Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Participants’ Characteristics

2.2. Identification of SH Metabolites

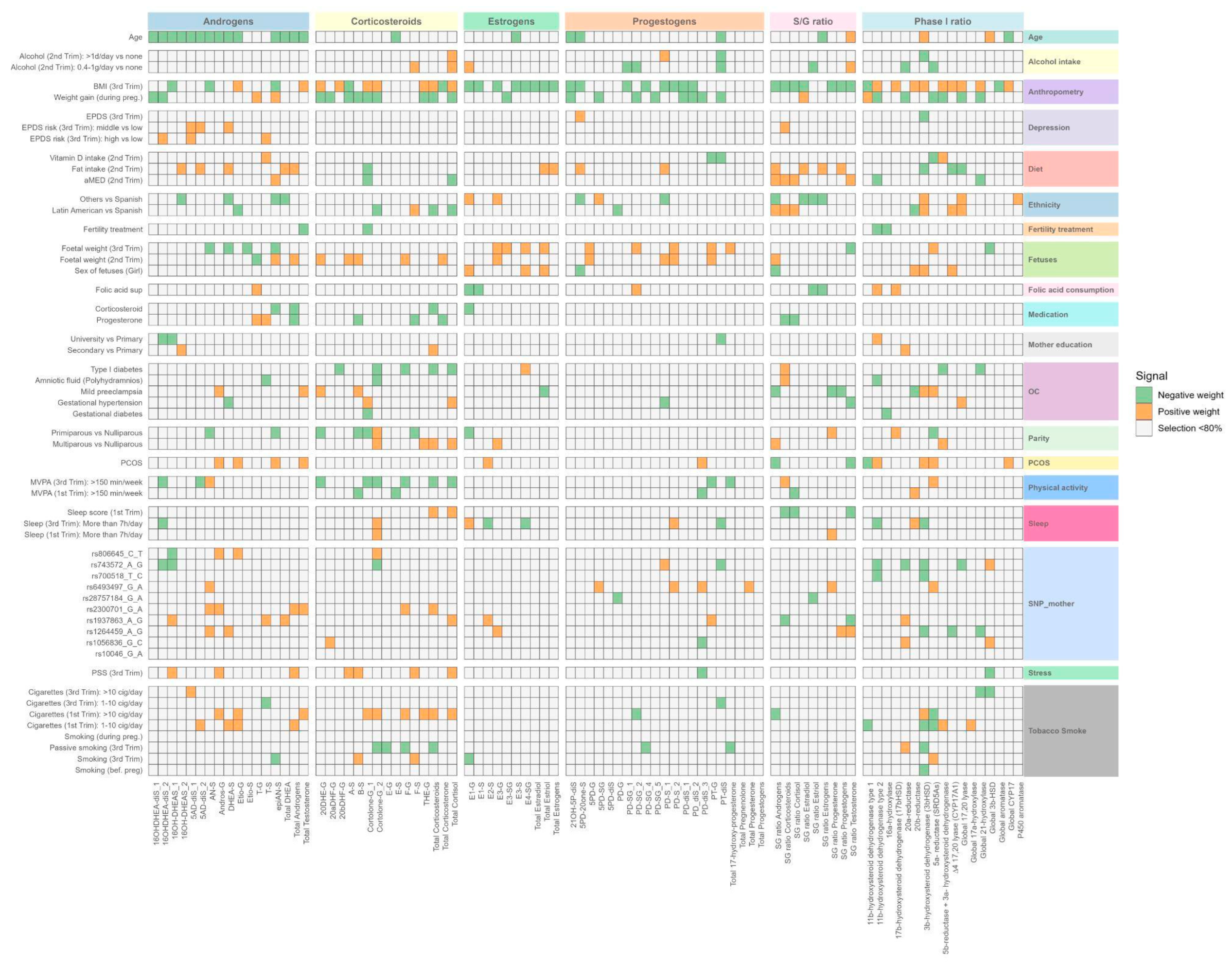

2.3. Main Determinant Selection of the SH Metabolome (BiSC Cohort): ExWAS and ENET Analyses

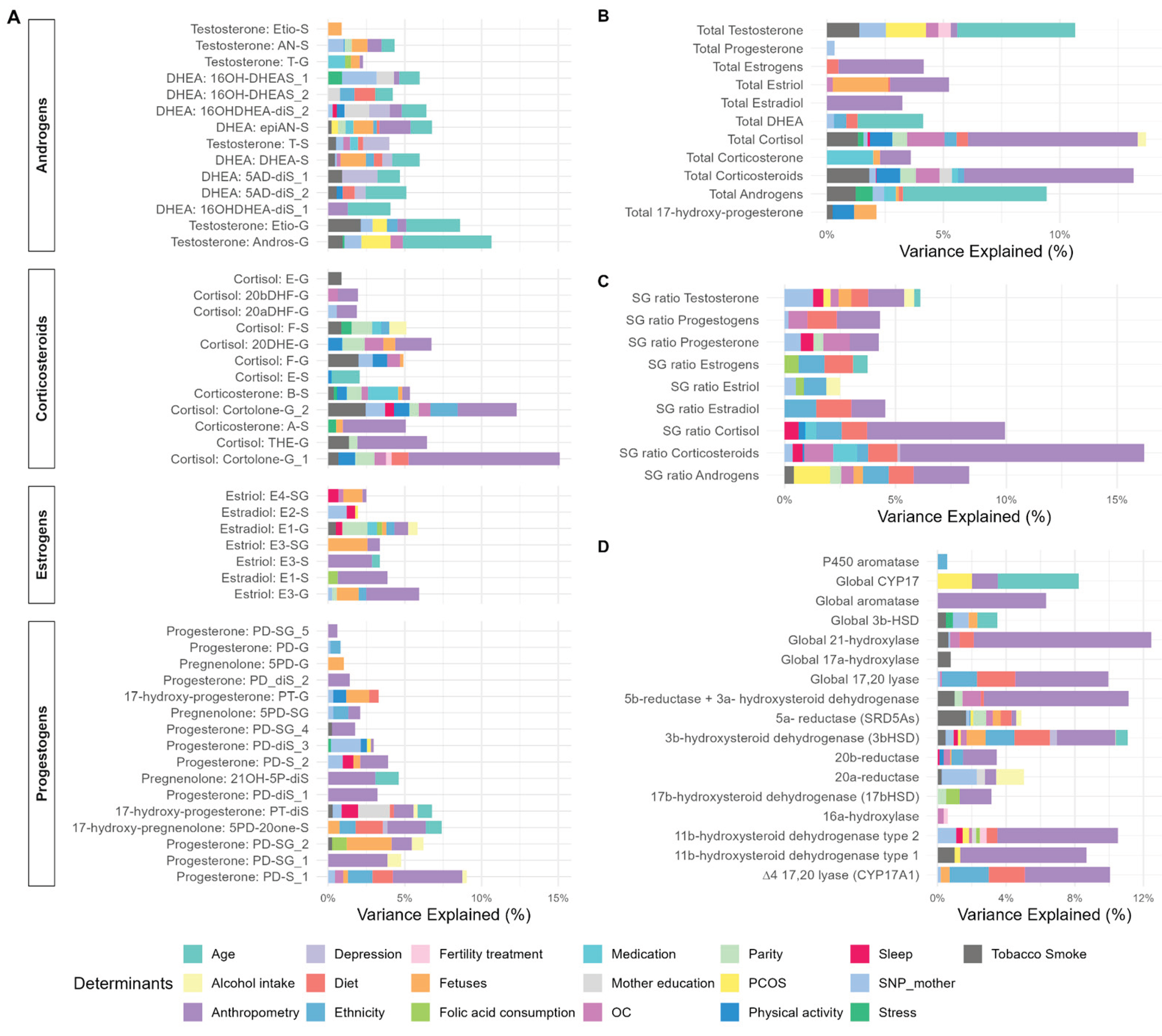

2.5. Steroid Hormone Level Variations Are Explained by Physiological Variables, and Lifestyle: Relative Importance Analysis (BiSC Cohort)

2.6. External Replication Analysis (INMA-Sabadell Cohort)

3. Discussion

3.1. A New Window into Maternal Steroid Metabolism

3.2. Clinical Factors Are Consistently Associated with SH-Level Differences

3.3. Lifestyle Behaviours: Physical Activity, Sleep, Smoking, Alcohol, and Diet Are Determinants of SH Levels

3.4. Maternal Age and Ethnicity as Sociodemography Determinants Associated with SH Metabolism

3.5. Genetic: SNPs from Steroidogenesis Enzymes

3.6. Fetal Determinants: Sex

3.7. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Participants and Study Overview

4.2. Urine Collection and Steroid Targeted Metabolome Profiling

4.5. Determinants

- i.

- Sociodemographic and clinical parameters

- ii.

- Fetal growth

- iii.

- Genetic

- iv.

- Mental health

- v.

- Lifestyle

4.6. Statistical Analysis

4.6.1. Data Preparation

4.6.2. ExWAS Analysis

4.6.3. Elastic Net Regression Analysis to Determinant Selection

4.6.4. Linear Regression Model and Variance Explained Estimation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A-S | 11-dehydrocorticosterone-Sulfate |

| AN-S | Androsterone-Sulfate |

| Andros-G | Androsterone-Glucuronide |

| B-S | Corticosterone-Sulfate |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| Cortolone-G_1 | 20a-Cortolone-Glucuronide |

