1. Introduction

The exponential growth of mobile communication has brought numerous benefits but has also led to a surge in unsolicited and fraudulent text messages[1], commonly referred to as spam. Short Message Service (SMS) spam not only clutters user inboxes but also poses risks such as financial scams, phishing, and exposure to malicious links[2]. Detecting spam messages accurately remains a critical task in natural language processing (NLP), particularly for applications in cybersecurity and user safety[3].

Traditional spam detection approaches relied heavily on handcrafted rules and keyword-based filtering, which often failed to adapt to the evolving tactics of spammers[4]. With the advent of machine learning, text classification techniques have gained significant attention for their ability to learn patterns from labeled datasets and generalize to unseen data[5]. Preprocessing, however, plays a decisive role in determining the performance of such classifiers, as noisy or redundant text features can adversely affect prediction accuracy[6].

Among the most widely used NLP toolkits, the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) and spaCy provide a variety of preprocessing utilities such as tokenization, lemmatization, and stopword removal. While both libraries are extensively adopted in research and industry, there has been limited comparative analysis of their effectiveness in real-world classification tasks like SMS spam detection. Addressing this gap is essential, as practitioners and researchers often face the practical challenge of selecting the most suitable toolkit for their applications[7,8,9,10].

In this paper, we conduct a comparative study of NLTK- and spaCy-based preprocessing pipelines using the UCI SMS Spam Collection dataset, a well-established benchmark for spam classification. Logistic Regression is employed as a lightweight yet effective baseline classifier, allowing us to isolate and evaluate the impact of preprocessing choices on overall model performance[11,12,13]. Furthermore, we incorporate error analysis through confusion matrices, word clouds, and keyword frequency visualizations to highlight the types of linguistic patterns that lead to misclassification.

The contributions of this work are threefold:

We presented a reproducible and accessible comparison of NLTK and spaCy preprocessing in the context of SMS spam detection.

We evaluated the influence of preprocessing pipelines on classification performance using multiple metrics, including precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC.

We provided an error analysis that identifies linguistic weaknesses in each approach, offering insights for future improvements.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work in spam detection and text preprocessing.

Section 3 describes the methodology, including dataset and experimental setup.

Section 4 presents results and error analysis.

Section 5 concludes the paper and suggests directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

SMS spam detection has appeared as an important application within NLP and machine learning domain, progressing from early statistical models to advanced deep learning frameworks[11,12,13]. Initial research focused on fundamental feature extraction and classification methods, which demonstrated the feasibility of applying ML to text-based spam filtering. For example, researchers used the bag-of-words representation combined with a Naïve Bayes classifier to distinguish between spam and legitimate messages, achieving competitive accuracy on benchmark datasets such as the UCI SMS Spam Collection[14].

[15] investigated a range of feature extraction and selection techniques in Python, applying multiple classifiers to benchmark datasets. For instance, they compared term TFIDF (term frequency document inverse frequency) features with word n-grams, and evaluated classifiers such as Logistic Regression, Random Forests, and Support Vector Machines, showing that TF–IDF with SVM produced the highest accuracy.

[16] applied diverse ML algorithms and emphasized the significance of preprocessing in model performance. For example, they demonstrated that applying text normalization (such as stemming and stopword removal) before training classifiers like k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) and Decision Trees improved F1-scores by reducing noise in the dataset.

Recent works highlight comparative evaluations between shallow and deep models. [2] investigated evasive techniques in SMS spam filtering, revealing the robust gaps between shallow ML models and deep neural networks. [17] presented a comparative analysis of ensemble methods such as Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and AdaBoost against traditional classifiers, underscoring the superiority of ensembles. [49] further compared ML approaches for SMS spam detection, pointing out challenges in scalability.

Many comprehensive surveys also provide valuable insights. Al Saidat et al. [6] presented a survey of NLP and ML-based spam detection techniques, benchmarking algorithms against accuracy, precision, and recall. [8] explored both ML and deep learning methods, applying datasets from UCI to build robust models. [1] applied machine learning with focus on Relevance Vector Machines (RVM), highlighting real-time application challenges, while [11] introduced an ML-based approach with high accuracy on benchmark datasets.

The integration of NLP techniques has expanded the scope of spam detection. [12] proposed SMS spam classification using NLP-based pipelines to enhance detection performance. [14] investigated named entity recognition (NER) with SpaCy for improving text classification while ensuring privacy preservation. [4] benchmarked text preprocessing algorithms, noting SpaCy Tokenizer’s superior lexical diversity. Similarly, [18,19] discussed preprocessing applications leveraging NLTK, while [21] highlighted challenges in multilingual preprocessing for Japanese texts.

Additional preprocessing improvements were studied in Rianto et al. [16], where stemming improved classification accuracy, and [23], who corrected misspelled words to enhance Indonesian text classification. [25] provided a comprehensive guide on NLP toolkits such as spaCy, NLTK, and Keras for text analysis. [26] leveraged spaCy for email spam classification, while [28] compared ML models across multiple platforms including SKLearn, NLTK, and spaCy. Parallel advancements in related ML domains provide context for SMS spam research[20,22,24]

Collectively, these studies highlight the diverse evolution of SMS spam detection, contextualized within broader AI and ML research[27,28,29]. The literature demonstrates the importance of preprocessing, model selection, cross-domain applications, and security frameworks in building resilient spam detection systems.

3. Methodology

This research adopts a structured approach to SMS spam detection, combining robust preprocessing techniques with classical machine learning algorithms[30,31,32]. The methodology focuses on comparing different feature extraction methods to identify the most effective approach for accurate classification[33,34,35].

