1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with vascular pathology including atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis, heterotopic medial calcification and arterial stiffness, which contributes to the progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and increased mortality [

1,

2]. Such changes are due to long-term exposure of uraemic toxins, in addition to traditional risk factors like hypertension and hyperlipidaemia [

3]. Concentrations of the highly protein-bound uraemic toxin indoxyl sulphate (IS) progressively increases with stage of CKD and is associated with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and overall mortality [

4]. IS demonstrates direct cytotoxic effects, altering vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation [

5,

6], senescence [

7], migration [

8] and apoptosis [

9].

Thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) is a secreted matricellular glycoprotein that can interact with numerous cell-surface receptors on various cell types to modulate biological processes such as proliferation, migration, adhesion and inflammation [

10]. Plasma TSP1 expression is upregulated in CKD patients [

11] and high levels are predictive of both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) [

12]. Vascular expression of TSP1 is upregulated in response to injury [

13], shear stress [

14], and disease states including ischemia [

15] and diabetes [

16]. We have previously shown that TSP1 is also increased in IS-treated VSMC [

17].

The high affinity receptor for TSP1 in VSMC is CD47 [

18,

19], with activation at picomolar concentrations. The importance of the TSP1-CD47 signalling axis has been identified in systemic vascular dysfunction [

20] as well as pulmonary arterial hypertension [

21,

22]. However, its role in uraemia-induced vascular pathology has yet to be investigated. Here we report that TSP1 and IS drive vascular proliferation and senescence via CD47-mediated activation of AhR and pERK1/2 pathways in isolated hVSMCs. CD47 deletion protects against CKD-induced vascular remodelling, despite persistent TSP1 upregulation in mice aorta.

3. Discussion

CKD is strongly associated with vascular dysfunction and premature vascular ageing [

37,

38] but the molecular mediators remain incompletely defined. In this study, we have identified TSP1 as a key regulator of uremic vascular changes. We demonstrate that both TSP1 and the uremic toxin IS consistently reduced VSMC proliferation and induced senescence. TSP1 expression in VSMCs was also induced by IS, as well as by plasma from patients with CKD, putatively containing both IS and TSP1. Our mechanistic studies revealed that both IS and TSP1 increased AhR expression and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in VMSC. The biphasic effect of IS—possibly due to altered nuclear/cytoplasmic trafficking of AhR—remains to be determined. Blockade of CD47—the high affinity TSP1 receptor—attenuated senescence and ERK activation, supporting the notion of CD47 as a critical mediator. These findings highlight TSP1 as a driver of uremic signalling and a key therapeutic target.