| Cortolone-G_2 | 20b-Cortolone-Glucuronide |

| DHEA | Dehydroepiandrosterone |

| DHEA-S | DHEA-sulfate |

| E-S | Cortisone-Sulfate |

| E-G | Cortisone-Glucuronide |

| E2-S | Estradiol-Sulfate |

| E1-G | Estrone-Glucuronide |

| E1-S | Estrone-Sulfate |

| E3-G | Estriol-Glucuronide |

| E3-SG | Estriol-Sulfoglucoconjugated |

| E3-S | Estriol-Sulfate |

| E4-SG | Estetrol-Sulfoglucoconjugated |

| ExWAS | Exposome-Wide Analysis |

| ENT | Effective Number of Tests |

| ENET | Elastic Net regression |

| epiAN-S | epiandrosterone-Sulfate |

| Etio-S | Etiocholanolone-Sulfate |

| Etio-G | Etiocholanolone-Glucuronide |

| F-S | Cortisol-Sulfate |

| F-G | Cortisol-Glucuronide |

| FFQ | Food Frequency Questionnaire |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| MEDAS | Mediterranean Diet Adherence Score |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity |

| OC | Obstetric Complications |

| PCs | Principal components |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| rMED | relative Mediterranean Diet score |

| S/G | Sulfate/Glucuronide |

| SNPs | Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| SSH | Sex steroid hormones |

| 5AD-diS_1 | 5-androsten-3b17b-diol-diSulfate |

| 5AD-diS_2 | 5-androsten-3a17b-diol-diSulfate |

| 16OHDHEA-diS_1 | 16b-hydroxy-DHEA-diSulfate |

| 16OHDHEA-diS_2 | 16a-hydroxy-DHEA-diSulfate |

| 16OH-DHEAS_1 | 16b-hydroxy-DHEA-Sulfate |

| 16OH-DHEAS_2 | 16a-hydroxy-DHEA-Sulfate |

| T-G | Testosterone-Glucuronide |

| T-S | Testosterone-Sulfate |

| 20DHE-G | 20dihydrocortisone-Glucuronide |

| 20aDHF-G | 20a-dihydrocortisol-Glucuronide |

| 20bDHF-G | 20b-dihydrocortisol-Glucuronide |

| THE-G | Tetrahydrocortisone-Glucuronide |

| 5PD-20one-S | 17-hydroxy-5-pregnenolone-3-sulfate |

| 5PD-diS | 5-Pregnendiol-DiSulfate |

| 21OH-5P-diS | 21-Hydroxypregnenolone-DiSulfate |

| 5PD-SG | 5-Pregnendiol-Sulfoglucoconjugated |

| 5PD-G | 5-Pregnendiol-Glucuronide |

| PD-diS_1 | 5a-Pregnan-3b,20a-diol-DiSulfate |

| PD_diS_2 | 5a-Pregnan-3a,20a-diol-DiSulfate |

| PD-diS_3 | 5b-Pregnan-3a,20a-diol-DiSulfate |

| PD-SG_1 | 5a-Pregnandiol-3b-sulfate-20a-Glucuronide |

| PD-SG_2 | Pregnandiol-sulfoglucoconjugate (unknown stereochemistry) |

| PD-SG_4 | Pregnandiol-sulfoglucoconjugate (unknown stereochemistry) |

| PD-SG_5 | Pregnandiol-sulfoglucoconjugate (unknown stereochemistry) |

| PD-S_1 | 5a-Pregnan-3b20a-diol-20-Sulfate |

| PD-S_2 | 5b-Pregnan-3a20a-diol-20-Sulfate |

| PD-G | Pregnandiol-Glucuronide |

| PT-diS | Pregnantriol-diSulfate |

| PT-G | Pregnantriol-Glucuronide |

References

- Chatuphonprasert, W.; Jarukamjorn, K.; Ellinger, I. Physiology and Pathophysiology of Steroid Biosynthesis, Transport and Metabolism in the Human Placenta. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1027. [CrossRef]

- Christakoudi, S.; Cowan, D.A.; Christakudis, G.; Taylor, N.F. 21-Hydroxylase deficiency in the neonate – trends in steroid anabolism and catabolism during the first weeks of life. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 138, 334–347. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.L. Steroid hormone synthesis in mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 379, 62–73. [CrossRef]

- Miller WL. Steroidogenesis: Unanswered Questions. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Nov 1;28(11):771–93. [CrossRef]

- Miller WL, Bose HS. Early steps in steroidogenesis: intracellular cholesterol trafficking: Thematic Review Series: Genetics of Human Lipid Diseases. J Lipid Res. 2011 Dec 1;52(12):2111–35. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.L.; Auchus, R.J. The Molecular Biology, Biochemistry, and Physiology of Human Steroidogenesis and Its Disorders. Endocr. Rev. 2011, 32, 81–151. [CrossRef]

- Pozo, O.J.; Marcos, J.; Khymenets, O.; Pranata, A.; Fitzgerald, C.C.; McLeod, M.D.; Shackleton, C. SULFATION PATHWAYS: Alternate steroid sulfation pathways targeted by LC–MS/MS analysis of disulfates: application to prenatal diagnosis of steroid synthesis disorders. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 61, M1–M12. [CrossRef]

- Fabregat, A.; Marcos, J.; Garrostas, L.; Segura, J.; Pozo, O.J.; Ventura, R. Evaluation of urinary excretion of androgens conjugated to cysteine in human pregnancy by mass spectrometry. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 139, 192–200. [CrossRef]

