Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) has various clinical presentations; pulmonary TB (PTB) affects only the lungs, while extra-pulmonary TB is defined as the disease involving any other or-gans, including pleural TB (PLTB). Immunological studies of patients with ex-tra-pulmonary TB mainly focus on the cellular Th1 response, which produce key cyto-kines like IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-12, and IL-6. The TNF-α, and IL-6, which play functional roles in host resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection. Findings suggest that TNF-α facilitates macrophage containment of Mtb; while that IL-6 increases the apoptosis of macrophages induced by Mtb. Studies involving the human genome have helped identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes encoding cytokines associated with TB susceptibility. This study aimed to determine the potential of the IL6-174G/C (rs1800795), TNFα-308G/A (rs1800629) and TNFα -238G/A (rs361525) SNPs as genetic biomarkers of susceptibility to PLTB in the Venezuelan mestizo popu-lation. A total of 269 individuals were included: 69 patients with PLTB and 200 healthy individuals. The IL6-174G/C, TNFα-308G/A and TNFα-238G/A polymorphisms were determined by sequence-specific primer polymerase chain reaction (SSP-PCR). Results showed significantly increased frequencies of the G/C, G/A and G/A genotypes in pa-tients with PLTB (94.0%, 94.2% and 83.3%) compared to controls (40.0%, 19.0% and 13.4%) for the IL6-174G/C, TNFα-308G/A and TNFα-238G/A polymorphisms, respec-tively. Logistic regression analysis showed significant associations of G/C, G/A and G/A genotypes and susceptibility to PLTB. The IL6-174G/C TNFα-308G/A and TNFα-238G/A gene polymorphisms could represent potential genetic biomarkers of susceptibility to PLTB in the Venezuelan mestizo population.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Groups

2.2. Diagnosis of Tuberculous Pleural Effusions and Therapeutic Conduct

2.3. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction and IL-6 and TNF-α Genotyping

