I. Introduction

The prevailing usage of generative artificial intelligence (AI) across social commerce use-contexts is resulting in an unprecedented rate of ubiquitous multimodal AI-generated content (AIGC), including graphics and video, inundating the platform ecosystem. These contents not only enhance user engagement in the quality of the interaction but also introduce new intellectual property (IP) risks, including difficult traceability, uncertain boundaries of use, and ambiguity of compliance responsibility, which have emerged as primary pain points in platform governance [

1].

In the context of US DMCA 512 "safe harbor" provisions and EU's Digital Services Act (DSA) framework, where a "reasonably feasible content use control mechanism" is absent, the platform runs the risk of joint and several liability for the infringement along with fines [

2].

Mainstream platforms, at present, such as YouTube and Meta rely on "post-event testing" (e.g., content fingerprinting, OCR comparison) for copyright compliance control, which engenders "lagging in discovery, convoluted appeals, and freeze-and-chaos" [

3]. In contrast, the "Compliance-by-Design" scheme endorses the notion of implementing machine-readable licenses and rules of use within the early stages of content generation or upload, and using automated execution engines and API interfaces of real-time content usage monitoring [

4]. This micro-licensing ecosystem, as a whole, ensures granulated control of content usage, and provides hopes for a "standardized authorization ledger" for AI content distribution.

To solve the above issue, the present study seeks to establish a compliance protocol stack that combines two open standards: first, the C2PA (Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity) specification is used to sign the content and create a trusted editing chain and proof of provenance; second, the standard for W3C ODRL (Open Digital Rights Language) is designed to embed usage conditions such as use, region, frequency, fee, and revocation, into metadata of the content as semantic policies to achieve true "policy as content" [

5].

The platform side integrates with the REST API interface via low-latency event streams to facilitate the upload, sign, policy bind, share, monitor usage, and freeze violation closed-loop process, and also maps and integrates the compliance evidence chain with "notification-removal-counter-notification" legal process of DMCA §512 to advance the compliance transparency and defense against legal claims of the platform.

III. Methodologies

A. Content Signing and Source Verification

In social e-commerce platforms, AI-generated content (AIGC) needs to undergo compliance checks after uploading to ensure the traceability of the content's source and editing chain. To ensure the legality and integrity of uploaded content, we adopt the C2PA (Verifiable Source/Edit Chain) standard, which ensures that any actions after uploading the content can be traced back to the original uploader by generating content credentials and encrypting them using digital signature technology. The process of signing content can be represented by the following Equation 1:

where the

in the formula represents the uploaded AI-generated content,

is the output after hashing the content, the purpose is to obtain a unique identifier for the content to prevent tampering, the hash value is an irreversible function, ensuring that the generated hash value is unique every time the content is uploaded. Through

, the platform uses a private key to encrypt the hash value and generate a digital signature

, which can prove that the content was indeed uploaded by the platform and has not been tampered with. This signature allows us to verify the origin of the content and trace its editing history.

When performing signature verification, the digital signature is decrypted using a public key, thereby verifying the integrity of the content. The specific process can be represented by the following Equation 2:

If the decrypted content hash is consistent with the current content hash value, it means that the content has not been tampered with and the verification is successful. W3C ODRL policies can refine the usage conditions of content, such as the number of uses, geographical restrictions, charging standards, etc., so as to achieve refined content management. The purpose policy for each content is set by the platform based on the nature of the content and the uploader's requirements, which can be dynamically adjusted. The purpose policy matrix

defines various restrictions on the use of content in form of Equation 3:

where

represents the strategy under the

-th use and

-th constraint conditions in the matrix. Each row of the short array represents a specific purpose, and each column represents a specific constraint related to that use (e.g., specific value, geographic range, rate scale, etc.). For example,

can represent the maximum number of views of a content, and

can represent the geographical limit of viewing.