- Servin-Barthet, C.; Martínez-García, M.; Paternina-Die, M.; Marcos-Vidal, L.; de Blas, D.M.; Soler, A.; Khymenets, O.; Bergé, D.; Casals, G.; Prats, P.; et al. Pregnancy entails a U-shaped trajectory in human brain structure linked to hormones and maternal attachment. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.S.; Mbowe, O.; Thurston, S.W.; Butts, S.; Wang, C.; Nguyen, R.; Bush, N.; Redmon, J.B.; Sheshu, S.; Swan, S.H.; et al. Predictors of Steroid Hormone Concentrations in Early Pregnancy: Results from a Multi-Center Cohort. Matern. Child Heal. J. 2019, 23, 397–407. [CrossRef]

- Bíró, I.; Bufa, A.; Wilhelm, F.; Mánfai, Z.; Kilár, F.; Gocze, P.M. Urinary steroid profile in early pregnancy after in vitro fertilization. Acta Obstet. et Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 625–629. [CrossRef]

- Kallak, T.K.; Hellgren, C.; Skalkidou, A.; Sandelin-Francke, L.; Ubhayasekhera, K.; Bergquist, J.; Axelsson, O.; Comasco, E.; E Campbell, R.; Poromaa, I.S. Maternal and female fetal testosterone levels are associated with maternal age and gestational weight gain. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 177, 379–388. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S.K.; O’bUckley, T.K.; Schiller, C.E.; Stuebe, A.; Morrow, A.L.; Girdler, S.S. Blunted neuroactive steroid and HPA axis responses to stress are associated with reduced sleep quality and negative affect in pregnancy: a pilot study. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 1299–1310. [CrossRef]

- Deltourbe, L.G.; Sugrue, J.; Maloney, E.; Dubois, F.; Jaquaniello, A.; Bergstedt, J.; Patin, E.; Quintana-Murci, L.; Ingersoll, M.A.; Duffy, D.; et al. Steroid hormone levels vary with sex, aging, lifestyle, and genetics. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadu6094. [CrossRef]

- Lobmaier, S.M.; Figueras, F.; Mercade, I.; Crovetto, F.; Peguero, A.; Parra-Saavedra, M.; Ortiz, J.U.; Crispi, F.; Gratacós, E. Levels of Maternal Serum Angiogenic Factors in Third-Trimester Normal Pregnancies: Reference Ranges, Influence of Maternal and Pregnancy Factors and Fetoplacental Doppler Indices. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2014, 36, 38–43. [CrossRef]

- Karvaly, G.; Kovács, K.; Gyarmatig, M.; Gerszi, D.; Nagy, S.; Jalal, D.A.; Tóth, Z.; Vasarhelyi, B.; Gyarmati, B. Reference data on estrogen metabolome in healthy pregnancy. Mol. Cell. Probes 2024, 74, 101953. [CrossRef]

- Jäntti, S.E.; Hartonen, M.; Hilvo, M.; Nygren, H.; Hyötyläinen, T.; Ketola, R.A.; Kostiainen, R. Steroid and steroid glucuronide profiles in urine during pregnancy determined by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 802, 56–66. [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Peng, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhu, Q.; Lin, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, P. Dynamic change of estrogen and progesterone metabolites in human urine during pregnancy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Mistry, H.D.; Eisele, N.; Escher, G.; Dick, B.; Surbek, D.; Delles, C.; Currie, G.; Schlembach, D.; Mohaupt, M.G.; Gennari-Moser, C. Gestation-specific reference intervals for comprehensive spot urinary steroid hormone metabolite analysis in normal singleton pregnancy and 6 weeks postpartum. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015, 13, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Shen, Y.; Li, W.; Wei, Z.; Li, S.; Lin, Q.; Chang, Y. Expression of Key Steroidogenic Enzymes in Human Placenta and Associated Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Matern. Med. 2022, 5, 163–172. [CrossRef]

- Pasqualini JR. Enzymes involved in the formation and transformation of steroid hormones in the fetal and placental compartments. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005 Dec 1;97(5):401–15.

- Maliqueo, M.; Cruz, G.; Espina, C.; Contreras, I.; García, M.; Echiburú, B.; Crisosto, N. Obesity during pregnancy affects sex steroid concentrations depending on fetal gender. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1636–1645. [CrossRef]

- Volqvartz T, Andersen HHB, Pedersen LH, Larsen A. Obesity in pregnancy—Long-term effects on offspring hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and associations with placental cortisol metabolism: A systematic review. Eur J Neurosci. 2023;58(11):4393–422. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, S.L.; Mitchell, A.M.; Kowalsky, J.M.; Christian, L.M. Maternal parity and perinatal cortisol adaptation: The role of pregnancy-specific distress and implications for postpartum mood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 97, 86–93. [CrossRef]

- Marteinsdottir, I.; Sydsjö, G.; Faresjö, Å.; Theodorsson, E.; Josefsson, A. Parity-related variation in cortisol concentrations in hair during pregnancy. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 128, 637–644. [CrossRef]

