Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Contrail Retrievals

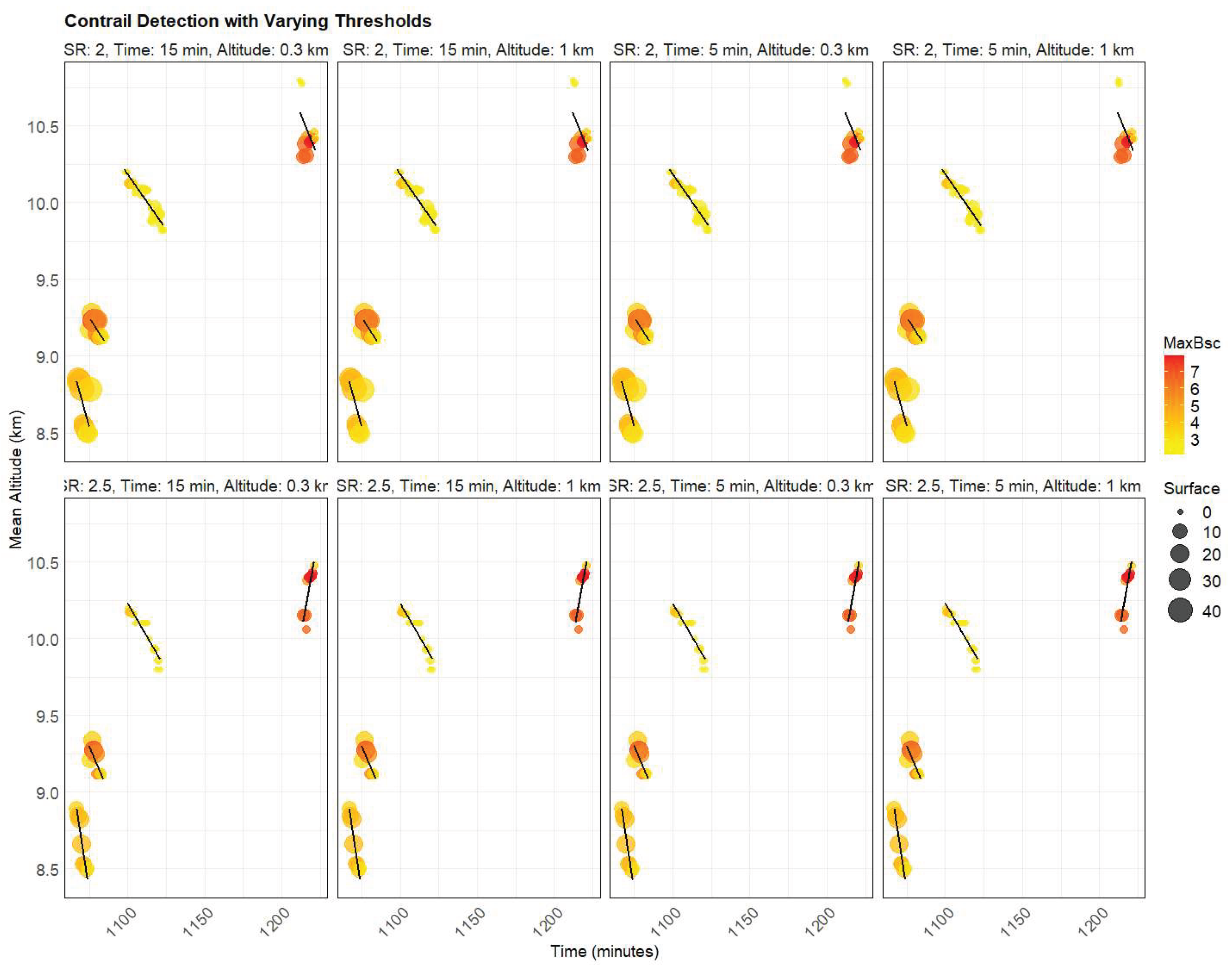

2.2. Contrail detection thresholds and their properties

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Contrail geometrical features, case studies

