Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

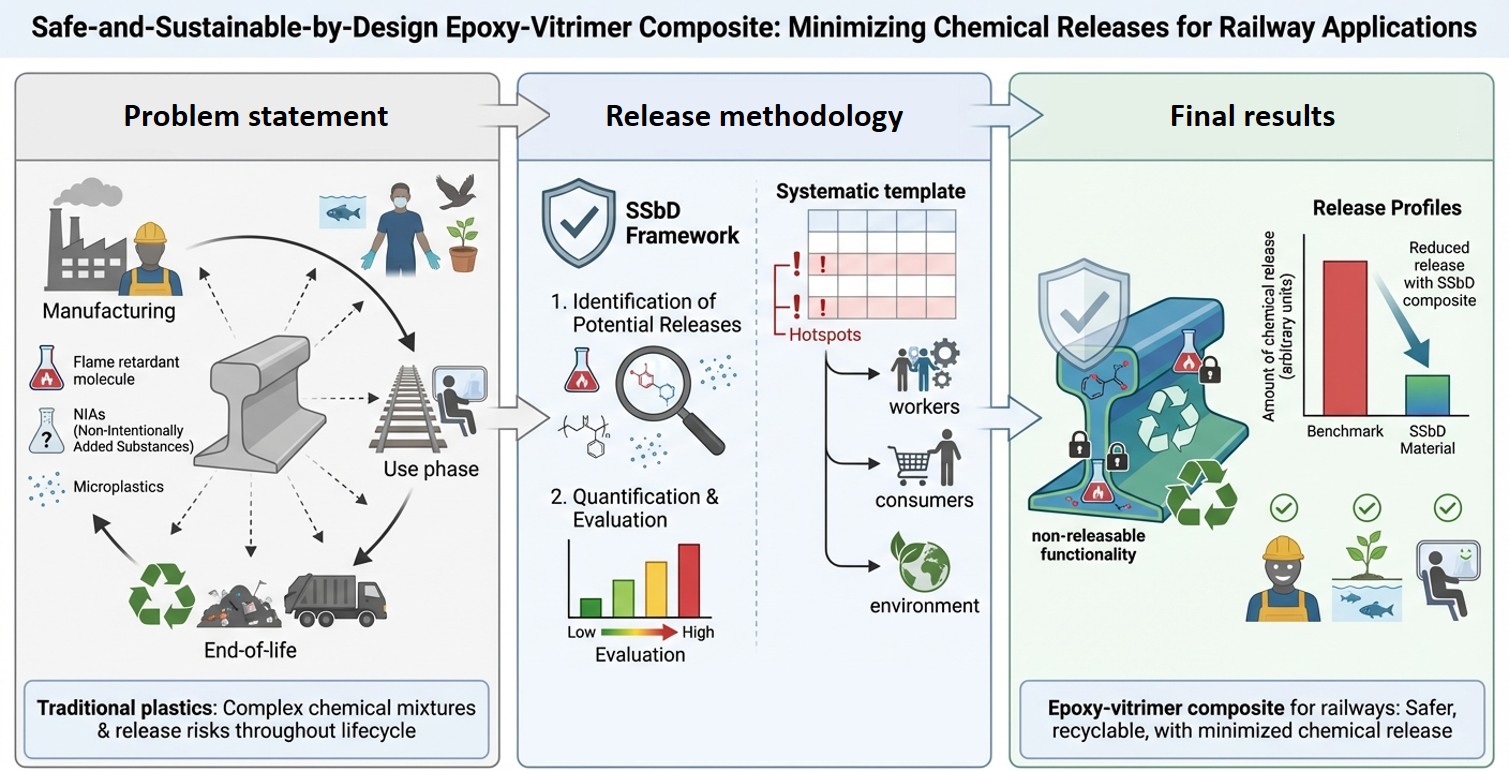

The development of new chemicals and materials that are inherently safe and sustainable throughout their entire life cycle has become a critical objective in the context of the green transition. This challenge is especially significant for plastics, which often contain complex mixtures of chemicals that may be released during various stages of their life cycle, from manufacturing to use and end-of-life management. Such releases can pose risks to human health and the environment. Within this context, the Safe and Sustainable by Design (SSbD) framework was followed to support the design of an innovative epoxy-vitrimer composite that integrates non-releasable fire-retardant functionalities, aiming to produce a safer, recyclable materials suitable for railway applications. This study presents the identification and quantification of potential releases as part of Steps 2 and 3 of the SSbD framework. A dedicated methodology was established to evaluate the potential release of materials such as flame retardants, non-intentionally added substances, and microplastics throughout the product’s life cycle. A systematic template was developed to identify release hotspots potentially affecting workers, consumers, and environmental species and organisms. Based on these findings, experimental simulations were conducted to compare release profiles between a benchmark and the SSbD alternative.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