- Budnik-Przybylska, D.; Laskowski, R.; Pawlicka, P.; Anikiej-Wiczenbach, P.; Łada-Maśko, A.; Szumilewicz, A.; Makurat, F.; Przybylski, J.; Soya, H.; Kaźmierczak, M. Do Physical Activity and Personality Matter for Hair Cortisol Concentration and Self-Reported Stress in Pregnancy? A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 8050. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, J.G.; Taha, S.; Torres-Sánchez, L.E.; Villasante-Tezanos, A.; Milani, S.A.; Baillargeon, J.; Canfield, S.; Lopez, D.S. Association of sleep duration and quality with serum testosterone concentrations among men and women: NHANES 2011–2016. Andrology 2023, 12, 518–526. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, W.D.; Seng, J.S. Posttraumatic stress disorder, smoking, and cortisol in a community sample of pregnant women. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1408–1413. [CrossRef]

- Varvarigou, A.A.; Petsali, M.; Vassilakos, P.; Beratis, N.G. Increased cortisol concentrations in the cord blood of newborns whose mothers smoked during pregnancy. jpme 2006, 34, 466–70. [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, S.; Manning, J.; Brabin, B. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and possible effects of in utero testosterone: Evidence from the 2D:4D finger length ratio. Early Hum. Dev. 2007, 83, 87–90. [CrossRef]

- Cajachagua-Torres, K.N.; Jaddoe, V.W.; de Rijke, Y.B.; Akker, E.L.v.D.; Reiss, I.K.; van Rossum, E.F.; El Marroun, H. Parental cannabis and tobacco use during pregnancy and childhood hair cortisol concentrations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 225, 108751. [CrossRef]

- Halmesmäki, E.; Autti, I.; Granström, M.-L.; Stenman, U.-H.; Ylikorkala, O. Estradiol, Estriol, Progesterone, Prolactin, and Human Chorionic Gonadotropin in Pregnant Women with Alcohol Abuse*. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1987, 64, 153–156. [CrossRef]

- Lof M, Hilakivi-Clarke L, Sandin S S, de Assis S, Yu W, Weiderpass E. Dietary fat intake and gestational weight gain in relation to estradiol and progesterone plasma levels during pregnancy: a longitudinal study in Swedish women. BMC Womens Health. 2009 Apr 30;9(1):10. [CrossRef]

- Chonnak, U.; Pongsatha, S.; Luewan, S.; Sirilert, S.; Tongsong, T. Pregnancy outcomes among women near the end of reproductive age. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025, 25, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Glynn, L.M.; Schetter, C.D.; Chicz-DeMet, A.; Hobel, C.J.; Sandman, C.A. Ethnic differences in adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol and corticotropin-releasing hormone during pregnancy. Peptides 2007, 28, 1155–1161. [CrossRef]

- Thayer, Z.M.; Kuzawa, C.W. Ethnic discrimination predicts poor self-rated health and cortisol in pregnancy: Insights from New Zealand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 128, 36–42. [CrossRef]

- Urizar, G.G.; Yim, I.S.; Kofman, Y.B.; Tilka, N.; Miller, K.; Freche, R.; Johnson, A. Ethnic differences in stress-induced cortisol responses:Increased risk for depression during pregnancy. Biol. Psychol. 2019, 147, 107630. [CrossRef]

- Maitre, L.; Villanueva, C.M.; Lewis, M.R.; Ibarluzea, J.; Santa-Marina, L.; Vrijheid, M.; Sunyer, J.; Coen, M.; Toledano, M.B. Maternal urinary metabolic signatures of fetal growth and associated clinical and environmental factors in the INMA study. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Maitre, L.; Jedynak, P.; Gallego, M.; Ciaran, L.; Audouze, K.; Casas, M.; Vrijheid, M. Integrating -omics approaches into population-based studies of endocrine disrupting chemicals: A scoping review. Environ. Res. 2023, 228, 115788. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Núñez, Z.; Hansel, M.; Capurro, C.; Kozlosky, D.; Wang, C.; Doherty, C.L.; Buckley, B.; Ohman-Strickland, P.; Miller, R.K.; O’connor, T.G.; et al. Prenatal Cadmium Exposure and Maternal Sex Steroid Hormone Concentrations across Pregnancy. Toxics 2023, 11, 589. [CrossRef]

- Kolatorova, L.; Vitku, J.; Hampl, R.; Adamcova, K.; Skodova, T.; Simkova, M.; Parizek, A.; Starka, L.; Duskova, M. Exposure to bisphenols and parabens during pregnancy and relations to steroid changes. Environ. Res. 2018, 163, 115–122. [CrossRef]

- Ryva, B.A.; Pacyga, D.C.; Anderson, K.Y.; Calafat, A.M.; Whalen, J.; Aung, M.T.; Gardiner, J.C.; Braun, J.M.; Schantz, S.L.; Strakovsky, R.S. Associations of urinary non-persistent endocrine disrupting chemical biomarkers with early-to-mid pregnancy plasma sex-steroid and thyroid hormones. Environ. Int. 2024, 183, 108433–108433. [CrossRef]

