Submitted:

14 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We propose a novel GNN-based environment intent perception module for real-time prediction of multi-modal behaviors and associated risks of dynamic obstacles.

- We integrate learned dynamic risk assessment with a classical spline curve generator, employing a DRL-trained scoring network for online trajectory selection.

- We construct a comprehensive simulated dataset, UrbanSense-Dynamic, featuring diverse low-speed dynamic scenarios, and provide detailed experimental validation and ablation studies.

2. Related Work

2.1. Advanced Trajectory Planning for Autonomous Driving

2.2. Deep Learning for Dynamic Environment Perception and Decision Making

3. Method

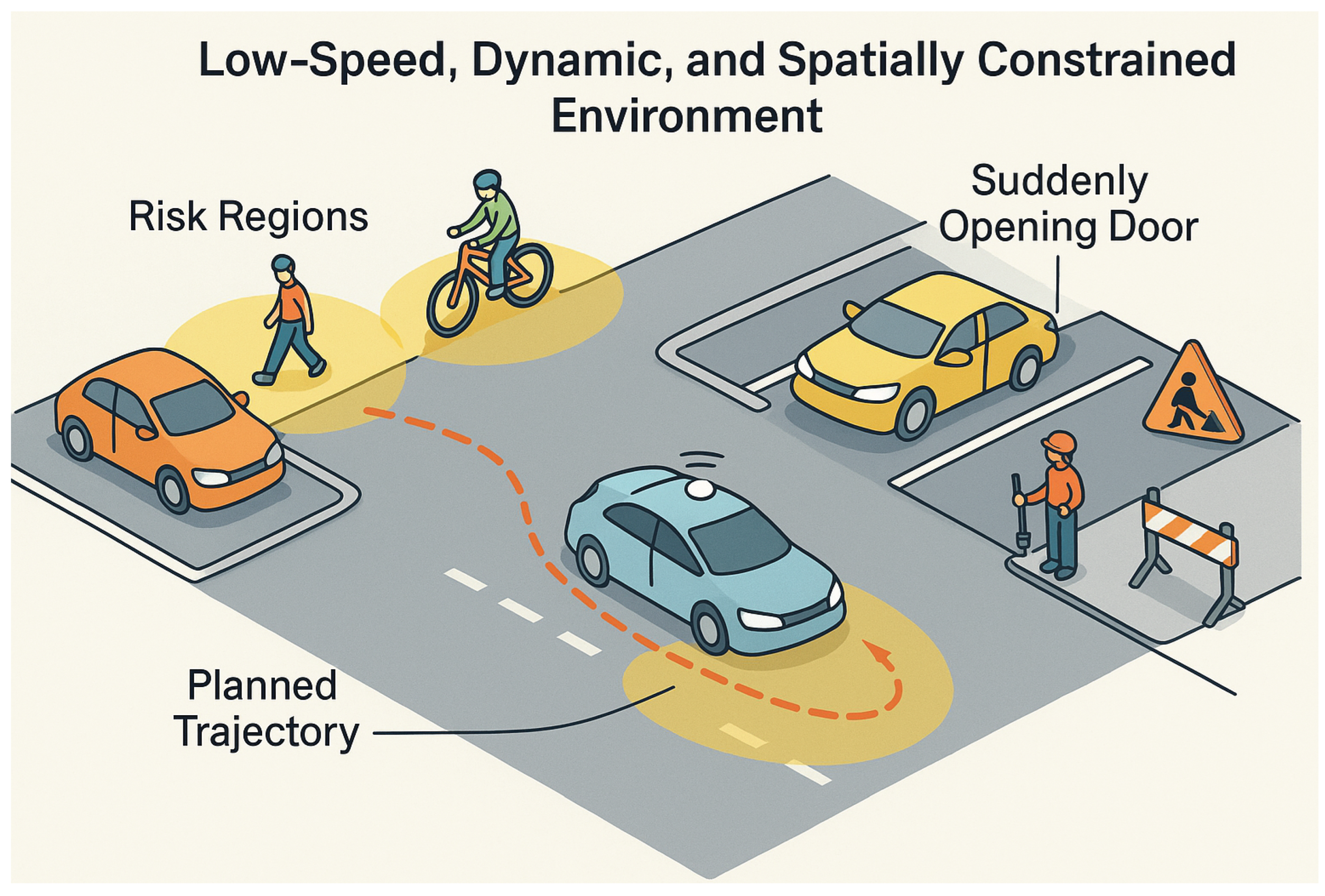

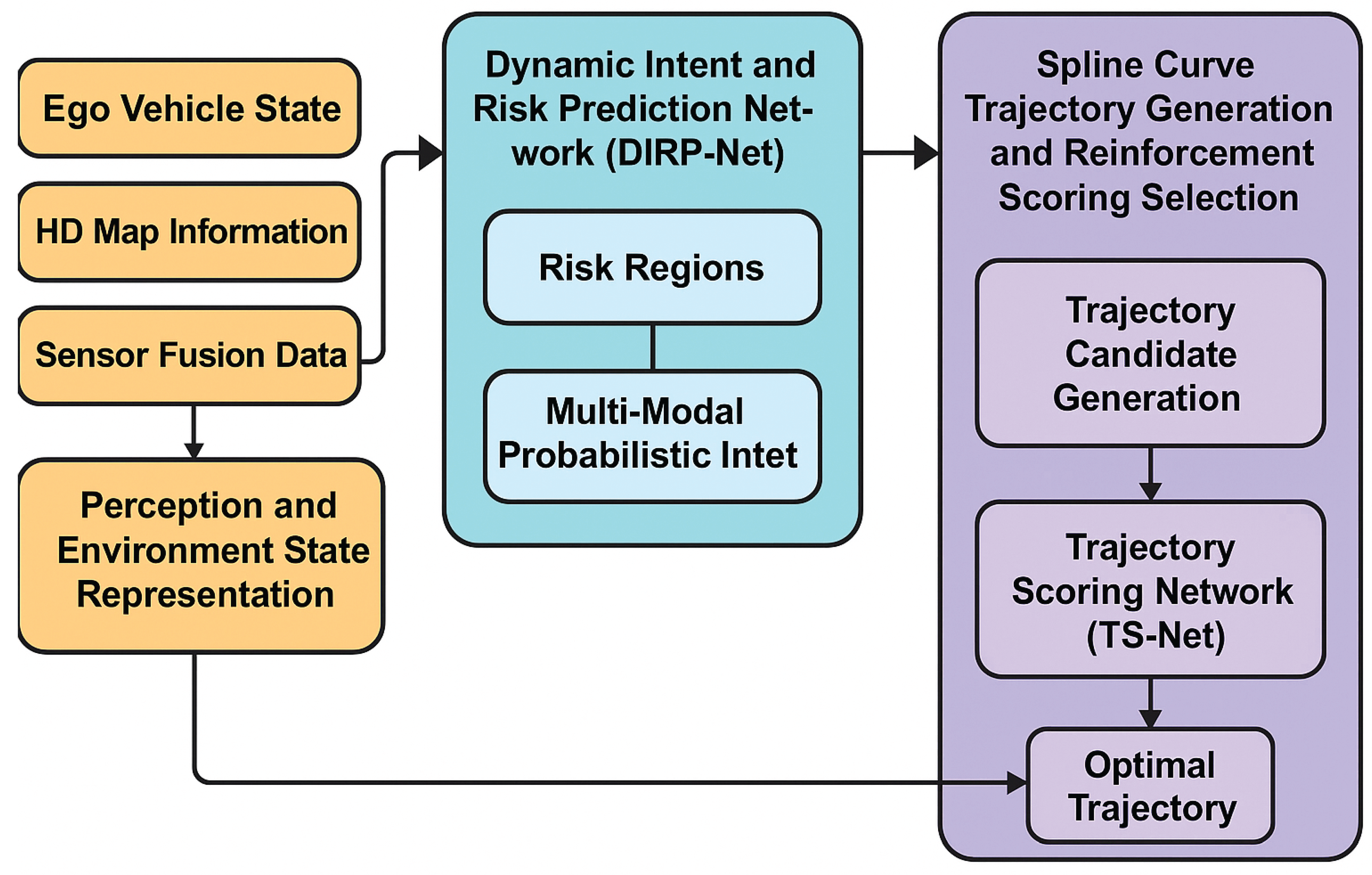

3.1. System Architecture (DL-ALP)

3.1.1. Perception and Environment State Representation