3.1. Data Collection

The SMS dataset we used in this study was obtained from publicly available repositories and consists of both spam and ham (non-spam) messages [36,37]. Each message is labeled, enabling a supervised learning framework for classification [38,39,40]. The dataset we selected covers wide range of messages that vary in language, length, and structure, allowing the models to recognize diverse linguistic patterns linked to spam detection. To improve the quality of the input, preprocessing techniques such as text normalization, tokenization, and stopword removal were applied. The choosen dataset provides a reliable benchmark for assessing the performance of classification algorithms in practical spam filtering scenarios.

3.2. Text Preprocessing

Preprocessing plays a crucial role in enhancing model performance. Two feature extraction approaches were employed: NLTK and spaCy. Standard preprocessing steps included lowercasing, tokenization, removal of stopwords, and filtering based on word length. This allowed the models to focus on meaningful textual patterns while reducing noise[41,42,43]. The removal of punctuation marks, numerical characters, and special symbols were done to ensure consistency across the dataset. The Lemmatization techniques were also applied which reduces words to their base/dictionary form, this in turn improves generalization across different word variations. We also tested stemming for comparing these results, though lemmatization yielded more semantically meaningful results. Also, the whitespace normalization and duplicate removal were performed to further refine the dataset. All these preprocessing steps ensured a clean and structured input for the classification models, significantly improving their robustness and reliability.

3.3. Feature Representation

For NLTK, the features were represented using token counts and TF-IDF vectors capturing both the frequency and relative importance of terms within the dataset. Token counts provided a straightforward representation by simply recording how often each word appears in a document, forming the basis for the traditional Bag-of-Words (BoW) model.

Although this approach is easy to implement and computationally efficient, it treats all words as independent units and ignores contextual meaning. The limitation was addressed, TF-IDF weighting was applied, which downscales the impact of frequently occurring but less informative words (such as “the” or “and”) while giving more weight to terms that are unique and therefore more discriminative. This property makes TF-IDF particularly effective in text classification tasks like spam detection, where certain keywords carry strong predictive power [44,45].

On the other hand, spaCy was employed to leverage its pre-trained language models for extracting contextual embeddings. Unlike BoW and TF-IDF, which rely solely on surface-level frequency statistics, embeddings encode semantic and syntactic information by mapping words into dense, continuous vector spaces. This enables the model to capture relationships such as word similarity and contextual usage, which are often lost in traditional representations. For example, words like “offer” and “deal” may appear in different contexts but convey similar intent in spam messages. Embedding-based representations allow the classifier to recognize such semantic parallels, thereby improving classification accuracy. SpaCy’s embeddings are derived from large-scale corpora, ensuring that the representations are both generalizable and context-sensitive.

The contrast between these two approaches highlights a broader trade-off in feature engineering for text classification. TF-IDF is highly interpretable and computationally lightweight, making it ideal for baseline models and smaller datasets. It lacks the ability to capture deeper linguistic nuances or contextual meaning. Embeddings are computationally more demanding but offer richer representations that can adapt to varied sentence structures and subtle semantic cues. In spam detection, this can make the difference between correctly identifying a cleverly disguised spam message and misclassifying it as ham.

Combining traditional and modern feature extraction techniques can yield robust results. For instance, hybrid models that integrate TF-IDF features with embeddings have been shown to enhance performance by exploiting the complementary strengths of both approaches. TF-IDF ensures that highly discriminative keywords are not overlooked, while embeddings contribute contextual depth and semantic understanding. These combinations are particularly useful when dealing with real-world datasets that exhibit high variability, as in the SMS dataset used in this study.

3.4. Model Selection

Classical machine learning classifiers, including Logistic Regression and Naive Bayes, were selected due to their efficiency and interpretability in text classification tasks. Each model was trained and evaluated using both NLTK and spaCy features to compare performance[46,47].

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

The models were assessed using standard metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. Additionally, ROC and precision-recall curves were employed to evaluate the classifiers’ discriminative power and balance between precision and recall[48,49].

The choice of selecting both NLTK-derived features (token counts and TF-IDF vectors) and spaCy-based embeddings allowed for a comprehensive comparison of how different feature representations impact classifier performance.

4. Results

The experimental evaluation provides a comparative assessment of the performance of multiple machine learning classifiers when applied to SMS spam detection using two distinct feature extraction techniques: NLTK-based preprocessing and spaCy-based preprocessing. To offer a comprehensive view, we present both quantitative performance measures and qualitative visualization of errors and decision patterns.

