1. Introduction

Carbon-fiber honeycomb sandwich composites combine lightweight design with high load-bearing capacity, vibration damping, and superior energy absorption, making them indispensable in modern aerospace structures. They are often used in aerospace applications, such as aircraft fuselage and wing structures. Under the influence of impact, such structures are prone to damage, such as core collapse and surface tearing, affecting structural performance and reliability. Low-energy impacts often cause internal damage that cannot be visually detected, posing significant challenges for structural health monitoring of these composites [

1,

2,

3]. Damage resulting from low-energy impacts is not discernible through visualization methods, because damage manifestations such as matrix cracks and delamination primarily occur within the laminate. Most composites are brittle and absorb energy primarily through elastic deformation and damage mechanisms rather than plastic deformation. In a composite system, most impacts on the composite plate occur in the normal direction, and its resistance to impact damage is minimal because of the absence of a thickness-reinforced phase. Impact loads induce interlayer shear and tensile stresses that can lead to interlayer cracking. To address this challenge, a sensor network must be installed within the structure to measure the response signal upon impact. Through signal analysis, health monitoring technologies that can effectively localize impact damage and improve real-time damage detection in advanced composite structures can be developed.

Effective signal processing is fundamental to accurate impact localization, as it governs how structural-response data are translated into reliable damage-detection results. Researchers have investigated various localization algorithms, including Lamb waves [

4], frequency-response functions [

5], triangulation techniques [

6], and artificial-intelligence algorithms [

7]. Impact-response signal processing can be categorized based on the diverse research objects and methodologies employed, as follows:

The first category is based on time-difference localization techniques. The time-difference localization technique determines impact location based on the relationships among distance, angle, and wave propagation time. This is often accomplished using advanced signal-processing methods that extract the time-domain information of impact signals from various sensor locations. Ciampa and Meo [

8] studied field impact detection, which can identify the location of acoustic emissions detected by the monitoring system in real time, and proposed an algorithm based on the surface combined with piezoelectric sensors to measure the difference in the stress wave in time‒frequency analysis. Based on time–frequency analysis, the amplitude of the continuous wavelet transform was used to determine the arrival time of the wave packet, solving a set of nonlinear equations using a local Newton iterative method based on an unconstrained optimization technique to derive the shock position coordinates and wave velocity. Ren et al. [

9] extended the spatial filter algorithm for impact monitoring in composite structures by utilizing two-dimensional linear piezoelectric sensor arrays for signal acquisition. They proposed a spatial filtering-based structural impact monitoring system that does not require wave-velocity estimation. This study proposes a spatial filter-based method for localizing structural impacts without the wave velocity.

The second category includes frequency-domain-based localization methods. Hiche et al. [

10] proposed a novel localization method that involves measuring the maximum strain spectrum through fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensors. FBG sensors are utilized to collect the strain signals and identify the maximum strain value corresponding to the impact location. This method requires only a limited structural analysis and a small number of sensors, and its feasibility was substantiated through simulation and experimental verification. The approach was validated through simulation and experimental results.

The third category includes system modeling approaches. This approach entails a comparison between the measured and simulated signal features, where damage localization is determined by the minimum discrepancy between the measured and simulated structural signal features. Rezayat et al. [

11] obtained data from FBG sensors and developed a variable-selective least-squares algorithm that utilizes structural patterns and data. This algorithm was experimentally validated and demonstrated three times the accuracy of the classical pseudo-inverse algorithm. Hafizi, Epaarachchi, and Lau [

12] proposed a localization method for obtaining experimental data from FBG sensors using infrared sensing techniques. The group velocity was determined from the dispersion curves, and the difference between the crest times of the two sensors was defined as the time-delay difference. Then, localization was determined using a system of linear equations.

The fourth category includes machine learning-based and fitting techniques. This method requires establishing data input‒output relationships for complex structures to achieve impact localization. Jang and Kim [

13] proposed a low-energy impact localization method for a reinforced composite plate using reference data, trained the model using extensive reference data, and experimentally validated the proposed method. Shrestha et al. [

14] proposed a low-energy impact localization method for a reinforced composite plate using a one-dimensional array of FBG sensors and a reference database. The proposed method was validated on a Jabiru UL-D wing, and the maximum error was found to be less than 35 mm, confirming the feasibility of this method. In a subsequent study, Shrestha et al. [

15] proposed a method for localizing low-energy impacts based on anomalous error values. In this study, strain signals were acquired using FBG sensors, and validation was conducted on a carbon fiber-reinforced plastic (CFRP) prototype. The localization error was 10.7 mm. Sai et al. [

16] proposed an FBG impact localization system based on quasi-Newton and particle swarm optimization algorithms. The FBG sensing network consists of eight fiber gratings, which are used for impact signal detection, with the time difference extracted using the Shannon wavelet transform. The impact localization system relied on nonlinear equations derived from the time difference and coordinates of the FBGs. These algorithms were employed to solve a set of nonlinear equations, yielding the coordinates of the impact source.

A complex nonlinear relationship exists between the impact response signal and low-velocity impact location, making it challenging to develop a mathematical model using traditional methods. Machine learning is a data-driven approach that constructs statistical models using training data, thereby characterizing nonlinear, high-dimensional, and high-complexity relationships among the data. Consequently, it has been extensively employed to identify low-velocity impact areas and localize low-velocity impacts on plate structures. Datta et al. [

17] extracted impact features, including peaks, means, standard deviations, and energy indices, from impact response signals. These features were extracted using a least-squares support vector regression (SVR) model, which was used to identify the locations of low-velocity impacts on CFRP structures. To locate the low-energy effect on the laminate, Lu et al. [

