Introduction

Menopause marks a biopsychosocial transition in a woman’s life, often accompanied by physical, emotional, and cognitive changes. [

1] While the impact of menopausal symptoms on women’s lives has been widely studied, attention is now being paid to the mental health challenges they experience during this period, personally and professionally. The experience of menopause is highly individualised, with some reporting mild to moderate symptomatology, while others suffer severe symptoms which have a detrimental effect on their working lives. [

2] Past research has found that the severity of menopause symptoms is positively associated with burnout, [

3,

4] and negatively associated with perceived job performance and retention. [

4,

5,

6] As the UK has been facing a significant skills shortage for a number of years, the working population has been encouraged and incentivized to continue working for longer. [

4,

7] Women’s employment rates have steadily improved with evidence showing that 68.6% percent of women between 50 to 64 years of age were employed, an increase of more than 20% since 1992. [

8] This is a positive trend, although research has indicated that menopause symptoms typically occur in our 40s. [

4]

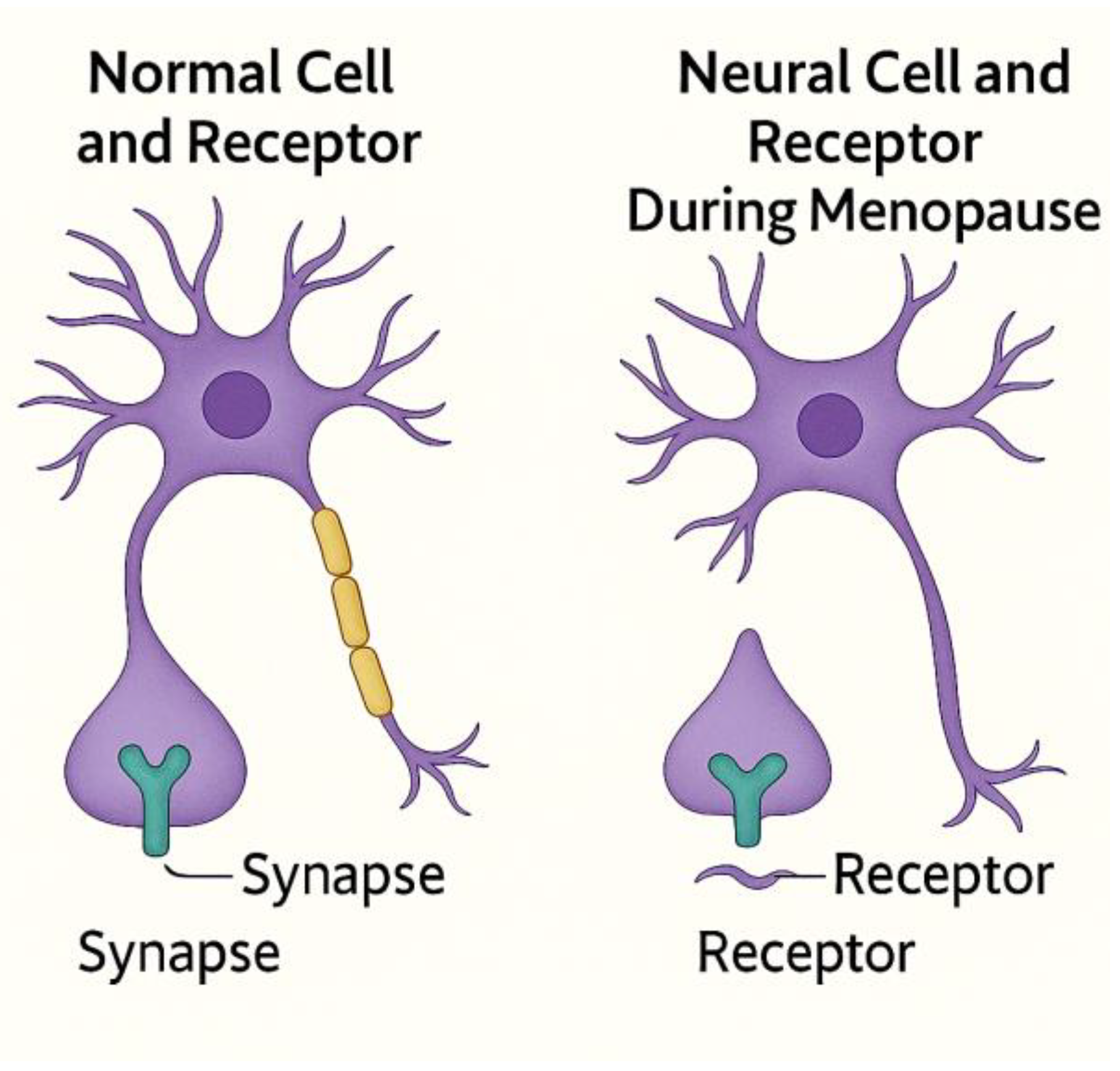

The menopause-related cognitive changes that impact women’s working lives are linked to hormonal fluctuations, disrupted neural connectivity, impaired synaptic plasticity, and altered neurotransmitter function, contributing to memory deficits, executive dysfunction, and long-term neurological vulnerability (see

Figure 1). Symptoms such as forgetfulness and difficulty concentrating can severely undermine self-confidence, performance, and impact the overall wellbeing of an employee. [

5] Perimenopausal, menopausal, and post-menopausal experiences comprise physical, physiological, and psychological symptoms that require holistic management. [

9]

The need to provide better support for women during the menopausal transition has been recognised by employers across public, private, and voluntary sectors. Legislations are set to expand in the United Kingdom (UK) with changes to the Employment Rights Bill, where the initial report (July 2025) outlined that menopause action plans will take effect for all employers from 2027. The UK government has outlined a roadmap for delivering these changes as part of the ‘Implementing the Employment Rights Bill’, emphasising the need for workplace policies and pathways that support employees. Similar actions are being taken elsewhere: for example, the need for specific workplace menopause policies has been recognised in the US, Australia, and Canada.

Theory

The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory [

10] is a useful theory to understand menopause in the workplace. It posits that individuals rely on valued resources, such as time, energy, and money, when responding to various demands (resources are defined as anything perceived as valuable). [

