Submitted:

17 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Origins and development of Zero-point energy

2.1. Max-Planck and the black body spectrum

2.2. Modern derivation of ZPE in free electromagnetic field

2.3. Zero-point energy: Mathematical consistency and its role as a source term

- Dirac, in 1975, challenged the mathematical legitimacy of these approaches, asserting that "Sensible mathematics involves disregarding a quantity when it is small – not neglecting it just because it is infinitely great and you do not want it!" [48]3 This critique directly questions how QED and QCD handle infinite quantities when calculating particle masses.

- Feynman, in 1985, despite his pivotal role in developing QED, remained skeptical of its mathematical foundation, describing renormalization as a "dippy process" and "hocus-pocus" that has "prevented us from proving that the theory of quantum electrodynamics is mathematically self-consistent," ultimately suspecting that "renormalization is not mathematically legitimate." [68]4

3. Quantum electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations and its energy density

3.1. Quantum vacuum energy density

3.2. Natural cut-off at the quantum scale

3.3. Consequences of the Planck length cut-off

4. The Origin of Mass as Coherent Modes of Quantum Vacuum Fluctuations at the Hadronic Scale

4.1. Electromagnetic Vacuum Fluctuations Correlation Functions in the Temperature-Independent Regime

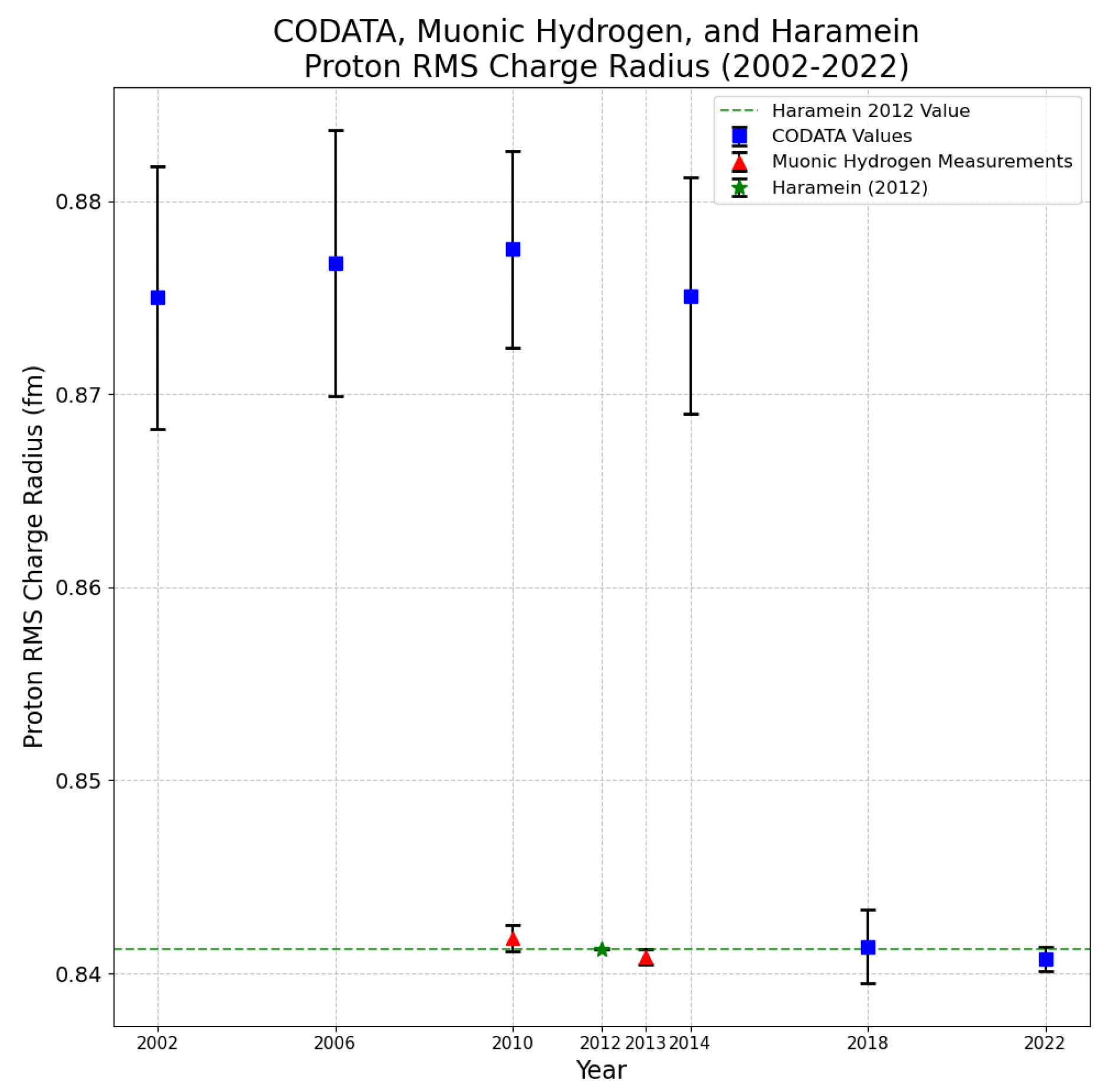

4.2. Effective radius and the charge radius ’puzzle’

- 1.

-

It marks the quantum-classical boundary through two mechanisms:

- At distances approaching , Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle shows momentum uncertainty becomes , making relativistic effects and particle-antiparticle pair creation energetically possible

- Solutions to the relativistic Klein-Gordon equation diverge from the non-relativistic Schrödinger approximation at

- 2.

- It establishes the characteristic scale at which vacuum fluctuations effectively couple to the proton’s mass-energy structure

- 3.

- It governs the exponential decay rate of virtual mesons mediating the nuclear force, as Hideki Yukawa demonstrated [60], where the potential follows

