Submitted:

19 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

How does ventilation and/or air cleaning influence health and/or comfort in people exposed to body odors indoors?

2.1.1. Preliminary Search

2.1.2. Relevant Article Identification and Extraction

2.1.3. Supplementary Search

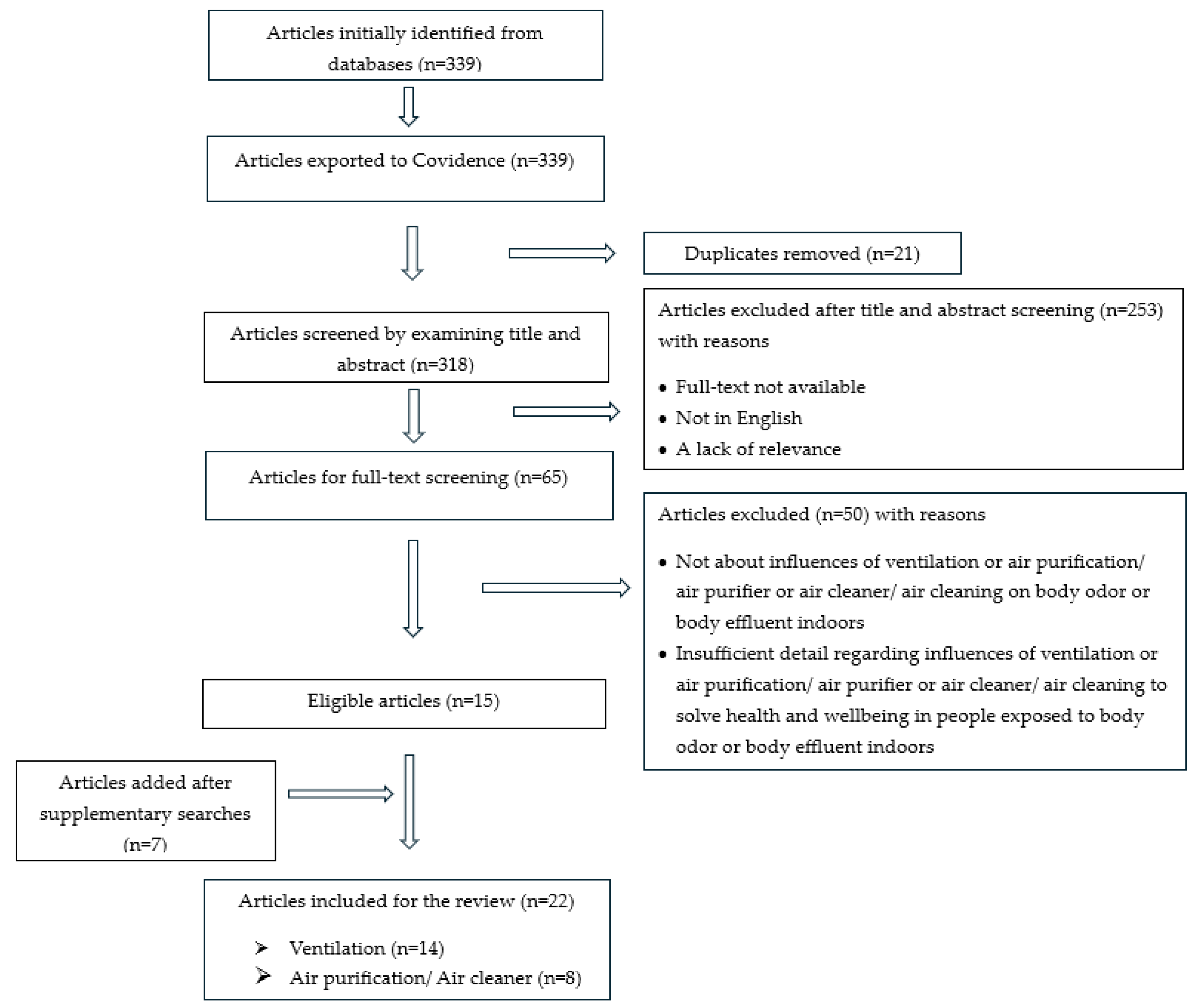

2.1.4. PRISMA Flow Diagram

2.2. Pilot study

2.2.1. Multi-Modal Air Cleaner and Test Chemical Odorants

2.2.2. Test Apparatus

2.2.3. Chemical Analysis Using Photoionisation Detection and GC-MS

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

3.1.1. Ventilation

3.1.1.1. Ventilation with Outside Air - General Dilution Ventilation

| Study | Classification | Context | Key findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of airflow interaction in the breathing zone on exposure to bio-effluents (Bivolarova et al. 2017) [37] |

Laboratory experimental study | A breathing thermal manikin with realistic female body shape was used to simulate a seated person in a full-size climate chamber. Bioeffluents released at the armpits and groin were simulated with two tracer gases nitrous oxide (N2O) and carbon dioxide (CO2). N2O and CO2 concentrations were measured continuously at the manikin's chest, at the mouth and at the nose. A ventilated cushion was used with variable local exhaust ventilation. |

