Submitted:

21 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Research Problem

1.3. Research Questions

- How do spatial inequalities, gender vulnerabilities, and climate shocks interact to influence inclusive growth in Bangladesh?

- Can redistributive policies—such as wealth taxation and adaptive social protection—support structural transformation while sustaining economic growth?

1.4. Contributions

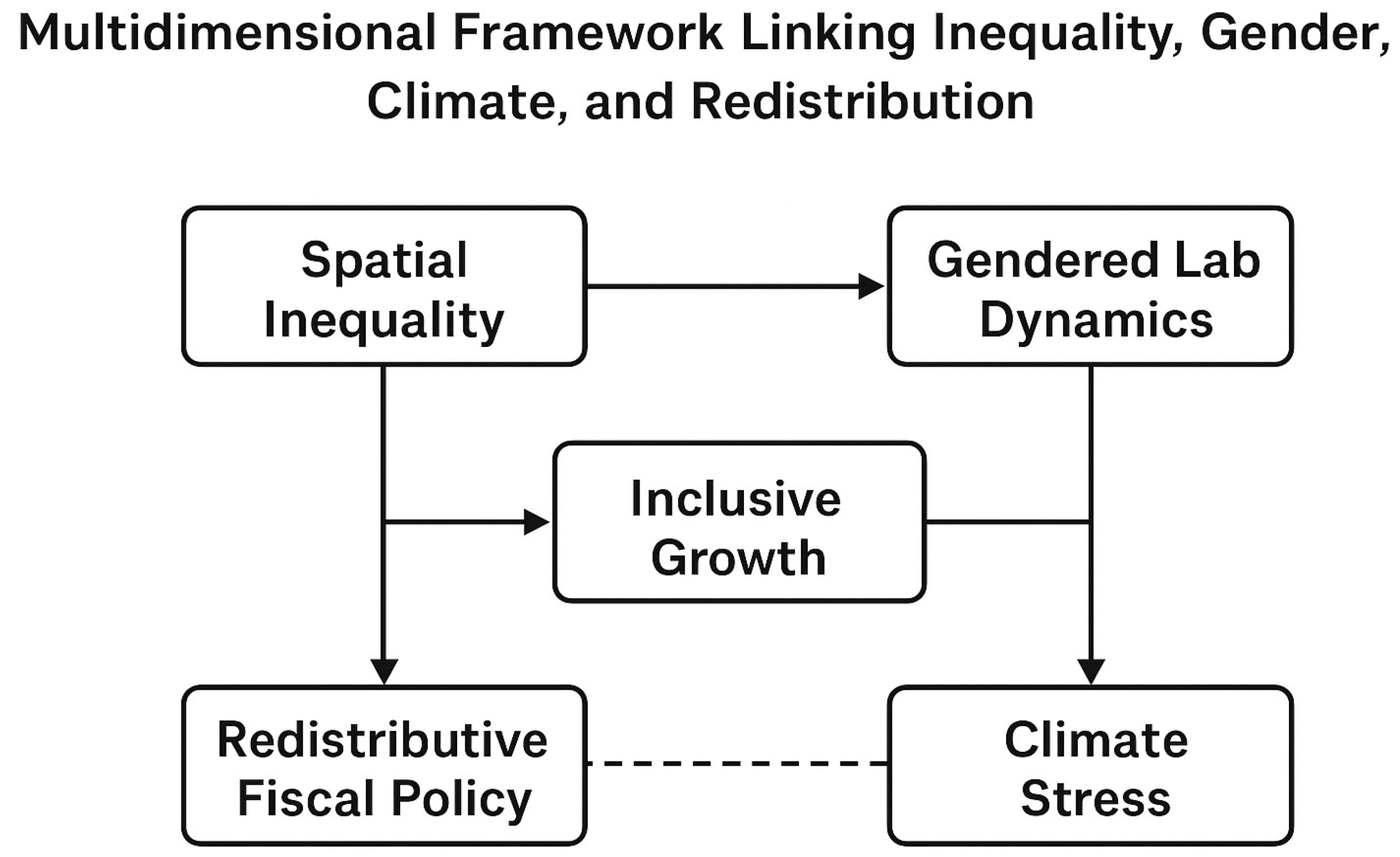

- Conceptual and theoretical innovation: It proposes a multidimensional framework that links spatial inequality, gendered labor dynamics under climate stress, and redistributive fiscal policy in a unified analysis of inclusive growth. This challenges the conventional assumption that growth will “trickle down” to reduce inequality and argues that well-designed redistribution can accelerate, rather than hinder, structural transformation [7,12].