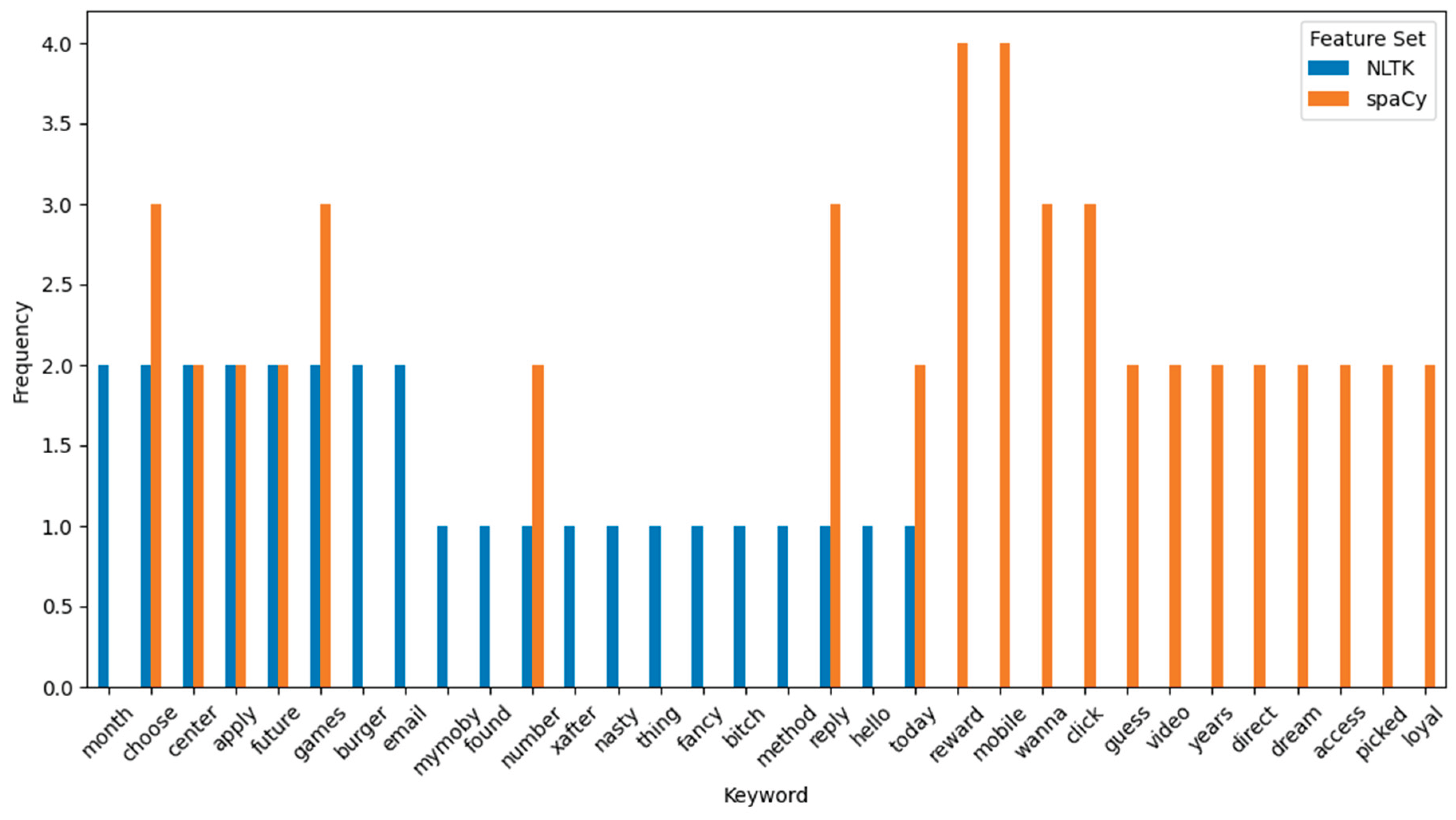

The initial analysis examined the distribution of misclassified terms by extracting the most frequent keywords among incorrect predictions for both NLTK and spaCy pipelines. As shown in

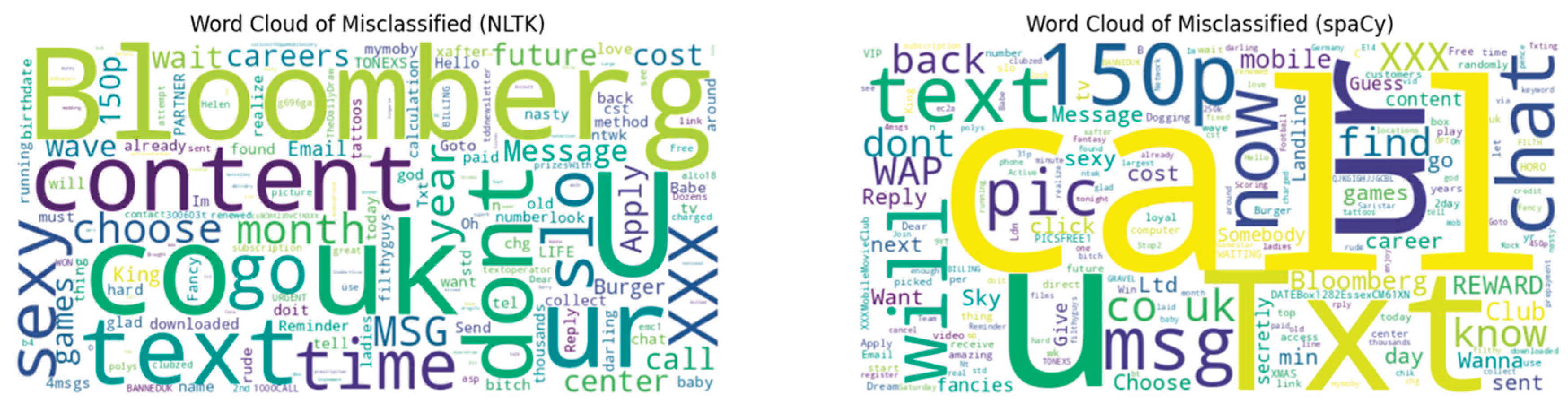

Figure 1, the side-by-side bar chart highlights common tokens that frequently contributed to misclassifications. To complement this, word clouds were generated to provide a more intuitive representation of high-frequency misclassified terms. The visualization in

Figure 2 clearly reveals that the linguistic patterns associated with short promotional content were a key source of false positives and negatives.

