1. Introduction

Over the last decade, the wearable healthcare technologies are evolving from the simple activity trackers into the more multifunctional platforms that are capable for continuous physiological and even biochemical monitoring. The combination of the microelectronics, flexible materials, and also the wireless communication has turned the wearables into quite a powerful tool for the real-time health management and for a more personalized medicine [

1]. The modern devices are including the sensors that can track the parameters like temperature, motion, heart rhythm, or even the sweat composition, which is making possible the preventive diagnostics and a more decentralized care [

2]. Altogether, this shift is showing the clear move from the hospital-based monitoring toward a more autonomous and patient-focused systems that can be able to handle both the data collection and the closed-loop therapeutic actions.

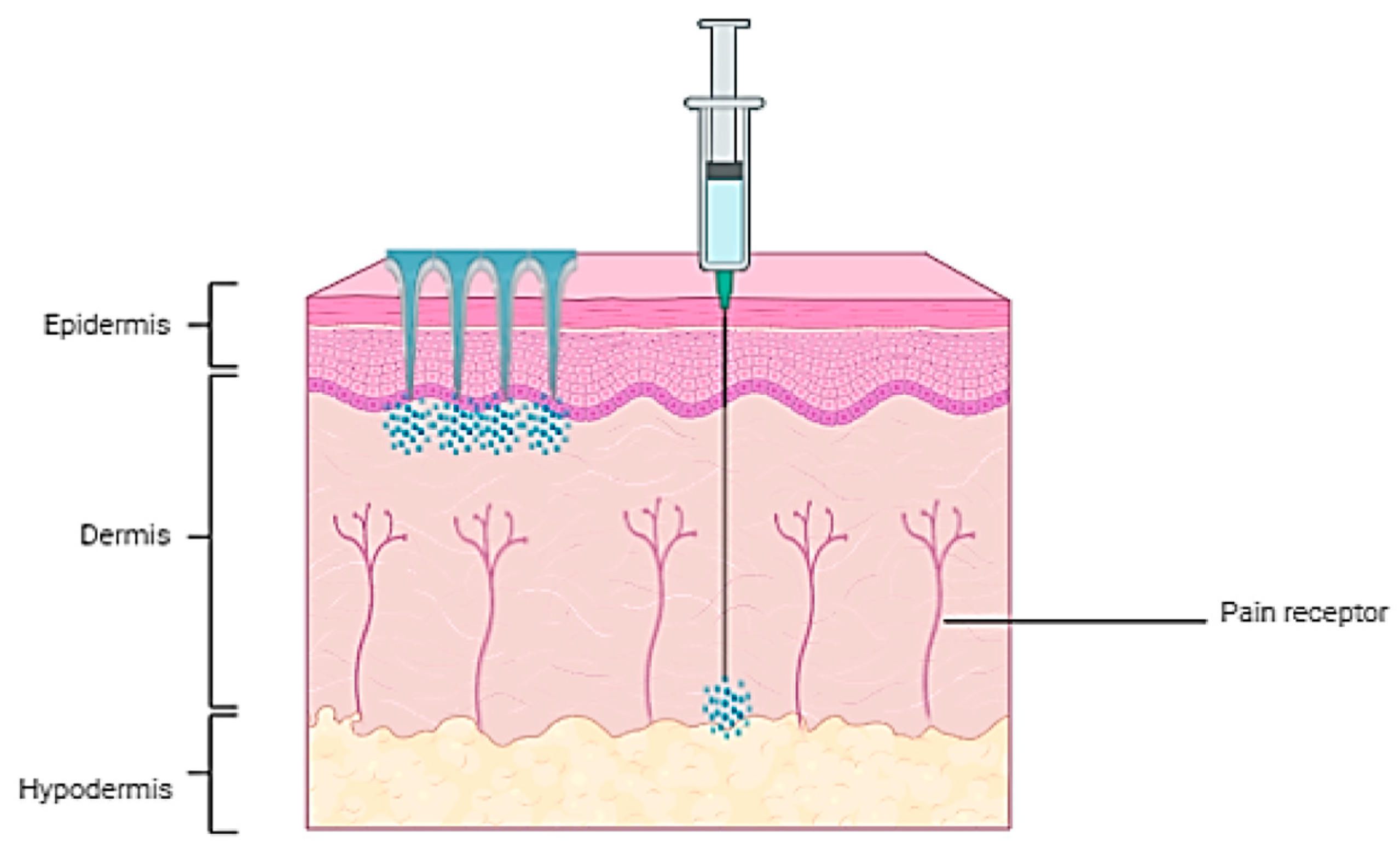

Among the newer strategies in the drug delivery and biosensing, the microneedle arrays (MNAs) have been received quite a lot of attention as the minimally invasive systems for a transdermal delivery and sampling [

3,

4]. By softly piercing through the stratum corneum without really triggering the pain receptors or causing any damages on the blood vessels, the MNAs are offering a painless access toward the interstitial fluid (ISF), which is a biomarker-rich medium that quite fairly reflects the blood composition [

5,

6]. This technology, in a way, is bridging the gap between an invasive blood testing and the noninvasive surface sensing, and it is enabling the applications like the continuous glucose tracking, lactate detection, and a real-time metabolite monitoring [

7,

8]. The integration of the MNAs with the flexible electronics and also with the wireless data transmission has been leading to the development of the smart wearable biosensors that are able to perform the multiplexed and real-time diagnostics [

9,

10]. These kinds of systems are already being used for the chronic disease monitoring, the personalized drug delivery, and even for an on-skin health analysis, showing the good level of biocompatibility, mechanical stability, and also the user comfort.

The intricate structure of MNAs has historically posed fabrication challenges [

11]. The conventional fabrication methods like the photolithography or the molding are usually limited when it comes for the scalability and the geometric accuracy. The other techniques such as the micromilling, lithography, and the injection molding can work quite well, but they are often requiring several complicated and costly steps, which again is making the large-scale production rather more difficult [

12,

13,

14,

15]. On the other hand, the three-dimensional (3D) printing is offering an unmatched design freedom and it allows the engineers to adjust the microneedle geometry, density, and even the hollow structures based on to the specific anatomical or clinical requirements [

11,

16,

17,

18]. The high-resolution 3D printing techniques like the stereolithography (SLA), digital light processing (DLP), and also the two-photon polymerization (2PP) are now getting more and more optimized for to produce the complex microneedle structures with a higher precision and with much shorter fabrication times [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. These developments are bringing the technology more close to the clinical utility by enabling the customizable MNA designs and also the integration with other devices for to control the function [

24]. The recent works have been showing that the 3D-printed MNAs can be incorporated with the conductive pathways, microchannels, and the bioresponsive coatings, which is significantly enhancing the versatility of the wearable diagnostic and therapeutic platforms [

25].

In addition, the emergence of the affordable and high-resolution 3D printers has been greatly lowering both the financial and the technical barriers, promoting the wider use of the MNA technology across the research laboratories and also the clinical environments [

26,

27]. This technique is also supporting the design of the multifunctional MNAs by incorporating the internal microchannels or the reservoirs, which are allowing for a controlled and localized drug delivery and opening the new possibilities for the theranostic applications [

26,

28,

29].

The materials development has been going in parallel with the fabrication improvements. The biocompatible photopolymer resins and the novel composites are now being used for to create the MNAs that can be able to deliver the challenging therapeutics. The polymers have been emerged as the ideal materials for the 3D-printed MNAs because of their biocompatibility, biodegradability, mechanical flexibility, and also the chemical tunability [

30]. The common polymers like the Poly(ethylene glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA), Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP), and the gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) can be engineered in the way to get the controlled stiffness and the dissolution behaviors, which is allowing the MNAs to act as the dissolving, hydrogel-forming, or even as the drug-loaded reservoirs [

31,

32]. The polymer-based MNAs are also making possible some stimuli-responsive features, where they can react to the things like the temperature, pH, or different biochemical signals for to provide the on-demand drug release or a more dynamic sensing function [

32].

The integration between the materials development and the improvements in the fabrication methods is supporting the real-time biosensing; for example, the recent designs of the hollow metallic microneedles are doubling as the electrodes for the glucose monitoring while also permitting the insulin delivery [

33]. The researchers have demonstrated about the ability of the 3D-printed MNAs for to sample the biological fluids safely from the tiny volumes (e.g., the perilymph in the inner ear) [

20], which is highlighting their potential in the diagnostics.

The polymeric 3D-printed MNAs that are combined together with the wearable systems are now standing at the very front of the smart and the more personalized healthcare. They are bringing together the advantages of the precise manufacturing, the flexible biopolymers, and also the digital connectivity for to offer the real-time monitoring, on-demand treatments, and an adaptive feedback control. This meeting point between the materials science, the biomedical engineering, and the additive manufacturing is likely reshaping the next generation of the healthcare, leading the way toward a more autonomous “wearable clinics” that can diagnose, treat, and also keep track of the patients continuously in their daily life [

5,

10].