The ventilated cushion was able to capture the emitted pollutants both at the groin and the armpits when the flow rate of the exhaust air was sufficiently high. The airflow of exhalation increased exposure to gaseous pollution from body sites close to the breathing zone, such as the armpits. The exposure in the case of exhalation through the nose was higher than when exhalation took place through the mouth. Breathing did not influence the exposure to gaseous pollutants emitted from the lower part of the body. Concentrations of own-body-released bio-effluents in inhaled air depends on complex airflow interactions. Removal of pollution at the location where it is generated is the first step to be applied for reduction of exposure. The combined use of source control and personalised ventilation does not always reduce and may even increase exposure to own-body-released bio-effluents. |

Well-designed source control can substantially reduce exposure to own-body-released pollution. This work builds upon previous research on seat incorporated personalized ventilation by Melikov in 2010. |

| Bed-integrated local exhaust ventilation system combined with local air cleaning for improved IAQ in hospital patient rooms (Bivolarova et al. 2016) [38] | Laboratory experimental study | Stainless-steel climate chamber furnished with a single bed to simulate a hospital patient room. Two heated dummies were used to simulate a patient and a doctor in the room The patient was lying on a bed equipped with the ventilated mattress (VM). The patient’s body was covered with either a cotton sheet or with the activated carbon fibre (ACF) material. To simulate body generated bio-effluents, ammonia gas was released from the lying dummy’s groin area. At the location of the groins, the surface area of the VM was perforated through which the contaminated air of the bed micro-environment was exhausted. The effect of the VM for reducing the exposure to body generated bio-effluents in a hospital room was determined. |

There were two modes of operation: i.e. The exhausted polluted air discharged out of the room; and the polluted air was cleaned by ACF material installed inside the mattress and recirculated back into the room. Both modes of operation efficiently reduced the generated bio-effluent in the room by about 70%. The combined use of the VM and ACF was the most efficient exposure reduction strategy, since more than 90% of the ammonia gas in the room air was removed. The separate and combined effects of the VM and ACF were considered as a local cleaning method. Reduction in the exposure to body emitted ammonia was up to 96% when the VM was operated at only 1.5 L/s and the ACF was used as a blanket. |

Further research might explore effects of body posture, bedding arrangement, human respiratory rate on the exposure reduction efficiency of the VM. The performance of the ACF applied to the cover blanket is not generalizable to other VOCs. |

| Seat-integrated localized ventilation for exposure reduction to air pollutants in indoor environments (Bivolarova et al. 2016) [39] |

Laboratory experimental study | A full-scale room and a dressed thermal manikin sitting in front of a desk were used to simulate a one person office. The chair had a ventilated cushion (VC). Tracer gases CO2 and N2O were used to simulate bio-effluents emitted by the manikin’s armpits and groin region. The pollution removal efficiency was assessed by measuring the pollution concentration in the breathing zone of the manikin and at several other locations in the room bulk air. The performance of the VC in conjunction with mixing total-volume background ventilation at 1 air change per hour (ACH) was compared with that of mixing background ventilation alone operating at 1, 1.5, 3 and 6 ACH. |

Exhausting air through the VC decreased the concentration of the tracer gases at the breathing zone and in the room. The higher the exhaust flowrate, the more the concentration was decreased. Exhausting 1.5 L/s of air through the VC at 1 ACH in the room to reduce the bioeffluents’ concentration at the breathing zone was about 65% more efficient than providing the recommended 1.5 ACH for category I IAQ in low polluting buildings. The use of VC can not only improve air quality but also may lead to energy savings due to deduced background ventilation rate. |

Several issues, related to control and optimization of the VC as well as human response remain to be studied. |

| Exposure reduction to human bio-effluents using seat-integrated localized ventilation in quiescent indoor environment (Bivolarova at al. 2016) [40] | Laboratory experimental study | A thermal manikin with a ventilated cushion (VC) in a climate chamber. The performance of the VC was assessed by measuring the pollution concentration in the breathing zone of the manikin and at 0.5 m above the head of the manikin. |

The VC can capture gaseous pollutants released from the groins and armpits. The pollutants were almost entirely exhausted by the VC when operating at 5 L/s. |

The application of VC in highly occupied spaces, e.g. cinemas, theaters, and public transport, should be considered. Energy can be saved by using such localized exhaust nears the pollution source to minimize the spread of pollutants indoors instead of ventilating the entire space. |

3.1.1.2. Local Exhaust Ventilation

| Study | Classification | Context | Key findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of a gas-phase air cleaner in removing human bio-effluents and improving perceived air quality (Akamatsu et al. 2024) [41] |

Laboratory experimental study | Two male participants (the source of bio-effluents) sat in a stainless-steel chamber, and a gas-phase air cleaner was either operational (100 m3/h) or idled. Thirteen external participants evaluated the air quality with sensory tests, and chemical analyses were performed with GC-MS and HPLC, via an adjacent test rig, and in accordance with international standards. The air cleaner had a special activated carbon filter to remove gaseous pollutants. Two temperatures (23 and 28C) were used. |

