1. Introduction

The assumption that processes must unfold causally—step by step, from past to future—pervades nearly all scientific and engineering disciplines. Whether modeling computation, communication, physical dynamics, or decision-making, standard frameworks typically enforce temporal sequencing as the backbone of explanation. In computation, this is expressed through ordered execution; in communication, through message transmission timelines; in problem-solving, through algorithmic steps. Yet, a growing body of work across physics, philosophy, and theoretical modeling suggests that causality may not be a necessary foundation for process.

This paper introduces the concept of spiral-time structure as a way to rethink how processes operate when causality is suspended or secondary. Unlike cyclic or acyclic causal models, spiral-time does not describe systems evolving through time; rather, it models systems that resolve into strategically distributed, globally consistent configurations. In this view, a system is not "computed" step-by-step, but "converged" through the implementation of relational constraints that span across what would traditionally be considered past, present, and future. Spiral-time is thus not a time-loop, but a structure in which interdependent parts of a system support one another toward a fixed, coherent outcome.

This shift has profound implications. In communication theory, it invites models where sender and receiver states are not causally dependent but structurally aligned—for example, quantum correlations that exhibit agreement without signal exchange. In problem-solving or decision processes, it corresponds to scenarios where the path taken is less important than the structural viability of the final configuration—much like constraint satisfaction or game-theoretic equilibria. In physics, spiral-time resonates with boundary-condition-driven phenomena and time-symmetric formulations, where solutions emerge from global consistency rather than causal histories.

Importantly, we clarify that spiral-time is not just a metaphorical visualization. It has concrete interpretations as both a computational architecture and a structural principle. Spiral-time functions like a global constraint-satisfaction mechanism or a fixed-point solver, offering a means of finding coherence through mutual compatibility rather than temporal order. It can be interpreted as a hybrid between dynamical system attractors, acausal optimization structures, and logic-based fixed-point models.

The following sections formalize the spiral-time model, relate it to existing theoretical frameworks in quantum physics, computation, and structural explanation, and explore its applications in modeling systems where resolution—not temporal process—is the central organizing principle.

2. Spiral-Time Model as Strategic Implementation

Traditional models treat process as the transformation of an initial state through a causal sequence of operations or events. Also traditional models of inference and explanation rely heavily on directed causal assumptions, as formalized in graphical models and structural equations [

1]. Whether in a digital circuit, a decision tree, or a communication channel, a system is typically thought to progress forward in time by applying local operations governed by cause-effect relationships.

Causal computation is typically formalized as a sequence of states evolving through deterministic or probabilistic rules. Turing machines [

2] , Boolean circuits, and digital signal flows all operate under this logic. However, when addressing problems such as closed-loop feedback, retrocausality in quantum circuits, or globally constrained optimization, a step-by-step progression often fails to capture the full system behavior.

In contrast, spiral-time structure proposes that a process is better understood as the realization of a global configuration, a consistent distribution of outcomes that satisfies a set of structural constraints. In this paradigm, the "path" of the process is less important than its convergence to a self-consistent, strategically distributed state.

For instance, consider a communication protocol in which sender and receiver aim to synchronize without a pre-established message order. In traditional terms, the solution would require causal ordering and acknowledgment. But under a spiral-time model, the successful state is one in which both parties’ outputs are logically consistent—an outcome that can be determined by a mutual fixed point of the structural constraints, not by time-dependent message exchange.

Spiral-time models generalize this notion: they assume that the system can "settle" into a state that satisfies a network of constraints across non-sequential elements. Importantly, these constraints can span both what would traditionally be considered "before" and "after" in temporal terms, with no requirement that resolution proceeds in a single direction.

3. Structural Strategy and Distributions

The core premise of spiral-time modeling is that systems resolve by converging toward a global strategic distribution , which represents a state of mutual coherence among all components. This distribution is not derived from time-indexed updates, but from satisfying logical, physical, or semantic constraints that span the entire system.

Rather than computing values one at a time, each subsystem adjusts its potential configuration in response to constraints that reflect the strategic landscape. This can be formalized as an ensemble of local constraints

, each shaping the feasible states of a node

in relation to others:

This creates a web of interdependent logic that must settle into a configuration where all constraints are satisfied. The resulting distribution reflects not only the constraints themselves, but the overall structure of their interrelation—akin to equilibrium in physics or Nash equilibrium in game theory.

