1. Introduction

During the pyrometallurgical refining of copper, the anode furnace employs an oxidation and reduction process successively to deeply purify crude copper. During the reduction period in anode furnace, the reducing agent reduces copper oxides to form elemental copper. At present, some copper smelters utilize CH

4, H

2 as reducing agents [

1,

2], but many still use coal due to the resource limitation [

3,

4]. The mixing and reactivity between coal and copper liquid are poor, and thus the reaction rate is relatively low [

5]. Therefore, an excessive amount of reducing agent must be added to ensure the reduction process being completed within the specified processing time, to avoid affect the continuity of the overall production process. This results in a large amount of coal particles in the molten pool not participating in the effective reduction reaction, causing material wastage and pollutant emission. In addition, coal particles will float to the surface of the copper liquid after being partly reacted. With this and the introduced or in-leaking air, substantial amounts of carbon monoxide would be generated, seriously hindering the downstream utilization of the high-concentrations sulfur dioxide (commonly used for producing sulfuric acid or sulphur) in the flue gas [

6].

These problems can be alleviated theoretically by adjusting the operating parameters of anode furnace refining process. For example, changing the bottom and side injection air volumes, the distribution position of the bottom-blowing lances, and the insertion depth of the side-blowing lances in the anode furnace could enhance the mixing between coal and copper liquid and effectively reduce coal consumption [

7,

8]. However, the effect on CO concentration reduction in flue gas is limited, and generally cannot meet the requirements of the downstream sulfuric acid plant. In comparison, consuming the generated CO is a more feasible approach to reducing pollution emissions and thereby ensuring the utilization of SO

2. Furthermore, burning CO to assist in recovering released heat can enhance the system’s economic efficiency. Therefore, to thoroughly solve the high-concentration CO in the flue gas from anode furnace, this study proposes a method of adding air distribution in the downstream combustion chamber of the anode furnace to convert the high-concentration CO into CO

2 through combustion.

To guarantee sufficient oxidation of CO in this process, it is imperative to ensure the provision of oxidant and temperature. To determine the oxidant required for the reaction, it is first necessary to obtain the accurate total flue gas flow rate and CO concentration. However, an issue of air leakage has been identified upstream of the tail flue gas outlet, thereby precluding the estimation of the total flue gas flow rate and CO concentration based on the inlet process air and other conditions. It is difficult to test the flue gas flow rate on-site, while measuring the CO concentration is relatively easier. To overcome this issue, theoretical calculation method is a feasible approach. Based on the operating parameters of the anode furnace, and the supplementary air volume is obtained under different indicators of CO concentration.

The combustion of carbon monoxide is fundamentally governed by temperature, requiring the attainment of a specific threshold to initiate the oxidation process [

9]. This process, however, is also influenced by the complex gas atmosphere present in practical industrial environments. Key components in anode furnace flue gas like H

2O and CO

2 could participate in and influence the fundamental radical chemistry that dictates the oxidation pathway of CO [

10]. While the pivotal role of OH radicals in oxidizing CO is well-established [

11,

12,

13], the net impact of adding H

2O under specific industrial conditions remains ambiguous. For instance, although H

2O can generally enhance radical generation, its excessive presence has been reported to suppress CO oxidation through mechanisms such as radical recombination and system cooling [

14,

15,

16]. This presents a significant scientific and practical challenge: how to quantitatively delineate the dual role of H

2O and other flue gas components.

Beyond the influence of H

2O on CO oxidation, it is also necessary to consider CO

2, another major component in the flue gas. As the product of CO oxidation, CO

2 could inhibit the combination of CO and OH radicals [

17]. The presence of CO

2 leads to a decrease in the CO conversion rate [

18]. However, the above studies are not aimed at CO combustion but at hydrocarbon fuels, in which CO is an intermediate product. At present, the research on the oxidation reactivity of CO fuel in a complex atmosphere is still limited. The presence of high-concentration CO

2 and H

2O in the flue gas, located at the terminal point of the anode furnace, exerts a discernible influence on the combustion of CO. Therefore, systematically investigating the effects of temperature and key gas compositions specifically H

2O and CO

2 on CO oxidation is imperative to resolve these contradictions and to provide a scientific basis for optimizing combustion processes in industrial applications.

It has been established that the temperature of the flue gas emanating from the anode furnace may be inadequate when it traverses the downstream combustion chamber. On the other hand, there is pure O

2 accessible on-site, which provides a potential for CO oxidation promotion at these moderate temperature via adding some O

2 to air [

19,

20]. Capitalizing on the accessibility of on-site oxygen, this work investigates the efficacy of oxygen enrichment as a means to promote CO combustion. This approach aligns perfectly with copper smelters’ existing pure oxygen injection capabilities, providing an empirically validated strategy that bridges combustion science with industrial practice. Since the practical outcome of this intervention is contingent upon several factors, a detailed experimental inquiry was conducted to unravel the interplay of temperature, CO

2 dilution, and O

2 concentration. This research could elucidate the underlying mechanisms and provides copper smelters with an evidence-based protocol for minimizing CO emissions, bridging the gap between plant feasibility and proven combustion science.

2. Theoretical Calculation of Flue Gas Flow Rate and Co Combustion Experiment

2.1. Theoretical Calculation Parameters

The proximate analysis and ultimate analysis of the reducing agent and the important components content in the anode furnace flue gas is presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively. The core of the reduction stage in the anode furnace is to reduce the residual Cu

2O formed in the oxidation process, to decrease the oxygen content in copper liquid below a limit value, which could lay a foundation for subsequent electrolytic refining. The detailed process and principle, combined with specific operating parameters, are explained as follows:

This reduction stage operates on 160,000 kg copper liquid, which has been partly oxidized to Cu2O (~5% in the total copper liquid) in the oxidation process, and with the total reduction duration controlled at 60-80 min. To achieve efficient reduction of Cu2O, an accurate dosage of 1,500 kg of reducing agent must be added. Through the redox reaction between the reducing agent and Cu2O, copper oxide is reduced to metallic copper while preventing the introduction of new impurities. During the operation of the anode furnace, fuel oil is supplied at a rate of 70 kg/h to maintain the appropriate reaction temperature inside the furnace at 1280-1320 ℃, ensuring the thermodynamic conditions required for the reduction reaction. Meanwhile, oxygen supply at 210 kg/h and processing air at 900 Nm3/h work synergistically to regulate the furnace atmosphere. This not only supports fuel combustion but also cooperates with the rotary stirring of the furnace body to ensure full contact between the reducing agent and the copper melt, thereby improving reaction uniformity.

Based on the law of conservation of elements (C, O), the amount of oxidant added is verified to guide the on-site reduction of CO concentration.

