Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

05 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Sea pollution caused by anthropological activities represents a risk both for the organisms that inhabit it and for humans themselves. Great attention is paid to plastic waste because it takes decades to decompose and fragments into microscopic pieces that can be easily dispersed and ingested by marine fauna. Polymeric materials, in general, are rich in plasticizers (phthalates, PAEs; and bisphenol A, BPA), substances recognized as toxic both for aquatic organisms and for humans who could ingest them once contaminated marine organisms were to enter their diet. In this work, effective analytical protocols based on the use of solid phase microextraction (SPME) coupled with chromatography techniques were employed to evaluate the presence of PAEs and BPA in the extracted pulp of shrimps of the commercial species Aristaemorpha foliacea from 4 different fishing stations in the Mediterranean Sea. In addition to chemical analysis, a comprehensive microbiological characterization was carried out to assess microbiological risk due to shrimps’ consumption. This dual approach provides a more complete evaluation of the impact of human pollution on these crustaceans, revealing both chemical contamination and potential biological disruptions that could pose a danger to food safety.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

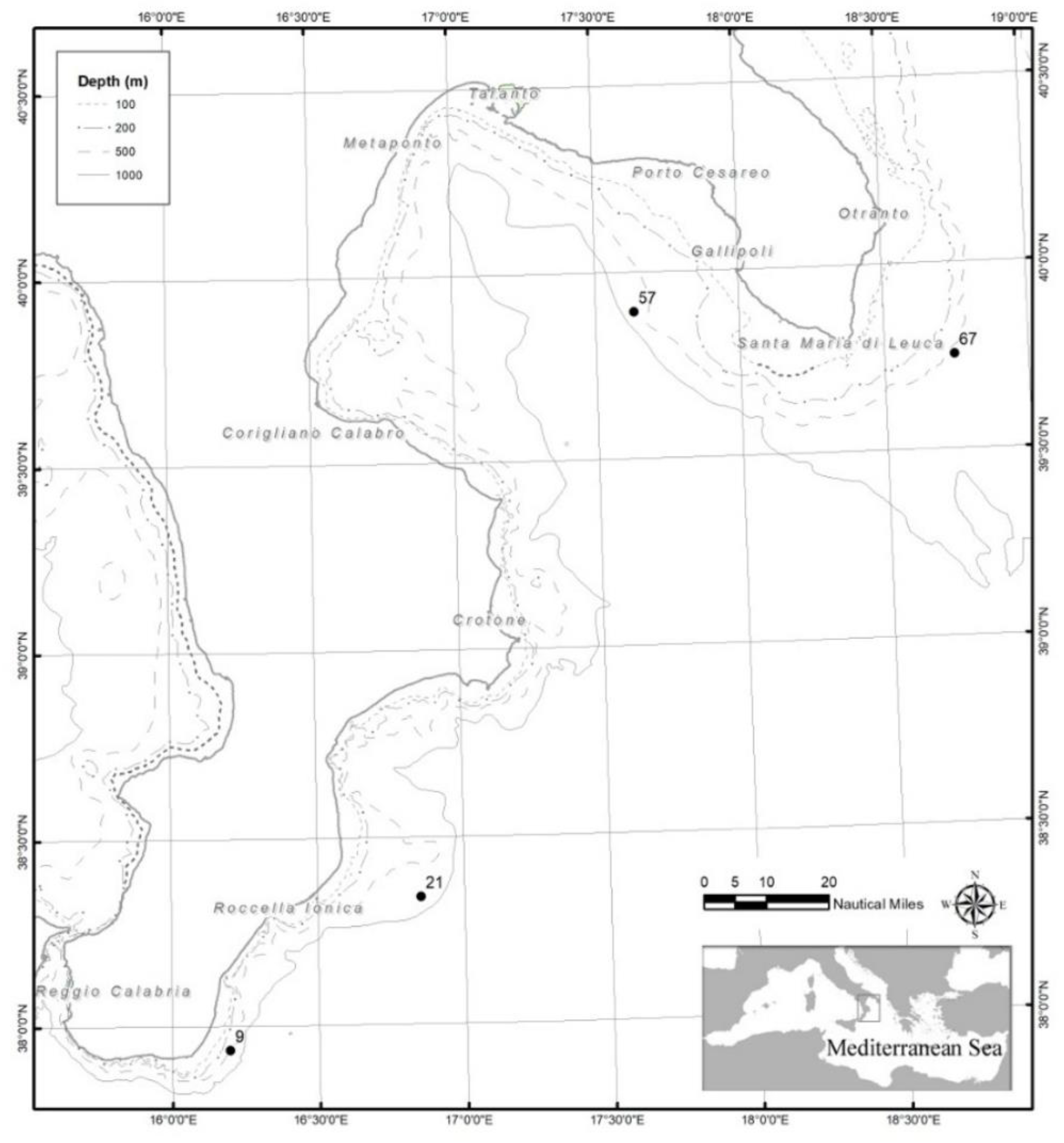

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Analytical Protocols for PAEs and BPA Determination

