1. Introduction

THE analysis of movements produced by muscles plays a vital role in studies of sport biomechanics as well as in various clinical applications, in which the information on muscle activity supports proper diagnosis and medical decisions, treatment and/or rehabilitation [

1]. Electromyography (EMG) is a fundamental measurement technique used to detect the electrical activity of muscles by applying either needle EMG or surface EMG (sEMG). While both approaches have been extensively studied, sEMG has garnered significant attention due to its non-invasive nature and a broad range of applications in: 1) classification of the human movements, human gait or posture analysis; 2) control of exoskeleton, robotic arm or prosthetic devices, especially using wearable sensors; 3) human-machine interaction (interface); 4) diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]

Recent advancements in Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) have significantly enhanced the analysis of EMG data, particularly in the application of classification of EMG patterns to recognize limb or hand movements in different physical activities. In literature one can find evidence referring to application of various supervised ML techniques for EMG pattern recognition, e.g., Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Logistic Regression (LR), Naive Bayes, Extra Tree, Ensemble Bagged Trees and Ensemble Subspace Discriminant [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

23,

24]. For example, the study [

26] identifies the efficiency of ML algorithms, including SVM, LR, and artificial neural network (ANN) by using collected sEMG data to recognize seven shoulder motions of healthy subjects. This study presents that mean values of the highest accuracy are 97.29% of SVM, 96.79% of ANN and 95.31% of LR. Furthermore, the study [

27] uses the K-NN classifier and declares 99.23% peak accuracy of classification of sEMG features (recorded over relaxation, holding a pen, grabbing a bottle, and lifting a 2-kg weight). Moreover, a research [

28] compares results of K-NN and RF classifiers created to separate sEMG data collected from upper-limb muscles at different angles of forearm flexion. This study concludes that RF outperformed K-NN by achieving higher classification accuracy.

Advanced AI techniques, such as deep learning models, have also been explored in the field of biomechanics. For instance, the paper [

29] presents a model with a hybrid architecture of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to classify the human hand activity by using sEMG data obtained from

publicly available databases (external ones) [

24,

30]. The authors [

29] present results of average classification accuracy that are in the range [82.2; 97.7]%. Furthermore, the study [

10] presents high accuracy results of the CNN-based view pooling technique to recognize the gestures by considering sEMG data. To classify hand gestures in dexterous robotic telemanipulation, the paper [

25] compared multiple approaches of ML, including RF, CNN along with transformer-based models. This paper indicates that while deep learning models showed high accuracy, RF provided an optimal trade-off between a prediction time and classification performance that might be treated as well-suited for real-time applications.

An evidence referring to the fusion of electroencephalography (EEG) and sEMG signals for classification has shown promising results, particularly in applications to control a wearable exoskeleton. For example, the paper [

31] describes the feasibility of a CNN-based EEG-EMG fusion approach for multi-class movement detection and presents an average classification accuracy of 80.51%. Moreover, the study [

11] presents a hybrid human-machine interface used for classification of gait phases by applying the Bayesian fusion of EEG and EMG classifiers.

To improve the efficiency of feature extraction from sEMG data, the paper [

32] describes an implementation of Smooth Wavelet Packet Transform (SWPT) and a hybrid model composed of CNN and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) enhanced with a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) along with fused accelerometer data. This study reports an average accuracy of 92.159% for gesture recognition tasks. Furthermore a study [

33] reports 92% accuracy of sEMG data multi-classification by applying the Back-Propagation– LSTM model to recognize six motions, however, the authors did not specify these motions in details.

Among traditional pattern recognition methods, one can find evidence related to the application of ML algorithms that include K-NN, SVM, RF, and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [

34]. These classifiers are favored for their simplicity, very fast computation times, and high accuracy. Furthermore, one can find studies that describe an application of ANN to analyze EMG data [

35]. Moreover, the paper [

36] proposes to use a „symbolic transition network” to estimate a fatigue index based on sEMG data features. On the other hand, the study [

37] describes the ensemble classifiers, including RF, along with SVM and ANN to recognize neuromuscular disorders by using clinical and simulated EMG data.

It is worth noticing that to classify the human motions by using sEMG data, one should solve a problem related to the compositions of the EMG features, especially one should select a proper domain (time, frequency or time-frequency) along with a proper type of data (subject-wise or group of subjects). Also, this problem should be related to the applied measured sEMG device, e.g., low sampling sEMG device (e.g., Myo Armband [

40]), clinical sEMG device or high density sEMG device [

38,

39,

41,

43]. Moreover, a proper metric (metrics) should be defined to analyze results obtained from sEMG features [

42].

The purpose of this study was to verify the following hypothesis: it is possible to recognize motion patterns by separating electrophysiological data (sEMG time-series) by applying ML classifiers. In the scope of this study, we tested the following ML algorithms implemented in the MATLAB environment: Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines, Linear Discriminant and Quadratic Discriminant, K-Nearest Neighbors, and Efficient Logistic Regressions.

The main contributions of this work is testing whether sEMG time series collected on the chosen superficial muscles of both upper limbs over performing chosen physical activity in defined conditions can be used to recognize motion patterns by using ML models.

2. Materials and Methods

To recognize motion patterns and to assess accuracy of chosen ML models the sEMG data (EMG data) and acceleration data had been collected on a group of 27 healthy subjects: 16 males (age 22.81 ± 3.43 years, height 184.19 ± 5.81 cm, weight 81.59 ± 13.44 kg), and 11 females (age 22.33 ± 3.67 years, height 166.33 ± 5.81 cm, weight 61.67± 7.43 kg). Subjects tested in this study were without any musculoskeletal, postural, neurological, and psychological disorders. Non-invasive testing was accepted by the Ethics Committee (Ethics Committee Approval of Gdansk University of Technology from January 29, 2020). Each examined subject signed informed consent before an examination. The study was conducted at the Laboratory of Biomechanics (Gdansk University of Technology, Gdansk, Poland).

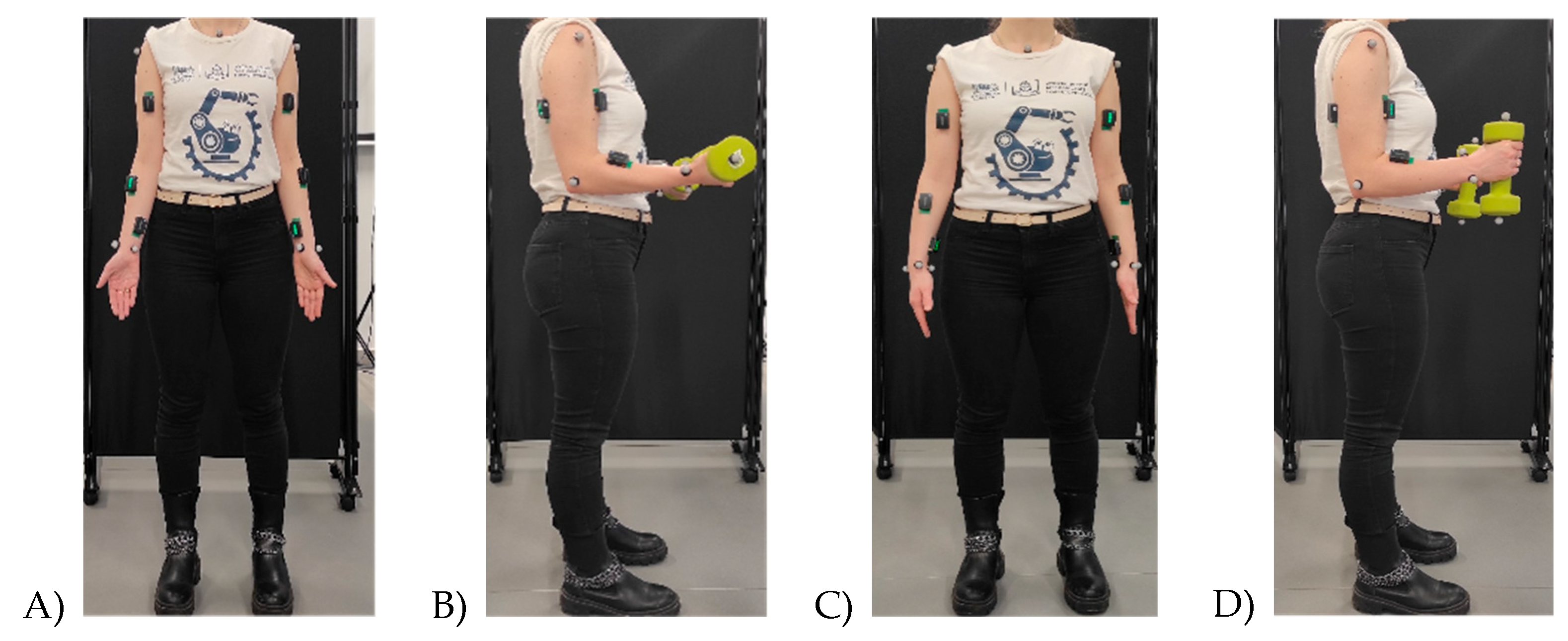

In this study, we used an experimental protocol that covered

two main stages performed in the given order: the first was

a supination stage (related to forearm supination configuration) and the second was

a neutral stage (related to forearm neutral configuration). Each main stage covered alternatively occurred

6 initial positions along with 5 or 6 target positions (the number depended on the subject physical condition) (

Figure 1). The initial position was to maintain fully extended upper limbs along the body without keeping up any external weight and trying to maintain both forearms in given configuration (supination in supination stage, and neutral in neutral stage) over minimum 20 seconds.

The target position was to maintain both forearms in a given isometric configuration (supination in the supination stage, and neutral in the neutral stage) while both forearms and arms were flexed at the elbow joints at the right angle in a sagittal plane and were simultaneously loaded with a 3 kg dumbbell that was maintained through a hand grip over 10 seconds. It is worth noting that in each target position two dumbbells were simultaneously given to the subject by the investigator, and after a defined time range, these external weights were simultaneously taken away by the investigator, and after that, the subject was able to return to the initial position. During the whole test, which encompassed two main stages, each subject was asked to stand on both feet (in shoes, feet apart) by maintaining the same erect configuration of trunk without performing motions in both humeral joints (glenohumeral joints) and shoulder girdle joints.

Before running an examination, each subject was given a demonstration of the initial and target positions in each main stage, and after that he/she familiarizes himself/herself with the demonstrated activities. After this, an experimental protocol was conducted. The number of trials (6 initial positions and 5 (or 6) target positions in each main stage) was chosen to avoid fatigue along with the learning effect. Each trial was performed by providing verbal instructions. After finishing each stage, the subject was given a minimum 5-minute break. An assessment of maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) was conducted after finishing the whole examination and break by separately testing muscular system of each limb three times with at least 5 minutes break during each MVC testing.

To collect sEMG data and acceleration data, we used eight wireless Trigno Avanti™ sensors of Delsys Trigno

® Wireless Biofeedback System [

https://delsys.com/trigno-avanti/] distributed by the Technomex company. Each Trigno Avanti™ sensor (weight is 14 g mass and its dimensions are 27 x 37 x 13 mm) has an onboard configurable precision EMG unit and an inertial measurement unit (IMU). Each sensor was affixed to the skin by using a disposable Delsys adhesive sensor interface. EMG units measure surface EMG data without using any additional reference electrode. Eight Trigno Avanti™ sensors were attached on the properly prepared surface of the skin under the tested muscle bellies that were determined by a palpation. Each sensor was oriented in a specific way according to Delsys’ recommendation, i.e., four silver contacts were in a perpendicular direction with respect to the muscle fibers of each tested belly [

44]. Each EMG unit has an anti-aliasing filter set working in the frequency range [20;450]Hz with 1926 Hz sampling in an 11 mV range, whereas each IMU unit collects acceleration data with 148 Hz sampling in [-16g; 16g] range. The EMG resolution depth of the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) is 16 bits.

