1. Introduction

The transition toward a circular economy has become a critical global priority, emphasizing the recovery and reuse of industrial waste materials to reduce environmental impact and resource depletion [

1,

2]. The automotive and metallurgical sectors, among the largest producers of waste, generate significant quantities of end-of-life tires and electric arc furnace (EAF) dust, both of which contain materials with substantial reuse potential [

3,

4,

5,

6]. In recent years, the concept of resource circularity has been increasingly integrated into materials engineering, driving innovation in recycling technologies and sustainable product design [

7,

8]. Moreover, comprehensive approaches involving life-cycle assessment (LCA) and selective recovery of functional components have demonstrated that such recycling routes can substantially reduce the carbon footprint of industrial systems [

9,

10,

11].

Polymer-based materials, particularly epoxy resins, play a vital role in the electrical and electronics industries due to their excellent dielectric properties, mechanical strength, and thermal stability [

12,

13,

14]. However, their thermosetting nature poses substantial challenges for recycling and reuse [

15,

16]. Recent advances have explored chemical depolymerization, hot-press reconfiguration, and ionic-liquid-assisted degradation as promising methods for recovering epoxy systems [

17,

18,

19,

20]. These approaches not only improve material recyclability but also contribute to reducing solid waste in high-tech sectors such as electrical insulation manufacturing [

13,

15,

21]. In addition, sustainable polymer composites incorporating recycled fillers, such as nanofibers, natural polymers, and industrial residues, have shown potential for high-performance insulation and structural applications [

11,

12,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Parallel to polymer recycling, considerable research attention has been directed toward valorizing waste rubber, particularly from end-of-life vehicle tires, as a secondary resource [

2,

4,

14,

16,

17]. Recycled tire rubber has been utilized as a modifier or filler in a range of applications, including concrete, asphalt, and polymer composites, improving mechanical flexibility, toughness, and thermal insulation [

4,

17,

26]. Furthermore, environmental and health assessments of rubber-derived materials indicate that, when properly processed, they meet safety criteria for use in construction and civil engineering [

18]. Incorporating tire rubber into polymer matrices not only supports waste reduction but also enhances energy absorption and impact resistance, properties valuable in both structural and electrical components [

26,

27,

28]. Some studies have even demonstrated the feasibility of using rubber–soil mixtures for seismic isolation of electrical transformers, highlighting the synergy between recycled materials and electrotechnical infrastructure [

28].

Among metal-based waste products, EAF dust represents a foremost source of recoverable zinc oxide (ZnO). This by-product, if untreated, poses severe environmental risks due to its heavy metal content, yet it can be efficiently processed into high-purity ZnO through hydrometallurgical or pyrometallurgical routes [

29,

30]. Recent works have demonstrated that ZnO obtained from recycled EAF dust can be effectively utilized in producing varistors and other ceramic components, exhibiting favorable electrical and structural characteristics [

29,

30,

31]. The optimization of such recovery processes supports both sustainable metallurgy and the circular use of materials in electronic and power applications [

31,

32]. ZnO is also an established functional filler in polymer composites, improving dielectric strength, thermal conductivity, and partial discharge resistance–properties essential for high-voltage insulation materials [

22,

23,

31].

While separate research streams have explored the recycling of epoxy resins, rubber particles, and ZnO-based fillers, limited studies have investigated their combined use to develop environmentally sustainable electrical insulation systems. Integrating these waste-derived components within an epoxy matrix could simultaneously address ecological concerns and advance functional performance in high-voltage engineering. The resulting composite insulation material may exhibit modified dielectric strength, breakdown behavior, and interfacial polarization characteristics, potentially offering a green alternative to conventional synthetic fillers [

7,

19,

21,

22,

31].

According to our findings from the literature review, there are very few, if any, publications that address materials such as epoxy, waste ZnO fillers, and waste rubber for potential use in high-voltage technology. Based on these findings, the present study explores the integration of recycled zinc oxide and tire rubber powders as fillers in epoxy resin composites intended for high-voltage insulation applications. The investigation compares the dielectric breakdown strength of pure epoxy, epoxy with 10 wt.% ZnO, epoxy with 10 wt.% tire rubber, and epoxy with 20 wt.% tire rubber. The results provide insight into the influence of inorganic and organic recycled fillers on the electrical strength of epoxy-based insulating materials, supporting the transition toward sustainable and circular solutions in high-voltage insulation systems.

Therefore, the present study investigates the potential use of waste tire rubber and ZnO recovered from EAF dust as fillers in epoxy resin to develop a sustainable insulation material suitable for high-voltage applications. Four formulations were examined: pure epoxy, epoxy with 10 wt.% ZnO filler, epoxy with 10 wt.% tire rubber, and epoxy with 20 wt.% tire rubber. The breakdown voltage of each sample was measured to evaluate the influence of the waste-derived fillers on dielectric performance, providing insights into their suitability for environmentally conscious high-voltage insulation systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 (Materials and Methods) describes the preparation and characterization of recycled ZnO and waste tire rubber fillers, the fabrication of epoxy composite samples, and the procedure for AC breakdown voltage testing using VDE electrodes.