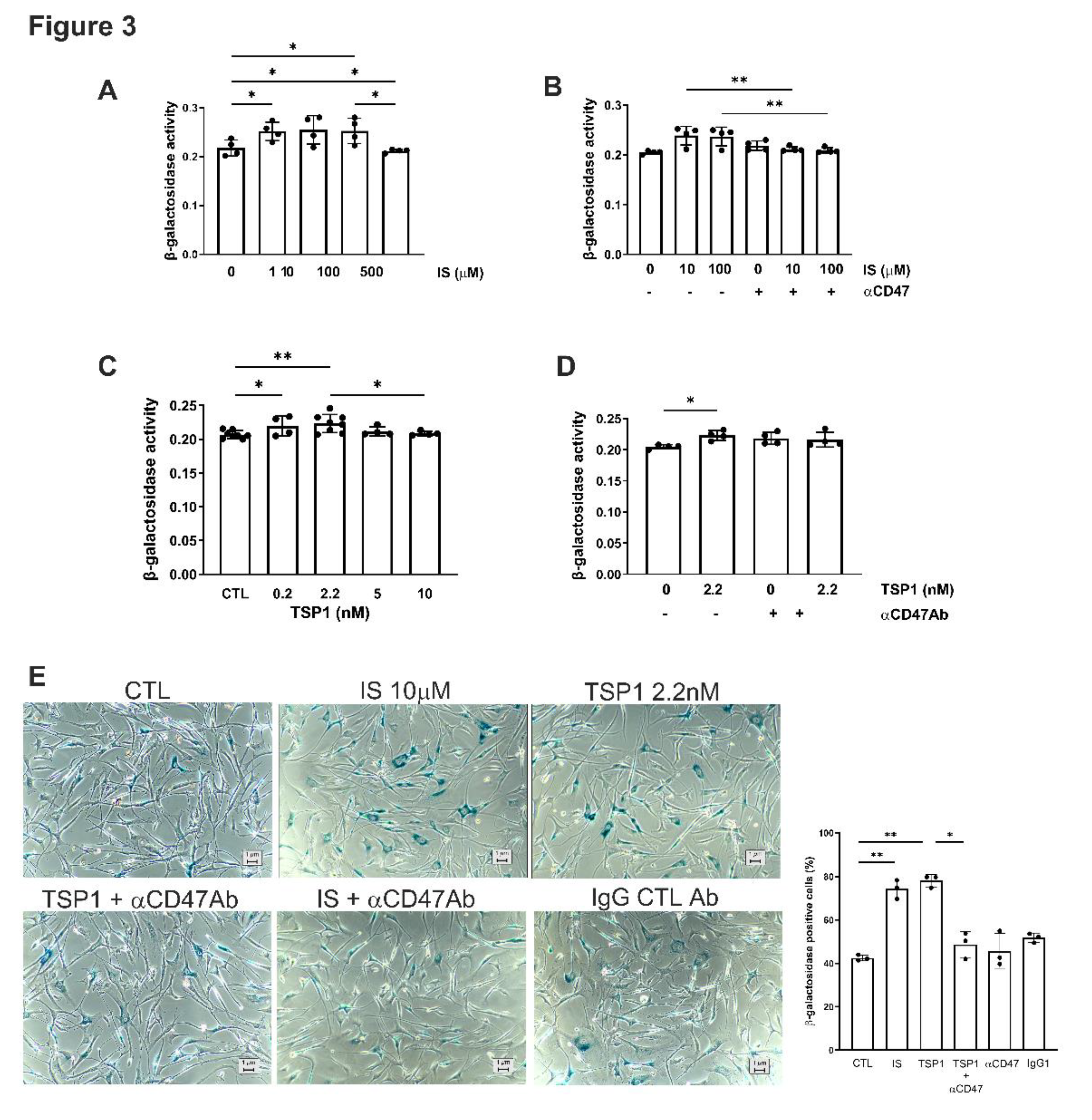

Although ERK is classically associated with mitogenic signalling [

39], sustained activation can instead trigger cell-cycle arrest and/or senescence [

40]. The amplitude and duration of ERK signalling are key determinants: moderate activation promotes cell-cycle entry, whereas strong or prolonged signalling induces p53, p21 and p27 expression, as well as growth arrest in different cell types [

40,

41]. Our finding that TSP1- and IS-induced ERK activation reduced proliferation and increased senescence in VMSCs is in keeping with these findings.

Our 5/6Nx model yielded divergent vascular responses. In thoracic aortae, CKD increased total ERK1/2 expression but decreased activation (phospho-ERK) in both WT and CD47KO mice. This may reflect nuclear translocation of ERK1/2 [

42,

43] or the influence of additional vascular wall intercellular signalling. We observed a biphasic response in cytoplasmic AhR expression in VSMC, but no corresponding activation of ERK1/2 expression. The effect of IS on ERK1/2 activation is variable and context-dependent, with some studies showing it enhances or has no effect and others demonstrating inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation, depending on the cell type and cell culture conditions, requiring additional pro-inflammatory cytokines [

44] or variable IS concentrations [

45]. IS has been shown to activate ERK1/2 in renal proximal tubular cells [

46] and VSMCs [

47], while inhibiting it at higher concentrations in osteoblast-like cells [

48]. These discrepancies highlight the complexity of uremic signalling in the intact vascular wall, where gradients of toxins (IS), matrix proteins (TSP1), and receptor expression influence responses.

3.1. Study Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our in vitro experiments were performed in isolated hVSMCs, which may not fully capture the multicellular interactions that occur within the vessel wall. Endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and infiltrating immune cells are likely to influence TSP1 signalling and senescence. Second, the concentrations of IS and TSP1 used in vitro may not precisely reflect the in vivo milieu, where toxin accumulation and spatial gradients are dynamic and patient-dependent. Third, we used global CD47-deficient mice, and cell-type–specific roles of CD47 remain to be defined. Fourth, ERK1/2 activation was measured in bulk vascular tissue, which may obscure cell-specific differences in signalling. Finally, the demographic characteristics of patients and their serum concentrations of IS and TSP1 are unknown, which may account for the variability in cytoplasmic AhR expression induced by serum in hVSMCs.

3.2. Clinical Perspectives

Despite these limitations, our findings provide novel insights with direct clinical implications. By linking IS to increased TSP1 expression and identifying a CD47–AhR–ERK signalling pathway that drives VSMC senescence, we propose a potential mechanism underlying vascular remodelling and premature vascular aging in CKD. Consistent with this, we observed overexpression of p27 and p53 in CKD aortae. Senescent VSMCs lose contractile function, secrete extracellular matrix, and promote fibrosis, collectively contributing to heightened cardiovascular risk.

Currently, therapies targeting vascular aging in CKD are limited. Our results suggest that blocking TSP1 or CD47-dependent signalling could mitigate vascular senescence and remodelling. Given the availability of experimental CD47-blocking antibodies and the development of small-molecule inhibitors, translational opportunities are emerging. Furthermore, circulating TSP1 may serve as a biomarker of CKD [

11], and perhaps also vascular risk, complementing existing markers of uremic toxicity. Thus, targeting TSP1-driven signalling may represent a novel strategy to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease in CKD patients.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

CD47KO (B6.129S7-Cd47tm1Fpl/J) mice on a C57BL/6J background (back-crossed for 15 generations) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory, then bred and housed at Australian Bioresources (ABR, Sydney, Australia). Age-matched (6-8 weeks old) male littermate control (wild-type, WT) mice purchased from ABR and homozygous CD47KO mice were transferred to the Westmead Institute for Medical Research and allowed to acclimatise for 2 weeks prior to study commencement. Mice were housed in the biological facility under 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to standard chow and water. Animal studies were performed under approved protocols (Western Sydney Local Health District #4304, #4281 and University of Sydney #1594, #2022/2028) and in accordance with the Australian code for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes (National Health and Medical Research Council).

