Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

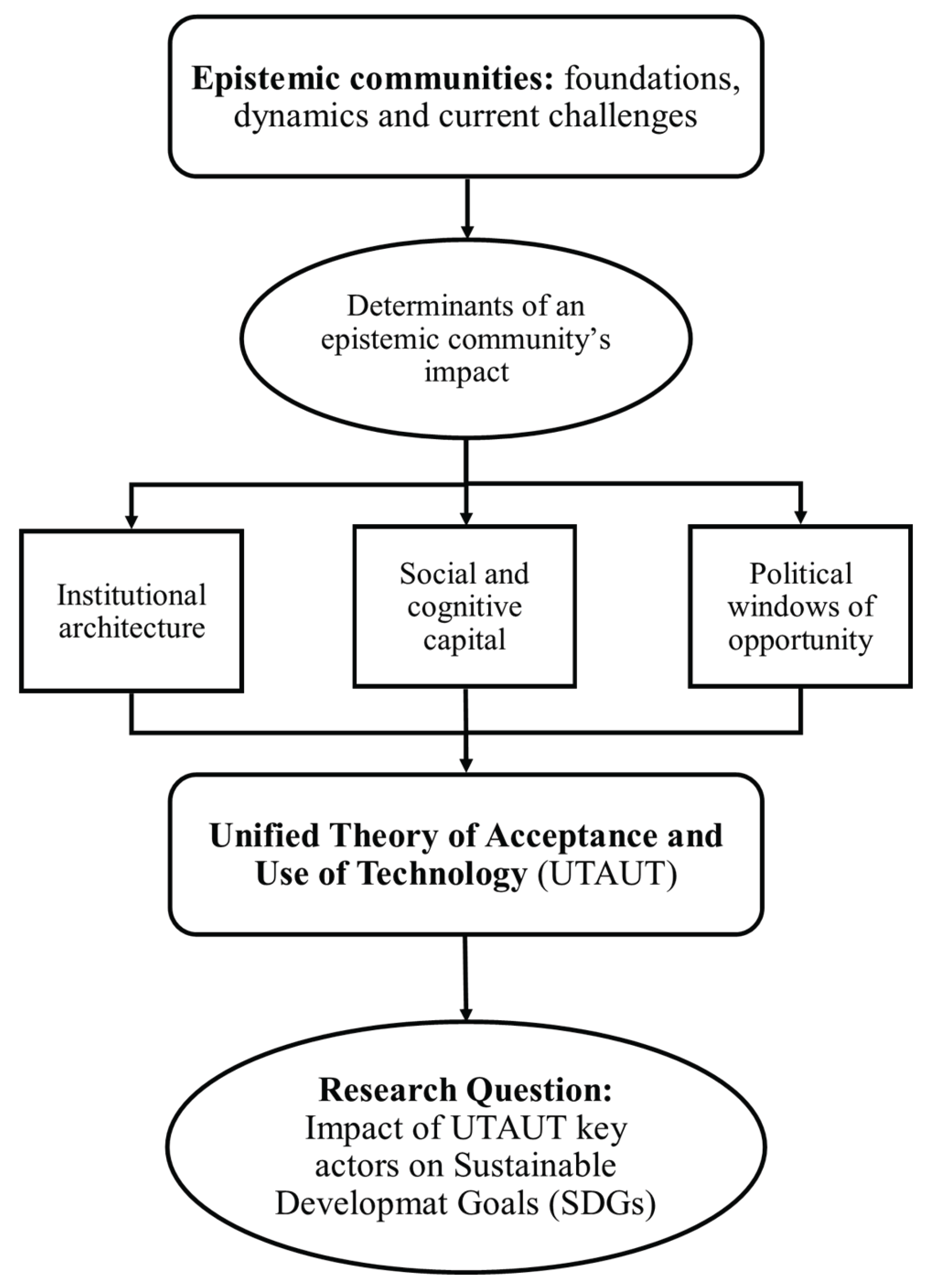

1.1. Epistemic Communities: Foundations, Dynamics and Current Challenges

1.2. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology

2. Methods

2.1. Information Collection

- Document type: scientific articles (Document Type: Article)

- Publication period: between 2003 and 2025, considering that the UTAUT theory was proposed in 2003.

- Language: no restriction, although a predominance of publications in English was observed

- Subject coverage: all subject categories available in the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC) database.

