Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

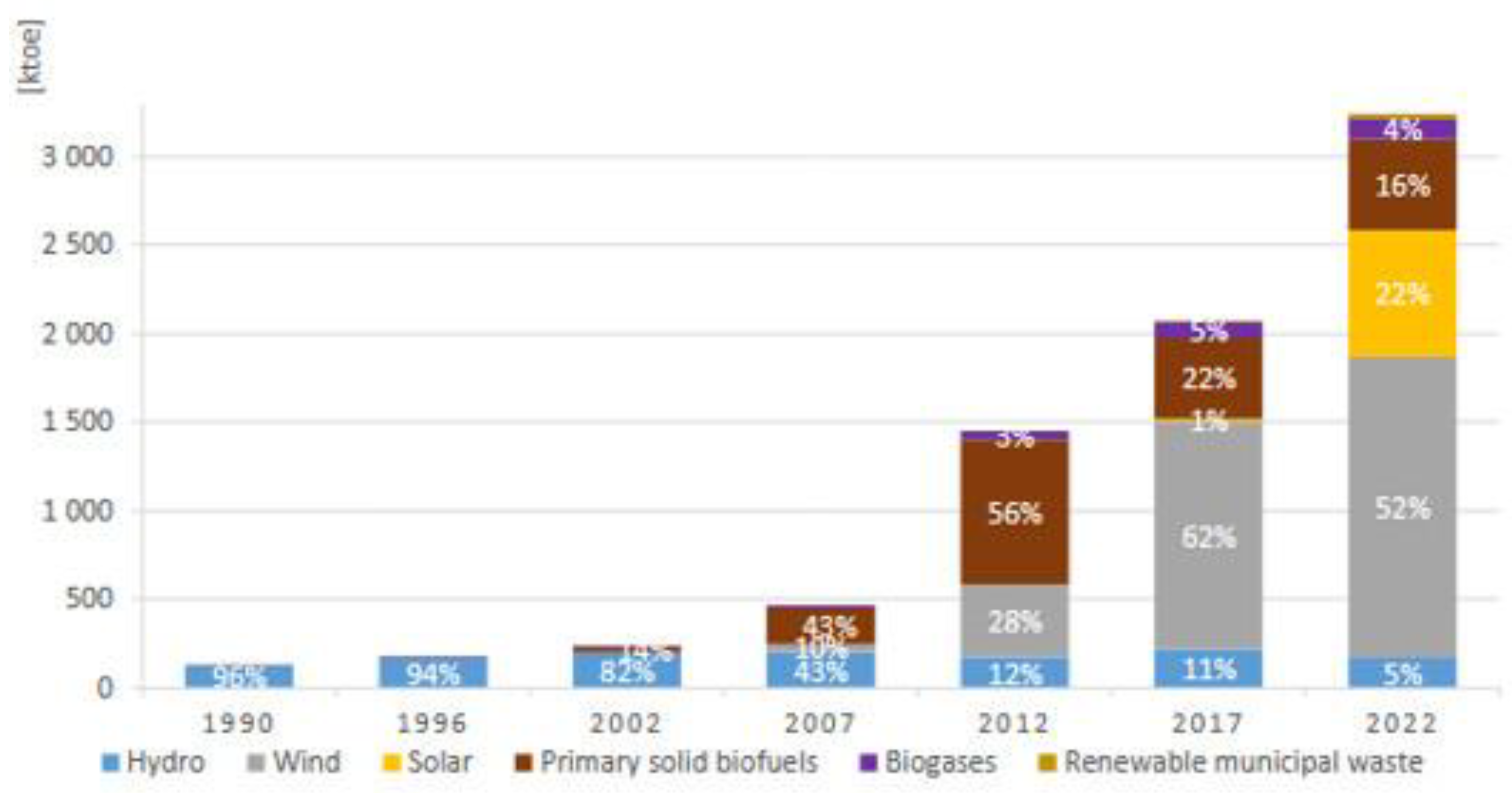

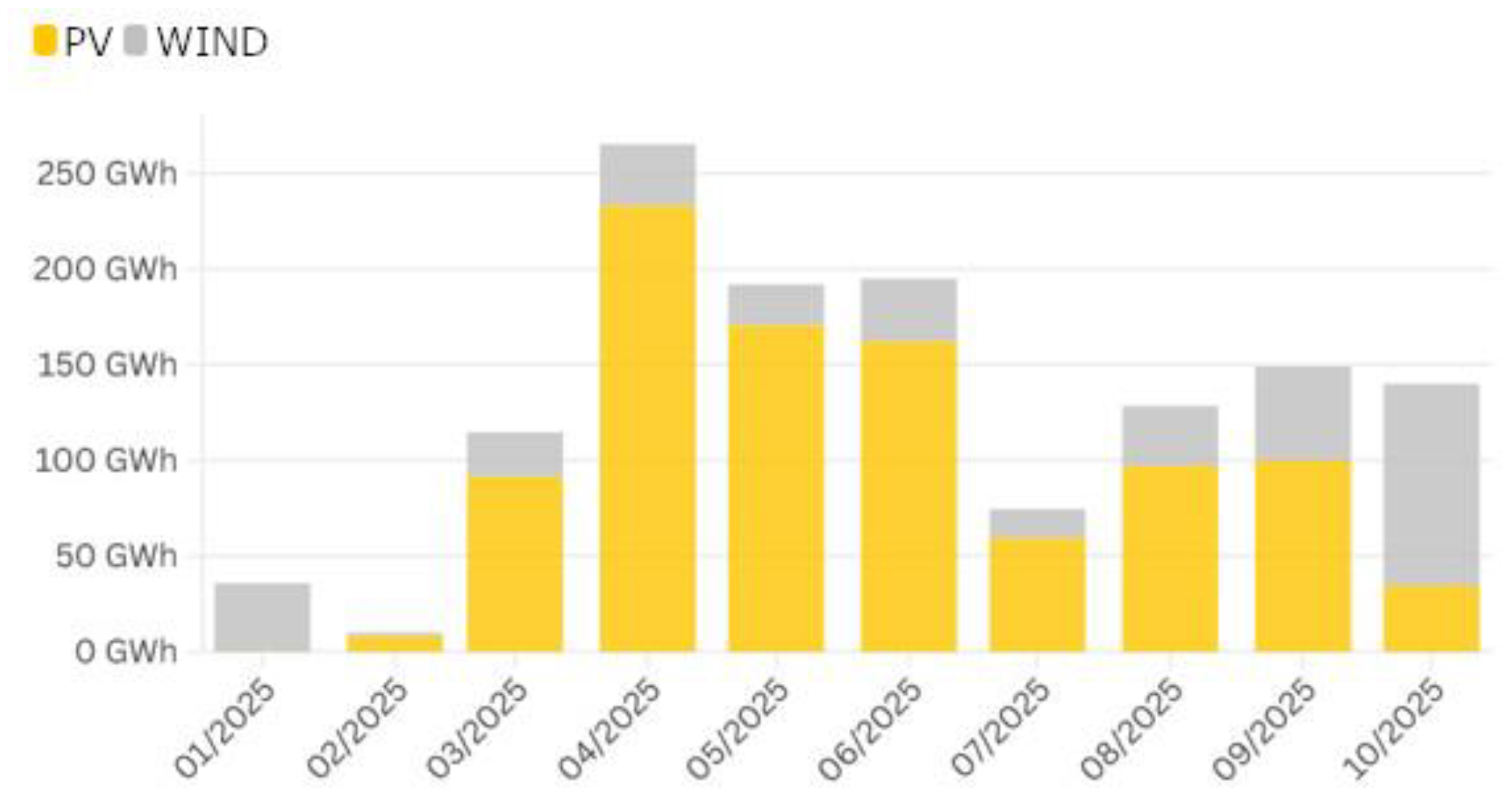

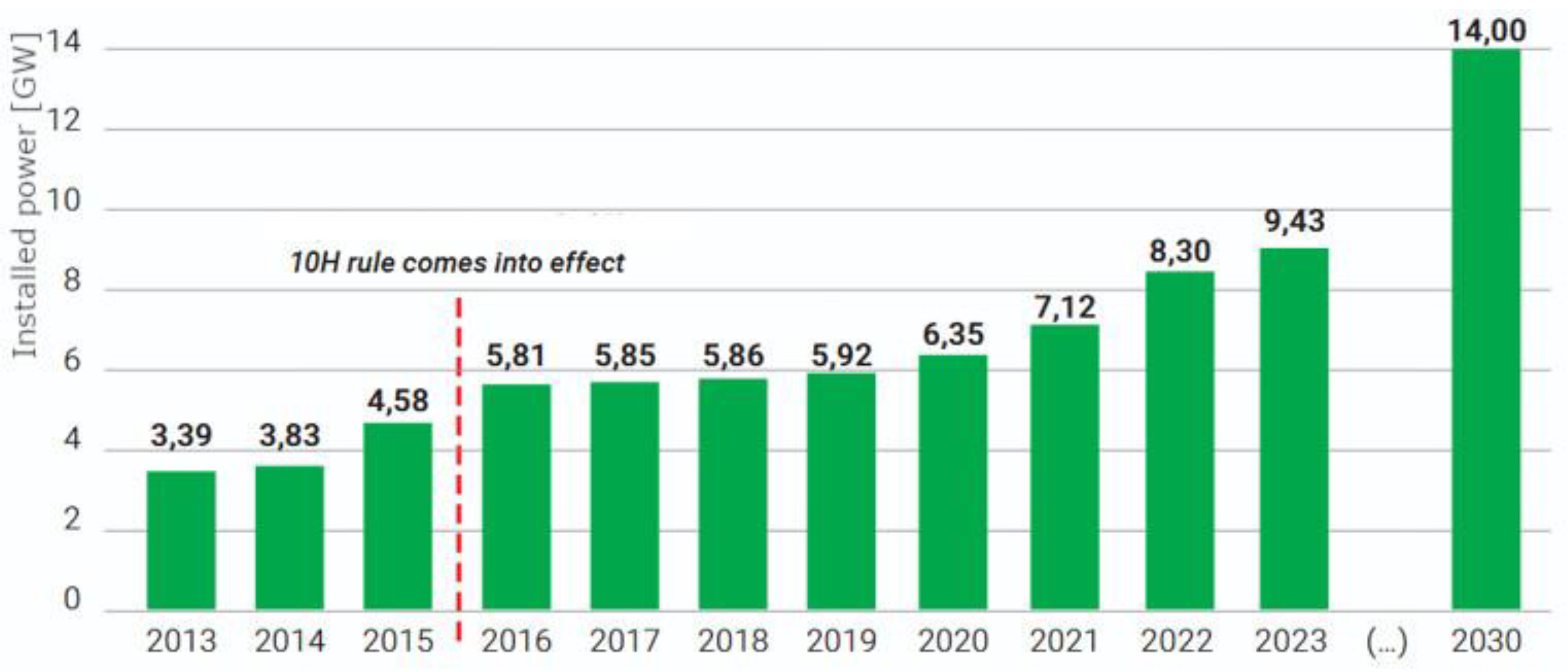

1.1. National Power System (NPS) in Poland

1.2. Operation Strategy of Wind Power Plants

2. Materials and Methods

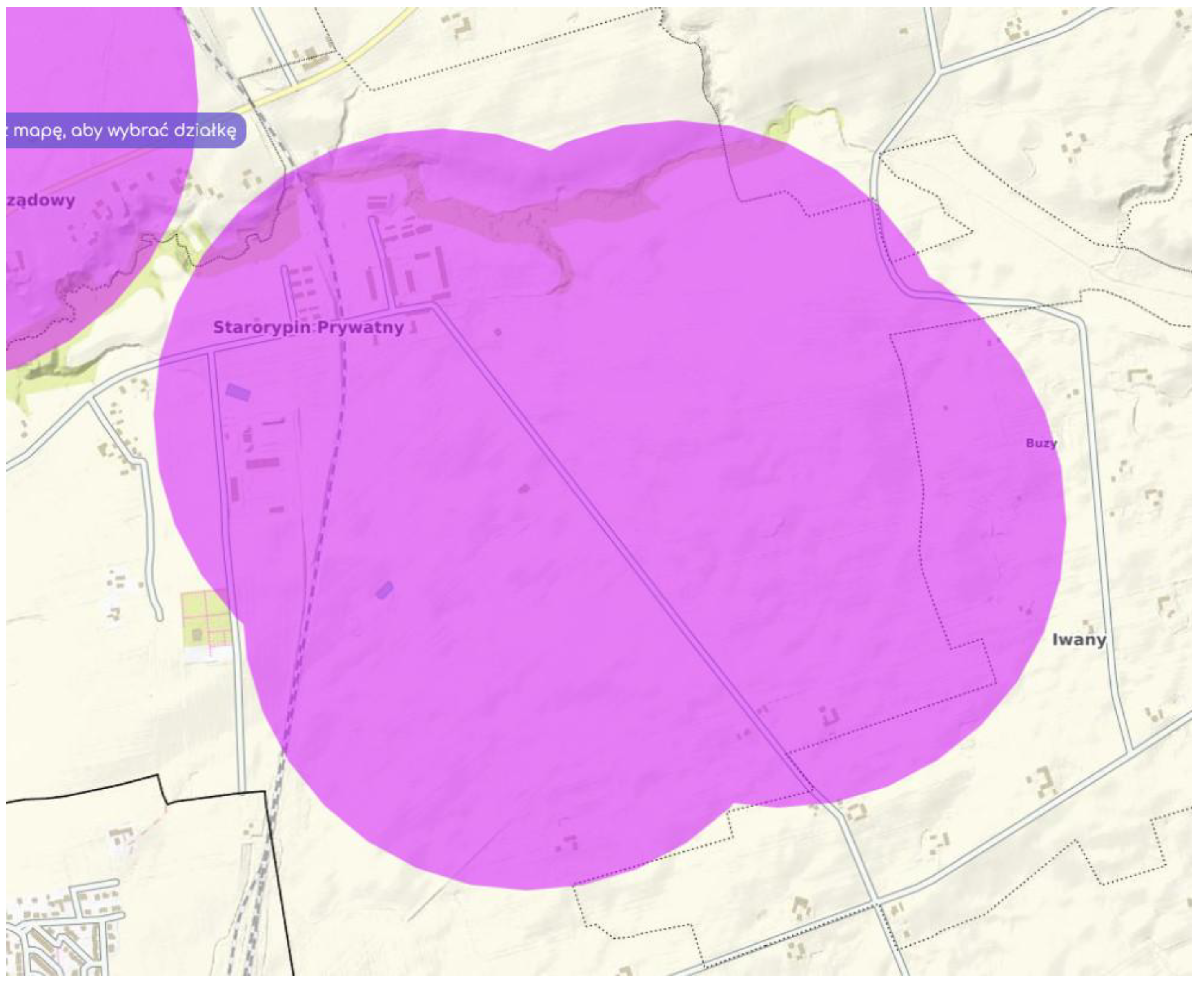

2.1. Object of Analysis

3. Results and discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Polish Wind Energy Association (PWEA); TPA Poland / Baker Tilly TPA; DWF. Wind Energy in Poland: 2024 Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.psew.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Wind-energy-in-Poland-Report-2024.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity. Available online: https://transparency.entsoe.eu/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Public Net Electricity Generation in Poland. Available online: https://energy-charts.info/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska. Krajowy Plan w dziedzinie Energii i Klimatu [National Energy and Climate Plan]. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/krajowy-plan-na-rzecz-energii-i-klimatu (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Gawlikowska-Fyk, A. From 2025 Coal Will Leave the Polish Energy System in Waves. Forum Energii. 2021. Available online: https://www.forum-energii.eu/en/from-2025-coal-will-leave-the-polish-energy-system-in-waves (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Viola, L.; Mohammadi, S.; Dotta, D.; Hesamzadeh, M.R.; Baldick, R.; Flynn, D. Ancillary services in power system transition toward a 100% non-fossil future: Market design challenges in the United States and Europe. Electric Power Systems Research 2024, 236, 110885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polskie Sieci Elektroenergetyczne (PSE). System Data [in Polish]. Available online: https://www.pse.pl/dane-systemowe (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Min, C.-G. Analyzing the Impact of Variability and Uncertainty on Power System Flexibility. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochenek, B.; Jurasz, J.; Jaczewski, A.; Stachura, G.; Sekuła, P.; Strzyżewski, T.; Wdowikowski, M.; Figurski, M. Day-Ahead Wind Power Forecasting in Poland Based on Numerical Weather Prediction. Energies 2021, 14, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum Energii. October 2025 — On the Wings of Wind, Yet Under Constraints [in Polish; in: “Monthly Bulletin”]. Available online: https://www.forum-energii.eu/miesiecznik, (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Solar Power Europe. Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Schaefer, J.L.; Siluk, J.C.M. An Algorithm-based Approach to Map the Players’ Network for Photovoltaic Energy Businesses. Int. J. Sustain. Energy Plan. Manag. 2021, 30, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, I.; Moreno-Munoz, A.; Quintero-Jiménez, P.; Garcia-Torres, F.; Gonzalez-Redondo, M.J. Electricity demand during pandemic times: The case of the COVID-19 in Spain. Energy Policy 2021, 148, 111954–111964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A European Green Deal. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Devetakovi’c, M.; Djordjevi’c, D.; Radojevi’c, M.; Krsti’c-Furundži’c, A.; Burduhos, B.