1. Introduction

Since the discovery of superhydrophobicity and the so-called lotus leaf effect, scientists have kept high interest in engineering un-wettable surfaces. Superhydrophobic (SHP) materials are typically defined by static contact angles greater than 150°, contact angle hysteresis below 10°, and roll-off angles under 5° [

1]. These properties are a result of a combination of hierarchical micro/nanoscale roughness and low surface energy coatings.

Due to their complete water repellency, such surfaces demonstrate advanced functionalities, including self-cleaning, anti-corrosion, and also ice and snow repulsion. Applications span from biomedical devices [

2], to overhead power lines [

3], aircraft technologies [

4] heritage protection [

5], and even road pavings [

6].

SHP surfaces can be fabricated using several techniques to create an appropriate texturized surface such as laser treatment [

7], lithography [

8], sandblasting [

9], wet chemical treatment [

10], chemical etching [

11], followed by functionalization with low surface energy molecules. Some of these methods yield highly performing surfaces, at the cost of often being complex, pricey, and difficult to scale. Conversely, simpler and more scalable processes may lead to less optimized and more irregular morphologies resulting in surfaces with reduced hydrophobicity and associated functionalities. Thus, the development of high-performance SHP surfaces via a simple and cost-effective process remains a highly desirable objective.

A clear example of functional loss regards icephobicity of SHP surfaces: despite many studies report reduced ice adhesion [

12,

13,

14], the debate remains open. Indeed several works showed limited effectiveness under specific environmental conditions, with the underlying reasons and mechanisms only partially unveiled [

15,

16,

17].

This study aims to investigate how surface roughness and morphology influence wettability properties and icephobic performance of hydrophobic and SHP aluminum. The samples are fabricated through a simple and scalable process involving chemical etching, boiling treatment, and fluoroalkylsilane (FAS) functionalization.

By varying parameters such as etchant concentration, immersion time, and boiling duration, we obtained surfaces with different roughness. These surfaces exhibited icephobic performances spanning in various degrees from poor to excellent, in some cases uncorrelated to their wettability.

This study aims to provide insights into the design of anti-icing surfaces and to identify the key features required for developing scalable, low-wettability, icephobic materials.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

Flat plates (20 mm × 70 mm × 2 mm) and bars (12 mm diameter × 100 mm length) of aluminum alloy (6082) were used as substrates.

Dynasylan® SIVO CLEAR EC was purchased from EVONIK (Essen, Germany); the product is composed of fluoroalkylsilane (FAS) 2%, propan-2-ol 93% and dodecane 5%, and was used as received.

Acetone (>99.5%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (S. Louis, MI, USA). Ethanol (≥99.9%) and hydrochloric acid (36%) were purchased from Carlo Erba (Milan, Italy). All reagents were used without further treatments.

Characterization Methods

Surface morphologies of the prepared surfaces were examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; Mira III, Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic) before the coating with FAS (step 3).

A Taylor Hobson stylus profilometer was used to measure surface roughness. Data were averaged over at least 5 runs for each sample.

The FT-IR characterizations were conducted on the prepared surfaces with the FT-IR Alpha 1 (Bruker) spectrometer with ATR apparatus (with diamond crystal as the internal reflection element), before the coating with FAS (step 3).

The static water contact angles (SCA) were measured with the DSA 30 Drop Shape Analyzer (Kruss, Hamburg, Germany) with sessile drop method using 4 μL volume of water. The measurements of roll-off angle (RO) were performed with the tilting plate method using a 20 μL water volume. The measurements of advancing and receding contact angles were carried out with the needle-in method starting from a 4 μL volume of water droplet. The droplet volume was increased at 1 µL/s, and the advancing contact angle was measured when the contact point started to move outward. Then, water was withdrawn from the droplet and the receding contact angle was measured when the contact point started to retract. The contact angle hysteresis (H) was calculated as the difference between the advancing and receding contact angles. All wettability measures were done at 23±2 °C and at least 5 measures in different points for each sample were executed.

The ice adhesion strength was evaluated by means of the shear force needed to extract a sample pole from an ice block. A home-made apparatus equipped with an electromechanical testing system (INSTRON 4507), described in a previous work [

9], was employed (see also

Figure S1). The ice adhesion strength (τ) in shear can thus be calculated as:

where F is the peak-force needed to extract the sample pole from the ice and A is the surface of the bar in contact with the ice. The shear stresses were measured on 10 different specimens for each treatment.

The ice adhesion of bare Al alloy was also measured as reference and an adhesion reduction factor (ARF) was calculated as:

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this paper to enhance the quality of English language.

Preparation of Samples

All the aluminum alloy specimens were cleaned with basic soap, rinsed in ultrasonic bath for 10 min with acetone and dried under nitrogen flux.

The etched samples were prepared through a three-steps process: 1) micro-roughness formation, 2) nano-roughness growth; 3) surface functionalization with FAS.

In the first step different aluminum alloy plates were etched in HCl solutions with three different concentrations (0.5, 1 or 3 M) for different time frames (15, 30 or 60 minutes). After the immersion in HCl samples were accurately rinsed with deionized water in ultrasound bath.

In the second step some samples were immersed in deionized water at 100 °C for different times (5 or 30 minutes) and then dried at 100 °C for 1 hour in a laboratory oven. Samples without further treatment in boiling water were also prepared.

In the third step, all surfaces were dip-coated in the FAS solution with the following conditions: immersion speed 0.7 mm/s, permanence time 2 minutes, extraction speed 0.7 mm/s. Samples were then heat-treated at 120 °C for 1 hour.

From this point onward, samples are labeled based on their etching and boiling treatments using an abbreviation system. The first letter indicates the HCl concentration (L = 0.5 M, I = 1 M, H = 3 M, where L = low, I = Intermediate, H = high), the second letter denotes the immersion time in HCl (S = 15 min, M = 30 min, L = 60 min, where S = short, M = medium, L = long), and the number represents the immersion time in boiling water (0, 5, or 30 minutes).

As reference samples, ‘Pristine’ was prepared as described above, but omitting steps 1 and 2, while ‘Nano-5’ was prepared without step 1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological and Chemical Evaluation of the Texturized Surfaces

HCl reacts with aluminum surfaces, oxidizing the metal and producing AlCl

3 and H

2. HCl initiates the etching process from surface defects (e.g., grain boundary and surface dislocations) and after certain times cavities on the surface are formed. Prolonging the immersion time, the surfaces become more uniform and texturized [

18].