4.3. Temperature Emergence from Quantum Vacuum Decoherence

5. From Quantum Vacuum Fluctuations to gravitational field in general relativity

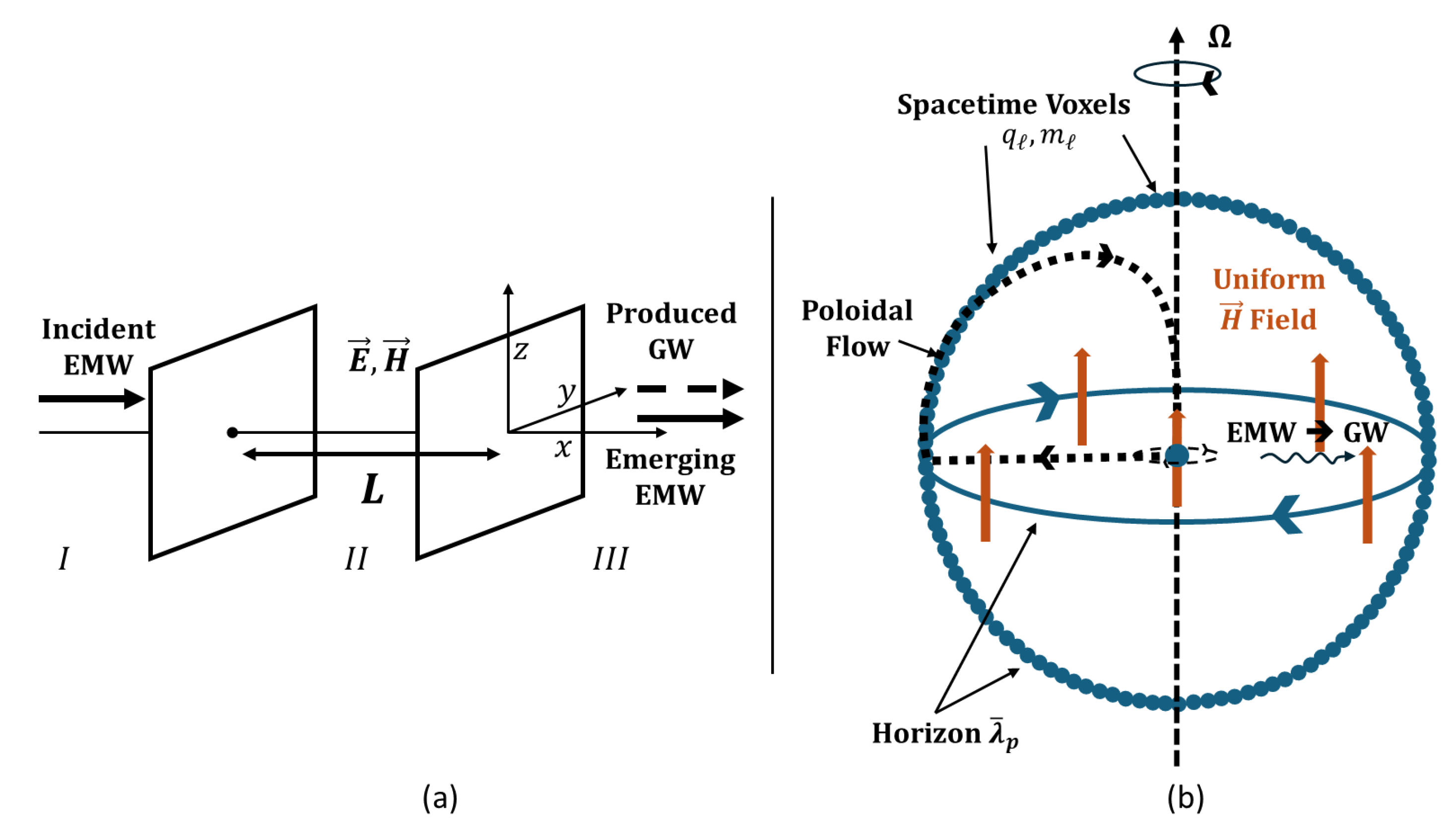

5.1. First screening: Electromagnetic Vacuum Fluctuations to Gravitational Wave Generation

5.2. Kerr-Newman solution and black hole particle

6. Hawking Radiation at the Proton Scale: From Vacuum Fluctuations to Mass Generation

6.1. Hawking Radiation Analysis at the Proton Scale

6.2. Hawking Evaporation

- Minimal SU(5) GUT models predict proton lifetimes of approximately years [91],

- supersymmetric SU(5) models typically yield values around years [92],

- SO(10) GUT frameworks predict lifetimes ranging from to years depending on symmetry breaking patterns [92],

- String theory-inspired models with additional dimensions suggest values between and years [93].

6.3. Second Screening: Quantum Gravitational Transduction to Electromagnetic Mass

- 1.

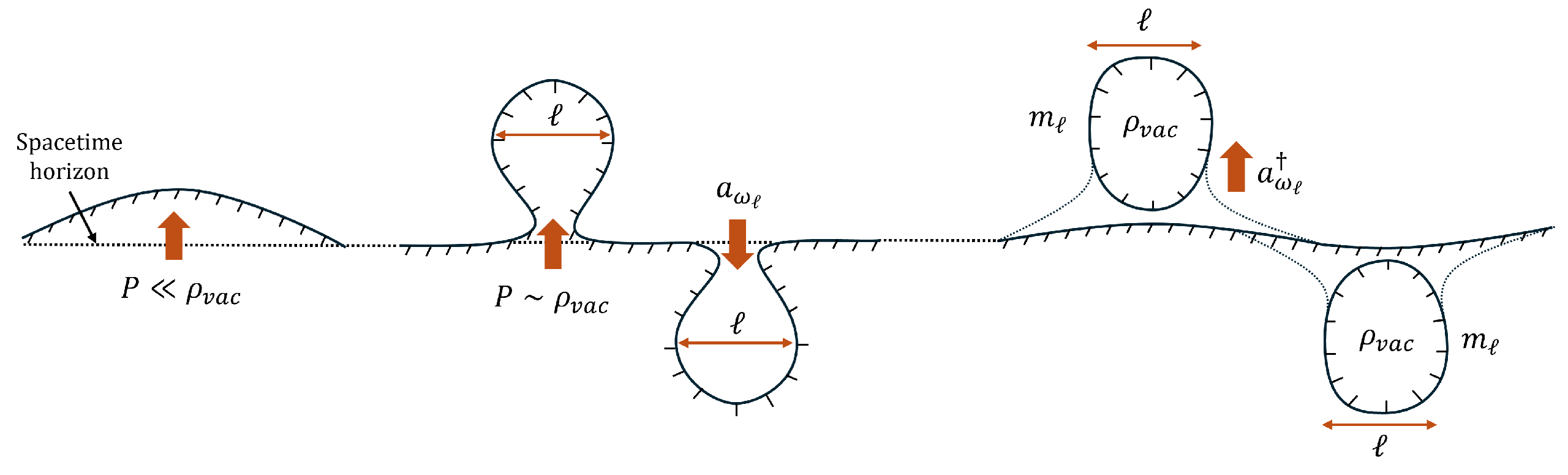

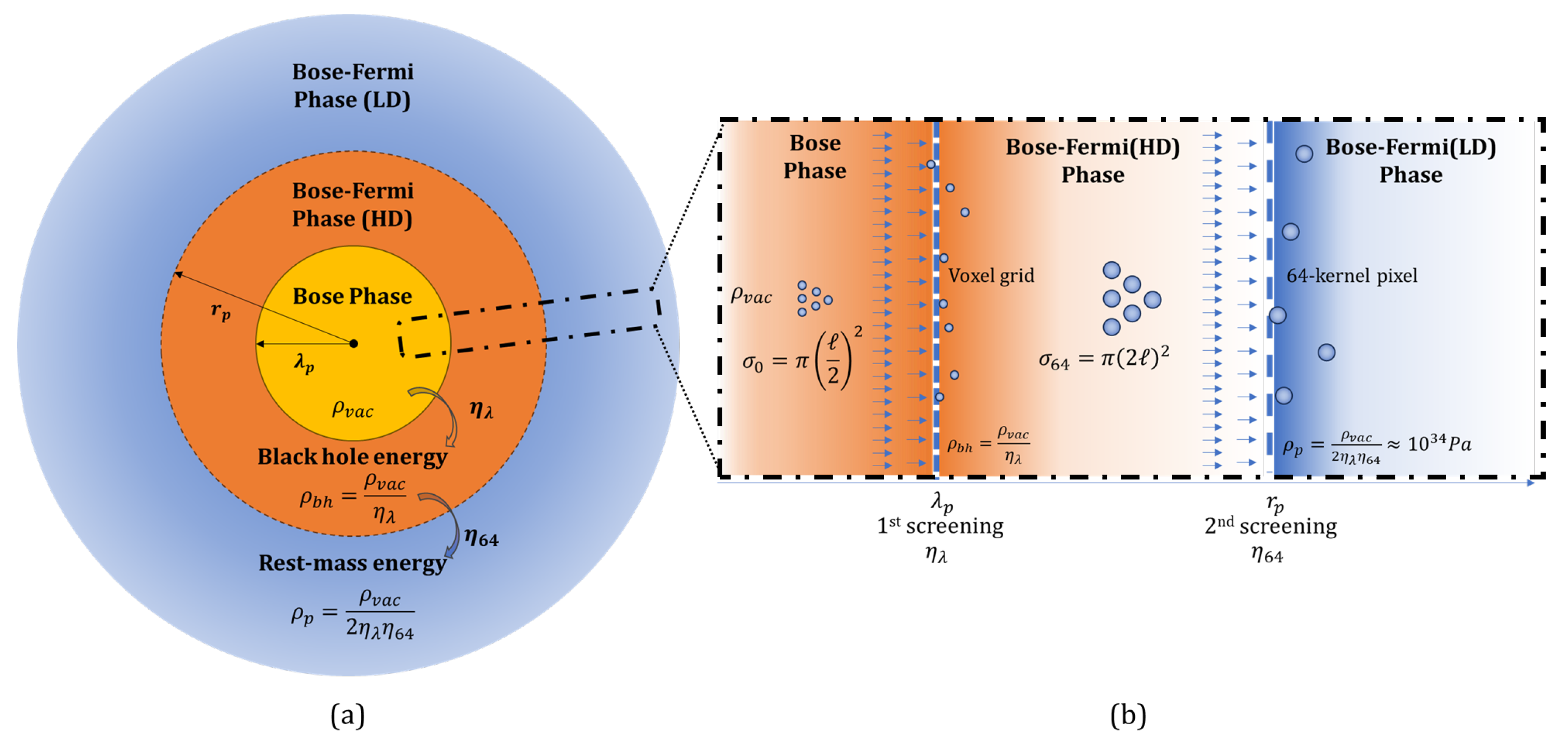

- At the proton’s core black hole horizon , the parameter performs primary filtering of individual voxels with characteristic wavelength in the high-coherence Bose phase. This boundary represents the interface where vacuum energy undergoes its first phase transition.