-G.; Martinopoulos, G.; Neagoe, M.; Lobaccaro, G. Photovoltaics on Landmark Buildings with Distinctive Geometries. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinopoulos, G. Are rooftop photovoltaic systems a sustainable solution for Europe? A life cycle impact assessment and cost analysis. Appl. Energy 2020, 257, 114035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mularczyk, A. Analysis of the Energy Mix in Poland and the European Union in Terms of Renewable Energy Prospects. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2024, 208, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, S.; Sołtysiak, A.; Migawa, K.; Neubauer, A. Simple mathematical model to predict the amount of energy produced in wind turbine – preliminary study. MATEC Web Conf. 2021, 332, 01004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). IEC 61400-1: Wind Turbines—Part 1: Design Requirements; IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De Laurentis, C.; Windemer, R. When the turbines stop: Unveiling the factors shaping end-of-life decisions of ageing wind infrastructure in Italy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 113, 103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Ding, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, X. Probabilistic modeling for long-term fatigue reliability of wind turbines based on Markov model and subset simulation. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 173, 107685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Dana, S.; Clausen, P.; Wood, D. A Simple Method for Modelling Fatigue Spectra of Small Wind Turbine Blades. Wind Energy 2021, 24, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Fatigue Damage and Reliability Assessment of Wind Turbine Structure During Service Utilizing Real-Time Monitoring Data. Buildings 2024, 14, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xiang, D.; Tan, Y.F.; Nie, Y.H.; Cao, H.J.; Wei, Y.Z.; Zeng, D.; Shen, Y.H.; Shen, G. Analysis of wind turbine gearbox’s environmental impact considering its reliability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.R.; Stinebaugh, J.A.; Briand, D.; Benjamin, A.S.; Linsday, J. Wind Turbine Reliability: A Database and Analysis Approach; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2008; Report No. SAND2008-0983. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1028916 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhao, H. Method for Evaluating the Reliability and Competitive Failure of Wind Turbine Gearbox Bearings Considering the Fault Incubation Point. Energies 2023, 16, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.P. Evaluating the environmental impacts of recycling wind turbines. Wind Energy 2019, 22, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.M.; Whale, J. A Mini-Review of End-of-Life Management of Wind Turbines: Current Practices and Closing the Circular Economy Gap. Waste Manag. Res. 2022, 40, 1730–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, L.; Gonzalez, E.; Rubert, T.; Smolka, U.; Melero, J.J. Lifetime extension of onshore wind turbines: A review covering Germany, Spain, Denmark, and the UK. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WindEurope. Decommissioning of Onshore Wind Turbines—Industry Guidance Document; WindEurope: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://proceedings.windeurope.org/biplatform/rails/active_storage/blobs/WindEurope-decommissioning-of-onshore-wind-turbines.