1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) has revolutionized remote monitoring and control of systems by enabling the processing of real-time data from numerous sensing devices. Cisco estimated that approximately 21.3 billion IoT devices were deployed in 2022. Intelligent interfaces allow these devices to interact, collect, communicate, and store data efficiently. A trusted ecosystem built on the principles of authentication, authorization, privacy, confidentiality, availability, and integrity is therefore essential to ensure secure data transactions [

2,

3]. IoT devices are often constrained by limited storage, processing, sensing, and computational resources [

4]. Moreover, the diversity of devices from multiple vendors or manufacturers deployed within IoT networks makes them particularly vulnerable to security threats, with device authentication emerging as a critical factor in maintaining trustworthy communication. Authenticating edge devices is as important as authenticating users to ensure that only legitimate devices gain access to IoT resources. Weakly secured devices can compromise the entire system, leading to severe financial and reputational consequences. The heterogeneous nature of IoT networks, combined with the resource limitations of edge devices, makes traditional authentication schemes impractical. These constraints underscore the need for innovative, lightweight authentication mechanisms tailored specifically to IoT environments [

5].

IoT devices operating at the network edge remain highly vulnerable to cyber threats, including data breaches, hardware tampering, and denial-of-service attacks. Traditional cloud-based, centrally managed infrastructures often struggle to counter advanced risks, including Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, Man in the Middle (MiTM) intrusions, eavesdropping, and attacks powered by artificial intelligence [

6]. To mitigate these risks more effectively, computational capabilities can be shifted closer to the network edge, enabling real-time threat detection and mitigation directly on devices rather than relying solely on remote cloud infrastructure. Cloud-assisted IoT takes advantage of the large storage capacity and powerful computing resources available in cloud platforms to process and analyze data coming from IoT devices. However, when enormous amounts of data are continuously sent from widely distributed IoT nodes, cloud servers experience processing delays, which leads to higher latency and slower response times for the services delivered to network users.

Edge Computing (EC) enables local processing and storage of sensitive data, thereby preserving privacy and facilitating faster access to critical information during security investigations [

7]. In addition, EC offers advantages such as reduced latency, improved bandwidth efficiency, and enhanced privacy and security [

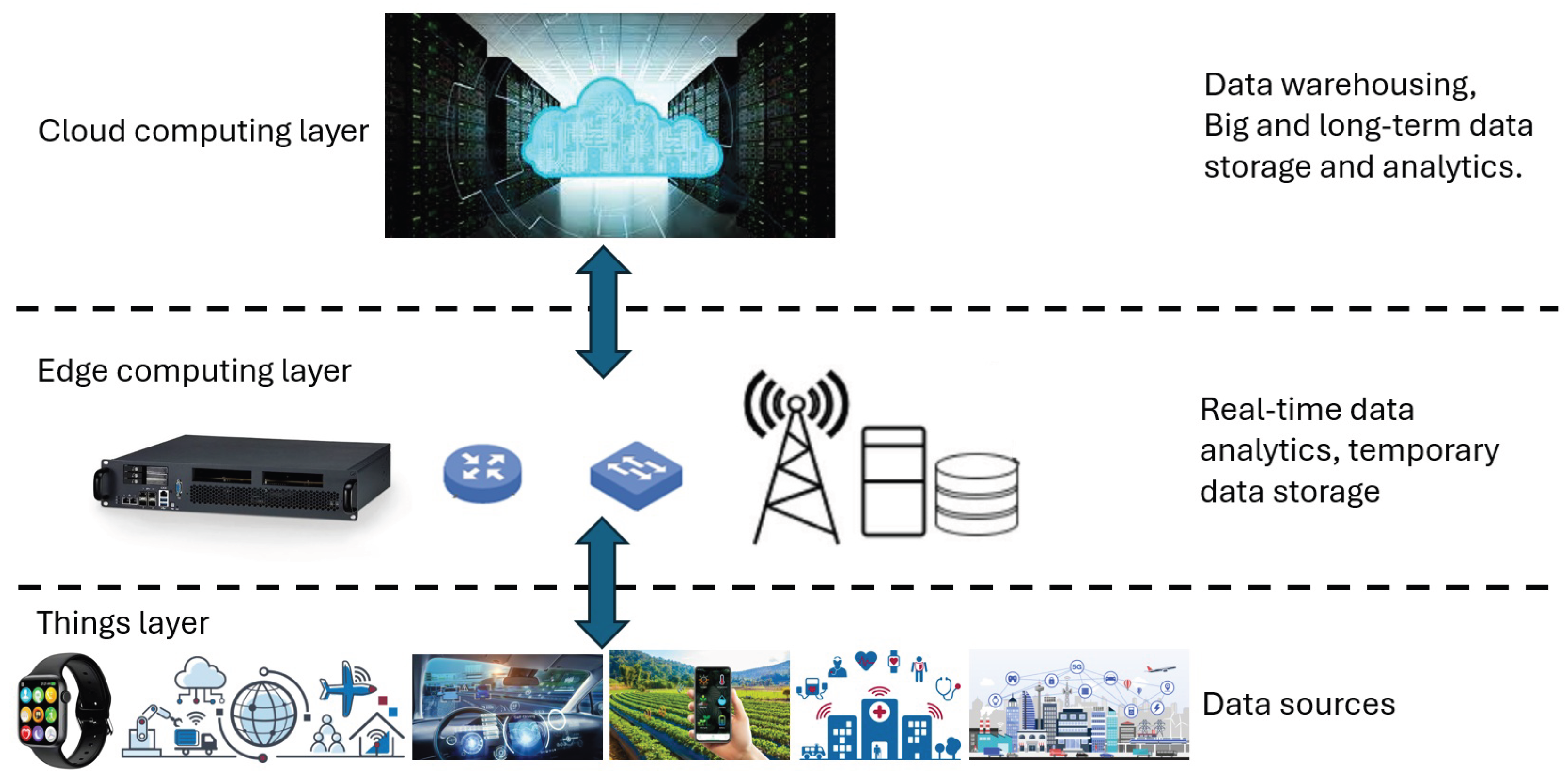

8]. The EC architecture, shown in

Figure 1, is typically organized into three layers: the edge devices layer, the edge nodes or gateways layer, and the cloud. Edge devices, such as IoT sensors, smartphones, cameras, or industrial machines, are primarily responsible for generating or collecting data. Due to limited processing capabilities, these devices usually perform only basic functions such as data filtering or preliminary processing. At the edge node layer, intermediate devices like routers, edge servers, or micro data centers perform more advanced processing, aggregate data that is further complicated by device heterogeneity and resource limitations, the cloud. The cloud layer, in turn, handles complex computations, long-term data storage, and advanced analytics that exceed the capabilities of edge nodes. Connectivity among edge devices, edge nodes, and the cloud is supported by WiFi, 5G, or wired infrastructure to ensure efficient data transmission. Edge-driven IoT systems distribute heterogeneous resources across the network to achieve flexibility and scalability, supporting applications such as smart cities and autonomous vehicles. However, edge servers and devices remain constrained by limited power and processing capacity, and offloading large volumes of data and tasks can overload the network.

1.1. Motivations

The integration of EC with IoT introduces challenges due to their inherent differences. IoT systems encompass a diverse range of hardware platforms and communication protocols, and their success depends on a unified framework that ensures seamless interoperability between IoT devices and edge nodes. Security and privacy remain primary concerns, complicated further by device heterogeneity and resource limitations such as memory and battery power [

9]. As a result, edge devices and servers are highly vulnerable to attacks, and a breach at any point can compromise the entire network. To address these risks, lightweight and robust security mechanisms tailored to the distributed and heterogeneous nature of IoT systems are essential. Several strategies have been proposed to mitigate security challenges in EC. Conventional measures include intrusion detection systems (IDS) to monitor malicious activity, strong access control to regulate permissions, encryption to protect data at rest and in transit, and authentication mechanisms to verify user and device identities. Beyond these methods, advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are increasingly used for real-time anomaly detection and adaptive defense against evolving threats [

10]. Blockchain utilizes machine learning methods to learn and replicate the behavior of a PUF with high accuracy, thereby undermining sharing, and ensuring transaction integrity [

11,

12]. In parallel, Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) have garnered attention as hardware-based security primitives that provide device authentication, secure key generation, and cryptographic support. PUFs exploit manufacturing variations to generate unique device-specific identifiers that safeguard against cloning and other hardware-based attacks. Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), known for their flexibility, reconfigurability, and rapid prototyping, are well-suited for implementing PUFs [

13]. Moreover, PUFs can be integrated with intellectual property (IP) cores in FPGA-based systems, making them practical for real-world deployments [

14,

15].

Meanwhile, ML techniques such as Support Vector Machines, Logistic Regression, and Deep Neural Networks are increasingly used in hardware security to detect hardware Trojans, identify counterfeit integrated circuits (ICs), and evaluate the reliability of PUF [

16]. At the edge, ML models are also applied to analyze data streams and detect anomalies, intrusions, and malicious activities in real time. However, ML models deployed on resource-constrained edge devices are themselves vulnerable to adversarial threats, including poisoning attacks that corrupt training data, evasion attacks that deceive models with crafted inputs, inference attacks that extract sensitive information, and exploratory attacks that exploit model weaknesses or replicate behavior. ML-based modeling attacks use machine learning methods to learn and reproduce the behavior of a PUF with very high accuracy, which can undermine its security. An adversary can construct a numerical model of the PUF by obtaining a portion of its challenge response pairs through eavesdropping or any other form of unauthorized access [

18]. These risks are exacerbated by the limited storage and computational capabilities of edge devices. To mitigate such vulnerabilities, integrating FPGA-based PUFs with ML frameworks offers a promising approach to strengthening edge security [

17]. PUF-derived keys can be employed to encrypt ML models or authenticate devices contributing training data, protecting against tampering and data leakage. Leveraging FPGAs for PUF design provides flexibility, rapid prototyping, and reconfigurability, while seamless integration with other IP cores enables robust and scalable security solutions [

19].

1.2. Research Contributions

This research presents a comprehensive investigation into the design, implementation, and security evaluation of a Ring Oscillator Physical Unclonable Function (RO PUF) on an FPGA, with emphasis on machine learning (ML)-based modeling, resistance, and statistical randomness analysis. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

FPGA-Based Design and Implementation of RO PUF: The study successfully implemented a configurable RO PUF architecture on an FPGA platform. A dedicated testbench was developed to acquire large-scale challenge–response datasets under controlled operating conditions, verifying the reproducibility and uniqueness of the PUF behavior across multiple FPGA instances.

