Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Image type | Colour space /bit/ |

FD | SFDDSR /16bit/ |

EW-SFDDSR /real bit/ |

SFDDSR /real bit/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

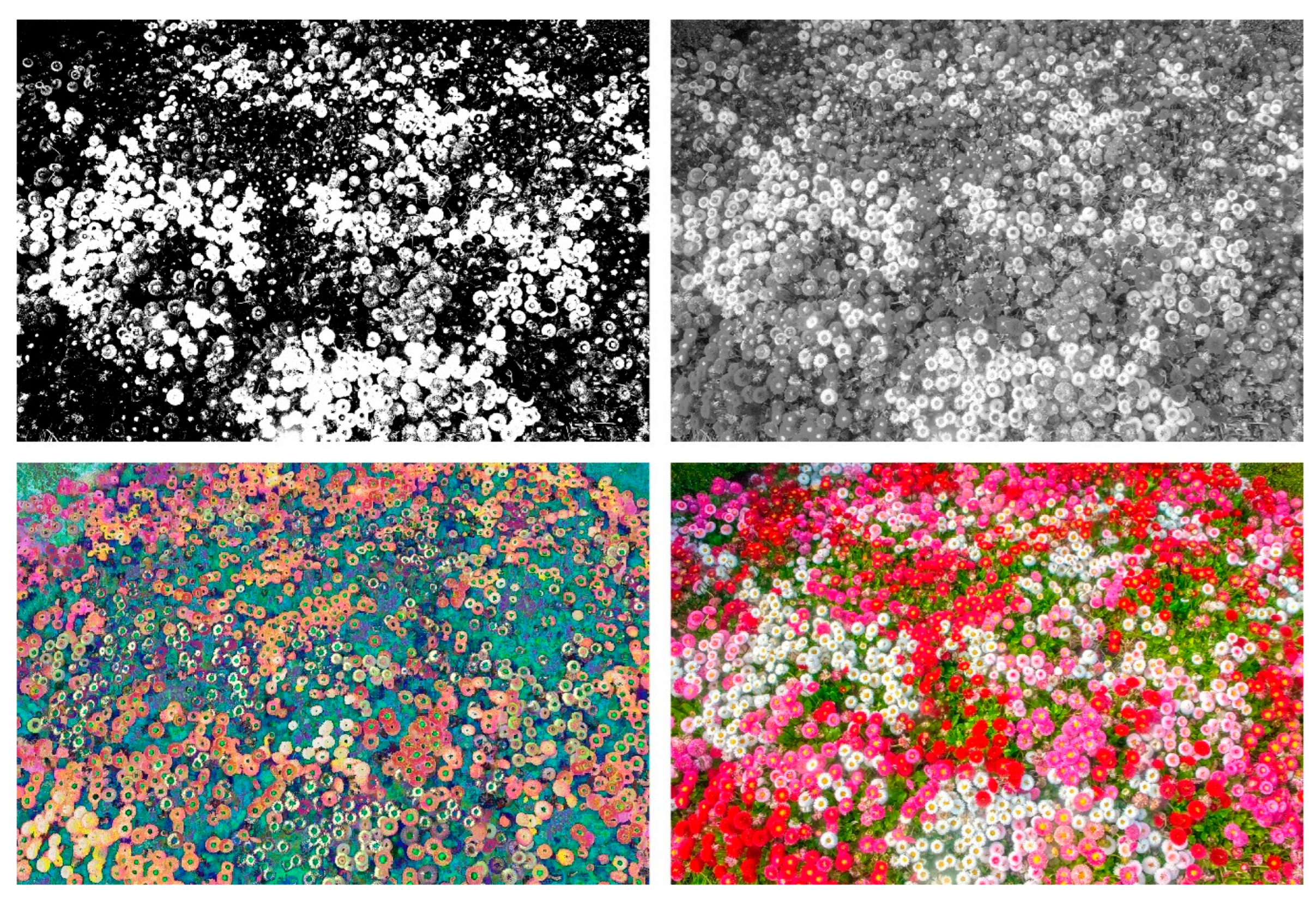

| Black-White | 1 | 2 | 0,2113 | 0,9332 | 1,0000 |

| Greyscale | 8 | 2 | 0,8312 | 0,9908 | 0,9999 |

| Palette | 8 | 2 | 0,8314 | 0,9659 | 1,0000 |

| RGB colour | 24 | 2 | 2,3513 | 2,7652 | 2,8869 |

- Non-negative definite, that is

- 2.

- Symmetrical, that is

- 3.

- It satisfies the triangle inequality, that is,

- 4.

- Regularity, this means that the points of the discrete image plane must be uniformly dense, i.e.