- 2.

-

Subsequently, a secondary screening occurs at the charge radius through Planck-scale entities in the high-density Bose-Fermi phase. Each of these entities corresponds to a quantized spacetime structure carrying discrete mass-energy equivalent to a Schwarzschild radius of Planck massThese discrete structures represent the fundamental building blocks of the proton’s rest mass-energy content, analogous to the water molecules in Wheeler’s ocean metaphor, which corresponds to 64 elementary Planck voxels aggregates in the volume of a sphere of radius which surface tiles 64 voxels defining the first "primordial" black hole (previously identified in [94,95]) that we term kernel-64 which reduces the surface information capacity to

- 1.

- Correlation functions in quantum vacuum fluctuations establishing precise filtering parameters and ;

- 2.

- Hawking radiation thermodynamics predicting the proton mass as emergent radiation at exactly the proton charge radius;

- 3.

- Zel’dovich-Boccaletti’s gravitational-electromagnetic transduction framework elucidating the mathematical mechanism by which gravitational waves convert to electromagnetic manifestations.

7. Solving Einstein’s field equations for a continuous energy density profile

- 1.

- The innermost Bose phase, dominated by quantum vacuum fluctuations at the Planck scale

- 2.

-

The intermediate Bose-Fermi phase beginning at the reduced Compton wavelength boundary (), subdivided into:

- A high-density (HD) region extending from to the proton charge radius ()

- A low-density (LD) region beyond

- 3.

- The outermost Fermi phase beginning at the full Compton wavelength (), governing long-range interactions

- 1.

-

Bose-Fermi (HD) Phase: First Screening ()The energy density of the high-density Bose-Fermi phase emerges from the primary screening of quantum vacuum fluctuations, wherein kernel-64 aggregates of spacetime voxels coherently generate electromagnetic waves with characteristic wavelength (see Section 6.3). Applying the boundary condition at the reduced Compton wavelength, we derive the amplitude constant , yieldingand the corresponding gravitational wave

- 2.

-

Bose-Fermi (LD) Phase: Second Screening ()The energy density of the low density Bose-Fermi phase resulting from the second screening mechanism involves electromagnetic waves generated by the proton black hole horizon, with wavelength . The boundary condition yields , and results inwith the corresponding gravitational wave

- 3.

-

Fermi Phase: Long-Range Dynamics (_)This final case represents the long-range behavior, incorporating a third screening of the gravitational energy flux where which leads to . Utilizing a first-order approximation where and , we obtainAnd the corresponding gravitational wavewhere represents the gravitational coupling constant characterizing the relationship between the strong nuclear force and the gravitational force and, here, phase transitions of the Planck plasma flow associated to a change in energy density as described in Section 5.1.

