1. Introduction

The scientific literature pertaining to low back pain is large and heterogeneous. It contains many studies relating to intervertebral motion, yet these sometimes seem to lack coherence. Researchers who study intervertebral motion have increasingly noticed discrepancies in the design and reporting of studies resulting from an inadequate definition of the phenomenon. This may ignore the temporal component [

1], and/or ignore the path that the motion has taken [

2] and/or use only the global start and stop positions to calculate the range of motion [

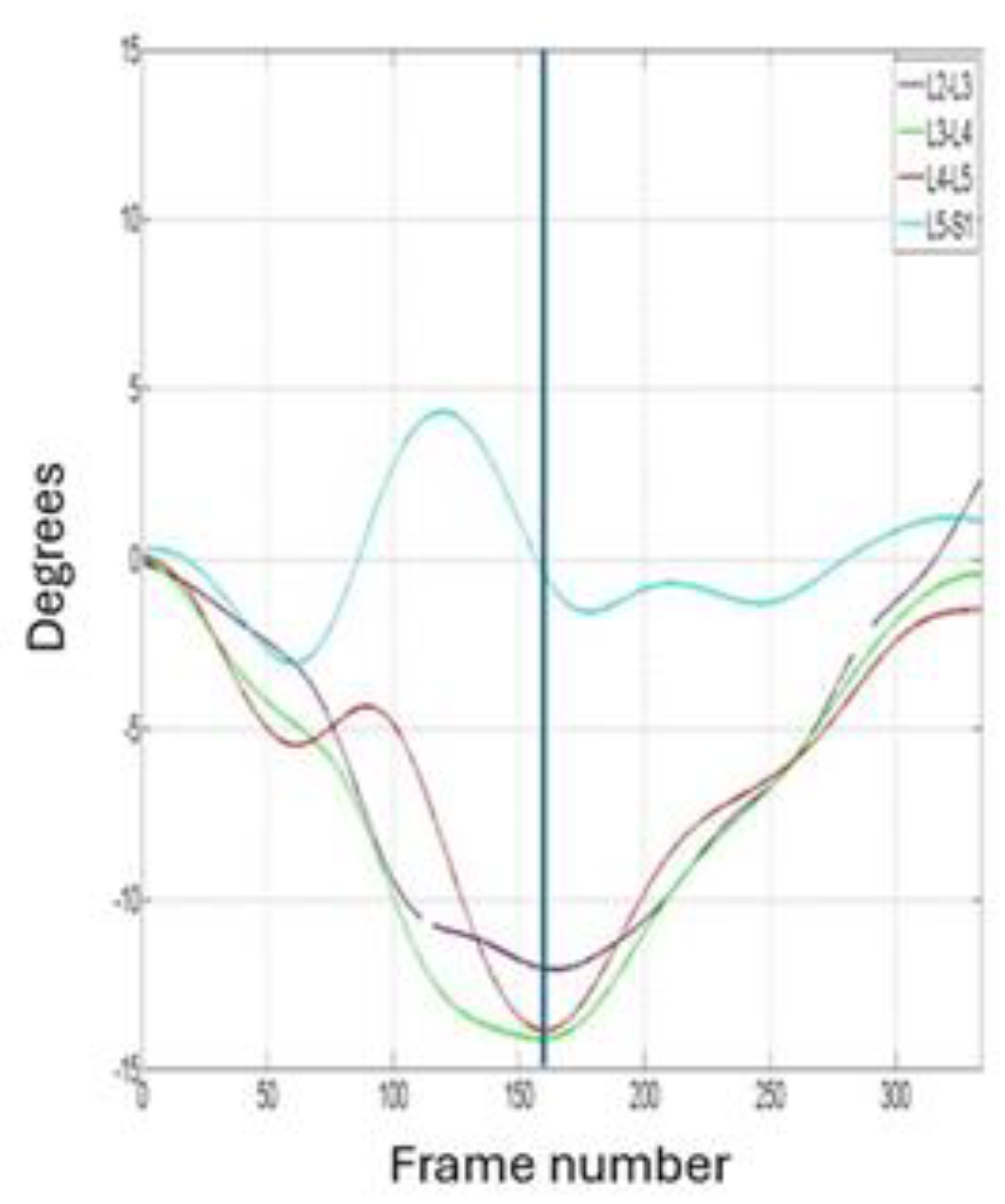

3]. As an illustration,

Figure 1 shows intervertebral rotation from a healthy asymptomatic research participant in which the L5 vertebra has returned to its starting position by the end of the participant’s maximum bending range, falsely indicating “no motion” at that level.

Methods for measuring and interpreting such motion have reached higher prominence in the research literature as technological sophistication has progressed, and some expect that we are on the verge of making important advances [

4,

5,

6]. However clinical studies still tend to confine intervertebral motion to overall rotation in upright postures, ignoring, for example, incremental rotation, translation, velocity and the sequencing of motion onsets. Passive restraint is seldom mentioned in studies of in vivo lumbar motion but is a necessary option in the investigation of the types of instability that could be obscured by loading and muscle activity.

Authors also sometimes imply that landmarks on the surface of the back over the lumbar spine represent the lumbar spine itself or compare (or combine) intervertebral motion findings with studies that have used different data collection protocols [

7,

8]. These discrepancies introduce uncontrolled variation (noise) that can obscure comparisons [

9]. Thus, a comprehensive and standardized taxonomy of study types for the measurement and interpretation of in vivo intervertebral motion in the lumbar spine is needed if we are to compare findings across studies, synthesize evidence and guide future research.

In particular, we wish to point out at the outset of this review that motion is the process of an object changing position over time, while displacement specifically refers to the change in position from an initial point to a final point, including direction. Thus, motion can be described using concepts like velocity and acceleration. By contrast, displacement is the change from an initial to a final position (spatial only) and the distance and direction between these positions. It follows that intervertebral range of motion is the maximum displacement between a pair of vertebral segments during a specific motion in a given plane and not, as the long-held definition states: “the difference between the two points of physiologic extent of motion” [

10]. Instead, we contend that it can occur anywhere in the motion and not necessarily at the end of the path of any given section of the spine that contains the vertebral pair. Thus, “motion” is defined as “change of location from a spatial position A to a different position B, whereby the moving figure was located at position A at time T1 and then located at position B at another time T2” [

11]. Talmy (1985) considers the path of motion to be the fundamental component of a motion event because without a path there is no motion. In the case of motion events, change of spatiotemporal location means a change in spatial and temporal configuration of the path that is the result of the motion [

12].

This scoping review aimed to address these issues by systematically identifying the study types employed in the literature to measure and interpret intervertebral motion. The intention was to map the prevailing concepts and create a taxonomy of studies that have involved the measurement and interpretation of in vivo lumbar spine intervertebral motion over the past 25 years. This information will hopefully serve as a resource for clinicians, researchers and policymakers to help facilitate a more coherent understanding of practice in the field and promote high standards in research design and reporting [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Arksey and O’Malley (2005) framework and following the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines [

14,

15]. A protocol was preregistered on the OSF database (

https://osf.io/dnwua/overview) and a literature search was conducted by one author using the electronic databases: PubMed, SCOPUS and CINAHL Ultimate, with Boolean operators combining MeSH terms and key words relating to: “lumbar spine”, “intervertebral motion”, “measurement”, “interpretation”, “human” and “in vivo”. Using the bibliographic search software:

https://rayyan.ai/, reports were identified and imported into a ReadCube reference management database (

https://papersapp.com) for screening.