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Rubert, T.; McMillan, D.; Niewczas, P. A Decision Support Tool to Assist with Lifetime Extension of Wind Turbines. Renew. Energy 2018, 120, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, L.; Gonzalez, E.; Rubert, T.; Smolka, U.; Melero, J.J. Lifetime extension of onshore wind turbines: A review covering Germany, Spain, Denmark, and the UK. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serri, L.; Lembo, E.; Airoldi, D.; Gelli, C.; Beccarello, M. Wind Energy Plants Repowering Potential in Italy: Technical-Economic Assessment. Renew. Energy 2018, 115, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmenar-Santos, A.; Campíñez-Romero, S.; Pérez-Molina, C.; Mur-Pérez, F. Repowering: An Actual Possibility for Wind Energy in Spain in a New Scenario without Feed-in-Tariffs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, A.; Windemer, R. Repower to the People: The Scope for Repowering to Increase the Scale of Community Shareholding in Commercial Onshore Wind Assets in Great Britain. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 92, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windemer, R.; Cowell, R. Are the Impacts of Wind Energy Reversible? Critically Reviewing the Research Literature, the Governance Challenges and Presenting an Agenda for Social Science. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 79, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.M.F.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Velenturf, A.P.M.; Jensen, P.D.; Ibarra, D. Circular Economy Business Models and Technology Management Strategies in the Wind Industry: Sustainability Potential, Industrial Challenges and Opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 163, 112523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowska, M.; Mikołajczak, J.; Borowski, S.; Dolatowski, Z.J.; Marć-Pieńkowska, J.; Budziński, W. Effect of Noise Generated by the Wind Turbine on the Quality of Goose Muscles and Abdominal Fat. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2014, 14, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczak, J.; Borowski, S.; Marć-Pieńkowska, J.; Odrowąż-Sypniewska, G.; Bernacki, Z.; Siódmiak, J.; Szterk, P. Preliminary studies on the reaction of growing geese (Anser anser f. domestica) to the proximity of wind turbines. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2013, 16, 679–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karwowska, M.; Mikołajczak, J.; Dolatowski, Z.J.; Borowski, S. The effect of varying distances from the wind turbine on meat quality of growing-finishing pigs. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2015, 15(4), 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeis, S. A Simple Analytical Wind Park Model Considering Atmospheric Stability. Wind Energy 2010, 13, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Bian, W.; Yang, Q. Large Eddy Simulation for the Effects of Ground Roughness and Atmospheric Stratification on the Wake Characteristics of Wind Turbines Mounted on Complex Terrains. Energy Conversion and Management 2022, 268, 115977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