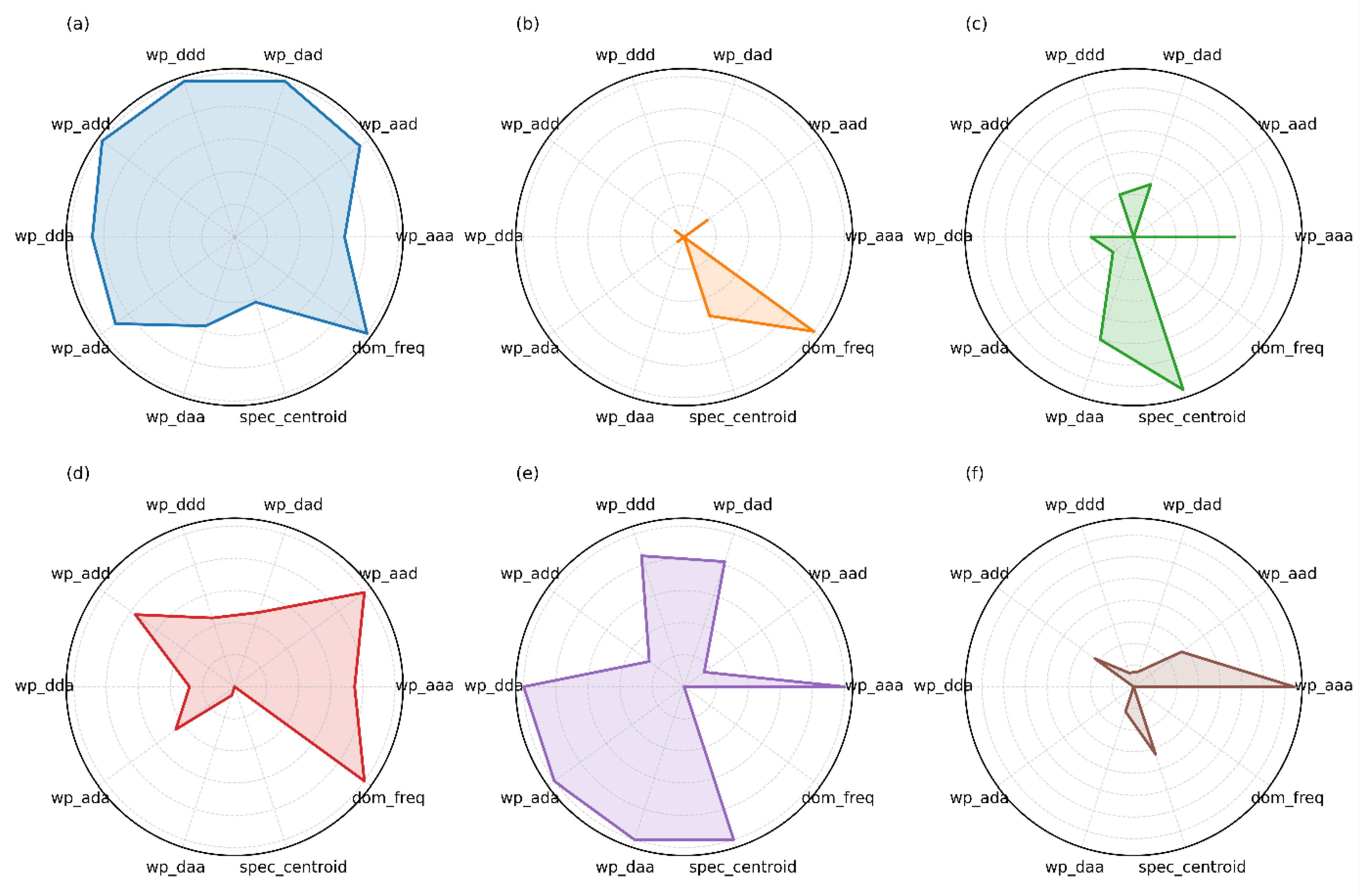

18] extracted the band energy corresponding to the sixth node as the impact feature and optimized the hyperparameters of the SVR model. This was achieved through wavelet packet decomposition of the impact response signal. Sai et al. [

19] developed an impact localization model based on an extreme learning machine utilizing the band energies corresponding to the first and second nodes. Furthermore, Lu et al. [

20] used the wavelet method to eliminate noise in an impact response signal, thereby enhancing the precision of extracting the time difference of arrival (TDOA). They then incorporated TDOA as an input feature into a least-squares support vector machine to detect the location of low-velocity impacts on CFRP laminates. Yu et al. [

21] extracted the short-time energy feature and combined it with an optimized support vector machine (SVM) model to achieve accurate low-velocity impact localization for CFRP laminates. Zheng [

22] introduced a method for impact localization on honeycomb sandwich panels using a projective dictionary pair-learning classifier, showcasing advancements in impact detection technology. A comprehensive review of the extant literature indicates increased research efforts on the impact resistance of honeycomb sandwich composites and the optimization of their design for low-energy impact scenarios. Further research is required to explore diverse materials and structural configurations to enhance the impact resistance of these panels.

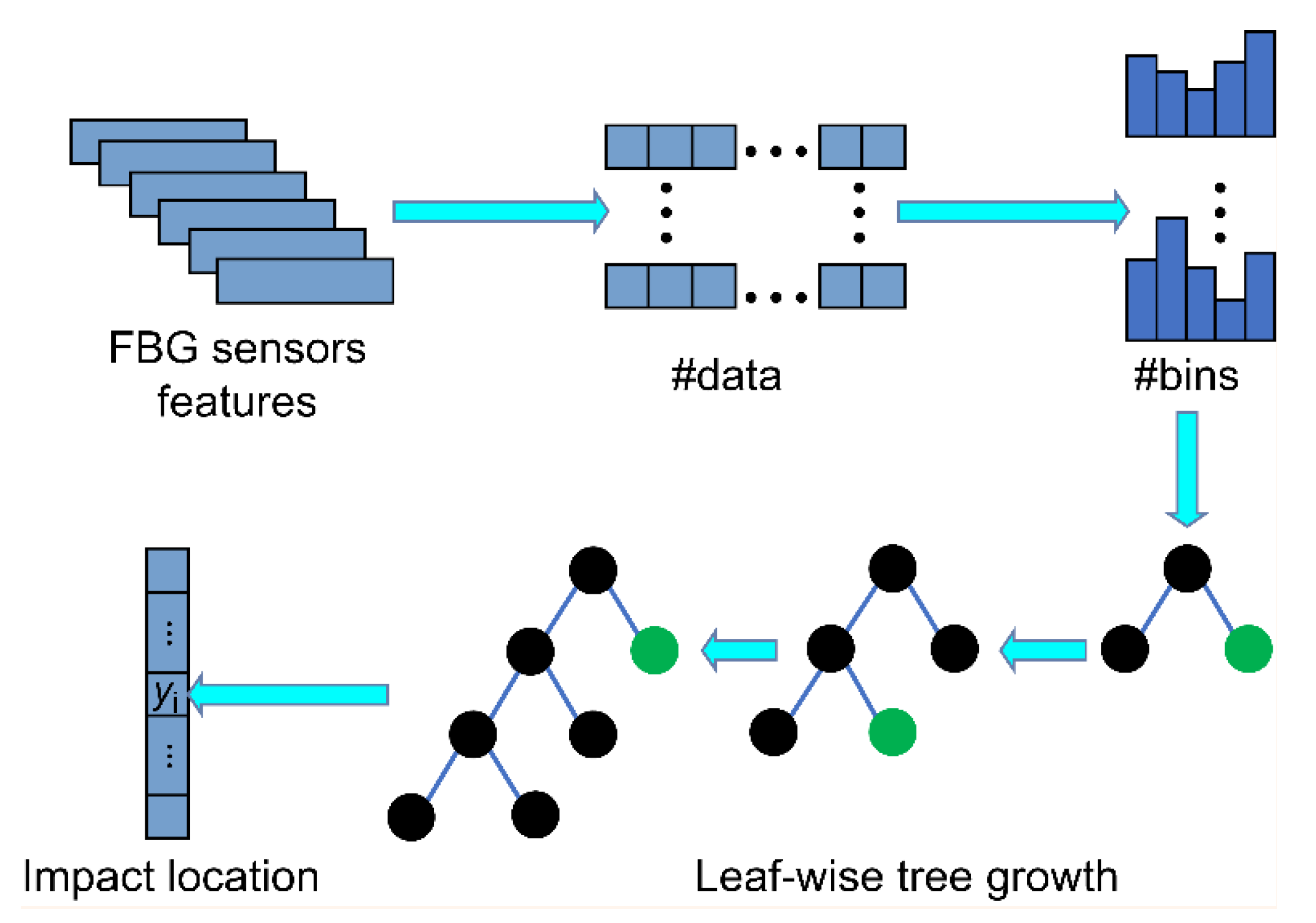

Although numerous machine-learning approaches have been developed for impact localization, most still suffer from limited accuracy, overfitting on small datasets, and inadequate feature representations for low-energy impacts in complex honeycomb structures. These drawbacks include the difficulty in obtaining stable input datasets, susceptibility to underfitting and overfitting, the need to collect a large number of training samples for the regression model, and the selection of appropriate hyperparameters to enhance its regression capability. Moreover, current impact localization methods based on machine learning primarily focus on extracting individual features, such as time-, frequency-, and time–frequency-domain features, as inputs to the regression model. This approach disregards the significance of multi-domain features in enhancing the efficacy of impact localization methods. To overcome these limitations, this study introduces a LightGBM-based impact localization framework specifically tailored to the anisotropic mechanical behavior and signal characteristics of carbon-fiber honeycomb structures. The proposed algorithm integrates gradient-based unilateral sampling with mutually exclusive feature binding. It utilizes time-domain signals with reduced sample data for impact localization, thereby reducing the required number of samples. Additionally, it employs FBG sensors for impact localization with reduced interference from electromagnetic signals. This improves model efficiency while reducing the number of feature dimensions, thereby preventing overfitting. The proposed method enables fast and accurate impact localization in honeycomb sandwich structures.

