Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

07 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

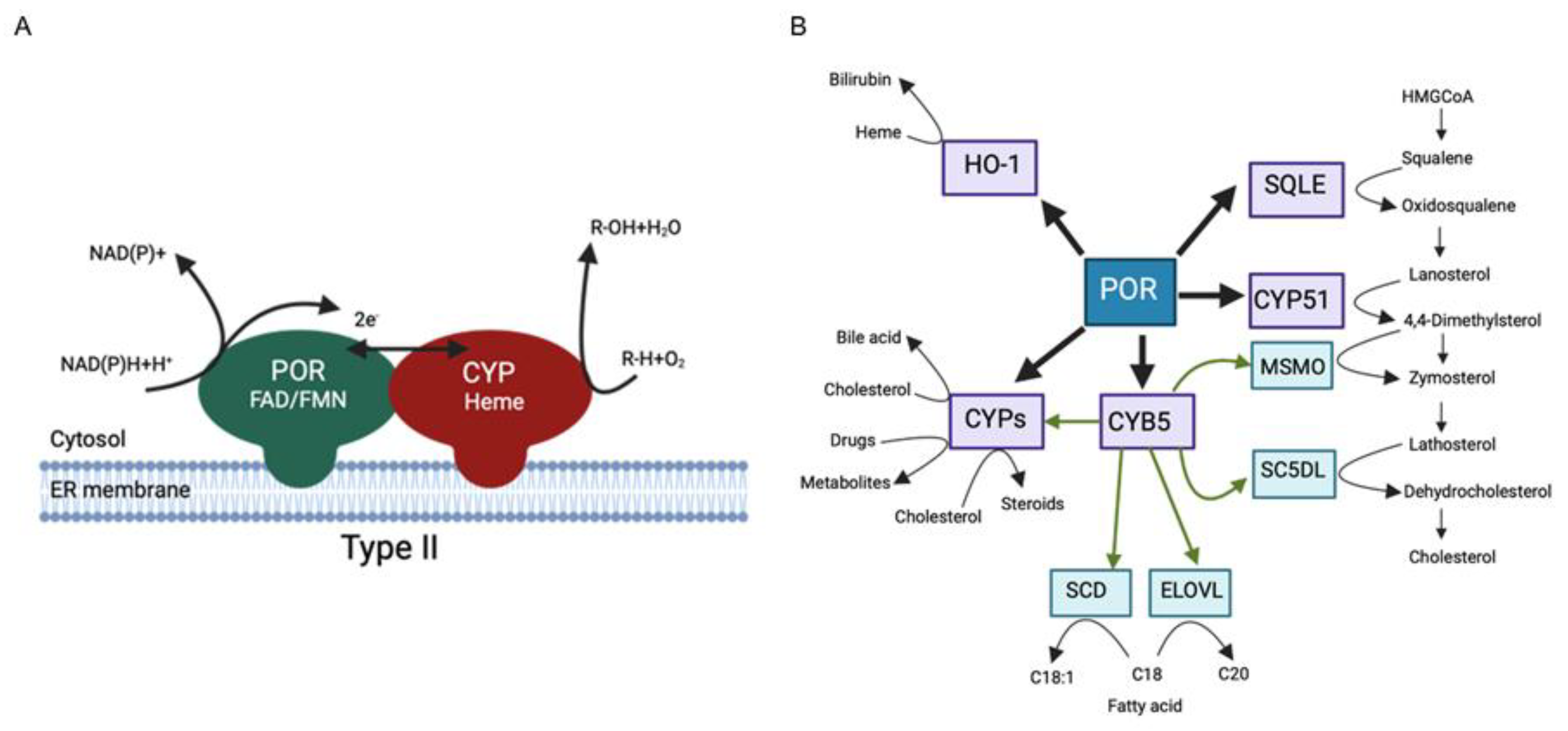

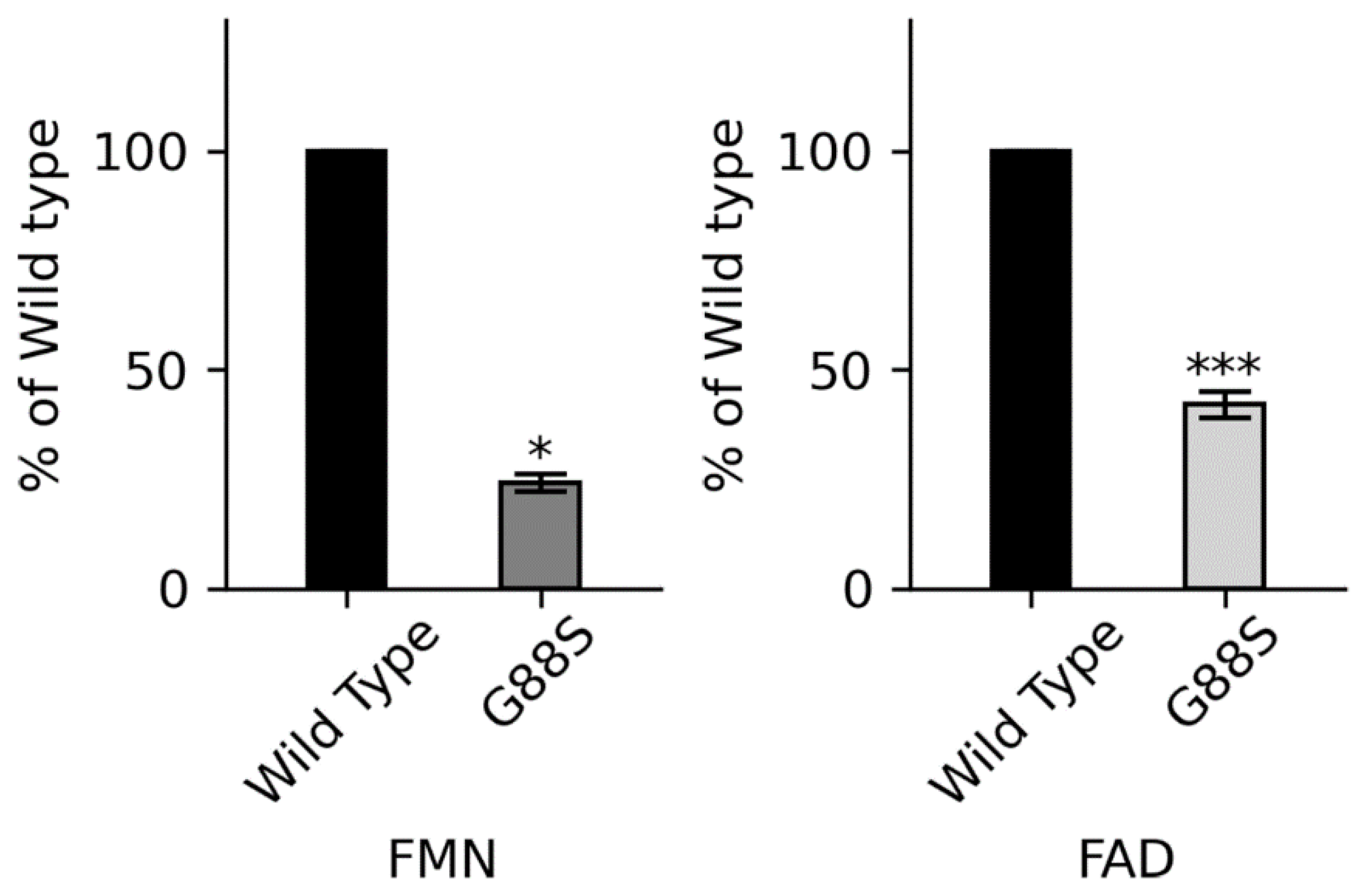

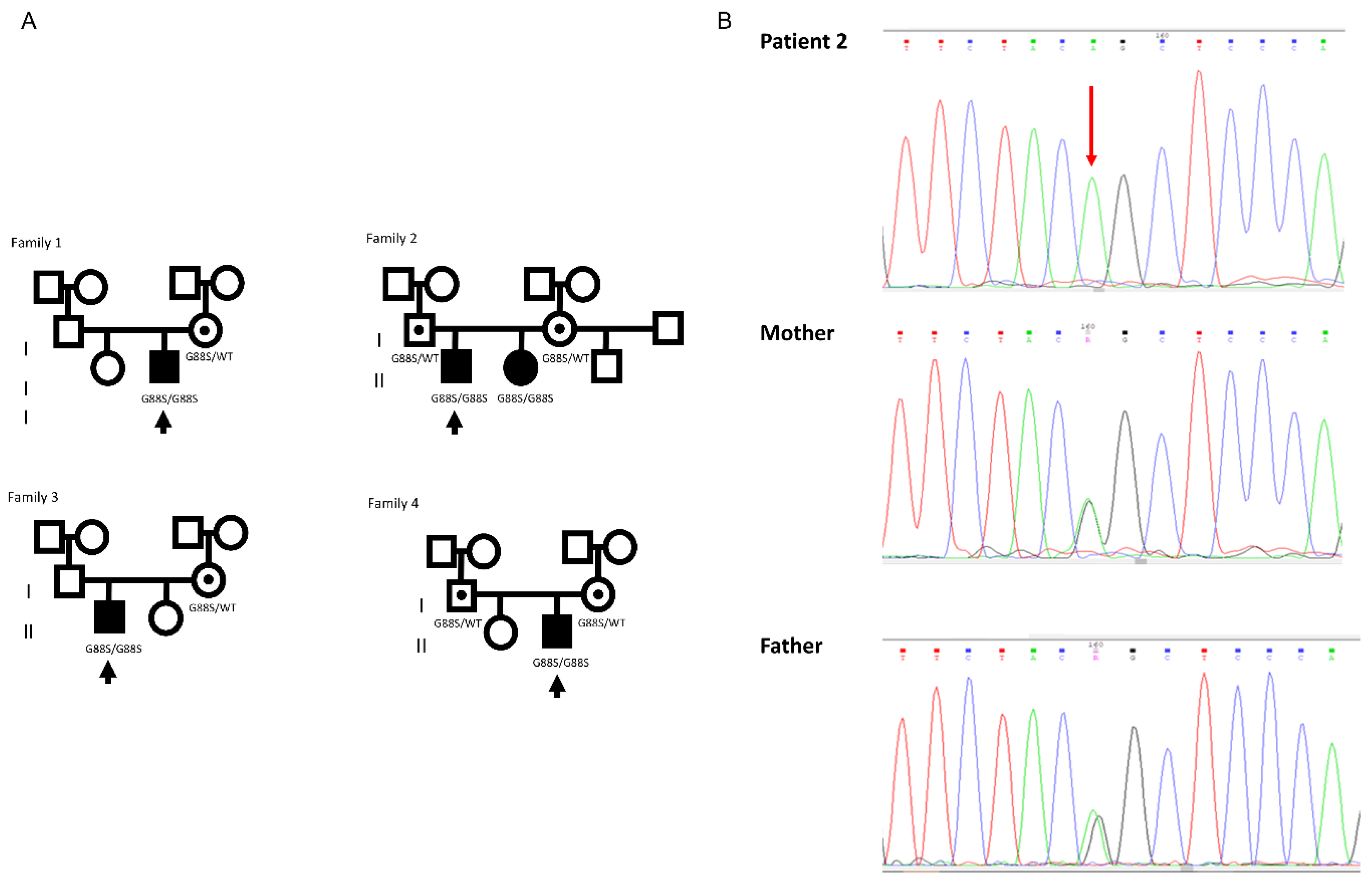

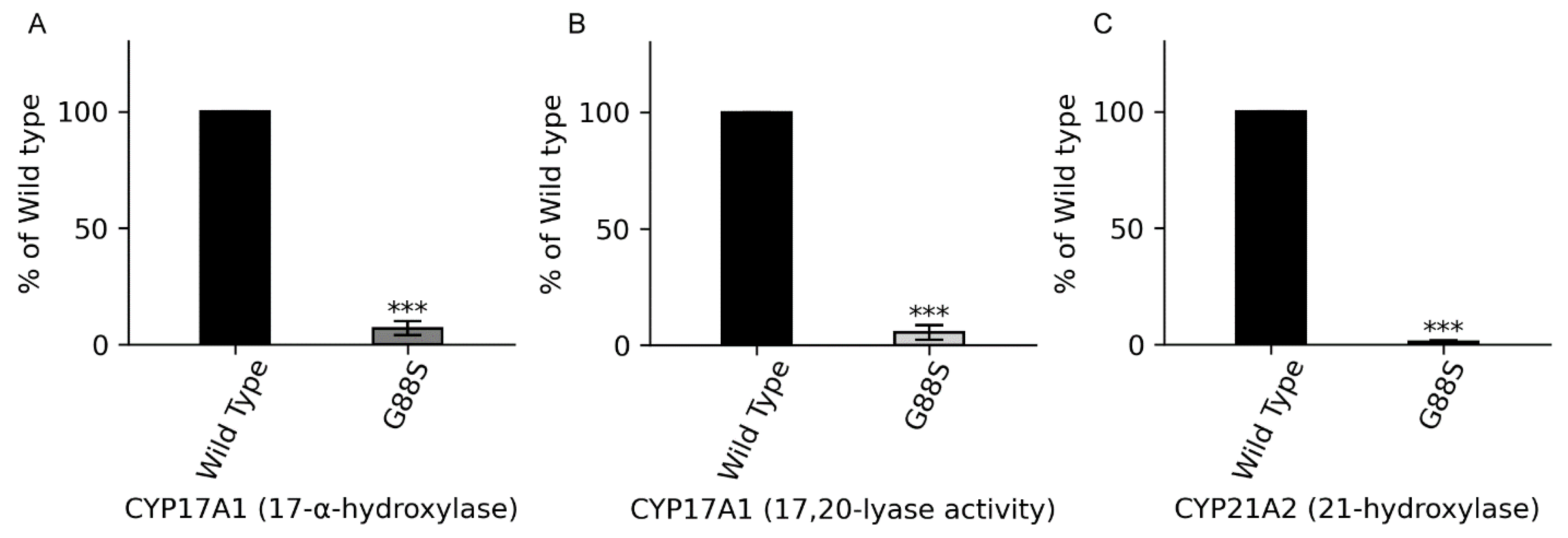

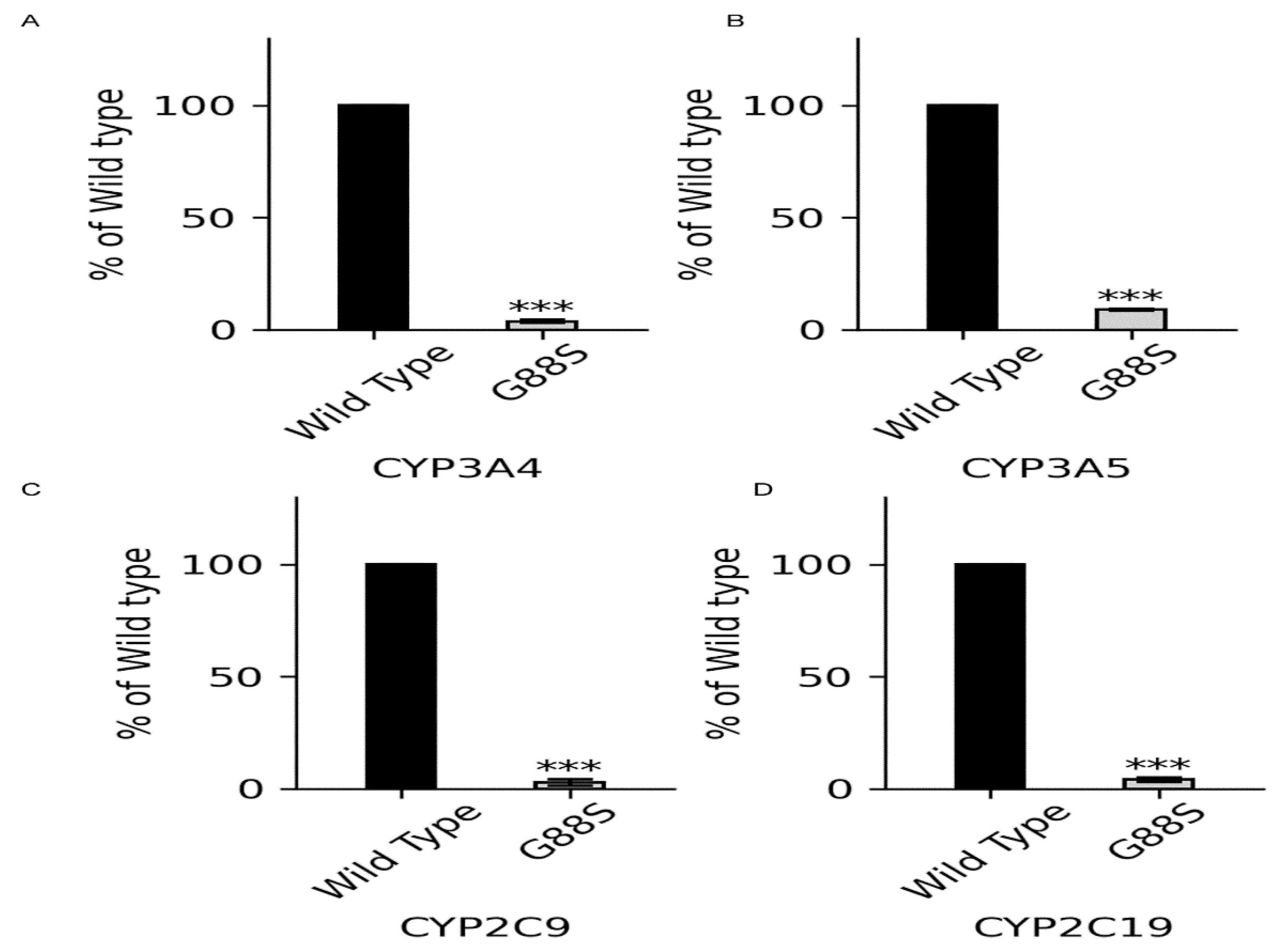

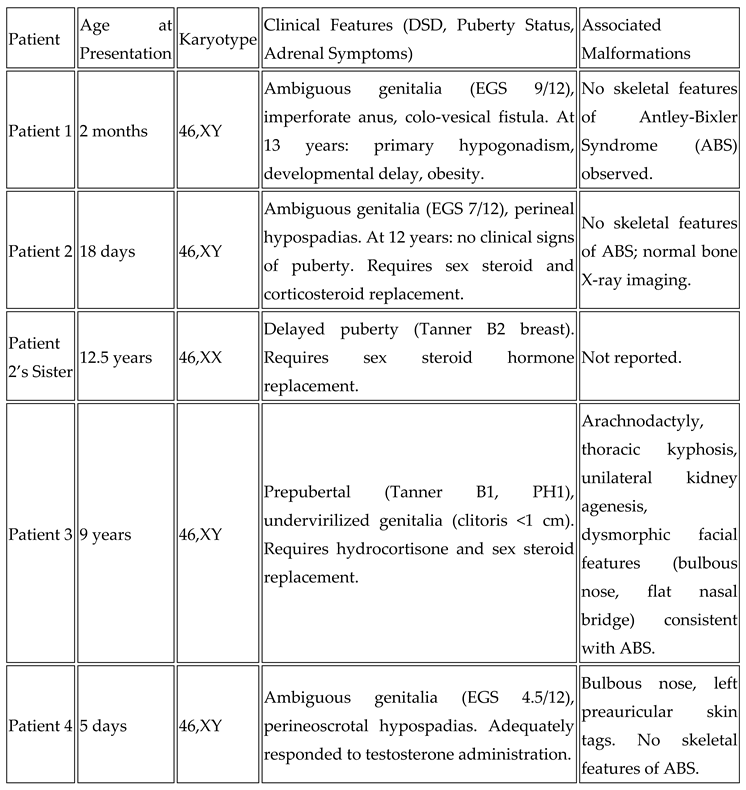

Context: P450 oxidoreductase (POR) deficiency is a rare congenital adrenal hyperplasia with variable severity. The mechanisms of severe mutations and their full metabolic consequences, including drug metabolism, are not fully characterized. Objective: To define the clinical, biochemical, and molecular consequences of a novel homozygous POR missense mutation, p.Gly88Ser (G88S), identified in four unrelated Argentine families. Design: A translational study combining clinical case series analysis with comprehensive in vitro molecular and functional characterization of the novel protein variant. Setting: Tertiary pediatric endocrine centers in Argentina and Switzerland. Patients: Five individuals (four 46,XY; one 46,XX) from