2.2. Experimental System and Methods

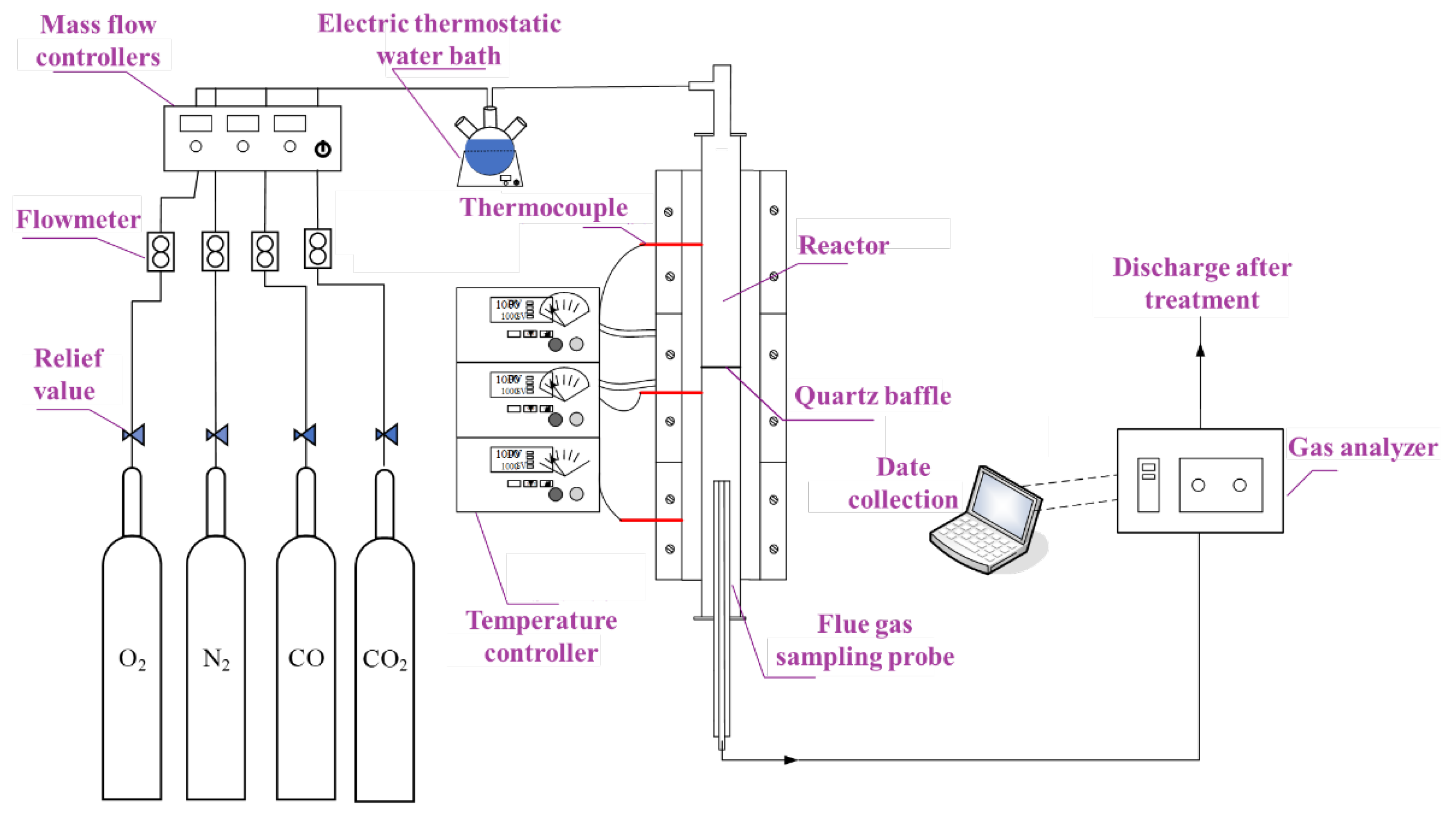

To test the combustion characteristic of CO in flue gas, a dedicated experimental system was constructed, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The system comprises three primary subsystems: a gas distribution system, a heating system, and a flue gas analysis system.

The gas distribution system supplies precise gas mixtures and is equipped with cylinders for the required gases, along with corresponding pressure-reducing valves and mass flow controllers. Water vapor, generated by an electric thermostatic water bath, is introduced as a reactant. To prevent its condensation during transport into the quartz tube reactor, the vapor line is trace-heated using heating tape regulated by a temperature controller.

A quartz tube reactor, with length of 900 mm and inner diameter of 24 mm serves as the core reaction vessel housed within the furnace. The heating system is built around the vertical tube furnace, which is capable of achieving a theoretical temperature of up to 1473 K in the reaction zone. Temperature regulation is accomplished through a thermocouple that monitors the furnace temperature in real time and is coupled with an automatic temperature controller to ensure precise thermal management.

The flue gas analysis system is responsible for the online monitoring and quantification of gas concentrations. It primarily consists of a Testo 350 flue gas analyzer, whose measurement accuracy has been verified to fully meet the requirements of this experiment study.

The experimental procedure involved a systematic sequence of setup, execution, and measurement. Initially, all devices were energized, and the gas analyzer was calibrated. The gas delivery system then supplied the reactants through a network of pressure regulators, mass flow controllers, and connecting tubing to the quartz tube reactor. During combustion, the Testo 350 flue gas analyzer continuously sampled the effluent from the reactor outlet. The analyzed data, specifically the residual CO concentration in the tail gas and the CO burnout temperature, were subsequently used to quantitatively determine the effects of key variables, including temperature O2 content and CO2 content on the combustion characteristics of CO.

In view of the large amount of CO contained in flue gas during the operation of the anode furnace, the combustion characteristics of CO in the temperature range of 300-800 °C was studied experimentally. To treat the CO in the tail gas, it is considered to increase the oxygen concentration to promote combustion. At the same time, the composition of the anode furnace flue gas is relatively complex, which also contains CO2, H2O, and other components. Therefore, experiments are needed to explore the effects of temperature, oxygen content, and other factors on the combustion characteristics of CO under the complex atmosphere conditions of the anode furnace. The experimental conditions were designed to simulate the tail flue gas environment of an industrial anode furnace. Based on typical operational data, the simulated gas mixture, with a total flow rate of 1 L/min, contained 2816.8 μl/L CO, 17.58% O2, and 6.09% CO2, balanced with N2. This composition accurately reflects the fluctuating conditions after copper refining, ensuring high experimental relevance.

Building upon this baseline composition, a series of controlled experiments were conducted by systematically varying key operational parameters. The reaction temperature was investigated across a range from 500 °C to 800 °C to capture the complete profile from CO oxidation initiation to its complete burnout. Furthermore, the O2 concentration was adjusted from the baseline of 17.58% up to 51% to quantitatively assess the promoting effect of oxygen enrichment. The influence of steam was examined by introducing 2.5% H2O into the mixture. This matrix of conditions was specifically designed to isolate and elucidate the individual and synergistic effects of temperature, oxygen content, and the presence of other flue gas components on the combustion characteristics of CO.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determination of Flue Gas Flow Rate

The oxygen content in the copper liquid during the reduction stage of the anode furnace is 0.6%. Based on the law of mass conservation of copper and oxygen, the variation of oxygen content can be described as follows:

Thus, the amount of C required to consume the O amount can be calculated as 25000 mol, and the amount of coal consumed is 480.08 kg. The remaining amount of the reducing agent is 1019.92 kg, and the utilization rate of the reducing agent is 32.01%.