Comprehensive Evaluation of PUF Metrics: The implemented RO PUF was analyzed using standard performance metrics such as uniformity, uniqueness, and reliability (intra-Hamming distance). The proposed design demonstrated balanced uniformity near the ideal 50%

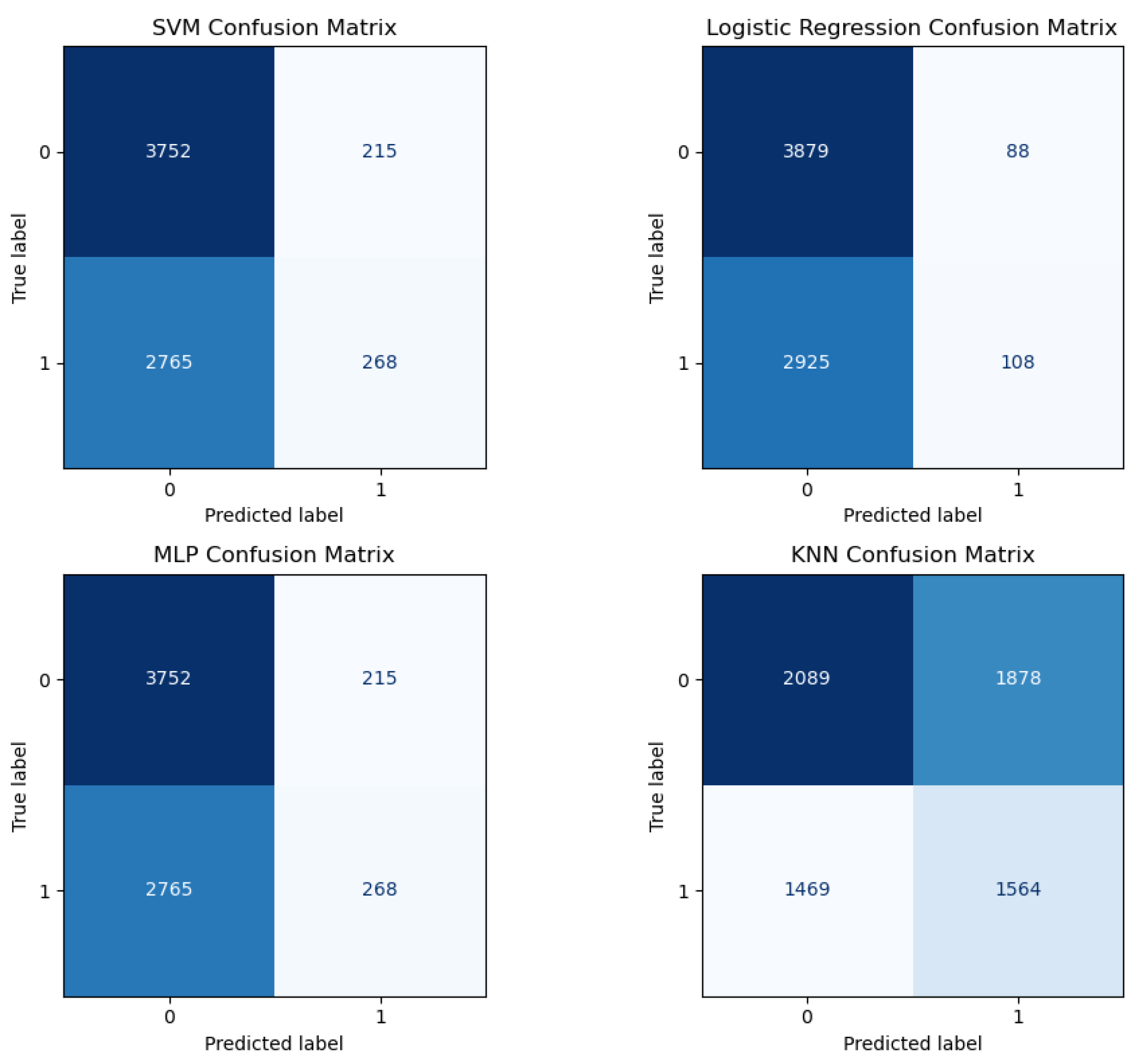

Machine Learning-Based Attack and Accuracy Estimation: To assess the resilience of the proposed RO PUF against modeling attacks, various ML algorithms, including Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), were employed. Confusion matrix analysis revealed that linear models, such as LR, failed to capture the nonlinear challenge–response relationship, while nonlinear models (SVM, MLP, and KNN) performed moderately better but exhibited trade-offs between precision and recall. The findings confirmed that none of the models achieved strong predictive accuracy, highlighting the robustness and unpredictability of the proposed RO PUF against ML-based cloning attempts.

Randomness Validation Using NIST SP 800-22 Tests: The randomness quality of the generated CRP responses was validated using the NIST statistical test suite, covering tests such as frequency, runs, block frequency, and cumulative sums. The majority of the tests yielded p-values greater than 0.01, confirming that the PUF outputs exhibit strong statistical randomness and are suitable for cryptographic and authentication applications.

2. Related Works

Shen et al. proposed an integrated security framework for EC that combines ML and cryptographic techniques to monitor and detect abnormal activities on the network. The study provides valuable insights into the use of Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models for time series prediction, evaluated using performance metrics such as Precision, Recall, and F1-Score [

20]. In the Collaborative Edge Computing (CEC) model, the edge layer handles data storage and processing in a distributed manner. Given the limited processing capacity of individual edge devices, they cooperate to offload tasks among themselves, a process known as load balancing. The researchers in [

21] employed Physically Unclonable Functions (PUFs) to authenticate edge devices during load balancing, eliminating the need to store a database of Challenge-Response Pairs (CRPs) locally. Cheng et al. integrated blockchain technology with certificateless cryptography, elliptic curve cryptography, and pseudonym-based cryptography to enable mutual authentication between edge servers and IoT devices [

22]. The study in [

23] proposes a privacy-preserving edge computing approach that utilizes federated learning to train a unified deep learning model across multiple end users collaboratively. Instead of sharing raw data, only model parameters (i.e., gradients) are exchanged. The parameters from local deep learning models on various edge nodes are aggregated at the edge and then distributed to all participants. Through several iterations of local training and parameter aggregation, a deep learning model is developed that preserves user privacy without the need to share raw data. Zhang and colleagues introduced a configurable tristate PUF that can operate as an arbiter PUF, a ring oscillator PUF, or a bistable ring PUF. The design uses a bitwise XOR-based obfuscation mechanism to hide the relationship between challenges and responses. As a result, machine learning models fail to build an accurate prediction model, with all attack accuracies remaining around 50% to 60%, which is effectively the same as random guessing [

24]. The authors of [

25] introduced an authentication method that employs arbiter PUFs together with three protection strategies called challenge splitting, challenge scrambling, and challenge padding. Each strategy disrupts the structure or visibility of the challenge so that machine learning models cannot form an accurate numerical model of the PUF. In [

26], a hybrid secure deduplication scheme is introduced that ensures data privacy on the server side while enhancing network performance on the client side. Additionally, an additive homomorphic encryption method is proposed to enable efficient deduplication operations on resource-constrained edge nodes. Intrusion detection systems (IDS) are vital for the security of IoT systems, as they detect traces of known attacks and unusual behavior in IoT devices and their connecting networks [

27]. However, the majority of IDS algorithms use conventional encryption and cryptographic techniques. Unfortunately, these approaches are vulnerable to physical attacks, as they primarily rely on storing secret keys in the device’s local memory. Blockchain is considered an ideal approach to store the huge amount of data generated by IoT devices with utmost privacy and security using a distributed ledger. However, the resource-constrained IoT devices can’t meet the computational requirements of data mining in blockchain networks. Sarkar et. al. have proposed a robust PUF-based authentication system to replace the popular consensus algorithms [

28].

A PUF design based on Generalized Galois Ring Oscillators (GenGARO) has been implemented on Artix-7 FPGAs using both 11-LUT and 3-LUT configurations. The proposed design demonstrates strong resilience against various ML models, including Decision Trees (DT), Random Forests (RF), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP) [

29]. Another approach, the Structure-Obfuscated PUF (SO-PUF), is built on a configurable ring oscillator (CRO) framework and dynamically removes NOT gates at each stage based on the challenge input. As reported in [

30], SO-PUF was implemented on an Xilinx Spartan-6 FPGA and achieved near-random prediction accuracy. Kareem et al. [

31] investigated the vulnerability of three RO-PUF designs to ML attacks and evaluated their prediction accuracy using models such as DT, RF, KNN, and SVM. Abulibdeh et al. introduced the Algorithmically Optimized Configurable Ring Oscillator PUF (AOCRO), which demonstrated strong resistance to machine learning modeling attacks. In their evaluation, five different ML algorithms (SVM, MLP, LR, CNN, and CMA ES) were trained on a dataset of one million challenge response pairs (CRPs), achieving an average prediction accuracy of 61.3%, indicating enhanced robustness compared to conventional CRO PUF designs [

32]. Jack Miskelly et al. investigated the impact of ML attacks on Configurable RO PUFs. The study simulated 128-bit CRO PUFs and multi-PUF variants with datasets ranging from 1,000 to 10,000 CRPs. The results showed that conventional CRO PUFs could be accurately modeled using an LR, ML model, achieving prediction accuracies exceeding 98–99% [

33]. Laguduva et al. proposed a non-invasive, architecture-independent attack on PUFs using challenge response pairs (CRPs). This method achieved a cloning accuracy of 93.5% without requiring any prior knowledge of the PUF’s internal architecture [

34]. A summary of the results obtained by above mentioned researchers is shown in

Table 1.

3. Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFS)

Researchers have identified PUFs as robust security primitives that can guarantee the three pillars of security, namely confidentiality, authenticity, and privacy, of IoT data. PUFs extract unique information from the physical characteristics of the IoT device [

37]. PUF-based authentication protocols enhance the security of resource-constrained edge devices without requiring them to store credentials in their limited non-volatile memory. Physically Unclonable Functions (PUFs) utilize the inherent random variations introduced during manufacturing to generate secret keys dynamically. They provide essential security functions such as authentication and secret key generation, especially in resource-constrained environments like the Internet of Things (IoT) [

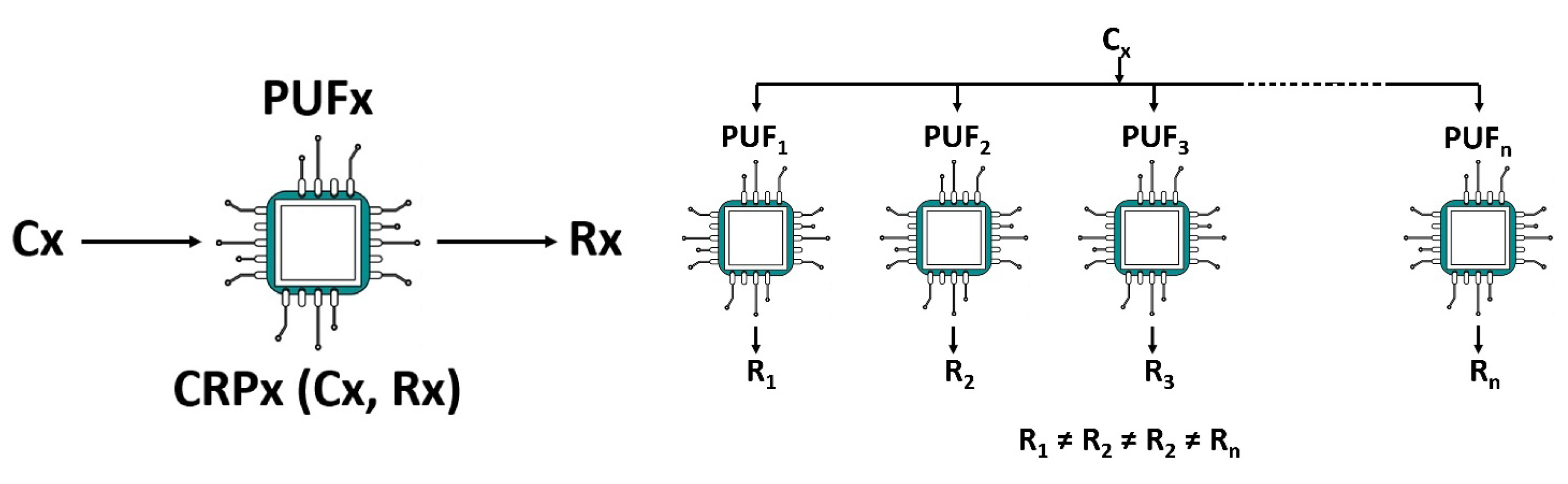

38]. The inherent unclonability of PUFs stems from numerous uncontrollable random parameters created during fabrication. When a PUF receives an input, known as a challenge (C), it produces a corresponding output response (R).

Figure 2 illustrates that physical variations in the fabrication of integrated circuits (ICs) can result in two ICs yielding different responses to the same challenge. This relationship between the input and output is referred to as a challenge–response pair (CRP) [

39]. Traditional authentication methods rely on storing secret credentials in a device’s memory, which makes them unsuitable for physically unprotected IoT devices. Attackers can exploit physical vulnerabilities to compromise the entire system. PUFs mitigate such risks in two key ways: first, they generate volatile secrets that are not stored in digital memory but are intrinsically embedded in the hardware structure; second, the uniqueness of each PUF enables it to serve as a unique identifier for individual IoT devices [

54].

3.1. PUFs Classification

PUFs can be placed into two groups based on the number of CRPs they can generate, i.e., strong and weak. The limited number of CRPs in a weak PUF are typically proportional to the number of components used in its construction. In contrast, strong PUFs provide a vast number of CRPs, making polynomial-time attacks computationally impractical [

56]. Strong PUFs are typically employed in authentication and key establishment protocols, whereas weak PUFs are mainly used for identification and secure key storage applications [

57]. Examples of strong PUFs include the Arbiter PUF, the XOR Arbiter PUF, and the Lightweight PUF. In contrast, weak PUFs are represented by designs such as the SRAM PUF, Ring Oscillator (RO) PUF, Anderson PUF, Memristor PUF, Thyristor PUF, and One-Time Programmable (OTP) PUF [

58]. Additionally, PUFs are silicon-based and non-silicon PUFs, depending on the manufacturing process adopted. Silicon PUFs count on fabrication mismatches inherent in integrated circuits and can be further divided into delay-based PUFs and memory-based PUFs. In contrast, non-silicon PUFs are based on physical irregularities in systems composed of non-electronic components. Memory-based PUFs utilizes the initial binary states of memory upon power-up, whereas delay-based PUFs exploit variations in signal propagation delays within circuits.

3.2. RO PUFs

Due to inherent random variations in the manufacturing process, two similar ROs do not generate identical oscillation frequencies. The frequency differences between selected RO pairs form the output response of the PUF. An RO PUF consists of an odd number of NOT logic gates arranged in a ring, causing the output to oscillate between logic ‘1’ and ‘0’ at a specific frequency [

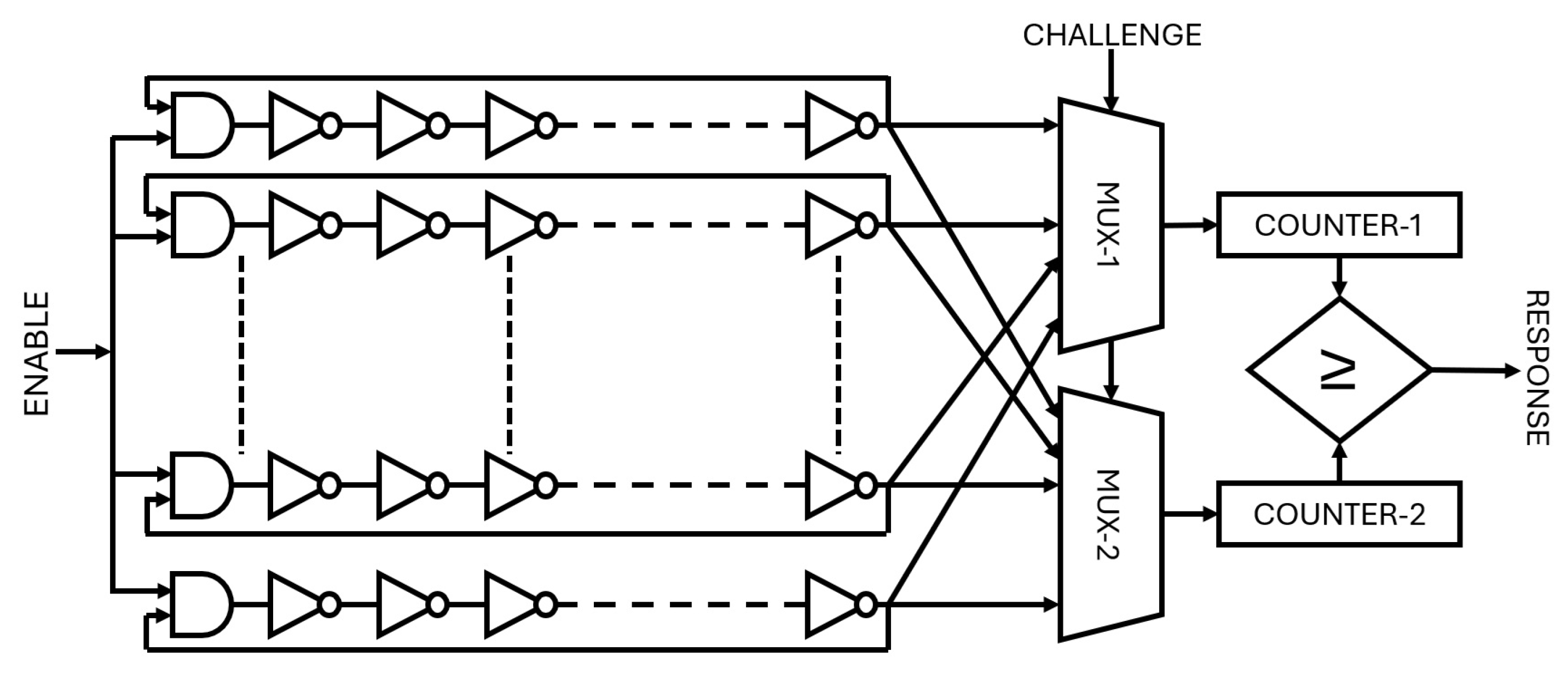

59]. The basic architecture of an RO PUF, as shown in

Figure 3, includes an odd number of inverter gates and an AND gate to enable or disable the feedback loop. The conventional RO-PUF consists of several essential components: n ring oscillators (ROs), two n-to-1 multiplexers (MUXs), two counters, and a comparator circuit. The outputs from each RO are routed to the inputs of both MUXs, whose selected outputs serve as clock signals for the counters. Each counter increments based on the oscillation frequency of the specific RO chosen by its respective MUX. Finally, the comparator compares the values stored in the two counters to produce the RO-PUF’s response, corresponding to the applied challenge inputs. The frequency of each RO depends on the delay of the inverters, which is influenced by variations in the manufacturing process.

|

Algorithm 1 Ring Oscillator PUF (RO-PUF) Algorithm |

-

Require:

Challenge input , Time window T

-

Ensure:

Response bit R

- 1:

Initialize N Ring Oscillators:

- 2:

Initialize two N-to-1 MUXs, two Counters: , , and a Comparator - 3:

Select via MUX A - 4:

Select via MUX B - 5:

Connect output to clock - 6:

Connect output to clock - 7:

Enable and for fixed time window T

- 8:

During T, increment counters on each RO oscillation pulse - 9:

After T, disable both counters - 10:

if then

- 11:

- 12:

else - 13:

- 14:

-

end if

returnR

|

The oscillation frequency of the RO PUF, as shown in eqn.

1 is inversely proportional to both the odd number of gates (n) and their average propagation delay (

). Consequently,

is sensitive to inherent variations in gate delay, which causes each instance of the RO structure to exhibit a slightly different oscillation frequency [

60].

The delay of each not gate is modelled by eqn.

2, where

is the nominal delay and

is a zero-mean random deviation, often approximated by gaussian,

.

The fundamental operation of the proposed RO PUF is outlined in algorithm 1. Initially, multiple ROs are instantiated, each consisting of an odd number of inverters connected in a closed loop chain, causing continuous oscillation due to intrinsic gate delays. For every response bit, a corresponding challenge input selects a pair of ROs through multiplexers. The oscillation frequencies of two selected ROs are recorded over a fixed time interval using counters. If the first RO exhibits a higher count, indicating a higher oscillating frequency, a response bit of ‘1’ is generated; otherwise, a ‘0’ is assigned.

