Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background to the Study

1.2. Statement of the Problem

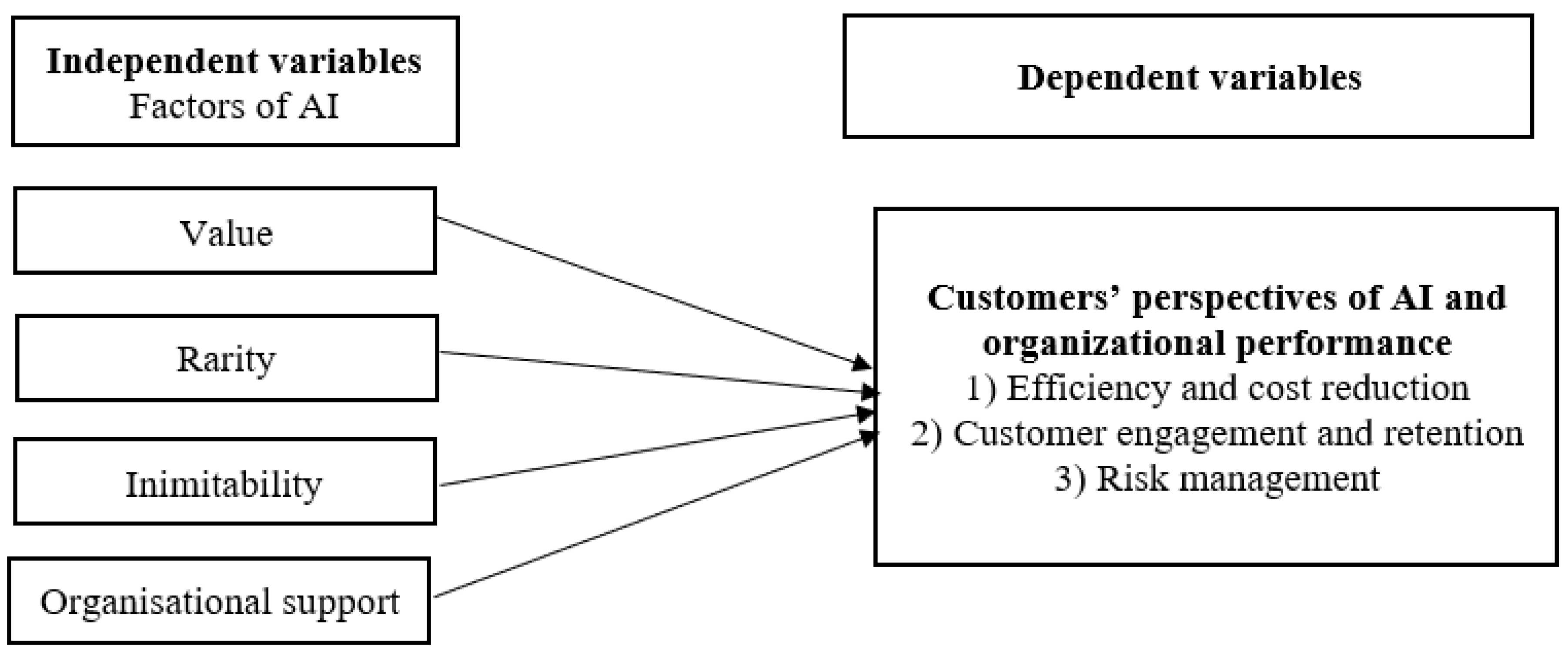

1.3. Objectives of the Study

- i.

- Determine if the value factor of AI has a significant influence on the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja;

- ii.

- Assess if the rarity factor of AI has a significant effect on customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja;

- iii.

- Examine if the inimitability factor of AI has a significant impact on Customers’ perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja;

- iv.

- Lastly, investigate if the organisational-support factor of AI have a significant impact on customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja.

1.4. Research Questions

- i.

- Does the value factor of AI have a significant influence on customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja?

- ii.

- Does the rarity factor of AI have a significant effect on customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja?

- iii.

- Does the inimitability factor of AI have a significant impact on customers' perspectives of AI and the organizational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja?

- iv.

- Lastly, does the organisational-support factor of AI has a significant impact on customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja?

1.5. Research Hypotheses

- i.

- H01: The value factor of AI has no significant influence on customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja.

- ii.

- H02: The rarity factor of AI has no significant effect on customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja.

- iii.

- H03: The inimitability factor of AI has no significant impact on customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja.