The flue gas volume in the anode furnace is mainly composed of the flue gas volume generated by fuel oil, the flue gas volume generated by reducing blister copper, and the flue gas volume generated by process air reduction and the remaining process air volume. After calculation, the flue gas volume generated by fuel oil is 796.07 m3, the flue gas volume generated by reducing blister copper is 558.38 m3, the oxygen content in the process air is 270.27 kg, and the flue gas volume under the process air (reduction and process air) is 711 m3.

Based on the on-site operation rules and actual data of the anode furnace, theoretical calculations are carried out for the tail flue gas to obtain the accurate total flue gas flow rate and CO component. Assuming the air leakage volume is Z m

3, the oxygen content in the air leakage volume can be calculated as 0.21Z m

3,the variation of oxygen content can be described as follows:

Based on the on-site measured CO and O2 concentrations inside and at the outlet of the anode furnace, and in accordance with the law of conservation of elements (C, O), the supplementary air volume is verified to guide the on-site reduction of CO concentration. Assuming the amount of CO is X mol and CO2 is Y mol, according to the law of conservation of elements, the equilibrium equations are as follows:

X=30359; Y=47754; Z=4485.5

After verification, the error is less than 0.1%. Similarly, the changes in various parameters when the CO proportion is 3% and 7% can be obtained. In the theoretical calculation parameters of the anode furnace flue gas volume, the total flue gas volume, air leakage volume, and supplementary air volume show dynamic changes with the CO proportion. When the total flue gas volume of the anode furnace is 7637.3 m3, 7135.5 m3, and 6800.3 m3, the CO proportion in the total flue gas volume is 3%, 7%, and 10%, respectively. The air leakage volume is 5545.0 m3m3, 4909.8 m3, and 4485.5 m3, respectively. Furthermore, it can be known that the required supplementary air volumes are 545.1 m3, 1188.4 m3, and 1617.9 m3, respectively. Figure 2 shows the variation law of the required supplementary air volume when the CO proportion in the total flue gas volume is 3-10% considering air leakage.

Based on the on-site investigation of the basic situation of the anode furnace for refining copper, the operating parameters of the anode furnace are obtained, and the CO concentration distribution under multiple operating conditions at different positions inside the anode furnace is measured on-site. The remaining reducing agent is calculated according to the amount of reducing agent at the inlet and the oxygen content in the copper liquid, and then the flue gas volume is calculated combined with the process air volume, CO concentration, and other inlet conditions. The supplementary air volume of the tail combustion chamber is verified, which provides effective guidance for the actual production operation.

3.2. Effect of H2o on Co Burnout

Since combustion processes in reality almost never occur in the complete absence of H

2O, and as evidenced by the previously obtained data, the influence of H

2O on the CO oxidation process cannot be neglected, 2.5% steam by volume was introduced into the total gas flow to investigate its effect on CO oxidation.

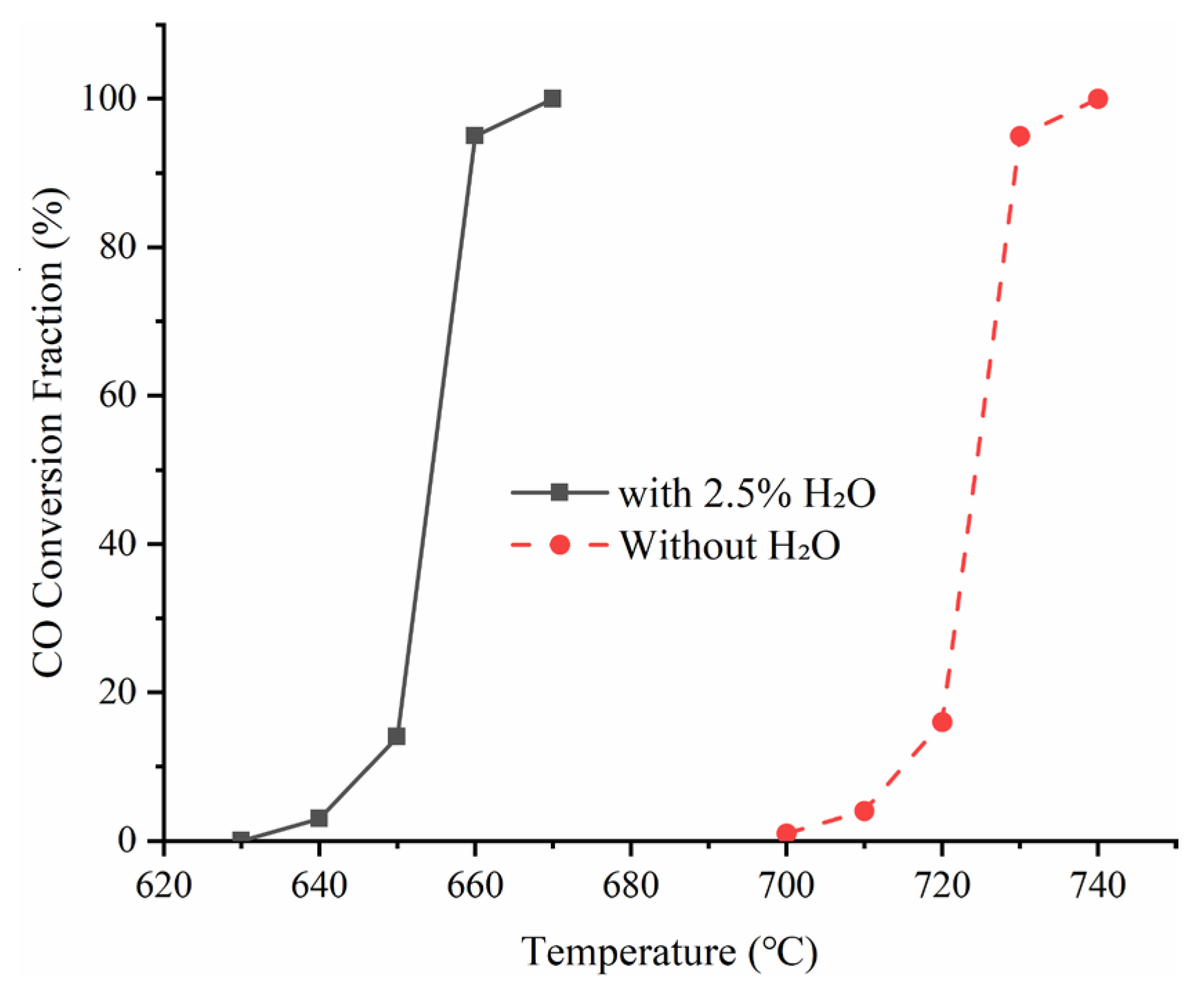

Figure 3 presents a comparison of the CO conversion profiles with and without the presence of H

2O. Our experimental results demonstrate a clear promoting effect of moderate H

2O addition on CO oxidation. Within the temperature range of 650–700 °C, the introduction of 2.5% H

2O significantly increased the CO oxidation rate and reduced its ignition temperature.