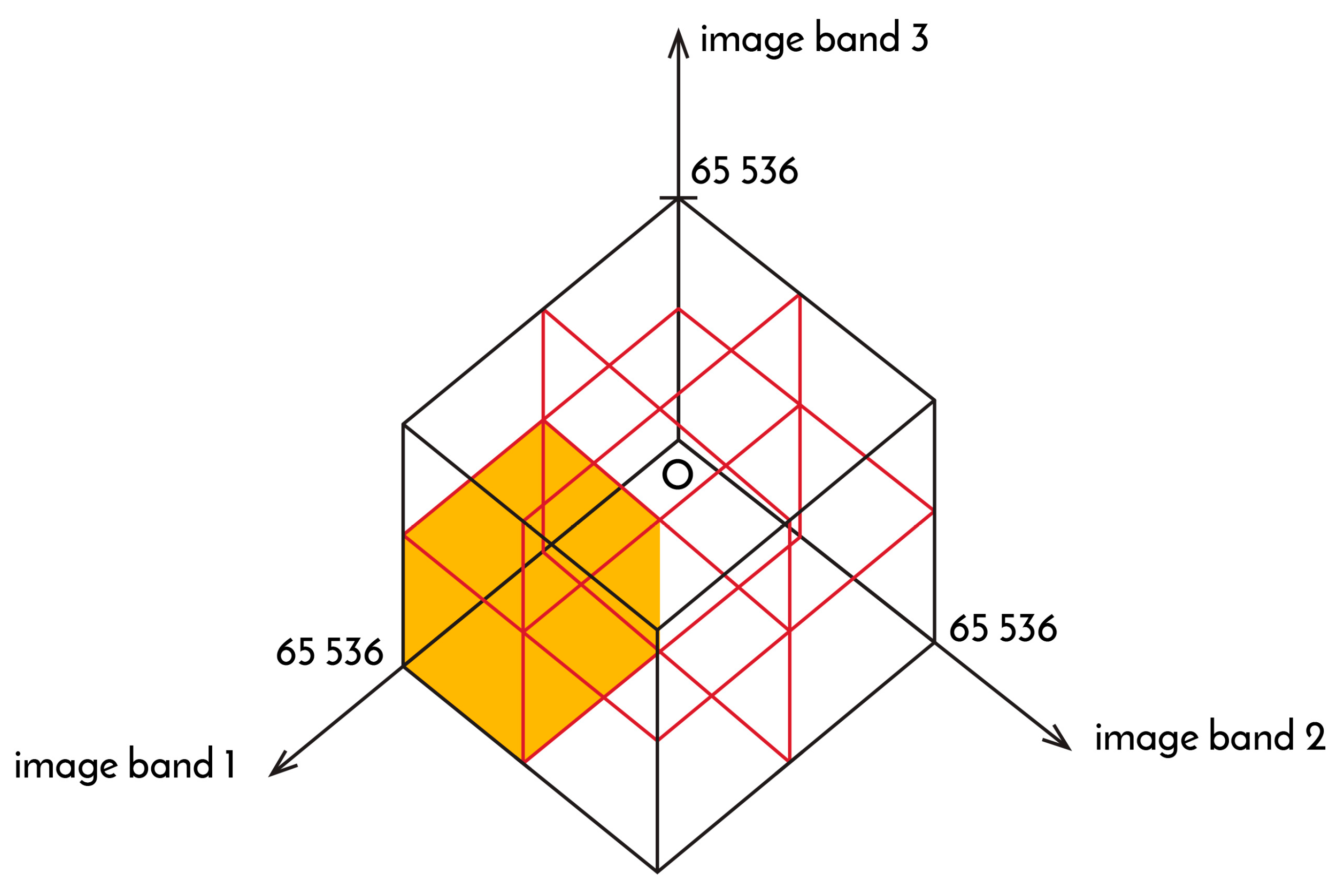

- n—number of image (h, t, T) excluding layers or bands;

- S—spectral resolution of the (h, t, T) excluding layer, in bits;

- BMj (h, t, T)—number of spectral boxes containing valuable pixels in case of j-bits (h, t, T) distributions;

- BTj (h, t, T)—total number of possible spectral boxes in case of j-bits (h, t, T) distributions.

