1. Introduction

Fish barriers are important tools for the effective management of aquatic ecosystems, particularly with respect to fish movement through anthropogenic structures such as dams, weirs, and other obstacles. These barriers can have a significant impact on fish behavior, migration patterns, and overall biodiversity. Therefore, the proper design of such barriers, taking into account environmental conditions (discharge, flow velocity, optical properties of the water) as well as the fish species, is essential for developing effective management strategies that facilitate passage and maintain ecological integrity [

1,

2].

Barriers for controlling fish migration and invasion include physical structures which can block or delay fish movement [

1,

3,

4] and/or non-physical barriers which discourage fish from entering a given area [

5,

6].

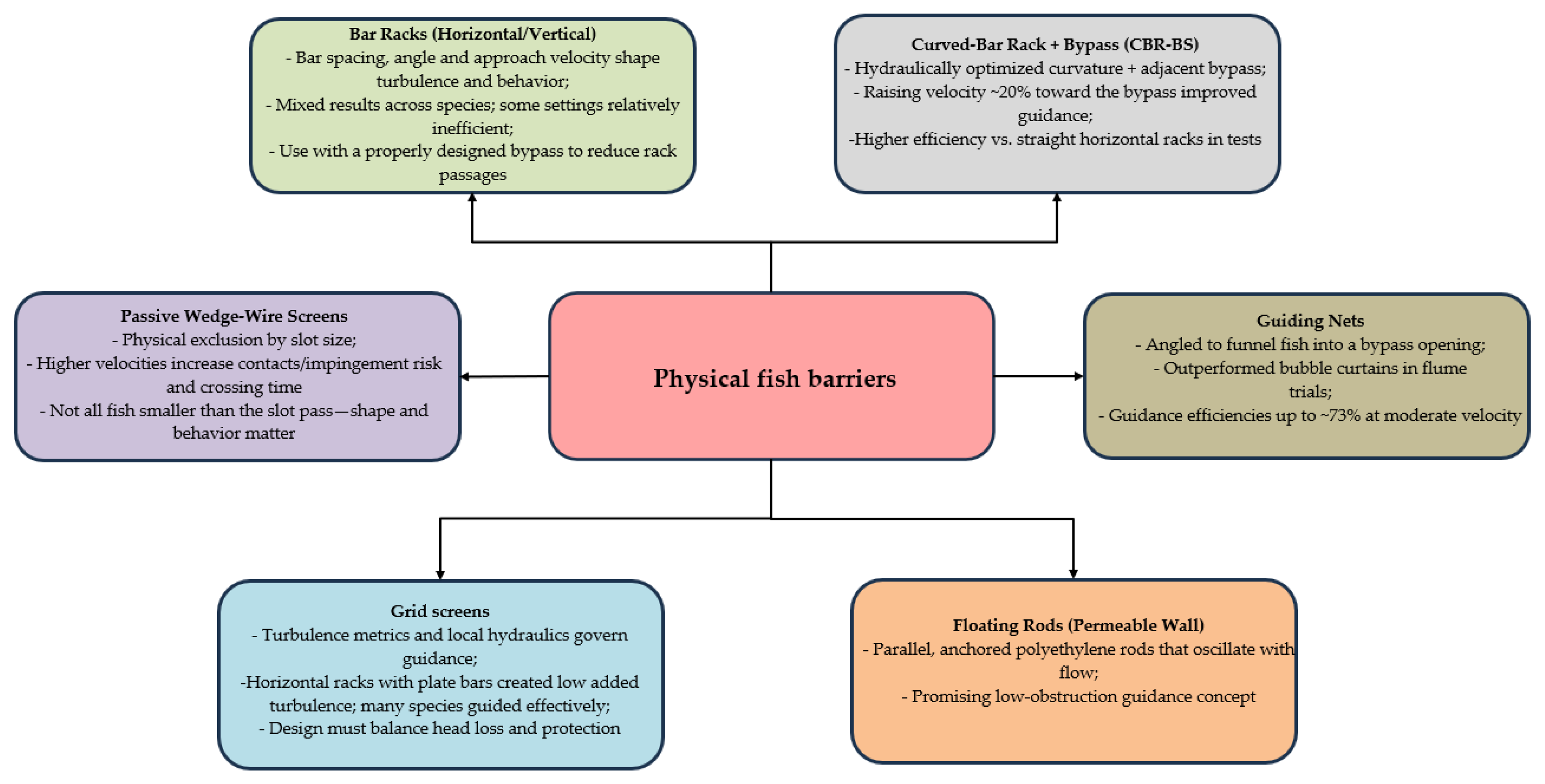

Physical fish barriers (PBs) are built structures that physically block, steer, or redirect the movement of fish using solid elements. Typical examples include gravity dams, screens, racks, and bypass systems, all of which either obstruct passage or redirect fish into specific routes. These barriers work through direct mechanical means, creating obstacles that fish must either overcome or avoid, depending on how they respond behaviorally to the surrounding hydraulic conditions [

1,

7].

Physical barrier technologies encompass several refined rack and screen designs. Curved-bar rack bypass systems (CBR-BSs), for example, use vertically oriented curved bars, set at specific angles, to shape flow patterns and guide fish towards dedicated bypass channels, providing a safer route downstream [

1,

8]. Horizontal bar racks (HBRs) apply a similar principle with angled horizontal elements that create hydrodynamic conditions favorable for fish guidance [

7,

8]. In addition, physical screens with carefully selected aperture sizes are used to prevent entrainment; however, their performance and consequences for target species are highly sensitive to design parameters such as bar spacing and approach velocity [

8].

Non-physical fish barriers (NPBs) use deterrents to influence how fish move, without relying on solid structures to block their way [

6]. These systems act on the sensory abilities of fish, making use of acoustic, visual, electrical, chemical, or hydrodynamic signals to encourage avoidance or attraction [

5,

6,

9], providing a management option that preserves hydrological continuity and navigation, while still aiming to guide fish movement through targeted behavioral modification.

An important NPBs category is the electric barrier, which has proven effective at discouraging fish movement. Parker et al. [

10] observed that fish often attempt to overcome electric dispersal barriers, demonstrating a strong motivation to move upstream despite the risks involved, including injury or death. This aligns with other studies showing that fish, especially those with a strong migratory instinct, will repeatedly attempt to cross such barriers until they succeed or incur harm. The implications of this behavior are significant, as they suggest that although barriers can be effective at preventing movement, they may increase stress levels and mortality within fish populations.

Bioacoustic and light-based systems, have emerged as innovative solutions for managing fish movements without imposing the physical constraints of traditional barriers [

5]. Flammang et al. [

11] highlighted the potential of bioacoustic bubble barriers and flashing lights to reduce the escape rate of species such as walleye (

Sander vitreus), although they noted that small-scale laboratory experiments cannot always be extrapolated to real operating conditions. Similarly, Noatch and Suski [

5] reviewed various non-physical deterrent methods, emphasizing their flexibility and adaptability for managing fish movements in line with ecological objectives (e.g., guide or selectively deter certain fish species), thereby increasing the effectiveness of fish migration control strategies.

The specific design and implementation of barriers according to the environment and target species play an important role in their effectiveness. Rahel and McLaughlin [

12] underscored the need for selective fish-passage methods that account for the ecological and behavioral traits of different species. This approach is important for conserving aquatic biodiversity while also controlling invasive species. Moreover, the study by Lemasson et al. [

13] indicated that fish schooling behavior can increase the risk (e.g., injury, mortality) for individuals attempting to traverse artificial barriers, suggesting that barrier design should also consider the natural behaviors of fish in order to minimize these risks.

The ecological implications of barriers are not limited to individual species, but also affect the dynamics of aquatic communities. For example, the presence of barriers can lead to shifts in fish community structure and reduced biodiversity, as observed by Enders et al. [

14]. The long-term consequences of barriers for native fish populations must be carefully analyzed, especially in the context of efforts to manage invasive species, a point also emphasized by Altenritter et al. [

15]. Balancing the prevention of invasive-species movements with the conservation of native fish populations is a complex challenge that calls for ongoing research and adaptive management strategies.

The main purpose of the present study is to provide an analysis of the most recent literature on the use of barriers for guiding fish. The study aims to classify and evaluate these barriers according to several elements, such as their type (physical and non-physical barriers), the environmental conditions under which they were tested (in the laboratory, in the field, or combined), and the fish species involved in these studies. Through this approach, the study offers a perspective on the effectiveness of each barrier type in various ecological contexts and identifies their potential advantages and limitations.

2. Methodology

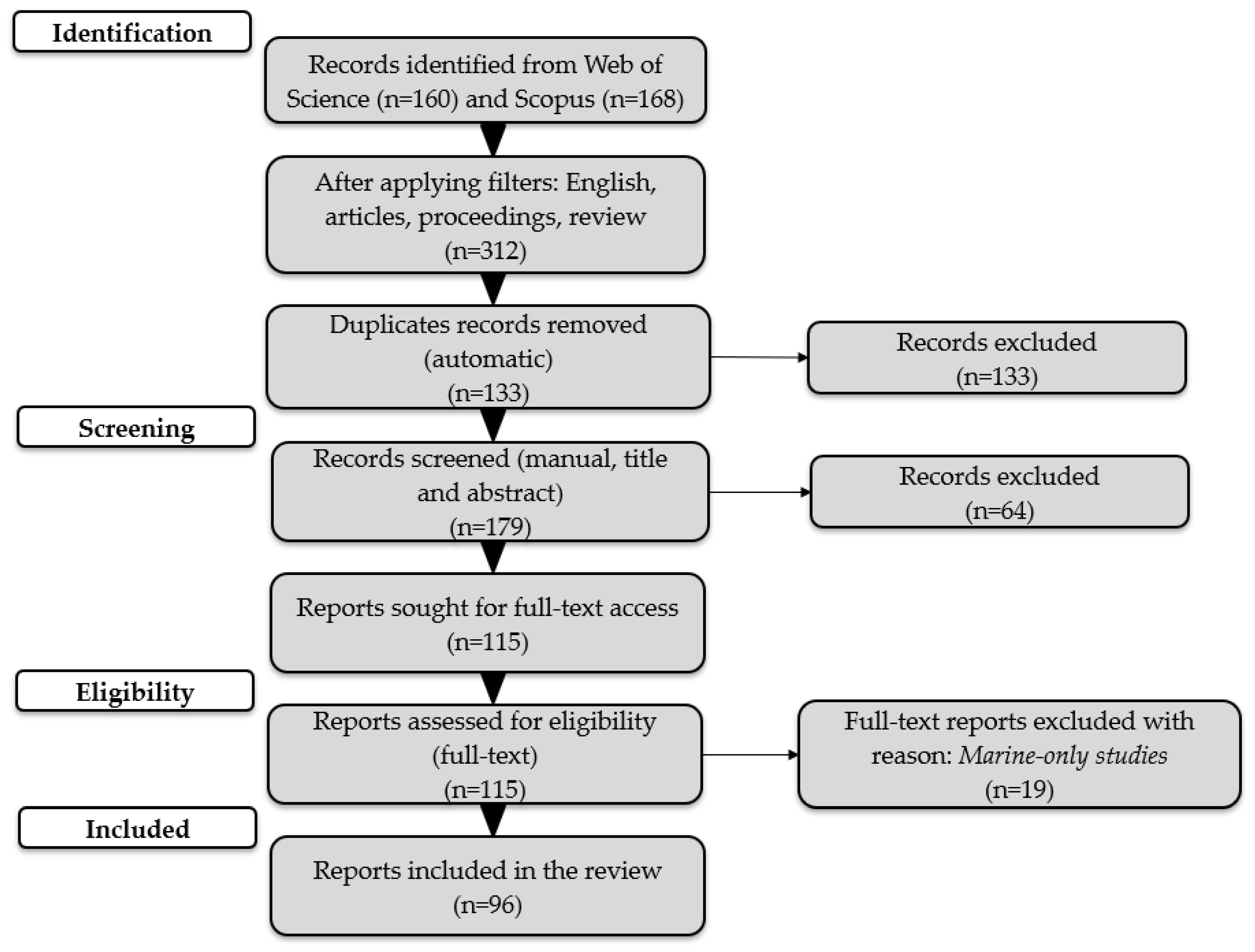

The systematic search of the literature was conducted on Web of Science Core Collection and Scopus, following PRISMA 2020 guidance (

