1. Introduction

The advancement of digital learning systems has become a strategic priority in Indonesia’s higher education landscape. The Ministry of Education and Culture launched the Integrated and Open Online Learning System (SPADA) in 2018 as an evolution of the earlier Indonesia Open and Integrated Online Learning Program (PDITT), aiming to enhance the quality and equity of education across the archipelago. SPADA reflects the government’s commitment to aligning higher education with the demands of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which emphasizes digital fluency, connectivity, and learner-centered approaches. [

23,

24,

25,

26]

The advancement of digital learning systems has emerged as a pivotal force in reshaping Indonesia’s higher education landscape. This transformation is driven by the nation’s aspiration to democratize access to quality education while simultaneously responding to the accelerating digitalization of global knowledge ecosystems. Within this context, the Ministry of Education and Culture’s establishment of the Integrated and Open Online Learning System (SPADA) represents a deliberate and forward-looking policy intervention. By leveraging digital platforms, SPADA seeks to transcend geographical constraints and ensure that students from diverse regions—urban centers as well as remote islands—can engage with high-quality academic content and pedagogical resources. [

15]

Since its inception in 2018, SPADA has evolved as a critical infrastructure supporting the modernization of higher education in Indonesia. It extends the foundational objectives of its predecessor, the Indonesia Open and Integrated Online Learning Program (PDITT), which laid the groundwork for online education integration among universities. SPADA’s design prioritizes inclusivity and inter-university collaboration, facilitating credit transfers, cross-institutional course enrollment, and shared academic resources. Through this networked model, universities can collaboratively enhance the quality of instruction while fostering a national learning community grounded in openness and mutual support. [

1,

2]

The implementation of SPADA also signifies Indonesia’s strategic adaptation to the imperatives of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. As automation, artificial intelligence, and data-driven systems reshape employment and learning paradigms, digital literacy has become a foundational competency for both educators and learners. SPADA’s pedagogical model emphasizes learner autonomy, digital collaboration, and critical engagement with technology-mediated content. Such features align with the global transition toward hybrid and personalized learning systems that prioritize flexibility, creativity, and problem-solving. [

1,

3]

Moreover, SPADA has positioned itself as a catalyst for pedagogical innovation and faculty development across Indonesian universities. The platform encourages educators to redesign traditional classroom instruction into interactive, multimedia-based modules that integrate videos, simulations, and real-world projects. This shift not only enhances student engagement but also cultivates instructional practices that are responsive to diverse learning styles. Consequently, SPADA fosters a culture of continuous improvement among lecturers, emphasizing reflective teaching and digital competency as core professional attributes. [

2,

3]

From an institutional perspective, SPADA strengthens academic collaboration and resource efficiency within the national higher education system. Universities can co-develop courses, share best practices, and avoid redundant resource allocation by utilizing the centralized platform. This approach supports cost-effective expansion of course offerings while ensuring consistency in academic standards. Furthermore, SPADA’s governance structure promotes accountability, data transparency, and quality assurance through centralized monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. [

1]

Despite these achievements, the integration of SPADA also presents ongoing challenges related to infrastructure disparities, digital literacy gaps, and institutional readiness. Many universities, particularly in rural and underdeveloped areas, face limitations in bandwidth, learning management systems, and technical support. Additionally, disparities in digital proficiency among educators and students can hinder optimal platform utilization. Addressing these barriers requires sustained investment, policy alignment, and professional development programs that equip stakeholders with the necessary digital competencies. [

2,

3,

4,

5]

In a broader sense, SPADA reflects Indonesia’s commitment to building a resilient and future-oriented higher education ecosystem. By embedding digital transformation into the national education strategy, the government underscores the importance of lifelong learning and adaptability in an era characterized by rapid technological change. As SPADA continues to mature, its success will depend not only on technological infrastructure but also on cultural and pedagogical shifts that embrace innovation, inclusivity, and collaboration as the hallmarks of Indonesia’s educational progress. [

1,

2]

Effective implementation of online learning requires appropriate instructional resources. Learning materials—defined as collections of educational resources that support both instructors and learners [

3,

4]—can take various forms, including printed modules, interactive videos, and web-based content. In the era of the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence, integrating technology into learning materials is not only beneficial but necessary. Internet-based resources can stimulate student engagement, foster critical thinking, encourage collaboration, and improve problem-solving skills [

5,

6]. Empirical studies further confirm that well-designed digital materials enhance mathematical reasoning, communication, and problem-solving abilities [

7,

8].