A more direct approach to evaluate the effect of H

2O addition on the oxidation reaction is to compare the measured ignition temperature and T

50 (temperature at 50% conversion). As summarized in

Table 3, the presence of steam significantly promotes both CO ignition and conversion, reducing the ignition temperature and T

50 by approximately 70 °C. The measured ignition temperature of moist CO in this study is consistent with previously reported values in the literature [

21,

23].

It is widely accepted in current kinetic models that Reaction R3, which involves the OH radical, constitutes the dominant pathway for CO oxidation in the presence of H

2O [

24]. Reaction path analysis confirmed that this enhancement is primarily attributable to the enrichment of the OH radical pool, driven by the chain-branching reaction R1 and R2. When 2.5% H

2O is present, Reaction R3 is the dominant pathway, responsible for 75.2% of the total CO oxidation rate. In contrast, the direct reaction between CO and O represents only a minor path, contributing a mere 13.5% [

24].

However, consistent with the literature [

25], a non-linear relationship was observed. It should be noted that certain studies [

13,

14] observed an inhibitory effect of H

2O on CO oxidation, as the H

2O concentration increased beyond an optimal point, the CO oxidation rate began to decline. This phenomenon is likely linked to the dual role of H

2O: at high concentrations, it promotes radical termination reactions R4 and may also contribute to thermal quenching [

14,

15,

16].

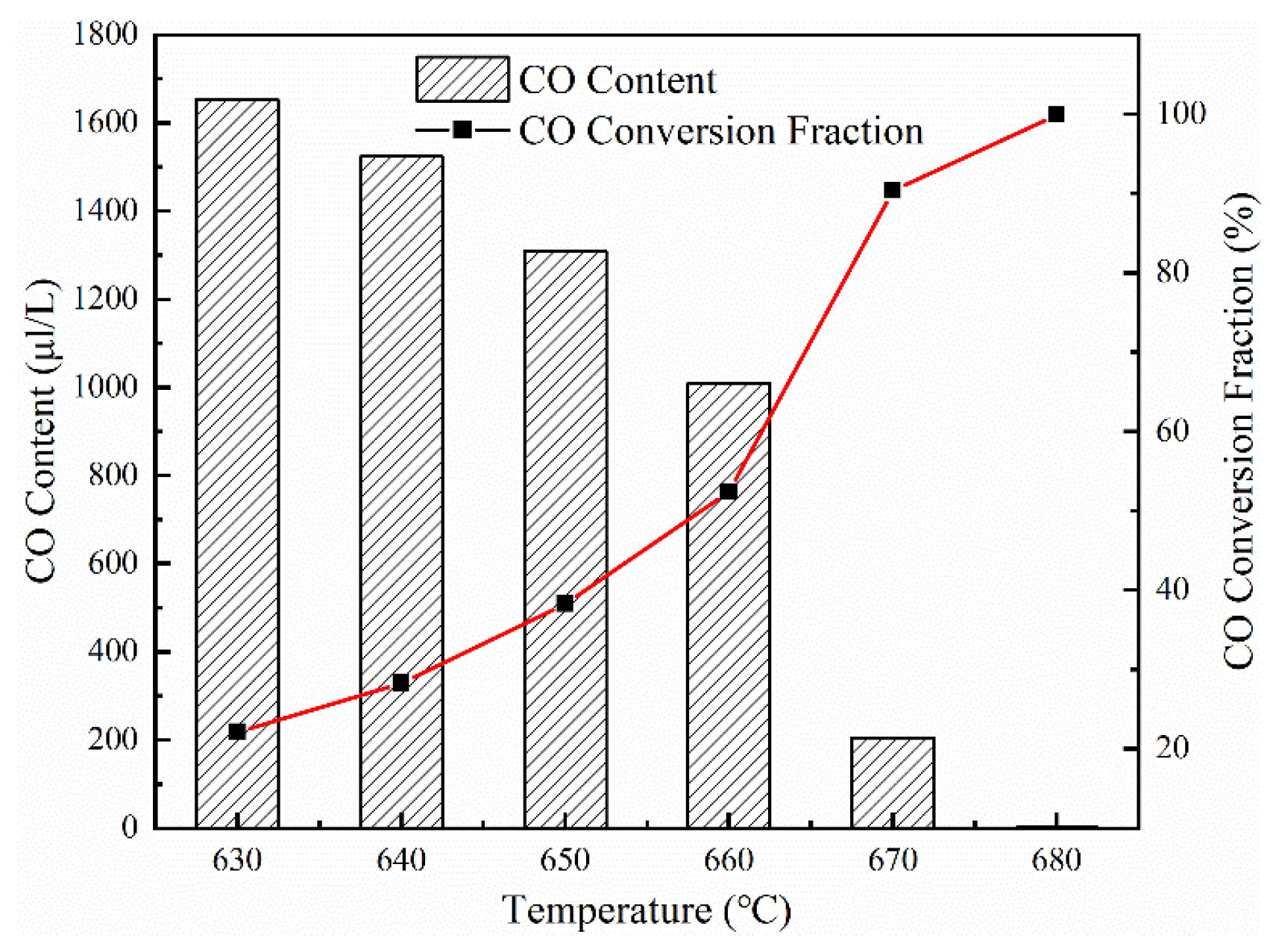

In systems devoid of H

2O, CO oxidation must proceed solely via direct reaction with O

2, so our experiment investigates the effect of temperature on the reactivity of O

2 oxidizing CO, and the experimental results are shown in

Figure 4. The O

2 proportion in feeding gas is 17.58%, and the CO content is 2816.8 μl/L. The CO oxidation experiments are carried out at, 650 °C, 662 °C, 668 °C, 675 °C, 700 °C, and 800 °C respectively. With the increase in the reaction temperature, the dissociation of O

2 is accelerated, providing more active oxygen atoms, so that more CO can be oxidized [

14]. Increasing the temperature of the tail flue gas can effectively reduce CO emissions. Therefore, installing a downstream combustion chamber can effectively increase the temperature of the tail flue gas, promote the CO oxidation reaction, and effectively reduce CO emissions.

