Submitted:

28 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

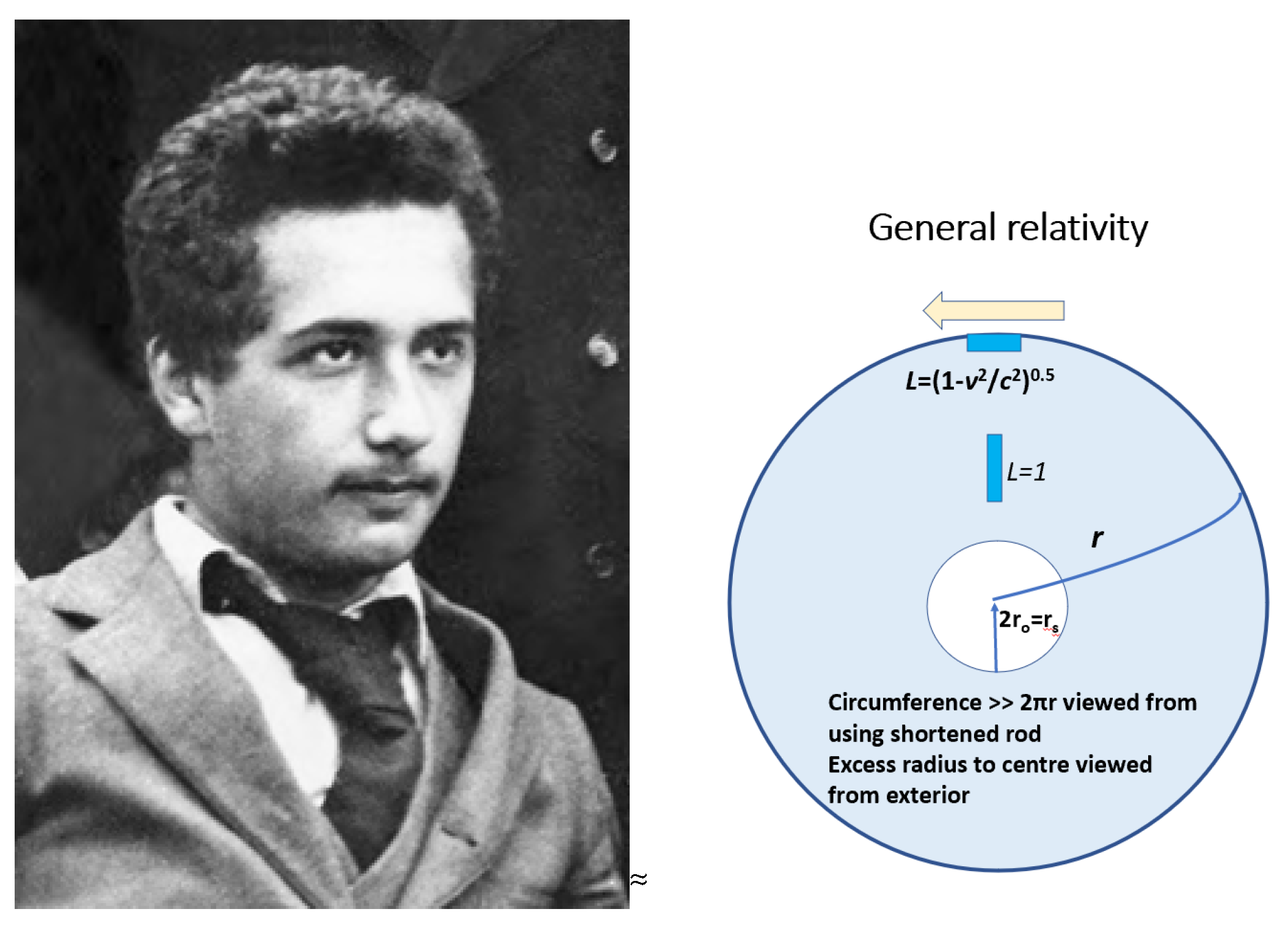

2. On General Relativity

2.1. Einstein’s Choice of Coordinates for Field Equations of General Relativity

2.2. The Schwarzschild Metric

2.3. Droste’s Variational Metric

2.4. An Alternative Metric

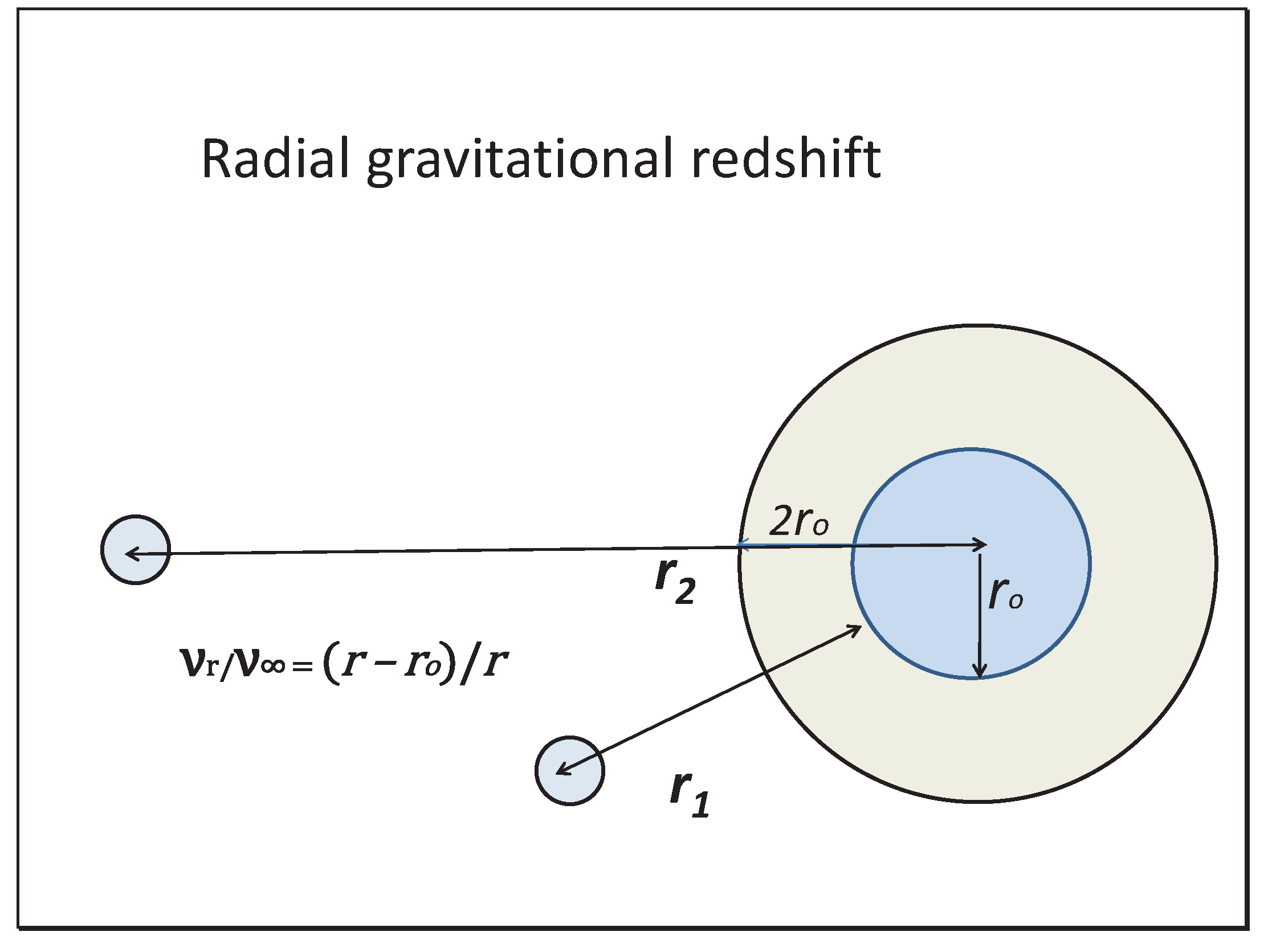

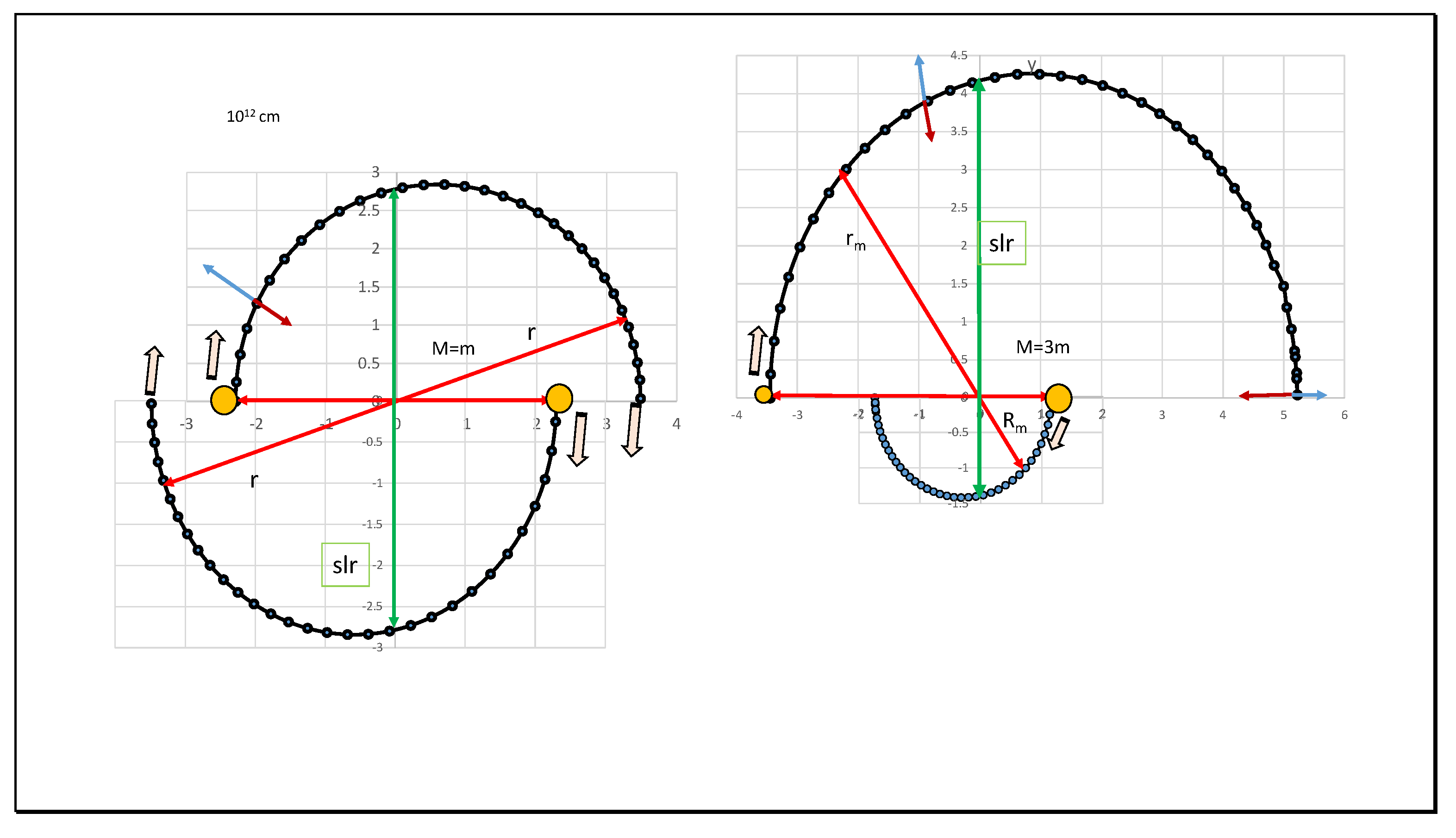

3. Radial Action Relativity

- (i)

- Radial action relativity employs polar coordinates ranging from zero gravity at infinity to a radial surface on a sphere at the gravitational radius (ro = MG/c2) defining the curvature for motion of the speed of light (1/r0).

- (ii)

- Matter considered to be at the origin of coordinates shortens the radial dimension (to r – ro). This shortening is caused by pressure excluding all physical interactions in the interior space occupied by the ultimate particles of matter. Yet the energy required by processes with diminished inertia (mr) may allow higher frequencies of orbital motion. This exclusive central surface for gravitational objects is a result of the speed of transmission having a maximum speed of c, quite unknown to Newtonian gravity (MG = RV2 = roc2) that assumed that gravity acted without a time delay.