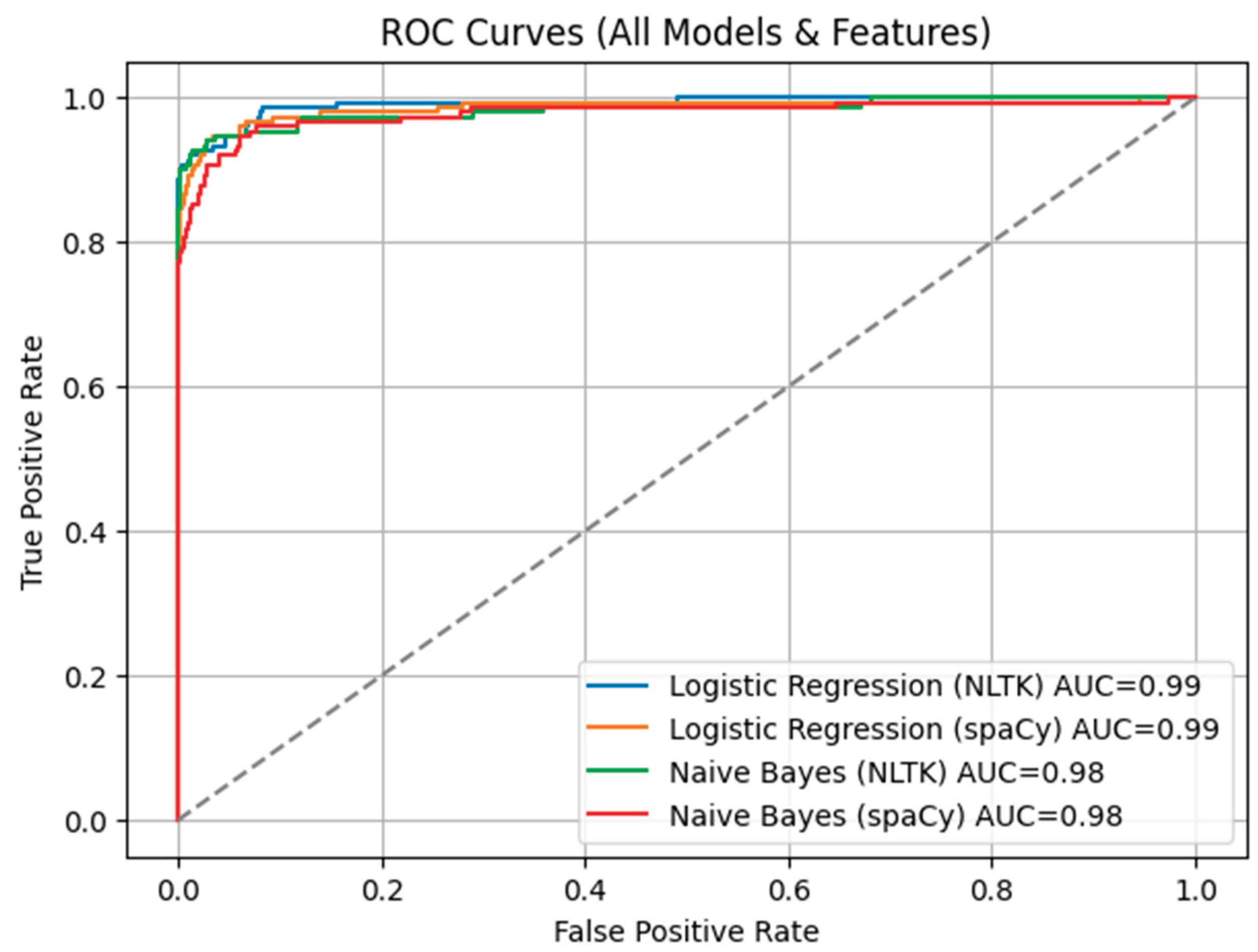

To further evaluate classification boundaries, ROC curves were plotted for all models under both feature sets (

