1. Introduction

Wide bandgap (WBG) devices are extensively used in power electronics, particularly in automotive and renewable-energy applications. Over the past decade, DC-DC power converters have gained significant attention due to their expanding role across sectors ranging from aerospace to renewable energy. In renewable energy systems, especially grid-tied photovoltaic applications galvanically isolated, unidirectional LLC resonant converters have become common and the focus of numerous studies [

1]. Efforts in low-voltage power converters have concentrated on improving key characteristics such as reliability, wide input and load ranges, low electromagnetic interference (EMI), and high efficiency. According to Parvez, Mohammad,

et al. [

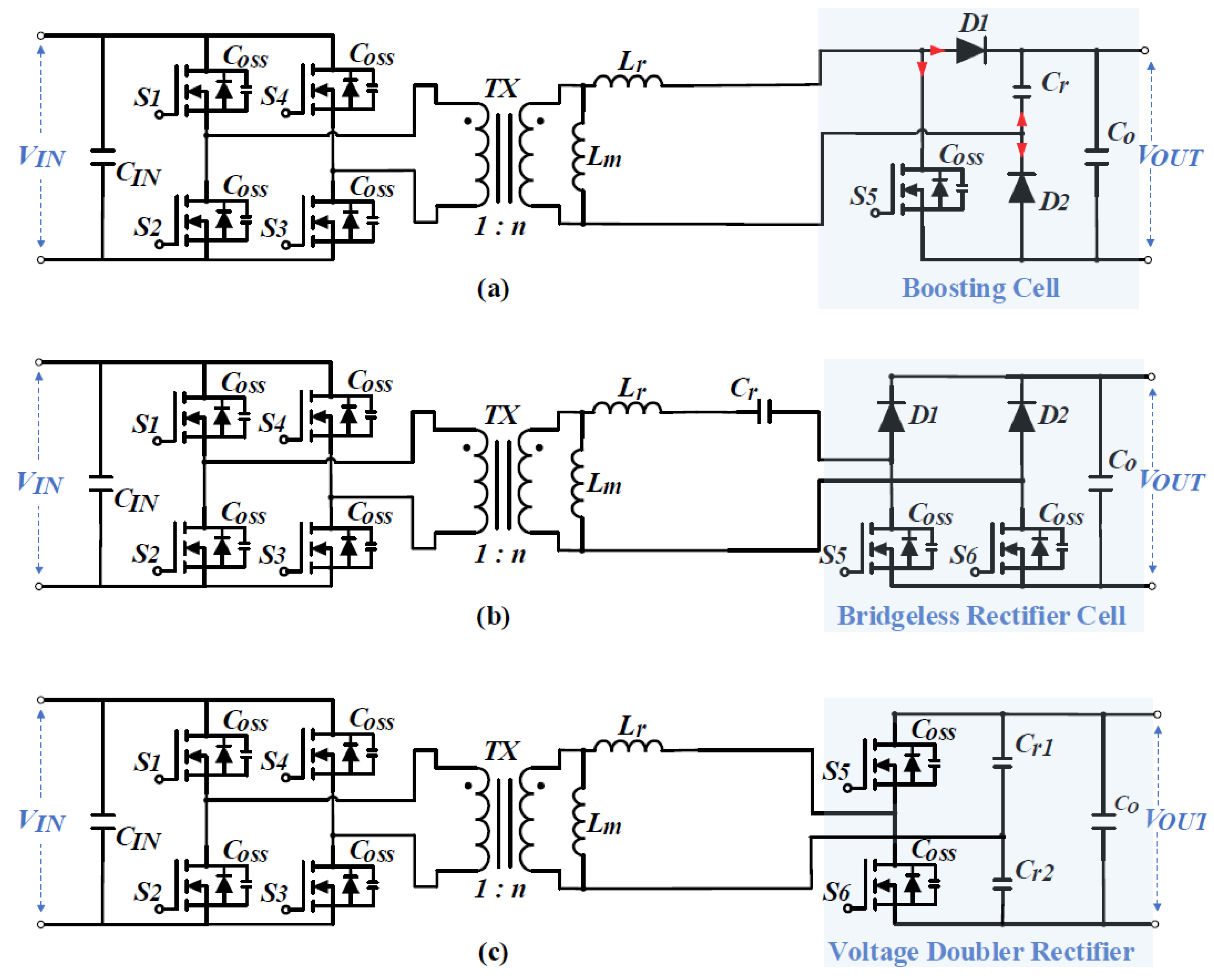

2], isolated resonant converters can be broadly classified into three types: resonant-boost converters, hybrid resonant converters, and resonant single-ended primary-inductor converters (SEPIC). Resonant-boost converters are commonly employed in solar-energy systems to accommodate fluctuations in solar input. Recent advancements have introduced hybrid resonant converters with improved rectifier cells, offering a broad input-voltage range and California Energy Commission (CEC) efficiencies exceeding 96% [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. These topologies are designed to minimize component counts in rectifier tanks and extend the regulation range, as shown in

Figure 1. For example, a resonant-boost converter with a simplified boosting rectifier cell has been proposed [

7]. While this design reduces voltage stress on the resonant capacitor by clamping it at the output-voltage level, it does not fully accommodate variations in input voltage and output power. Although this topology has a limited input-voltage regulation range due to high step-up ratios and load currents [

8], it remains valuable for studying the switching performance and reliability of modern power devices.

Recently, SiC power devices degradation has been extensively discussed at the device level under harsh environments such as high temperature and radiation [

9,

10,

11,

12]. However, the reliability of power converters, especially under high radiation doses, remains underexplored. Existing reliability assessments for power converters mostly rely on experimental testing, which is costly and case-specific. Thus, the development of system-level evaluation frameworks that explicitly incorporate device degradation is needed. Although several simulation-based SiC DC-DC converters have been designed and evaluated using PSIM manufacturer simulation tool [

13,

14,

15,

16]. While these studies analyze power losses and overall efficiency, they lack in-depth analysis of device reliability and do not fully leverage the simulation tool’s capabilities. For system-level simulation of power converters, physics-based models often suffer from convergence issues and long runtime [

17,

18,

19], whereas simplified models in simulation tools such as PSIM or PLECS sacrifice accuracy. To achieve both computational efficiency and degradation-aware modeling, a methodology that explicitly incorporates degradation effects in SiC power MOSFETs is required.

In this study, a novel simulation framework to model thermal and radiation induced degradation and quantify its impact on power converter efficiency. This approach facilitates extensive research without being constrained by datasheet limitation. Also, these two strategies offer a convenient approach for researchers and application engineers to evaluate the reliability of power converters under harsh environment conditions before conducting experiments. For comparison, both Si and SiC-based resonant converters with a boost cell are evaluated in PSIM. In addition, the results show that SiC-based converters are more reliable than their Si-based counterparts in harsh environments.

2. New Proposed Simulation Methodology

2.1. PSIM Thermal Model

Dynamic simulation in complex converter topologies remains a challenge for achieving a balance between accuracy, convergence reliability and simulation speed [

20]. For new design topologies, the ideal models are first employed to verify the feasibility of the topology and its control scheme. Additionally, the thermal model can be employed to estimate switching losses and conduction losses in power devices. In PSIM, dedicated thermal models idealize switching transitions and evaluate losses using lookup tables. The parameters for the look-up table used in this work are shown in

Table 1. The calculations in the PSIM simulation can account various conditions, such as the conducted voltage and current across the switch, junction temperature and gate drive voltage, and physic parameters such as parasitic capacitance and

. It provides a good correlation with actual power losses while significantly reducing the computational time compared to the SPICE model. Although the present thermal model does not account for device degradation, degradation-aware device models can be incorporated in the future to enable system-level performance analysis. From both reliability and lifetime perspectives [

21,

22], this integration offers clear benefits. It enables more predictive loss and stress estimation and reduces reliance on costly long-duration experiments.