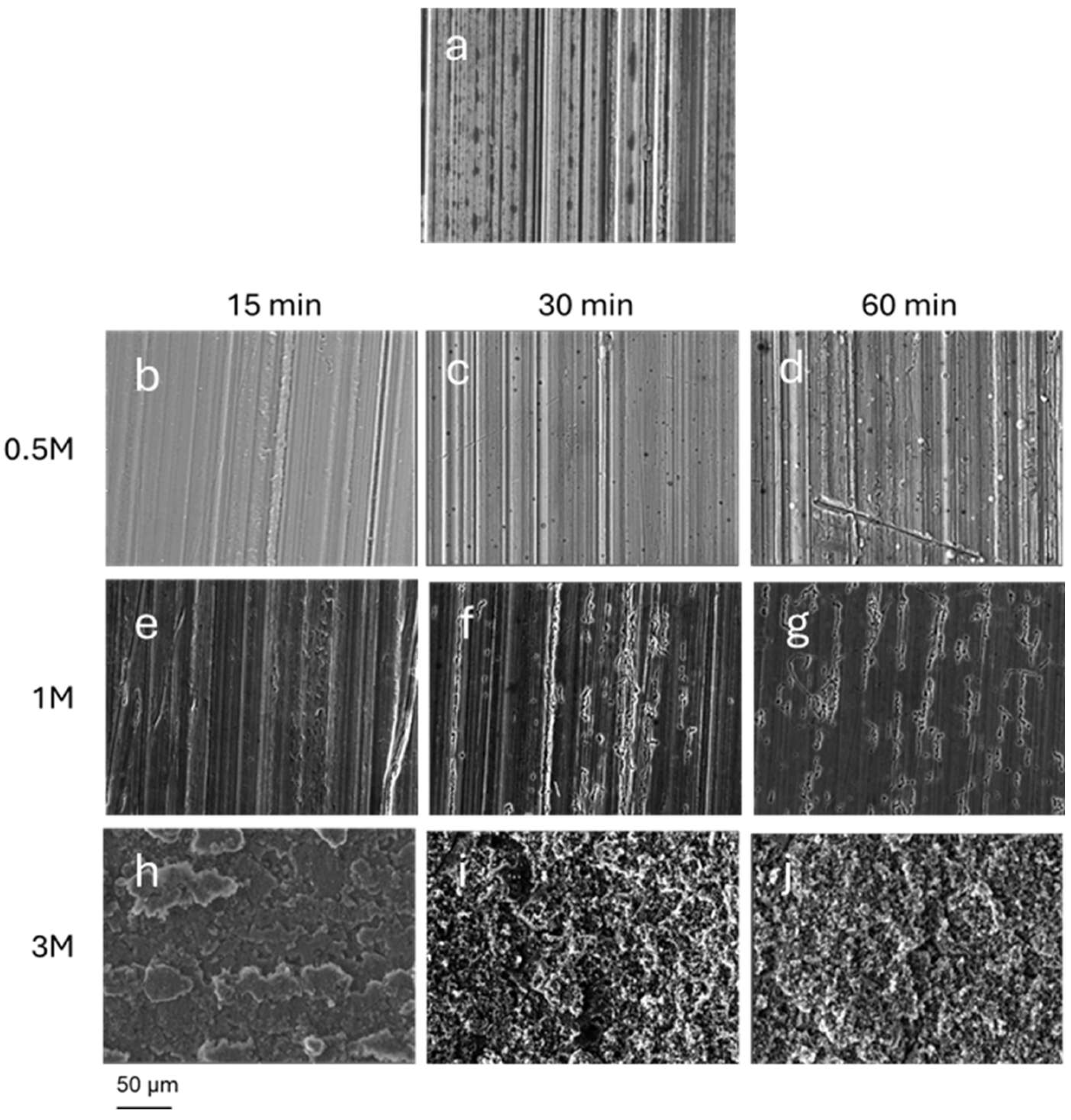

SEM analysis shows that depending on the concentration of the etchant and the immersion time, different micro-roughed textures were obtained with respect to the starting Pristine surface, as shown in

Figure 1.

More diluted HCl primarily etches areas of the surface where native roughness, originating from the manufacturing process, is present, deepening the longitudinal grooves proportionally to treatment duration.

By increasing the concentration of HCl, rougher surfaces with well-marked grain boundaries and cavities are obtained.