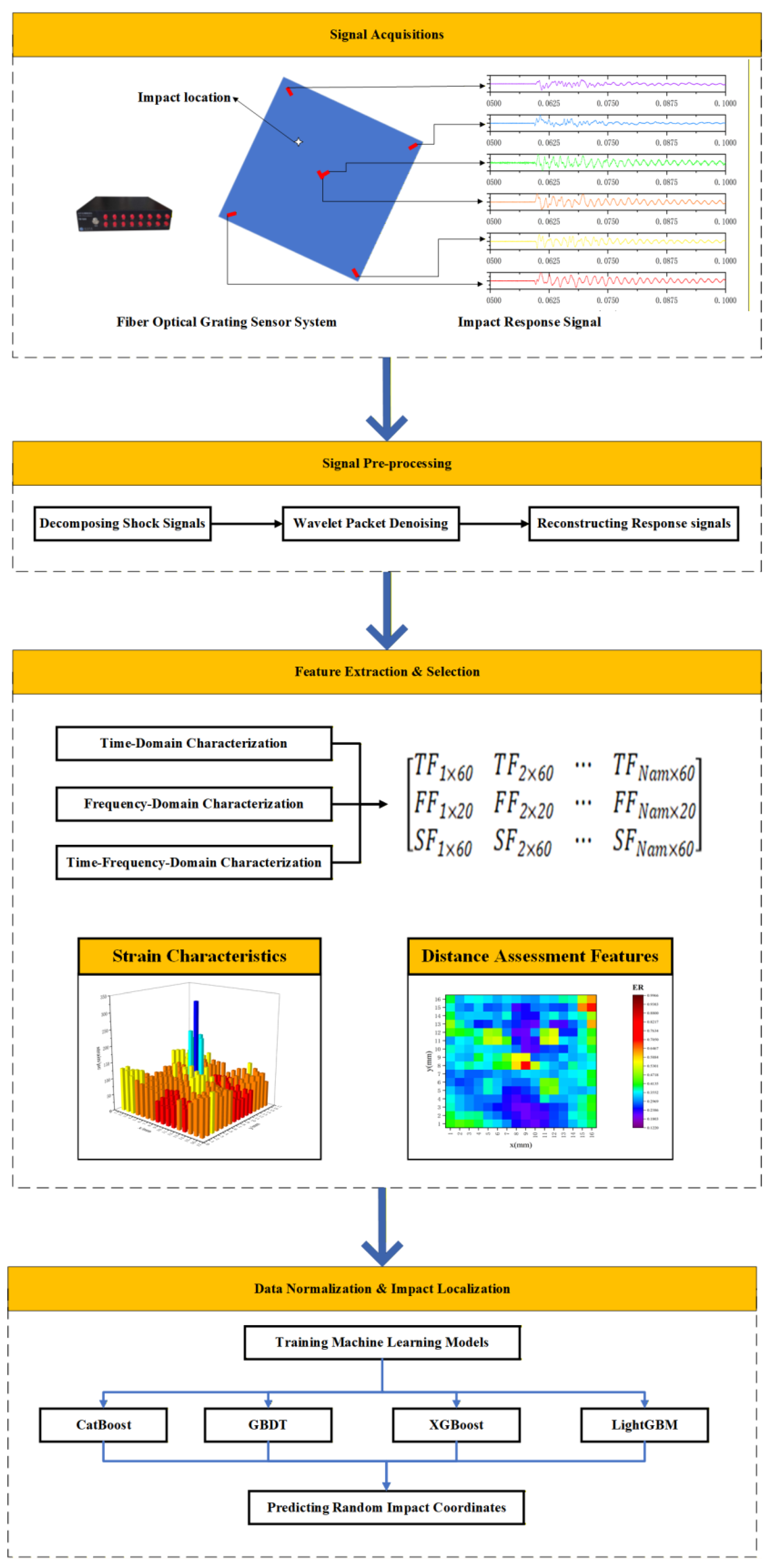

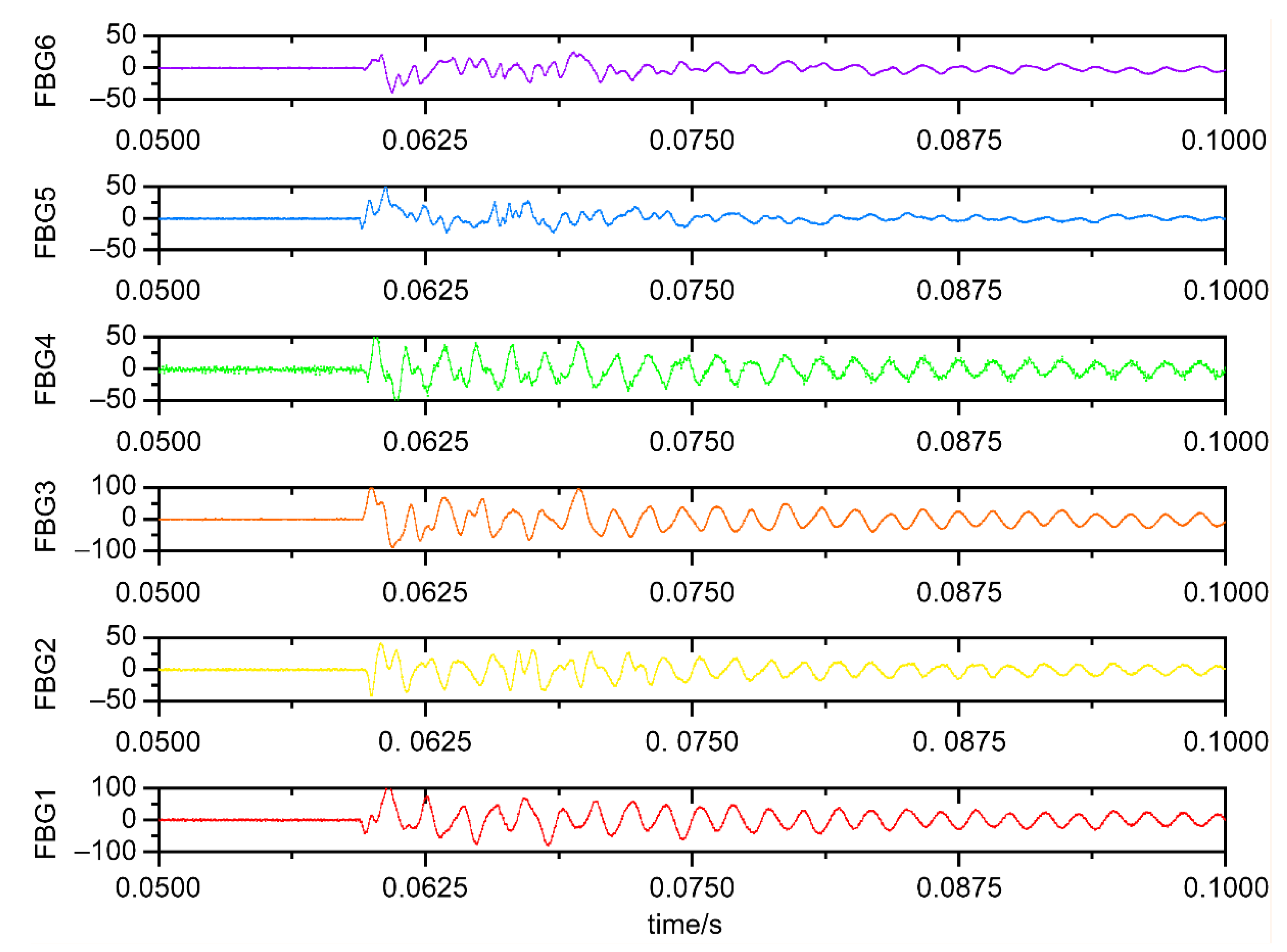

Building upon this motivation, the present study integrates FBG sensing with LightGBM learning to enhance low-energy-impact localization accuracy for honeycomb composites through combined experimental and computational validation. It methodically integrates signal-processing technology, feature-extraction methods, and machine-learning methods to develop a low-energy impact localization method for composite honeycomb boards. It addresses the challenge of low accuracy in the low-energy impact localization in board structures when utilizing a high-frequency sampling fiber grating sensing system. First, a low-energy impact experimental system for honeycomb sandwich composites was constructed, and a method based on empirical modal decomposition was explored to eliminate trend components from the impact response signal. The time-domain, frequency-domain, and time‒frequency-domain features were extracted and integrated. The wavelet-packet characteristics of the impact response signal were analyzed using the wavelet-packet decomposition method. A novel impact feature extraction method was developed, and the impact region was identified based on a set of wavelet packet features. The impact features and regions were established. The identification method models the relationship between impact features and the distance from the low-energy impact to the FBG sensor. Additionally, a low-energy impact localization method for honeycomb sandwich composites based on a LightGBM-based model is proposed. Furthermore, the performance of the impact localization method was evaluated, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the experimental setup,

Section 3 details the proposed algorithm,

Section 4 discusses results and validation, and

Section 5 presents conclusions.