- n=1 black and white or greyscale image

- n=2 joint measurement of two bands used for index analysis (e.g. NDVI, SAVI based indices)

- n=3 RGB, YCC, HSB, IHS colour space image

- n=4 traditional colour printer CMYK space image, some CMOS sensor or Landsat 1–5 Multispectral Scanner (MSS)

- n=6 photo printer CCpMMpYK space image, Landsat ETM satellite images

- n=7 Landsat 4–5 Thematic Mapper (TM)

- n=8 Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+)

- n=10 MicaSense Dual Camera System (Red and Blue)

- n=11 Landsat Operational Land Imager (OLI) for optical bands and the Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) for thermal bands

- n=13 Sentinel-2A satellite sensor

- n=30 CHNSPEC FS-50/30

- n=32 DAIS7915 VIS-NIR or DAIS7915 SWIP-2 sensors

- n=60 COIS VNIR sensor

- n=79 DAIS7915 all

- n=126 HyMap sensor

- n>250 CHNSPEC FigSpec Series Full-Spectrum Hyperspectral Imager FS-2A

- n=254 AISA Hawk sensor

- n=488 AISA Eagle sensor

- n=498 AISA Dual sensor (Eagle and Hawk)

2. Materials and Methods

- A.

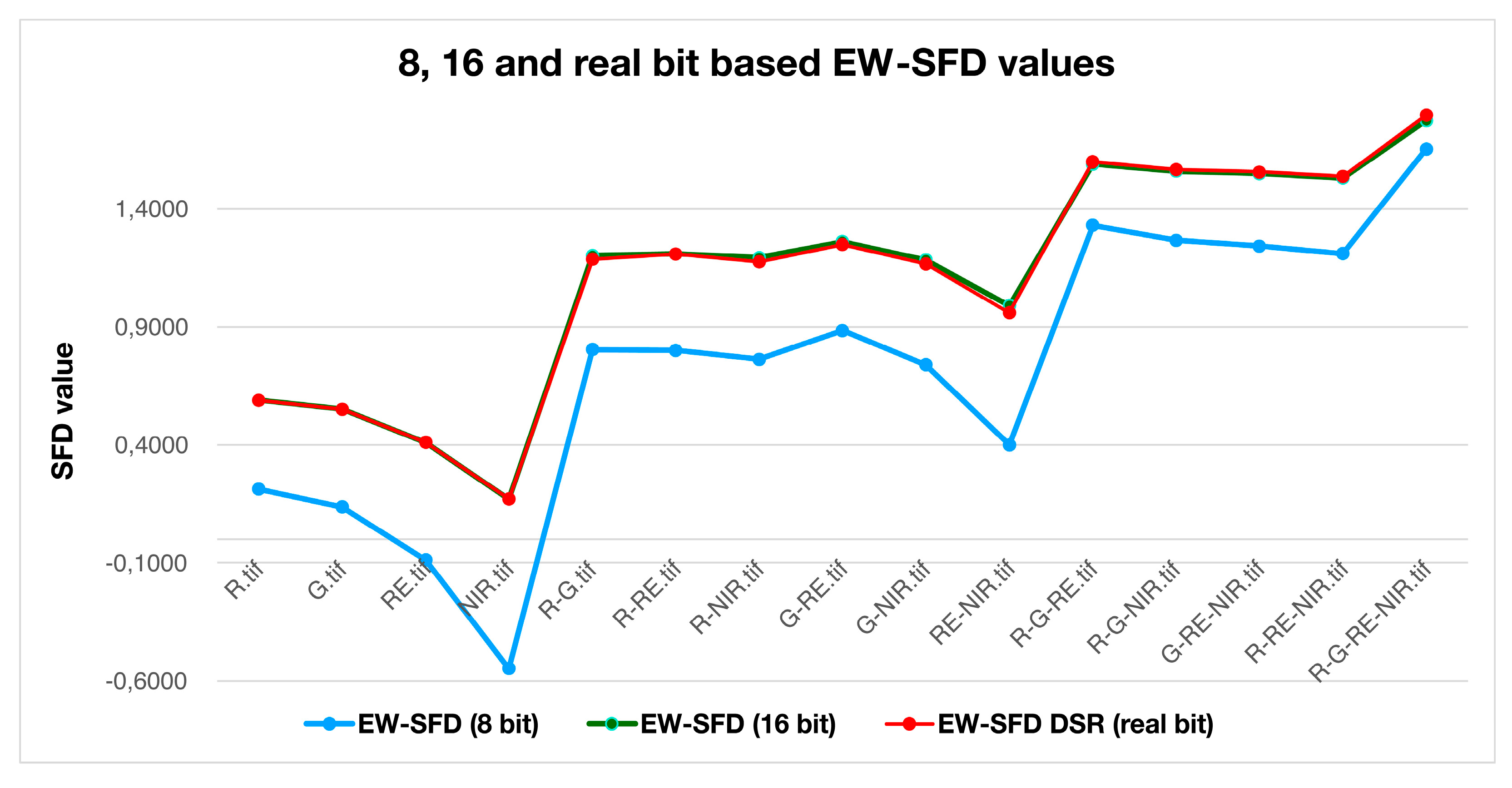

- 8 bit – SFDESR, SFDDSR and EW-SFD

- A.

- B. 16 bit - SFDESR, SFDDSR and EW-SFD

- A.