four unrelated families presenting with disorders of sex development and adrenal dysfunction. Main Outcome Measures: Clinical phenotypes, hormonal profiles, and POR gene sequencing. In vitro analysis of recombinant POR measured flavin content, reductase activity, and support of steroidogenic and drug-metabolizing P450s. Results: All patients were homozygous for the c.262G>A (p.G88S) mutation. This FMN-binding domain variant caused protein instability with severe loss of FMN (<30%) and FAD (<15%) cofactors. Steroidogenic activities were virtually abolished (CYP21A2: 1.3%; CYP17A1 17,20-lyase: 5.5% of wild-type), explaining the clinical phenotype. Activities of major drug-metabolizing enzymes were also severely impaired (3-9% of wild-type), establishing a “ poor metabolizer” phenotype. Conclusions: The POR G88S mutation causes one of the most severe forms of PORD described, driven by dynamic protein instability and cofactor loss. It is a critical pharmacogenomic marker, and its recurrence in Argentina suggests a potential screening target.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Approval and Patient Consent

Clinical Assessment

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 3 months | 6 months | 12 yr | 12 yr | 10 yr | 8 months | 11 months | |||||||||||||

| Hormonal test | basal | Post hCG | basal | Post ACTH | basal | Post hCG | basal | Post ACTH | basal | Post ACTH | basal | Post hCG | basal | Post ACTH | ||||||

| T ng/dL | 18 | 54 | - | - | <10 | 156 | <10 | - | <20 | 40 | 95 | <10 | <10 | |||||||

| A4 ng/dL | - | 16 | 19 | 49 | 21 | 23 | 21 | 26 | <10 | <10 | 51 | 11 | 21 | 17 | ||||||

| 17OHP ng/mL | 7.9 | 6.1 | 19.5 | 19.4 | 12.7 | 9.8 | 12.7 | 15 | 17.6 | 16.6 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 11.9 | 14.5 | ||||||

| Progesterone ng/mL | 21 | 25 | 26 | > 66 | 20.5 | 10.7 | 20.5 | 26.3 | 34 | > 66 | - | - | > 66 | > 66 | ||||||

| DHEA-S ng/mL | 591 | 304 | 591 | 588 | <20 | <150 | <150 | <150 | <150 | |||||||||||

| ACTH pg/mL | - | - | 84 | - | - | - | 72 | - | 129 | - | - | 413 | - | |||||||

| Cortisol µg/dL | - | - | 11.1 | 11.1 | - | - | 9.3 | 8.5 | 5.7 | 4.7 | - | - | 8.3 | 8.5 | ||||||