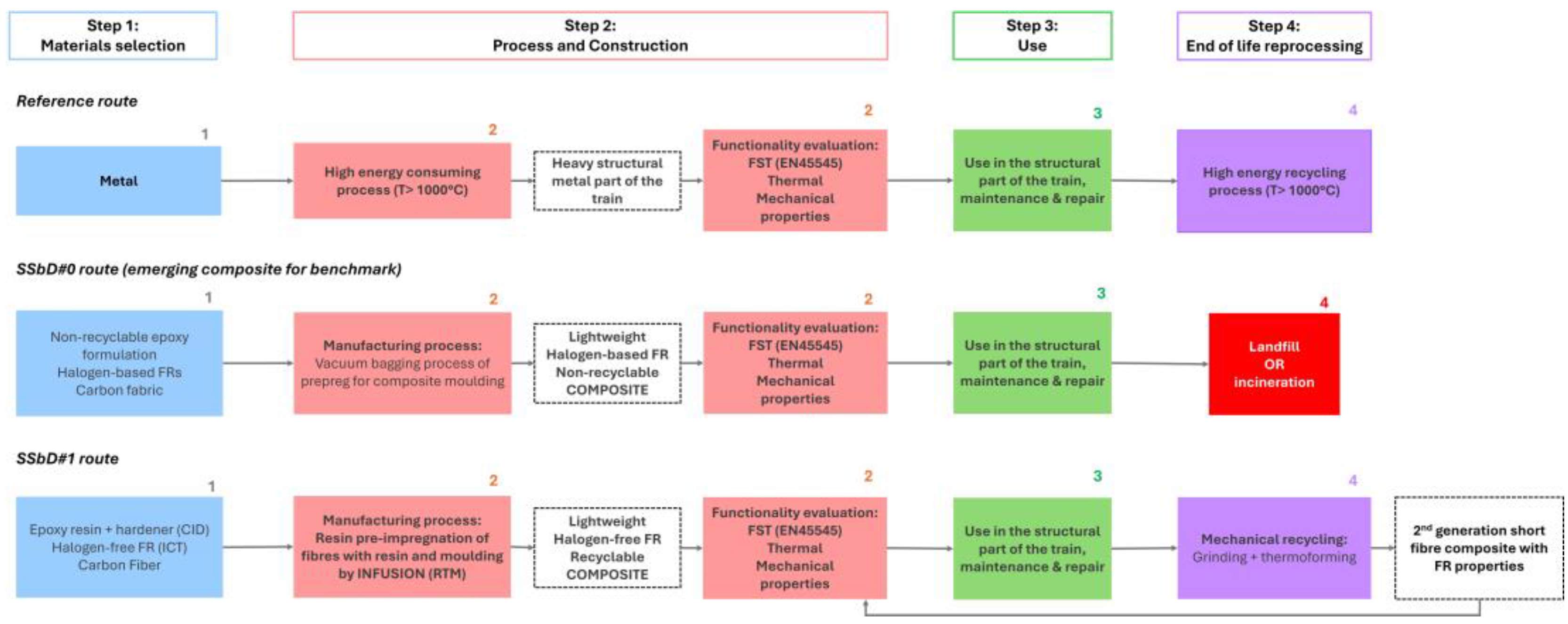

2.1. Case Study Description

2.2. Release Assessment Methodology

2.3. Release Hotspots Identification and Quantification

2.4. Release Quantification at Identified Hotspots

2.4.1. Outdoor Aging and Hard Abrasion Test

2.4.2. Micro- and Nanoplastic Spot-Check

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Release Quantification at Identified Hotspots