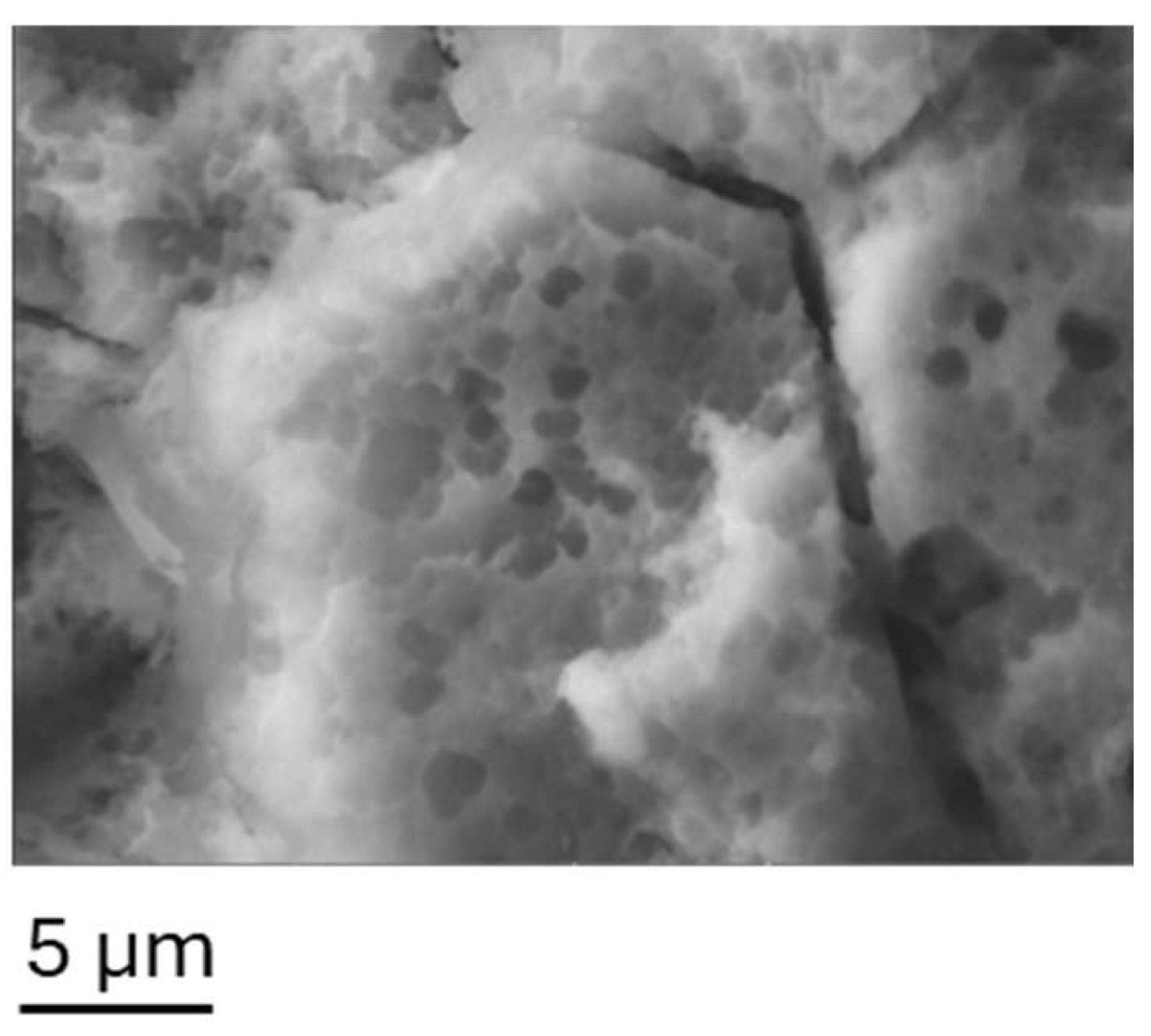

A porous, textured surface featuring honeycomb-like structures, many of which are sub-micrometric in size, is formed after prolonged exposure to HCl 3 M, as displayed in

Figure 2.

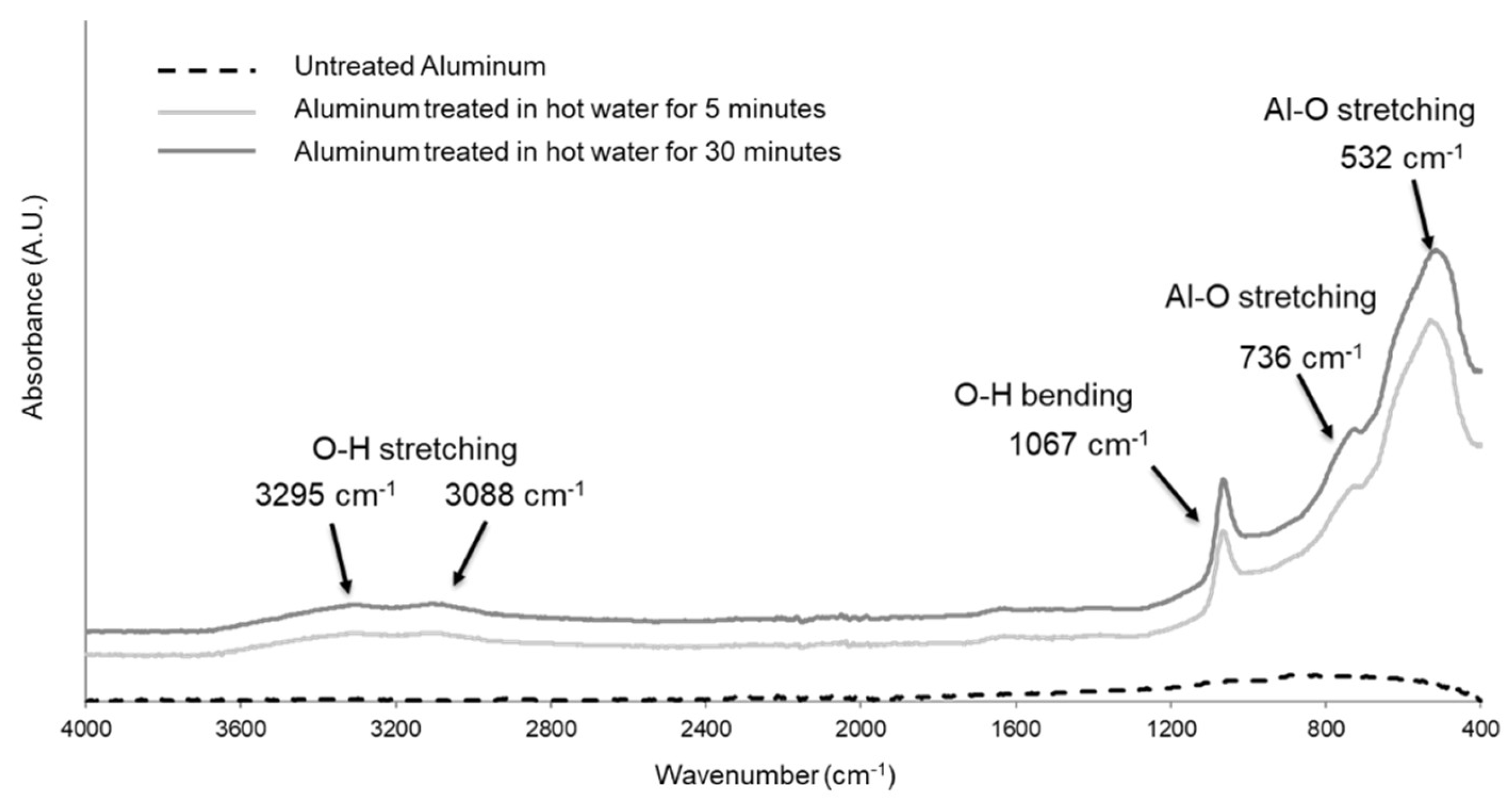

Nano-roughness formation, induced by the hydrothermal treatment of aluminum in boiling water, involves a chemical reaction giving rise to nanostructured oxide-hydroxide aluminum species (AlOOH-boehmite) with the release of hydrogen gas (H

2). All samples evidenced the typical signals due to the presence of AlOOH on the surface, as shown in the FTIR spectrum (

Figure 3 for samples LS5 and LS30).