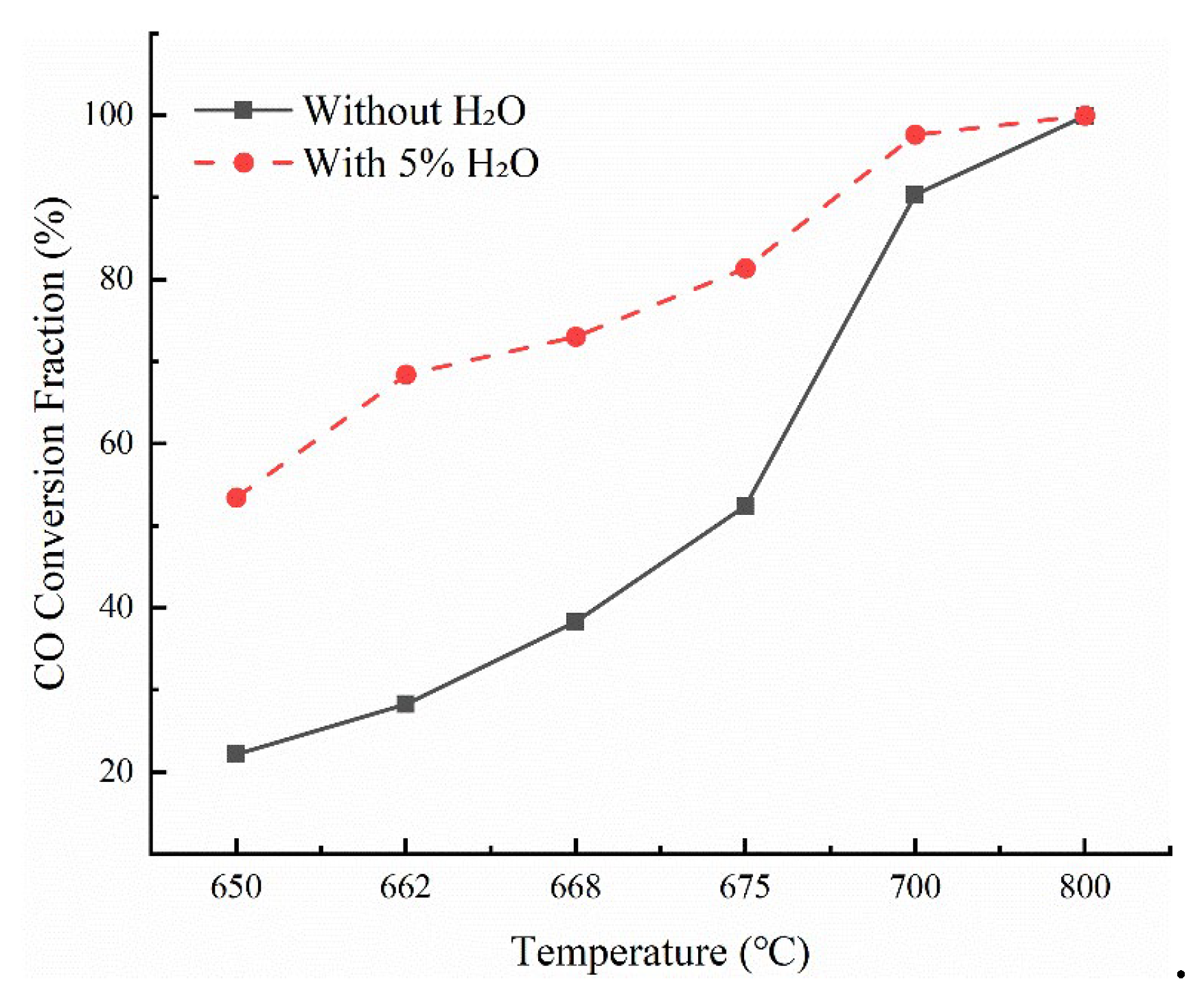

To further investigate the combined effects of temperature and H

2O on CO oxidation,

Figure 5 compares the experimentally determined CO conversion rates as a function of temperature, with and without the presence of H

2O. Based on the comparison of the effects of water vapor on the CO oxidation reaction in the experimental results, it can be concluded that the effect of water vapor on the oxidation of CO by O

2 gradually increases with the increase in temperature. When the reaction temperature is lower than 600 °C, there are fewer free radicals in the reaction, and water vapor has almost no catalytic effect on the CO oxidation reaction. When the reaction temperature is 650 °C, the CO content in the flue gas is 1653 μl/L without water vapor, and after introducing 5% water vapor, the CO content in the flue gas decreases to 989 μl/L. When the reaction temperature reaches 650 °C, the pyrolysis of water is more likely to occur, which significantly increases the concentration of OH. At the same time, with the increase in the reaction temperature, the reaction path of CO gradually changes from directly reacting with oxygen atoms to mainly reacting with OH to generate CO

2, and the reaction rate of this reaction path is faster. Therefore, after installing a downstream combustion chamber, introducing a part of water vapor in the reaction temperature range of 650 °C-700 °C can effectively promote the progress of the oxidation reaction and further reduce the CO emission in the flue gas.

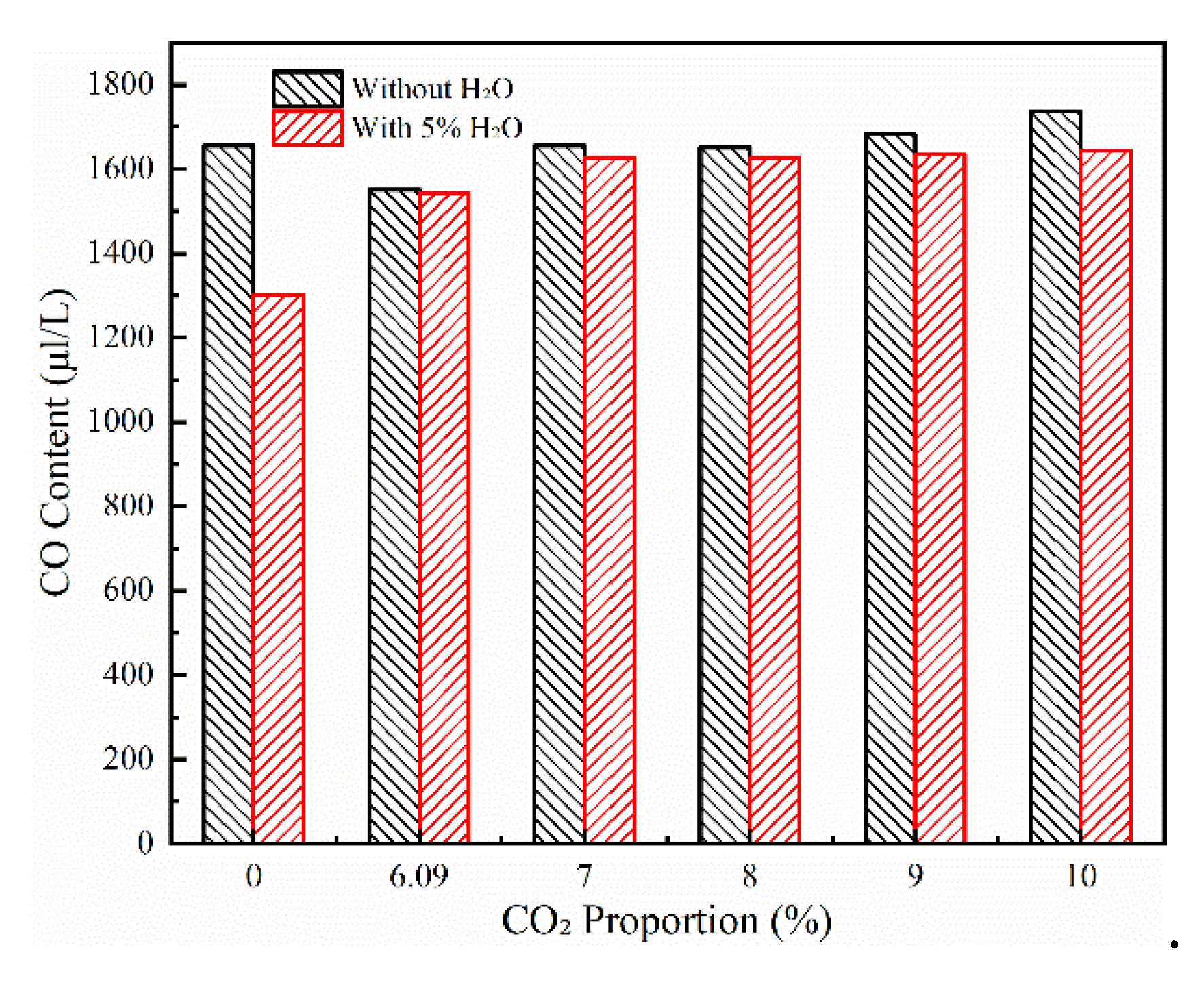

3.3. Effect of Co2 Content on Co Burnout

As a reaction product, CO

2 has a non-negligible impact on the CO oxidation reaction. The experiment studies the effect of CO