- C. real bit - SFDESR, SFDDSR and EW-SFD

3. Results

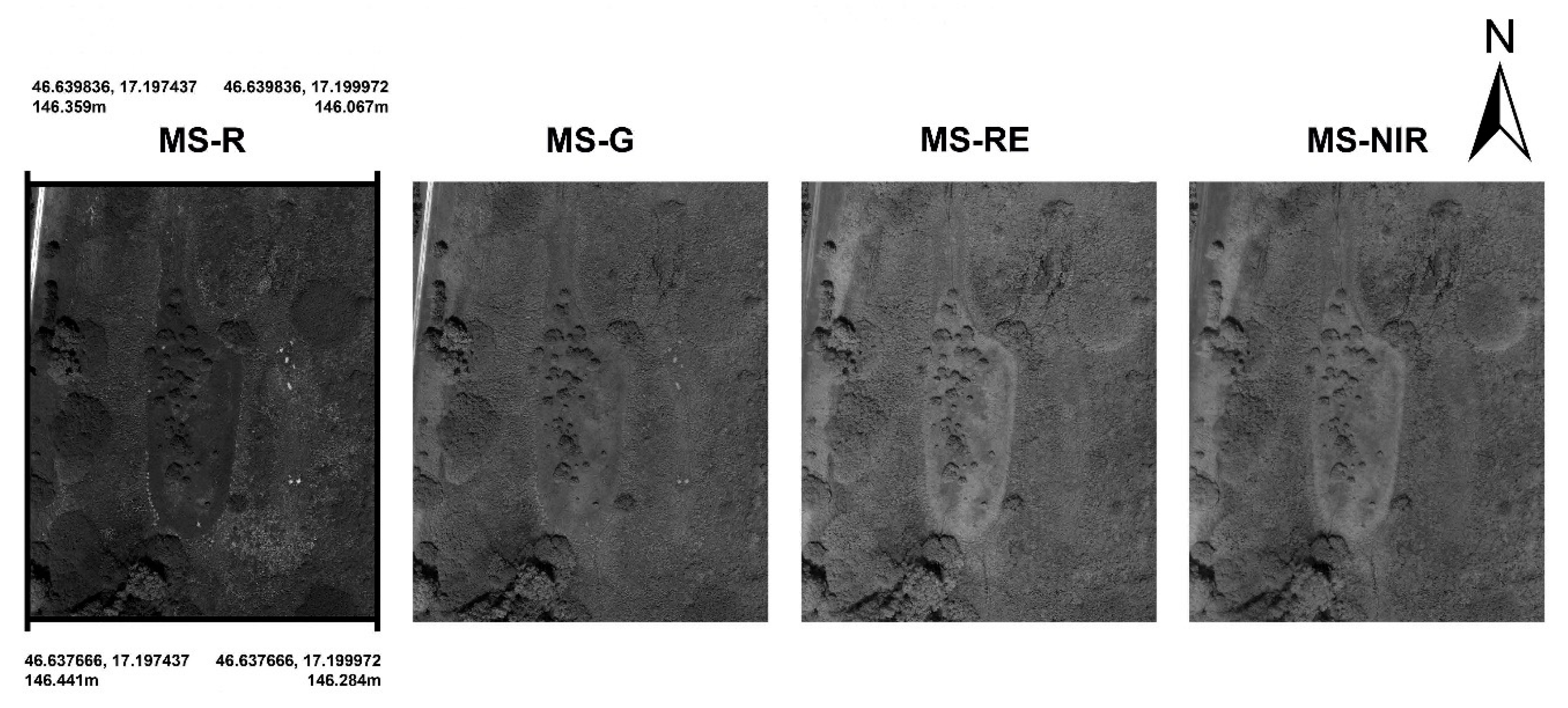

3.1. Measuring Image Data of Camera Arrays

| Image band(s) | EW-SFD /8 bit/ |

EW-SFD /16 bit/ |

EW-SFDDSR /real bit/ |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | 0,2117 | 0,5886 | 0,5886 |