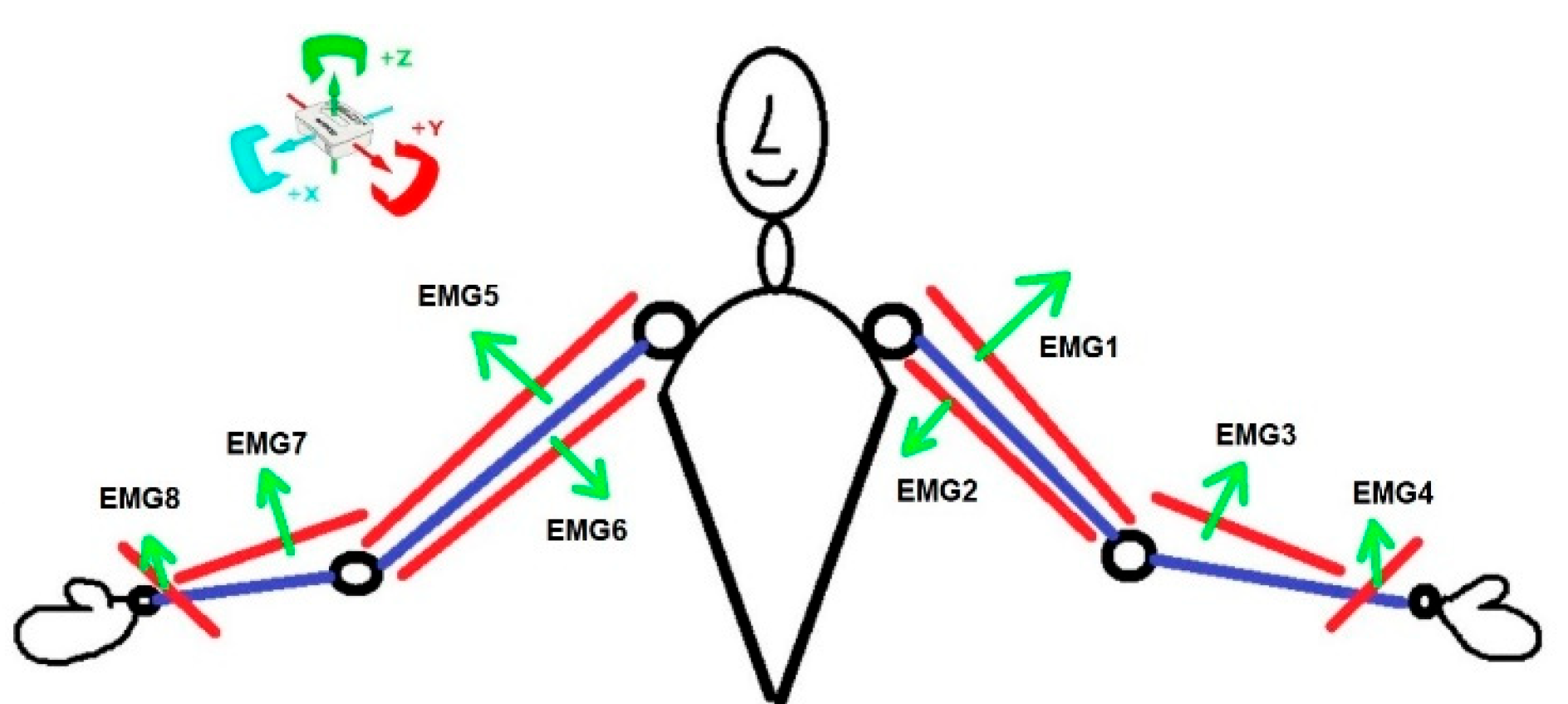

Eight Trigno Avanti™ sensors was affixed to the belly of the following muscles: left biceps brachii (EMG1), left triceps lateral head (EMG 2), left brachioradialis (EMG 3), left flexor digitorium superficialis (EMG 4), right biceps brachii (EMG 5), right triceps lateral head (EMG 6), right brachioradialis (EMG 7), right flexor digitorium superficialis (EMG 8) (

Figure 2). Tested muscles are superficial muscles that had been chosen on the base of reports described in [

36] and [

45]. In each main stage, an initial position was labeled as “Relax”, whereas a target position was labeled as “Isometric” (

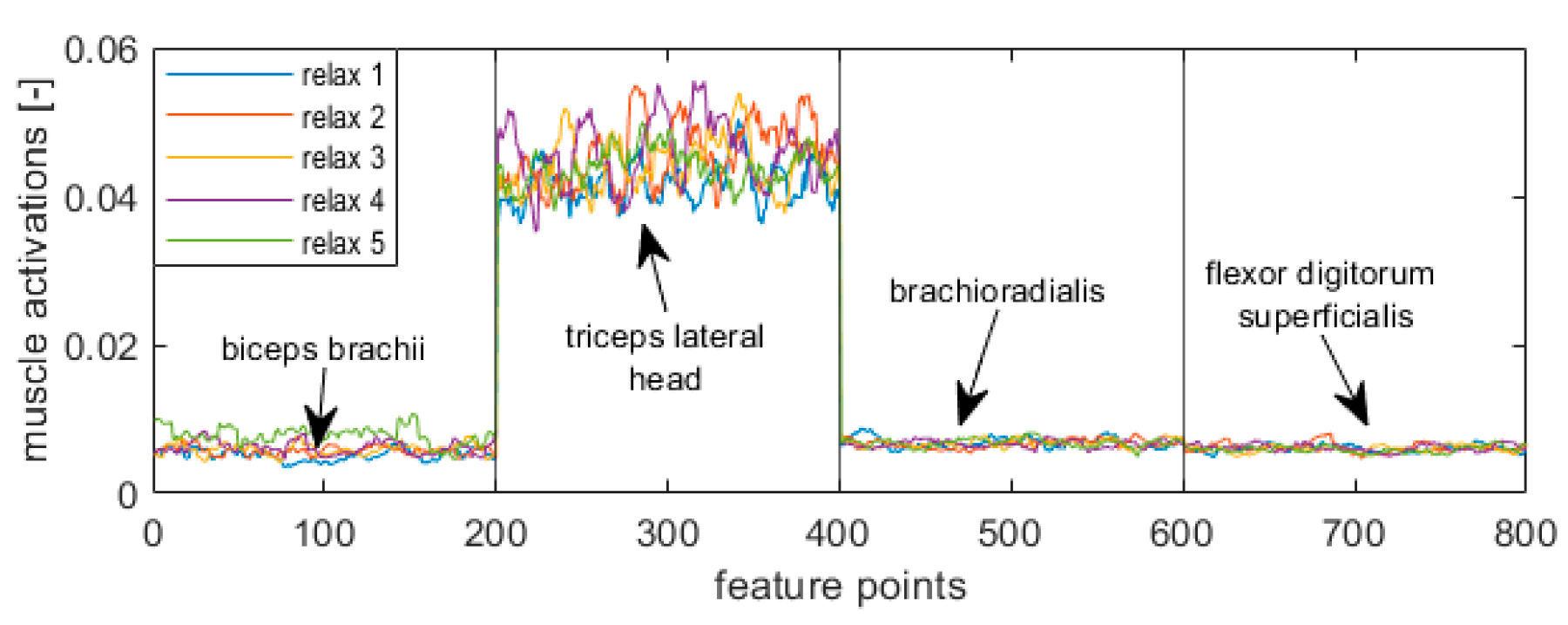

Figure 3A).