Eligible studies were published between January 2000 and October 2025 and involved human participants of any age group where in vivo intervertebral motion of the lumbar spine (L1-S1) was measured and interpreted. Systematic reviews during this period were accessed and screened for additional eligible studies. Studies of interest generally encompassed kinematics (e.g. range of motion (RoM), instantaneous center of rotation (ICR), coupled motions), dynamics (e.g., motion patterns under load), and the methodologies used to acquire and analyze and/or interpret these data. The context was any clinical or research setting where in vivo lumbar intervertebral motion was studied. This included, but was not limited to studies of healthy individuals, patients with low back pain, post-surgical patients, athletes, and people in occupational settings. An example search string for PubMed might include:

“(lumbar spine[MeSH Terms] OR lumbar vertebra* OR lumbosacral OR low back) AND (intervertebral disc[MeSH Terms] OR intervertebral motion OR spinal motion OR kinematics OR dynamics OR range of motion OR coupled motion) AND (in vivo OR living OR human) AND (measurement OR imaging OR fluoroscopy OR MRI OR CT OR X-ray OR radiography OR optical tracking OR motion capture OR video analysis OR wearable sensor*)”

All empirical study designs were considered (e.g., observational studies, experimental studies, case series, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies). Narrative reviews, theoretical papers, animal studies, in vitro studies, cadaveric studies, and biomechanical models without in vivo validation were excluded. Studies were eligible if they satisfied all the following: Quantitative measurement, Continuous intervertebral motion (>3Hz), Lumbar spine, In vivo, Human and Article in English. Studies considered ineligible were; Reviews, Book chapters, Commentaries, Case studies, Qualitative studies, Discussions, Editorials, Letters, Guidelines, Protocols, and Conference papers.

After removal of duplicates, all studies were subjected to title and abstract screening for eligibility by the lead author and one other and a subset was identified for full-text screening. Cases of disagreement were arbitrated by a third author. This procedure was also followed for the charting process, in which information from studies eligible for full-text screening were initially extracted into a spreadsheet under the headings: lead author, year, short title, qualifying descriptions, include/exclude (with reasons) and access information (e.g. DOI). The results were considered by a different author and, in the event of disagreement, arbitrated by a further one before being allocated to its final charting position. Any additional articles chosen from private databases which did not appear in the search were considered in the same way at this stage.

Data items from studies that were accepted for inclusion were charted into tables according to their type and under the descriptive headings: Author/year, Country of lead author, Purpose of study, Technology, Participants/gender, Measurement, Interpretation, Radiation dose (if applicable) and Significance of findings (

see Supplementary Material). Studies were not assessed for methodological quality beyond requiring correct nomenclature. However, studies were only charted if they represented peer-reviewed and published research that met the criteria for eligibility and inclusion as independently verified by three authors. The charting process strove to present information from the studies rather than evaluate it. All authors approved the results of the charting process.

3. Results

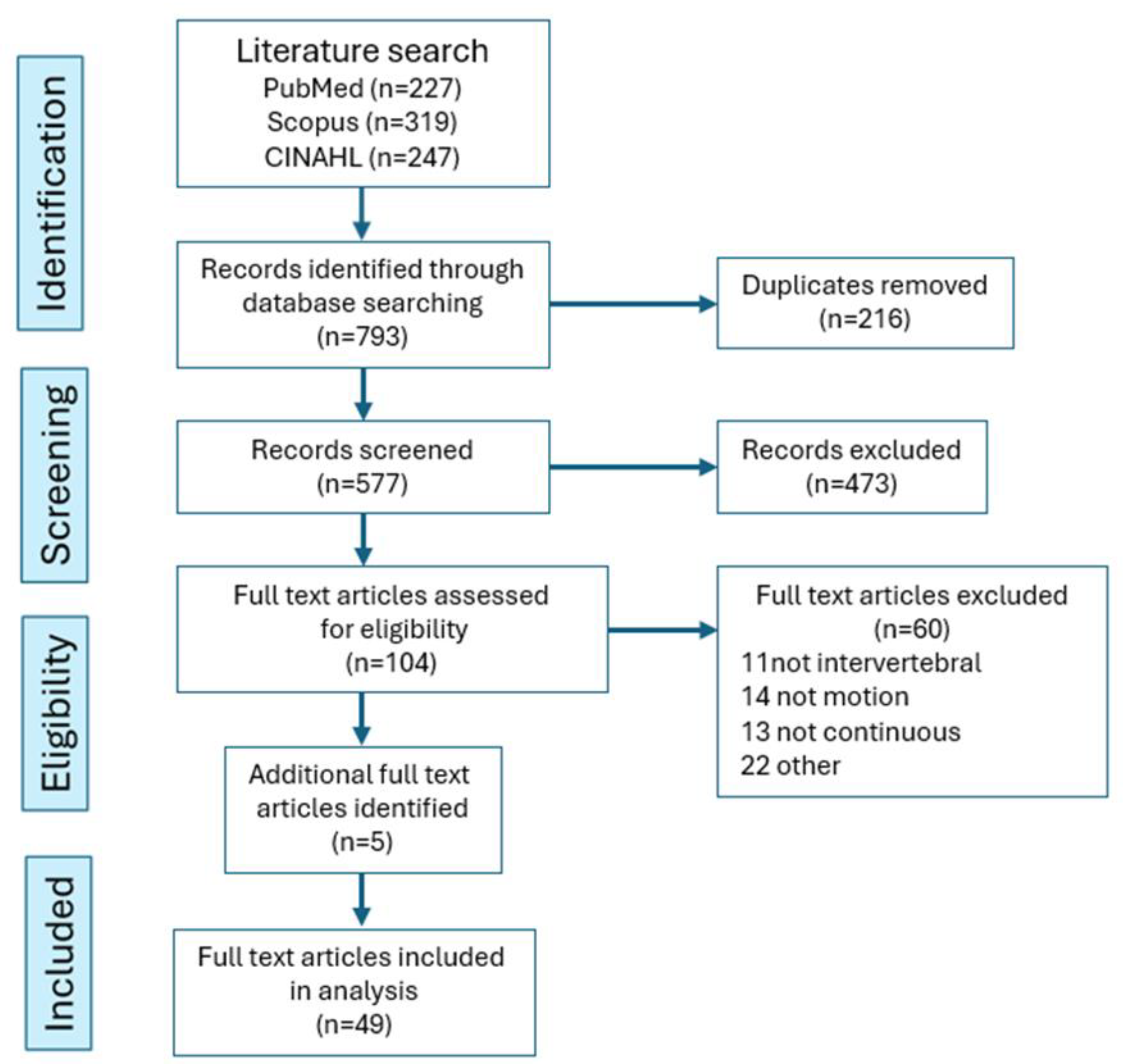

Database searching identified 793 studies, of which 216 were duplicates and were removed, leaving 577 for consideration (