| G | 0,1358 | 0,5501 | 0,5501 |

| RE | -0,0879 | 0,4093 | 0,4093 |

| NIR | -0,5485 | 0,1702 | 0,1702 |

| Average of previous four values | -0,0722 | 0,4295 | 0,4295 |

| R and G | 0,8034 | 1,2018 | 1,1861 |

| R and RE | 0,7999 | 1,2085 | 1,2085 |

| R and NIR | 0,7622 | 1,1928 | 1,1756 |

| G and RE | 0,8841 | 1,2605 | 1,2476 |

| G and NIR | 0,7388 | 1,1829 | 1,1651 |

| RE and NIR | 0,3999 | 0,9898 | 0,9598 |

| Average of previous six values | 0,7314 | 1,1727 | 1,1571 |

| R-G-RE | 1,3296 | 1,5885 | 1,5985 |

| R-G-NIR | 1,2665 | 1,5584 | 1,5664 |

| G-RE-NIR | 1,2422 | 1,5486 | 1,5560 |

| R-RE-NIR | 1,2099 | 1,5301 | 1,5362 |

| Average of previous four values | 1,2620 | 1,5564 | 1,5643 |

| R-G-RE-NIR | 1,6531 | 1,7738 | 1,7979 |

3.2. Spectral Analysis of RGB Images of Potato Tubers

| Potato variety | EW-SFDDSR /real bit/ |

SFDDSR /real bit/ |

Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Réka | 2,0240 | 2,3187 | 2,17135 |