3.3. PUF Performance Metrices

PUF performance metrics serve as key indicators of functional behavior and security robustness. Hamming distance (HD) serves as a critical metric to measure the degree of dissimilarity between two responses generated by a PUF. HD is further distinguished between intra-PUF and inter-PUF comparisons. The intra-PUF HD is an indicator of the dissimilarity between the responses of a single PUF, highlighting the internal consistency or variability of the PUF. On the other hand, the inter-PUF Hamming distance compares the responses between two different PUFs, offering a gauge of the uniqueness and distinguishability of each PUF’s responses. According to the classification presented by Pahlevi et al., the evaluation framework can be grouped into three main categories. The first category, conventional PUF evaluations, includes metrics such as uniqueness, uniformity, and reliability. These metrics assess how distinguishable the responses are between different devices, how evenly distributed the output bits appear, and how consistently the PUF can reproduce the same response under varying environmental or operational conditions. The second category focuses on authentication-oriented metrics, which evaluate the practical suitability of PUF for real-world security applications. Metrics such as the False Acceptance Rate (FAR) and False Rejection Rate (FRR) measure authentication accuracy, while bit aliasing and the Bit Error Rate (BER) capture bit-level stability and possible device bias. Entropy estimation is also included in this category to quantify the randomness present in the response set. The third category comprises machine learning based attack evaluations, which determine how well the PUF can withstand modern modeling attacks aimed at predicting its behavior [

62].

The performance of access control mechanisms is evaluated through four fundamental metrics derived from the confusion matrix are defined in equations

3,

4,

5, and

6 are false acceptance rate (FAR), the false rejection rate (FRR), the true acceptance rate (TAR), and the true rejection rate (TRR). The confusion matrix serves as a security evaluation metrics for PUFs, to assess the effectiveness and dependability of an authentication system. FAR indicates instances where unauthorized individuals are mistakenly granted access, while FRR reflects cases where legitimate users are unfairly denied access, highlighting crucial error dimensions that must be minimized [

63].

The use of a confusion matrix to evaluate an authentication system highlights its importance in measuring how effectively the system differentiates between legitimate access attempts and potential security breaches.

Uniqueness: It is used to quantify how different devices respond to the same input challenge. In other words, it is defined as the inter device Hamming Distance (HD) between different devices and its ideal value is 50%. The HD of equation

7 estimates the uniqueness of CRPs, where n is the total number of devices,

and

are the respective responses of the

and

devices under the same challenge,

is the Hamming Distance operator, and m is the bit length of each response.

Uniformity: It is the probability that the 0s and 1s are uniformly distributed in PUF’s response. Uniformity measures the balance between zeros and ones in the responses generated by a PUF. It is obtained by computing the average Hamming weight of the responses, as expressed in equation

8.

-

Reliability: It indicates the ability of a PUF to reproduce the same response bit for a given challenge input even when environmental conditions, such as supply voltage and temperature, vary. An ideal reliability close to 100% means that no bit flips occur across repeated measurements. However, achieving perfect reliability is difficult because PUF outputs are inherently sensitive to these variations.

A standard metric for reliability is the intra-class Hamming Distance, is illustrated in equation

9, where R and R’ are two responses from the same device under the same challenge.

Bit aliasing: It complements uniqueness and uniformity by verifying whether a given bit exhibits enough variation. Ideally, each bit appears randomly as 0 or 1 with a typical value of 50%, signifying minimal bias. The aliasing factor for the

bit is represented in equation

10, where

is the

bit of the

device’s response.

Bit Error Rate (BER): A BER defined in equation

11, gives an estimates of how often a PUF produces incorrect or flipped bits when the same challenge input is applied multiple times under varying environmental conditions such as temperature and supply voltage.

Entropy: It is used to evaluate the overall randomness of PUF outputs, particularly against advanced modeling attacks and side channel attacks. A higher entropy value reflects a larger and more unpredictable response space. The most widely used metric for this purpose is the Shannon entropy, defined as follows in equation

12:

where

represents every possible output pattern, and

denotes the probability associated with each pattern [

39].

3.4. ML Modelling Attacks

Resistance and reliability to the ML attacks are two major concerns for the overall viability of the PUF-based authentication protocols [

42]. ML-based attacks on PUFs can be catalogued as semi-invasive attacks, as adversaries exploit the PUF by intercepting the communication channel between the PUF client and server. The data is then preprocessed, and a parametric numerical model is built using ML algorithms that can successfully predict the PUF responses [

40,

41]. Adversaries’ carryout PUF modeling attacks using deep learning, LR, support vector machine, and evolution strategy, assuming access to CRPs [

52]. Countermeasures against ML attacks on PUFs are typically based on increasing the nonlinearity and complexity of the PUF model or integrating additional modules that enable more complex operating modes and communication protocols with the verifier [

44].

4. Experimental Setup and Implementation

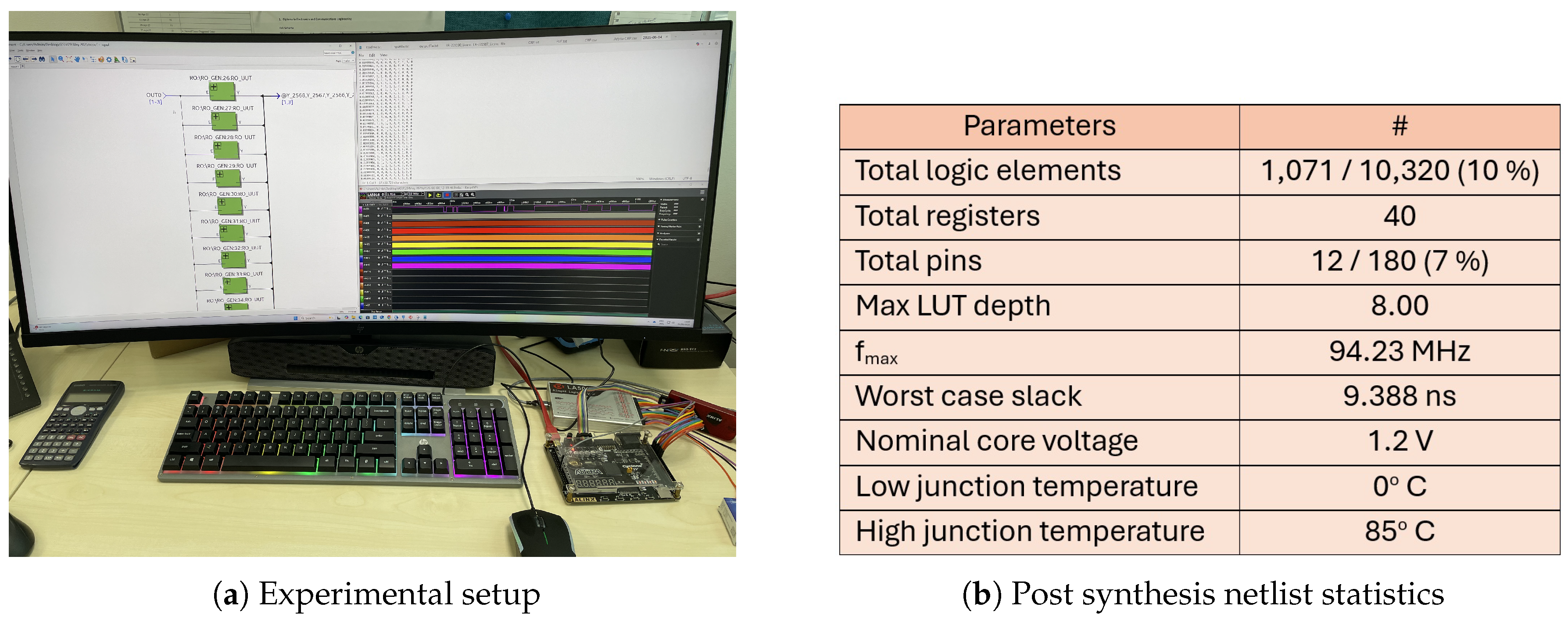

The experimental setup and synthesized netlist statistics of the proposed RO-PUF is shown in

Figure 4. The proposed architecture is implemented and verified using Cyclone IVE FPGA chips (EP4CE10F17C8) in the AX4010 development board. Quartus Prime 18.1 Lite Edition is used to develop and verify the RO-PUF design before configuring the FPGA device. The Cyclone IV E EP4CE10F17C8 is a low-cost, low-power FPGA developed by Intel. It features 10,320 logic elements, 414 Kbits of embedded memory, 179 user I/O pins, and four PLLs for flexible clock management, all packaged in a 256-pin FBGA. The RO-PUF design, implemented in VHDL, is interfaced with the onboard GPIO pins of the AX4010 development board. All control signals, including challenge inputs and response outputs, are connected to a 16-channel logic analyzer through these GPIO pins. The design incorporates 512 ring oscillators (ROs) comprising five inverters. The outputs of the ROs are routed to two sets of 256-to-1 multiplexers (MUXes). Each MUX selects one RO output based on the challenge input, determining which RO signal is passed to the output. The final response is generated by comparing the frequencies of two counters, Counter_A and Counter_B. An 8-bit Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR) is used to generate the challenge signals, based on the characteristic polynomial

.

The ML models, such as SVM, LR, MLP, and KNN, require careful parameter tuning to achieve optimal performance. For example, as illustrated in Table , SVM depends on the choice of kernel and gamma values, LR relies on regularization strength and iteration limits, MLP’s performance is influenced by hidden layer sizes, learning rates, and solver selection, while KNN requires choosing the appropriate number of neighbors and distance metrics. The training process involves preparing the PUF CRP dataset by separating the features from the responses and then splitting the data into training and testing sets for supervised learning. Validation and evaluation are carried out using metrics such as accuracy and confusion matrices to assess model performance. While train-test splits provide an initial measure of effectiveness, applying cross-validation techniques can further enhance reliability by reducing variance and ensuring the models generalize well to unseen CRPs.

4.1. NIST Randomness Test

Randomness plays a fundamental role in cryptography, as the strength of many security mechanisms relies on the unpredictability of generated sequences. However, generating truly random numbers is inherently challenging, and equally important is the rigorous evaluation of the quality of the generated data. To assess randomness, statistical tests are commonly employed, which yield a p-value. The p-value quantifies the probability that a truly random number generator would produce a sequence with less apparent randomness than the sequence being evaluated. In other words, it provides a statistical measure of how well the tested sequence aligns with the characteristics of an ideal random source.