3.2. Dynamic Intent and Risk Prediction Network (DIRP-Net)

3.3. Spline Curve Trajectory Generation and Reinforcement Scoring Selection

3.3.1. Trajectory Candidate Generation

3.3.2. Trajectory Scoring Network (TS-Net)

3.3.3. Optimal Trajectory Selection

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Metrics

4.1.1. Datasets

- UrbanSense-Dynamic (Simulated Dataset): As described in the research summary, this is a large-scale simulated dataset specifically constructed for this work. It comprises 8,000 short trajectory scenarios (each 10–25 seconds long), meticulously designed to cover a wide variety of typical low-speed complex scenes. These include multi-story and open-air parking lots (featuring parking, unparking, and spot-seeking maneuvers), residential alleys (involving low-speed traversal, pedestrian avoidance, and oncoming traffic negotiation), and construction zones (characterized by narrow passages, temporary obstacles, and active construction personnel). The dataset is split into 5,600 scenarios for training, 1,200 for validation, and 1,200 for testing. It incorporates diverse traffic densities (low, medium, high) and a rich array of dynamic obstacle types (pedestrians with varied behaviors, cyclists, e-scooters, and other vehicles with complex interaction patterns like sudden turns, acceleration, and deceleration). Sensor noise models are also integrated to mimic real-world sensor imperfections.

- Small-Scale Real-World Recordings: This dataset consists of 150 real low-speed scenario recordings collected in a university campus and small commercial areas using onboard vehicle sensors. These recordings were exclusively used for testing the generalization ability of DL-ALP and did not participate in any training or validation processes.