2.2. Applied Analysis Techniques

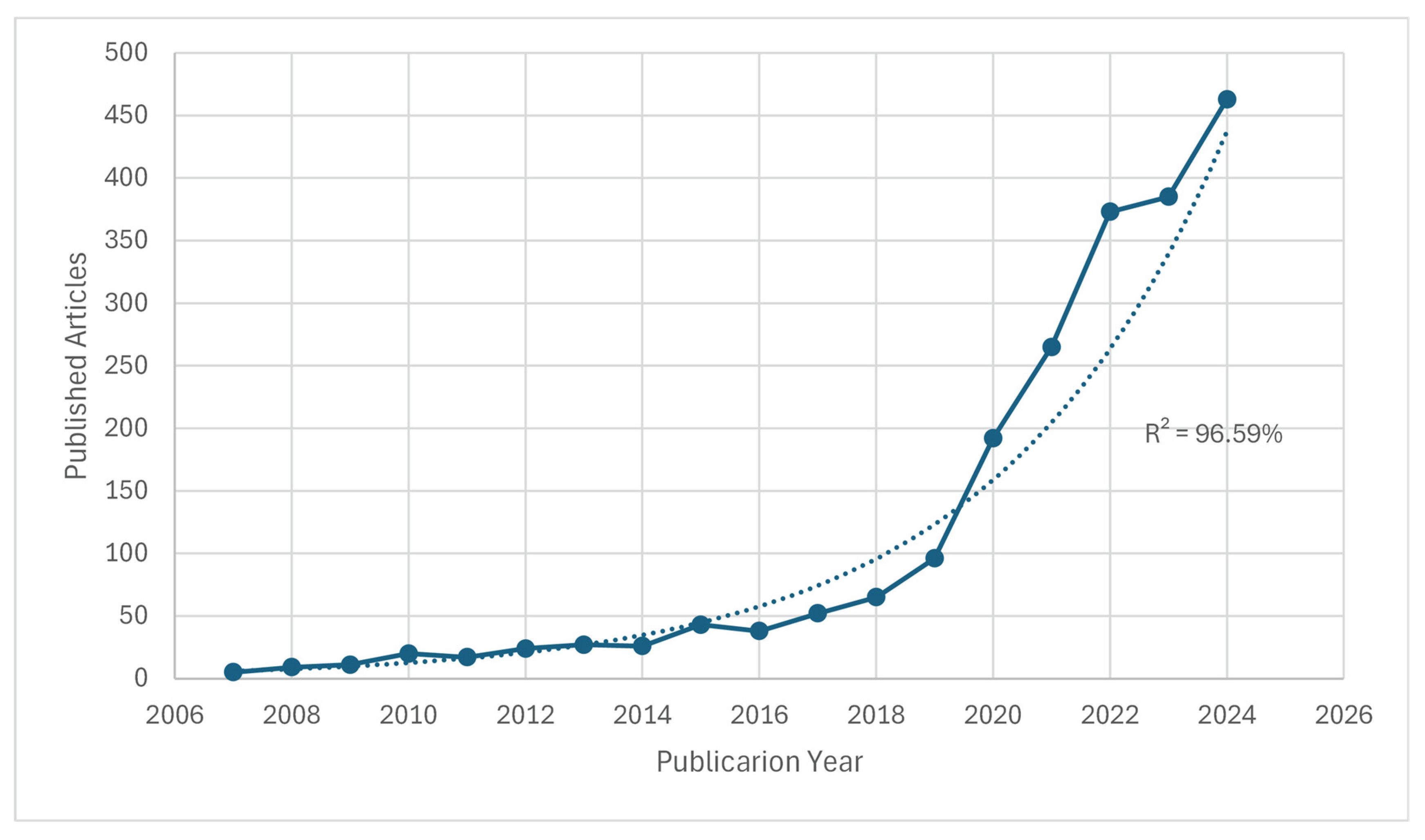

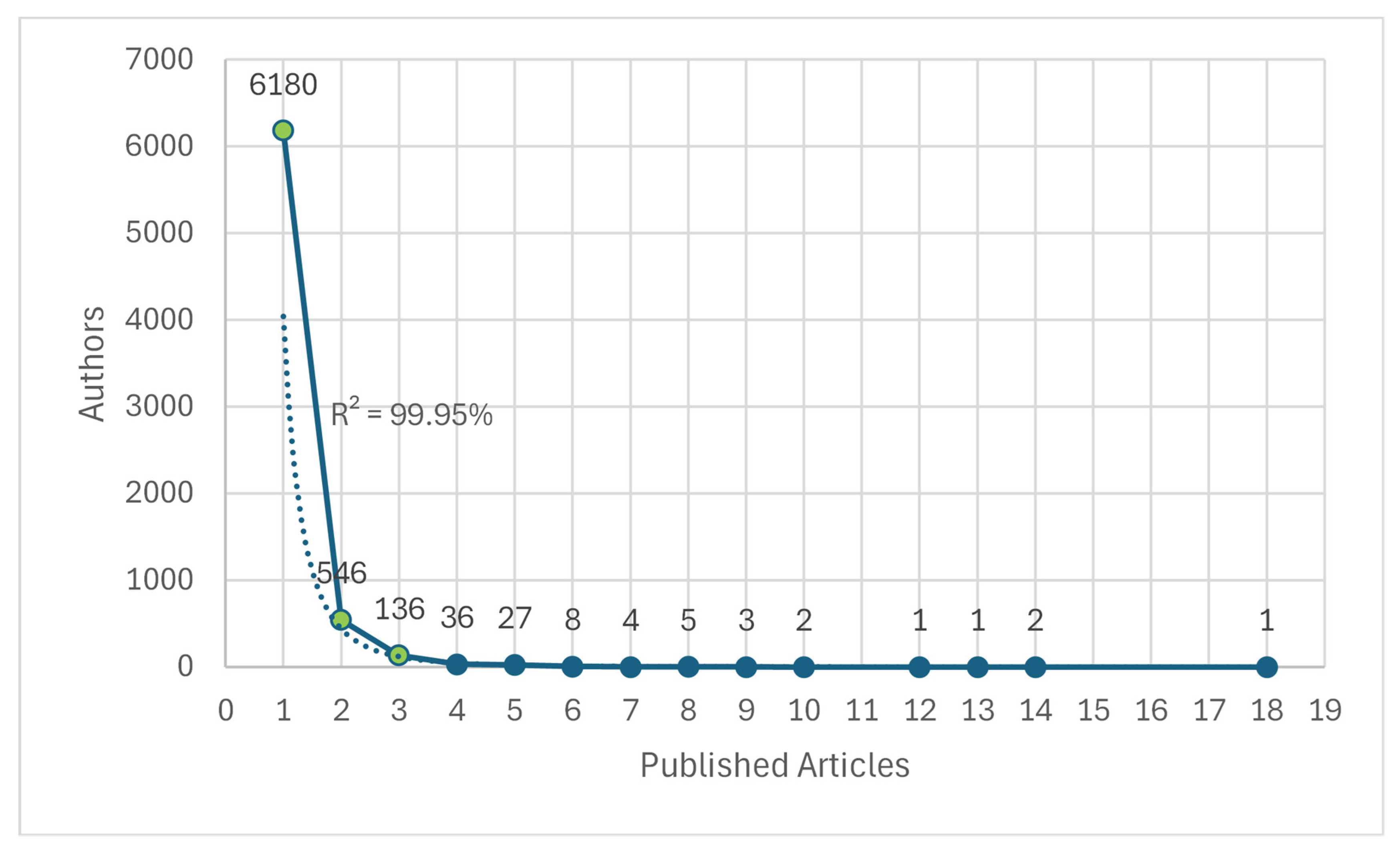

2.2.1. Scientific Productivity