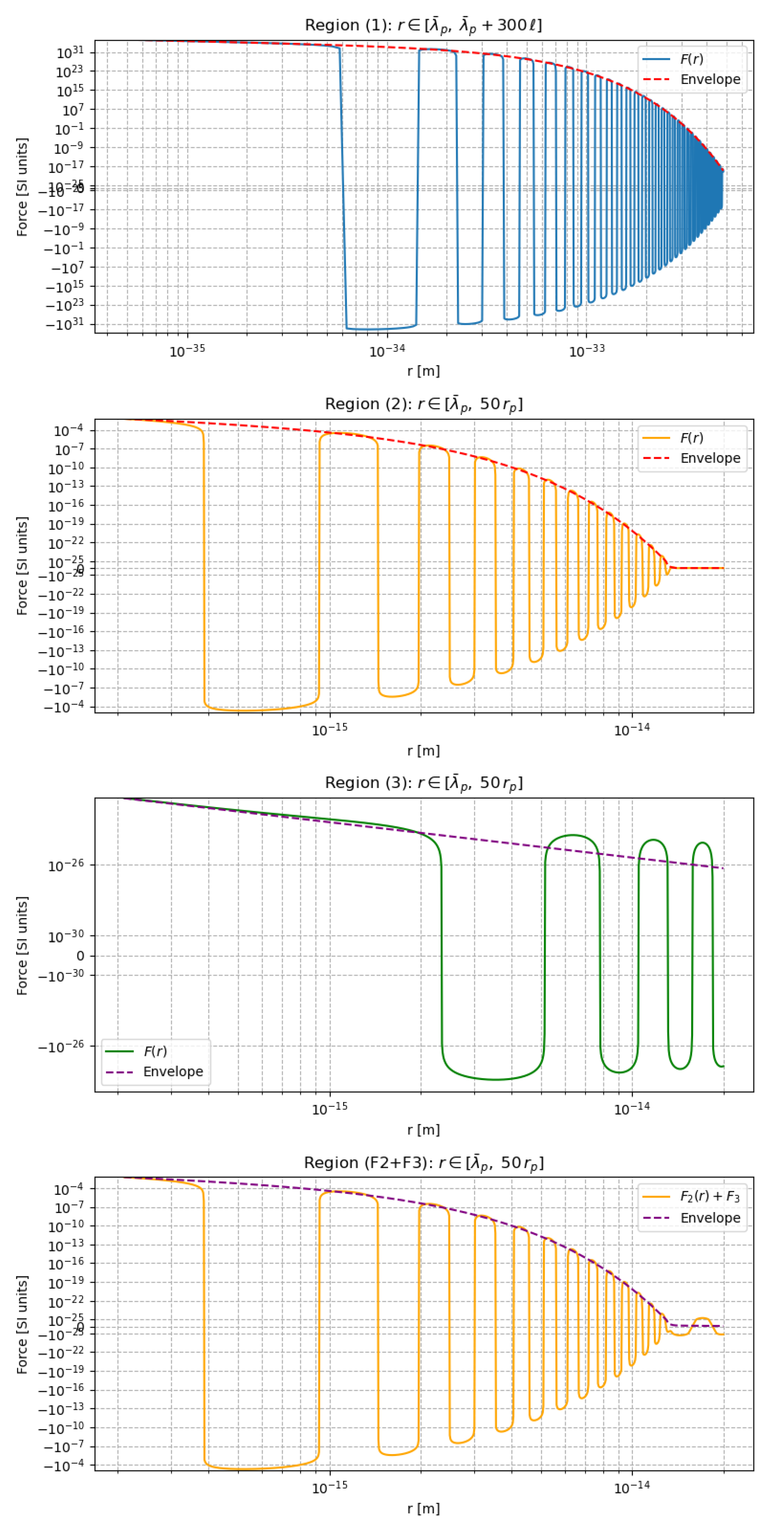

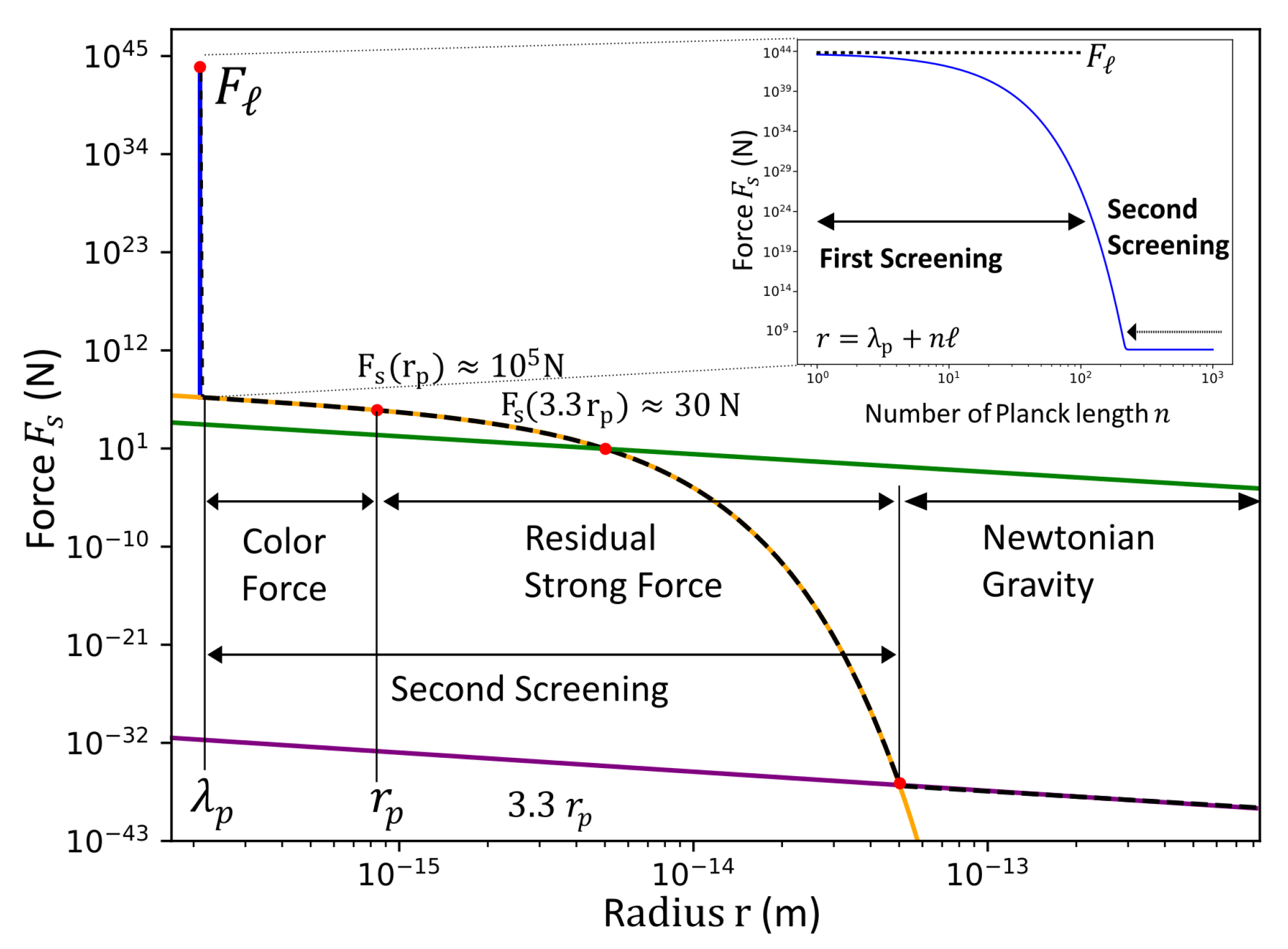

- 1.

- The first term dominates in the innermost high density Bose-Fermi phase region near the reduced Compton wavelength

- 2.

- The second term becomes predominant at intermediate distances around the proton charge radius in the low density Bose-Fermi phase.

- 3.

- The third term governs the long-range interactions at distances far beyond the proton radius () in the Fermi phase.

8. Geometric Unification of Color Confinement, Residual Strong Force, and Gravity

8.1. From Metric Perturbations to Fundamental Nuclear Forces: A Geometric Derivation

8.2. Gravitational Origin of the Strong and Residual Strong Force

8.2.1. Strong Force

8.2.2. Residual Strong Force

9. Discussion and Theoretical Implications at the cosmological scale

9.1. Scaling Across Horizons

9.2. Holographic Encoding

| Proton | Universe | |

|---|---|---|

| Mass | ||

| Radius |

9.3. Cosmological Constant Implications

10. Conclusion

10.1. Main Results

- 1.

- Origin of Proton Mass: By treating the proton as a resonant cavity and analyzing correlation functions of zero-temperature blackbody radiation, we quantitatively derive the proton’s rest mass () from coherent electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations at its charge radius (), aligning precisely with experimental data and addressing the “proton radius puzzle” (Figure 2).

- 2.

- Electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations curving spacetime: We utilize Zel’dovich’s mechanism, building on Boccaletti et al.’s formalism, to compute the electromagnetic wave (EMW) to gravitational wave (GW) conversion via linearized Einstein field equations in the weak-field approximation. An incident EMW with energy density generated by coherent quantum vacuum fluctuations propagates through a strong static magnetic field H emerging from the collective behavior of individual vacuum fluctuations voxel within proton cavity. The resulting electromagnetic stress-energy tensor sources metric perturbations . The GW energy flux is computed via the Landau-Lifschitz pseudo-tensor , resulting in conversion coefficient , screening the vacuum energy density , resulting in a spacetime curvature equivalent to a Kerr-Newman proton’s black hole-like core and further strengthening the relationship between the charge radius and the Compton wavelength of the proton.

- 3.

- Proton Core: The decoherence of electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations manifests a Hawking-like temperature of a proton-size black hole, yielding a Kerr–Newman structure at the proton’s reduced Compton wavelength. Hawking radiation at this scale reproduces the proton’s mass, while the evaporation lifetime largely exceeds the universe’s age, explaining proton stability and suggesting black holes as fundamental quantum-gravitational structures at subatomic scales.

- 4.

- Geometric Confinement: The strong nuclear force and color confinement arise as gravitational effects of spacetime curvature induced by electromagnetic vacuum fluctuations. A Yukawa-like confining potential, derived from metric perturbations, matches lattice QCD simulations without free parameters, contrasting with QCD’s reliance on gluonic condensates or chiral symmetry breaking. This emphasis on electromagnetic (EM) quantum vacuum fluctuations as the primary mechanism reflects their universal presence as the photon field’s ground state, their direct empirical validation through phenomena like the Lamb shift and Casimir effect, and their proven coupling to spacetime curvature via Einstein’s field equations and the Zel’dovich mechanism [56]. By prioritizing EM fluctuations, we establish a geometric foundation that hierarchically underpins other interactions—such as the strong and weak forces—recasting them as effective manifestations of this curvature, rather than elevating EM forces above others in isolation.

- 5.

- Unification of Forces: This approach unifies nuclear-scale physics with gravitational phenomena by reconceptualizing both confining forces and gravity as emergent manifestations of spacetime curvature. This framework reveals that what appears as the strong force at nuclear distances is actually an extreme gravitational effect arising from quantum vacuum-induced spacetime geometry. Gravity, the strong force, and residual nuclear interactions are unified as screened manifestations of vacuum energy density, with force hierarchies (Table 2) emerging from geometric screening parameters (). This eliminates the need for distinct fundamental interactions, framing forces as emergent spacetime curvature effects.

10.2. Broader Implications

- 1.

- Cosmological Connections: The holographic scaling of vacuum energy density reveals a fundamental link between the proton’s internal structure and the universe’s large-scale geometry. Our model shows that the screened vacuum energy density aligns with the observed critical density (, Equation (140)), suggesting a holographic encoding where each proton encapsulates universal information. Furthermore, the cosmological constant (, Equation (146)) emerges naturally from the geometric screening mechanism, providing a natural explanation for effects generally attributed to dark energy and dark matter without invoking additional fields or modifying general relativity, thus bridging quantum physics and cosmology in a unified framework.

- 2.