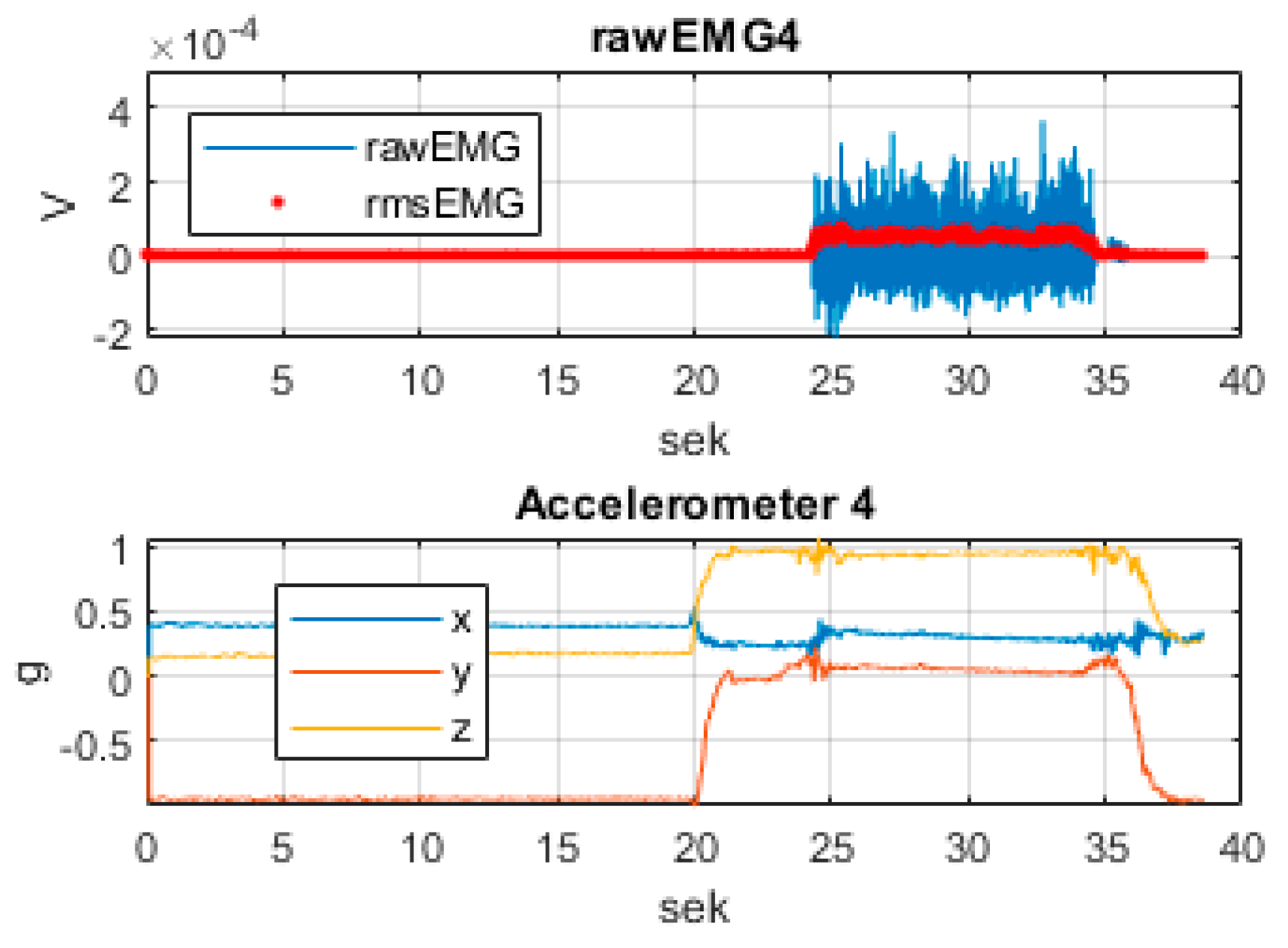

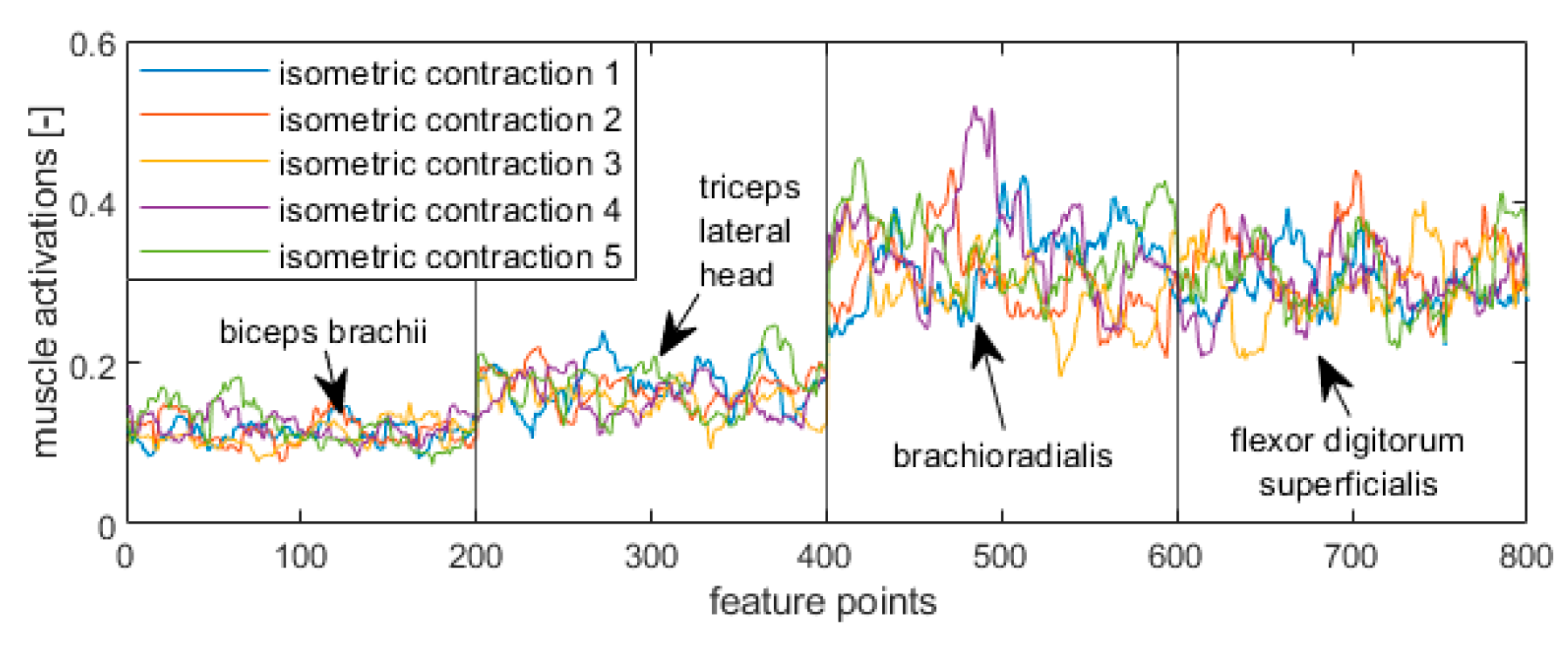

The commercial Delsys software (EMGworks Acquisition) was used to synchronously collect and record raw sEMG data along with ACC data. To process raw sEMG data, we used the EMGworks Analysis software to filter, rectify, and smooth by using the Root Mean Square (RMS) algorithm with a 125 ms window overlap that were adjusted to maintain the sampling rate of the collected original data. Processed sEMG (time series) were transmitted to MATLAB software (R2023b) to normalize with respect to MVC and to segment by using the author’s code written in MATLAB. A segmentation was performed based on the onset/offset of ACC data and supplemented by visual inspection. Next, each segment was normalized with respect to the motion timing (to 100%), resampled to 1000 points, and divided into five equal-length sections that were treated as five EMG patterns.

In this study, each feature was created by concatenating four EMG patterns referring to each upper limb into a single vector related to the left (time series of EMG1, EMG2, EMG3, EMG4) and to the right (time series of EMG5, EMG6, EMG7, EMG8).

To identify the most proper of ML classifiers that could be used to classify features composed of sEMG patterns, in this research we used four datasets composed of features: 1) for the right upper limb in a supination stage (730 initial / 730 target positions); 2) for the left upper limb in a supination stage (730 initial / 730 target positions); 3) for the right upper limb in a neutral stage (685 initial / 725 target positions); 4) for the left upper limb in a neutral stage (685 initial / 725 target positions). In

Figure 3B and

Figure 3C we put visualizations of features related to: 1) target position in a supination stage (

Figure 3B); 2) initial position in a supination stage (

Figure 3C).

To perform classification tasks, each database was randomly divided into balanced train and test groups (80% and 20%) by using k-fold cross-validation (k = 5). In the scope of this study, we tested twenty-three ML algorithms from the Classification Learner App (MATLAB R2023b):

- 1)

Decision Tree (Gini’s diversity index (Gdi), Twoing rule (Twoing), Maximum deviance reduction (Deviance)),

- 2)

Support Vector Machines (Linear (L-SVM), Quadratic (Q-SVM), Cubic (C-SVM) and Gaussian (G-SVM)),

- 3)

Linear Discriminant (LD),

- 4)

Quadratic Discriminant (QD),

- 5)

K-Nearest Neighbors (euclidean (K-NN euclidean), cityblock (K-NN cityblock), chebychev (K-NN chebychev), cosine (K-NN cosine), correlation (K-NN correlation), minkowski (K-NN minkowski), seuclidean (K-NN seuclidean ), spearman (K-NN spearman), jaccard (K-NN jaccard)),

- 6)

Efficient Logistic Regressions (average stochastic gradient descent (ELR asgd), stochastic gradient descent (ELR sgd), Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno quasi-Newton algorithm (ELR bfgs), Limited-memory BFGS (ELR lbfgs), Sparse Reconstruction by Separable Approximation (ELR sparsa)).

Hyperparameters that were used in the ML models presented in this study were selected using a trial-and-error method (Table S.I (in Supplement)). All three models of Decision Trees (Gdi, Twoing, and Deviance) were implemented using a maximum of 100 splits without surrogate decision splits. All four models of Support Vector Machines (L-SVM, Q-SVM, C-SVM, and G-SVM) were used with one box constraint level, auto Kernel scale mode, and standardized data. All nine models of K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN euclidean, K-NN cityblock, K-NN chebychev, K-NN cosine, K-NN correlation, K-NN minkowski, K-NN spherical, K-NN spearman, K-NN jaccard) were implemented by using one neighbor, equal distance weight, and standardized data. All five models of Efficient Logistic Regressions (ELR asg, ELR sgd, ELR bfgs, ELR lbfgs, ELR sparsa) were implemented by using auto regularization strength (Lambda) and relative coefficient tolerance (Beta tolerance) equal to 0.0001.

To recognize motion patterns we tested ML classification models by solving two main tasks:

- 1)

tasks A are related to classify: initial and target positions of the left arm in a supination stage (ASL); initial and target positions of the right arm in a supination stage (ASR); initial and target positions of the left arm in a neutral stage (ANL); initial and target positions of the right arm in a neutral stage (ANR);

- 2)

tasks B are related to classify: supination and neutral stages of the left arm in an initial position (BSNLI); supination and neutral stages of the left arm in a target position (BSNLT); supination and neutral stages of the right arm in an initial position (BSNRI); supination and neutral stages of the right arm in a target position (BSNRT).

These main tasks were solved in two steps. First, 23 classifiers were used to solve ASL and ASR tasks. Second, we analyzed performance results of these tasks and chose the best 15 classifiers (Twoing, Deviance, Q-SVM, C-SVM, G-SVM, QD, K-NN euclidean, K-NN cityblock, K-NN chebychev, K-NN cosine, K-NN minkowski, K-NN seuclidean, ELR bfgs, ELR lbfgs, ELR sparsa) to solve ANL and ANR tasks. Next, we used these chosen 15 classifiers to solve BSNLI, SNLT, BSNRI, and BSNRT tasks. To solve tasks A we used declared databases: 1) for supination stage we used 1460 features (730/730) to solve ASR and ASL tasks; 2) for neutral stage we applied random downsampling and used 1370 features (685/685) with to solve ANR and ANL tasks. Aiming to solve tasks B, we used declared datasets: 1) 1415 features to solve BSNLI and BSNRI tasks; 2) 1455 features to solve BSNLT and BSNRT tasks.

3. Results

Results of binary classification models were evaluated by using the following metrics: accuracy, recall (sensitivity), precision, and F1-score [

46]. The accuracy (ACC) was defined by the following equation:

where: TPR– true positive rate, TNR—true negative rate, FPR– false positive rate, FNR—false negative rate.

The recall (SEN), the precision (PPV) and F1-score (F1) were calculated by using following relations (2), (3) and (4):