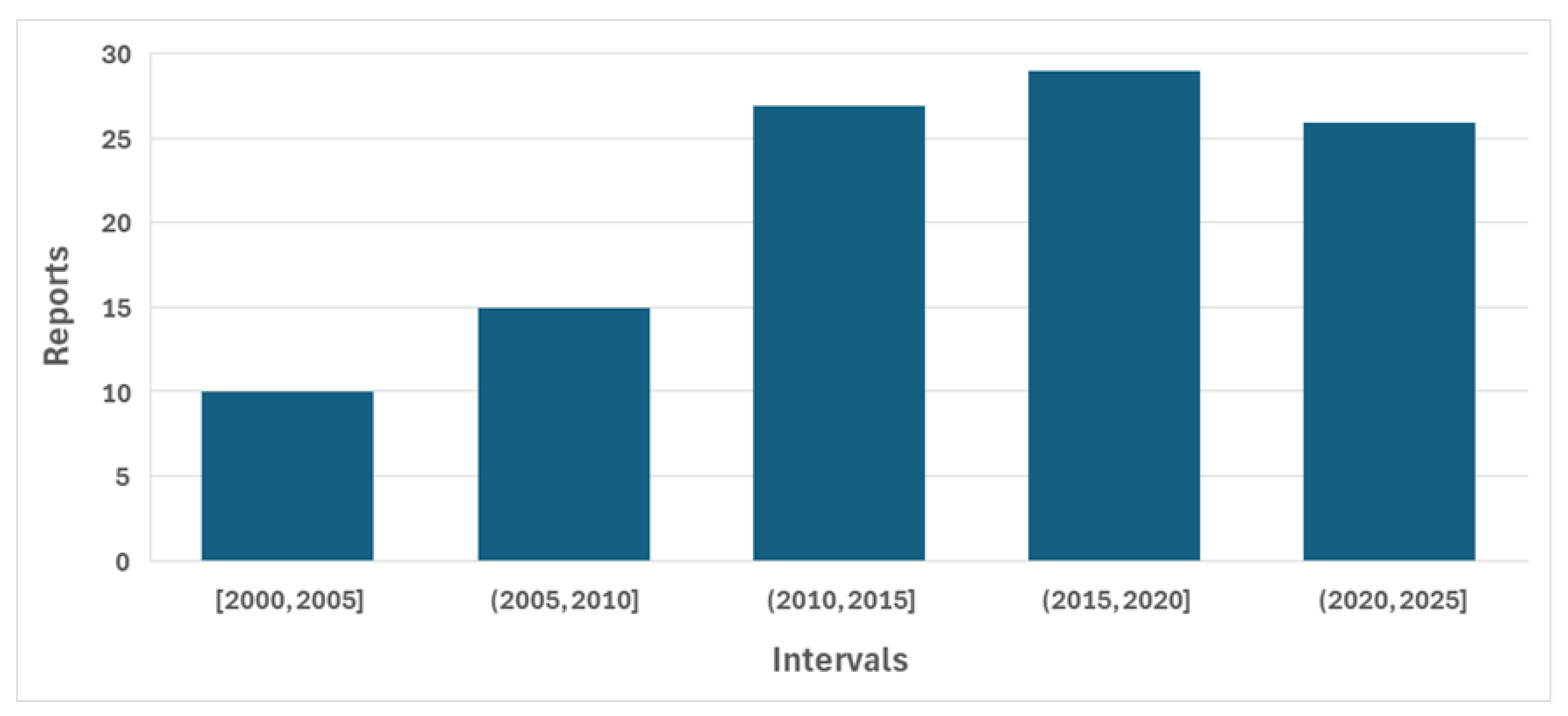

Figure 2). After title and abstract screening, 473 of these were excluded leaving 104 for full-text screening. Of these, 60 were excluded, mainly because they did not study intervertebral motion (11), did not study motion (14) or did not study continuous motion (13). After the addition of 5 studies from other sources known to the authors, and following full-text screening, 49 studies were found to be eligible for review. The 5-year distribution of publication dates of the 104 that underwent full-text screening shows an approximate doubling of articles that were published 5-yearly after the first decade of the study period (

Figure 3).

The 49 studies that met the criteria for eligibility and inclusion are represented as 11 types and shown in

Table 1. These had a total of 2151 participants with lead authors from 11 countries: USA (17), UK (15), Japan (3), China (3), Canada (3), Switzerland (2), Italy (2), Australia (1), Finland (1), Germany (1) and Iran (1).

3.1. Intervertebral Motion Interactions

Among the first phenomena to be studied in relation to the interactions between the intervertebral motion segments were the relative onsets of angular intervertebral motion during bending [

16,

17]. Like many of the studies in this review, motion X-rays were used to register the kinematics, which initially presented some technological barriers to measurement that had to be overcome to progress the work. It was found that after the initial Japanese studies, some 20 years had elapsed before automated vertebral image tracking and digital imaging improved the analysis process sufficiently to encourage phase lag studies to recommence. When it did, the value of measuring motion contributions for making comparisons between individuals or groups rather than raw values that were prone to wide variation became apparent [

18]. Then, to further explore apparent kinematic biomarkers for chronic, nonspecific back pain, principal component analysis was used [

19]. This was followed by the classification of the motion path types originally discovered by Harada et al [

17], using cineradiography, but now incorporating the first derivatives (velocity) of sagittal plane intervertebral rotation [

20]. This demonstrated through cluster analysis, that the top-down cascade pattern of lumbar flexion referred to by Harada in 2000 [

17] appeared to be the most common pattern of “phase lag”. However, clinical studies are needed to understand the relevance of this in symptomatic states.

3.2. Disc Degeneration Kinematics

The chronology of the use of intervertebral motion in the study of disc degeneration began with Takayagani et al in 2001 [

21], comparing flexion and return for rotation and translation in 41 patients with L4 degenerative spondylolisthesis and 20 controls. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to report on spondylolisthesis kinematics. It found that rotation and translation were simultaneous in controls, but not in patients where the more severe cases exhibited decreased translation. Following this 7 years later, Hasegawa et al [

22] used an intraoperative spinous distraction apparatus to measure restraint in terms of absorption energy and the neutral zone (NZ), taking disc height loss into account. The authors found that “Stiffness demonstrated a significant negative and NZ a significant positive relationship with disc height”. However, there were no significant differences between spines with “collapsed” discs than those without, although the NZ value was higher in those without the collapsed types and more sensitive to this measure in degenerative segments with preserved disc height. The authors went on to suggest that “degenerative segments with preserved disc height have a latent instability compared to segments with collapsed discs”. These two studies illustrate an interesting comparison of the kinematic versus the loading effects of disc degeneration.

Following the appearance of quantitative fluoroscopic systems, Breen et al [

23,

24] compared the kinematics of non-spondylolisthesis patients who had early-to-moderate disc degeneration to pain free controls in both standing and lying flexion-extension. The authors’ intention was to test the hypothesis of Farfan and Kirkaldy-Willis that early disc degeneration is associated with instability [

25]. This found that patients with disc degeneration exhibited more disrupted interactions between segments in terms of motion sharing, but only in passive recumbent motion. There was also only a weak-to-moderate negative correlation between disc height loss and weight bearing RoM and no correlation with translation or laxity. Meanwhile, Dombrowski et al [

2], using standing 3-D fluoroscopy and CT-generated bone models to study continuous dynamic sagittal rotation in degenerative spondylolisthesis, compared their findings with those from static flexion-extension radiographs. Their study found that 42% of the spondylolisthesis group demonstrated aberrant mid-range motion on intervertebral dynamic motion analysis and greater flexion translation on dynamic than static imaging. Caution is advised, however, in the interpretation of these latest studies, none of which assessed more than 10 patient-control pairs each.