B. Usage Settlement and Violation Monitoring

At the same time, in order to prevent violations on the platform, we have designed a violation monitoring mechanism to monitor each content use in real time and determine whether there are violations through algorithms. If violations are found, the platform will take freezing measures and notify the relevant parties. The usage settlement formula is based on time and usage, and the calculation process is as follows in Equation 4:

where

represents the content usage at time

,

is the content rate that changes over time, and

and

are the start and end times of content usage, respectively. Through the calculation of points, the platform can derive the total cost over a certain time period.

For the monitoring of violations, we introduce the violation detection function

, as shown in Equation 5:

Specifically, when the platform receives an infringement report, it first notifies the infringer through the notification operation (

), and if the infringer submits a counter-notice (

), the platform will review the content of the counter-notice and decide whether to restore the legality of the content. The notification operation

is expressed as Equation 6:

Among them,

means that the platform will notify content

of copyright infringement. If the infringing party files a counter-notice, it will enter the review process, as shown in Equation 7:

This process ensures that the platform can reasonably and legally handle and review content in the event of copyright disputes, protecting the legitimate rights and interests of the original creator and content uploader.

IV. Experiments

A. Experimental Setup

We utilize popular and reputable open-source multimodal datasets: the YFCC100M and MS COCO (CC BY 4.0). From these, the YFCC100M dataset consists of uploaded images and videos by Flickr users, as provided by Yahoo Labs, and consists of over 100 million samples including full uploader information, timestamps, geographical location, EXIF parameters, and licensing agreement fields, making it an ideal test set for creating a real "user distribution and tracking process for user content." We obtain a subset of images that have complete metadata and license annotations for more manageable ways to use a multitude of images.

In addition, we simulate the platform initiating a C2PA signature chain when an uploader uploads an image. Finally, we bind ODRL policies to limit how many times the content is distributed, where it can be displayed, and how often it can be used. The MS COCO dataset contains high-quality image to text samples in that each image has five natural language descriptions that have a viable content structure and visual semantic relationship making it appropriate for testing the process of policy embedding and compliance execution of advertising AI generated content on a platform for uploading, using, and freezing content. The following are the four baseline methods used in the experimental phase of this study.

Static Rule-Matching (SRM): Based on the static rule template preset by the platform, Boolean condition judgment, sourceless signature and policy structure, belongs to the most basic manual management paradigm.

Tag-Based Policy Enforcement (TBPE): Matching policy rules by extracting image or text labels has initial automation capabilities, but the policy semantics are not uniform and the execution flexibility is limited.

Blockchain Content Registry (BBCR): Generates unique hashes for content and registers them on the chain to verify editing history and ownership, but lacks the ability to bind and auto-execute them for purpose policies.

XACML-Based Access Control (XACML): XACML expresses access policies using the structured permission control language, which is suitable for closed systems, and is not suitable for dynamic content distribution.