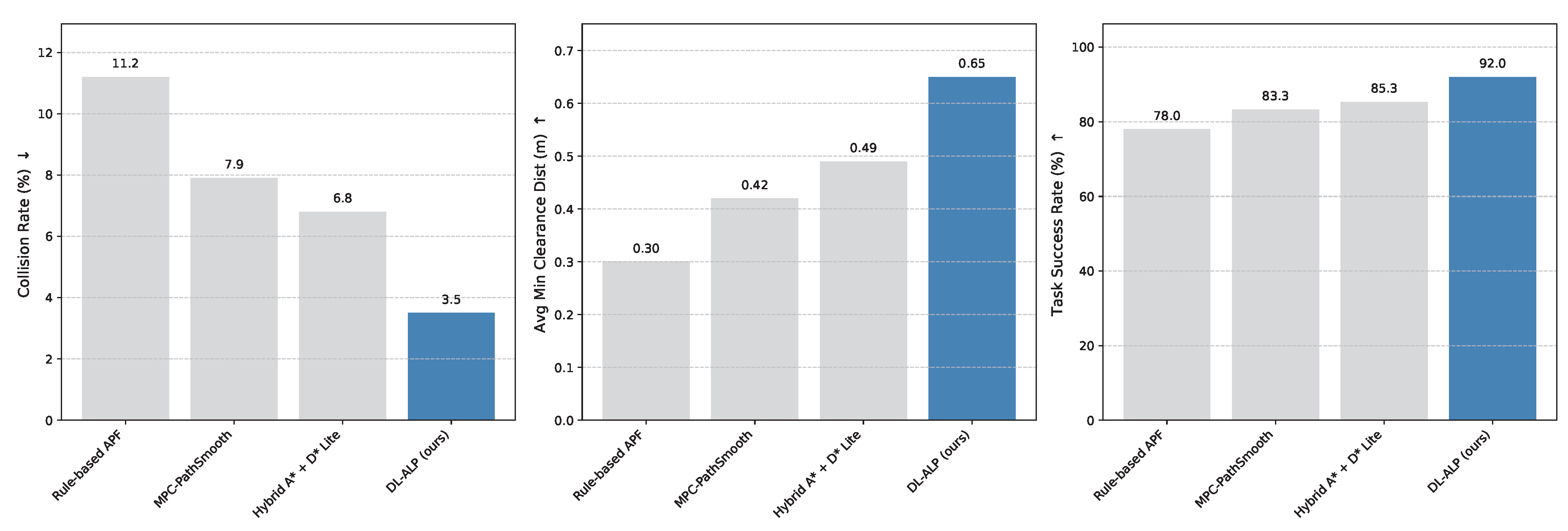

4.1.2. Baseline Methods

- Rule-based APF: A traditional Artificial Potential Field method [3] that relies on manually tuned parameters for static and dynamic obstacle potential fields.

- MPC-PathSmooth: A Model Predictive Control-based local optimizer [4] that utilizes a fixed cost function primarily focused on trajectory smoothness and deviation from a reference path, without learned risk estimation.

- Hybrid A* + D* Lite: A classical sampling-search hybrid planner [5] that combines global search with dynamic replanning capabilities. Its risk assessment, however, remains based on pre-defined rules rather than learned predictions.

- DL-ALP (ours): The proposed method, which integrates the DIRP-Net for dynamic intent and risk prediction with a spline curve generator and a DRL-trained TS-Net for trajectory scoring and selection.

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

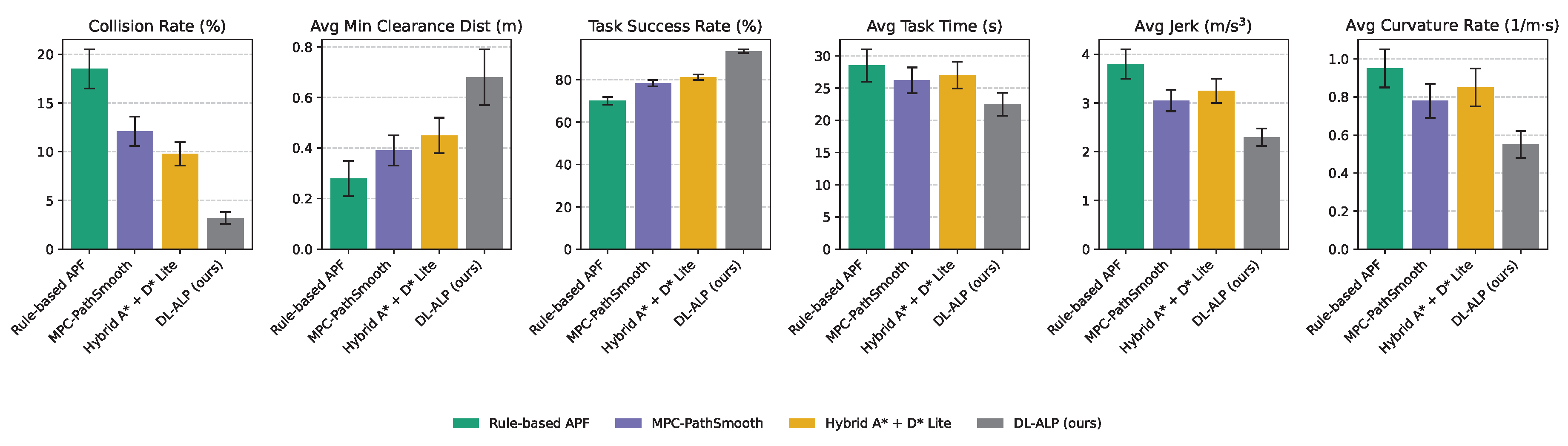

- Collision Rate (%): The percentage of test scenarios where the ego vehicle collides with any obstacle. Lower values indicate better safety.