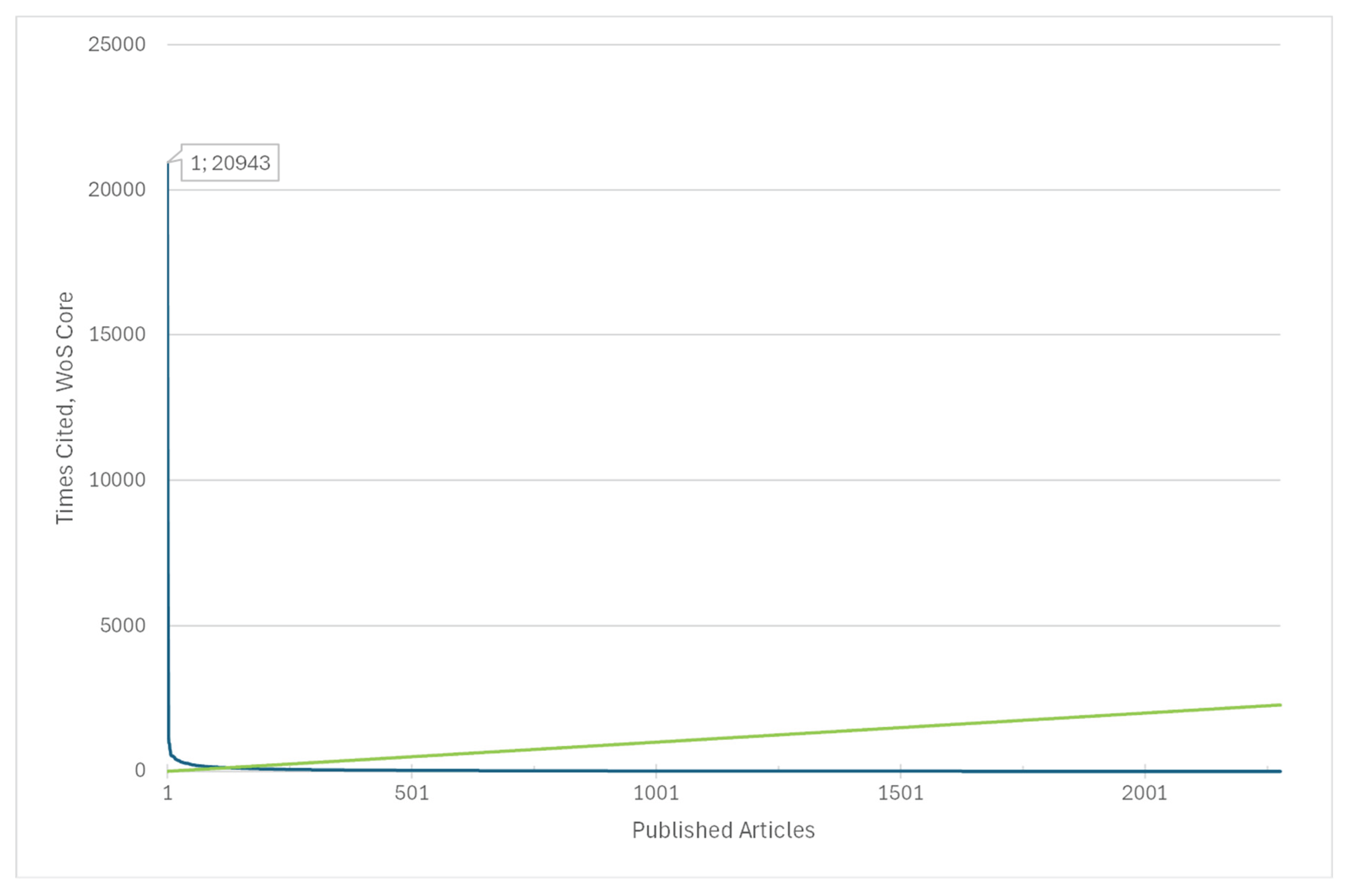

2.2.2. Academic Impact

2.2.3. Relationships and Scientific Networks

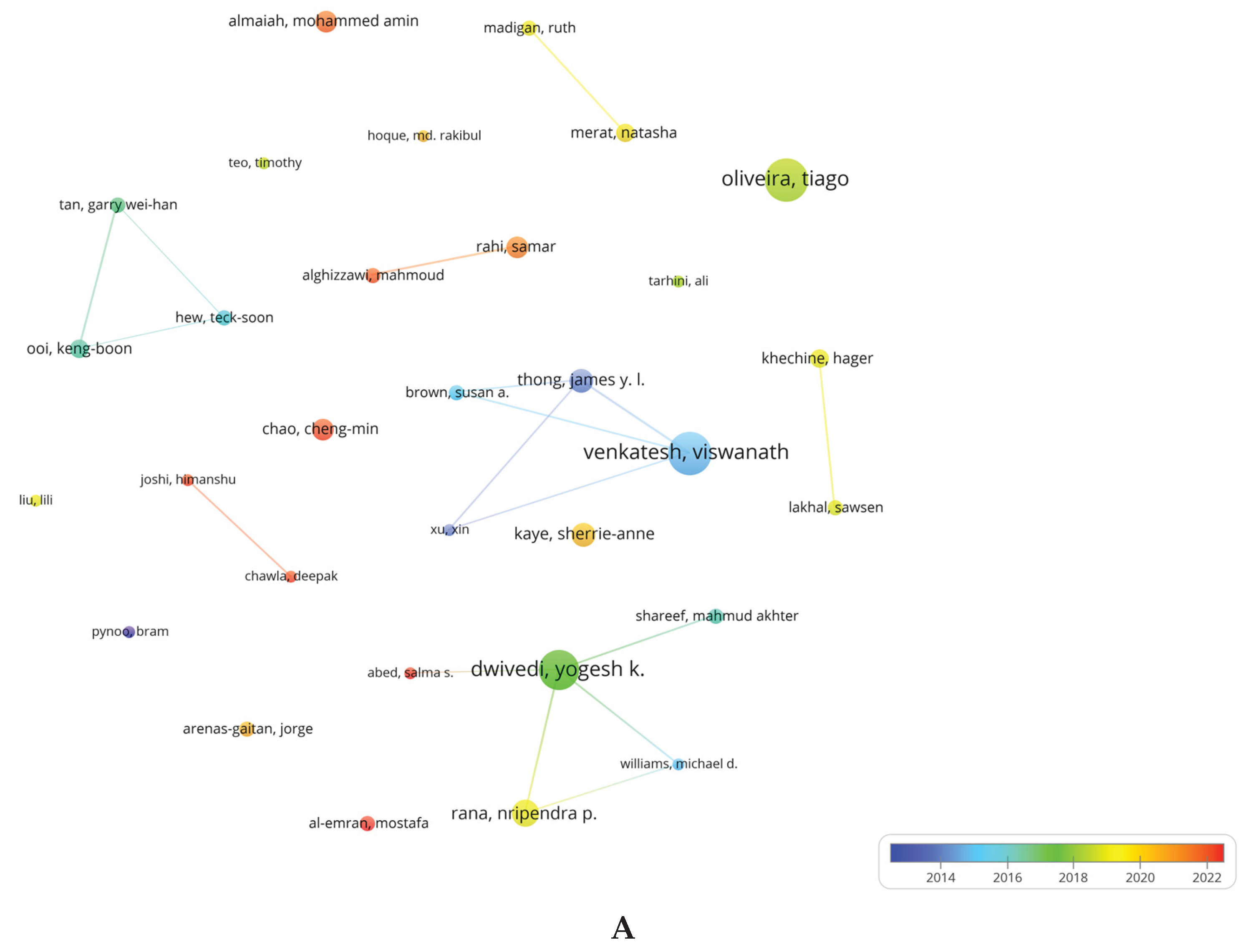