Figure 1) [

16], complemented by manual screening of reference lists. The keyword strategy was: (“fish guidance” OR “fish deterrent” OR “fish passage” OR “fish migration”) AND (“behavioral barrier” OR “behavioural barrier*” OR “non-physical barrier*” OR “physical barrier*” OR “acoustic deterrent*” OR “sound barrier*” OR “bioacoustic*” OR “light barrier*” OR “visual deterrent*” OR “LED” OR “strobe light” OR “electric barrier*” OR “electrical deterrent*” OR “pulsed DC” OR “bubble barrier*” OR “bubble curtain*” OR “air curtain” OR “effluent plume*”). In total, 328 records were identified (WoS = 160; Scopus = 168). After applying filters (language: English; document types: article, review, proceedings), 312 records remained. Duplicate records were removed (n = 133) using EndNote v. 21.5, leaving 179 records for title/abstract screening; of these, 64 were excluded as irrelevant. We sought 115 reports for full-text access. All 115 full texts were assessed for eligibility, and 19 were excluded because they were marine-only studies. Ultimately, 96 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis.

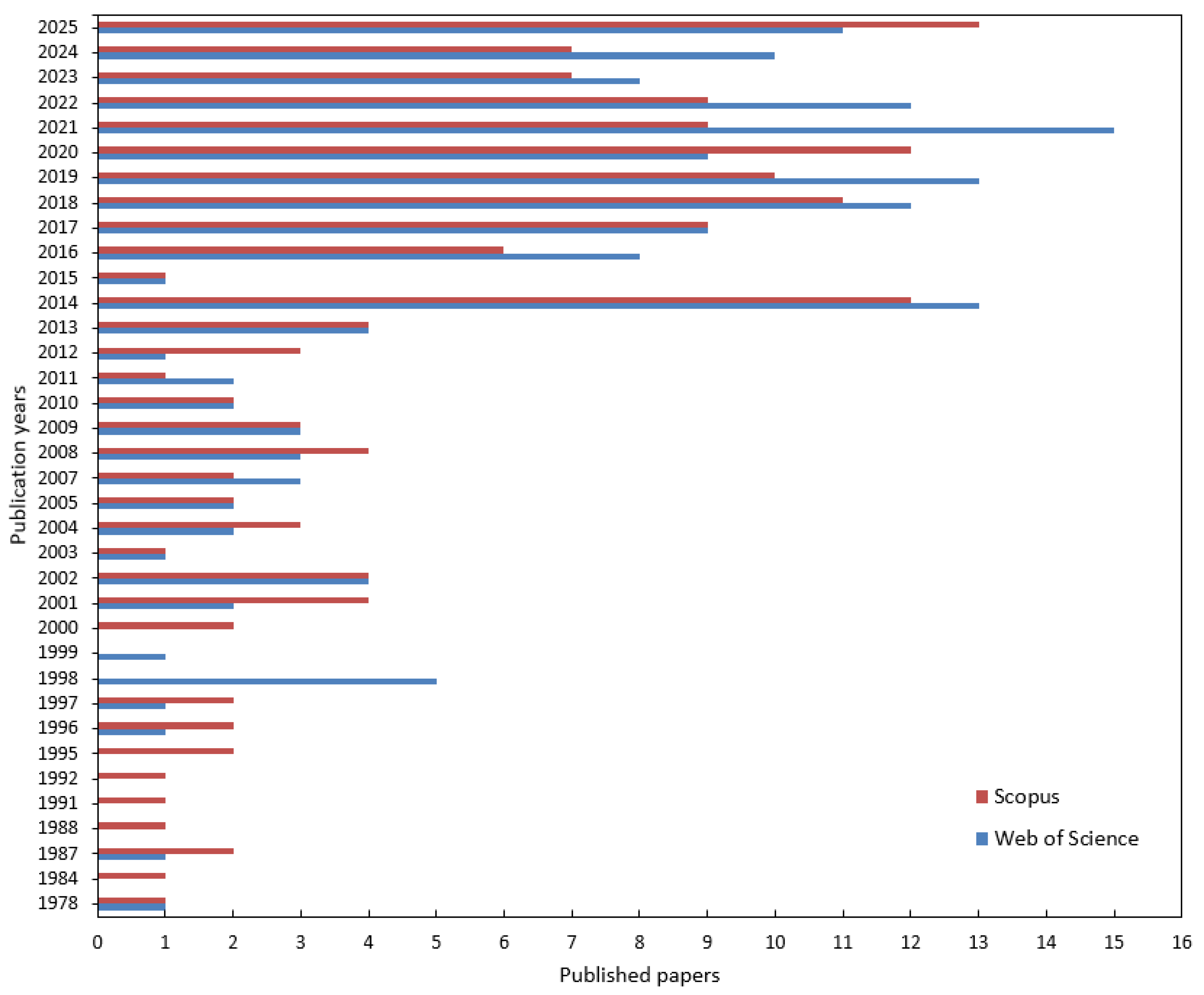

The temporal distribution of the retrieved records across Web of Science and Scopus is shown in

Figure 2. Output is sparse and sporadic before 2005, with a few early papers in the 1980s–1990s (including a small WoS peak around 1998). Rates rise sharply after 2014, show sustained growth from 2018 onward, and peak between 2020–2023. The partial counts for 2025 should be interpreted cautiously.

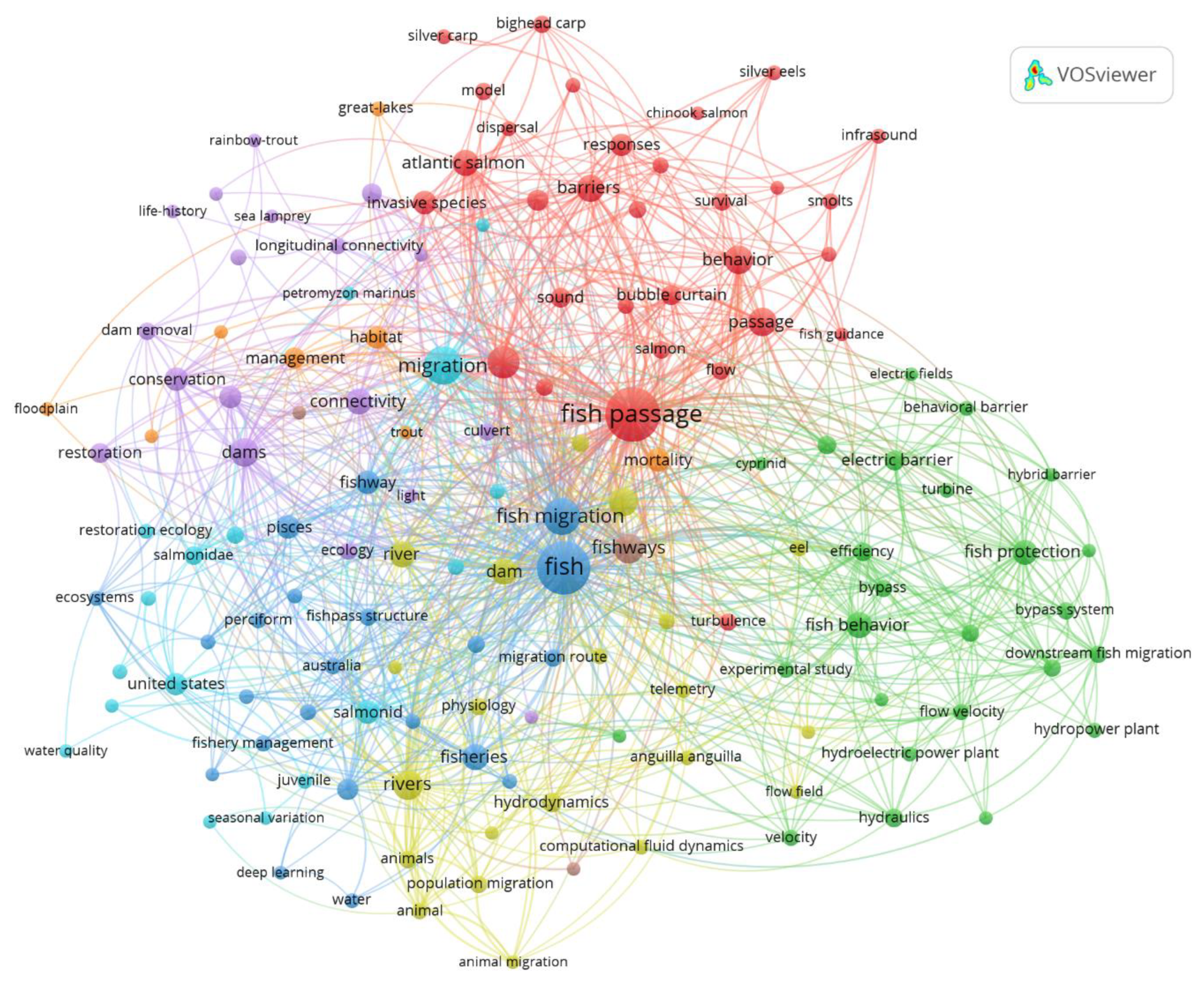

Figure 3 maps the co-occurrence of author keywords and shows a cohesive field organized around a few bridging terms: fish passage, fish migration, fishways, and fish, that link otherwise distinct research strands. The analysis identifies five main research clusters: i) an engineering/operations cluster (green) linking physical infrastructure (e.g., hydropower, hydraulics, and bypass systems) to the efficiency of NPBs at intakes; ii) a behavioral cluster (red) centered on deterrents (sound, bubbles, infrasound) and life-stage-specific responses; iii) a management/restoration cluster (blue–purple) spanning dams, dam removal, and connectivity; iv) a fisheries/biology cluster (light blue) grouping terms such as juvenile, salmonid, and water quality; and v) a hydrodynamics cluster (yellow) aggregating modeling concepts (computational fluid dynamics, flow field). Together, the map indicates that non-physical and physical (structural) barriers are technically anchored in hydraulics and facility operations, but conceptually linked to conservation and migration objectives through the central theme of fish passage.