3.3. Implanted Markers and Internal Sensors

Implanted marker systems in the spine are generally considered too invasive for other than serious spinal disorders, however they are still in use, although more usually for the measurement of displacement using static radiographs than for the measurement of actual intervertebral motion in disc replacement surgery [

26]. However, to capture motion and avoid radiation, implanted wires and screws have also been used to mount sensors percutaneously for tracking by motion capture systems.

Five studies were found in this category, two of chronic back pain patients [

27,

28] and three of healthy controls [

29,

30,

31]. All used optical sensors attached percutaneously to pedicle screws or K-wires implanted into the spines of chronic back pain patients and no further ones seem to have been published since 2013. The patient studies used 3D and 2D analysis respectively and did not involve control groups. Their authors suggest that they could be useful in testing internal fixation systems where the spine was being surgically exposed.

One system [

29] used ultrasound tracking of LEDs from L12-L2 and found within-subject variation of 0-6-42% during flexion-extension, lateral bending and axial rotation respectively. The last two studied normal ranges of the same motions from L1-S1 (the first study to compare the whole lumbar spine in vivo using bone pins) [

30] and reported that the main intervertebral motion during gait is mid-lumbar and coronal [

31].

3.4. Assessment of Lumbar Orthoses

Two early US studies were found [

32,

33] that used 2-D quantitative fluoroscopy in small groups of controls (4 and 10 respectively). Both used free (uncontrolled) bending during flexion/extension. The first tested a custom-fitted thoracolumbosacral orthosis and found that it reduced flexion range by 2/3, while the second compared no orthotic, a soft orthotic, a semirigid orthotic and a semirigid thoracolumbosacral orthotic and found that all three devices limited L3-4 and L4-5 flexion, but not L5-S1.

3.5. Technology Development

The 10 studies identified mainly challenged the technical viability of the technologies in this review for reliability, accuracy and radiation dosage during controlled versus uncontrolled weight bearing and recumbent flexion, extension and lateral bending. These mainly employed 2-D quantitative fluoroscopy [

7,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41] with one study of the reliability of an implanted Kirshner wire system for measurement of 3-D L1-S1 motion during gait [

42]. This study reported similar findings to Mac Williams et al [

31] (see above). Studies were mainly by US and UK groups, also with representation from Italy and Canada.

5.6. Back Pain Biomarkers

In their review of biomarker types in relation to chronic pain, Reckziegel et al [

43] concluded that the field has been advancing in terms of the investigation of hypotheses pertaining to underlying mechanisms. For chronic, nonspecific low back pain, the tendency has often been to frame these hypotheses around disordered intervertebral motion. The chief suspects have been excessive angular and/or linear RoM, laxity (as reflected by a steep starting motion gradient or attainment rate), or an increased attainment rate around the mid-range of the intervertebral motion path - suggestive of instability.

In our review we found no clear evidence for excessive RoM, whether using static or dynamic radiographs [

44]. However, attainment rate during standing flexion was assessed by Teyhen et al [

45] using 2-D quantitative fluoroscopy, who found it to be increased, although still with no evidence of increased RoM. A subsequent subgroup study comparing chronic nonspecific back pain patients and controls in flexion and return [

46] found a significantly smaller rotational motion contribution during the return phase from standing flexion at L5-S1 in patients.

Similar 2-D fluoroscopy studies using passive recumbent flexion did not detect this [

23,

47,

48] but instead found greater inequality of motion sharing (MSI) in patients with chronic nonspecific back pain. A further passive recumbent flexion and return study probed this further by measuring the timing of peak velocity during intervertebral flexion. This was found to occur earlier in the motion path at L5-S1 in back pain patients than in controls [

49]. Taken together, these studies may indicate MSI as a biomarker, linking disruption of passive restraint and chronic back pain.

Meanwhile, a recent 3D quantitative fluoroscopy study with CT models that assessed standing flexion-extension and lateral bending in patients with chronic back pain measured intervertebral rotations, translations and coupling and found heterogeneity in these variables [

50]. This study did not have a control group and further research is required. Another recent biplanar fluoroscopy study using 3D CT models examined the movement of endplate centers with respect to the sacrum before and after lifting in patients with recurrent back pain and healthy controls [

51]. This study found significant inter-test differences, with and without fatigue, in translation and z-axis rotation in both groups. This occurred slightly later in flexion-extension motion after fatigue. The authors suggest that this may indicate a protective mechanism or a role in dysfunction.

3.7. Post Stabilization Dynamics

Only two studies were found that addressed this. The first presented preliminary data and used biplanar fluoroscopy to track implanted metal markers in 5 patients 2, 3 and 6 months post-fusion, comparing intervertebral displacement at the beginning and end of trunk motion with minimum/maximum intervertebral displacement over the motion path, however, these did not correspond [

3].

The other study [

52] used 2-D fluoroscopy in 24 patients with flexible total disc replacements (TDRs) 6 weeks and 5 years post-surgery. The upper and lower TDR endplates were tracked and the continuous RoM with 10 repeated cycles measured in the coronal and sagittal planes during treadmill walking, indicating partial preservation of motion.

3.8. Normative Lumbar Kinematics

Five studies were eligible for the reporting of in vivo normative intervertebral motion. All were from the authors’ own labs and all used the same 2-D fluoroscopy technology protocols [

53]. A normative database is presented, consisting of 127 anonymized pain-free controls imaged during controlled weight bearing with recumbent left, right, flexion and extension lumbar motion from vertebral midplane angles throughout the motion sequences as captured at 15fps. These data are publicly available from the Open Science Framework database (

https://osf.io/a27py/) [

46]. They can be used to display and manipulate the motion sequence data with the appropriate transformations for comparison with users’ own studies if desired. For weight bearing flexion and return, transformation of intervertebral angles to proportional contributions has revealed the level-by level normative motion contribution patterns as a phenotype for comparison with clinical and experimental studies [