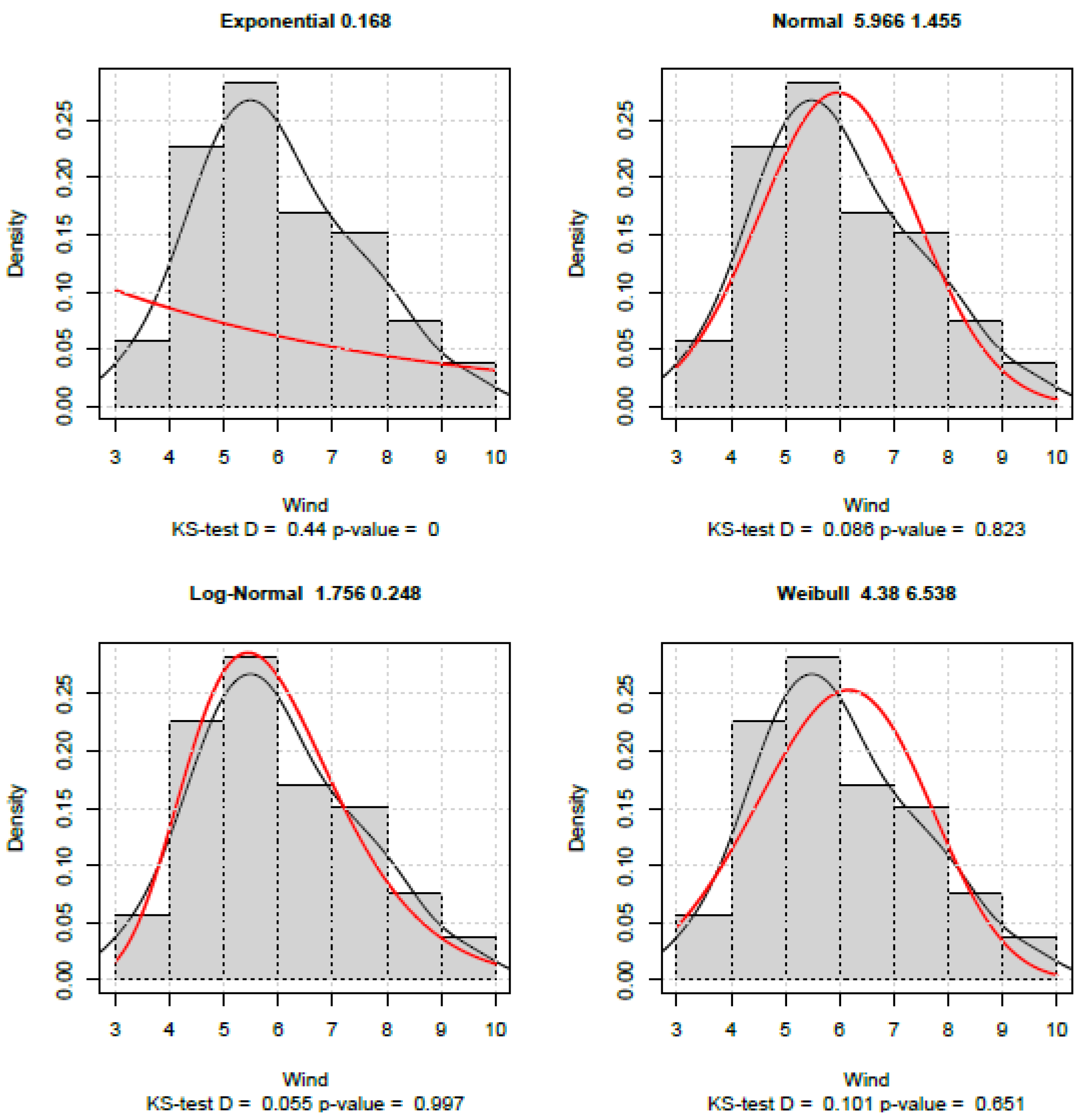

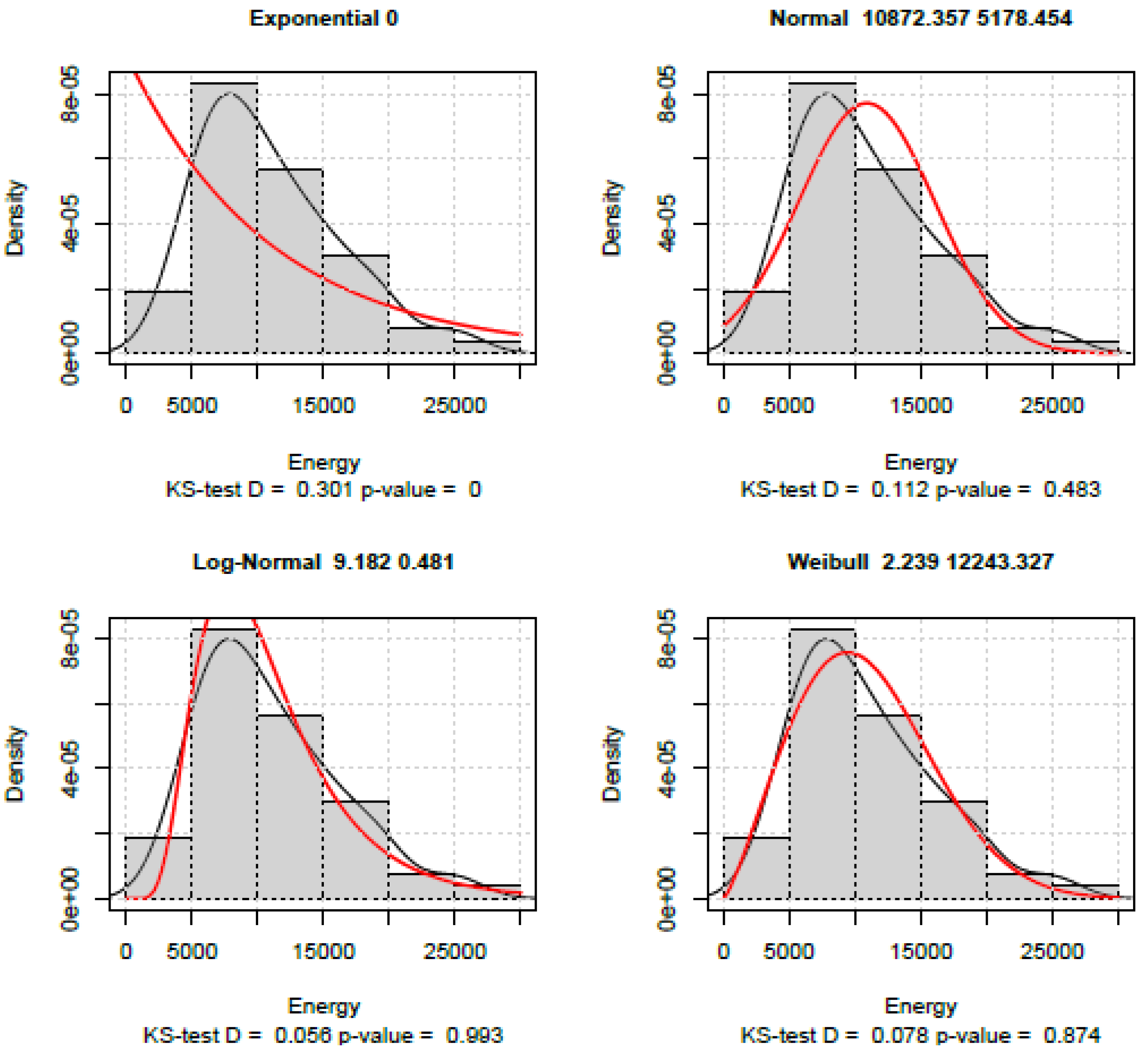

- Carrillo, C.; Obando-Montaño, A.F.; Cidrás, J.; Díaz-Dorado, E. An Approach to Determine the Weibull Parameters for Wind Energy Analysis: The Case of Galicia (Spain). Energies 2014, 7, 2676–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Haider, A.; Ullah, Z.; Russo, M.; Casolino, G.M.; Azeem, B. Comparative Analysis of Eight Numerical Methods Using Weibull Distribution to Estimate Wind Power Density for Coastal Areas in Pakistan. Energies 2023, 16, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousla, M.; Maatallah, T.; El Alj, A.; et al. Analysis and Comparison of Wind Potential by Estimating Weibull Parameters Using Different Methods: Application to Wind Farm in the Northern of Morocco. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencastre, P.; Yazidi, A.; Lind, P.G. Modeling Wind-Speed Statistics beyond the Weibull Distribution. Energies 2024, 17, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Designation | Turbine Type | Tower Height |