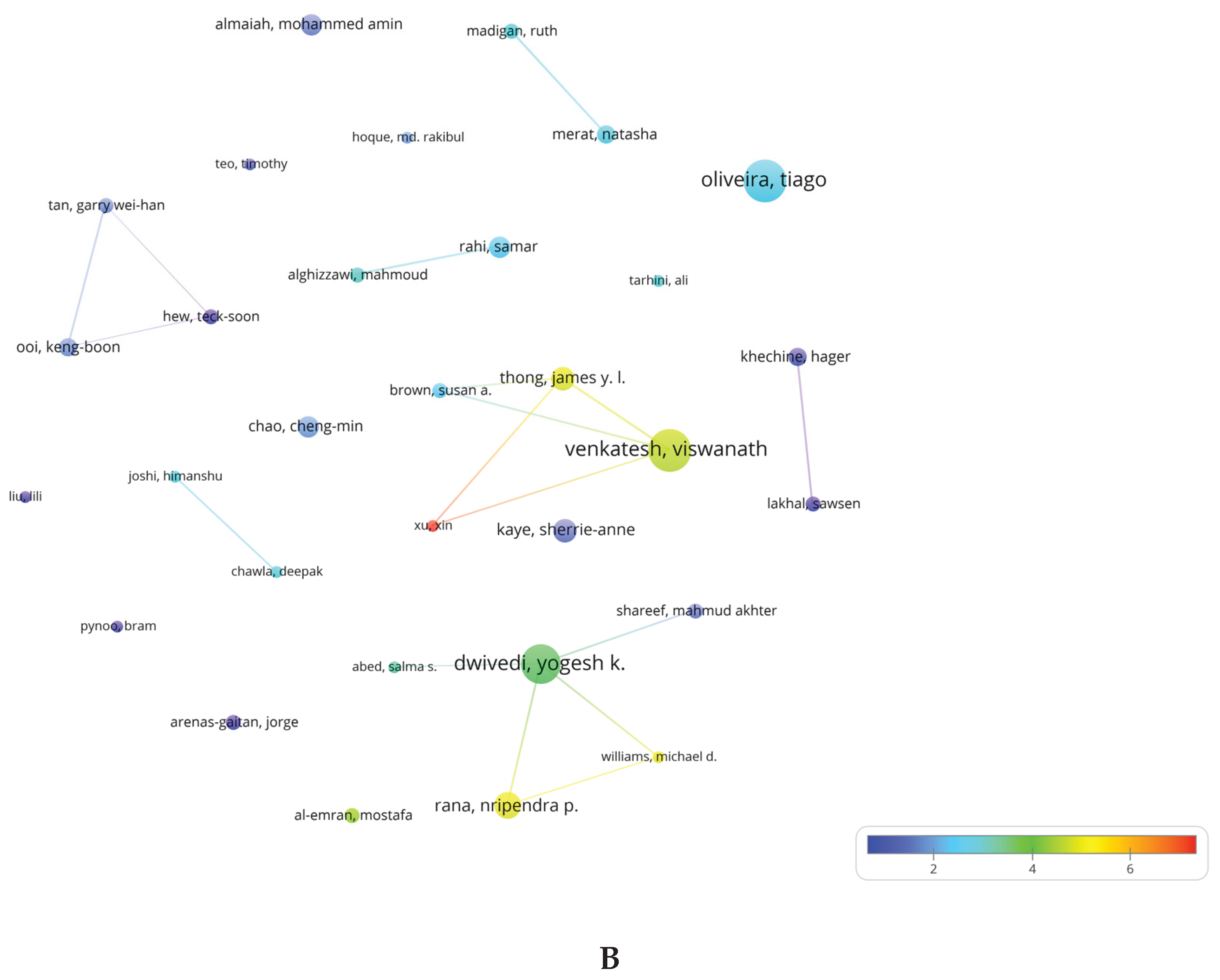

- Co-authorship networks: to identify collaborations between researchers and institutions.