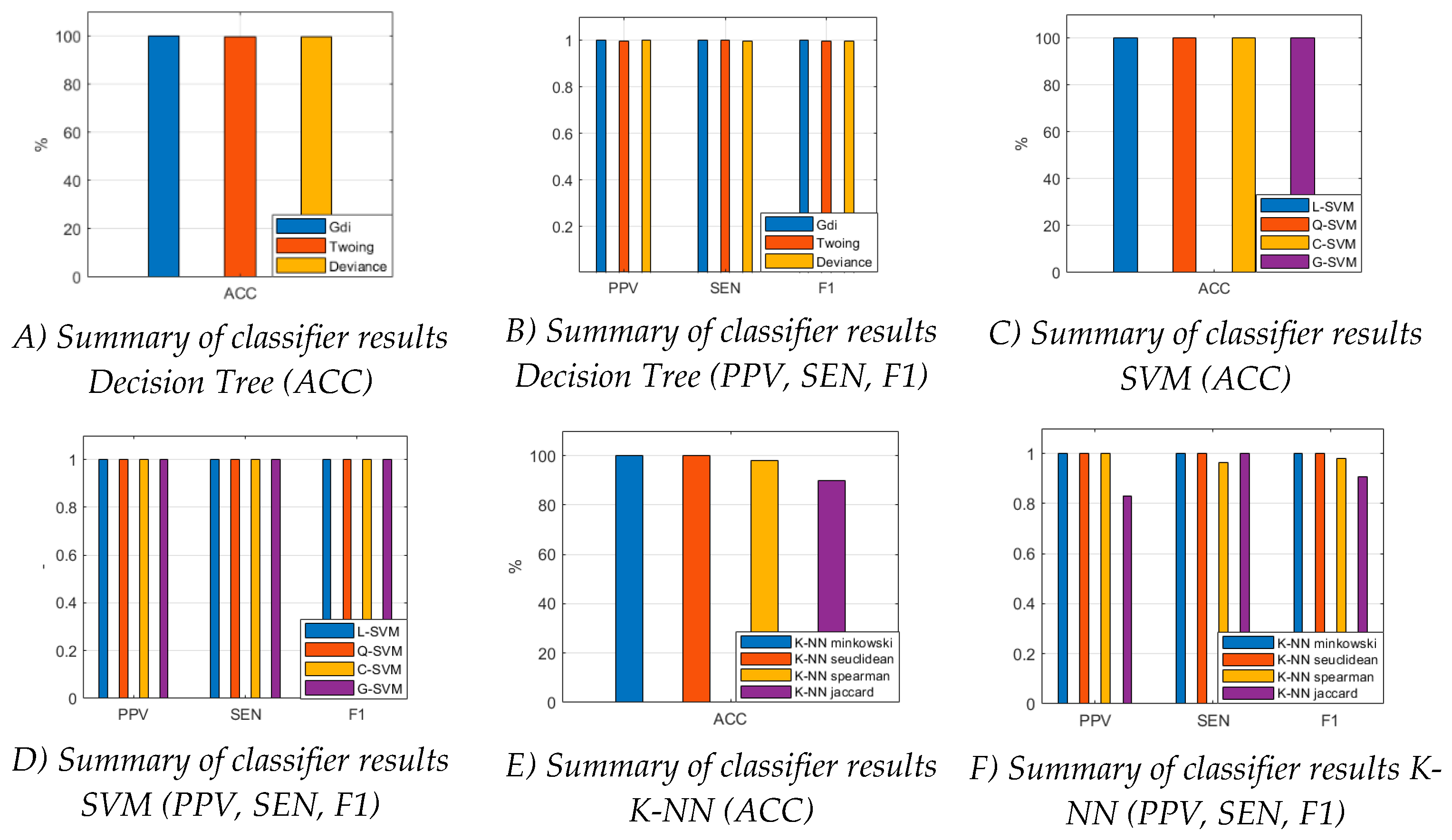

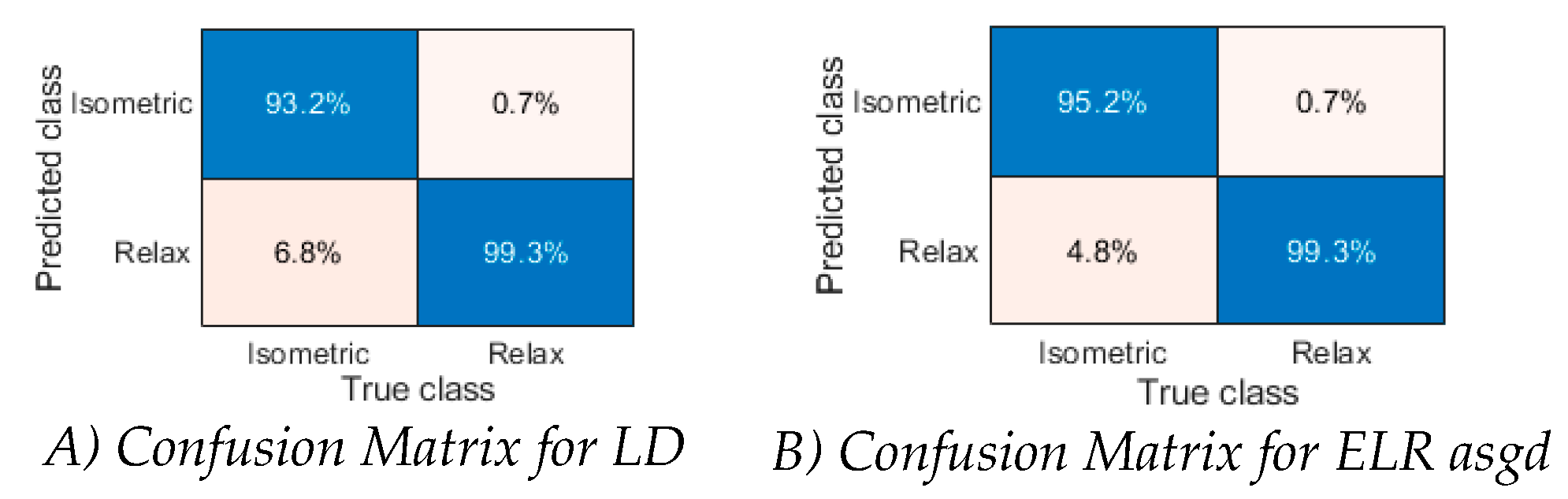

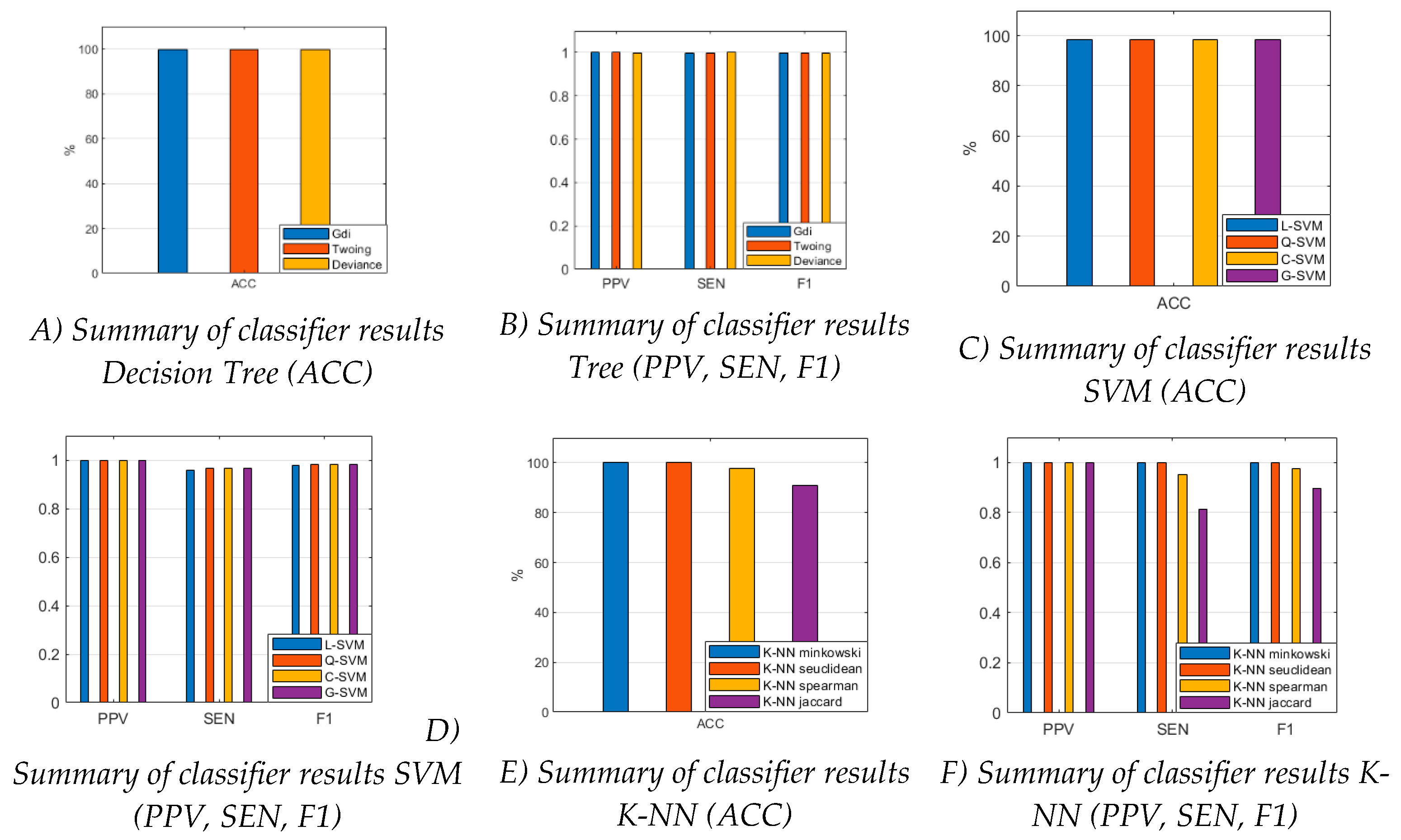

In this paper, we presented the results of the classification of a task:

Solving tasks A (ASL, ASR, ANL, ANR), results of classification (ACC, SEN, PPV, F1) are presented as an average by assuming that a target position was treated as a true rate, whereas an initial position was treated as a negative rate. Furthermore, results of classification of tasks B (SEN, PPV, F1) are presented as an average by assuming that: 1) a target position of neutral stage was treated as true rate, whereas a target position of supination stage was treated as negative rate for tasks BSNLT and BSNRT; 2) an initial position of neutral stage was treated as true rate, whereas an initial position of supination stage was treated as negative rate for tasks BSNLI and BSNRI.

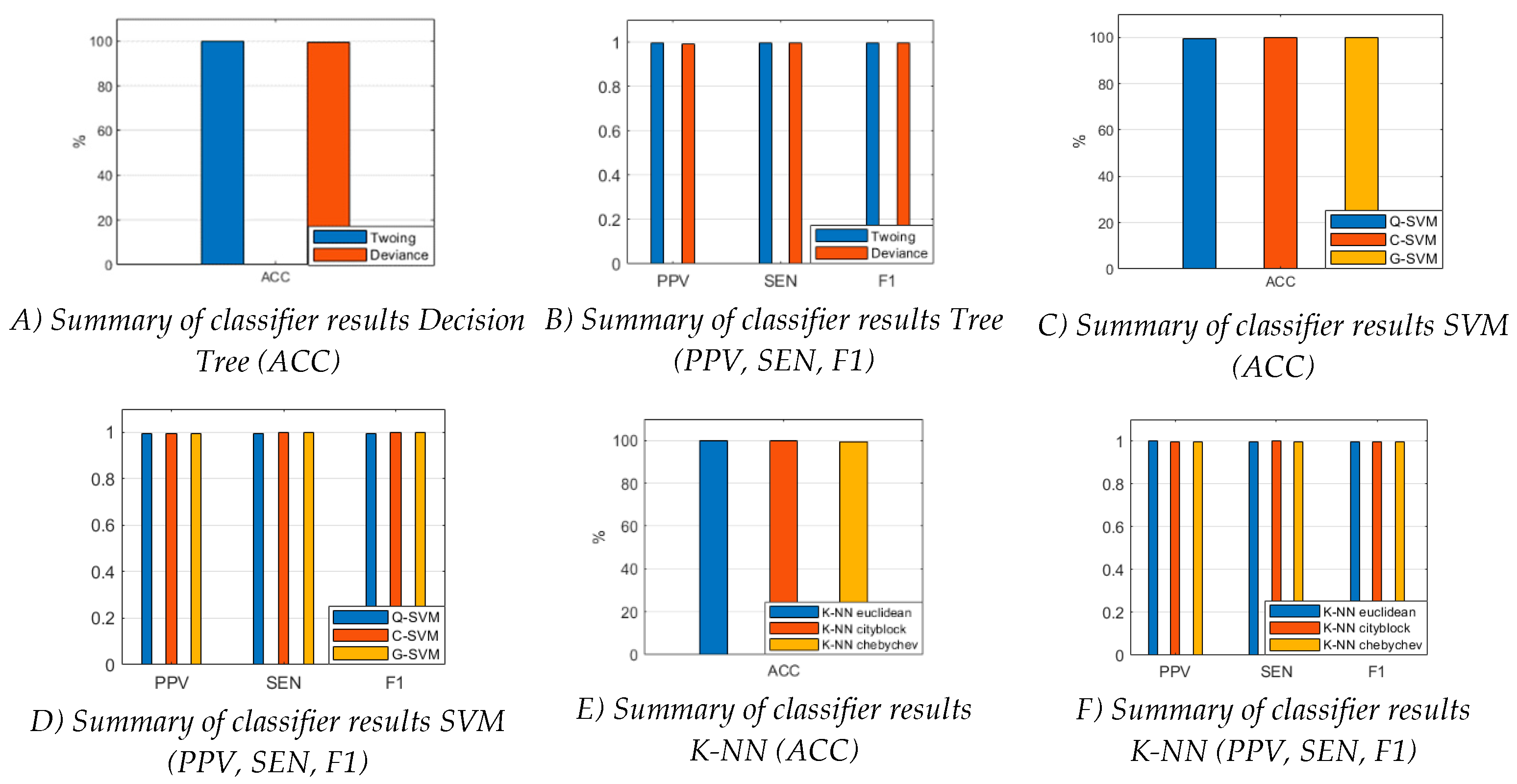

Considering results of ASL task, we identified the following ML models that split sEMG data with the highest performance related to:

- 1)

ACC equaled 100% along with F1 equaled 1.000 (L-SVM, Q-SVM, C-SVM, G-SVM, K-NN euclidean, K-NN cityblock, K-NN chebychev, K-NN cosine, K-NN minkowski, K-NN seuclidean, ELR bfgs, and ELR lbfgs, respectively);

- 2)

ACC equaled 99.772% (Twoing and Deviance), 99.658% (Gdi) and 99.543% (ELR sparsa);

- 3)

F1 equaled 0.998 (Twoing and Deviance), 0.997 (Gdi), and 0.995 (ELR sparsa).

Analyzing results of ASR task, we found the following ML models that classified sEMG data with the highest metrics:

- 1)

ACC equaled 100% along with F1 equaled 1.000 (K-NN cityblock, K-NN cosine, K-NN minkowski, and K-NN seuclidean, respectively);

- 2)

ACC equaled 99.886% (Twoing and Deviance), 99.658% (K-NN euclidean and K-NN chebychev), and 99.315% (Gdi);

- 3)

F1 equaled 0.999 (Twoing and Deviance), 0.997 (K-NN euclidean and K-NN chebychev), and 0.993 (Gdi).