The results indicate that pollutants emitted by humans decreased when the air cleaner was operating. In addition, sensory assessments showed a decrease in odor intensity and percentage of dissatisfaction with the air cleaner operating. The removal rates for many chemicals, besides ammonia, were >50 %. Acetaldehyde, nonanal, and decanal had concentrations above the odor detection threshold at 28 ◦C when the air cleaner was not operating. The clean air delivery rates (CADR) based on chemical concentrations and PAQ varied depending on temperature. Removal rates for acetaldehyde, nonanal and decanal with the air cleaner on were >12->49%, >47->80% and >49-81% respectively. PAQ-based CADR decreased with increasing temperature. |

In spaces polluted by human emissions, passive air cleaners with activated carbon can provide a strong positive effect comparable to or even higher than ventilation with outdoor air. Future studies should focus on developing a reliable method to estimate the air-cleaner removal effect using the measured concentrations of chemical substances or sensory evaluations of air quality. Adding pollution sources, in addition to humans, could influence the performance of the air cleaner tested. |

| A method for testing the gas-phase air cleaners using sensory assessments of air quality (Amada et al. 2024) [42] | Laboratory experimental and methodological study | Portable air cleaners (PACs) with different operational principles were challenged with pollutants emitted from building materials and humans. The performance of air cleaners was examined using sensory ratings of air quality and chemical measurements and compared with the effect obtained by increasing the ventilation rate. Rooms were ventilated with outdoor air (no recirculation) using a mechanical ventilation system with filtration and kept at 23C and 30% relative humidity. Two of the 4 PACs were based on activated carbon. One was based on ion generation and one was based on UV/ozone reaction. Artificial pollution sources (old carpets and linoleum) were introduced according to a protocol. There were 2 phases: Phase 1 ensured that air cleaners had no negative effect on air quality. Phase 2 provided a detailed characterisation of the removal efficiency of air cleaners. GC-MS and HPLC methods were used. 31 panellists rated the acceptability of air quality and odour intensity immediately upon entering the rooms and of the air extracted from them and presented in diffusers. ISO 16000-44 describes a test method for measuring perceived indoor air quality for testing the performance of gas phase air cleaners. The air change rate of the test chamber was set at 0.50/h (±0.03/h) and 2.0/h (±0.12/h) |

The operation of air cleaners reduced concentrations of VOCs regardless of the pollution source. PAQ was only improved when the pollution source was building materials, supporting the necessity of inclusion of sensory ratings. Differences between the results of chemical measurements and sensory evaluations suggested that chemical analyses alone do not provide sufficient information regarding air cleaner performance. Sensory evaluations are an important part when the performance of air cleaners is documented. Differences between the whole-body and facial sensory evaluations were observed. Although acceptability and odor intensity ratings were strongly correlated, the overall results of sensory evaluations for individual conditions were not always consistent. It can be recommended to use both sensory evaluations of odor intensity and acceptability of air quality when testing the performance of air cleaners using sensory methods. The relationship between ventilation rates and sensory ratings of acceptability of air quality and odor intensity was non-linear. These relationships were different for different pollution sources. When determining the efficiency of air cleaners and comparing them against the effects obtained by ventilation, it is necessary to perform the tests at different ventilation rates. Examining the air cleaner efficiency only at one ventilation rate is insufficient, and these results should not be extrapolated to other ventilation rates. It was observed that subtractive air cleaners (based on activated carbon) performed better than additive air cleaners |

The results of a prototype method for testing gas-phase air cleaners using sensory assessment were validated, but more testing is still necessary before its full application in practice. |

| Mandating indoor air quality for public buildings: if some countries lead by example, standards may increasingly become normalized (Morawska et al. 2024) [18] | Review – Policy article | Little action has been taken on mandating IAQ standards. Indoor pollutants include body odor. Ventilation with clean air is a key control strategy for contaminants generated indoors. Outdoor air ventilation rates are almost always set according to criteria of hygiene and comfort (perceived air quality). |

A numerical ventilation value is suggested, along with other criteria for regulated IAQ. 14L/sec per person of clean air in the breathing zone when the space is occupied. Air cleaning can be used to reduce the volume of outside air, which has a substantial energy penalty. Work is ongoing to develop consensus methods for determining the effectiveness of some of the air cleaning technologies. |

The suggested ventilation rate is based on infection risk for school children. |

| The Concept for Substituting Ventilation by Gas Phase Air Cleaning (Olesen et al. 2020) [43] |

Review | Gas phase air cleaning technologies are increasingly being used to improve IAQ. Such cleaners are tested based on a chemical measurement, which does not account for the influence on PAQ and human bio effluents as a source of pollution. The pros and cons of partly substituting required ventilation by gas phase air cleaning should be discussed. |

ASHRAE 62.1 allows credit for air cleaning but requires that the cleaning efficiency for individual substances has been tested according to an existing test standard. Testing based on subjective PAQ should also allow for relaxation of outside air ventilation rates. ISO (ISO 10121-2:2013) and ASHRAE (145.2-2016) include standard test methods but better test methods are required, since PAQ is not assessed. In the case of one air cleaner PAQ was made worse when challenged with body effluents. It is important to specify which kind of “pollutants” should be used when testing It may be possible to assess air cleaner performance based on an increase in the IAQ level based on international standards. It must be verified that the reduced ventilation rate is still high enough to dilute individual contaminants. |