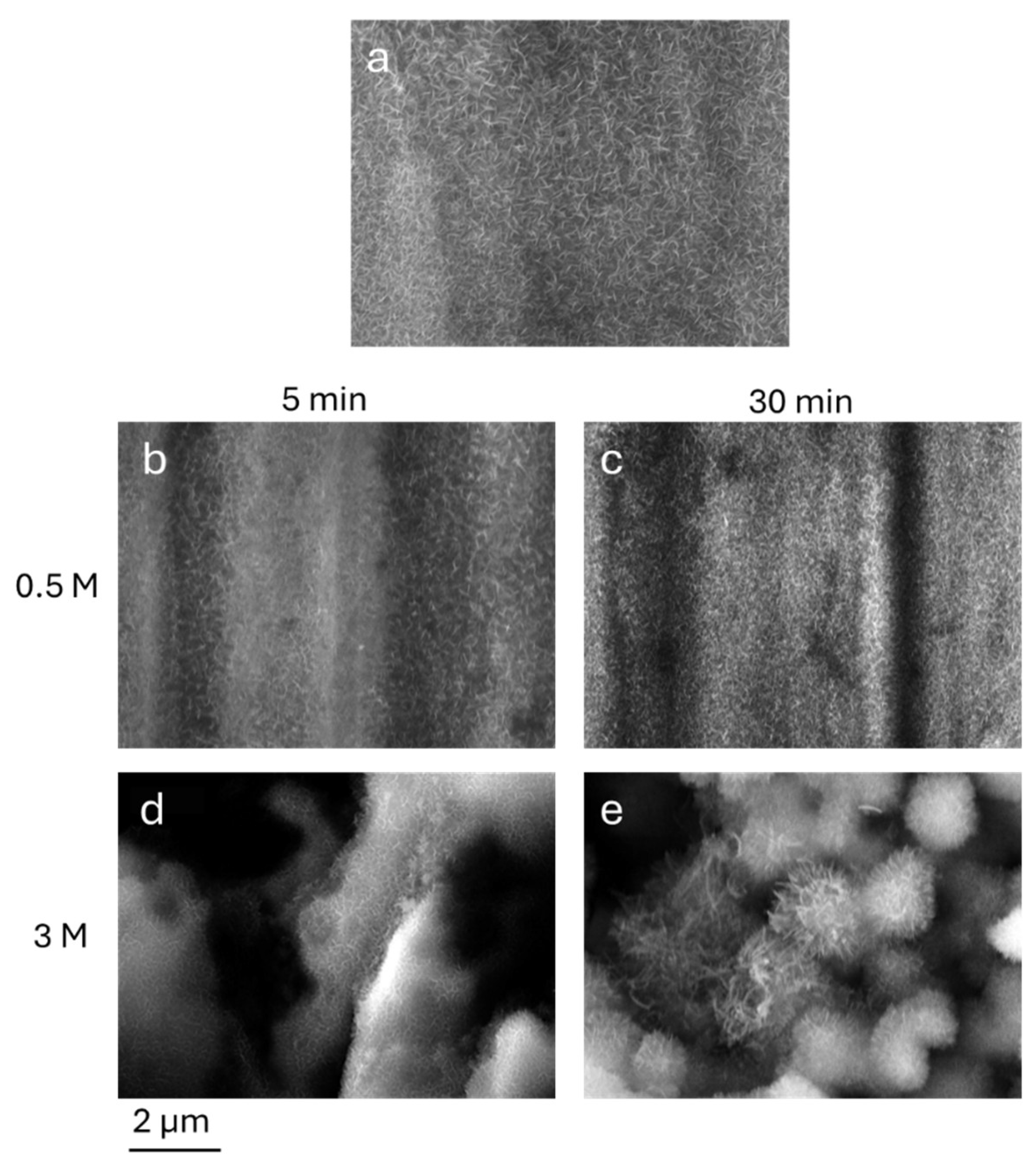

The nanostructures exhibit a needle-like shape with some differences linked to the duration of the process and to the underlying microroughness. In

Figure 4, the SEM images of the AlOOH on Nano-5 and on surfaces etched for 60 minutes in HCl 0.5 M and in HCl 3 M, growth for 5 and 30 minutes in hot water, (samples LL5, LL30, HL5 and HL30) are shown.

As shown, a 5-minute-long immersion time in boiling water is sufficient to induce the formation of acicular nanostructures on the surface. As expected [

19] by prolonging the treatment up to 30 minutes, the formation of denser structures, that ubiquitously covers the aluminium specimens, is evidenced.

For samples treated in HCl 3 M, the acicular nanostructures homogeneously cover the micro-rough surfaces giving rise to hierarchical aggregates. Moreover, the dimensions of AlOOH grown on sample HL30 are the biggest; this can be attributable both to the prolonged immersion time in water and the higher surface area obtained after the etching process.