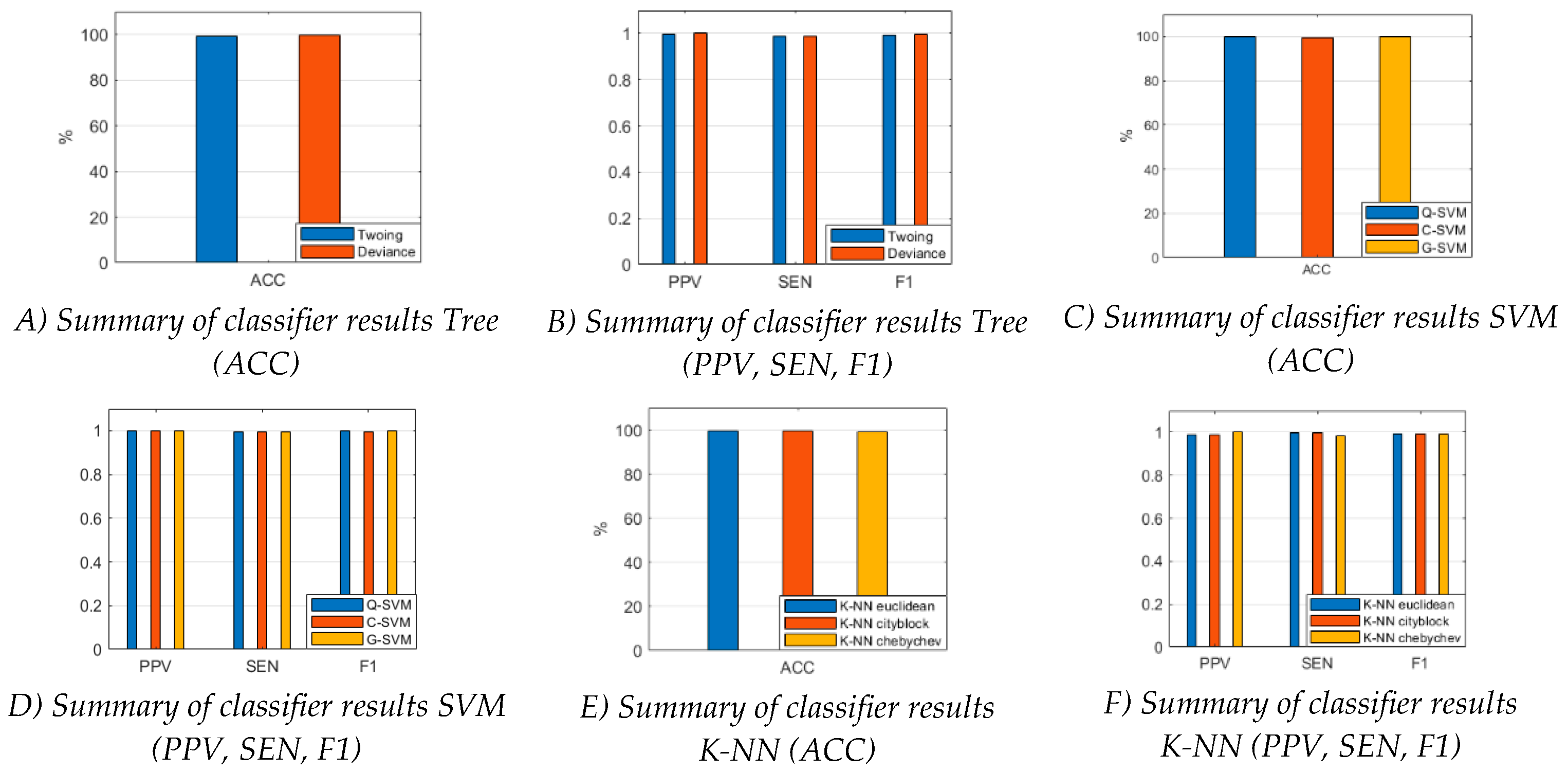

Next, we considered results of the classification of ANL task and identified the following ML models that split sEMG data with the highest performance:

- 1)

ACC equaled 99.765% (K-NN euclidean);

- 2)

ACC equaled 99.757% (C-SVM and G-SVM), 99.713% (K-NN cityblock), and 99.661% (K-NN seuclidean);

- 3)

F1 equaled 0.998 (C-SVM, G-SVM and K-NN euclidean);

- 4)

F1 equaled 0.997 (K-NN cityblock), 0.996 (Twoing and K-NN seuclidean) , and 0.995 (Q-SVM, K-NN chebychev, K-NN minkowski).

After this, we analyzed results of the classification of ANR task and identified the following ML models that separated sEMG data with the highest metric, referring to:

- 1)

ACC equaled 99.757% along F1 equaled 0.998 (K-NN seuclidean);

- 2)

ACC equaled 99.726% (Q-SVM and G-SVM), 99.635% (C-SVM) , and 99.513% (Deviance);

- 3)

F1 equaled 0.997 (Q-SVM and G-SVM), 0.996 (C-SVM), and 0.995 (Deviance).

Considering results of BSNLI task, we identified the following ML models that divide the sEMG data with the highest performance:

- 1)

F1 equaled 0.973 (K-NN cityblock);

- 2)

F1 equaled 0.971 (K-NN seuclidean), 0.966 (K-NN minkowski) and 0.962 (K-NN cosine).

Analyzing results of BSNLT tasks, we found the following ML models that separated sEMG data with the highest metrics:

- 1)

F1 equaled 0.996 (K-NN seuclidean);

- 2)

F1 equaled 0.993 (K-NN euclidean), 0.992 (K-NN minkowski and K-NN cityblock) , and 0.969 (K-NN cosine).

Next, we considered results of the classification of BSNRI tasks and identified the following ML models that split the sEMG data with the highest performance:

- 1)

F1 equaled 0.970 (K-NN euclidean);

- 2)

F1 equaled 0.966 (K-NN cityblock), 0.959 (K-NN seuclidean) and 0.957 (K-NN minkowski).

After this, we analyzed results of the classification of BSNRT tasks and deduced the following ML models that split the sEMG data with the highest metrics:

- 1)

F1 equaled 0.989 (K-NN euclidean);

- 2)

F1 equaled 0.986 (K-NN cityblock and K-NN minkowski), 0.985 (K-NN seuclidean), and 0.973 (K-NN cosine).

4. Discussion

In the scope of this study we applied supervised classification algorithms [

47] and tested chosen ML classifiers (Decision Trees, Support Vector Machines, Linear Discriminant, Quadratic Discriminant, K-Nearest Neighbors, Efficient Logistic Regressions) to recognize motion patterns by classifying time series features obtained from processed EMG data that were acquired from eight superficial muscles of two upper limbs over performing given physical activities. In this study, we only focused on the time domain of features composed of EMG patterns. We explored 23 ML classifier models to split the features obtained from a supination stage. Next, among these models we chose 15 models (with the best performance) to classify the features obtained from a neutral stage. After these, we applied these 15 models to classify data merged from the supination and neutral stages. All ML models explored in this study were trained and tested by using a database obtained from testing healthy subjects without division into sex (male 59% and female 41%).

Analyzing all results of classifications of tasks A (ASL, ASR, ANL, ANR), we identified the following ML models that allowed us to classify sEMG data with the highest performance:

- 1)

ACC for the left arm in a supination stage (ACC range is [99.543; 100.000]%): L-SVM, Q-SVM, C-SVM, G-SVM, K-NN euclidean, K-NN cityblock, K-NN chebychev, K-NN cosine, K-NN minkowski, K-NN seuclidean, ELR bfgs, ELR lbfgs, Twoing, Deviance, Gdi and ELR sparsa;

- 2)

ACC for the right arm in a supination stage (ACC range is [99.315; 100.000]%): K-NN cityblock, K-NN cosine, K-NN minkowski, K-NN seuclidean, Twoing, Deviance, K-NN euclidean, K-NN chebychev and Gdi;

- 3)

ACC for the left arm in a neutral stage (ACC range is [99.713; 99.661]%): K-NN euclidean, C-SVM, G-SVM, K-NN cityblock and K-NN seuclidean;

- 4)

ACC for the right arm in a neutral stage (ACC range is [99.635; 99.513]%): K-NN seuclidean, Q-SVM, G-SVM, C-SVM and Deviance;

- 5)

F1 for the left arm in a supination stage (F1 range is [0.995; 1.000]): L-SVM, Q-SVM, C-SVM, G-SVM, K-NN euclidean, K-NN cityblock, K-NN chebychev, K-NN cosine, K-NN; minkowski, K-NN seuclidean, ELR bfgs, ELR lbfgs, Twoing Deviance, Gdi and ELR sparsa;

- 6)

F1 for the right arm in a supination stage (F1 range is [0.993; 1.000]): K-NN cityblock, K-NN cosine, K-NN minkowski, K-NN seuclidean, Twoing, Deviance, K-NN euclidean, K-NN chebychev and Gdi;

- 7)

F1 for the left arm in a neutral stage (F1 range is [0.995; 0.998]): C-SVM, G-SVM, K-NN euclidean, K-NN cityblock, Twoing, K-NN seuclidean, Q-SVM, K-NN chebychev and K-NN minkowski;

- 8)

F1 for the right arm in a neutral stage (F1 range is [0.995; 0.998]): K-NN seuclidean, Q-SVM, G-SVM, C-SVM and Deviance.

Considering results of classification of Tasks A in a supination stage, we found following ML models that separated sEMG data with the highest performance for both limbs: a) four models (K-NN cityblock, K-NN cosine, K-NN minkowski, and K-NN seuclidean) that classified data with the highest performance (ACC = 100%, F1 = 1.000, PPV = 1.000, and SEN = 1.000); b) five models (Twoing, Deviance, Gdi, K-NN euclidean and K-NN chebychev) that classified data with ACC ≥ 99.658% along with F1 ≥ 0.997 for the left arm, and ACC ≥ 99.315% along with F1 ≥ 0.993 for the right arm. Furthermore, analyzing results of classification of Tasks A in a neutral stage, we found following ML models that separated sEMG data with the highest performance for both limbs: 1) K-NN seuclidean (for the left arm with ACC = 99.661% along with F1= 0.996; for the right arm with ACC = 99.757% along with F1=0.998) ; 2) G-SVM, and C-SVM (for the left arm with ACC=99.757% along with F1=0.998 ; for the right arm with ACC ≥ 99.635% along with F1≥0.996).

Analyzing all results of classification of tasks B (BSNLT, BSNRT, BSNLI, BSNRI), which used data merged from supination and neutral stages, we identified following ML models with the best performance that can be used:

- 1)

to identify a target position in neutral and supination stage for both limbs (BSNLT and BSNRT): K-NN seuclidean (for the right/left arm F1 equals 0.985/0.996), K-NN euclidean (for the right/left arm F1 equals 0.989/0.993) , K-NN minkowski (for the right/left arm F1 equals 0.986/0.992), K-NN cityblock (for the right/left arm F1 equals 0.986/0.992);

- 2)

to identify an initial position in neutral and supination stage for both limbs (BSNLI and BSNRI): K-NN cityblock (for the right/left arm F1 equals 0.966/0.973), K-NN seuclidean (for the right/left arm F1 equals 0.959/0.971), K-NN minkowski (for the right/left arm F1 equals 0.957/0.966);

- 3)

to identify an initial or target position in neutral along with supination stage for the left limb: K-NN cityblock (for initial/target position F1 equals 0.973/0.992), K-NN seuclidean (for initial/target position F1 equals 0.971/0.996), K-NN minkowski (for initial/target position F1 equals 0.966 /0.992), K-NN cosine (for initial/target position F1 equals 0.962/0.969);

- 4)

to identify an initial or target position in neutral along with supination stage for the right limb: K-NN euclidean (for initial/target position F1 equals 0.970 /0.989), K-NN cityblock (for initial/target position F1 equals 0.966 /0.986), K-NN seuclidean (for initial/target position F1 equals 0.959/0.985), K-NN minkowski (for initial/target position F1 equals 0.957/0.986).

Comparing our results with those reported in the literature, one should consider following factors that have a huge impact on results of classification: 1) tested motions along with influence of external loading; 2) tested muscles along with the type of EMG sensors used for EMG data acquisition, especially a frequency of sampling; 3) composition of sEMG patterns’ features; 4) algorithm of data processing; 5) type of classification (binary or multiclassification); 6) ML algorithm used for classification. In the

Table 3 we present the best results reported in literature.

We can see that our results are consistent with those presented in the literature, however, our results are related to binary classification and that is why comparison our results with published multiclassification results should be done with a caution. With respect to the K-NN models, three papers [

27,

43] and [

48] present high ACC results by using K-NN models to classify: a) forearm-hand activities based on sEMG data [

27]; b) hand motions based on sEMG features [

43]; c) types of neuromuscular disorder based on needle EMG data [

48]. On the other hand, high-performance results of classification obtained by applying SVM models based on sEMG data are described in [

6] (eight hand movements), [

47] (six categories of motion), [

49] (seven hand gestures). Also, the paper [

37] presents high-performance results of the classification of neuromuscular disorders by using the SVM-RF model and needle EMG data. Furthermore, one can find in the literature high-performance results of classification obtained by applying ANN models [

23,

50] or more complex neural network architectures: 1) the EMGHandNet model composed of CNN and Bi-LSTM architecture [

30]; 2) the HGS-SCNN model by using sEMG transformed to images ((1-D) CNN) [

51]; 3); the ResNet-50 model pre-trained (ImageNet) [

52]; 4) the BP (back-propagation)—LSTM model [

33]. Moreover, there are studies that report results of classification of upper limb motions by presenting results of application of different ML algorithms that were tested in our study, e.g., a study [

23] describes that proposed classification models allowed the authors to obtain accuracy equaled 95.02% (LDA), 94.63% (SVM), 90.05% (kNN), and 86.66% (DT).

Considering findings presented in this study, one can conclude that different ML models should be used to classify muscle activity in supination stage and in neutral stage. This conclusion bears out the fact that tested muscles are activated in a different way in tested stages, since musculoskeletal configurations of the upper limb segments (arm, forearm, and hand) are different in supination and neutral forearm configuration with respect to the gravity field. Moreover, the muscular system is a redundant one, and muscles work in groups according to habituated neurological and motor patterns. That is why different configurations of the skeletal system require different patterns. Furthermore, these patterns are dependent on subject anthropometric proportions that are influenced by biomechanical characteristics, limb dominance, and the degree of familiarity with motions tested in this study (i.e., agility acquired due to previous physical activities like sport, playing music instruments, or dance). Moreover, a study [

30] declared that results of classification of subject wise data are higher with respect to the aggregate data. All these factors should be considered as a reason of inter and intra differences in tested muscle activity.