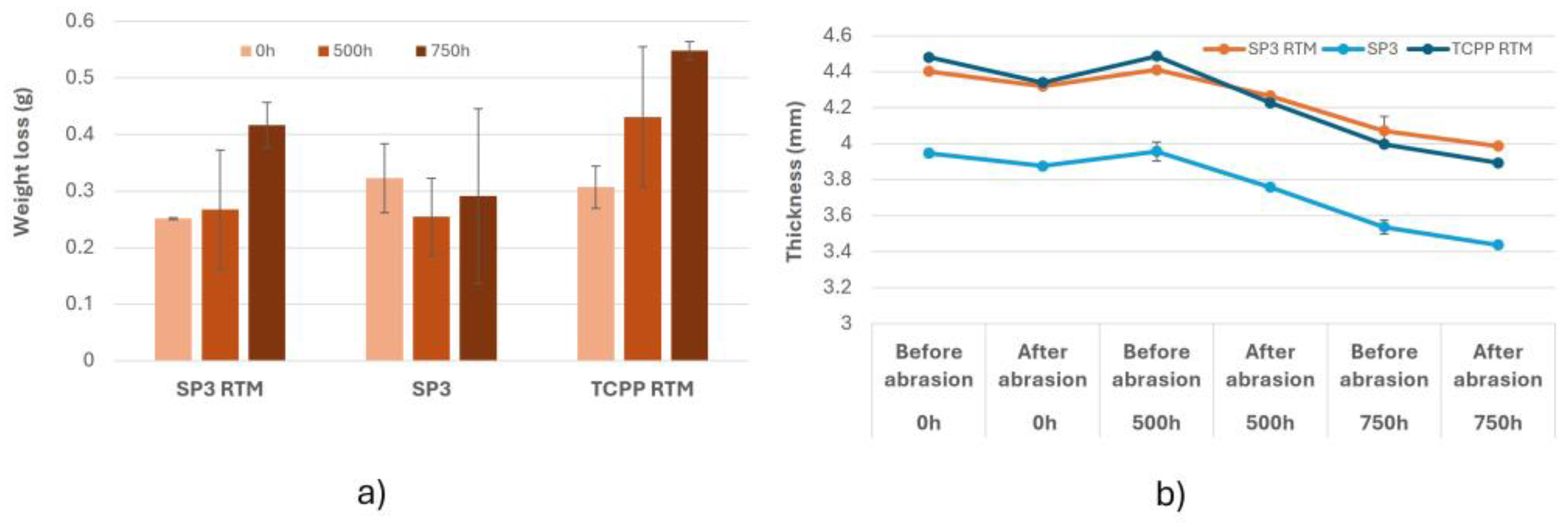

3.1.1. Outdoor Aging and Hard Abrasion

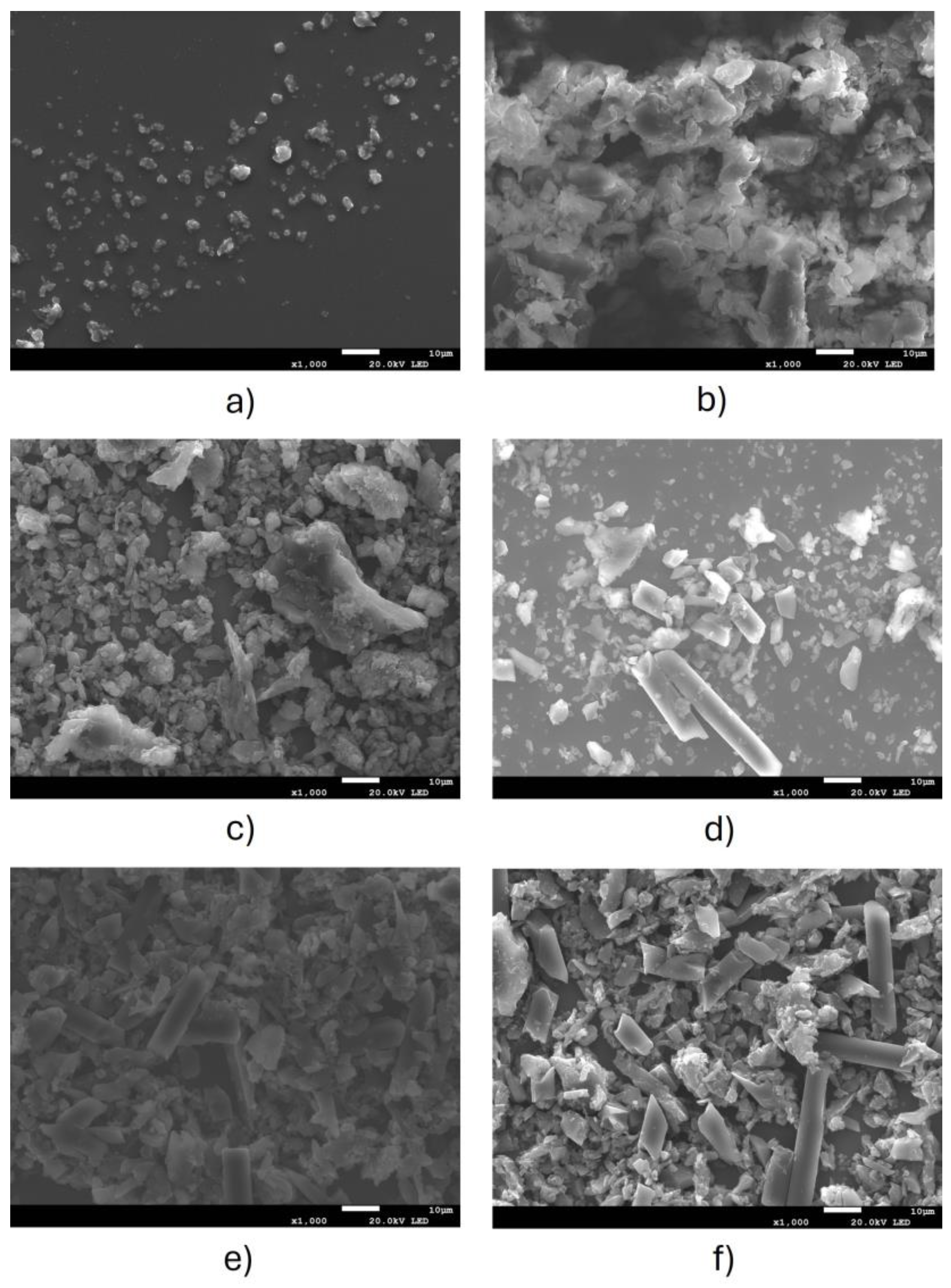

3.1.2. Outdoor Aging and Micro- and Nanoplastic Quantification

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Analytical ultracentrifugation |

| DOC | Dissolved Organic Carbon |

| EC | European Commission |

| ECHA | European Chemicals Agency |

| FR | Flame retardants |

| IAS | Intentionally added substances |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma- Mass Spectrometry |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre |

| MNPs | Micro- and nanoplastics |

| NIAS | Non-intentionally added substances |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SSbD | Safe and Sustainable by Design |

| SVHC | Substances of Very High Concern |

| TCPP | Tris(1-chloro-2-propyl) phosphate |

References

- C. Caldeira et al., ‘Safe and Sustainable by Design chemicals and materials - Framework for the definition of criteria and evaluation procedure for chemicals and materials’, EUR 31100 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. ISBN 978-92-76-53264-4, 2022.

- C. Caldeira et al., ‘Safe and Sustainable by Design chemicals and materials - Review of safety and sustainability dimensions, aspects, methods, indicators, and tools’, p. EUR 30991 EN, ISBN 978-92-76-47560-6, JRC127109, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Caldeira et al., Safe and sustainable by design chemicals and materials – Application of the SSbD framework to case studies. Publications Office of the European Union, 2023. doi: 10.2760/329423. [CrossRef]

- E. Abbate et al., ‘Safe and Sustainable by Design chemicals and materials - Methodological Guidance’, Eur. Comm. Jt. Res. Cent., 2024, doi: https://data.europa. eu/doi/10.2760/28450. [CrossRef]