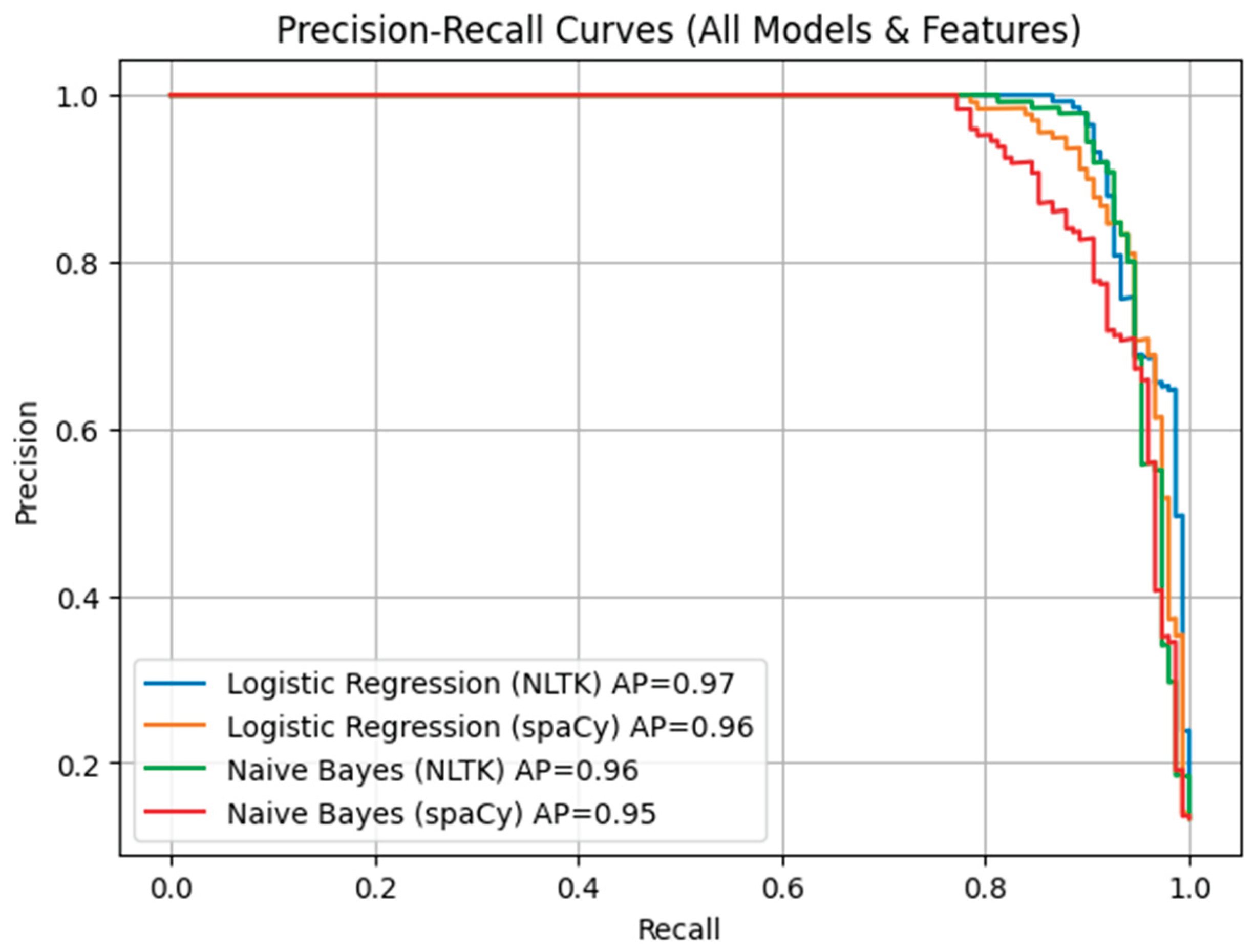

Figure 3). The ROC analysis indicates that Logistic Regression with NLTK features achieved the highest AUC, suggesting better discrimination between spam and ham messages. Similarly, Precision–Recall (PR) curves (

Figure 4) highlight that Naïve Bayes with NLTK preprocessing delivered superior recall performance, while spaCy features tended to increase precision at the cost of recall.