- (iii)

- The gravitational radius is directly proportional to the collective mass, implying a material inertia mr0 distributed on a surface area of 4πr02 surrounding a void. We will show how this revision of radial action gives rational algorithms for both the Lorentz transformation [10] and the conclusions of general relativity, retaining a Euclidean framework consistent with the invariance of least action.

3.1. The Radial Gravitational Algorithm for Stationary Clocks

3.2. Using Natural Radial Coordinates

3.4. Comparing Mathematical Relativistic Corrections

3.5. Comparisons of Schwarzschild and Radial Action Metrics

3.6. The Lorentzian Transform in General Relativity

3.7. The Inertial Radial Relativity Correction

3.7. The Gravitational Radius and the Gravity Effect on Time and Space

4. Equivalences in Application Between Radial Action and General Relativity

4.1. Lagrangian Variations of Action and Central Force Orbital Equations

4.2. Radial Action Relativity and Precession of Ellipses

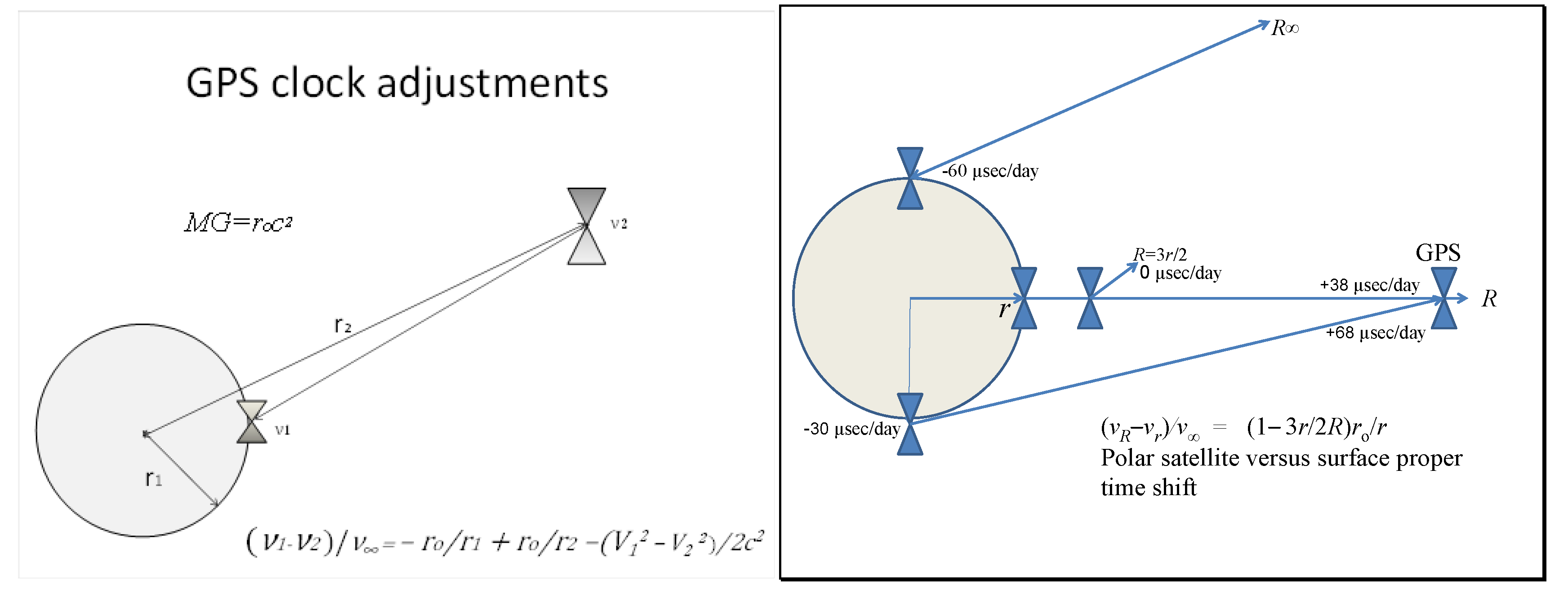

4.3. Corrections for Clocks in Motion

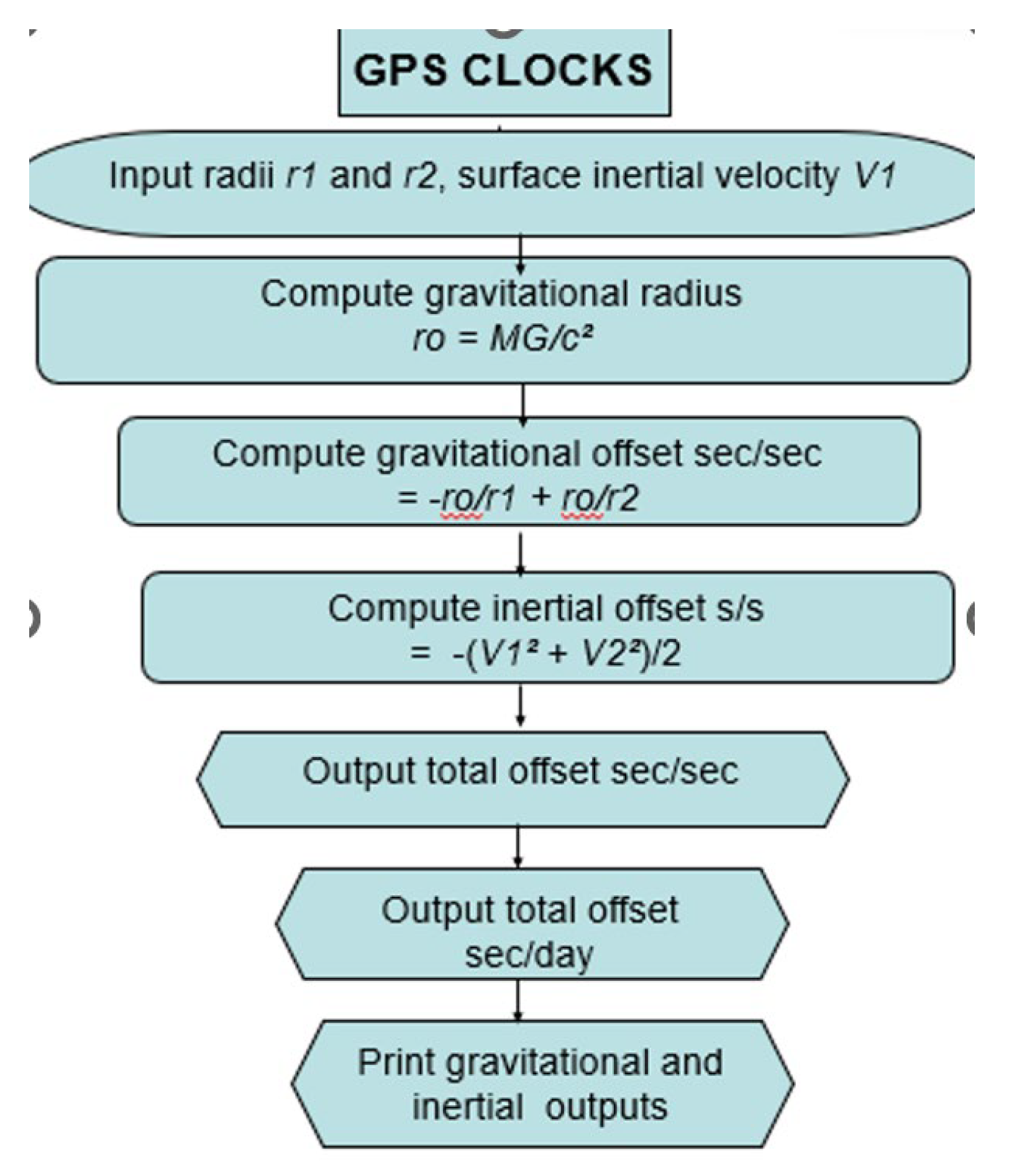

4.4. Radial GPS Clock Adjustments Involving Both Gravitational (r0/r) and Inertial (r0/2r) Corrections

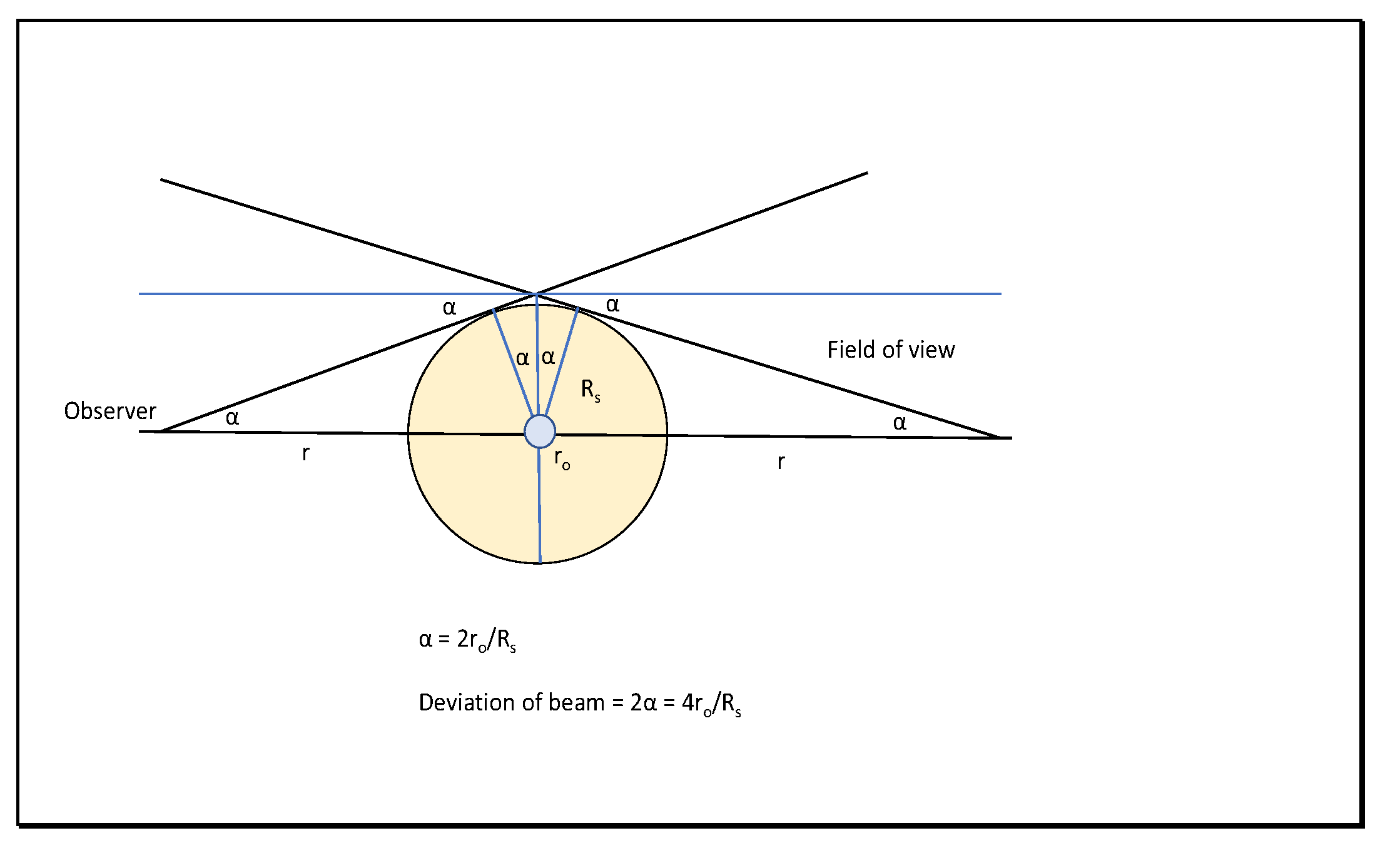

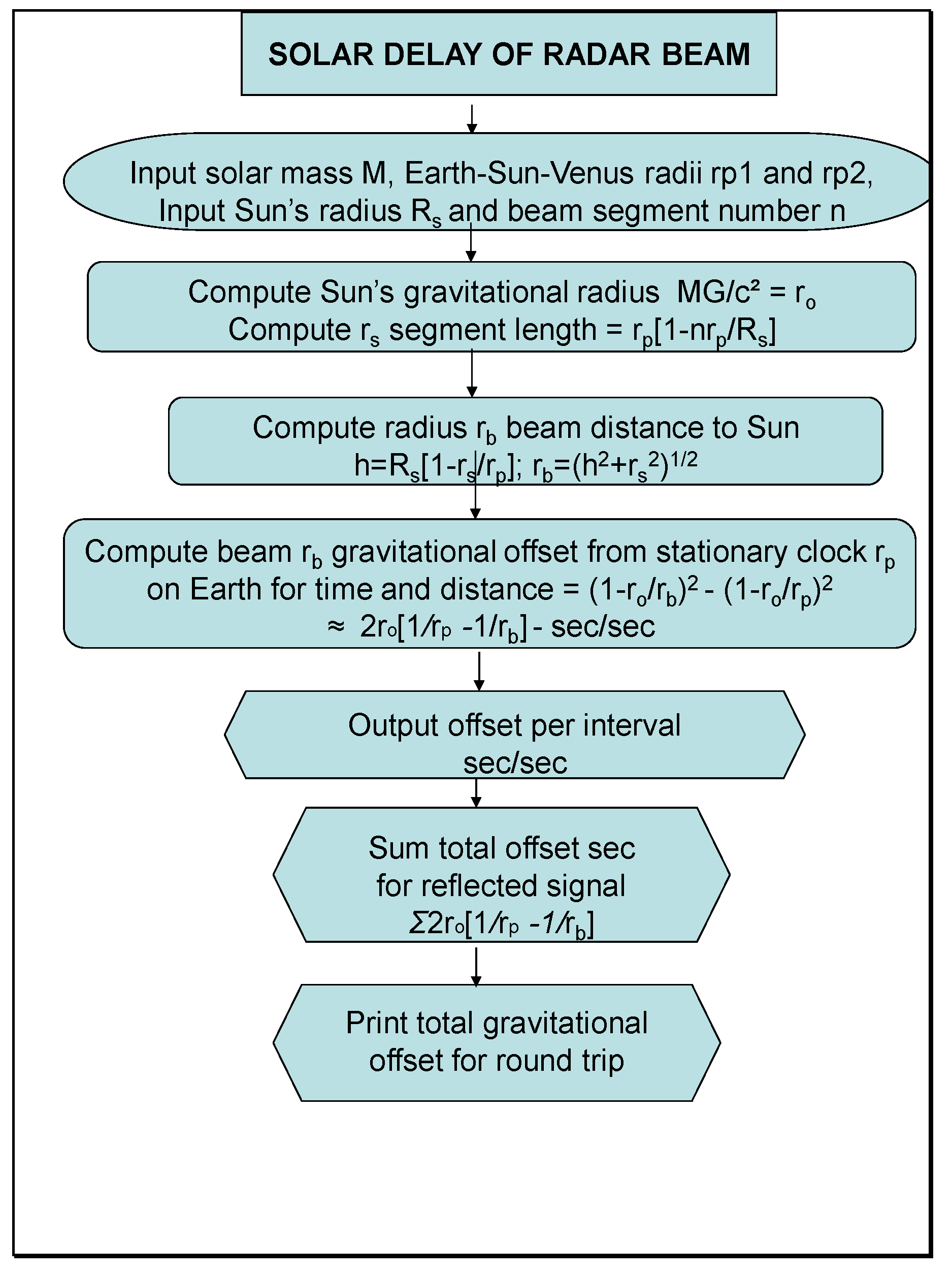

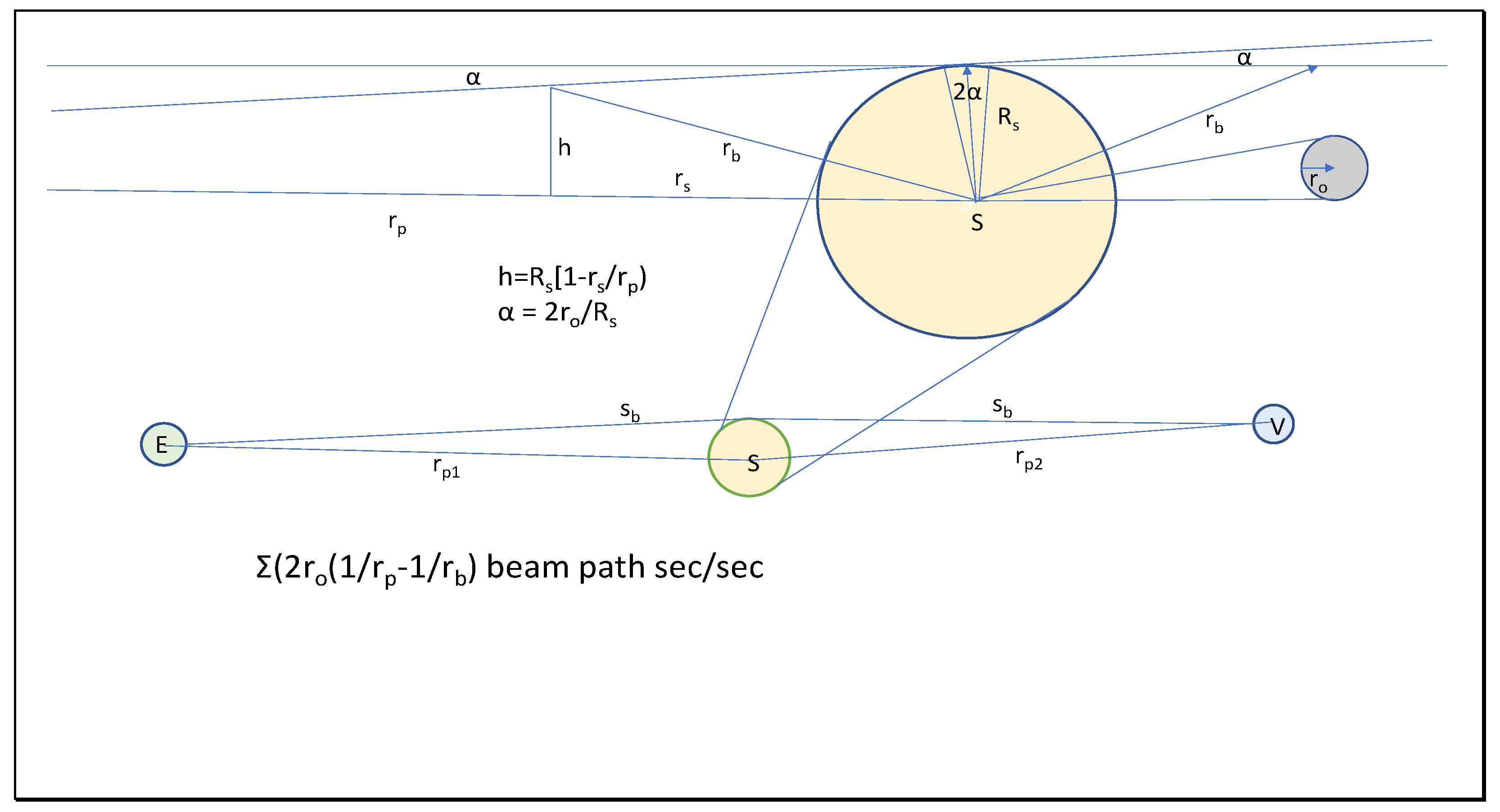

