1. Introduction

According to Newton’s law of universal gravitation, in a galaxy where mass is predominantly concentrated at the center, the orbital velocities of stars and gas in the outer regions should decrease with increasing distance. However, since the 1970s, systematic observations by Vera Rubin [

1] and others on numerous spiral galaxies have revealed a universal phenomenon: rotation curves remain flat rather than declining beyond the optical radius. This anomaly strongly suggests the presence of additional mass far exceeding that of visible matter. Consequently, “dark matter” was proposed as the mainstream explanation for this phenomenon and has gradually become a cornerstone of the standard cosmological model (ΛCDM). Evidence supporting dark matter is widely found in galaxy cluster dynamics, gravitational lensing, cosmic microwave background anisotropies, and other independent observational domains.

Although dark matter has achieved great success on large cosmological scales, it still faces a series of persistent challenges at galactic scales. For instance, the “core-cusp problem” indicates that cold dark matter simulations predict density profiles that disagree with observations; the “missing satellites problem” shows that simulations predict many more dwarf satellite galaxies than are actually observed; even more striking is the “radial acceleration relation” (RAR), which reveals a tight correlation between the observed dynamical acceleration and the distribution of baryonic matter in galaxies—something difficult to explain naturally within frameworks assuming independent distributions of dark and baryonic matter. Recently, a new study, using weak gravitational lensing showed rotational curves of galaxies of different morphology have flat rotation curves for very large radii, extending even beyond 1 Mpc (Mistele et al. 2024a) [

2]. These galaxy-scale anomalies, which challenge the dark matter paradigm, prompt us to reconsider: could it be that we have misunderstood gravity itself?

In this context, Mordehai Milgrom proposed Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) in 1983. The theory assumes that in the weak-field regime, where acceleration falls below a critical value, Newtonian dynamics must be modified. MOND [

3] can fit the rotation curves of numerous isolated spiral galaxies with high precision without invoking dark matter, and naturally reproduces empirical relations such as the Tully-Fisher relation. However, MOND has long been regarded as a purely phenomenological model: it lacks a theoretical foundation derived from fundamental physical principles (such as an action principle or symmetry), its original form does not satisfy energy and momentum conservation, and it struggles to extend to general gravitational systems or relativistic frameworks.

Therefore, constructing a self-consistent new gravitational theory from existing physics—particularly starting from Newton’s law of universal gravitation—that maintains consistency with conservation laws while naturally recovering known gravitational behaviors in different geometries would be profoundly significant. This paper aims to achieve precisely this goal. Starting from Newton’s law of universal gravitation, and incorporating the superposition properties of gravitational fields in non-spherical systems along with boundary condition effects, we derive a new gravitational field equation. This equation strictly reduces to Newtonian gravity in spherically symmetric systems, ensuring its validity in traditional domains such as the solar system and stellar systems; meanwhile, in flattened systems like disk galaxies, the solutions to this equation closely match MOND predictions, naturally explaining the flattening of rotation curves.

This theoretical advance suggests that the empirical regularities captured by MOND may not be artificially constructed fitting formulas, but rather a natural extension of Newtonian gravity under specific geometric configurations (such as thin disk systems). More importantly, the theory is built upon rigorous mathematical derivation and clear physical assumptions, satisfies fundamental conservation laws, and avoids the theoretical shortcomings of conventional MOND. If this framework holds, then the so-called “dark matter signal” in galaxies might originate not from unknown particles, but from an incomplete understanding of how gravitational fields behave in realistic, non-spherical structures. This theoretical advance suggests that the empirical regularities captured by MOND may not be artificially constructed fitting formulas, but rather a natural extension of Newtonian gravity under specific geometric configurations (such as thin disk systems). More importantly, the theory is built upon rigorous mathematical derivation and clear physical assumptions, satisfies fundamental conservation laws, and avoids the theoretical shortcomings of conventional MOND. If this framework holds, then the so-called “dark matter signal” in galaxies might originate not from unknown particles, but from an incomplete understanding of how gravitational fields behave in realistic, non-spherical structures