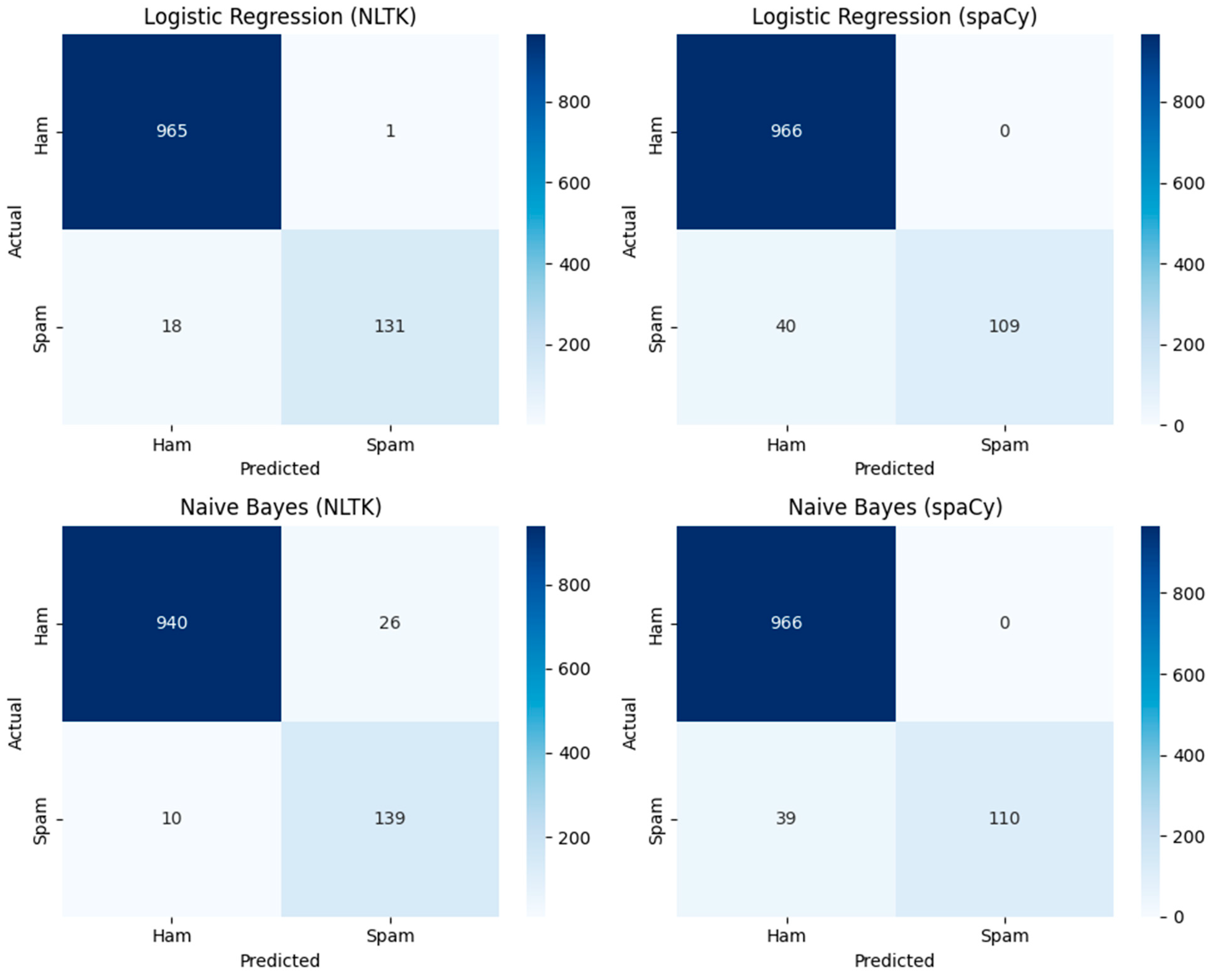

Error analysis was performed using confusion matrices across all classifiers and feature combinations (

Figure 5). These visualizations reveal that NLTK-based feature extraction generally yielded fewer false negatives compared to spaCy, especially for Logistic Regression and Naïve Bayes. However, spaCy tended to minimize false positives, indicating that each feature extraction pipeline carries distinct trade-offs.

A consolidated comparison of model performance metrics is provided in

Table 1. Logistic Regression with NLTK features achieved the highest accuracy (98.29%) and F1 score (0.932), while Naïve Bayes with NLTK demonstrated a better balance between recall (0.933) and precision (0.842). In contrast, spaCy-based models achieved perfect precision in some cases but at the cost of significantly lower recall, reflecting reduced sensitivity in spam detection.

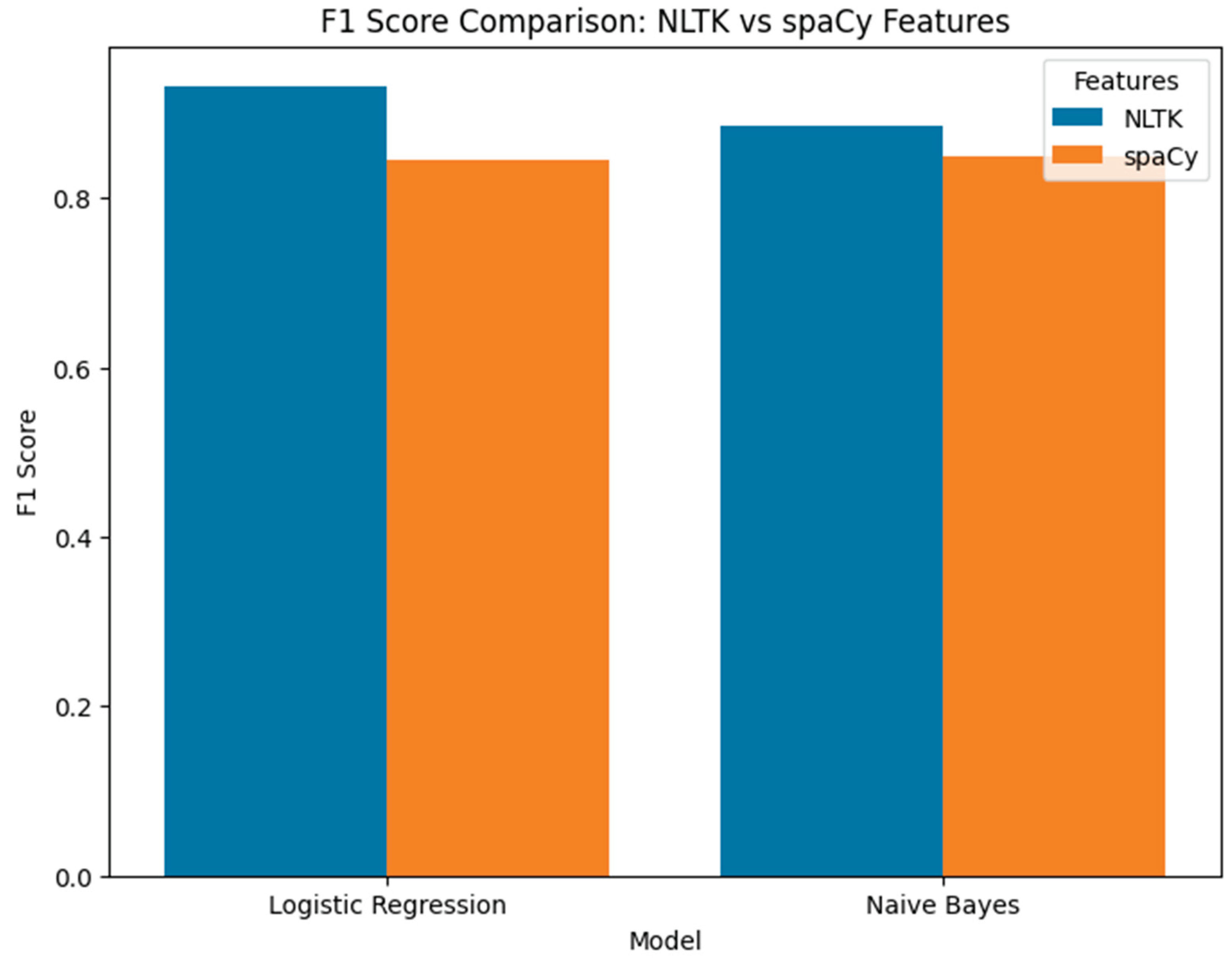

To visualize the comparative effectiveness of the models,

Figure 6 presents a bar plot of F1 scores across classifiers for both feature sets. The results confirm that NLTK preprocessing consistently provides a more balanced outcome compared to spaCy, particularly in terms of recall and overall F1 performance. These findings are also consistent with earlier error and keyword distribution analyses, where NLTK captured more context from misclassified cases.