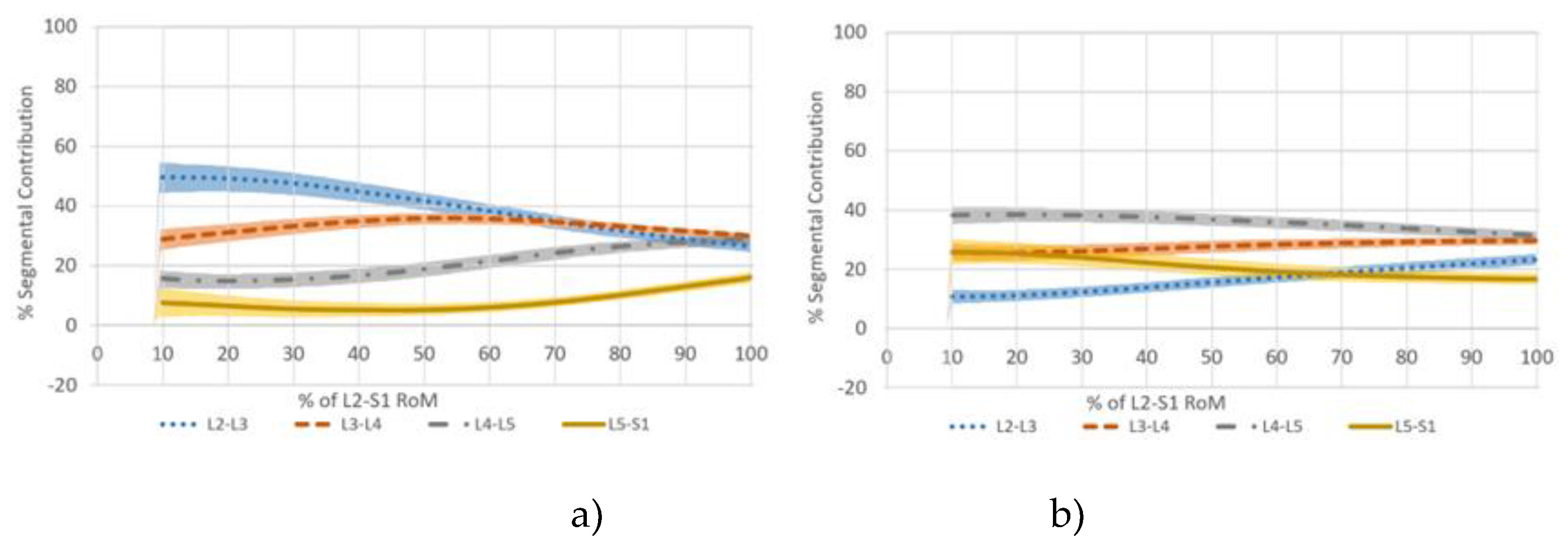

46,

54]

Figure 4.

The other studies present the lumbar L2-S1 IV-RoM, translation, laxity, MSI, MSV, regularity and symmetry from individual studies of healthy control populations in different configurations. All studies present their effective radiation dosage. Two studies present the minimal detectable change and intrasubject repeatability in healthy controls of some of the studies over a 6-week period [

55,

56]. These show evidence that measurements of translation and MSV are not suitable for longitudinal studies and that surface EMG measurements of longissimus thoracis, lumborum and multifidus amplitudes correlate with maximum RoM at L4-5 and L5-S1 during controlled standing flexion and return motion but are essentially silent during passive recumbent flexion and return.

3.9. Intervertebral Force-Deformation

Four studies were found. All were of healthy controls and involved bending and lifting functional loads. All used 3-D fluoroscopy linked to CT-generated bone models, one measuring sagittal intervertebral rotation and translation [

57] and another average ICR locations and migration ranges [

58]. These two found linear relationships between load, rotation, translation and level-specific changes in ICR location and dispersion with increased loading. In the future this information could contribute to the establishment of biomechanical models and normative values with which to compare conditions and interventions [

59].

One of the other studies investigated changes in disc height and shear strain patterns and distributions during lifting [

60], finding that these restraint patterns can be mapped and could contribute to models. The last study tested facet joint kinematics during lifting and found greater translation at L3 and L4 than at other levels in response to loads, which may help to explain the pathogenesis of structural changes associated with load bearing [

61].

3.10. Aerospace Lumbar Kinematics

Two studies addressed the problem of post-spaceflight disc herniation in relation to lumbar spine kinematics using 2-D quantitative fluoroscopy and MRI. The first examined relationships between prolonged exposure to microgravity and weight bearing flexion kinematics in 12 ISS crew members; 6 of whom developed disc hernia symptoms post-flight [

62]. This study found with MRI that post-spaceflight disc herniation was associated with compromised multifidus quality and, using 2-D fluoroscopy, that symptomatic returning astronauts had reduced flexion-extension RoM at their L3-4 and L4-5 levels.

The second study tested a microgravity countermeasure skinsuit that compressed the spine overnight to limit the intervertebral stiffness that follows a period of absence of axial loading and preserves motion in the spine. Twenty healthy controls were tested with and without skinsuit use, finding significantly more lumbar intervertebral flexion and translation range after the skinsuit was used [

63]. These studies may have implications for longer space missions, including interplanetary travel.

3.11. Soft Tissue Artifact (STA) Measurement

Three recent studies attempting to measure soft tissue artifacts were eligible for this review. The first [

64] compared optical motion capture in 6 controls for flexion and extension with one landmark’s motion measured with 3-D quantitative fluoroscopy driven by CT models. With this protocol, STAs for flexion ranged from 4.0mm for L1-3 to 13.5mm for L4-5 and for extension 2.7mm for L4-5 and 6.1mm for L1-3. Errors varied with anatomical direction, marker location, vertebral level and bending phase.

The second study [

8] aimed to evaluate static placement errors as well as STA from MoCap optical marker clusters during flexion-extension and lateral bending in 39 low back pain patients, taking patient characteristics into account. Data from surface markers positioned over L1 and L5 spinous processes were compared to continuous data from 3D fluoroscopy with CT modelling using a volumetric tracking process. Static placement errors were greatest in a superior-inferior direction (29.5mm) and the L1-L5 RMS STA error in the sagittal plane ranged from 1.7

o to 23.6

o. This was larger in flexion-extension than in side-bending. Errors were participant-dependent and unrelated to age and BMI.

The third study [

65] compared skin-based MoCap with accelerometers attached over L2, L4 and S1, and 2D quantitative fluoroscopy (QF) at L2-3, L3-4, L4-5 and L5-S1 for contemporaneous recording during flexion and extension in 20 controls. The 95% limits of agreement for L2-S1 between technologies for flexion were: QF vs MoCap -10.1

o to +10.1

o, QF vs accelerometer -9.8

o to +9.8

o and accelerometer vs MoCap -1.0

o to 1.1

o. For extension they were: QF vs MoCap -5.7

o -+5.5

o, QF vs accelerometer -6.3

o to +6.6

o and for accelerometer vs MoCap -0.9

o -+0.9

o. Differences from QF tended to be greater in the lower lumbar spine, and in flexion compared to extension. However, differences between participants were highly variable, confirming the results of the other studies.

Despite the difficulty of placing external markers on the skin over adjacent vertebrae, preventing adjacent intervertebral comparisons being made between technologies, it can probably be concluded that skin-based marker systems do not measure underlying intervertebral motion accurately. Conversion factors that would improve this do not currently seem to be within reach.