3. Types of Fish Guidance Barriers

According to specialized literature, barriers, regardless of their type, can have both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, they help protect native fish species from invasive ones, preserving the natural structure of aquatic ecosystems. On the other hand, these barriers can hinder the natural migration of fish, fragment habitats, and negatively affect fish populations. Therefore, it’s important to carefully consider all potential effects of using barriers before implementing them.

A detailed analysis of recent data highlights a variety of physical barriers or non-physical barriers types used for controlling fish migration, each with its own specific advantages and limitations (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

Experimental studies have been conducted in controlled laboratory, semi-natural, or real-world conditions, each with defined parameters for evaluating the effectiveness of these structures. The main noticed results have shown significant differences in barrier efficiency depending on the fish species of interest, hydrodynamic conditions, and the physicochemical parameters of the water. A synthesis of this data, including the types of barriers used, specific experimental conditions, fish species studied, and the main results obtained, is presented in a concise manner in

Table S1—Supplementary material.

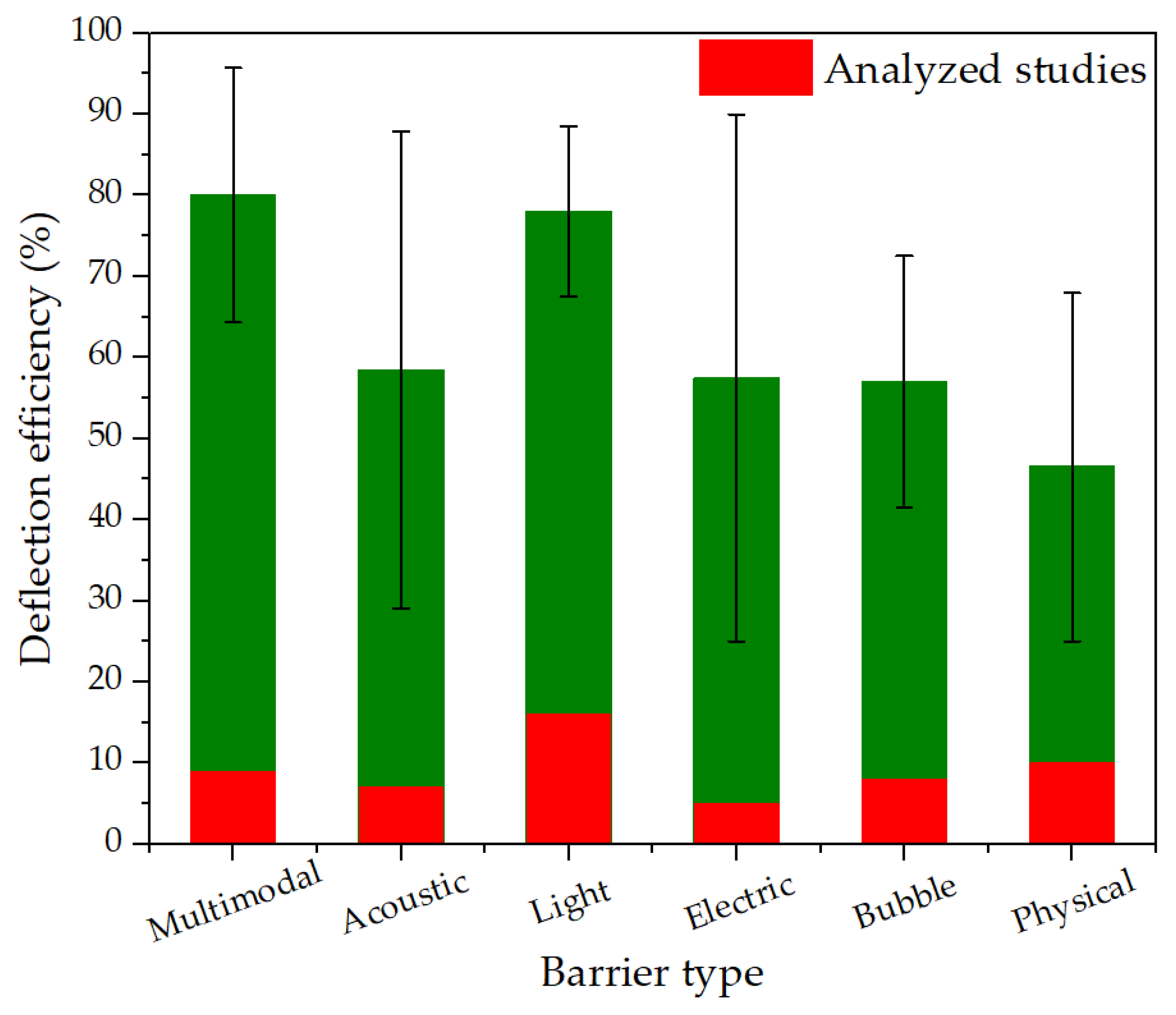

Figure 4 synthesizes deflection efficiency by barrier type. Multimodal systems achieve the highest mean efficiency (~80%) but with broad uncertainty, consistent with additive or synergistic cueing. Light-based deterrents follow (~77%) with moderate between-study variability. Acoustic and electric barriers perform at intermediate levels (~55–58%), with electric systems showing the widest dispersion, reflecting sensitivity to field strength, water conductivity, and body size. Bubble curtains cluster near ~56%, while structural devices have the lowest mean (~ 46%) and notable heterogeneity. Overall, performance is strongly device- and context-dependent, reinforcing the need for standardized reporting of device parameters and environmental covariates to allow fair comparisons across studies.

3.1. Non-Physical Barriers

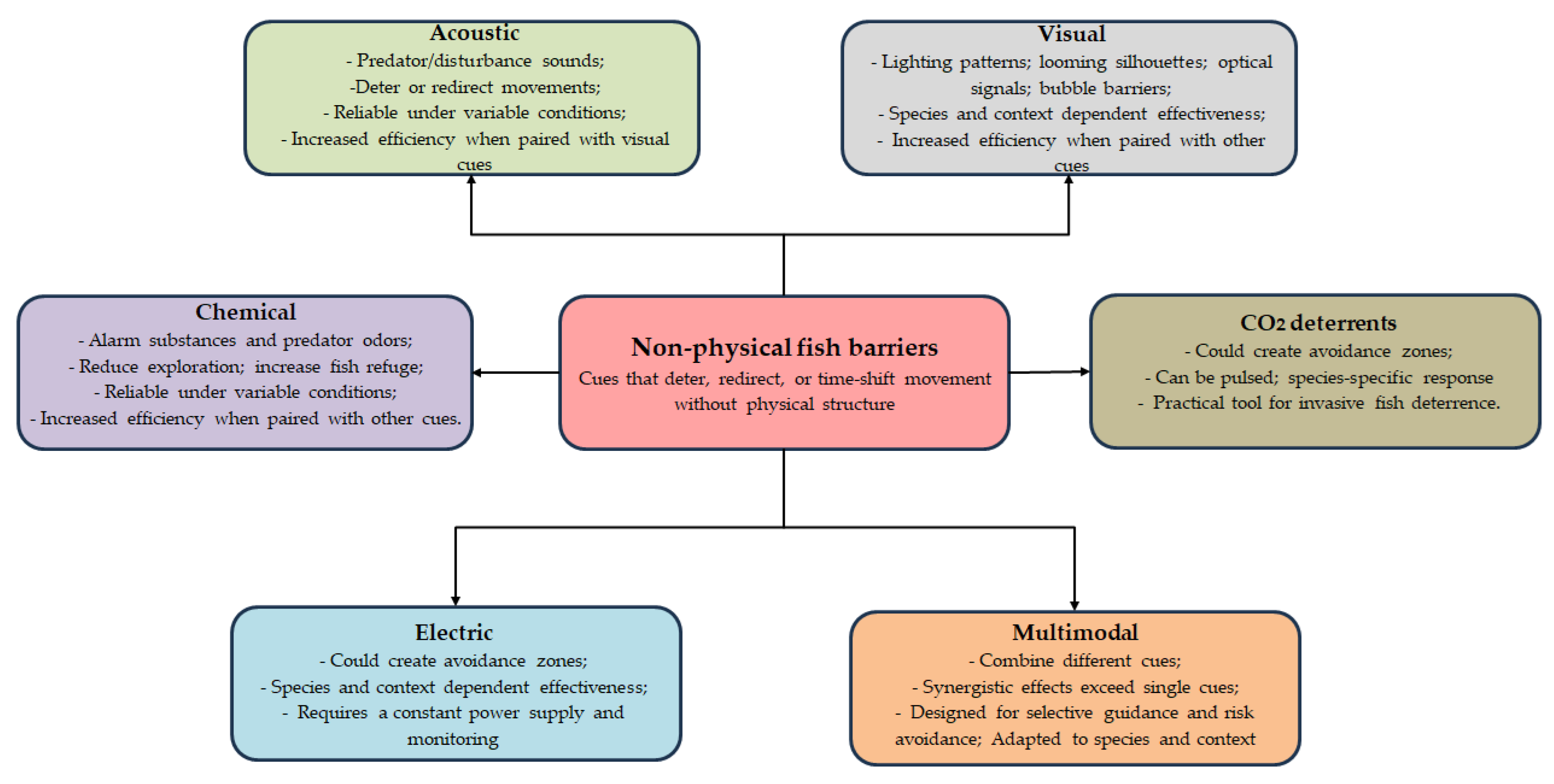

Non-physical fish barriers (

Figure 5), use sensory cues to deter, redirect, or temporally constrain movement without relying on physical structures. Grounded in how fish interpret environmental signals as proxies for predation risk, competitor presence, or habitat suitability, NPBs elicit adaptive changes in orientation, refuge use, exploration, and shoaling. In practice, non-physical cue, acoustic, visual, chemical, or multimodal, shift the probability and direction of movement, thereby reducing contact with high-risk areas or periods [

21]. Building on this work, the present synthesis integrates some results across cue types to clarify how NPBs operate, assess their robustness under environmental change, and identify where they are most effective for protecting native fishes, improving aquaculture practices, and establishing conservation corridors [

21,

22,

23,

24].

3.1.1. Light Barriers

Visual elements of non-physical barriers such as targeted lighting patterns, looming silhouettes, and high-contrast optical signals are powerful levers for influencing fish behavior. On their own, visual cues can elicit clear anti-predator or exploratory responses and when paired with mechanosensory or acoustic stimuli (e.g., visually apparent predator cues coupled with hydrodynamic or sound signatures), they often amplify deterrence [

21]. Because responses are strongly context- and species-dependent, multimodal designs typically yield larger shifts in refuge use, shoaling density, and spatial distribution, reducing entry into sensitive zones [

21,

25]. Importantly, vision-based effects are moderated by ambient light, background risk, and prior predation experience, which together influence both the intensity and direction of responses [

22,

25,

26]. In practice, visual barriers are best used as one layer of a multi-modal system to maximize deterrence and minimize habituation, particularly where fish rely on multiple cues for threat assessment [

22,

25].