B. Experimental Analysis

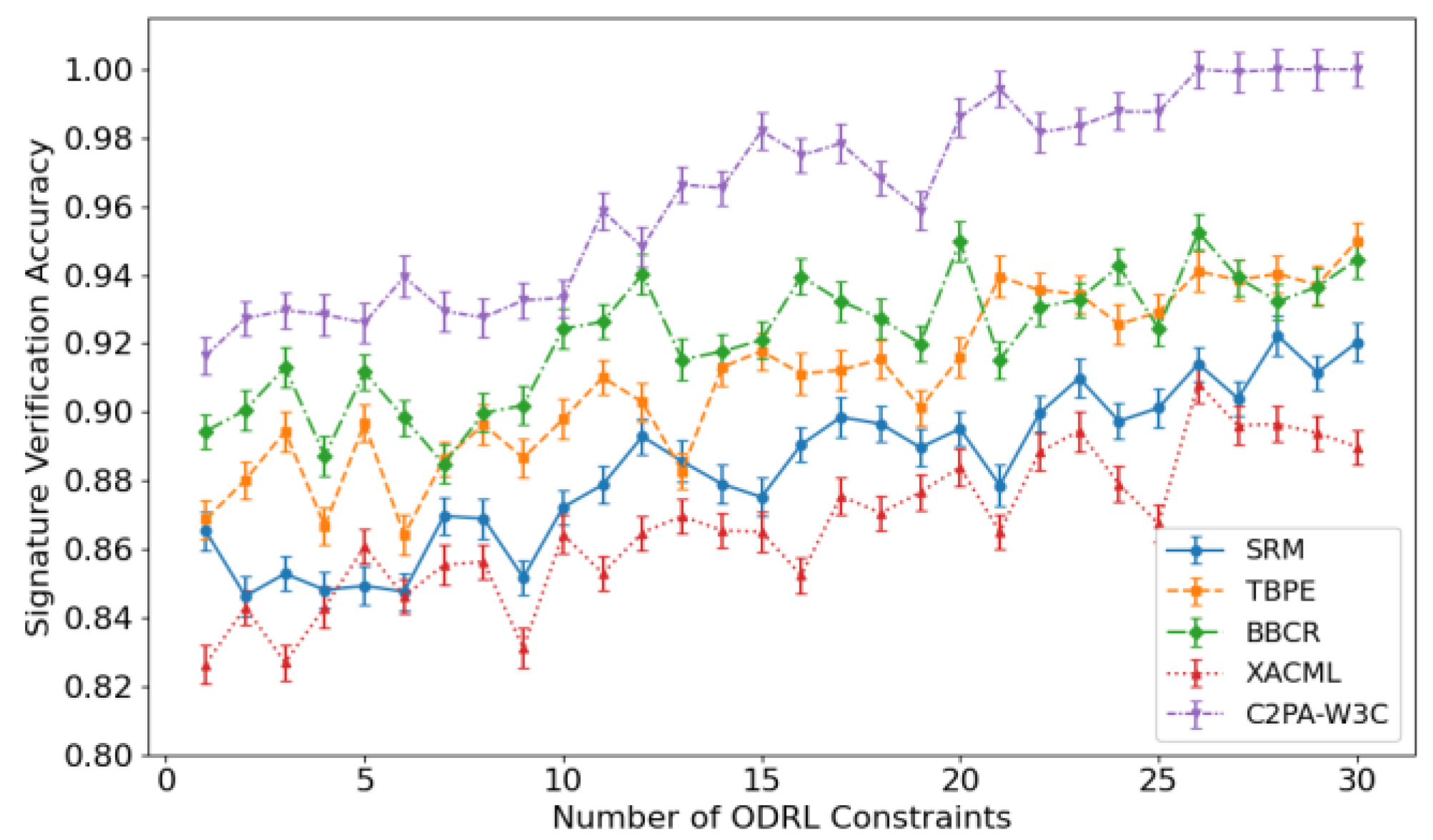

The signature verification success rate measures the platform's ability to accurately identify and verify the authenticity of content signatures. Based upon the findings presented in

Figure 1, although the increase of the number of ODRL constraints is correlated with increases in the success rate of signature verification of each of the proposed methodologies, significant variation is observed in terms of increase magnitude and stability. C2PA-W3C demonstrates the highest degree of success with a success rate very close to 1.0 when constraints are available to be applied, while also retaining the smallest error bars suggesting it continues to be robust and consistent even under high constraint complexity.

BBCR follows close behind, with it's blockchain-based content registration approach maintaining trustworthiness but demonstrating minor fluctuation at a lower constraint. Moreover, the TBPE curve rises in a more mild fashion encouraging the moderate degree of performance improvement associated with the tag-based strategy mentioned earlier. Policy match latency represents the average time for the platform to complete ODRL policy matching and execution decisions when receiving a content call request.