| rebeka | 2,0626 | 2,3403 | 2,20145 |

| Agata | 2,0391 | 2,3246 | 2,18185 |

| Arosa | 1,9885 | 2,3290 | 2,15875 |

| Ronina | 2,0464 | 2,3283 | 2,18735 |

| Impala | 1,7476 | 2,1957 | 1,97165 |

| Rosita | 1,6624 | 2,1710 | 1,9167 |

| amorosa | 2,1406 | 2,4204 | 2,2805 |

| Derby | 2,0990 | 2,3648 | 2,2319 |

| white lady | 1,9425 | 2,2455 | 2,094 |

| Roko | 1,9396 | 2,2634 | 2,1015 |

| Aladin | 1,9723 | 2,2943 | 2,1333 |

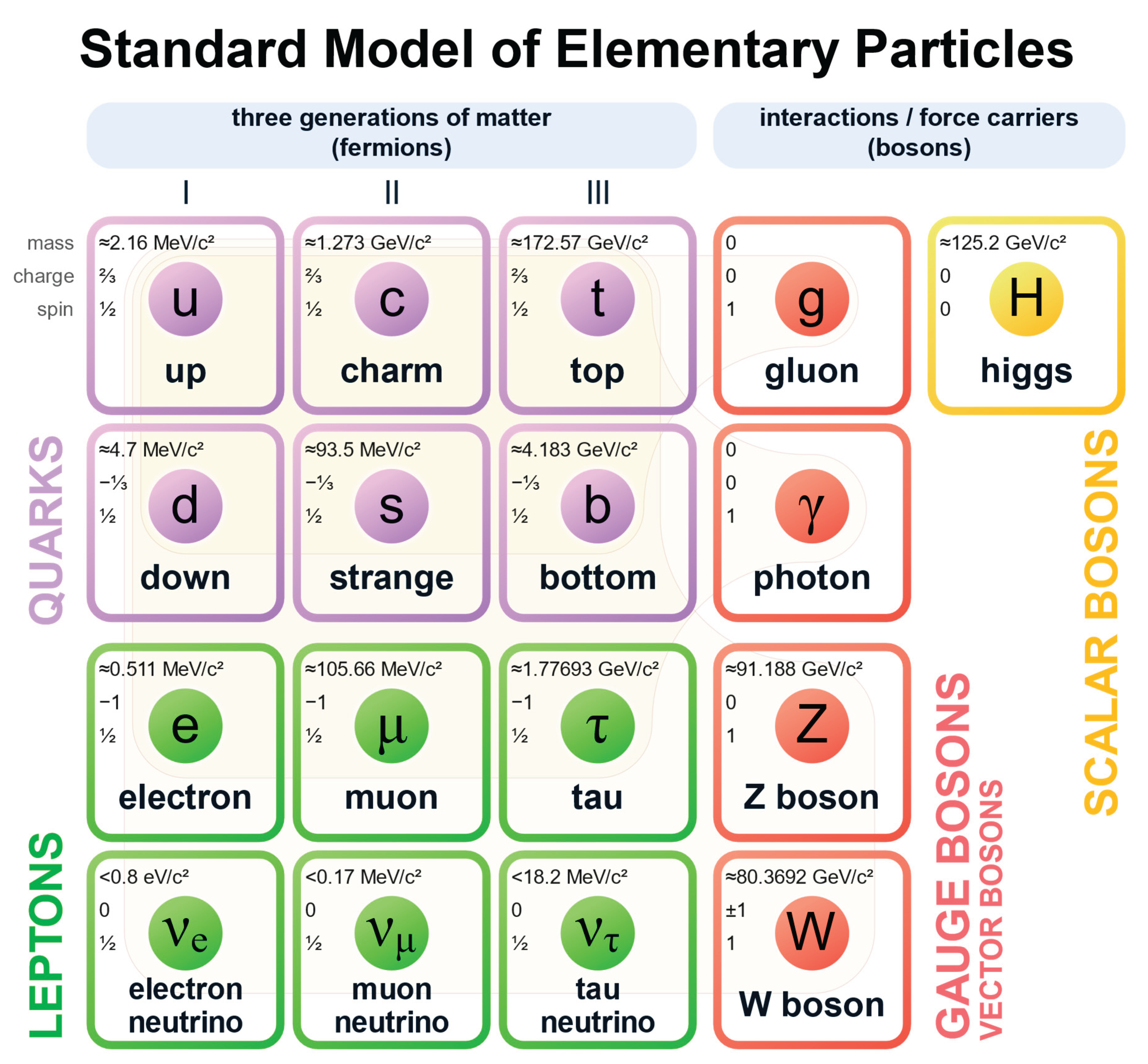

3.3. Standard-Model Based Image Sensor

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AISA Dual | Specim AISA Dual Hyperspectral sensor |

| AISA Eagle | Specim Eagle Hyperspectral sensor |

| AISA Hawk | Specim Hawk Hyperspectral sensor |

| BMj | number of spectral boxes containing valuable pixels for j-bit |

| BTj | total number of possible spectral boxes for j-bits |

| BW | Black and White (1 bit) |

| AVIRIS | NASA Airborne visible/infrared imaging spectrometer |

| NIR | Near-InfraRed |

| CT | Computer Tomography |

| DAIS | Digital Airborne Imaging Spectrometer |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| E | Entropy |

| ETM+ | Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus |

| H(C) | Hausdorff–Besicovitch Dimension |

| MS | Multispectral |

| EW-SFD | Entropy-Weighted Spectral Fractal Dimension |

| FD | Fractal Dimension |

| FIR | Fared InfraRed |

| GND | Ground (altitude relative to take-off point) |

| MCS | Mass, Charge, Spin (analogue as RGB color-space) |

| MS-NIR | Multispectral camera array Near-InfraRed band |

| MS-R | Multispectral camera array R band |

| MS-RE | Multispectral camera array Red-Edge band |

| MSS | Landsat 1-5 Multispectral Scanner |

| MS-G | Multispectral camera array G band |

| NIR | Near Infrared |

| OLI | Landsat 8-9 Operational Land Imager optical bands |

| RE | Red-Edge |

| REIP-SFD | Red Edge Inflection Point on SFD curves |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue (as color-space) |

| RGB-B | B band of RGB image of Bayer sensor |

| RGB-G | G band of RGB image of Bayer sensor |

| RGB-R | R band of RGB image of Bayer sensor |

| S | spectral resolution of the layer, in bits |

| SFD | Spectral Fractal Dimension |

| SmIS | Standard-model based Image Sensor |

| TIRS | Landsat 8-9 Thermal Infrared Sensor |

| TM | Landsat 4–5 Thematic Mapper Satellite |

| tP | Planck time |

| tU | Age of the Universe |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UAS | Unmanned Aerial System |

| VIS | Visible |

References

- Oktaviana, A.A. , Joannes-Boyau, R., Hakim, B. et al. Narrative cave art in Indonesia by 51,200 years ago. Nature 2024, 631, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1983; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Soltanifar, M. A Generalization of the Hausdorff Dimension Theorem for Deterministic Fractals. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, K. Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2014; p. 44, 45, 48, 49, 72, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Barnsley, M.F. Fractals Everywhere; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 182–183. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, J. Spectral fractal dimension. In Proceedings of the 7th WSEAS Telecommunications and Informatics (TELE-INFO ’05), Prague, Czech Republic, 12–14 March 2005; pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, R. Random fractals: Characterisation and measurement. In Scaling Phenomena in Disordered Systems; Pynn, R., Skjeltorps, A., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Peleg, S.; Naor, J.; Hartley, R.; Avnir, D. Multiple Resolution Texture Analysis and Classification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1984, 4, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, M.T.; Blackledge, J.M.; Andrews, P.R. Fractal Geometry in Digital Imaging; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; p. 45–46, 113-119. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, M. Fractals and the accuracy of geographical measure. Math. Geol. 1980, 12, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCola, L. Fractal analysis of a classified Landsat scene. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1989, 55, 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K. Scale based simulation of topographic relief. Am. Cartogr. 1988, 12, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelberg, M. The Development of a Curve and Surface Algorithm to Measure Fractal Dimension. Master’s Thesis, 1982, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

- Barnsley, M.F.; Devaney, R.L.; Mandelbrot, B.B.; Peitgen, H.-O.; Saupe, D.; Voss, R.F.; Fisher, Y.; McGuire, M. The Science of Fractal Images; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Theiler, J. Estimating fractal dimension. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1990, 7, 1055–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, J. Measuring of spectral fractal dimension. New Math. Nat. Comput. 2007, 3, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard of the Camera & Imaging Products Association; CIPA DC- 008-Translation-2024, 2024, pp. 76-86., https://www.cipa.jp/std/documents/download_e.html?CIPA_DC-008-2024-E.