| AMH pmol/L | 385 | 496 | - | - | - | 162 | 1328 | - | - | - | ||||||||||

| LH IU/L | 0.3 | - | - | - | 1.6 | - | - | - | 0.6 | 5.2 | - | - | - | |||||||

| FSH IU/L | 1.1 | - | - | - | 1.4 | - | - | - | 5.8 | 1.8 | - | - | - | |||||||

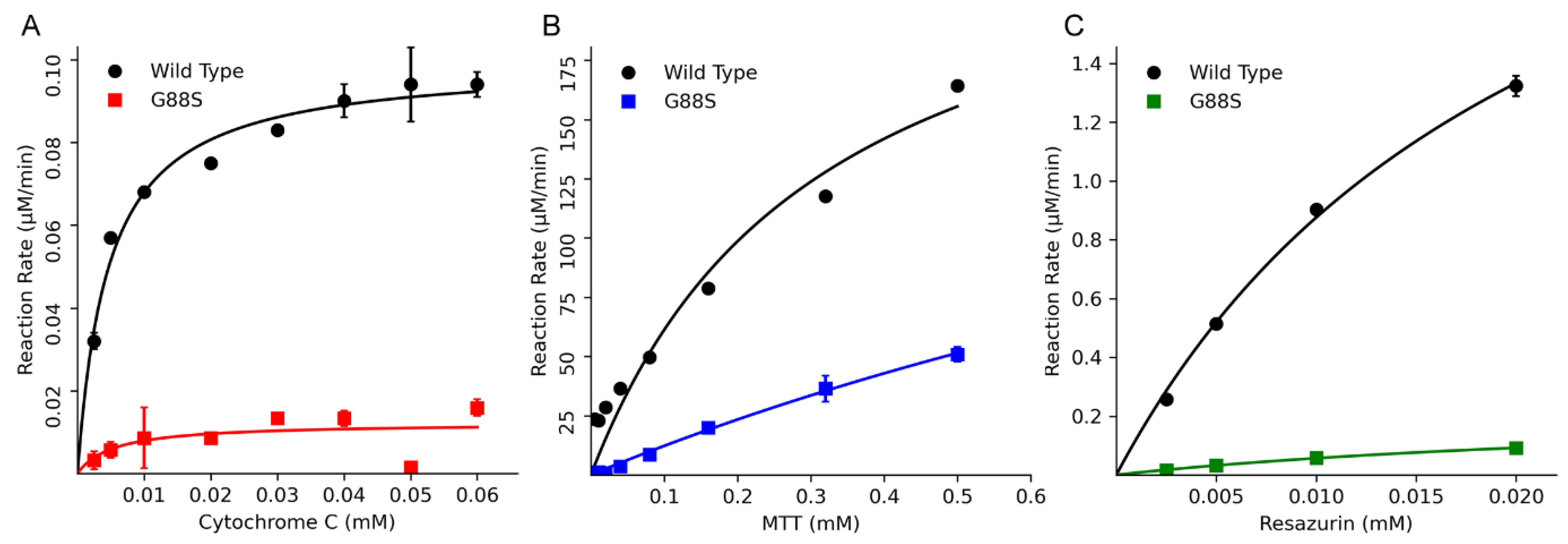

Small Molecule Reduction Assay by POR-WT and POR-G88S

Results

Case Reports

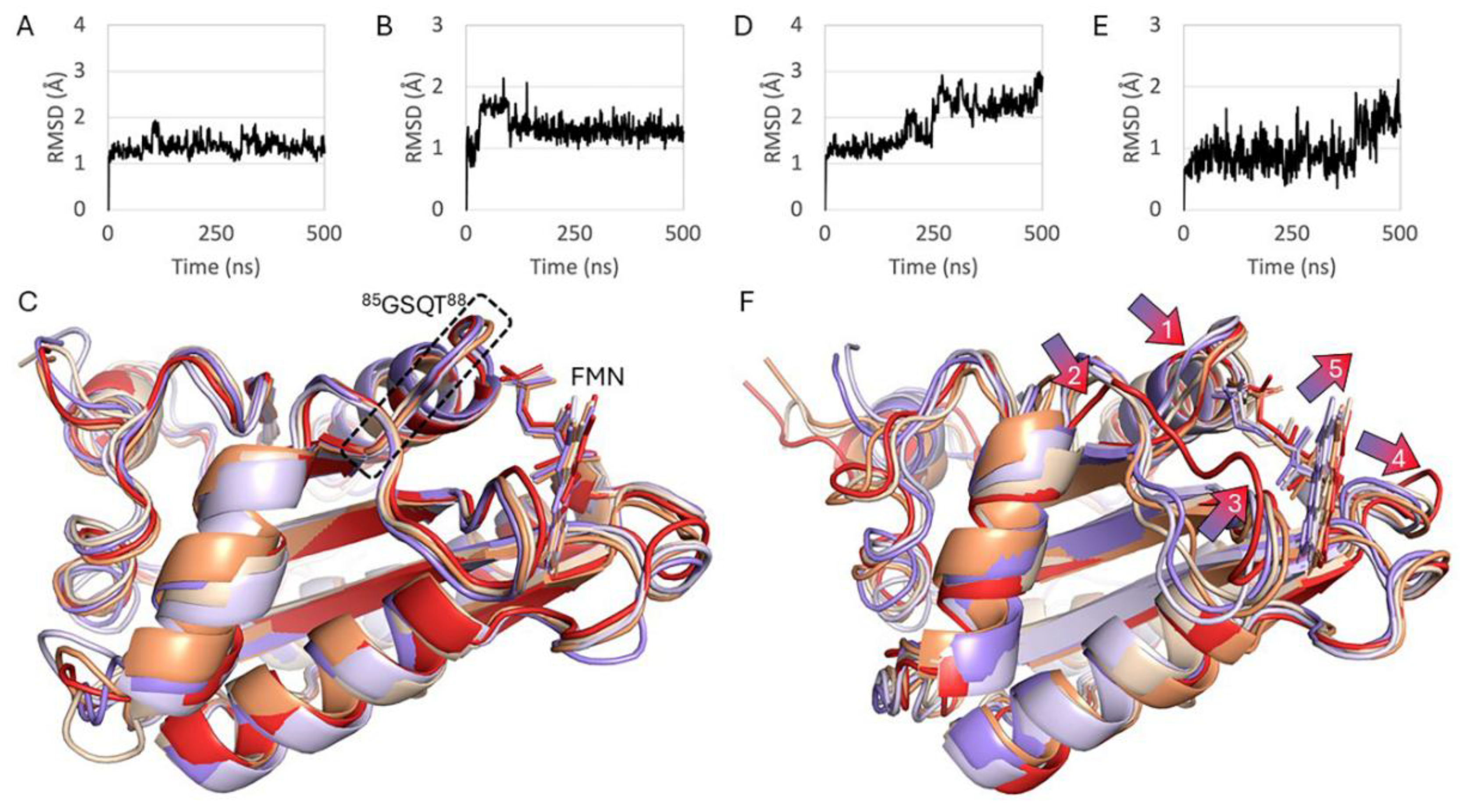

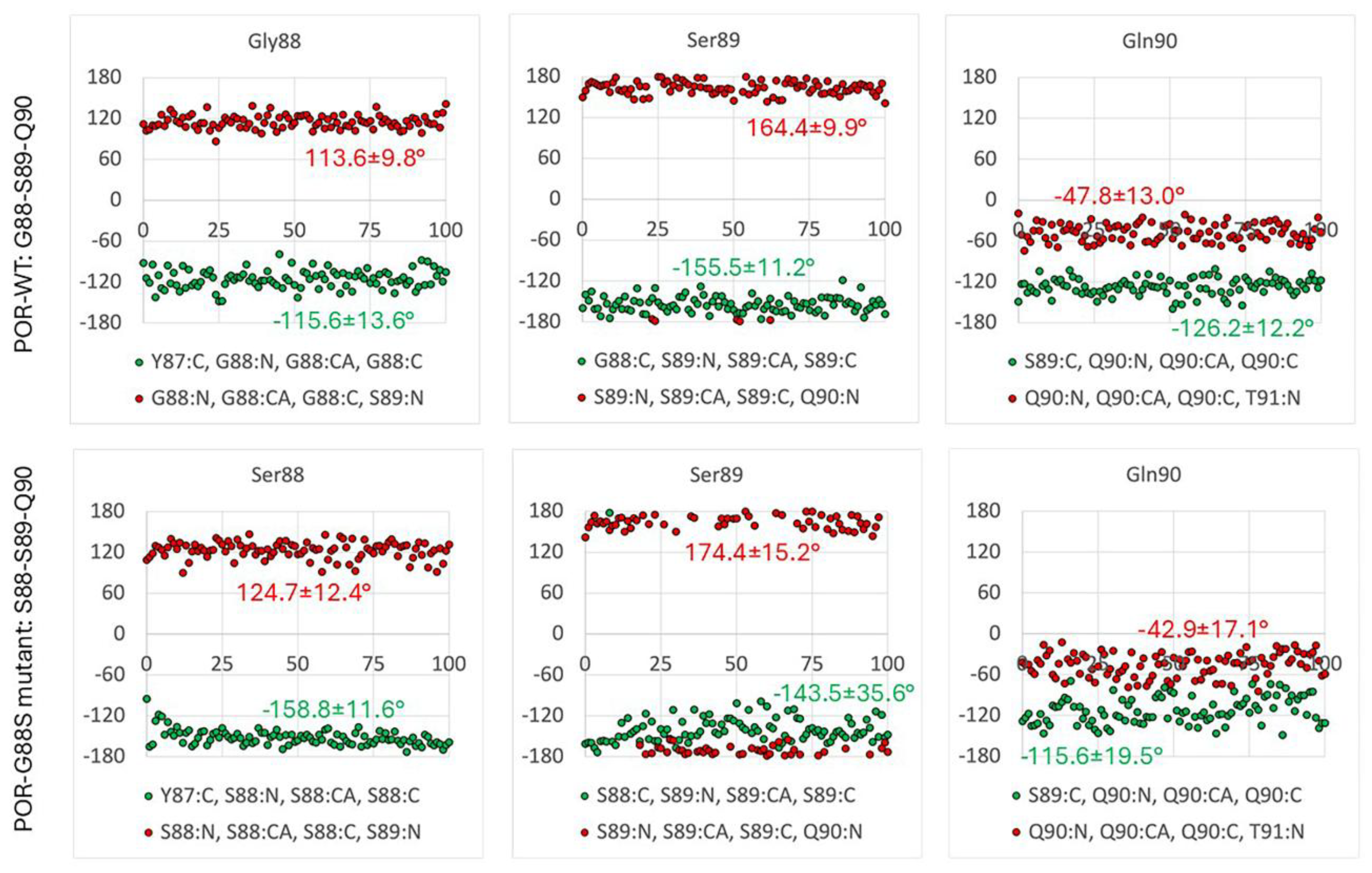

Glycine 88 Is Located near FMN Binding Site in POR and Mutation G88S Creates Protein Instability

Discussion

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Pandey, A. V.; Flück, C. E., NADPH P450 oxidoreductase: structure, function, and pathology of diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2013, 138, (2), 229-54. [CrossRef]

- Flück, C. E.; Tajima, T.; Pandey, A. V.; Arlt, W.; Okuhara, K.; Verge, C. F.; Jabs, E. W.; Mendonça, B. B.; Fujieda, K.; Miller, W. L., Mutant P450 oxidoreductase causes disordered steroidogenesis with and without Antley-Bixler syndrome. Nat Genet 2004, 36, (3), 228-30. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W. L.; Huang, N.; Flück, C. E.; Pandey, A. V., P450 oxidoreductase deficiency. Lancet 2004, 364, (9446), 1663.