- I. R. Garmendia Aguirre Kirsten; Rauscher, Hubert, ‘Safe and Sustainable by Design: Driving Innovation Toward Safer and More Sustainable Chemicals, Materials, Processes and Products’, Sustain. Circ. NOW, vol. 02, no. continuous publication, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Apel et al., ‘Safe-and-sustainable-by-design roadmap: identifying research, competencies, and knowledge sharing needs’, RSC Sustain., 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Brander et al., ‘The time for ambitious action is now: Science-based recommendations for plastic chemicals to inform an effective global plastic treaty’, Sci. Total Environ., vol. 949, p. 174881, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Geueke et al., ‘Evidence for widespread human exposure to food contact chemicals’, J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol., vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 330–341, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Hahladakis, C. A. Velis, R. Weber, E. Iacovidou, and P. Purnell, ‘An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling.’, J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 344, pp. 179–199, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Monclús et al., ‘Mapping the chemical complexity of plastics’, Nature, vol. 643, no. 8071, pp. 349–355, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Thompson, W. Courtene-Jones, J. Boucher, S. Pahl, K. Raubenheimer, and A. A. Koelmans, ‘Twenty years of microplastic pollution research—what have we learned?’, Science, vol. 386, no. 6720, p. eadl2746, 2024. [CrossRef]

- European Commission, COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) 2023/2055 of 25 September 2023 amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards synthetic polymer microparticles, 2023.