Section 3 (Results and Discussion) presents the measured breakdown voltages, statistical evaluation using the two-parameter Weibull distribution, and analysis of the influence of recycled fillers on dielectric strength. Section Conclusion summarizes the key findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Filler material characterization and preparation

2.1.1. ZnO filler preparation

The ZnO material used in this study was obtained from the hydrometallurgical recycling of electric arc furnace dust. The recycling process comprised several steps: neutral leaching of EAF dust in distilled water, alkaline leaching using ammonium carbonate, multi-stage pressure filtration, cementation of impurities with zinc dust, and calcination of the final product. The recycling procedure was carried out in a semi-industrial facility at the Institute of Recycling Technologies.

The chemical composition of the recycled ZnO powder was determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis using a Shimadzu 7000P spectrometer (Kyoto, Japan). The results (

Table 1) indicate that zinc is the predominant element, accounting for approximately 96.3 wt.%, confirming the high purity of the recovered ZnO. Minor amounts of sulfur, silicon, calcium, potassium, phosphorus, and trace metals such as iron, copper, vanadium, chromium, and manganese were also detected. These impurities originate from residual components of the EAF dust and the leaching reagents used during the recycling process.

After calcination, ZnO flakes were milled and sieved. The fraction smaller than 0.5 mm was dried at for 24 hours and subsequently cooled in a desiccator prior to incorporation into the epoxy resin.

2.1.2. Rubber filler preparation

Recycled rubber granules were supplied by an industrial partner. We do not disclose the identity of the industrial partner and the method of tire recycling because we are bound by confidentiality. The material was sieved, and the fraction below 1 mm was dried at for three days to prevent thermal degradation.

2.2. Sample preparation

A commercial-grade epoxy resin was used as the matrix material. The resin was mixed with the corresponding hardener at a mass ratio of 70:30 and stirred for 15 minutes at 250 rpm. The filler materials were then incorporated as follows: 10 wt.% ZnO, and 10 or 20 wt.% rubber granules. The mixtures were homogenized by stirring for an additional 15 minutes at 250 rpm. To remove entrapped air, the mixtures were degassed in a vacuum chamber and subsequently poured into silicone molds. Curing was performed in a pressure chamber at 350 kPa for 14 days, followed by post-curing at atmospheric pressure for an additional 7 days. The cured samples were then machined to a constant thickness using a CNC milling machine and polished on both sides up to 5000 grit. The manufactured samples were then cut to size suitable for breakdown voltage testing using AC power frequency.

2.3. Methods

We used a progressive stress test protocol according to [

33], or a short-time (rapid-rise) test [

34]. An increasing voltage with a power frequency of 50 Hz is applied to each sample. We chose the method of applying the voltage by continuously increasing it with time, from zero voltage until dielectric failure of the test sample occurs. The rate-of-rise of the applied voltage is 1 kV/s. The result of the progressive stress test is the breakdown voltage on each sample.

In order to ensure that the tests were carried out under the same conditions, we selected identical samples with the same history before testing. We also ensured that the rate of voltage rise, sample thicknesses, electrode material, and other physical factors affecting the breakdown electric field when an alternating voltage is applied were the same during testing. The experiment was conducted at a temperature of 23 °C to 24 °C and a relative humidity of 47 % ±2 %.