In PSIM, the calculation of conduction losses (

) and on/off switching losses (

) is given by [

23]:

where,

is the root-mean-square value of the conducted current (obtained from the switching waveform), and

which depends on the junction temperature

.

can be expressed as:

where

is the normalized on-state resistance at

(from the data-sheet’s normalized

versus temperature curve) and

is the corresponding temperature coefficient. However, in the thermal strategy,

is not applied in the simulation, because the actual

is obtained directly using a curve tracer. The junction temperature is fixed at

, so the measured

and

from

Figure 5 can be used in the thermal model without calculating

, providing a flexible and practical solution for system evaluation.

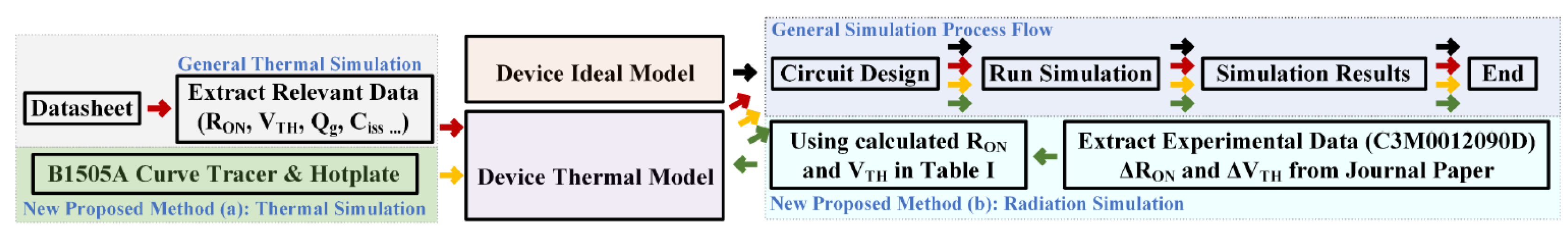

2.2. A New Simulation Method

A newly proposed simulation method to assess the efficiency and reliability of DC-DC resonant converter includes two strategies: (a) Thermal Simulation and (b) Radiation Simulation, illustrated in

Figure 2. Both simulations utilize the PSIM simulation tool and its thermal model. In this paper, SiC-based resonant converter is evaluated under a wide-range temperature and radiation doses conditions. The conventional simulation approach employs a thermal model to estimate the switching and conduction losses for each device in the system. This model is based on datasheet characteristics, which can limit the exploration and evaluation of device performance in system-level analysis, especially for scenarios such as a resonant converter operating at high temperatures exceeding 175 °C.

To analyze the performance and degradation of SiC devices in a resonant tank, a simulation method is illustrated in

Figure 2. This method includes two key strategies:

Thermal Strategy: This involves calibrating the power device using the B1505A curve tracer, with the device placed on a hot plate for high-temperature testing. The resulting characteristics, typically not provided in the datasheet, are then applied in thermal simulation using a system-level simulation tool.

Radiation Strategy: This utilizes relevant data, specifically the changes in

and

, from the article [

24] on the commercial SiC power device (C3M012090D) under investigation. The

and

values calculated at various total ionizing doses (TIDs), as shown in

Table 2, are then integrated into the PSIM thermal model.

Thus, both thermal and radiation strategies offer valuable benefits for researchers engaged in extensive studies. While this work focuses on analyzing only the

and

parameters at the device level, other parameters listed in

Table 1 can also be modified and examined. This approach enables device-level degradation insights to be extended to system-level analysis. Although current system-level simulators are limited and power loss remains the principal observable of converter after device degradation, the framework developed here is readily extensible. The present method cannot yet resolve degradation effects at the control-waveform level. In the future, degradation-aware device models could relate device degradation to system-level dynamics, for example by accounting for BTI (Bias Temperature Instability)-induced shifts in the gate plateau that delay rising and falling edges, and threshold voltage variation that affects the voltage slew rate [

25,

26,

27]. In subsequent studies, false turn-on events could become observable under high slew-rate and crosstalk conditions, especially in the presence of both aging-induced and radiation-induced threshold shifts.