A number of issues (e.g. testing standards, energy impacts) should be considered when ventilation is partially substituted by air cleaning. |

| Experimental analysis of indoor air quality improvement achieved by using a Clean-Air Heat Pump (CAHP) air-cleaner in a ventilation system (Sheng et al. 2017) [44] | Field laboratory experiment | Clean air heat pump (CAHP) is a new technology that combines air cleaning with hygro-thermal control of ventilation air. In CAHP, a regenerative desiccant wheel was used for moisture control and air cleaning. The study used a test room in an office building with a ventilation system including a CAHP (silica gel rotor) and an outdoor air handling unit. Students were used as subjects, and were deemed as the major source of air pollutants. There was variable outdoor air supply (up to 20L/sec person), with the CAHP operating only at 2L/sec per person. These experimental conditions were designed to determine which outdoor air supply rate was equivalent to the effective clean air delivery rate from the CAHP. VOCs were continuously monitored with a photoacoustic infrared detector when the CAHP was operating. Sensory assessments of PAQ and chemical measurements of total VOC concentration were used to evaluate the air-cleaning performance. |

The operation of CAHP significantly improved PAQ in a room polluted by both human bio-effluents and building materials. At the outdoor airflow rate of 2 L/s per person, IAQ with CAHP was equivalent to what was achieved in the same room with 10 L/s per person of outdoor air ventilation without air cleaning. The percentage dissatisfied was as low as 5.2% with the CAHP in operation, based on adapted perception assessment. VOCs were effectively removed by CAHP. CAHP system can be widely applied to auditoriums, classrooms and offices. |

In this study, the adapted perception of air quality by occupants was used, which is different from most other studies which also used visitors. The method of adapted perception of the air quality is stipulated in ASHRAE Standard 62.1:2013 “Ventilation for acceptable indoor air quality” to determine the required ventilation rate. The results are limited to the specific conditions. The impact of the regeneration air temperature on the air cleaning performance of the CAHP requires further study. |

| Can commonly-used fan-driven air cleaning technologies improve indoor air quality? A literature review (Zhang et al. 2011) [23] | Review | Air cleaning techniques have been applied worldwide with the goal of improving IAQ. A multidisciplinary panel of experts reviewed the scientific literature to summarise what is known regarding the effectiveness of air cleaning technologies. Clean air delivery rate represents a common benchmark for comparing the performance of different air cleaning technologies. |

133 articles were finally selected for detailed review. None of the reviewed technologies were able to effectively remove all indoor pollutants. Some air cleaners are largely ineffective, and some produce harmful by-products. Sorption of gaseous pollutants were among the most effective air cleaning technologies, but there is insufficient information regarding long-term performance and proper maintenance. There should be a labelling system accounting for characteristics such as CADR, energy consumption, volume, harmful by-products, and life span. Therefore, a standard test room and condition should be built and studied. Pollutant removal efficiency is determined in controlled laboratory environments. Further research in real-world settings is needed. Although there is evidence that some air cleaning technologies improve IAQ, further research is needed before any of them can be confidently recommended for use in indoor environments. |

The authors suggest that the question “Can commonly used fan-driven air cleaning technologies improve IAQ?” does not yet have an answer. Although detailed, it refers to a limited set of air cleaning technologies available at the time. |

| Can a photocatalytic air purifier be used to improve the perceived air quality indoors? (Kolarik & Wargocki 2010) [45] | Field laboratory experiment | Typical indoor pollution sources were placed in the test rooms adapted from ordinary offices. The photocatalytic air purifier used had seven TiO2 honeycomb catalyst plates and UV lamps The air quality in rooms was assessed by a sensory panel of 50 students when the purifier was in operation as well as when it was off. |

The operation of purifier improved PAQ in test rooms polluted by building materials. Operation of the purifier significantly worsened the PAQ in rooms with human bio-effluents. The purifier can supplement ventilation when the indoor air is polluted by building related sources but should not be used in spaces where human bio-effluents constitute the main source of pollution. The effect of the purifier expressed in CADR depended on the type of pollution source. |

This paper builds on a similar paper by Kolarik, Wargocki et al, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2009.12.006) describing the same prototype air purifier, and performance assessed with sensitive chemical detection methods. In that study, the results suggest that both sensory assessments and sensitive chemical analysis should be used for examining changes of air quality. |

| Desiccant wheels as gas-phase absorption (GPA) air cleaners: evaluation by PTR-MS and sensory assessment (Fang et al 2008) [46] | Multi-experimental study |

Desiccant materials are a subset of sorbents that are normally used for dehumidification. Previous studies showed that they can also be used to remove gases other than water vapor from air. This paper presents two experiments that studied the performance of a silica gel desiccant wheel for removing indoor air pollutants, and discusses the possibility of its application in improving indoor air quality, reducing ventilation requirements and energy consumption. VOCs used to challenge the wheel were at realistic low levels found in normal non-industrial indoor environments. Three types of pollution source were used: flooring materials, human bioeffluents, and pure chemicals. In the first experiment human bioeffluents were emitted by 17 subjects sitting in a chamber. The pure chemicals introduced were formaldehyde, ethanol, toluene, and 1,2-dichloroethane. The air-cleaning effect of a desiccant wheel on each of the three pollution sources was tested individually. In the second experiment 3 subjects were in an office room working at a moderate metabolic rate. Sensory assessments were made by a group of 30 untrained subjects. |