A study led by Lenihan et al. [

27] examined the effectiveness of an intermittent light system (white-light LEDs with broad-spectrum emission from 425–725 nm) as non-physical barriers for guiding European silver eels (

Anguilla anguilla) during their downstream migration, preventing mortality caused by anthropogenic barriers such as dams. The results show that intermittent light effectively redirects eels toward safe routes, corroborating previous research on the effect of light on other eel species [

28]. The efficiency of the light array was estimated based on the mean proportion of eel biomass captured on treatment nights (P

on), relative to the mean proportion captured on control nights (P

off). The eel deflection efficiency (E) of the light array was estimated using the formula:

The experimental results clearly showed that silver eels exhibited a strong avoidance response to light stimuli (negative phototaxis) when the intermittent light system was active. This system proved highly effective, managing to divert 80.6% of the individuals studied. In addition, a significant difference in the size of captured eels was noticed: specimens caught on test nights were generally smaller than those captured on control nights. This result suggests that smaller eels had a weaker ability to avoid the illuminated area, whereas larger individuals demonstrated a superior ability to detect and bypass the light field [

27].

Applying the experimental results under real-world conditions constitutes a promising strategy for protecting this endangered species, contributing to conservation efforts and improving migratory success [

29].

In another study, has been shown that the low daytime light can block diurnal small-bodied fish: hardyhead (

Craterocephalus stercusmuscarum) and smelt (

Retropinna semoni) strongly avoided 0 lx zones, but modest lighting (~100–200 lx) overcame most avoidance [

30]. Bass (

Macquaria novemaculeata) preferred darkness, and silver perch (

Bidyanus bidyanus) responses were driven by current, not light. Field measurements showed that real culverts often had very low center lux values (<3) even under bright ambient conditions, indicating that many structures may substantially impede fish passage unless they incorporate daylight openings/skylights or artificial lighting tailored to the target species, while still limiting night-time light pollution that could disadvantage nocturnal fishes.

A study by Hansen et al. [

17] investigated the behavioral response of juvenile Chinook salmon (

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) to LED light spectra and intermittent light frequencies as a potential method for guiding fish in hydropower turbine areas or irrigation canals. The results showed that red light had a repellent effect during the day, causing fish to avoid areas near the light source, whereas blue and green light shown positive responses, with fish spending more time near the light source. At night, no significant differences in fish behavior were found with respect to the light spectrum used. Regarding the intermittent light frequency (2 Hz), it did not have a significant impact compared to steady light. Red light also remained repellent regardless of whether the light was flashing or steady. The implications for fish guidance suggest that red light used during daylight could help discourage fish from hazardous areas, while blue and green light could be used to direct fish toward safer routes.

A study performed by Tétard et al. [

9] evaluated a simple light-based guidance at the Poutès Dam bypass. A 50 W mercury lamp above the entrance created a small halo to influence Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar) smolts tracked by fine-scale acoustic telemetry. Smolt response depended on migration timing: early-season fish (before 15 April) tended to avoid the lit entry zone, yet those reaching it were more likely to pass under light; late-season fish (after 15 April) were attracted and retained near the entrance when lit, yielding substantially more passages at night (23 lit vs 6 dark during the experimental window). Statistical models confirmed a strong lighting × period interaction and significant increases in presence/retention under light late in the season. Overall, light can enhance bypass performance, but its effect reverses with developmental stage/season, underscoring the need to tune operations to migration phenology.

Artificially illuminated bridges could create steep light contrasts on rivers at night, as demonstrated by Vega et al. [

31]. Measurements on the Spree River showed under-bridge illuminance dropping to 9 mlx at an unlit span (vs 1100 mlx when lit underneath), and sky radiance varying across the route. These light-step changes can modify the behavior of eels which tend to avoid lit water and may be trapped in dark underpasses; salmon smolts may be attracted to lit areas, delaying migration and elevating predation exposure. The authors propose a bridge-lighting typology (rural/urban, lit/unlit roadway/underpass) to predict responses and urge better shielding and lower light levels to protect migratory fish.

Lin et al. [

32], using a 4 × 3 m barge-passage model, identified how induced flow, bubble curtains, and light color influence two stages of performance—attraction to the entrance and subsequent collection inside. In daytime, induced flow did not increase attraction in simple (univariate) tests (P = 0.836) and even reduced attraction in multivariate combinations; yet, it significantly improved the collection ratio (P = 0.046), supporting a two-step operating strategy: maximize attraction with no-flow, then switch flow on briefly to draw fish through the entrance. At night, flow became the dominant factor in the models (P< 0.001), but the highest attraction still occurred under a no-flow + no-bubbles + warm-white setting, illustrating that factor importance and optimal settings can diverge once interactions are considered. Warm-white (3000 K) was the only light that significantly boosted attraction relative to blue, yellow, or weak light, whereas lighting did not enhance collection. Bubble curtains strongly aggregated fish within the bubble zone (daytime P = 0.006) but did not increase attraction or collection, suggesting distraction rather than guidance under this geometry. Overall, for

Gambusia affinis, the most reliable recipe was to maximize attraction without flow (and with warm-white light at night), then activate flow briefly to maximize collection [

32].

3.1.2. Acoustic Barriers

Acoustic barriers are among the most mature non-physical tools for shaping fish behavior. Sound-based stimuli can deter movement, shift habitat use, and cue avoidance without installing physical structures, selectively guiding fish away from sensitive zones or toward safer habitats. Evidence also shows stronger, multimodal effects: pairing acoustic cues with visual stimuli evokes more pronounced anti-predator responses than either cue alone, boosting deterrence [

23]. Importantly, predator-associated sounds retain inhibitory or avoidance effects under variable ambient conditions, indicating resilience for real-world deployment. Disturbance- and predator-derived cues can further act as early warnings, altering foraging and refuge-seeking before direct encounters occur and thereby reshaping movement patterns [

33].

Unlike other stimuli, sound has the distinct advantage of transmitting information over long distances without being affected by factors such as water flow, turbidity, or variations in light levels, which makes it an effective solution for various ecological applications and for conserving aquatic ecosystems. Owing to this property, acoustic deterrent systems are implemented in strategic locations such as locks, dams, and intake canals to prevent biological invasions and protect ecosystems. These systems operate by emitting sound signals that influence fish behavior, causing them to avoid critical areas [

34].

Compared with other non-physical approaches, acoustic deterrents offer more consistent performance across variable conditions and allow precise temporal/spatial control. Moreover, loudspeakers are relatively inexpensive and require less power compared to electric barriers. In the event of a power outage, they can be powered by small backup generators or batteries. The lower cost also allows the installation of two independent sets of speakers, providing continuity if one system is damaged [

7].

A study by Wu et al. [

35] demonstrated that when grass carp (

Ctenopharyngodon idella) were exposed to a pure 100 Hz tone, they showed a strong and visible avoidance response to the test area, accompanied by a significant increase in swimming speed. Exposure to this low-frequency stimulus led to a considerably higher number of avoidance reactions over the 10-minute experiment (8.14 ± 1.44 min) compared to the control group, in which such reactions were much less frequent. These results suggest that low-frequency sounds play an essential role in inducing avoidance behavior in fish. The study also shows that broadband sounds that include such low frequencies could be extremely effective in influencing fish movements and could be used in practical applications to direct fish or prevent them from reaching certain areas. However, the use of a source emitting in the infrasound range (12 Hz) altered the movement behavior of the

European eel but did not have a significant influence on the number of passes through the passage [

19].

The use of broadband sounds (0.06–10 kHz) has proven to be an effective method for reducing the number of successful crossings by silver carp and bighead carp, as well as for both species combined. During the experiment, significant repulsion rates were recorded: 82.5% for silver carp, 93.7% for bighead carp, and 90.5% for the combined group. These results suggest that broadband sounds can have a strong impact on fish migratory behavior, diverting them from their usual routes and causing them to avoid passing through areas where the sound is emitted [

36].

Using sounds originating from human activities or sounds that mimic natural predators has proven effective in deterring fish from crossing certain areas. For example, broadband sounds generated by boat engines [

7,

37] or a sound that mimics an alligator’s roar [

37] create a disruptive acoustic environment that interferes with fish orientation. Fish perceive these sounds as danger signals, prompting them to avoid those areas and choose safer routes. Thus, implementing such acoustic techniques can be an effective solution to prevent fish from passing through hazardous areas, reducing the risks associated with their migration through zones with potential threats.

Another study [

38] tested a boat-motor sound deterrent broadcast from LL916C speakers, using 6-hour ON/OFF blocks to compare behavior under active vs. inactive sound. Water was very shallow (0.38–0.55 m) and culvert surfaces were highly reflective—conditions that caused rapid attenuation of low frequencies and degraded signal coherency, limiting the acoustic field’s reach. Behaviorally, silver carp reduced passage through the active speaker culvert (overall 29% of detected individuals crossed active vs 42% when inactive), while bluegill (

Lepomis macrochirus) and largemouth bass (

Micropterus salmoide) showed little consistent deterrence. The authors conclude that shallow-water settings and culvert acoustics can limit efficacy of sound-only barriers and suggest performance may improve under deeper-water conditions or with complementary measures.

In the study led by Jesus et al. [

6], the effectiveness of acoustic stimuli was tested for

Salmo trutta,

Pseudochondrostoma duriense, and

Luciobarbus bocagei. Two distinct acoustic treatments were used: a sinusoidal sound sweeping up to 2 kHz (sweep-up sound) and an intermittent 140 Hz tone. The test results showed that the type of sound used is important for achieving a fish avoidance index in the test area: (i) the avoidance index under the sweep-up treatment was high for

L. bocagei (95.9%) and

P. duriense (87.9%), in contrast to

S. trutta (8.7%); (ii) the 140 Hz tone shown a weaker repellent response, with low avoidance indices ranging from 14.7% for

S. trutta to 30.7% for

P. duriense. Overall, these results highlight the potential of acoustic stimuli to modify fish behavior, offering a promising tool for in situ conservation measures for fish populations, especially in the context of protecting them from hazards posed by hydropower dams. In addition, the study suggests that acoustic barriers can be tailored for selective use on target species, increasing their applicability in conservation management.

3.1.3. Electric Barriers

Electric barriers are used as a method to deter fish, guiding them away from hazardous or undesirable areas such as water intakes, hydropower turbines, or habitats invaded by non-native species. These barriers operate by generating an electric field of variable intensity that affects the fishes’ nervous system, causing them to avoid the area. The effectiveness of an electric barrier depends on factors such as voltage, frequency, and the sensitivity of the target species, with some species and larger individuals being more resistant to the effects of the electric field. Although they are an efficient and flexible alternative to physical barriers, they require a constant power supply and monitoring to prevent unintended effects on fish or other aquatic organisms [

18,

39,

40,

41].

The study led by Bajer et al. [

42] investigated the effectiveness of a semi-portable deterrence and guidance system (DGS) that included vertical electrodes to create a low-voltage electric field, designed to prevent the upstream spawning migration of common carp (

Cyprinus carpio) while simultaneously guiding them into a trap. This system was implemented in a natural stream, where it successfully discouraged carp from following their typical migratory route. The trap, measuring 5 × 25 meters and equipped with a net, provided an efficient means of capturing fish after they had been directed into the trap enclosure by the electric field. The results indicated that the DGS represents a promising solution for managing the migration of invasive species, as it not only discouraged carp from continuing their upstream movement but also provided a noninvasive capture method, minimizing environmental impact compared to traditional control methods.

Another study [

43] showed that the seasonal use of electric barriers (Pulsed DC Barrier) led to a reduction of over 99.8% in the invasion of adult sea lamprey (a predatory fish that lives in both marine and freshwater environments) into freshwater lakes, thereby protecting the local fish fauna. The study also showed that this barrier can also limit the access of lamprey larvae to freshwater areas.