- Empirical novelty: Unlike most existing studies that analyze spatial inequality, gender exclusion, or climate vulnerability in isolation, this paper integrates all three dimensions into a unified analytical framework. To our knowledge, it is the first study to provide causal evidence on the climate–gender nexus in Bangladesh’s labor market and to simulate the redistributive potential of wealth taxation for financing inclusive growth. Empirically, it constructs a district-level inequality index showing that 42% of variation in development outcomes is explained by spatial disparities; provides the first causal estimate of climate shocks on women’s labor force participation in Bangladesh (a decline of 11.3 percentage points per major disaster, versus 3.1 points for men); and uses a dynamic computable general equilibrium (CGE) simulation to show that even a modest wealth tax (0.5–2.5%) could finance universal secondary education by 2035 without compromising macroeconomic stability.

- Policy relevance: It proposes a three-pillar strategy to make growth more inclusive and sustainable: (i) productive inclusion through Industry 4.0 and climate adaptation skills, (ii) spatial rebalancing via upazila-specific special economic zones (SEZs), and (iii) adaptive social protection systems supported by digital platforms. Simulations suggest this package could reduce the Gini coefficient by 0.07 while maintaining GDP growth above 6%.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theories of Inequality and Growth

2.2. Spatial Inequality and Structural Transformation

2.3. Gender Inequality, Climate Vulnerability, and Inclusive Growth

2.4. Fiscal Redistribution and Structural Transformation

2.5. Gaps and Positioning

| Theme | Key Findings in Literature | Gaps Identified | This Study’s Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Inequality | Economic growth is highly concentrated in the Dhaka–Chattogram corridor; peripheral districts lag in infrastructure, human capital, and access to markets [15,22,23]. | Rarely linked to climate shocks or gendered outcomes. | Quantifies that 42% of national inequality is spatial; integrates spatial gaps into inclusive growth framework. |

|

Gender & Labor under Climate Stress |

Climate shocks disproportionately affect women’s labor participation and asset security [29,30,31,32]. | No causal estimates exist; climate rarely integrated into labor market models. | Provides the first causal estimate of climate shocks on female labor force participation (FLFP) in Bangladesh. |

|

Fiscal Redistribution |

Progressive wealth and capital taxation can reduce inequality while sustaining growth [12,33,34,35,36]. | Rarely connected to structural transformation or adaptive social protection. | Simulates wealth tax (0.5–2.5%) financing universal secondary education without reducing growth. |

| Theories of Inequality & Growth | Simon Kuznets’s inverted-U curve suggests inequality falls with income [13,14]; Joseph Stiglitz and Dani Rodrik show persistent inequality under premature deindustrialization [2,16]; Amartya Sen stresses human capabilities [3]. | Not tested in service-led, climate-vulnerable economies. | Tests the growth–inequality link in a service-led, climate-exposed context, challenging Kuznets expectations. |

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Collection Framework

- NASA SEDAC population density grids (1 km resolution) for spatial inequality mapping.

- Bangladesh Bank credit disbursement data for financial inclusion analysis.

- CHIRPS rainfall data (1981–2023) for climate shock variables.

- HIES 2023 microdata for poverty and inequality benchmarks.

3.2. Analytical Strategy

3.3. Integration

3.4. Sampling Strategy

- District selection:Representing geographic diversity (northwest floodplains, coastal southwest, Dhaka–Chattogram growth corridor, hill tracts).

- Upazila stratification: Based on proximity to economic zones (industrial hubs vs peripheral areas).

- Village selection: Random selection using probability proportional to size (PPS).