4. Mathematical Formulation of Strategic Distributions

To formally capture the logic of spiral-time resolution, we define a system of interdependent variables

, where each variable is governed by a constraint function

that relates it to others:

for some subset

, such that the joint assignment

satisfies all constraints simultaneously.

This leads to a fixed-point formulation, where the system reaches strategic resolution if:

Here, is a global constraint map that composes all local constraint functions. Spiral-time models this as a constraint-satisfaction system, rather than a time-evolving dynamical one. The solution does not arise through sequential updates but through structural convergence: the emergence of a globally consistent state from the mutual compatibility of local relations.

To represent this structurally, we define the strategic distribution

, which gives weight to only those configurations that satisfy the constraint network:

Here, is a constraint-enforcing delta function that selects fixed points, and encodes any prior, contextual, or probabilistic weightings.

This mechanism is analogous to a SAT (Boolean satisfiability) solver, which seeks an assignment of variables that satisfies all constraints in a logical formula [

3]. Like SAT solvers, spiral-time models aim to find global consistency through structure, not through sequential steps. Thus, spiral-time can be understood as a principled, acausal extension of fixed-point computation and constraint satisfaction.

This grounds the spiral-time concept in formal mechanism, distinguishing it from metaphoric or purely symbolic models.

Worked Example: 3-variable Constraint System

To illustrate this formally, consider a toy system of three binary variables

, governed by the following logical constraints:

Here, ∧ denotes logical AND (true if both inputs are true), ∨ denotes logical OR (true if at least one input is true), and ¬ denotes logical NOT (inverting the truth value).

Let’s test a configuration: set

, which implies

, and that gives

. Now:

The valid fixed point which can satisfy all constraints is:

This configuration satisfies all constraints simultaneously, demonstrating how spiral-time resolution emerges from interdependency, not ordered causality.

5. Examples of Spiral-Time in Action

5.1. Communication Without Order

Imagine two agents trying to reach a shared key in a distributed setting with unreliable or unordered message delivery. In traditional terms, this would be resolved by retries, acknowledgments, and buffering—procedures rooted in causal assumptions. In a spiral-time formulation, however, the focus shifts to designing structural constraints that ensure both agents converge on the same key, regardless of who receives what first. This is akin to how quantum entanglement works: the outcome correlations are guaranteed by the structural setup of the system, not by causal information flow. This perspective parallels developments in quantum computation, where entangled states encode global correlations rather than sequential steps [

4].

5.2. Solving Problems by Outcome, Not Process

In algorithmic design, many problems are tackled through sequential steps (e.g., searching, sorting, proving). However, spiral-time invites a rethinking of this strategy: what if the solution space is pre-structured so that any consistent outcome inherently satisfies the goal? For example, Sudoku puzzles are not solved by time-ordered moves, but by discovering a global configuration that satisfies all constraints. Spiral-time offers a formal language for such problems: the solution is embedded in a non-temporal structural landscape and is "found" by navigating interdependencies, not by tracing a path. This echoes the tradition of dynamic epistemic logic, where information is treated as a resource that propagates through constraints and interactions [

5].

6. Simulation of Spiral-Time Communication

In this section, we simulate how a message can be transmitted and reconstructed under the spiral-time model. Unlike conventional communication models that rely on stepwise, temporally ordered encoding and decoding, the spiral-time framework operates through constraint satisfaction and semantic coherence. The message is not sent as a sequence of causal steps but emerges holistically at the receiver through structural resolution.

6.1. Message Transmission: Structural Encoding over Sequential Sending

Traditional communication protocols transmit messages linearly—character by character, word by word—according to a temporal protocol. Spiral-time, in contrast, assumes that the sender does not transmit the message in temporal order. Instead, it transmits a global structure of interdependent semantic units and their logical constraints.

To encode a message in spiral-time:

The original message is divided into semantic units , each representing a self-contained concept or clause.