4.2. CKD Model

Age-matched (8-10 weeks old) mice were randomly assigned to sham and 5/6 nephrectomy groups (5/6Nx). The 5/6Nx model was performed as previously described [

23,

24]. Briefly, mice were anaesthetised with isoflurane and oxygen. In the 5/6Nx group, a left 2/3 nephrectomy was firstly performed by cutting the upper and lower pole of the left kidney with iris scissors, followed by a total right nephrectomy 7 days later. The sham groups were similarly anaesthetised and kidneys exposed but not resected. All mice were assessed weekly for body weight and blood pressure using tail-cuff plethysmography (CODA machine, Kent Scientific Corporation, Connecticut, USA). Metabolic caging was performed at week 10 and mice were euthanised at week 12. Organs, plasma and urine were collected and stored at -80°C. The percentage of kidney excised was calculated by the following formula: % of removed kidney = weight of excised kidney (left excised kidney + right kidney) *100/ total weight (left excised kidney + left remnant kidney + right kidney).

4.3. Measurement of Renal Function

Plasma urea and creatinine, as well as urinary protein and creatinine were measured using the Siemens Atellica System (Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research, Westmead Hospital, New South Wales, Australia).

4.4. Aorta and Kidney Histopathology

Formalin-fixed kidney and thoracic aorta were embedded in paraffin and cut into 4 μm sections for histology. Slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in ethanol prior to staining. Following staining, slides were rehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, cover slipped with mounting media and left to dry overnight prior to imaging.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining: slides were stained with Mayer’s haematoxylin for 3 minutes, Scott’s solution for 1 minute and counterstained with eosin for 2 minutes.

Picrosirius red staining (for collagen): slides were incubated in picrosirius red staining solution for 1 hour and washed in acidified water.

Verhoeff-Van Gieson staining (for elastic fibres): slides were incubated with Verhoeff staining solution for 25 minutes, rinsed in water then differentiated with 2% aqueous ferric chloride and counterstained with Van Gieson solution (POCD Scientific, Australia).

Von Kossa staining (for calcification): slides were incubated with 1% silver nitrate under UV light for 30 minutes, followed by 5% sodium thiosulfate for 5 minutes prior to counterstaining with nuclear fast red solution for 5 minutes.

4.5. Immunohistochemistry

Four (4) μm sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded mouse thoracic aorta were incubated with rabbit anti-TSP1 antibody (15ug/ml, ab85762, Abcam). EnVision+ System-HRP Labelled Polymer anti-Rabbit secondary antibody (K4003, Dako) and ImmPACT NovaRED® Substrate Kit Peroxidase (HRP) (SK-4805, Dako) were used for immunodetection. Slides were counterstained with Mayer’s haematoxylin and Scott’s Blue solution.

4.6. Immunofluorescence

Cells were grown on glass bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) and TSP1 (2.2 nM) was added for 24 hours [

11]. Permeabilization was performed with PBS/10% BSA/0.1% Triton-X100 for 10 minutes at room temperature followed by blocking with 1% goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes. Cells were incubated in primary antibody (1:100 dilution) in blocking buffer in a humidified chamber at 4°C overnight. Cells were washed then incubated with AF488 secondary antibody (1:400 dilution, Invitrogen) for 1 hour. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Cells were coverslipped with Gelvatol mounting media. Images were captured with an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and results calculated as the percentage of area stained using ImageJ (National Institutes for Health).

4.7. Slide Imaging and Analysis

Slides were scanned under brightfield conditions using Nanozoomer Slide scanner (Hamamatsu, Japan) and viewed on NDP.view2 (Hamamatsu, Japan). Image analysis was conducted using ImageJ. Medial, adventitial and total wall thickness was measured at 5 randomly selected locations and the average calculated. The percentage of medial and adventitial fibrosis was assessed by taking the average of picrosirius red staining of collagen in 5 randomly selected high-power fields at 80X magnification per specimen as per previously published methods [

25].

4.8. Human Plasma Collection

Human plasma collection and study was performed under protocols approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Western Sydney Local Health District [LNR/12/WMEAD114 and LNRSSA/12/WMEAD/117(3503)]. Patients without intercurrent illness or acute kidney injury were recruited from outpatient clinics and provided written consent. Plasma samples were obtained from patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >90ml/min/1.73m2 (control) and those with stage 5 CKD (eGFR <15ml/min). Blood was collected in EDTA tubes using a 23-guage needle and without a tourniquet. Tubes were placed immediately on ice then centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C without brake to generate platelet-poor plasma, which was stored at -80°C until use.

4.9. Cell Culture

Human aortic smooth muscle cells (hVSMCs) (CC-2571, Clonetics, Lonza) were cultured in SmBM™ basal medium (CC-3181, Lonza) supplemented with SmGM™-2 SingleQuots growth supplements (CC-4149, Lonza). Cells were subcultured according to manufacturer instructions. Cells were used at passages 3-6 when at ~70% confluency in 6-well plates. Serum-starved cells were treated with recombinant human TSP1 (0.2-10nM, Athens Research and Technology), IS (1-500 μM, I3875, Sigma Aldrich) or 5% human plasma for 24 hours. In some experiments, cells were pre-treated with anti-CD47 antibody (B6H12) (#14-0479-82, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 minutes.