3.2. Roughness

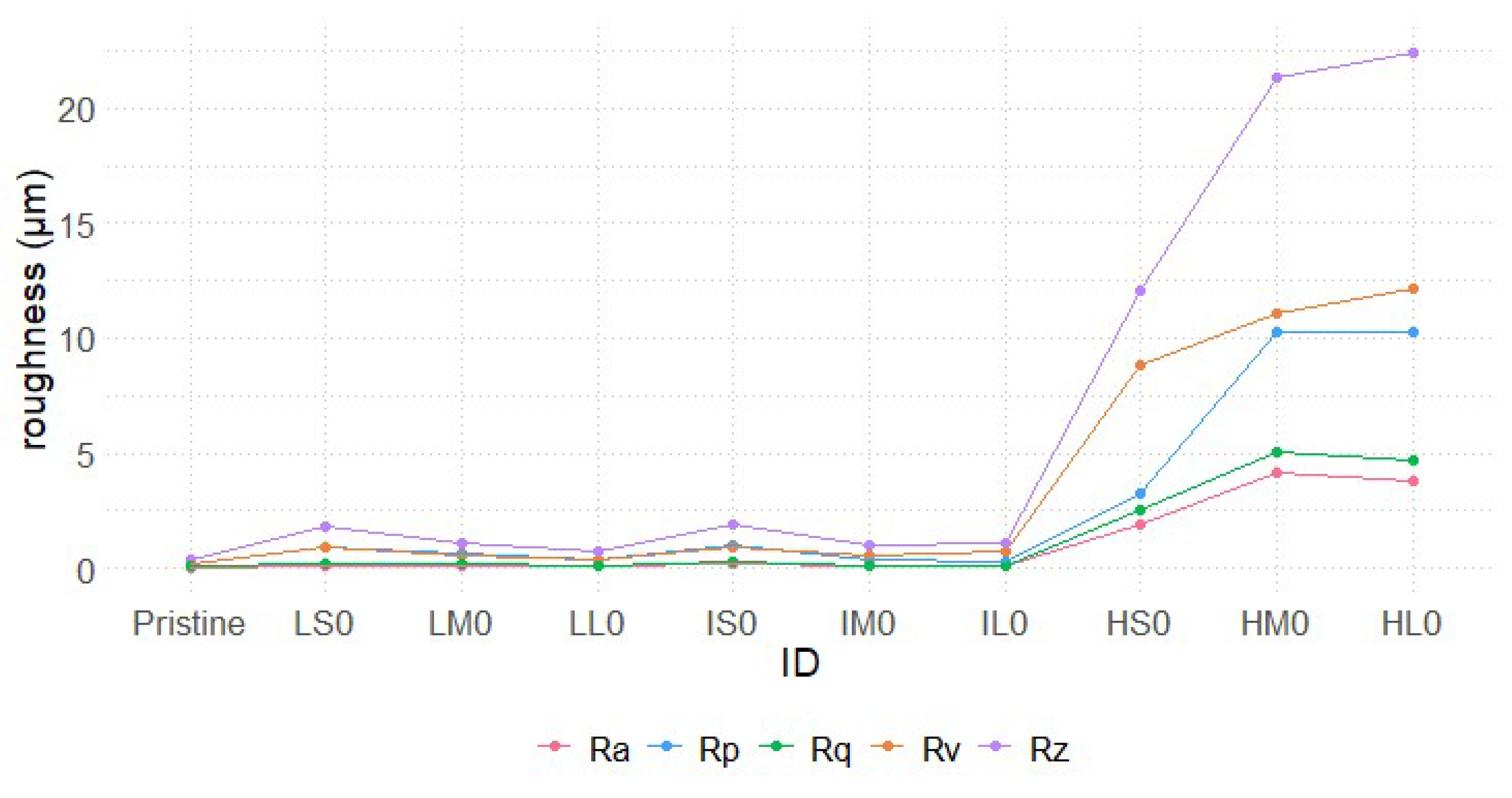

Micrometric-scale roughness was measured on the prepared samples and the results of roughness parameters, for Pristine and for samples that did not undergo hydrothermal treatment (xx0 series), are reported in

Figure 5. The dimensions of the resulting nanostructures were too small to be properly resolved with the employed profilometer and the micro-roughness of the nanostructured samples was found to be comparable to that of the corresponding untreated samples (see table S2 and figure S3 for full dataset).

All surfaces treated with 0.5 M and 1 M HCl (Lxx and Ixx series) have roughness parameters comparable to each other, exhibiting low values even if immersed for 60 minutes. In comparison with Pristine, these samples exhibit only a slight increase in roughness parameters although, as shown in

Figure 1, the SEM images reveal that in certain areas of these surfaces the etching treatment has altered the surface morphology.

Surfaces treated with 3 M HCl for 15 minutes (HS0), despite no significant increase in the average roughness (Ra), exhibit higher Rv values compared to Rp. This suggests that aluminum ablation under these etching conditions primarily deepens the valleys rather than increasing peak height.

Conversely, samples treated in HCl 3 M for at least 30 minutes show higher values across all roughness parameters as expected. Both peak height (Rp) and valley depths (Rv) reach up to 10 µm, while Rz increases up to 25 µm and Ra to 4 µm, indicating a uniformly roughened surface. It is worth noting that, in the case of treatment with 3 M HCl, surface roughness parameters increase sharply when the immersion time is extended from 15 to 30 minutes, while only a slight further increase is observed at 60 minutes.

3.2. Wettability of Etched Surfaces

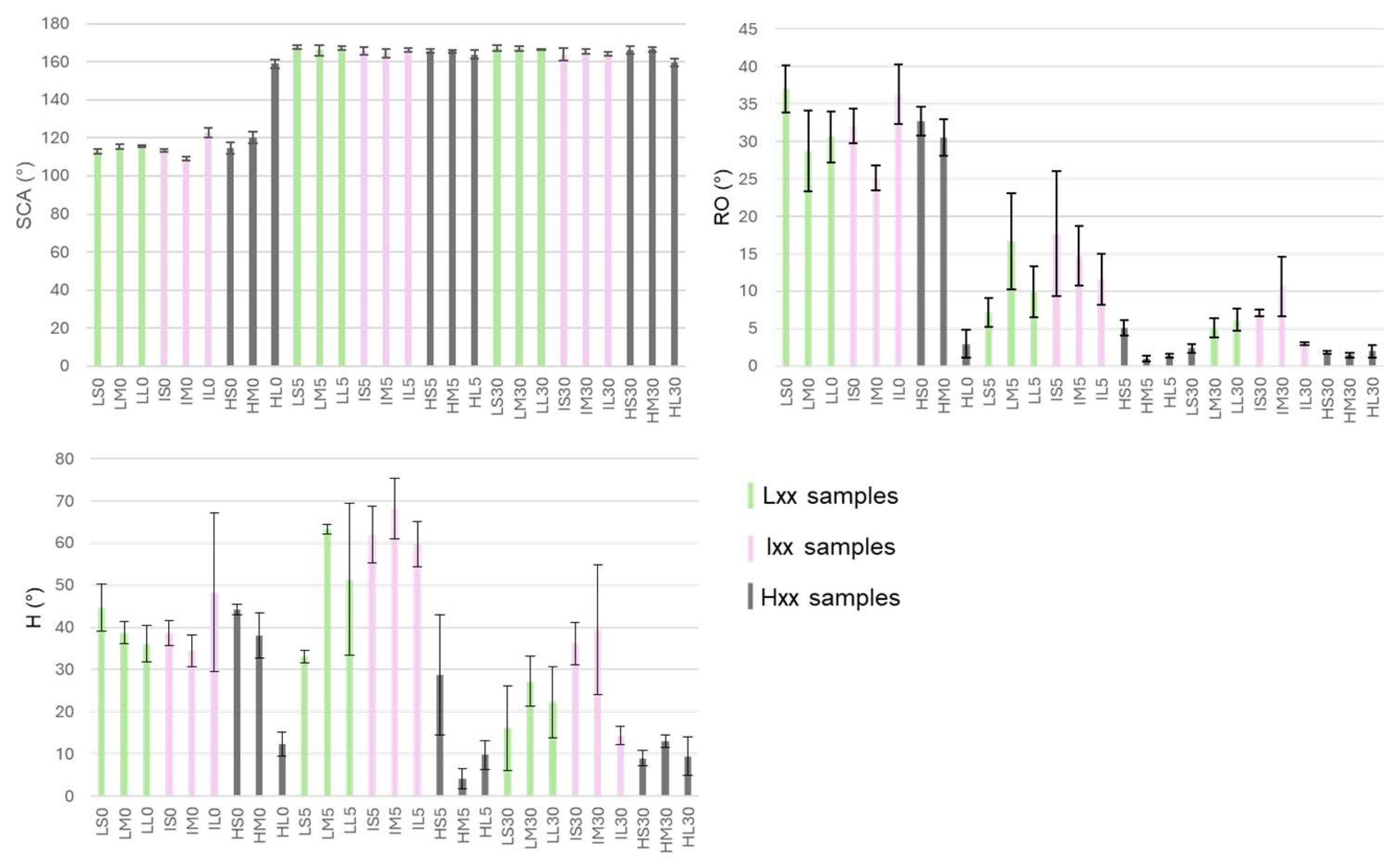

The results of wettability measurements on coated samples are reported in

Figure 6,

All the surfaces evidenced a pronounced hydrophobic behavior. The boiled samples exhibit a SCA of about 160°, meanwhile the un-boiled ones, with the exception to HL0, have a SCA ranging from 110° to 120°. The wettability of HL0 can be indeed compared to those of the boiled samples. Although the HL0 does not exhibit the AlOOH nanostructure, the peculiar honeycomb-like morphology formed after the prolonged treatment in strong acid, is sufficient to impart pronounced hydrophobic property (

Figure 2).