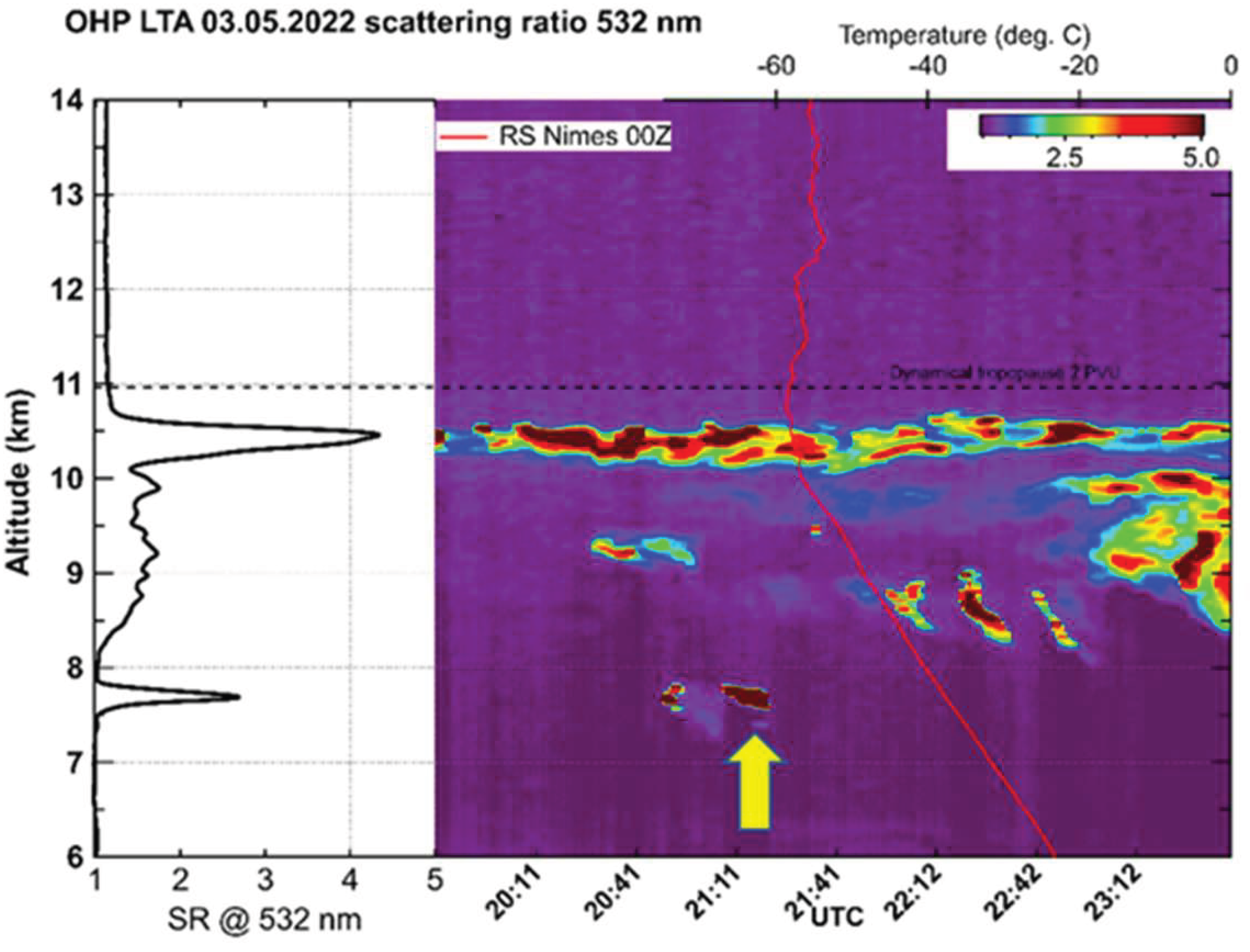

3.1.1. Contrail cases during 13.01.2023

| Cases | Time | Altitude | Speed | Direction | Dist. | Type | Engines | Fuel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 17:17 | 7.9 | 832 | 138 | 2.8 | Airbus A320 | 2 turbofan | kerosene |

| 17:22 | 8.6 | 948 | 140 | 2.0 | Airbus A319 | 2 turbofan | kerosene | |

| II | 17:43 | 10.3 | 1007 | 141 | 2.6 | Dassault Falcon FA7X | 3 turbofan | kerosene |