The desiccant wheel reduced the concentrations of VOCs from all three types of challenge pollution sources. In terms of perceived air quality, high dissatisfaction was found when the dehumidifier was bypassed from the recirculation system but dropped to acceptable levels when the dehumidifier was connected. This result was observed for all the three conditions where the air was polluted by three different pollution sources. Up to 80% of the sensory pollution load was removed by a desiccant wheel, leading to a reduction of the ventilation requirement for comfort by 80%. |

This was an elaborate pair of experiments with both PAQ and chemical concentration testing using advanced detection methods. However, further studies are needed on how to incorporate the air-cleaning effect of a regenerative desiccant wheel with the design of dehumidification in a ventilation system. |

3.1.2. Air Cleaning

3.1.3. Evidence Synthesis

3.2. Pilot Experimental Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3MHA | trans-3-methyl-2-hexenoic acid |

| GC-MS | gas chromatography with mass spectrometry |

| CADR | clean air delivery rate |

| HMHA | 3 hydroxy-3-methylhexanoic acid |

| HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation and air conditioning |

| LEV | local exhaust ventilation |

| PAQ | perceived air quality |

| PID | photoionisation detection |

| SVOC | semi-volatile organic compound |

| VOC | volatile organic compound |

References

- Morawska, L; Marks, G. B. &Monty, J. Healthy indoor air is our fundamental need: The time to act is now. Med J Aust. 2022, 217, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, J.E. & Shusterman, D. Health effects of indoor odorants. Environmental Health Perspectives 1991, 95, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppanen, O.A. & Fisk, W.J. Summary of human responses to ventilation. Indoor Air 2004, 14, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, P.; Claeson, A.-S.; Horenziak, S. The impact of indoor malodor: historical perspective, modern challenges, negative effects, and approaches for mitigation. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Schiavon, S. & Wargocki, P.; Tham, K.W. Respiratory performance of humans exposed to moderate levels of carbon dioxide. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1540–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, T.; Schiavon, S.; Kim, J. & Betti, G. Common sources of occupant dissatisfaction with workspace environments in 600 office buildings. Buildings and Cities. 2023, 4, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainland, J.; Keller, A.; Li, Y.; et al. The missense of smell: functional variability in the human odorant receptor repertoire. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimmer, C.; Keller, A.; Murphy, N.R.; Snyder, L.L; Willer, J.R.; Nagai, M.H.; Katsanis, N.; Vosshall. L.B.; Matsunami, H. & Mainland, J.D. Genetic variation across the human olfactory receptor repertoire alters odor perception. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019, 116, 9475–9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, Sunil Kr. Characterization of human body odor and identification of aldehydes using chemical sensor. Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2017, 36, 20160028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persily, A. Challenges in developing ventilation and indoor air quality standards: The story of ASHRAE Standard 62. Build. Environ. 2025, 91, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Muller, T.; Ernle, L; Beko, G. ; Wargocki, P. & Williams, J. How does personal hygiene influence indoor air quality? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 9750–9759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanger, P.O. Introduction of the olf and the decipol units to quantify air pollution perceived by humans indoors and outdoors. Energy and Buildings 1988, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg-Munch, B.; Clausen, G. & Fanger, P.O. Ventilation requirements for the control of body odor in spaces occupied by women. Environ. Int. 1986, 12, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, K. Microbial Origins of Body Odor. American Society for Microbiology, 2021 Available online URL https://asm.org/articles/2021/december/microbial-origins-of-body-odor (accessed 12/10/2025).

- Beko, G.; Wargocki, P.; Wang, N.; Li, M.; Weschler, C.J.; Morrison, G.; Langer, S.; Ernle, L.; Licina, D.; Yang, S.; Zannoni, N. & Williams, J. The indoor chemical human emissions and reactivity (ICHEAR) project: Overview of experimental methodology and preliminary results. Indoor Air 2020, 30, 1213–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.; Yesildagli, B.; Kwon, J.H. & Lee, J. Comparative analysis of indoor volatile organic compound levels in an office: Impact of occupancy and centrally controlled ventilation. Atmospheric Environment 2025, 345, 121057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beko, G.; Wargocki, P.; Duffy, E.; Zhang, Y.; Hopke, P.K. & Mandin, C. Occupant emissions and chemistry. In Handbook of Indoor Air Quality. Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp 903–929. [CrossRef]

- Morawska, L; Allen, J. ; Bahnfleth, W.; Bennett, B.; Bluyssen, P.M.; Boerstra, A … Yao, M. Mandating indoor air quality for public buildings: If some countries lead by example, standards may increasingly become normalized. Science 2024, 383, 1418–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Qu, M.; Sun, L; Wang, X. & Yin, Y. The relationship between indoor air quality (IAQ) and perceived air quality (PAQ) – a review and case analysis of Chinese residential environment. Energy and Built Environment 2024, 5, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargocki, P. What we know and should know about ventilation. In The CLIMA 2019 Conference, Bucharest, Romania, 2019. Available online: https://www.rehva.eu/rehva-journal/chapter?tx_wbjournals_chapterdetail%5Baction%5D=download&tx_wbjournals_chapterdetail&5Bchapter%5D=814&tx_wbjournals_chapterdetail%5Bcontroller%5D=Chapter&cHash=c6bb048d8da7993d7cfb0a0e07261ecc (accessed 12/10/2025).