11] The use of these resources can lead to their depletion, and such losses are often linked to adverse outcomes, including increased strain and diminished well-being. Individuals should therefore strive to replenish and accumulate their valuable resources so as to experience positive outcomes. Resources have been differentiated in terms of personal (e.g., time and health) and contextual (e.g., social support). [

12] Some studies have also conceptualized personal and contextual resources as ‘key’ resources - i.e., those that can help individuals manage their other resources. [

13] Flexible work arrangements could be considered as a ‘key’ resource because they can help individuals manage their time and energy more efficiently.

COR theory has been used to explore the effects of menopausal physical and psychological symptoms as a type of demand on diverse workplace outcomes, and the role of workplace social support in determining these effects. [

2,

5] Steffan and Potočnik (2023) observed a negative association of the severity of psychological symptoms with retention, and a negative association of the severity of physical symptoms with perceived performance. They also found that the use of selection, optimization and compensation (SOC) strategies as a type of personal resource, in conjunction with supervisory support as a type of contextual resource, buffered the negative effects of physical symptoms on performance. Drawing from a longitudinal sample, Potočnik et al. (2025) showed how changes in the severity of physical and psychological menopause symptoms over time in the context of work can be associated with either resource depletion (i.e., when symptoms worsen) or accumulation (i.e., when symptoms become less severe), which explained changes in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization – i.e., two dimensions of burnout. [

2] This study also showed that the usefulness of flexible work – another valuable ‘key’ resource – protected women who experienced more severe physical symptoms over time.

The aim of this paper is to understand women’s experiences of cognitive changes during perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause, their impact on work performance, and consequences for mental health. The findings are discussed in relation to COR theory to reveal data-driven implications for health and wellbeing as well as workplace support. Understanding women’s lived experiences of cognitive symptoms across the menopausal transition is essential to inform targeted interventions, workplace accommodations, and mental health support strategies. This is particularly important given the growing proportion of midlife women in the workforce globally and the economic and societal implications of unaddressed menopausal challenges.

Results

Cognitive changes affecting executive function had a significant impact on the women’s perceptions of their own work performance, which in turn impacted their mental well-being. These experiences are examined through four key themes: Overall impact: perceived inability to work efficiently; Loss of control and sense of self; Anxiety, struggle, and adaptation; and Masking and workplace support.