4.10. Cell Proliferation and Senescence Assays

Cells were seeded into a 96-well microplate (10

4 cells/well). Serum-starved cells were treated with human plasma, TSP1 or IS for 24 or 48 hours as indicated. In some experiments, cells were pre-treated with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes. Cell proliferation and senescence were measured using XTT Cell Viability Kit (#9095, Cell Signaling) and Mammalian β-Galactosidase Assay Kit (75707, Thermo Fisher Scientific), respectively. Absorbance was measured using SpectraMax iD5 Plate Reader (Molecular Devices) at 450nm for cell proliferation and 405nm for cell senescence [

23]. In additional experiments, cells were seeded onto 4-well glass slides (10

4 cells/slide) and stained using a senescence β-galactosidase staining kit (#9680, Cell Signalling Technology) as per manufacturer instructions. Mouse IgG1 kappa isotype control (17-4714-42, eBioscience) was used. Cells were examined under a bright-field microscope (Olympus CKX53, Evidence Scientific, Tokyo, Japan) and five random images were captured per slide for β-galactosidase-positive (blue) cells.

4.11. Western Blotting

Mouse thoracic aortic tissue or human aortic smooth muscle cells were homogenised in RIPA buffer (#9806, Cell Signaling) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmpleteTM ULTRA Tablets 5892970001, Roche) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (PhosSTOPTM 4906845001, Roche). Protein concentration was measured using DC protein assay (Biorad) then resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes by Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Biorad). Membranes were blocked with Intercept® Blocking Buffer (927-60001, LICORbio) and probed at 4°C overnight with the following primary antibodies: phospho-p44/42 MAPK (pERK1/2, #4370), p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2, #9107), β-actin (#4970), vinculin (#13901), AhR (#83200), tumor protein p53 (p53) (#2524) and p27Kip1 (#3698) from Cell Signaling and TSP1 (ab85762) from Abcam. IRDye 800CW and 680RD secondary antibodies (LI-COR) were used and protein was visualised using Odyssey CLx Imaging System (LICORbio). Protein band intensity was measured using ImageJ and expressed relative to loading controls, vinculin or β-actin.

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 10.2.3 (GraphPad Software Inc). Data are presented as mean ± SD. Unpaired t-test (2 comparator groups) or one-way or two-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s and Holm-Sidak post hoc test or Fishers Least Significant Difference test (>2 comparator groups) was used. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

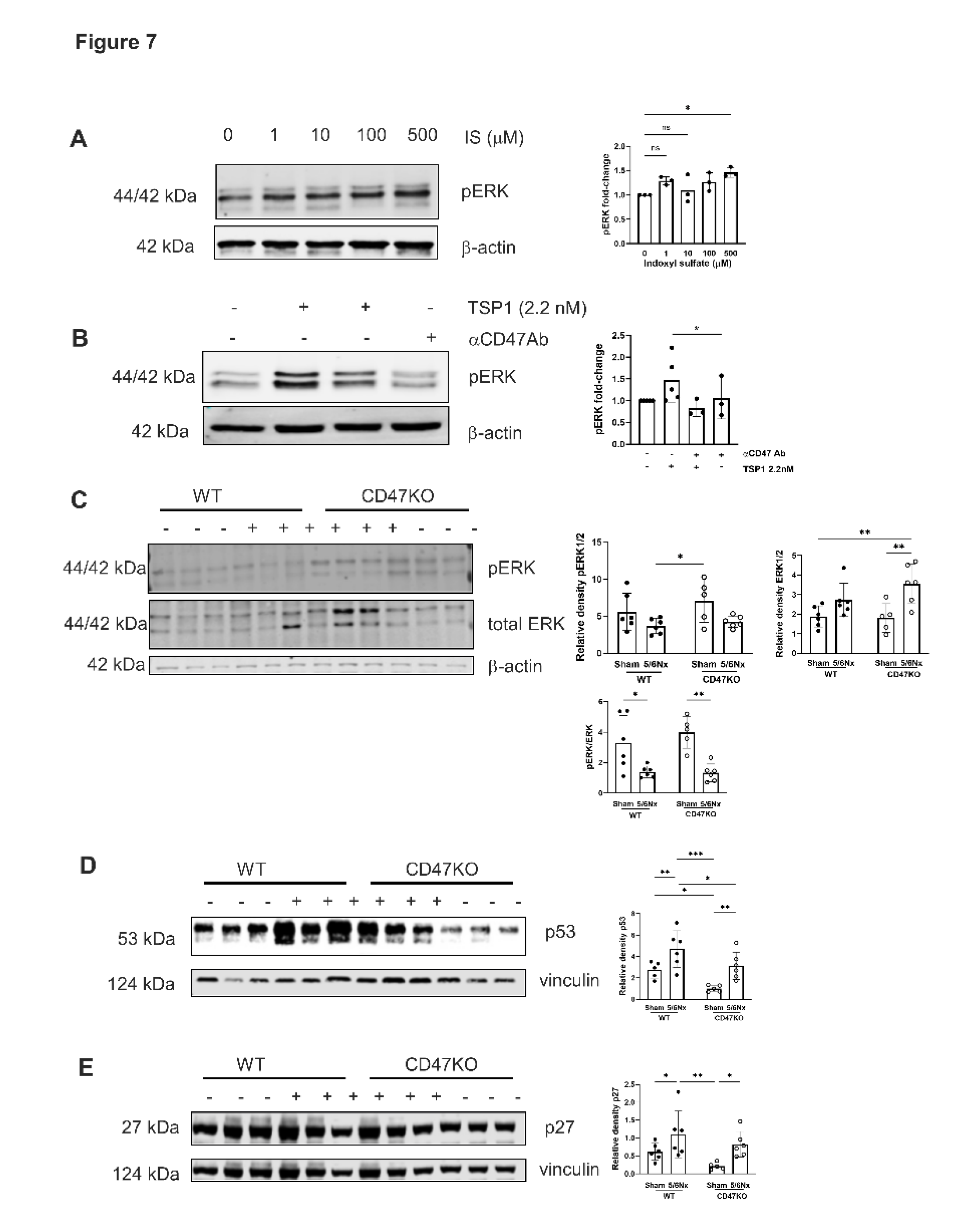

Figure 1.