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of comparing feature extraction approaches, specifically NLTK and spaCy, for SMS spam detection using classical machine learning models. The results indicate that while both feature sets yield high overall accuracy, NLTK-based features generally provide a more balanced trade-off between precision and recall, resulting in higher F1 scores, whereas spaCy features tend to favor precision at the expense of recall. This highlights the importance of feature selection in optimizing model performance depending on the application’s requirements, whether prioritizing minimizing false positives or maximizing correct spam detection. Overall, the findings emphasize that careful preprocessing and feature representation significantly influence the reliability and robustness of automated SMS spam classifiers, providing actionable insights for deploying real-world text classification systems.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we explored the effectiveness of different feature extraction methods and machine learning models for SMS spam detection. The results demonstrate that careful preprocessing and model selection can significantly improve classification performance, highlighting the potential of combining classical algorithms with tailored text features for practical spam filtering applications.

6. Limitations and Future Work

Limitations:

The study is limited to a specific dataset, which may not fully represent all types of SMS spam encountered in real-world scenarios.

Only a subset of machine learning models and feature extraction techniques were explored, leaving other potentially effective approaches unexamined.

Future Work:

Expanding the dataset to include diverse languages and SMS formats could improve model generalizability.

Investigating advanced deep learning architectures and ensemble methods may further enhance detection accuracy and robustness.

References

- Gedam, R.H.; Banchhor, S.K. Study of SMS Spam Detection Using Machine Learning Based Algorithms. Int. Res. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. (IRJAEM) 2025, 3, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Ikram, M.; Kaafar, M.A. Investigating Evasive Techniques in SMS Spam Filtering: A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Models. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 24306–24324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, D.; Jhanjhi, N.; Khan, N.A.; Ray, S.K.; Al Mazroa, A.; Ashfaq, F.; Das, S.R. Towards the future of bot detection: A comprehensive taxonomical review and challenges on Twitter/X. Comput. Networks 2024, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M. T. , & Baawi, S. S. (2024, January). Email spam detection by machine learning approaches: a review. In International Conference on Forthcoming Networks and Sustainability in the AIoT Era (pp. 186-204). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Tyagi, S.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, G. Enhancing SMS Classification with Ensemble Machine Learning Techniques. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Communication, Computing and Signal Processing (IICCCS). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Ashfaq, F.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Khan, N.A. Badminton player’s shot prediction using deep learning. In Innovation and Technology in Sports: Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovation and Technology in Sports,(ICITS) 2022, Malaysiya; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore; pp. 233–243.

- Johari, M.F.; Chiew, K.L.; Hosen, A.R.; Yong, K.S.; Khan, A.S.; Abbasi, I.A.; Grzonka, D. Key insights into recommended SMS spam detection datasets. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Saidat, M.R.; Yerima, S.Y.; Shaalan, K. Advancements of SMS Spam Detection: A Comprehensive Survey of NLP and ML Techniques. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 244, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadde, S.; Sajja, P.; Reddy, R. SMS Spam Classification Using Deep Learning and Machine Learning Methods. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2020, 9(3), 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharrao, D.; Gaikwad, P.; Gawai, S.V.; Bongale, A.M.; Pate, K.; Singh, A. Classifying SMS as Spam or Ham: Leveraging NLP and Machine Learning Techniques. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Eng. 2024, 14, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, F. , Jhanjhi, N. Z., Khan, N. A., & Das, S. R. (2023, February). Synthetic crime scene generation using deep generative networks. In International conference on mathematical modeling and computational science (pp. 513-523). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Ozoh, E. , Sogbaike, O., & Akinyemi, J. (2020). A Novel Implementation of SMS Spam Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms.

- Oyeyemi, O. & Ojo, A. (2018). SMS Spam Filtering Using Natural Language Processing Techniques.

- Das, S. R. , Jhanjhi, N. Z., Asirvatham, D., Ashfaq, F., & Abdulhussain, Z. N. (2023, February). Proposing a model to enhance the IoMT-based EHR storage system security. In International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science (pp. 503-512). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Kutbi, A. (2020). Named Entity Recognition Using SpaCy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A. , & Yadav, R. (2025, July). SMS Spam Detection with NLP and Ensemble Learning for Enhanced Classification. In 2025 International Conference on Computing Technologies & Data Communication (ICCTDC) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Alourani, A.; Ashfaq, F.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Khan, N.A. BiLSTM- and GNN-Based Spatiotemporal Traffic Flow Forecasting with Correlated Weather Data. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airlangga, G. Optimizing SMS Spam Detection Using Machine Learning: A Comparative Analysis of Ensemble and Traditional Classifiers. J. Comput. Networks, Arch. High-Performance Comput. 2024, 6, 1942–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, J. (2018). Python NLP Preprocessing with NLTK. Journal of Machine Learning Applications.

- Purwanto, D. & Rizaldi, A. (2020). Text Preprocessing for Indonesian SMS Spam Classification. Procedia Computer Science.