Overall Impact: Perceived Inability to Work Efficiently

The women described cognitive changes, particularly around memory (working, short term, and episodic) and ‘brain fog’ as creating significant challenges at work. The combination of brain fog, characterized by difficulty focusing on tasks or not being able to follow instructions, and problems with memory had a serious impact on the women’s perceptions of their own ability to work efficiently.

Mind fog, brain fog, whatever you want to call it, forgetting stuff with people saying, ‘Oh, can you remember we had that conversation?’ No, you know, hearing stuff and not taking it in, all of that is far worse than I ever, ever expected it to be. I know, brain fog is a very common thing talked about with menopause, but I didn’t expect it to be this real. (Grace)

Grace was surprised at the intensity of the cognitive changes she experienced, even though she was aware that brain fog was a key symptom of menopause. Similarly, there was surprise at how quickly the cognitive difficulties could appear as if out of nowhere.

It just seemed very rapidly that I didn’t have the cognitive skills that I did have. I mean, for a number of years in the job that I had, I worked in it for 20+ years. I would be ‘Oh, if you want to know policy or you know some information go to Bree because she’ll be able to explain it better and she knows all about it’, to you know, I couldn’t even work out how to reduce the size of my screen, just basics. It is just my abilities from being very assertive and very able to articulate myself. I suddenly almost sort of shrunk as a person. It was quite alarming actually. (Bree)

The suddenness of cognitive changes, taking Bree from being the ‘go-to’ colleague who knew all the work-related policies, to being someone who struggled to remember how to complete basic tasks, was frightening and challenged her sense of self. Being unable to express her ideas and thoughts as clearly as before created a feeling of being less capable (we return to a changing sense of self later). Many women described a feeling/awareness of their brains getting ‘full’ more quickly as the processing of information slowed down, which was seen as another indicator of brain fog.

I don’t feel like I can take on as much anymore just because my brain just can’t, it just gets too full too quickly and I forget things a lot, so I have to write things down. I’m juggling more anyway so you kind of think, I think the whole thing with work, especially with women, you can blame a lot of things on other things. (Rose)

Looking for explanations, described here as a common approach that women take, featured in many of the women’s accounts. In the example above, Rose assumed her cognitive changes were related to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the impact of isolation rather than the menopause. Indeed, many participants had begun to notice their first menopause symptoms around that time, which, upon reflection, they felt were exacerbated by the stress due to the uncertainty of the pandemic, the lifestyle changes imposed by the Government (e.g., lockdown), and the impact on work (e.g., fewer staff due to illness).

Difficulties with working and episodic memory not only impacted the women’s current working lives, they impacted their career progression, hampering thoughts about future possibilities and jobs they were capable of doing. As Kate describes:

It has definitely impacted my work because there have been opportunities to progress and I was too anxious to actually consider doing that. I’ve never left a job because of how I was feeling, but I have not gone for promotions because I felt I wasn’t competent enough to do the job. (Kate)

There was often a vicious cycle of being forgetful and worrying about being forgetful that the women found themselves in, which led them to seriously doubt their competence and capability to progress career-wise.

I’m starting to panic about not remembering and worrying about not remembering, and it seems to dominate a lot of my thoughts and definitely from a career progression point of view you sort of think ‘I’m at a position where my kids have left home, I’ve got all this experience and this wealth of knowledge’ and people that send me job applications and ‘oh, you should be getting this’. And I’d say ‘I can’t remember what I had for breakfast, so how the hell can I be applying for this job that’s gonna pay me and have this responsibility’… if you feel you can’t remember what you did yesterday then you feel like fraud really and it very much knocks your confidence. (Eve)

Feeling like a fraud, as Eve describes, was shared by other participants. It suggests the experience of imposter syndrome; that the women felt they should not be in that professional role and should not have the responsibility and the pay it brings (more below). Experiencing imposter syndrome in a job they were capable of doing with many years’ experience behind them had a big impact on the participants’ confidence.

Loss of Control and Sense of Self

The influence of brain fog and memory loss on the women’s confidence caused uncertainty about their own behavior. They felt a loss of control, such as forgetting their speech mid-sentence or what work they had done, needing to retrace their steps, which was concerning.