Exogenous TSP1, indoxyl sulfate and CKD patient plasma promote endogenous TSP1 expression in VSMC. hVSMC were treated with (A) TSP1 (0, 0.2, 2.2, 5 and 10nM) (n=3-4), (B) IS (0, 1, 10, 100 and 500µM) (n=3) or (C) 5% human plasma from patients with or without CKD (n=3-5) for 24h. Whole cell lysates were probed for TSP1. All data shown are mean ± SD. Representative Western blots and combined densitometry relative to β-actin or vinculin are shown. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 by one-way analysis of variance with Sidak’s post-hoc test (A), Fishers Least Significant Difference Test (B) or Tukey’s post-hoc test (C). Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; CTL, control; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; TSP1, thrombospondin 1.

Figure 1.

Exogenous TSP1, indoxyl sulfate and CKD patient plasma promote endogenous TSP1 expression in VSMC. hVSMC were treated with (A) TSP1 (0, 0.2, 2.2, 5 and 10nM) (n=3-4), (B) IS (0, 1, 10, 100 and 500µM) (n=3) or (C) 5% human plasma from patients with or without CKD (n=3-5) for 24h. Whole cell lysates were probed for TSP1. All data shown are mean ± SD. Representative Western blots and combined densitometry relative to β-actin or vinculin are shown. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 by one-way analysis of variance with Sidak’s post-hoc test (A), Fishers Least Significant Difference Test (B) or Tukey’s post-hoc test (C). Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; CTL, control; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; TSP1, thrombospondin 1.

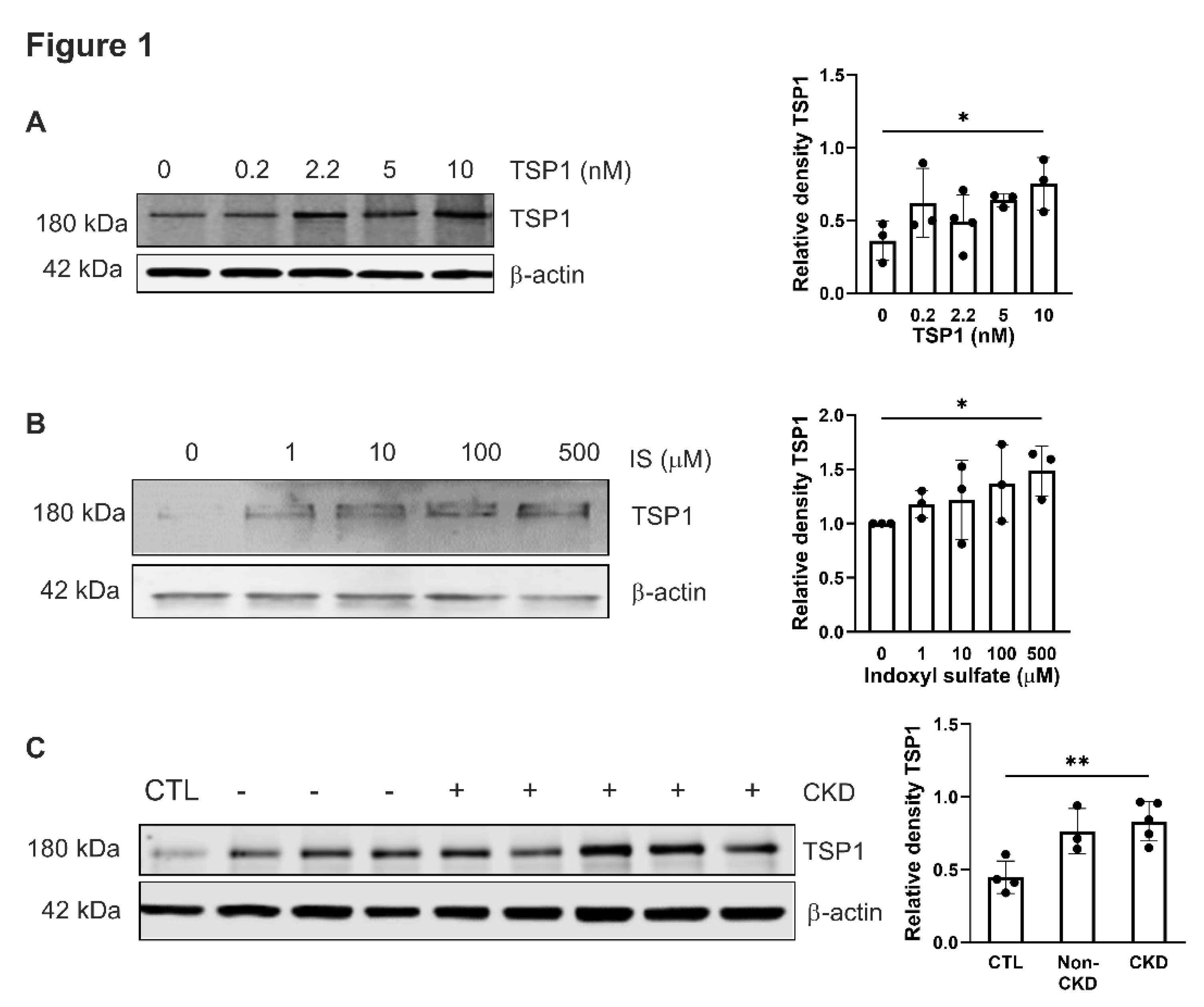

Figure 2.