In this review, we are trying to give the broad overview about the recent advances in the design, fabrication, and also the biomedical integration of the polymeric 3D-printed MNAs within the wearable healthcare technologies. The focus is mainly on to how the additive manufacturing is providing a more precise control over the microneedle geometry, the material choice, and also the device architecture for to reach the higher functionality, the better patient comfort, and a stronger personalization. The discussion is covering the main 3D-printing methods, the polymer materials, and also the different strategies for merging the MNAs with the flexible electronics, sensors, and the wireless parts. A special attention is given on the biomedical uses such as the continuous glucose tracking, the painless vaccination, and the on-demand drug release, together with the growing roles in the multiplexed biosensing and the physiological monitoring. The review is also talking about the ongoing challenges in scaling up the production, the clinical translation, and the regulatory acceptance, while it is pointing to the future directions that are involving the artificial intelligence, the self-powered systems, and the closed-loop therapeutic setups on the road toward the fully autonomous and the personalized wearable healthcare. The

Figure 1 is showing the different applications of the 3D-printed MNA integrated with the wearable devices.

2. Polymeric 3D Printed Microneedle Arrays

This section is providing an overview about the principles, benefits, and the technological advances in the polymeric 3D printing of MNAs, with an emphasis on its advantages over the conventional methods and also on its transformative impact toward the wearable healthcare platforms.

2.1. Advantages and Emerging Applications of Microneedle Arrays

The MNAs are penetrating only the stratum corneum and the upper epidermis, avoiding the nerve endings and delivering a nearly pain-free experience. This characteristic is making the MNAs particularly more appealing for the pediatric and the needle-phobic populations [

34,

35,

36]. The MNAs are delivering the drugs directly into the systemic circulation, which is ensuring the higher bioavailability and the faster onset of the action. This property is especially being beneficial for the biologics such as the peptides and the proteins, which are susceptible for the enzymatic degradation inside the gastrointestinal tract [

35,

37,

38].

The patient compliance is another area where the MNAs are really excelling. Their ease for use is allowing the self-administration, which is reducing the need of the trained healthcare professionals. This feature is being particularly advantageous for the chronic conditions that are requiring a frequent drug administration, such as the diabetes or the hypertension. The MNAs are also eliminating the risks related with the needle-stick injuries, reducing the burden from the medical waste and improving the overall safety [

39,

40,

41].

The precision and the control that are offered by the MNAs are further distinguishing them from the traditional methods. The MNAs are able to deliver the drugs in a more localized manner, which is minimizing the systemic exposure and reducing the risk for the side effects. Additionally, their ability for to incorporate the controlled-release mechanisms is allowing the sustained drug delivery through the time, reducing the frequency of the administration and improving the therapeutic outcomes. For instance, the dissolving MNAs that are made from the biodegradable materials can be releasing the drugs gradually as they are dissolving inside the skin, which is ensuring a steady therapeutic effect [

35,

36,

41].

Beyond their medical applications, the MNAs are also gaining more traction inside the cosmetic industry. They are being used for the anti-aging treatments, the skin rejuvenation, and also for the delivery of the active ingredients in the skincare products. The ability for to target the dermal layers without causing a significant discomfort has made the MNAs a quite popular choice for the cosmetic enhancements [

35,

40,

42].

As the MNA technology is continuing to evolve, its potential applications are expanding more into the diagnostics and also the personalized medicine. The recent innovations are including the MN-based biosensors that are capable for monitoring the biomarkers in the real time. These kinds of devices are providing a minimally invasive alternative for the continuous health monitoring, offering the valuable insights about a patient’s physiological state. The integration of the MNAs with the wearable technologies is further enhancing their utility, enabling the point-of-care diagnostics and also the remote healthcare management [

26,

36,

41,

43].

The

Figure 2 is showing a comparison between the conventional hypodermic needle injection and the MNA delivery.

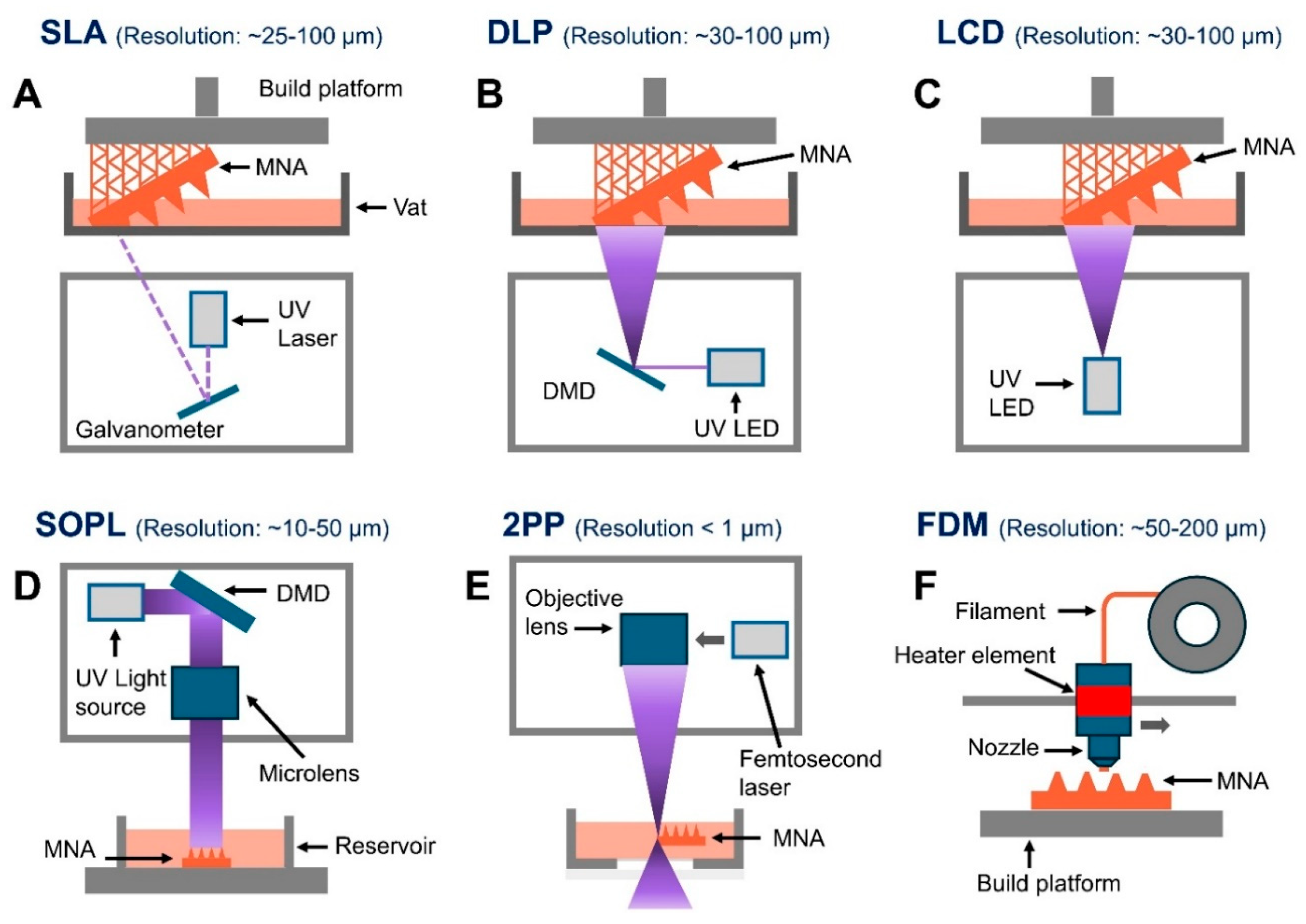

2.2. 3D Printing Techniques for Polymeric MNAs

Several 3D printing techniques have been adapted for the production of the MNAs, and each one is offering the unique advantages that are suited for the specific applications [

45,

46]. Among the diverse 3D printing techniques, the SLA, DLP, 2PP, and also the fused deposition modeling (FDM) are some of the most widely utilized methods for fabricating the MNAs. The SLA is among the most widely adopted 3D printing techniques for to fabricate the MNAs. This method is employing an ultraviolet (UV) laser for to selectively cure the liquid photopolymers into the precise solid structures. The SLA is offering the high resolution and the smooth surface finishes [

47]. It is being particularly well-suited for creating the intricate MN designs. Its versatility has been leading to an extensive use in the biomedical applications, including the development of the advanced drug delivery systems and the diagnostic tools, where the precision and the surface quality are quite critical [

17,

45]. The SLA has been extensively employed for the 3D printing of the MNAs [

13,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. It has been enabling the fabrication of various types from the MNAs, including the hollow, dissolvable, and also the solid forms, for the transdermal drug delivery applications [

54,

55,

56,

58]. Also, this technology is being utilized for to fabricate the master molds for the dissolvable MNAs that are designed for the ocular drug delivery [

52], as well as for the coated MNAs that are used for the intradermal insulin administration [

53].

Furthermore, the SLA-printed MNAs have been employed in some innovative applications such as the MNAs for the transdermal electrochemical sensing [

59] and also as the base substrates for the lab-on-a-MNA systems that are capable for a rapid biomarker detection inside the finger-prick blood samples. They have been also used for the MNAs that are facilitating the blood-free detection of the biomarkers such as the c-reactive protein and the procalcitonin in the ISF [

13].