2. The Upgraded Form of Newtonian Gravitational Equation

The Newtonian gravity equation

The equation works very well for systems where the masses can be approximated as spheres, such as the Earth or the Sun. When the distance between an object

m and a spherical mass

M is

r, the gravitational force between them is always

Fg. Since the position of

m is not a specific point but can be any point at a distance of

r, and all these points form a spherical surface with a radius of

r. Therefore, it can be considered that gravity is effectively distributed over the surface area of the sphere. While the original equation is based on the concept of point masses, we can reformulate it to consider the distribution of gravity over a surface

S represents the surface area of the surface where

m is located, and

G’ is the modified gravitational constant.

When

M is spherical, the surface area of

M is

4.

When

M is spherical, equation (2) equals to Newton’s. So it can be concluded that

Equation (6) is the upgraded form of Newtonian gravitational equation.

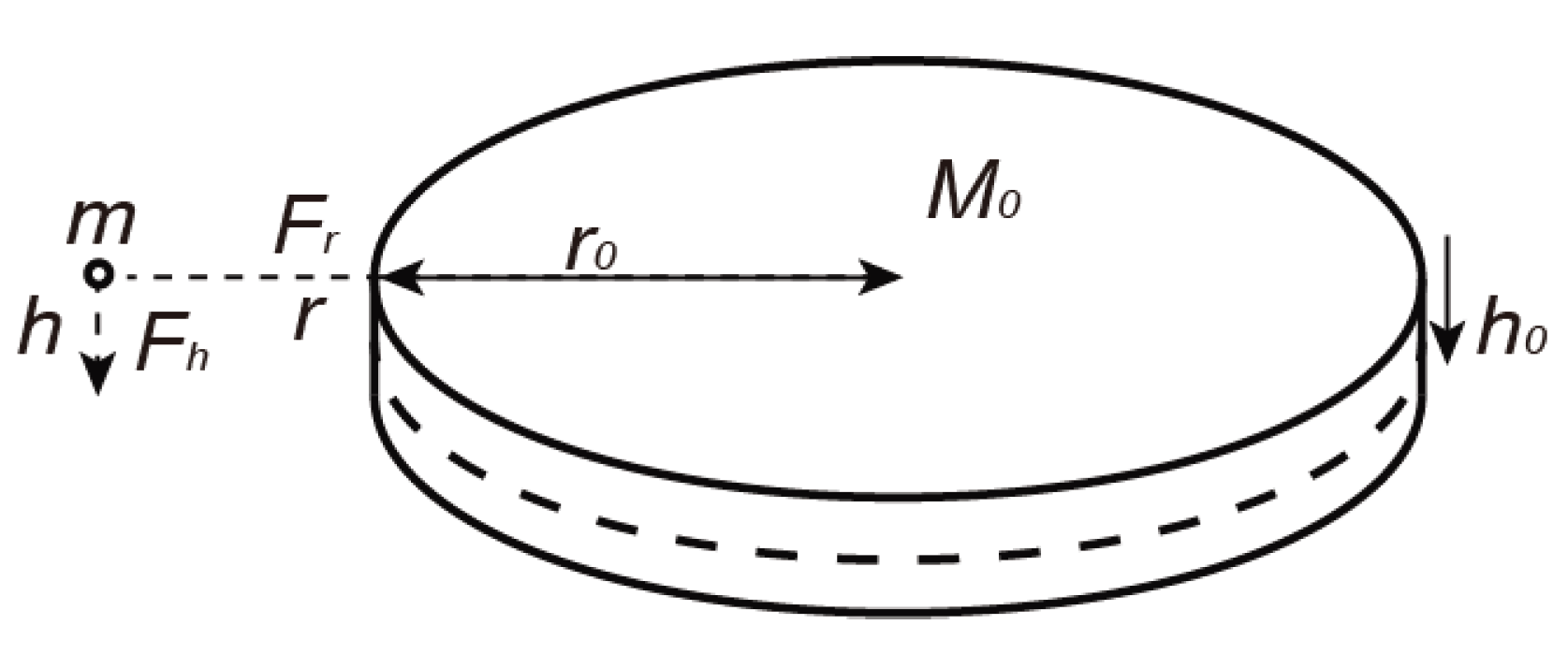

3. The Upgraded Equation in Disk Systems

When

M is a disk (Flat cylinder)

Figure 1, it has 3 surfaces, side, top and the bottom.