- Pandey, A. V.; Fluck, C. E.; Huang, N.; Tajima, T.; Fujieda, K.; Miller, W. L., P450 oxidoreductase deficiency: a new disorder of steroidogenesis affecting all microsomal P450 enzymes. Endocr Res 2004, 30, (4), 881-8. [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Tachibana, K.; Asakura, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Hanaki, K.; Oka, A., Compound heterozygous mutations of cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase gene (POR) in two patients with Antley-Bixler syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2004, 128A, (4), 333-9. [CrossRef]

- Arlt, W.; Walker, E. A.; Draper, N.; Ivison, H. E.; Ride, J. P.; Hammer, F.; Chalder, S. M.; Borucka-Mankiewicz, M.; Hauffa, B. P.; Malunowicz, E. M.; Stewart, P. M.; Shackleton, C. H., Congenital adrenal hyperplasia caused by mutant P450 oxidoreductase and human androgen synthesis: analytical study. Lancet 2004, 363, (9427), 2128-35. [CrossRef]

- Fukami, M.; Horikawa, R.; Nagai, T.; Tanaka, T.; Naiki, Y.; Sato, N.; Okuyama, T.; Nakai, H.; Soneda, S.; Tachibana, K.; Matsuo, N.; Sato, S.; Homma, K.; Nishimura, G.; Hasegawa, T.; Ogata, T., Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase gene mutations and Antley-Bixler syndrome with abnormal genitalia and/or impaired steroidogenesis: Molecular and clinical studies in 10 patients. J Clin Endocr Metab 2005, 90, (1), 414-426. [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Pandey, A. V.; Agrawal, V.; Reardon, W.; Lapunzina, P. D.; Mowat, D.; Jabs, E. W.; Van Vliet, G.; Sack, J.; Flück, C. E.; Miller, W. L., Diversity and function of mutations in p450 oxidoreductase in patients with Antley-Bixler syndrome and disordered steroidogenesis. Am J Hum Genet 2005, 76, (5), 729-49. [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Asakura, Y.; Matsuo, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Hanaki, K.; Arlt, W., POR R457H is a global founder mutation causing Antley-Bixler syndrome with autosomal recessive trait. Am J Med Genet A 2006, 140, (6), 633-5. [CrossRef]

- Fukami, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Horikawa, R.; Ohashi, T.; Nishimura, G.; Homma, K.; Ogata, T., Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase deficiency in three patients initially regarded as having 21-hydroxylase deficiency and/or aromatase deficiency: Diagnostic value of urine steroid hormone analysis. Pediatric Research 2006, 59, (2), 276-280. [CrossRef]

- Homma, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Nagai, T.; Adachi, M.; Horikawa, R.; Fujiwara, I.; Tajima, T.; Takeda, R.; Fukami, M.; Ogata, T., Urine steroid hormone profile analysis in cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase deficiency: Implication for the backdoor pathway to dihydrotestosterone. J Clin Endocr Metab 2006, 91, (7), 2643-2649. [CrossRef]

- Lu, A. Y. H.; Junk, K. W.; Coon, M. J., Resolution of Cytochrome P-450-Containing Omega-Hydroxylation System of Liver Microsomes into 3 Components. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1969, 244, (13), 3714-+. [CrossRef]

- Guengerich, F. P.; Ballou, D. P.; Coon, M. J., Purified liver microsomal cytochrome P-450. Electron-accepting properties and oxidation-reduction potential. J Biol Chem 1975, 250, (18), 7405-14. [CrossRef]

- Lu, A. Y.; Junk, K. W.; Coon, M. J., Resolution of the cytochrome P-450-containing omega-hydroxylation system of liver microsomes into three components. J Biol Chem 1969, 244, (13), 3714-21. [CrossRef]

- Guengerich, F. P., Reduction of cytochrome b(5) by NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2005, 440, (2), 204-211. [CrossRef]

- Masters, B. S.; Nelson, E. B.; Schacter, B. A.; Baron, J.; Isaacson, E. L., NADPH-cytochrome c reductase and its role in microsomal cytochrome P-450-dependent reactions. Drug Metab Dispos 1973, 1, (1), 121-8. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E. B.; Kohl, K. B.; Masters, B. S., The role of NADPH-cytochrome c reductase in the microsomal oxidation of ethanol and methanol. Drug Metab Dispos 1973, 1, (1), 455-60. [CrossRef]

- Yasukochi, Y.; Masters, B. S., Some properties of a detergent-solubilized NADPH-cytochrome c(cytochrome P-450) reductase purified by biospecific affinity chromatography. J Biol Chem 1976, 251, (17), 5337-44. [CrossRef]

- Prough, R. A.; Masters, B. S., The mechanism of cytochrome b5 reduction by NADPH-cytochrome c reductase. Arch Biochem Biophys 1974, 165, (1), 263-7. [CrossRef]

- Schacter, B. A.; Nelson, E. B.; Marver, H. S.; Masters, B. S., Immunochemical evidence for an association of heme oxygenase with the microsomal electron transport system. J Biol Chem 1972, 247, (11), 3601-7. [CrossRef]

- Bligh, H. F.; Bartoszek, A.; Robson, C. N.; Hickson, I. D.; Kasper, C. B.; Beggs, J. D.; Wolf, C. R., Activation of mitomycin C by NADPH:cytochrome P-450 reductase. Cancer Res 1990, 50, (24), 7789-92.

- Bartoszek, A.; Wolf, C. R., Enhancement of Doxorubicin Toxicity Following Activation by Nadph Cytochrome P450 Reductase. Biochemical Pharmacology 1992, 43, (7), 1449-1457. [CrossRef]

- Walton, M. I.; Wolf, C. R.; Workman, P., The Role of Cytochrome-P450 and Cytochrome-P450 Reductase in the Reductive Bioactivation of the Novel Benzotriazine Di-N-Oxide Hypoxic Cytotoxin 3-Amino-1,2,4-Benzotriazine-1,4-Dioxide (Sr-4233, Win-59075) by Mouse-Liver. Biochemical Pharmacology 1992, 44, (2), 251-259. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Gu, J.; Weng, Y.; Kluetzman, K.; Swiatek, P.; Behr, M.; Zhang, Q. Y.; Zhuo, X.; Xie, Q.; Ding, X., Conditional knockout of the mouse NADPH-cytochrome p450 reductase gene. Genesis 2003, 36, (4), 177-81. [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, Q. Y.; Cui, H. D.; Behr, M.; Wu, L.; Yang, W. Z.; Zhang, L.; Ding, X. X., Liver-specific deletion of the NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase gene–Impact on plasma cholesterol homeostasis and the function and regulation of microsomal cytochrome P450 and heme oxygenase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, (28), 25895-25901.

- Henderson, C. J.; Otto, D. M. E.; Carrie, D.; Magnuson, M. A.; McLaren, A. W.; Rosewell, I.; Wolf, C. R., Inactivation of the hepatic cytochrome P450 system by conditional deletion of hepatic cytochrome P450 reductase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, (15), 13480-13486. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C. J.; Otto, D. M. E.; Carrie, D.; McLaren, A. W.; Ross, J.; Rosewell, I.; Wolf, C. R., Mouse hepatic P450 reductase knockout. Toxicology 2004, 194, (3), 216-217.

- Weng, Y.; DiRusso, C. C.; Reilly, A. A.; Black, P. N.; Ding, X. X., Hepatic gene expression changes in mouse models with liver-specific deletion or global suppression of the NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase gene–Mechanistic implications for the regulation of microsomal cytochrome P450 and the fatty liver phenotype. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, (36), 31686-31698.

- Gu, J.; Wu, L.; Weng, Y.; Kluetzman, K.; Cui, H. D.; Zhang, Q. Y.; Yang, W. Z.; Ding, X. X., Preparation and characterization of mice with liver-specific deletion of the NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase gene. Drug Metabolism Reviews 2002, 34, 112-112.

