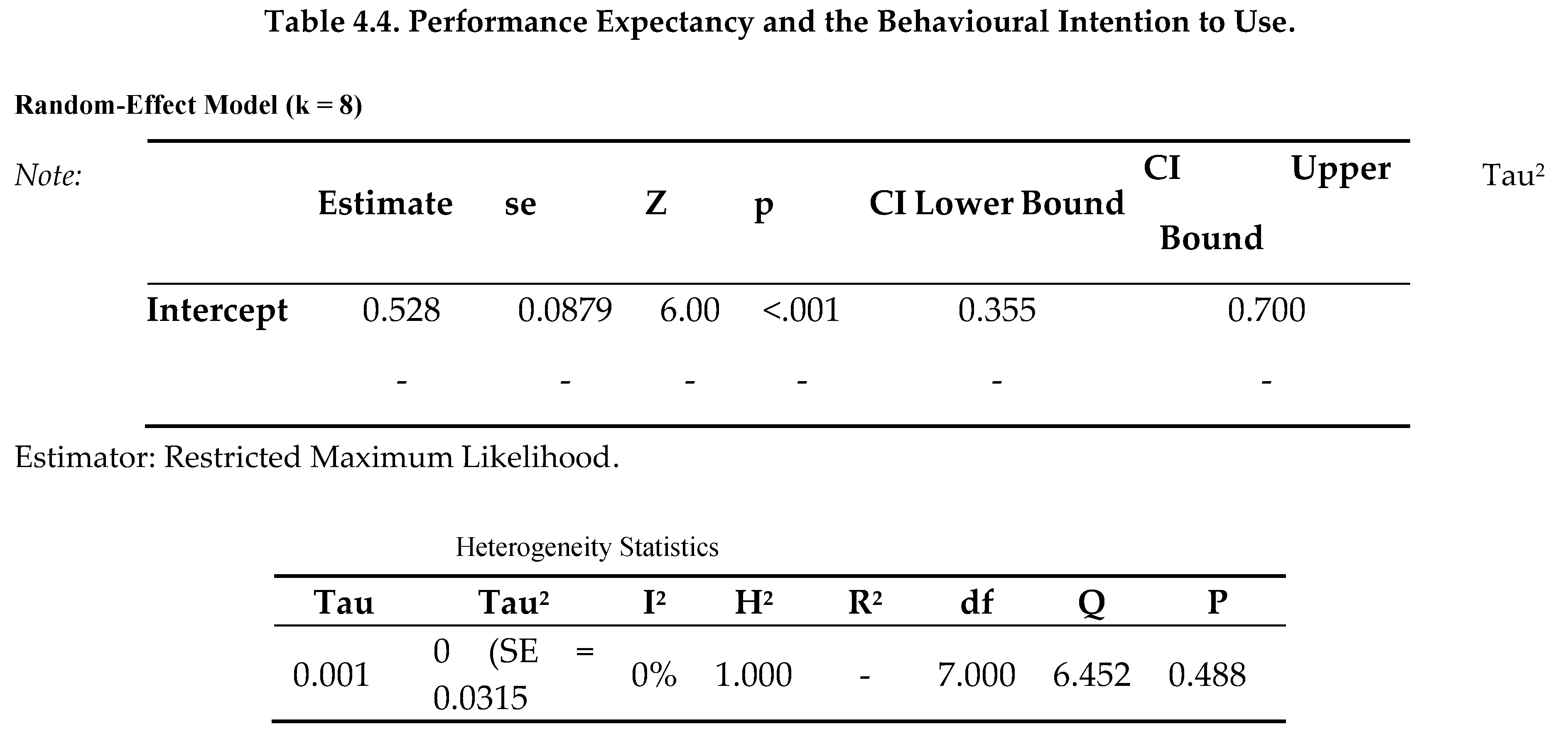

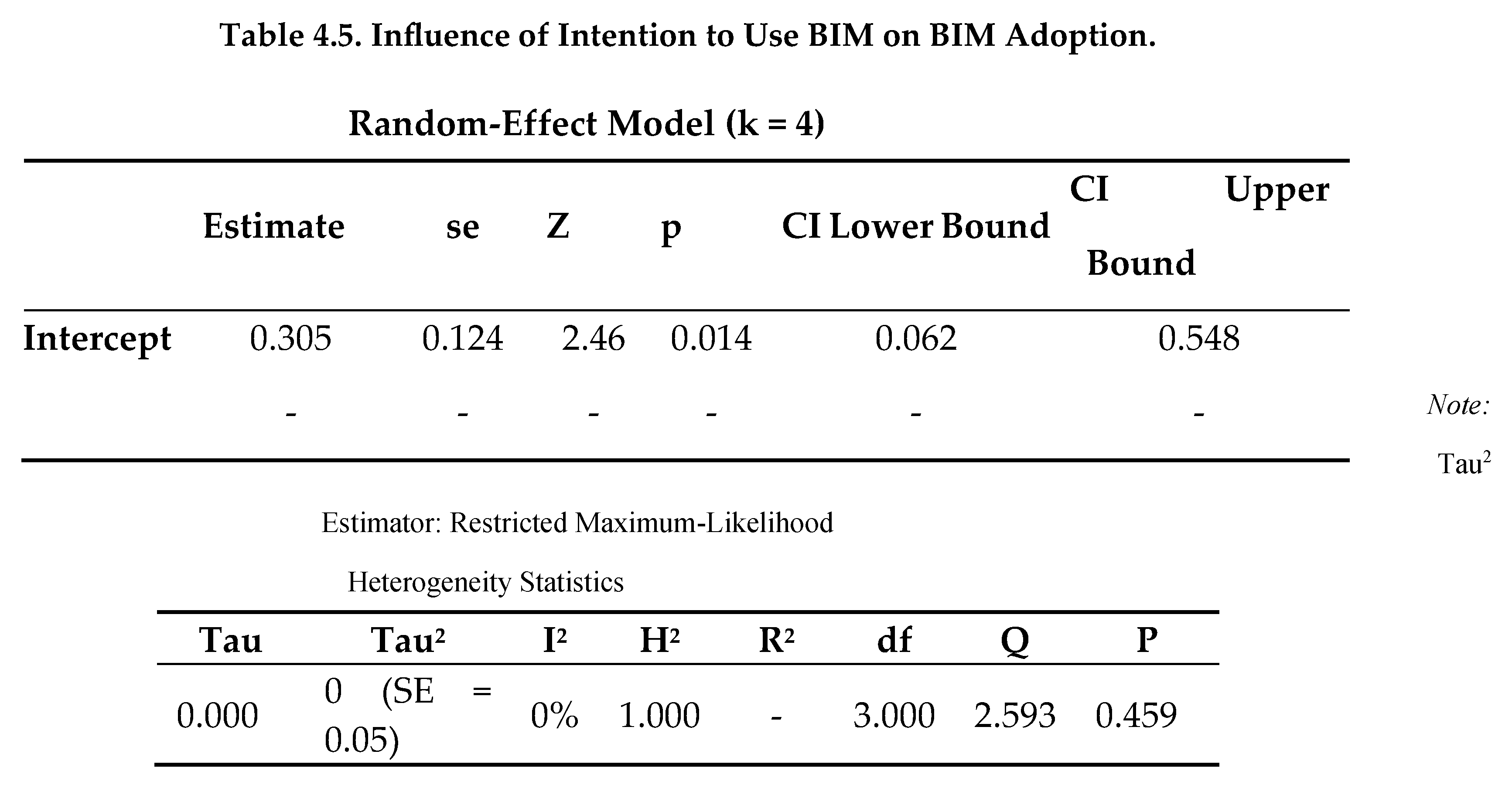

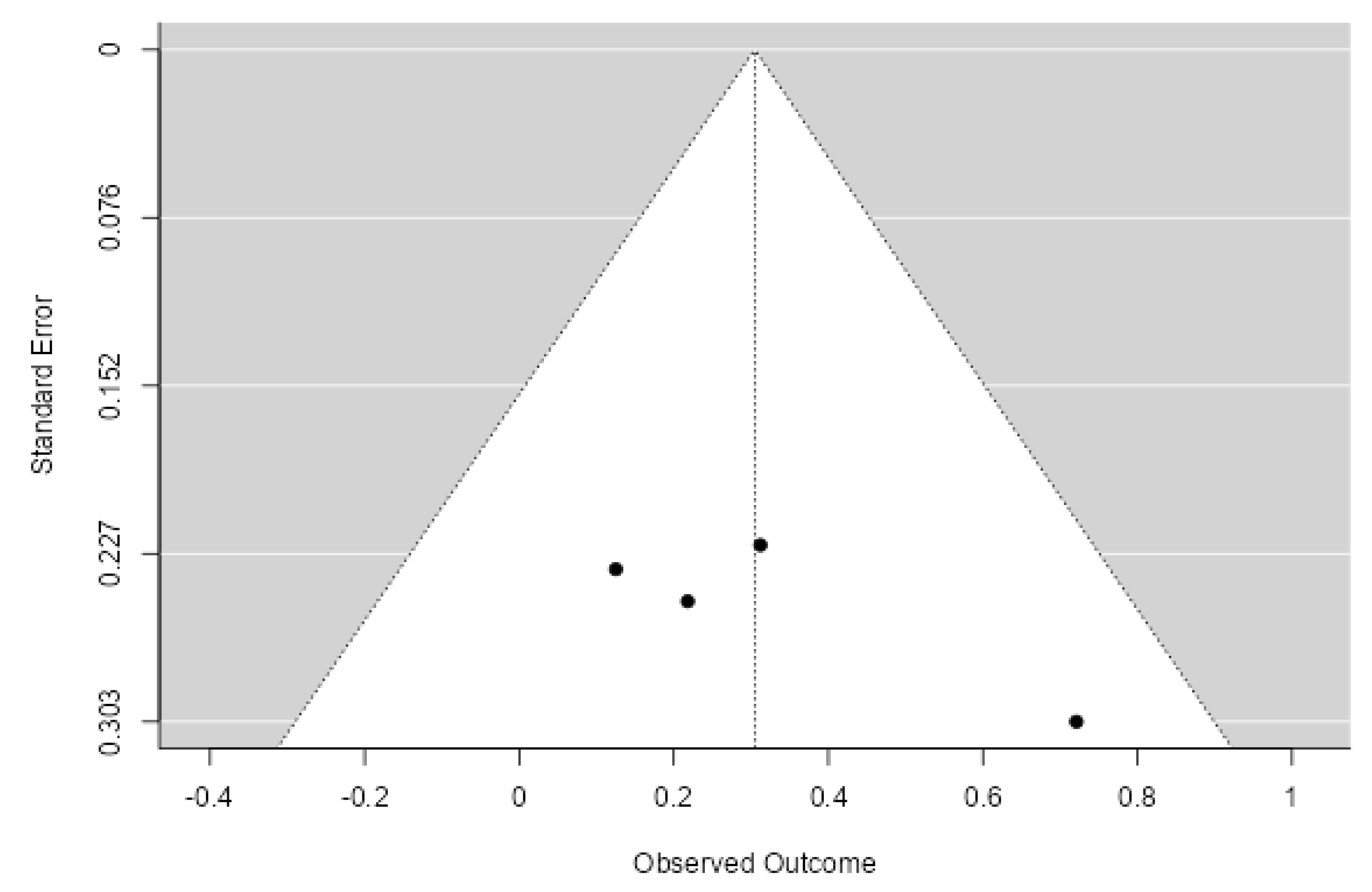

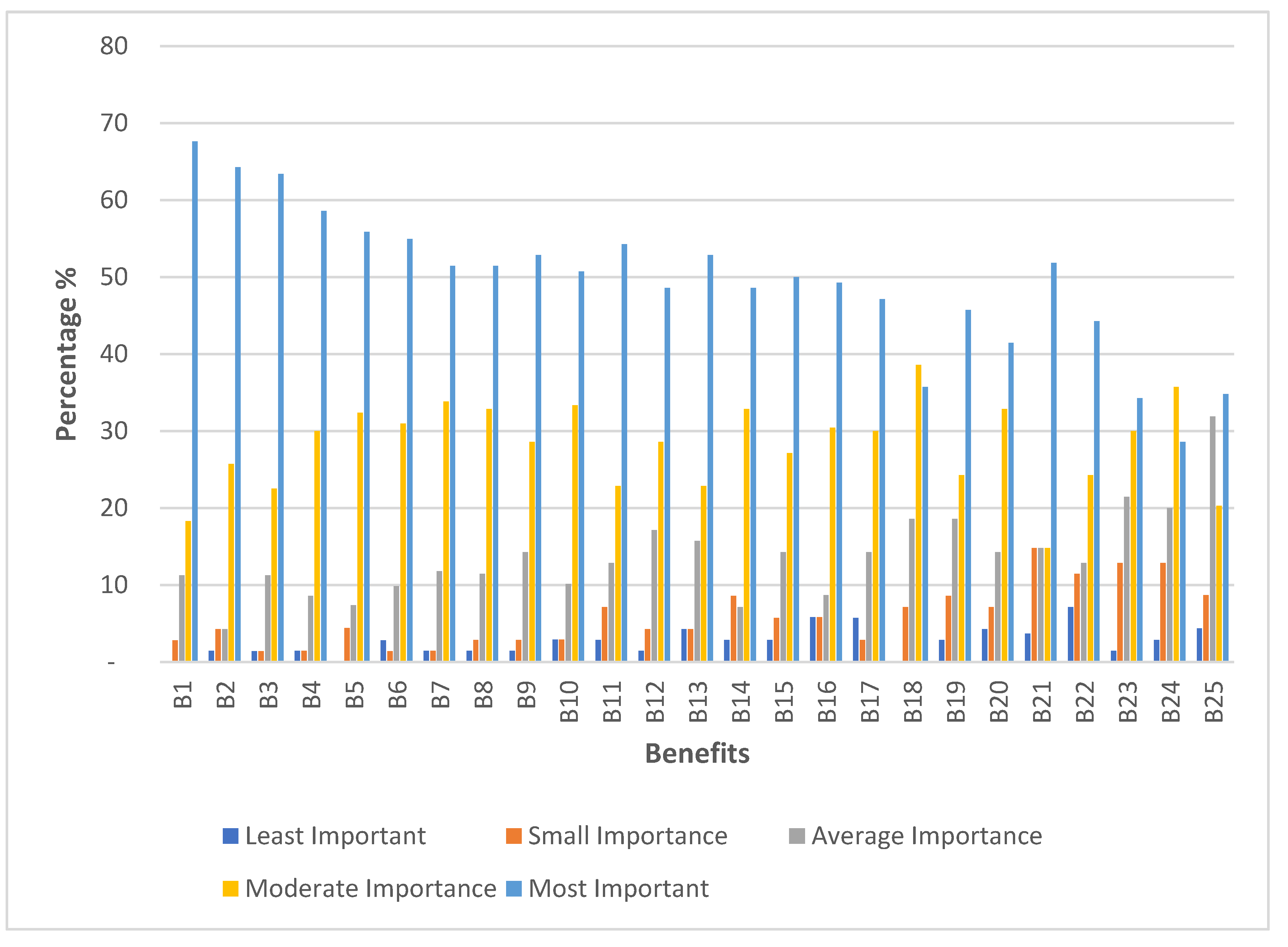

4.3. A Meta-analysis of BIM Benefits

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total | RII | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | Enhanced design analysis and efficiency due to produced element details | 0 | 2 | 8 | 13 | 48 | 71 | 0.9 | 1 |

| B2 | Generation of accurate and consistent 3D drawings at any stage | 1 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 45 | 70 | 0.89 | 2 |

| B3 | Enhance collaboration between project parties | 1 | 1 | 8 | 16 | 45 | 71 | 0.89 | 3 |

| B4 | Earlier and more accurate design visualisation | 1 | 1 | 6 | 21 | 41 | 70 | 0.89 | 4 |

| B5 | Improved design quality | 0 | 3 | 5 | 22 | 38 | 68 | 0.88 | 5 |