Sr0 represents the side surface,

Sh0 represents the sum area of top and the bottom surface.

r0 is the radius of the disk,

h0 is half height,

2h0 is the total height.

r is the radial distance between

m and

M.

h is the height from the center plane of the disk to

m, the minimum value of

h is

hmin=h0 when

m is located on the center plane.

Based on equation (6),

Fr represents the radial force on the side surface,

Mr is radial mass;

Fh represents vertical force,

Mh is vertical mass;

Sr is the area of the cylindrical surface where

m is located,

Sr varies with

r and

h;

Sh is the sum area of the top and bottom surface,

Sh varies with

r,

M0 is the total mass of

M,

S0 is the total area of

M. The mass distributed in these two directions is equal to the ratio of their area to the total area,

Mr and

Mh respectively represent.

These are the two gravitational forces (

Fr and

Fh) that an object experiences in a disk gravitational system.

Fr is always perpendicular to and pointing towards the central axis,

Fh is always perpendicular to and pointing towards the central disk plane.

F0 the net force of gravity. In the system

h0 and

r0 are constant.

4. The Rotational Motion in the Disk System

The radial force

Fr provides the centripetal force for

m to rotate around the center, and under the action of

Fh,

m will periodically move up and down in the vertical direction.

The two accelerations

ar and

ah in two distinct directions.

ar always points toward the central axis, providing a radial acceleration to the object

m to rotate around

M. Meanwhile, vertical acceleration

ah always points toward the central plane, driving

m to move toward the center plane of

M.

The rotation velocity

vr depends not on the radial distance

r, but solely on the height

h. This means that regardless of how far the object

m is away from

M in the radial direction, its rotation velocity always remains the same when

h is constant. The result of equations (28) and (29) is remarkably similar to that of MOND: when the height remains constant, the centripetal acceleration

a is inversely proportional to the radial distance

r (

a∝1/r), rather than to

r2.

5. Discussion

The proposed theoretical framework presents several key distinctions from existing approaches, particularly from Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND), while also offering deeper insights into the nature of gravity and its connection to geometry.

First, unlike MOND—whose original formulation is based on an empirical ansatz designed to fit galactic rotation curves without a rigorous theoretical foundation—our model is derived from a consistent physical and mathematical framework. MOND, in its initial form, lacks a clear derivation from fundamental principles and violates standard conservation laws such as energy and momentum in isolated systems. In contrast, the present theory provides a complete and self-consistent derivation rooted in classical gravitational dynamics within specific geometric configurations. Crucially, it unifies both Newtonian gravity and MOND-like behavior under a single formalism: in appropriate limits (e.g., spherical symmetry or point-mass approximations), it recovers standard inverse-square law behavior; in disk-like or extended planar systems with fixed height, it naturally yields a∝1/r, reproducing the core prediction of MOND without introducing ad hoc modifications to gravity or inertia.

Second, this model reveals a profound link between gravity and geometry. Specifically, it demonstrates that gravitational effects depend not only on mass and distance but also on the surface area associated with the mass distribution—particularly the effective cross-sectional or bounding surface through which field lines pass. Since surface area is inherently a geometric quantity, this suggests that gravity exhibits intrinsic geometric dependence. This finding resonates strongly with the geometric interpretation of gravity in general relativity, where gravitation arises from the curvature of spacetime. While our model operates within a classical context, the emergence of geometric sensitivity supports the broader idea that gravity is fundamentally tied to the shape and topology of matter distributions, reinforcing the notion that geometric principles may underlie gravitational phenomena across scales.