I could see that I was not getting as much work done as I should. I’d go off in one direction, I’d forget what I was doing and do something else and then I’d kind of have to retrace my steps. I felt like I was having to do it the next day of work just to make up for the fact that I wasn’t really working properly, which I found very frustrating. (Layla)

Having to repeat actions previously performed to ensure she had not missed anything, as Layla described above, increased the participants’ workload. Thus, the women could find they were doing more than before yet they felt less capable. The combination of increased workload, cognitive changes, anxiety, and panic attacks had an impact on mental health. Layla went on to say: “and then suddenly I’d find myself just not recognizing myself”.

It is telling that many of the women described not recognizing themselves since experiencing these cognitive changes, which indicates the extent of their impact on mental health. Overall, a strong message from the data was that participants felt they were not getting their work done in the same way as before menopause, and this feeling of inefficiency intersected with their sense of identity.

It’s like a bereavement. The emotions that you experience, it’s a loss, it’s because you’ve lost yourself, basically, and you go through one-thousand-and-one emotions. Yeah, horrendous, horrendous times. (Tess)

The impact on mental health from the suddenness and intensity of these cognitive changes, and the uncertainty about one’s own actions, led to doubts in productivity at work, a sense of being out of control, and feeling like they were not themselves. It is perhaps no surprise that the majority of participants (n=36) reported feeling overwhelmed at work (from the questionnaire, data not shown).

Anxiety, Struggle, and Adaptation

A sense of inefficiency at work exacerbated the participants’ anxiety. Some experienced anxiety for the first time during the menopause transition, while others with pre-existing anxiety felt their menopause symptoms had increased it.

I felt like the brain foggy type stuff was starting to make me more anxious. Usually, I’m in a training role and I don’t usually get stressed and worried… it’s just that bit where your head empties and that’s not usually something that happens to me so I was ending up really anxious... I’m generally quite resilient, I have a lot of things going on just because of my personal life, but yeah, it was sort of getting more difficult. (Phoebe)

Phoebe raises an important point about ‘things going on’ in her personal life, and how that could impact her professional life. Indeed, a key finding was the overlap between the personal and professional domains of the women’s lives, forming a reciprocal relationship where challenges in one domain could influence the other. Menopause symptoms do not simply ‘turn off’ when the women move from one environment to another, although features of the work environment were perceived to influence the intensity of their symptoms. Tiredness from not sleeping well due to menopause symptoms was believed to have an impact on cognitive function, both memory and brain fog, and this in turn connected with performance issues.

The reason that I became aware of my chemistry changing was that I was starting to forget significant things at work and my performance was noted to be poorer than it had been, which affected my confidence and brought to my attention that I wasn’t sleeping well and that maybe my cognitive abilities were affected sometimes. (Jane)

The sense of being less efficient than before the menopause affected the women’s personal as well as professional domains. A key finding was the process of struggle and adaptation, where participants felt they had to adapt to the ‘new me’ even if it caused them frustration.

I was feeling mental confusion, lack of memory, lack of focus, and that’s been my major experience all the way through, the hot flushes stopped very quickly with HRT… but since then for 3 1/2 years I’ve really struggled and had to adapt. I think it’s impacted on my job. It’s definitely impacted my family and having to get used to myself being unreliable and sort of be frustrated and all these things when I can’t do things as efficiently as I normally do. (Layla)

Masking and Workplace Support

To avoid being seen as incompetent at work, as some of the women described it, they would hide the effects of symptoms on their performance. Attempting to ‘mask’ the changes in their abilities meant they would not be seen to be making mistakes by their line managers. Being concerned that they were not ‘functioning’ as they should be, and the implications of this (more later), was incredibly unsettling for some.

No one brought it to my attention, so I obviously managed to, you know, fool them that I was still functioning properly, even though I knew I wasn’t. (Rachel)

Difficulty processing information on a regular and long-term basis, was frustrating and again presented a challenge to the women’s sense of self. Becoming ‘inefficient’ and a fear of being found out connects with the earlier described imposter syndrome.

I felt like within a week or two, my brain was definitely functioning in a way that it was non-functional. Definitely, completely non-functional, to the point of thinking ‘I’m really not doing my job because I can’t think my way through anything’. Usually, my mental processing would be pretty good… it had been going on for months and got so much worse that I was feeling… probably crying every day and just really tearful, just really miserable and most frustrated about not being able to function at work because somebody at some point is going to work out that I’m nonfunctional. (Phoebe)

Masking their reduced performance was a strategy that sometimes worked and sometimes did not. The process of trying to hide their difficulties, which they perceived as inefficiencies, was stressful in itself. However, it was clear from the findings that certain aspects of the work environment, such as flexible hours, supportive line managers, colleagues who were experiencing similar menopausal symptoms, and the option to work from home, could reduce the impact that the menopause-related cognitive changes had on women’s experience at work. Again, the work environment, when less stressful, could help the women deal with their symptoms and take back some control.