- Alshudukhi, K.S.S.; Ashfaq, F.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Humayun, M. Blockchain-Enabled Federated Learning for Longitudinal Emergency Care. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 137284–137294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahutomo, F. , Sari, R., & Ruli, F. (2020). Preprocessing for Japanese SMS Spam Detection. Journal of Information and Communication Technology.

- Rianto, R. , Nugroho, R., & Setiawan, H. (2021). Improving SMS Spam Classification Using Stemming and Misspelling Correction. International Conference on Computer Engineering and Applications.

- Setiabudi, A. , Pratiwi, R., & Utami, D. (2020). Preprocessing Techniques for SMS Spam Detection in Bahasa Indonesia. Journal of Information Systems Engineering.

- Jhanjhi, N. Comparative Analysis of Frequent Pattern Mining Algorithms on Healthcare Data. 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, BahrainDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–10.

- Srinivasa-Desikan, B. (2018). Natural Language Processing and Text Analysis with SpaCy and Keras. Springer.

- Taghandiki, A. (2019). Spam Email Classification Using Text Preprocessing and Machine Learning. Journal of Information Technology and Software Engineering.

- Jhanjhi, N.Z. (2025). Investigating the Influence of Loss Functions on the Performance and Interpretability of Machine Learning Models. In: Pal, S., Rocha, Á. (eds) Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science. ICMMCS 2025. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 1399. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Miao, J. , Xu, H., & Zhang, Q. (2020). Comparative Evaluation of Text Preprocessing Methods for Classification. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering.

- Ashfaq, F.; Jhanjhi, N.; Khan, N.A.; Javed, D.; Masud, M.; Shorfuzzaman, M. Enhancing ECG Report Generation With Domain-Specific Tokenization for Improved Medical NLP Accuracy. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 85493–85506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschitti, A. , & Basili, R. (2004, April). Complex linguistic features for text classification: A comprehensive study. In European conference on information retrieval (pp. 181-196). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Farkiya, A.; Saini, P.; Sinha, S.; Desai, S. Natural language processing using NLTK and wordNet. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol 2015, 6(6), 5465–5469. [Google Scholar]

- Lezama-Sánchez, A.L.; Vidal, M.T.; Reyes-Ortiz, J.A. An Approach Based on Semantic Relationship Embeddings for Text Classification. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeniya, N. , Perkins, J., Chopra, D., Joshi, N., & Mathur, I. (2016). Natural language processing: python and NLTK. Packt Publishing Ltd.

- JingXuan, C.; Tayyab, M.; Muzammal, S.M.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Ray, S.K.; Ashfaq, F. Integrating AI with Robotic Process Automation (RPA): Advancing Intelligent Automation Systems. 2024 IEEE 29th Asia Pacific Conference on Communications (APCC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndonesiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 259–265.

- Faisal, A. , Jhanjhi, N. Z., Ashraf, H., Ray, S. K., & Ashfaq, F. (2025). A Comprehensive Review of Machine Learning Models: Principles, Applications, and Optimal Model Selection. Authorea Preprints.

- Al-Doulat, A.; Obaidat, I.; Lee, M. Unstructured Medical Text Classification using Linguistic Analysis: A Supervised Deep Learning Approach. 2019 IEEE/ACS 16th International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United Arab EmiratesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–7.

- Razno, M. (2019). Machine learning text classification model with NLP approach. Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Systems, 2, 71-73.

- Javed, D.; Jhanjhi, N.; Ashfaq, F.; Khan, N.A.; Das, S.R.; Singh, S. Student Performance Analysis to Identify the Students at Risk of Failure. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, NamibiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Malik, S. , & Jain, S. (2021, February). Semantic Ontology-Based Approach to Enhance Text Classification. In ISIC (pp. 85-98).

- Meng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Xiong, C.; Ji, H.; Zhang, C.; Han, J. Text Classification Using Label Names Only: A Language Model Self-Training Approach. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 9006–9017.

- Bora, P.S.; Sharma, S.; Batra, I.; Malik, A.; Ashfaq, F. Identification and Classification of Rare Medicinal Plants. 2024 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, NamibiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–6.

- Kumar, M.S.; Vimal, S.; Jhanjhi, N.; Dhanabalan, S.S.; Alhumyani, H.A. Blockchain based peer to peer communication in autonomous drone operation. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 7925–7939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, M. , Islam, N., & Zaman, N. (2019). A lightweight and secure authentication scheme for IoT based e-health applications. International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, 19(1), 107-120.

- Liu, S.; Tang, B.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X. Effects of Semantic Features on Machine Learning-Based Drug Name Recognition Systems: Word Embeddings vs. Manually Constructed Dictionaries. Information 2015, 6, 848–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, V.; Raju, M.S.V.S.B.; Vardhan, B.V. Analysis of lexical, syntactic, and semantic features for semantic textual similarity. Int. J. Comput. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9(5), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, R. , & Gokce, E. (2022). Natural language processing (NLP): An introduction: making sense of textual data. In Applied data science in tourism: Interdisciplinary approaches, methodologies, and applications (pp. 307-334). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Humayun, M.; Khalil, M.I.; Almuayqil, S.N.; Jhanjhi, N.Z. Framework for Detecting Breast Cancer Risk Presence Using Deep Learning. Electronics 2023, 12, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaullah, M.; Ali, M.; Almufareh, M.F.; Ahmad, M.; Hussain, L.; Jhanjhi, N.; Humayun, M. Initial stage COVID-19 detection system based on patients’ symptoms and chest X-ray images. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 2055398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani-Mehr, H. (2013). SMS spam detection using machine learning approach. unpublished), 2013. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).