| III | 18:24 | 10.2 | 893 | 137 | 0.5 | Boeing B738 | 2 turbofan | kerosene |

| 18:29 | 10.3 | 941 | 141 | 2.4 | Airbus A320 | 2 turbofan | kerosene | |

| 18:46 | 8.6 | 943 | 140 | 3.1 | Airbus A320 | 2 turbofan | kerosene | |

| 18:48 | 9.8 | 963 | 142 | 3.4 | Airbus A320 | 2 turbofan | kerosene | |

| IV | 19:03 | 8.9 | 832 | 142 | 3.0 | Airbus A20N | 2 turbofan | kerosene |

| 19:26 | 7.9 | 859 | 140 | 2.9 | Airbus A319 | 2 turbofan | kerosene |

| Time (min) | SR | Altitude (km) |

Time (min) |

COD | Duration (min) |

Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of thresholds | 0.1-2.5 | 5-30 | 5.8-13.8 | 4 | 0.10-0.40 | 1.5-5.0 |

| Optimal combinations | 0.3-1.0 | 5-15 | 7.2 | 4 | 0.40 | 2.0-2.5 |

| Selection | 0.3 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 4 | 0.40 | 2.1 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, D.K.; Sanyal, S.; Wuebbles, D.J. Understanding the role of contrails and contrail cirrus in climate change: a global perspective. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 9219–9262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Fahey, D.; Skowron, A.; Allen, M.; Burkhardt, U.; Chen, Q.; Doherty, S.; Freeman, S.; Forster, P.; Fuglestvedt, J.; et al. The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmospheric Environ. 2021, 244, 117834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, R.; Engberg, Z.; Schumann, U.; Voigt, C.; Shapiro, M.; Rohs, S.; Stettler, M.E.J. Global aviation contrail climate effects from 2019 to 2021. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 6071–6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Bryukhanov, I.; Loktyushin, O.; Ni, E.; Samokhvalov, I.; Pustovalov, K.; Kuchinskaia, O. Comparison of the Contrail Drift Parameters Calculated Based on the Radiosonde Observation and ERA5 Reanalysis Data. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keckhut, P.; Hauchecorne, A.; Bekki, S.; Colette, A.; David, C.; Jumelet, J. Indications of thin cirrus clouds in the stratosphere at mid-latitudes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2005, 5, 3407–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keckhut, P.; Borchi, F.; Bekki, S.; Hauchecorne, A.; SiLaouina, M. Cirrus classification at mid-latitude from systematic lidar observations. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. 2006, 45, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keckhut, P.; Perrin, J.-M.; Thuillier, G.; Hoareau, C.; Porteneuve, J.; Montouxc, N. Subgrid-scale cirrus observed by lidar at mid-latitude: variability effects of the cloud optical depth. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2013, 7, 073530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Meijer, V.; Barrett, S.R.H.; Eastham, S.D. Evaluation of the APCEMM intermediate-fidelity contrail model using LIDAR observations. In Proceedings of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 11–15 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alraddawi, D.; Keckhut, P.; Mandija, F.; Sarkissian, A.; Pietras, C.; Dupont, J.-C.; Farah, A.; Hauchecorne, A.; Porteneuve, J. Calibration of Upper Air Water Vapour Profiles Using the IPRAL Raman Lidar and ERA5 Model Results and Comparison to GRUAN Radiosonde Observations. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dione, C.; Dupont, J.-C.; Caillault, K.; Gourgue, N.; Pietras, C.; Haeffelin, M. Estimation of optical and microphysical characteristics of contrails using Lidar at SIRTA observatory, Paris. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2025, Vienna, Austria, 14–19 April 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, S.; Cao, C.; Heidinger, A.; Ignatov, A.; Key, J.; Smith, T. The advanced very high resolution radiometer: Contributing to earth observations for over 40 years. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E351–E366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, D.P.; Bedka, S.T.; Minnis, P.; Spangenberg, D.; Khlopenkov, K.; Chee, T.; Smith, W.L., Jr. Northern Hemisphere contrail properties derived from Terra and Aqua MODIS data for 2006 and 2012. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 5313–5330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärcher, B.; Burkhardt, U.; Unterstrasser, S.; Minnis, P. Factors controlling contrail cirrus optical depth. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 6229–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diarra, S.; Baray, J.-L.; Montoux, N.; et al. Combining LIDAR, all-sky camera, and ECMWF-ERA5 reanalysis to investigate contrail formation and evolution over Clermont-Ferrand, France on June 2, 2023. Atmospheric Research 2025, 213, 108500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rap, A.; Forster, P.M.; Jones, A.; Boucher, O.; Haywood, J.M.; Bellouin, N.; De Leon, R.R. Parameterization of contrails in the UK Met Office Climate Model. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos 2010, 115, D10205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.; Bellouin, N.; Boucher, O. Long-term upper-troposphere climatology of potential contrail occurrence over the Paris area derived from radiosonde observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärcher, B. Formation and Radiative Forcing of Contrail Cirrus. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megill, L.; Grewe, V. Investigating the limiting aircraft-design-dependent and environmental factors of persistent contrail formation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 4131–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnis, P.; Bedka, S.T.; Duda, D.P.; Bedka, K.M.; Chee, T.; Ayers, J.K.; Palikonda, R.; Spangenberg, D.A.; Khlopenkov, K.V.; Boeke, R. Linear contrail and contrail cirrus properties determined from satellite data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3220–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C.; Coauthors. ML-CIRRUS: The Airborne Experiment on Natural Cirrus and Contrail Cirrus with the High-Altitude Long-Range Research Aircraft HALO. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2017, 98, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, R.; Shariff, K. Contrail Modeling and Simulation. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2016, 48, 393–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamquin, N.; Stubenrauch, C.J.; Gierens, K.; Burkhardt, U.; Smit, H. A global climatology of upper-tropospheric ice supersaturation occurrence inferred from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder calibrated by MOZAIC. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjani, S.; Tesche, M.; Bräuer, P.; Sourdeval, O.; Quaas, J. Satellite observations of the impact of individual aircraft on ice crystal number in thin cirrus clouds. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL096173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarry, G.; Very, P.; Heffar, A.; Torjman-Levavasseur, V. Deep semantic contrails segmentation of GOES-16 satellite images: A hyperparameter exploration. In Proceedings of the SESAR Innovation Days 2024, Brussels, Belgium, 3–6 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wolf, K.; Boucher, O.; Bellouin, N. Radiative effect of two contrail cirrus outbreaks over Western Europe estimated using geostationary satellite observations and radiative transfer calculations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL108452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Gao, L.; Li, X.; Pan, W.; Ni, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, F. High-resolution thermal infrared contrails images identification and classification method based on SDGSAT-1. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2024, 131, 103980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin, F.; Fréville, P.; Montoux, N.; Baray, J.-L. Original and Low-Cost ADS-B System to Fulfill Air Traffic Safety Obligations during High Power LIDAR Operation. Sensors 2023, 23, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, K.; Bellouin, N.; Boucher, O. Distribution and morphology of non-persistent contrail and persistent contrail formation areas in ERA5. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 5009–5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraedts, S.; et al. A scalable system to measure contrail formation on a per-flight basis. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 015008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, S.; Gierens, K.; Rohs, S. How well can persistent contrails be predicted? An update. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 7911–7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherlock, V.; Garnier, A.; Hauchecorne, A.; Keckhut, P. Implementation and validation of a Raman lidar measurement of middle and upper tropospheric water vapour. Appl. Opt. 1999, 38, 5838–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaykin, S.; Godin-Beekmann, S.; Hauchecorne, A.; Pelon, J.; Ravetta, F.; Keckhut, P. Stratospheric smoke layer with unprecedentedly high backscatter observed by lidars above southern france. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 1639–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandija, F.; Keckhut, P.; Alraddawi, D.; Khaykin, S.; Sarkissian, A. Climatology of Cirrus Clouds over Observatory of Haute-Provence (France) Using Multivariate Analyses on Lidar Profiles. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, L.; Keckhut, P.; Chanin, M.L.; Hauchecorne, A. Cirrus climatological results from lidar measurements at OHP (44°N, 6°E). Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 1687–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneep, M.; Ubachs, W. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy & Radiative Transfer 2005, 92, 293–310.