TSP1and indoxyl sulfate limits VSMC proliferation via CD47. hVSMC cell viability was measured by assessing reduction of tetrazolium salt sodium 3’- [1- [(phenylamino)-carbonyl]-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis(4-methoxy-6- nitro)benzene-sulfonic acid hydrate (XTT) and measuring absorbance at 450nm in cells after 48h treatment with (A) TSP1 (0, 0.2, 2.2, 5, 10nM) (n=4), (B) TSP1 2.2nM ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes (n=6), (C) IS (0, 1, 10, 100, 500µM) (n=4) or (D) IS (100, 500µM) ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes (n=4-8) (D). All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ****P<0.0001 by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test (A, C) or Fishers Least Significant Difference test (B, D). Abbreviations: ⍺CD47, anti-CD47 antibody; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; TSP1, thrombospondin 1.

Figure 2.

TSP1and indoxyl sulfate limits VSMC proliferation via CD47. hVSMC cell viability was measured by assessing reduction of tetrazolium salt sodium 3’- [1- [(phenylamino)-carbonyl]-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis(4-methoxy-6- nitro)benzene-sulfonic acid hydrate (XTT) and measuring absorbance at 450nm in cells after 48h treatment with (A) TSP1 (0, 0.2, 2.2, 5, 10nM) (n=4), (B) TSP1 2.2nM ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes (n=6), (C) IS (0, 1, 10, 100, 500µM) (n=4) or (D) IS (100, 500µM) ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes (n=4-8) (D). All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ****P<0.0001 by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test (A, C) or Fishers Least Significant Difference test (B, D). Abbreviations: ⍺CD47, anti-CD47 antibody; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; TSP1, thrombospondin 1.