3:12. A Taxonomy of Study Types

The need for a taxonomy of study types suggested by these topics is firmly planted in the unknowns of spinal biomechanics and sustained by our erstwhile inability to measure intervertebral motion in vivo. A suggested taxonomy is presented in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

This review presents the results and trajectory of investigation choices by biomechanics researchers over the past quarter century by identifying the main study types that have addressed the measurement and interpretation of intervertebral motion. We have attempted to map the key concepts and create a taxonomy of vivo lumbar spine intervertebral motion measurement and interpretation from studies published over the past 25 years. The results indicate that research outputs in this field have increased and the Study types suggest the prevailing research priorities. For example, the need to better understand Normal lumbar kinematics is seen as paramount and should encourage the standardization of available technologies, which at present appear to favor imaging. However, although there are state-of-the-art techniques such as Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) for exploring between-level motion path relationships using vector field analysis [

66], motor control strategies are inherently interconnected over time. Therefore, a point-by-point evaluation may not be sufficient to fully capture the temporal dependencies underlying coordinated movement. Nevertheless, intervertebral force deformation is also accessible via the kinematic measurement of strains, as demonstrated by Byrne et al [

60].

The attention given to Disc degeneration kinematics is unsurprising given the ubiquitousness of this condition, while the appearance of microgravity’s effects on intervertebral kinematics in space has made an unexpected appearance as Aerospace lumbar kinematics. By contrast, interest in direct intervertebral kinematic measurements using Implanted markers and internal sensors placed in situ during surgery may be waning, as despite the opportunity for greater precision in motion measurement, they did not appear after 2013 in our review.

Given the progress made in disc replacement surgery, including around motion preservation systems, their rare appearance in in vivo kinematics research under Post stabilization dynamics is surprising and is perhaps attributable to the complexity, scarcity and cost of fluoroscopic systems for measurement [

6,

67]. These systems were dominant in the articles found in this review, where Technology development has been heavily focused on reducing inaccuracies, imprecision and to some extent, radiation dosage. Research into Soft tissue artifact measurement, however, has been slow to appear, but now seems largely complete, and some of the questions surrounding the Assessment of lumbar orthoses appear to have been addressed.

This leaves Nonspecific back pain biomarkers to complete the present taxonomy. Given the heterogeneity and complexity of this condition across biopsychosocial domains, mechanical biomarkers may best contribute to back pain assessment and treatment if considered alongside non-biomechanical mechanisms and interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy [

68,

69].

4.1. Limitations and Further Work

Some studies may have been missed or erroneously excluded by our literature search, especially in respect of the recording and analysis of continuous intervertebral motion data. Non-English language studies that might have contributed were nonetheless excluded. A major weakness for interpretation was the number of studies with small samples, and we recommend replication of those that presented promising results for the discovery of nonspecific back pain biomarkers. Recent scoping reviews relating to the kinematics of the cervical spine and other body joints have called for greater standardization and sophistication of data recording, image tracking, analysis and interpolation and we strongly support this call [

6,

67]. There is also a particular need to embed automated image registration as a way to reduce the laboriousness of analysis.

Radiation dosage is a cause for concern with some studies, and greater efforts to provide 3-D MRI models for biplanar fluoroscopy investigations has been recommended where 3-D analysis is judged necessary [

70]. We also recommend kinematic studies of the performance of total disc replacements and investigations of adjacent segment disorder, utilizing a more complete choice of kinematic measures, including the inclusion of sagittal alignment for structural derangements and extending image acquisition to include recumbent passive motion.

5. Conclusion

The research literature in respect of lumbar intervertebral motion is substantial, variable in subject matter and burdened by a legacy of semantic discrepancies. However, there have been important advances around clinically useful measurement and interpretation, as well as the prospect of others to come. The result of this review challenges the traditional standard of care based on static radiographs, but with no simple, inexpensive or readily available option to replace it. Hopefully, it will help to clarify available options and provide incentives to pursue the promising ones.

The original data presented in the study are freely available as Supplementary Material in [repository name, e.g., FigShare] at [DOI/URL] or [reference/accession number].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B., A.B., M.M.; J.B. and A.dR.; Investigation, A.B.; A.B.; Methodology, A.B., A.B. and J.B.; Literature search, A.B., A.B., J.B.; Data extraction, A.B., A.B., J.B; Software, A.B.; Adjudication, A.dR; J.B. M.M.; Data curation, A.B.; A.B.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; Writing—review and editing, A.B., A.B., M.M.; A.dR.; J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are openly available as

Supplementary Material in [repository name, e.g.,

FigShare] at [DOI/URL] or [reference/accession number]. Otherwise, the original contributions presented are included in the article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the author(s) used Gemini AI in formulating its context in the protocol. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RoM |

Range of motion |

| ICR |

Instantaneous center of rotation |

| MSI |

Motion sharing inequality |

| MSV |

Motion sharing variability |

| QF |

Quantitative fluoroscopy |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| STA |

Soft Tissue Artifact |

| NZ |

Neutral Zone |

| TDR |

Total disc replacement |

| SPM |

Statistical parametric mapping |

| LED |

Light-emitting diode |

| ISS |

International space station |

References

- Zwambag, D.P.; Beaudette, S.M.; Gregory, D.E.; Brown, S.H.M. Distinguishing between Typical and Atypical Motion Patterns amongst Healthy Individuals during a Constrained Spine Flexion Task. J. Biomech. 2019, 86, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dombrowski, M.E.; Rynearson, B.; LeVasseur, C.; Adgate, Z.; Donaldson, W.F.; Lee, J.Y.; A., A.; Anderst, W.J. ISSLS Prize in Bioengineering Science 2018: Dynamic Imaging of Degenerative Spondylolisthesis Reveals Mid-Range Dynamic Lumbar Instability Not Evident on Static Clinical Radiographs. European Spine Journal 2018, 27, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderst, W.J.; Vaidya, R.; Tashman, S. A Technique to Measure Three-Dimensional in Vivo Rotation of Fused and Adjacent Lumbar Vertebrae. Spine J. 2008, 8, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, J.D.; Wills, B.P.D.; McIntosh, T.C.; Balderston, R.A. Evaluation of Spinal Kinematics Following Lumbar Total Disc Replacement and Circumferential Fusion Using In Vivo Fluoroscopy. Spine 2007, 32, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, J.; Fornaciari, P.; Senteler, M.; Roth, T.; Snedeker, J.G.; Farshad, M. Kinematics of the Spine Under Healthy and Degenerative Conditions: A Systematic Review. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 47, 1491–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurangzeb, A.; Zailani, M.H.B.M.; Tan, Q.H.; Leong, D.; Kumar, D.S.; Janssen, M.E.; Chew, Z. From Static X-Rays to Dynamic 3D Tracking: A Scoping Review of Cervical Spine Imaging-Based Motion Assessment. Eur. Spine J. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Castellvi, R.J.; Davis, D.C.; Lee, M.P.; Lorio, R.E.; Prosko, D.; Wade, C. Variability in Flexion Extension Radiographs of the Lumbar Spine: A Comparison of Uncontrolled and Controlled Bending. International Journal of Spine Surgery 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; LeVasseur, C.; Gale, T.; Megherhi, S.; Shoemaker, J.; Pellegrini, C.; Gray, E.C.; Smith, P.; Anderst, W.J. Lumbar Spine Marker Placement Errors and Soft Tissue Artifact during Dynamic Flexion/Extension and Lateral Bending in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Biomech. 2024, 176, 112356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakoutian, M.; Volkheimer, D.; Street, J.; Dvorak, M.F.; Wilke, H.-J.; Oxland, T.R. Do in Vivo Kinematic Studies Provide Insight into Adjacent Segment Degeneration? A Qualitative Systematic Literature Review. European Spine Journal 2015, 24, 1865–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjabi, M.M.; White, A.A. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; JB Lippincott, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Talmy, L. Lexicalization Patterns. In Language Typology and Synchronic Description; Schopen, T., Ed.; Cambridge University Press, 1984; Vol. 3, pp. 47–159. [Google Scholar]