- Bates, R.D. Rayleigh scattering by air. Planet Space Sci. 1984, 32, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucholtz, A. Rayleigh-scattering calculations for the terrestrial atmosphere. Appl. Opt. 1995, 34, 2765–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, C. Lidar and radiometric observations of cirrus clouds. J. Atmos. Sci. 1973, 30, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, K.; Cho, B.S. Subvisual-thin cirrus lidar dataset for satellite verification and climatological research. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1992, 31, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.N.; Chiang, C.W.; Nee, J.B. Lidar ratio and depolarization ratio for cirrus clouds. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 6470–6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakoudi, K.; Stachlewska, I.; Ritter, C. An extended lidar-based cirrus cloud retrieval scheme: first application over an Arctic site. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 8553–8580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandinger, U.; Tesche, M.; Seifert, P.; Ansmann, A.; Müller, D.; Althausen, D. Size matters: Influence of multiple scattering on CALIPSO light-extinction profiling in desert dust. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L00E08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, V.; Szczap, F.; Alkasem, A.; Mioche, G.; Cornet, C. Empirical model of multiple-scattering effect on single-wavelength lidar data of aerosols and clouds. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 1729–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakov, V.; Szczap, F.; Mioche, G.; Cornet, C. Multiple-scattering effects on single-wavelength lidar sounding of multi-layered clouds. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 3011–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Díaz, C.; Sicard, M.; Comerón, A.; dos Santos Oliveira, D.C.F.; Muñoz-Porcar, C.; Rodríguez-Gómez, A.; Lewis, J.R.; Welton, E.J.; Lolli, S. Geometrical and optical properties of cirrus clouds in Barcelona, Spain: analysis with the two-way transmittance method of 4 years of lidar measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2024, 17, 1197–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, K.; Comstock, J. A midlatitude cirrus cloud climatology from the facility for atmospheric remote sensing. Part III: Radiative properties. J. Atmos. Sci. 2001, 58, 2113–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, C.M.R.; Dilley, A.C. Remote Sounding of High Clouds. IV: Observed Temperature Variations in Cirrus Optical Properties. J. Atmos. Sci. 1981, 38, 1069–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, A.; Pelon, J.; Vaughan, M.A.; Winker, D.M.; Trepte, C.R.; Dubuisson, P. Lidar multiple scattering factors inferred from CALIPSO lidar and IIR retrievals of semi-transparent cirrus cloud optical depths over oceans. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 2759–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.A.; Vaughan, M.A.; Kuehn, R.E.; Winker, D.M. The Retrieval of Profiles of Particulate Extinction from Cloud–Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations (CALIPSO) Data: Uncertainty and Error Sensitivity Analyses. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol. 2013, 30, 395–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, P.; Ansmann, A.; Müller, D.; Wandinger, U.; Althausen, D.; Heymsfeld, A.J.; Massie, S.T.; Schmitt, C. Cirrus optical properties observed with lidar, radiosonde, and satellite over the tropical Indian Ocean during the aerosol-polluted northeast and clean maritime southwest monsoon. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, D17205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisi, D.; Keckhut, P.; Liberti, G.L.; Cardillo, F.; Congeduti, F. Midlatitude cirrus classification at Rome Tor Vergata through a multichannel Raman-Mie-Rayleigh lidar. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 11853–11868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoareau, C.; Keckhut, P.; Noel, V.; Chepfer, H.; Baray, J.-L. A decadal cirrus clouds climatology from ground-based and spaceborne lidars above the south of France (43.9° N–5.7° E). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 6951–6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Kattawar, G.W.; Yang, P.; Hu, Y.X.; Baum, B.A. Sensitivity of depolarized lidar signals to cloud and aerosol particle properties. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 2006, 100, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, C.A.; Liu, Z.; Reagan, J.A.; Vaughan, M.A.; Winker, D.M.; Osborn, M.T.; Hunt, W.H.; Powell, K.A.; Trepte, C.R. CALIPSO Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nohra, R.; Parol, F.; Dubuisson, P. Comparison of Cirrus Cloud Characteristics as Estimated by A Micropulse Ground-Based Lidar and A Spaceborne Lidar CALIOP Datasets Over Lille, France (50.60 N, 3.14 E). EPJ Web Conf. 2016, 119, 16005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakaki, E.; Balis, D.S.; Amiridis, V.; Kazadzis, S. Optical and geometrical characteristics of cirrus clouds over a Southern European lidar station. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 5519–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, A.O.; Portmann, R.W.; Daniel, J.S.; Miller, H.L.; Eubank, C.S.; Solomon, S.; Dutton, E.G. Retrieval of ice crystal effective diameters from ground-based near-infrared spectra of optically thin cirrus. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, D22201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.M.; Haywood, J.; Marenco, F.; O'Sullivan, D.; Meyer, J.; Thorpe, R.; Gallagher, M.W.; Krämer, M.; Bower, K.N.; Rädel, G.; Rap, A.; Woolley, A.; Forster, P.; Coe, H. A methodology for in-situ and remote sensing of microphysical and radiative properties of contrails as they evolve into cirrus. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 8157–8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immler, F.; Treffeisen, R.; Engelbart, D.; Krüger, K.; Schrems, O. Cirrus, contrails, and ice supersaturated regions in high pressure systems at northern mid latitudes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2008, 8, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwabuchi, H.; Yang, P.; Liou, K.N.; Minnis, P. Physical and optical properties of persistent contrails: Climatology and interpretation. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos 2012, 117, D06215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 hourly data on pressure levels from 1979 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) Available online. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on pressure levels from 1979 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) Available online. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiuk, D.K.; Khan, M.A.H.; Shallcross, D.E.; Lowenberg, M.H. A Commercial Aircraft Fuel Burn and Emissions Inventory for 2005–2011. Atmosphere 2016, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groß, S.; Jurkat-Witschas, T.; Li, Q.; Wirth, M.; Urbanek, B.; Krämer, M.; Weigel, R.; Voigt, C. Investigating an indirect aviation effect on mid-latitude cirrus clouds – linking lidar-derived optical properties to in situ measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 8369–8381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenthaler, V.; Homburg, F.; Jäger, H. Contrail observations by ground-based scanning lidar: Cross-sectional growth. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1995, 22, 3501–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poellot, M.R.; Arnott, W.P.; Hallett, J. In situ observations of contrail microphysics and implications for their radiative impact. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos 1999, 104, 12077–12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, K. Contrail-cirrus and their potential for regional climate change. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 1997, 78, 1885–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, D.; Wang, Z. Contrails of Small and Very Large Optical Depth. J. Atmos. Sci. 2010, 67, 3065–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenow, J.; Fricke, H. Individual Condensation Trails in Aircraft Trajectory Optimization. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Ranjan, R.; Yau, M.-K.; Bera, S.; Rao, S.A. Impact of high- and low-vorticity turbulence on cloud–environment mixing and cloud microphysics processes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 12317–12329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lifespan | Maturity | Persistence | Age | Width | Shape | Edges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short-lived | young | fresh | < 10 min | > 3 km | linear | sharp |