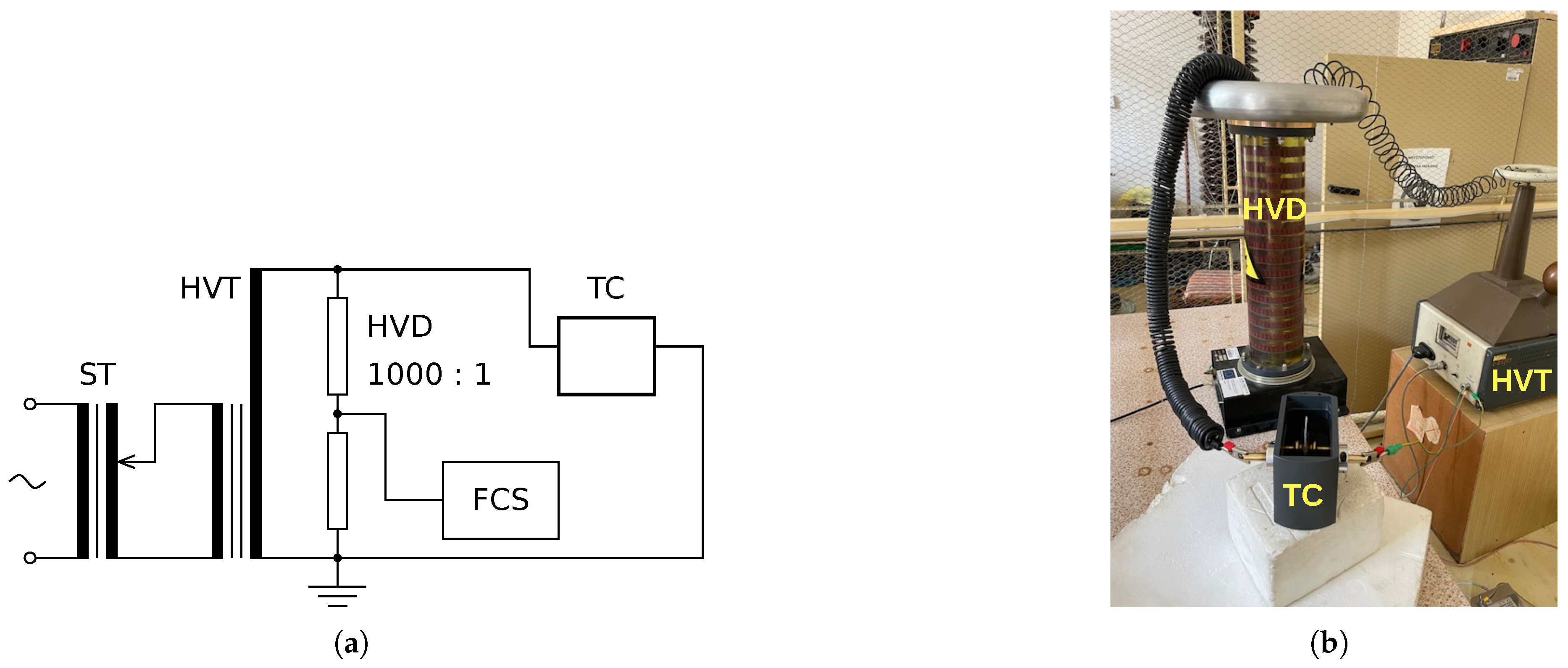

The experiment was conducted using a high-voltage test circuit. The electrical diagram of the measuring circuit, depicted in

Figure 1, consists of a setting transformer (ST) with overcurrent protection, a high-voltage transformer (HVT), a high-voltage divider (HVD) up to 100 kV with a division ratio of 1000:1, a test cell (TC), epoxy samples and epoxy samples with ZnO filler or waste tire rubber particles, silicone insulating oil, four channels scope (FCS) 1 GSa/s, 200 MHz connected.

The test sample was placed in a test cell between two VDE electrodes [

35] placed opposite each other. We used VDE electrodes because a test cell equipped with them was available. The dominant material of the tested samples is epoxy, a relatively hard material. When inserting the sample between the test electrodes, we took care to avoid excessive mechanical stress because of the pressure between the electrodes. To prevent surface discharges and possible flashover on the sample surface, we used silicone insulating oil commonly used for high-voltage equipment. Thus, the electrodes and the test sample were immersed in the oil. The impact of changes in oil quality on test results was minimized through frequent oil changes. Each test on the samples was recorded using FCS until sample breakdown to determine the exact breakdown voltage. The FCS sampling rate was set to 5 kHz. The total time record of the applied voltage was saved in CSV format for further processing. The actual thickness of the sample was measured after the test in the immediate vicinity of the puncture site using a micrometer with a 0.001 mm smallest reading at room temperature. Electrical breakdowns evaluated using the Weibull distribution were considered only on samples whose thickness varied by no more than ±0.02 mm. In this way, five samples from each thickness group were selected for evaluation using the Weibull distribution.

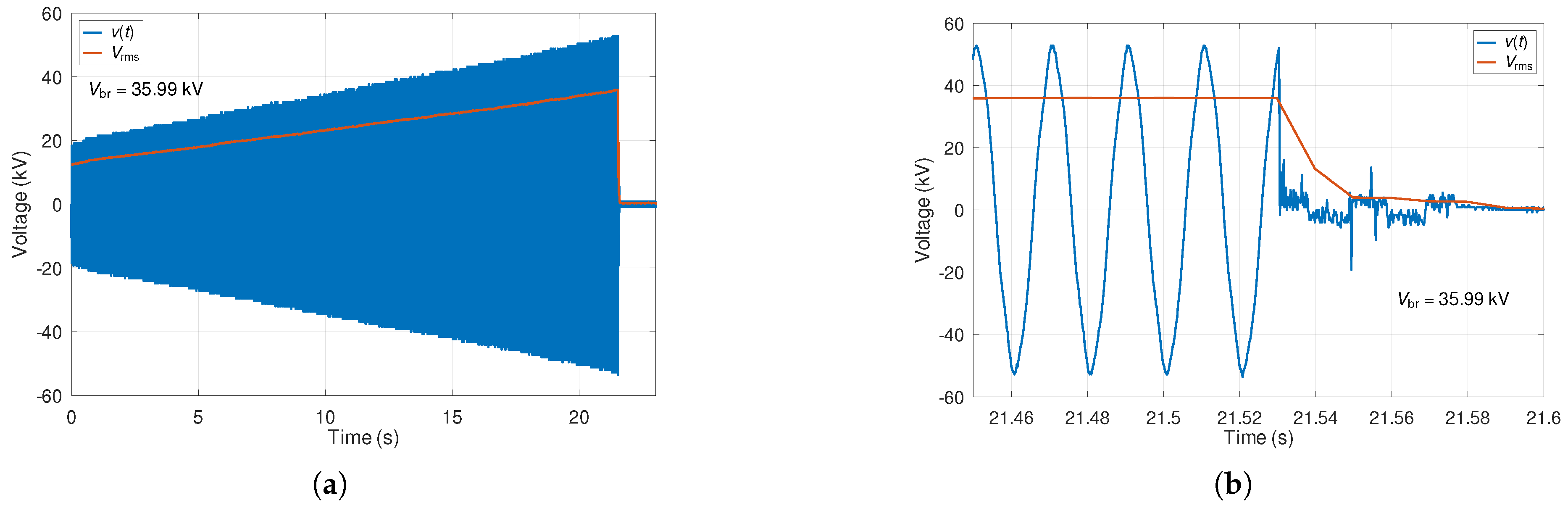

To determine the breakdown voltage of the samples, we used a script in the scientific programming language GNU Octave version 8.0.0 on the Ubuntu 20.04 LTS operating system. The script read all CSV records sequentially and, using a numerical method, calculated the root-mean-square (RMS) voltage in each half-cycle of the applied voltage. At the same time, the script generated two graphs for each sample. The first graph shows a time record of the instantaneous applied voltage and the calculated RMS voltage for each half-cycle. At the same time, the script writes the breakdown voltage value to the first image. The second graph is an enlargement of the moment of the sample breakdown and helps check the total breakdown.