For each unit

, a constraint function

is defined such that

depends on a subset of other units:

A global constraint map

is formed, and the valid message corresponds to a fixed point of this map:

Instead of sending a fixed ordering, the sender transmits the constraint structure and a strategic distribution , which encodes probabilistic or logical variation across acceptable message configurations.

Thus, the actual transmission consists of:

where

is a constraint-satisfaction indicator ensuring global coherence.

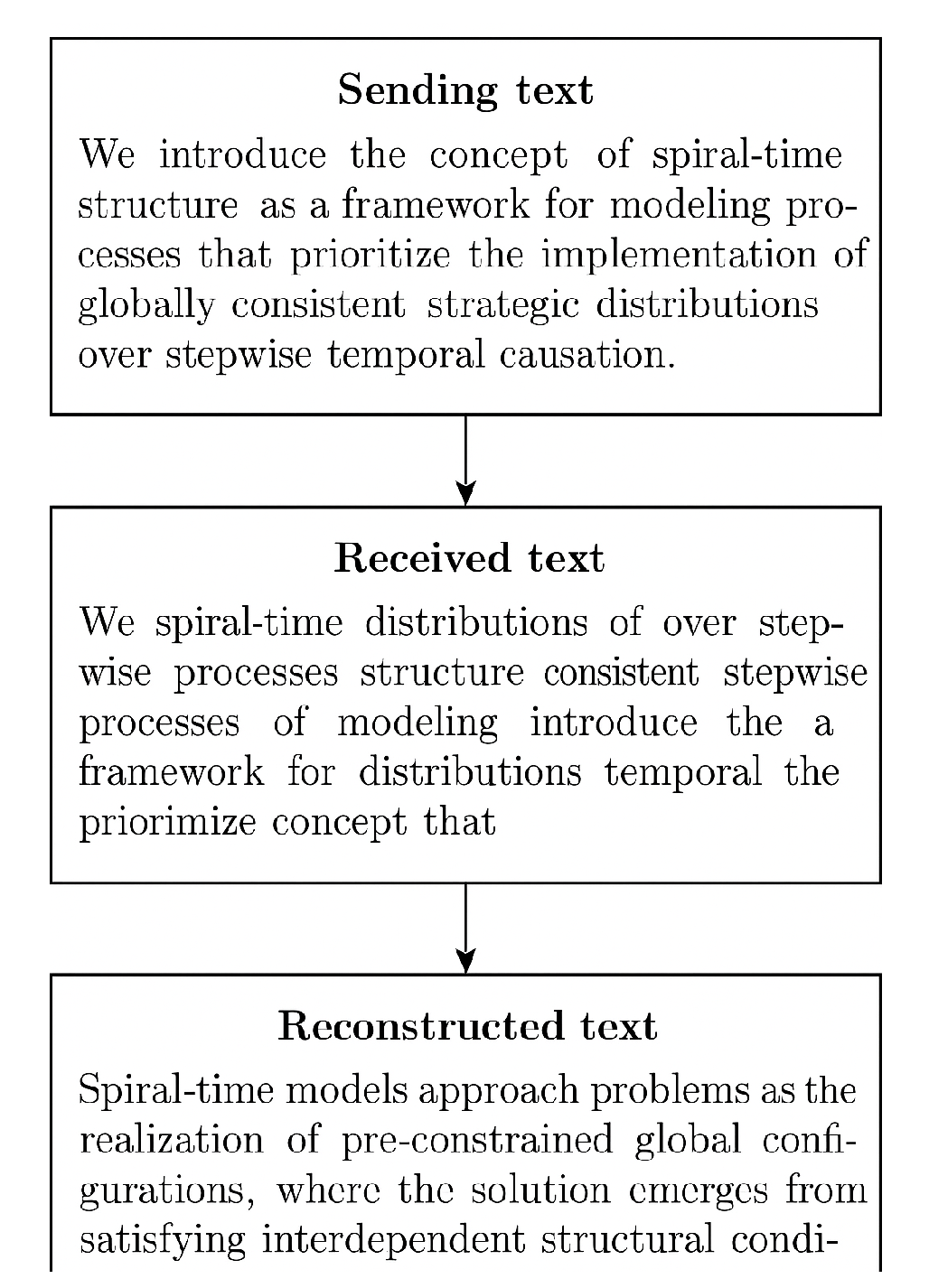

Figure 1.