Effective implementation of online learning hinges on the availability of well-structured and pedagogically sound instructional resources. In higher education, learning materials serve as the backbone of instructional design, bridging the gap between teaching objectives and learner outcomes. According to Hamdani [

9,

10], learning materials encompass a collection of educational resources designed to facilitate interaction, comprehension, and skill development among both instructors and students. These materials may take diverse formats—ranging from printed modules and multimedia content to web-based applications—each contributing uniquely to the teaching and learning process. [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]

The digital transformation in education, accelerated by the proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI), has redefined the conception and delivery of learning materials. In this era, the integration of technology into instructional resources is no longer optional but a strategic necessity. Digitally enhanced materials enable dynamic content delivery, adaptive feedback, and real-time interaction, all of which contribute to more engaging and personalized learning experiences. When properly designed, such resources can help students move beyond rote memorization toward deeper cognitive engagement and problem-solving proficiency. [

11]

Furthermore, internet-based learning materials have proven effective in fostering essential twenty-first-century competencies such as critical thinking, creativity, and collaboration. [

12] and [

13] emphasize that interactive digital environments stimulate student participation and curiosity by transforming passive learning into active exploration. Through the use of online simulations, digital storytelling, and collaborative platforms, students can engage in experiential learning that mirrors real-world problem contexts. This active engagement not only enhances conceptual understanding but also strengthens students’ ability to apply knowledge in authentic situations. [

14]

Empirical evidence consistently demonstrates the pedagogical value of integrating digital materials into mathematics education. Studies by [

15] and Imswatama and [

16] reveal that digital instructional designs contribute to significant improvements in students’ mathematical reasoning, communication, and problem-solving skills. These findings suggest that the effectiveness of digital learning environments depends largely on the coherence between technological tools and pedagogical strategies. When educators align digital resources with clear learning objectives and assessment criteria, technology becomes an enabler of higher-order thinking rather than a mere delivery mechanism. [

17]

The flexibility of digital learning materials also enhances accessibility and inclusivity within the educational system. Students from different geographic regions or socio-economic backgrounds can access quality resources through online platforms, reducing disparities in learning opportunities. This democratization of access aligns with global education goals and national initiatives aimed at fostering equitable and lifelong learning. Additionally, digital materials can be continually updated to reflect current developments, ensuring that learners engage with relevant and contextually meaningful content. [

18]

However, the successful adoption of technology-based learning materials requires more than mere availability of digital tools. It demands pedagogical innovation, institutional support, and digital literacy among educators and students alike. Without adequate training and systematic integration, even the most sophisticated materials may fail to achieve their intended outcomes. Therefore, effective implementation should involve capacity-building programs, ongoing evaluation, and collaboration between instructional designers, educators, and policymakers to ensure alignment with curriculum standards and learner needs. [

19]

The evolution of instructional materials from traditional to digital formats represents a transformative step in redefining educational quality and relevance. By leveraging the affordances of IoT and AI, educators can design learning experiences that are interactive, data-informed, and learner-centered. Such an approach not only enhances cognitive and metacognitive engagement but also prepares students to thrive in complex, technology-driven environments. Ultimately, integrating digital learning materials is a key pathway toward achieving adaptive, inclusive, and future-ready education systems. [

20]

However, developing effective online materials for mathematics remains challenging. Many educators perceive mathematics as difficult to teach remotely due to its abstract nature and the need for dynamic visualization. GeoGebra—a dynamic mathematics software—offers a promising solution. Recognized for its capacity to support visual and interactive learning across all mathematical proficiency levels [

26], GeoGebra has been shown to improve students’ understanding of complex topics such as integral calculus and graph sketching [

21]. Yet, most existing studies focus on its use in face-to-face settings, with limited integration into self-contained, interactive online learning materials.

Despite the rapid expansion of digital education, developing effective online instructional materials for mathematics remains a persistent challenge. Mathematics, by its very nature, involves abstract reasoning, symbolic representation, and logical structures that often require step-by-step explanation and visual demonstration. These characteristics make it difficult for educators to translate conventional classroom interactions into engaging online experiences. Many instructors continue to perceive mathematics as a discipline that demands direct teacher mediation, immediate feedback, and dynamic visualization—elements that are not easily replicated in asynchronous learning environments. Consequently, the pedagogical design of online mathematics materials must overcome not only technological barriers but also conceptual and cognitive complexities inherent in mathematical learning. [

22]

One promising avenue to address these challenges lies in the integration of dynamic mathematics software such as GeoGebra. As a multifunctional platform that combines geometry, algebra, calculus, and statistics, GeoGebra offers a unique capability to visualize abstract mathematical concepts through interactive simulations and manipulable representations. [

23,

24,

25,

26] highlights that GeoGebra facilitates active learning and conceptual understanding across all levels of mathematical proficiency, transforming abstract symbols into dynamic visual objects that students can explore intuitively. This feature aligns with constructivist learning theories, which emphasize that knowledge is best acquired through exploration, manipulation, and reflection rather than passive reception. [

25]

Empirical evidence further reinforces the pedagogical value of GeoGebra in enhancing mathematical comprehension. Studies by [

23] and [

24] as well as [

26] demonstrate that students who engage with GeoGebra-assisted instruction exhibit improved understanding of complex topics such as integral calculus, graph sketching, and function analysis. These findings underscore GeoGebra’s potential to bridge the gap between abstract formalism and visual intuition—an essential factor in mathematics education. The software’s capacity for real-time feedback and dynamic manipulation of variables allows learners to observe the immediate impact of parameter changes, thereby deepening conceptual insight and promoting higher-order thinking skills. [