The DLP is another widely used 3D printing technique for fabricating the MNAs. As a variation from the SLA, the DLP is improving the production efficiency by curing the entire layers of the photopolymer resin simultaneously through using a digital light projector [

60]. In other words, unlike the SLA 3D printing where the resin is being cured point by point, the DLP technology is projecting the light across the entire layer at once by using the projector. This approach is enabling the rapid curing for each layer, which is significantly accelerating the printing process [

61,

62]. The DLP technique has been extensively utilized for the 3D printing of the MNAs [

15,

26,

57,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68]. This method is offering a relatively high resolution, which is typically reaching to the micron scale [

69]. The DLP-printed MNAs that are fabricated from the polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) have been designed for the applications such as the on-demand drug delivery and the multiplexed detection of the biomarkers, including the pH, glucose, and also the lactate levels in the skin ISF [

26]. Additionally, the continuous glucose monitoring in the ISF has been successfully achieved by using the solid MNAs that are produced with the biocompatible and light-sensitive resins, as it was demonstrated through the in-vivo testing on the mice [

65]. Moreover, the DLP has been facilitating the development of the drug delivery systems that are employing the MNAs made from the biocompatible resins, which are enabling the increased permeability of the active compounds with the molecular weights that are ranging between 600 and 4000 Da in the buccal tissue [

15].

The Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) technique is another process that is being employed for the 3D printing of the MNAs [

56,

70,

71,

72]. Like the SLA and the DLP, the LCD technique is also a vat photopolymerization process that is using the light-curable resins for to fabricate the highly precise microstructures such as the MNAs. However, its key advantage is lying in offering a comparable resolution but at a much lower cost, which is making it particularly suitable for the large-scale manufacturing of the complex designs while still maintaining both the accuracy and the cost-effectiveness [

73]. Like the DLP, the LCD-based printing technique is offering the higher printing speeds than the SLA, since it is curing each layer in a single exposure instead of scanning point by point. The key distinction between the LCD and the DLP is lying in the way how the light is projected. In the DLP printing, a digital micromirror device is projecting the full image of each layer onto the resin surface, whereas the LCD printing is relying on a liquid crystal display screen that is selectively transmitting the light through the individual pixels for to solidify the resin layer by layer. This pixel-controlled illumination is minimizing the image distortion and is enhancing the uniformity, although it generally is resulting in a slightly longer curing time compared with the DLP systems [

74].

The Static Optical Projection Lithography (SOPL) is another emerging 3D printing technique that is being applied for the fabrication of the MNAs. In this approach, a patterned light field is statically projected for to initiate the polymerization inside the monomer solution according to the spatial distribution of the light intensity. This process is allowing for a rapid MNA fabrication without the need of any mechanical movement, achieving the exceptionally high throughput. Moreover, by just modifying the projected images, the SOPL can be producing the MNAs with diverse geometries and also with the structural variations [

17]. Furthermore, the compression testing has been demonstrating that the MNAs fabricated by using the SOPL are exhibiting a superior mechanical strength compared with those that are produced by the DLP printing. This technique is enabling a highly precise fabrication for the microneedles with the intricate geometries and is allowing the rapid design customization. The resulting MNAs are featuring the smooth surface morphologies that are minimizing the insertion-induced tissue damage and are enhancing the overall biocompatibility [

19].

The recent advancements in the 3D printing are including the 2PP, which is enabling the nanoscale precision. The 2PP technology can be creating the MNAs with the extremely sharp tips and also with the intricate internal features. Although the 2PP is costly and time-consuming, its ability for to produce the high-resolution structures is making it a quite promising choice for the research and also for the specialized applications [

17,

20].

The 2PP technology is using the ultrashort laser pulses from a near-infrared femtosecond laser for to selectively polymerize the photosensitive resins. This process is involving the nearly simultaneous absorption of the two photons, which is generating an electronic excitation that is equivalent with the one produced by a single photon having the higher energy. This absorption is resulting in a nonlinear energy distribution that is focused precisely at the laser’s focal point, with only minimal absorption outside of the immediate focal volume. When this energy is absorbed, the photoinitiator molecules inside the resin are initiating the polymerization process within the localized areas known as the “polymerization voxels,” where the energy is exceeding a specific threshold. Compared with the other techniques, the 2PP is offering a superior geometry control and a scalable resolution, while also reducing the costs that are associated with the equipment, facilities, and the maintenance in the etching and lithography-based methods. This has been making the 2PP a quite versatile tool for fabricating the solid and also the MNAs by using the materials such as the modified ceramics, inorganic–organic hybrid polymers, the acrylate-based polymers, polyethylene glycol, and more recently the water-soluble materials, with the highly promising results [

75].

One of the key advantages from the 2PP is its ability for to achieve the resolutions as fine as about 100 nm [

76]. The researchers have been employing the 2PP for to mold the dissolving and also the hydrogel-forming MNAs by using the aqueous blends from PVP and the poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) for the controlled drug delivery through the skin models [

75]. It has been also used for to fabricate the MNAs from the organically modified ceramic hybrid materials (Ormocer®) for the transdermal drug delivery [

77]. These MNAs were exhibiting the excellent mechanical stability, with no breakage and with minimal or almost no bending at the tip after the surgical use [

78].

Additionally, a hybrid method that is combining the 2PP with the electrochemical deposition has been developed for to create the ultra-sharp, gold-coated copper solid MN arrays for the inner ear drug delivery [

79]. Furthermore, the 2PP has been utilized for to produce the MNAs that are designed for the transdermal sensing of the electrolytes, such as the potassium (K⁺) ions [

80].

The FDM is another method that can be used for the 3D printing of the MNAs. In the FDM, the thermoplastic filaments are melted and extruded through the heated nozzle for to build the structures layer by layer. While this method is economical and simple, its resolution is quite limited, which is making it less suitable for creating the fine details that are required for the MNAs [

81,

82]. Despite this, the advances in the FDM technology have been enabling its use for the prototyping of the MNAs with the relatively simple geometries. Also, although its resolution is lower compared with the other 3D printing methods, the post-processing techniques like the chemical etching can be improving its utility for the MN fabrication. The FDM is being particularly suitable for the biodegradable MNAs [

83].

The FDM has been utilized in several studies for to produce the MNAs [

84,

85,

86,

87]. This 3D printing technique is being widely favored because of its rapid production, cost-effectiveness, easy accessibility, and also the versatility in the material usage [

88]. However, the post-processing is playing a quite critical role in the FDM, since the printed components are not immediately ready for to use. Once the printing is complete, the product is removed from the print bed, any supporting structures are detached, and the item is undergoing the post-processing for to enhance its surface quality [

89]. In the realm of the 3D printing of the MNAs, some innovative approaches have been successfully combining the FDM with the post-fabrication etching techniques for to create the needles having the optimal size and shape. These kinds of needles can penetrate into the skin, break off, and deliver the small molecules without requiring any master template or the mold [

84]. Additionally, the coated polylactic acid (PLA) MNAs have been developed for the effective transdermal drug delivery [

87].

The

Figure 3 is illustrating schematically the working principles from the key 3D printing techniques that are used for the polymeric MNA fabrication, including the SLA, DLP, LCD, SOPL, 2PP, and also the FDM.

2.3. Material Selection for 3D Printing of Microneedles

The selection of the materials is a quite crucial aspect in the 3D printing of the MNAs, as it is directly affecting their mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and also the overall functionality. The polymers, ceramics, and the metals are the primary materials that are used, and each one is chosen based on to the intended application. The polymers are the most commonly employed materials because of their versatility and the good biocompatibility. The PLA, polycaprolactone (PCL), and also the PVA are the popular choices for creating the biodegradable and dissolvable MNAs. These materials are ideal for the drug delivery applications, since they can encapsulate the active pharmaceutical ingredients and release them gradually while the MNAs are dissolving in the skin [

91,

92]. The hydrogels, which are the water-absorbing polymers, are another important class of the materials. They are used for to create the hydrogel-forming MNAs that are swelling upon the contact with the skin fluids, enabling the sustained drug release or the biosensing capabilities [

18].

The ceramics are offering the superior mechanical strength and are often being used in the applications that are requiring the durable and reusable MNAs. However, the brittleness from the ceramics is posing some challenges in their fabrication and also during the application [

20,

93]. The metals, such as the stainless steel, are well known for their durability and the mechanical robustness [

94].

The hybrid materials and the composites have been gaining attention because of their ability for to combine the desirable properties from the different materials. For instance, the polymer–ceramic composites can be offering the flexibility from the polymers together with the strength from the ceramics [

77]. The advances in the bioinks that are specifically designed for the SLA, DLP, and also the 2PP processes have been further expanding the range of the materials that are available for the MN fabrication, allowing the direct integration of the drugs or the biologically active agents inside the MN structure [

17,

20].

The hydrogels are a vital category that are swelling upon the contact with the skin fluids for to deliver the drugs or to facilitate the biosensing. The photopolymers that are used in the SLA and DLP processes are valued because of their ability to produce the high-resolution MNAs, but they are requiring the careful selection for to ensure the biocompatibility [

60].

Another major challenge in the future development for the 3D-printed MNAs is the scalability. Although the 3D-printed MNAs are offering a remarkable potential, expanding their production for the widespread clinical applications is still remaining a main challenge. The process of the 3D printing is depending on the specialized equipment and the materials, which is resulting in the high production costs that are hindering the large-scale manufacturing. For instance, the high-resolution 3D printers are often being too slow and too expensive for the commercial applications. Also, the scalability is depending on to maintaining the consistent quality as the production volumes are increasing. Ensuring the uniformity in the dimensions, tip sharpness, and the material properties across the batches is quite crucial for to guarantee both the safety and also the effectiveness. Another significant obstacle is the lack of the standardized manufacturing methods and also the inherent complexities during the production. Many developers are still relying on the manual, lab-scale fabrication methods, which are not suitable for to support the mass production. The wide variation among the MNA designs, formulations, and also the applications is necessitating the development of the specialized equipment and the innovative manufacturing processes [

95]. Addressing these scalability challenges is critical for to transition the MNAs from the research prototypes toward the commercially viable medical devices that can be integrated into the broader healthcare markets.