Figure 2 shows an example of graphs generated by the script.

To evaluate the electrical breakdowns of the samples, we used the Weibull distribution, which was implemented using a custom-written script in Python 3. The Weibull distribution is the most common for solid insulation because of its wide applicability. The above distribution can be described by two parameters, similar to the normal distribution described by the mean and standard deviation [

36].

The adequacy of the selected Weibull distribution representing the distribution data set can be verified by plotting the data points on a special probability plot. If there is a good fit to the distribution, the result will be a straight line plot. The cumulative density function for the two-parameter Weibull distribution describes Equation

1

where

V is the measured variable, in our case it is breakdown voltage,

is the probability of failure (breakdown) at a voltage less than or equal to

V,

is the scale parameter and is positive, and

is the shape parameter and is positive. The failure probability

is zero at

(

V represents the applied voltage). In our case, the failure probability of the electrical breakdown of the sample increases continuously with increasing

V. Then, with increasing voltage, the failure probability approaches certainty, i.e.,

. The scale parameter

represents the voltage for which the probability of failure is 0.632 based on

, where e is Euler’s number. It is analogous to the mean of a Normal distribution. The units of

are the same as

V. The shape parameter

is a measure of the range of breakdown voltages. The larger the

, the smaller the range of breakdown voltages. It is analogous to the inverse of the standard deviation of the Normal distribution [

33].

The correlation coefficient for testing the adequacy of the Weibull distribution is calculated using the formula given in the IEC 62539, namely:

with the following transformations:

The correlation coefficient r is then determined using the least squares regression method, i.e., the Pearson correlation coefficient between

and

. To determine whether the data points fit well with a two-parameter Weibull distribution, we used the procedure outlined in the [

33] standard. The original data presented in the study, as well as the scripts used for data processing, are publicly available in [

37].

3. Results and Discussion

The breakdown performance of the epoxy composites was evaluated under AC voltage stress, and the statistical analysis of failure data was performed using Weibull distribution fitting implemented in Python. The parameters (characteristic breakdown voltage) and (shape factor) were determined for all tested configurations, providing a quantitative measure of dielectric endurance and data dispersion.