- iv.

- H04: The organisational support factor of AI has no significant influence on customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of selected DMBs in Abuja.

1.6. Significance of the Study

1.7. Scope of the Study

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Value Factor of Artificial Intelligence and Organisational Performance

2.1.2. Rarity Factor of Artificial Intelligence and Organisational Performance

2.1.3. Inimitability Factor of Artificial Intelligence and Organisational Performance

2.1.4. Organizational Support Factor of Artificial Intelligence and Organizational Performance

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Resource-Based View (RBV) Theory

2.2.2. Customers' Expectation Motivation Theory

2.3. Empirical Review

2.3.1. Appraisal of Reviewed Literature

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Population of the Study

3.3. Sample and Sampling Techniques

3.4. Instrument of Data Collection

3.5. Validity of the Instrument

3.6. Reliability of Instrument

3.7. Procedure of Data Collection

3.8. Method of Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Data Presentation

4.1.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

4.2. Testing of Hypotheses

4.2.1. Hypothesis One

4.2.2. Hypothesis Two

4.2.3. Hypothesis Three

4.2.4. Hypothesis Four

4.3. Discussion

- i.

- Value factor of AI: Customers' perspectives of AI were not influenced by the value factor of AI (convenience, enquiries, and trustworthy information feedback). Instead of seeing these services as novel or unique, customers perceived this factor as a component of the standard DMBs' package. Their expectations may already have been shaped by service assurances, industry norms, and previous interactions with these selected DMBs. This is in line with the findings of Ofuani, Omoera, and Akagha (2024), who also found that AI-driven customer service systems has no significant effect on DMBs' organisational performance. Customers of DMBs often complain about inefficiencies, so it makes sense to assume that the convenience factor of AI would be more important. However, the undervaluation of the value factor of AI by consumers indicated the lack of customer recognition of AI tools’ actual value addition to the selected DMBs' organisational performance in Abuja.

- ii.

- Rarity factor of AI: The rarity factor of AI, which included unique offerings, timely and accurate responses, and management commitment, also did not affect customers' perspectives of AI and organisational performance of the selected DMBs in Abuja. Hence, customers perceived no rarity factor of AI. Thus, this indicates customers perceived AI homogeneity across the selected DMBs in Abuja. This is contrary from Okolioko et al.’s (2023) findings, which found that AI had a significant positive impact on the organisational performance of DMBs. This disparity begs the question of whether Abuja consumers are less aware of AI than those in the Okolioko et al. (2023) study regions. Hence, customers may lack the exposure necessary to identify variations in AI implementation and how they affect DMBs' organisational performance in Abuja.

- iii.

- Inimitability factor of AI: Customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of the selected DMBs were unaffected by AI's inimitability factors, such as distinctive services and corporate reputation. Consumers believed that these AI-related products were not a source of competitive organisational because they were simple to imitate. This demonstrates a possible flaw in the way DMBs position or brand their AI initiatives. This validates the third hypothesis of the study. This is one of the most obvious conclusions: the selected DMBs' AI brands are hard to differentiate.

- iv.

- Organisational-support factor of AI: Lastly, customers did not consider the organisational support factor of AI (which includes cost reduction, engagement, retention, and efficiency) to be significant. This is in contrast to Okolioko et al. (2023), who discovered that the adoption of AI increased the DMBs' efficiency and satisfaction. Internal benefits and customer visibility seem to be at odds in this case. At the service level, customers may not always benefit from the cost savings or process improvements that the selected DMBs may be bringing about.

5. Conclusion

6. Recommendations

- i.

- Use VRIO as a benchmark: DMBs should use the VRIO model as a scorecard to determine whether their AI services actually offer customers recognisable service value, rare customer services, inimitable product and service offers, and organisational support. Without this kind of benchmarking, DMBs might keep spending money on AI without knowing if their customers will notice or value the changes in banking technology innovation.

- ii.

- Customise AI applications: DMBs should modify their AI tools to meet particular client needs rather than implementing generic AI systems. Instead of considering all services to be the same, this could assist customers in associating specific problem-solving skills with specific DMBs. The unexpected discovery that consumers viewed AI tools similarly across all chosen DMBs led directly to this recommendation.

- iii.

- Make brand positioning stronger: AI ought to be incorporated into the brand identity and reputation of every DMB. When customers perceive that an AI tool embodies a bank's distinct identity, it becomes more difficult for competitors to copy. This is an investment for the long run. As this study made clear, customers hardly ever connected AI tools to a particular DMB's brand.