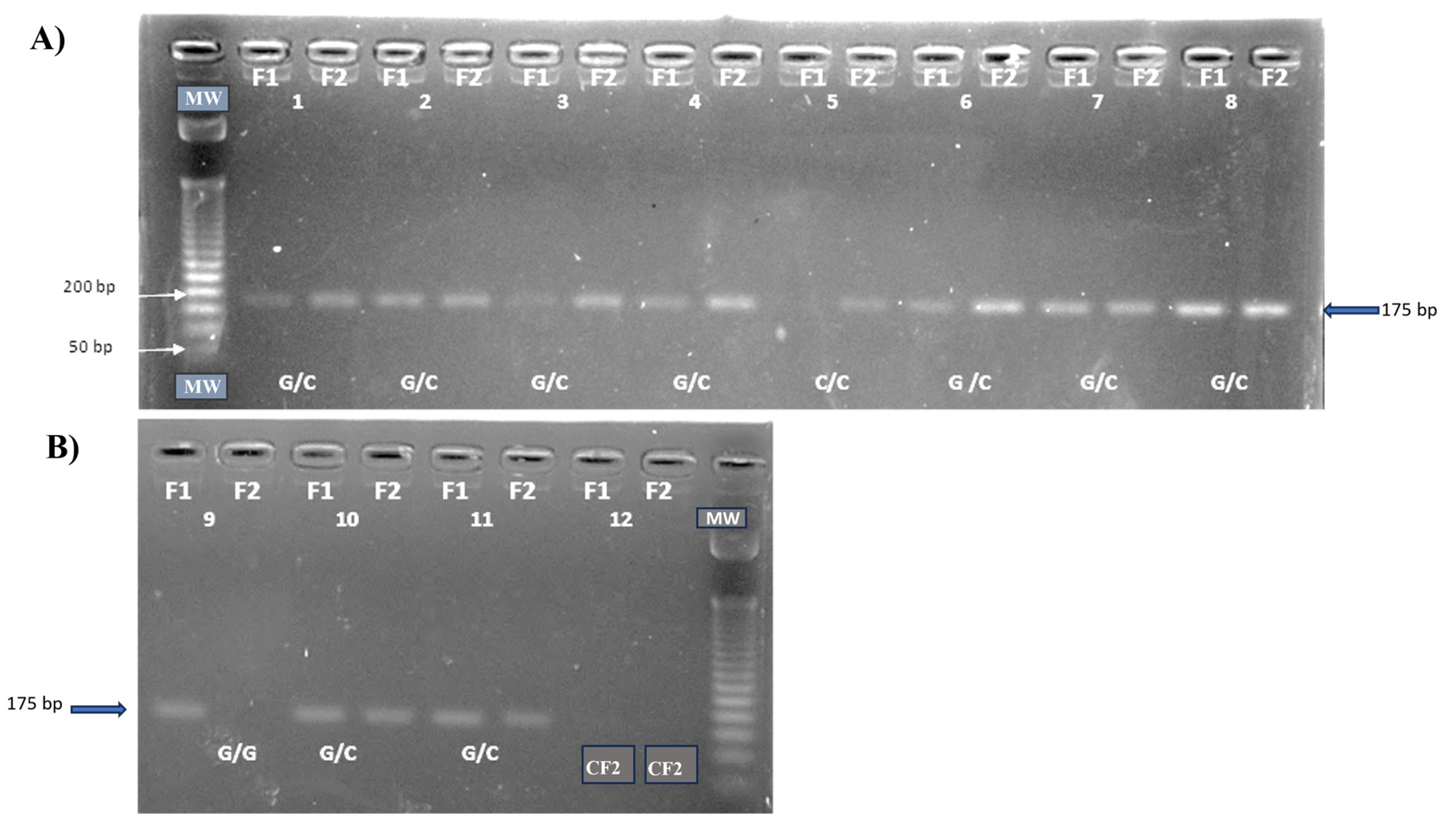

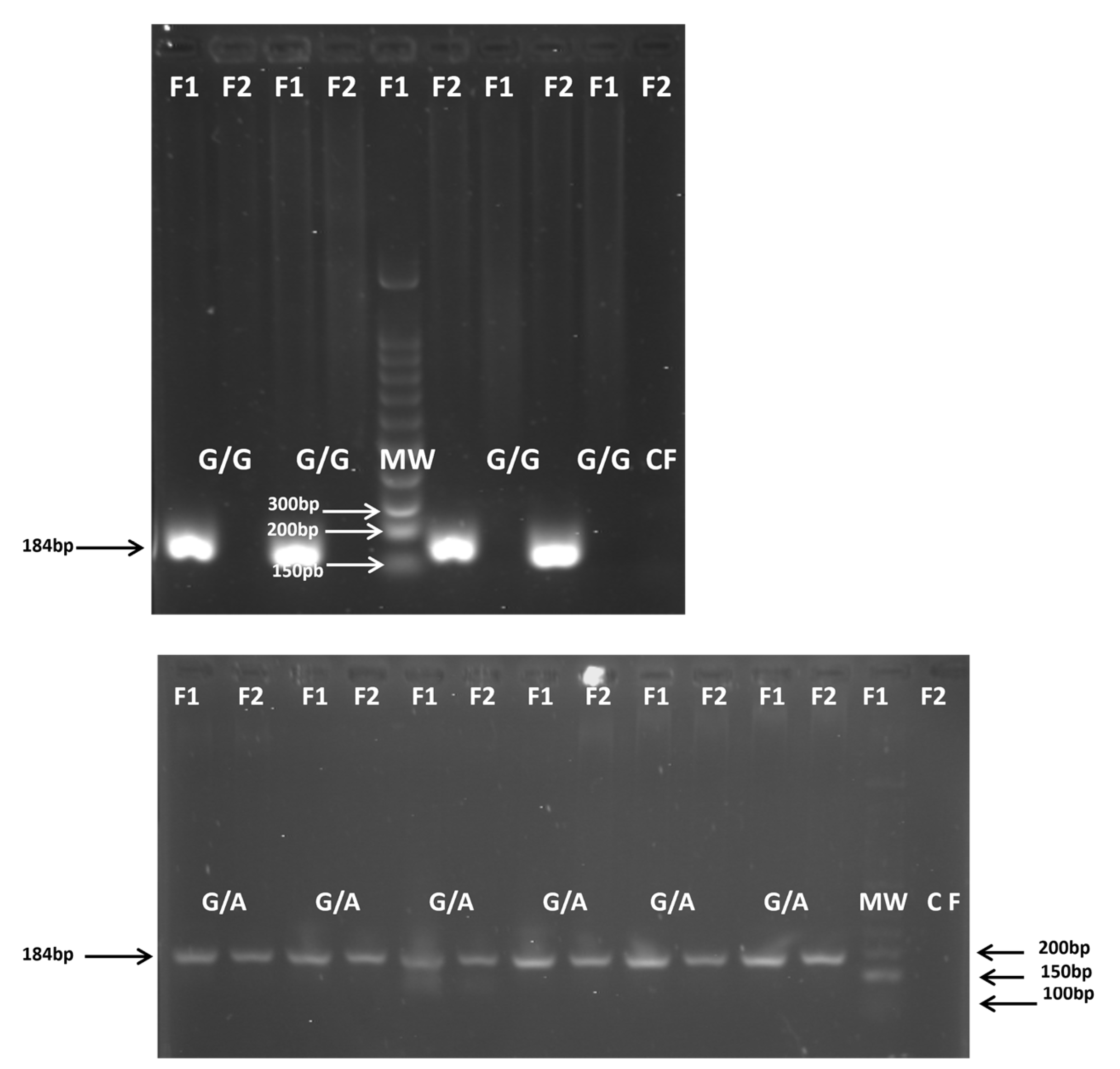

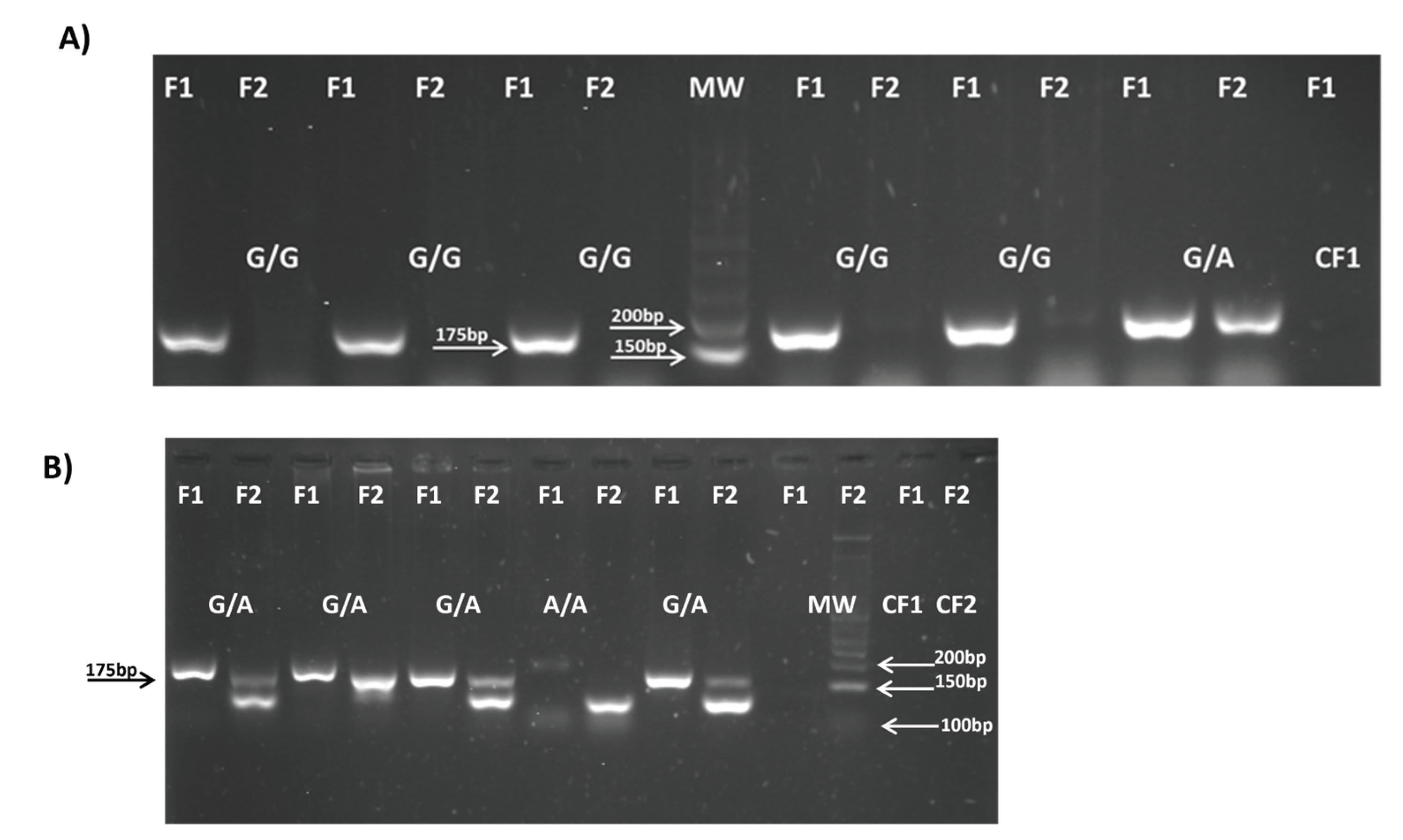

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

3.2. IL6 and TNFα Polymorphisms and Allele Frequencies

3.2. IL6 and TNFα Polymorphism Genotypes and Association with Pleural Tuberculosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. Geneva 2024.

- Castro, V.; Celiz, J. Tuberculosis: Una vieja enfermedad conocida que no deja de sorprendernos. 2017. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35362011/Tuberculosis_Una_Vieja_enfermedad_conocida_que_no_deja_de_sorprendernos.

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Programme. Global tuberculosis report 2023. Geneva 2023. ISBN 978-92-4-008385.

- MacNeil, A.; Glaziou, P.; Sismanidis, C.; Date, A.; Maloney, S.; Floyd, K. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis and progress toward meeting global targets — worldwide, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 69, 281−285.

- Porcel, J.M. Tuberculous Pleural Effusion. Lung. 2009, 187, 263–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.C.; Feller-Kopman, D.; Niederman, M.S.; Spiro, S.G. Year in review 2010: Tuberculosis, pleural diseases, respiratory infections. Respirology, 2011. 16, 564–573.

- Barssa, L.; Connors, W.J.A.; Fisher, D. Chapter 7: Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. Canadian J. Resp. Critical Care Sleep Med. 2022, 6, 87−108. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, M.; Prakash-Nayak, O.; Murmu, M.; Ranjan-Partra, S.; Baa, M. Role of CBNAAT in Suspected Cases of Tubercular Pleural Effusion. J. Dental Medical Sci. 2019, 18, 46–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro L, San Jose E, Valdes L. Tuberculous pleural effusion. Arch. Bronco neumol. 2014, 50, 435e43. [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Hu YJ, Li FG, Chang XJ, Zhang TH, Wang ZT. Analysis of cytokine levers in pleural effusions of tuberculous pleurisy and tuberculous empyema. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 3068103.