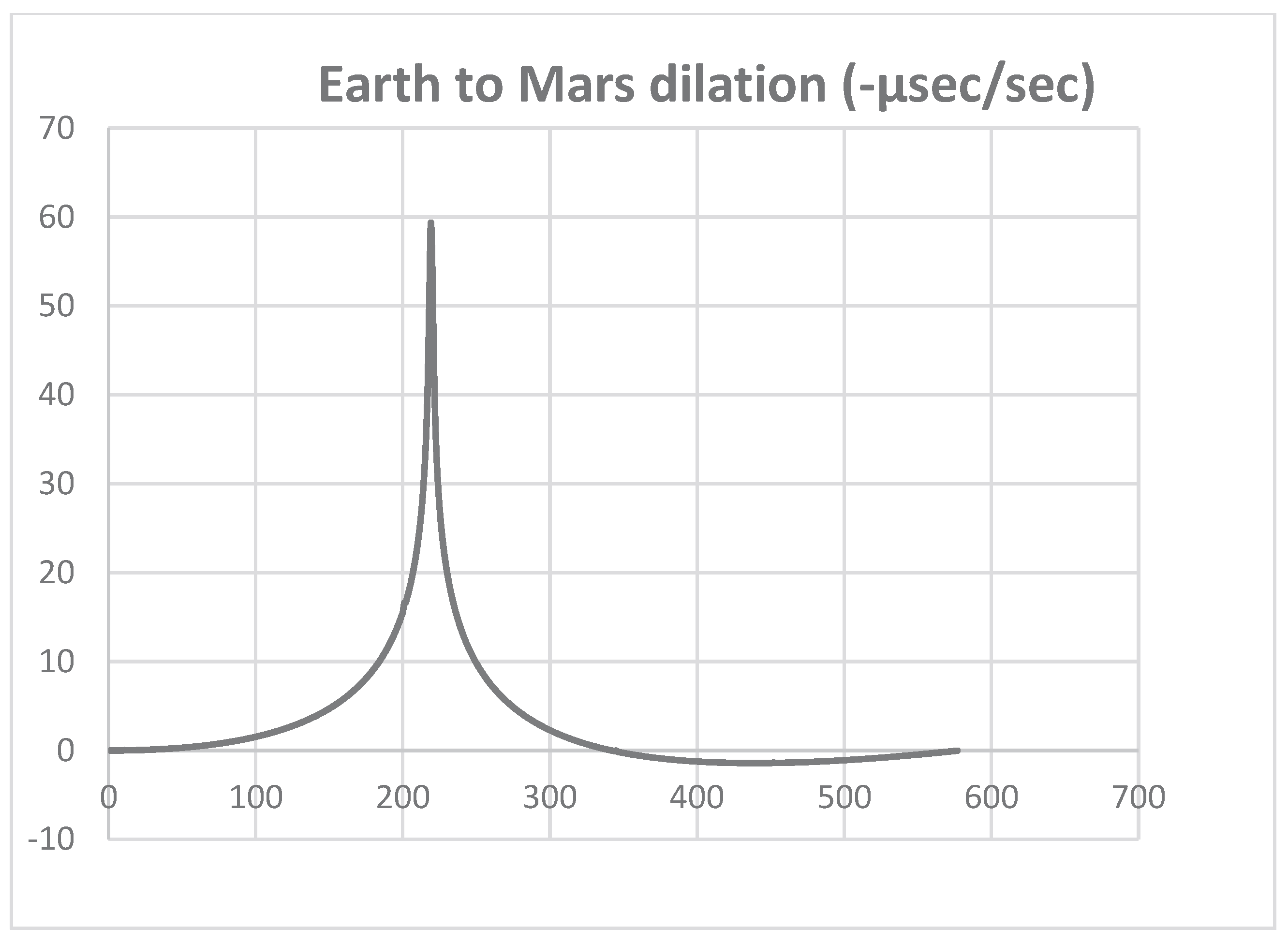

4.5. Bending and Time Delay of Light Beams Near Masses

4.6. Radial Action Algorithms for Black Holes or Void Horizons

4.6.1. Hawking Black Holes at the Schwartzschild Radius (α = 2ro)

4.6.2. A Radial Action Black Hole Surface at ro

4.6.2. Gravitational Radiation

5. General discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Einstein, A. On the electrodynamics of moving bodies. 1905, Annalen der Physik 17, In The Principle of Relativity, by H.A. Lorentz, A. Einstein, H. Minkowski and H. Weyl, pp. 37-65. Dover Publications, Mineola.

- Einstein, A. The foundation of the general theory of relativity. 1916, Translated from “Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitatstheorie , 1952 Annalen der Physik, 49, in The Principle of Relativity, by H.A. Lorentz, A. Einstein, H. Minkowski and H. Weyl, pp. 111-164, Dover Publications, Mineola, New York.

- Feynman, R.P. Six Not So-Easy Pieces. 1963, Einstein’s Relativity, Symmetry and Space-Time. Penguin, California Institute of Technology.

- Einstein, A. Einstein’s Essays in Science, 1934, from The World as I see It, Dover 2009, p. 84, Wisdom Library, New York.

- Schwarzschild On the gravitational ield of a mass point according to Einstein’s theory, 1916, Translation by S. Antoci and A. Loinger, arXiv:physics/9905030v1, 12 May, 1999.