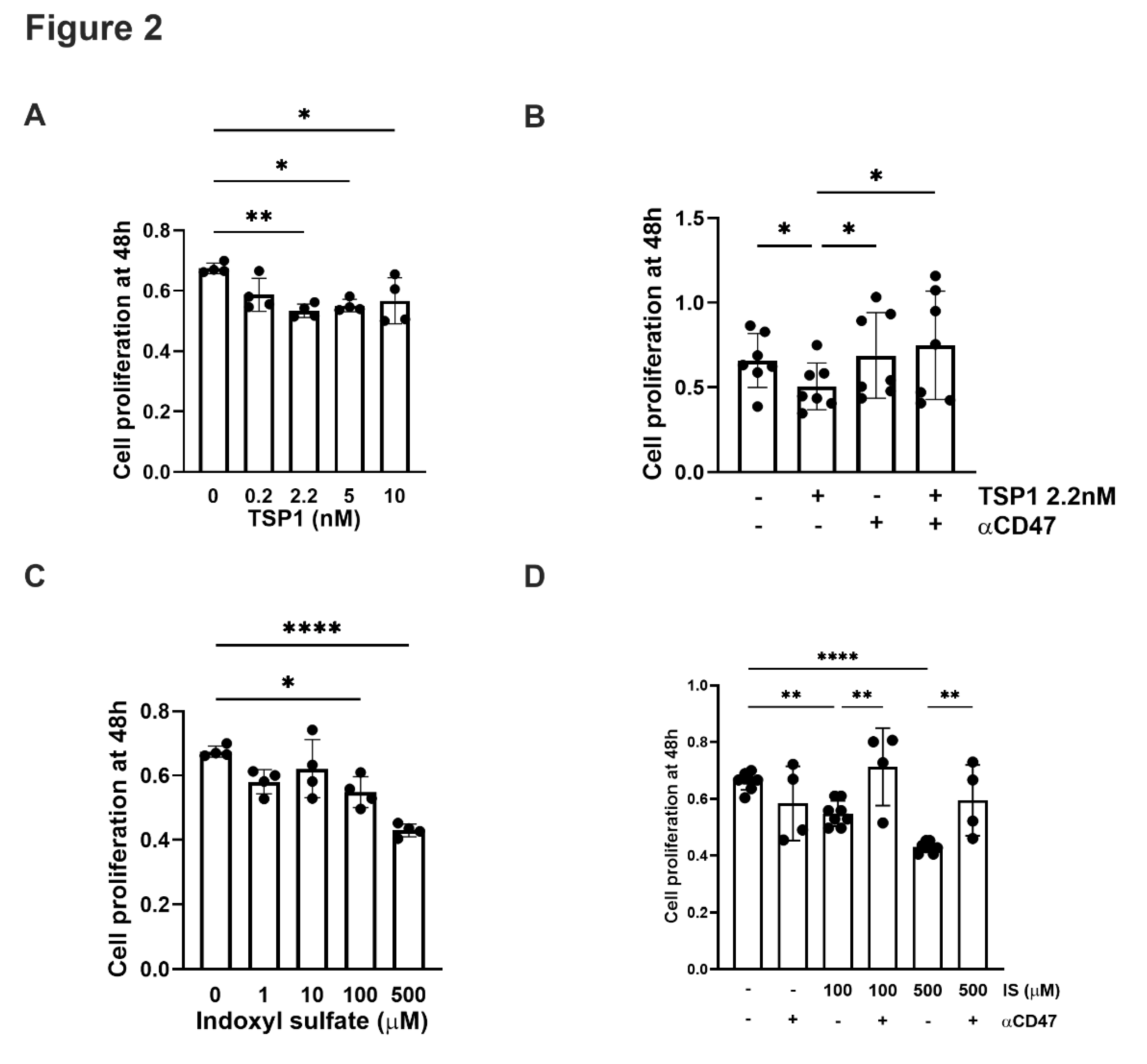

Figure 3.

TSP1 and indoxyl sulfate changes VSMC senescence via CD47. hVSMC senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity after 48h treatment with (A) IS (0, 1, 10, 100, 500µM) (n=4), (B) IS (10, 100µM) ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes, (C) TSP1 (0, 0.2, 2.2, 5, 10nM) (n=4-7), or (D) TSP1 2.2nM ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes (n=4). Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining of hVSMC following incubation with basal media (CTL), IS 10µM (± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes), TSP1 2.2nM (± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes) and IgG isotype control antibody (n=3). All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05, and **P<0.01 by one-way analysis of variance with Fishers Least Significant Difference test (A, C, E), Sidak’s post-hoc test (B) or Dunn’s post-hoc test (D). Abbreviations: ⍺CD47Ab, anti-CD47 antibody; CTL, control; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; TSP1, thrombospondin 1.

Figure 3.

TSP1 and indoxyl sulfate changes VSMC senescence via CD47. hVSMC senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity after 48h treatment with (A) IS (0, 1, 10, 100, 500µM) (n=4), (B) IS (10, 100µM) ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes, (C) TSP1 (0, 0.2, 2.2, 5, 10nM) (n=4-7), or (D) TSP1 2.2nM ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes (n=4). Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining of hVSMC following incubation with basal media (CTL), IS 10µM (± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes), TSP1 2.2nM (± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes) and IgG isotype control antibody (n=3). All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05, and **P<0.01 by one-way analysis of variance with Fishers Least Significant Difference test (A, C, E), Sidak’s post-hoc test (B) or Dunn’s post-hoc test (D). Abbreviations: ⍺CD47Ab, anti-CD47 antibody; CTL, control; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; TSP1, thrombospondin 1.

Figure 4.

TSP1 activates AhR in VSMC via CD47. hVSMC were treated with (A) IS (0, 1, 10, 100, 500µM) (n=3-4) or (B) 5% human plasma from patients with or without CKD (n=3-5) for 24h. Whole cell lysates were probed for AhR. Representative Western blots and combined densitometry relative to β-actin or vinculin are shown. (C) hVSMC treated with TSP1 2.2nM were stained for AhR (green) and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) (Magnification=40x, Scale bar=80 pixels). Percentage and intensity of cytoplasmic and nuclear staining was measured (n=7-8). All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test (A, B) or Fishers Least Significant Test (D) and unpaired Student’s t-test (C). Abbreviations: AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; CKD, chronic kidney disease; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; TSP1, thrombospondin-1.

Figure 4.

TSP1 activates AhR in VSMC via CD47. hVSMC were treated with (A) IS (0, 1, 10, 100, 500µM) (n=3-4) or (B) 5% human plasma from patients with or without CKD (n=3-5) for 24h. Whole cell lysates were probed for AhR. Representative Western blots and combined densitometry relative to β-actin or vinculin are shown. (C) hVSMC treated with TSP1 2.2nM were stained for AhR (green) and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) (Magnification=40x, Scale bar=80 pixels). Percentage and intensity of cytoplasmic and nuclear staining was measured (n=7-8). All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test (A, B) or Fishers Least Significant Test (D) and unpaired Student’s t-test (C). Abbreviations: AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; CKD, chronic kidney disease; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; TSP1, thrombospondin-1.

Figure 5.

Establishing equivalent CDK in WT and CD47KO mice. WT and CD47KO mice were subjected to 5/6Nx or sham surgery. (A) Percentage of kidney excised following 5/6Nx (n=4-5). (B) Fold-change in body weight over 12 weeks (n=3-5). (C) Serum urea and creatinine at 12 weeks post-surgery (n=4-5). (D) Urine volume, urine creatinine to plasma creatinine ratio and urine protein to creatinine ratio at 12 weeks (n=3-5). (E) Representative haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded kidney excised at 12 weeks following 5/6Nx or sham surgery (bar=100µM). All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 by unpaired Student’s t-test (A) or 2-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test (B to D). Abbreviations: 5/6Nx, 5/6-nephrectomy; AUC, area under the curve; CD47KO, CD47 knockout; Cr, creatinine; PCR, protein to creatinine ratio; WT, wild-type.

Figure 5.