- L. G. Soeteman-Hernandez et al., ‘Safe, Sustainable, and Recyclable by Design (SSRbD): A Qualitative Integrated Approach Applied to Polymeric Materials Early in the Innovation Process’, Sustainability & Circularity NOW, vol. 02, no. a25547325, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Artous, S. et al., ‘Safe, sustainable and recyclable by design (SSRbD): A quantitative integrated approach through a scoring system applied to polymeric materials’, vol. Sustainability and Circularity NOW, submitted.

- V. Berner, A. Huegun, L. Hammer, A. M. Cristadoro, and C.-C. Höhne, ‘Thermal and flame retardant properties of recyclable disulfide based epoxy vitrimers’, Polym. Degrad. Stab., vol. 233, p. 111145, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. M. Barrett, D. E. Meyer, R. L. Smith, S. Takkellapati, and M. A. Gonzalez, ‘Review of generic scenario environmental release and occupational exposure models used in chemical risk assessment.’, J. Occup. Environ. Hyg., vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 545–562, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. G. Jessop and A. R. MacDonald, ‘The need for hotspot-driven research’, Green Chem, vol. 25, no. 23, pp. 9457–9462, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Pourzahedi et al., ‘Life cycle considerations of nano-enabled agrochemicals: Are today’s tools up to the task?’, Environ. Sci. Nano, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 1057–1069, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Jiang and B. Nowack, ‘Reconciling plastic release: Comprehensive modeling of macro- and microplastic flows to the environment’, Environ. Pollut., vol. 383, p. 126800, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Lambert and M. Wagner, ‘Formation of microscopic particles during the degradation of different polymers.’, Chemosphere, vol. 161, pp. 510–517, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, Y. Song, and Y. Cai, ‘Focus topics on microplastics in soil: Analytical methods, occurrence, transport, and ecological risks.’, Environ. Pollut. Barking Essex 1987, vol. 257, p. 113570, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Ben Jeddi et al., ‘Development of a nano-specific safe-by-design module to identify risk management strategies’, Ann. Work Expo. Health, vol. 69, no. 3, pp. 310–322, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- V. Cazzagon et al., ‘The SAbyNA platform: a guidance tool to support industry in the implementation of safe- and sustainable-by-design concepts for nanomaterials, processes and nano-enabled products’, Environ. Sci.: Nano, vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 4008–4025, 2025. [CrossRef]

- K.-R. Chatzipanagiotou, F. Petrakli, J. Steck, C. Philippot, S. Artous, and E. P. Koumoulos, ‘Towards safe and sustainable by design nanomaterials: Risk and sustainability assessment on two nanomaterial case studies at early stages of development’, Sustain. Futur., vol. 9, p. 100511, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. Lomonaco et al., ‘Release of harmful volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from photo-degraded plastic debris: A neglected source of environmental pollution.’, J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 394, p. 122596, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Ren, Y. Han, H. Zhao, Z. Zhang, T.-H. Tsui, and Q. Wang, ‘Elucidating the characteristic of leachates released from microplastics under different aging conditions: Perspectives of dissolved organic carbon fingerprints and nano-plastics.’, Water Res., vol. 233, p. 119786, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Sun, H. Zheng, H. Xiang, J. Fan, and H. Jiang, ‘The surface degradation and release of microplastics from plastic films studied by UV radiation and mechanical abrasion.’, Sci. Total Environ., p. 156369, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), ‘Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment - Chapter R.12: Use description’, 2015, [Online]. Available: ECHA-15-G-11-EN.

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), Guidance on information requirements and chemical safety assessment. Chapter R. 14: Occupational exposure assessment. 2016.

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), ‘Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment Chapter R.15: Consumer exposure assessment’, 2016.

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), ‘Guidance on information requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment - Chapter R.16: Environmental exposure assessment’, ECHA-16-G-03-EN, vol. 978-92-9247-775–2, 2016.