| B6 | Enhance communication between project parties | 2 | 1 | 7 | 22 | 39 | 71 | 0.87 | 6 |

| B7 | Reduced redesign challenges during project implementation | 1 | 1 | 8 | 23 | 35 | 68 | 0.86 | 7 |

| B8 | Potentially improved maintenance of the infrastructure due to the as-built model | 1 | 2 | 8 | 23 | 36 | 70 | 0.86 | 8 |

| B9 | Improved communication among various divisions of the same company | 1 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 37 | 70 | 0.86 | 9 |

| B10 | Greater productivity due to easy retrieval of information. | 2 | 2 | 7 | 23 | 35 | 69 | 0.85 | 10 |

| B11 | Enhanced work coordination with subcontractors/supply chain | 2 | 5 | 9 | 16 | 38 | 70 | 0.84 | 11 |

| B12 | Improved coordination in the construction phase | 1 | 3 | 12 | 20 | 34 | 70 | 0.84 | 11 |

| B13 | Reduce reworking during construction | 3 | 3 | 11 | 16 | 37 | 70 | 0.83 | 13 |

| B14 | Improved management of projects schedule milestones | 2 | 6 | 5 | 23 | 34 | 70 | 0.83 | 13 |

| B15 | Potentially improved whole life asset management | 2 | 4 | 10 | 19 | 35 | 70 | 0.83 | 13 |

| B16 | Improved maintenance due to level of details produced | 4 | 4 | 6 | 21 | 34 | 69 | 0.82 | 16 |

| B17 | Efficiencies from reuse of data or details (enter once, use many times) | 4 | 2 | 10 | 21 | 33 | 70 | 0.82 | 17 |

| B18 | Improved site analysis | 0 | 5 | 13 | 27 | 25 | 70 | 0.81 | 18 |

| B19 | Greater predictability of project time and cost | 2 | 6 | 13 | 17 | 32 | 70 | 0.8 | 19 |

| B20 | Improved conflict detection | 3 | 5 | 10 | 23 | 29 | 70 | 0.8 | 20 |

| B21 | Improve project information management | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 14 | 27 | 0.79 | 21 |

| B22 | Fewer change/variation orders at the construction stage | 5 | 8 | 9 | 17 | 31 | 70 | 0.77 | 22 |

| B23 | Improved human resources management | 1 | 9 | 15 | 21 | 24 | 70 | 0.77 | 23 |

| B24 | Enhanced management of security and safety information | 2 | 9 | 14 | 25 | 20 | 70 | 0.75 | 24 |

| B25 | Allowing accurate site logistics | 3 | 6 | 22 | 14 | 24 | 69 | 0.74 | 25 |

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arellano, K.; Andrade, A.; Castillo, T.; Herrera, R. F. Assessment of BIM use in the early stages of implementation. Rev. Ing. Constr. 2021, 36(no. 3), 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, A. B.; Chan, D. W. M. A scientometric review and metasynthesis of building information modelling (BIM) research in Africa. Buildings 2019, 9(no. 4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank, A Narrow Path to Prosperity. 2023. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099121123151012043/p17753704298250df0b05d02489cfd76b51.