From the practice point of view, the best ML models identified in this study can be applied to help clinicians to identify activity states of tested muscles, for example, in a rehabilitation of neuromuscular disorders, ergonomics, or military, especially by applying an external passive or active device [

53].

Limitations of this study are as follows. First, in this study we did not use multiclassification models nor more complex models composed of a few ML classifiers or Deep Learning models. Second, this paper does not cover results of pronation forearm configuration.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this preliminary study was to recognize motion patterns by classifying time series features obtained from processed EMG data. To reach this goal we identified ML methods of supervised classification that could be used to recognize the states of tested muscles based on surface EMG data. In this study we only focused on two stages of the forearm (supination and neutral) related to initial and target positions and we tested six main ML classifiers: Decision Trees (Gdi, Twoing, Deviance), Support Vector Machines (L-SVM, Q-SVM, C-SVM and G -SVM), Linear Discriminant (LD), Quadratic Discriminant (QD), K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN euclidean, K-NN city block, K-NN, K-NN cosine, K-NN correlation, K-NN minkowski, K-NN seuclidean, K-NN spearman, K-NN jaccard), Efficient Logistic Regressions (ELR asgd, ELR sgd, ELR bfgs, ELR lbfgs, ELR sparsa). It is worth emphasizing that to the authors’ knowledge the results presented in this study are new ones with respect to the tested motions and tested muscles along with the feature compositions used for classification.

In this study we present solutions of binary classification tasks that are aimed to divide sEMG data for four datasets. Analyzing all results of classifications of tasks A, we identified the following high-performance ML models that can be used to split the sEMG data to identify a target or initial position for both limbs:

- 1)

in supination stage—six K-Nearest Neighbors’ models (K-NN cityblock, K-NN cosine, K-NN minkowski, and K-NN seuclidean, K-NN euclidean and K-NN chebychev) and three Decision Trees models (Twoing, Deviance, Gdi);

- 2)

in neutral stage—one K-Nearest Neighbors’ models (K-NN seuclidean) and two SVM models (G-SVM and C-SVM).

Analyzing results of classifications of tasks B, we found that:

- 1)

for both limbs four K-Nearest Neighbors’ models (K-NN seuclidean, K-NN euclidean, K-NN minkowski , K-NN cityblock ) can be applied to split the sEMG data into neutral or supination stage in target position;

- 2)

for both limbs three K-Nearest Neighbors’ models (K-NN cityblock, K-NN seuclidean, K-NN minkowski ) can be applied to split the sEMG data into neutral or supination stage in initial position;

- 3)

for the left limb four K-Nearest Neighbors’ models (K-NN cityblock, K-NN seuclidean, K-NN minkowski, K-NN cosine) can be used to divide sEMG data related to initial or target position in neutral or supination stage;

- 4)

for the right limb four K-Nearest Neighbors’ models (K-NN euclidean , K-NN cityblock, K-NN seuclidean, K-NN minkowski) can be used to divide sEMG data related to initial or target position in neutral or supination stage.

Moreover, analyzing all results of tasks solved in this study, we found that to classify data with the highest performance one can apply:

- 1)

K-NN seuclidean model in all A tasks;

- 2)

K-NN cityblock or K-NN seuclidean, or K-NN minkowski models in all tasks B.

In this study, a pattern classification was performed by considering features composed of four EMG patterns recorded on each upper limb. Each EMG pattern was a time series of postprocessed sEMG data. An application of such features has clinical and biomechanical reasons, because muscles function in groups. Moreover, one should keep in mind that sEMG data are irregular, complex physiological signals reflecting muscle activation that is a time-spatial summation of motor units. That is why postprocessing of these data should be performed in a proper way along with data denoising.

It is worth noting that we cannot point out the only one model of classification, which is able to split sEMG data with the highest results of ACC and/or F1 metrics for both arms in supination and neutral stages to recognize the tested positions (target or initial). We would suggest to use different ML models to accurately identify the muscle activity of the left and right upper limbs. Applying ML classification models, one can discriminate and/or classify EMG data (or to recognize EMG patterns) to diagnose different musculoskeletal disorders (e.g., Duchenne muscular disorder, stroke or due to aging), to assess the progress of disorder due to applied treatment or rehabilitation strategy, especially in evaluating a progress of functional recovery in applied rehabilitation or somatosensory rehabilitation program, to control a functioning of wearable robotics devices or external prosthetic devices or other external devices (e.g., an exoskeleton) through setting the proper mode of function (assistance or guidance mode). Additionally, tested ML algorithms could be applied to control human-robot interactions in industrial digital production or digital twins. Moreover, it is worth paying attention that the classification toolboxes that were used in this study are working in a very fast way. This issue is critical in real-time control system.

Future research encompasses: 1) an elaboration of external sEMG dataset of a healthy population; 2) classification of results in pronation forearm configuration and more complex motions used in activities of daily living); 3) testing of more complex models composed of ensemble of ML classifiers and/or Deep Learning models to clarify whether these complex models are more effective ones with respect to the models used in this study

Supplementary Materials

The supplement file contains additional table and figures referenced in the manuscript (Supplementary Materials): Table S.I. Classification learner methods and hyperparameters used in this study; Figure S1. Results of the classification of the Models ASL; Figure S2. Results of classification of Models ASR; Figure S3. Results of classification of Models ANL; Figure S4. Results of classification of Models ANR; Figure S5.1. Results of classification of Models BSNLI; Figure S5.2. Results of classification of Models BSNLT; Figure S6.1. Results of classification of Models BSNRI; Figure S6.2. Results of classification of Models BSNRT; Figure S7.4. Chosen confusion matrices of classification results of the BSNRT task.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—KP & WW; Data curation—WW & KP; Formal analysis—WW; Funding acquisition—MC; Investigation—KP & WW; Methodology—KP & WW; Resources—KP & WW; Software—WW & KP; Supervision—NS; Validation—NS; Visualization—KP; Writing original draft—KP & NS & WW & MC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee (Ethics Committee Approval of Gdansk University of Technology from January 29, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The calculations were carried out at the Academic Computer Centre in Gdansk (TASK), Poland.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rahman, S.; Ali, M.; Mamun, M. The use of wearable sensors for the classification of electromyographic signal patterns based on changes in the elbow joint angle. Procedia Computer Science 2021, 185, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayan, A.; Premjith, B. EMG physical action detection using recurrence plot approach. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 235, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Xu, M.; Shen, T.; Chen, J.; Jiang, G.; Xiao, J.; Chen, X. A channel-fused gated temporal convolutional network for EMG-based gesture recognition. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2024, 95, 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzi, N.; Malandri, L.; Mercorio, F.; Pedrocchi, A. XAI for myo-controlled prosthesis: explaining EMG data for hand gesture classification. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 240, 108053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmadeev, K.; Rampone, E.; Yu, T.; Aoustin, Y.; Carpentier, É. A testing system for a real-time gesture classification using surface EMG. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 11498–11503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barfi, M.; Karami, H.; Faridi, F.; Sohrabi, Z.; Hosseini, M. Improving robotic hand control via adaptive fuzzy-PI controller using classification of EMG signals. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocejko, T.; Rumiński, J.; Przystup, P.; Poliński, A.; Wtorek, J. The role of EMG module in hybrid interface of prosthetic arm. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th International Conference on Human System Interactions (HSI); 2017; pp. 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente-Vidrio, D.; Lázaro, R.; Ballesteros, M.; Salgado, I.; Cruz-Ortiz, D.; Chaírez, I. Event driven sliding mode control of a lower limb exoskeleton based on a continuous neural network electromyographic signal classifier. Mechatronics 2020, 72, 102451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triwiyanto, T.; Pawana, I.; Caesarendra, W. Deep learning approach to improve the recognition of hand gesture with multi force variation using electromyography signal from amputees. Medical Engineering & Physics 2024, 125, 104131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Hu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhou, M.; Song, Y. Towards integration of domain knowledge-guided feature engineering and deep feature learning in surface electromyography-based hand movement recognition. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2021, 2021, 4454648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, S.; Tonin, L.; Chisari, C.; Micera, S.; Menegatti, E.; Artoni, F. Hybrid human–machine interface for gait decoding through Bayesian fusion of EEG and EMG classifiers. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2020, 14, 582728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triwiyanto, T.; Rahmawati, T.; Pawana, I. Feature and muscle selection for an effective hand motion classifier based on electromyography. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Informatics (IJEEI) 2019, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betthauser, J.; Hunt, C.; Osborn, L.; Masters, M.; Lévay, G.; Kaliki, R. Limb position tolerant pattern recognition for myoelectric prosthesis control with adaptive sparse representations from extreme learning. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2018, 65, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, A. Machine learning-based novel approach to classify the shoulder motion of upper limb amputees. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2019, 39, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, J.; Flanagan, W.; Csomay-Shanklin, N.; Kanwar, B.; Young, A. A machine learning strategy for locomotion classification and parameter estimation using fusion of wearable sensors. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2021, 68, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Hargrove, L.; Lock, B.; Kuiken, T. A decision-based velocity ramp for minimizing the effect of misclassifications during real-time pattern recognition control. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2011, 58, 2360–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Hargrove, L.; Kuiken, T. The effects of electrode size and orientation on the sensitivity of myoelectric pattern recognition systems to electrode shift. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2011, 58, 2537–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [18] Young, A.; Hargrove, L.; Kuiken, T. Improving myoelectric pattern recognition robustness to electrode shift by changing interelectrode distance and electrode configuration. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2012, 59, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlot, N.; Jena, A.; Vijayvargiya, A.; Kumar, R. Surface electromyography based explainable artificial intelligence fusion framework for feature selection of hand gesture recognition. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2024, 137, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gutierrez-Farewik, E. Joint kinematics, kinetics and muscle synergy patterns during transitions between locomotion modes. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2023, 70, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yu, Y.; Sheng, X.; Meng, J.; Zhu, X. Real-time hand gesture recognition by decoding motor unit discharges across multiple motor tasks from surface electromyography. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2023, 70, 2058–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Park, S.; Kim, K. sEMG-based gesture recognition using temporal history. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2023, 70, 2655–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajapriya, R.; Rajeswari, K. ; T. S.J. Deep learning and machine learning techniques to improve hand movement classification in myoelectric control system. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2021, 41, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, B.; Singh, P.; Singhal, A.; Pachori, R. Hand movement recognition from sEMG signals using Fourier decomposition method. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2021, 41, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, R.; Dwivedi, A.; Guan, B.; Turner, A.; Shieff, D.; Liarokapis, M. On EMG based dexterous robotic telemanipulation: assessing machine learning techniques, feature extraction methods, and shared control schemes. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 99661–99674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.; Cheng, M.; Alshahrani, Y.; Franovic, S.; Lau, E.; Xu, G.; Ni, G.; Cavanaugh, J.; Muh, S.; Lemos, S. Comparison of machine learning methods in sEMG signal processing for shoulder motion recognition. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 68, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boka, T.; Eskandari, A.; Moosavian, S.; Sharbatdar, M. Using machine learning algorithms for grasp strength recognition in rehabilitation planning. Results in Engineering 2024, 21, 101660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersin, Ç.; Yaz, M. Comparison of KNN and random forest algorithms in classifying EMG signals. European Journal of Science and Technology 2023, 51, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wong, Y.; Wei, W.; Du, Y.; Kankanhalli, M.; Geng, W. A novel attention-based hybrid CNN–RNN architecture for sEMG-based gesture recognition. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0206049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnam, N.; Dubey, S.; Turlapaty, A.; Gokaraju, B. EMGHandNet: a hybrid CNN and BI-LSTM architecture for hand activity classification using surface EMG signals. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2022, 42, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryon, J.; Trejos, A. Evaluating convolutional neural networks as a method of EEG–EMG fusion. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2021, 15, 692183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fu, J.; Chen, H.; Zheng, B. Hand gesture recognition using smooth wavelet packet transformation and hybrid CNN based on surface EMG and accelerometer signal. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 86, 105141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Dey, N.; Fong, S.; Ashour, A. Deep back propagation–long short-term memory network based upper-limb sEMG signal classification for automated rehabilitation. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2020, 40, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Smith, L.; Rouse, E.; Hargrove, L. Classification of simultaneous movements using surface EMG pattern recognition. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2013, 60, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudet, G.; Raison, M.; Achiche, S. Classification of upper limb phantom movements in transhumeral amputees using electromyographic and kinematic features. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2018, 68, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaram, N.; Karthick, P.; Swaminathan, R. Analysis of dynamics of EMG signal variations in fatiguing contractions of muscles using transition network approach. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subaşı, A. Diagnosis of neuromuscular disorders using DT-CWT and rotation forest ensemble classifier. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2020, 69, 1940–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, X.; Sun, A.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. A novel event-driven spiking convolutional neural network for electromyography pattern recognition. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2023, 70, 2604–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Agarwal, R. Single channel EMG-based continuous terrain identification with simple classifier for lower limb prosthesis. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2019, 39, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raurale, S.; McAllister, J.; Rincón, J. Real-time embedded EMG signal analysis for wrist–hand pose identification. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2020, 68, 2713–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Cárdenas, S.; Castillo-Castañeda, E.; Lozano-Guzmán, A.; Zequera, M.; Gallegos-Torres, R.; Ramirez-Bautista, J. Characterization of muscle fatigue in the lower limb by sEMG and angular position using the WFD protocol. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2021, 41, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzke, A.; Kristoffersen, M.; Jayaram, V.; Sluis, C.; Murgia, A.; Bongers, R. Exploring the relationship between EMG feature space characteristics and control performance in machine learning myoelectric control. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2021, 29, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Lyu, Z.; Tang, S.; Chia, T.; Yang, C. A bionic hand controlled by hand gesture recognition based on surface EMG signals: a preliminary study. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2018, 38, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, M.; Merletti, R.; Rainoldi, A. Atlas of Muscle Innervation Zones: Understanding Surface Electromyography and Its Applications; Springer: Milan, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barański, R.; Wojnicz, W.; Zagrodny, B.; Ludwicki, M.; Sobierajska-Rek, A. Towards hand grip force assessment by using EMG estimators. Measurement 2024, 226, 114137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharwat, A. Classification assessment methods. Applied Computing and Informatics 2020, 17, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnam, N.; Turlapaty, A.; Dubey, S.; Gokaraju, B. EMAHA-DB1: a new upper limb sEMG dataset for classification of activities of daily living. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Castillo, J.; López-López, C.; Castañeda, M. Neuromuscular disorders detection through time–frequency analysis and classification of multi-muscular EMG signals using Hilbert–Huang transform. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 71, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepe, C.; Demir, M. Real-time classification of EMG Myo armband data using support vector machine. IRBM 2022, 43, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubers, D.; Potters, W.; Paalvast, O.; Doelkahar, B.; Tannemaat, M.; Wieske, L.; Verhamme, C. . Artificial intelligence-based classification of motor unit action potentials in real-world needle EMG recordings. Clinical Neurophysiology 2023, 156, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.; Langås, E.; Sanfilippo, F. Empowering human–robot interaction using sEMG sensor: hybrid deep learning model for accurate hand gesture recognition. Results in Engineering 2023, 20, 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, M.; Kisa, D.; Güren, O.; Akan, A. Hand gesture classification using time–frequency images and transfer learning based on CNN. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 77, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnicz, W.; Sobierajska-Rek, A.; Zagrodny, B.; Ludwicki, M.; Jabłońska-Brudło, J.; Forysiak, K. A new approach to assess quality of motion in functional task of upper limb in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 12247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Configuration of the body of the tested subject: A) initial position in a supination stage; B) target position in a supination stage; C) initial position in a neutral stage; D) target position in a neutral stage.