- W. Wohlleben, N. Bossa, D. M. Mitrano, and K. Scott, ‘Everything falls apart: How solids degrade and release nanomaterials, composite fragments, and microplastics’, NanoImpact, vol. 34, p. 100510, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Rai, C. Sonne, R. J. C. Brown, S. A. Younis, and K.-H. Kim, ‘Adsorption of environmental contaminants on micro- and nano-scale plastic polymers and the influence of weathering processes on their adsorptive attributes’, J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 427, p. 127903, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Luo, C. Liu, D. He, J. Sun, J. Li, and X. Pan, ‘Effects of aging on environmental behavior of plastic additives: Migration, leaching, and ecotoxicity’, Sci. Total Environ., vol. 849, p. 157951, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Luo, Y. Li, Y. Zhao, Y. Xiang, D. He, and X. Pan, ‘Effects of accelerated aging on characteristics, leaching, and toxicity of commercial lead chromate pigmented microplastics’, Environ. Pollut., vol. 257, p. 113475, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Pfohl et al., ‘Environmental degradation and fragmentation of microplastics: dependence on polymer type, humidity, UV dose and temperature’, Microplastics Nanoplastics, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 7, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Cheng, H. Luo, Y. Hu, and S. Tao, ‘Release kinetics as a key linkage between the occurrence of flame retardants in microplastics and their risk to the environment and ecosystem: A critical review’, Water Res., vol. 185, p. 116253, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Menger et al., ‘Screening the release of chemicals and microplastic particles from diverse plastic consumer products into water under accelerated UV weathering conditions’, J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 477, p. 135256, Sept. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Jarosz et al., ‘Abiotic weathering of plastic: Experimental contributions towards understanding the formation of microplastics and other plastic related particulate pollutants’, Sci. Total Environ., vol. 917, p. 170533, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Bridson et al., ‘Leaching and transformation of chemical additives from weathered plastic deployed in the marine environment’, Mar. Pollut. Bull., vol. 198, p. 115810, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Das, A. D. La Rosa, S. Goutianos, and S. Grammatikos, ‘Effect of accelerated weathering on the performance of natural fibre reinforced recyclable polymer composites and comparison with conventional composites’, Compos. Part C Open Access, vol. 12, p. 100378, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Amirnuddin et al., ‘Compressive behaviour of tin slag polymer concrete confined with fibre reinforced polymer composites exposed to tropical weathering and aggressive conditions’, Mater. Today Proc., Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Pott and K. H. Friedrichs, ‘Tumoren der Ratte nach i.p.-Injektion faserförmiger Stäube’, Naturwissenschaften, vol. 59, no. 7, pp. 318–318, July 1972. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Stanton and C. Wrench, ‘Mechanisms of mesothelioma induction with asbestos and fibrous glass.’, J. Natl. Cancer Inst., vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 797–821, Mar. 1972.

- World Health Organisation (WHO), ‘Determination of airborne fibre number concentrations : a recommended method, by phase-contrast optical microscopy (membrane filter method)’, 1997, doi: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/41904.

- V. I. Dumit et al., ‘Meta-Analysis of Integrated Proteomic and Transcriptomic Data Discerns Structure–Activity Relationship of Carbon Materials with Different Morphologies’, Adv. Sci., vol. 11, no. 9, p. 2306268, 2024. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO), ISO 4892-3:2024. Plastics- Methods of exposure to laboratory light sources. Part 3: Fluorescent UV lamps, 2024.

- W. Wohlleben et al., ‘NanoRelease: Pilot interlaboratory comparison of a weathering protocol applied to resilient and labile polymers with and without embedded carbon nanotubes’, Carbon, vol. 113, pp. 346–360, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Pfohl et al., ‘Environmental Degradation of Microplastics: How to Measure Fragmentation Rates to Secondary Micro- and Nanoplastic Fragments and Dissociation into Dissolved Organics’, Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 56, no. 16, pp. 11323–11334, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