I’m very lucky that I’ve got a female boss, so I can, you know, mention it. I went on a retreat, like a menopause retreat, so it was a day of learning about these things and she gave me the day for free. She said ‘no that’s a wellbeing day, don’t take it out of your annual leave because it’s what you need and please tell me anything that you’ve learned’. So that kind of thing is incredibly supportive and being able to talk about it with people at work to say that you can say, ‘yeah, I’m having a moment, give me a give me a few minutes and I’ll be back’. (Rose)

Negative experiences were heightened for the women who worked in environments that were inflexible and unsupportive. Although for Isabelle below, her line manager was a woman of a similar age, yet there was a perceived lack of support, probably because the line manager did not experience the same severity of symptoms. In other words, the lack of understanding and awareness of symptoms might lead to the lack of support, which could be seen in Occupational Health referrals on the grounds of poor performance.

The line manager I had at the time, same age as me and from an operational background, when I knew more about it, I did explain it to her. We have kind of menopause awareness sessions and things like that. She didn’t know anything about it. She wasn’t experiencing any symptoms herself, lucky lady, and I asked for an Occy [occupational] Health referral to see what support is available. She made that referral and then put poor performance as the reason for the referral, and she’d never spoken to me about performance ever, and then when I did take some time off work and the Occy Health report said, you know, ‘potentially protected for age discrimination and this is what it looks like’, when I had to speak to her about keeping in touch, coming back to work, I remember crying my eyes out on the phone, which I didn’t want to do because she didn’t understand, she wasn’t a sympathetic person, and I remember her trying to be sympathetic, ‘look, there are things we can do, you could take a demotion’… she might have been saying nice things around it but all I heard was ‘poor performance’ on something that I’d requested when we’ve never had a performance conversation. (Isabelle)

For Isabelle, conversations with her line-manager about returning to work after time off for menopause-related symptoms were not a positive experience. The suggestion of reducing her working hours, or taking a demotion, reinforced the initial message her line manager had passed to Occupational Health about poor performance. In the absence of performance meetings, the suggestion of poor performance was ill-placed and distressing for the participant.

While having the opportunity to work flexibly was perceived as part of the solution to help women manage their cognitive challenges, in practice this was not always effective. For example, Susan worked freelance and had flexible working patterns which she controlled. However, she experienced an overwhelming lack of ability to function in all aspects of life, which could result in feelings of hopelessness.

I worked freelance so I can choose to work when I want to. I don’t have to phone in sick to anybody, so if I can’t go to work I just need to catch up at some other point. But I just couldn’t go to work, couldn’t drive the car, couldn’t do appointments. (Susan)

Discussion

The findings highlight the significant challenges participants went through at work due to menopause-related cognitive changes and feeling that their ability to process information had been compromised. Such changes impaired the women’s ability to work efficiently, negatively affected their self-confidence, and often changed their professional life-course to avoid career progression opportunities due to fear of being ‘caught out’ with poor performance ratings. Looking at the findings through the lens of Conservation of Resources, [

10,

11] they indicate menopause as a major life change with demands that can deplete women’s cognitive abilities, which in turn negatively impacts their productivity and perceived performance. In many cases, the onset of menopause symptoms was noticed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which arguably compounded the detrimental effects of menopause on mental health, significantly depleting their resources. The lack of such experiences having been considered in existing pandemic preparedness frameworks is of concern.