The decision to use electric barriers must also account for the frequency and voltage of the electric field applied in the barrier, as well as the fish species and their size, because certain studies have shown that smaller fish (e.g., lake sturgeon) can acclimate more quickly than larger individuals to low frequencies (0.1–50 Hz) and low voltages (0.024–0.3 V), limiting the practical use of these electric barriers for deterring their passage [

18,

44]. Nevertheless, low-frequency electric barriers with short pulse widths have proven to be highly effective in guiding downstream-migrating European eel (

Anguilla anguilla) [

45].

The efficiency of an electric barrier is also influenced by other factors such as electrode arrangement (EA), pulse voltage (PV), pulse frequency (PF), and pulse width (PW), as shown in the studies presented in [

39,

40]. The study in [

45] was conducted in an outdoor, purpose-built concrete recirculating-water channel (dimensions: 10.8 m × 5 m × 1 m; water temperature: 20.2 °C ± 2.1 °C; dissolved oxygen: > 7.31 mg/L; water depth: 0.4 m), using different electric-barrier configurations to evaluate their effectiveness on the behavior of silver carp. The results showed that the electric barrier had a strong deterrent effect on silver carp, with the following key findings:

a) In the still-water test, the lowest deterrence rate was 84.48% across the nine treatments; for flowing-water tests with three different velocities, the lowest deterrence rate was 94.46%;

b) As PV, PW, and PF increased, the fishes’ avoidance response did not increase significantly;

c) Fish blocking increased as frequency increased, but without statistical significance;

d) Under flowing-water conditions, water velocity reduced fish sensitivity to electricity during migration; fish preferred to remain near the two sides of the tank (where conditions were more static);

e) As water velocity increased (to 0.3 m/s and 0.5 m/s), the deterrent effect of the electric barrier on silver carp initially increased and then decreased. Silver carp exhibit positive rheotaxis at water velocities between 0.4 and 0.6 m/s;

f) The number of silver carp attempting to cross increased significantly with fish length. Larger fish require a lower current impulse per unit mass, resulting in stronger upstream movement;

g) Different electrode configurations led to significant differences in the number of injuries of experimental fish. When electrode spacing was 80 cm and the electrodes were placed perpendicular to the flow direction, the number of injured fish was significantly higher than when spacing was 160 cm or the barrier was inclined;

h) When silver carp cross the electric barrier, their bodies tilt at an angle to it, rather than crossing perpendicularly, in order to reduce potential energy;

i) When fish were exposed to a strong electric field, they escaped in a disorganized manner, exhibiting two types of behavior: accelerated flight and disorientation.

3.1.4. Bubble Barriers

Bubble barriers are an innovative solution for guiding and deterring fish in certain river areas, with both advantages and disadvantages. Advantages include lower installation and maintenance costs compared to traditional physical structures. They also do not fully obstruct water flow and are less invasive to the aquatic ecosystem. In addition, bubble barriers can be easily adjusted or relocated to meet specific project needs. On the other hand, their effectiveness can vary depending on factors such as current velocity, the target species, and hydrological conditions. In rivers with moderate to high discharge and strong turbulence, the deterrent effect may be reduced. The continuous power demand to generate bubbles and maintain the equipment is another drawback, especially in remote areas where access to electricity may be limited [

46,

47].

Although bubble barriers can guide or restrict certain fish species, they are not a universal solution. Improving their design—by adjusting bubble size and density or integrating sound and light stimuli—could enhance their capacity to influence fish behavior. Such modifications could make bubble barriers more reliable tools for protecting aquatic ecosystems, reducing the spread of invasive species, preventing fish from entering dangerous areas, and supporting conservation efforts in rivers and lakes [

48,

49].

Leander et al. [

49], in a study conducted both under laboratory conditions and in a real flowing-water environment (a river), examined the combined influence of air bubbles, light, and sound on the migratory behavior of juvenile Atlantic salmon. The results showed that bubble barriers can efficiently divert migrating juveniles with high effectiveness in both controlled and natural settings. In the laboratory, the deviation success rate was 95%, while in flowing water, effectiveness remained high at 90%. Notably, this is nearly double the efficiency of an existing physical barrier that covers the first two meters of the water column yet yields a deflection rate of only 46%. Interestingly, when tested in complete darkness, the bubble barrier did not influence the migration of juveniles through the channel. This suggests that visual cues play an important role in the repellent effect of bubbles, as opposed to mechanical or auditory influences. These results underscore the potential of bubble barriers as an effective, low-maintenance, low-cost alternative to traditional physical structures used to guide salmon away from high-mortality passages such as hydropower turbines.

In another study [

46], a 100-m bubble barrier (perforated hose with 3-mm perforations) installed across a narrow river section was used to quantify how effectively the barrier guides the downstream migration of Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar) and brown trout (

Salmo trutta), and to compare this effectiveness with that recorded for Atlantic salmon juveniles. The results shown that more than twice as many salmonids chose the alternative fish route when the bubble barrier was activated. This was true for both salmon juveniles and brown trout, suggesting that bubble barriers can be used to guide salmonids at different life stages in rivers with discharges greater than 500 m

3/s. Moreover, the bubble barrier cost under €10,000—far below the estimated €28–35 million required to install 165-m guidance screens in a river of similar size.

In a controlled flume with nocturnal, PIT-tracked silver eels, a Kevlar net barrier consistently outperformed the bubble curtain [

50]. The net increased passage rate by ~68% vs. control, achieved the highest guidance efficiencies (up to 73% at 0.7 m·s

−1), funneled eels along the barrier with few downstream penetrations, and repelled them more effectively (more U-turns). The bubble curtain did not raise passage rates above control and showed many downstream penetrations; cameras recorded notably more eels behind the bubbles than in control runs. Velocity (0.1–1.0 m·s

−1) did not affect passage rate, while larger eels were less likely to enter the bypass. Overall, in this study, for downstream guidance of European eel, a physical net was effective, whereas a stand-alone bubble curtain was not.

One example is the use of a bubble-barrier system in which air and CO

2 are alternated to effectively block species such as common carp (

Cyprinus carpio, an invasive cyprinid) and black bullhead catfish (

Ameiurus melas) [

48]. Adding CO

2 discouraged common carp from crossing: the air-bubble barrier blocked 71 ± 40% of fish but did not significantly reduce crossings, whereas CO

2 barriers achieved blocking rates of 84 ± 32% at a low CO

2 level (30 mg/L) and 77 ± 28% at a high level (100 mg/L), significantly reducing crossings compared to the absence of a barrier. The presence of CO

2 in the bubble barrier also caused black bullhead to spend more time upstream than during inactive-barrier periods and to move further upstream, away from the CO

2 bubble barrier.

Non-physical deterrence using CO

2 and related chemical strategies has emerged as a practical way to deter invasive fishes without altering flow regimes, mainly by creating avoidance zones and triggering rapid, reversible flight responses. Syntheses of the evidence highlight that CO

2 can be effective for certain invaders but stress the need to balance deterrent performance with ecosystem and welfare considerations [

51,

52]. Field trials show that CO

2 injections can deter target species and that performance can be improved through pulsed delivery and shaped concentration gradients, which may extend barrier operation while mitigating downstream effects [

52,

53]. Because CO

2 sensitivity varies across species and individuals—and habituation or avoidance learning may develop—deployment should take into account the results of the species-specific experimentation and couple it with robust monitoring [

51,

54].

3.1.5. Effluent Plumes

The study by Winter et al. [

55] investigated the impact of effluent plumes from wastewater treatment plants on the migratory behavior of European silver eels (

Anguilla anguilla). The research addresses a significant gap in understanding how non-physical barriers, such as effluent plumes, can influence the migration patterns of aquatic species. Despite the importance of migration to the eel life cycle, the effects of these plumes have largely been overlooked in prior studies. The authors monitored the behavioral responses of 40 acoustically tagged silver eels as they encountered an effluent plume from a wastewater treatment plant during their downstream migration in the Ems Canal, Netherlands. The results indicated that the presence of the effluent plume induced significant behavioral changes. Specifically, the eels exhibited avoidance behavior, suggesting that effluent plumes could act as a barrier to migration. This avoidance could lead to delays in their downstream movement, affecting overall migratory success and survival rates.

3.1.6. Chemical Barriers

Chemical cues and kairomones can also be used as non-physical barriers, capitalizing on fish’s inherent sensitivity to chemical signals in their aquatic environment. Alarm cues released by injured conspecifics (known as alarm substances) can rapidly depress activity, heighten sheltering, or modify schooling behavior to prevent entry into cue-rich zones [

56,

57,

58]. Predator-derived kairomones elicit responses involving reduced exploration, increased vigilance, or changes in vertical/horizontal positioning, which can reduce the allure or accessibility of specific areas to fish [

21,

57,

59]. Also, the chemical landscape can be utilized to create non-physical barriers by forming chemically salient risk environments, either as standalone cues or in combination with visual/acoustic stimuli, to enhance avoidance or refuge-seeking behaviors [

21,

25,

33,

57].

3.2. Physical Barriers

Physical barriers (

Figure 6) fragment rivers and disrupt the movements of both migratory and resident fishes [

2,

60]. Effective guidance systems address this by steering fish around obstacles with structures tuned to species-specific swimming abilities and local flow conditions [

2,

61]. Design typically begins at the entrance, which must attract fish and channel them into the passage, with innovations like vertical-slot geometries improving accessibility [

62,

63]. Downstream, bypass channels and other guidance elements help divert fish from hazardous zones such as turbines [

64,

65], while targeted devices, e.g., triangular baffles in culverts, can create low-velocity corridors that aid upstream movement [

66]. Performance remains species- and context-dependent, designs optimized for larger fish may fail smaller-bodied species, and behavioral factors such as light and substrate also influence movement [

30,

67]. Successful fish passage requires an integrated approach that combines engineering, ecology, and policy, supported by adaptive management and monitoring to sustain effectiveness at landscape scales [

68,

69].

3.2.1. Grid Screens

In the study presented in [

70], the efficiency of fish guidance grids was investigated, focusing in particular on the influence of flow turbulence on migratory behavior. The study was carried out in a controlled environment using an experimental hydraulic flume, where various grid configurations and flow conditions were tested to assess how different turbulence parameters (e.g., mean velocity, spatial velocity gradient—SVG and Reynolds stress) affect fish-guidance efficiency. These hydraulic conditions influence guidance efficiency and determine head losses for the flow directed to hydropower turbines. Designing an effective fish-passage system for migration and a cost-efficient screening system requires an in-depth understanding of fish behavior under diverse hydraulic conditions, as well as the relevant dynamic characteristics of the flow.

Turbulence intensity and structure have a significant impact on fish behavior, with certain screen configurations leading to improved guidance of the studied species—Spirlin (

Alburnoides bipunctatus), Barbel (

Barbus barbus), Nase (

Chondrostoma nasus), Brown trout (

Salmo trutta fario), Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar), and European eel (

Anguilla anguilla)—toward diversion systems [

71]. The hydraulic and fish-guidance efficiencies of a horizontal bar rack bypass system were tested in a large laboratory flume, with configurations including plate-type bars, bar spacings of 15 and 20 mm, and a rack angle of 30°. Tests on the fish species showed that the HBR had a minimal impact on the velocity field and turbulent kinetic energy. The bypass affected the velocity field only locally, and a high proportion of species were effectively guided and protected. However, fish could be fully protected only when their body width exceeded the bar spacing, while smaller fish exhibited only partial behavioral guidance toward the bypass. Guidance efficiency varied by species and was largely influenced by the ratio of fish width to bar spacing. Approach flow velocity did not significantly affect either bypass entries or rack passages; however, a higher entrance velocity at the bypass inlet increased both refusals and rack passages, indicating the need for an adequate bypass at the downstream end of the rack to reduce passage risks.