- Filipović, L.; Ibarretxe-Antuñano, I. Semantic Typology. In Cognitive Linguistics; Key, Topics, Dąbrowska, E., Divjak, D., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin/Boston, 2007; ISBN 978-3-11-062299-7. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int. J. Évid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayama, M.; Abumi, K.; Kaneda, K.; Tadano, S.; Ukai, T. Phase Lag of the Intersegmental Motion in Flexion-Extension of the Lumbar and Lumbosacral Spine. An in Vivo Study. Spine 1996, 21, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, M.; Abumi, K.; Ito, M.; Kaneda, K. Cineradiographic Motion Analysis of Normal Lumbar Spine During Forward and Backward Flexion. Spine 2000, 25, 1932–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, A.; Breen, A. Dynamic Interactions between Lumbar Intervertebral Motion Segments during Forward Bending and Return. J. Biomech. 2020, 102, 109603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownhill, K.; Mellor, F.; Breen, A.; Breen, A. Passive Intervertebral Motion Characteristics in Chronic Mid to Low Back Pain: A Multivariate Analysis. Méd. Eng. Phys. 2020, 84, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematimoez, M.; Breen, A.; Breen, A. Spatio-Temporal Clustering of Lumbar Intervertebral Flexion Interactions in 127 Asymptomatic Individuals. J. Biomech. 2023, 154, 111634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayanagi, T.T.; Takahashi, K.; Yamagata, M.; Moriya, H.; Kitahara, H. Using Cineradiography for Continuous Dynamic-Motion Analysis of the Lumbar Spine. [Miscellaneous Article]; Spine 2001, September 1, 26(17):1858-1865.

- Hasegawa, K.; Kitahara, K.; Hara, T.; Takano, K.; Shimoda, H.; Homma, T. Evaluation of Lumbar Segmental Instability in Degenerative Diseases by Using a New Intraoperative Measurement System. J. Neurosurg.: Spine 2008, 8, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.; Breen, A. Uneven Intervertebral Motion Sharing Is Related to Disc Degeneration and Is Greater in Patients with Chronic, Non-Specific Low Back Pain: An in Vivo, Cross-Sectional Cohort Comparison of Intervertebral Dynamics Using Quantitative Fluoroscopy. Eur Spine J 2018, 27, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.; Mellor, F.; Morris, A.; Breen, A. An in Vivo Study Exploring Correlations between Early-to-Moderate Disc Degeneration and Flexion Mobility in the Lumbar Spine. Eur. Spine J. 2020, 29, 2619–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfan, H.F.; Kirkaldy-Willis, W.H. Instability of the Lumbar Spine. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 1982, 165, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordway, N.R.; Fayyazi, A.H.; Abjornson, C.; Calabrese, J.; Park, S.-A.; Fredrickson, B.; Yonemura, K.; Yuan, H.A. Twelve-Month Follow-up of Lumbar Spine Range of Motion Following Intervertebral Disc Replacement Using Radiostereometric Analysis. SAS J. 2008, 2, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, J.P.; Pierrynowski, M.R.; Bednar, D.A.; Yang, S.X. Relationship between Pain and Vertebral Motion in Chronic Low-Back Pain Subjects. Clin. Biomech. 2002, 17, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, T.; Nydegger, T.; Oxland, T.; Schlenzka, D. Three-Dimensional Motion Patterns During Active Bending in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine 2002, 27, 1865–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gercek, E.; Hartmann, F.; Kuhn, S.; Degreif, J.; Rommens, P.M.; Rudig, L. Dynamic Angular Three-Dimensional Measurement of Multisegmental Thoracolumbar Motion In Vivo. Spine 2008, 33, 2326–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozumalski, A.; Schwartz, M.H.; Wervey, R.; Swanson, A.; Dykes, D.C.; Novacheck, T. The in Vivo Three-Dimensional Motion of the Human Lumbar Spine during Gait. Gait Posture 2008, 28, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWilliams, B.A.; Rozumalski, A.; Swanson, A.N.; Wervey, R.A.; Dykes, D.C.; Novacheck, T.F.; Schwartz, M.H. Assessment of Three-Dimensional Lumbar Spine Vertebral Motion During Gait with Use of Indwelling Bone Pins. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2013, 95, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooi, D.V.; Abad, G.; Basford, J.R.; Maus, T.P.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Kaufman, K.R. Lumbar Spine Stabilization With a Thoracolumbosacral Orthosis. Spine 2004, 29, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basford, U.; Anderson, M.L.; Cunniff, J.G.; Kaufman, K.R.; Jelsing, E.J.; Patrick, T.A.; Magnuson, D.J.; Maus, T.P.; Yaszemski, M.J.; Basford, J. Video Fluoroscopic Analysis of the Effects of Three Commonly-Prescribed off-the-Shelf Orthoses on Vertebral Motion. Spine 2010, 15, E525–E529. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, T.M.; Zitnay, J.L.; Barocas, V.H.; Nuckley, D.J. Quantification of Continuous in Vivo Flexion–Extension Kinematics and Intervertebral Strains. Eur. Spine J. 2014, 23, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.C.; Muggleton, J.M.; Mellor, F.E. An Objective Spinal Motion Imaging Assessment (OSMIA): Reliability, Accuracy and Exposure Data. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2006, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, P.; Cesarelli, M.; Cerciello, T.; Romano, M.A. Continuous Description of Intervertebral Motion by Means of Spline Interpolation of Kinematic Data Extracted by Videofluoroscopy. J. Biomech. 2012, 45, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.J.; Lee, D.C.; Wade, C.; Cheng, B. Measurement Performance of a Computer Assisted Vertebral Motion Analysis System. Int. J. Spine Surg. 2015, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.; Breen, A. Accuracy and Repeatability of Quantitative Fluoroscopy for the Measurement of Sagittal Plane Translation and Finite Centre of Rotation in the Lumbar Spine. Méd. Eng. Phys. 2016, 38, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreozzi, E.; Pirozzi, M.A.; Fratini, A.; Cesarelli, G.; Bifulco, P. Quantitative Performance Comparison of Derivative Operators for Intervertebral Kinematics Analysis. 2020 IEEE Int. Symp. Méd. Meas. Appl. (MeMeA) 2020, 00, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, D.; Breen, A.; Breen, A.; Mior, S.; Howarth, S. Investigator Analytic Repeatability of Two New Intervertebral Motion Biomarkers for Chronic, Nonspecific Low Back Pain in a Cohort of Healthy Controls. Chiropractic and Manual Therapies 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teyhen, D.S.; Flynn, T.W.; Bovik, A.C.; Abraham, L.D. A New Technique for Digital Fluoroscopic Video Assessment of Sagittal Plane Lumbar Spine Motion. Spine 2005, 30, E406–E413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S. In Vivo Lumbar Spine Biomechanics: Vertebral Kinematics, Intervertebral Disc Deformation, and Disc Loads, 2012 Thesis: Department of Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Reckziegel, D.; Vachon-Presseau. E.; Petre, B.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Baliki, M.N.; Apkarian, A.V. Deconstructing Biomarkers for Chronic Pain- Context- and Hypothesis-Dependent Biomarker Types in Relation to Chronic Pain. Pain 2019, 160, S37–S48. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.S.; Carr, C.B.; Wong, C.; Sharma, A.; Mahfouz, M.R.; Komistek, R.D. Altered Spinal Motion in Low Back Pain Associated with Lumbar Strain and Spondylosis. Évid.-Based Spine-Care J. 2013, 04, 006–012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyhen, D.S.; Flynn, T.W.; Childs, J.D.; Kuklo, T.R.; Rosner, M.K.; Polly, D.W.; Abraham, L.D. Fluoroscopic Video to Identify Aberrant Lumbar Motion. Spine 2007, 32, E220–E229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, A.; Carvalho, D.D.; Funabashi, M.; Kawchuk, G.; Pagé, I.; Wong, A.Y.L.; Breen, A. A Reference Database of Standardised Continuous Lumbar Intervertebral Motion Analysis for Conducting Patient-Specific Comparisons. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 745837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.; Mellor, F.; Breen, A. Aberrant Intervertebral Motion in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Retrospective Cohort Study and Control Comparison. European Spine Journal 2018, 27, 2831–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, F.E. An Evaluation of Passive Recumbent Quantitative Fluoroscopy to Measure Mid-Lumbar Intervertebral Motion in Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain and Healthy Volunteers, 2014 Thesis. Bournemouth University.