The sudden onset and heightened severity of cognitive changes during the menopausal transition contributed to uncertainty regarding both current and future occupational productivity. Although participants were aware that memory lapses and brain fog were frequently reported during menopause, the lived experience was more profound than anticipated. These neurocognitive disruptions precipitated feelings of imposter syndrome, illustrating the detrimental psychosocial impact of impaired executive functioning. Feeling out of control, and in a vicious cycle of being forgetful and worrying about being forgetful, was difficult to get out of. The reported loss of confidence in themselves and their ability to perform their roles mirrors that found in other studies. [

6,

18,

19] This perceived inefficiency could create anxiety for the first time or exacerbate pre-existing anxiety, highlighting the biopsychosocial nature of the menopause. Such findings illustrate the principle of the resource loss spiral, [

11] whereby the depleted cognitive resources, such as forgetfulness, can result in further loss of valuable resources, such as mental health. Indeed, data collected from the questionnaire (not presented here) show an increase in mental health issues during perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause for these participants. At the time of the interview, thirty-nine participants reported depression and/or anxiety as menopause-related symptoms, of which eighteen reported having both depression and anxiety, seventeen reported anxiety alone, and four reported depression alone. Compared with their pre-menopausal mental health histories, this represents a substantial increase where only five participants reported depression and seven reported both depression and anxiety.

A prominent finding was the profound alteration in identity closely linked to menopause-related cognitive changes. Women described a loss of self-confidence due to not being able to perform work tasks at previously sustained levels, despite often possessing years of expertise in their respective fields. This erosion of professional self-concept reflects the complex interplay between neurocognitive decline, psychosocial functioning, and workplace demands, which collectively influence self-perception, perceived competence, and occupational efficacy. Feelings of imposter syndrome, where individuals perceived themselves as inadequate or fraudulent despite evidence of competence, were frequently reported. While global research has documented the detrimental effect of menopausal symptoms on women’s quality of life, there remains a paucity of empirical evidence specifically exploring the intersection between cognitive changes and identity reconstruction within occupational settings. This gap underscores the need for focused research that examines how cognitive and psychosocial changes during menopause reshape professional identities and career trajectories. [

20] These findings resonate with results from the UK Government’s Women’s Health Strategy public consultation, [

15] which highlighted that many women experience a loss of confidence, reduced workplace engagement, and identity disruption linked to unaddressed menopausal symptoms. The consultation revealed that women frequently downplayed or concealed cognitive difficulties to avoid punitive measures such as demotion or reduced hours, thereby compounding psychological distress and perpetuating gendered workplace inequities.

The Conservation of Resources theory posits that individuals confronted with stressors experience a depletion of personal resources such as self-efficacy and social capital. [

11] This resource loss can trigger a negative spiral unless offset by the acquisition of compensatory resources, such as organisational support and adaptive workplace accommodations. Our findings demonstrate that supportive managerial practices, including empathetic recognition of symptoms and the provision of flexible work arrangements, were instrumental in mitigating the negative cognitive and psychosocial effects of menopause. This is consistent with recent evidence indicating that supervisory social support significantly improves women’s ability to manage menopause-related challenges at work. [

6] Conversely, environments characterised by managerial rigidity and lack of awareness exacerbated feelings of inefficiency, leading women to internalise blame for performance changes and to engage in symptom concealment. Such organisational cultures were frequently perceived as discriminatory, negatively influencing job satisfaction and long-term career progression. Participants reported a persistent fear of being “found out,” which carried tangible risks such as demotion or enforced reductions in working hours. For women approaching later stages of their careers, these consequences not only threaten financial security ahead of retirement but also reinforce systemic gender inequalities in the workplace. It has previously been described as a ‘penalty’ that women suffer when their ageing bodies ‘fail to comply’ with the norm of an ideal worker. [

21]

Collectively, our findings, and corroborating evidence from national policy consultations, highlight a critical gap in workplace health strategies. Addressing menopause-related cognitive changes requires moving beyond individual-level coping mechanisms to structural, evidence-based interventions that foster identity preservation, reduce stigma, and create equitable, supportive occupational environments. This shift is essential for mitigating health inequalities and promoting gender equity within professional settings during midlife transitions.