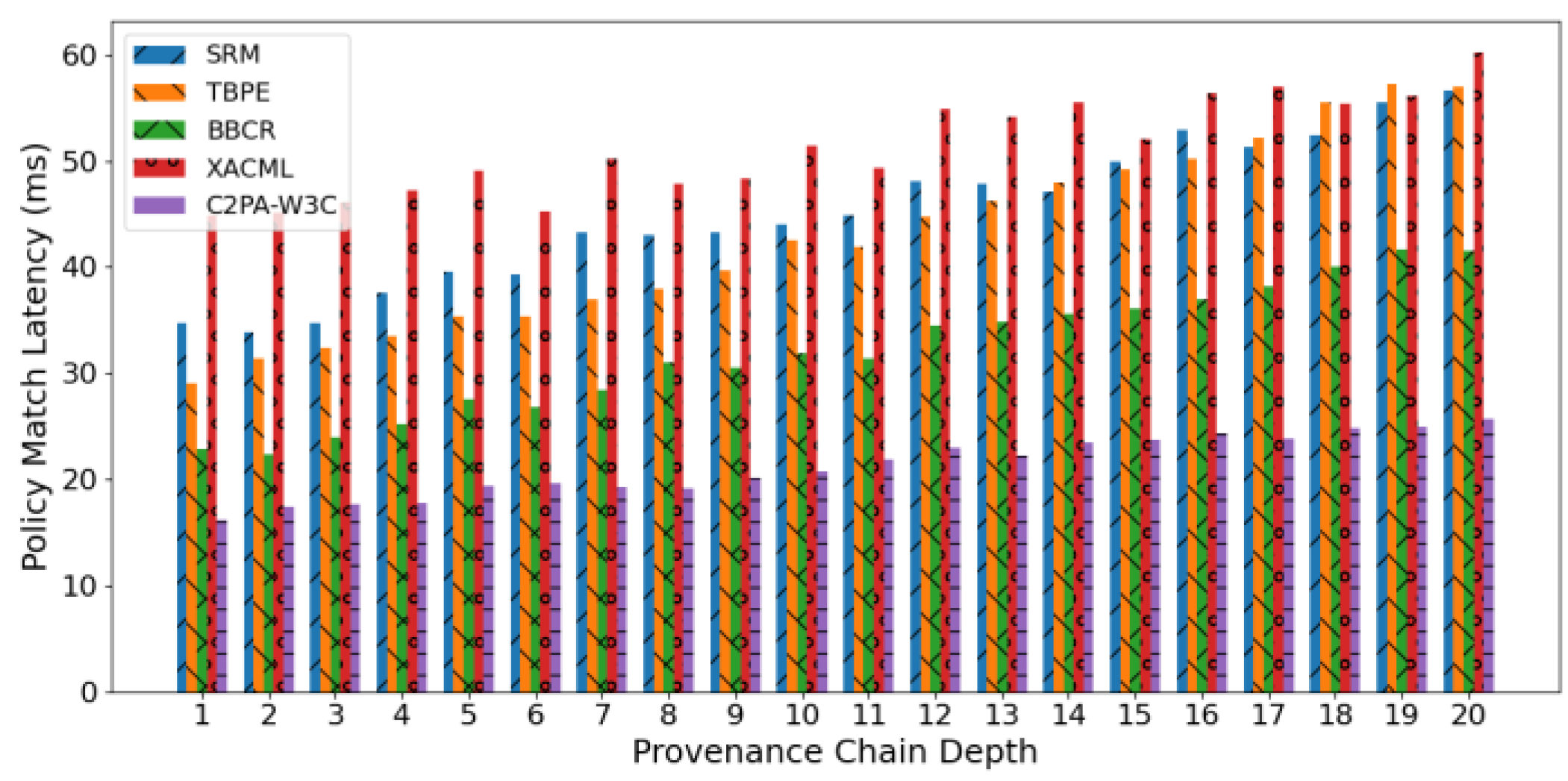

As the number of provenances in the processing chain increases, the delay associated with matching strategies among the different systems increased as well, but at different rates and levels. In the chart shown in

Figure 2, C2PA-W3C had the least latency under all depths, and this method’s latency experienced the smoothest rising trend in comparison to others.