- Wu, T.D. Portable air purifiers to mitigate the harms of wildfire smoke for people with asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2024, 209, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standards Australia. Australian Standard 1668.2-2024. The use of ventilation and airconditioning in buildings. Part 2 Mechanical ventilation in buildings. 2024 Sydney, Australia. Available online: https://www.standards.org.au/blog/spotlight-on-as-1668-2024 (accessed 12/10/25).

- Zhang, Y.; Mo, J.; Li, Y.; Sundell, J.; Wargocki, P.; Zhang, J.; Little, J.C.; Corsi, R.; Deng, Q.; Leung, M.H.; Fang, L.; Chen, W.; Li, J. & Sun, Y. Can commonly-used fan-driven air cleaning technologies improve indoor air quality? A literature review Atmos Environ 2011, 45, 4329–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadegh, F.; Sadegh, N.; Wongniramaikul, W.; Apiratikul, R. & Choodum, A. Adsorption of volatile organic compounds on biochar: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 182, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X; Misztal, P. K.; Nazaroff, W.W. & Goldstein AH. Volatile organic compound emissions from humans indoors. Environ Sci Technol. 2016, 50, 12686–12694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irga, P.J.; Mullen, G.; Fleck, R.; Matheson, S.; Wilkinson, S.J.; Torpy, F.R. Volatile organic compounds emitted by humans indoors – A review on the measurement, test conditions, and analysis techniques 2024. Build. Environ. 2024, 255, 111442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisaniello, D.; Parker, M.; Neupane, V.; Gaskin, S.; Ramkissoon, C. Mitigation of individual odorous bushfire smoke semi-volatile organic compounds using multi-modal air purifiers. Ecolibrium 2025 pp. 50–53. Available online: https://plasmashield.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/ecolibrium-23-6-bushfire-odour-removal-peer-reviewed-article.pdf (accessed on day month year).

- Tefera, Y. M.; Thredgold, L.; Pisaniello, D. & Gaskin, S. The greenhouse work environment: A modifier of occupational pesticide exposure? J. Environ. Sci. Health., Part B 2019, 54, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska, L.; Li, Y,; Salthammer, T. Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for ventilation and indoor air quality. Science 2024, 385, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermeyer, L, Harnke, B. ; Knight S. Covidence and Rayyan. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018, 106, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiley, H.; Keerthirathne, T.P.; Kuhn, E.J.; Nisar, M.A.; Sibley, A.; Speck, P.; Ross, K.E. Efficacy of the PlasmaShield®, a non-thermal plasma-based air purification device, in removing airborne microorganisms. Electrochem 2022, 3, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisaniello, D. & Nitschke, M. Relative health risk reduction from an advanced multi-modal air purification system: evaluation in a post-surgical healthcare setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2024, 21, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsch, A.; Derrer, S.; Flachsmann, F.; Schmid, J. A broad diversity of volatile carboxylic acids, released by a bacterial aminoacylase from axilla secretions, as candidate molecules for the determination of human-body odor type. Chem Biodivers. 2006, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASHRAE 2016. ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 145.2-2016 Laboratory test method for assessing the performance of gas-phase air-cleaning systems: air-cleaning devices. Available online: https://webstore.ansi.org/standards/ashrae/ansiashraestandard1452016?srsltid=AfmBOopKVaeXEHJOiKY_LaVaIlxLUGg30w5u4Ev8wY4p3YnNXJtVwf27 (accessed on day month year).

- Zhang, X.; Wargocki, P.; Lian, Z.; Xie, J.; & Liu, J.; Liu, J. Responses to human bioeffluents at levels recommended by ventilation standards. Procedia Engineering 2017, 205, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parine, N. The use of odour in setting ventilation rates. Indoor Environ. 1994, 3, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivolarova, M.P.; Kierat, W.; Zavrl, E.; Popiolek, Z. & Melikov, A. Effect of airflow interaction in the breathing zone on exposure to bio-effluents. Build. Environ. 2017, 125, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivolarova, M.P.; Melikov, A.K.; Mizutani, C.; Kajiwara, K. & Bolashikov, Z.D. Bed-integrated local exhaust ventilation system combined with local air cleaning for improved IAQ in hospital patient rooms. Build. Environ. 2016, 100, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivolarova, M.P.; Rezgals, L.; Melikov, A.K. & Bolashikov, Z.D. Seat-integrated localized ventilation for exposure reduction to air pollutants in indoor environments. In Proceedings of 9th International Conference on Indoor Air Quality Ventilation & Energy Conservation in Buildings, Seoul, Korea, 2016. Available online: https://orbit.dtu.dk/files/127944087/Seat_integrated_localized_ventilation_for_exposure_reduction_to_air_pollutants_in_indoor_environments.pdf (accessed 12/10/2025).