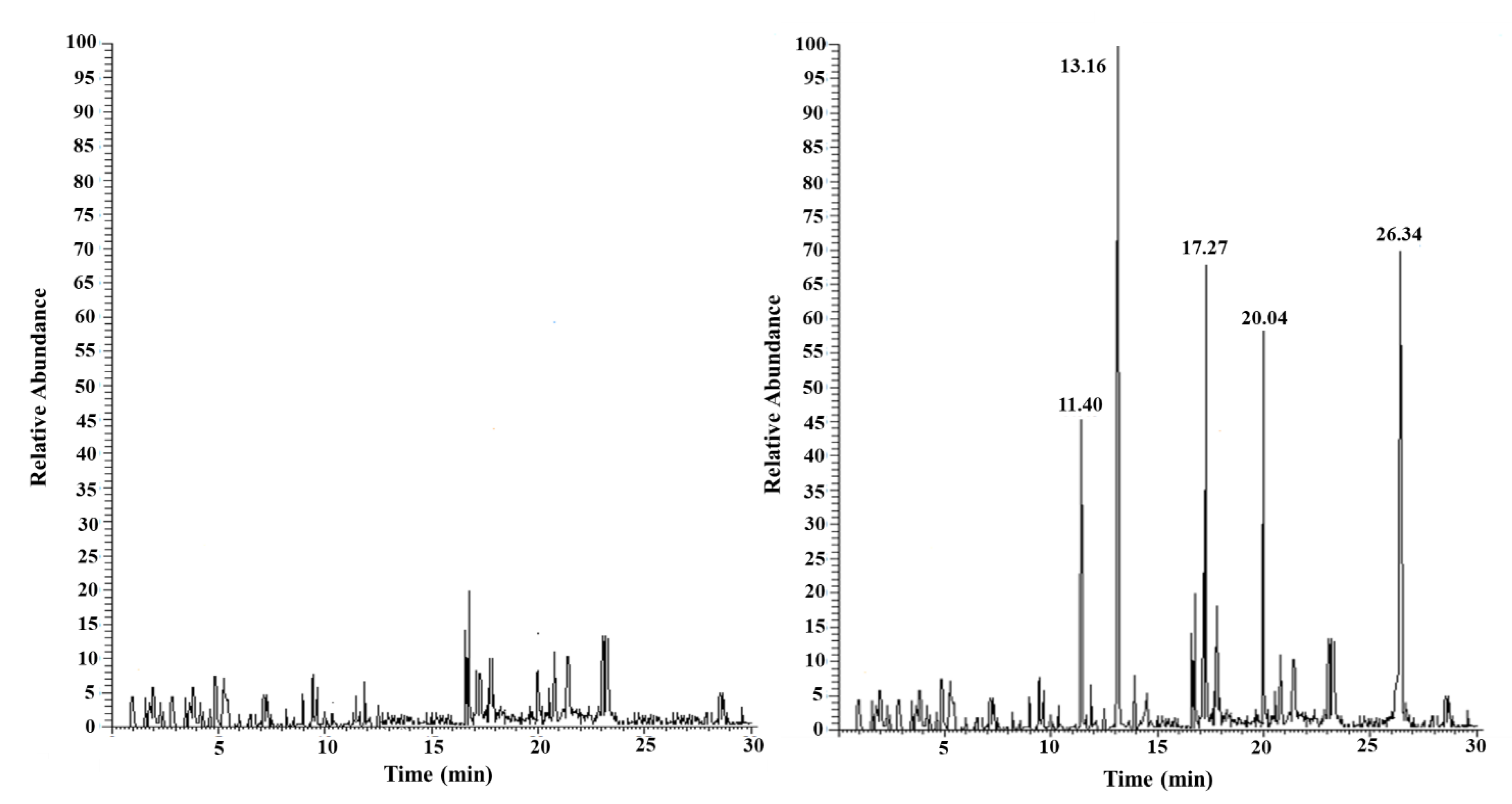

2.2.1. PAEs Determination

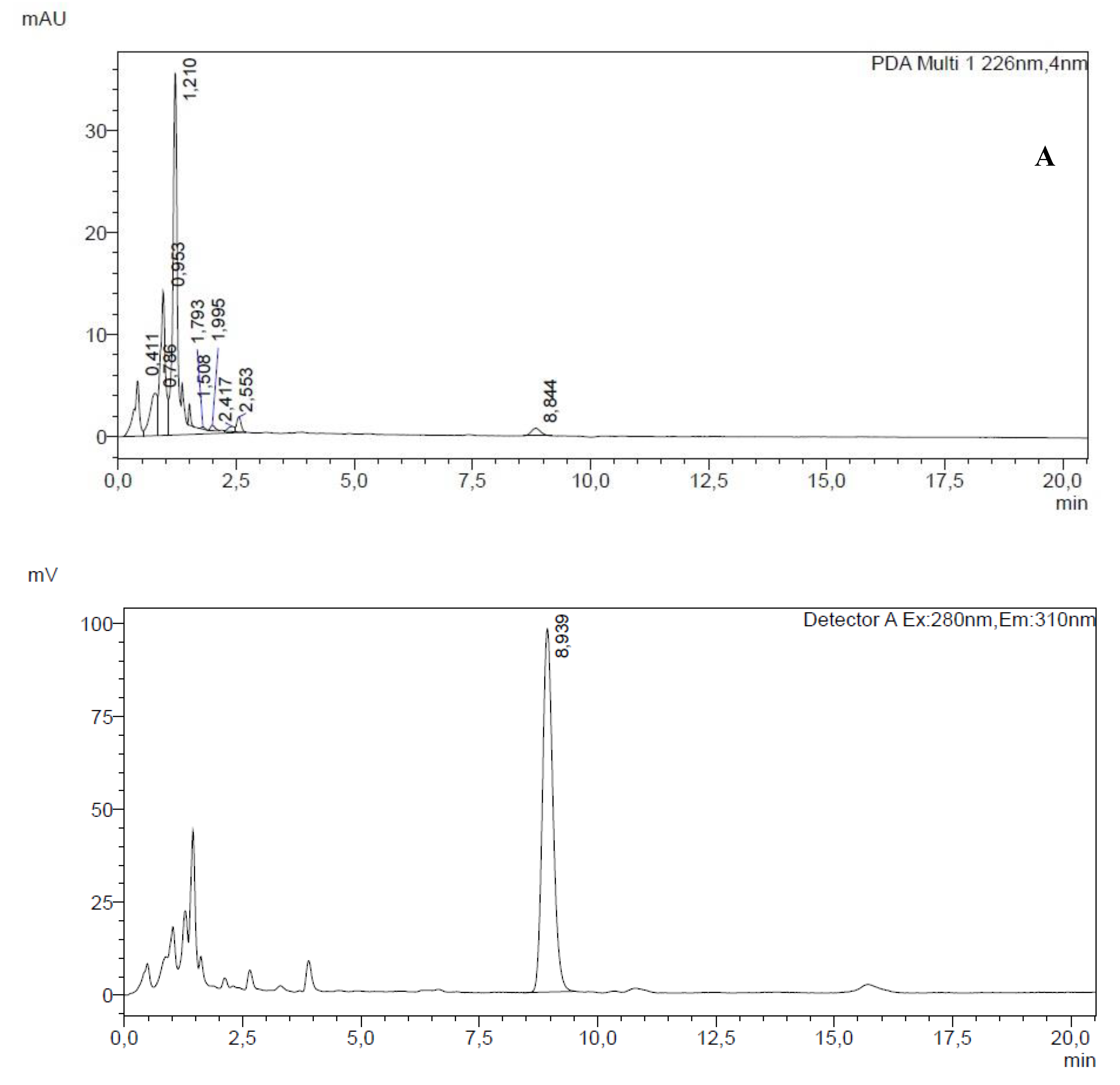

2.2.2. BPA Determination

2.3. Microbiological Characterization

2.3.1. Bacteria Investigation

2.3.2. Fungi Investigation

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1. PAEs and BPA Determination

3.2. Microbiological Investigation

4. Conclusions

Founding

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbalaei, S.; Hanachi, P.; Walker, T.R.; Cole, M. Occurrence, sources, human health impacts and mitigation of microplastic pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 36046–36063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galgani, L.; Tsapakis, M.; Pitta, P.; Tsiola, A.; Tzempelikou, E.; Kalantzi, I.; Esposito, C.; Loiselle, A.; Tsotskou, A.; Zivanovic, S.; Dafnomili, E.; Diliberto, S.; Mylona, K.; Magiopoulos, I.; Zeri, C.; Pitta, E.; Loiselle, S.A. Microplastics