- Kerr, Roy P. Gravitational field of a spinning mass as an example of algebraically special metrics. 1963, Physical Review Letters. 11, 237–238. [CrossRef]

- Droste, J. The field of a single center in Einstein’s theory of gravitation, and the motion of a particle in that field. 1916, Proceedings Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, 19 I, 1917 (communicated by Prof. H.A. Lorentz).

- Droste, Johannes Het zwaartehrachtsveld van een of meer lichamen volgens de theorie van Einstein, 1916, E.J. Brill, Leiden ,Thesis.

- Einstein, A. Hamilton’s principle and the general theory of relativity, 1916, Translated from “Hamiltonsches Princip und allgemeine Relativitätstheorie”, Reproduced in [2].

- Lorentz, H.A. Electromagnetic phenomena in a system moving with any velocity less than that of light 1904. In The Principle of Relativity, H.A. Lorentz, A. Einstein, H. Minkowski and H. Weyl, pp. 9-24, Dover Publications, 1952 New York.

- Einstein, A. Relativity: The Special and General Theory, 1916, Three Rivers Press, p. 49-54, 15th Edition, 1961.

- Kennedy, I.R. Action in Ecosystems: Biothermodynamics for Sustainability. 2001, Research Studies Press, Boulton, UK.

- Kennedy, I. R.; Rose, M.T.; Crossan, A.N. Improved numerical plotting of elliptical orbits using radial coordinates: Has the real value of Leibniz’s gravitational theory been ignored? 2023, ArXiv.

- Einstein, A. Does the inertia of a body depend upon its energy content. 1905, Annalen Physik 17, 69-71.

- Pound, R. V.; Rebka Jr. G.A. Gravitational red-shift in nuclear resonance, 1959,. Physical Review Letters. 3, 439–441.

- Fraser, B.; Kennedy, I. The two body problem. 2025, arXiv in preparation.

- Aiton, E.A. An episode in the history of celestial mechanics and x utility in the teaching of applied mathematics, 1997, In Learn from the Masters, Frank Swetz, John Fauvel, Bengt Johansson and Victor Katz, Eds., Mathematical Association of America.

- Meli, D.B. Inherent and centrifugal forces in Newton, 2006. Archives Historical Exact Sciences 60, 319-335. (DOI) 10.1007/s00407-006-0108-6. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, I.I.; MacNeil, G.; Breidenthal, J.C.; Brenkle, J.P.; Cain, D.L.; Kaufman, T.M.; Komarek, T.A.; Zygielbaum, A.I. Viking relativity experiment: Verification of signal retardation by solar gravity, 1979, Astrophysical Journal 234, L219-L221. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, I.I; Ash, M.E.; Ingalls, P.; Smith, W.B.; Campbell, D.B.; Dyce, R.B.; Jurgens, F.; Pettengill, G.H. Fourth test of general relativity: New radar result, 1971. Phys. Rev. Lett. 26, 1132-1135. [CrossRef]

- Bertotti, B.; Iess, L.; Tortora, P. A test of general relativity using radio links with the Cassini spacecraft 2003. Nature 425, 374-376. [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein J.D. Black holes and entropy, 1973. Physical Reviews D. 7, 2333.

- Hawking S.W. Particle creation by black holes, 1975, Communications Mathematical Physics 43,199.

- Hill, C.D.; Nurowski, P. The mathematics of gravitational waves: How the green light was given for gravitational wave research, 2017. Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 64, 686-.

- Planck, M. The Theory of Heat Radiation, 1913, Dover Publications New York.

- Nicod, J. Geometry in the Sensible World, 1924. In Geometry and Induction. 1970, University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Popper, K.R. Conjectures and Refutations. The Growth of Human Knowledge. 1965. 2nd Edition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London.

- Brown, K. Reflections on Relativity, 2010, Kevin Brown, Copyright.

| Multiple | Radial action (r-ro)/r |

General relativity [1-2M/R] |

General relativity [1-2M/R]0.5 |

| ro | 0 | -1 | i |

| 2ro | ½=0.500 | 0 | 0 |

| 3ro | 2/3=0.667 | 1/3=0.333 | (1/3)0.5=0.577 |

| 4ro | ¾=0.750 | 1/2=0.500 | (1/2)0.5=0.707 |

| 5ro | 4/5=0.800 | 3/5=0.600 | (3/5)0.5=0.775 |

| 10ro | 9/10=0.900 | 4/5=0.800 | (4/5)0.5=0.894 |

| 20ro | 19/20=0.95 | 9/10=0.90 | (9/10)0.5=0.949 |

| 30ro | 29/30=0.97 | 14/15=0.93 | (14/15)0.5=0.966 |

| 40ro | 39/40=0.98 | 19/20=0.95 | (19/20)0.5=0.975 |

| 50ro | 49/50=0.98 | 24/25=0.96 | (24/25)0.5=0.980 |

| 500ro | 499/500=1.0 | 249/250=1.0 | (249/250)0.5=0.998 |

| System | Celerity (MG) | r1 (cm) | r2 (cm) | Red shift at r1 | Blue shift Δr2-r1 |

| Sun | 1.3275810348x1026 | 6.955×1010 | 1.496 x1013 (Earth) |

2.1238434403823x10-6 | 2.1139695559386 x10-6 |

| Earth (Rebka-Pound) |

3.9860135016x1020 | 6.378137 x108 | 6.37815960 x 108 (Mossbauer) |

6.9535009141160 x10-10 | 2.4638630971075x10-15 |

| Earth (GPS) |

3.9860135016x1020 | 6.378137 x108 | 26.60000 x 108 | 6.9535009141160 x10-10 | 5.2619334043718 x 10-10 |

| Super black hole | 1.125 x 1046 | 1.25 x 1025 = ro |

2.50 x 1025 = rs |

1.0000 ν1/ ν∞ = 0 |

0.5 ν1/ ν∞ = 0.5 |

| Planet | Semilatus rectum (cm) | Precession per revolution = 6πro/l (arc sec) | Revolutions per Earth century |