- Average Minimum Clearance Distance (m): The average of the minimum distance maintained between the ego vehicle and any obstacle during trajectory execution across all scenarios. Higher values indicate greater safety margins.

- Task Success Rate (%): The percentage of scenarios where the predefined task (e.g., successful parking, traversing a narrow passage) is completed within a specified time limit, without collisions or boundary violations.

- Average Task Completion Time (s): The average time taken to complete the assigned task in each scenario. Lower values indicate higher efficiency.

-

Average Trajectory Smoothness: Measured by two sub-metrics:

- Average Jerk (m/s3): The average absolute value of the vehicle’s jerk (rate of change of acceleration). Lower values indicate greater driving comfort.

- Average Curvature Rate (1/m·s): The average absolute rate of change of curvature. Lower values indicate smoother steering maneuvers and higher comfort.

4.2. Performance on UrbanSense-Dynamic Test Set

4.3. Generalization to Real-World Scenarios

4.4. Ablation Study of Key DL-ALP Components

- DL-ALP w/o DIRP-Net: In this variant, the DIRP-Net module for dynamic intent and risk prediction is replaced by a simplified, rule-based dynamic obstacle potential field. This field generates risk values solely based on proximity and relative velocity, without considering complex interaction patterns or probabilistic intents.

- DL-ALP w/o DRL Weights: This variant uses the full DIRP-Net and trajectory generation, but the adaptive weighting coefficients () in the TS-Net cost function are fixed to empirically tuned constant values instead of being dynamically learned by the DRL policy.

4.5. Performance in High-Density Dynamic Environments

4.6. Computational Performance Analysis

5. Conclusion

References

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, K.; Dong, Z.; Ye, K.; Zhao, X.; Wen, J.R. StructGPT: A General Framework for Large Language Model to Reason over Structured Data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023; pp. 9237–9251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Q.; Wu, W.; Chen, E. Incorporating Dynamic Semantics into Pre-Trained Language Model for Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022; pp. 3599–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembessis, V.E. Evanescent Artificial Gauge Potentials for Neutral Atoms. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1310.7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Dong, L.; Shen, Y.; Wei, F.; Chen, W. Controllable Natural Language Generation with Contrastive Prefixes. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022; pp. 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Vandyke, D.; Wang, S.; Fang, Y.; Collier, N. Plan-then-Generate: Controlled Data-to-Text Generation via Planning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tian, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Lin, Z. Adaptive Field Effect Planner for Safe Interactive Autonomous Driving on Curved Roads. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.14747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Lin, Z.; Tian, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhou, Q.; Yuan, C.; Sun, H.; Huang, Z. Bio-inspired hybrid path planning for efficient and smooth robotic navigation: F. Yuan et al. International Journal of Intelligent Robotics and Applications 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, N. Controllable Neural Dialogue Summarization with Personal Named Entity Planning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Yang, Z.; Al-Shedivat, M.; Xing, E.; Hu, Z. Progressive Generation of Long Text with Pretrained Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 4313–4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Gu, Y.; Ma, H.; Hong, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Hu, Z. Reasoning with Language Model is Planning with World Model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023; pp. 8154–8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziri, N.; Madotto, A.; Zaïane, O.; Bose, A.J. Neural Path Hunter: Reducing Hallucination in Dialogue Systems via Path Grounding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2197–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, T.; Nikkarinen, I.; Mahowald, K.; Cotterell, R.; Blasi, D. How (Non-)Optimal is the Lexicon? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 4426–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Z.; Yang, J.; Lin, Z. Data-Driven Evolutionary Game-Based Model Predictive Control for Hybrid Renewable Energy Dispatch in Autonomous Ships. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on New Energy System and Power Engineering (NESP). IEEE; 2025; pp. 482–490. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, J.; Nitski, O.; Wang, B.; Bader, G. DeCLUTR: Deep Contrastive Learning for Unsupervised Textual Representations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 879–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Xue, Y.; Yan, Z.; Huang, W.; Feng, J. Dynamic and Multi-Channel Graph Convolutional Networks for Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2627–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Wei, F.; Xie, T.; Xu, X.; Che, W.; Liu, T. GL-GIN: Fast and Accurate Non-Autoregressive Model for Joint Multiple Intent Detection and Slot Filling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, R.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, G. Joint Multi-modal Aspect-Sentiment Analysis with Auxiliary Cross-modal Relation Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 4395–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chang, K.C.C. Towards Reasoning in Large Language Models: A Survey. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023; pp. 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.; Cheng, Y. Weak to strong generalization for large language models with multi-capabilities. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Geng, X.; Shen, T.; Tao, C.; Long, G.; Lou, J.G.; Shen, J. Thread of thought unraveling chaotic contexts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.08734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Song, L.; Shen, J. Improving Medical Large Vision-Language Models with Abnormal-Aware Feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.01377, arXiv:2501.01377 2025.