- Antas, P.; Borchert, J.; Ponte, C.; Lima, J.; Georg, I.; Bastos, M.; Trajman, A. Interleukin-6 and-27 as potential novel biomarkers for human pleural tuberculosis regardless of the immunological status. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, F. , Schurz, H. , ates, T.A., Gilchrist, J.J., Möller, M., Naranbhai, V., Ghazal, P., Timpson, N.J., Tom Parks, T., Pollara. G. Altered IL-6 signalling and risk of tuberculosis: a multi-ancestry mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 100922. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, V.P.; Scanga, C.A.; Yu, K.; Scott, H.M. ; Tanaka, K,E. ; Tsangm E.; Chih, T.M.; Flynn, J.L.; John, C.J. Effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha on host immune response in chronic persistent tuberculosis: possible role for limiting pathology. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 1847−1855. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Adrian, T.B.; Leal-Montiel, J.; Fernández, G.; Valecillo, A. Role of cytokines and others factors involved in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. World J. Immunol. 2015, 5, 16−50. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj, P.; Alagarasu, K.; Harishankar, M.; Vidyarani, M.; Nisha-Rajeswari, D. ; Narayanan. P.R. Cytokine gene polymorphisms and cytokine levels in pulmonary tuberculosis. Cytokine. 2008, 43, 26−33. [Google Scholar]

- Henao, M.I.; Montes, C.; París, S.C.; García, L.F. Cytokine gene polymorphisms in Colombian patients with different clinical presentations of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2006, 86, 11−19. [Google Scholar]

- Ates, Ö.; Musellim, B.; Ongen, G.; Topal-Sarıkaya, A. IL-10 and TNF Polymorphisms in tuberculosis. J. Clin. Immunol. 2008, 28, 232−236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varahram, M.; Farnia, P.; Javad-Nasir, M.; Afraei-Karahrudi, M.; Kazempour-Dizag, M.; Akbar-Velayati, A. Association of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Lineages with IFN-γ and TNF-α Gene Polymorphisms among Pulmonary Tuberculosis Patient. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 6, e2014015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalilullah, S.A.; Harapan, H.; Hasan, N.A.; Winardi, W.; Ichsan, I.; Mulyadi, M. Host genome polymorphisms and tuberculosis infection: What we have to say? . Egypt J. Chest Dis. Tuberc. 2013, 63, 173−185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández de Larrea, C.; Giampietro, F.; Luna, J.; Singh, M.; de Waard, J.H.; Araujo, Z. Diagnosis accuracy of immunological methods in patients with tuberculous pleural effusion from Venezuela. Inves. Clin. 2011, 52, 23−34. [Google Scholar]

- MPPS (Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Salud de Venezuela), 2016. Available online: http://www.minsalud.com.

- Ambruzova, Z. , Mrazek, F. , Raida, L., Jindra, P., Vidan-Jeras, B., Faber, E., Pretnar, J., Indrak, K., Petrek, M. Association of IL6 and CCL2 gene polymorphisms with the outcome of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009, 44, 227−235. [Google Scholar]

- Verjans, G.M.; Brinkman, B.M.N.; Van Doornik, C.E.M.; Kijlstra, A.; Verweij, C.L. Polymorphism of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) at position -308 in relation to ankylosing spondylitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1994, 97, 45−47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhaes, R.F.; Ana Cristina Biral, A.C.; Pancoto, J.A.T.; Donadi, E.A.; Texeira Mendes-Júnior, C. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha -238 and -308 as genetic markers of susceptibility to psoriasis and severity of the disease in a long-term follow-up Brazilian study. 2010. Available online. [CrossRef]

- Sole, X.; Guino, E.; Valls, J.; Iniesta, R.; Moreno, V. SNPStats: a web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics. 2006, 22, 1928−1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Sun, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H. Advances in cytokine gene polymorphisms in tuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. 2025, 10, e0094424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriba, T.J.; Coussens, A.K.; Fletcher, H.A. Human Immunology of Tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, TBTB2–0016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas Santiago B, Vieyra Reyes P, Araujo Z. Respuesta de inmunidad celular en la tuberculosis pulmonar: Invest. Clín. 2005, 46, 391–412.

- Araujo Z, Acosta M, Escobar H, Baños R, Fernández de Larrea C, Rivas Santiago B. Respuesta inmunitaria en tuberculosis y el papel de los antígenos de secreción de Mycobacterium tuberculosis en la protección, patología y diagnóstico: Revisión. Invest Clin. 2008, 49, 411–441.