3. Integration of Microneedle Arrays with Wearable Devices

This section is exploring about the design principles, materials, and the technologies that are enabling the seamless integration of the MNAs with the wearable platforms, focusing on the skin conformality, sensor coupling, wireless data transfer, and also the user-centered functionality. The recent progress in the 3D printing has been providing the versatile methods for fabricating the hollow and solid MNAs that are tailored for the continuous contact with the skin. The layer-by-layer customization in the 3D printing process is enabling a precise control on the dimensions and the architectures that are critical for a secure and painless skin penetration [

45].

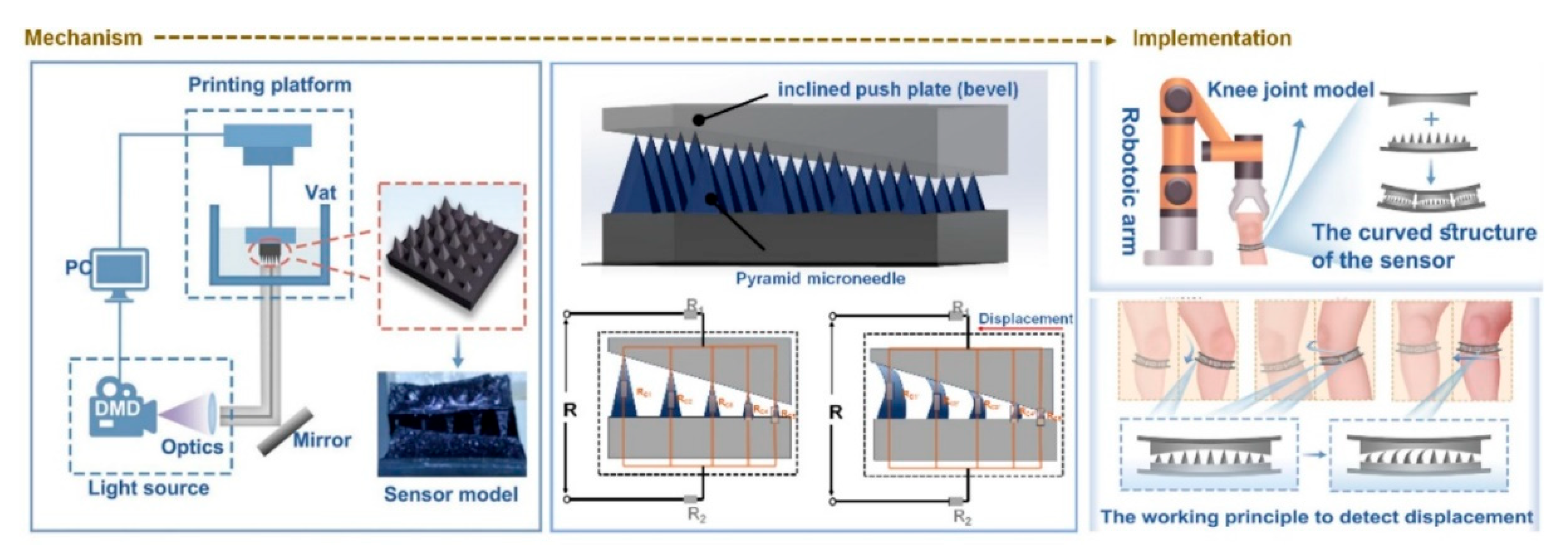

The material innovations are also playing a crucial role for enhancing the skin adherence and the conformality. Keirouz et al. [

96] have reported the conductive polymer-coated 3D-printed MNA, which is allowing the repeated skin insertions without losing the conductivity or the structural integrity. Economidou and the colleagues [

54] have further advanced this by integrating the hollow MNAs with the microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), enabling the controllable and personalized drug delivery while maintaining the stable contact on the skin tissue. Also, Zhang and colleagues [

97] have introduced a high-sensitivity hydrogel-based MNA wearable sensor that was fabricated through the DLP 3D printing, which was designed for to conform on the joint surfaces and to capture the subtle biomechanical deformations, illustrating about the adaptability of the MNAs for the complex anatomical sites.

Beyond the material flexibility, the stimuli-responsive designs are being increasingly explored for to improve the conformal wear and the responsiveness toward the physiological conditions. The smart MNAs that are composed from the stimuli-responsive polymers can adjust their functionality according to the environmental triggers, providing the controlled biomarker detection and the on-demand therapeutic release [

32]. The multifunctional MNAs can be integrating the biosensors, microfluidics, and the smart biomaterials, thereby enabling the closed-loop systems that are remaining continuously attached on the skin while autonomously managing the biosensing and the drug delivery [

98].

The integration into the personalized healthcare workflows is demonstrating the translational promise from the skin-conformal MN platforms. Yang et al. have introduced an MNA-based continuous biomarker and drug monitoring system that was enabling the real-time pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluations in the diabetic patients, seamlessly connecting the skin-conformal MNA sensors with the smartphone interfaces for to provide the continuous clinical feedback [

99]. This study illustrated how the skin-conformal MNA platforms are not only improving the contact stability but also forming the foundation for the precision medicine systems that are capable for the real-time therapeutic adjustment.

The recent innovations are demonstrating about the effectiveness from the MNAs in merging the biosensing with the flexible electronic substrates. Zhan et al. [

100] have developed a 3D-printed hollow MNA-based extraction system that was integrated with the patterned electrodes, achieving a minimally invasive monitoring of the analytes such as the glucose, pH, and the hydrogen peroxide. In another research, our group has presented a remotely controlled theranostic platform that was based on the hollow MNAs embedded with the colorimetric and the electronic sensors, which was coupled to a smartphone interface for the continuous health monitoring and the on-demand drug delivery. This system was showcasing the potential from the flexible and portable electronics for to democratize the healthcare access across the geographic and also the socioeconomic barriers [

26]. Also, Rezapour Sarabi and colleagues [

101] have shown how the 3D printing is enabling the precise fabrication for the MNA-based biosensing patches, which are compatible with the polymeric and the inorganic materials, for to extract and analyze the ISF.

The flexible electronics are also underpinning the emergence from the MNA-based real-time biosensors for the continuous clinical applications. The flexible and miniaturized designs are supporting the closed-loop systems, which are integrating the biosensing with the therapeutic delivery, offering a new paradigm for the personalized medicine [

9].

The smart multifunctional MNA platforms are increasingly incorporating the wireless modules for to link the biosensing and the drug delivery systems with the external devices. Despite these advances, some challenges are still remaining in minimizing the power consumption, ensuring the secure data transfer, and maintaining the signal stability during the continuous skin contact.

The self-powered technologies are offering a quite promising alternative. Liang et al. [

102] have developed a self-powered hydration-monitoring and drug-delivery patch for to treat the atopic dermatitis, which was integrating a piezoelectric generator for to harvest the biomechanical energy from the body movements. This system was operating autonomously, combining the hydration sensing with the on-demand MNA drug release in a closed-loop format, thereby eliminating the reliance on the external batteries.

The wireless energy transfer is another emerging strategy. Zhang et al. [

103] have introduced a wirelessly powered near-infrared light MNA device that was designed for the synergistic wound healing. Their platform was integrating the drug-loaded MNAs with a near-infrared (NIR) Light-Emitting Diode (LED) array that was powered through the electromagnetic induction, enabling a stable energy delivery without the bulky power sources. By combining the phototherapy with the localized drug release, the system was demonstrating how the wireless powering can be expanding the therapeutic capabilities while maintaining the device thinness and the flexibility.

The energy harvesting from the motion or the body heat, when it is combined with the wireless charging through the Near-Field Communication (NFC) or the inductive coupling, is providing a pathway toward the autonomous and patient-friendly systems that are capable for the continuous health monitoring [

104].

One effective strategy is by combining the rigid MNA with the soft and flexible substrates. Rajabi et al. [

105] have demonstrated the flexible and stretchable MNAs that were integrating the stainless steel MNAs into an elastomeric base. This design was allowing the patch for to adapt on the skin wrinkles and the movements while still ensuring the painless penetration, illustrating how the hybrid material selection is enhancing both the functionality and the comfort.

The bioadhesive and hydrogel-based platforms are another important design pathway. Xue et al. [

106] have developed a wearable and flexible ultrasound MNA that was incorporating a bioadhesive hydrogel elastomer, which was ensuring a robust adhesion on the curved and dynamic skin surfaces, minimizing the detachment during the motion.

The user comfort is also linked with the system ergonomics and the device usability. Economidou et al. have demonstrated a 3D-printed hollow MNA MEMS device that was capable for a precise and personalized delivery, showing how the ergonomic designs can reduce the treatment complexity and also enhance the patient adherence [

54].

4. Biomedical Applications of MNA-Integrated Wearables

4.1. Biosensing and Continous Health Monitoring

Different studies have been investigating about using the MNA-based wearable devices for the biosensing and the health monitoring. For instance, Parrilla et al. [

107] have demonstrated a 3D-printed hollow MNA potentiometric platform that was functionalized with the conductive inks, validating its ability for to sample the ISF and to detect the biochemical analytes on the skin in a minimally invasive manner. In another study, Zhan et al. [

100] have extended this concept by integrating the 3D-printed hollow MNAs with the patterned electrodes, enabling the electrochemical detection for the glucose along with the other metabolites. Their system was demonstrating an accurate glucose detection both in vitro and in vivo, highlighting the potential from the MNAs for the minimally invasive and continuous health monitoring.