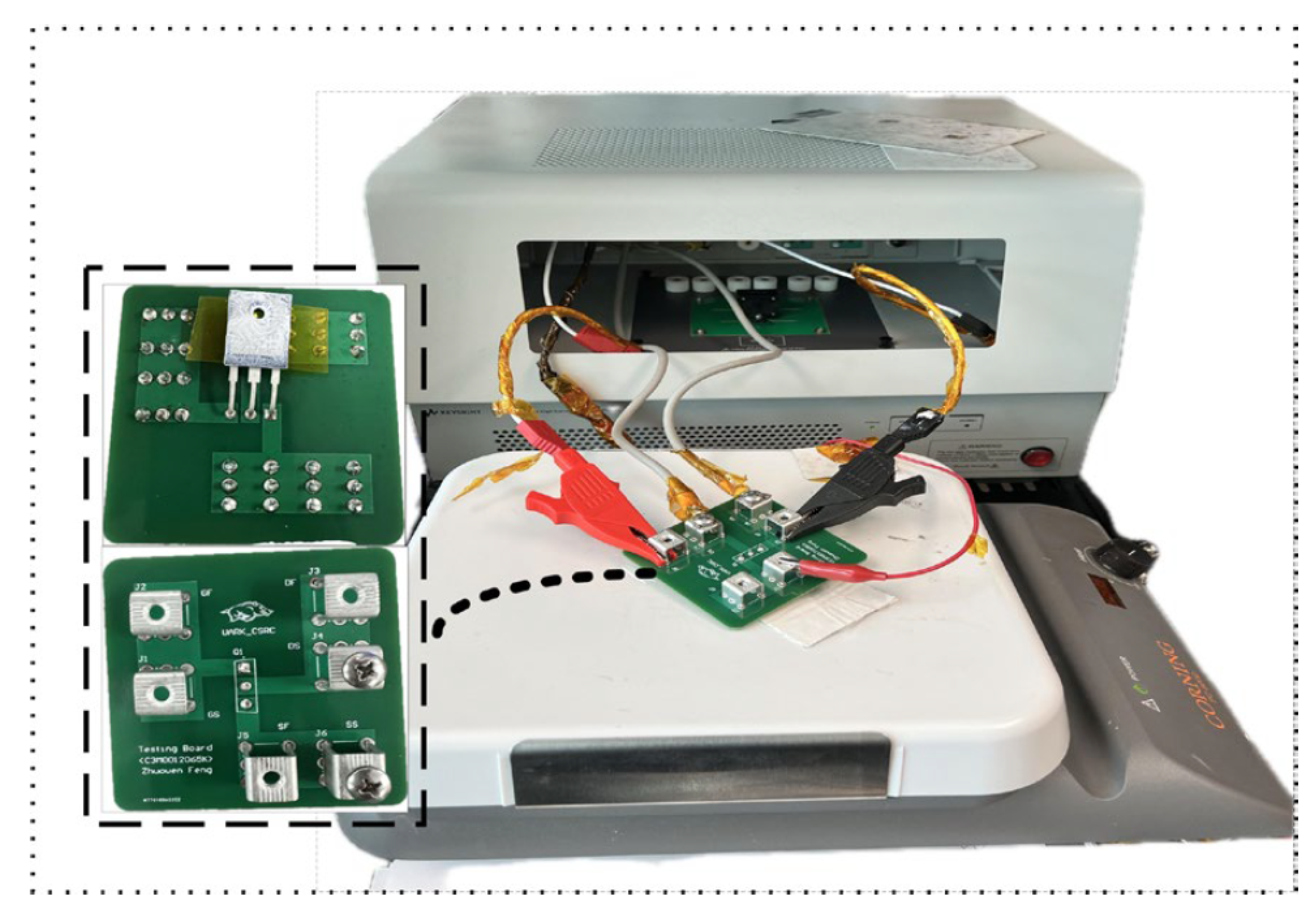

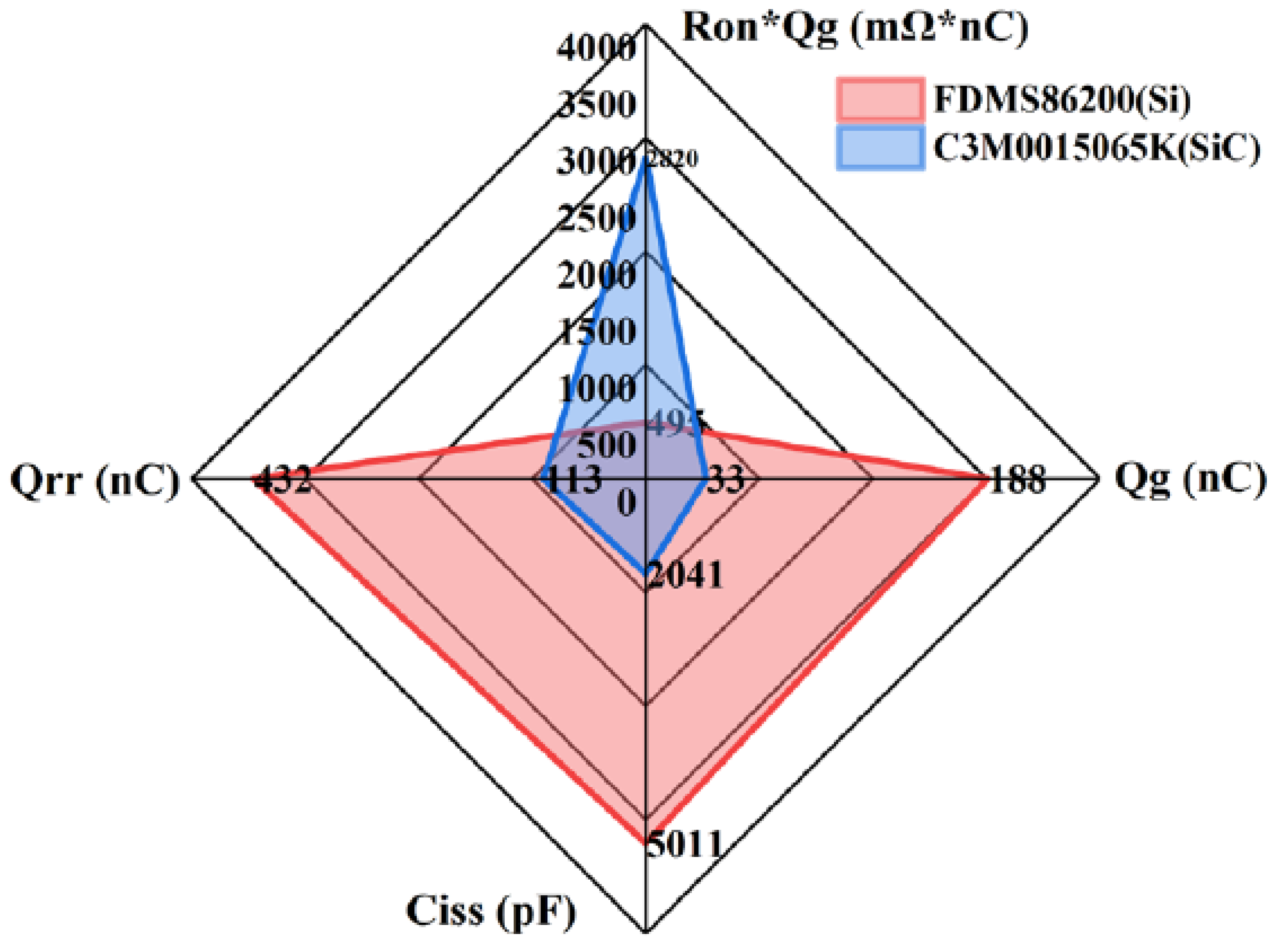

2.3. Device Calibration

This study examines two commercial devices, a Si MOSFET (FDMS86200) and a SiC MOSFET (C3M0015065K), each with a typical

of 15 m

.

Table 1 summarizes the key device parameters, and

Figure 3 compares their dynamic performance and figure of merit (FOM). To address potential discrepancies between datasheet transfer characteristics and actual device behavior, the B1505A curve tracer was used for precise measurement of

and

. The combination of an extended printed circuit board (PCB) and hot plate to control the junction temperature is illustrated in