- Berke, J.; Gulyás, I.; Bognár, Z.; Berke, D.; Enyedi, A.; Kozma-Bognár, V.; Mauchart, P.; Nagy, B.; Várnagy, Á.; Kovács, K.; et al. Unique algorithm for the evaluation of embryo photon emission and viability. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. Prediction and entropy of printed English. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1951, 30, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, J. Using spectral fractal dimension in image classification. In Innovations and Advances in Computer Sciences and Engineering; Sobh, T., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, J. Application Possibilities of Orthophoto Data Based on Spectral Fractal Structure Containing Boundary Conditions. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B. How long is the coast of Britain? Statistical self-similarity and fractional dimension. Sci. New Ser. 1967, 156, 636–638. [Google Scholar]

- Hentschel, H.G.E.; Procaccia, I. The Infinite Number of Generalized Dimensions of Fractals and Strange Attractors. Phys. D 1983, 8, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, E. Fractal Dimensions of Networks, Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020.

- Berke, J. Fractal dimension on image processing. In Proceedings of the 4th KEPAF Conference on Image Analysis and Pattern Recognition, Miskolc-Tapolca, Hungary, 28–30 January 2004; Volume 4, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, J. The Structure of dimensions: A revolution of dimensions (classical and fractal) in education and science. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference for History of Science in Science Education, Conference, Keszthely, 12–16 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, J. Real 3D terrain simulation in agriculture. In Proceedings of the 1st Central European International Multimedia and Virtual Reality Conference, Veszprém, Hungary, 6–8 May 2004; Volume 1, pp. 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, J. Applied spectral fractal dimension. In Proceedings of the Joint Hungarian-Austrian Conference on Image Processing and Pattern Recognition, Veszprém, Hungary, 11–13 May 2005; pp. 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Busznyák, J.; Berke, J. Psychovisual comparison of image compression methods under laboratory conditions. In Proceedings of the 4th KEPAF Conference on Image Analysis and Pattern Recognition, Miskolc-Tapolca, Hungary, 28–30 January 2004; Volume 4, pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, J.; Busznyák, J. Psychovisual Comparison of Image Compressing Methods for Multifunctional Development under Laboratory Circumstances. WSEAS Trans. Commun. 2004, 3, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, J.; Polgár, Z.; Horváth, Z.; Nagy, T. Developing on exact quality and classification system for plant improvement. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2006, 12, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, J. Measuring of Spectral Fractal Dimension. In Proceedings of the International Conferences on Systems, Computing Sciences and Software Engineering, 10-20 December 2005; Paper No. 62., (SCSS 05).

- Kozma-Bognár, V. The application of Apple systems. J. Appl. Multimed. 2007, 2, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kozma-Bognar, V.; Berke, J. New Evaluation Techniques of Hyperspectral Data. J. Syst. Cybern. Inform. 2009, 8, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Clevers, J.G.P.W.; De Jong, S.M.; Epema, G.F.; Van Der Meer, F.D.; Bakker, W.H.; Skidmore, A.K.; Scholte, K.H. Derivation of the red edge index using the MERIS standard band setting, International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2002, 23 (16), 3169–3184.

- Mutanga, O.; Skidmore, A. K. ; Integrating imaging spectroscopy and neural networks to map grass quality in the Kruger National Park, South Africa, Remote Sensing of Environment, 2004, 90. 104– 115.

- Berke, J.; Bíró, T.; Burai, P.; Kováts, L.D.; Kozma-Bognar, V.; Nagy, T.; Tomor, T.; Németh, T. Application of remote sensing in the red mud environmental disaster in Hungary. Carpathian J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2013, 8, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bíró, T.; Tomor, T.; Lénárt, C.S.; Burai, P.; Berke, J. Application of remote sensing in the red sludge environmental disaster in Hungary. Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hung. 2012, 47, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burai, P.; Smailbegovic, A.; Lénárt, Cs.; Berke, J.; Milics, G.; Tomor, T.; Bíró, T. Preliminary Analysis of Red Mud Spill Based on Ariel Imagery. Acta Geogr. Debrecina Landsc. Environ. 2011, 5, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, J.; Kozma-Bognár, V. Investigation possibilities of turbulent flows based on geometric and spectral structural properties of aerial images. In Proceedings of the 10th National Conference of the Hungarian Society of Image Processing and Pattern Recognition, Kecskemét, Hungary, 27–30 January 2015; pp. 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kozma-Bognár, V.; Berke, J. Entropy and fractal structure based analysis in impact assessment of black carbon pollutions. Georg. Agric. 2013, 17, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kozma-Bognar, V.; Berke, J. Determination of optimal hyper- and multispectral image channels by spectral fractal structure. In Innovations and Advances in Computing, Informatics, Systems Sciences, Networking, and Engineering; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, (LNEE), Sobh, T., Elleithy, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 313, p. 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro-Posada, P. A simple method for estimating the fractal dimension from digital images: The compression dimension. Chaos Solitions Fractals 2016, 91, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, M. A.; Sabathiel, N.; Ahammer, H. Noise dependency of algorithms for calculating fractal dimensions in digital images, Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2015, 78, 39-46.