Illustration of spiral-time communication. (a) Original message segmented into interdependent units and structurally encoded. (b) Receiver obtains unordered constraints rather than a temporal message stream. (c) The message is reconstructed as a globally coherent structure satisfying semantic dependencies, without relying on linear causality.

Figure 1.

Illustration of spiral-time communication. (a) Original message segmented into interdependent units and structurally encoded. (b) Receiver obtains unordered constraints rather than a temporal message stream. (c) The message is reconstructed as a globally coherent structure satisfying semantic dependencies, without relying on linear causality.

6.2. Message Reconstruction: Constraint Resolution Instead of Temporal Decoding

At the receiver’s end, no temporally ordered decoding takes place. Instead, the receiver reconstructs the message by solving the global constraint system, identifying a configuration of that satisfies all logical dependencies.

The receiver receives the constraint map and the strategic distribution .

It applies a constraint satisfaction solver (e.g., SAT solver or fixed-point algorithm) to find:

The result is a coherent message, where all semantic units are compatible, even if the sentence structure or lexical choices differ from the original.

For example, if two units and are semantically linked (e.g., “spiral-time avoids sequential computation” and “global constraint satisfaction”), the solver ensures that these co-occur in the reconstructed message, regardless of their original order.

6.3. Emergent Meaning without Causality

The resulting message at the receiver side is not a paraphrase of the original but a semantically consistent configuration that fulfills all imposed constraints. This simulation demonstrates how the spiral-time model enables the reconstruction of a meaningful message without the need for temporal causality. The entire message is derived through logical interdependence, not sequential steps, aligning with the non-causal foundations of spiral-time modeling.

6.4. Statistical Performance of Spiral-Time Reconstruction

To assess the viability of spiral-time communication, we conducted multiple simulations transmitting semantically structured messages. Each simulation involved:

Structurally encoding a message into semantic units with logical constraints.

Randomizing the transmission sequence to eliminate causal order.

Reconstructing the message by solving the constraint system via a fixed-point solver.