| long-lived | mature | persistent | < 1 h | > 7 km | linear | diffusive |

| old | spreading | > 1 h | > 21 km | non-linear | diffusive |

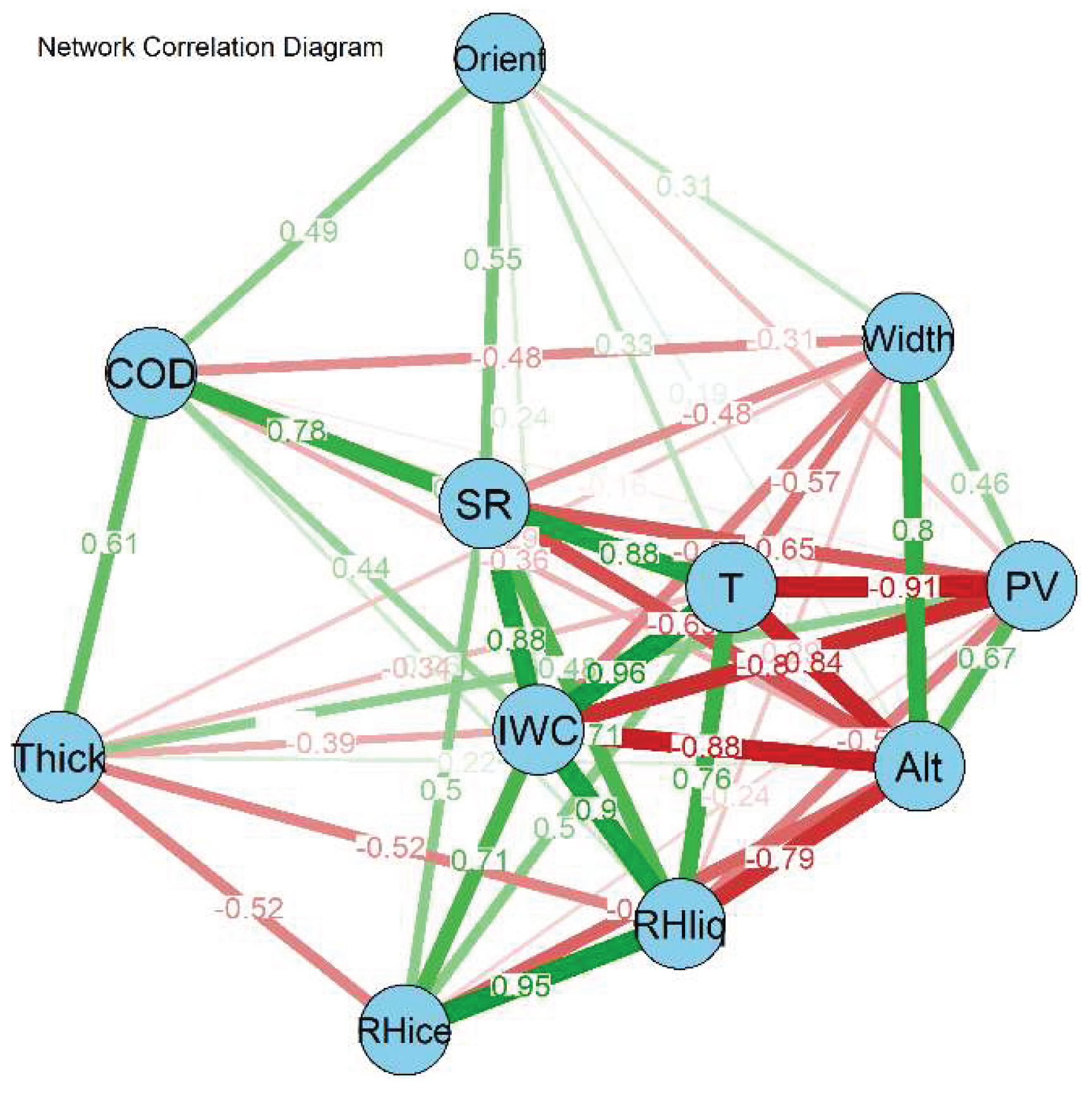

| Geometrical/optical parameters | Thermodynamic parameters | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Alt. (Km) |

SRmax | Thick. (Km) |

Width (Km) |

Orient. (10-3) |

COD | T (oC) |

RHliq (%) |

RHice (%) |

PV (K·m²·kg⁻¹·s⁻¹) |

IWC (kg·m−3) |

Gr. |

| 1 | 8.7 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 2 | -1.1 | 0.10 | -56.7 | 74.8 | 108.8 | 2E-06 | 4.0E-7 | PC |

| 2 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 1.1 | 9 | -0.4 | 0.35 | -60.3 | 84.5 | 126.9 | 4E-06 | 4.0E-7 | PC |

| 3 | 10.0 | 4.2 | 0.1 | 28 | -0.3 | 0.05 | -60.4 | 89.7 | 134.6 | 3E-06 | 1.0E-7 | PC |

| 4 | 10.3 | 7.9 | 0.8 | 18 | 0.9 | 0.28 | -55.8 | 69.9 | 101.2 | 2E-06 | 1.0E-7 | PC |

| Geometrical/optical parameters | Thermodynamic parameters | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Alt. (Km) |

SRmax | Thick. (Km) |

Width (Km) |

Orient. (10-3) |

COD | T (oC) |

RHliq (%) |

RHice (%) |

PV (K·m²·kg⁻¹·s⁻¹) |

IWC (kg·m−3) |

Gr. |

| 5 | 8.7 | 13 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.33 | -41.4 | 115.8 | 147.1 | 2.4e-07 | 1.8E-5 | PC |

| 6 | 6.9 | 35 | 0.3 | 10.7 | -0.1 | 0.22 | -44.3 | 28.5 | 43.6 | 3.0e-06 | 1.6E-5 | NoC |

| 7 | 6.7 | 56 | 0.7 | 13.6 | -0.2 | 0.98 | -44.3 | 28.5 | 43.6 | 3.0e-06 | 1.6E-5 | NoC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).