- Spodarev, E.; Straka, P.; Winter, S. Estimation of fractal dimension and fractal curvatures from digital images, Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 2015, 75, 134-152.

- Ahammer, H.; Mayrhoffer-Reinhartshuber, M. Image pyramids for calculation of the box counting dimension, Fractals 2012, 20, 03n04, 281-293.

- Karydas, C.G. Unified scale theorem: A mathematical formulation of scale in the frame of Earth observation image classification. Fractal Fract. 2021, 5, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachraoui, C.; Mouelhi, A.; Drissi, C.; Labidi, S. Chaos theory for prognostic purposes in multiple sclerosis. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 2021, 0, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Adheem, W. Image Processing Techniques for COVID-19 Detection in Chest CT. J. Al-Rafidain Univ. Coll. Sci. 2022, 52(2), 218–226.

- Csákvári, E.; Halassy, M.; Enyedi, A.; Gyulai, F.; Berke, J. Is Einkorn Wheat (Triticum monococcum L.) a Better Choice than Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)? Wheat Quality Estimation for Sustainable Agriculture Using Vision-Based Digital Image Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastag, V.K.; Óbermayer, T.; Enyedi, A.; Berke, J. Comparative study of Bayer-based imaging algorithms with student participation. J. Appl. Multimed. 2019, XIV/1, 7–12.

- Berke, J.; Kozma-Bognár, V. Measurement and comparative analysis of gain noise on data from Bayer sensors of unmanned aerial vehicle systems. In X. Hungarian Computer Graphics and Geometry Conference; SZTAKI: Budapest, 2022; 136–142.

- Kevi, A.; Berke, J.; Kozma-Bognár, V. Comparative analysis and methodological application of image classification algorithms in higher education. J. Appl. Multimed. 2023, XVIII/1, 13–16.

- Bodis, J.; Nagy, B.; Bognar, Z.; Csabai, T.; Berke, J.; Gulyas, I.; Mauchart, P.; Tinneberg, H.R.; Farkas, B.; Varnagy, A.; et al. Detection of Ultra-Weak Photon Emissions from Mouse Embryos with Implications for Assisted Reproduction. J. Health Care Commun. 2024, 9, 9041.Fréchet, M.M. Sur quelques points du calcul fonctionnel. Rend. Circ. Matem. 1906, 22, 1–72. J. Health Care Commun. 1906, 9, 9041.Fr. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biró, L.; Kozma-Bognár, V.; Berke, J. Comparison of RGB Indices used for Vegetation Studies based on Structured Similarity Index (SSIM). J. Plant Sci. Phytopathol. 2024, 8, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma-Bognár, K.; Berke, J.; Anda, A.; Kozma-Bognár, V. Vegetation mapping based on visual data. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2024, 25, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzéki, M.; Kozma-Bognár, V.; Berke, J. Examination of vegetation indices based on multitemporal drone images. Gradus 2023, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fréchet, M.M. Sur quelques points du calcul fonctionnel. Rend. Circ. Matem. 1906, 22, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baire, R. Sur les fonctions de variables réelles. Ann. Mat. 1899, 3, 1–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, J.C. Image Analysis and Mathematical Morphology; Academic Press: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. Fractals: Forms, Chance and Dimensions; W.H. Freeman and Company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, S. Programming the Universe. New York, NY: Random House, Inc., 2007.

- Lloyd, S. Ultimate physical limits to computation. Nature 406, 1047–1054 (2000). [CrossRef]

| Image layer type | Values | Number of different values | Color space /bit/ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass | 0 MeV/c2, 0,8 eV/c2, 0,17 MeV/c2, 0,511 MeV/c2, 2,16 MeV/c2, 4,7 MeV/c2, 18,2 MeV/c2, 93,5 MeV/c2, 105,66 MeV/c2, 1,273 GeV/c2, 1,77693 GeV/c2, 4,183 GeV/c2, 80,3692 GeV/c2, 91,188 GeV/c2, 125,2 GeV/c2, 172,57 GeV/c2, | 16 | 4 |

|

Charge |

-1, -1/3, 0, 2/3, 1 |

5 |

3 |

|

Spin |

0, ½, 1 |

3 |

2 |

|

MCS color |

24 |

24 |

9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).