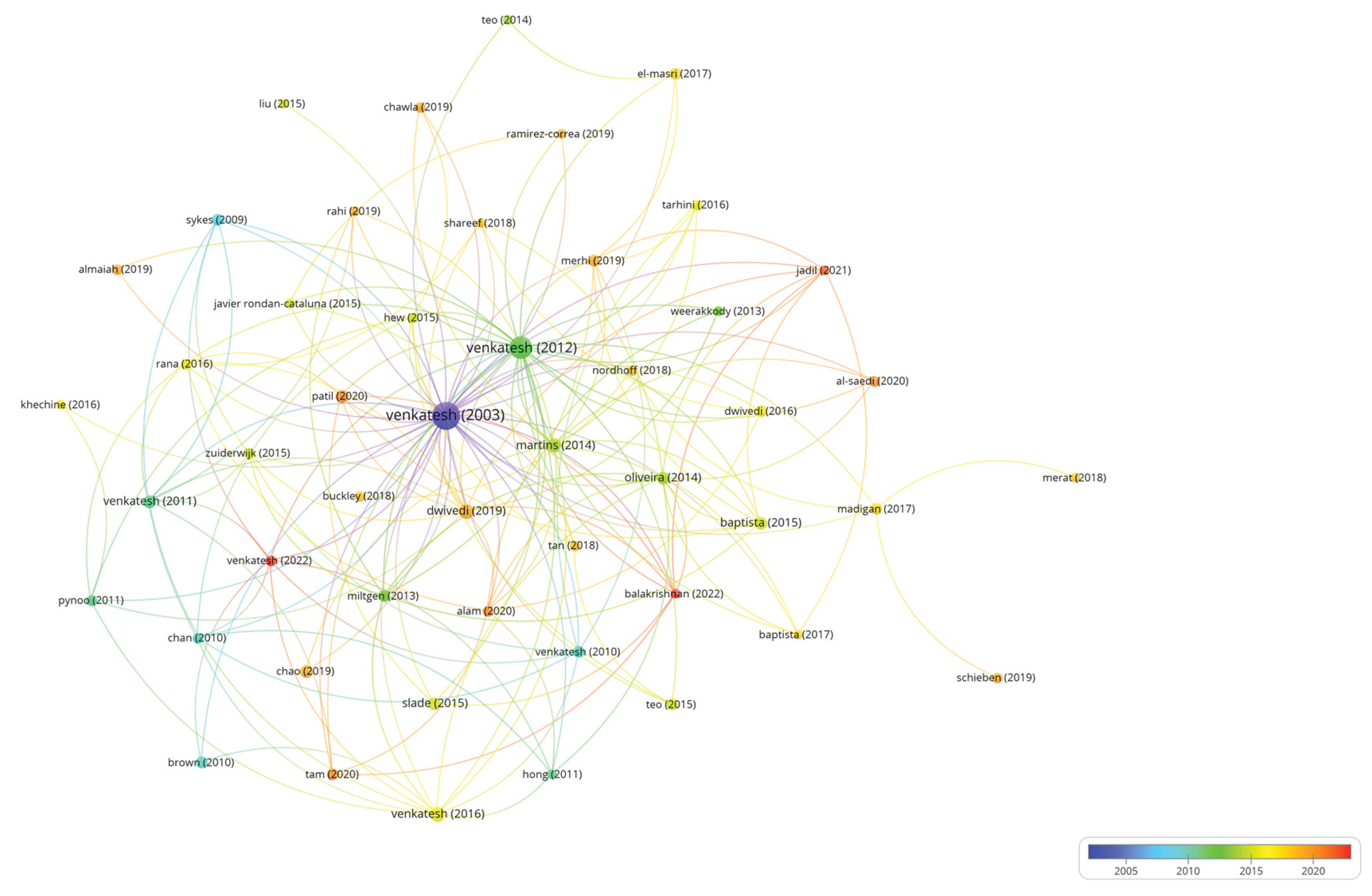

- Cross-citation networks: to detect chains of causal knowledge generation between articles, based on the number of times they cite each other [58].