Third, the role of the gravitational constant G must be re-evaluated in light of this theory. Traditionally, G is determined experimentally in systems with approximate spherical symmetry (e.g., Cavendish-type experiments). However, our results suggest that what we measure as “G” may in fact be a shape-dependent effective parameter, denoted here as G′, whose value depends on the global geometry of the mass distribution. In other words, G′may not be a universal constant across all configurations, but rather a coefficient that varies with system morphology—constant only within certain symmetric classes (spherical, cylindrical, etc.). This implies that apparent discrepancies in gravitational measurements at different scales could partially stem from unaccounted geometric effects, rather than requiring new physics or dark components.

Finally, extending this framework to more complex systems—such as triaxial ellipsoids—reveals even richer dynamical behavior. Unlike spherical systems characterized by a single parameter (radius) or axisymmetric bodies like cylinders and disks (two parameters), ellipsoids are defined by three principal axes, all of which can vary with position in a non-uniform medium. This increased degree of freedom leads to highly anisotropic and potentially chaotic orbital dynamics, where accelerations and forces lack simple radial symmetry. Such complexity may explain the irregular velocity dispersions and non-Keplerian motions observed in elliptical galaxies and galaxy clusters, suggesting that geometric diversity alone can contribute significantly to observed gravitational anomalies.

In summary, this theory not only accounts for both Newtonian and MOND-like regimes within a unified, physically grounded framework but also highlights the critical role of geometry in shaping gravitational interactions. It challenges the universality of G as a constant and opens new avenues for interpreting gravitational phenomena through the lens of system morphology—potentially reducing the need for dark matter or modified dynamics in certain astrophysical contexts.

6. Predictions

Based on the theoretical framework presented in this work, several testable predictions can be made regarding the dynamical behavior of astrophysical systems under different geometric configurations. These predictions not only validate the consistency of the model with observational data but also provide new insights into the role of system morphology in gravitational dynamics.

Spherical systems follow Newtonian dynamics: The theory predicts that the more closely a mass distribution approaches spherical symmetry, the more its dynamical behavior aligns with classical Newtonian gravity—specifically, rotation curves should exhibit decline at large radii. This is consistent with observations of elliptical galaxies and galaxy clusters that are nearly spherical, where velocity dispersions decrease with radius and do not require dark matter halos to explain their kinematics within certain scales.

Disk-like systems exhibit flat or slowly varying rotation curves: For systems with pronounced disk geometry—such as spiral galaxies—the theory predicts that rotational motion will conform to the derived scaling laws, yielding approximately flat rotation curves when the vertical height h remains constant. This matches the well-known observation that spiral galaxies display nearly constant rotational velocities beyond a certain radius, traditionally attributed to dark matter. However, according to this model, such behavior emerges naturally from the interplay between radial distance and fixed vertical extent, without invoking unseen mass.

Rotation speeds vary periodically with vertical oscillations: Crucially, the model makes a novel prediction: while rotational velocity becomes asymptotically flat when h is constant, it should exhibit periodic fluctuations if m undergoes vertical motion (i.e., “bobbing” up and down through the disk plane). Since the predicted velocity depends inversely on h, any oscillation in height results in a corresponding modulation of the rotational speed.

Remarkably, high-resolution observations of spiral galaxies reveal precisely such features: rotation curves are not perfectly horizontal lines, but exhibit measurable ripples and wiggles correlated with spiral structure and vertical motions. These subtle fluctuations have no natural explanation in standard dark matter halo models, which predict smooth circular velocity profiles. In contrast, this model provides a direct physical mechanism for these modulations—linking them to the coupling between vertical dynamics and rotational velocity through geometric dependence.

These predictions highlight the power of the present theory in explaining both large-scale trends and fine structures in galactic kinematics. Importantly, they suggest that gravitational anomalies previously interpreted as evidence for dark matter may instead reflect the geometric complexity of real astrophysical systems, particularly their deviation from spherical symmetry.