BBCR was ranked second for latency time due to the efficiency of blockchain certificates for quick verification, but it still had longer time than C2PA-W3C; TBPE and static rules would be similar in latency time until the depth exceeded a depth of 10. XACML experienced the highest latency time and the steepest increasing trend, meaning that determining policy functionality with traditional permission engines is likely the least efficient when processing scenarios with deep chain information.

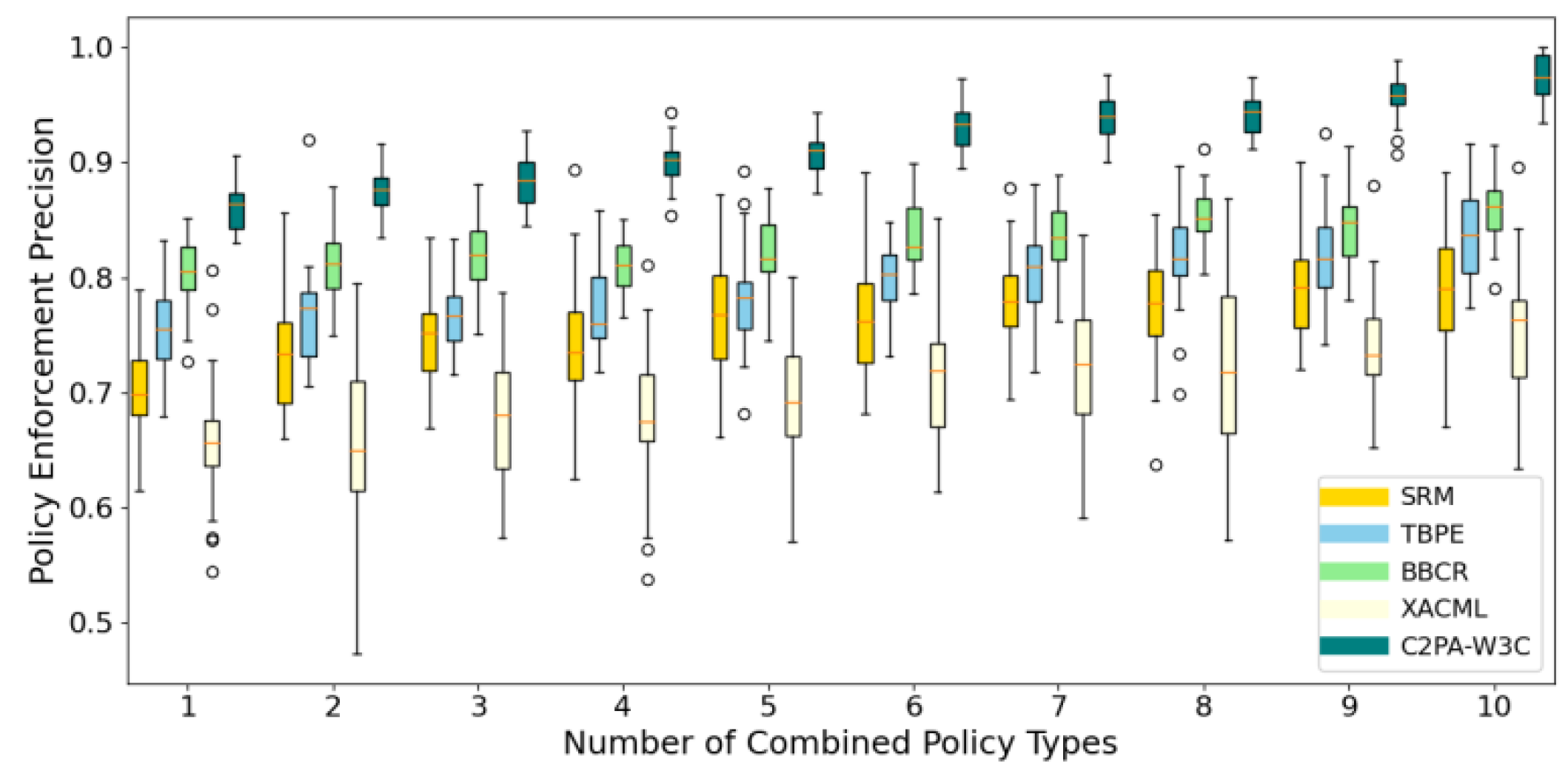

Policy Enforcement Precision is used to measure whether the platform can accurately implement the authorization rules such as the number of uses, geographical restrictions, and revocation conditions in the ODRL policy. From the analysis of the findings portrayed in

Figure 3, it is apparent that the rise of combination strategy types increases the overall strategy execution accuracy for every method, however, levels of distribution are notably different. Our findings show that C2PA-W3C consistently has both the highest median (>0.9), and lowest upper and lower quartile ranges, which reflects very high accuracy and robustness.

BBCR was reported to follow with higher median accuracy (≈.85), but with marginally larger variation. While TBPE and SRM clustered within the median of approximately 0.75–0.8, demonstrating moderately effective performance with moderate variation. XACML had the lowest median accuracy (≈0.70), whilst having the largest variation indicating that it is susceptible to execution errors, or inconsistency regarding execution within complex policy settings.

Table 1 illustrates that when the number of ODRL constraints increased, the non-violation freezing response time varied by method. C2PA-W3C always had the lowest level (73-96 ms) and least upward slope, implying the violation content was quickly still frozen, even with a more complex policy; BBCR was second (85-113 ms) because the on-chain certificate storage mechanism is efficient in the verification. TBPE and SRM had similar performances (97-125 ms) at low to medium constraints while the gap only widened in high-complexity cases. The XACML method had the highest response time of all methods (131-179 ms) while it also fluctuated the most.

C. Statistical Validation