- Gu, J.; Chen, C. S.; Wei, Y.; Fang, C.; Xie, F.; Kannan, K.; Yang, W. Z.; Waxman, D. J.; Ding, X. X., A mouse model with liver-specific deletion and global suppression of the NADPH-Cytochrome P450 reductase gene: Characterization and utility for in vivo studies of cyclophosphamide disposition. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2007, 321, (1), 9-17. [CrossRef]

- Parween, S.; Fernandez-Cancio, M.; Benito-Sanz, S.; Camats, N.; Rojas Velazquez, M. N.; Lopez-Siguero, J. P.; Udhane, S. S.; Kagawa, N.; Fluck, C. E.; Audi, L.; Pandey, A. V., Molecular Basis of CYP19A1 Deficiency in a 46,XX Patient With R550W Mutation in POR: Expanding the PORD Phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105, (4), dgaa076. [CrossRef]

- Parween, S.; Roucher-Boulez, F.; Flück, C. E.; Lienhardt-Roussie, A.; Mallet, D.; Morel, Y.; Pandey, A. V., P450 Oxidoreductase Deficiency: Loss of Activity Caused by Protein Instability From a Novel L374H Mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016, 101, (12), 4789-4798. [CrossRef]

- Flück, C. E.; Mallet, D.; Hofer, G.; Samara-Boustani, D.; Leger, J.; Polak, M.; Morel, Y.; Pandey, A. V., Deletion of P399_E401 in NADPH cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase results in partial mixed oxidase deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 412, (4), 572-7. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S. B.; Thodberg, S.; Parween, S.; Moses, M. E.; Hansen, C. C.; Thomsen, J.; Sletfjerding, M. B.; Knudsen, C.; Del Giudice, R.; Lund, P. M.; Castano, P. R.; Bustamante, Y. G.; Velazquez, M. N. R.; Jorgensen, F. S.; Pandey, A. V.; Laursen, T.; Moller, B. L.; Hatzakis, N. S., Biased cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism via small-molecule ligands binding P450 oxidoreductase. Nat Commun 2021, 12, (1), 2260. [CrossRef]

- Riddick, D. S.; Ding, X.; Wolf, C. R.; Porter, T. D.; Pandey, A. V.; Zhang, Q. Y.; Gu, J.; Finn, R. D.; Ronseaux, S.; McLaughlin, L. A.; Henderson, C. J.; Zou, L.; Flück, C. E., NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase: roles in physiology, pharmacology, and toxicology. Drug Metab Dispos 2013, 41, (1), 12-23. [CrossRef]

- Kamin, H.; Masters, B. S.; Gibson, Q. H.; Williams, C. H., Jr., Microsomal TPNH-cytochrome c reductase. Fed Proc 1965, 24, (5), 1164-71.

- Masters, B. S.; Okita, R. T., The history, properties, and function of NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase. Pharmacol Ther 1980, 9, (2), 227-44. [CrossRef]

- Rojas Velazquez, M. N.; Therkelsen, S.; Pandey, A. V., Exploring Novel Variants of the Cytochrome P450 Reductase Gene (POR) from the Genome Aggregation Database by Integrating Bioinformatic Tools and Functional Assays. Biomolecules 2023, 13, (12), 1728. [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, F. Z.; Parween, S.; Udhane, S. S.; Flück, C. E.; Pandey, A. V., P450 Oxidoreductase deficiency: Analysis of mutations and polymorphisms. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2017, 165, (Pt A), 38-50. [CrossRef]

- Scott, R. R.; Gomes, L. G.; Huang, N.; Van Vliet, G.; Miller, W. L., Apparent manifesting heterozygosity in P450 oxidoreductase deficiency and its effect on coexisting 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92, (6), 2318-22. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L. G.; Huang, N.; Agrawal, V.; Mendonca, B. B.; Bachega, T. A.; Miller, W. L., The common P450 oxidoreductase variant A503V is not a modifier gene for 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008, 93, (7), 2913-6. [CrossRef]

- Hershkovitz, E.; Parvari, R.; Wudy, S. A.; Hartmann, M. F.; Gomes, L. G.; Loewental, N.; Miller, W. L., Homozygous mutation G539R in the gene for P450 oxidoreductase in a family previously diagnosed as having 17,20-lyase deficiency. J Clin Endocr Metab 2008, 93, (9), 3584-3588. [CrossRef]

- Sahakitrungruang, T.; Huang, N.; Tee, M. K.; Agrawal, V.; Russell, W. E.; Crock, P.; Murphy, N.; Migeon, C. J.; Miller, W. L., Clinical, genetic, and enzymatic characterization of P450 oxidoreductase deficiency in four patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009, 94, (12), 4992-5000. [CrossRef]

- Marohnic, C. C.; Panda, S. P.; Martasek, P.; Masters, B. S., Diminished FAD binding in the Y459H and V492E Antley-Bixler syndrome mutants of human cytochrome P450 reductase. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, (47), 35975-82. [CrossRef]

- Marohnic, C. C.; Panda, S. P.; McCammon, K.; Rueff, J.; Masters, B. S. S.; Kranendonk, M., Human Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase Deficiency Caused by the Y181D Mutation: Molecular Consequences and Rescue of Defect. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2010, 38, (2), 332-340. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. V.; Sproll, P., Pharmacogenomics of human P450 oxidoreductase. Front Pharmacol 2014, 5, 103. [CrossRef]

- Nicolo, C.; Flück, C. E.; Mullis, P. E.; Pandey, A. V., Restoration of mutant cytochrome P450 reductase activity by external flavin. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2010, 321, (2), 245-52. [CrossRef]

- Rojas Velazquez, M. N.; Noebauer, M.; Pandey, A. V., Loss of Protein Stability and Function Caused by P228L Variation in NADPH-Cytochrome P450 Reductase Linked to Lower Testosterone Levels. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, (17), 10141. [CrossRef]

- McCammon, K. M.; Panda, S. P.; Xia, C.; Kim, J. J.; Moutinho, D.; Kranendonk, M.; Auchus, R. J.; Lafer, E. M.; Ghosh, D.; Martasek, P.; Kar, R.; Masters, B. S.; Roman, L. J., Instability of the Human Cytochrome P450 Reductase A287P Variant Is the Major Contributor to Its Antley-Bixler Syndrome-like Phenotype. J Biol Chem 2016, 291, (39), 20487-502. [CrossRef]

- Campelo, D.; Lautier, T.; Urban, P.; Esteves, F.; Bozonnet, S.; Truan, G.; Kranendonk, M., The Hinge Segment of Human NADPH-Cytochrome P450 Reductase in Conformational Switching: The Critical Role of Ionic Strength. Front Pharmacol 2017, 8, 755. [CrossRef]

- Campelo, D.; Esteves, F.; Brito Palma, B.; Costa Gomes, B.; Rueff, J.; Lautier, T.; Urban, P.; Truan, G.; Kranendonk, M., Probing the Role of the Hinge Segment of Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase in the Interaction with Cytochrome P450. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, (12), 3914. [CrossRef]

- Porter, T. D.; Kasper, C. B., NADPH-cytochrome P-450 oxidoreductase: flavin mononucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide domains evolved from different flavoproteins. Biochemistry 1986, 25, (7), 1682-7. [CrossRef]

- Porter, T. D.; Kasper, C. B., Coding nucleotide sequence of rat NADPH-cytochrome P-450 oxidoreductase cDNA and identification of flavin-binding domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1985, 82, (4), 973-7. [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Hamdane, D.; Shen, A. L.; Choi, V.; Kasper, C. B.; Pearl, N. M.; Zhang, H.; Im, S. C.; Waskell, L.; Kim, J. J., Conformational changes of NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase are essential for catalysis and cofactor binding. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, (18), 16246-60. [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, P. A.; Shen, A. L.; Paschke, R.; Kasper, C. B.; Kim, J. J., NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase. Structural basis for hydride and electron transfer. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, (31), 29163-70.

- Fluck, C. E.; Parween, S.; Rojas Velazquez, M. N.; Pandey, A. V., Inhibition of placental CYP19A1 activity remains as a valid hypothesis for 46,XX virilization in P450 oxidoreductase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, (26), 14632-14633. [CrossRef]

- Flück, C. E.; Rojas Velazquez, M. N.; Pandey, A. V., Chapter 12–P450 oxidoreductase deficiency. In Genetic Steroid Disorders (Second Edition), New, M. I., Ed. Academic Press: San Diego, 2023; pp 239-264.

- Lejarraga, H.; Orfila, G., Estándares de peso y estatura para niñas y niños argentinos desde el nacimiento hasta la madurez. Arch.Argent.Pediatr. 1987, 85, 209-213.

- van der Straaten, S.; Springer, A.; Zecic, A.; Hebenstreit, D.; Tonnhofer, U.; Gawlik, A.; Baumert, M.; Szeliga, K.; Debulpaep, S.; Desloovere, A.; Tack, L.; Smets, K.; Wasniewska, M.; Corica, D.; Calafiore, M.; Ljubicic, M. L.; Busch, A. S.; Juul, A.; Nordenstrom, A.; Sigurdsson, J.; Fluck, C. E.; Haamberg, T.; Graf, S.; Hannema, S. E.; Wolffenbuttel, K. P.; Hiort, O.; Ahmed, S. F.; Cools, M., The External Genitalia Score (EGS): A European Multicenter Validation Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020, 105, (3), e222-e230.

- Marshall, W. A.; Tanner, J. M., Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1970, 45, (239), 13-23. [CrossRef]

- Anigstein, C. R., Longitud y diámetro del pene en niños de 0 a 14 años de edad. Arch.Argent.Pediatr. 2005, 103, (5), 401-405.