- Government of Malawi, “Malawi 2063,” Malawi ’s Vision. In An inclusively wealthy self-reliant nation; 2020; pp. 1–92.

- Kulemeka, P. J.; Kululanga, G.; Morton, D. Critical Factors Inhibiting Performance of Small- and Medium-Scale Contractors in Sub-Saharan Region: A Case for Malawi. J. Constr. Eng. 2015, 2015, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmadi, S. Enhancing Road Infrastructure Financing in Malawi: A Comprehensive Analysis & Recommendations. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2023, 5(no. 5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, V.; Shkaratan, M. Malawi’s Infrastructure A Continental Perspective. 2011. Available online: http://econ.worldbank.org.

- Sukasuka, G. N.; Manase, D. Best Practice Guide to Procurement Challenges of Public-Private Partnerships in Infrastrcture Development in Malawi. J. Constr. Proj. Manag. Innov. 2016, 6, 1503–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Malawi. “Public-Private-Partnership-ACT-2022,” no. 23. 2022. Available online: https://api.pppc.mw/storage/547/Public-Private-Partnership-ACT-2022-and-Policy(2)-(003)-editing-(005).pdf.

- Adetoro, P.; Kululanga, G.; Mkandawire, T.; Malik, A. A Critical Analysis of Factors Influencing BIM Implementation for Public Projects in Developing Countries: A Case Study of Malawi. Buildings 2025, 15(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilipunde, R. L. Contraints and Challenges Faced by Small, Medium and Micro Enterprise Contractors in Malawi; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Emuze, F.; Kadangwe, S. Diagnostic view of road projects in Malawi. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2014, 167(no. 1), 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, R.; Kalina, M.; Kafodya, I.; Tilley, E. A sustainable alternative to traditional building materials: assessing stabilised soil blocks for performance and cost in Malawi. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2023, 16(no. 1), 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafodya, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Basuroy, D.; Marangu, J. M.; Kululanga, G.; Maddalena, R.; Novelli, V. I. Mechanical Performance and Physico-Chemical Properties of Limestone Calcined Clay Cement (LC3) in Malawi. Buildings 2023, 13(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Afari, M. F.; Li, H.; Pärn, E. A.; Edwards, D. J. Critical success factors for implementing building information modelling (BIM): A longitudinal review. Autom. Constr. 2018, 91, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryde, D.; Broquetas, M.; Volm, J. M. The project benefits of building information modelling (BIM). Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31(no. 7), 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, E.; Kim, M. BIM awareness and acceptance by architecture students in Asia. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2016, 15(no. 3), 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheisari, M.; Irizarry, J. Investigating human and technological requirements for successful implementation of a BIM-based mobile augmented reality environment in facility management practices. Facilities 2016, 34(no. 1–2), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mora, V.; Navarro, I. J.; Yepes, V. Integration of the structural project into the BIM paradigm: A literature review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 53, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndwandwe, M.; Kuotcha, W.; Mkandawire, T. Organizational Readiness for Building Information Modeling Implementation in Malawi: Awareness and Competence. Buildings 2024, 14(no. 8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndwandwe, M.; Kuotcha, W.; Mkandawire, T. Building information modeling: implementation challenges in the Malawian construction industry. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagunda, G.; Kuotcha, W.; Kafodya, I. Factors influencing Building Information (BIM) implementation in developing countries. Build. Smart, Resilient Sustain. Infrastruct. Dev. Ctries. 2023, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Lee, G. The Status of BIM Adoption on Six Continents. Int. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2015, 9(no. 5), 512–516. Available online: www.sciencedirect.com.

- Borkowski, A. S. Evolution of BIM: Epistemology, Genesis and Division into Periods. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2023, 28, 646–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, R.; Paavola, S. Beyond the BIM utopia: Approaches to the development and implementation of building information modeling. Autom. Constr. 2014, 43, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succar, B. Building information modelling framework: A research and delivery foundation for industry stakeholders. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18(no. 3), 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government, “Government Construction Strategy,” Construction, no. May, p. 43, 2011, [Online]. Available online: www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

- Succar, B. Building information modelling framework: A research and delivery foundation for industry stakeholders. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18(no. 3), 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilov, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Shilova, L. To the question of the building information modeling technologies transition to a new development level. E3S Web of Conferences 2021, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsloo, D.; Bekker, M. C. BIM adoption & implementation trends in the South African AEC industry. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 256, 1921–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, A.; Jalaei, F.; Khanzadi, M.; Banihashemi, S. BIM-integrated TOPSIS-Fuzzy framework to optimize selection of sustainable building components. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 22(no. 7), 1240–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, K.; Tam, V. W. Y.; Di Gregorio, L. T.; Evangelista, A. C. J.; Hammad, A. W. A.; Haddad, A. Integrating parametric analysis with building information modeling to improve energy performance of construction projects. Energies 2019, 12(no. 8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safour, R.; Ahmed, S.; Zaarour, B. BIM Adoption around the World. Int. J. BIM Eng. Sci. 2021, 4(no. 2), 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, A. N.; Samad, S. A.; Nawi, M. N. M.; Haron, N. A. Existing practices of building information modeling (BIM) implementation in the public sector. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 5(no. 4), 166–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud, E. Al. Comparing BIM Adoption Around the World, Syria’s Current Status and Future. International Journal of BIM and Engineering Science 2021, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A. K. D.; Wong, F. K. W.; Nadeem, A. Attributes of building information modelling implementations in various countries. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2010, 6, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Liao and E. A. L. Teo. Critical Success Factors for enhancing the Building Information Modelling implementation in building projects in Singapore. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2017, 23(no. 8), 1029–1044. [CrossRef]