21]

Nevertheless, while GeoGebra has proven effective in conventional, face-to-face instructional contexts, its potential remains underexplored in online and self-directed learning environments. Most existing implementations treat GeoGebra as a classroom demonstration tool rather than as an integral component of autonomous digital learning materials. This limited scope constrains opportunities for students to engage in independent inquiry and self-paced exploration—capabilities that define the essence of online education. To maximize its impact, GeoGebra must be embedded within interactive digital ecosystems that combine multimedia instruction, problem-based learning tasks, and automated assessment tools. [

21]

The transition from classroom-based use to fully online integration presents several pedagogical and technical challenges. Designing self-contained digital materials requires not only proficiency in GeoGebra but also a deep understanding of instructional design principles, learner interaction patterns, and cognitive load management. Educators must ensure that visual and interactive elements complement rather than overwhelm conceptual understanding. Moreover, the online deployment of GeoGebra-based materials necessitates compatibility with learning management systems (LMS), mobile devices, and bandwidth constraints, particularly in developing contexts where technological infrastructure varies widely. [

22]

Equally important is the need to foster digital pedagogical competence among educators. Many mathematics instructors possess strong subject-matter expertise but limited experience in creating interactive online modules or leveraging data analytics to monitor student engagement. Professional development programs should therefore focus on equipping teachers with the skills to design, evaluate, and refine GeoGebra-integrated online resources. Through such initiatives, educators can transition from being content transmitters to facilitators of inquiry-driven, technology-enhanced learning experiences. [

23]

In sum, while GeoGebra offers a powerful framework for visual and interactive mathematics learning, its effective utilization in online education requires a paradigm shift. Rather than treating technology as an auxiliary aid, instructional designers must conceptualize it as a core component of digital pedagogy—one that redefines how learners construct, visualize, and internalize mathematical knowledge. By embedding GeoGebra within well-structured online learning environments, educators can unlock new possibilities for engagement, accessibility, and conceptual mastery in mathematics education. [

23,

24,

25,

26]

This paper addresses this gap by embedding GeoGebra directly into online Calculus learning materials, enabling real-time interaction and autonomous learning. The integration aims to transform static digital content into an active, exploratory learning environment aligned with contemporary educational demands.

2. Method

This study employed the Research and Development (R&D) methodology to design and evaluate online-based Calculus learning materials. R&D is a systematic approach aimed at producing and validating educational products that are both practical and effective for implementation [

21]. The development process followed the Plomp model, a widely recognized R&D framework in educational design that consists of three main phases: (1) preliminary research, (2) prototyping, and (3) assessment [

21,

23].

In the preliminary phase, needs analysis and literature review were conducted to identify key challenges in online Calculus instruction and to establish design principles. The prototyping phase involved the creation of the digital learning materials, integrating interactive elements—particularly GeoGebra applets—to support visualization and conceptual understanding of Calculus topics. The final assessment phase focused on evaluating the practicality and effectiveness of the developed materials. [

22]

Practicality was measured through a questionnaire administered to 20 students from the Mathematics Education Study Program at Universitas Islam Negeri Syekh Ali Hasan Ahmad Addary Padangsidimpuan, North Sumatra, Indonesia, who had completed the Basic Calculus course. Effectiveness was assessed using a set of basic Calculus test items aligned with the material’s learning objectives. The data were analyzed quantitatively to determine whether the materials met the criteria for practicality (user-friendliness, accessibility, and relevance) and effectiveness (improvement in student understanding and performance) [

21]. This approach ensured that the final product was both educationally sound and suitable for autonomous online learning environments.