2 content on the CO oxidation reaction by maintaining the O

2 proportion at 17.58% and increasing the CO

2 content in the reaction gas to 6.09%, 7%, 8%, 9%, and 10% respectively at a reaction temperature of 650 °C. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 6. As a product of this oxidation reaction, an increase in CO

2 content will effectively inhibit the progress of the reaction. Therefore, the presence of CO

2 in the downstream flue gas of the anode furnace inhibits the CO oxidation reaction, resulting in the CO emission in the tail flue gas exceeding the standard. Since introducing a part of water vapor can promote the oxidation of CO, the effect of water vapor on the CO burnout rate under the condition of CO

2 in a complex flue gas atmosphere is explored. After adding CO

2, CO

2 consumes the free radical OH in the reaction process, which reduces the promoting effect of water vapor on the CO oxidation reaction. Therefore, under the conditions with and without water vapor, the difference in CO content in the flue gas decreases. However, the OH generated by the pyrolysis of water vapor still promotes the consumption of CO in the reaction, and the CO content in the flue gas is still higher than that without CO

2. From the above analysis, it can be concluded that under the condition of the CO ignition temperature, even if H

2O exists, the CO

2 in the tail flue gas will inhibit the CO oxidation reaction.

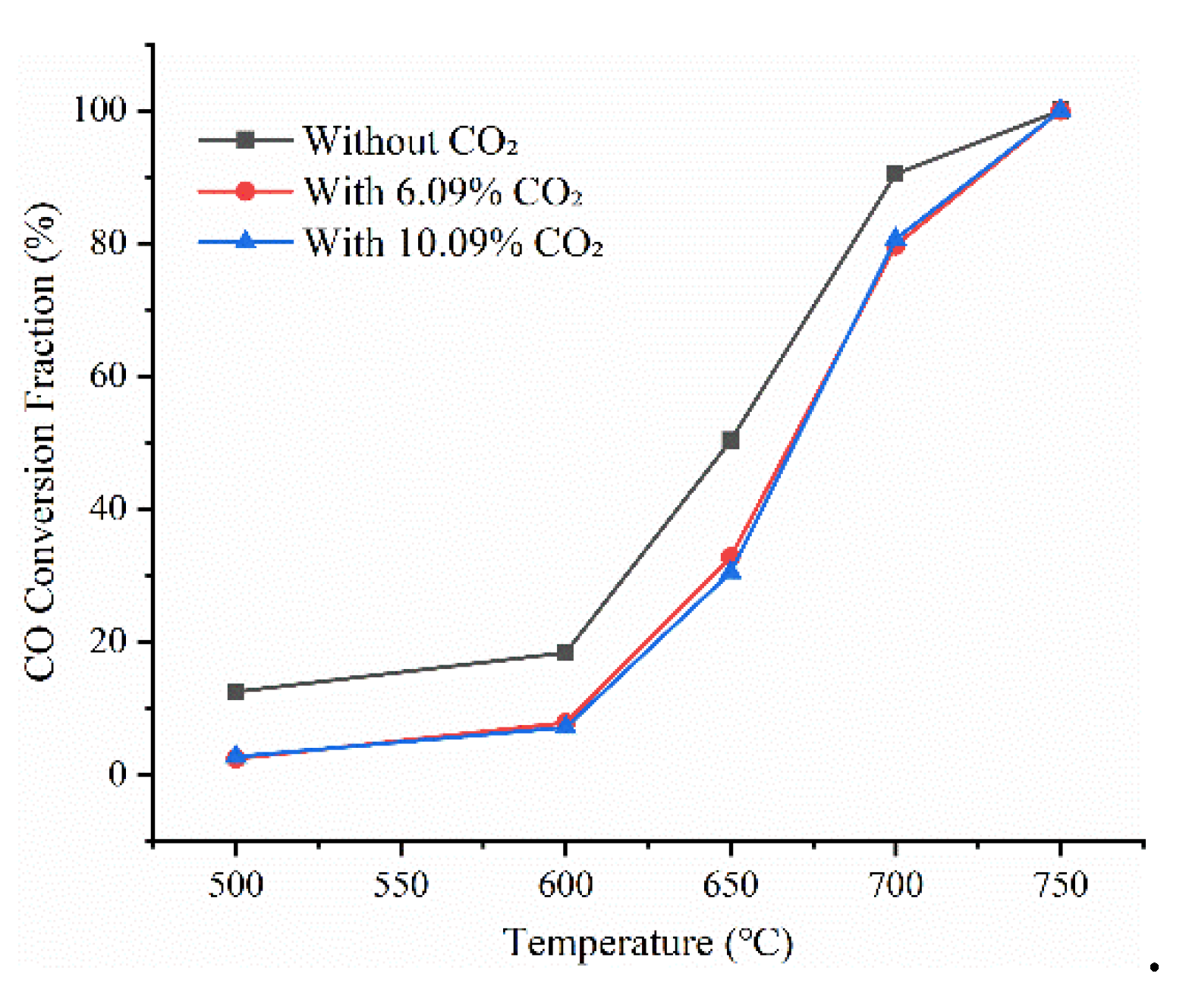

Since water vapor still has a promoting effect on the CO oxidation reaction under the condition of increased CO

2 content, the effect of CO

2 on the reaction under different reaction temperatures with water vapor is further explored. The CO

2 contents are set to 6.09%, 0%, and 10% respectively at reaction temperatures of 500 °C, 600 °C, 650 °C, 700 °C, and 750 °C to investigate the effects of reaction temperature and CO

2 proportion on the oxidation reaction. The experimental results are shown in

Figure 7. After increasing the CO

2 content in the reaction gas, the oxidation rate of CO decreases significantly. As a reaction product, the CO

2 in the tail flue gas inhibits the oxidation of CO under different temperature conditions in the combustion chamber. Obviously, CO

2 exhibited a consistently inhibitory effect within the 500–650 °C range. At 650 °C, the addition of 6.09% CO

2 suppressed the CO oxidation rate from 50.27% to 27.75%, underscoring its substantial impact on reaction kinetics. However, with the increase in the reaction temperature, the CO content gradually decreases. Therefore, in this reaction, the promoting effect of temperature on the reaction is greater than the inhibitory effect of CO

2 content. With the increase in the reaction temperature, CO is completely oxidized at 750 °C, and the CO

2 content has little effect on the final reaction temperature. For reducing CO emissions in the tail flue gas, ensuring a sufficient reaction temperature in the downstream combustion chamber can almost completely oxidize CO even if there is a certain amount of CO

2.