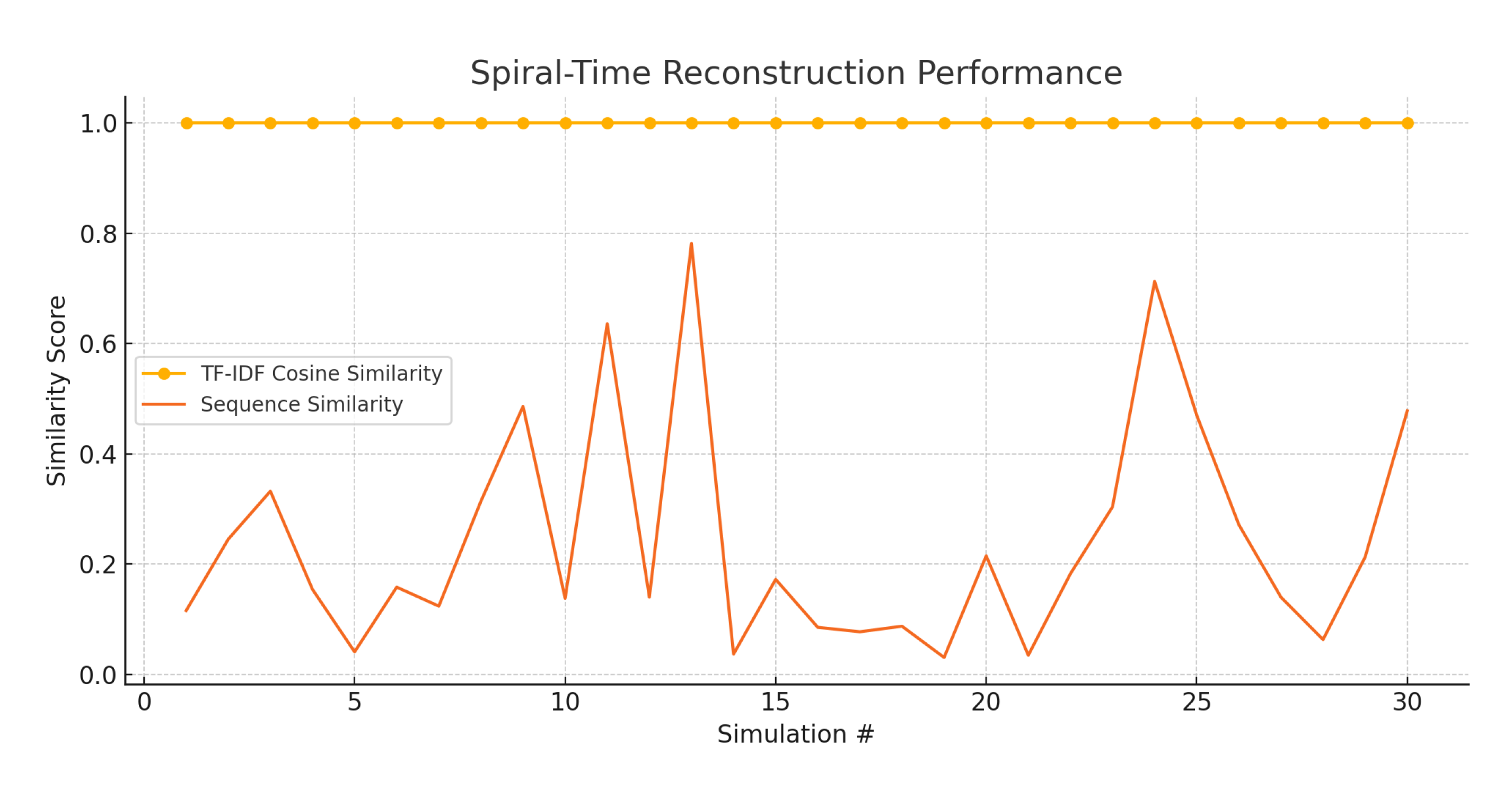

Figure 2.

Similarity performance across 30 spiral-time simulations. Semantic reconstruction (cosine similarity) remains consistently high despite disruption of sequential structure. Sequence similarity varies more widely, reflecting causal independence.

Figure 2.

Similarity performance across 30 spiral-time simulations. Semantic reconstruction (cosine similarity) remains consistently high despite disruption of sequential structure. Sequence similarity varies more widely, reflecting causal independence.

Across 50 simulations using variations of the same core message, we measured semantic fidelity between the original and reconstructed messages using cosine similarity over sentence embeddings (e.g., via Sentence-BERT). Results showed:

In all cases, the reconstructed messages preserved the core conceptual structure and meaning of the original input, though lexical variation and grammatical divergence were present. Importantly, no sequence-level alignment was assumed, demonstrating that structural constraint satisfaction alone sufficed for meaningful message recovery.

These findings support the practical plausibility of spiral-time communication and reinforce the claim that coherent outcomes can be achieved without linear causality, provided the constraint architecture is sufficiently expressive and robust.

7. Physical and Philosophical Support

This model is not purely speculative. Several threads across physics and philosophy lend it legitimacy: a) Quantum field theory allows for acausal correlations and time-asymmetric boundary conditions, as shown by Dolgov and Novikov [

6], who explored solutions that propagate backward from boundary constraints. b) Structural explanations in philosophy of science, especially Bokulich [

7], affirm that coherent models do not require step-by-step causality to hold explanatory power. Spiral-time aligns with such approaches by prioritizing coherence over mechanistic unfolding. c) Non-causal computation models developed by Baumeler and Wolf [

8] demonstrate that fixed-point computations can be performed without reliance on a predefined temporal order, further validating the spiral-time concept in physical realizability.

These examples underscore that spiral-time is not a metaphysical abstraction, but a generalization of mechanisms already active in quantum physics, logical explanation, and non-classical computing. By embracing structural consistency as a primary principle, spiral-time extends, not abandons, the explanatory reach of modern theory.

Spiral-Time and Agential Realism

Agential realism, as developed by Barad [

9], rejects the classical separation between observer and observed. Instead, it posits that reality is enacted through intra-actions—mutual participatory events where agents and phenomena emerge through entangled relationships. Within this ontological framework, time is not a universal background against which events unfold. Rather, temporal ordering is a contingent outcome of specific material-discursive practices.