- iv.

- Integrate AI into company culture: Knowledge of AI should be disseminated throughout departments, not just customer service, through internal marketing and training. Customer-facing services can better match internal capabilities when the entire organisation comprehends and strategically applies AI. This suggestion is in line with this study's finding that technical teams in DMBs tend to have the majority of the AI expertise, leaving other units out of the loop.

6.1. Limitations

- i.

- The sample population of the customers of five (5) selected DMBs in Abuja does not give a proper representation of the selected DMBs' branches' customers' perspectives of AI and their organisational performance across Nigeria.

- ii.

- Again, the 136 respondents that participated in this study and the non-probability convenience sampling technique adopted by this study do not give an adequate sample size that gives a significant representation of customers' perspectives of AI and the organisational performance of the selected DMBs in Abuja.

6.2. Suggestions for Further Studies

- i.

- Sampling strategy: A larger range of customer viewpoints could be captured by using stratified or cluster sampling, which might show more pronounced patterns than this study did. Despite its usefulness, the current sample did not accurately represent the range of customer experiences in Abuja. Richer insights might be obtained with a more multi-layered approach.

- ii.

- Sample size: Greater statistical significance and more accurate testing of effect sizes would be possible with larger samples. The analysis indicated multiple times that a larger sample could have revealed effects that are noticeable here.

- iii.

- Scope: To get a more accurate picture of AI adoption by DMBs in Nigeria, the study should be expanded beyond the five selected DMBs in Abuja to include additional organisations and states. Abuja was the sole focus of this study, which now seems to have been a limited perspective. A more comprehensive national perspective would result from expanding to other states.

- iv.

- Specific indicators: Future research could use an AI–Customer Satisfaction Index or an AI Service Equity Index, for instance, to measure performance more precisely. These would make it possible to track the effects of the VRIO factors of AI on customers’ perspectives more precisely. Although this study adopted VRIO factors of AI as a metric, more focused indices could improve subsequent studies' findings.

| Construct/ Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|

Value factor of AI 1. AI enhances the overall convenience of banking services. 2. AI enhances banking enquiries by providing reliable information. |

.804 |

|

Rarity factor of AI 3. AI is unique and not widely available across DMBs. 4. AI gives accurate feedbacks that are rare among DMBs. 5. AI is efficient and timely and is not common among DMBs. 6. DMBs’ management are committed to supporting AI initiatives. 7. DMBs’ employees are well trained to assist effectively with AI transactions. |

.827 |

|

Inimitability factor of AI 8. DMBs' operations are old enough to utilise capabilities of AI that is differentiable. 9. AI capability marches DMBs' corporate reputation among their customers. |

.793 |

|

Organizational-support factor of AI 10. DMBs have performed well in overall service efficiency and cost reduction. 11. DMBs have performed well in overall customers’ engagement and customer retention. 12. DMBs have performed well in overall fraud prevention and transaction risk management. |

.841 |

References

- Adepeju, A. A. , Logunleko, S. D., Amusa, B. O., & Onifade, H. O. (2024). Artificial intelligence and risk management of deposit money banks: Empirical evidence of Guaranty Trust bank. Umyu Journal of Accounting and Finance Research, 7(1), 178-193. [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, A. A. (2023). Credit risk management and financial performance of deposit money banks in Nigeria. International Accounting and Taxation Review, 9(1), 17-29.

- Amado, A. I. , Emubor, R. O., Mogue, T. O., & Abudullahi, S. A. (2024). The impact of artificial on organisational performance: insights from VFD micro-finance banks, Lagos State, Nigeria. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Sciences (IJRISS), VII (XIV), 518-524. [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. (2008). The basics of social research (4th Ed). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Barney, J.B. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. B. , & Clark, D. N. (2007). Resource-based theory: Creating and sustaining competitive advantage. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Barney, J. B. , & Hesterly, W. S. (2012). Strategic management and competitive advantage. USA: Pearson International Edition Prentice-Hall.

- Barney, J. B. , & Clark, D. N. (2017). Resource-based theory: Creating and sustaining competitive advantage. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Bellefonds, N. D. , Frank, M. R., Forth, P., Luther, A., Lukic, V., & Nopp, C. (2024). Where is the value in AI? Boston Consulting Group (BCG).

- Chinwendu, A. M. , Enudu, T. O., & Orga, J. I. (2024). Artificial intelligence and organisational performance of banks in South-East Nigeria. Advanced Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 8(6), 23-48.