Establishing equivalent CDK in WT and CD47KO mice. WT and CD47KO mice were subjected to 5/6Nx or sham surgery. (A) Percentage of kidney excised following 5/6Nx (n=4-5). (B) Fold-change in body weight over 12 weeks (n=3-5). (C) Serum urea and creatinine at 12 weeks post-surgery (n=4-5). (D) Urine volume, urine creatinine to plasma creatinine ratio and urine protein to creatinine ratio at 12 weeks (n=3-5). (E) Representative haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded kidney excised at 12 weeks following 5/6Nx or sham surgery (bar=100µM). All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 by unpaired Student’s t-test (A) or 2-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc test (B to D). Abbreviations: 5/6Nx, 5/6-nephrectomy; AUC, area under the curve; CD47KO, CD47 knockout; Cr, creatinine; PCR, protein to creatinine ratio; WT, wild-type.

Figure 6.

Development of CRS in mice upregulates aortic TSP1 expression. (A) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for TSP1 in formalin-fixed paraffin embedded mouse thoracic aorta. Scale bar = 50µm. (B) Mouse thoracic aorta homogenates obtained at 12 weeks following 5/6Nx or sham-surgery were analysed by Western Blotting for expression of TSP1 (n=5-6 per group). Representative Western blots and combined densitometry relative to vinculin are shown. (C) Representative images of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded mouse thoracic aorta 12 weeks following 5/6Nx or sham surgery with (i) haematoxylin-eosin, (ii) picrosirius red, (iii) Verhoeff-van Gieson and (iv) von Kossa staining. Calcified human carotid atheromatous plaque was used as a positive control. Scale bar = 50µm. Total aorta thickness (D), adventitia thickness (E) media thickness (F) was measured at 5 randomly selected areas per mouse and averaged (n=4/group). (G) Collagen deposition in the aortic adventitia and media was quantified from 5 randomly selected areas per mouse and averaged (n=4/group) in picrosirius-red stained sections. All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 by 2-way analysis of variance with Fisher’s Least SignificantTest (A) or Tukey’s post hoc test (D-H). Abbreviations: 5/6Nx, 5/6 nephrectomy.

Figure 6.

Development of CRS in mice upregulates aortic TSP1 expression. (A) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for TSP1 in formalin-fixed paraffin embedded mouse thoracic aorta. Scale bar = 50µm. (B) Mouse thoracic aorta homogenates obtained at 12 weeks following 5/6Nx or sham-surgery were analysed by Western Blotting for expression of TSP1 (n=5-6 per group). Representative Western blots and combined densitometry relative to vinculin are shown. (C) Representative images of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded mouse thoracic aorta 12 weeks following 5/6Nx or sham surgery with (i) haematoxylin-eosin, (ii) picrosirius red, (iii) Verhoeff-van Gieson and (iv) von Kossa staining. Calcified human carotid atheromatous plaque was used as a positive control. Scale bar = 50µm. Total aorta thickness (D), adventitia thickness (E) media thickness (F) was measured at 5 randomly selected areas per mouse and averaged (n=4/group). (G) Collagen deposition in the aortic adventitia and media was quantified from 5 randomly selected areas per mouse and averaged (n=4/group) in picrosirius-red stained sections. All data shown are mean ± SD. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 by 2-way analysis of variance with Fisher’s Least SignificantTest (A) or Tukey’s post hoc test (D-H). Abbreviations: 5/6Nx, 5/6 nephrectomy.

Figure 7.

MAPK ERK signalling is activated by TSP1 and IS via CD47. hVSMC were treated for 24h with (A) IS (0, 1, 10, 100 and 500µM) (n=3) or (B) TSP1 2.2nM ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes (n=3-5). Whole cell lysates were probed for pERK. Mouse thoracic aorta homogenates obtained at 12 weeks following 5/6Nx or sham-surgery were analysed by Western Blotting for expression of pERK (C), p53 (D) and p27 (E) (n=5-6/group). All data shown are mean ± SD. Representative Western blots and combined densitometry relative to β-actin or vinculin are shown. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test (A) or Sidak’s post-hoc test (B) and 2-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test (B, C, D) or Holm-Sidak’s post-hoc test (E). Abbreviations: ⍺CD47Ab, anti-CD47 antibody; CD47KO, CD47 knockout; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; pERK, phosphorylated extracellular regulated kinase; TSP1, thrombospondin-1; WT, wild-type.

Figure 7.

MAPK ERK signalling is activated by TSP1 and IS via CD47. hVSMC were treated for 24h with (A) IS (0, 1, 10, 100 and 500µM) (n=3) or (B) TSP1 2.2nM ± pre-treatment with anti-CD47 antibody for 30 minutes (n=3-5). Whole cell lysates were probed for pERK. Mouse thoracic aorta homogenates obtained at 12 weeks following 5/6Nx or sham-surgery were analysed by Western Blotting for expression of pERK (C), p53 (D) and p27 (E) (n=5-6/group). All data shown are mean ± SD. Representative Western blots and combined densitometry relative to β-actin or vinculin are shown. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test (A) or Sidak’s post-hoc test (B) and 2-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-hoc test (B, C, D) or Holm-Sidak’s post-hoc test (E). Abbreviations: ⍺CD47Ab, anti-CD47 antibody; CD47KO, CD47 knockout; hVSMC, human aortic vascular smooth muscle cells; IS, indoxyl sulfate; pERK, phosphorylated extracellular regulated kinase; TSP1, thrombospondin-1; WT, wild-type.