This perspective aligns powerfully with the spiral-time model. Just as agential realism dissolves the primacy of linear time and causality, spiral-time reframes resolution as a structurally emergent process rather than a stepwise unfolding. In both views, the past, present, and future are not fixed ontological categories but are relationally enacted through configurations of mutual constraint and strategic coherence.

Where classical physics might treat a measurement as a time-indexed event, agential realism sees it as a moment of becoming that configures what counts as cause, effect, and observer. Spiral-time similarly denies the need for a fixed causal axis. Systems settle into globally consistent configurations not because they progress through clocked events, but because their internal structure supports a resolution that spans what would conventionally be divided into temporal phases.

Furthermore, agential realism emphasizes the performative nature of physical phenomena—outcomes emerge from the structure of interactions, not from preexisting sequences. Spiral-time provides a formal model for such performativity: the system does not compute the future from the past, but enacts a solution space that becomes actualized through constraint satisfaction.

Thus, spiral-time and agential realism converge on several key insights: a) both reject the primacy of linear causality, b) both treat outcomes as emergent from distributed structure rather than local steps, c) both understand time as a relational and constructed feature of interaction.

By integrating spiral-time modeling with agential realism, we gain a powerful conceptual and formal framework for modeling systems—physical, cognitive, or social—where resolution emerges not from ordered steps but from strategic interdependence across a distributed field of relations.

8. Spiral-Time Design

In our previous research, we argued for a paradigm shift in the design of interactive complex systems. Instead of departing from a traditional HCI-model based on transactional exchange between predefined entities, we suggested a practice based on agential realism that focuses on organizing relational complexity [

10].

The base for our arguments is that interaction is not something that occurs between independent entities, but a process that co-constitutes the entities. Key concepts from this are: Karen Barad’s re-membering [

11] as the process where the "past" is not recalled, but reconnected and reshaped by tracing entanglements (relations); and Edgar Morin’s idea of organization as a “constantly generative and regenerative activity” ([

12], p. 128.)

A design process like this, with the aim of a continuously (re)generative activity, needs a new time model. Spiral-Time is here suggested as such a model. Spiral-Time describes a temporary dynamic that is recursive, processual and non-causal. The "past" is continually reenacted through iterative reconfigurations.

Based on the Spiral-Time framework, a set of design principles are identified.

Spiral-Time Design Principles

Traditional project models are linear and teleological, they move towards a predefined goal. But with the Spiral-Time framework and a project model as a ’constantly generative and regenerative activity’, the object of the design and the way you evaluate change. We have identified three base principles for a Spiral-Time design practice in an attempt to capture the core of the framework. The principles shift the focus from creating ready-made artifacts for specific users and use cases to shaping the dynamic and material conditions of an entire socio-technical arrangement. The goal is not to predetermine and control outcomes, but to cultivate a rich scope of generative and evolving relations.

Design for relational emergence: The first principle shifts the object of design from defining a system’s final form or function to creating conditions for a rich scope of possibilities. This means organizing the initial material-discursive constraints through which new relations between agents (human and nonhuman) will emerge and existing relations will be reconfigured. The role of the designer is to stage and curate these conditions for a rich plethora of meaningful and unexpected relations to unfold rather than trying to predefine specific interactions. This fits the Spiral-Time framework’s shift from a resolution of ordered steps to a distributed field of relations.

Design for re-membering: The second principle addresses temporality and memory. From an agential realist perspective, the history of a system is not a passive data log; the history should be an active part of its current and forthcoming configurations. The principle calls for designing systems whose "past" gets inscribed in their structure and which actively shapes their future organization. Parts cannot be separated from the whole, and their properties are the result of their shared historicity. The role of the designer is to create mechanisms for how a system can re-member by structurally changing its organization, thereby giving rise to a unique reconfiguring development trajectory. This fits the Spiral-Time framework’s computational model of enacting a solution space that becomes actualized through constraint satisfaction, instead of computing the "future" from the "past".