- Peng, W.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qiao, Y. Data adaptive traceback for vision-language foundation models in image classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2024; Vol. 38, pp. 4506–4514. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Q.; Chen, J.; Wei, J.; Yang, M. Detect an Object At Once Without Fine-Tuning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing. Springer; 2024; pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, W.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.Q. T3M: Text Guided 3D Human Motion Synthesis from Speech. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.12885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Zhang, L.; Ma, D.; Fan, J.; Shi, D.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Gu, S.; Yin, D. PILE: Pairwise Iterative Logits Ensemble for Multi-Teacher Labeled Distillation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Industry Track; 2022; pp. 587–595. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.; Lin, S.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Peng, W.; He, T.; Pang, J.; Chi, M.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, K. Yume: An Interactive World Generation Model. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:2507.17744 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Che, W.; Wu, D.; Wang, S.; Hu, G.; Liu, T. Dynamic Connected Networks for Chinese Spelling Check. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Collision Rate (%) ↓ | Min Clearance Dist (m) ↑ | Task Success Rate (%) ↑ | Task Time (s) ↓ | Jerk (m/s3) ↓ | Curvature Rate (1/m·s)↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rule-based APF | 9.8 ± 1.2 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 82.5 ± 1.5 | 23.1 ± 1.8 | 3.12 ± 0.25 | 0.75 ± 0.08 |

| MPC-PathSmooth | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 87.9 ± 1.0 | 21.7 ± 1.4 | 2.58 ± 0.18 | 0.62 ± 0.07 |

| Hybrid A* + D* Lite | 5.1 ± 0.7 | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 89.2 ± 0.9 | 22.3 ± 1.5 | 2.80 ± 0.20 | 0.68 ± 0.09 |

| DL-ALP (ours) | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 0.78 ± 0.10 | 96.5 ± 0.6 | 19.5 ± 1.2 | 1.95 ± 0.12 | 0.45 ± 0.05 |

| Method | Collision Rate (%) ↓ | Min Clearance Dist (m) ↑ | Task Success Rate (%) ↑ | Task Time (s) ↓ | Jerk (m/s3) ↓ | Curvature Rate (1/m·s)↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL-ALP w/o DIRP-Net | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 0.60 ± 0.09 | 91.8 ± 0.8 | 20.8 ± 1.3 | 2.25 ± 0.15 | 0.55 ± 0.06 |

| DL-ALP w/o DRL Weights | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | 94.5 ± 0.7 | 20.1 ± 1.2 | 2.10 ± 0.14 | 0.49 ± 0.05 |

| DL-ALP (ours) | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 0.78 ± 0.10 | 96.5 ± 0.6 | 19.5 ± 1.2 | 1.95 ± 0.12 | 0.45 ± 0.05 |

| Method | Avg Planning Time (ms) ↓ |

|---|---|

| Rule-based APF | 15 ± 3 |

| MPC-PathSmooth | 45 ± 8 |

| Hybrid A* + D* Lite | 70 ± 12 |

| DL-ALP (ours) | 60 ± 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).