Workforce Implications

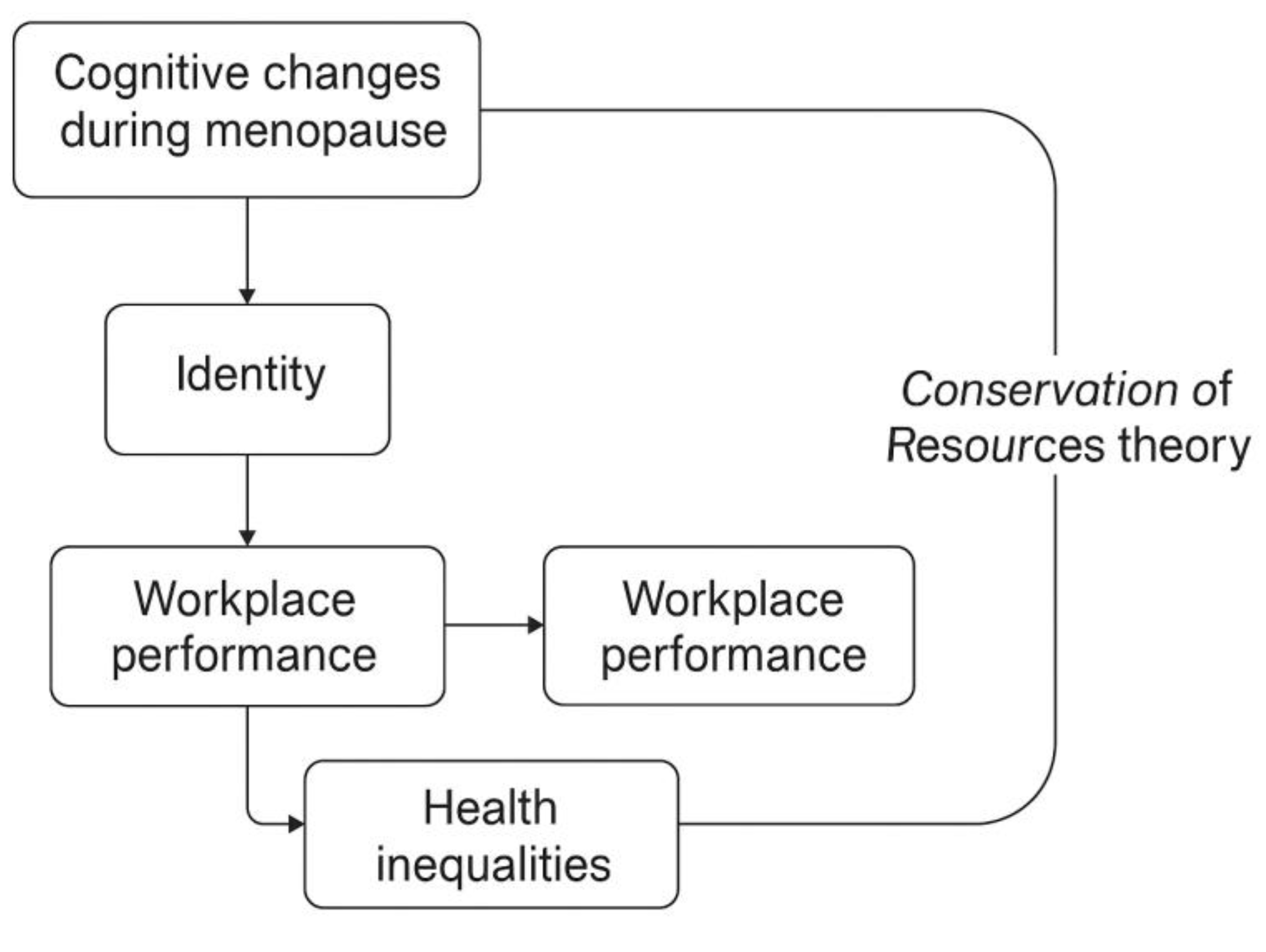

Understanding participants’ experiences through the lens of the Conservation of Resources theory highlights that preserving personal resources during the menopause transition is vital to supporting women’s overall wellbeing (see

Figure 2). Menopausal symptoms can significantly impair productivity, self-efficacy, and long-term career trajectories. Organizational culture should evolve to recognize cognitive changes as legitimate occupational health concerns. Indeed, supporting women’s wellbeing benefits organizational outcomes by fostering positive work environments and improving productivity. Practical interventions can include autonomy in task management, flexible working patterns, and managerial education. Employers can provide consistent and tangible workplace support by utilizing evidence-based resources like the MARiE toolkit or Menopause Information Pack for Organizations (MIPO).