Also, Zhou et al. [

108] have developed a 3D-printed MNA for the real-time and painless glucose monitoring in the interstitial fluid. The biocompatible resin needles (400 µm base, 1200 µm height) were coated with the Au/Prussian Blue (PB)/glucose oxidase (GOD) and the Ag/AgCl electrodes for the selective enzymatic glucose detection. The compact circular layout was minimizing the insertion force and improving the wearer comfort. The electrochemical tests have demonstrated the high sensitivity (3.5 nA mM⁻¹), strong linearity (R² > 0.96), and the excellent selectivity against the interfering metabolites, indicating a low-cost and wearable platform for the continuous diabetes management.

The recent studies are highlighting the promise from the 3D-printed and flexible MNA electrodes. Liu et al. [

109] have developed a 32-channel MNA dry electrode patch that was capable for recording the electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiography (ECG), and the electromyography (EMG) signals with a markedly reduced impedance compared with the conventional electrodes. Li et al. [

110] have further advanced this concept by developing a high-performance flexible MNA electrode for the polysomnography and the wearable electrophysiology, demonstrating the superior stability and comfort during the sleep studies. Juillard et al. [

111] have developed the hydrogel-based biodegradable MNAs for to enable the safe and long-term electrophysiological monitoring, offering the new strategies that are suitable for the transient or even the pediatric applications.

Parrilla et al. [

111] have demonstrated a wearable 3D-printed solid MNA voltammetric sensor for the real-time uric acid detection in the interstitial fluid. The device was integrating the three gold-coated MNA electrodes, working, reference, and counter, that were fabricated through the stereolithographic 3D printing and the metal sputtering. The nanostructured gold surfaces were significantly enhancing the electrocatalytic activity, achieving a high sensitivity (25 nA μM⁻¹) and a wide linear range (150–500 μM) that is relevant for the physiological uric acid levels. The sensor was exhibiting an excellent reproducibility, a good selectivity against the common interferents (glucose, ascorbic acid, urea), and also a mechanical robustness for the repeated skin insertions.

In another study, Zhang et al. [

97] have reported a 3D-printed MNA-based wearable sensor that was capable for the high-sensitivity detection of the human joint motion. The device was integrating a hydrogel MNA with a flexible conductive substrate, enabling it for to sense the subtle mechanical deformations that are generated during the knee flexion, extension, torsion, and also the lateral movements. The

Figure 4 is showing their designed 3D-printed MNA-based wearable motion sensor that is coupling the structural precision with the skin-conforming flexibility. The schematic is outlining the complete workflow, from the MNA fabrication via the stereolithographic 3D printing toward the integration with the hydrogel-based conductive substrate. When the patch is adhering on the skin, the mechanical deformation that is generated by the joint movements (such as the flexion or extension) is transmitted through the microneedle tips toward the underlying sensing layer, producing a proportional electrical resistance change. The figure is also depicting how the optimized microneedle geometry is enhancing the strain transfer efficiency and the adhesion, ensuring an accurate signal capture even under the dynamic motion. This mechanism is enabling the real-time biomechanical monitoring with a high sensitivity and a minimal discomfort, demonstrating how the polymeric MNA-integrated wearables can be serving as the reliable human–machine interfaces for the neuromuscular diagnostics, rehabilitation feedback, and the personalized movement tracking [

97].

4.2. Drug Delivery

The MNA-assisted drug delivery has been emerging as a transformative platform that is bridging the gap between the conventional hypodermic injections and the topical administration [

44]. By forming the transient microchannels without stimulating the dermal nerves or the blood vessels, the MNAs are significantly improving the patient compliance and allowing for the self-administration, key attributes for the next-generation wearable therapeutics. The integration of the MNAs into the wearable systems is introducing new opportunities for the delivery of the drugs, vaccines, and the biomolecules, especially when it is coupled with the microfluidic reservoirs or the electronic sensors for the dosage regulation.

Among the various types of the MNAs, the hollow MNAs are representing a particularly promising design for the wearable transdermal therapy. Their internal lumens are permitting the active pumping or the diffusion of the drug solutions from a reservoir into the skin, mimicking the functionality of a miniature syringe while avoiding the pain and the infection risk. This type of the MNAs can accommodate the large molecules such as the peptides, proteins, and the nucleic acids that are otherwise impermeable through the skin [

112]. The advent from the 3D printing technologies has been revolutionizing the design and the manufacturability for the hollow and the polymeric MNAs, allowing a precise control on the geometry, the internal channels, and also the mechanical strength [

113].

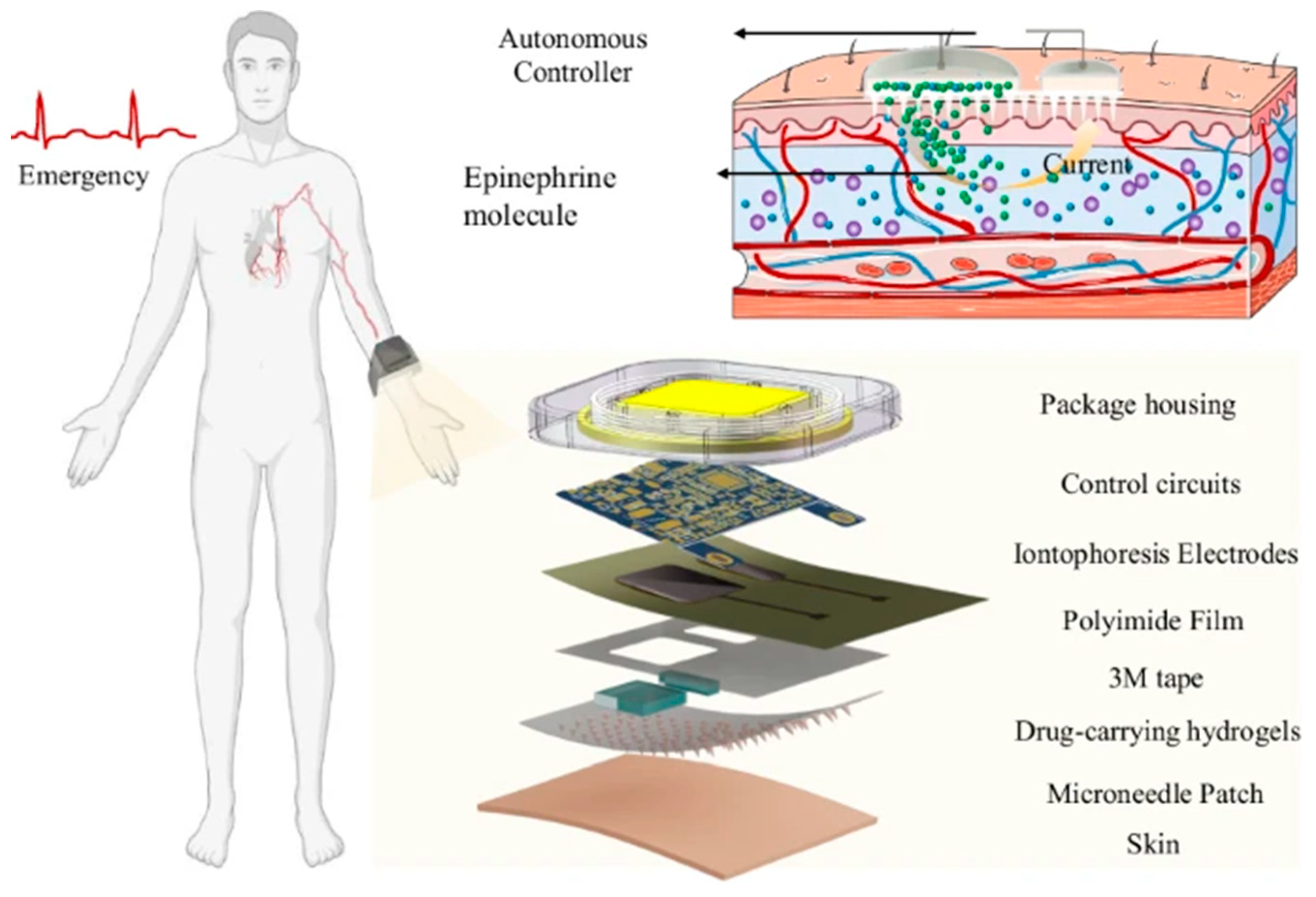

The drug delivery by using the MNA-integrated wearable devices have been investigated in several different studies. For example, Jin et al. [

114] have developed a wearable self-aid MNA-integrated device for the transdermal delivery of the epinephrine, illustrating how integrating the MNAs with the electronic actuation can transform the conventional drug delivery into an intelligent and self-regulated process. They have developed a wearable patch that was combining the hydrogel-based MNAs, the conductive materials, and an iontophoretic control system for to enable the active and adjustable transdermal administration of the epinephrine. Unlike the passive MNA patches that are relying on the diffusion or the dissolution, this design was allowing the users for to regulate the dosage in the real time through the electronic control, representing a significant step toward a more personalized and responsive pharmacotherapy. The research has demonstrated that the active MNA systems can achieve the rapid onset of the drug action comparable with the injections, yet with the improved comfort, safety, and the user autonomy. The concept of the “press-to-deliver” operation is making it possible for to use such devices for the emergency self-aid, particularly in the situations where the immediate medical assistance is not available. The

Figure 5 is illustrating schematically their developed wearable self-aid MNA-based device. The figure is showing the multilayer structure from the device, consisting of the hydrogel MNAs, conductive interfaces, and an iontophoretic circuit that is enabling the electronically controlled and on-demand drug delivery. The schematic is also depicting the user-activated operation and the emergency self-aid application scenario [

114].