Figure 1.

Configuration of the body of the tested subject: A) initial position in a supination stage; B) target position in a supination stage; C) initial position in a neutral stage; D) target position in a neutral stage.

Figure 2.

Visualization of location of Trigno Avanti™ sensors along with visualization of axes of accelerometer.

Figure 2.

Visualization of location of Trigno Avanti™ sensors along with visualization of axes of accelerometer.

Figure 3.

A. Raw and processed data recorded over relax and isometric stages (subject nr 8, sensor nr 4, supination stage): raw EMG and rms EMG (upper picture), accelerometer data (lower picture).

Figure 3.

A. Raw and processed data recorded over relax and isometric stages (subject nr 8, sensor nr 4, supination stage): raw EMG and rms EMG (upper picture), accelerometer data (lower picture).

Figure 3.

B. Visualizations of a feature described a target position in a supination stage.

Figure 3.

B. Visualizations of a feature described a target position in a supination stage.

Figure 3.

C. Visualizations of a feature described an initial position in a supination stage.

Figure 3.

C. Visualizations of a feature described an initial position in a supination stage.

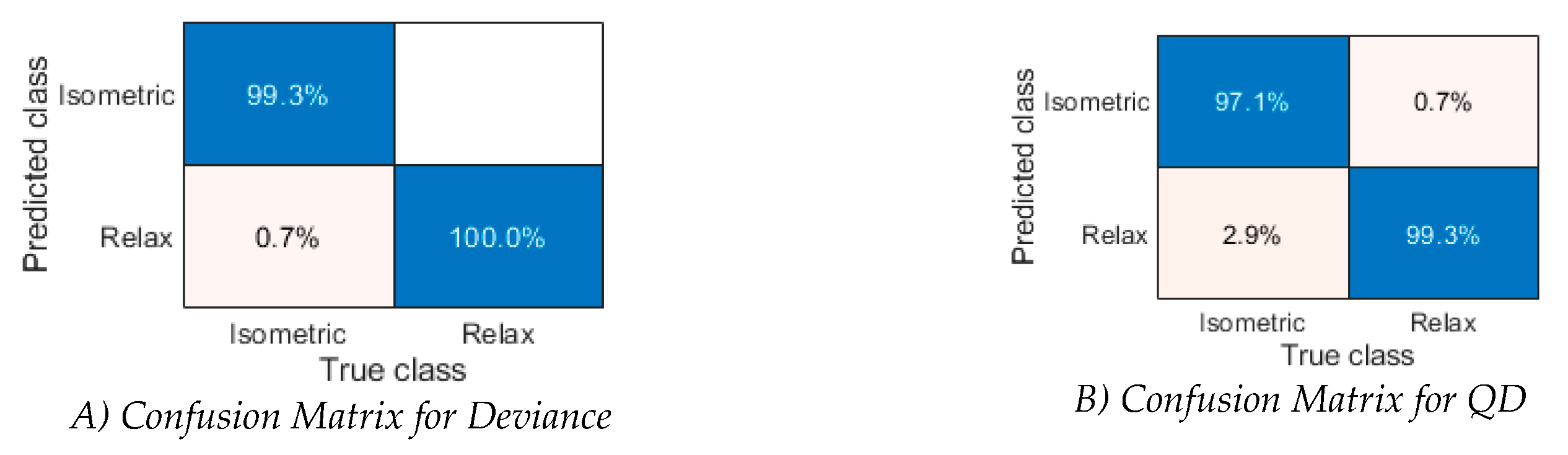

Figure 4.

A. Results of the classification of ASL task.

Figure 4.

A. Results of the classification of ASL task.

Figure 4.

B. Chosen confusion matrixes of classification results of ASL task.

Figure 4.

B. Chosen confusion matrixes of classification results of ASL task.

Figure 5.

A. Results of the classification of the ASR task.

Figure 5.

A. Results of the classification of the ASR task.

Figure 5.

B. Chosen confusion matrices of classification results of ASR task.

Figure 5.

B. Chosen confusion matrices of classification results of ASR task.

Figure 6.

A. Results classification of ANL task.

Figure 6.

A. Results classification of ANL task.

Figure 6.

B. Chosen confusion matrixes of classification results of ANL task.

Figure 6.

B. Chosen confusion matrixes of classification results of ANL task.

Figure 7.

A. Results of classification of ANR task.

Figure 7.

A. Results of classification of ANR task.

Figure 7.

B. Chosen confusion matrices of classification results of ANR task.

Figure 7.

B. Chosen confusion matrices of classification results of ANR task.

Table 1.

A. Results of classification of the left arm in a supination stage (ASL task).

Table 1.

A. Results of classification of the left arm in a supination stage (ASL task).

| No |

Classifier |

ACC

[%] |

PPV

[-] |

SEN

[-] |

F1

[-] |

| 1. |

Gdi |

99.658 |

1.000 |

0.993 |

0.997 |

| 2. |

Twoing |

99.772 |

0.995 |

1.000 |

0.998 |

| 3. |

Deviance |

99.772 |

1.000 |

0.995 |

0.998 |

| 4. |

L-SVM |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 5. |

Q-SVM |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 6. |

C-SVM |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 7. |

G-SVM |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 8. |

LD |

95.662 |

0.997 |

0.916 |

0.955 |

| 9. |

QD |

98.744 |

0.976 |

1.000 |

0.988 |

| 10. |

K-NN euclidean |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 11. |

K-NN cityblock |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 12. |

K-NN chebychev |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 13. |

K-NN cosine |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 14. |

K-NN correlation |

98.174 |

0.995 |

0.968 |

0.981 |

| 15. |

K-NN minkowski |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 16. |

K-NN seuclidean |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 17. |

K-NN spearman |

98.174 |

1.000 |

0.963 |

0.981 |

| 18. |

K-NN jaccard |

89.840 |

0.832 |

1.000 |

0.908 |

| 19. |

ELR asgd |

97.717 |

0.995 |

0.959 |

0.977 |

| 20. |

ELR sgd |

97.717 |

1.000 |

0.954 |

0.977 |

| 21. |

ELR bfgs |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 22. |

ELR lbfgs |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 23. |

ELR sparsa |

99.543 |

1.000 |

0.991 |

0.995 |

Table 1.

B. Results of classification of the right arm in a supination stage (ASR task).

Table 1.

B. Results of classification of the right arm in a supination stage (ASR task).

| No |

Classifier |

ACC [%] |

PPV

[-] |

SEN

[-] |

F1

[-] |

| 1. |

Gdi |

99.315 |

0.993 |

0.993 |

0.993 |

| 2. |

Twoing |

99.886 |

1.000 |

0.998 |

0.999 |

| 3. |

Deviance |

99.886 |

0.998 |

1.000 |

0.999 |

| 4. |

L-SVM |

97.717 |

0.997 |

0.957 |

0.977 |

| 5. |

Q-SVM |

98.288 |

1.000 |

0.966 |

0.983 |

| 6. |

C-SVM |

98.288 |

1.000 |

0.966 |

0.983 |

| 7. |

G-SVM |

98.288 |

1.000 |

0.966 |

0.983 |

| 8. |

LD |

95.206 |

0.993 |

0.911 |

0.950 |

| 9. |

QD |

96.233 |

0.972 |

0.952 |

0.962 |

| 10. |

K-NN euclidean |

99.658 |

1.000 |

0.993 |

0.997 |

| 11. |

K-NN cityblock |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 12. |

K-NN chebychev |

99.658 |

1.000 |

0.993 |

0.997 |

| 13. |

K-NN cosine |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 14. |

K-NN correlation |

96.918 |

1.000 |

0.938 |

0.968 |

| 15. |

K-NN minkowski |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 16. |

K-NN seuclidean |

100.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

| 17. |

K-NN spearman |

97.603 |

1.000 |

0.952 |

0.975 |

| 18. |

K-NN jaccard |

90.753 |

1.000 |

0.815 |

0.898 |

| 19. |

ELR asgd |

96.233 |

1.000 |

0.925 |

0.961 |

| 20. |

ELR sgd |

96.233 |

1.000 |

0.925 |

0.961 |

| 21. |

ELR bfgs |

98.288 |

0.993 |

0.973 |

0.983 |

| 22. |

ELR lbfgs |

97.945 |

0.986 |

0.973 |

0.979 |

| 23. |

ELR sparsa |

98.630 |

1.000 |

0.973 |

0.986 |

Table 1.

C. Results of classification of the left arm in a neutral stage (ANL task).

Table 1.