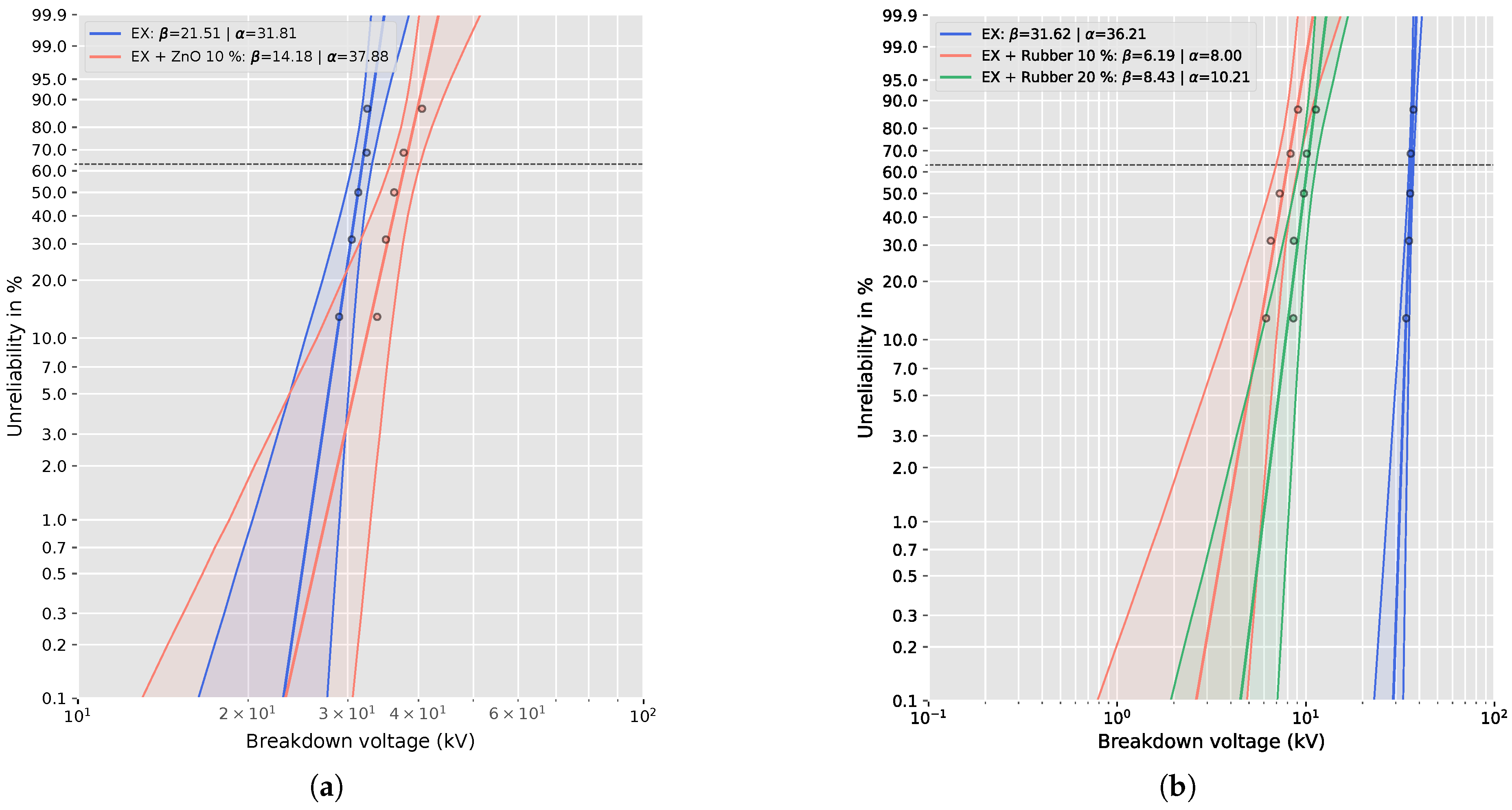

Figure 3 presents the Weibull probability plots for the breakdown voltage of the epoxy composites with and without recycled fillers. The slope of each line corresponds to the shape parameter (

), while the intercept provides the characteristic breakdown voltage (

) at 63.2% cumulative failure probability.

The pure epoxy samples exhibit a steep slope (

= 21.51 and

= 31.62), indicating high uniformity of breakdown events and stable dielectric properties. Incorporation of 10 wt% ZnO filler (in

Figure 3 marked as Ex + ZnO 10 %) slightly reduced the slope (

= 14.18), implying increased data scatter, but the higher

value (37.88 kV) confirms improved dielectric endurance.

In contrast, rubber-filled composites show significantly flatter slopes (

= 6.19 for 10 wt% and 8.43 for 20 wt%), suggesting non-uniform electric field distribution and premature failure initiation at filler-matrix interfaces. These findings are consistent with the observed 4.53 times and 3.55 times reductions in breakdown voltage compared to pure epoxy, confirming the detrimental influence of elastomeric inclusions on the electrical integrity of the insulation system. In

Figure 3, the dashed line represents the percentage value of the scale parameter for which the probability of failure is 63.2%.

Table 2 summarizes the obtained Weibull parameters, along with the relative change in characteristic breakdown voltage (

) compared to the reference epoxy sample. For samples containing ZnO filler (0.7 mm thickness), the incorporation of 10 wt% ZnO led to an increase in

from 31.81 kV to 37.88 kV, representing a 19% enhancement in breakdown voltage. This improvement is attributed to the interfacial polarization and space-charge trapping effects at the epoxy-ZnO boundary, which contribute to delayed streamer propagation and energy dissipation under high electric stress [

38].

In contrast, the addition of waste tire rubber particles (0.9 mm samples) significantly reduced the breakdown performance. The

parameter decreased from 36.21 kV for the reference epoxy to 8.00 kV and 10.21 kV for 10 wt% and 20 wt% rubber-filled samples, respectively, corresponding to a 4.53-fold and 3.55-fold reduction. This pronounced decline is linked to the increased interfacial void density, dielectric mismatch between the rubber inclusions and epoxy matrix, and localized field enhancement at the particle boundaries [

39]. We believe another reason for the decrease in breakdown voltage is the size of the prepared fraction, which is below 1 mm. It is likely that at a sample thickness of 0.9 mm, a significant part was filled with tire rubber. Assuming that the electrical strength of tire rubber is less than the electrical strength of epoxy, there could be a substantial weakening of the electrical strength of the prepared composite. The

parameter also decreased notably for the 10 wt% rubber composite (

), indicating higher statistical scatter and reduced homogeneity of the breakdown process. The dielectric strength given in

Table 2 is calculated as the quotient of the breakdown voltage (

) and the distance between the electrodes (sample thickness), over which the voltage is applied. All correlation coefficients in

Table 2 exceed the critical correlation coefficient, which for five samples is approximately

. This result indicates a good agreement with the two-parameter Weibull distribution [

33]. Hence, the data points can be regarded as well described by this distribution.