In another study, Tan et al. [

115] have developed a battery-free and self-propelled bionic MNA system that is enabling the drug delivery without any external power sources. Inspired by the bombardier beetle’s defensive spray mechanism, the device was integrating a miniature “bionic engine,” a drug reservoir, and the hollow MNA into a compact 3D-printed patch. The propulsion force was arising from a catalytic reaction between the platinum nanoparticles and the hydrogen peroxide, generating the oxygen pressure that is actively driving the drug through the MNA into the skin. This design is eliminating the need for the pumps, wiring, or batteries while still allowing the precise manual activation through a simple finger press. The in vivo pharmacokinetic studies on the rats by using the levonorgestrel as a model contraceptive drug have revealed a controlled release that was maintaining the therapeutic plasma levels within the desired range for the extended durations. The drug absorption was proportional with the dosage and was sustained up to 54 h after the repeated administrations. The histological and the cytocompatibility assessments have confirmed the minimal inflammation, high cell viability, and negligible tissue irritation, supporting an excellent biocompatibility. The

Figure 6 is illustrating their developed bioinspired propulsion principle that is based on the catalytic gas generation, the structural integration between the bionic engine and the hollow MNA, and the representative results that are showing the controlled and repeatable drug release without any external power [

115].

4.3. Painless Vaccination Platforms

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a renewed urgency toward the development of the alternative vaccination technologies. For example, the dissolvable MNAs could be utilized for the COVID-19 immunization, highlighting their ability for to deliver the vaccines into the epidermis and the dermis that are rich in the antigen-presenting cells, thereby enhancing the immunogenicity when compared with the intramuscular injections [

116]. The research has showed the benefits from the MNA-based delivery, including the avoidance of the cold-chain storage, reduced medical waste, and also the possibility for the large-scale distribution without the need of the professional administration. This paradigm is being especially relevant for the rapid-response vaccination campaigns during the pandemics.

The studies have been showing the versatility from the MNAs in the transdermal delivery for the biopharmaceuticals, including the vaccines, therapeutic proteins, and the nucleic acids [

117]. The MNA-mediated immunization is offering both the dose-sparing effects and the enhanced patient acceptance due to its pain-free administration. The advances in the 3D printing and the polymeric MNA fabrication are enabling the precise control on the geometry, the mechanical strength, and the drug-loading efficiency, which are critical parameters for the vaccine delivery patches. Importantly, the use of the biodegradable polymers is allowing the needles for to dissolve safely within the skin, eliminating the sharp waste and lowering the infection risks.

The integration from the wearable technologies is further amplifying the potential from the MNA vaccination systems. A research has presented a wearable and flexible ultrasound MNA for the cancer immunotherapy, showing how the dissolvable MNAs that are combined with the soft and skin-conformal electronics can achieve a robust adhesion, painless drug delivery, and the localized immune modulation [

106]. While this work was focusing on the oncology, its design principles, the flexible substrates, bioadhesive interfaces, and the minimally invasive MNA insertion, are directly applicable toward the vaccination wearables. By coupling the antigen-loaded polymeric MNA with the wearable platforms, the painless vaccination patches can be developed for to provide a sustained immune stimulation, potentially coupled with the biosensing and the feedback control for the precision immunization.

Together, these advances are highlighting the growing feasibility from the MNA-integrated wearables as the painless vaccination platforms. By combining the precision from the 3D-printed polymeric MNAs with the dissolvable materials and the wearable electronics, the future vaccine delivery systems could achieve an unprecedented accessibility, safety, and also the patient compliance. Such platforms are not only promising to overcome the needle-associated barriers but also offering a scalable and sustainable approach for the global immunization efforts

4.4. Personalized and On-Demand Drug Delivery

The MNA-integrated wearables are emerging as powerful tools for the personalized and on-demand drug delivery, addressing the limitations from the conventional transdermal and systemic administrations. A central innovation in this domain is the development for the remote-controlled MNA systems. A hollow 3D-printed MNA platform that was capable for both the biosensing and the drug delivery, activated by the external stimuli for the on-demand release, has been developed by our group [

26]. By embedding the colorimetric sensors and enabling the wireless actuation, this system was demonstrating how the MNAs can transition from the static drug depots into the dynamic therapeutic devices that are tailored to the individual’s physiological state.

The innovations in the multifunctional MNAs are also enabling the simultaneous biosensing and the therapeutic interventions. The MNAs are capable for sensing, extracting the fluids, and delivering the drugs, underscoring the need for the materials and the fabrication techniques that are supporting the multiplex operations. There are challenges for achieving the stable performance, material biocompatibility, and the robust adhesion in the wearable contexts, but it is underscored that the multifunctionality is critical for to advance the on-demand therapies [

98].

The foundation for such strategies has been established by Economidou et al., who have developed a 3D-printed hollow MNA microelectromechanical system (MEMS) that was designed for the controlled and personalized delivery of the small molecules [

54]. This work was highlighting the capacity from the additive manufacturing for to produce the customized needle geometries and the channels, optimizing the drug delivery profiles based on to the patient-specific requirements. Such devices can deliver the precise doses directly into the dermis, where the high vascularization is ensuring a rapid absorption.

The stimuli-responsive MNAs are representing another important class from the on-demand platforms. The smart polymers that are responsive to the pH, temperature, reactive oxygen species (ROS), or the light are enabling the triggered release of the therapeutics at the targeted sites [

32]. For example, the pH-responsive MNAs can selectively release the anti-inflammatory drugs in the diseased tissues, while the light-responsive systems are enabling a precise spatiotemporal control. These approaches are being particularly promising for the chronic diseases that are requiring the adaptive dosing strategies.

The wearable MNAs are also being combined with the self-powered systems for to enhance the autonomy. For example, a hydration-monitoring and drug-delivery patch has been developed that was harvesting the biomechanical energy for to sustain the closed-loop treatment for the atopic dermatitis [

102]. This design is eliminating the reliance on the external power sources and providing a responsive therapy that is aligned with the patient-specific hydration levels. Such innovations are paving the way toward the personalized and long-term management for the dermatological and metabolic disorders.

Wu et al. [

118] have introduced a wearable acoustic AMNA platform for the on-demand and programmable transdermal drug delivery. The system was integrating the 3D-printed hollow MNAs with a miniaturized piezoelectric transducer that was controlled through a Bluetooth-enabled smartphone app. The acoustic waves were generating the localized microvortices at the needle tips, actively pumping the liquid drugs through the skin with a precise dosage control. The device was supporting the single, batch, and continuous release modes, enabling the personalized treatment scheduling. The in vivo mouse studies have demonstrated the accurate dosage regulation, good biocompatibility, and a rapid skin recovery, showcasing a next-generation approach toward the smart and user-controlled therapeutic delivery for both the chronic and acute disease management.

In another research, Razzaghi et al. [

26] have developed a wearable theranostic platform that was integrating the colorimetric sensing and the on-demand drug delivery by using the 3D-printed hollow MNAs. The device was combining a biosensing compartment for quantifying the pH, glucose, and lactate with a remotely triggered ultrasonic atomizer that was enabling the wireless and controlled drug administration. The mechanical tests have confirmed the MNAs’ structural integrity and a consistent penetration force, while the ex vivo experiments on the pig skin have verified a uniform dye diffusion, confirming the reliable tissue insertion. The system was demonstrating the precise colorimetric sensing across the physiologically relevant ranges, using a smartphone-based application for the real-time analysis. The ultrasonic-assisted drug delivery was significantly enhancing the diffusion through the hydrogel models compared with the topical or the passive MNA delivery, and the modulation of the ON–OFF cycles was validating the controllable dosing profiles. This study was demonstrating a multifunctional and smartphone-controlled MNA that was capable for both the non-invasive biochemical monitoring and the wireless on-demand drug delivery, marking a major step toward the closed-loop wearable therapeutics. The

Figure 7 is depicting their 3D-printed MNA-integrated system. This integrated system is exemplifying a self-contained wearable patch that is capable for the real-time sensing and the programmable therapeutic administration [

26].