Future observational tests—especially detailed mapping of stellar kinematics in the vertical direction combined with azimuthal velocity profiles—can directly verify the predicted correlation between h(t) oscillations and rotational speed modulations, offering a decisive test of this geometric gravitational framework.

7. Conclusion

In this work, we have developed a new theoretical framework for gravitational dynamics based on a rigorous extension of Newton’s law of universal gravitation to non-spherical systems. By incorporating the superposition of gravitational fields and the influence of geometric boundary conditions—particularly the effective surface area through which field lines pass—we derive a field equation that unifies classical Newtonian behavior and MOND-like phenomenology within a single, physically grounded model.

The theory successfully explains the flat rotation curves of spiral galaxies as a natural consequence of disk geometry, without requiring dark matter. It recovers Newtonian dynamics in spherical systems—consistent with observations of elliptical galaxies and globular clusters—and reproduces the a∝1/r scaling in thin disks, matching the core prediction of MOND. Unlike MOND, however, this model is not an empirical fit but a result of consistent mathematical derivation from classical principles, and it respects energy and momentum conservation.

Furthermore, the theory establishes a profound link between gravity and geometry, echoing the geometric nature of general relativity but within a classical context. It suggests that the gravitational “constant” G is not universal, but rather an effective parameter G’ that depends on the shape and symmetry of the mass distribution—constant only within specific geometric classes. This insight may help resolve long-standing tensions in gravitational measurements across different scales.

We have also made several testable predictions: first, that rotational dynamics transition smoothly from Keplerian decline to flat curves as system geometry evolves from spherical to disk-like; second, that in disk galaxies, rotation speed depends on the vertical height h of orbiting masses; and third, that vertical oscillations lead to observable periodic modulations in rotation curves—precisely the kind of small-scale ripples seen in high-resolution data.

These results challenge the conventional interpretation of galactic anomalies as evidence for dark matter. Instead, they suggest that the observed dynamics may arise from an incomplete treatment of gravity in non-spherical systems. If validated, this geometric gravitational framework could revolutionize our understanding of galaxy dynamics, offering a compelling alternative to dark matter—one that requires no new particles, only a deeper appreciation of how classical gravity behaves in the complex shapes of real astrophysical systems.

Appendix A. Calculation of Galactic Mass

The radial acceleration

ar, it is not inversely proportional to the square of

r, but to the product of

r and

h. The rotation speed

vr is not directly related to the radius, but is inversely proportional to the height. These results are significantly different from those calculated by Newton’s gravity equation. When the mass tends to be constant and the height remains constant, the rotational speed will not change, regardless of the radius. This result is consistent with the flatness of the observed rotation curve of the galaxies. However, the observed rotation curve does not always remain flat but has slight fluctuations, it can be explained as a result of different heights.

| Galactic parameters from NASA (Approximate parameters when the rotation curve tends to flatten) |

| rotational speed (vr) |

Average thickness (2h0) |

Radius (r0) |

gravitational constant (G) |

solar mass (M) |

| ≈220km/s |

1 000 light year |

23 000 light year |

6.67×10-11m3kg-1s-2

|

2×1030kg |

| ≈2.2×105m/s |

≈1 000×9.45×1015m |

≈23 000×9.45×1015m |

|

|

Here,

h=h0

Only 4.29×10

10 times the mass of the sun is required to reach a rotation speed of 220km/s.

References

- Rubin, V. C., & Ford, W. K., Jr. (1970). Rotation of the Andromeda Nebula from a spectroscopic survey of emission regions. The Astrophysical Journal, 159, 379. [CrossRef]

- Mistele, T., McGaugh, S., Lelli, F., Schombert, J., & Li, P. Indefinitely Flat Circular Velocities and the Baryonic Tully-Fisher Relation from Weak Lensing. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2024, 969, 1–10.

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. The Astrophysical Journal, 1983, 270, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).