In another study [

8], juvenile Chub (

Squalius cephalus) and Barbel (

Barbus barbus) displayed distinct swimming patterns in response to different turbulence levels, suggesting that optimizing screen design could improve downstream migration success.

Beck et al. [

1] investigated a horizontal bar rack with a bypass section (HBR-BS). Results showed that velocity and pressure gradients between the HBR bars and up to roughly 40 mm upstream of the rack were particularly high, showing an avoidance response in most tested fish species. However, European eel (

Anguilla anguilla) and, to some extent, brown trout (

Salmo trutta) showed significantly weaker reactions to the hydrodynamic cues of the HBR-BS. Approach velocity (U

0) within the tested range (0.5–0.7 m/s) did not significantly influence fish-guidance efficiency, but it did affect refusal rates and rack passages. A higher approach velocity (0.7 m/s) increased refusal rates and reduced passages through the rack, reflecting a stronger deterrent effect of the hydraulic conditions. In addition, increasing the ratio between the velocity at the bypass entrance and the approach velocity (velocity ratio VR) from 1.2 to 1.4 significantly reduced bypass entries while increasing rack passages. These aspects underscore the need for an optimized bypass design. The HBR-BS functioned effectively as a mechanical guidance barrier for Spirlin (

Alburnoides bipunctatus), Barbel (

Barbus barbus), Nase (

Chondrostoma nasus), and Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar), achieving high fish protection and guidance efficiencies (>75%) for the tested sizes and life stages, while having a reduced or negligible behavioral effect on brown trout and European eel. Moreover, protection and guidance efficiencies for Nase, Spirlin, and Atlantic salmon were significantly higher with the HBR-BS having larger bar spacing (bs = 50 mm) compared to smaller spacing (bs = 20 mm), while barbel and brown trout showed similar responses to both systems [

1].

Moldenhauer-Roth et al. [

72] tested a full-scale (1:1) model of a standard rack with 90-mm bar spacing, modified by using the rack as an electrode and adding a second row of electrodes 142 mm downstream. A controlled voltage of 44 V was applied, and the resulting electric field was numerically simulated. Fish experiments were conducted in an experimental channel using brown trout (

Salmo trutta), European chub (

Squalius cephalus), and European eel (

Anguilla anguilla). In the absence of electrification, the rack provided no fish protection. With electrification, fish protection efficiency (FP)E for European chub reached 78% at a flow velocity of 0.15 m/s and 95% at 0.6 m/s. For eel, FPE was 92% at 0.3 m/s and 76% at 0.6 m/s. Brown trout showed no avoidance reaction to the electric field. Given the high protection efficiency for eels and cyprinids, this electrified rack design represents a promising solution to reduce fish passage through the turbines of large hydropower plants [

72].

3.2.2. Passive Wedge-Wire Screens

Carter et al. [

73] evaluated the influence of passive wedge-wire screens with different slot sizes (1, 2, 3, and 5 mm) and water velocities (0, 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2 m/s) on passage and behavior of European eel juveniles of different sizes (60–80 mm and 100–160 mm). To physically exclude eels, 1 and 2 mm screens were used for 60–80 mm eels and 100–160 mm eels, respectively. At a flow velocity of 0.2 m/s, up to 90% of 60–80 mm eels and 100% of 100–160 mm eels became captured on the screen. This velocity also increased both the number of contacts with the screen and the time to establish contact. A small proportion (9.2%) of the 60–80 mm eels did not approach the screen due to migratory separation, and eels smaller than the screen opening did not always pass through it, suggesting that other factors may influence passage.

3.2.3. Floating Rods

A system consisting of a series of parallel, equally spaced, polyethylene floating rods [

74], at equal distances and anchored to the riverbed, which oscillates with the flow, created a “permeable wall” designed to guide fish away from the hydroelectric power plant’s turbines. A unique pilot test with 106 downstream-migrating Atlantic salmon juveniles in a large experimental channel demonstrated the barrier’s effectiveness in discouraging fish from crossing it. Only 5.7% of fish passed through the barrier downstream. Most fish remained upstream (51.9%), while the rest followed the barrier downstream to the end of a bypass ramp (39.6%).

3.2.4. Corner Baffles

Cabonce et al. [

66] showed that small corner baffles can create usable low-velocity pathways and resting pockets, allowing small-bodied fish to ascend culvert barrels under sub-design flows. By contrast, plain baffles produced strong recirculation and flow reversal that disoriented fish and impaired passage, whereas simple cavity ventilation (a 13-mm hole) markedly dampened reversal, reduced fatigue, and improved endurance. Effective configurations matched baffle height to fish size, used moderate spacing to link wakes into a continuous corridor, and kept baffles small relative to design-flow depth to limit impacts on culvert capacity.

4. Gaps and Future Prospects

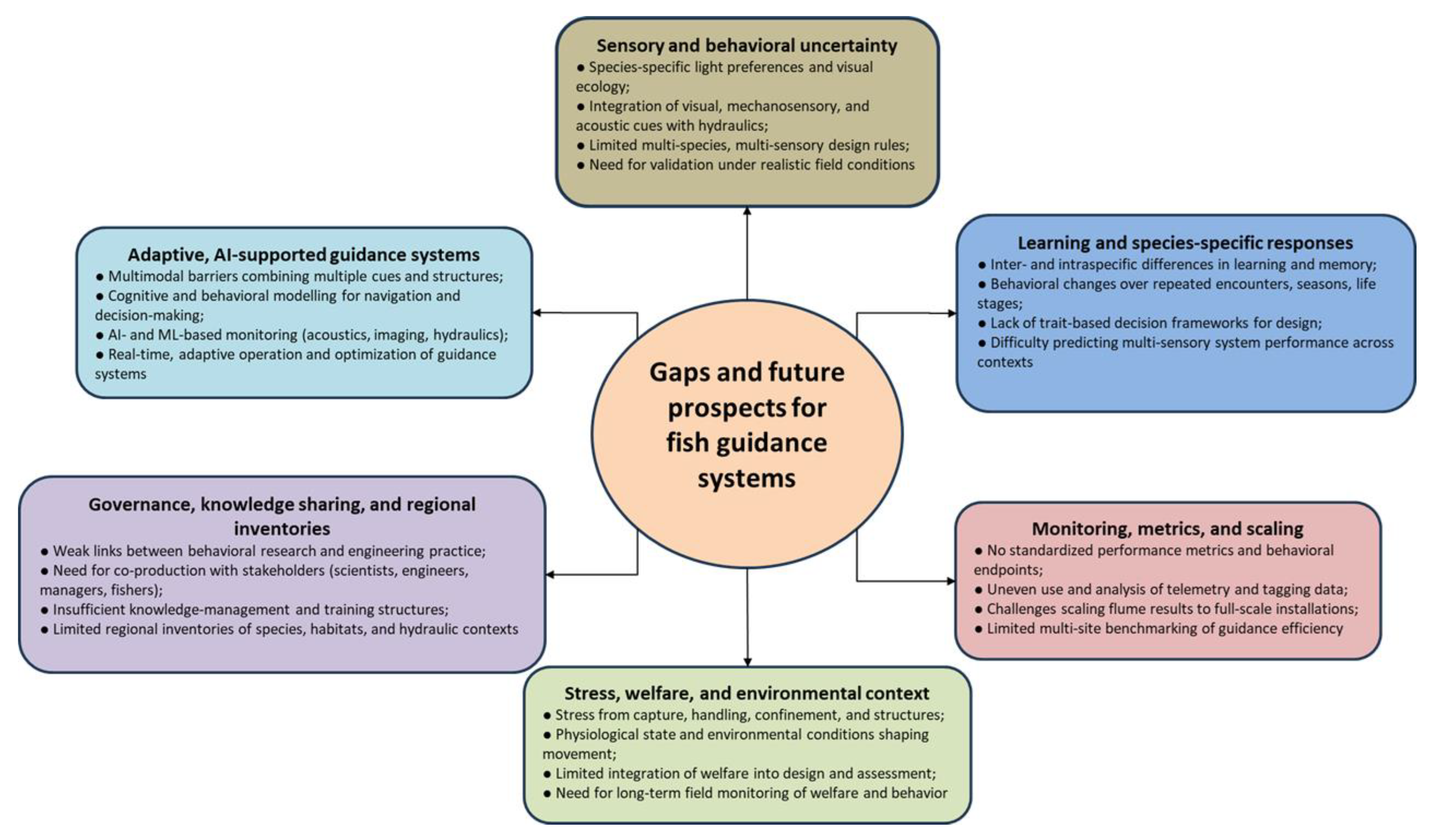

Why fish do or do not follow guidance systems depends on how they perceive and interpret their surroundings: vision and other senses, local flow fields, microhabitat cues, stress levels, and species-specific learning and decision-making. Despite considerable progress, several key gaps still limit the reliability and transferability of both non-physical and physical barriers (

Figure 7). These gaps fall broadly into sensory and behavioral uncertainty, hydraulic and structural constraints, monitoring and metrics (including welfare), and governance and knowledge transfer, with emerging opportunities for data-driven, machine learning (ML)and AI-enabled guidance systems.

4.1. Sensory and Behavioral Uncertainty

Light plays an important role in downstream movement decisions. Brightness, spectral composition, contrast, and temporal patterning can all act as behavioral modifiers, yet species differ markedly in their visual ecology and the contexts in which light becomes a barrier or a cue [

21,

75]. The structure of the eye, including retinal organization and visual acuity, directly affects how fish respond to artificial light; interspecific differences, such as the specialized visual regions described for Japanese smelt (

Hypomesus nipponensis), suggest that light-based measures will not generalize across species without adjustment [

20,

76]. Visual illusions and designed patterns can bias habitat choice and show that carefully constructed visual cues can attract or repel fish, particularly when combined with hydraulics [

77,

78]. These effects are further shaped by flow, water clarity, shadows, and microhabitat patterns, with studies showing that small-scale habitat mosaics can shift choices near structures [

79]. Taken together, the evidence points to clear gaps: we still need multi-species syntheses of light preferences and adaptation, a stronger framework for how visual cues combine with other senses, and quantitative, species-informed design rules for light-based guidance that remain effective under realistic turbidity, residence times, and day–night cycles, supported by field validation that links behavior to device performance [

9,

21,

30,

32,

61,

63].