Design for emergent patterns, not specific behavior: The third principle is about the expression and dynamics of a system. In traditional design, system dynamics is based on specified behaviors as predictable causal chains of events. (i.e., "if User does X, the system responds with Y"). Designing for emergent patterns instead means basing the system dynamics on temporal patterns in the overall system. Rather than repetitive predictable transactions, the designer’s goal is a rich scope of recognizable but not strictly repetitive or predictive behavioral patterns. The patterns can be understood as the rhythms of the system, patterns of intra-action that characterize the system’s ongoing "becoming". This fits the Spiral-Time framework’s rejection of a linear causality in favor of an emergent tempoality constructed from internal relational configurations.

9. Complexity Theory Implications

Spiral-time models offer an alternative perspective on computational and structural complexity that moves beyond resource-based measures such as time and space. Traditional complexity theory classifies problems based on how much time or memory is required to solve them using sequential or parallel steps. However, spiral-time models shift the emphasis from execution cost to structural coherence—asking instead how difficult it is to arrive at a globally consistent configuration under constraint propagation. Under this view, the complexity of a process becomes a function of: a) the depth of logical constraint entanglement across layers, b) the dimensionality and coupling among local states, c) the difficulty of achieving a fixed-point representing the strategic distribution .

This paradigm opens up new classifications: problems traditionally considered intractable (e.g., in NP or PSPACE) may admit tractable spiral-time resolutions if the constraint space is navigable through non-causal propagation. Analogous to how models with closed time-like curves (CTCs) reduce complexity class boundaries by resolving problems through self-consistency, spiral-time may offer similar benefits without relying on paradox-prone cyclic structures. In this sense, spiral-time invites a new type of complexity class—perhaps defined by "structural resolution depth" rather than algorithmic time—broadening the landscape of solvability through consistency rather than computation.

10. Case Studies and Applications

10.1. Distributed Consensus under Uncertainty

In asynchronous or partially connected networks such as sensor arrays, peer-to-peer systems, or Internet-of-Things (IoT) environments, achieving consensus is notoriously difficult due to unpredictable message delays, partial failures, and the lack of global clocks. Spiral-time models offer an alternative to time-based synchronization by emphasizing convergence through consistency. Each node in the network can adopt a local strategy or state update rule that depends not on message arrival time, but on satisfying a structural constraint in relation to its neighbors. For example, a consensus variable at node

i might evolve according to:

This constraint propagates through the network until all nodes reach a state consistent with a target distribution e.g. a common ledger view or environmental reading. This approach has practical analogues in conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs) and eventual consistency models, where convergence emerges structurally rather than temporally.

10.2. Spiral-Time Inference in Bayesian Networks

Large-scale probabilistic inference often involves high-dimensional spaces and complex dependency structures, making exact inference computationally infeasible. Spiral-time offers a conceptual and structural model for organizing these dependencies so that marginal distributions emerge from mutual constraint rather than sequential updating.

Each node in a Bayesian network can be treated as a logical layer

, with local consistency functions that encode conditional probabilities. Rather than iteratively sampling or conditioning based on a topological sort, spiral-time frames inference as finding a configuration that jointly satisfies these constraints:

This approach aligns with algorithms such as loopy belief propagation, which iteratively pass messages across cycles until convergence, but does so within a framework that formalizes the structural logic of resolution without requiring message-passing sequences.

10.3. Regulation in Genetic Networks

Gene regulatory networks operate through intricate feedback systems, where the expression of one gene influences and is influenced by many others. Rather than unfolding as a linear genetic script, gene expression is often the result of distributed constraint satisfaction—akin to settling into a spiral-time configuration.

Spiral-time models this as a network of gene states , each governed by biochemical constraints , which must satisfy a global developmental phenotype P*. This framework can be used to study morphogenesis, cell fate determination, and other biological processes that depend on resolving distributed, interdependent interactions into coherent outcomes.

11. Visualization through Strategic Landscapes

Unlike time-sequenced diagrams (e.g., flow charts or DAGs), spiral-time systems are best visualized as strategic resolution landscapes, where each point represents a potential state configuration, and each trajectory corresponds not to a causal path, but to a convergence path toward the target distribution .