- Convergence. (25). 2025 quarter 1 AI in Africa summary report: Policy digital transformation, and capacity building. https://www.convergenceai.io. 20 April.

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Defynd. (2025). 15 ways AI is being used in Europe. https://www.digitaldefynd.com/IQ/ways-ai-used-europe/.

- Eze, M. & Nwankwo, L. (2023). Human-machine collaboration in Nigerian banking: The future of AI chatbots. Journal of Digital Business, 9(1), 13-29.

- Frery, F. (2024). When artificial intelligence turns strategic resources into ordinary resources. ESCP Research Institute of Management (ERIM), 1-6.

- Ghaza, F. B. , Ramlee, S. N. S., Alwi, N., & Hizau, H. (2020). Content validity and test-retest reliability with principal component analysis of the translated Malay four-item version of the Paffenbarger Physical Activity Questionnaire. Journal of Health Research, 35(6), 493-505. [CrossRef]

- Graig, L. , Laskowski, N., & Tuuci, L. (2025). What is AI? Artificial intelligence explained. https://www.techtarget.com/searchenterpriseai/definition/AI-artficial.

- Ibrahim, T. , & Adepoju, R. (2023). The impact of AI chatbots on banking customer service in Nigeria. West African Journal of Financial Studies, 10(2), 78-96.

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliannan, M.; Darmalinggam, D.; Dorasamy, M.; Abraham, M. Inclusive talent development as a key talent management approach: A systematic literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2022, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamba, E. (2025). 2025 industry trends: Insights from Africa's business leaders. The Board Room Africa. https://www.theboardroomafrica.com.

- Kotler, P. , & Keller, K. L. (2016). Marketing Management. Boston: Pearson.

- Kumar, R. (2019). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. S: Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Leavy, P. (2017). Research Design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method, art-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Mei, H.; Bodog, S.-A.; Badulescu, D. Artificial Intelligence Adoption in Sustainable Banking Services: The Critical Role of Technological Literacy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Fjørtoft, S.O.; Torvatn, H.Y. (2019). Developing an Artificial Intelligence Capability: A Theoretical Framework for Business Value. In W. Abramowicz, & R. Corchuelo (Eds.), Business Information Systems Workshops. [CrossRef]

- Misuraca, G.; van Noordt, C.; Boukli, A. The use of AI in public services. ICEGOV 2020: 13th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, GreeceDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 90–99.

- Mulyani, A, & Fitrianti, E. (2012). Analysis of the effect of customer expectations, product quality, and customer Satisfaction on credit card user loyalty. PT. XYZ, Tbk in Makasar. Hasanuddin University.

- Nwokoji, C. (2023, ). Seven banks compete in artificial intelligence adoption. Nigerian Tribune. https://amps/tribuneng.com/seven-banks-compete-in-artificial- intelligence-adoption/amp/. 3 January.

- Ofuani, A. B. , Omoera, C. I., & Akagha, C. (2024). Artificial intelligence and performance of money deposit banks in Lagos metropolis: A study of United bank of Africa. UniLag Journal of Business, 10(1), 54-81.

- Ogundele, A. T. , Ibitoye, O. A, Akinteiwa, O.A., Adeniran, A., Ibukun, F. O., & Apata, T. G. (2025). The role of artificial intelligence in advancing sustainable service efficiency in Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable development law and policy, 16 (1).

- Okoliko, E. O. , Ayetigbo, O. A., Ifegwu, I. J., & Chidiebere, N. U. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Impact in Revolutionising the Nigerian banking industry: An assessment of selected deposit money banks in Abuja. Achievers Journal of Scientific Research, 5(2), 120-131.

- Olumoyegun, P M., Alabi, J. O., & Nurudeen, Y. Z. (2024). Contemporary issues of AI and performance of employees at selected deposit money banks in Lagos, Nigeria. Journal of Business, Innovation, and Creativity, 3(2), 141-151.

- Orjinta, H. I. , & Anetoh, J. C. (2025). Achieving sustainable performance of deposit money banks in Nigeria through artificial intelligence strategies. Innovations, 80.https://journal-innovation.com.

- Parasuraman, A. , Zeithaml, V., & Berry, L. (1985). "A Conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 9-20.

- PWC. (2025). AI in Nigeria: Opportunities, challenges, and strategic pathways. https://www.pwc.com/ng.