- Pacyga, D.C.; Gardiner, J.C.; Flaws, J.A.; Li, Z.; Calafat, A.M.; Korrick, S.A.; Schantz, S.L.; Strakovsky, R.S. Maternal phthalate and phthalate alternative metabolites and urinary biomarkers of estrogens and testosterones across pregnancy. Environ. Int. 2021, 155, 106676. Erratum in Environ Int. 2021 Oct;155:106676. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-L.; Wen, H.-J.; Chen, M.-L.; Sun, C.-W.; Hsieh, C.-J.; Wu, M.-T.; Wang, S.-L.; TMICS study group Prenatal phthalate exposure and sex steroid hormones in newborns: Taiwan Maternal and Infant Cohort Study. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0297631. [CrossRef]

- Bedrak, E.; Brandes, O.; Fried, K. Profiles of steroids during third trimester of pregnancy in women: Effect of hot, dry desert environment. J. Therm. Biol. 1980, 5, 235–241. [CrossRef]

- Vähä-Eskeli, K.; Erkkola, R.; Irjala, K.; Uotila, P.; Poranen, A.-K.; Säteri, U. Responses of placental steroids, prostacyclin and thromboxane A2 to thermal stress during pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1992, 43, 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Plusquin, M.; Wang, C.; Cosemans, C.; Roels, H.A.; Vangeneugden, M.; Lapauw, B.; Fiers, T.; T’sJoen, G.; Nawrot, T.S. The association between newborn cord blood steroids and ambient prenatal exposure to air pollution: findings from the ENVIRONAGE birth cohort. Environ. Heal. 2023, 22, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Colicino, E.; Cowell, W.; Pedretti, N.F.; Joshi, A.; Youssef, O.; Just, A.C.; Kloog, I.; Petrick, L.; Niedzwiecki, M.; Wright, R.O.; et al. Maternal steroids during pregnancy and their associations with ambient air pollution and temperature during preconception and early gestational periods. Environ. Int. 2022, 165, 107320. [CrossRef]

- Maitre, L.; Lau, C.-H.E.; Vizcaino, E.; Robinson, O.; Casas, M.; Siskos, A.; Want, E.J.; Athersuch, T.; Slama, R.; Vrijheid, M.; et al. Assessment of metabolic phenotypic variability in children’s urine using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep46082. [CrossRef]

- Diviccaro S, Giatti S, Cioffi L, Chrostek G, Melcangi RC. The gut-microbiota-brain axis: Focus on gut steroids. J Neuroendocrinol. 2025;37(7):e13471. [CrossRef]

- Dadvand, P.; Gascon, M.; Bustamante, M.; Rivas, I.; Foraster, M.; Basagaña, X.; Cosín, M.; Eixarch, E.; Ferrer, M.; Gratacós, E.; et al. Cohort Profile: Barcelona Life Study Cohort (BiSC). Int J Epidemiol. 2024 Apr 11;53(3):dyae063. [CrossRef]

- Guxens, M.; Aguilera, I.; Ballester, F.; Estarlich, M.; Fernández-Somoano, A.; Lertxundi, A.; Lertxundi, N.; Mendez, M.A.; Tardón, A.; Vrijheid, M.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Residential Air Pollution and Infant Mental Development: Modulation by Antioxidants and Detoxification Factors. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2012, 120, 144–149. [CrossRef]

- Lubin JH, Colt JS, Camann D, Davis S, Cerhan JR, Severson RK, et al. Epidemiologic Evaluation of Measurement Data in the Presence of Detection Limits. Environ Health Perspect. 2004 Dec;112(17):1691–6.

- Magyar, B.P.; Santi, M.; Sommer, G.; Nuoffer, J.-M.; Leichtle, A.; Grössl, M.; E Fluck, C. Short-Term Fasting Attenuates Overall Steroid Hormone Biosynthesis in Healthy Young Women. J. Endocr. Soc. 2022, 6, bvac075. [CrossRef]

- Ondřejíková L, Pařízek A, Šimják P, Vejražková D, Velíková M, Anderlová K, et al. Altered Steroidome in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Focus on Neuroactive and Immunomodulatory Steroids from the 24th Week of Pregnancy to Labor. Biomolecules. 2021 Dec;11(12):1746. [CrossRef]

- Guxens M, Ballester F, Espada M, Fernández MF, Grimalt JO, Ibarluzea J, et al. Cohort Profile: The INMA—INfancia y Medio Ambiente—(Environment and Childhood) Project. Int J Epidemiol. 2012 Aug 1;41(4):930–40. [CrossRef]

- Hadlock, F.P.; Harrist, R.B.; Sharman, R.S.; Deter, R.L.; Park, S.K. Estimation of fetal weight with the use of head, body, and femur measurements—A prospective study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1985, 151, 333–337. [CrossRef]

- Salomon L j., Alfirevic Z, Da Silva Costa F, Deter R l., Figueras F, Ghi T, et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: ultrasound assessment of fetal biometry and growth. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53(6):715–23.