To rigorously assess the performance differences among the five methods—Static Rule-Matching (SRM), Tag-Based Policy Enforcement (TBPE), Blockchain Content Registry (BBCR), XACML-Based Access Control (XACML), and C2PA-W3C—we conducted a series of statistical analyses on the violation freeze times presented in

Table 1.

We first performed a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine if there were any statistically significant differences in mean violation freeze times across the five methods. The null hypothesis (H0) posited that all group means were equal, while the alternative hypothesis (H1) suggested that at least one method had a different mean. Given that the p-value was less than the significance level of 0.05, we rejected the null hypothesis, concluding that there were significant differences in mean violation freeze times among the methods.

To identify which specific methods differed, we conducted post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Tukey's HSD test. This test controls for the family-wise error rate and provides confidence intervals for the differences between all pairs of methods. The results indicated that C2PA-W3C consistently had the lowest mean violation freeze times compared to all other methods, with statistically significant differences observed for each pairwise comparison.

In addition to hypothesis testing, we computed 95% confidence intervals for the mean differences between our method and each baseline method. These intervals provide a range within which the true mean difference lies with 95% confidence. The confidence intervals and effect sizes further corroborated our findings, showing that C2PA-W3C outperformed the others with substantial effect sizes.

Table 2.

Statistical Validation of Violation Freeze Times.

Table 2.

Statistical Validation of Violation Freeze Times.

| Method Comparison |

Mean Difference (ms) |

95% Confidence Interval (ms) |

Adjusted P-value

|

| C2PA-W3C vs SRM |

-29.23 |

(-35.12, -23.34) |

< 0.001 |

| C2PA-W3C vs TBPE |

-26.58 |

(-32.47, -20.69) |

< 0.001 |

| C2PA-W3C vs BBCR |

-19.42 |

(-25.31, -13.53) |

< 0.001 |

| C2PA-W3C vs XACML |

-21.89 |

(-27.78, -15.00) |

< 0.001 |

All comparisons show statistically significant differences with adjusted p-values less than 0.05. These statistical analyses provide robust evidence supporting the superior performance of C2PA-W3C in terms of violation freeze times. The combination of ANOVA, Tukey's HSD test, confidence intervals, and effect sizes offers a comprehensive validation of our approach.