Precession per Earth century (arc sec) |

| Mercury | 5.540489x1012 | 0.103654458 | 414.9378 | 43.025121 |

| Venus | 1.081947x1013 | 0.053079899 | 162.6016 | 8.6315927 |

| Earth | 1.495568x1013 | 0.038998845 | 100.0000 | 3.8998845 |

| Mars | 2.259289x1013 | 0.025419341 | 53.1915 | 1.3512281 |

| Jupiter | 7.765068x1013 | 0.007395896 | 8.4317 | 0.0622654 |

| Saturn | 1.4225249x1014 | 0.004037162 | 3.3944 | 0.0138273 |

| Uranus | 2.8632611x1014 | 0.002005742 | 1.1903 | 0.0024069 |

| Neptune | 4.4962353x1014 | 0.001277283 | 0.6068 | 0.0007833 |

| Location of clocks | Radius r cm | V cm sec-1 vs the stars | Gravitational shift sec/sec | Inertial shift sec/sec | µsec/sidereal day (86164 s) |

| Clock on equator viewed from stars | 6.378137x108 | 4.6510168x104 | -6.9534850366 x10-10 |

+0.012034399 x10-10 |

-59.8103152738 |

| Clock on Earth’s poles vs. infinity | 6.356752x108 | 0 | -6.97687752974 x10-10 | 0 | -60.1155675472 |

| 1Clock equator from stars | 6.378137x108 | 4.6510168x104 | -6.96480923 x10-10 |

+0.01203440 x10-10 |

-60.11475916121 |

| 1Clock on poles vs. infinity | 6.356752x108 | 0 | -6.95414856 x10-10 |

0 | -59.919725652381 |

| GPS satellite vs clock at equator | 26.56175x108 6.378137x108 |

3.87383430x105 4.6510168x104 |

+5.283792346213 x10-10 | -0.822819882 x10-10 |

+38.4375231374 |

| GPS satellite vs clock at poles | 26.56175x108 6.356752x108 |

3.87383430x1050 | +5.30718489274 x10-10 |

-0.834854282 x10-10 |

+38.5353894776 |

| Satellite 10 km high vs equator | 6.388137x108 6.378137x108 |

7.8981195x105 4.6510168x104 |

+1.088502157903 x10-12 |

-3.459273631 x10-10 |

-29.7126948707 |

| GPS vs. satellite clock at 10 km | 26.56175x108 6.388137x108 |

3.87383430x105 7.8981195x105 |

+5.283792346212 x10-10 |

+2.635517465 x10-10 |

+68.23594106027 |

| Geosynchrony 42,164 km vs. clock at equator |

42.16400x108 6.378137x108 |

3.074255x105 4.6510168x104 |

+5.901646687148 x10-10 |

-5.138927988 x10-11 |

+46.4230433520 |

| Westing clock at 8 km, 1674 km h-1 vs equator | 6.386137x108 6.378137x108 |

04.6510168x104 | +8.710744425905 x10-13 |

0 | +0.0285817685 |

| GPS vs. westing aircraft at 8 km, 800 km h-1 | 26.56175x108 6.386137x108 |

3.87383430x105 2.428777x104 |

+5.275081601787 x10-10 |

-0.831572543 x10-10 |

+38.28705144709 |

| GPS vs. easting aircraft at 8 km, 800 km h-1 | 26.56175x108 6.386137x108 |

3.87383430x105 6.8732222x104 |

+5.275081601787 x10-10 |

-0.808572829 x10-10 |

+38.48522619015 |

| GPS vs. westing craft at 8 km, 15,620 km h-1 | 26.56175x108 6.386137x108 |

3.87383430x105 3.87383430x105 |

+5.275081601787 x10-10 |

0 | +45.45221311364 |

| GPS vs. craft in orbit at 8 km | 26.56175x108 6.386137x108 |

3.87383430x105 7.8993561x105 |

+5.275081601787 x10-10 |

+2.636604255 x10-10 |

+68.17025001720 |

| Property | Sun mass | |

| Hawking | Radial Value | |

| Hawking values for black holes | ||

| Quantity of matter (g) | 1.9891x1033 | x1 |

| Temperature ћc3/8πkGM=ћc/8πkro | 6.17003x10-8 | 1.55138x10-6 (x8π) |

| Entropy (S = Akc3/4ћG =4πMrock/ћ)=NHk | 1.44871x1061 | 1.159299x1060 (1/4π) |

| ST=Mc2/2 (S = Mc2/2T)(ergs) | 8.93812x1053 | 1.78772x1054 (x2) |

| Area = 16πro2 (cm2) | 1.09616x1012 | x1 |

| Area per quantum (cm2) | 1.04465x10-65 | 3.28091x10-65 (xπ) |

| Length 2L (cm) | 3.23210x10-33 | 3.23164x10-33 |

| Number of quanta (8π2Mroc/ħ=NH) | 1.04931x1077 | 8.35136x1075 (x4π) |

| Quantum energy (mc2/2=hv) (ergs) | 8.51809x10-24 | 2.14063x10-22 (x8π) |

| Planck length (ħG/c3)0.5 (cm) | 1.61623x10-33 | |

| Radial action black hole | Earth mass | |

| Quantity of matter (g) | 1.9891x1033 | 5.972x1027 |

| Celerity MG = roc2 (cm3sec -2) | 1.327475x1026 | 3.98576x1020 |

| Gravitational radius ro (cm) | 1.477015x105 | 0.443476 |

| Surface area = 4πro2 (cm2) | 2.74001x1011 | 2.47045 |

| Total action (Mroc) (erg.sec) | 8.80725x1048 | 7.93982x1037 |

| Number quanta NR = Mroc/ħ = S/k | 8.35136x1075 | 7.52881x1064 |

| Entropy S = NRk | 1.159299x1060 | 1.03943x1049 |

| Area/quantum = 4πro2/NR | 3.28091x10-65 | 3.28133x10-65 |

| Radius of quantum area πR2 | 3.23164x10-33 | 3.23184x10-33 |

| Mc2/kT = NR (i.e. ST=Mc2/k) | 1.32916x1075 | 1.19743x1064 |

| ST =Mc2 (ergs) | 1.78772x1054 | 5.3637x1048 |

| Quantum energy (mc2=hv) (ergs) | 2.14063x10-22 | 7.12910x10-17 |

| Radial inertia Mro (g.cm) | 2.93793x1038 | 2.64844x1027 |

| Mroc2/NR = hc (gcm3sec -2) | 1.98646x10-16 | 1.98646x10-16 |

| Mroc2 = M2G (gcm3sec -2) | 2.6440x1059 | 2.38359x1048 |

| Mean frequency (sec-1) | 2.23060x104 | 1.07591x1010 |

| Mean temperature = hc/2πrok =mc2/k (K) | 1.55138x10-6 | 0.51672 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).