- Bivolarova, M.P.; Rezgals, L.; Melikov, A.K. & Bolashikov, Z.D. Exposure reduction to human bio-effluents using seat-integrated localized ventilation in quiescent indoor environment. In Proceedings of the 12th Rehva World Congress, Aalborg, Denmark 2016. Available online: https://orbit.dtu.dk/files/127945761/Exposure_reduction_to_human_bio_effluent_using_seat_intergrated_localized_ventilation.pdf (accessed 12/10.2025).

- Akamatsu, N.; Sugano, S.; Amada, K.; Tomita, N.; Iwaizumi, H.; Takeda, Y.; & Tanabe, S.; Tanabe, S. Effects of a gas-phase air cleaner in removing human bioeffluents and improving perceived air quality. Build. Environ. 2024, 257, 111540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amada, K.; Fang. ; Vesth, S.; Tanabe, S.; Olesen, B. W.; & Wargocki, P. A method for testing the gas-phase air cleaners using sensory assessments of air quality. Build. Environ. 2024, 259, 111630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, B.W.; Sekhar, C.; Wargocki, P. The Concept for Substituting Ventilation by Gas Phase Air Cleaning. In 16th Conference of the International Society of Indoor Air Quality and Climate: Creative and Smart Solutions for Better Built Environments. Indoor Air 2020. Available online: https://www.aivc.org/resource/vip-42-concept-substituting-ventilation-gas-phase-air-cleaning (accessed on day month year).

- Sheng, Y.; Fang, L. & Nie, J. Experimental analysis of indoor air quality improvement achieved by using a Clean-Air Heat Pump (CAHP) air cleaner in a ventilation system. Build. Environ. [CrossRef]

- Kolarik, J. & Wargocki, P. Can a photocatalytic air purifier be used to improve the perceived air quality indoors? Indoor Air 2010, 20, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Zhang, G.; Wisthaler, A. Desiccant wheels as gas-phase absorption (GPA) air cleaners: evaluation by PTR-MS and sensory assessment. Indoor Air 2008, 18, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACGIH. Industrial Ventilation: A Manual of Recommended Practice for Design, 31st ed.; American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists: Cincinnati OH, 2023 ISBN: 978-1-607261-61-2.

- Shaughnessy, R.J.; Levetin, E.; Blocker, J. & Sublette, K.L. Effectiveness of portable indoor air cleaners: sensory testing results. Indoor Air 1994, 4, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Classification | Context | Key findings | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative analysis of indoor volatile organic compound levels in an office: Impact of occupancy and centrally controlled ventilation (Joo et al. 2025) [16] | Field study | Investigation of VOCs in an office with variable occupancy and ventilation across two seasons. The building was not new, and had an office window which was not opened. |

Real time monitoring of 113 indoor VOCs and occupancy and ventilation assessment demonstrated that 77.8% of the total VOC emission rate was attributed to human occupancy, 12.9% to building sources, and 9.30% to supply air. Introduction of 50% outside air reduced the total concentration of indoor VOCs. Ventilation was immediately effective in reducing the indoor VOCs. |

Ventilation strategies have a critical role in maintaining IAQ and sustaining occupant health. |

| The relationship between indoor air quality (IAQ) and perceived air quality (PAQ) – a review and case analysis of Chinese residential environment (Pei et al. 2024) [19] | Review | Considers PAQ evaluation methods based on objective measurement of indoor parameters and occupants’ subjective perception | Traditional IAQ evaluation method mainly compares with threshold, while PAQ evaluation method considers the occupants comfort and sensation. Indoor VOCs are major PAQ factors through olfactory and sensory irritation. Building ventilation can improve PAQ by diluting or removing indoor air pollutants. |

More attention should be paid to specific pollutants with low odor and sensory thresholds when evaluating air quality perception. |

| What we know and should know about ventilation (Wargocki 2019) [20] |

Review | Insights into ventilation, with key questions around amounts, criteria, the use of epidemiology and ventilation as an IAQ metric. | Air quality and ventilation requirements can based on the percentage of visitors dissatisfied with the air quality upon entering the space or on the acceptability for both visitors and occupants. Substandard ventilation in homes will result in an increased burden of disease. Ventilation requirements in buildings occupied by people need to be followed strictly. Particular consideration should be given to people with special needs |

More research and a new paradigm and a framework for ventilation requirements in buildings are required. |

| Responses to Human Bioeffluents at Levels Recommended by Ventilation Standards (Zhang et al. 2017) [35] | Laboratory experimental study | Ten subjects were exposed in a low-emission stainless-steel climate chamber for 4.25 hours. The outdoor air supply rate was set to 33 or 4 l/s per person, creating two levels of bioeffluents. Subjective ratings were collected, cognitive performance was examined and physiological responses were monitored. |