- Huang W, Zhou R, Li J, Wang J, Xiao H. Association of the TNF-α-308, TNF-α-238 gene polymorphisms with risk of bone-joint and spinal tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 2019; 39, BSR20182217.

- Liu, Q.; Chen, X.; Dai, X. The association of cytokine gene polymorphisms with tuberculosis susceptibility in several regional populations. Cytokine. 2022, 156, 155915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhatadze, N.J. , Franco, M. T., Layrisse, Z. HLA class I and class II allele and haplotype distribution in the Venezuelan population, Hum. Immunol. 1997, 55, 53−58. [Google Scholar]

- Graça-Amoras, E.S.; Gouvea-de Morais, T.; do Nascimento-Ferreira, R.; Monteiro-Gomes, S.T.; Martins-de Sousa, F.D.; Rosário-Vallinoto, A.C.; Freitas-Queiroz, M.A. Association of Cytokine Gene Polymorphisms and Their Impact on Active and Latent Tuberculosis in Brazil’s Amazon Region. Biomolecules. 2023, 13, 1541. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Luiz, R.D.S.; Alves-Campelo, T.; Soares-Silva, C.; de Lima-Nogueira, L.; de Oliveira- Sancho, S.; Alves-da Silva, A.K.; Cunha-Frota, C.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-beta in pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the State of Ceará, northeastern Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2025, 120, e240147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa P, Gómez L, Anaya J. Polimorfismo del TNF- alfa en autoinmunidad y tuberculosis. 2004, 24, 43–51.

- Correa P, Gómez L, Cadena J, Anaya J. Autoimmunity and tuberculosis. Opposite association with TNF polymorphism. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32, 219–224.

- Casas LA, Gómez Gutiérrez A. Asociación de polimorfismos genéticos de FNT-a e IL-10, citocinas reguladoras de la respuesta inmune, en enfermedades infecciosas, alérgicas y autoinmunes. Infection. 2008, 12, 38–53.

- Ramirez, M.C.D. Bases genéticas de la susceptibilidad a enfermedades infecciosas humanas. Rev. Inst. Nac. Hyg. Rafael Rangel. INHRR. 2007, 38, 1−16. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, Z.; Camargo, M.; Moreno-Pérez, D.A.; Wide, A.; Pacheco, D.; Díaz-Arévalo, D.; Celis- Giraldo, C.T.; Salas, S.; de Waard, J.H.; Patarroyo, M.A. Differential NRAMP1gene’s D543N genotype frequency: Increased risk of contracting tuberculosis among Venezuelan populations. Hum. Immunol. 2023, 84, 484−491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampietro, F.; de Waard, J.H.; Rivas-Santiago, B.; Enciso-Moreno, J.A; Salgado, A.; Araujo, Z. In vitro levels of cytokines in response to purified protein derivative (PPD) antigen in a population with high prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis. Hum. Immunol. 2010, 71, 1099−1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, Z.; Palacios, A. ; Enciso-Moreno, L,; Lopez-Ramos, J. E.; Wide, A.; de Waard, J.H., Rivas-Santiago, B.; Serrano, C.J; Bastian-Hernandez, Y.; Castañeda-Delgado, J.E,; et al. Evaluation of the transcriptional immune biomarkers in peripheral blood from Warao indigenous associate with the infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Rev. Soc. Brasileira Med. Trop. 2019, 52, e20180516. [Google Scholar]

| Polymorphism | Primer 5′—3′ | Amplicon Size (bp) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