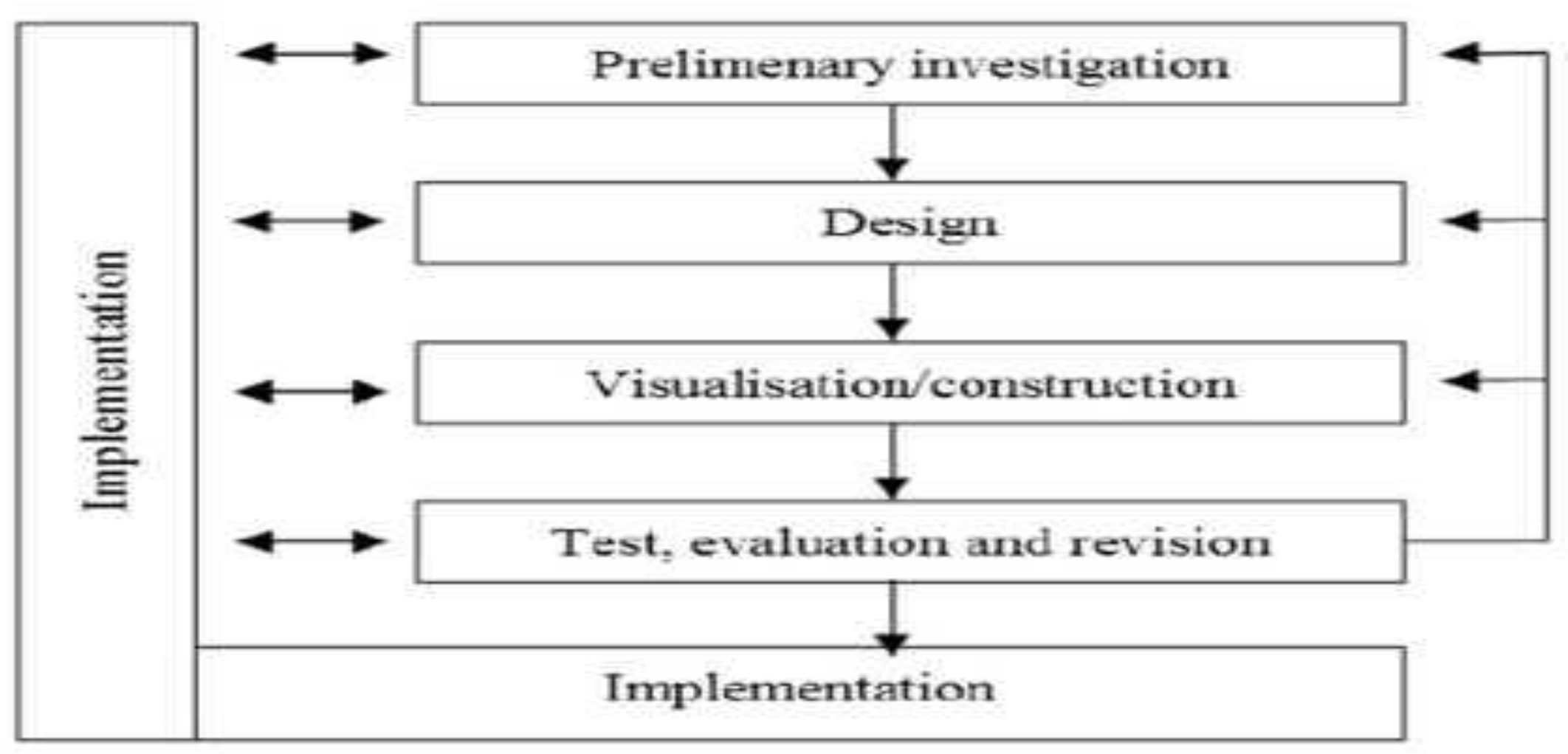

Figure 1.

Plomp’s Research and Development (R&D) Research Design.

Figure 1.

Plomp’s Research and Development (R&D) Research Design.

This figure illustrates the iterative, cyclical framework of Plomp’s R&D model, comprising five key phases:

Preliminary Investigation: The initial stage involves identifying educational needs, reviewing existing literature, analyzing curriculum standards, and understanding learner characteristics to inform the development process.

Design: Based on insights from the preliminary phase, instructional strategies, content structure, and technological integration (e.g., GeoGebra) are planned to create a functional blueprint for the learning material.

Visualization/Construction: The prototype is developed and assembled according to the design specifications. This includes embedding interactive elements, formatting digital content, and ensuring usability across platforms.

Test, Evaluation, and Revision: The prototype undergoes formative evaluation through expert validation, practicality testing (via student questionnaires), and effectiveness assessment (using pre- and post-tests or performance tasks). Feedback is systematically analyzed to refine the product.

Implementation: After revisions, the final version of the online Calculus learning material is deployed for broader use in educational settings.

The bidirectional arrows indicate that feedback from each phase may lead to revisiting earlier stages, ensuring continuous improvement and alignment with pedagogical goals. This structured yet flexible approach supports the creation of high-quality, empirically validated educational resources suitable for digital learning environments.

Practicality Evaluation

Practicality refers to the extent to which a developed educational product can be effectively used by its intended users in real learning contexts. According to [

1,

2] and [

3], practicality is assessed based on the ease of use and clarity of presentation from the user’s perspective. In this study, the practicality of the online Calculus learning materials was evaluated through five key indicators: effectiveness, creativity, efficiency, interactivity, and attractiveness. [

4]

The instrument employed was a structured attitude-scale questionnaire comprising 56 closed-ended statements distributed across the five aforementioned indicators. Additionally, two open-ended questions were included to gather qualitative feedback regarding the strengths, weaknesses, and suggestions for improvement of the developed materials. The evaluation involved 20 undergraduate students from the Mathematics Education Study Program who had previously completed the Basic Calculus course. Their responses provided both quantitative and qualitative data to determine the overall practicality of the learning materials, ensuring that the final product is user-friendly, engaging, and suitable for autonomous online learning environments. [

5]