- Ballerini, M. G.; Chiesa, A.; Morelli, C.; Frusti, M.; Ropelato, M. G., Serum concentration of 17alpha-hydroxyprogesterone in children from birth to adolescence. Hormone research in paediatrics 2014, 81, (2), 118-25. [CrossRef]

- Ballerini, M. G.; Gaido, V.; Rodriguez, M. E.; Chiesa, A.; Ropelato, M. G., Prospective and Descriptive Study on Serum Androstenedione Concentration in Healthy Children from Birth until 18 Years of Age and Its Associated Factors. Dis Markers 2017, 2017, 9238304. [CrossRef]

- Bergadá, I.; Milani, C.; Bedecarrás, P.; Andreone, L.; Ropelato, M. G.; Gottlieb, S.; Bergadá, C.; Campo, S.; Rey, R. A., Time course of the serum gonadotropin surge, inhibins, and anti-Mullerian hormone in normal newborn males during the first month of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006, 91, (10), 4092-8. [CrossRef]

- Grinspon, R. P.; Bedecarrás, P.; Ballerini, M. G.; Iñíguez, G.; Rocha, A.; Mantovani Rodrigues Resende, E. A.; Brito, V. N.; Milani, C.; Figueroa Gacitua, V.; Chiesa, A.; Keselman, A.; Gottlieb, S.; Borges, M. F.; Ropelato, M. G.; Picard, J. Y.; Codner, E.; Rey, R. A., Early onset of primary hypogonadism revealed by serum anti-Müllerian hormone determination during infancy and childhood in trisomy 21. International Journal of Andrology 2011, 34, (5 Pt 2), e487-e498. [CrossRef]

- Saez, J. M.; Bertrand, J., Studies on testicular function in children: plasma concentrations of testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate before and after stimulation with human chorionic gonadotrophin. (1). Steroids 1968, 12, (6), 749-61. [CrossRef]

- Grinspon, R. P.; Ropelato, M. G.; Gottlieb, S.; Keselman, A.; Martínez, A.; Ballerini, M. G.; Domené, H. M.; Rey, R. A., Basal follicle-stimulating hormone and peak gonadotropin levels after gonadotropin-releasing hormone infusion show high diagnostic accuracy in boys with suspicion of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010, 95, (6), 2811-8. [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, K. J.; Francioli, L. C.; Tiao, G.; Cummings, B. B.; Alfoldi, J.; Wang, Q.; Collins, R. L.; Laricchia, K. M.; Ganna, A.; Birnbaum, D. P.; Gauthier, L. D.; Brand, H.; Solomonson, M.; Watts, N. A.; Rhodes, D.; Singer-Berk, M.; England, E. M.; Seaby, E. G.; Kosmicki, J. A.; Walters, R. K.; Tashman, K.; Farjoun, Y.; Banks, E.; Poterba, T.; Wang, A.; Seed, C.; Whiffin, N.; Chong, J. X.; Samocha, K. E.; Pierce-Hoffman, E.; Zappala, Z.; O’Donnell-Luria, A. H.; Minikel, E. V.; Weisburd, B.; Lek, M.; Ware, J. S.; Vittal, C.; Armean, I. M.; Bergelson, L.; Cibulskis, K.; Connolly, K. M.; Covarrubias, M.; Donnelly, S.; Ferriera, S.; Gabriel, S.; Gentry, J.; Gupta, N.; Jeandet, T.; Kaplan, D.; Llanwarne, C.; Munshi, R.; Novod, S.; Petrillo, N.; Roazen, D.; Ruano-Rubio, V.; Saltzman, A.; Schleicher, M.; Soto, J.; Tibbetts, K.; Tolonen, C.; Wade, G.; Talkowski, M. E.; Genome Aggregation Database, C.; Neale, B. M.; Daly, M. J.; MacArthur, D. G., The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 2020, 581, (7809), 434-443.

- Li, Q.; Wang, K., InterVar: Clinical Interpretation of Genetic Variants by the 2015 ACMG-AMP Guidelines. Am J Hum Genet 2017, 100, (2), 267-280. [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M. J.; Lee, J. M.; Benson, M.; Brown, G. R.; Chao, C.; Chitipiralla, S.; Gu, B.; Hart, J.; Hoffman, D.; Jang, W.; Karapetyan, K.; Katz, K.; Liu, C.; Maddipatla, Z.; Malheiro, A.; McDaniel, K.; Ovetsky, M.; Riley, G.; Zhou, G.; Holmes, J. B.; Kattman, B. L.; Maglott, D. R., ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, (D1), D1062-D1067. [CrossRef]

- Kitts, A.; Phan, L.; Ward, M.; Holmes, J. B., The Database of Short Genetic Variation (dbSNP). 2nd. Ed ed.; National Center for Biotechnology Information: Bethesda, MD (USA), 2019.

- Buniello, A.; MacArthur, J. A. L.; Cerezo, M.; Harris, L. W.; Hayhurst, J.; Malangone, C.; McMahon, A.; Morales, J.; Mountjoy, E.; Sollis, E.; Suveges, D.; Vrousgou, O.; Whetzel, P. L.; Amode, R.; Guillen, J. A.; Riat, H. S.; Trevanion, S. J.; Hall, P.; Junkins, H.; Flicek, P.; Burdett, T.; Hindorff, L. A.; Cunningham, F.; Parkinson, H., The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, (D1), D1005-D1012. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, A.; Mahamdallie, S.; Ruark, E.; Seal, S.; Ramsay, E.; Clarke, M.; Uddin, I.; Wylie, H.; Strydom, A.; Lunter, G.; Rahman, N., Accurate clinical detection of exon copy number variants in a targeted NGS panel using DECoN. Wellcome Open Res 2016, 1, 20. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. V.; Kempna, P.; Hofer, G.; Mullis, P. E.; Flück, C. E., Modulation of human CYP19A1 activity by mutant NADPH P450 oxidoreductase. Mol Endocrinol 2007, 21, (10), 2579-95. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. V.; Flück, C. E.; Mullis, P. E., Altered heme catabolism by heme oxygenase-1 caused by mutations in human NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010, 400, (3), 374-8. [CrossRef]

- Parween, S.; Rojas Velazquez, M. N.; Udhane, S. S.; Kagawa, N.; Pandey, A. V., Variability in Loss of Multiple Enzyme Activities Due to the Human Genetic Variation P284T Located in the Flexible Hinge Region of NADPH Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2019, 10, 1187. [CrossRef]

- Faeder, E. J.; Siegel, L. M., A rapid micromethod for determination of FMN and FAD in mixtures. Anal Biochem 1973, 53, (1), 332-6. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. V.; Miller, W. L., Regulation of 17,20 lyase activity by cytochrome b5 and by serine phosphorylation of P450c17. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, (14), 13265-71. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. V.; Mellon, S. H.; Miller, W. L., Protein phosphatase 2A and phosphoprotein SET regulate androgen production by P450c17. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, (5), 2837-44. [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, J.; Natsaridis, E.; du Toit, T.; Barata, I. S.; Tagit, O.; Pandey, A. V., Nanoparticles with curcumin and piperine modulate steroid biosynthesis in prostate cancer. Sci Rep 2025, 15, (1), 13613. [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, T. M.; Grudzinska, A.; Yakubu, J.; du Toit, T.; Sharma, K.; Harrington, J. C.; Bjorkling, F.; Jorgensen, F. S.; Pandey, A. V., Pyridine indole hybrids as novel potent CYP17A1 inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2025, 40, (1), 2463014. [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, T. M.; Sharma, K.; Mannella, I.; Oliaro-Bosso, S.; Nieckarz, P.; Du Toit, T.; Voegel, C. D.; Rojas Velazquez, M. N.; Yakubu, J.; Matveeva, A.; Therkelsen, S.; Jorgensen, F. S.; Pandey, A. V.; Pippione, A. C.; Lolli, M. L.; Boschi, D.; Bjorkling, F., Exploring the Potential of Sulfur Moieties in Compounds Inhibiting Steroidogenesis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, (9), 1349. [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, T. M.; Rogova, O.; Sharma, K.; Rojas Velazquez, M. N.; Pandey, A. V.; Jorgensen, F. S.; Arendrup, F. S.; Andersen, K. L.; Bjorkling, F., Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationships of Novel Non-Steroidal CYP17A1 Inhibitors as Potential Prostate Cancer Agents. Biomolecules 2022, 12, (2), 165. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Lanzilotto, A.; Yakubu, J.; Therkelsen, S.; Voegel, C. D.; Du Toit, T.; Jorgensen, F. S.; Pandey, A. V., Effect of Essential Oil Components on the Activity of Steroidogenic Cytochrome P450. Biomolecules 2024, 14, (2), 203. [CrossRef]