- Household selection: Random sampling within villages with gender balance quotas.

3.5. Empirical Strategy

3.5.1. Inclusive Growth Index Regression

3.5.2. Inequality Decomposition

3.5.3. Climate–Economy Modeling

- Crop Yields: The DSSAT (Decision Support System for Agrotechnology Transfer) model informed estimates of crop productivity under rainfall variability and salinity shocks. These estimates parameterized sector-specific climate sensitivity values () in the CGE model.

- Macroeconomic Impacts: Sectoral outputs were fed into the CGE model using a climate-adjusted Cobb–Douglas specification:

3.5.4. Gender–Climate Nexus

3.5.5. Policy Simulation (DSGE Model)

- = Tax rates on income, wages, capital, and wealth

- = Aggregate macro variables (output, wages, labor, return to capital, capital stock, assets)

3.5.6. Equation Summary and Model Alignment

3.6. Validation Protocols

- Machine Learning Diagnostics: Random Forest models assessed variable importance in inequality regressions. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values were used to interpret non-linear interactions.

- Qualitative Validation: Focus group discussions and expert panel consultations (including policymakers, academics, and industry representatives) reviewed findings and refined policy recommendations.

- Robustness Checks: Alternative inequality measures (Atkinson index) and placebo tests with non-climate shocks ensured model credibility.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

3.8. Methodological Contributions

- Multidimensional Framework: Integrating spatial, gendered, and climate dimensions within CGE and DSGE models.

- Transferability: The framework can be adapted to other developing countries facing inequality, climate risk, and fiscal constraints.

4. Results

4.1. The Sectoral Productivity Paradox

4.2. Spatial Inequality Drivers

4.2.1. Infrastructure Access Gradient

4.2.2. Poverty Persistence in Climate-Vulnerable Regions

4.2.3. Decomposition Results

4.3. Climate–Gender Nexus

- Increased care burdens during disasters limit women’s ability to engage in paid work.

- Loss of agricultural income reduces household demand for female labor, particularly in informal sectors.

4.4. Policy Simulation Findings

4.4.1. Wealth Taxation for Education

4.4.2. Inequality Reduction

4.4.3. Comparative Insights

4.5. Integrated Narrative of Results

- Sectoral: Productivity gains in the RMG sector have not translated into broad-based wage improvements.

- Spatial: Regional divides are entrenched by infrastructure gaps and climate vulnerability.

- Gendered: Women’s labor force participation is disproportionately constrained by environmental shocks.

- Fiscal: Untapped redistributive potential could finance inclusive policies without slowing growth.

5. Policy Implications

5.1. A Three-Pillar Reform Strategy

5.2. Implementation Pathways

5.3. Political Economy Constraints

5.4. Global Lessons and Transferability

5.5. Synthesis

6. Conclusion

6.1. Key Findings

6.2. Theoretical and Policy Implications

- Questioning the automatic decline of inequality with income growth in service-led economies,

- Highlighting the gender–climate feedback mechanism in labor markets, and

- Showing that redistribution can support, rather than impede, structural transformation through human capital accumulation.

6.3. Future Research Directions

6.4. Limitations and Future Work

6.5. Final Authorial Reflection

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. World Development Indicators; 2024.