From roll-off angles data a trend can be evidenced: longer treatment in hot water leads to lower RO as the samples treated in boiling water for 30’ evidence very low RO, in some cases under 5°. By comparing the chemical etching, it is shown that samples etched with HCl 3 M (Hxx) generally evidence lower RO angles meanwhile the different immersion time in etching solution seems to be not relevant.

H results do not show a clear trend among samples with different hydrothermal treatment. It is possible to observe for instance that the 5’ treatment in boiling water gives rise to high H values, even higher than the samples that didn’t undergo the water treatment. The immersion time of 30’ leads to a decrease of hysteresis. Similarly to RO, the treatment in HCl 3 M gives rise to surfaces with low H values independently from the immersion time in the etching solution.

For many samples, especially among those with SCA higher than 160° hysteresis angles are very high even if roll-off angles are very low (see also figure S4). As stated above, mainly for practical reasons linked to the high water mobility on the SHP surfaces, the advancing and receding angles were measured, for all the surfaces, by increasing and decreasing the volume of the droplet. However, an increase in volume inherently corresponds to an increase in mass, and during this process, additional pressure is exerted on the droplet. As a result, the droplet may infiltrate the porous structure, leading to a transition from the Cassie-Baxter to the Wenzel state [

20], with consequent generally lower receding contact angles. At the same time, low receding angles are also clues of defects on the surface, and the very high dispersion of some H measures confirm this.

3.3. Icephobicity of Etched Surfaces

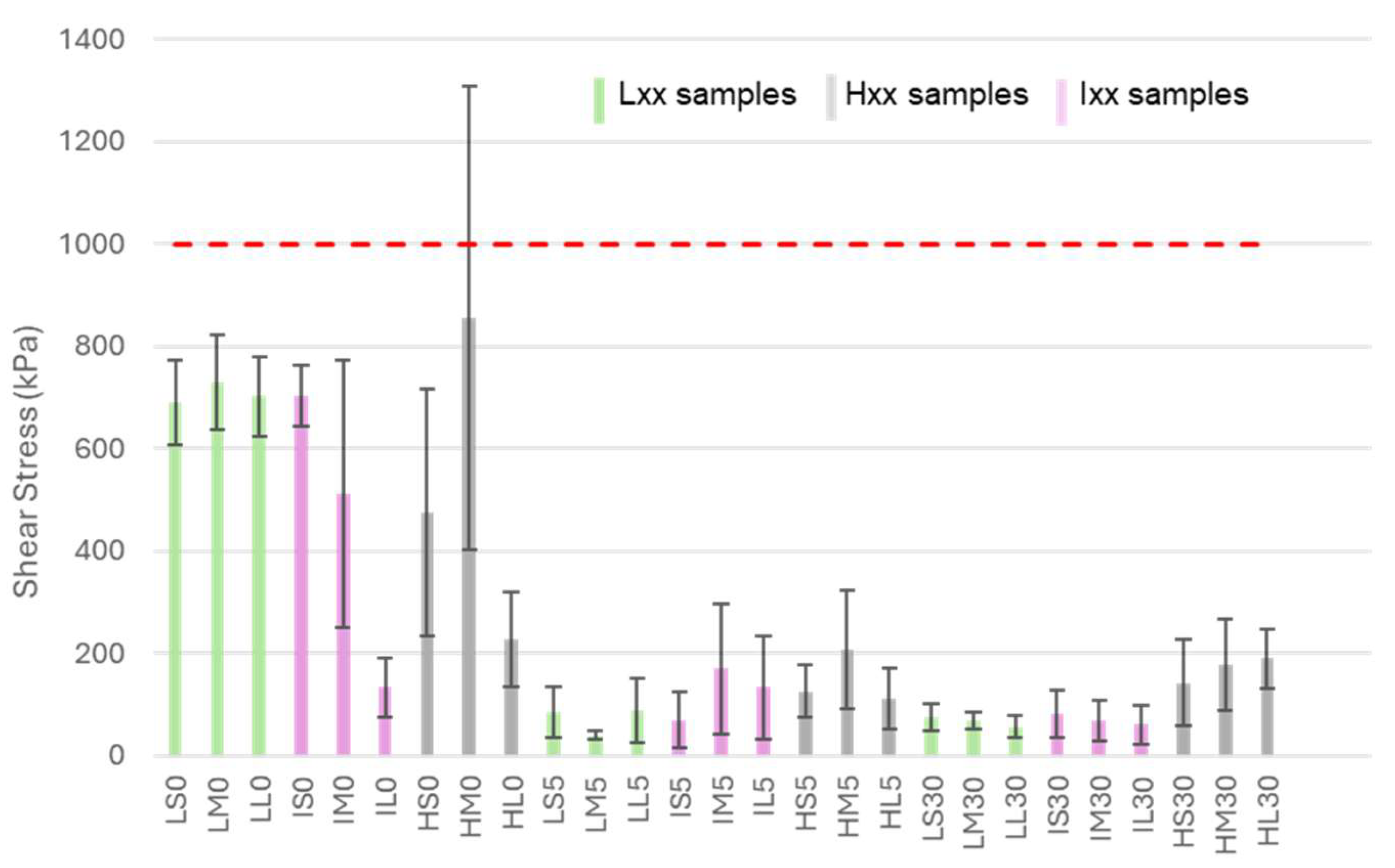

Ice adhesion results are reported in

Figure 7:

All samples decrease ice adhesion with respect to bare untreated aluminum on which an ice adhesion of about 1000 kPa in shear was measured. The calculated ARFs are listed in

Table 1, in which samples are grouped based on their values.

The shear stress data clearly indicate that hydrothermal treatment is the primary factor affecting icephobicity. All samples treated in boiling water exhibit highly or mildly icephobicity meanwhile all the un-boiled ones, with the exception to HL0 and IL0, showed poor anti-icing properties. This suggests that the presence of a nanometric structure is the key feature responsible for reducing ice adhesion.

In the case of HL0, the presence of a nanometric honeycomb-like structure not only reduces water adhesion, as previously discussed, but may also contribute to lowering ice adhesion by mimicking the AlOOH layer and forming a nano-structured surface. For IL0, since no nanostructures were observed on its surface, the low shear stress measured is somewhat unexpected, and further investigations will be necessary to clarify this behavior.

Although it is difficult to observe a clear trend related to the conditions applied, especially considering the high data dispersion of some samples, some correlation between the etching process and icephobicity can be identified. In particular, among nanostructured samples, surfaces treated with HCl 3 M (Hxx samples) generally exhibit higher ice adhesion than those treated with HCl 0.5 M (Lxx samples) or 1 M (Ixx samples). This is likely due to the increased microroughness, which leads to a larger surface area and consequently provides more sites where ice can mechanically interlock with the surface. It is also important to note that there is not a significative difference between samples Lxx and samples Ixx, which is consistent with the observed similarities in their morphology and surface roughness.