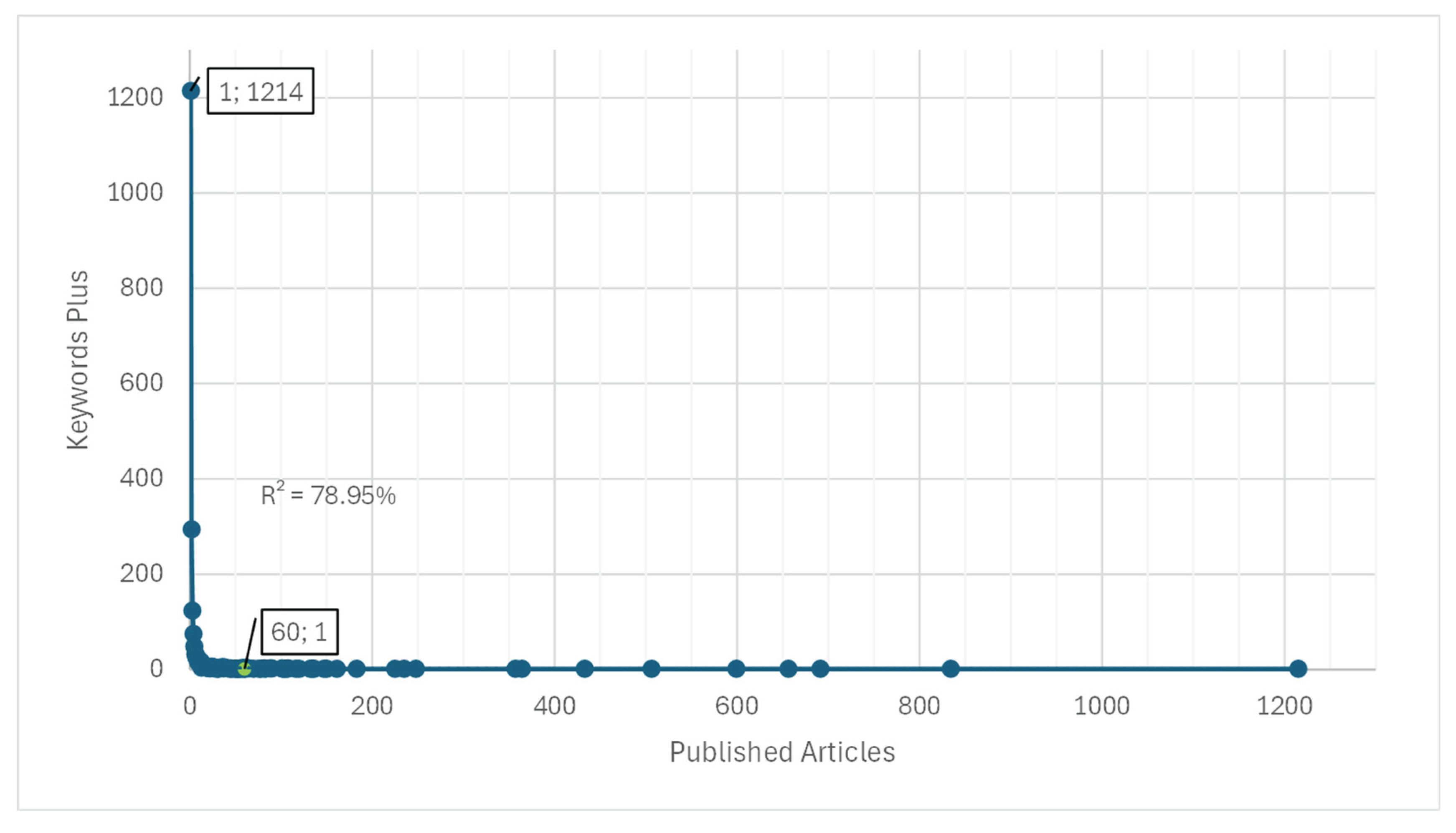

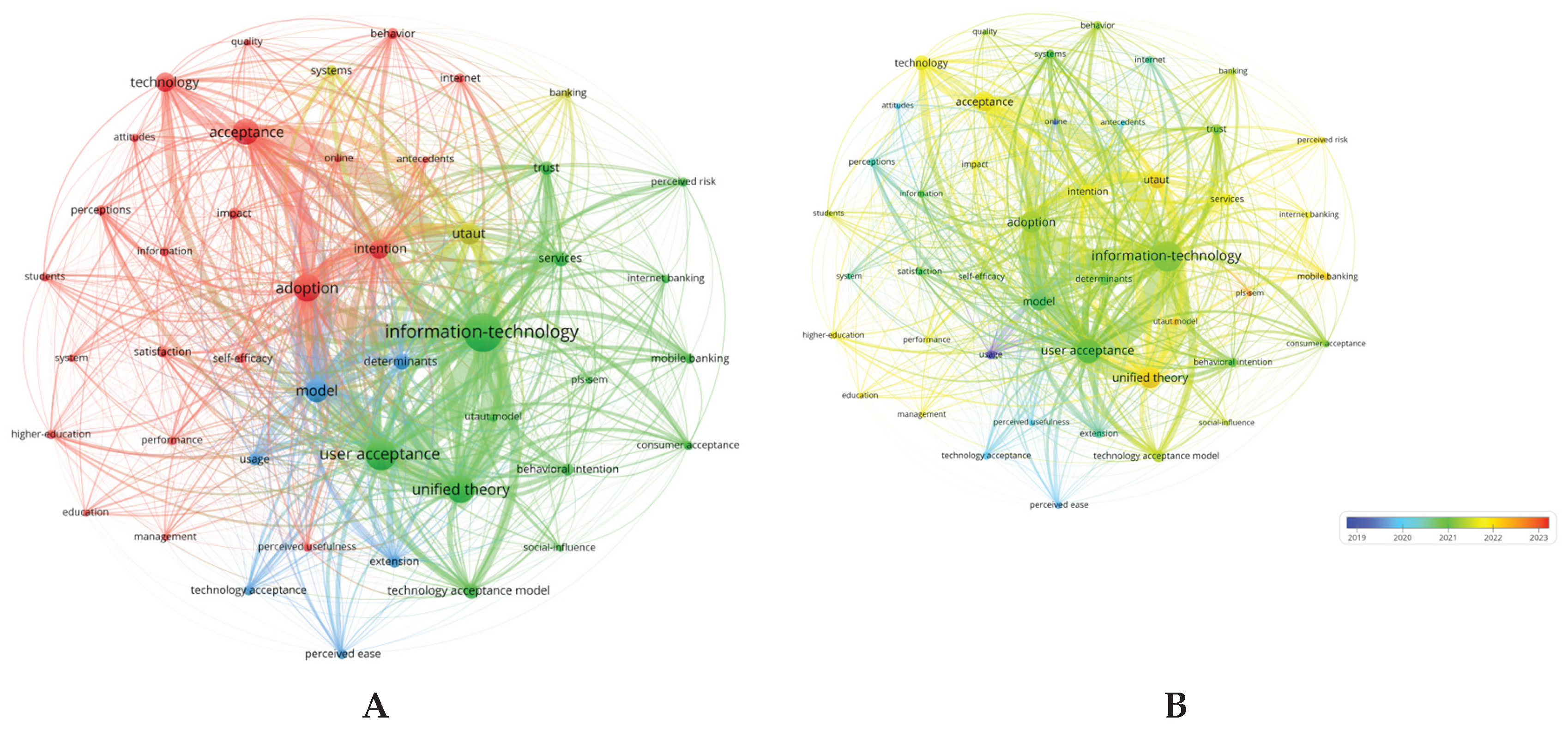

- Keyword co-occurrence: to understand the thematic organization of the field and its evolution over time [59].

2.3. Visualization of Information

2.4. Study Limitations

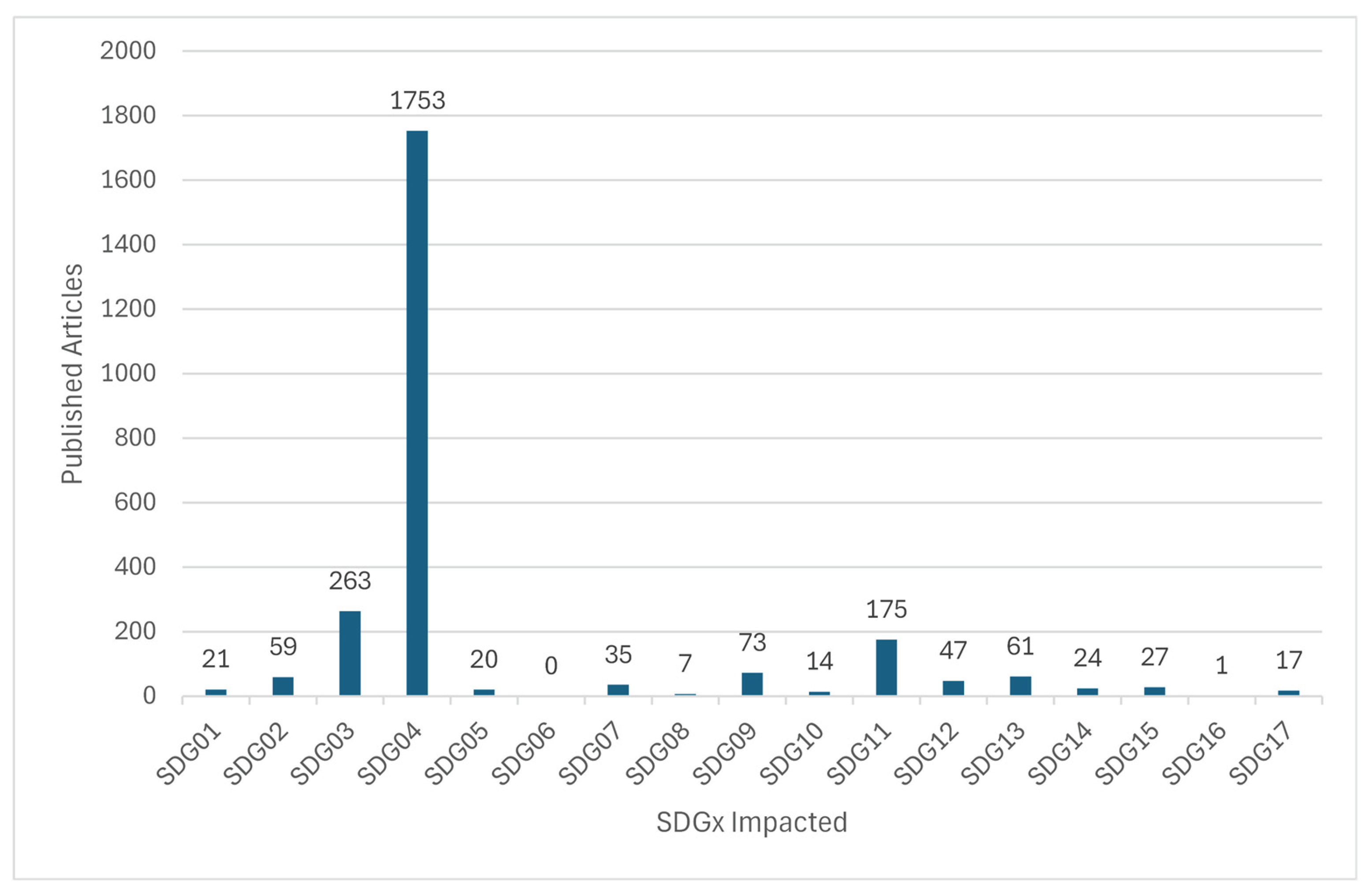

| Variable | Value (or Sample, n) | Unit | Subsampling criterion |

| Time | 2003-2025 | Year | Period without blanks, Price’s Law |

| Authors | 6952 | Person | Lotka’s Law |

| Documents | 2278 | Article | Hirsch’s index (h-index) |

| Keywords Plus | 2064 | Words | Zipf’s Law |

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Haas, P.M. Introduction: Epistemic communities and international policy coordination. Int. Organ. 1992, 46, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, C. The Possible Experts: How Epistemic Communities Negotiate Barriers to Knowledge Use in Ecosystems Services Policy. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 208–228. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.; Guston, D. Procedural control of the bureaucracy, peer review, and epistemic drift. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2007, 17, 535–551. [CrossRef]