increase the marine production of particulate forms of organic matter. Environ. Res. Letters 2019, 14, 124085. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk, R.C.; Altinok, I. Interaction of plastics with marine species. Turkish J. of Fisheries and Aquatic Sci. 2020, 20, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanev, E.V.; Ricker. M. The fate of marine litter in semi-enclosed seas: a case study of the Black Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 660.

- Borrelle, S.B., Ringma, J., Lavender Law, K., Monnahan, C.C., Lebreton, L., McGivern, A., Murphy, E., Jambeck, J., Leonard, G.H., Hilleary, M.A., Eriksen, M., Possingham, H.P., De Frond, H., Gerber, L.R., Polidoro, B., Tahir, A., Bernard, M., Mallos, N., Barnes, M., Rochman, C.M. Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science 2020,1515–1518.

- https://www.futureagenda.org/foresights/plastic-oceans.

- Galgani, F.; Lusher, A.L.; Strand, J.; Haarr, M.L.; Vinci, M.; Jack, E.M.; Kagi, R.; Aliani, S.; Herzke, D.; Nikiforov, V.; Primpke, S.; Schmidt, N.; Fabres, F.; De Witte, B.; Solbakken, V.S.; Van Bavel, B. Revisiting the strategy for marine litter monitoring within the european marine strategy framework directive (MSFD). Ocean & Coastal Manag. 2024, 255, 107254. [Google Scholar]

- da Costa, J.P. Micro- and nanoplastics in the environment: research and policymaking. Current Opinion in Environ. Sci. & Health 2018, 1, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aransiola, S.A.; Ekwebelem, M.O.V.; Daza, B.X.; Oladoye, P.O.; Alli, Y.A.; Bamisaye, A.; Aransiola, A.B.; Oni, S.O.; Maddela, N.R. Micro- and nano-plastics pollution in the marine environment: Progresses, drawbacks and future guidelines, Chemosphere 2025, 374, 14421114.