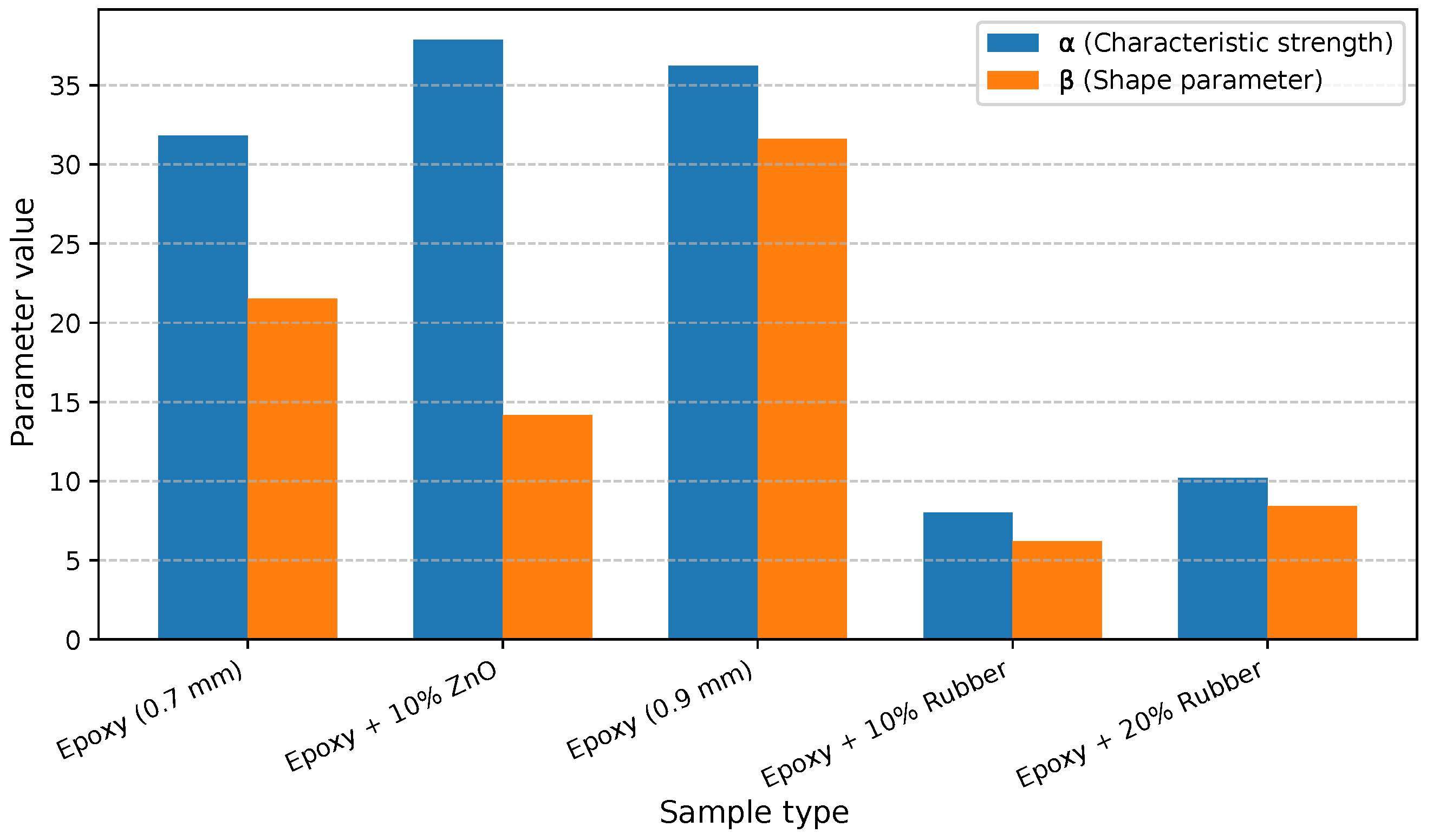

To provide a clearer comparison of the dielectric performance across all materials,

Figure 4 illustrates the characteristic breakdown voltage (

) and shape parameter (

) for the pure epoxy and composites with 10 wt% ZnO and waste tire rubber fillers.

The bar chart emphasizes the enhancement of by approximately 19% for the ZnO-filled sample, which also retains a reasonably high value (14.18), confirming improved breakdown resistance with moderate variability. In contrast, both rubber-filled systems display substantial degradation of dielectric strength – decreases by factors of 4.53× and 3.55× for 10 wt% and 20 wt% tire rubber, respectively. The reduction in (to 6.19 for the 10 wt% sample) further reflects higher dispersion in the failure data, indicating localized weaknesses caused by poor interfacial adhesion and dielectric inhomogeneity.

These results demonstrate that ZnO waste from electric arc furnaces can act as a beneficial filler for epoxy insulation, reinforcing its high-voltage withstand capability. On the contrary, rubber waste, despite being environmentally attractive, introduces structural discontinuities that negatively influence the electric field distribution and breakdown pathways. Future optimization of filler dispersion and surface treatment could mitigate these effects, enabling broader applicability of recycled materials in high-voltage insulation systems.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the potential of using recycled ZnO powder recovered from electric arc furnace dust and waste tire rubber particles as fillers in epoxy-based insulation materials for high-voltage applications. We analyzed the breakdown voltage behavior of epoxy composites containing 10 wt% ZnO and rubber contents of 10 wt% and 20 wt%, and compared these results with pure epoxy. Breakdown testing, performed with VDE electrodes under controlled laboratory conditions, used the two-parameter Weibull distribution for statistical analysis, as recommended by IEC 62539.

The epoxy composite filled with 10 wt% recycled ZnO exhibited a 19 % increase in breakdown voltage compared with pure epoxy. The Weibull scale parameter increased from 31.81 kV for pure epoxy to 37.88 kV for the ZnO-filled composite, indicating enhanced dielectric strength. Although the shape parameter decreased slightly from 21.51 to 14.18, suggesting greater variability in breakdown events, the overall improvement in electric strength confirms the beneficial effect of the recycled ZnO filler. We assume that the observed enhancement arises from the high purity of the recovered ZnO (96.3 wt %), which promotes interfacial polarization and charge trapping within the epoxy matrix.