- Gunn, H.K. How Should We Build Epistemic Community? J. Specul. Philos. 2020, 34, 561–581. [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.; Fox, C. The Epistemic Community. Adm. Soc. 2001, 32, 668–685. [CrossRef]

- Mabon, L.; Shih, W.Y.; Kondo, K.; Kanekiyo, H.; Hayabuchi, Y. What is the role of epistemic communities in shaping local environmental policy? Managing environmental change through planning and greenspace in Fukuoka City, Japan. Geoforum 2019, 104, 158–169. [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, M.; Yachin, E. From expert to epistemic communities: On the transformation of institutional frames of power in the modern world. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2014, 5, 649–657. [CrossRef]

- Maliniak, D.; Parajon, E.; Powers, R. Epistemic Communities and Public Support for the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Political Res. Q. 2020, 74, 866-881. [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Leydesdorff, L. Scientometrics in a changing research landscape: Bibliometrics has become an integral part of research quality evaluation and has been changing the practice of research. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 1228–1232. [CrossRef]

- Gläser, J.; Laudel, G. The social construction of bibliometric evaluations. In The Changing Governance of the Sciences; Whitley, R., Gläser, J., Eds.; Sociology of the Sciences Yearbook, Volume 26; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 69–93. [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [CrossRef]

- Waltman, L. A review of the literature on citation impact indicators. J. Informetr. 2016, 10, 365–391. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M. G.; Davis, G. B.; Davis, F. D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison--Wesley, Reading, MA, USA, 1975. Available online: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/f&a1975.html. (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control. SSSP Springer Series in Social Psychology: Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer Nature Link, Heidelberg, Germany, 1985, pp. 11-39. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D.; Bagozzi, R. P.; Warshaw, P. R. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R. L.; Higgins, C. A.; Howell, J. M. Personal computing: Toward a conceptual model of utilization. MIS Q. 1991, 15, 125–143. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of innovations, 3rd ed.; The Free Press: New York, USA, 1983. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203887011-36/diffusion-innovations-everett-rogers-arvind-singhal-margaret-quinlan. (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Bandura, A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359–373. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Assessing IT usage: The role of prior experience. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 561–570. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.; Rana, N.; Jeyaraj, A.; Clement, M.; Williams, M. Re-examining the UTAUT: Towards a revised theoretical model. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 19, 719–734. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J. Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending UTAUT. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [CrossRef]

- Ben Arfi, W.; et al. Technological innovations to ensure confidence in IoT healthcare adoption. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 167, 120688. [CrossRef]

- Cimperman, M.; Brenčič, M. M.; Trkman, P. Analyzing older users’ telehealth acceptance—extended UTAUT. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 90, 22–31. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Quaresma, R.; Rahman, H. Factors influencing physicians’ EHR adoption in Bangladesh. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 76–87. [CrossRef]

- Brzan, P.P.; Rotman, E.; Pajnkihar, M.; Klanjsek, P. Mobile apps for diabetes self-management: systematic review. J. Med. Syst. 2016, 40, 210. [CrossRef]

- Zahedul Alam, S. M.; et al. Factors influencing mobile banking: Extension of UTAUT. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 128–143. [CrossRef]

- Hoque, R.; Sorwar, G. Understanding the adoption of mHealth by the elderly. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 101, 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, T.T.; Cao, Y.; Weinhandl, R.; Yusron, E.; Lavicza, Z. Applying UTAUT to micro-lecture usage by math teachers in China. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1008. [CrossRef]

- El-Masri, M.; Tarhini, A. Factors affecting e-learning adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 650–664. [CrossRef]

- Dahri, N. A.; Yahaya, N.; Al--Rahmi, W. M.; Vighio, M. S.; Alblehai, F.; Soomro, R. B.; Shutaleva, A. AI academic support acceptance in Malaysian/Pakistani HEIs. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 18695–18744. [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Ge, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, X. AI chatbots in Chinese higher education: UTAUT & ECM. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1268549. [CrossRef]

- Bilquise, G.; Ibrahim, S.; Salhieh, S. M. Student acceptance of advising chatbot in HEIs. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 6357-6382. [CrossRef]

- Hooda, A.; Gupta, P.; Jeyaraj, A.; Giannakis, M.; Dwivedi, Y. K. Trust effects on e-government behavioral intention and use. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 67, 102553. [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Chong, A. Y. L.; Tsiga, Z.; Venkatesh, V. Meta-analysis of UTAUT: questioning validity and charting agenda. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2022, 23, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Al--Emran, M. Beyond technology acceptance: Tech--env--soc--econ sustainability theory. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102383. [CrossRef]

- Albanna, B.; Al--Sharafi, M.; AlQudah, A. Social influence & performance expectancy in AI product adoption. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 63, 102452. [CrossRef]

- Tanantong, Y.; Wongras, T. Critical factors impacting AI applications adoption in Vietnam. Systems 2023, 12, 28. [CrossRef]

- Baptista, G.; Oliveira, T. Understanding mobile banking: UTAUT perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 418–430. [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, J.; Ozturk, A. B.; Bilgihan, A. Security-related factors in extended UTAUT for NFC mobile payment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 460–474. [CrossRef]

- Merhi, M.; Hone, K.; Tarhini, A. UTAUT in Lebanon: E-learning adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 89, 234–246. [CrossRef]

- Al--Saedi, K.; Al--Emran, M.; Ramayah, T.; Abusham, E. Developing a general extended UTAUT model for M-payment adoption. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101293. [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B. Food tourism research: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 38–42. [CrossRef]

- Erjavec, J.; Manfreda, A. Online shopping adoption during COVID-19: UTAUT & herd behavior. J. Retail Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102867. [CrossRef]

- Al--Sharafi, M. A.; Al--Emran, M.; Arpaci, I.; Iahad, N. A.; AlQudah, A. A.; Iranmanesh, M.; Al--Qaysi, N. Gen Z use of AI and environmental sustainability: cross-cultural. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143, 107708. [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Cater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Org. Res. Meth. 2015, 18, 429-472. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 101–115. [CrossRef]

- Valderrama-Zurian, J.C., Melero-Fuentes, D., and Aleixandre-Benavent, R. 2019. Origin, characteristics, predominance and conceptual networks of eponyms in the bibliometric literature, J. Info. 2019, 13, 434-448. [CrossRef]

- Price, D.A general theory of bibliometric and other cumulative advantage processes. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. 1976, 27, 292–306. [CrossRef]

- Dobrov, G.; Randolph, R.; Rauch, W. New options for team research via international computer networks. Scientometrics 1979, 1, 387–404. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, P. Price’s square root law: Empirical validity and relation to Lotka’s law. Inf. Process. Manag. 1988, 24, 469–477. [CrossRef]

- Lotka, A. The frequency distribution of scientific productivity. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1926, 16.