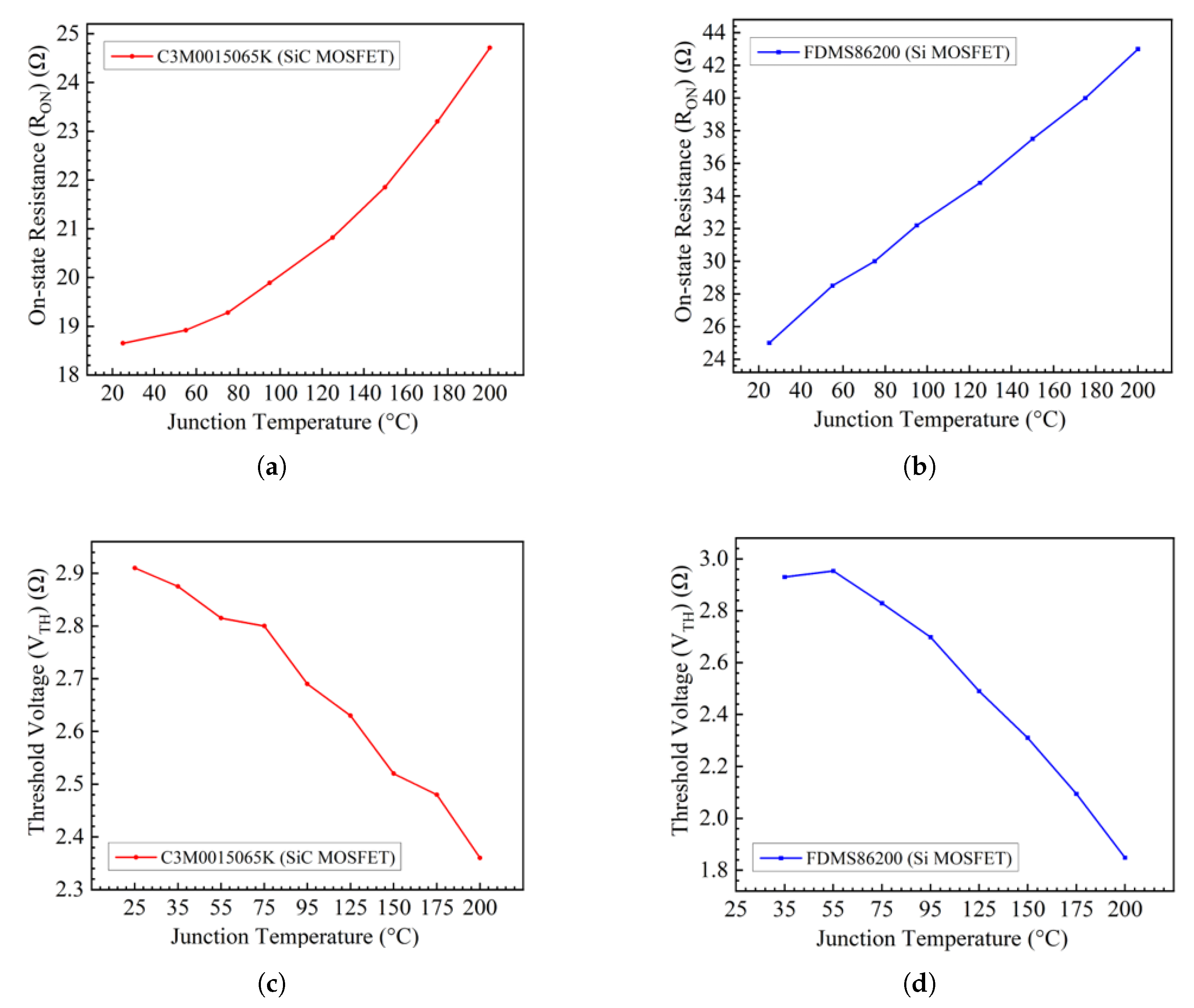

Figure 4. During testing, the device under test (DUT) was placed on a hot plate for 15 minutes to allow the junction temperature to stabilize at the target level. Also, other quasi-static parameters can be characterized as a function of temperature using the same set-up, enabling quantitative assessment of temperature-accelerated degradation.

The methodology for extracting

and

, as described in [

28], was applied at different temperatures in this work with the results shown in

Figure 5. The SiC MOSFET exhibited less variation in

compared to the Si MOSFETs, which can be attributed to the thermal conductivity of the SiC. In fact, it is worth noting that the radiation strategy also employs the B1505A for device calibration prior to irradiation [

24]. Moreover, a measurement setup similar to the temperature-accelerated degradation calibration can be used to characterize total ionizing dose (TID) effects, enabling assessment of both static and dynamic degradation [

29].

Figure 4.

Proposed simulation methodology with two strategies: thermal simulation and radiation simulation.

Figure 4.

Proposed simulation methodology with two strategies: thermal simulation and radiation simulation.

2.4. Radiation Simulation

In radiation strategy, experimental data is extracted and calculated from [

24] due to the lack of a radiation source. This approach provides valuable insights for application engineers to analyze device performance in harsh environments, which is discussed in detail below.

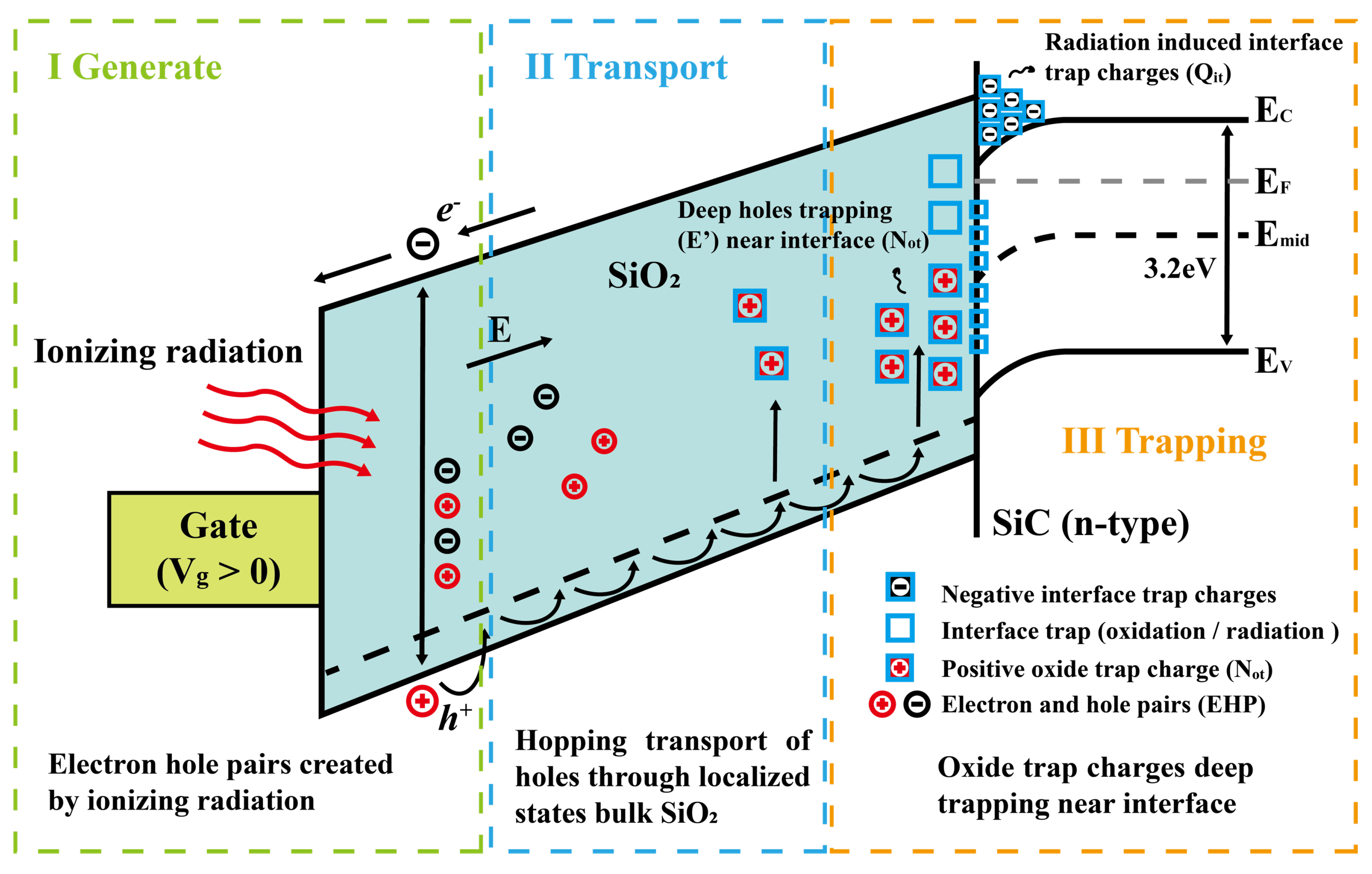

2.4.1. Physical Mechanism of SiC MOSFET Degradation

As previously mentioned, the

of SiC MOSFETs mainly depends on channel resistance, which is influenced by mobility and

. When a SiC MOSFET is exposed to gamma radiation, electron-hole pairs are generated in the gate oxide. Due to their high mobility, electrons are more likely to escape from the gate oxide, while holes become trapped within the gate oxide, leading to an accumulation of negative charges at the SiO

2/SiC interface. Thus, the accumulation of oxide trap charges following irradiation leads to greater inversion in the NMOS channel and a negative shift in threshold voltage. The mechanism of threshold voltage degradation in SiC MOSFETs is illustrated in

Figure 6.

To describe the TID irradiation-induced degradation of

, a model derived by [

24] can be applied:

where

q is the elementary charge,

is the number of generated electron–hole pairs,

is the gate oxide thickness,

is the fraction of positive oxide trap charges,

is the dielectric constant of oxide,

is the hole yield as a function of electric field and

Dose is the total ionizing dose in rads.