2. Experiments

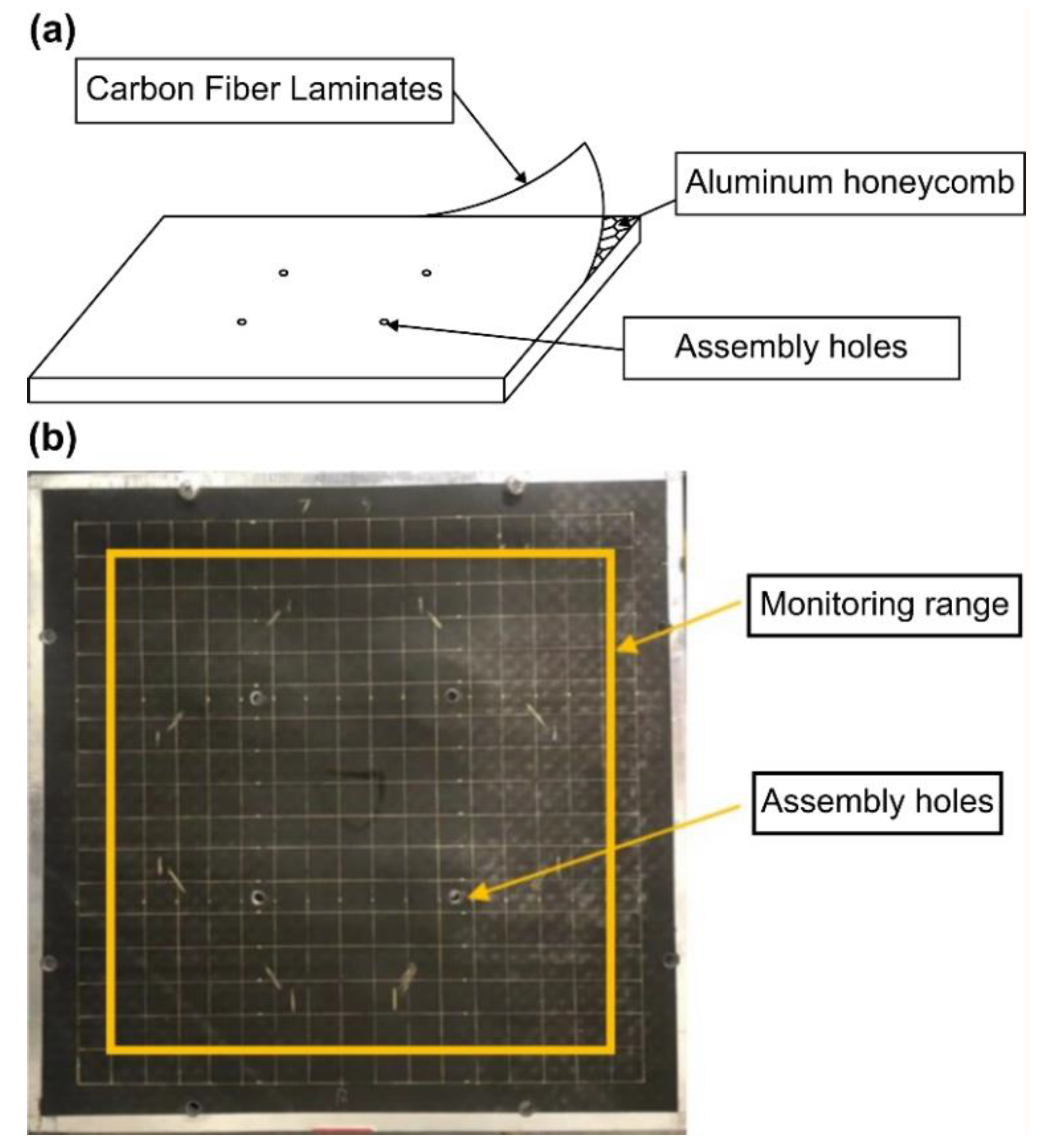

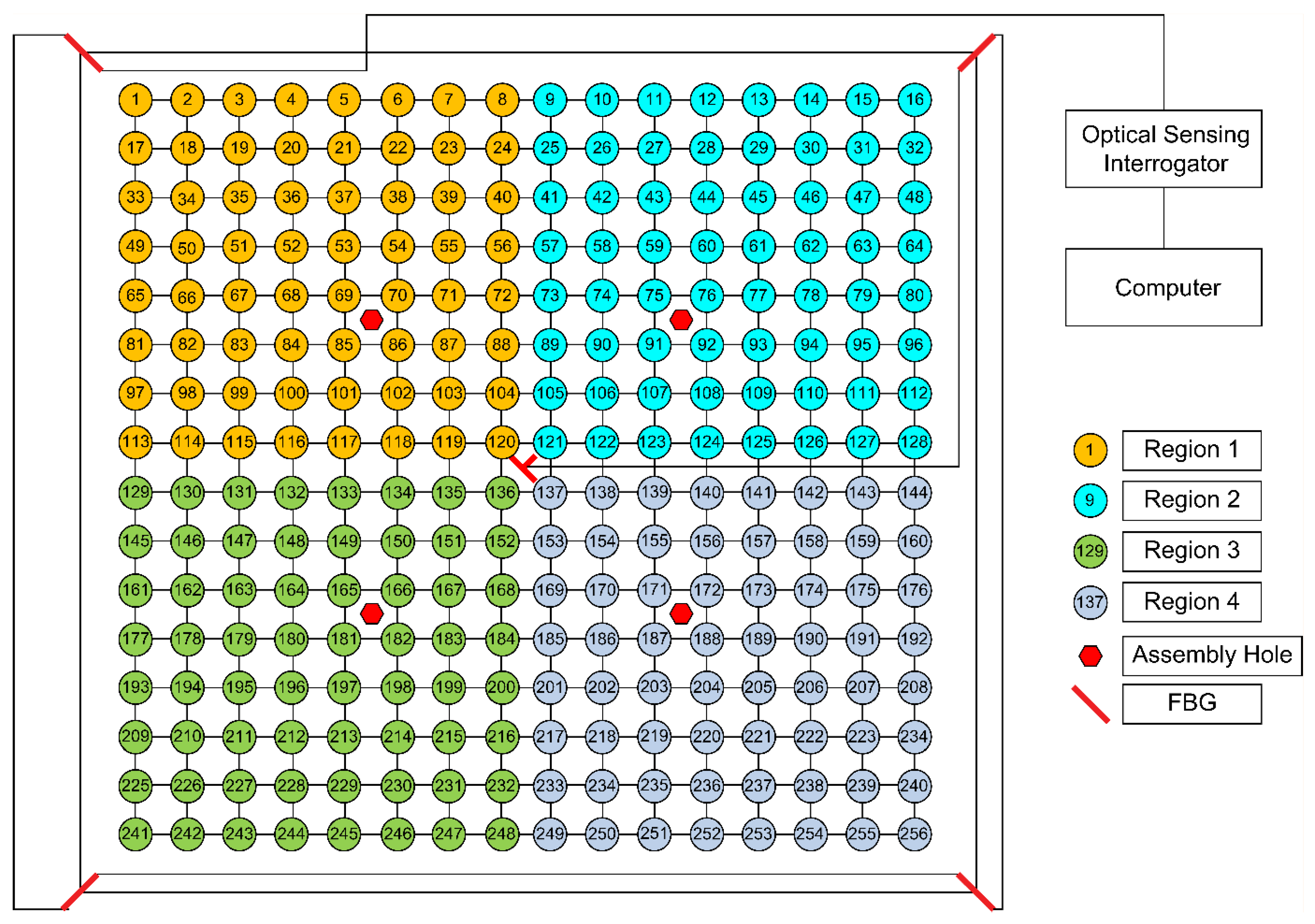

This study used a carbon-fiber aluminum honeycomb sandwich panel with assembly holes measuring 300 mm × 300 mm × 15 mm. The upper and lower surfaces of the sandwich panel consisted of 1-mm-thick T700/AG80 carbon fiber cladding, and the core layer was a hexagonal aluminum honeycomb with a wall thickness of 0.3 mm. A schematic of the test piece is shown in

Figure 2. The tested area, excluding the edge cladding and assembly holes, was 255 mm × 255 mm. The measurement area was divided into square grids with a side length of 15 mm, resulting in 256 grid intersections. Impacts were applied at grid intersections. According to the working conditions of the actual composite honeycomb panel, the panel was secured using its assembly holes to simulate the loading of structural components during the operation of an actual aircraft.