In another study, Yang et al. [

99] have developed an MNA-based continuous biomarker/drug monitoring (MCBM) system that is unifying the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessment for the personalized diabetes therapy. The platform was integrating the dual microneedle electrochemical sensors that were capable for simultaneously detecting the metformin and glucose concentrations inside the interstitial fluid (ISF). Each microneedle was functionalized with a nanoenzyme-modified electrode, ensuring the high selectivity, sensitivity, and stability under the physiological conditions. The real-time ISF analysis was wirelessly transmitted into a smartphone interface, which was computing the metabolic feedback for to inform the dynamic dose adjustment. In the in vivo experiments, the MCBM patch has achieved a strong correlation with the blood glucose profiles and the pharmacological dosing curves, demonstrating a reliable pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic (PK–PD) coupling during the metformin administration. This closed-loop sensing framework is highlighting how the MNA-integrated wearables can transcend from the single-parameter monitoring for to provide the continuous therapeutic feedback and the precision dosage control that is tailored to the individual physiology. The study is representing an important step toward the next-generation intelligent drug-delivery systems, merging the biochemical sensing, data analytics, and wearable connectivity for to enable the truly smart, adaptive, and personalized healthcare management. The

Figure 8 is showing their designed integrated MNA-based PK–PD monitoring system that is enabling the real-time and personalized drug management. The schematic is illustrating the overall architecture from the MNA-based continuous biomarker/drug monitoring (MCBM) platform, which is combining the dual electrochemical microneedle sensors for the simultaneous detection of the metformin and glucose in the interstitial fluid. The system is coupling these biochemical measurements with the wireless data transmission toward a smartphone interface, where the customized algorithms are processing the collected signals for to map both the drug kinetics and the glucose response profiles. This integrated feedback loop is allowing the dynamic adjustment for the therapeutic dosing based on to the patient’s metabolic state. The figure is also highlighting the device’s wearable form factor, the 3D-engineered MNAs, and the nanoenzyme-modified electrodes, which are collectively ensuring the stable signal acquisition and the high analytical sensitivity. Overall, the figure is effectively visualizing how the MNA-integrated wearable systems can unify the biosensing, pharmacological modeling, and the wireless communication into a closed-loop framework for the personalized and adaptive therapy [

99].

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

One of the main challenges in developing the 3D-printed MNA-integrated wearable devices is about the regulatory issues. More specifically, the regulatory pathways for the 3D-printed MNAs as the medical devices or the drug delivery tools are quite complex. The dual nature from the MNAs, being both a device and a drug delivery system, is complicating the approval processes, requiring the compliance with multiple sets of the regulations [

78,

119]. The regulatory approval is often requiring a demonstration about the consistent and safe penetration depths for to avoid reaching the dermal vasculature or the nerves. The studies like those by Defelippi et al. have been focused on the depth control, but the further standardization is still needed [

120]. Currently, the approvals for the MNAs are decided on a case-by-case basis rather than through a unified regulatory system, leading for the prolonged licensing processes and slowing down the market entry. For to solve this issue, a comprehensive regulatory framework is needed for to cover the key aspects like the device shape, formulation, sterilization, and also the packaging. Integrating the current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) guidelines and applying a quality-by-design approach would be facilitating the approval process and improving the reliability for the MNAs as the pharmaceutical products [

121].

In addition to the regulatory challenges, the development of the MNAs is also facing significant challenges in the patenting and the intellectual property. Numerous patents have been already issued that are related with the 3D-printed MNAs [

122,

123,

124]. The increasing number from the patents in this field, which are predominantly held by the industry, is highlighting the competitive nature for the innovation. The overly broad or restrictive patents can be hindering the technological progress by limiting the competition and the accessibility. With the patents covering the diverse aspects such as the drug delivery, fabrication methods, and the device applications, securing the freedom for to operate is becoming quite complex. Additionally, the overlapping claims and the broad Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) classifications are creating the legal uncertainties, which can potentially slow the commercialization. The future advancements are requiring the clearer regulatory frameworks and the collaborative licensing models for to balance the innovation with the accessibility and for to ensure a sustainable development in the MNA technology [

125]. Additionally, strengthening the collaboration between the regulatory agencies, industry stakeholders, and the patent offices can be helping to establish the clearer guidelines for the MNA patenting while balancing the innovation together with the market accessibility.

The future development of the 3D-printed MNAs for the wearable devices is facing significant challenges in the clinical translation and the trials. Despite the encouraging laboratory findings, translating these innovations into the clinical practice has been quite a challenge. The limited availability for the long-term clinical data is still remaining a major hurdle for the regulatory approval and the widespread adoption. While there has been an increase in the clinical studies, with a shift from the early-stage trials (Phase 1 and 2) toward the later stages (Phase 3 and 4), a large proportion from the trials are still remaining unclassified, which is indicating the regulatory uncertainty. Many trials are focusing on the drug delivery, mainly targeting the skin conditions, vaccines, and also the ocular treatments, but there is still a lack of the large-scale trials for to establish the long-term safety and also the efficacy. Additionally, the industry-sponsored trials are fewer than the academic studies, which can potentially delay the commercialization. Overcoming these hurdles will be requiring a more coordinated effort between the academia, industry, and the regulatory agencies for to streamline the approvals and accelerate the clinical adoption [

125,

126].

Another major challenge in the future development for the 3D-printed MNAs for the wearable devices is about the scalability. Although the 3D-printed MNAs are offering a remarkable potential, expanding their production for the widespread clinical applications is still remaining as a main challenge. The process of the 3D printing is depending on the specialized equipment and the materials, resulting in the high production costs that are hindering the large-scale manufacturing. For instance, the high-resolution 3D printers are often being too slow and expensive for the commercial applications. Also, the scalability is depending on maintaining the consistent quality as the production volumes are increasing. Ensuring the uniformity in the dimensions, tip sharpness, and the material properties across the batches is crucial for to guarantee both the safety and the effectiveness. Another significant obstacle is the lack of the standardized manufacturing methods and the inherent complexities of the production. Many developers are still relying on the manual, lab-scale fabrication methods, which are not suitable for to support the mass production. The wide variation among the MNA designs, formulations, and also the applications is necessitating the development of the specialized equipment and the innovative manufacturing processes [

95]. Addressing these scalability challenges is critical for to transition the MNAs from the research prototypes toward the commercially viable medical devices that can be integrated into the broader healthcare markets.

The choice of the materials is significantly impacting the mechanical strength and the biocompatibility from the MNAs. The polymers are often lacking the mechanical robustness that is required for the effective skin penetration without breakage [

127]. The metals and the ceramics are offering the higher strength but are harder for to fabricate with the high precision by using the 3D printing techniques [

128,

129]. Also, the fabrication of the MNAs is presenting several technical difficulties. Achieving the desired geometry, especially for the Inner Diameter (ID) and the Outer Diameter (OD) from the needles, is quite challenging. Even the high-resolution 3D printing techniques are facing some limitations in fabricating the extremely fine and uniform bore sizes [

119,

128,

129]. Despite the advancements in the 3D printing, several challenges are still persisting in the 3D printing for the MNAs. The consistent lumen formation is remaining a significant hurdle, since even the minor defects can compromise the fluid flow. The material biocompatibility is another critical issue, especially for the long-term applications.

Scale up the production for the MNAs while maintaining the cost-effectiveness is also a significant hurdle. The 3D printing is offering the customization and the precision but at a high cost per unit compared with the traditional manufacturing methods like the molding. This is especially problematic for the applications that are requiring the large-scale deployment [

43,

61]. The fabrication of the MNAs is requiring the specialized equipment and the skilled personnel, which is adding to the overall cost. Training and retaining a workforce that is proficient in the 3D printing technologies is still remaining a bottleneck in many regions [

119,

128].

Maintaining the uniformity across the batches is also challenging because of the sensitivity from the 3D printing processes to the parameters like the temperature, resin composition, and the printing speed. Such variability can be leading to the inconsistencies in the needle dimensions and the drug delivery performance [

119,

127].

6. Conclusion

The integration of the polymeric 3D-printed MNAs with the wearable devices is representing a transformative advancement in the evolution for the personalized and connected healthcare. Through the convergence between the additive manufacturing, smart materials, and the flexible electronics, these hybrid systems are redefining how the physiological data is being acquired, processed, and acted upon in the real time. Unlike the conventional wearables that are mainly monitoring the superficial signals, the MNA-based platforms are penetrating through the skin’s outer layer for to access the interstitial fluid (ISF), which is a rich biochemical medium that mirrors the blood composition, enabling the minimally invasive monitoring, precise drug delivery, and the continuous therapeutic feedback. This unique capability is positioning the MNA wearables as a cornerstone technology for the next-generation digital health systems that are aiming for to merge the diagnostics, therapy, and the decision support within a single skin-conformal patch.

The recent progress in the 3D printing has been instrumental for advancing the MNA functionality and the manufacturability. The high-resolution techniques such as the SLA, DLP, and 2PP are allowing the fabrication of the hollow, solid, and hybrid MNAs with the tunable geometry, lumen diameter, and the surface topography. These capabilities are surpassing the limitations from the conventional molding or the lithographic methods, providing a superior precision, good reproducibility, and also the design flexibility. The use of the polymeric materials like the PEGDA, PLA, PCL, and the GelMA has been further expanding the performance window from the MNAs, offering the biocompatibility, mechanical compliance, and the stimuli-responsive behavior that are essential for to achieve the proper skin integration and the adaptive functionality. Through the material and process optimization, the researchers have been demonstrating the MNA systems that can dissolve, swell, conduct electricity, or release the therapeutics on demand, all within a lightweight and wearable configuration.

The synergistic integration between the MNAs, flexible electronics, and the microfluidic systems has been propelling the development for the skin-conformal platforms that are capable for the multiplexed sensing and the closed-loop control. The advances in the wireless communication, power harvesting, and the embedded computing are now allowing these devices for to operate as autonomous “wearable labs,” continuously sampling the ISF, transmitting the biochemical data, and triggering the therapeutic responses without any external intervention. The notable demonstrations are including the glucose-sensing and insulin-releasing patches, the MNA vaccination platforms, and the self-powered drug-delivery systems. Such a convergence between the sensing, actuation, and the data analytics is marking a paradigm shift toward the real-time and patient-centric healthcare, where the continuous monitoring is informing the precise and adaptive interventions that are tailored for the individual needs.