Labor Law Implications

Labor laws in various countries offer limited protection for menopausal workers. The UK currently offers protection under the Equality Act 2010, with claims typically framed around sex, age, or disability discrimination. Findings from this paper suggest that inadequate workplace support exacerbates cognitive and psychological symptoms, leading to reduced job satisfaction and increased risk of demotion or reduced hours. This highlights a need for legislative and regulatory reforms that specifically recognize menopause as a workplace health issue. Legal frameworks should mandate employer education, enforce organizational compliance with menopause policies, and incentivize adoption of evidence-based interventions such as MARiE. Embedding these changes could mitigate gender inequities and enhance retention of skilled workers during midlife.

Clinical and Health Implications

Cognitive difficulties and unsupportive work environments can create and/or exacerbate mental health symptoms and reduce women’s quality of life. From our findings, support for managing menopausal symptoms must extend beyond addressing vasomotor symptoms to include comprehensive cognitive, psychological, and occupational assessments. Integrating cognitive screening, mental health interventions, and workplace-focused support can sustain resource preservation. Support should consider culturally diverse beliefs, stigma, and healthcare-seeking behaviors. Similarly, it should recognize the influence of HRT and that it is not always the panacea for cognitive health: some of our participants on HRT reported significant cognitive challenges that impacted their work and mental health. HRT can take time to stabilize which can affect work productivity even more, and for those with conditions e.g. endometriosis, cognition can be compromised by pain and fatigue, thus necessitating nuanced support. The International Menopause Society provides a toolkit for managing cognitive issues in menopause. [

22]

Strengths and Limitations

Exploring lived experiences through qualitative interviews has shed light on the ways that menopause-related cognitive changes can impact the professional lives of working women. Our findings provide compelling evidence on perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause, complementing the many quantitative studies on the topic. A key strength lies in the broad eligibility criteria, which captured diverse menopausal experiences across cognitive, psychological, and occupational domains. This inclusivity enhances the project’s applicability to various workplace and healthcare settings. While organisational structures differ, the similarity in participants’ experiences suggests that our findings are transferable to other contexts. We have also captured the perspectives of some who had not sought professional help for their menopause symptoms, which is a strength, as many studies recruit participants from menopause clinics. In this way, our findings are not biased towards a solely clinical sample and may be transferable to a wider population.

Our analytical process was systematic, adding depth and trustworthiness to the findings. Team-based approaches to qualitative data analysis have been argued to enrich the interpretation of data and conceptual analysis. [

23] Indeed, our collaborative approach to data analysis was rigorous and revealed rich insights, as four women from different disciplinary backgrounds and age groups interpreted the data.

The majority of the participants interviewed were educated to University level and predominantly worked in the healthcare sector, which may suggest they are more confident speaking about their health. The constrained availability of resources and funding restricted the qualitative sample size and longitudinal follow-up; however, we intend to further diversify our sample by building rapport with a variety of non-governmental organisations and community centres.

Menopausal change is not uniform across populations. However, we did not find any differences across the sample due to ethnicity; further research should be conducted to explore this in more detail. Cisgender women, whose menopausal transitions are typically biologically mediated, may experience symptom trajectories distinct from transgender and gender-diverse individuals undergoing hormone therapy or medical/surgical menopause. These differences can influence the timing, intensity, and neuropsychological manifestation of cognitive changes, thereby affecting workplace participation and social functioning in unique ways. Further qualitative research should be conducted because such complexity underscores the necessity for gender-sensitive and shared-care approaches that move beyond binary conceptualisations of menopause. Implementing tailored interventions that acknowledge cis and transgender experiences can mitigate productivity loss, alleviate psychosocial distress, and challenge structural gender biases embedded within workplace policies and healthcare systems.

MARiE Consortium

Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Diana Chin-Lau Suk, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Damayanthi Dasanayaka, Prasanna Herath, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Jeevan Dhanasiri, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Heitor Cavalini, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih, Andy Fairclough, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuazi, Michael Nnaa Otis, Jeremy Van Vlymen, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Bethel Chinonso Okemeziem, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Fred Tweneboah-Koduah, Jie Sun, Nana Afful-Minta, Tharanga Mudalige, Vindya Pathiraja, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo, Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Chukwuemeka Chijindu Njoku, Bernard Mbwele, Ieera Madan-Aggarwal, Toh Teck Hock, Ganesh Dangal, David Chibuike Ikwuka, Pradip K Mitra, Irfan Mohammad, Rabia Kareem, Crsitina Benetti-Pinto, Victoria Corkhill, Kingshuk Majumder Jian Shi, Sohier Elneil, Kath Riach.