Under different bias conditions, the trapping effect results in varying degradation behavior due to the electric field. When the MOSFET is on, it operates under gate bias condition; when off, it operates under drain bias. Under gate bias, a high positive electric field is applied in the gate oxide above the channel region, while under drain bias, a comparatively lower negative electric field is present above the near-channel region. As a result, SiC MOSFETs exhibit greater sensitivity to gate bias during

-ray irradiation, particularly in terms of changes in

and

. In the simulation, SiC MOSFETs (C3M012090D) are used in [

24]. The extracted

and

under gate bias, as shown in

Table 2, are applied in the simulation.

In Equation (

4),

is proportional to the TIDs, the electric field in the gate oxide, and the oxide thickness. Given that the oxide layer in SiC MOSFETs is typically thicker than

nm, electrons have sufficient space to accelerate under the electric field, gaining more than

eV of energy. This energy allows them to collide with SiO

2 lattice atoms, generating electron–hole pairs [

30]. Due to the oxide thickness,

variation in planar SiC MOSFET is significantly smaller than in trench SiC MOSFETs at higher dose levels [

31,

32]. However, limited research compares planar gate and split-gate MOSFETs under high radiation doses. Based on Equation (

4), it can be inferred that the

variation in split-gate MOSFETs might be significantly smaller than that in planar MOSFETs, as the electric field in the gate oxide is much lower in split-gate designs.

2.4.2. Threshold Voltage Shift Induced by Oxide Traps

The

of SiC MOSFETs can be affected by radiation-induced oxide traps. The sensitivity of

depends on TIDs, and the electric field generated by trapped hole. In the experiment [

24], a negative shift of

and

was observed under

-ray irradiation. For worst-case assessment, the

shift caused by radiation-induced trapped charges should be evaluated together with the

shift induced by high-temperature gate bias (HTGB) under negative gate bias [

33].

When HTGB and TIDs are simultaneously applied, Zhang et al. [

34] observed a substantial shift in

. Therefore, although the

decreases under TIDs, the overall power consumption of power devices in harsh environment (with both high temperature and high radiation doses) increases, potentially reducing the efficiency of power applications. Unfortunately, limited research addressed the performance of power devices in application level under harsh environments, including online

measurements. Consequently, by experimentally characterizing parameter drifts under concurrent BTI and TID and integrating the extracted models into the proposed framework, the system-level impact on efficiency can be evaluated by using the proposed method.

3. Isolated Series Resonant Converter

In this paper, a galvanically isolated series resonant converter (SRC) topology is selected and designed. A brief introduction to the resonant converter is provided below.

3.1. Resonant Boost Converter Topology

The converter features a front-end full bridge and a boosting cell, connected through a galvanically isolated transformer [

7]. It offers significant advantages including reduced stress on the resonant capacitor, which regulates the output voltage, as well as a lower component count compared to the topologies in

Figure 1. The proposed converter can operate in four distinct modes, all based on discontinuous resonant current with a quality factor of less than one, irrespective of load conditions. The pure-SRC mode is employed solely in the simulation. The prototype developed for this study has a power rating of 300 W and achieves an output voltage of 355 V.

As a wide-input-range DC–DC resonant converter, this type is particularly suited for solar applications, especially in space solar applications. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the performance of the converter in harsh environments, such as high temperature and high radiation doses. In this paper, two strategies are proposed and implemented to simulate the power losses of the converter under these extreme conditions.

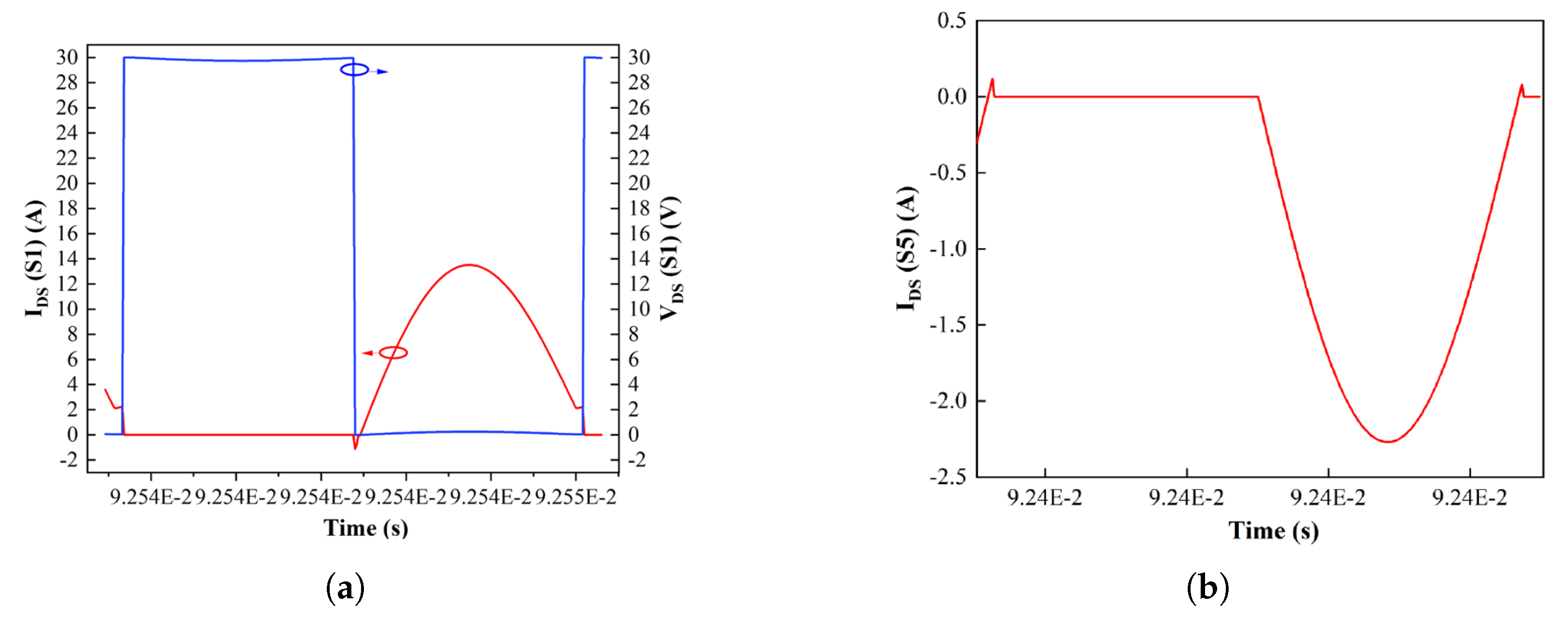

3.2. Zero Voltage Switching

To minimize turn-on switching losses, zero-voltage switching (ZVS) has been implemented in this topology. As a result, turn-on switching loss is negligible, and the turn-off loss is determined by the fall time. The turn-off voltage slew rate of the device is influenced by the gate-drive circuit design.

In the front-end full bridge, the transformer’s magnetizing inductance (

) serves as the current source during dead time. Thus, the magnetizing inductance should be designed such that the magnetizing current can fully charge and discharge the parasitic output capacitance of S1–S4, facilitating ZVS [

7].

Figure 7 shows the drain–source voltage (

) and drain current of S1 over one period, clearly demonstrating ZVS in this design. However, it is important that the magnetizing inductance of the transformer be designed according to the following criterion:

where

n is the transformer turns ratio,

is the dead time in the primary-side gate signals,

is the switching frequency of the power devices, and

is the parasitic output capacitance of the front-end full-bridge switches.

When designing a resonant converter, it is crucial to account for the switch parasitic. In addition to the output capacitance, parameters such as gate charge and the dynamic characteristics of the body diode must align with the circuit design. The proposed strategy provides an effective approach for analyzing how these device parameters interact with the circuit, thereby ensuring optimal performance.