- Iñiguez C, Esplugues A, Sunyer J, Basterrechea M, Fernández-Somoano A, Costa O, et al. Prenatal Exposure to NO2 and Ultrasound Measures of Fetal Growth in the Spanish INMA Cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Feb;124(2):235–42. [CrossRef]

- Mullen, J.; Gadot, Y.; Eklund, E.; Andersson, A.; Schulze, J.J.; Ericsson, M.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Rane, A.; Ekström, L. Pregnancy greatly affects the steroidal module of the Athlete Biological Passport. Drug Test. Anal. 2018, 10, 1070–1075. [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, C.; Comasco, E.; Skalkidou, A.; Sundström-Poromaa, I. Allopregnanolone levels and depressive symptoms during pregnancy in relation to single nucleotide polymorphisms in the allopregnanolone synthesis pathway. Horm. Behav. 2017, 94, 106–113. [CrossRef]

- Miodovnik, A.; Diplas, A.I.; Chen, J.; Zhu, C.; Engel, S.M.; Wolff, M.S. Polymorphisms in the maternal sex steroid pathway are associated with behavior problems in male offspring. Psychiatr. Genet. 2012, 22, 115–122. [CrossRef]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of Postnatal Depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987 Jun;150(6):782–6.

- Remor, E. Psychometric Properties of a European Spanish Version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). Span. J. Psychol. 2006, 9, 86–93. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Heal. Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–96. [CrossRef]

- Coll-Risco, I.; Camiletti-Moirón, D.; Acosta-Manzano, P.; Aparicio, V.A. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire (PPAQ) into Spanish. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2018, 32, 3954–3961. [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. 1st ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. 1 p.

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [CrossRef]

- Vioque, J.; Navarrete-Muñoz, E.-M.; Gimenez-Monzó, D.; García-De-La-Hera, M.; Granado, F.; Young, I.S.; Ramón, R.; Ballester, F.; Murcia, M.; Rebagliato, M.; et al. Reproducibility and validity of a food frequency questionnaire among pregnant women in a Mediterranean area. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 26. [CrossRef]

- Fung TT, McCullough ML, Newby P, Manson JE, Meigs JB, Rifai N, et al. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction2. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Jul 1;82(1):163–73. [CrossRef]

- SR28 - Page Reports : USDA ARS [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/methods-and-application-of-food-composition-laboratory/mafcl-site-pages/sr28-page-reports/.

- Palma- Linares I, Farrán Codina A, Cervera Ral P. Tablas de composición de alimentos por medidas caseras de consumo habitual en España: = Taules de composició d’aliments per mesures casolanes de consum habitual a Espanya. 2005.

- Willett, W.C.; Howe, G.R.; Kushi, L.H. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65 (Suppl. S4), 1220S–1228S. [CrossRef]

- Imma Palma Dra, Farran A, Pilar Cervera Sra. Tablas de composición de alimentos por medidas caseras de consumo habitual en España. Act Dietética. 2008 Dec 1;12(2):85.

- USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 21.

- Li, M.-X.; Yeung, J.M.Y.; Cherny, S.S.; Sham, P.C. Evaluating the effective numbers of independent tests and significant p-value thresholds in commercial genotyping arrays and public imputation reference datasets. Hum. Genet. 2011, 131, 747–756. [CrossRef]

- Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and Variable Selection Via the Elastic Net. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 2005 Apr 1;67(2):301–20. [CrossRef]

- Groemping U. Relative Importance for Linear Regression in R: The Package relaimpo. J Stat Softw. 2007;17:1–27. [CrossRef]

| Domain | Variable | Gestational Weeks | Hormonal Class Affected | Main Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical parameters | Gestational age | 5–40 (incl. 12, 22, 32) | Progestogens, Estrogens, Corticosteroids | Hormone levels increased across pregnancy; DHEAS decreased. Later gestational age is linked to higher estradiol and testosterone. | Soldin et al. (2005); Thompson et al. (2013); Liang et al. (2020); Chen et al. (2022) |

| Preeclampsia | 8–38, 15 | Androgens, Estrogens | Preeclampsia is associated with lower estrogens, higher testosterone, and altered estrogen metabolism. | Lan et al. (2020); Cantonwine et al. (2019) | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 12, 35–39 | Androgens, Estrogens | Higher BMI correlated with lower estrogens and higher androgens. | Kallak et al. (2017); Barrett et al. (2019) | |

| Weight gain during pregnancy | 12, 25, 26–31, 33, 35–39 | Progestogens, Estrogens, Androgens | Positive associations with progesterone, estrogens, and testosterone levels. | Lof et al. (2009); Petridou et al. (1992); Kallak et al. (2017) | |

| In vitro fertilization | 3 | Progestogens, Androgens | Higher levels of multiple progestogens and androgens after embryo transfer. | Biró et al. (2012) | |

| Parity | 12, 25, 33, 35–39 | Estrogens, Androgens | Nulliparous women had higher estradiol; primiparous women had higher testosterone. | Lof et al. (2009); Kallak et al. (2017) | |