|---|---|---|

| WT1 | Vensys 77/1500 | 100 m |

| WT2 | Vensys 77/1500 | 100 m |

| WT3 | Vestas V90-2.0 MW | 105 m |

| Wind turbine | WT1 | WT2 | WT3 |

|---|---|---|---|

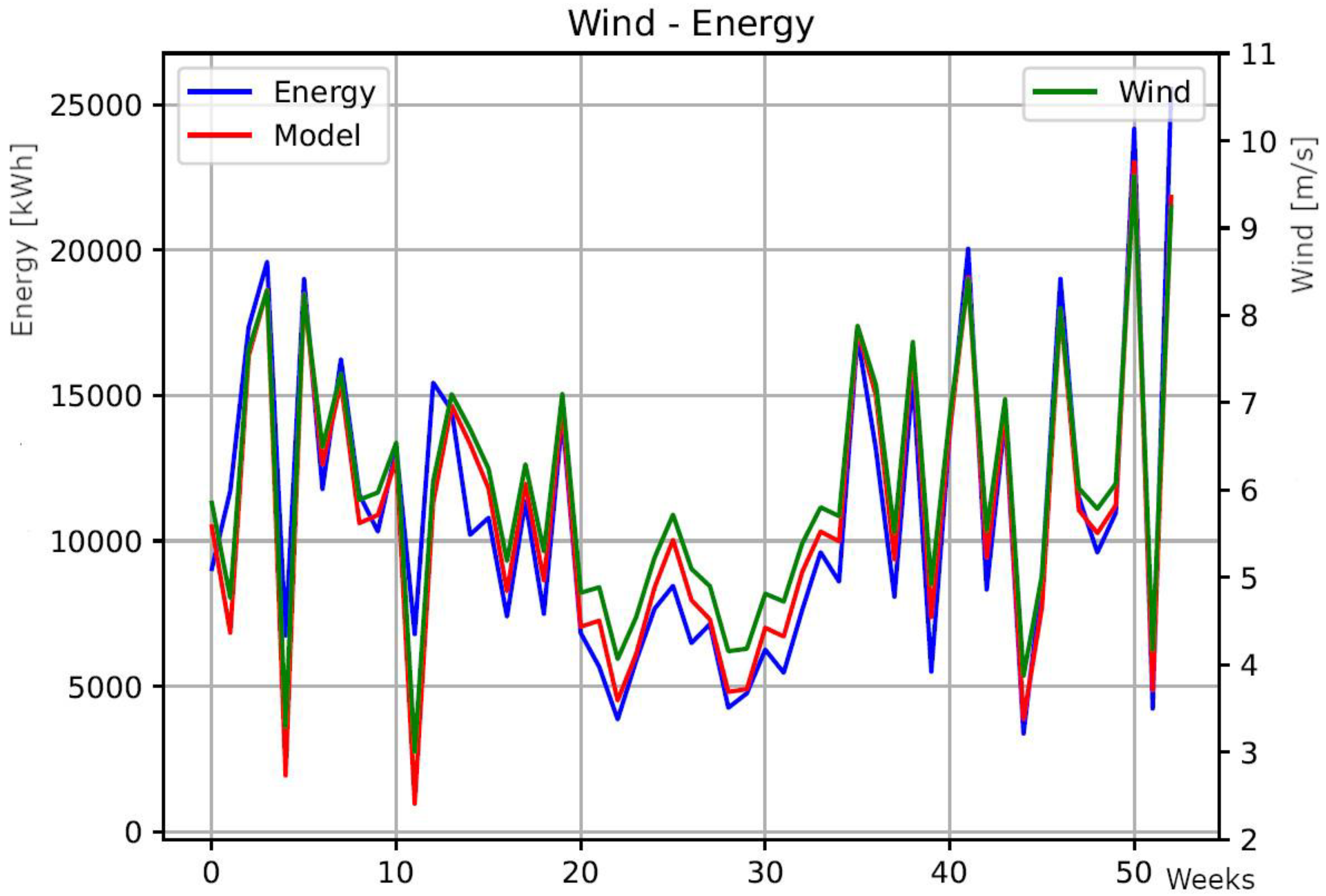

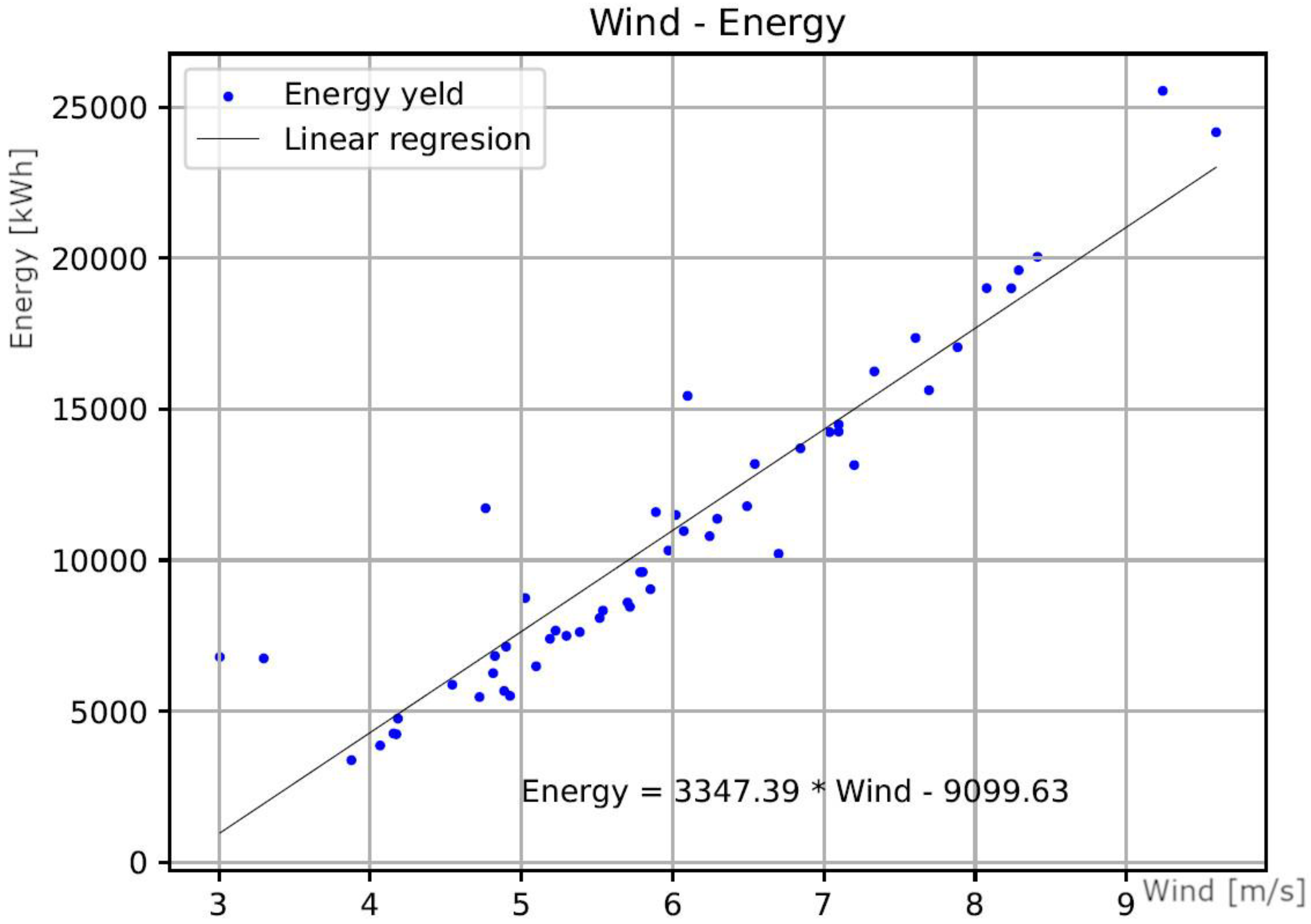

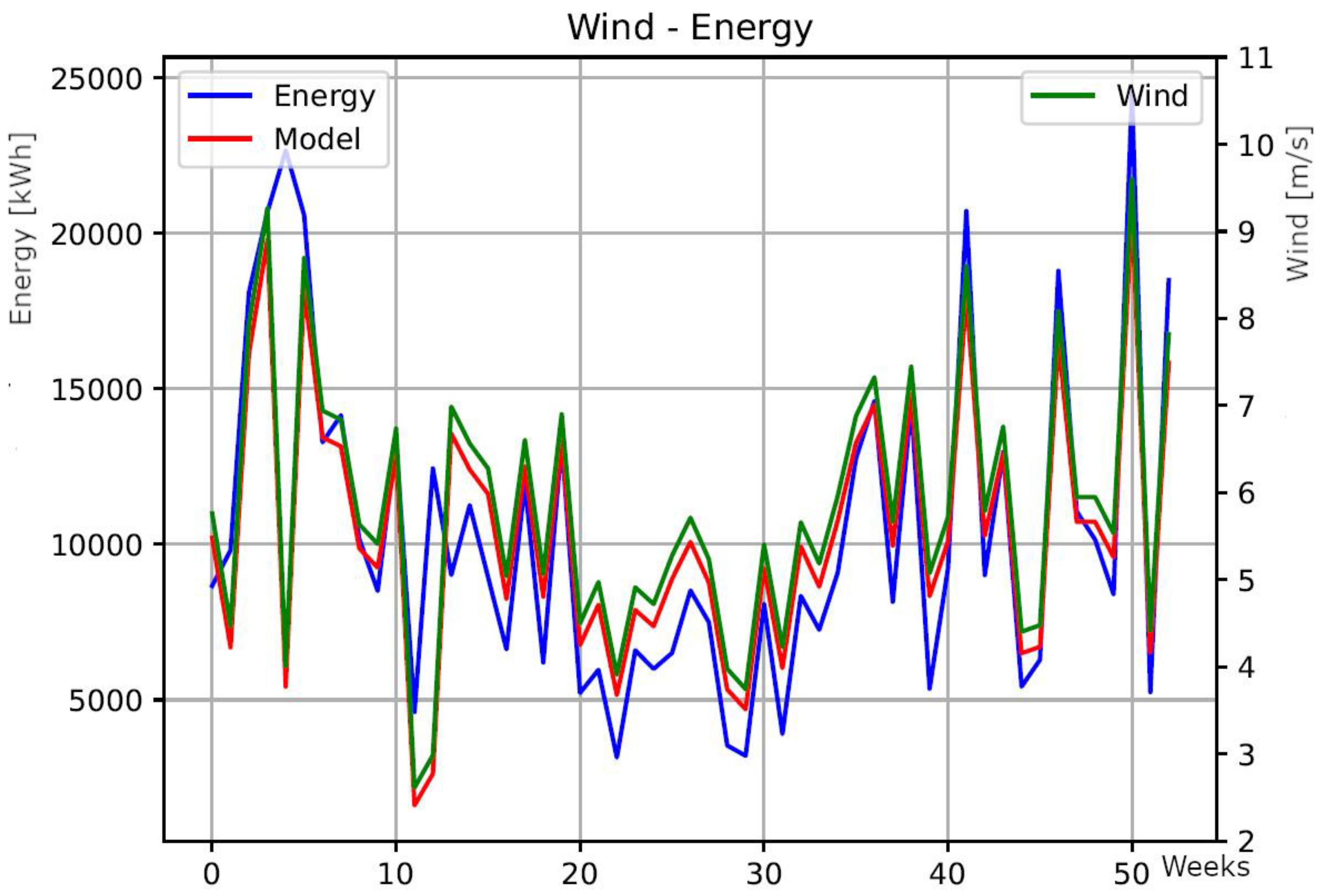

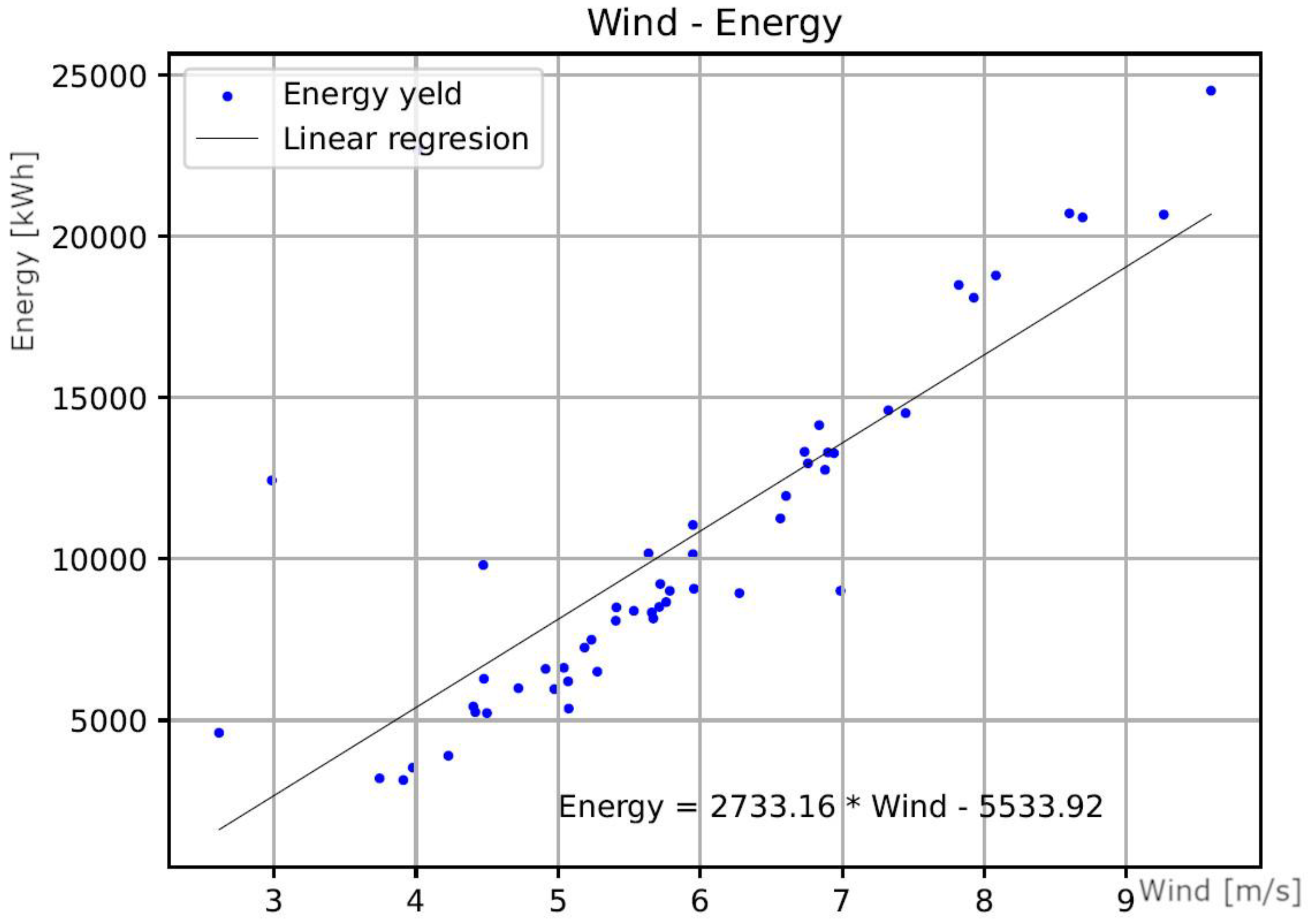

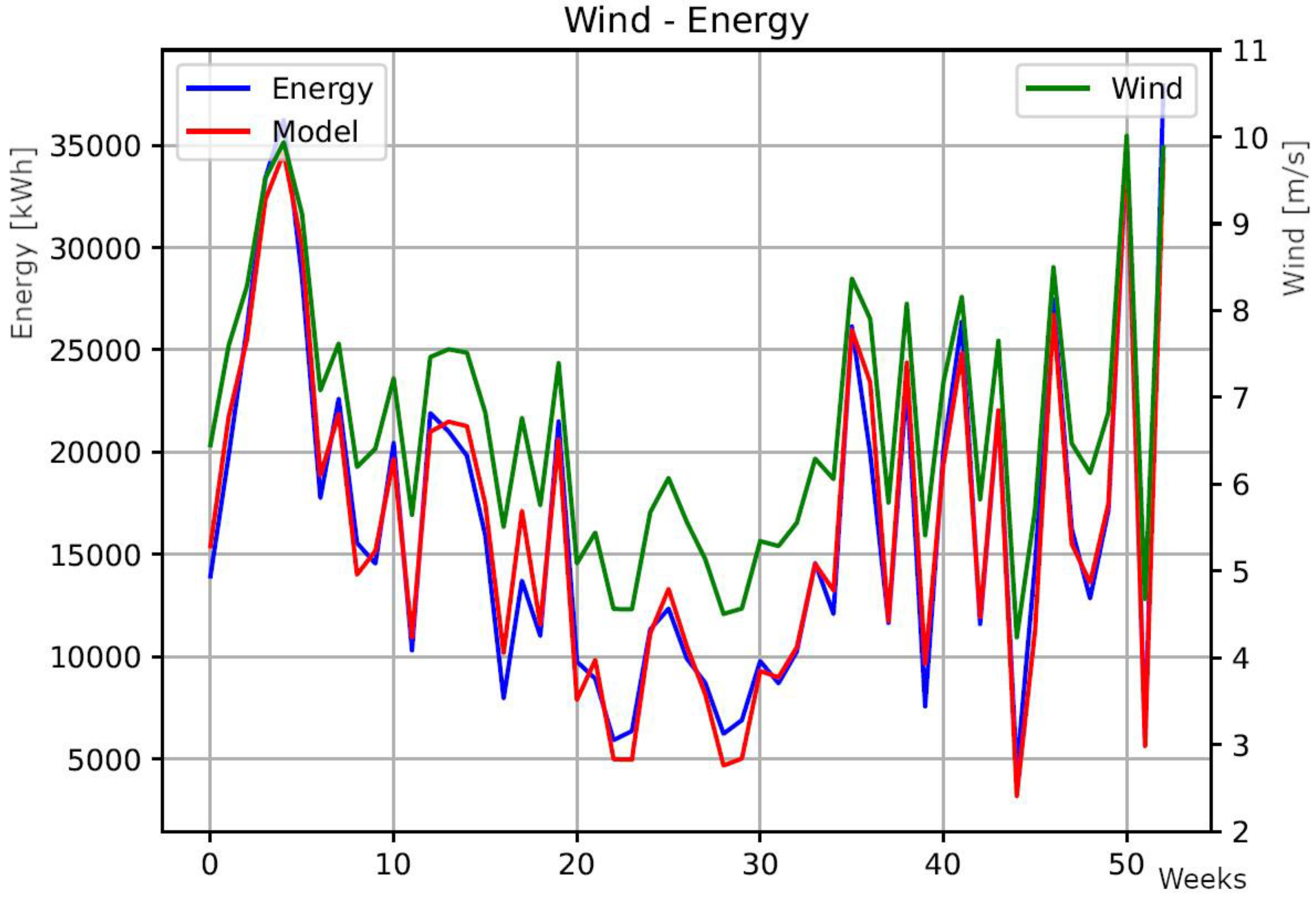

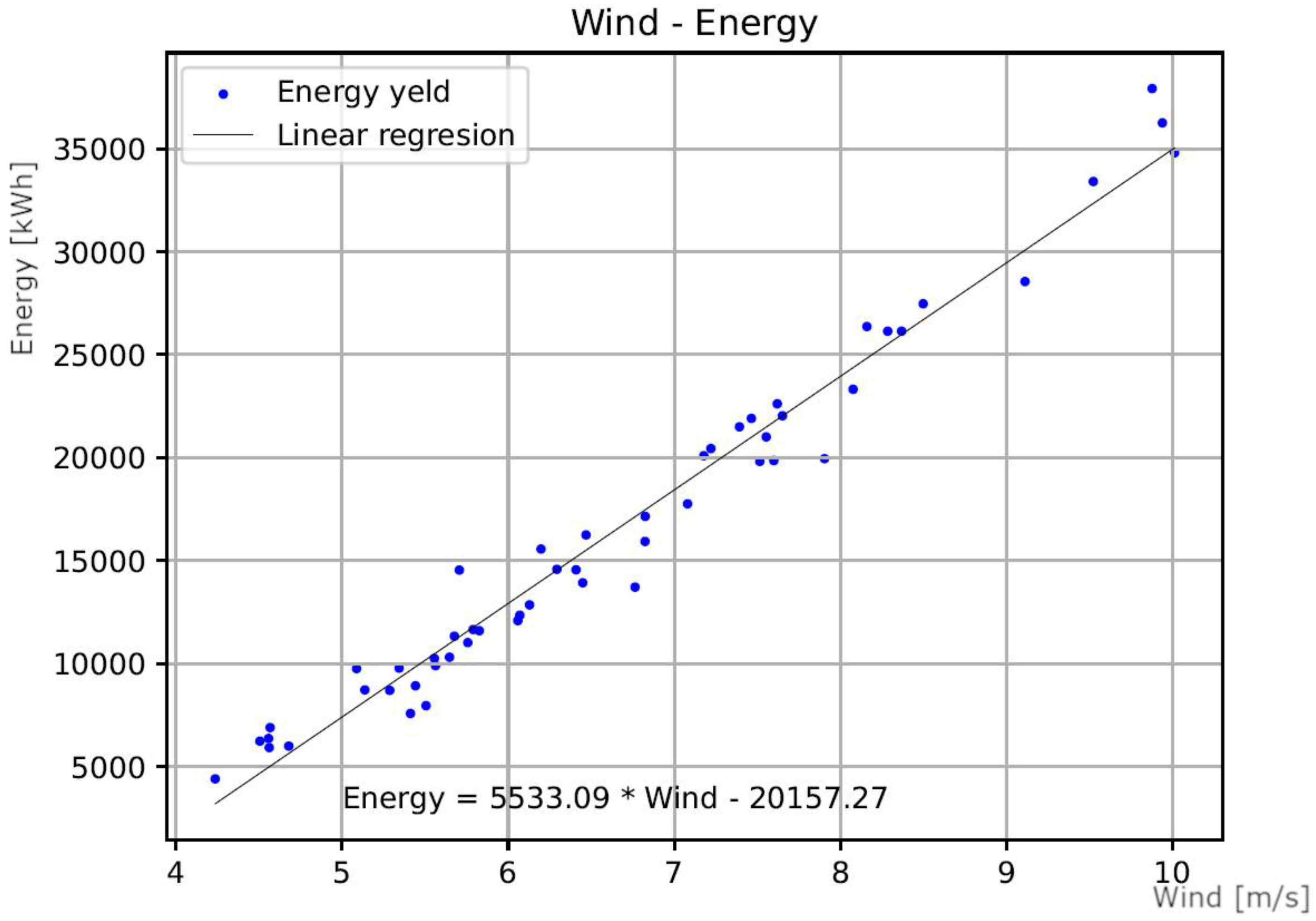

| Linear regresion model | Em=3347.39Vm– 9099.63 | Em=2733.16Vm-5533.92 | Em=5533.09Vm-20157.27 |

| Coefficient | Value of the coefficient | ||