In contrast, the incorporation of waste tire rubber particles led to a gradual reduction in breakdown voltage. The parameters for composites with 10 wt% and 20 wt% rubber were 8 kV and 10.21 kV, respectively – corresponding to 4.53-fold and 3.55-fold decreases compared with pure epoxy. The lower shape parameters () indicate larger statistical dispersion and unstable dielectric behavior. The reduction in dielectric strength likely results from interfacial defects, carbon residues, and non-polar rubber domains that disrupt the uniformity of the electric field and facilitate early breakdown initiation.

Future research will focus on several key directions. Hybrid filler systems combining recycled ZnO with small proportions of rubber could be explored to balance mechanical flexibility and electrical performance. Additionally, finite-element simulations of local electric field distributions within heterogeneous composites could provide deeper insights into breakdown initiation mechanisms. Finally, long-term aging should be performed to assess the durability and reliability of the recycled-filler epoxy composites in practical high-voltage applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D. and P.L.; methodology, B.D. and V.M.; software, B.D. and J.K.; validation, B.D. and P.L.; formal analysis, B.D. and D.O.; investigation, B.D., V.M. and J.K.; resources, B.D., V.M. and J.K.; data curation, B.D. and P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.D.; writing—review and editing, B.D., V.M., D.O., and P.L.; visualization, B.D. and J.K.; supervision, B.D. and P.L.; project administration, D.O. and P.L.; funding acquisition, D.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth grant number VEGA 1-0380-24, VEGA 1/0259/26, and VEGA 1/0268/26; the Slovak Research and Development Agency grant number APVV-22-0115 and APVV-23-0051; the Cultural and Educational Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic grant number 008TUKE-4/2019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results were conducted by the authors. The original data presented in the study, as well as the scripts used for data processing, are publicly available in Mendeley at

https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/4cb6rdm4w9/1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ing. Ľuboš Šárpataky PhD. for help and assistance in measuring the breakdown voltage on epoxy composite materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