Despite this rapid progress, several key challenges are still needing to be addressed before the widespread clinical translation can really occur. The manufacturing scalability is remaining as a major hurdle, while the 3D printing is allowing the unmatched customization, its throughput and cost efficiency are still lagging behind the traditional mass-production techniques. The standardized fabrication protocols, post-processing methods, and the quality control measures are essential for to ensure the reproducibility and the safety across the production batches. The regulatory uncertainty is also persisting because of the dual classification from the MNAs as both the medical devices and the drug-delivery systems. Establishing the unified frameworks that are encompassing the sterility, biocompatibility, mechanical reliability, and the long-term skin compatibility will be crucial for the commercial adoption. In addition, maintaining the stability from the biological recognition elements (e.g., enzymes, antibodies) and preventing the biofouling on the skin interface are remaining as technical challenges that must be overcome for to ensure the durable sensor performance.

Looking ahead, the field is being poised for to benefit from the emerging innovations that are happening at the interface between the materials science, bioelectronics, and the data intelligence. The integration from the artificial intelligence (AI) and the machine learning into the MNA-based wearables will be enabling the predictive analytics and the adaptive control for the therapeutic regimens. The self-powered systems that are using the piezoelectric, triboelectric, or the thermoelectric energy harvesters could eliminate the dependence on the external batteries, enhancing both the autonomy and the comfort. Furthermore, the advances in the bioprinting and the multimaterial 3D printing will be facilitating the fabrication for the hierarchical microneedle structures that are incorporating the living cells, hydrogels, and the conductive networks for the advanced sensing and the tissue-interactive applications. The cloud connectivity, cybersecurity, and the user-centric interface design will be further determining the success from these technologies in the real-world healthcare environments.

In summary, the polymeric 3D-printed MNA wearables are emerging as highly promising platforms that are uniting the precise microfabrication, intelligent materials, and the digital health analytics into a single system. They are bridging the gap between the invasive diagnostics and the noninvasive monitoring, offering a continuous access to the molecular information and the controlled therapeutic delivery with a minimal discomfort. The multidisciplinary collaboration among the engineers, material scientists, clinicians, and the regulatory bodies will be essential for to transform the current laboratory prototypes into the safe, manufacturable, and clinically validated products. With the sustained innovation and the standardization, the MNA-integrated wearables are being poised for to redefine the personalized healthcare, transitioning the medicine from a reactive treatment toward the proactive, autonomous, and data-driven well-being.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the academic and research community whose published work served as the foundation for this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2PP |

Two-Photon Polymerization |

| 3D |

Three-Dimensional |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| cGMP |

current Good Manufacturing Practice |

| CPC |

Cooperative Patent Classification |

| DLP |

Digital Light Processing |

| ECG |

Electrocardiography |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| EMG |

Electromyography |

| FDM |

Fused Deposition Modeling |

| GelMA |

Gelatin Methacryloyl |

| GOD |

Glucose Oxidase |

| ID |

Inner Diameter |

| ISF |

Interstitial Fluid |

| LCD |

Liquid Crystal Display |

| LED |

Light-Emitting Diode |

| MCBM |

Microneedle-based Continuous Biomarker Monitoring |

| MEMS |

Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems |

| MNA |

Microneedle Array |

| NFC |

Near-Field Communication |

| NIR |

Near-Infrared |

| OD |

Outer Diameter |

| PB |

Prussian Blue |

| PCL |

Poly(ε-caprolactone) |

| PEGDA |

Poly(ethylene glycol) Diacrylate |

| PK–PD |

Pharmacokinetics–Pharmacodynamics |

| PLA |

Poly(lactic acid) |

| PVA |

Poly(vinyl alcohol) |

| PVP |

Poly(vinylpyrrolidone) |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SLA |

Stereolithography |

| SOPL |

Static Optical Projection Lithography |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

References

- Luo, X.; Tan, H.; Wen, W. Recent Advances in Wearable Healthcare Devices: From Material to Application. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhinav, V.; Basu, P.; Verma, S.S.; Verma, J.; Das, A.; Kumari, S.; Yadav, P.R.; Kumar, V. Advancements in Wearable and Implantable BioMEMS Devices: Transforming Healthcare Through Technology. Micromachines 2025, 16, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, A.; De Decker, I.; Semey, S.; E. Y. Claes, K.; Blondeel, P.; Monstrey, S.; Dorpe, J.V.; Van Vlierberghe, S. Photo-crosslinkable polyester microneedles as sustained drug release systems toward hypertrophic scar treatment. Drug Deliv. 2024, 31, 2305818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M.Y.; Han, Y.; Lee, G.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Heo, Y.J.; Park, M. Development of an electrochemical biosensor for non-invasive cholesterol monitoring via microneedle-based interstitial fluid extraction. Talanta 2024, 280, 126771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, G.; Haick, H.; Zhang, M. Wearable Clinic: From Microneedle-Based Sensors to Next-Generation Healthcare Platforms. Small 2023, 19, 2207539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, E.; Balmert, S.C.; Carey, C.D.; Erdos, G.; Falo Jr, L.D. Emerging skin-targeted drug delivery strategies to engineer immunity: A focus on infectious diseases. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 18, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chatzilakou, E.; Pan, Z.; Traverso, G.; Yetisen, A.K. Microneedle Sensors for Point-of-Care Diagnostics. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2306560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lei, Y. Microneedle-based glucose monitoring: a review from sampling methods to wearable biosensors. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 5727–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.N.; Jain, S.N.; Patil, S.N.; Bhise, Y.V. Microneedle-based wearable sensors: a new frontier in real-time biomarker monitoring. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2025, 0, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, N. Revolutionizing biosensing with wearable microneedle patches: innovations and applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 5264–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbariamin, D.; Samandari, M.; Ghelich, P.; Shahbazmohamadi, S.; Schmidt, T.A.; Chen, Y.; Tamayol, A. Cleanroom-Free Fabrication of Microneedles for Multimodal Drug Delivery. Small 2023, 19, 2207131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwersch, P.; Evens, T.; Van Bael, A.; Castagne, S. Design, fabrication, and penetration assessment of polymeric hollow microneedles with different geometries. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.G.; Lay, E.; Jungwirth, U.; Varenko, V.; Gill, H.S.; Estrela, P.; Leese, H.S. 3D-Printed Hollow Microneedle-Lateral Flow Devices for Rapid Blood-Free Detection of C-Reactive Protein and Procalcitonin. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2300259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Colton, A.; Wen, Z.; Xu, X.; Erdi, M.; Jones, A.; Kofinas, P.; Tubaldi, E.; Walczak, P.; Janowski, M.; et al. 3D-Printed Microinjection Needle Arrays via a Hybrid DLP-Direct Laser Writing Strategy. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monou, P.K.; Andriotis, E.G.; Tsongas, K.; Tzimtzimis, E.K.; Katsamenis, O.L.; Tzetzis, D.; Anastasiadou, P.; Ritzoulis, C.; Vizirianakis, I.S.; Andreadis, D.; et al. Fabrication of 3D Printed Hollow Microneedles by Digital Light Processing for the Buccal Delivery of Actives. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 5072–5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wan, S.; Suza Pronay, T.; Yang, X.; Gao, B.; Teck Lim, C. Toward next-generation smart medical care wearables: where microfluidics meet microneedles. Nanoscale Horiz. 2025, 10, 1815–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, X.; Li, L.; Wu, S.; Yuan, X.; Cheng, H.; Jiang, X.; Gou, M. 3D-printed microneedle arrays for drug delivery. J. Controlled Release 2022, 350, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.M.; Lim, Y.J.L.; Tay, J.T.; Cheng, H.M.; Tey, H.L.; Liang, K. Design and fabrication of customizable microneedles enabled by 3D printing for biomedical applications. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 32, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, X.; Yuan, X.; Wu, S.; Li, L.; Jiang, X.; Li, B.; Jiang, X.; Gou, M. Fast Customization of Hollow Microneedle Patches for Insulin Delivery. Int. J. Bioprinting 2022, 8, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, A.; Baliga, V.; Shenoy, R.; Dessai, A.D.; Nayak, U.Y. 3D printed microneedles: revamping transdermal drug delivery systems. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñas-Núñez, S.J.; Rai, R.; Criado-Gonzalez, M. Key Trends and Insights in Smart Polymeric Skin Wearable Patches. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, n/a, 2500823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.E.A.-R.; Kohler, S.; Bartzsch, N.; Beuschlein, F.; Guentner, A.T. 3D printing by two-photon polymerization of hollow microneedles for interstitial fluid extraction 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kawre, S.; Suryavanshi, P.; Lalchandani, D.S.; Deka, M.K.; Kumar Porwal, P.; Kaity, S.; Roy, S.; Banerjee, S. Bioinspired labrum-shaped stereolithography (SLA) assisted 3D printed hollow microneedles (HMNs) for effectual delivery of ceftriaxone sodium. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 204, 112702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Nail, A.; Meng, D.; Zhu, L.; Guo, X.; Li, C.; Li, H.-J. Recent progress in the 3D printing of microneedle patches for biomedical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 668, 124995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekeroglu, M.O.; Pekgor, M.; Algin, A.; Toros, T.; Serin, E.; Uzun, M.; Cerit, G.; Onat, T.; Ermis, S.A. Transdisciplinary Innovations in Athlete Health: 3D-Printable Wearable Sensors for Health Monitoring and Sports Psychology. Sensors 2025, 25, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]