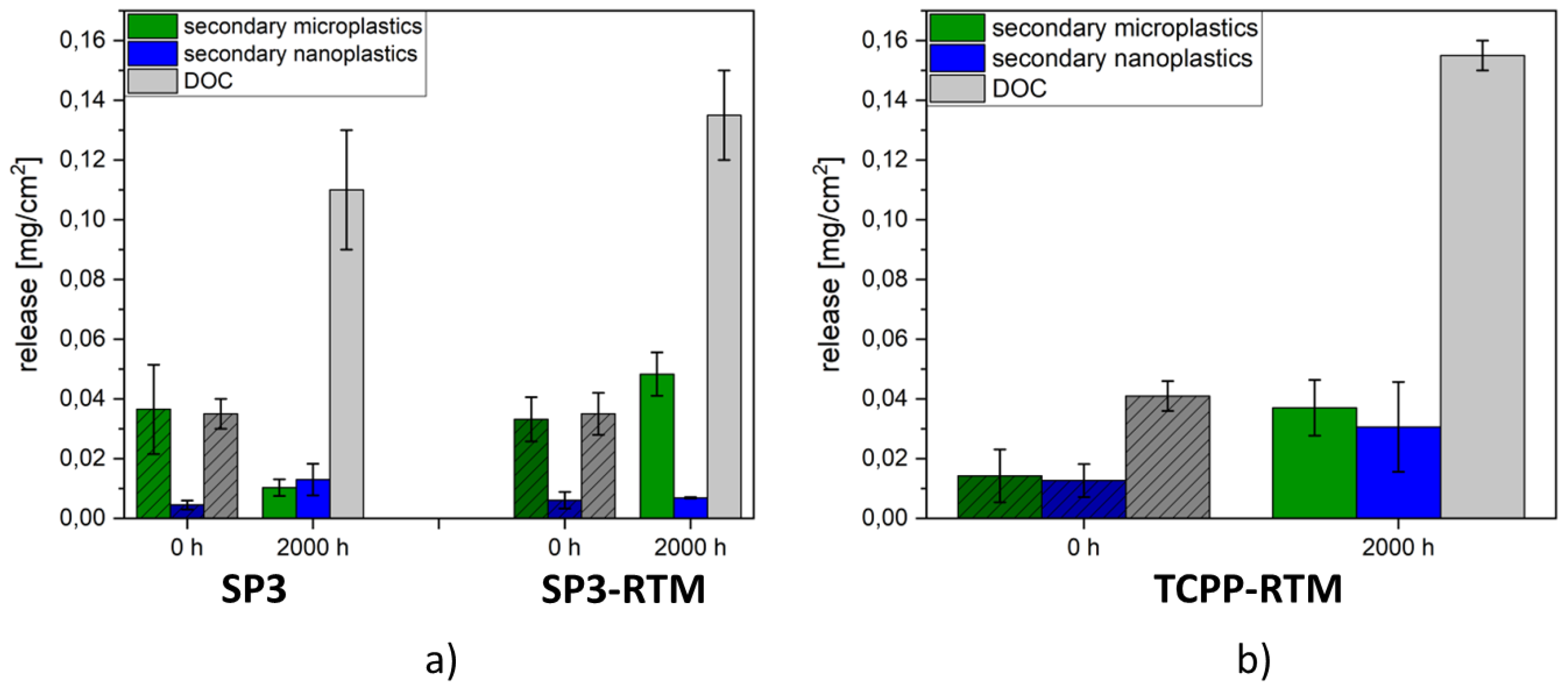

| Life cycle stage | Activity | Potential hotspot of release | Potential receptors of release / exposure | Substance of interest | ER/EC | Experimental test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 and Step 2 – Material design (Formulation and manu-facturing) – FR resin formulation | Handling/ cutting of fibres | YES- dry solid carbon fibres, high energy level of the process, manual activity, 60’of duration | Workers | Micro and nanofibres | Inhalation, dermal | NA |

| Step 3 - Use | Use as exterior structural part of the train | YES- potential release during aging and abrasion | Environment | Powder of the composite, micro and nano fibres, MNPs | Soil, water | Outdoor aging and hard abrasion |

| Step 4- Mechanical recycling | Grinding | YES- dry micro composite particles/powder and/or carbon fibres, high energy level of the process, manual activity | Workers | Powder of the composite, micro and nano fibres, MNPs | Inhalation, dermal | NA |

| Sample | S (% w/w) – 1x1 cm2 sample (Mean ± SD) | S (% w/w) related to the total abraded sample volume (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| SP3RTM | 1.73 ± 0.06 | 51.92 ± 1.77 |