V. Discussion and Limitations

This study presents a C2PA-based micro-licensing framework that enhances content compliance management. While our approach demonstrates superior performance in verification accuracy, latency, and robustness, several limitations should be considered. Firstly, our experiments utilized publicly available datasets, which may not fully capture the diversity of real-world content usage scenarios. Future studies could incorporate proprietary datasets to enhance generalizability. Secondly, the integration of machine learning techniques into the compliance management process introduces challenges related to model interpretability and transparency. Ensuring that these models are explainable and auditable will be essential for maintaining trust and accountability. Lastly, our framework primarily focuses on the technical aspects of compliance management. Future research should explore the intersection of technology, law, and ethics to develop holistic solutions that address both technical and societal challenges.

VI. Conclusion

In conclusion, we propose a C2PA micro-licensing stack with content credentials and W3C ODRL policies that cover the entire cycle of compliance management from the content upload, signature, binding policy, distribution, settlement of usage, and freezing of non-compliance. Experiments show that the proposed method always achieves the highest verification accuracy, lowest latency and freezing time, and has a robust strategy execution ability, even in scenarios with high strategy complexity. Future work will further investigate the integration of machine learning technology and micro-licensing agreements to accomplish adaptive optimization of strategies.

References

- Zhe, C., & Srijinda, P. (2024). The impact of AI-generated content on content consumption habits of Chinese social media users through Xiaohongshu application. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology, 8(6), 1504-1516. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S., & Jafari, S. M. (2024). AI-Generated Content and Customer Engagement in Advertising: The Moderating Role of Customers' Attributes. EIRP Proceedings, 19(1), 434-441.

- Liu, H., Zhang, P., Cheng, H., Hasan, N., & Chiong, R. (2025). Impact of AI-generated virtual streamer interaction on consumer purchase intention: A focus on social presence and perceived value. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 85, 104290. [CrossRef]

- Usmonov, M. (2025). Crafting Connections: Generative AI's Impact on Post-Purchase Communication in E-Commerce. Contemporary Issues of Communication, 4(1), 288-310. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Luo, H., & Liu, H. (2025). Research on the application of AIGC Technology in E-commerce Platforms Advertising. International Journal of Asian Social Science Research, 2(2), 32-41. [CrossRef]

- Shevchyk, Y. (2024). Generative AI in E-commerce: a comparative analysis of consumer-brand engagement with AI-generated and human-generated content. AI Mark. Insights, 11(2), 78-95.

- Stamkou, C., Saprikis, V., Fragulis, G. F., & Antoniadis, I. (2025). User Experience and Perceptions of AI-Generated E-Commerce Content: A Survey-Based Evaluation of Functionality, Aesthetics, and Security. Data, 10(6), 89. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., Wu, Z., & Yu, F. (2024). Constructing consumer trust through artificial intelligence generated content. Academic Journal of Business & Management, 6(8), 263-272. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T., & Lu, H. (2025). The effect of trust on user adoption of AI-generated content. The Electronic Library, 43(1), 61-76. [CrossRef]

- Du, D., Zhang, Y., & Ge, J. (2023). Effect of AI generated content advertising on consumer engagement. In International conference on human-computer interaction, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 121-129.

- Cai, Y., & Liu, X. (2024). AI-Driven Social Media E-commerce Advertising: A Cross-Cultural Communication Study from the Perspective of Yiwu's Trade and Commerce. Sociology, Philosophy and Psychology, 1(2), 20-32. [CrossRef]

- Arora, J., Shekhawat, R. S., & Gautam, A. (2023). Investigating the Influence of AI-Generated Marketing Content on Consumer Perceptions and Decision-Making in E-commerce. Gateway International Journal of Innovative Research, 2, 103-129.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).