- Zipf, G. Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1932.

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N., and Simoes, N. Publication performance through the lens of the h-index: how can we solve the problem of the ties? Soc. Sci. Q. 2019, 100, 2495–2506. [CrossRef]

- Clarivate (2025). Web of Science. Available at: https://www.webofknowledge.com/ (Accessed June 6, 2025).

- Sainaghi, R.; Phillips, P.; Baggio, R.; Mauri, A. Cross-citation and authorship analysis of hotel performance studies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H. Knowledge management vs. data mining: Research trend, forecast and citation approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 3160–3173. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. J., and Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.W.; Alakangas, S. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: a longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 787-804. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Quirós, L.; Ortega, J.L. Citation counts and inclusion of references in seven free-access scholarly databases: A comparative analysis. J. Inf. 2025, 19, 101618. [CrossRef]

- Asubiaro, T.; Onaolapo, S.; Mills, D. Regional disparities in Web of Science and Scopus journal coverage. Scientometrics 2024, 129, 1469–1491. [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91-108. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.D.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. A Bibliometric Analysis of Articles Citing the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. In Information Systems Theory. Integrated Series in Information Systems; Dwivedi, Y., Wade, M., Schneberger, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 28, pp. 37–62. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, Q.; Deng, Z.; Wang, J. Research Trend of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology Theory: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cobelli, N.; Blasioli, E. To be or not to be digital? A bibliometric analysis of adoption of eHealth services. The TQM Journal 2023, 35, 299–331. [CrossRef]

- Cobelli, N.; Blasi, S. Combining topic modeling and bibliometric analysis to understand the evolution of technological innovation adoption in the healthcare industry. European J. Innovation Management 2024, 27, 127–149. [CrossRef]

- Mijač, T., Jadrić, M. & Ćukušić, M. Measuring the success of information systems in higher education – a systematic review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 18323–18360. [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, A.; Ozyurt, O.; Gurcan, F. The mainstream and pattern detection of e-learning acceptance research: Insights from a bibliometric analysis (2010-2021). COLLNET J. Scientometrics Inf. Manag. 2023, 17, 39-59. [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, A.H.J.; Islam, S.M.N.; Prokofieva, M. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence Adoption on the Quality of Financial Reports on the Saudi Stock Exchange. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2025, 13, 21. [CrossRef]

- Sianes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Tirado-Valencia, P.; Ariza-Montes, A. Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals on the academic research agenda. A scientometric analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265409. [CrossRef]

| Author Full Names | Initial Year |

Final Year |

Contemporaneus | Research Age |

Articles | Articles / Year |

Times Cited, WoSCC |

Citations / Articles |

h-index Articles |

OKWP Articles |

SDGx | SDGx Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2003 | 2025 | Yes | 22 | 14 | 0.6 | 31676 | 2263 | 9 | 8 | SDG04 | 13 |

|

2013 | 2024 | Yes | 11 | 14 | 1.3 | 2841 | 203 | 6 | 6 | SDG04 | 13 |

|

2010 | 2022 | Yes | 12 | 13 | 1.1 | 3019 | 232 | 8 | 8 | SDG04 | 13 |

|

2010 | 2023 | Yes | 13 | 9 | 0.7 | 1971 | 219 | 4 | 4 | SDG04 | 9 |

|

2010 | 2025 | Yes | 15 | 8 | 0.5 | 9529 | 1191 | 5 | 5 | SDG04 | 8 |

|

2018 | 2023 | Yes | 5 | 8 | 1.6 | 475 | 59 | 1 | 1 | SDG11 | 8 |

|

2019 | 2024 | Yes | 5 | 7 | 1.4 | 430 | 61 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 7 |

|

2019 | 2024 | Yes | 5 | 7 | 1.4 | 576 | 82 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 7 |

|

2019 | 2024 | Yes | 5 | 7 | 1.4 | 460 | 66 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 7 |

|

2017 | 2024 | Yes | 7 | 6 | 0.9 | 858 | 143 | 4 | 4 | SDG11 | 6 |

|

2015 | 2021 | No | 6 | 6 | 1.0 | 939 | 157 | 3 | 3 | SDG04 | 6 |

|

2013 | 2023 | Yes | 10 | 6 | 0.6 | 357 | 60 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 6 |

|

2017 | 2024 | Yes | 7 | 5 | 0.7 | 824 | 165 | 4 | 4 | SDG11 | 5 |

|

2010 | 2025 | Yes | 15 | 5 | 0.3 | 1165 | 233 | 3 | 3 | SDG04 | 5 |

|

2013 | 2018 | No | 5 | 5 | 1.0 | 707 | 141 | 3 | 3 | SDG04 | 5 |

|

2015 | 2025 | Yes | 10 | 5 | 0.5 | 311 | 62 | 2 | 2 | SDG04 | 4 |

|

2015 | 2021 | No | 6 | 5 | 0.8 | 697 | 139 | 2 | 2 | SDG04 | 5 |

|

2020 | 2023 | Yes | 3 | 5 | 1.7 | 426 | 85 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 5 |

|

2019 | 2024 | Yes | 5 | 5 | 1.0 | 363 | 73 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 5 |

|

2015 | 2017 | No | 2 | 5 | 2.5 | 520 | 104 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 5 |

|

2013 | 2023 | Yes | 10 | 5 | 0.5 | 273 | 55 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 5 |

|

2016 | 2021 | No | 5 | 4 | 0.8 | 821 | 205 | 3 | 3 | SDG04 | 4 |

|

2010 | 2019 | No | 9 | 4 | 0.4 | 1690 | 423 | 3 | 3 | SDG04 | 4 |

|

2011 | 2017 | No | 6 | 4 | 0.7 | 8623 | 2156 | 2 | 2 | SDG04 | 4 |

|

2021 | 2024 | Yes | 3 | 4 | 1.3 | 254 | 64 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 4 |

|

2019 | 2024 | Yes | 5 | 4 | 0.8 | 285 | 71 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 4 |

|

2018 | 2025 | Yes | 7 | 4 | 0.6 | 312 | 78 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 4 |

|

2019 | 2024 | Yes | 5 | 4 | 0.8 | 285 | 71 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 4 |

|

2015 | 2022 | Yes | 7 | 4 | 0.6 | 166 | 42 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 3 |

|

2010 | 2019 | No | 9 | 4 | 0.4 | 338 | 85 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 3 |

|

2013 | 2024 | Yes | 11 | 4 | 0.4 | 231 | 58 | 1 | 1 | SDG04 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).