Most empirical randomness tests, such as those included in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Statistical Test Suite (STS), are built on the principles of statistical hypothesis testing. The NIST STS consists of 15 well-defined tests that evaluate binary sequences for signs of non-randomness. These tests analyze both local and global properties of the data. At the local level, they assess features such as the balance between zeros and ones, or the frequency of specific bit patterns within smaller segments of the sequence. At the global level, they examine broader statistical behavior across the entire bitstream to determine overall randomness. To further refine detection, the bitstream is often partitioned into multiple large segments, where each segment is analyzed independently. The results from these segments are then aggregated into final test statistics, which help to identify localized irregularities or systematic deviations from randomness. This multi-layered evaluation ensures that both subtle and significant weaknesses in the sequence can be detected, providing a comprehensive measure of its suitability for cryptographic applications.

In the context of the NIST STS, the interpretation of p-values is crucial. For each test, a significance level (commonly set at 0.01) is defined. If the p-value obtained from a sequence is greater than or equal to 0.01, the sequence is considered to have passed that particular randomness test, indicating no strong evidence of non-random behavior. Conversely, a p-value below 0.01 suggests that the sequence may deviate significantly from randomness. Ideally, when a large number of independent sequences are tested, the distribution of p-values across all tests should be uniform within the interval [0,1]. This uniformity demonstrates that the data behaves consistently with what is expected from a true random source. Therefore, both the proportion of sequences passing each test and the uniformity of their p-value distribution are essential criteria in validating the randomness of cryptographic data.

Each NIST STS test is defined by a specific test statistic, which falls into one of three categories:

Bits: Analyzes characteristics such as proportion of bits, frequency of bit changes, and cumulative sums.

m-bit blocks: Analyzes distribution of m-bit blocks () within the sequence or its parts.

M-bit parts: Analyzes complex properties of M-bit parts (), such as matrix rank, sequence spectrum, or linear complexity.

Most tests are parameterized by

n (sequence length) and may include a second parameter

m or

M, depending on the test.

Table 2 summarizes the number of sub-tests included in the NIST STS suite. Notably, the non-overlapping template matching test has a variable number of sub-tests determined by

m [

61].

4.1.1. Brief Description of NIST Randomness Tests

Frequency (Monobit) test: Checks whether the number of ones and zeros are approximately equal.

Frequency within a block test: Evaluates proportion of zeros and ones in M-bit blocks; expected frequency of ones is .

Runs test: Measures consecutive runs of zeros and ones; checks if transitions occur at expected frequencies.

Longest run of ones in a block test: Examines if the longest run of ones (and zeros) in M-bit blocks matches the expected distribution.

Random binary matrix rank test: Evaluates the rank of sub-matrices to detect linear dependencies in the sequence.

Discrete Fourier Transform (Spectral) test: Detects periodic features using DFT peak heights.

Non-overlapping template matching test: Detects excessive occurrences of aperiodic m-bit patterns using a sliding window that resets after each match.

Overlapping template matching test: Counts occurrences of target substrings; window slides by one bit to allow overlaps.

Maurer’s Universal Statistical test: Measures compressibility of the sequence; overly compressible sequences indicate non-randomness.

Linear complexity test: Estimates the length of the feedback register required to reproduce the sequence; shorter lengths indicate predictability.

Serial test: Examines frequency of all overlapping m-bit patterns.

Approximate Entropy test: Compares frequencies of overlapping m-bit and -bit patterns to detect regularity.

Cumulative Sum (Cusum) test: Evaluates maximal deviation from zero in the cumulative sum of bits mapped to .

Random Excursions test: Measures the number of cycles with exactly K visits in cumulative sum random walks.

Random Excursions Variant test: Analyzes frequency of visits to specific states in cumulative sum random walks to detect non-random patterns.

4.1.2. Calibration

Calibration plays a critical role in ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of CRP acquisition when implementing PUFs on FPGAs. Since PUF responses are highly sensitive to environmental conditions such as temperature, voltage fluctuations, and aging, as well as measurement artifacts like timing misalignment, noise, and signal distortions, calibration methods are employed to minimize errors before feeding the data into ML-based security models.

-

Timing Calibration: Logic analyzers capture digital signals at high sampling rates ranging from hundreds of MHz to several GHz. However, any misalignment between challenge signals, response outputs, and control clocks can result in corrupted CRPs. The calibration strategies are discussed below.

- i)

Use a known reference signal, such as the FPGA internal clock or a test pattern generator, to align acquisition channels.

- ii)

Apply trigger-based synchronization in the logic analyzer to ensure consistent alignment of challenge vectors with corresponding responses.

-

Voltage and Signal Level Calibration:FPGA output signals may degrade due to voltage drop, temperature variations, or I/O mismatches. This can cause the logic analyzer to misinterpret logical ’0’ and ’1’ levels. The calibration techniques adopted are,

- i)

Adjust threshold voltage levels on the logic analyzer to match FPGA I/O standards (e.g., LVTTL, LVCMOS).

- ii)

Periodically recalibrate using known test vectors to verify that digital transitions are accurately captured.

-

Environmental Calibration: PUF responses are known to vary with temperature, supply voltage, and device aging. Environmental calibration ensures that CRPs remain stable and consistent under varying conditions. Calibration strategies include,

- i)

Use environmental profiling, where CRPs are collected across controlled temperature and voltage ranges, followed by applying corrective models.

- ii)

Apply ML-based preprocessing such as normalization or majority voting to compensate for environmental drift.

-

Noise Filtering and Signal Cleaning:High-frequency noise or transient glitches can distort CRP acquisition and lead to unstable datasets. Techniques used in noise filtering and signal conditioning are,

- i)

Apply digital filtering techniques (e.g., glitch removal, debouncing) during data preprocessing.

- ii)

Perform repeated measurements followed by majority voting to ensure transient noise does not bias the dataset.

-

Data Alignment and Synchronization: During multi-channel CRP acquisition, timing skew between channels can lead to incorrect challenge-response mapping. The calibration methods used for data alignment and synchronization include,

- i)

Perform multi-channel skew calibration by applying the same known signal to all acquisition channels and adjusting offsets accordingly.

- ii)

Use post-processing alignment algorithms to re-synchronize challenge-response mapping before ML training.

-

Statistical Calibration for ML Training: Before feeding CRPs into machine learning models, statistical calibration ensures data integrity and uniformity for reliable analysis. The calibration techniques include,

- i)

Compute intra-class and inter-class metrics to evaluate the reliability and uniqueness of CRPs.

- ii)

Apply whitening techniques (e.g., Linear Feedback Shift Register (LFSR) or hash-based methods) to eliminate bias in raw PUF data.

- iii)

Normalize datasets to prevent ML models from being influenced by imbalanced or skewed response distributions.

5. Results and Discussion

PUFs exploit the devices inherent physical randomness to generate unique and repeatable responses corresponding to challenge inputs. The key metric for measuring randomness, i.e., the balance between 0s and 1s in the output, is the relative frequency of bit 1 across all generated responses. This frequency provides a mathematical means to assess how uniformly bit 1 appears, which is critical in determining the PUF’s effectiveness for security purposes. In security applications, high unpredictability and an even distribution of binary values are essential. As expressed in the equation

13, relative frequency is calculated by dividing the total number of 1s by the overall number of response bits, thus an absolute indicator of the PUF’s randomness, and thereby its reliability and security suitability.

where p and K represent the relative frequency of bit 1 in all responses and the total number of responses, while L denotes the response length. In contrast, k and l refer to the response

and the position

bit in the response output, respectively.

Table 3 lists the uniqueness and uniformity values, which fall within the range of published RO PUF designs, but its reliability is noticeably lower than that of most prior works. However, lower reliability strengthen resilience against ML attacks as it introduces label noise into the challenge response pairs, making the PUF’s input–output mapping harder to learn.

To assess the randomness of a bit sequence, the equation

14 defines H as the minimum entropy anticipated from PUF outputs to exhibit uniform distribution. H peaks at 1 when

and hits its lowest at 0 when

or

. The best p is 0.5 for a binary system, as it produces the maximum entropy of 1 bit and represents the maximum uncertainty or randomness in a system. It also provides the strongest unpredictability and ensures resilience against cloning and prediction. The bitwise probability ’p’ and entropy ’H’ are plotted against varying CRPs in

Figure 5. This study also conducts a vulnerability assessment of the proposed FPGA-based RO-PUF design against machine learning (ML) modeling attacks. The challenge-response pair (CRP) data is split into training and testing sets in an 80% to 20% ratio to build the attack model. This setup enables a clear and meaningful evaluation of the prediction accuracy of various ML models, with CRP lengths scaling up to 80,000. The graph shown in