- S. Kubba, Green Building Design and Construction. Hayton Joe, 2017.

- Fürstenberg, D.; Lædre, O. Application of BIM design manuals: A case study. 27th Annu. Conf. Int. Gr. Lean Constr. IGLC 2019, 145, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagesen, G.; Krogstie, J. Handbook on Business Process Management 1. Handb. Bus. Process Manag. 1 2010, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haron, A.; Devi, P.; Hassim, S.; Alias, A. H.; Tahir, M. M.; Harun, A. N. Project management practice and its effects on project success in Malaysian construction industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 291(no. 1), 0–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H.; Kim, B. G. IFC extension for road structures and digital modeling. Procedia Eng. 2011, 14, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank, Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2020. 2020.

- The Queensland Government, “Building Information Modelling (BIM) for Transport and Main Roads Guideline,” no. May, pp. 1–21, 2024, [Online]. Available: file:///C:/Users/Deinsam/Downloads/BIM-Guideline.pdf.

- Ullah, K.; Lill, I.; Witt, E. An overview of BIM adoption in the construction industry: Benefits and barriers. In Emerald Reach Proceedings Series; Emerald Group Holdings Ltd., 2019; vol. 2, pp. 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Edirisinghe, R.; London, K. Comparative Analysis of International and National Level BIM Standardization Efforts and BIM adoption. Proc. 32nd CIB W78 Conf. 2015, 27th-29th Oct. 2015, Eindhoven, Netherlands, 2015; pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J. C. P.; Lu, Q. A review of the efforts and roles of the public sector for BIM adoption worldwide. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 20(October), 442–478.

- Walasek, D.; Barszcz, A. Analysis of the Adoption Rate of Building Information Modeling [BIM] and its Return on Investment [ROI]. in Procedia Engineering 2017, 172, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamma-adama, M.; Kouider, T. A Review on Building Information Modelling in Nigeria and Its Potentials. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2018, 12(no. 11), 1113–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Nassereddine, H.; Hatoum, M. B.; Hanna, A. S. Overview of the State-of-Practice of BIM in the AEC Industry in the United States. Proc. Int. Symp. Autom. Robot. Constr. 2022, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahankoob, A.; Abbasnejad, B.; Aranda-Mena, G. Building Information Modelling (BIM) Acceptance and Learning Experiences in Undergraduate Construction Education: A Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) Perspective—An Australian Case Study. Buildings 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, A. M.; Fischer, T. BIM adoption across the Chinese AEC industries: An extended BIM adoption model. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2019, 6(no. 2), 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutonyi, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Cloete, C. Adoption of Building Information Modelling in the construction industry in Kenya design quality is influenced by the number of. Acta Structilia 2018, 25(no. 2), 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Olorunfemi, E.; Oyewobi, L.; Olanrewaju, O.; Olorunfemi, R. “Competencies and the Penetration Status of Building Information Modelling Among Built Environment Professionals in Nigeria,” 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352787164.

- Balah, M.; Akut, L. Assessment of Building Information Modeling (BIM) Knowledge in the Nigerian Construction Industry. Int. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. IJCEE-IJENS 2015, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ashmori, Y. Y. , BIM benefits and its influence on the BIM implementation in Malaysia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2020, vol. 11(no. 4), 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. B. Saka, D. W. M. Chan, and F. M. F. Siu, “Adoption of Building Information Modelling in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Developing Countries : A System Dynamics Approach .,” CIB World Build. Congr. 2019, no. June, 2019.

- Hong, Y.; Hammad, A. W. A.; Sepasgozar, S.; Akbarnezhad, A. BIM adoption model for small and medium construction organisations in Australia. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, vol. 26(no. 2), 154–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhasan, S.; Kumar, B.; Thanikal, J. V. Effectiveness of implementing 5D functions of Building information modeling on professions of quantity surveying - A review. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, vol. 8(no. 5), 783–800. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B.; Cai, H.; Hastak, M. An assessment of benefits of using BIM on an infrastructure project. Int. Conf. Sustain. Infrastruct. 2017 Technol. - Proc. Int. Conf. Sustain. Infrastruct. 2017, 2017, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Azhar, “Building Information Modeling (BIM): Trends, Benefits, Risks, and Challenges for the AEC Industry,” 2011.