Exposures to human bioeffluents at ventilation rate of 4 l/s per person caused sensory discomfort of visitors, reduced pNN50 (a domain of ECG measurement), but did not produce negative effects on cognitive performance or health symptoms. | VOCs were not measured, but carbon dioxide was monitored. The authors suggested that future studies focus on exposure to moderate-to-low levels of human bioeffluents. |

| Challenges in developing ventilation and indoor air quality standards: The story of ASHRAE Standard 62 (Persily 2015) [10] |

Review | Discussed the development of ventilation standards |

The first version of ASHRAE Standard 62 was published in 1973. Since that time, ventilation standards have been issued in several countries and have dealt with IAQ. The development of ventilation and IAQ standards has progressed significantly since the first ventilation standard. |

Investigations relating to health effects of contaminants, contaminant mixtures, source strengths and the performance of IAQ control technologies are needed. |

| Summary of human responses to ventilation (Seppanen & Fisk 2004) [3] | Review | Human response to indoor air pollutant mitigation by ventilation rate | Ventilation can remove indoor-generated pollutants from indoor air or dilute their concentration to acceptable levels. Higher ventilation reduces the prevalence of air-borne infectious diseases. Ventilation rates below 10 L/sec person are associated with a significantly worse prevalence of one or more health or PAQ outcomes. A ventilation rate above 10 L/sec person, up to 20 L/sec person, is associated with a significant decrease in the prevalence of sick building syndrome (SBS) symptoms or with improvements in PAQ. Improved ventilation can improve task performance and productivity. As the limit values of all pollutants are not known the exact determination of required ventilation rates based on pollutant concentrations is seldom possible. Better hygiene, commissioning, operation and maintenance of air handling systems may be particularly important for reducing the negative effects of HVAC systems. |

Limitations in existing data make it essential that future studies better assess health, productivity and PAQ changes in the ventilation rate range between 10 and 25 L/ sec person in office-type environments. The selection of ventilation rates has to be based also on epidemiological research, laboratory and field experiments and experience. Future research should be based on well-controlled cross-sectional studies or well-designed blinded and controlled experiments. |

| The Use of Odour in Setting Ventilation Rates (Parine 1994) [36] | Review | The perception of human odor has been used to set standards for ventilation rates in buildings. Building related odors are also important. |

Experiments carried out to determine the minimum acceptable ventilation rates have been determined in ’artificial’ situations. Some real-world field studies have found little occupant response to changes in ventilation. What is not clear is the actual level of odors in buildings and what level is acceptable. Aversion to odors may be learnt. The linearity between the decipol and olf units has been questioned. Comparisons of the results of different studies are difficult, as each study has used different scales. |

More research in real buildings on how odor annoyances combine is required. Greater understanding how occupants and visitors respond to odors is needed. |

| Health Effects of Indoor Odorants (Cone & Shusterman 1991) [2] | Review | Odorants may be considered as ‘pathogenic messengers” of ventilation systems. |

The are many contributors to odor in buildings, including building materials, ventilation system, occupant activities and body odor. This review considers various odor sources and potential health effects, with case studies. Methods of odor assessment are described, but the total odorant problem is hard to assess. |

People assess the quality of the air indoors primarily on the basis of its odor, and on their perception of associated health risk". Setting ventilation standards to prevent health effects due to indoor air pollution is important. |

| Introduction of the olf and the decipol units to quantify air pollution perceived by humans indoors and outdoors (Fanger 1988) [12] |

Review and method development | Description of a new method to assess odors |

The “olf” or “decipol” unit can be useful to assess biological odorants in indoor air. One “olf” is defined as the emission rate of air pollutants (bioeffluents) from a standard person. One “decipol” is the pollution caused by one oil, ventilated by 10 l/s of unpolluted air. |

The units provide a rational basis for the identification of pollution sources. They can be used to calculate ventilation requirements and predict and measure IAQ. |

| Ventilation requirements for the control of body odor in spaces occupied by women (Berg-Munch et al. 1986) [13] |

Experiments in an auditorium. | Mechanical ventilation (ceiling to floor). High and low ventilation rates Female occupants with male and female visitors Visitors were questioned concerning the acceptability of body odor in the occupied auditorium and were also asked to evaluate the odor intensity on the Yaglou psycho-physical scale (no odor to overpowering odor). |

In a space occupied by sedentary persons a steady-state ventilation rate of 8 L/sec person was required in order to satisfy 80% of people entering the space (visitors). There are no substantial differences in the ventilation rates required to control body odor in spaces occupied by women and by men. Occupants adapt to body odor and are less dissatisfied than the visitors. The percentage of dissatisfied occupants was independent of the ventilation rate. |

This study builds on previous research in 1983 and the studies by Yaglou in 1936. |

| Odor source | Air cleaner removal efficiency determined by PID * | Air cleaner removal efficiency, determined by GC-MS (% and % range) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylic acids | Propanoic acid | feet | 99% | 75% (n=3; 64-80) |

| 3-methylbutanoic acid | feet | 95% | 89% (n=3; 88-90) | |

| 3MHA | underarm | - | 73% (n=3; 61-77) | |

| HMHA | underam | - | 89% (n=2; 88-89) | |

| Aldehydes | Acetaldehyde | breath | 99% | - |

| Nonanal | skin, hair underarm | 99% | - | |

| Decanal | Skin, hair underarm | 97% | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).