4. Simulation Results and Reliability Analysis

4.1. Temperature-Sensitive Electrical Parameters (TSEPs)

Due to their excellent material characteristics, SiC MOSFETs can operate at extremely high temperatures and are suitable for harsh-environment applications. Various TSEPs of SiC MOSFETs, such as on-state resistance () and threshold voltage (), should be analyzed.

4.1.1. On-State Resistance ()

Gate-oxide degradation and total

are critical aging indicators for SiC MOSFETs. In both typical planar MOSFET and trench MOSFET shown in

Figure 1, the total

is obtained by summing the individual resistances of each layer and region, which can be represented as:

Here,

is the channel resistance,

is the source region resistance,

is the resistance of the JFET region (Junction Field-Effect Transistor), and

,

, and

represent the accumulation resistance, the resistance of the drift region, and the

substrate resistance, respectively.

is the source contact resistance, while

is the drain contact resistance. However, the dominant contributors to

is different between Si MOSFETs and SiC MOSFETs (1.2 kV planar MOSFET). In Si MOSFETs,

and

are the primary contributors due to lower breakdown electric-field strength and thicker drift layer. In contrast,

is a major contributor to

in SiC MOSFETs because of lower inversion carrier mobility at the SiO

2/SiC interface [

35,

36]. Therefore, excluding the

, the rest of the resistances can be defined as the residual resistance (

). The total

is the sum of the

and

, where the contribution of channel resistance

is given by [

37]:

where

is the channel length,

P is the pitch of the MOSFET elementary cell,

is the electron mobility in the inversion layer,

is the specific gate-oxide capacitance,

is the applied gate voltage, and

is the threshold voltage.

In [

38], it is noted that

and

exhibit a positive temperature coefficient (PTC), while

displays a negative temperature coefficient (NTC). As previously discussed,

is the primary contributor to

in SiC MOSFETs. Thus, the temperature sensitivity of

in SiC MOSFETs is less significant than in Si MOSFETs as illustrated in

Figure 5. The normalized

of the SiC MOSFET shows smaller change than that of the Si MOSFET as the junction temperature increases. Although

has an NTC characteristic, the total

still increases with rising junction temperature due to

, which exhibits a PTC [

36,

42]. As a result, the overall

of SiC MOSFET remains PTC. Nevertheless, the stability of

in SiC MOSFETs is superior to that of Si MOSFETs under varying temperatures. At a high temperature up to 375 °C,

no longer dominates

; instead,

and

in

become more influential as the temperature increases [

40].

4.1.2. Threshold Voltage ()

As discussed in Section II,

is a radiation-sensitive parameter that tends to shift negatively during gamma-ray radiation. However, it is also sensitive to temperature changes. The threshold voltage of the SiC MOSFET can be expressed as follows [

40]:

where

is the dielectric constant of SiC,

q is the electronic charge,

is the doping concentration of the P-base region,

is the flat-band voltage,

is the Fermi potential from the substrate, and

is the interface state density. Notably, the commercial devices chosen from CREE have shown improvements in the SiO

2/SiC interface [

41]. With the reduction of near-interface traps (NITs), the stability of

performs well under high temperatures. The rate of variation of

with temperature can be expressed as follows [

42]:

where

T is temperature,

is the work function difference between the metal and the semiconductor at the gate and substrate, and

is the number of traps between the neutral level and the conduction band. The temperature dependence of

is determined by the

,

and

. Specifically,

decreases with increasing temperature due to the rise of intrinsic carrier concentration. Additionally,

also decreases with temperature as the Fermi level energy (

) shifts toward the mid-gap, which reduces the occupancy of electrons in the interface traps. In general, the

of SiC MOSFETs shows a negative shift characteristic as the temperature increases.

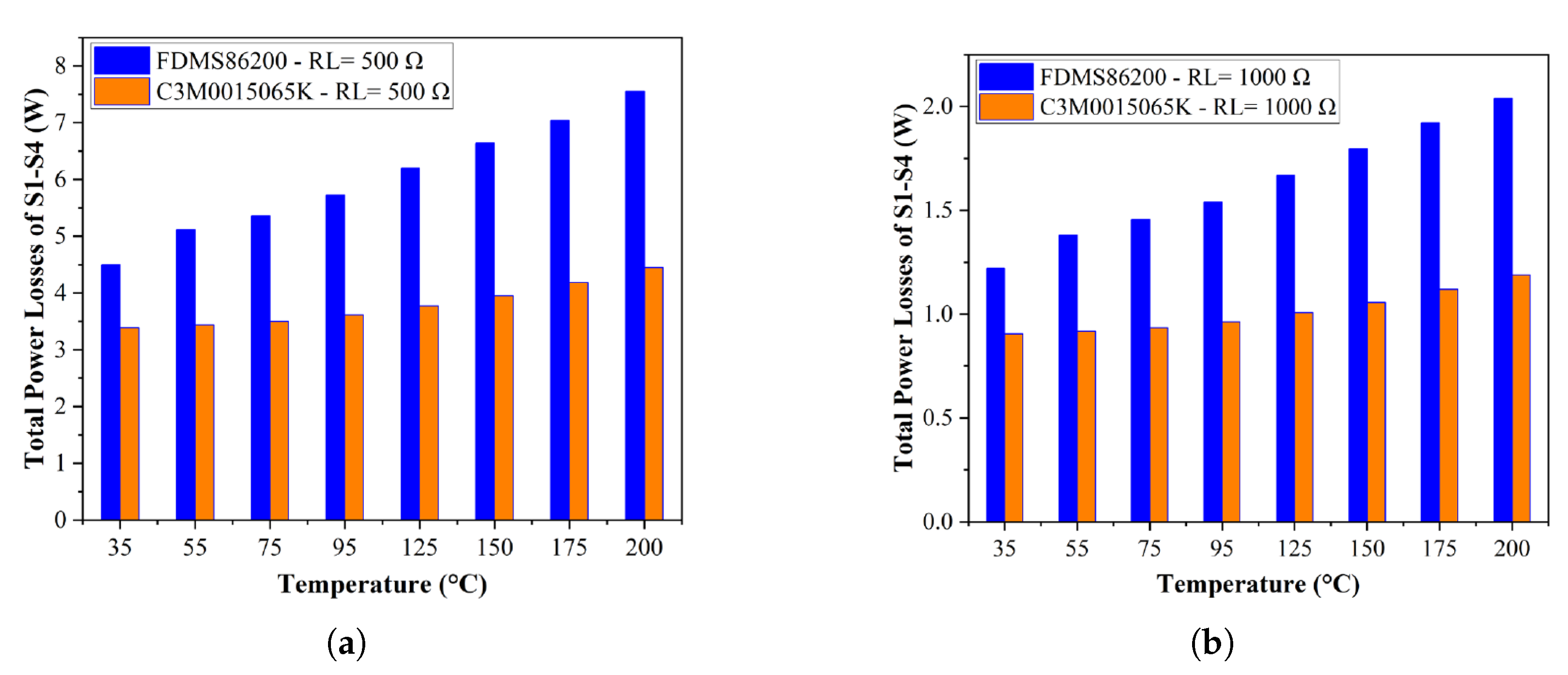

4.2. Thermal Simulation Results

It is important to note that the switching loss for each MOSFET is only an estimate. In the simulation, both the external turn-on and turn-off resistances are set to , with other parameters shown in Table II, which correspond to the switching loss in PSIM thermal model as discussed in Section II.