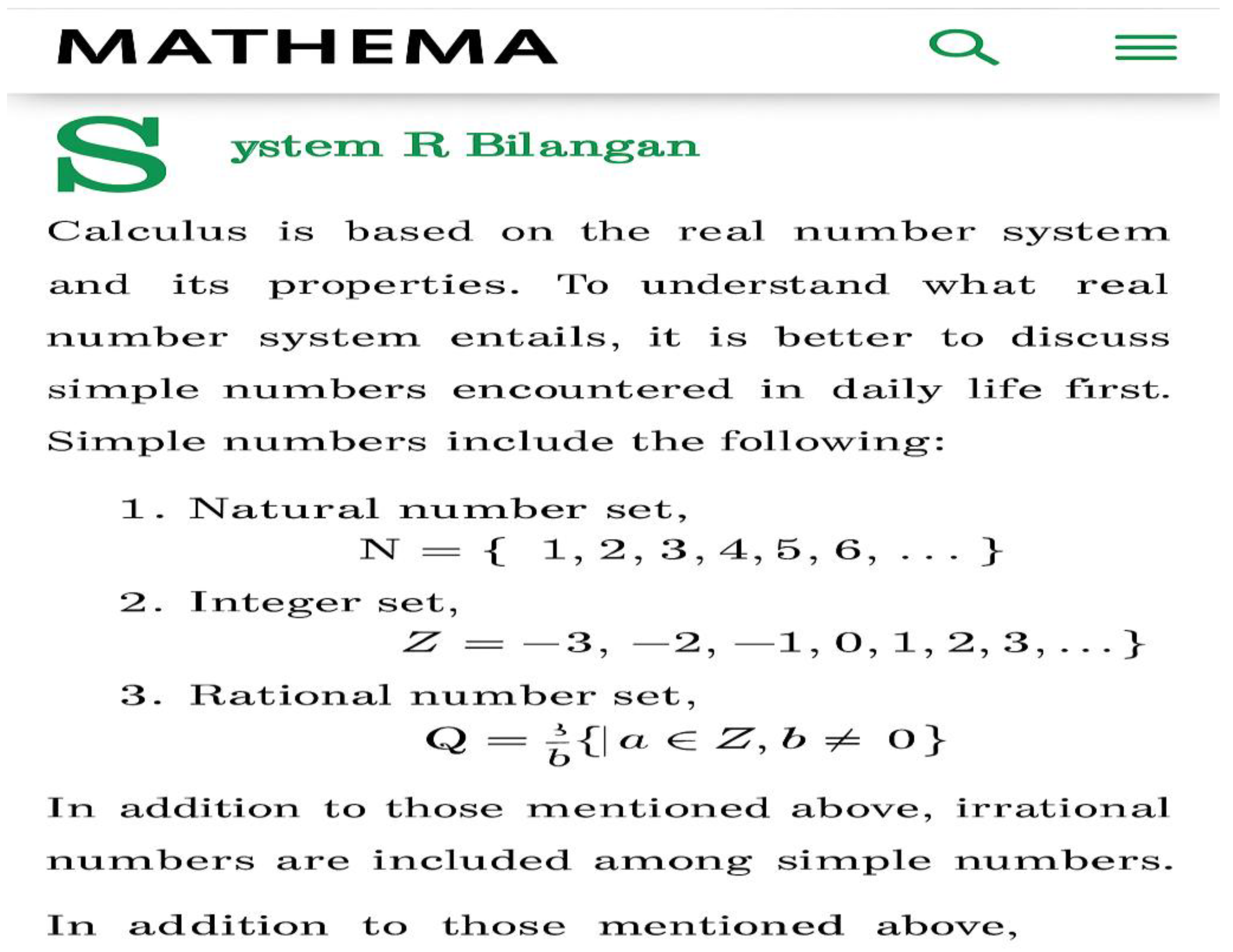

Effectiveness Evaluation

The effectiveness evaluation aimed to determine the extent to which the online Calculus learning materials influenced students’ conceptual understanding of basic Calculus topics. Specifically, the assessment focused on core content areas including real numbers, functions, and their graphical representations. The same group of 20 undergraduate students from the Mathematics Education Study Program—who had completed the Basic Calculus course—participated in this phase. However, a different instrument was employed: a set of open-ended (essay-type) test items designed to elicit in-depth responses that reflect comprehension and reasoning. [

21,

25]

To ensure objectivity and consistency in scoring, a detailed assessment rubric was developed and applied. This rubric provided clear criteria for evaluating the accuracy, completeness, and logical coherence of students’ answers, thereby minimizing subjective bias in the grading process. [

6,

7]

The learning materials are considered practical and effective if the evaluation results fall at least within the “Good” category.