- Black Hole Formation: This framework establishes a direct connection between quantum field correlations and spacetime geometry through Einstein field equations, where electromagnetic vacuum energy density directly induces metric curvature via spacetime elasticity sufficient to generate self-gravitating solutions. This self-confinement mechanism—arising from coupling between quantum vacuum stress–energy and spacetime curvature—demonstrates that coherent vacuum modes inevitably generate black-hole-like geometries without conventional matter accretion. These quantum vacuum coherent behaviors at the source of black holes formation may explain recent James Webb Space Telescope observations of supermassive black holes at redshifts in the early universe, where conventional star formation and accretion time frames appear insufficient to produce such massive structures [84,85].

- 3.

- Quantum Gravity and the Standard Model: Our model diverges from prevailing unified theories by grounding both gravitational and strong nuclear forces in a single microscopic mechanism: electromagnetic quantum vacuum fluctuations inducing spacetime curvature. Unlike entropic gravity (e.g., [105]), which derives gravity from thermodynamic entropy without addressing quantum vacuum origins or nuclear scales, our framework roots forces in vacuum fluctuation-induced curvature, extending to entropic effects via decoherence across all scales. Emergent spacetime models (e.g., tensor networks [42]) propose geometry from quantum information but lack explicit mechanisms for mass generation; in contrast, we offer analytical derivations of hadron masses from correlation functions (Section 4). Holographic QCD models (e.g., [31]) approximate confinement via AdS/CFT dualities with adjustable parameters in 5-dimensional anti-de Sitter space, whereas our parameter-free approach computes Yukawa-like potentials directly from Einstein’s field equations (Section 7) in standard 4-dimensional spacetime, emphasizing geometric screening over boundary dualities. This synthesis aligns with Einstein-Rosen bridges and ER=EPR entanglement [27], geometrizing confinement energy as spacetime curvature and unifying nuclear binding with gravitational attraction through a coherent vacuum-mediated framework.

- 4.

- From QCD to Spacetime Curvature: In the Standard Model, the proton’s mass is predominantly ascribed to gluonic binding energy and spontaneous chiral symmetry breaking within QCD, with the Higgs mechanism contributing only through quark mass terms and the remaining typically linked to QCD dynamics. In contrast, our model demonstrates that the entire proton mass emerges from the decoherence of electromagnetic quantum vacuum fluctuations. This process involves the hierarchical screening of zero-point energy at the proton’s charge radius () and reduced Compton wavelength (), potentially giving an alternative to the roles of gluonic condensates and chiral symmetry breaking as the primary mass-generation mechanism. Unlike lattice QCD, which requires fitting numerous parameters to match experimental data, by framing this within a geometric paradigm where spacetime curvature induced by vacuum fluctuations unifies mass and confinement, we circumvent the computational intricacies of lattice QCD, offering a streamlined, first-principles approach.

10.3. Open Questions and Ending Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Paper Notations

Appendix A.1. Planck Units

- ℓ

- Planck length, .

- Planck mass, .

- Planck charge, .

- Planck time, .

- Planck temperature, .

- Planck force, .

Appendix A.2. Particle Properties

- Proton rest mass.

- Proton charge radius.

- Proton Compton wavelength, .

- Reduced proton Compton wavelength, .

- Proton characteristic time, .

- M

- Mass from Schwarzschild solution, .

- Schwarzschild mass at reduced Compton wavelength, .

- String tension from lattice QCD, GeV/fm.

Appendix A.3. Vacuum and Energy Densities

- Vacuum energy density, J/.

- Proton energy density, J/.

- Energy density at reduced Compton wavelength, .

- Critical density, .

Appendix A.4. Black Hole and Gravitational Parameters

- Schwarzschild radius, .

- Hawking temperature, .

- Modified Hawking temperature at reduced Compton wavelength, .

- Lattice QCD Confinement potential, .

- S

- Black hole entropy, .

- Dark energy density parameter, .

- Screening parameter, .

- Screening at charge radius, .

- Kernel-64 screening, .

- Universal screening parameter.

- Holographic ratio, .

- Gravitational coupling constant, .

- EMW to GW conversion coefficient, .

- Black hole evaporation lifetime, years.

- Radius reduction over universe age, m.

- Universe radius, .

- Cosmological constant, .

Appendix B. Correlation function and black body radiation

Appendix C. Experimental validations of the ZPE

- 1.

-

Casimir Effect: Predicted by Hendrik Casimir [106], this is the attractive force between two closely spaced, parallel, uncharged conducting plates in a vacuum. It arises because the plates alter the boundary conditions for vacuum fluctuations, excluding longer wavelength modes between them compared to outside. This difference in vacuum pressure results in a net attractive force.

- 2.

- Lamb Shift: Discovered by Willis Lamb [49], this is a small energy difference between the and states in the hydrogen atom, which Dirac’s original relativistic theory predicted to be degenerate. Bethe provided the first theoretical explanation [20], attributing it to the interaction of the bound electron with vacuum fluctuations, effectively "smearing" the electron’s position and modifying its interaction with the Coulomb potential. Precise measurements of the Lamb shift provide stringent tests of QED.

- 3.

- Anomalous Magnetic Moment of the Electron (g-2): Dirac’s theory predicts the electron’s g-factor to be exactly 2. Schwinger first calculated the leading QED correction [21], showing that interactions with vacuum fluctuations slightly increase the magnetic moment (). Extremely precise measurements and higher-order QED calculations of show remarkable agreement, making it one of the most accurately verified predictions in physics [118].

- 4.

- Spontaneous Emission: An excited atom in vacuum will spontaneously decay to a lower energy state by emitting a photon. In classical electrodynamics, an excited state is stable without external perturbation. Quantum mechanically, spontaneous emission is triggered by the interaction of the atom with vacuum fluctuations of the electromagnetic field [61,119].

- 5.

- Van der Waals Forces: These are weak, short-range attractive forces between neutral atoms or molecules. The London dispersion force, a component of Van der Waals forces, arises from quantum fluctuations creating temporary dipoles that induce dipoles in neighboring atoms/molecules. At larger distances, retardation effects (finite speed of light) modify the interaction, becoming the Casimir-Polder force [120], directly related to ZPE.

- 6.

- Hawking Radiation: Predicted by Stephen Hawking [64], black holes are expected to emit thermal radiation due to quantum effects near the event horizon. Pair production from vacuum fluctuations near the horizon leads to one particle falling in and the other escaping, effectively causing the black hole to radiate and lose mass. This is a prediction linking ZPE, quantum mechanics, and general relativity.

- 7.

- Electron-Positron Pair Production (Schwinger Effect): In extremely strong electric fields, virtual electron-positron pairs from the vacuum can be separated and become real particles [121,122]. While the required field strength is immense ( V/m), analogous effects are observed in condensed matter systems like graphene [123,124] and potentially in heavy-ion collisions [125] or magnetar magnetospheres [126].

- 8.

- Casimir Diode: The Casimir Diode is a non-reciprocal device based on quantum vacuum fluctuations, that can affect unidirectional transfer of energy, like a diode [127].