In the thermal strategy, the conduction losses of power devices in the front-end full bridge are primarily analyzed to compare the power consumption stability between Si and SiC MOSFETs, which can affect the power converter reliability. As shown in

Figure 8, the change in total power conduction losses for SiC MOSFETs is less pronounced than for Si MOSFETs as temperature increases. At a 40.8% load (

), the variation in

for SiC MOSFETs is only 26%, compared to a significantly higher 67.7% for Si MOSFETs. Similarly, at an 81% load (

), the variation in

for SiC MOSFETs is just 21%, while for Si MOSFETs, it remains significantly higher at 67%.

In summary, the power loss stability of the Si-based resonant converter is lower than that of the SiC-based resonant converter, primarily due to the superior stability of SiC under high temperatures. However, it is important to emphasize that the switching performance discussed is only an estimate and depends on the gate driver design. As previously noted, the switch’s fall time significantly affects switching performance, especially when achieving ZVS. SiC devices, with their high and characteristics, enable faster turn-on and turn-off speeds compared to Si devices. The key consideration is the tradeoff involving overshoot. In low input voltage scenarios, the overshoot voltage remains below the breakdown voltage, reducing potential risks. Therefore, SiC MOSFETs in today’s technology are more adaptable to harsh environments, even in low-power applications.

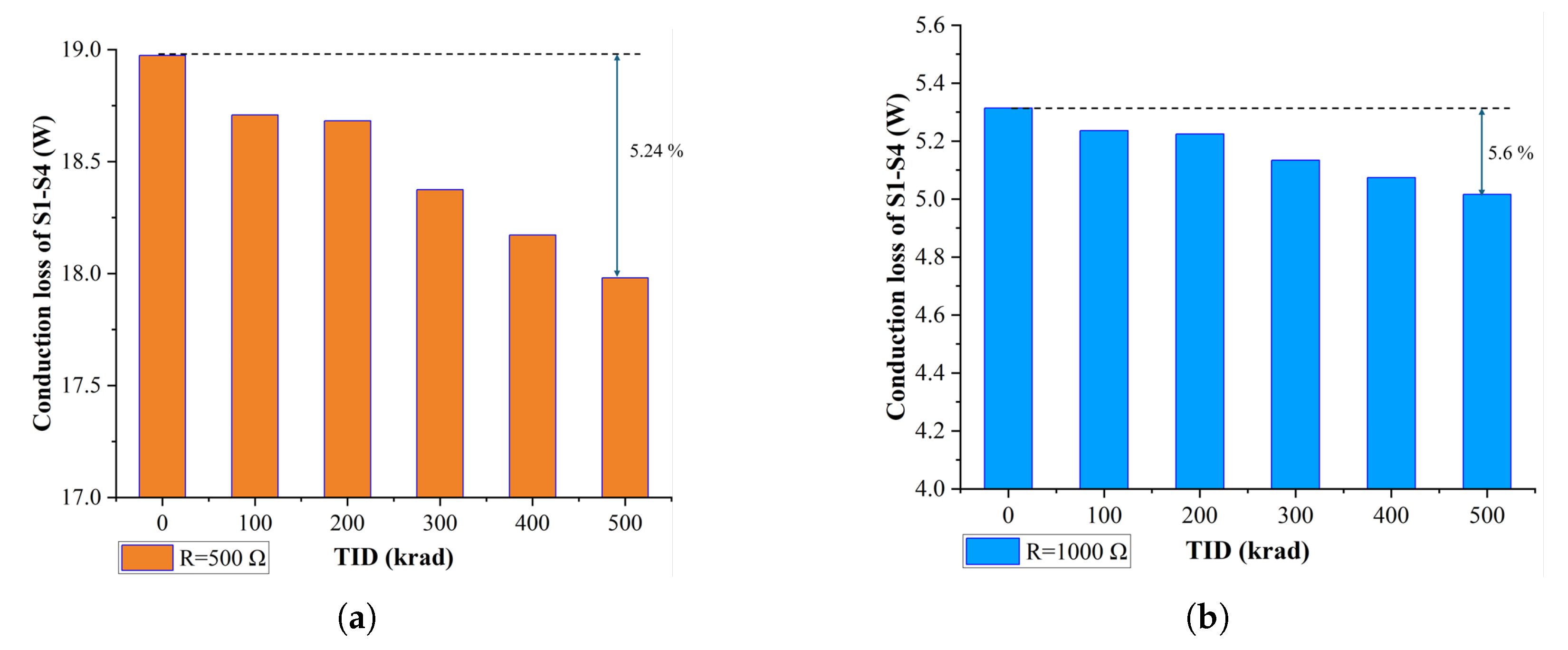

4.3. Radiation Simulation Results and Analysis

The radiation simulation results shown in

Figure 9 indicate that SiC MOSFETs experience a decrease in

as the TID increases from 0 to 500 krad, with a 5.24% reduction noted at a load resistance of

. While this reduction in

may initially appear beneficial due to the resulting lower power conduction losses, the threshold voltage shift observed under gamma-ray irradiation raises more significant concerns regarding long-term reliability. A negative shift in

implies that the MOSFET can turn on more easily, which increases the risk of unintended switching in the presence of noise, ultimately compromising circuit performance and reliability. Furthermore, as the load decreases (e.g., at

), the overall power conduction losses continue to decrease further, but the impact on

remains considerable. The accumulation of trapped charges in the gate oxide causes a more permanent degradation of

, potentially leading to device failure after prolonged operation under radiation. While the decrease in

contributes to lower conduction losses, this trade-off compromises long-term device reliability. In addition, the negative shift in

increases the device’s sensitivity to environmental noise, which poses a significant risk in space applications where long-term reliability is critical.

The combined effects of radiation exposure, high temperature, and prolonged operation must be analyzed in system-level design. A simulation-based method can aid in predicting potential issues that may arise in real experiments. For instance, the permanent degradation of and the alterations in could lead to catastrophic device failure, resulting in simulation that fails to accurately replicate real-life conditions.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a simulation methodology that integrates thermal and radiation strategies within the PSIM thermal-modeling framework. In the thermal strategy, device calibration is performed using a B1505A curve tracer to correct deviations between datasheet and measured transfer characteristics. Simulation results indicate that the SiC-based resonant converter exhibits greater power-loss stability than its Si-based counterpart at elevated temperatures. In the radiation strategy, experimental data are used to simulate power losses in the resonant converter under total-ionizing-doses (TIDs) condition. Gate-oxide degradation and threshold-voltage instability are observed under high gamma irradiation. Although conduction losses may decrease under certain load conditions, increasing TID still induces permanent threshold voltage shift, degrading device reliability and system-level performance of the converter.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and Z.C.; methodology, Q.L., Z.C., and Z.F.; software, Z.F., A.A., and F.F.; validation, Z.F., P.L., F.F and A.H.; formal experiment and analysis, Z.F.; investigation, Z.F., F.F., A.A., L.H., Z.C., and Q.L.; resources, Z.C. and Q.L.; data curation, Z.F., P.L., F.F., and A.H.; writing—original draft, Z.F.; writing—review and editing, Z.F., Z.C. and Q.L.; visualization, Z.F. and F.F.; supervision, Q.L., Z.C., and L.H.; project administration, Q.L., L.H. and Z.C.; funding acquisition, Q.L. and Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available and can be shared upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- N. Altin et al., “A novel topology for solar PV inverter based on an LLC resonant converter with optimal frequency and phase-shift control,” IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 5042–5054, 2022.

- M. Parvez et al., “Wide bandgap DC–DC converter topologies for power applications,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 109, no. 7, pp. 1253–1275, 2021.

- T. LaBella, W. Yu, J.-S. Lai, M. Senesky, and D. Anderson, “A bidirectional-switch-based wide-input range high-efficiency isolated resonant converter for photovoltaic applications,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 29, no. 7, pp. 3473–3484, Jul. 2014.