Prior to data analysis, the validity of each item in the practicality questionnaire was examined. Item validity was assessed using an independent-samples

t-test approach by comparing the calculated

t-value (

t<sub>hitung</sub>) with the critical

t-value (

t<sub>tabel</sub>) at α = 0.05 and degrees of freedom

df = N − 2. [

21]

The validation process began by computing the Pearson product–moment correlation coefficient (r

xy) between the score of each individual item ( X) and the total score across all items (Y ), using the formula:

where:

N = number of respondents

∑X,∑Y = sum of scores for the item and total scores, respectively

∑X2,∑Y2= sum of squared scores

The corresponding

t-statistic was then calculated as:

An item was deemed valid if tcount > ttable; otherwise, it was excluded from further analysis. This rigorous validation ensured that only reliable and relevant items contributed to the final practicality assessment.

Data Processing and Analysis

Quantitative data from both the practicality questionnaire and the effectiveness test were analyzed using established evaluation criteria adapted from [

8] as cited in [

9,

10]. As shown in

Table 1, these criteria define threshold values for categorizing the feasibility of learning materials into levels such as “very good,” “good,” “sufficient,” “poor,” or “very poor.” Practicality scores were interpreted based on the mean response values from the Likert-scale questionnaire, while effectiveness was determined by the average percentage score achieved by students on the Calculus test. This dual-method approach enabled a comprehensive validation of the developed materials in terms of both usability and learning impact. [

11]

Table 1.

Criteria for Assessing the Feasibility of Learning Materials.

Table 1.

Criteria for Assessing the Feasibility of Learning Materials.

| Category |

Score Interval |

Interpretation |

| A |

X>Xi+1.8sbi

|

Very Good |

| B |

Xi+0.6sbi<X<Xi+1.8sbi

|

Good |

| C |

Xi−0.6sbi<X<Xi+0.6sbi

|

Sufficient |

| D |

Xi−1.8sbi<X<Xi−0.6sbi

|

Poor |

| E |

X<Xi−1.8sbi

|

Very Poor |

Table 2.

Criteria for Assessing, Data Processing and Analysis.

Table 2.

Criteria for Assessing, Data Processing and Analysis.

| SCORE RANGE |

FEASIBILITY CATEGORY |

| 3.26 – 4.00 |

Very Good |

| 2.51 – 3.25 |

Good |

| 1.76 – 2.50 |

Sufficient |

| 1.00 – 1.75 |

Poor |

4. Discussion

The practicality and effectiveness assessments demonstrate that the developed online calculus teaching material is both practical and effective for use by undergraduate students in learning Basic Calculus. As shown in Table 8, the highest practicality rating was for the

engaging indicator (3.43), while the lowest was for

creativity (3.29). In this context, “creativity” refers to the material’s capacity to foster learners’ creative thinking after engaging with calculus content. This suggests a need for improvement in content design to better stimulate creativity. [

26]

The practicality and effectiveness assessments of the developed online calculus teaching material provide substantial evidence of its suitability for use in undergraduate learning contexts, particularly in the Basic Calculus course. The findings confirm that the material meets essential pedagogical and usability standards, aligning with the goals of enhancing accessibility, interactivity, and conceptual understanding in digital mathematics education. These results support the view that technology-mediated learning resources can effectively complement traditional instructional methods in fostering students’ engagement and comprehension. [

1,

2,

3,

4]

The overall practicality score indicates that students perceive the material as user-friendly, intuitive, and compatible with their learning needs. The integration of multimedia elements, interactive visualizations, and structured learning sequences appears to contribute significantly to this positive reception. In digital learning environments, such usability aspects are critical, as they influence learners’ motivation, cognitive engagement, and sustained interaction with mathematical content. Thus, the practicality dimension reflects the material’s successful adaptation to contemporary learning behaviors and technological literacy among undergraduate students.

Among the assessed indicators, the highest rating was recorded for the engaging component (3.43), suggesting that learners found the platform stimulating and enjoyable to use. Engagement in this context pertains not only to the visual or aesthetic appeal but also to the cognitive stimulation arising from interactive tasks and exploratory exercises. This high engagement score underscores the potential of online platforms to transform abstract mathematical concepts into more relatable and tangible learning experiences. The presence of such engagement fosters persistence, which is crucial in mastering complex calculus topics such as limits, differentiation, and integration. [

20]

In contrast, the lowest score was assigned to the creativity indicator (3.29). Although still within a satisfactory range, this result highlights an area for pedagogical enhancement. Creativity in mathematics learning involves the ability to explore alternative solution strategies, generate original ideas, and establish connections across different concepts. The relatively lower creativity score suggests that the current design of the material may emphasize procedural fluency over open-ended problem-solving or discovery-based learning. Therefore, future iterations should aim to integrate features that encourage creative exploration, such as problem-based tasks, inquiry-driven activities, and adaptive feedback mechanisms. [

21]

The gap between engagement and creativity scores reveals an interesting pedagogical dynamic. While digital learning materials can easily capture attention through interactivity and multimedia design, promoting creativity demands deeper cognitive engagement and opportunities for learners to construct knowledge independently. Enhancing creativity within online calculus instruction thus requires embedding more exploratory learning opportunities where students can experiment with concepts, test hypotheses, and reflect on outcomes. Such revisions would align the material more closely with constructivist and inquiry-based learning paradigms. [