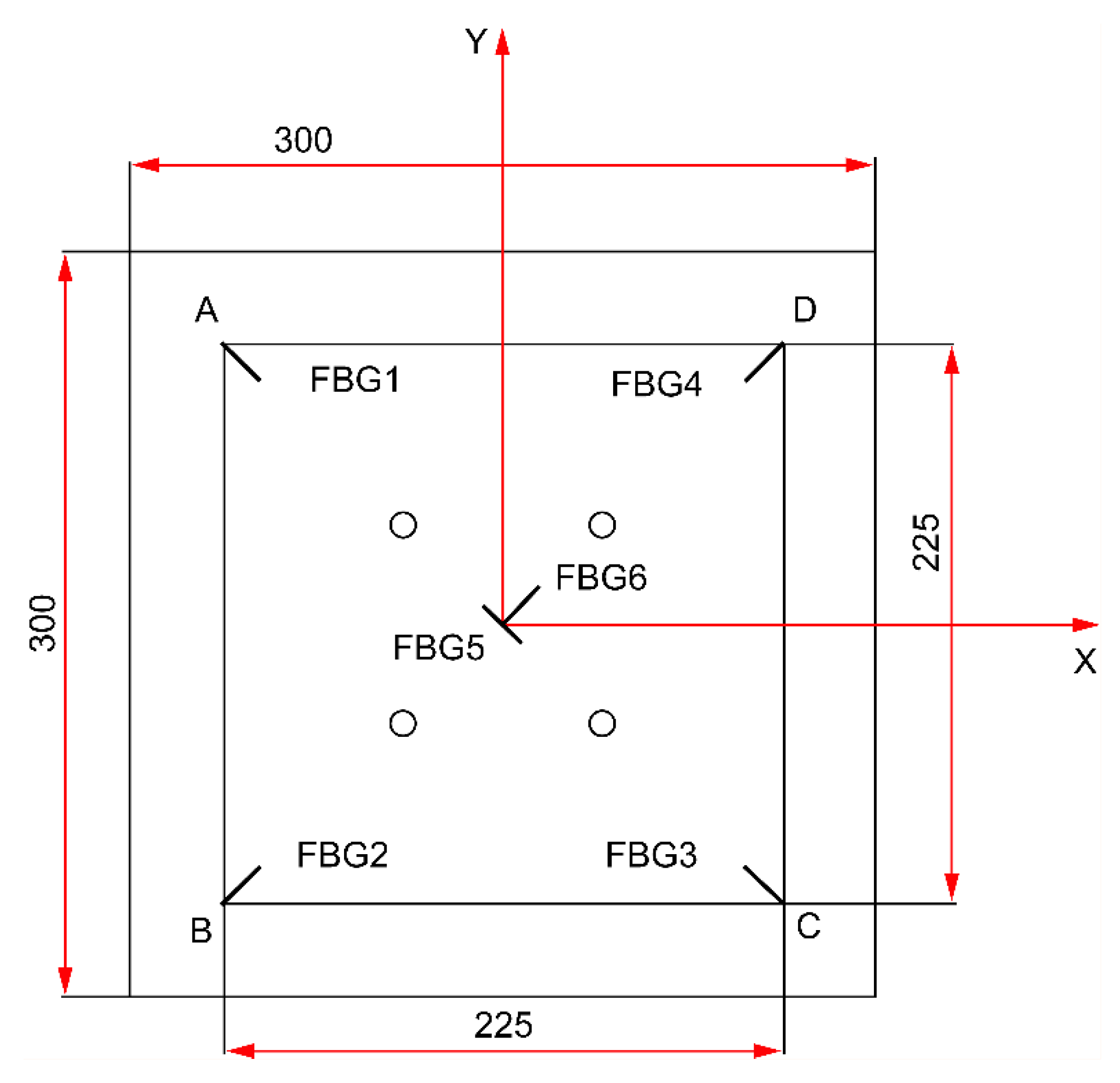

Six FBG sensors were affixed to the back of the specimen with the geometric center as the origin and the horizontal and vertical centerlines as the X and Y axes, respectively. The six sensors were affixed with the numbering shown in

Table 1; the specific arrangement is shown in

Figure 3. FBG5 and FBG6 were both positioned at (0, 0) to capture symmetric reference strains at the geometric center, enabling calibration and correction of signal drift near the assembly hole.