- Salemcity, A.; Aiyesan, O.; Japinye, A.O. Artificial Intelligence Adoption and Corporate Operating Activities of Deposit Money Banks. Eur. J. Accounting, Audit. Finance Res. 2023, 11, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simamora, S.; Rahayu, A.; Dirgantari, P.D. Driving Digital Transformation in Small Banks With VRIO Analysis. J. Apl. Bisnis dan Manaj. 2024, 10, 99–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strykar, C. , & Kavlakoglu, E. (2024, ). What is artificial intelligence (AI)? IBM.COM. https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/artificial/-intelligence?utm_source=perplexity. 4 August.

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L. (2023). Cross-sectional study: Definition, uses, and examples. https://www.scribbr.com/method%20on%20May%208%2C%202020%20by%20Lauren,design%20ich%20you%20collect%20data%20from.

- Tomczak, M. , & Tomczak, E. (2014). The need to report effect size estimates: An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends in Sports Sciences, 1 (21), 19-25.

- Udodiugwu, M. I. , Eneremadu, K. E., Onunkwo, A. R., & Gloria, O. C. (2024). The role of artificial intelligence in enhancing the performance of banks in Nigeria. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 11(2), 27-34.

- Unuesiri, F. , & Adejuwon, J. A. (2024). Artificial intelligence expert system and financial performance of deposit money banks in Nigeria. International Institute of Academic Research and Development, 10(9), 39-54. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G. (2024). Qualitative vs. quantitative research. Gwl.com. Retrieved from https://www.gwl.com/blog/qualitative-vs-quantitative/03fhs_amp=true.

|

Access Bank n % |

First Bank n % |

GT Bank n % |

UBA Bank n % |

Zenith Bank n % |

Full sample N % |

|

|

Gender Male Female Total |

24 50 24 50 48 100 |

10 62.5 6 37.5 16 100 |

15 39.5 23 60.5 38 100 |

2 20 8 80 10 100 |

5 20.8 19 79.2 24 100 |

56 41.2 80 58.8 136 100 |

|

Number of acct owned One acct More than one acct Total |

11 22.9 37 77.1 48 100 |

5 31.3 11 68.7 16 100 |

7 18.4 31 81.6 38 100 |

5 50 5 50 10 100 |

8 33.3 16 66.7 24 100 |

36 26.5 100 73.5 136 100 |

|

Alternative acct owned None Access Bank First Bank GT Bank UBA Bank Zenith Bank Total |

18 37.5 0 0 3 6.3 15 31.3 4 8.3 8 16.7 48 100 |

4 25.0 3 18.8 0 0 3 18.8 3 18.8 3 18.8 16 100 |

17 44.7 0 0 0 0 3 7.9 15 39.5 3 7.89 38 100 |

7 70 2 20 1 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 10 100 |

17 70.8 4 16.6 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 12.5 24 100 |

63 46.3 9 6.6 4 2.9 21 15.4 25 18.4 14 10.3 136 100 |

|

Type of acct Saving Current Fixed Total |

32 66.7 11 22.9 5 10.4 48 100 |

13 81.3 3 18.7 0 0 16 100 |

27 71.1 11 28.9 0 0 38 100 |

5 50 5 50 0 0 10 100 |

19 79.2 2 8.3 3 12.5 24 100 |

96 70.6 32 23.1 8 5.9 136 100 |

|

AI awareness Yes No Uncertain Total |

32 66.7 6 12.5 10 20.8 38 100 |

8 50 8 50 0 0 16 100 |

22 57.9 15 39.5 1 2.6 38 100 |

5 50 3 30 2 20 10 100 |

9 37.5 0 0 15 62.5 24 100 |

76 55.9 32 23.5 28 20.6 136 100 |

|

AI platform Chatbot Webpage Total |

14 29.2 12 25.0 9 18.8 13 27.0 48 100 |

2 12.5 2 12.5 3 18.7 9 56.3 16 100 |

5 13.2 18 47.4 7 18.4 8 21.0 38 100 |

2 20 3 30 3 30 2 20 10 100 |

3 12.5 2 8.3 13 54.2 6 25.0 24 100 |

26 19.1 37 27.2 35 25.7 38 28.0 136 100 |

| P-Value | H-Statistics | Decision | Effect Size (E2) | |

| Value factor of AI | .13 | 7.02 | Retain null hypothesis | 0.02 |

| Rarity factor of AI | .12 | 7.23 | Retain null hypothesis | 0.03 |

| Inimitability factor of AI | .79 | 1.70 | Retain null hypothesis | -0.02 |

| Organisational support factor of AI | .08 | 8.28 | Retain null hypothesis | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).