One of the most surprising predictions of modern quantum theory is that the vacuum of space is not empty. In fact, quantum theory predicts that it teems with virtual particles flitting in and out of existence. While initially a curiosity, it was quickly realized that these vacuum fluctuations had measurable consequences, for instance producing the Lamb shift of atomic spectra and modifying the magnetic moment for the electron. Wilson, 2011 [114]

These results open the door to using the Casimir torque as a micro- or nanoscale actuation mechanism, which would be relevant for a range of technologies, including microelectromechanical systems and liquid crystals. [...] The van der Waals and Casimir effects both result from the same mechanism (quantum and thermal fluctuations), although historically they were derived from different physical pictures. Somers, 2018 [111]

| ZPE-based Effect | Theoretical Prediction/Explanation | Experimental Validation | Additional Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Body radiation | Planck (1900-1912) [45] | Kirchhoff (1860) [128] | Milonni (1993) [61] |

| Photoelectric effect | Einstein (1905) [129] | Millikan (1916) [130] | Lehnert (2014) [131] |

| Spontaneous Photon Emission | Einstein (1916) | N/A | Dirac (1927) [119] |

| Lamb Shift | Bethe (1947) [20] | Lamb-Retherford (1947) [49] | |

| Casimir Effect | Casimir (1948) [120] | Lamoreaux (1997) [50] | Bordag (2001) [51] |

| Casimir Torque | Casimir (1948) [120] | Somers (2018) [111] | |

| Dynamical Casimir Effect | Moore(1970) [113] | Wilson(2011) [114] | Dodonov (2020) [117] |

| Hawking Radiation-Unruh Effect | Hawking-Zeldovich (1972-1973) - Unruh(1976) [80,132,133] | ||

| Electron-Positron pair creation | Dirac (1928) [134] | Anderson (1932) [52] | |

| Schwinger effect | Sauter (1931) [121] - Schwinger (1951) [122] | National Graphene Institute - Geim (2022) [123,124] | |

| Vacuum Birefringence | Heisenberg - Euler (1936) [135] | STAR experiment (2021) [125] - IXPE (2022) [135] | |

| Breit-Wheeler Effect | Breit-Wheeler (1934) [126] | Pike et al (2014) [136] | |

| Higgs mechanism | Anderson (1962) [137] | LHC (2013) [118] |

Appendix D. ZPE Calculation

Appendix E. Planck cut-off and metric gradient limit

Appendix F. Conversion ratio from EMW into GW

Appendix G. Test particle acceleration

Appendix G.1. Analysis of Proper Acceleration without the Oscillatory term

- Let us consider the spherically symmetric case where only and are non-zero. Thus the geodesic for the r coordinates corresponds to

- can be deduced from the conservation of energy (resulting from the time symmetry and associated killing vector )where E is the total energy of the system per unit mass.

- can be deduced from the conservation of angular momentum written aswhich is equal to 0 in the case of no angular momentum for the initial condition .

- the spherically symmetric case allows us to choose to be in the equatorial plane , as , we have

Appendix G.2. Analysis of Proper Acceleration with Oscillatory Terms

References

- Roberts, C.D. Origin of the proton mass 2023. 282, 01006. [CrossRef]

- Editorial. Proton Puzzles. Nature Review Physics 2021, 3. [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. Origins of mass. Open Physics 2012, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cho, A. Mass of the common quark finally nailed down. Science Magazine 2010, 201004.

- Deur, A.; Brodsky, S.J.; de Teramond, G.F. The QCD running coupling. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 2016, 90, 1–74. [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M. A schematic model of baryons and mesons. Physics Letters B 1964, 8, 1–4.

- Fritzsch, H.; Gell-Mann, M.; Leutwyler, H. Advantages of the color octet gluon picture. Physics Letters B 1973, 47, 365–368.

- Gross, D.J.; Wilczek, F. Asymptotically free gauge theories. I. Physical Review D 1973, 8, 3633.

- Shifman, M.A.; Vainshtein, A.I.; Zakharov, V.I. QCD and resonance physics. Theoretical foundations. Nuclear Physics B 1979, 147, 385–447.

- Yang, Y.B.; Liang, J.; Bi, Y.J.; Chen, Y.; Draper, T.; Liu, K.F.; Liu, Z. Proton mass decomposition from the QCD energy momentum tensor. Physical review letters 2018, 121, 212001.

- Durr, S.; Fodor, Z.; Frison, J.; Hoelbling, C.; Hoffmann, R.; Katz, S.D.; Krieg, S.; Kurth, T.; Lellouch, L.; Lippert, T.; et al. Ab initio determination of light hadron masses. Science 2008, 322, 1224–1227.

- Ji, X. Breakup of hadron masses and the energy-momentum tensor of QCD. Physical Review D 1995, 52, 271.

- Bali, G.S. QCD forces and heavy quark bound states. Physics Reports 2001, 343, 1–136.

- Necco, S.; Sommer, R. Testing perturbation theory on the Nf= 0 static quark potential. Physics Letters B 2001, 523, 135–142.

- Bazavov, A.; Toussaint, D.; Bernard, C.; Laiho, J.; DeTar, C.; Levkova, L.; Oktay, M.; Gottlieb, S.; Heller, U.; Hetrick, J.; et al. Nonperturbative QCD simulations with 2+ 1 flavors of improved staggered quarks. Reviews of modern physics 2010, 82, 1349–1417.

- Metz, A.; Pasquini, B.; Rodini, S. Revisiting the proton mass decomposition. Physical Review D 2020, 102, 114042.

- Burkert, V.D.; Elouadrhiri, L.; Girod, F.; Lorcé, C.; Schweitzer, P.; Shanahan, P. Colloquium: Gravitational form factors of the proton. Reviews of Modern Physics 2023, 95, 041002.

- Dirac, P.A.M. Classical theory of radiating electrons. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1938, 167, 148–169.

- Dyson, F.J. Divergence of perturbation theory in quantum electrodynamics. Physical Review 1952, 85, 631.

- Bethe, H.A. The Electromagnetic Shift of Energy Levels. Phys. Rev. 1947, 72, 339–341. [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J. On quantum-electrodynamics and the magnetic moment of the electron. Physical Review 1948, 73, 416.

- Weinberg, S. The quantum theory of fields; Vol. 2, Cambridge university press, 1995.

- Einstein, A. The field equations of gravitation. Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. Berlin (Math. Phys.) 1915, 1915, 844–847.

- Landau, L.D. The classical theory of fields; Vol. 2, Elsevier, 2013.

- Wilczek, F. Mass Without Mass I: Most of Matter. Physics Today 1999, 52, 11–13. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Rosen, N. The Particle Problem in the General Theory of Relativity. Phys. Rev. 1935, 48, 73–77. [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.; Susskind, L. Cool horizons for entangled black holes. Fortschritte der Physik 2013, 61, 781–811. [CrossRef]

- Haramein, N. The Schwarzschild Proton. 2010, pp. 95–100.

- Donoghue, J.F.; Menezes, G. Inducing the Einstein action in QCD-like theories. Physical Review D 2018, 97, 056022.

- Greene, B.R.; Morrison, D.R.; Polchinski, J. String theory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 11039–11040.

- Maldacena, J. The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. International journal of theoretical physics 1999, 38, 1113–1133.

- Susskind, L. The anthropic landscape of string theory. arXiv preprint hep-th/0302219 2003.

- Rovelli, C.; Smolin, L. Loop space representation of quantum general relativity. Nuclear Physics B 1990, 331, 80–152.

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Background independent quantum gravity: a status report. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, R53.

- Amelino-Camelia, G. Quantum-gravity phenomenology: Status and prospects. Modern Physics Letters A 2002, 17, 899–922.

- Reuter, M. Nonperturbative evolution equation for quantum gravity. Physical Review D 1998, 57, 971.

- Percacci, R. An introduction to covariant quantum gravity and asymptotic safety; Vol. 3, World Scientific, 2017.

- Vafa, C. The string landscape and the swampland. arXiv preprint hep-th/0509212 2005.

- Palti, E. The swampland: introduction and review. Fortschritte der Physik 2019, 67, 1900037.

- Dowker, F. Introduction to causal sets and their phenomenology. General Relativity and Gravitation 2013, 45, 1651–1667. [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, R.D. Causal sets: Discrete gravity. In Lectures on quantum gravity; Springer, 2005; pp. 305–327.

- Swingle, B. Entanglement renormalization and holography. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2012, 86, 065007.

- Pastawski, F.; Yoshida, B.; Harlow, D.; Preskill, J. Holographic quantum error-correcting codes: Toy models for the bulk/boundary correspondence. Journal of High Energy Physics 2015, 2015, 1–55.

- Loll, R. Quantum gravity from causal dynamical triangulations: a review. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2019, 37, 013002.