- X. Zhao, L. Zhang, R. Born, and J.-S. Lai, “A high-efficiency hybrid resonant converter with wide-input regulation for photovoltaic applications,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 3684–3695, May 2017.

- S. Kim, B. Kim, B.-H. Kwon, and M. Kim, “An active voltage-doubler rectifier based hybrid resonant DC/DC converter for wide-input-range thermoelectric power generation,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 33, no. 11, pp. 9470–9481, Nov. 2018.

- X. Zhao, C.-W. Chen, and J.-S. Lai, “A high-efficiency active-boost-rectifier-based converter with a novel double-pulse duty cycle modulation for PV to DC microgrid applications,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 7462–7473, Aug. 2019.

- A. Bakeer et al., “Wide range series resonant DC–DC converter with a reduced component count and capacitor voltage stress for distributed generation,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 8, p. 2051, 2021.

- V. Sidorov, A. Chub, and D. Vinnikov, “Bidirectional isolated hexamode DC–DC converter,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 37, no. 10, pp. 12264–12278, Oct. 2022.

- S. Liang et al., “Modeling irradiation-induced degradation for 4H-SiC power MOSFETs,” IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 1176–1180, Mar. 2023.

- S. Liang et al., “Dynamic degradation of planar-gate SiC MOSFETs after total ionizing dose radiation,” IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, vol. 71, no. 7, pp. 4079–4086, Jul. 2024.

- C. Peng et al., “Bias and temperature dependence of radiation-induced degradation for SiC MOSFETs,” IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci., vol. 71, no. 5, pp. 1186–1193, May 2024.

- E. Ugur et al., “Degradation assessment and precursor identification for SiC MOSFETs under high temperature cycling,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 2858–2867, May–Jun. 2019.

- H. Farooq et al., “A comparative analysis of half-bridge LLC resonant converters using Si and SiC MOSFETs,” Engineering Proceedings, vol. 12, p. 43, 2021.

- S. A. Syed et al., “Analytical and simulation comparison of losses in non-isolated DC–DC converter using Si and SiC switches for PV application,” Engineering Proceedings, vol. 20, p. 11, 2022.

- H. Farooq et al., “Efficiency analysis of GaN-based LLC resonant converter for PV applications,” Engineering Proceedings, vol. 20, p. 31, 2022.

- F. Pellitteri et al., “Power losses comparison between silicon carbide and silicon devices for an isolated DC–DC converter,” in Proc. IEEE 15th Int. Conf. on Compatibility, Power Electronics and Power Engineering (CPE-POWERENG), 2021.

- A. U. Rashid et al., “An efficient electro-thermal compact model of SiC power MOSFETs including third quadrant behavior,” IEEE Open Journal of Power Electronics, vol. 3, pp. 348–367, 2022.

- H. A. Mantooth et al., “Modeling of wide bandgap power semiconductor devices—Part I,” IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 423–433, 2014.

- A. U. Rashid et al., “Datasheet-driven compact model of silicon carbide power MOSFET including third-quadrant behavior,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 36, no. 10, pp. 11748–11762, 2021.

- B. W. Nelson et al., “Computational efficiency analysis of SiC MOSFET models in SPICE: Dynamic behavior,” IEEE Open Journal of Power Electronics, vol. 2, pp. 106–123, 2021.

- S. Pu et al., “Aging mechanisms and accelerated lifetime tests for SiC MOSFETs: An overview,” IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1232–1254, 2021.

- Z. Ni et al., “Review of SiC MOSFET based three-phase inverter lifetime prediction,” in Proc. 2017 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conf. and Exposition (APEC), IEEE, 2017.

- F. Pellitteri et al., “Power losses comparison between Silicon Carbide and Silicon devices for an isolated DC–DC converter,” in Proc. 2021 IEEE 15th Int. Conf. on Compatibility, Power Electronics and Power Engineering (CPE–POWERENG), IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–6.

- S. Liang et al., “Modeling irradiation-induced degradation for 4H-SiC power MOSFETs,” IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 1176–1180, 2023.

- J. Ortiz-Gonzalez, O. Alatise, S. Ali, and P. Mawby, “Performance and reliability review of 650 V and 900 V silicon and SiC devices: MOSFETs, cascode JFETs and IGBTs,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 67, no. 9, pp. 7375–7385, 2019.

- J. Ortiz-Gonzalez, O. Alatise, and P. A. Mawby, “An investigation of temperature-sensitive electrical parameters for SiC power MOSFETs,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 7954–7966, 2016.

- J. Ortiz-Gonzalez and O. Alatise, “Impact of BTI-induced threshold voltage shifts in shoot-through currents from crosstalk in SiC MOSFETs,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 3279–3291, 2020.

- S. Yin et al., “An accurate subcircuit model of SiC half-bridge module for switching-loss optimization,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 3840–3848, Jul.–Aug. 2017.

- S. Liang et al., “Investigation on dynamic degradation of SiC MOSFETs after total ionizing dose radiation,” in Proc. IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), 2023, pp. 1–6.

- X. Liang et al., “Study of the influence of gamma irradiation on long-term reliability of SiC MOSFET,” Radiation Effects and Defects in Solids, vol. 175, no. 5–6, pp. 559–566, 2020.

- R. Luo et al., “Total ionizing effects on static characteristics of 1200 V SiC MOSFET power devices with planar and trench structures,” in Proc. 20th China Int. Forum on Solid State Lighting & 9th Int. Forum on Wide Bandgap Semiconductors (SSLCHINA: IFWS), 2023, IEEE.

- L. Shu et al., “Comparison of gamma irradiation effects on short circuit characteristics of SiC MOSFET power devices between planar and trench structures,” Electronics, vol. 12, no. 13, p. 2891, 2023.

- Q. Yu et al., “Application of Total Ionizing Dose Radiation Test Standards to SiC MOSFETs,” IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science, vol. 69, no. 5, pp. 1127–1133, 2021.

- T. Zhang, B. Allard, and J. Bi, “The synergetic effects of high temperature gate bias and total ionization dose on 1.2 kV SiC devices,” Microelectronics Reliability, vol. 88, pp. 631–635, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Baliga, Fundamentals of Power Semiconductor Devices. Springer, 2010.

- Z. Zhao, P. Wang, and T. Chen, “A gate degradation–independent online junction temperature estimation method for SiC MOSFETs based on residual resistance,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., early access, 2024.

- M. Farhadi, M. Najjar, M. M. H. Kiani, and A. Emami, “Temperature-independent gate-oxide degradation monitoring of SiC MOSFETs based on junction capacitances,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 8308–8324, 2021.

- G. Wang et al., “Dynamic and static behavior of packaged silicon carbide MOSFETs in paralleled applications,” in Proc. IEEE Appl. Power Electron. Conf. and Exposition (APEC), 2014.

- X. Jiang et al., “Online junction temperature measurement for SiC MOSFET based on dynamic threshold voltage extraction,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 3757–3768, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Lu et al., “Investigation and comparison of temperature-sensitive electrical parameters of SiC MOSFET at extremely high temperatures,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 38, no. 8, pp. 9660–9672, Aug. 2023.

- F. Jiang et al., “Comparative study of temperature-dependent characteristics for SiC MOSFETs,” in 13th China Int. Forum on Solid State Lighting: Int. Forum on Wide Bandgap Semiconductors China (SSLChina: IFWS), Beijing, China, 2016, pp. 50–53.

- X. Jiang et al., “Online junction temperature measurement for SiC MOSFET based on dynamic threshold voltage extraction,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 3757–3768, Apr. 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).