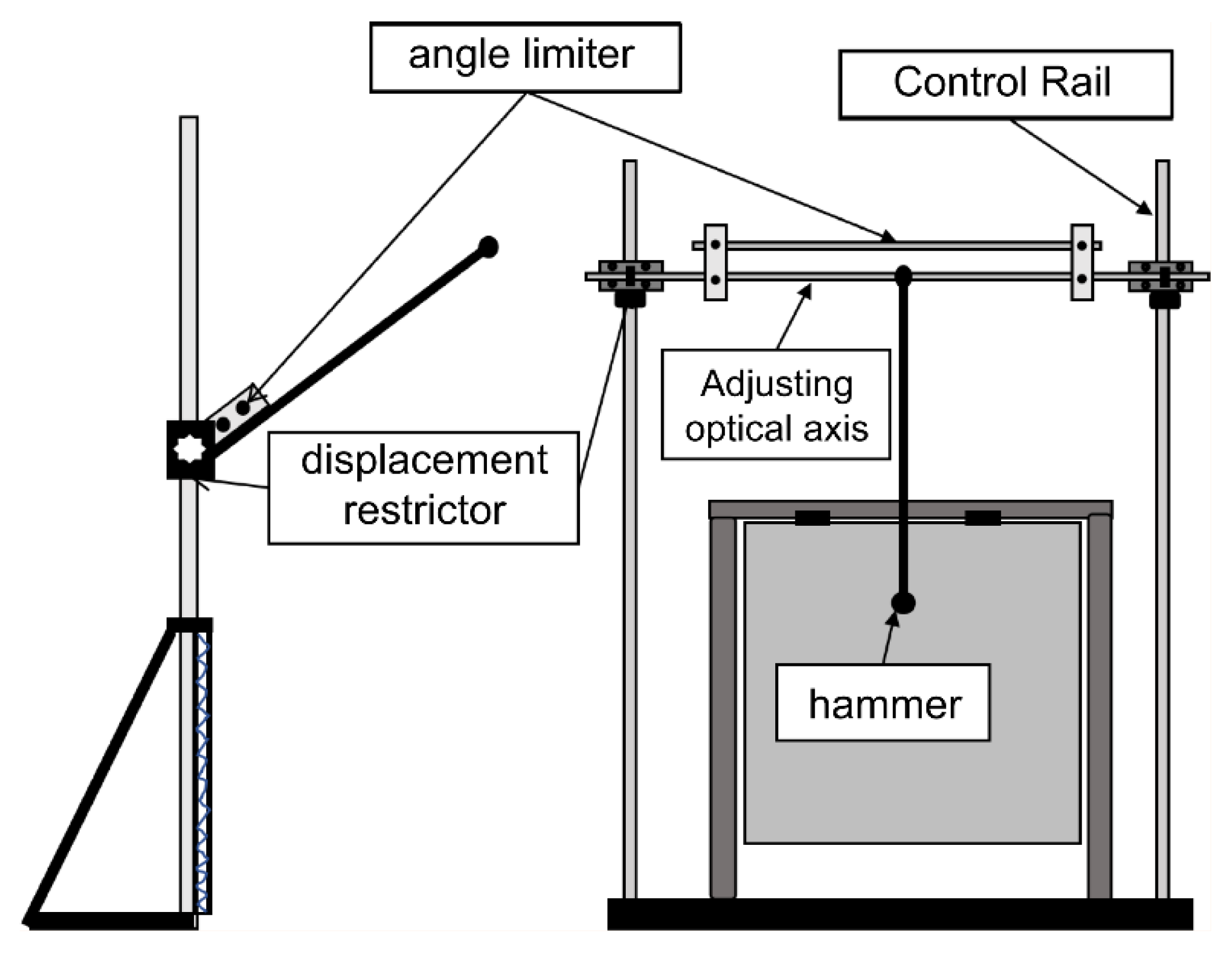

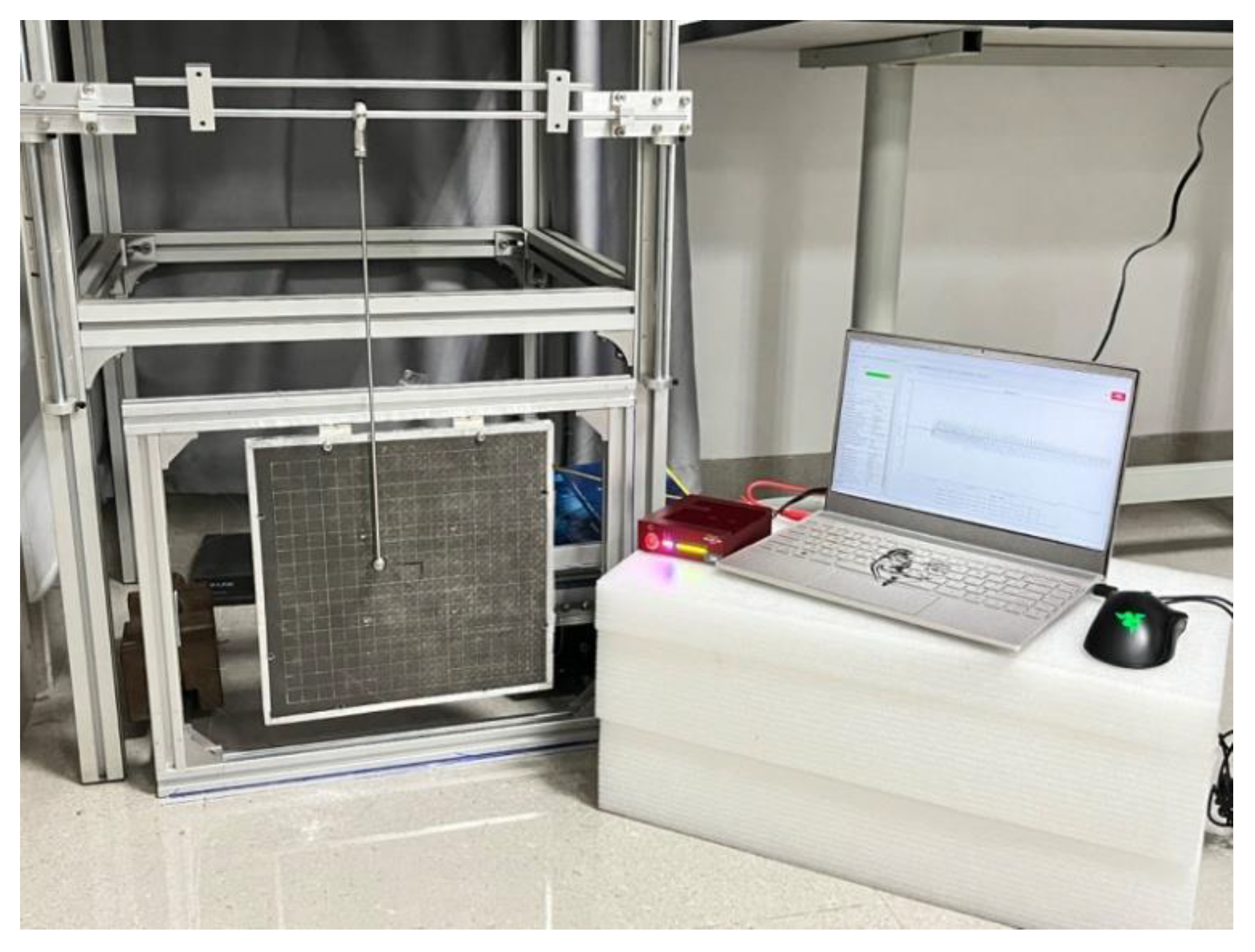

Figure 4 illustrates a localization device comprising an impact signal-generating system, including an impact pendulum and hammerhead, used to apply impacts to the test specimen, with adjustable pendulum length and hammerhead weight and size. The test specimen measured 300 mm × 300 mm × 15 mm, the pendulum length was 400 mm, the hammerhead diameter was 15 mm, and the combined pendulum weight was 55 g.

The test site plan is shown in

Figure 5, where the impact position adjustment device, including the height position adjustment slide, lateral position adjustment optical axis, and height limit device, was used to adjust the impact position of the impact hammer head up and down, and left and right, to ensure the accuracy of the impact position. The impact energy adjustment device, specifically the pendulum height angle limit device, used the pendulum height angle to control the impact energy.