Fish rarely rely on a single sense. They integrate what they see, feel, and hear, and they do so within the constraints imposed by local hydraulics. Mechanosensory input, captured through the lateral line, shapes how fish react to flow changes, screens, and bypass entrances [

78]. Hydroacoustic and substrate-borne stimuli, particularly particle motion and sound pressure, can further modify movement patterns and the effectiveness of deterrents [

23,

80]. Because all of these cues are filtered by the hydraulic context (velocity gradients, turbulence, recirculation zones), linking behavior to flow requires explicit experiments and models. Recent work has begun to formalize species-specific triggers for downstream swimming under turbine-like conditions [

81] and to demonstrate why on-site tracking combined with 3D numerical modeling is needed to set realistic boundary conditions for design [

65]. Engineered cues can, in principle, bias the movement of whole groups (e.g., biomimetic robotic fish influencing zebrafish shoals [

82]), but how to scale such concepts to real rivers and intake structures remains unclear. This underlines the need for field-tested, scalable devices that retain their effectiveness across species and flow regimes [

1]. Evidence that visual illusions and habitat cues can exploit perceptual biases [

77] also needs to be tested under dynamic conditions (e.g., changeable light, turbidity, and daily cycles—to avoid overestimating lab-based performance [

9,

75,

77].

4.2. Learning and Species-Specific Responses

Behavioral uncertainty is further amplified by interspecific and intraspecific differences in learning, memory, and responses to novel structures. Experiments in captivity show that species differ in how quickly they learn to avoid or use new microhabitats and visual cues; this means that guidance effectiveness can shift over time as fish gain experience [

79]. Broader syntheses of fish passage science emphasize the need for trait- and context-explicit design, yet a widely accepted trait-based decision framework that systematically tailors guidance solutions to the dominant species at a site, and accounts for variability within species, is still lacking [

2,

75,

83]. Another key gap concerns durability: we often document immediate reactions to light, flow, or visual stimuli, but much less is known about how these responses persist across repeated encounters, seasons, or life stages, even though these dynamics have obvious implications for long-term performance [

1,

81]. Overall, it remains difficult to predict how multi-sensory guidance systems will work across species and environments, which limits the development of reliable, generally applicable designs. Addressing these calls for a new, comprehensive framework that explicitly incorporates learning, memory, development, and social behavior, and that is tested under real-world conditions with a broad range of species and water conditions [

34,

35,

57].

4.3. Monitoring, Metrics, and Scaling from Laboratory to Field

On the measurement side, the lack of standardized metrics and multi-site benchmarking for guidance performance is a major constraint. There is a clear need for harmonized protocols that quantify behavioral responses, such as approach rates, bypass uptake, and hesitation time, under comparable hydrodynamic regimes and across species [

78,

79]. In the absence of such standards, comparisons across sites or between devices remain largely qualitative, slowing down synthesis and policy transfer. Telemetry and tagging technologies can reveal detailed movement patterns and behavioral triggers around guidance structures, but their deployment is uneven and analytical approaches differ between studies, which makes it hard to build a consistent evidence base.

Passive acoustic localization offers one route to estimating movement at larger scales, but field applications require careful calibration, adequate receiver density, and standardized workflows that connect high-resolution movement tracks to performance metrics for specific devices across diverse river systems [

84,

85]. Similarly, curved-bar rack and bypass systems show substantial promise, yet validated field performance metrics and robust rules for scaling from flume experiments to full-scale installations are still limited, restricting our ability to generalize results [

1,

2].

4.4. Stress, Welfare, and Environmental Context

Stress and welfare represent another underexplored dimension. Acute and chronic stress associated with capture, handling, confinement, and exposure to artificial structures can reshape behavior and thereby alter guidance outcomes. Depending on context, stress may increase avoidance of guidance devices or, conversely, lead to maladaptive approaches, making welfare an important behavioral factor that should be evaluated using field trials and long-term monitoring [

79,

86]. Water quality, physiological stress responses, and environmental conditions more broadly all influence movement around intakes. External factors that affect appetite and neuroendocrine signaling under stress or during fasting and refeeding can modify activity levels and responsiveness to cues, including those used in guidance systems, revealing a gap in models that link physiological state to device performance under realistic conditions [

87]. Welfare-focused resources further show that species-specific risk profiles shape responses to captivity and handling, emphasizing the importance of integrating welfare into design assessments: structures that minimize stress are more likely to elicit predictable behavior and greater acceptance of safe bypass routes [

86].

4.5. Governance, Knowledge Sharing, and Regional Inventories

Bridging the gap between behavioral research and practical design also requires better collaboration and knowledge exchange. Effective coordination among scientists, engineers, fishers, and managers, supported by industry-led training, peer learning, and systematic knowledge sharing, has been identified as critical for improving non-target avoidance and operational efficiency [

88,

89]. Broader research on design education and knowledge transfer likewise suggests that closing the gap between theoretical understanding and on-the-ground implementation is essential for success [

4]. Turning behavioral insights into concrete design and operational guidance will depend on robust knowledge-management frameworks that make information accessible and actionable [

90,

91]. When stakeholders are involved in developing tools and solutions, innovations become more credible and easier to implement. This co-production of tools, combined with explicit attention to stakeholder perspectives, helps ensure that management plans move beyond “paper parks” and fosters the trust needed for practitioners to adopt and maintain new behavioral guidance strategies in real-world settings [

89,

92].

Regional knowledge inventories are another promising but underdeveloped resource. Systematically compiling and mapping information on species, habitats, and hydraulic conditions would support the development of guidance solutions that are both locally adapted and more widely transferable. Such inventories are currently limited, but they could greatly improve our understanding of how different factors shape behavior and enable the design of guidance systems that can be adapted across regions and contexts [

2,

83].

4.6. Adaptive and AI-Supported Guidance Systems

Looking ahead, several research directions appear especially important for addressing these gaps. First, integrated systems that combine multiple stimuli, such as light and sound in combination with physical structures, are gaining attention as ways to create richer, harder-to-ignore sensory environments. Second, there is growing emphasis on species-specific solutions. Rather than relying on one-size-fits-all strategies, new work is focusing on barriers tailored to the sensory capacities, life cycles, and ecological roles of each target species, which should make solutions more effective and more relevant to local management needs. Third, cognitive and behavioral modeling is becoming an increasingly valuable tool. By using advanced models that capture how fish process information about flow, light, sound, and other cues over different timescales, researchers can better predict movement and navigation and thereby support more robust, evidence-based designs.

Finally, the diversity of fish species, life stages, and environmental contexts points toward adaptive and holistic guidance systems as a necessary goal. In practice, the most effective non-physical barriers are likely to be those that combine multiple stimuli and adjust in real time to the species present and the prevailing conditions. AI-based algorithms can integrate image and numerical data on species identity, position, and behavior to support such adaptability; recent advances in machine learning already allow automatic detection and classification of species-specific sounds, making it easier to analyze large datasets and overlapping acoustic niches [

93,

94]. Although comprehensive, validated sound libraries at the species level remain limited, AI clearly offers a pathway to more efficient and accurate biodiversity monitoring and a stronger evidence base for conservation decisions [

94,

95]. These multimodal data streams can then drive models for barrier operations to optimize effectiveness across scenarios, while machine-learning–based analytical frameworks can also evaluate fish welfare, enhancing the economic sustainability of scaling such barrier solutions.

5. Conclusions

Non-physical and physical barriers are increasingly central tools for managing fish movement around hydraulic infrastructure and for reconciling water-security objectives with biodiversity conservation. When carefully designed, these systems can protect native species, limit the spread of invasive taxa, and reduce turbine-related mortality, while still maintaining connectivity where fish passage is required.

This review shows that non-physical barriers hold considerable promise as flexible, low-impact guidance tools, but their effectiveness is strongly dependent on species, life stage, and local context. Light-based systems are constrained by water clarity and ambient illumination; acoustic barriers must account for background noise, sound propagation, and species-specific hearing sensitivities; bubble curtains are influenced by flow conditions and plume geometry; and chemical cues demand careful control of concentration gradients and explicit consideration of welfare implications. Electric barriers can be highly effective deterrents, but they raise particular concerns regarding stress, injury, and mortality among fish that attempt to cross them, highlighting the need for conservative settings and systematic welfare assessments.

Design decisions are critical in shaping outcomes. Effective systems must be tailored to site-specific hydraulics and to the sensory ecology of both target and non-target species, ideally incorporating hydrodynamic features such as low-velocity corridors, refuge zones, and attraction flows that minimize energetic costs and stress. At the same time, the ecological consequences of barriers extend beyond individual species to whole communities and river-network connectivity. Poorly configured systems may fragment habitats and alter community structure, even if they successfully exclude invaders. Hybrid approaches that combine physical and non-physical elements therefore offer a promising pathway to balance exclusion, guidance, and passage across diverse taxa.

Looking ahead, three priorities emerge. First, there is an urgent need for standardized performance metrics and consistent reporting of device characteristics and environmental conditions, to allow robust comparisons among studies and to support evidence-based design guidelines. Second, long-term, multi-species monitoring is required to capture behavioral habituation and life-stage-specific responses under realistic operating regimes. Third, the integration of modern technologies, high-resolution telemetry, imaging and acoustic monitoring, and AI-based analytics for species detection, behavior tracking, and welfare assessment, can enable adaptive, real-time control of guidance systems and substantially strengthen the evidence base for management decisions.

By bringing together insights from behavioral ecology, hydraulics, and data-driven monitoring, fish-guidance barriers can move from ad hoc installations to rigorously engineered, site-specific systems that contribute meaningfully to both water security and the conservation of freshwater biodiversity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.O.N, E.M.L.; methodology, E.M.L.; investigation, N.O.N., E.M.L.; data curation, E.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.L., N.O.N.; writing—review and editing, E.M.L., N.O.N.; Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Horizon Europe project Revolutionary Refurbishment for an Efficient and Eco-Friendly Hydropower—REVHYDRO, Grant Agreement ID 101172857, Funded under Climate, Energy and Mobility. Funding Scheme: HORIZON-RIA—HORIZON Research and Innovation Actions. Also, the authors acknowledge the support provided by Romanian Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitalization, project number 42N/2023: PN23140201 and PN23140101.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used OpenAI ChatGPT in order to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