- Prado, M. J.; Singh, S.; Ligabue-Braun, R.; Meneghetti, B. V.; Rispoli, T.; Kopacek, C.; Monteiro, K.; Zaha, A.; Rossetti, M. L. R.; Pandey, A. V., Characterization of Mutations Causing CYP21A2 Deficiency in Brazilian and Portuguese Populations. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23, (1), 296. [CrossRef]

- Malikova, J.; Brixius-Anderko, S.; Udhane, S. S.; Parween, S.; Dick, B.; Bernhardt, R.; Pandey, A. V., CYP17A1 inhibitor abiraterone, an anti-prostate cancer drug, also inhibits the 21-hydroxylase activity of CYP21A2. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2017, 174, 192-200. [CrossRef]

- Udhane, S. S.; Dick, B.; Hu, Q.; Hartmann, R. W.; Pandey, A. V., Specificity of anti-prostate cancer CYP17A1 inhibitors on androgen biosynthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 477, (4), 1005-10. [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, M. N. R.; Parween, S.; Udhane, S. S.; Pandey, A. V., Variability in human drug metabolizing cytochrome P450 CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP3A5 activities caused by genetic variations in cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 515, (1), 133-138. [CrossRef]

- Parween, S.; Rojas Velazquez, M. N.; Udhane, S. S.; Kagawa, N.; Pandey, A. V., Variability in Loss of Multiple Enzyme Activities Due to the Human Genetic Variation P284T Located in the Flexible Hinge Region of NADPH Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10, 1187. [CrossRef]

- Udhane, S. S.; Parween, S.; Kagawa, N.; Pandey, A. V., Altered CYP19A1 and CYP3A4 Activities Due to Mutations A115V, T142A, Q153R and P284L in the Human P450 Oxidoreductase. Front Pharmacol 2017, 8, 580. [CrossRef]

- Parween, S.; DiNardo, G.; Baj, F.; Zhang, C.; Gilardi, G.; Pandey, A. V., Differential effects of variations in human P450 oxidoreductase on the aromatase activity of CYP19A1 polymorphisms R264C and R264H. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2020, 196, 105507. [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Panda, S. P.; Marohnic, C. C.; Martasek, P.; Masters, B. S.; Kim, J. J., Structural basis for human NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, (33), 13486-91. [CrossRef]

- Hamdane, D.; Xia, C. W.; Im, S. C.; Zhang, H. M.; Kim, J. J. P.; Waskell, L., Structure and Function of an NADPH-Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase in an Open Conformation Capable of Reducing Cytochrome P450. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284, (17), 11374-11384. [CrossRef]

- Shen, A. L.; Porter, T. D.; Wilson, T. E.; Kasper, C. B., Structural analysis of the FMN binding domain of NADPH-cytochrome P-450 oxidoreductase by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem 1989, 264, (13), 7584-9. [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.; Porter, T.; Wilson, T.; Kasper, C. B., Characterization of the Fmn Binding Domain of Nadph-Cytochrome-P-450 Oxidoreductase. Faseb Journal 1988, 2, (4), A355-A355.

- Esteves, F.; Campelo, D.; Gomes, B. C.; Urban, P.; Bozonnet, S.; Lautier, T.; Rueff, J.; Truan, G.; Kranendonk, M., The Role of the FMN-Domain of Human Cytochrome P450 Oxidoreductase in Its Promiscuous Interactions With Structurally Diverse Redox Partners. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11, (299). [CrossRef]

- Vermilion, J. L.; Ballou, D. P.; Massey, V.; Coon, M. J., Separate roles for FMN and FAD in catalysis by liver microsomal NADPH-cytochrome P-450 reductase. J Biol Chem 1981, 256, (1), 266-77. [CrossRef]

- Flück, C. E.; Pandey, A. V.; Huang, N.; Agrawal, V.; Miller, W. L., P450 oxidoreductase deficiency–a new form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Endocr Dev 2008, 13, 67-81.

- Reisch, N.; Idkowiak, J.; Hughes, B. A.; Ivison, H. E.; Abdul-Rahman, O. A.; Hendon, L. G.; Olney, A. H.; Nielsen, S.; Harrison, R.; Blair, E. M.; Dhir, V.; Krone, N.; Shackleton, C. H. L.; Arlt, W., Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Caused by P450 Oxidoreductase Deficiency. J Clin Endocr Metab 2013, 98, (3), E528-E536. [CrossRef]

- Krone, N.; Reisch, N.; Idkowiak, J.; Dhir, V.; Ivison, H. E.; Hughes, B. A.; Rose, I. T.; O’Neil, D. M.; Vijzelaar, R.; Smith, M. J.; MacDonald, F.; Cole, T. R.; Adolphs, N.; Barton, J. S.; Blair, E. M.; Braddock, S. R.; Collins, F.; Cragun, D. L.; Dattani, M. T.; Day, R.; Dougan, S.; Feist, M.; Gottschalk, M. E.; Gregory, J. W.; Haim, M.; Harrison, R.; Olney, A. H.; Hauffa, B. P.; Hindmarsh, P. C.; Hopkin, R. J.; Jira, P. E.; Kempers, M.; Kerstens, M. N.; Khalifa, M. M.; Kohler, B.; Maiter, D.; Nielsen, S.; O’Riordan, S. M.; Roth, C. L.; Shane, K. P.; Silink, M.; Stikkelbroeck, N. M. M. L.; Sweeney, E.; Szarras-Czapnik, M.; Waterson, J. R.; Williamson, L.; Hartmann, M. F.; Taylor, N. F.; Wudy, S. A.; Malunowicz, E. M.; Shackleton, C. H. L.; Arlt, W., Genotype-Phenotype Analysis in Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia due to P450 Oxidoreductase Deficiency. J Clin Endocr Metab 2012, 97, (2), E257-E267. [CrossRef]

- Ono, H.; Numakura, C.; Homma, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Tsutsumi, S.; Kato, F.; Fujisawa, Y.; Fukami, M.; Ogata, T., Longitudinal serum and urine steroid metabolite profiling in a 46,XY infant with prenatally identified POR deficiency. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2018, 178, 177-184. [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Kawai, K.; Tatsumi, K.; Miyado, M.; Katsumi, M.; Nakamura, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Miyasaka, N.; Fukami, M., POR mutations as novel genetic causes of female infertility due to partial 17 alpha-hydroxylase deficiency. Hum Reprod 2017, 32, 104-105.

- Fukami, M.; Ogata, T., Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase deficiency: rare congenital disorder leading to skeletal malformations and steroidogenic defects. Pediatr Int 2014, 56, (6), 805-808. [CrossRef]

- Aigrain, L.; Pompon, D.; Morera, S.; Truan, G., Structure of the open conformation of a functional chimeric NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase. EMBO Rep 2009, 10, (7), 742-7. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W. L.; Pandey, A. V.; Flück, C. E., Disordered Electron Transfer: New Forms of Defective Steroidogenesis and Mitochondriopathy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2025, 110, (3), e574-e582. [CrossRef]

- Sahakitrungruang, T.; Huang, N. W.; Tee, M. K.; Agrawal, V.; Russell, W. E.; Crock, P.; Murphy, N.; Migeon, C. J.; Miller, W. L., Clinical, Genetic, and Enzymatic Characterization of P450 Oxidoreductase Deficiency in Four Patients. J Clin Endocr Metab 2009, 94, (12), 4992-5000. [CrossRef]

| Vmax (nmol/min/ mmol of POR) |

Km (µM) |

Vmax/Km (% of WT) |

|

| Cytochrome c reduction activity | |||

| WT | 78.1 | 4.6 | 16.9 (100) |

| G88S | 19.9 | 39.5 | 0.5 (2.93) |

| MTT reduction activity | |||

| WT | 44.8 | 138.4 | 0.32 (100) |

| G88S | 68 | 805 | 0.08 (26) |

| Resazurin reduction activity | |||

| WT | 2197 | 22 | 101 (100) |

| G88S | 207 | 27 | 8 (8) |

| Molecular Finding | In Vitro Functional Consequence | Clinical/Biochemical Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Homozygous G88S mutation in FMN domain | Catastrophic loss of FMN and FAD (<30, <15%) due to dynamic protein instability | Severe P450 Oxidoreductase Deficiency (PORD) |

| CYP21A2 (21-hydroxylase) activity at 1.3% of WT | Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia: High 17OHP & Progesterone; Low/inadequate Cortisol; High ACTH | |

| CYP17A1 (17,20-lyase) activity at 5.5% of WT | Gonadal Dysfunction: 46,XY undervirilization (impaired Testosterone); 46,XX delayed puberty (impaired Estradiol) | |

| CYP3A4/5, 2C9, 2C19 activity at 3-9% of WT | Lifelong Pharmacogenomic Risk: “Pan-poor metabolizer” phenotype; High risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) | |

| Variable (Modifier |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).