4. Validation of Localization Results

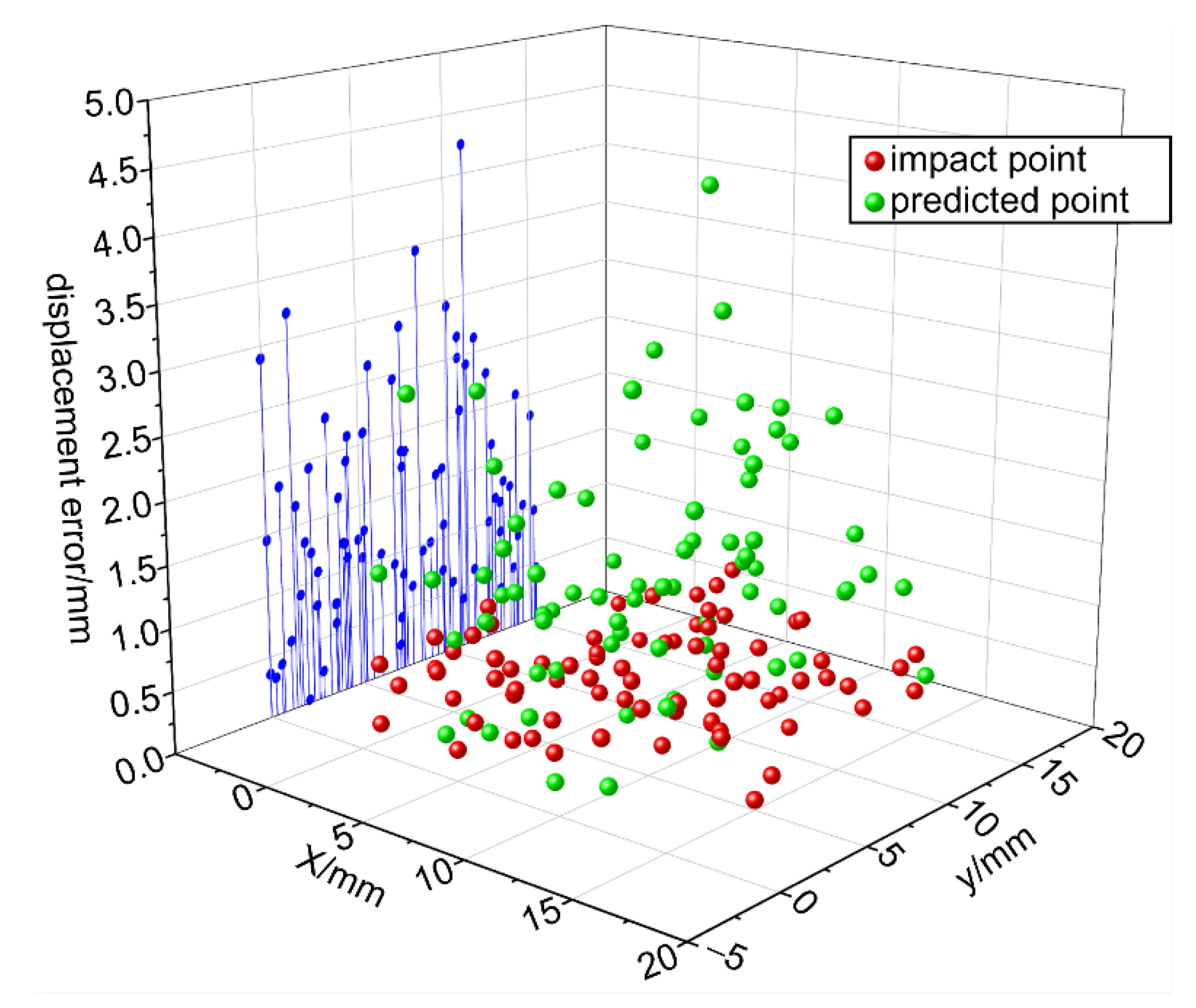

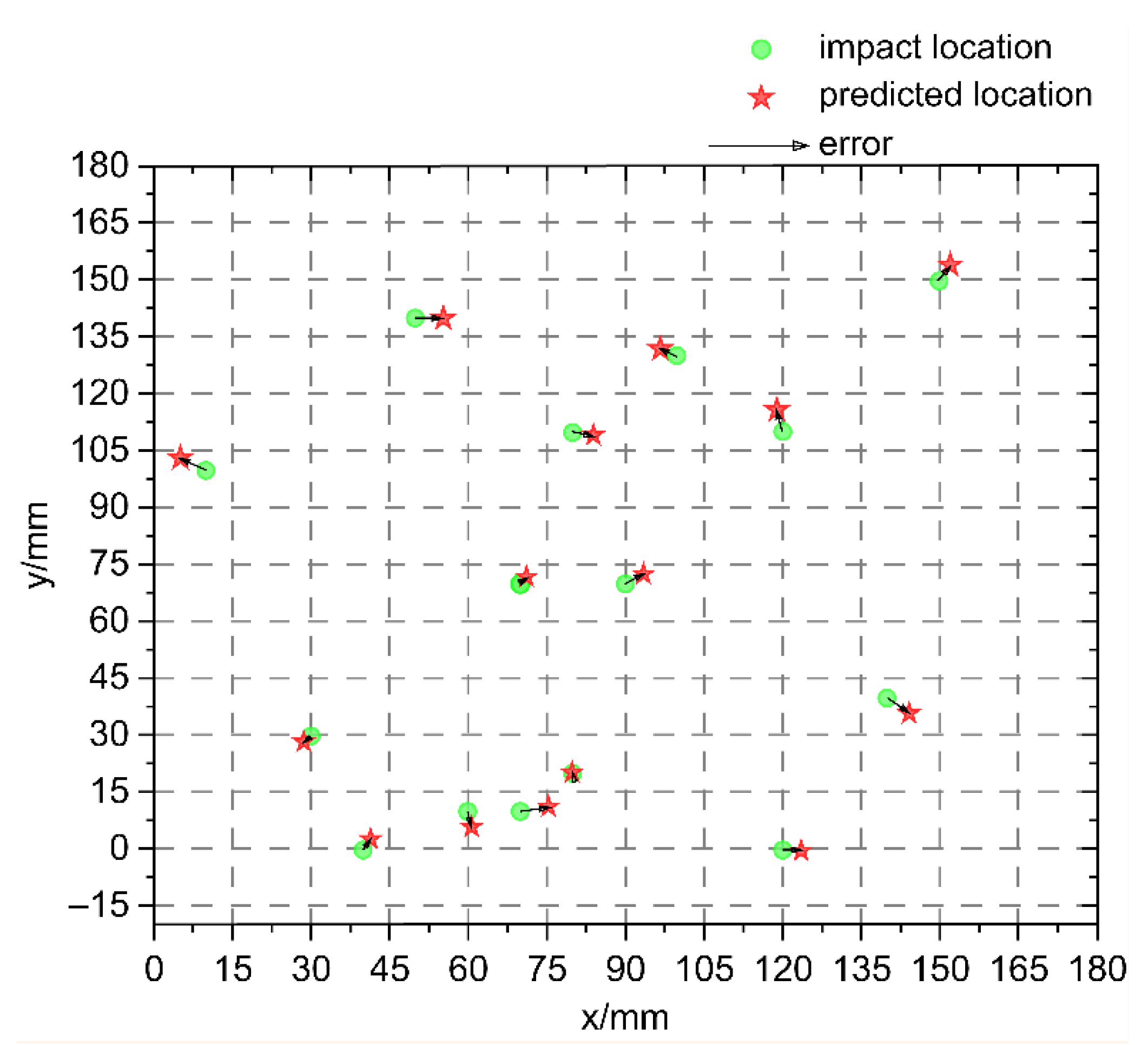

Figure 11 shows the nonbaseline locations designated for validation purposes. The total number of validation points was 60, and the proposed algorithm was used for impact localization. The localization results are also shown in

Figure 11. Compared to the grid size of 15 mm, the proposed LightGBM model achieved a maximum localization error of 4.24 mm and an average error of 1.40 mm, demonstrating a substantial improvement in spatial accuracy over conventional regression models. Despite the variation in the number of pre-measured signals, The findings not only demonstrate improved localization accuracy but also confirm that the proposed LightGBM-based approach effectively balances model complexity and generalization, offering a practical framework for structural health monitoring. These results validate the proposed algorithm, highlighting its ability to achieve high localization precision and computational efficiency in low-energy impact scenarios.

LightGBM offers several advantages over traditional GBM, including its histogram-based decision-tree algorithm, leafwise growth strategy, difference calculation technique, and support for distributed training. These enhancements improved efficiency, reduced memory consumption, and accelerated training when handling large-scale datasets. Additionally, it maintains high performance and accuracy while preserving efficiency and flexibility. The optimal parameters of LightGBM obtained after grid search optimization are listed in

Table 2.