| PCOS | 34, 39 | Androgens, Estrogens, Progestogens | PCOS is associated with elevated testosterone, androstenedione, and progesterone levels. | Maliqueo et al. (2013); Piltonen et al. (2019); Liu et al. (2018) | |

| Fetuses | Sex of the fetus | Birth | Androgens | Higher cord serum testosterone in males; different androgen profiles in hair and cord blood by fetal sex. | Koskivouri et al. (2023) |

| Genetic | Maternal SNPs | 12, 35–39 | Androgens, Estrogens | rs700518 and UGT2B17 are associated with altered testosterone and estrogen ratios. | Kallak et al. (2017); Mullen et al. (2018); Farhan et al. (2020) |

| Lifestyle | Smoking | 37–42 | Progestogens, Estrogens | Lower progesterone and estradiol concentrations in cord blood of active smokers. | Piasek et al. (2023) |

| Vitamin A | 26–31 | Estrogens | Negative association between vitamin A levels and estradiol/total estrogens. | Petridou et al. (1992) | |

| Vitamin D | - | Androgens | Lower 25(OH)D levels associated with reduced testosterone, androstenedione, and DHEAS. | Chu et al. (2021) | |

| Fat intake | 12, 25, 33 | Estrogens | No association between dietary fat intake (n-3/n-6 PUFA) and plasma estradiol levels. | Lof et al. (2009) | |

| Physical activity | - | Progestogens, Estrogens | Estriol levels increased acutely after exercise; progesterone and estradiol slightly declined post-exercise. | Rauramo et al. (1982) | |

| Sleep | 22–24 | Corticosteroids | Poor sleep quality associated with lower cortisol. | Crowley et al. (2016) | |

| Alcohol | 4–40, 12 | Progestogens, Estrogens | Lower estradiol, estriol, and progesterone levels observed in fetal alcohol syndrome cases | Halmesmäki et al. (1987) | |

| Mental health | Depression | 35–39 | Androgens | Positive correlation between depression scores and testosterone levels. | Kallak et al. (2017) |

| Stress | <14, 22–24 | Androgens, Progestogens, Corticosteroids | Stress (neighborhood disorder) linked to higher testosterone in male fetus carriers; cortisol and progesterone associated with emotional resilience. | Hansel et al. (2023); Crowley et al. (2016) | |

| Sociodemographic | Maternal age before pregnancy | 12, 35–39 | Androgens, Estrogens | Older mothers had lower testosterone and estrogen levels. | Kallak et al. (2017); Barrett et al. (2019) |

| Ethnicity | 12 | Androgens | Higher androgen levels (18–30%) among Black women. | Barrett et al. (2019) |

| BiSC (n=721) |

INMA Sabadell (n=500) | |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (year) | 34.4 (4.4); 34.8 [18.4, 45.7] 1 |

31.2 (4.3); 31.2 [17.7, 42.5]1 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Gestational age at sampling collection | 34.7 (1.5); 34.7 [28.9, 39.0]1 |

34.3 (1.6); 34.14 [28.3, 40.6]1 |

| BMI * (kg/m2) | 24.1 (4.4); 23.2 [15.9, 51.8] 1 |

23.9 (4.6); 22.7 [17.0, 53.8] 1 |

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), n (%) | 22 (4) | 25 (5) |

| Normal weight (18.5 – 25 kg/m2) n (%) | 434 (64) | 331 (66) |

| Overweight (25 – 30 kg/m2), n (%) | 155 (23) | 102 (20) |

| Obese (>30 kg/m2), n (%) | 63 (9) | 42 (8) |

| Missing | 47 | 0 |

| Mother country of birth, n (%) | ||

| Spain | 498 (69) | 446 (89) |

| Latin America | 165 (23) | 36 (7) |

| Others | 57 (8) | 18 (4) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Maternal education, n (%) | ||

| Primary or without education | 27 (4) | 4 (1) |

| Secondary | 175 (24) | 132 (27) |

| Technical or University | 519 (72) | 362 (73) |

| Missing | 1 | 2 |

| Parity, n (%) | ||

| Nulliparous | 443 (61) | 282 (57) |

| Primiparous | 229 (32) | 185 (37) |

| Multiparous | 49 (7) | 31 (6) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 |

| Alcohol during pregnancy (daily intake), n (%) | ||

| 0.4-1g/day | 18 (3) | 33 (7) |

| 1g/day or more | 13 (2) | 36 (7) |

| None | 593 (95) | 429 (86) |

| Missing | 97 | 2 |

| Smoking at the beginning of pregnancy, n (%) | ||

| between 1 and 10 cig/day | 10 (2) | 48 (10) |

| more than 10 cig/day | 15 (2) | 19 (4) |

| No smoking | 684 (96) | 427 (86) |

| Missing | 12 | 6 |

| Season, n (%) | ||

| Autumn | 179 (25) | 139 (28) |

| Spring | 175 (24) | 139 (28) |

| Summer | 214 (30) | 107 (22) |

| Winter | 153 (21) | 111 (22) |

| Missing | - | 4 |

| Covid confinement, n (%) | - | |

| Yes | 194 (27) | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).