- Masood, R.; Kharal, M. K. N.; Nasir, A. R. Is BIM adoption advantageous for construction industry of Pakistan? in Procedia Engineering 2014, vol. 77, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazli, A.; Fathi, S.; Enferadi, M. H.; Fazli, M.; Fathi, B. Appraising Effectiveness of Building Information Management (BIM) in Project Management. Procedia Technol. 2014, vol. 16, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesároš, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Mandičák, T. Exploitation and Benefits of BIM in Construction Project Management. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2017, vol. 245(no. 6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Noor, M. N.; Junaidi, S. R.; Ramly, M. K. A. Adoption of Building Information Modelling (BIM): Factors Contribution and benefits. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. Manag. 2018, vol. 3(no. 10), 47–63. Available online: www.jistm.com.

- Al Hattab, M.; Hamzeh, F. Using social network theory and simulation to compare traditional versus BIM-lean practice for design error management. Autom. Constr. 2015, vol. 52, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda-Mena, G.; Crawford, J.; Chevez, A.; Froese, T. Building information modelling demystified: does it make business sense to adopt BIM? Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2009, vol. 2(no. 3), 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhil, A.; Alshawi, M. Client’s Role in Building Disaster Management through Building Information Modelling. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, vol. 18, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Park, H. K.; Won, J. D 3 City project - Economic impact of BIM-assisted design validation. Automation in Construction 2012, vol. 22, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Radosavljevic, M.; Bonen, B. A Building Information Modelling Based Production Control System for Construction; 2010; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Azhar, M. Khalfan; Maqsood, T. Building Information Modeling (BIM): Now and Beyond; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Damian, P. Benefits and barriers of building information modelling. 12th Int. Conf. Comput. Build. Eng. 2008, pp. 1–5. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2134/23773.

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, L. Integrating BIM and AI for Smart Construction Management: Current Status and Future Directions. In Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering; Springer Science and Business Media B.V., 01 Mar 2023; vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 1081–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinade, O. O. , Waste minimisation through deconstruction: A BIM based Deconstructability Assessment Score (BIM-DAS). Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, vol. 105, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-K.; Lee, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Venugopal, M.; Teizer, J.; Eastman, C. M. A Framework for Automatic Safety Checking of Building Information Models; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, B. , Comparative Analysis of Building Information Modeling (BIM) Patterns and Trends in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with Developed Countries. Buildings 2023, vol. 13(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrmann; Forster, C.; Liebich, T.; König, M.; Tulke, J. Germany’s Governmental BIM Initiative – The BIM4INFRA2020 Project Implementing the BIM Roadmap. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2021, vol. 98, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman; Teicholz, P.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM Handbook, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2011; vol. 6, no. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, W. M.; Olawumi, T. O.; Ho, A. M. L. Perceived benefits of and barriers to Building Information Modelling (BIM) implementation in construction: The case of Hong Kong. J. Build. Eng. 2019, vol. 25, 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P. A.; Wang, C. C. A Comparison of Using Traditional Cost Estimating Software and BIM for Construction Cost Control. In ICCREM 2014: Smart Construction and Management in the Context of New Technology - Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Construction and Real Estate Management; 2014; pp. 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H. Y.; Lopez, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Z. Comparative Analysis on the Adoption and Use of BIM in Road Infrastructure Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, vol. 32(no. 6), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanem Bayar, M.; Aziz, Z.; Tezel, A.; Arayici, Y.; Biscaya, S. Optimizing Handover of As-Built Data Using Bim for Highways. BIM Acad. Forum Conf., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Masood, R.; Kharal, M. K. N.; Nasir, A. R. Is BIM adoption advantageous for construction industry of Pakistan? Procedia Eng. 2014, vol. 77, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S. “D., a.M.Asce,” Build. Inf. Model. Trends, Benefits, Risks, Challenges AEC Ind. 2011, vol. 11(no. 3), 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffarianhoseini, A. , Building Information Modelling (BIM) uptake: Clear benefits, understanding its implementation, risks and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, vol. 75, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell; Cho, Y. K.; Cylwik, E. Learning Opportunities and Career Implications of Experience with BIM/VDC. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2014, vol. 19(no. 1), 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumbouya, L.; Gao, G.; Guan, C. Adoption of the Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Construction Project Effectiveness: The Review of BIM Benefits. Am. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2016, vol. 4(no. 3), 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migilinskas; Popov, V.; Juocevicius, V.; Ustinovichius, L. The benefits, obstacles and problems of practical bim implementation. Procedia Engineering 2013, vol. 57, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider; Khan, U.; Nazir, A.; Humayon, M. Cost comparison of a building project by manual and BIM. Civ. Eng. J. 2020, vol. 6(no. 1), 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancardo, S. A.; Capano, A.; de Oliveira, S. G.; Tibaut, A. Integration of BIM and procedural modeling tools for road design. Infrastructures 2020, vol. 5(no. 4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasnejad, B.; Nepal, M. P.; Mirhosseini, S. A.; Moud, H. I.; Ahankoob, A. Modelling the Key Enablers of Organizational Building Information Modelling (BIM) Implementation: An Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) Approach. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 2021, 26, 974–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latupeirissa, J. E.; Arrang, H. Sustainability factors of building information modeling (BIM) for a successful construction project management life cycle in Indonesia. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2024, vol. 9(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, M. F.; Razak, A. S.; Ameryounus, M. To BIM or not to BIM: A pilot study on University of Malaya’s architectural students’ software preference. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pittard, S.; Sell, P. BIM and Quantity Surveying, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxon OX14, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; D’Ascanio, L.; De Falco, M. C.; Ferrante, C.; Presta, D.; Tosti, F. BIM for infrastructure: An efficient process to achieve 4D and 5D digital dimensions. Eur. Transp. - Trasp. Eur. 2020, no. 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Huang, L.; Aziz, N. M.; Kamaruzzaman, S. N. Building Information Modelling (BIM) Capabilities in the Design and Planning of Rural Settlements in China: A Systematic Review. Land 2022, vol. 11(no. 10), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, N.; Peng, J.; Cui, H.; Wu, Z. A review of currently applied building information modeling tools of constructions in China. In Journal of Cleaner Production; Elsevier Ltd, 10 Nov 2018; vol. 201, pp. 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimpay, R.; Saghatforoush, E. Benefits of Implementing Building Information Modeling (BIM) in Infrastructure Projects. J. Eng. Proj. Prod. Manag. 2020, vol. 10(no. 2), 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara and Y. Abut, “The Benefits of Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Roads and Engineering Structures,” 10th Int. Baskent Congr. Phys. Eng. Appl. Sci., no. November, pp. 109–114, 2023.