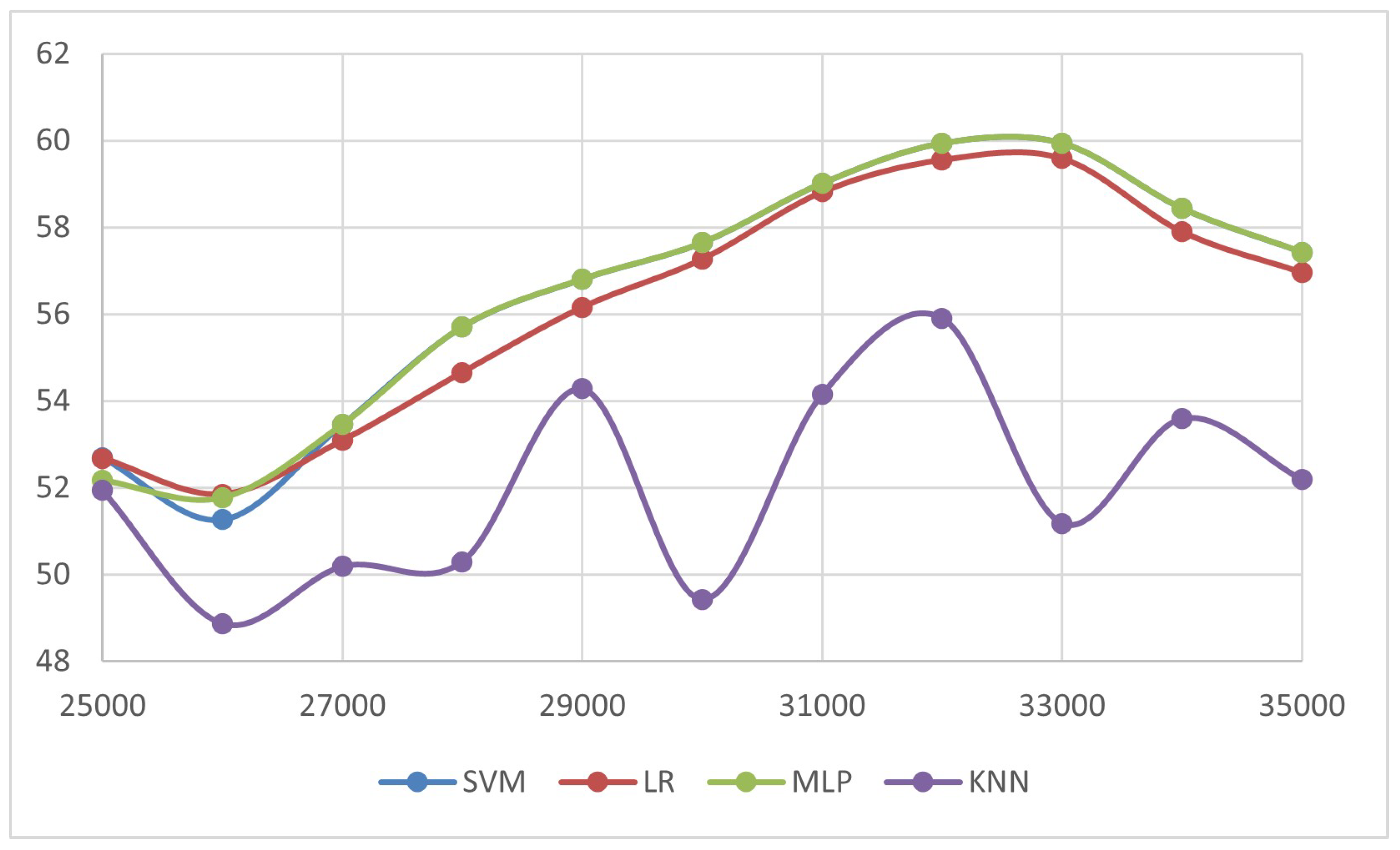

Figure 6 illustrates that the security of the PUF decreases as more CRP become available. LR and MLP achieve the highest prediction accuracy, meaning they pose the most effective modeling threat, while the SVM also shows moderate attack capability. In contrast, kNN performs poorly with low and unstable accuracy, indicating strong resistance against such attacks. Accuracy values rise with increasing challenge response pairs and peak around thirty-two thousand to thirty-three thousand, after which improvements saturate or slightly decline. Since lower accuracy corresponds to stronger security, the physical unclonable function remains most robust against attacks with limited challenge response pairs and when weaker models like kNN are used.

Table 4.

ML model accuracy against varying CRPs

Table 4.

ML model accuracy against varying CRPs

| Algorithm |

25K |

26K |

27K |

28K |

29K |

30K |

31K |

32K |

33K |

34K |

35K |

| SVM |

52.7 |

51.27 |

53.46 |

55.71 |

56.81 |

57.65 |

59.02 |

59.94 |

59.94 |

58.44 |

57.43 |

| LR |

52.68 |

51.85 |

53.09 |

54.66 |

56.16 |

57.27 |

58.82 |

59.56 |

59.91 |

57.9 |

56.96 |

| MLP |

52.17 |

51.77 |

53.46 |

55.71 |

56.81 |

57.65 |

59.02 |

59.94 |

59.94 |

58.44 |

57.43 |

| KNN |

51.94 |

48.87 |

50.19 |

50.30 |

54.28 |

49.43 |

54.16 |

55.91 |

51.18 |

53.6 |

52.19 |

The confusion matrix shown in

Figure 7 evaluates the performance of a classification model. The top-left cell represents true positives (TP), indicating the positive instances correctly identified by the model. The bottom-left cell shows false positives (FP), which are negative cases incorrectly classified as positive, and also known as type I errors. The top-right cell displays the number of false negatives (FN), referring to positive instances that were mistakenly predicted as negative. Finally, the bottom-right cell indicates true negatives (TN), where the model correctly identified negative instances. The sum of these four values gives the total number of predictions made by the model. Metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score can be derived from the confusion matrix to provide deeper insight into the model’s performance. Equation

15 presents an estimation of model accuracy based on the values in the confusion matrix.

Modeling attacks is becoming a significant security concern, aiming to imitate the challenge–response behavior of PUFs and replicate their secret authentication keys. In the context of lightweight PUF-based systems, these attacks are generally classified into three main types: (a) machine learning (ML)-based software attacks, (b) side-channel attacks, and (c) hybrid attacks that combine ML techniques with side-channel analysis. A typical generic model, typically polynomial, is used in ML-based modeling attacks for approximating CRP datasets. Adversaries divide the compromised CRP dataset into training and testing subsets. An iteration of inputting a challenge into the developed PUF model and its predicted response is carried out. The error between the predicted and actual response estimates a loss function; subsequently, the model parameters are updated using optimization strategies such as gradient descent in logistic regression (LR) or maximum likelihood estimation in support vector machines (SVMs). Finally, the model’s ability to replicate the actual PUF behavior is validated using the test set [

65]. However, the effectiveness and precision of ML-based attacks decline as the structural complexity of the PUF increases. In particular, strong PUFs, such as Ring Oscillator (RO) and Arbiter PUFs, that incorporate a high degree of nonlinear logic are more resistant to such modeling efforts.

5.1. Randomness Results

Table 5 summarizes the results of the NIST randomness tests conducted on the RO PUF CRP data. The P-value represents the likelihood that the observed bit sequence could have been produced by an ideal random source under the null hypothesis. In general, a sequence is considered random if its P-value exceeds the predefined significance level, typically 0.01, whereas values below this threshold indicate potential non-random behavior. It is important to emphasize that no single P-value alone confirms perfect randomness. Instead, a robust PUF should yield P-values that are uniformly distributed between 0 and 1 across various tests and sequences. Such a uniform distribution, along with the majority of P-values surpassing the 0.01 threshold, indicates that the CRP data exhibit statistical characteristics consistent with true randomness. Thus, it is concluded that FPGA-based RO-PUF can effectively resist ML modeling attacks, as shown in

Table 4. The ML models perform no better than random guessing (50% accuracy for binary responses) and the RO-PUF successfully prevents learning patterns, as the highest accuracy achieved is approximately 60%.

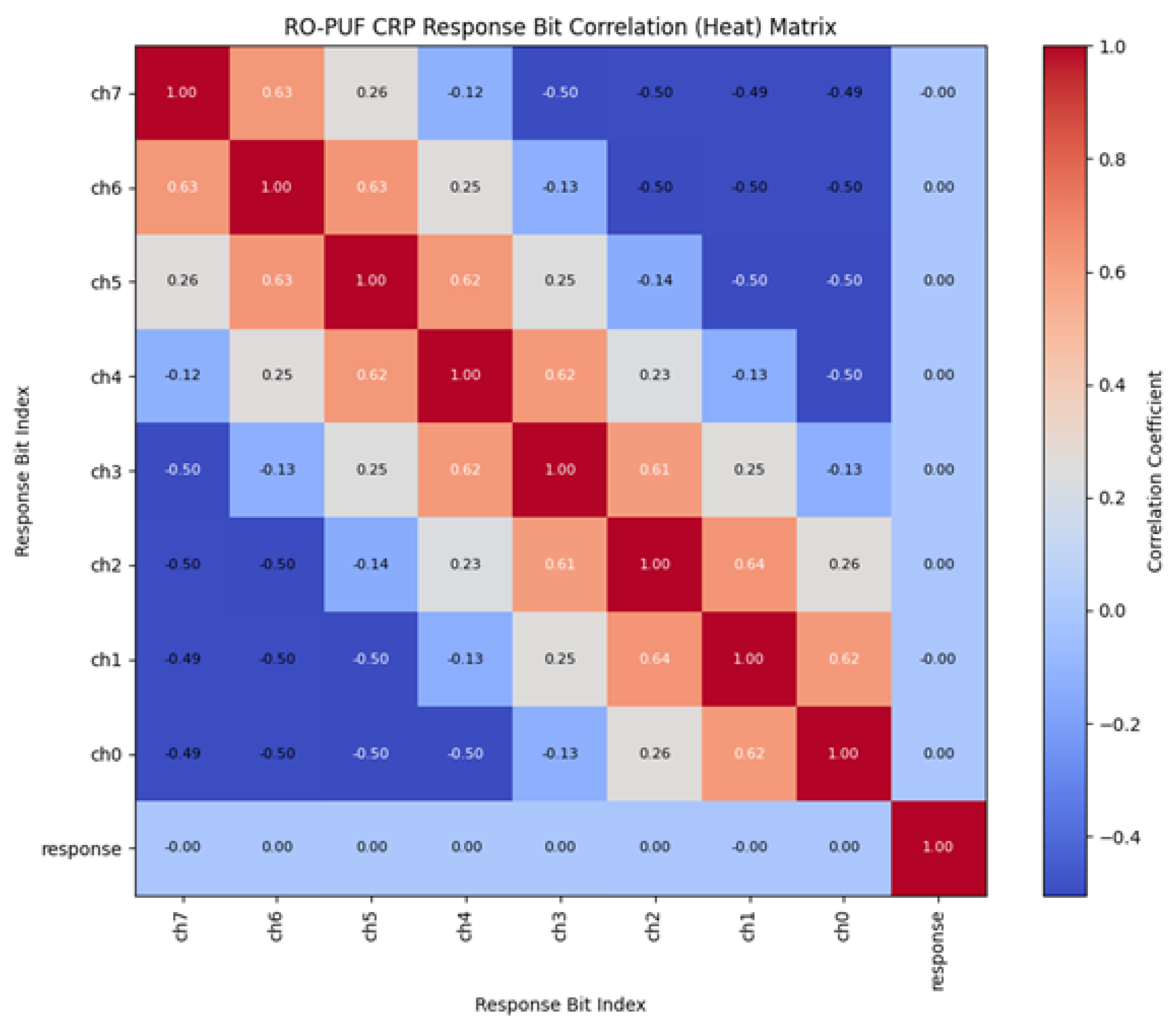

5.2. Correlation Matrix

The correlation matrix of the RO PUF CRP data in

Figure 8 illustrates the degree of dependency between different output bits generated by the RO PUF. Each cell in the matrix represents a correlation coefficient between two response bits, ranging from –1 to +1. The diagonal elements show perfect correlation (value of 1), indicating that each bit is fully correlated with itself.