As already evidenced for wettability, the different etching time does not influence the icephobic performances.

3.4. Features for Icephobicity

The design of micro-nanostructured icephobic surfaces requires the combined consideration of roughness and morphology, and the resulting hydrophobicity can yield important indications on the expected ice adhesion

Icephobic performances among etched surfaces are thus achieved on substrates with minimal microroughness and acicular nanostructures. This is also confirmed by the surfaces Pristine and Nano-5, whose ice adhesion results are listed in

Table 2, together with their wettability results.

Once again, the presence of nanoroughness emerges as the key factor influencing ice adhesion, as the shear stress measured for Nano-5 is comparable to that of the best-performing etched surfaces. Conversely, the not boiled Pristine sample—despite being the smoothest among all—does not exhibit significant icephobicity.

Overall, data suggest that while a hierarchical micro-nano structure is necessary to achieve low water adhesion, a purely nanometric texture is sufficient to reduce ice adhesion. This morphology yields highly hydrophobic surfaces that facilitate the easy movement and detachment of water droplets, while minimal microroughness hinders ice anchoring.

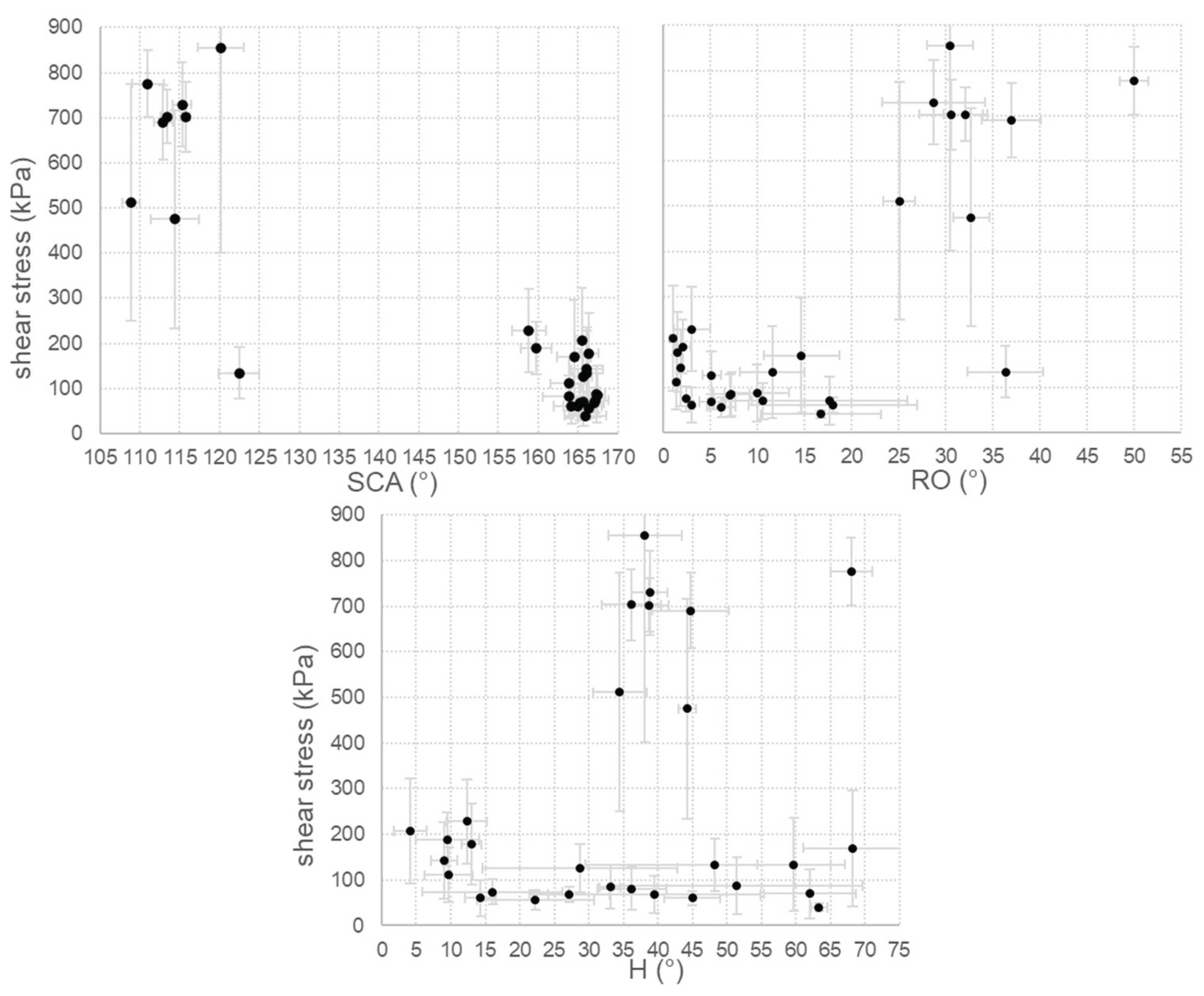

It is worth asking if a relationship can be found for these samples between hydrophobicity and icephobicity and if an effect in reducing ice adhesion can be inferred from wettability data. In

Figure 8 shear stress data are plotted against SCA, RO and H.

With only one exception (corresponding to sample IL0, discussed in chapter 3.3) high SCA (≃ 160°) and low RO (< 20°) values are consistently associated with low ice adhesion. In contrast to some findings reported in the literature [

21,

22], no clear correlation between H and ice adhesion can be established for our samples, as low ice adhesion is observed across a wide range of H values, from less than 5° to more than 65°.

Despite these correlations, it is important to highlight that SHP samples are not the best icephobic among the studied surfaces.

4. Conclusions

Starting from aluminum plates and bars, several hydrophobic and superhydrophobic samples were prepared and their icephobicity was studied. The synthesis was carried out with a very simple process that includes chemical etching, immersion in hot water and coating with a fluorinated molecule. Changing the concentration of the etchant and the treatment time allows the tuning of surface roughness and, consequently, both the hydrophobic and icephobic properties.

All samples exhibited hydrophobic behavior, and the wettability results indicate that the nanometric roughness generated by hydrothermal treatment plays a key role in increasing SCA and reducing RO values. Superhydrophobicity is achieved in samples subjected to harsher etching conditions, which produce the highest levels of micro-roughness.