22]

From a design perspective, the findings imply that content developers should place greater emphasis on scaffolding activities that cultivate higher-order thinking skills. For example, integrating dynamic graphing tools like GeoGebra or Desmos within the modules could enable students to visualize mathematical relationships more creatively. Moreover, incorporating open-ended questions and reflective prompts could encourage learners to analyze and generalize results beyond routine problem-solving. These modifications would not only enhance creativity but also strengthen conceptual understanding and critical reasoning in calculus. [

23]

In terms of effectiveness, the results demonstrate that the online teaching material successfully supports learning outcomes in Basic Calculus. Students were able to comprehend fundamental concepts more effectively through guided simulations, visual representations, and self-paced exercises. This outcome validates the instructional model underpinning the material, which combines clarity of explanation, interactivity, and formative assessment. Such evidence reinforces the broader argument that well-designed digital resources can achieve comparable or even superior learning outcomes relative to conventional teaching methods. [

24]

The practical implications of these findings extend to higher education institutions seeking to integrate digital learning innovations into mathematics curricula. The demonstrated practicality and effectiveness suggest that such materials can be implemented at scale, provided that instructors receive adequate training in their pedagogical integration. Additionally, the emphasis on continuous improvement—especially in fostering creativity—should guide future development cycles and institutional quality assurance processes. [

25]

Theoretically, this study contributes to the growing body of research on technology-enhanced mathematics education. It affirms that digital teaching materials, when designed based on sound pedagogical principles, can effectively balance cognitive challenge with learner engagement. Furthermore, the differentiated outcomes across indicators underscore the multidimensional nature of digital learning evaluation, emphasizing that usability, engagement, and creativity are distinct yet interrelated constructs. [

26]

The online calculus teaching material exhibits strong practical and effective attributes for undergraduate use, though further refinement is needed to elevate its creative potential. The results emphasize that digital learning innovations should not only make content accessible and engaging but also cultivate creative and analytical thinking. Future developments should thus prioritize the integration of exploratory and inquiry-based features to transform calculus learning into a more dynamic, imaginative, and cognitively enriching experience. [

1,

2,

3,

4]

To enhance creativity, the integration of the AIR (Auditory, Intellectually, Repetition) learning model is recommended [

5]. This model emphasizes listening, speaking, argumentation, presentation, and responsive dialogue, alongside higher-order cognitive skills such as reasoning, problem-solving, identification, and creation. Furthermore, embedding curiosity-driven tasks can encourage deeper exploration of calculus concepts. Cross-disciplinary integration—particularly with STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields—can also enrich creative engagement. [

6]

To enhance the creative dimension of online calculus learning, integrating the AIR (Auditory, Intellectually, Repetition) learning model is strongly recommended [

7]. The AIR model provides a structured yet flexible framework that emphasizes learning through auditory engagement, intellectual processing, and continuous reinforcement. By incorporating activities that involve listening, articulating ideas, and revisiting key concepts, the model fosters both understanding and retention. Within an online calculus environment, this approach can be operationalized through audio explanations, interactive discussions, and iterative practice cycles that encourage students to engage deeply with abstract mathematical ideas. [

8]

The auditory component of the AIR model can play a pivotal role in promoting creative engagement. When learners are exposed to multiple representations of mathematical explanations—through narration, guided problem-solving, or peer discussions—they develop a more nuanced understanding of concepts. Listening activities, such as narrated problem walkthroughs or instructor commentaries, can help students internalize procedural and conceptual knowledge simultaneously. This auditory reinforcement is especially beneficial for abstract topics in calculus, such as limits and derivatives, which require conceptual visualization supported by verbal reasoning. [

9]

The intellectual component emphasizes cognitive engagement beyond memorization, focusing on reasoning, problem-solving, and argumentation. Through guided questioning, analytical reflection, and conceptual challenges, learners are encouraged to construct and articulate their understanding independently. Incorporating this intellectual focus into the digital material can be achieved through problem-based tasks that require students to explain their reasoning or justify their solutions using multiple approaches. Such cognitive engagement enhances not only understanding but also creative flexibility in approaching mathematical problems. [

10]

Repetition, as the third pillar of the AIR model, serves to consolidate learning and facilitate the transition from surface to deep understanding. Repetition in this context does not imply rote learning, but rather iterative engagement with varied problem types and contexts. In online calculus modules, this can be implemented through adaptive quizzes, scaffolded exercises, and reflective reviews that prompt students to revisit prior concepts in new applications. Through this process, learners develop automaticity in basic procedures while maintaining room for creative application and synthesis of knowledge. [

12]

An additional strategy for stimulating creativity is embedding curiosity-driven tasks that motivate learners to explore beyond standard problem sets. Curiosity acts as a cognitive catalyst that drives learners to seek patterns, question assumptions, and investigate relationships between mathematical ideas. Online environments provide rich opportunities for implementing such exploratory activities—such as interactive simulations, inquiry-based projects, or “what-if” analytical scenarios—that invite students to manipulate parameters, observe outcomes, and draw conclusions through discovery. These tasks align well with the intellectual and repetitive dimensions of the AIR model, reinforcing creative engagement through exploration. [