C. Results of classification of the left arm in a neutral stage (ANL task).

| No |

Classifier |

ACC [%] |

PPV [-] |

SEN

[-] |

F1 [-] |

| 1. |

Twoing |

99.635 |

0.998 |

0.995 |

0.996 |

| 2. |

Deviance |

99.392 |

0.993 |

0.995 |

0.994 |

| 3. |

Q-SVM |

99.513 |

0.995 |

0.995 |

0.995 |

| 4. |

C-SVM |

99.757 |

0.995 |

1.000 |

0.998 |

| 5. |

G-SVM |

99.757 |

0.995 |

1.000 |

0.998 |

| 6. |

QD |

97.445 |

0.992 |

0.956 |

0.974 |

| 7. |

K-NN euclidean |

99.765 |

0.999 |

0.996 |

0.998 |

| 8. |

K-NN cityblock |

99.713 |

0.996 |

0.998 |

0.997 |

| 9. |

K-NN chebychev |

99.505 |

0.995 |

0.995 |

0.995 |

| 10. |

K-NN cosine |

99.140 |

0.997 |

0.985 |

0.991 |

| 11. |

K-NN minkowski |

99.530 |

0.992 |

0.998 |

0.995 |

| 12. |

K-NN seuclidean |

99.661 |

0.995 |

0.998 |

0.996 |

| 13. |

ELR bfgs |

98.297 |

0.990 |

0.976 |

0.983 |

| 14. |

ELR lbfgs |

98.054 |

0.990 |

0.971 |

0.980 |

| 15. |

ELR sparsa |

97.445 |

0.990 |

0.959 |

0.974 |

Table 1.

D. Results of classification of the right arm in a neutral stage (ANR task).

Table 1.

D. Results of classification of the right arm in a neutral stage (ANR task).

| No |

Classifier |

ACC [%] |

PPV

[-] |

SEN

[-] |

F1

[-] |

| 1. |

Twoing |

99.270 |

0.998 |

0.988 |

0.993 |

| 2. |

Deviance |

99.513 |

1.000 |

0.990 |

0.995 |

| 3. |

Q-SVM |

99.726 |

1.000 |

0.995 |

0.997 |

| 4. |

C-SVM |

99.635 |

0.998 |

0.995 |

0.996 |

| 5. |

G-SVM |

99.726 |

1 .000 |

0.995 |

0.997 |

| 6. |

QD |

97.810 |

0.990 |

0.966 |

0.978 |

| 7. |

K-NN euclidean |

99.392 |

0.990 |

0.998 |

0.994 |

| 8. |

K-NN cityblock |

99.392 |

0.990 |

0.998 |

0.994 |

| 9. |

K-NN chebychev |

99.148 |

1.000 |

0.983 |

0.991 |

| 10. |

K-NN cosine |

99.392 |

0.993 |

0.995 |

0.994 |

| 11. |

K-NN minkowski |

99.392 |

0.993 |

0.995 |

0.994 |

| 12. |

K-NN seuclidean |

99.757 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

| 13. |

ELR bfgs |

97.689 |

0.976 |

0.978 |

0.977 |

| 14. |

ELR lbfgs |

97.323 |

0.978 |

0.968 |

0.973 |

| 15. |

ELR sparsa |

96.959 |

0.978 |

0.961 |

0.969 |

Table 2.

A. Results of classification of supination and neutral stages of the left arm in an initial position (BSNLI task).

Table 2.

A. Results of classification of supination and neutral stages of the left arm in an initial position (BSNLI task).

| No. |

Method |

PPV [-] |

SEN [-] |

F1 [-] |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| 1. |

Twoing |

0.922 |

0.018 |

0.935 |

0.018 |

0.928 |

0.011 |

| 2. |

Deviance |

0.927 |

0.021 |

0.924 |

0.020 |

0.925 |

0.015 |

| 3. |

Q-SVM |

0.807 |

0.019 |

0.818 |

0.031 |

0.812 |

0.021 |

| 4. |

C-SVM |

0.916 |

0.020 |

0.927 |

0.019 |

0.921 |

0.014 |

| 5. |

G-SVM |

0.896 |

0.018 |

0.813 |

0.027 |

0.852 |

0.017 |

| 6. |

QD |

0.549 |

0.057 |

0.210 |

0.033 |

0.304 |

0.041 |

| 7. |

K-NN euclidean |

0.963 |

0.013 |

0.957 |

0.015 |

0.960 |

0.008 |

| 8. |

K-NN cityblock |

0.961 |

0.011 |

0.985 |

0.009 |

0.973 |

0.007 |

| 9. |

K-NN chebychev |

0.956 |

0.017 |

0.953 |

0.018 |

0.954 |

0.014 |

| 10. |

K-NN cosine |

0.961 |

0.014 |

0.963 |

0.015 |

0.962 |

0.009 |

| 11. |

K-NN minkowski |

0.958 |

0.015 |

0.974 |

0.014 |

0.966 |

0.009 |

| 12. |

K-NN seuclidean |

0.965 |

0.013 |

0.977 |

0.014 |

0.971 |

0.009 |

| 13. |

ELR bfgs |

0.622 |

0.038 |

0.493 |

0.037 |

0.549 |

0.034 |

| 14. |

ELR lbfgs |

0.615 |

0.035 |

0.470 |

0.044 |

0.532 |

0.038 |

| 15. |

ELR sparsa |

0.607 |

0.051 |

0.334 |

0.036 |

0.430 |

0.039 |

Table 2.

B. Results of classification of supination and neutral stages of the left arm in a target position (BSNLT task).

Table 2.

B. Results of classification of supination and neutral stages of the left arm in a target position (BSNLT task).

| No |

Method |

PPV [-] |

SEN [-] |

F1 [-] |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| 1. |

Twoing |

0.951 |

0.015 |

0.935 |

0.02 |

0.943 |

0.013 |

| 2. |

Deviance |

0.959 |

0.013 |

0.958 |

0.016 |

0.958 |

0.01 |

| 3. |

Q-SVM |

0.905 |

0.021 |

0.823 |

0.024 |

0.862 |

0.016 |

| 4. |

C-SVM |

0.970 |

0.014 |

0.919 |

0.024 |

0.944 |

0.015 |

| 5. |

G-SVM |

0.966 |

0.014 |

0.897 |

0.023 |

0.930 |

0.013 |

| 6. |

QD |

0.821 |

0.039 |

0.508 |

0.036 |

0.627 |

0.03 |

| 7. |

K-NN euclidean |

0.996 |

0.004 |

0.990 |

0.006 |

0.993 |

0.004 |

| 8. |

K-NN cityblock |

0.998 |

0.003 |

0.986 |

0.008 |

0.992 |

0.004 |

| 9. |

K-NN chebychev |

0.973 |

0.013 |

0.960 |

0.016 |

0.966 |

0.011 |

| 10. |

K-NN cosine |

0.970 |

0.014 |

0.969 |

0.012 |

0.969 |

0.011 |

| 11. |

K-NN minkowski |

0.992 |

0.005 |

0.992 |

0.006 |

0.992 |

0.004 |

| 12. |

K-NN seuclidean |

0.994 |

0.006 |

0.997 |

0.005 |

0.996 |

0.005 |

| 13. |

ELR bfgs |

0.803 |

0.024 |

0.761 |

0.031 |

0.781 |

0.022 |

| 14. |

ELR lbfgs |

0.816 |

0.026 |

0.756 |

0.029 |

0.785 |

0.022 |

| 15. |

ELR sparsa |

0.793 |

0.028 |

0.744 |

0.035 |

0.767 |

0.027 |

Table 2.

C. Results of classification of supination and neutral stages of the right arm in an initial position (BSNRI task).

Table 2.

C. Results of classification of supination and neutral stages of the right arm in an initial position (BSNRI task).

| No |

Method |

PPV [-] |

SEN [-] |

F1 [-] |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| 1. |

Twoing |

0.924 |

0.015 |

0.919 |

0.022 |

0.921 |

0.013 |

| 2. |

Deviance |

0.934 |

0.015 |

0.931 |

0.016 |

0.932 |

0.013 |

| 3. |

Q-SVM |

0.801 |

0.028 |

0.811 |

0.027 |

0.806 |

0.023 |

| 4. |

C-SVM |

0.917 |

0.020 |

0.941 |

0.016 |

0.928 |

0.014 |

| 5. |

G-SVM |

0.887 |

0.017 |

0.906 |

0.024 |

0.897 |

0.018 |

| 6. |

QD |

0.548 |

0.060 |

0.199 |

0.031 |

0.291 |

0.040 |

| 7. |

K-NN euclidean |

0.967 |

0.015 |

0.973 |

0.012 |

0.970 |

0.009 |

| 8. |

K-NN cityblock |

0.964 |

0.015 |

0.968 |

0.012 |

0.966 |

0.008 |

| 9. |

K-NN chebychev |

0.940 |

0.015 |

0.933 |

0.019 |

0.936 |

0.011 |

| 10. |

K-NN cosine |

0.936 |

0.017 |

0.950 |

0.015 |

0.943 |

0.012 |

| 11. |

K-NN minkowski |

0.957 |

0.011 |

0.956 |

0.013 |

0.957 |

0.010 |

| 12. |

K-NN seuclidean |

0.946 |

0.013 |

0.972 |

0.011 |

0.959 |

0.007 |

| 13. |

ELR bfgs |

0.563 |

0.038 |

0.313 |

0.034 |

0.402 |

0.035 |

| 14. |

ELR lbfgs |

0.608 |

0.047 |

0.350 |

0.029 |

0.444 |

0.033 |

| 15. |

ELR sparsa |

0.574 |

0.057 |

0.219 |

0.031 |

0.316 |

0.037 |

Table 2.

D. Results of classification of supination and neutral stages of the right arm in a target position (BSNRT task).

Table 2.

D. Results of classification of supination and neutral stages of the right arm in a target position (BSNRT task).

| No |

Method |

PPV [-] |

SEN [-] |

F1 [-] |

| Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| 1. |

Twoing |

0.944 |

0.017 |

0.923 |

0.021 |

0.933 |

0.015 |

| 2. |

Deviance |

0.932 |

0.020 |

0.936 |

0.018 |

0.934 |

0.015 |

| 3. |

Q-SVM |

0.861 |

0.019 |

0.906 |

0.027 |

0.882 |

0.017 |

| 4. |

C-SVM |

0.939 |

0.019 |

0.947 |

0.017 |

0.943 |

0.014 |

| 5. |

G-SVM |

0.972 |

0.014 |

0.939 |

0.016 |

0.955 |

0.011 |

| 6. |

QD |

0.667 |

0.023 |

0.730 |

0.030 |

0.697 |

0.023 |

| 7. |

K-NN euclidean |

0.991 |

0.006 |

0.986 |

0.010 |

0.989 |

0.006 |

| 8. |

K-NN cityblock |

0.995 |

0.005 |

0.977 |

0.011 |

0.986 |

0.006 |

| 9. |

K-NN chebychev |

0.966 |

0.013 |

0.964 |

0.014 |

0.965 |

0.008 |

| 10. |

K-NN cosine |

0.969 |

0.015 |

0.977 |

0.016 |

0.973 |

0.012 |

| 11. |

K-NN minkowski |

0.990 |

0.008 |

0.982 |

0.010 |

0.986 |

0.007 |

| 12. |

K-NN seuclidean |

0.988 |

0.007 |

0.982 |

0.009 |

0.985 |

0.006 |

| 13. |

ELR bfgs |

0.723 |

0.029 |

0.758 |

0.029 |

0.740 |

0.024 |

| 14. |

ELR lbfgs |

0.718 |

0.020 |

0.759 |

0.027 |

0.737 |

0.016 |

| 15. |

ELR sparsa |

0.715 |

0.028 |

0.731 |

0.040 |

0.723 |

0.031 |

Table 3.

Results of classification reported in the literature.

Table 3.

Results of classification reported in the literature.

| Article |

Algorithm/ type of classification |

ACC [%] |

PPV [%] |

SEN [%] |

F1 [%] |

| [6] |

SVM RBF/ multi |

90.69 |

- |

62.10 |

- |

| [27] |

K-NN / multi |

99.23 |

98.47 |

98.45 |

98.46 |

| [30] |

CNN and Bi-LSTM / multi |

98.33 |

- |

- |

|

| [33] |

BP-LSTM / multi |

92.00 |

91.00 |

- |

96.00 |

| [37] |

RF + SVM / binary |

99.70 |

- |

- |

99.70 |

| [43] |

K-NN / multi |

94.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| [47] |

SVM /multi |

83.21 |

- |

- |

- |

| [48] |

K-NN / multi |

99.50 |

- |

99.60 & 98.80 |

- |

| [49] |

SVM Cubic / multi |

95.83 |

96.09 |

- |

95.86 |

| [51] |

HGS-SCNN/ multi |

99.44 |

- |

- |

99.44 |

| [52] |

ResNet-50 / multi |

94.41 |

- |

- |

95.96 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).