- Planck, M. Über die Begründung des Gesetzes der schwarzen Strahlung. Ann. Phys. 1912, 342, 642–656. [CrossRef]

- Milonni, P.W. An Introduction to Quantum Optics and Quantum Fluctuations, 1 ed.; Oxford University PressOxford, 2019-01-31. [CrossRef]

- Milonni, P.W.; Shih, M.L. Zero-point energy in early quantum theory. American Journal of Physics 1991-08, 59, 684–698. [CrossRef]

- Kragh, H. Dirac: a scientific biography; Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Lamb Jr, W.E.; Retherford, R.C. Fine structure of the hydrogen atom by a microwave method. Physical Review 1947, 72, 241. [CrossRef]

- Lamoreaux, S.K. Demonstration of the Casimir force in the 0.6 to 6 μ m range. Physical Review Letters 1997, 78, 5. [CrossRef]

- Bordag, M.; Mohideen, U.; Mostepanenko, V.M. New Developments in the Casimir Effect. Physics Reports 2001-10, 353, 1–205, [quant-ph/0106045]. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.D. The Apparent Existence of Easily Deflectable Positives. Science 1932-09-09, 76, 238–239. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. On the nature of quantum geometrodynamics. Annals of Physics 1957-12, 2, 604–614. [CrossRef]

- Sakharov, A.D. Vacuum quantum fluctuations in curved space and the theory of gravitation. In Proceedings of the Doklady Akademii Nauk. Russian Academy of Sciences, 1967, Vol. 177, pp. 70–71.

- Adler, S.L. Einstein gravity as a symmetry-breaking effect in quantum field theory. Reviews of Modern Physics 1982, 54, 729.

- Zel’dovich, Y.B. Electromagnetic and gravitational waves in a stationary magnetic field. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz 1973, 65, 1311.

- Gertsenshtein, M. Wave resonance of light and gravitional waves. Sov Phys JETP 1962, 14, 84–85.

- Boccaletti, D.; De Sabbata, V.; Fortini, P.; Gualdi, C. Conversion of photons into gravitons and vice versa in a static electromagnetic field. Il Nuovo Cimento B (1965-1970) 1970, 70, 129–146.

- Hawking, S.W. Gravitational Radiation from Colliding Black Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1971-05-24, 26, 1344–1346. [CrossRef]

- Yukawa, H. On the interaction of elementary particles. I. Proceedings of the Physico-Mathematical Society of Japan. 3rd Series 1935, 17, 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Milonni, P.W. The quantum vacuum: an introduction to quantum electrodynamics; Academic press, 1993.

- Glauber, R.J. The quantum theory of optical coherence. Physical Review 1963, 130, 2529.

- Bochove, E.J. Quantum theory of phase-conjugate mirrors. Journal of the Optical Society of America B 1992, 9, 266–280.

- Hawking, S.W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in mathematical physics 1975, 43, 199–220.

- Hooft, G. The holographic principle. In Basics and Highlights in Fundamental Physics; World Scientific, 2001; pp. 72–100.

- Bigatti, D.; Susskind, L. TASI lectures on the holographic principle. In Strings, branes and gravity; World Scientific, 2001; pp. 883–933.

- Hawking, S.W. Virtual Black Holes. Phys. Rev. D 1996-03-15, 53, 3099–3107, [hep-th/9510029]. [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. QED: The strange theory of light and matter; Vol. 90, Princeton University Press, 1985.

- Bekenstein, J.D. Universal upper bound on the entropy-to-energy ratio for bounded systems. Phys. Rev. D 1981-01-15, 23, 287–298. [CrossRef]

- Rafelski, J. Discovery of quark-gluon plasma: strangeness diaries. The European Physical Journal Special Topics 2020, 229, 1–140. [CrossRef]

- Karsch, F., Lattice QCD at high temperature and density. In Lectures on quark matter; Springer, 2002; pp. 209–249. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, K.P.; Sivaram, C.; Sudarshan, E.C.G. The superfluid vacuum state, time-varying cosmological constant, and nonsingular cosmological models. Found Phys 1976-12, 6, 717–726. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The quantum theory of fields; Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Shanahan, P.; Detmold, W. Pressure distribution and shear forces inside the proton. Physical Review Letters 2019, 122, 072003. [CrossRef]

- Burkert, V.D.; Elouadrhiri, L.; Girod, F.X. The pressure distribution inside the proton. Nature 2018-05, 557, 396–399. [CrossRef]

- Haramein, N. Quantum Gravity and the Holographic Mass. Physical Science International Journal 2013, 3, 270–292.

- Antognini, A.; Bacca, S.; Fleischmann, A.; Gastaldo, L.; Hagelstein, F.; Indelicato, P.; Knecht, A.; Lensky, V.; Ohayon, B.; Pascalutsa, V.; et al. Muonic-Atom Spectroscopy and Impact on Nuclear Structure and Precision QED Theory, 2022-10-30, [2210.16929 [hep-ph, physics:nucl-th, physics:physics]].

- Lin, Y.H.; Hammer, H.W.; Meißner, U.G. New Insights into the Nucleon’s Electromagnetic Structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022-02-03, 128, 052002. Publisher: American Physical Society, . [CrossRef]

- Haramein, N. Quantum Gravity and the Holographic Mass, Quantum. Physical Review & Research International 2013, pp. 2231–1815.

- Hawking, S.W. Black hole explosions? Nature 1974-03-01, 248, 30–31. [CrossRef]

- Thorne, K.S.; Wheeler, J.A.; Misner, C.W. Gravitation; Freeman San Francisco, CA, 1971.

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshits, E.M.; Lifshits, E.M. Mechanics; Vol. 1, CUP Archive, 1960.

- Susskind, L. Cosmic Natural Selection, 2004-07-29, [hep-th/0407266].

- Yuan, G.W.; Lei, L.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, C.; Shen, Z.Q.; Cai, Y.F.; Fan, Y.Z. Rapidly growing primordial black holes as seeds of the massive high-redshift JWST Galaxies. arXiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Yoo, C.M.; Kohri, K. Threshold of primordial black hole formation. Physical Review D 2013, 88, 084051. [CrossRef]

- Dvali, G.; Gomez, C. Black holes as critical point of quantum phase transition. The European Physical Journal C 2014, 74, 1–12.

- Davies, P.C.W. Thermodynamic phase transitions of Kerr-Newman black holes in de Sitter space. Class. Quantum Grav. 1989-12-01, 6, 1909–1914. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. Geons. Phys. Rev. 1955-01-15, 97, 511–536. [CrossRef]

- Brill, D.R.; Hartle, J.B. Method of the Self-Consistent Field in General Relativity and its Application to the Gravitational Geon. Phys. Rev. 1964-07-13, 135, B271–B278. [CrossRef]

- Maiani, L. The J/Ψ as a probe of Quark-Gluon Plasma. Lectures given at the International School of Subnuclear Physics, Trapani, Italy 2004.

- Langacker, P. Grand unified theories. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Lepton and Photon Interactions at High Energies, Bonn. Citeseer, 1981.

- Burkert, V.; Elouadrhiri, L.; Girod, F. The pressure distribution inside the proton. Nature 2018, 557, 396–399.

- Antoniadis, I.; Baessler, S.; Büchner, M.; Fedorov, V.; Hoedl, S.; Lambrecht, A.; Nesvizhevsky, V.; Pignol, G.; Protasov, K.; Reynaud, S.; et al. Short-range fundamental forces. Comptes Rendus Physique 2011, 12, 755–778. [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Haramein, N.; Alirol, O. The electron and the holographic mass solution. Physics Essays 2019, 32.

- Haramein, N.; Baker, A.V. Resolving the vacuum catastrophe: a generalized holographic approach. Journal of High Energy Physics, Gravitation and Cosmology 2019, 5, 412–424. [CrossRef]

- Özel, F.; Freire, P. Masses, radii, and the equation of state of neutron stars. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2016, 54, 401–440. [CrossRef]

- Fritzsch, H. Quarks: the stuff of matter; 1983.

- Suganuma, H.; Iritani, T.; Okiharu, F.; Takahashi, T.T.; Yamamoto, A. Lattice QCD study for confinement in hadrons. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings. American Institute of Physics, 2011, Vol. 1388, pp. 195–201.

- Bali, G.S.; Schilling, K. Running coupling and the Λ parameter from SU (3) lattice simulations. Physical Review D 1993, 47, 661.