| Correlation R | 0,94054 | 0,785112077 | 0,985528137 |

| R2 | 0,88461 | 0,616400973 | 0,971265709 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0,88235 | 0,608879423 | 0,970702292 |

| Standard error | 1793,16 | 3313,887893 | 1436,826085 |

| Number of observations | 53 | 53 | 53 |

| df | SS | MS | F | Significance F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT1 | Em = 3347.39 Vm – 9099.63 | ||||

| Regression | 1 | 125728 | 1,3E+09 | 391,014204 | 1,4322E-25 |

| Residual | 51 | 163987 | 3215437 | ||

| Total | 52 | 1421268 | |||

| WT2 | Em = 2733.16 Vm – 5533.92 | ||||

| Regression | 1 | 899977432,4 | 899977432,4 | 81,9513 | 3,4277E-12 |

| Residual | 51 | 560074501,2 | 10981852,97 | ||

| Total | 52 | 1460051934 | |||

| WT3 | Em = 5533.09 Vm – 20157.27 | ||||

| Regression | 1 | 3558903030 | 3558903030 | 1723,88284 | 5,512E-41 |

| Residual | 51 | 105287929,1 | 2064469,2 | ||

| Total | 52 | 3664190959 | |||

| Coefficient | Value of the coefficient |

Standard error |

t Stat | p- Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT1 | Em = 3347.39 Vm – 9099.63 | |||||

| a | 3347,387083 | 169,2815664 | 19,7741 | 1,4322E-25 | 3007,54016 | 3687,23401 |

| b | -9099,634354 | 1039,608629 | -8,75294 | 9,8663E-12 | -11186,736 | -7012,5329 |

| WT2 | Em = 2733.16 Vm – 5533.92 | |||||

| a | 2733,16 | 301,92 | 9,05 | 0,00 | 2127,04 | 3339,29 |

| b | -5533,92 | 1821,37 | -3,04 | 0,00 | -9190,47 | -1877,37 |

| WT3 | Em = 5533.09 Vm – 20157.27 | |||||

| a | 5513,09 | 132,78 | 41,52 | 0,00 | 5246,52 | 5779,66 |

| b | -20157,27 | 904,53 | -22,28 | 0,00 | -21973,18 | -18341,35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).