| SP3 | 6.30 ± 0.11 | 188.92 ± 3.22 |

| TCPP RTM | 1.53 ±0.01 | 46.05 ± 0.26 |

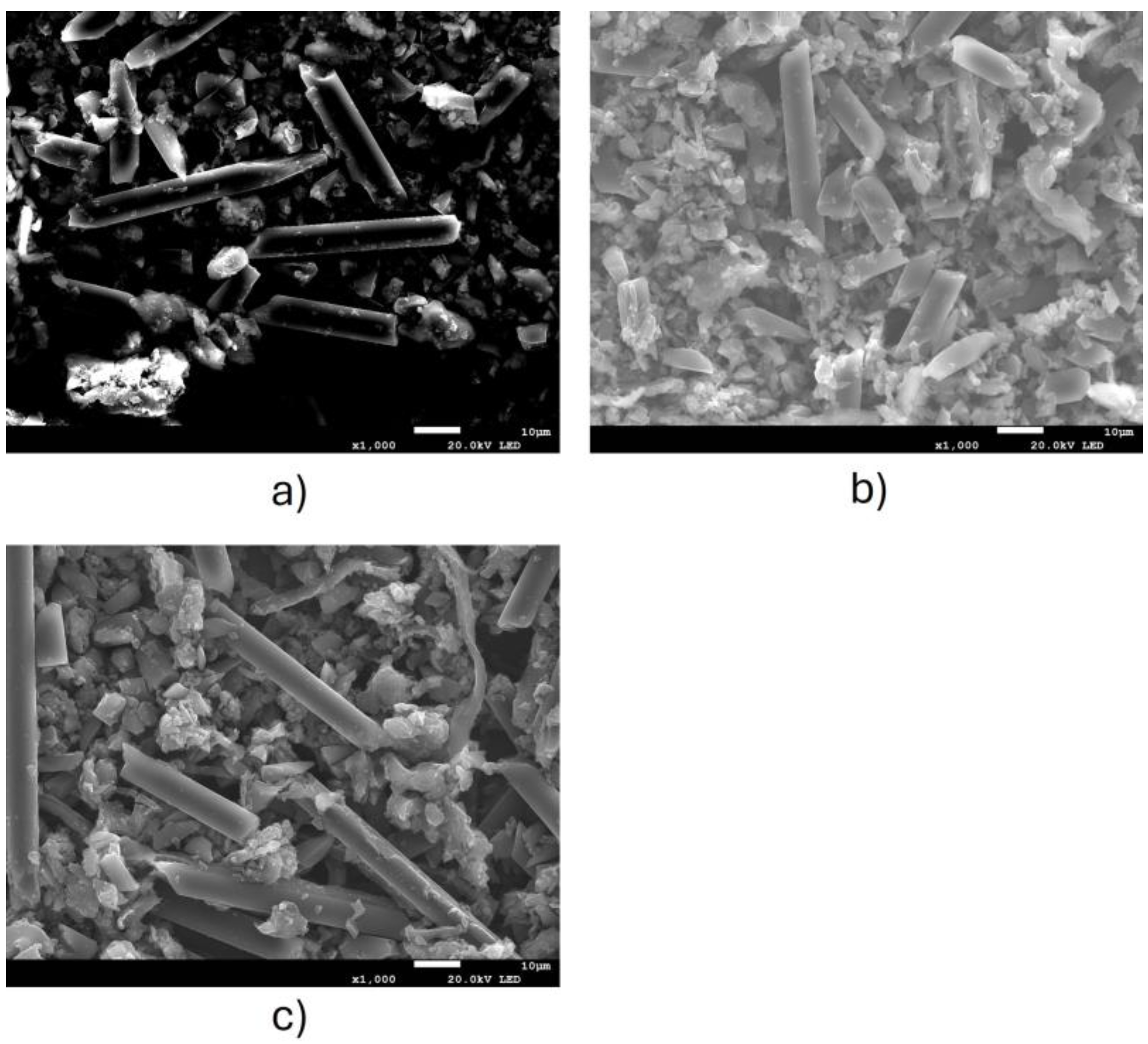

| Sample | Weathering | Diameter (µm) | % elongated particles with A/R>3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCPP RTM | 0h | 5.92±0.88 | 53% |

| 500h | 6.75±0.52 | 60% | |

| 750h | 6.99±0.72 | 73% | |

| SP3 RTM | 0h | 6.64±0.49 | 60% |

| 500h | 6.77±0.32 | 53% | |

| 750h | 6.77±0.55 | 67% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).