- Baker, M.; Cea, P.; Chelnokov, V.; Cosmai, L.; Cuteri, F.; Papa, A. The confining color field in SU (3) gauge theory. The European Physical Journal C 2020, 80, 514. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, T.; Abe, T.; Yoshida, T.; Tsunoda, Y.; Shimizu, N.; Itagaki, N.; Utsuno, Y.; Vary, J.; Maris, P.; Ueno, H. α-Clustering in atomic nuclei from first principles with statistical learning and the Hoyle state character. Nat Commun 2022-04-27, 13, 2234. [CrossRef]

- Ebran, J.P.; Khan, E.; Nikšić, T.; Vretenar, D. How atomic nuclei cluster. Nature 2012-07-19, 487, 341–344. [CrossRef]

- Carr, B.J.; Rees, M.J. The anthropic principle and the structure of the physical world. Nature 1979-04, 278, 605–612. [CrossRef]

- O’Raifeartaigh, C.; McCann, B.; Nahm, W.; Mitton, S. Einstein’s steady-state theory: an abandoned model of the cosmos. The European Physical Journal H 2014, 39, 353–367.

- Verlinde, E.P. On the Origin of Gravity and the Laws of Newton. J. High Energ. Phys. 2011-04, 2011, 29, [1001.0785 [hep-th]]. [CrossRef]

- G, C.H.B. On the Attraction between Two Perfectly Conducting Plates. Proc. Kon. Ned. Akad. Wet. 1948, 51, 793.

- Garrett, J.L.; Somers, D.A.; Munday, J.N. Measurement of the Casimir Force between Two Spheres. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018-01-23, 120, 040401. Publisher: American Physical Society, . [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, A.; Reynaud, S. Casimir force between metallic mirrors. The European Physical Journal D 2000, 8, 309–318. [CrossRef]

- Munday, J.N.; Iannuzzi, D.; Barash, Y.; Capasso, F. Torque on birefringent plates induced by quantum fluctuations. Phys. Rev. A 2005-04-14, 71, 042102. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Spence, J.C.H. On the measurement of the Casimir torque: On the measurement of the Casimir torque. Phys. Status Solidi B 2011-09, 248, 2064–2071. [CrossRef]

- Somers, D.A.T.; Garrett, J.L.; Palm, K.J.; Munday, J.N. Measurement of the Casimir torque. Nature 2018-12, 564, 386–389. [CrossRef]

- Guérout, R.; Genet, C.; Lambrecht, A.; Reynaud, S. Casimir torque between nanostructured plates. EPL 2015-08-01, 111, 44001. [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.T. Quantum Theory of the Electromagnetic Field in a Variable-Length One-Dimensional Cavity. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1970-09-01, 11, 2679–2691. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.M.; Johansson, G.; Pourkabirian, A.; Simoen, M.; Johansson, J.R.; Duty, T.; Nori, F.; Delsing, P. Observation of the dynamical Casimir effect in a superconducting circuit. Nature 2011-11, 479, 376–379. [CrossRef]

- Lähteenmäki, P.; Paraoanu, G.; Hassel, J.; Hakonen, P.J. Dynamical Casimir effect in a Josephson metamaterial. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 4234–4238.

- Vezzoli, S.; Mussot, A.; Westerberg, N.; Kudlinski, A.; Dinparasti Saleh, H.; Prain, A.; Biancalana, F.; Lantz, E.; Faccio, D. Optical analogue of the dynamical Casimir effect in a dispersion-oscillating fibre. Communications Physics 2019, 2, 84.

- Dodonov, V. Fifty Years of the Dynamical Casimir Effect. Physics 2020-02-14, 2, 67–104. [CrossRef]

- Altmannshofer, W.; Brod, J.; Schmaltz, M. Experimental constraints on the coupling of the Higgs boson to electrons. J. High Energ. Phys. 2015-05-25, 2015, 125. [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The quantum theory of the emission and absorption of radiation. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1927-03, 114, 243–265. [CrossRef]

- Casimir, H.B.G.; Polder, D. The Influence of Retardation on the London-van der Waals Forces. Phys. Rev. 1948-02-15, 73, 360–372. [CrossRef]

- Sauter, F. Über das Verhalten eines Elektrons im homogenen elektrischen Feld nach der relativistischen Theorie Diracs. Z. Physik 1931-11, 69, 742–764. [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J. On Gauge Invariance and Vacuum Polarization. Phys. Rev. 1951-06-01, 82, 664–679. [CrossRef]

- Berdyugin, A.I.; Xin, N.; Gao, H.; Slizovskiy, S.; Dong, Z.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Kumaravadivel, P.; Xu, S.; Ponomarenko, L.A.; Holwill, M.; et al. Out-of-equilibrium criticalities in graphene superlattices. Science 2022-01-28, 375, 430–433. Publisher: American Association for the Advancement of Science, . [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Vallet, P.; Mele, D.; Rosticher, M.; Taniguchi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Bocquillon, E.; Fève, G.; Berroir, J.M.; Voisin, C.; et al. Mesoscopic Klein-Schwinger effect in graphene. Nat. Phys. 2023-06, 19, 830–835. [CrossRef]

- et al., S.C. Measurement of e+e- Momentum and Angular Distributions from Linearly Polarized Photon Collisions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021-07-27, 127, 052302. Publisher: American Physical Society. [CrossRef]

- Breit, G.; Wheeler, J.A. Collision of two light quanta. Physical Review 1934, 46, 1087.

- Xu, Z.; Gao, X.; Bang, J.; Jacob, Z.; Li, T. Non-reciprocal energy transfer through the Casimir effect. Nature nanotechnology 2022, 17, 148–152.

- Kirchhoff, G. I. On the relation between the radiating and absorbing powers of different bodies for light and heat. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 1860, 20, 1–21.

- Einstein, A. Indeed, it seems to me that the observations regarding” blackbody radiation,” photoluminescence, production of cathode rays by ultraviolet. Annalen der Physik 1905, 17, 132–148.

- Millikan, R.A. A direct photoelectric determination of Planck’s" h". Physical Review 1916, 7, 355.

- Lehnert, B. Some Consequences of Zero Point Energy. Journal of Electromagnetic Analysis and Applications 2014, 06, 319. Number: 10 Publisher: Scientific Research Publishing, . [CrossRef]

- ZEL’DOVICH, I. Amplification of cylindrical electromagnetic waves reflected from a rotating body. Soviet Physics-JETP 1972, 35, 1085–1087.

- Unruh, W.G. Notes on black-hole evaporation. Phys. Rev. D 1976-08-15, 14, 870–892. [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The quantum theory of the electron. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1928-02, 117, 610–624. [CrossRef]

- Mignani, R.P.; Testa, V.; Caniulef, D.G.; Taverna, R.; Turolla, R.; Zane, S.; Wu, K.; Curto, G.L. Evidence of vacuum birefringence from the polarisation of the optical emission from an Isolated Neutron Star, 2018-02-14, [1710.08709 [astro-ph]].

- Pike, O.; Hill, E.; Rose, S.; Mackenroth, F. Observing the two-photon Breit-Wheeler process for the first time. In Proceedings of the APS Division of Plasma Physics Meeting Abstracts, 2014, Vol. 2014, pp. UO7–007.

- Anderson, P.W. Plasmons, gauge invariance, and mass. Physical Review 1963, 130, 439.

- Adler, R.J.; Casey, B.; Jacob, O.C. Vacuum catastrophe: An elementary exposition of the cosmological constant problem. American Journal of Physics 1995-07, 63, 620–626. [CrossRef]

| 1 | p.5-7 |

| 2 | p.36-41 |

| 3 | p.184 |

| 4 | p.128 |

| 5 | p.427-428 |

| Phase | Boundary Conditions | Klein-Gordon Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| (Discrete) | (Continuous) | |

| Bose | ||

| Bose-Fermi (HD) | ||

| Bose-Fermi (LD) | ||

| Fermi |

| Planck force | ||

|---|---|---|

| Color confinement force | ||

| Newtonian Gravitational force |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).