All samples were found to reduce ice adhesion compared to the uncoated aluminum alloy, although the extent of reduction varies significantly among them. Analogously to wettability, the presence of the nanometric layer is the key factor in lowering ice adhesion. The etching treatment has a less pronounced effect on icephobicity; however, excessive micro-roughness can lead to a certain increase in ice adhesion, likely due to mechanical interlocking between the ice and surface asperities. Thus, superhydrophobic surfaces are not the best icephobic, due to an excessive microroughness that causes the anchoring of the ice to the surface. However, all the superhydrophobic samples displayed a mild icephobicity reaching ARF values of about 5.

The best icephobic sample is LM5, treated in HCl 0.5 M for 30 minutes and then treated in hot water for 5 minutes. Notably, Nano-5, obtained by only a simple immersion in hot water also demonstrated significant icephobicity, with an ARF value of about 17.

The relationship between ice adhesion and wettability shows that surfaces with ARF higher than 10, are characterized by SCA > 150° and RO angle < 20°meanwhile contact angle hysteresis was found to be substantially unrelated. However, these wettability properties constitute a necessary but not sufficient condition to achieve high icephobicity, as several samples exhibiting such features, display ARF value between 9 and 4. Since wettability is in turn governed by morphology and roughness, both must be carefully engineered to ensure high SCA angle and low RO angle while simultaneously avoiding excessive surface asperities.

A fabrication process involving short chemical etching in diluted HCl instead of harsher and prolonged treatment in more concentrated acid, is thus preferable to achieve icephobicity.

This study demonstrates that a balanced surface design is essential for the highest icephobic performances and some key features to obtain them are proposed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.; methodology, M.B.; formal analysis, G.S. and A.C.; investigation, G.S. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, G.S., F.P. and A.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

RSE contribution to this work has been financed by the Research Fund for the Italian Electrical System under the Three-Year Research Plan 2025-2027 (MASE, Decree n.388 of November 6th, 2024), in compliance with the Decree of April 12th, 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SHP |

Superhydrophobic |

| FAS |

Fluoroalkylsilane |

| SCA |

Static contact angle |

| H |

Hysteresis |

| RO |

Roll-off |

| ARF |

Adhesion reduction factor |

References

- J. Jeevahan, M. Chandrasekaran, G. Britto Joseph, R. B. Durairaj, e G. Mageshwaran, «Superhydrophobic surfaces: a review on fundamentals, applications, and challenges», J Coat Technol Res, vol. 15, fasc. 2, pp. 231–250, mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumar e A. Kumar Sahani, «Role of superhydrophobic coatings in biomedical applications», Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 45, pp. 5655–5659, gen. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Li et al., «A Review on Superhydrophobic Surface with Anti-Icing Properties in Overhead Transmission Lines», Coatings, vol. 13, fasc. 2, p. 301, feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Piscitelli, A. Chiariello, D. Dabkowski, G. Corraro, F. Marra, e L. Di Palma, «Superhydrophobic Coatings as Anti-Icing Systems for Small Aircraft», Aerospace, vol. 7, fasc. 1, p. 2, gen. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Artesani, F. Di Turo, M. Zucchelli, e A. Traviglia, «Recent Advances in Protective Coatings for Cultural Heritage–An Overview», Coatings, vol. 10, fasc. 3, p. 217, mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Arabzadeh, H. Ceylan, S. Kim, K. Gopalakrishnan, e A. Sassani, «Superhydrophobic Coatings on Asphalt Concrete Surfaces: Toward Smart Solutions for Winter Pavement Maintenance», Transportation Research Record, vol. 2551, fasc. 1, pp. 10–17, gen. 2016. [CrossRef]

- V. Tangwarodomnukun, S. Kringram, H. Zhu, H. Qi, e N. Rujisamphan, «Fabrication of superhydrophobic surface on AISI316L stainless steel using a nanosecond pulse laser», Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture, vol. 236, fasc. 6–7, pp. 680–693, mag. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pozzato et al., «Superhydrophobic surfaces fabricated by nanoimprint lithography», Microelectronic Engineering, vol. 83, fasc. 4, pp. 884–888, apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- M. Balordi, A. Cammi, G. Santucci de Magistris, e C. Chemelli, «Role of micrometric roughness on anti-ice properties and durability of hierarchical super-hydrophobic aluminum surfaces», Surface and Coatings Technology, vol. 374, pp. 549–556, set. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Balordi, F. Pini, e G. Santucci de Magistris, «Superhydrophobic ice-phobic zinc surfaces», Surfaces and Interfaces, vol. 30, p. 101855, giu. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, Z. Zhang, J. Yang, Y. Yue, e H. Zhang, «Fabrication of superhydrophobic surface on stainless steel by two-step chemical etching», Chemical Physics Letters, vol. 797, p. 139567, giu. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, Y. Zhan, e S. Yu, «Applications of superhydrophobic coatings in anti-icing: Theory, mechanisms, impact factors, challenges and perspectives», Progress in Organic Coatings, vol. 152, p. 106117, mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Chu, Z. Hu, Y. Feng, N.-C. Lai, X. Wu, e R. Wang, «Advanced Anti-Icing Strategies and Technologies by Macrostructured Photothermal Storage Superhydrophobic Surfaces», Advanced Materials, vol. 36, fasc. 31, p. 2402897, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Li et al., «A Review on Superhydrophobic Surface with Anti-Icing Properties in Overhead Transmission Lines», Coatings, vol. 13, fasc. 2, p. 301, feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., «Superhydrophobic surfaces cannot reduce ice adhesion», Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 101, fasc. 11, p. 111603, set. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Varanasi, T. Deng, J. D. Smith, M. Hsu, e N. Bhate, «Frost formation and ice adhesion on superhydrophobic surfaces», Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 97, fasc. 23, p. 234102, dic. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Jung, M. Dorrestijn, D. Raps, A. Das, C. M. Megaridis, e D. Poulikakos, «Are Superhydrophobic Surfaces Best for Icephobicity?», Langmuir, vol. 27, fasc. 6, pp. 3059–3066, mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Mihaela, «STUDY ABOUT ALUMINIUM ETCHING».

- N. Rider, «The influence of porosity and morphology of hydrated oxide films on epoxy-aluminium bond durability», Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, vol. 15, fasc. 4, pp. 395–422, gen. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H. Jinnai, e A. Takahara, «Wetting Transition from the Cassie–Baxter State to the Wenzel State on Textured Polymer Surfaces», Langmuir, vol. 30, fasc. 8, pp. 2061–2067, mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Nosonovsky e V. Hejazi, «Why Superhydrophobic Surfaces Are Not Always Icephobic», ACS Nano, vol. 6, fasc. 10, pp. 8488–8491, ott. 2012. [CrossRef]

- «From superhydrophobicity to icephobicity: forces and interaction analysis | Scientific Reports». Consultato: 27 agosto 2025. [Online]. Disponibile su: https://www.nature.com/articles/srep02194.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).