- Mota, P.; Machado, F.; Biotto, C.; Mota, R.; Mota, B. BIM for production: Benefits and challenges for its application in a design-bid-build project. In 27th Annu. Conf. Int. Gr. Lean Constr. IGLC 2019; 2019; pp. 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D. W. M.; Olawumi, T. O.; Ho, A. M. L. Critical success factors for building information modelling (BIM) implementation in Hong Kong. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, vol. 26(no. 9), 1838–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Philip, L.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods For Business Students, Fifth Edit., no. Ninth edition; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International journal of medical education 2011, vol. 2., 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclnnes, J. An Introduction to Secondary Data Analysis with IBM SPPS Statistics, 1st Editio ed; SAGE Publications Ltd, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fellows, R.; Liu, A. Impact of participants’ values on construction sustainability. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Eng. Sustain. 2008, vol. 161(no. 4), 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán, Á. M.; Alberti, M. G.; Álvarez, A. A.; Trigueros, J. A. New perspectives for bim usage in transportation infrastructure projects. Appl. Sci. 2020, vol. 10(no. 20), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Benefit | References |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Enhancement | Enhance communication between project parties | [58,61,62,63] |

| Improve project information management | [64,65] | |

| Enhance collaboration between project parties | [60,66] | |

| Enhanced design analysis and efficiency due to produced element details | [61], [67,68,69,70] | |

| Improved human resources management | [61,71] | |

| Reduce reworking during construction | [61,62,72], [63,66] |

|

| Reduced redesign challenges during project implementation | [61,62,63] | |

| Improved site analysis | [61,62,63,66] |

|

| Greater productivity due to easy retrieval of information. | [64,66] | |

| Enhanced work coordination with subcontractors/supply chain | [66,73] | |

| Improved conflict detection | [60,64] | |

| ] | Enhanced management of security and safety information | [62,63,74,75] |

| Allowing accurate site logistics | [72], [61,62,63,66] | |

| Improved coordination in the construction phase | [62,63,76] | |

| Improved communication among various divisions of the same company | [58,61,62,63,77] | |

| Potentially improved whole life asset management | [61], [23,63,68,78] | |

| Output Improvement | Improved design quality | [63,72] |

| Earlier and more accurate design visualisation | [58,66,79] | |

| Generation of accurate and consistent 3D drawings at any stage | [78,80,81] | |

| Greater predictability of project time and cost | [82], [61], [63,68,79,83] | |

| Improved management of projects schedule milestones | [68,69,84] | |

| Fewer change/variation orders at the construction stage | [68,69,85,86] | |

| Efficiencies from reuse of data or details (enter once, use many times) | [68,69,87] | |

| Improved maintenance due to level of details produced | [85,87] | |

| Potentially improved maintenance of the infrastructure due to the as-built model | [85,87,88] |

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | No | 68 | 47.6 | 47.6 | 47.6 |

| Yes | 75 | 52.4 | 52.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 143 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).