IL6-174G/C (rs1800795) |

F1:5′AAT GTG ACG TCC TTT AGC ATC-3′ F2:5′-AAT GTG ACG TCC TTT AGC ATG-3′ R:5′-TCG TGC ATG ACT TCA GCT TTA-3′ |

175 (G) 175 (C) |

(Ambruzova et al., 2008) [22] |

|

TNFα-308G/A (rs1800629) |

F1:5′-ATAGGTTTTGAGGGGCATGG-3′ F2:5′-ATAGGTTTTGAGGGGCATGA-3′ R:5′-TCTCGGTTTCTTCTCCATCG-3′ |

184 (G) 184 (A) |

(Verjans GM et al., 1994) [23] |

|

TNFα-238G/A (rs361525) |

F1:5′- CCCCATCCTCCCTGCTCC -3′ F2: 5′- TCCCCATCCTCCCTGCTCT -3′ R:5′-AGGCAATAGGTTTTGAGGGCCAT -3′ |

175 (G) 175 (A) |

(Magalhaes R et al., 2010) [24] |

|

Marker |

Patients (n=69) |

Controls (n=200) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.6±20,0 | 47.6±12,2 | NS |

| Male (%) | 62.3(a) | 37.5(c) | (a) vs (b)0.001 |

| Female (%) | 37,7(b) | 62.5(d) | (c) vs (d)0.0007 |

| ADA+ ˃ 40u/l (%) | 66.6 | 0 | 0.0001 |

|

PPD+ (%) Chest X-rays (CXRs) (%) |

ND 100.0 |

35.0 ND |

- - |

|

Allele Frequency |

Patients Controls (%) (%) |

Odds Ratio OR (95% IC) |

X2 Test (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

IL-6(-174G/C) (rs1800795) G C |

69(50.0)(a) 318(80.0)(b) 69(50.0)(c) 82(20.0)(d) |

0.250(0.133-0.468) 4.000(2.135-7.493) |

(a) vs (b) 0.0001 (c) vs (d) 0.0001 |

|

TNFα(-308G/A) (rs1800629) G A |

73(53.0)(a) 334(88.4)(b) 65(47.1)(c) 44(11.6)(d) |

0.153(0.074-0.315) 6.503(3.166-13.359) |

(a) vs (b) 0.0001 (c) vs (d) 0.0001 |

|

TNFα(-238G/A) (rs361525) G A |

70(58.3)(a) 124(90.0)(b) 50(41.7)(c) 14(10.1)(d) |

0.153(0.071-0.329) 6.517(3.034-14.002) |

(a) vs (b) 0.0001 (c) vs (d) 0.0001 |

| Patients | Controls | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Polymorphism/ Genotype |

n | % | n | % | OR† | 95%CI | p-value | ||||||||

|

IL6(-174 G/C) (rs1800795) |

|||||||||||||||

| G/G (W) | 2 | 2.90 | 119 | 59.5 | Reference | ||||||||||

| G/C (He) | 65 | 94.02 | 80 | 40.0 | 48.343 | 11.507–203.095 | 0.0001 | ||||||||

| C/C (Ho) | 2 | 2.90 | 1 | 0.5 | 119.000 | 7.399 -1913.710 | 0.0007 | ||||||||

|

TNFα(-308G/A) (rs1800629) |

TNFα(-308G/A) (rs1800629) |

||||||||||||||

|

TNFα(-308G/A) (rs1800629) |

|||||||||||||||

| G/G (W) | 4 | 5.80 | 149 | 78.84 | Reference | ||||||||||

| G/A (He) | 65 | 94.20 | 36 | 19.05 | 67.256 | 22.993–196.729 | 0.0001 | ||||||||

| A/A (Ho) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.11 | 3.691 | 0.171–79.407 | 0.4042 | ||||||||

|

TNFα(238-G/A) (rs361525) |

TNFα(238-G/A) (rs361525) |

||||||||||||||

|

TNFα(238-G/A) (rs361525) |

|||||||||||||||

| G/G (W) | 10 | 16.67 | 56 | 81.16 | Reference | ||||||||||

| G/A (He) | 50 | 83.33 | 12 | 13.40 | 23.333 | 9.282–58.655 | 0.0001 | ||||||||

| A/A (Ho) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.44 | 1.793 | 0.068- 47.086 | 0.7260 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).