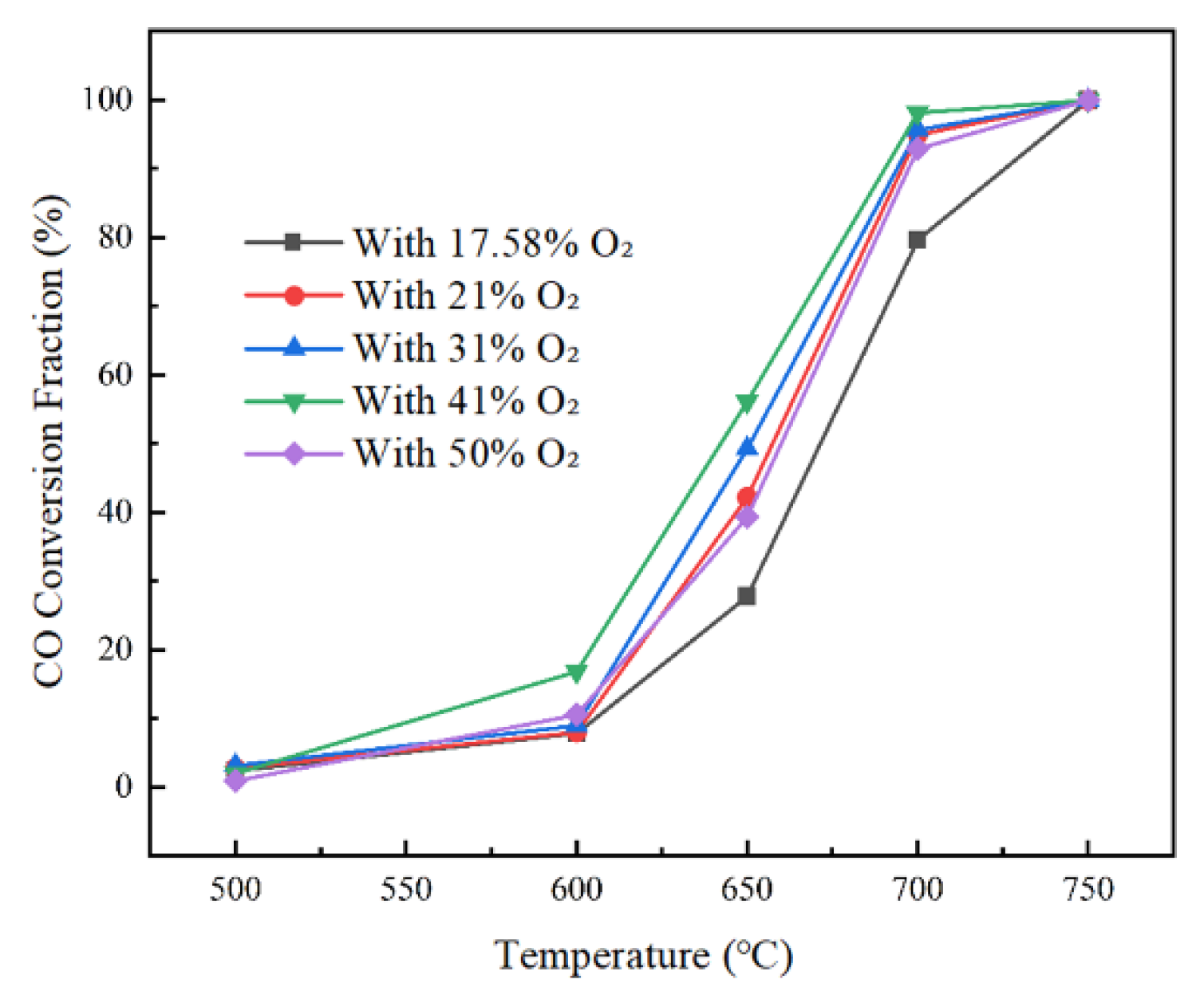

3.4. Effect of Increasing Oxygen Concentration on Co Burnout

Under the atmosphere conditions where the water vapor proportion in the downstream tail gas of the anode furnace is 5% and the CO

2 proportion is 6.09%, the experiment investigates the effect of O

2 proportion on the CO oxidation reaction. The O

2 contents are set to 17.89%, 21%, 31%, 41%, and 50% respectively, and the experimental results are shown in

Figure 8. As a reactant, after increasing the O

2 proportion, the O

2 equivalence ratio is less than 1, which is in an oxygen-enriched condition. This promotes the increase in OH free radicals and the progress of the reaction path between OH and CO, so the CO reduction rate in the flue gas increases to a certain extent. However, when the reaction temperature is below 600 °C, the reaction activity is low, so the promoting effect of increasing the oxygen content on the reaction is small. The results show that the oxygen content has little effect on the initial reaction temperature of the CO reduction reaction. When the reaction temperature in the combustion chamber is low, increasing the content of the reactant O

2 has a small promoting effect on the oxidation reaction. After increasing the O

2 content, the CO reduction rate can be increased only under the intermediate reaction temperature condition.

The experimental results show that increasing the oxygen content has a promoting effect on the reaction. However, increasing the oxygen content also promotes the generation of HO2 in the reaction. A large amount of low-activity HO2 will compete with OH for the reaction with CO, reducing the reaction rate. Therefore, when the oxygen content proportion increases to 51% during the reaction, its promoting effect on the reaction is less than that under the condition of 21% oxygen content, but greater than that under the original oxygen content condition of 17.58%. Moderate oxygen enrichment can increase the combustion rate, while excessive oxygen enrichment will lead to the inhibition of the reaction rate. Therefore, under the condition of ensuring a sufficient reaction temperature in the combustion chamber, appropriately increasing the reaction oxygen content can improve the burnout rate of CO in the tail flue gas.

To further explore the effect of O2 content on the CO burnout temperature, the reaction temperature range of 650 °C-700 °C is selected under different O2 content conditions. With the increase in temperature, the effect of oxygen content on the CO content in the flue gas gradually decreases. After 670 °C, the CO content in the flue gas is almost the same under different O2 content conditions. The influence range of increasing the O2 content on the CO reduction reaction is small. Only when the reaction temperature is around 650 °C, the CO reduction rate increases with the increase in O2 content, and when the O2 content reaches 51%, it also has a certain inhibitory effect on the reaction. The results show that increasing the O2 content has little effect on the final burnout temperature of the reaction.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, the calculation of the supplementary air volume for the tail flue gas from the 160 t capacity anode furnace was completed based on its CO concentration. Furthermore, the combustion characteristic of CO in the flue gas was experimentally examined with focus on the influence of high-concentration H2O and CO2, as well as the effect of increasing O2 concentration in the air. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) When CO accounts for 3-10% of total flue gas volume at full capacity of the anode furnace, the total flue gas volume ranges from 6800.3-7637.3 Nm3 during the reduction in the anode furnace, and the required air supply for CO burn off ranges from 545.1 m3 to 1617.9 m3.