References

- Beck, C.; Albayrak, I.; Meister, J.; Peter, A.; Selz, O.M.; Leuch, C.; Vetsch, D.F.; Boes, R.M. Swimming Behavior of Downstream Moving Fish at Innovative Curved-Bar Rack Bypass Systems for Fish Protection at Water Intakes. Water 2020, 12, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Lucas, M.C.; Castro-Santos, T.; Katopodis, C.; Baumgartner, L.J.; Thiem, J.D.; Aarestrup, K.; Pompeu, P.d.S.; O’Brien, G.C.; Braun, D.C.; et al. The Future of Fish Passage Science, Engineering, and Practice. Fish Fish. 2017, 19, 340–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Guo, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L. Research Progress on Fish Barrier Measures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of PIANC Smart Rivers 2022, Singapore, 2023; pp. 1195–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Maddahi, M.; Hagenbüchli, R.; Mendez, R.; Zaugg, C.; Boes, R.M.; Albayrak, I. Field Investigation of Hydraulics and Fish Guidance Efficiency of a Horizontal Bar Rack-Bypass System. Water 2022, 14, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noatch, M.R.; Suski, C.D. Non-physical barriers to deter fish movements. Environ. Rev. 2012, 20, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.; Amorim, M.C.P.; Fonseca, P.J.; Teixeira, A.; Natário, S.; Carrola, J.; Varandas, S.; Torres Pereira, L.; Cortes, R.M.V. Acoustic barriers as an acoustic deterrent for native potamodromous migratory fish species. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 95, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchy, K.A.; Cupp, A.R.; Amberg, J.J.; Vetter, B.J.; Fredricks, K.T.; Gaikowski, M.P.; Mensinger, A.F. Potential implications of acoustic stimuli as a non-physical barrier to silver carp and bighead carp. Fish. Manage. Ecol. 2017, 24, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bie, J.; Peirson, G.; Kemp, P.S. Evaluation of horizontally and vertically aligned bar racks for guiding downstream moving juvenile chub (Squalius cephalus) and barbel (Barbus barbus). Ecol. Eng. 2021, 170, 106327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tétard, S.; Maire, A.; Lemaire, M.; De Oliveira, E.; Martin, P.; Courret, D. Behaviour of Atlantic salmon smolts approaching a bypass under light and dark conditions: Importance of fish development. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 131, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.D.; Glover, D.C.; Finney, S.T.; Rogers, P.B.; Stewart, J.G.; Simmonds, R.L. Fish distribution, abundance, and behavioral interactions within a large electric dispersal barrier designed to prevent Asian carp movement. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2016, 73, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammang, M.K.; Weber, M.J.; Thul, M.D. Laboratory Evaluation of a Bioacoustic Bubble Strobe Light Barrier for Reducing Walleye Escapement. N. Am. J. Fish. Manage 2014, 34, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahel, F.J.; McLaughlin, R.L. Selective fragmentation and the management of fish movement across anthropogenic barriers. Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 2066–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemasson, B.H.; Haefner, J.W.; Bowen, M.D. Schooling Increases Risk Exposure for Fish Navigating Past Artificial Barriers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, E.C.; Charles, C.; Watkinson, D.A.; Kovachik, C.; Leroux, D.R.; Hansen, H.; Pegg, M.A. Analysing Habitat Connectivity and Home Ranges of Bigmouth Buffalo and Channel Catfish Using a Large-Scale Acoustic Receiver Network. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenritter, M.E.; Pescitelli, S.M.; Whitten, A.L.; Casper, A.F. Implications of an invasive fish barrier for the long-term recovery of native fish assemblages in a previously degraded northeastern Illinois River system. River Res. Appl. 2019, 35, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.J.; Cocherell, D.E.; Cooke, S.J.; Patrick, P.H.; Sills, M.; Fangue, N.A. Behavioural guidance of Chinook salmon smolts: The variable effects of LED spectral wavelength and strobing frequency. Conserv. Physiol. 2018, 6, coy032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layhee, M.J.; Sepulveda, A.J.; Shaw, A.; Smuckall, M.; Kapperman, K.; Reyes, A. Effects of electric barrier on passage and physical condition of juvenile and adult rainbow trout. J. Fish Wildl. Manag. 2016, 7, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, A.T.; White, P.R.; Wright, R.M.; Leighton, T.G.; Kemp, P.S. Response of Seaward-Migrating European Eel (Anguilla Anguilla) to an Infrasound Deterrent. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 127, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzonek, P.A.; Edwards, P.; Hasler, C.T.; Suski, C.D.; Boonstra, R.; Mandrak, N.E. Deterring the Movement of an Invasive Fish: Individual Variation in Common Carp Responses to Acoustic and Stroboscopic Stimuli. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2021, 151, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.; Cortes, R.; Teixeira, A. Acoustic and Light Selective Behavioral Guidance Systems for Freshwater Fish. Water 2021, 13, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Rengifo, M.; Mazurais, D.; Bégout, M.L. Response to Visual and Mechano-Acoustic Predator Cues Is Robust to Ocean Warming and Acidification and Is Highly Variable in European Sea Bass. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1108968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, J.; Romanczuk, P.; Klenz, H.; Klamser, P.; Arias-Rodríguez, L.; Krause, J.; Bierbach, D. Acoustic and Visual Stimuli Combined Promote Stronger Responses to Aerial Predation in Fish. Behav. Ecol. 2021, 32, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio-Torres, M.E.; Crowl, T.A.; Sabat, A.M. Effect of Multimodal Cues From a Predatory Fish on Refuge Use and Foraging on an Amphidromous Shrimp. Peerj 2021, 9, e11011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.T.; Juliane De Abreu Campos Machado, L.; Valença-Silva, G.; Barcellos, L.J.G.; Barreto, R.E. Ventilation Responses to Predator Odors and Conspecific Chemical Alarm Cues in the Frillfin Goby. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 179, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ålund, M.; Harper, B.; Kjærnested, S.; Ohl, J.E.; Phillips, J.G.; Sattler, J.; Thompson, J.J.; Varg, J.E.; Wargenau, S.; Boughman, J.W.; et al. Sensory Environment Affects Icelandic Threespine Stickleback’s Anti-Predator Escape Behaviour. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2022, 289, 20220044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenihan, E.S.; McCarthy, T.K.; Lawton, C. Effectiveness of a Strobing Light System for Deflecting Downstream Migrating European Silver Eels (Anguilla anguilla). Fish. Manage. Ecol. 2025, n/a, e12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvidge, C.K.; Ford, M.I.; Pratt, T.C.; Smokorowski, K.E.; Sills, M.; Patrick, P.H.; Cooke, S.J. Behavioural guidance of yellow-stage American eel Anguilla rostrata with a light-emitting diode device. Endanger. species res. 2018, 35, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.; Mouton, A.M.; Stevens, M.; Van den Neucker, T.; Coeck, J. Mortality of European eel after downstream migration through two types of pumping stations. Fish. Manage. Ecol. 2014, 21, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keep, J.K.; Watson, J.R.; Cramp, R.L.; Jones, M.J.; Gordos, M.A.; Ward, P.J.; Franklin, C.E. Low light intensities increase avoidance behaviour of diurnal fish species: Implications for use of road culverts by fish. J. Fish Biol. 2021, 98, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, C.; Jechow, A.; Campbell, J.A.; Zielinska-Dabkowska, K.M.; Hölker, F. Light pollution from illuminated bridges as a potential barrier for migrating fish–Linking measurements with a proposal for a conceptual model. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2024, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Dai, H.; Shi, X.; Deng, Z.D.; Mao, J.; Zhao, S.; Luo, J.; Tan, J. An experimental study on fish attraction using a fish barge model. Fish. Res. 2019, 210, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.A.; Désormeaux, I.S.; Brown, G.E. Disturbance Cues as a Source of Risk Assessment Information Under Natural Conditions. Freshwat. Biol. 2020, 65, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putland, R.L.; Mensinger, A.F. Acoustic deterrents to manage fish populations. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2019, 29, 789–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, G.; Yang, J.; Xu, J.; Ke, S.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Shi, X.; Lin, C. Avoidance behavior of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) shoals to low-frequency sound stimulation. Aquat. Sci. 2024, 87, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, B.J.; Mensinger, A.F. Broadband sound can induce jumping behavior in invasive silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix). Proc. meet. acoust. 2016, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Liu, Y.; Shen, X.; Wu, Y.; Tian, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, X.; Liu, G. Spatial avoidance of tu-fish Schizopygopsis younghusbandi for different sounds may inform behavioural deterrence strategies. Fish. Manage. Ecol. 2020, 27, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamboldt, J.J.; Murchy, K.A.; Stanton, J.C.; Blodgett, K.D.; Brey, M.K. Evaluation of an acoustic fish deterrent system in shallow water application at the Emiquon Preserve, Lewistown, IL. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Huang, X.; Xie, L.; Liu, G.; Hou, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, X. Experimentally determined effectiveness of different electric barrier arrangements on the behavioural deterrent of silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 271, 106172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasiewicz, P.; Wiśniewolski, W.; Mokwa, M.; Zioła, S.; Prus, P.; Godlewska, M. A low-voltage electric fish guidance system-NEPTUN. Fish. Res. 2016, 181, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldenhauer-Roth, A.; Selz, O.M.; Albayrak, I.; Boes, R.M. Behavioural response of chub, barbel and brown trout to pulsed direct current electric fields. J. Ecohydraulics 2024, 10, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajer, P.G.; Hundt, P.J.; Kukulski, E.; Kocian, M. Field test of an electric deterrence and guidance system during a natural spawning migration of invasive common carp. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.S.; Snow, B.; Bruning, T.; Jubar, A. A seasonal electric barrier blocks invasive adult sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) and reduces production of larvae. J. Great Lakes Res. 2021, 47, S310–S319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoot, L.J.; Gibson, D.P.; Cooke, S.J.; Power, M. Assessing the potential for using low-frequency electric deterrent barriers to reduce lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) entrainment. Hydrobiologia 2018, 813, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; de Bie, J.; Sharkh, S.M.; Kemp, P.S. Behavioural response of downstream migrating European eel (Anguilla anguilla) to electric fields under static and flowing water conditions. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 172, 106397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leander, J.; Hellström, G.; Nordin, J.; Jonsson, M.; Klaminder, J. Guiding downstream migrating Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and brown trout (Salmo trutta) of different life stages in a large river using bubbles. River Res. Appl. 2024, 40, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cîrciumaru, G.; Chihaia, R.-A.; Voina, A.; Gogoașe Nistoran, D.-E.; Simionescu, Ș.-M.; El-Leathey, L.-A.; Mândrea, L. Experimental Analysis of a Fish Guidance System for a River Water Intake. Water 2022, 14, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.E.; Suski, C.D. Coupling carbon dioxide gas within a bubble curtain enhances its effectiveness to deter fish. Biol. Invasions 2025, 27, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leander, J.; Klaminder, J.; Hellström, G.; Jonsson, M. Bubble barriers to guide downstream migrating Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): An evaluation using acoustic telemetry. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 160, 106141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, V.; Bergman, E.; Aldvén, D.; Bowes, R.E.; Calles, O.; Nyquist, N.; Nyqvist, D.; Rowinski, P.; Greenberg, L. Downstream guidance performance of a bubble curtain and a net barrier for the European eel, Anguilla anguilla, in an experimental flume. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 215, 107599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suski, C.D. Development of Carbon Dioxide Barriers to Deter Invasive Fishes: Insights and Lessons Learned From Bigheaded Carp. Fishes 2020, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolper, T.J.; Smith, D.L.; Jackson, P.R.; Cupp, A.R. Performance of a Carbon Dioxide Injection System at a Navigation Lock to Control the Spread of Aquatic Invasive Species. J. Environ. Eng. 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politano, M.; Cupp, A.R.; Smith, D.H.; Schemmel, A.; Jackson, P.R.; Zuercher, J. Evaluation of a Carbon Dioxide Fish Barrier With OpenFOAM. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 1312, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, C.T.; Woodley, C.M.; Schneider, E.V.C.; Hixson, B.K.; Fowler, C.J.; Midway, S.R.; Suski, C.D.; Smith, D.L. Avoidance of Carbon Dioxide in Flowing Water by Bighead Carp. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 76, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, H.V.; van Keeken, O.A.; Kleissen, F.; Foekema, E.M. Wastewater plumes can act as non-physical barriers for migrating silver eel. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yan, Z.; Lin, A.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Yin, X.; Li, W.; Li, K. Novel Epidermal Oxysterols Function as Alarm Substances in Zebrafish. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensch, E.L.; Dissanayake, A.A.; Nair, M.G.; Wagner, C.M. Sea Lamprey Alarm Cue Comprises Water- And Chloroform- Soluble Components. J. Chem. Ecol. 2022, 48, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]