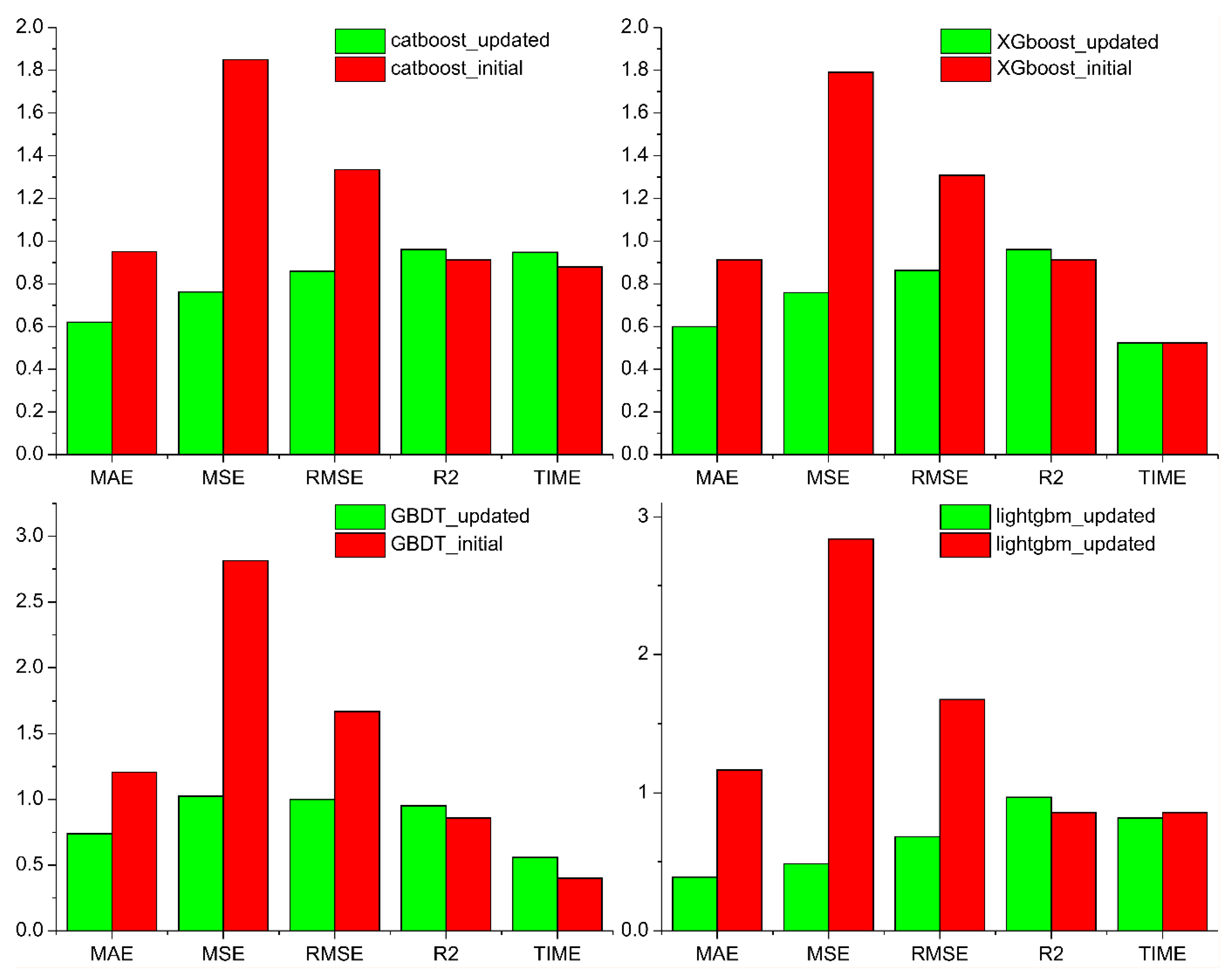

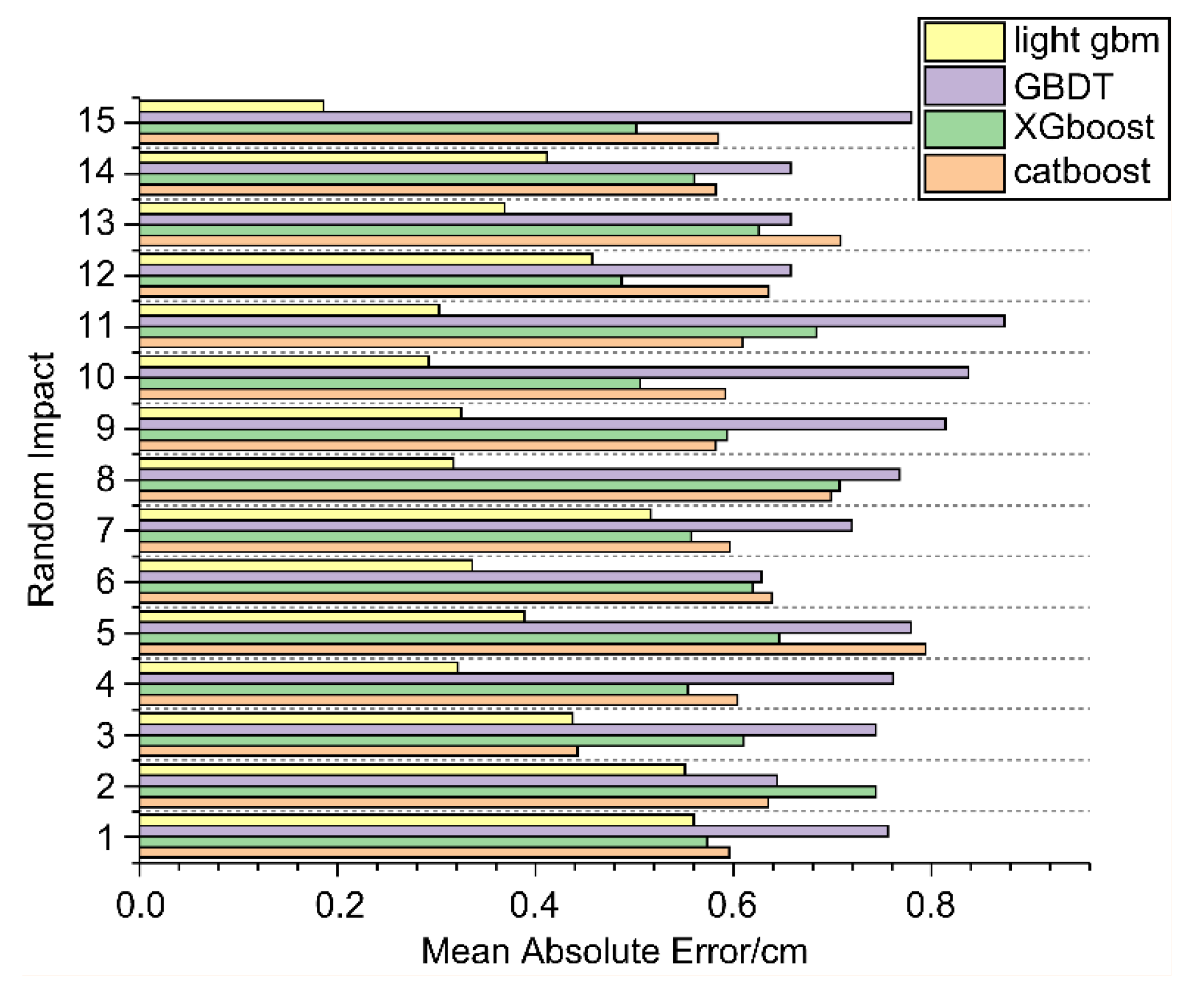

This section analyzes the performance of the LightGBM model in localizing low-velocity impacts in composite plates. To this end, a comparative analysis was conducted between the LightGBM model and three regression models: CatBoost, XGBoost, and GBDT. To ensure a fair comparison, the optimal subset of features obtained from the LightGBM model served as the input for all regression models. The number of multi-domain features corresponding to the horizontal coordinates of the shock was 255, whereas the number of multi-domain features corresponding to the vertical coordinates of the shock was 256. Each test was conducted independently 15 times.

Table 3 presents the mean absolute error (MAE) and root-mean-square error (RMSE) of the predicted coordinates of the 15 random shocks obtained from each model.

Figure 10 presents the localization error of each random shock obtained from the LightGBM model and the three contrasting regression models.

As shown in

Table 3, the LightGBM model achieved the smallest RMSE (10.2 mm) and MAE (5.8 mm) among all the tested models, outperforming XGBoost, CatBoost, and GBDT with statistical significance (p < 0.05).The experimental findings demonstrated that the mean localization error when the LightGBM algorithm was employed was 5.8 mm, addressing the challenge of impact signal localization in composite honeycomb sandwich panels.

As indicated by

Table 3 and

Figure 12, the LightGBM algorithm outperformed baseline boosting models by reducing both the MAE and RMSE, demonstrating stronger generalization capability due to its leafwise growth and histogram-based split strategy. For the 15 random shocks, the localization error, maximum localization error, minimum localization error, and average localization error of each random shock obtained from the LightGBM model were considerably smaller than those obtained from the CatBoost, XGBoost, and GBDT models.

In summary, when the same subset of optimal features is used as input to the regression model, the LightGBM model provides higher localization accuracy for random shocks in the monitoring area of honeycomb sandwich composites compared to the three other regression models. In

Figure 13, the LightGBM predictions closely align with measured impact coordinates, confirming the model’s stability and robustness under varying impact locations.