- Breen, A.; Nematimoez, M.; Branney, J.; Breen, A. Passive Intervertebral Restraint Is Different in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Retrospective Cohort Study and Control Comparison. Eur. Spine J. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderst, W.; Kim, C.J.; Bell, K.M.; Gale, T.; Gray, C.; Greco, C.M.; LeVasseur, C.; McKernan, G.; Megherhi, S.; Patterson, C.G.; et al. Intervertebral Lumbar Spine Kinematics in Chronic Low Back Pain Patients Measured Using Biplane Radiography. JOR Spine 2025, 8, e70069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Zhang, L.; Yu, H.; Qin, Y.; Jia, L.; Tsai, T.-Y.; Yu, Y.; Cheng, L. Different Spatial Characteristic Changes in Lumbopelvic Kinematics Before and After Fatigue: Comparison Between People with and Without Low Back Pain. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, R.S.; Lichtwark, G.A.; Armstrong, C.; Barber, L.; Scott-Young, M.; Hall, R.M. Fluoroscopic Assessment of Lumbar Total Disc Replacement Kinematics During Walking. Spine 2015, 40, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.C.; Teyhen, D.S.; Mellor, F.E.; Breen, A.C.; Wong, K.W.N.; Deitz, A. Measurement of Intervertebral Motion Using Quantitative Fluoroscopy: Report of an International Forum and Proposal for Use in the Assessment of Degenerative Disc Disease in the Lumbar Spine. Adv. Orthop. 2012, 2012, 802350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, A.; Breen, A. Reference Database of Continuous Vertebral Flexion and Return. Open Science Framework 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.; Claerbout, E.; Hemming, R.; Ayer, R.; Breen, A. Comparison of Intra Subject Repeatability of Quantitative Fluoroscopy and Static Radiography in the Measurement of Lumbar Intervertebral Flexion Translation. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 19253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, A.; Hemming, R.; Mellor, F.; Breen, A. Intrasubject Repeatability of in Vivo Intervertebral Motion Parameters Using Quantitative Fluoroscopy. Eur Spine J 2019, 28, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyangar, A.K.; Zheng, L.; Tashman, S.; Anderst, W.J.; Zhang, X. Capturing Three-Dimensional In Vivo Lumbar Intervertebral Joint Kinematics Using Dynamic Stereo-X-Ray Imaging. J. Biomech. Eng. 2014, 136, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyangar, A.; Zheng, L.; Anderst, W.; Zhang, X. Instantaneous Centers of Rotation for Lumbar Segmental Extension in Vivo. J. Biomech. 2017, 52, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxland, T.R. Fundamental Biomechanics of the Spine - What We Have Learned in the Past 25 Years and Future Directions. Journal of Biomechanics 2016, 49, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.M.; Aiyangar, A.K.; Zhang, X. A Dynamic Radiographic Imaging Study of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Morphometry and Deformation In Vivo. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wen, W.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Han, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, J.; Miao, J. Kinematic Characteristics and Biomechanical Changes of Lower Lumbar Facet Joints Under Different Loads. Orthop. Surg. 2021, 13, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.F.; Nyayapati, P.; Johnson, G.T.A.; Dziesinski, L.; Scheffler, A.W.; Crawford, R.; Scheuring, R.; O’Neill, C.W.; Chang, D.; Hargens, A.R.; Lotz, J.C. Biomechanical Changes in the Lumbar Spine Following Spaceflight and Factors Associated with Post spaceflight disc herniation. The Spine Journal 2022, 2, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, A.; Carvil, P.; Green, D.; Russomano, T.; Breen, A. Effects of a Microgravity SkinSuit on Lumbar Geometry and Kinematics. European Spine Journal 2023, 32, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, X.; Ling, Z.; Wang, C.; Gu, C.; Zhan, X.; Yu, H.; Lu, S.; Tsai, T.-Y.; Yu, Y.; Cheng, L. Lumbar Segment-Dependent Soft Tissue Artifacts of Skin Markers during in Vivo Weight-Bearing Forward–Backward Bending. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 960063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, M.; Breen, A.; Rix, J.; Carvalho, D.D. Concurrent Validity of Skin-Based Motion Capture Systems in Measuring Dynamic Lumbar Intervertebral Angles. J. Biomech. 2025, 180, 112503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T.C.; Robinson, M.A.; Vanrenterghem, J. Vector Field Statistical Analysis of Kinematic and Force Trajectories. J. Biomech. 2013, 46, 2394–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setliff, J.C.; Anderst, W.J. A Scoping Review of Human Skeletal Kinematics Research Using Biplane Radiography. J. Orthop. Res. 2024, 42, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewicki, J.; Breen, A.; Popovich, J.; Reeves, P.; Sahrmann, S.A.; Dillen, L. van; Vleeming, A.; Hodges, P.W. Can Biomechanics Research Lead to More Effective Treatment of Low Back Pain? A Point-Counterpoint Debate. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewicki, J.; Hodges, P.W.; Popovich, J.M.; Aminpour, P.; Gray, S.A.; Lee, A.S.; Breen, A.; Brumagne, S.; Dieën, J.H. van; Dillen, L.R.V.; et al. A Meta-Model of Low Back Pain to Examine Collective Expert Knowledge of the Effects of Treatments and Their Mechanisms. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morbée, L.; Chen, M.; Herregods, N.; Pullens, P.; Jans, L.B.O. MRI-Based Synthetic CT of the Lumbar Spine: Geometric Measurements for Surgery Planning in Comparison with CT. Eur. J. Radiol. 2021, 144, 109999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).