The colors transition from red along the diagonal to blue in the off-diagonal regions, reflecting varying levels of inter-bit relationships. From the heatmap, it can be observed that adjacent bits exhibit moderate correlation, while distant bits tend to be weakly correlated or nearly independent. This pattern suggests that neighboring ring oscillators may share certain environmental or structural influences, such as local routing, power distribution, or temperature variations, which introduce partial dependency among nearby bits. However, as the distance between bits increases, the influence diminishes, and their correlation approaches zero. The overall low inter-bit correlation indicates that the RO PUF produces outputs that are largely independent and random, fulfilling one of the key requirements of a strong PUF design. The slight correlation observed between adjacent bits is expected in practical implementations due to physical proximity effects. To further enhance independence, post-processing techniques such as XOR-based bit mixing or improved oscillator placement strategies can be employed. In summary, the correlation matrix demonstrates that the RO PUF achieves good randomness and uniqueness characteristics, making it suitable for secure identification and authentication in hardware security applications.

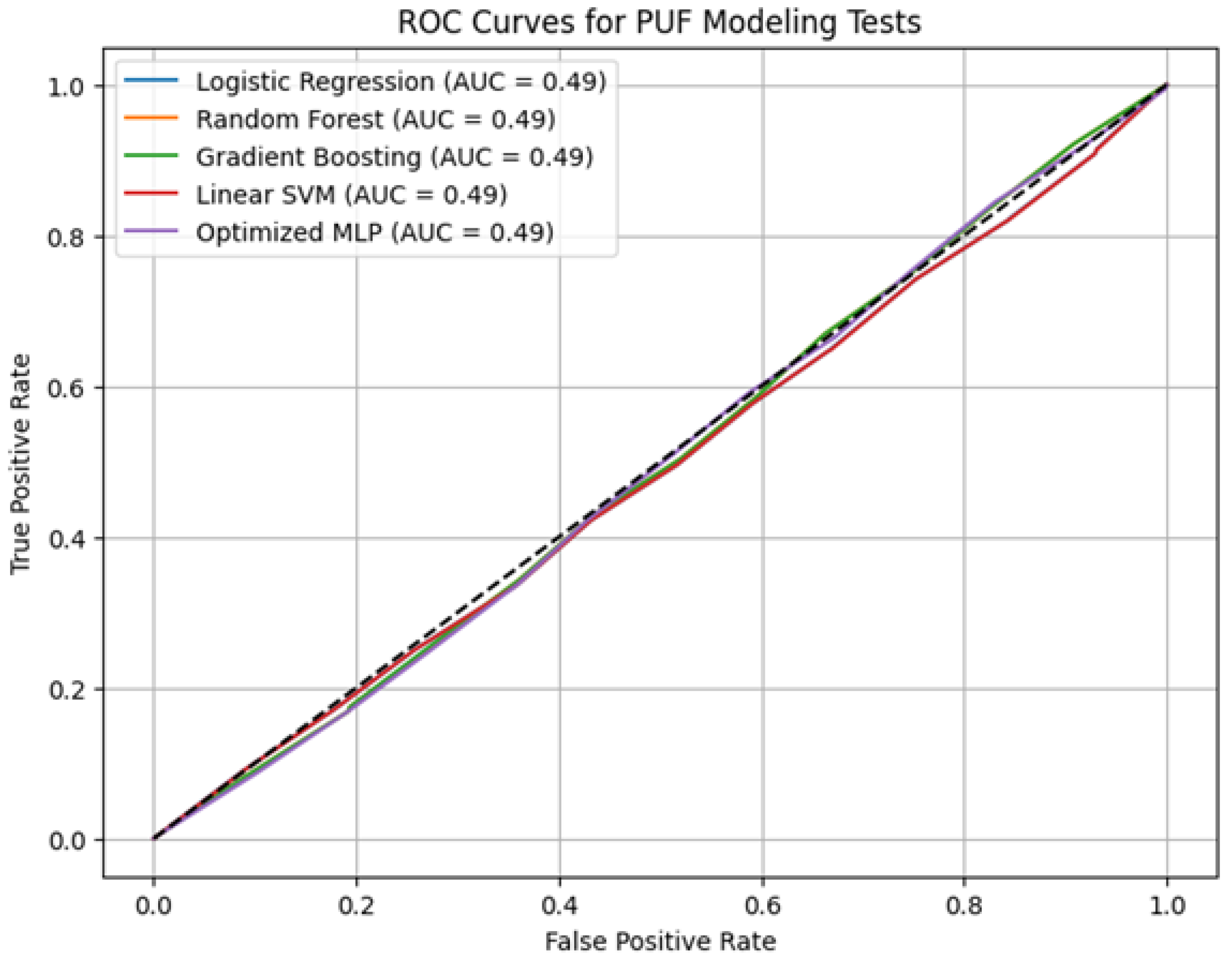

5.3. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC)

The ROC analysis for RO-PUF in

Figure 9, shows that all models—Logistic regression, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, SVM, and MLP—produced Area Under the Curve (AUC) values around 0.49, with ROC curves nearly overlapping the diagonal reference line. This behavior indicates that none of the models could distinguish the RO-PUF responses from random guessing, confirming its strong resistance to ML-based prediction. The intrinsic randomness and frequency-based variations of the oscillators introduce complex, nonlinear behavior that conventional ML algorithms cannot capture effectively.

6. Conclusion

Physically Unclonable Functions (PUFs) offer a cost-effective and reliable method for authenticating IoT devices due to their unique physical characteristics and ease of implementation. Nevertheless, despite being labeled as unclonable, PUFs can be vulnerable to modeling attacks if an adversary gains access to a portion of their challenge–response pairs (CRPs). In this work, we present a machine learning (ML)-resistant strong Ring Oscillator PUF (RO-PUF) architecture implemented on an FPGA. The design utilizes 512 RO chains, each consisting of five inverters, and employs an eight-bit challenge to generate a response bit. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed RO-PUF significantly improves resilience against ML-based modeling attacks, effectively hindering adversaries from constructing accurate predictive models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.S., M.R.I. and M.H.H.; methodology, A.M.S.; software, A.M.S. and M.H.H.; validation, A.M.S., M.R.I. and M.H.H.; formal analysis, A.M.S., M.H.H., S.A.Z., A.R. and A.K.; investigation, A.M.S. and M.R.I.; resources, M.R.I., M.H.H. and A.K.; data curation, A.M.S. and M.R.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.S; writing—review and editing, M.R.I., M.H.H., S.A.Z., A.R. and A.K.; visualization, M.H.H., S.A.Z. and A.R.; supervision, M.R.I. and M.H.H.; project administration, A.K.; funding acquisition, A.M.S. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by A’Sharqiyah University, Oman-Internal Research Grant (IRG-16), 2024-26, "Intrusion detection in an IoT network through Machine Learning (ML) of hardware characteristics” and “The APC was funded by A’Sharqiyah University, Oman.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| CEC |

Collaborative Edge Computing |

| CRPs |

Challenge Response Pairs |

| DDoS |

Distributed Denial of Service |

| DT |

Decision Trees |

| EC |

Edge Computing |

| FN |

False Negatives |

| FP |

False Positives |

| FPGAs |

Field Programmable Gate Arrays |

| ICs |

Integrated Circuits |

| IDS |

Intrusion Detection Systems |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IP |

Intellectual Property |

| KNN |

K-Nearest Neighbor |

| LR |

Logistic Regression |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| MiTM |

Man in the Middle |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MLP |

Multilayer Perceptron |

| NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| PUF |

Physical Unclonable Function |

| RF |

Random Forests |

| RO |

Ring Oscillator |

| STS |

Statistical Test Suite |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| TN |

True Negatives |

| TP |

True Positives |

References

- Albreem, M.A.; Sheikh, A.M.; Alsharif, M.H.; Jusoh, M.; Yasin, M.N.M. Green Internet of Things (GIoT): Applications, Practices, Awareness, and Challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 38833–38858. [CrossRef]

- Kokila, M.; K, S.R. Authentication, access control and scalability models in Internet of Things Security–A review. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3. [CrossRef]

- Albreem, M.A.; Sheikh, A.M.; Bashir, M.J.K.; El-Saleh, A.A. Towards green Internet of Things (IoT) for a sustainable future in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: current practices, challenges and future prospective. Wirel. Networks 2022, 29, 539–567. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Rani, S.; Raza, S.; Qureshi, N.M.F.; Mansour, R.F.; Ragab, M. Security paradigm for remote health monitoring edge devices in internet of things. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 101478. [CrossRef]

- Badhib, A.; Alshehri, S.; Cherif, A. A Robust Device-to-Device Continuous Authentication Protocol for the Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 124768–124792. [CrossRef]

- Giguère, François, “Edge Computing in IoT: Transforming Security Paradigms Through Advanced Forensics,” 2024.

- Thomas, Chips, “IoT and Edge Computing Convergence: Revolutionizing Security and Forensic Applications,” 2024.

- Sheikh, A.M.; Islam, R.; Habaebi, M.H.; Kabbani, A.; Zabidi, S.A.; bin Najeeb, A.R. Securing the IoT Edge Devices Using Advanced Digital Technologies. Asian J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2024, 4, 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Tan, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Jin, X.; Zeng, P.; Khan, M.K.; Das, S.K. Edge-computing-driven Internet of Things: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–41. [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Yusoff, M.Z.; Khan, M.; Baloch, M.H.; Shaikh, A.M.; Chauhdary, S.T. Solar Energy Optimal Grid Integration Through Machine Learning Techniques. Int. J. Energy Convers. (IRECON) 2024, 12, 40. [CrossRef]

- Alnuaimi, R.A.; Almasalmeh, R.K.; Alhammadi, E.A.; Hassan, G.E.B.M.E.; Zia, H. Optimizing Edge Security: Comprehensive Analysis and Mitigation Strategies for Securing Edge Computing. 2023 9th International Conference on Optimization and Applications (ICOA). United Arab Emirates; pp. 1–7.

- Sheikh, A.M.; Islam, R.; Habaebi, M.H.; Kabbani, A.; Zabidi, S.A.; bin Najeeb, A.R. Securing the IoT Edge Devices Using Advanced Digital Technologies. Asian J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2024, 4, 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Manan, A., “Efficient 16 nm SRAM Design for FPGA’s”, 5th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), pp. 457–461,IEEE, 2018.

- Manan, A., “Implementation of image processing algorithm on FPGA”, Akgec Journal of Technology, vol. 2(1), pp. 25–28, 2006.