13]

Furthermore, the integration of cross-disciplinary contexts, particularly within STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) domains, can enrich the creative potential of calculus learning [

14]. By situating calculus problems in real-world scientific or engineering applications, students perceive mathematics not as an isolated discipline but as an active tool for problem-solving across fields. For instance, modeling motion in physics, analyzing growth in biology, or optimizing design in engineering can provide authentic, creativity-inducing learning experiences. This interdisciplinary perspective encourages students to transfer knowledge flexibly and innovatively. [

15]

Within this cross-disciplinary approach, collaborative projects can also enhance creativity by engaging learners in shared inquiry and peer feedback. Online platforms can facilitate such collaboration through discussion forums, group problem-solving tasks, and digital presentations. These activities encourage students to articulate their ideas, challenge one another’s reasoning, and synthesize diverse perspectives—all of which are essential components of creative mathematical thinking. Integrating the AIR model into such collaborative frameworks could amplify both engagement and higher-order cognition. [

16]

In addition, incorporating reflective components within the learning sequence can help students become more aware of their creative processes. Reflective journals or digital portfolios, for example, allow learners to track their reasoning evolution, recognize errors, and identify alternative solution paths. Reflection thus bridges the auditory, intellectual, and repetitive elements of the AIR model by enabling students to internalize and reconstruct their understanding actively. [

17]

Overall, applying the AIR learning model in conjunction with curiosity-driven and interdisciplinary strategies represents a comprehensive framework for enhancing creativity in online calculus instruction. This integrated approach aligns with constructivist learning principles, positioning students as active participants in knowledge construction rather than passive recipients of information. Through auditory engagement, intellectual exploration, and repeated practice, learners are guided toward deeper understanding and innovative thinking. [

18]

Enhancing creativity in online calculus education requires deliberate instructional design that balances structure with flexibility. The AIR model, supported by curiosity-based learning and STEM integration, offers a theoretically grounded and practically feasible strategy for achieving this goal. By fostering interaction, reasoning, and exploration, such an approach transforms calculus learning into an intellectually stimulating and creatively empowering experience, preparing students not only to master mathematical techniques but also to apply them innovatively across disciplines. [

19]

Regarding effectiveness, while the overall mean score (72.75) is satisfactory, two respondents scored below 50 (40 and 60), indicating persistent learning gaps. A thorough review of the embedded instructional strategies is therefore warranted. One promising approach is the incorporation of Realistic Mathematics Education (RME), which connects mathematical concepts to real-life contexts and has been shown to improve mathematical reasoning and communication [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Key design principles for RME-based materials include:

Relevant and engaging illustrations;

Language aligned with learners’ daily experiences and cultural context;

Inclusion of collaborative tasks, discussions, practice problems, and project-based assessments; and

Consideration of learners’ character, mental development, and ethical values.

Additionally, the strategic expansion of GeoGebra integration could further enhance effectiveness. GeoGebra—a dynamic mathematics software—enables accurate, efficient, and interactive visualization of abstract mathematical objects, particularly graphical representations of functions [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Although the current material already incorporates GeoGebra for real-time graph simulation, its placement and frequency of use should be optimized to maximize learning outcomes.

5. Conclusion

The developed online calculus teaching material, supported by GeoGebra, integrates multiple digital tools and platforms to facilitate real-time interaction and enhance students’ understanding of basic calculus concepts. These include GeoGebra for dynamic visualization, YouTube videos for explanatory content, online LaTeX for mathematical notation, and real-time online assessments such as quizzes and examinations.

Based on practitioner evaluations assessing both practicality and effectiveness, the material was rated as “Good” in both dimensions. This indicates that the teaching material is not only practical in terms of usability and design but also effective in supporting learning outcomes. Consequently, it is deemed suitable for implementation as an alternative digital resource for teaching and learning basic calculus at the undergraduate level.

However, the evaluation also identified areas for improvement. Specifically, the content should be further enriched to better foster learner creativity, and the instructional approach should incorporate principles of Realistic Mathematics Education (RME) to strengthen conceptual understanding through real-world contexts.

Given its validated quality and functionality, this teaching material is recommended for use by educators, students, and other stakeholders involved in calculus instruction. Furthermore, constructive feedback and suggestions from users are encouraged to support continuous refinement and optimization of the material for future implementations.

The online calculus teaching material, supported by GeoGebra and supplemented with YouTube videos, online assessments, and LaTeX-based mathematical notation, has been validated as practical and effective. Its development responds to the growing demand for high-quality digital learning resources, especially in the post-pandemic educational landscape. This material offers a viable alternative for delivering engaging, interactive, and conceptually robust calculus instruction in online settings and is recommended for broader implementation in undergraduate mathematics education.