One useful metaphor is a multidimensional basin or energy landscape, where valleys represent admissible, stable configurations. The spiral-time dynamic does not roll downhill in time, but rather slides along constraint contours, seeking points where all interdependent variables simultaneously satisfy their mutual constraints.

Graphically, this can be illustrated through layered networks with bidirectional edges encoding logical dependencies, and structural convergence visualized as a tightening spiral toward a core resolution zone. Unlike cycles, no edge loops back. Unlike trees, no node leads unilaterally. Instead, resolution unfolds in an asymmetric, inward trajectory, representing deepening strategic coherence. Such representations help illuminate not how systems behave over time, but how they realize configurations under structure—a key conceptual shift enabled by spiral-time modeling.

This kind of visualization is closely related to how constraint-satisfaction and fixed-point solvers operate. Just as SAT solvers or variational algorithms resolve constraint landscapes without temporal steps, spiral-time depicts structural alignment achieved through compatibility rather than sequential causation. Such representations help illuminate not how systems behave over time, but how they realize configurations under constraint—a key conceptual shift enabled by spiral-time modeling.

While speculative links to agential realism (Barad) offer philosophical richness, we acknowledge the need for greater rigor in mapping concepts such as intra-action and performativity onto the spiral-time framework. Rather than claiming direct equivalence, we interpret Barad’s ontology as offering philosophical resonance with the idea that systems achieve identity and outcome through relational entanglement rather than linear causality. In future work, a more precise ontological mapping may clarify whether spiral-time can serve as a formal complement to Barad’s metaphysics or remains a distinct but thematically aligned construct.

12. Conclusions and Outlook

The spiral-time framework reconceptualizes process not as a linear sequence of causes and effects, but as the convergence of interdependent elements into a strategically coherent whole. This structural model displaces causality from its foundational role and instead privileges global constraint satisfaction as the operative logic. By emphasizing mutual compatibility over temporal ordering, spiral-time opens new conceptual and practical avenues across computation, communication, biological systems, and philosophical analysis.

Unlike conventional models that depend on message order, clocking, or algorithmic steps, spiral-time offers an acausal yet coherent alternative: fixed-point resolution under distributed constraints. Simulation results demonstrate that even when semantic units are transmitted without order, global coherence can be reliably recovered. This suggests that systems governed by relational constraints can be both intelligible and resilient—without relying on linear causality.

Philosophically, this model resonates with agential realism, particularly its ontological claim that time and agency emerge from intra-active configurations. While not a strict formalization of Barad’s metaphysics, spiral-time provides a concrete computational structure to explore non-linear temporal emergence and performative interaction.

Future research should pursue several directions: (a) formalizing complexity classes for constraint-based (rather than time-based) solvability, (b) developing spiral-time analogs of Turing machines, neural networks, or quantum circuits, and (c) investigating hybrid architectures where spiral-time integrates with probabilistic inference or entangled states. In systems where uncertainty, feedback, or non-simultaneity dominate, spiral-time provides a promising model—one that captures coherence not through steps, but through structure.

References

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Turing, A.M. On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1936, s2-42, 230–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, M.; Woltran, S. Answer Set Programming and SAT Solving. In Handbook of Satisfiability; Biere, A.; Heule, M.; van Maaren, H.; Walsh, T., Eds.; IOS Press, 2011; pp. 341–432.

- Aaronson, S. Quantum Computing Since Democritus; Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- van Benthem, J. Logic and the Dynamics of Information. Studia Logica 2001, 67, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgov, A.D.; Novikov, I.D. Superluminal Particles and Causality. Physics Letters B 1998, 442, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, A. Noncausal Structural Explanations and the Sciences. In Causation and Explanation in Science; Woodward, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2024. Preprint.

- Baumeler, Ä.; Wolf, S. Non-causal Computation. Entropy 2017, 19, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barad, K. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning; Duke University Press, 2007.

- de Petris, L.; Khatibi, S. Organizing Relational Complexity—Design of Interactive Complex Systems. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2025, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barad, K. Transmaterialities: Trans*/matter/realities and queer political imaginings. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 2015, 21, 387–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath-Carpentier, A., Ed. The Challenge of Complexity: Essays by Edgar Morin; Liverpool University Press, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).