- Lata, K.; Cenkeramaddi, L.R. FPGA-Based PUF Designs: A Comprehensive Review and Comparative Analysis. Cryptography 2023, 7, 55. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A. M., Islam, M. R., Habaebi, M. H., Zabidi, S. A., Najeeb, A. R. B., and Basahel, A., “Machine Learning (ML) assisted Edge security framework on FPGAs”, 9th International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE), pp. 155–160, IEEE, 2023.

- Sheikh, A.M.; Islam, R.; Habaebi, M.H.; Zabidi, S.A.; Bin Najeeb, A.R.; Kabbani, A. Integrating Physical Unclonable Functions with Machine Learning for the Authentication of Edge Devices in IoT Networks. Futur. Internet 2025, 17, 275. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Park, K.; Park, Y. A Machine Learning Attack-Resistant PUF-Based Robust and Efficient Mutual Authentication Scheme in Fog-Enabled IoT Environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 20652–20669. [CrossRef]

- Anandakumar, N.N.; Hashmi, M.S.; Sanadhya, S.K. Design and Analysis of FPGA-based PUFs with Enhanced Performance for Hardware-oriented Security. ACM J. Emerg. Technol. Comput. Syst. 2022, 18, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Ding, L.; Sun, J.; Jing, C.; Guo, F.; Wu, C. Edge Computing for IoT Security: Integrating Machine Learning with Key Agreement. 2023 3rd International Conference on Consumer Electronics and Computer Engineering (ICCECE). China; pp. 474–483.

- Aarella, S.G.; Mohanty, S.P.; Kougianos, E.; Puthal, D. Fortified-Edge: Secure PUF Certificate Authentication Mechanism for Edge Data Centers in Collaborative Edge Computing. GLSVLSI '23: Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI 2023. United States; pp. 249–254.

- Cheng, G.; Chen, Y.; Deng, S.; Gao, H.; Yin, J. A Blockchain-Based Mutual Authentication Scheme for Collaborative Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2021, 9, 146–158. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y. Keep Your Data Locally: Federated-Learning-Based Data Privacy Preservation in Edge Computing. IEEE Netw. 2021, 35, 60–66. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shen, C.; Guo, Z.; Wu, Q.; Chang, W. CT PUF: Configurable Tristate PUF Against Machine Learning Attacks for IoT Security. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 14452–14462. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimabadi, M.; Younis, M.; Karimi, N. A PUF-Based Modeling-Attack Resilient Authentication Protocol for IoT Devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 3684–3703. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Koo, D.; Hur, J. Secure and Efficient Hybrid Data Deduplication in Edge Computing. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2022, 22, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Rullo, A.; Bertino, E.; Ren, K. Guest Editorial Special Issue on Intrusion Detection for the Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 8327–8330. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Ganguly, S.; Sarkar, P.S.; Chatterjee, S.R. PUF-Based Authentication System with Resilience against Multi-Faceted Attacks for Blockchain-based IoT Networks. 2024 IEEE 3rd World Conference on Applied Intelligence and Computing (AIC). India; pp. 1279–1284.

- Aparicio-Téllez, R.; Garcia-Bosque, M.; Díez-Señorans, G.; Celma, S. Novel Machine Learning-Resistant RO-Based PUF Optimized for IoT Device Authentication. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 46147–46160. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Huang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Q. A Novel Configurable RO-Obfuscated PUF Design with Machine Learning Immunity. 2023 International Conference on Networking and Network Applications (NaNA). China; pp. 680–685.

- Kareem, H.; Dunaev, D. Machine Learning Vulnerability Assessment of Ring Oscillator Physical Unclonable Functions. 2023 International Conference on Control, Automation and Diagnosis (ICCAD). Italy; pp. 1–5.

- Abulibdeh, E., Saleh, H., Mohammad, B., Alqutayri, M. and Santikellur, P., “Algorithmically Optimized Configurable Ring Oscillator Puf for Iot Devices”. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5327693.

- Miskelly, J.; Gu, C.; Ma, Q.; Cui, Y.; Liu, W.; O'NEill, M. Modelling Attack Analysis of Configurable Ring Oscillator (CRO) PUF Designs. 2018 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Digital Signal Processing (DSP). China; pp. 1–5.

- Laguduva, V., Islam, S.A., Aakur, S., Katkoori, S. and Karam, " Machine learning based iot edge node security attack and countermeasures "IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), pp. 670–675, 2019.

- E. E. Abulibdeh, Reliable and Efficient Hardware Implementation of PUFs for Secure IoT Applications, Ph.D. dissertation, Khalifa University of Science, 2024.

- Teo, J.H.L.; Hashim, N.A.N.; Ghazali, A.; Hamid, F.A. Ring oscillator physically unclonable function using sequential ring oscillator pairs for more challenge-response-pairs. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2019, 13, 892–901. [CrossRef]

- Zerrouki, F.; Ouchani, S.; Bouarfa, H. PUF-based mutual authentication and session key establishment protocol for IoT devices. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2022, 14, 12575–12593. [CrossRef]

- Y. Gao, S. F. Al-Sarawi, and D. Abbott, “Physical unclonable functions,” Nature Electronics, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 81–91, 2020.

- Al-Meer, A.; Al-Kuwari, S. Physical Unclonable Functions (PUF) for IoT Devices. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–31. [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Ma, H.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, D.; Deng, E.; Wang, Y. A Reconfigurable Arbiter MPUF With High Resistance Against Machine Learning Attack. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2021, 57, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Anupama, A.; Raja, I.; Roy, D.; Padmakumar, K. A Ring Oscillator-based Strong Physical Unclonable Function with Excellent Resilience to Machine Learning Attacks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, PP, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Sajadi, A.; Shabani, A.; Alizadeh, B. DC-PUF: Machine learning-resistant PUF-based authentication protocol using dependency chain for resource-constraint IoT devices. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2023, 217. [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Dofe, J. Counteracting Modeling Attacks Using Hardware-Based Dynamic Physical Unclonable Function. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR). Italy; pp. 586–591.

- Ferens, M.; Dushku, E.; Kosta, S. When Random Is Bad: Selective CRPs for Protecting PUFs Against Modeling Attacks. IEEE Trans. Comput. Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2024, 44, 1648–1661. [CrossRef]

- Hazari, N.A.; Alsulami, F.; Oun, A.; Niamat, M. Performance Analysis of XOR-Inverter based Ring Oscillator PUF for Hardware Security. NAECON 2019 - IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference. USA; pp. 253–256.

- Kareem, H.; Dunaev, D. A novel low hardware configurable ring oscillator (CRO) PUF for lightweight security applications. Microprocess. Microsystems 2023, 104. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, W.; Gu, C.; O'NEill, M.; Lombardi, F. Lightweight Configurable Ring Oscillator PUF Based on RRAM/CMOS Hybrid Circuits. IEEE Open J. Nanotechnol. 2020, 1, 128–134. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, C.; Ke, T.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, W.; Jiang, J. A highly reliable FPGA-based RO PUF with enhanced challenge response pairs resilient to modeling attacks. IEICE Electron. Express 2021, 18, 20210350–20210350. [CrossRef]

- Zulfikar, Z.; Soin, N.; Hatta, S.F.W.M.; Abu Talip, M.S.; Jaafar, A. Routing Density Analysis of Area-Efficient Ring Oscillator Physically Unclonable Functions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9730. [CrossRef]

- Zulfikar, Z.; Soin, N.; Hatta, S.F.W.M.; Abu Talip, M.S. Runtime Analysis of Area-Efficient Uniform RO-PUF for Uniqueness and Reliability Balancing. Electronics 2021, 10, 2504. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, C.; Ke, T.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, W.; Jiang, J. A highly reliable FPGA-based RO PUF with enhanced challenge response pairs resilient to modeling attacks. IEICE Electron. Express 2021, 18, 20210350–20210350. [CrossRef]

- Maiti, A.; Casarona, J.; McHale, L.; Schaumont, P. A large scale characterization of RO-PUF. 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Hardware-Oriented Security and Trust (HOST). United States; pp. 94–99.

- Suh, G. Edward, and Srinivas Devadas. "Physical unclonable functions for device authentication and secret key generation." In Proceedings of the 44th annual design automation conference, pp. 9-14. 2007.

- M. Naveed, K. C. Chua, and B. Sikdar, “Physical unclonable functions for IoT security,” in Proc. 2nd ACM International Workshop on IoT Privacy, Trust, and Security, 2016.

- Sheikh, A.M.; Islam, R.; Habaebi, M.H.; Zabidi, S.A.; Bin Najeeb, A.R.; Kabbani, A. A Survey on Edge Computing (EC) Security Challenges: Classification, Threats, and Mitigation Strategies. Futur. Internet 2025, 17, 175. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B.; Das, D.; Maity, S.; Sen, S. RF-PUF: Enhancing IoT Security Through Authentication of Wireless Nodes Using In-Situ Machine Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 388–398. [CrossRef]

- Modarres, A.M.A.; Anzabi-Nezhad, N.S.; Zare, M. A New PUF-Based Protocol for Mutual Authentication and Key Agreement Between Three Layers of Entities in Cloud-Based IoMT Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 21807–21824. [CrossRef]

- Yehoshuva, C.; Adhithan, R.R.; Anandakumar, N.N. “A survey of security attacks on silicon based weak PUF architectures,” in Proc. International Symposium on Security in Computing and Communication, pp. 107–122, 2020.

- Kareem, H.; Dunaev, D. A robust architecture of ring oscillator PUF: Enhancing cryptographic security with configurability. Microelectron. J. 2023, 143. [CrossRef]

- M. Budnik, “Design and evaluation of a Ring Oscillator based Physically Unclonable Function,” B.S. thesis, University of Twente, 2023.

- Marton, K., and Suciu, A., "On the interpretation of results from the NIST statistical test suite,"Science and Technology, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 18–32, 2015.

- Pahlevi, R.R.; Hasegawa, H.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Shimada, H. A Pre-Selection–Enhanced Arbiter PUF for Strengthening PUF-Based Authentication. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 127526–127544. [CrossRef]

- Sukarno, P.; Medina, F.R. Enhancing IoT Security: Optimizing PUF Responses through Pre-Processing Techniques. J. INFOTEL 2025, 17, 210–228. [CrossRef]

- Al-Meer, A.; Al-Kuwari, S. Physical Unclonable Functions (PUF) for IoT Devices. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–31. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Bitragunta, S.; Tiwari, K. PUF-AQKD: A Hardware-Assisted Quantum Key Distribution Protocol for Man-in-the-Middle Attack Mitigation. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025, 6, 4923–4942. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).