- Rodrik, D. Premature deindustrialization. J. Econ. Growth 2016, 21, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2022; BBS: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Wealth Distribution Report; BBS: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Klasen, S. What explains uneven female labor force participation levels and trends in developing countries? World Bank Res. Obs. 2018, 34, 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Planning Commission. Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review; Planning Commission: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. E. Inequality and economic growth. Political Q. 2015, 86, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kanbur, R.; Venables, A. J. Spatial inequality and development. Oxford Dev. Stud. 2005, 33, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, M. Gender mainstreaming and climate change. Women's Stud. Int. Forum 2014, 47, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznets, S. Economic growth and income inequality. Am. Econ. Rev. 1955, 45, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, F. Inequality and globalization. Foreign Aff. 2018, 97, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Raihan, S.; Khondker, B. H. Spatial disparity in poverty in Bangladesh. Bangl. Dev. Stud. 2019, 42, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, G.; Lu, M.; Chen, Z. The inequality–growth nexus in the short and long run: Evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2006, 34, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Jahan, I.; Chowdhury, S. Spatial Inequality, Urban Bias, and Inclusive Development in Bangladesh: Policy Lessons. Sustainability 2024, 16, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, H.; Tran, Q.H. Fiscal Policies for Inclusive Growth in Emerging Economies: Evidence from Southeast Asia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Bangladesh Jobs Diagnostic Update; World Bank: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Choudhury, S. R. Spatial inequalities in Bangladesh. Dev. Pract. 2022, 32, 927–941. [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran, S. Social norms as a barrier to women’s employment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2021, 111, 1462–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, R.; Jayachandran, S. The causes and consequences of increased female education and labor force participation in developing countries. World Dev. 2017, 96, 597–611. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, R. I.; Islam, R. Female labour force participation in Bangladesh: trends, drivers and barriers. ILO, 2013.

- Rahman, M.M.; Khan, M.A.; Alam, K. Climate Change, Migration, and Gendered Vulnerability in South Asia: Evidence from Bangladesh. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaduzzaman, M.; Haque, M.I.; Tasnim, T. Intersectionality, Climate Change, and Gendered Vulnerabilities in Coastal Bangladesh. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Huq, M.; Wheeler, D. Climate change and socio-economic vulnerability in Bangladesh. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2015, 20, 177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig, N. Fiscal policy, inequality, and the poor in the developing world. World Bank Res. Obs. 2017, 32, 210–236. [Google Scholar]

- Saez, E.; Zucman, G. The Triumph of Injustice; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Revenue Statistics; OECD: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Bangladesh Public Expenditure Review 2023; World Bank: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- National Skills Development Authority. Bangladesh National Technical and Vocational Qualifications Framework (NTVQF) Report; NSDA: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). Skills for Industry 4.0: Lessons from Asia-Pacific; ADB: Manila, Philippines, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Bangladesh Spatial Development Report: Infrastructure and Economic Access; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Decentralization and Local Governance in Bangladesh: Lessons and Policy Options; United Nations Development Programme: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Ministry of Disaster Management. Adaptive Social Protection and Climate Resilience Strategy; MoDM: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF). Digital Cash Transfers for Resilience: Case Studies from Kenya and India; UNCDF: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. Sequencing Structural Reforms: Practical Lessons for Emerging Economies; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, R.; Zolt, E. Taxation and Development in South Asia: Political Economy Considerations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Building State Capacity for Social Protection Delivery in Developing Countries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, K. M.; Do, T. T. Export Diversification and Inclusive Growth in Vietnam: Policy Lessons for Late-Industrializing Economies. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2021, 16, 345–366. [Google Scholar]

- Fiszbein, A.; Schady, N. Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Poverty While Promoting Human Capital; World Bank Policy Research Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Indicator / Estimate | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Sectoral (RMG) | Productivity ↑ 3.2% annually (2015–2023); wages ↑ 0.8% | Productivity gains not shared with workers → widening wage–productivity gap |

| Spatial Inequality | 42% of national inequality explained by spatial factors | Regional divides are more severe than India (28%) or Vietnam (19%) |

| Climate–Gender Nexus | Major disaster reduces FLFP by 11.3 pp, vs 3.1 pp for men | Climate shocks disproportionately exclude women from labor markets |

| Fiscal Redistribution | Wealth tax (0.5–2.5%) → revenue ~1.2% GDP; Gini ↓ 0.07 | Redistribution can finance education & inclusion without slowing growth |

| Phase & Timeline | Core Interventions | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

|

Phase 1 (2025–2027) |

|

Foundation building: fiscal mobilization, skills pipeline, pilot adaptive social protection |

| Phase 2 (2028–2030) |

|

Expansion: territorial rebalancing, export diversification, stronger resilience budgeting |

|

Phase 3 (2031–2035) |

|

Consolidation: inclusive education, resilient social protection, structural transformation achieved |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).