alternating current |

| CSV |

comma-separated values |

| CNC |

computer numerical control |

| EAF |

electric arc furnace |

| Elem. |

element |

| FCS |

four channels scope |

| GNU |

GNU’s Not Unix! |

| HVD |

high-voltage divider |

| HVT |

high-voltage transformer |

| IEC |

International Electrotechnical Commission |

| LCA |

life-cycle assessment |

| LTS |

long-term support |

| RMS |

root-mean-square |

| ST |

setting transformer |

| TC |

test cell |

| ZnO |

zinc oxide |

| XRF |

X-ray fluorescence |

References

- Xiao, Y.; Goyal, G.K.; Su, J.; Abbasi, H.; Yan, H.; Yao, X.; Tantratian, K.; Yan, Z.; Alksninis, A.; Phipps, M.; et al. A comprehensive review of electric vehicle recycling: Processes in selective collection, element extraction, and component regeneration. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2025, 219, 108309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laftah, W.A.; Rahman, W.A.W.A. A comprehensive review of tire recycling technologies and applications. Materials Advances 2025, 6, 4992–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, J.; Marques, T.; Mateus, A.; Carreira, P.; Malça, C. An Additive Manufacturing Solution to Produce Big Green Parts from Tires and Recycled Plastics. Procedia Manufacturing 2017, 12, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Park, J.; Lee, D.; Chun, B.; Banthia, N.; Yoo, D.Y. Beneficial effect of recycled tire powder incorporation on the tensile performance of strain-hardening alkali-activated concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2025, 464, 140115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calignano, F.; Bove, A.; Mercurio, V.; Marchiandi, G. Effect of recycled powder and gear profile into the functionality of additive manufacturing polymer gears. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2023, 30, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussi, N.; Ammar, M.; Mokni, A.; Mhiri, H. Efficiency of a recycled composite material for building insulation. Construction and Building Materials 2025, 467, 140358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zou, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhou, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y. Efficient recycling of anhydride-cured epoxy resins for electrical insulation: Green economy and tunable performance. Polymer Testing 2025, 150, 108934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourou, C.; Bonoli, A.; Zamorano, M.; Martín-Morales, M. Environmental impact of roof tiles using recycled waste glass coatings: A Life Cycle Assessment approach. Building and Environment 2025, 270, 112481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcoceba-Pascual, S.; Ortego, A.; Villanueva-Martínez, N.I.; Schaik, A.v.; Reuter, M.A.; Iglesias-Émbil, M.; Valero, A. Evaluating the recyclability of electronic car parts through disassemblability, thermodynamic and metallurgical analyses. Journal of Cleaner Production 2025, 513, 145725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Liao, Q.; Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, F.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C. Foaming process and thermal insulation properties of foamed glass-ceramics prepared by recycling muti-solid wastes. Construction and Building Materials 2025, 466, 140270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, P.A.M.; Lima, F.A.; Medeiros, G.B.; Mata, G.C.; Tanabe, E.H.; Bertuol, D.A.; Oliveira, W.P.; Guerra, V.G.; Aguiar, M.L. From waste to innovation: Advancing the circular economy with nanofibers using recycled polymers and natural polymers from renewable or waste residues. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2025, 147, 56–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Cai, Y.; Huang, J.; She, M.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Xiong, S. High-performance polyarylate nanofiber membranes with ultra-thin structure, multi-environmental tolerance, and recyclability for advanced electrical insulation. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 518, 164782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gan, Y.; Peng, C.; Gao, C.; Yu, J.; Zhang, X. Hot-press recycling of epoxy insulating materials: Mechanistic insights into network reconfiguration and performance evolution modulated by processing conditions. Polymer 2025, 337, 128965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isayev, A.I. Chapter 15 - Recycling of Rubbers. In The Science and Technology of Rubber (Fourth Edition), Fourth Edition ed.; Mark, J.E., Erman, B., Roland, C.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, 2013; pp. 697–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, R.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, C. Ion liquid selective depolymerization of epoxy resin insulation materials from electric power industry in a polar aprotic solvent system. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2025, 216, 106456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, G.V.; Syrodoy, S.V.; Purin, M.V.; Zenkov, A.V.; Gvozdyakov, D.V.; Larionov, K.B. Justification of the possibility of car tires recycling as part of coal-water composites. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2021, 9, 104741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sun, B.; Yang, L.; Wang, W. Mechanical and thermal properties of recycled coarse aggregate concrete incorporating microencapsulated phase change materials and recycled tire rubber granules and its freeze-thaw resistance. Journal of Building Engineering 2025, 101, 111821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Villaverde, A.; Sóñora, S.; Dagnac, T.; Roca, E.; Llompart, M. Metal and metalloid content in real urban synthetic surfaces made of recycled tire crumb rubber including playgrounds and football fields. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 975, 179267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yue, D.; Belko, V.O.; Maksimenko, S.A.; Deng, J.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Z.; Fu, Q.; Liu, B.; et al. Recent progress in degradation and recycling of epoxy resin. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024, 32, 2891–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zeng, S.; Chu, J.; Bi, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. Recycling of epoxy polymer and enhancement of breakdown strength after reconstruction via alcoholysis. Polymer 2025, 334, 128712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjana, E.I.; Aiswariya, K.; Prathish, K.P.; Sahoo, S.K.; Jayasankar, K. Recovery and recycling of silica fabric from waste printed circuit boards to develop epoxy composite for electrical and thermal insulation applications. Waste Management 2025, 198, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Dang, B.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, Q.; Hu, J.; He, J. Polypropylene-based ternary nanocomposites for recyclable high-voltage direct-current cable insulation. Composites Science and Technology 2018, 165, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reghunadhan, A.; Datta, J.; Jaroszewski, M.; Kalarikkal, N.; Thomas, S. Polyurethane glycolysate from industrial waste recycling to develop low dielectric constant, thermally stable materials suitable for the electronics. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2020, 13, 2110–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Wang, L.; Teng, J.; Liu, G. Strategies and technologies for sustainable plastic waste treatment and recycling. Environmental Functional Materials 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magbool, H.M. Recycling electronic waste as fiber reinforcement in high-strength concrete: A sustainable approach. Developments in the Built Environment 2025, 24, 100755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Li, Q.; Song, G.; Hu, Y. The synergistic effect of recycled steel fibers and rubber aggregates from waste tires on the basic properties, drying shrinkage, and pore structures of cement concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2025, 470, 140574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Rashid, A.A.; Polat, R.; Koç, M. Potential and challenges of recycled polymer plastics and natural waste materials for additive manufacturing. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2024, 41, e01103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tsang, H.H.; Cheng, Y. Shaking table tests on geotechnical seismic isolation of electrical transformers using recycled tire rubber-soil mixtures. Construction and Building Materials 2025, 497, 143886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, O.; Clemente, C.; Alonso, M.; Alguacil, F.J. Recycling of an electric arc furnace flue dust to obtain high grade ZnO. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2007, 141, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.A.d.; Schalch, V. Recycling of electric arc furnace (EAF) dust for use in steel making process. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2014, 3, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liptai, P.; Nagy, Š.; Dolník, B.; Matvija, M.; Pirošková, J. Optimization of technological processes in the manufacturability of varistors based on recycled ZnO product, with emphasis on environmental sustainability. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Groves, D.I.; Zhang, L. Towards a circular economy: Modern recycling technologies for critical metals. Gondwana Research 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 62539(E):2007. Guide for the statistical analysis of electrical insulation breakdown data. Standard IEC 62539:2007, International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva, CH, 2007.

- IEC 60243-1:2013. Electric strength of insulating materials – Test methods – Part 1: Tests at power frequencies. Standard IEC 60243-1:2013, International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva, CH, 2013.

- ASTM D1816-12R19. Standard Test Method for Dielectric Breakdown Voltage of Insulating Oils of Petroleum Origin Using VDE Electrodes. Standard ASTM D1816-12R19, Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, Piscataway, NJ 08855, USA, 2012.

- Cheon, C.; Seo, D.; Kim, M. Statistical Analysis of AC Breakdown Performance of Epoxy/Al2O3 Micro-Composites for High-Voltage Applications. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolník, B. Eco-Functional Epoxy Composites from Recycled ZnO and Tire Rubber: A Study on Breakdown Voltage Enhancement, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.X.; Luo, L.Y.; Li, M.T.; Xu, X.K.; Ren, J.R. Robust high-surface-insulating and superhydrophobic materials by constructing nanoparticles decorated porous structures. Composites Science and Technology 2025, 261, 111033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, X.; Hu, B.; Ji, Z.; Gao, C.; Zhou, F.; Yu, J.; Du, B.; Zhao, Y. Enhancing electrical insulation of epoxy composites by suppressing charge injection and subsequently electric field distortion. Composites Communications 2025, 56, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).