(2) The addition of 5 vol% H2O within the critical temperature window of 650–700 °C significantly enhances CO oxidation. Introducing 2.5 vol% steam reduced the T50 of CO by 70 °C. This synergistic effect not only lowers CO emissions but also reduces the CO burnout temperature to approximately 700 °C, confirming steam as a key promoter under specific thermal conditions.

(3) CO2 exerts an inhibitory effect to CO burnout at 650 °C, where adding 6.09% CO2 suppressed the CO conversion rate from 50.27% to 27.75%. Nevertheless, the promoting effect of temperature overwhelmingly outweighs this inhibitory influence. Consequently, the presence of CO2 has a negligible impact on the final burnout temperature.

(4) Increasing the O2 content promotes CO combustion, but this effect is non-linear. An O2 concentration of 51% results in a lower promotion efficiency compared to the 21% condition, indicating that moderate oxygen enrichment enhances the burnout rate, whereas excessive enrichment inhibits the reaction rate. Notably, varying the O2 content has minimal influence on the final burnout temperature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Huixian Shi and Yuan Xu; Formal analysis, Enlin Chen and Jun Xi; Investigation, Enlin Chen, Jun Xi, Xing Ning and Changzhe Fan; Project administration Yuan Xu and Yuyun Zhang; Supervision, Yongbo Du and Huixian Shi; Writing – original draft, Yuan Xu, Changzhe Fan and Xing Ning; Writing – review & editing, Yongbo Du and Huixian Shi.

Funding

Basic Research Program of Yunnan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (202501CF070096)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Zhang for his conscientious help and works during the construction and debugging of the test bench.

Conflicts of Interest

None

References

- Tang C F, Zhang R L, Zhang W, et al. Recovery of copper from refining slags of copper fire anode furnace by waste acid leaching and CaO roasting process[J]. Separation Science and Technology, 2023, 58(3): 500-508. [CrossRef]

- Bielowicz, B. Waste as a source of critical raw materials—A new approach in the context of energy transition[J]. Energies, 2025, 18(8): 2101. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Liu G, Zhang L, et al. Formation mechanism of arsenic-containing dust in the flue gas cleaning process of flash copper pyrometallurgy: A quantitative identification of arsenic speciation[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2021, 423: 130193. [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Yang S, Wang H. Investigation of the oxygen-methane combustion and heating characteristics in industrial-scale copper anode refining furnace[J]. Energy, 2024, 298: 131278. [CrossRef]

- Shang Q, Feng D, Zhang X, et al. Synergistic effects of biomass/plastics and multi-step regulation of H2O in the co-production of H2-CNTs by gasification of biomass and plastic wastes. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy 379 (2025) 125695. [CrossRef]

- Xu B, Chen Y, Dong Z, et al. Eco-friendly and efficient extraction of valuable elements from copper anode mud using an integrated pyro-hydrometallurgical process[J]. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2021, 164: 105195. [CrossRef]

- Anderson A, Kumar V, Rao V M, et al. A review of computational capabilities and requirements in high-resolution simulation of nonferrous pyrometallurgical furnaces[J]. JOM, 2022, 74(4): 1543-1567. [CrossRef]

- Harvey J P, Courchesne W, Vo M D, et al. Greener reactants, renewable energies and environmental impact mitigation strategies in pyrometallurgical processes: A review[J]. MRS Energy & Sustainability, 2022, 9(2): 212-247. [CrossRef]

- Cao Q H, Lee S W. Effect of the Design Parameters of the Combustion Chamber on the Efficiency of a Thermal Oxidizer[J]. Energies, 2022, 16(1): 170.

- Abián M, Giménez-López J, Bilbao R, et al. Effect of different concentration levels of CO2 and H2O on the oxidation of CO: Experiments and modeling[J]. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 2011, 33(1): 317-323. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaos P, J HO, Matthias I. Investigation of CO recombination in the boundary layer of CH4/O2 rocket engines [J]. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 2020, 38(4): 6403-6411.

- Fauzy A, Chen G B, Lin T H. Applications of Hydrogenous Species for Initiation of Carbon Monoxide/Air Premixed Flame[J]. Energies, 2025, 18(12): 3003.

- Pawel N, Marian G. Impact of the application of fuel and water emulsion on CO and NOx emission and fuel consumption in a miniature gas turbine [J]. Energies, 2021, 14(8): 2224.

- Glarborg P, Kubel D, Kristensen PG, Hansen J, Dam-Johansen K. Interactions of CO, NOx and H2O under post-flame conditions [J]. Combustion Science and Technology 1995;110-111(1):461-85.

- Sui R, Mantzaras J, Law CK, Bombach R, Khatoonabadi M. Homogeneous ignition of H2/CO/O2/N2 mixtures over palladium at pressures up to 8 bar [J]. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2021;38(4):6583-91. [CrossRef]

- Wang EY, Tang SQ, Kang SH, et al. Study on combustion and CO emission control of ultra-low calorific gas[J]. Journal of Thermal Science and Technology, 2020, 19(04): 374-380. (In Chinese).

- Abián M, Millera Á, Bilbao R, Alzueta MU. Effect of CO2 atmosphere and presence of NOx (NO and NO2) on the moist oxidation of CO. Fuel 2019;236:615-21. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Mathieu O, Petersen EL, Bourque G, Curran HJ. Assessing the predictions of a NOx kinetic mechanism on recent hydrogen and syngas experimental data. Combustion and Flame 2017;182:122-41. [CrossRef]

- Alireza A, Alireza F, Hamed S. Multi-objective optimization of CO boiler combustion chamber in the RFCC unit using NSGA II algorithm [J]. Energy, 2021, 221: 119859.

- Kulczycki A, Przysowa R, Białecki T, et al. Empirical modeling of synthetic fuel combustion in a small turbofan[J]. Energies, 2024, 17(11): 2622. [CrossRef]

- Giuseppe I, Eduardo LP, Riccardo C, et al. Numerical investigation of high pressure CO-diluted combustion using a flamelet-based approach [J]. Combustion Science and Technology, 2020, 192: 1811243.

- Abián M,Giménez-López J,Bilbao R, et al. Effect of different concentration levels of CO2 and H2O on the oxidation of CO: Experiments and modeling[J].Proceedings of the Combustion Institute,2011,33(1):317-323. [CrossRef]

- Abián M,Millera Á,Bilbao R, et al. Effect of CO2 atmosphere and presence of NOx (NO and NO2 ) on the moist oxidation of CO[J].Fuel,2019,236615-621. [CrossRef]

- Yongbo D,Meng X,Jingkun Z, et al.Combustion characteristic of low calorific gas under pilot ignition condition—Exploring the influence of pilot flame products[J].Fuel,2023,333(P2).

- Niszczota P, Gieras M. Impact of the application of fuel and water emulsion on CO and NOx emission and fuel consumption in a miniature gas turbine. Energies 2021;14(8):2224. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).