- Hantoro, I. , Löhr, A. J., Van Belleghem, F. G. A. J., Widianarko, B., & Ragas, A. M. J. Microplastics in coastal areas and seafood: implications for food safety. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A 2019, 36, 674–711. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, H.C.; Lôbo-Hajdu, G. Microplastics in coastal and oceanic surface waters and their role as carriers of pollutants of emerging concern in marine organisms, Marine Environ. Res. 2023, 188, 106021. [Google Scholar]

- Pitacco, V.; Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Avio, C.G. 4 - Plastic impact on marine benthic organisms and food webs, Editor(s): Giuseppe Bonanno, Martina Orlando-Bonaca, Plastic Pollution and Marine Conservation, Academic Press 2022, 95-151.

- Cau, A.; Gorule, P.A.; Bellodi, A.; Carreras-Colom, E.; Moccia, D.; Pittura, L.; Regoli, F.; Follesa, M.C. Comparative microplastic load in two decapod crustaceans Palinurus elephas (Fabricius, 1787) and Nephrops norvegicus (Linnaeus, 1758). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 191, 114912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt-Holm, P.; N'Guyen, A. Ingestion of microplastics by fish and other prey organisms of cetaceans, exemplified for two large baleen whale species. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 44, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, K.; Su, L.; Li, J.; Yang, D.; Tong, C.; Mu, J.; Shi, H. Microplastics and mesoplastics in fish from coastal and fresh waters of China. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 221, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, K.; Gomez, V.; Torres, M.; Vera, L.; Nuñez, D.; Oyarzún, P.; Mendoza, G.; Clarke, B.; Fossi, M.C.; Baini, M.; Přibylová, P.; Klánová, J. Presence and characterization of microplastics in fish of commercial importance from the Biobío region in central Chile. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 140, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Santos, T.; Duarte, A.C. A critical overview of the analytical approaches to the occurrence, the fate and the behavior of microplastics in the environment. TrAC Trends in Anal. Chem. 2015, 65, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, N.; Reis-Santos, P.; Gillanders, B.M. Microplastic in fish – A global synthesis. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 2021, 31, 753–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Sobhan, F.; Uddin, M.N.; Sharifuzzaman, S.M.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Sarker, S.; Chowdhury, M.S.N. Microplastics in fishes from the Northern Bay of Bengal. Sci. of The Total Environ. 2019, 690, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, A.H.; Ronda, A.C.; Oliva, A.L.; Marcovecchio, J.E. Evidence of microplastic ingestion by fish from the Bahía Blanca estuary in Argentina, South America. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2019, 102, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanović, B. Ingestion of microplastics by fish and its potential consequences from a physical perspective. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2017, 13, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Fileman, E.; Halsband, C.; Goodhead, R.; Moger, J.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastic ingestion by zooplankton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 6646–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Halsband, C.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2588–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, S.; Cheng, Z.; Shi, K.; Zhang, C.; Shao, H. Phthalic acid esters: natural sources and biological activities. Toxins (Basel). 2021, 13, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunrath, R.; Cichna, M. Sample preparation including sol–gel immunoaffinity chromatography for determination of bisphenol A in canned beverages, fruits and vegetables. J. of Chrom. A 2005, 1062, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, H. Phthalates and their impacts on human health. Healthcare (Basel) 2021, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochester, J.R. Bisphenol A and human health: A review of the literature. Reproduct. Toxicol. 2013, 42, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/3190/oj/eng.

- Dumen, E.; Ekici, G.; Ergin, S.; Bayrakal, G.M. Presence of Foodborne Pathogens in Seafood and Risk Ranking for Pathogens. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2020, 17, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehel, J.; Yaucat-Guendi, R.; Darnay, L.; Palotás, P.; Laczay, P. Possible food safety hazards of ready-to-eat raw fish containing product (sushi, sashimi). Critical Reviews. Food Sci. and Nutrition 2020, 61, 867–888. [Google Scholar]

- Chintagari, S.; Hazard, N.; Edwards, G.; Jadeja, R.; Janes, M. Risks Associated with Fish and Seafood. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, B.; Bitetto, I.; D’Onghia, G.; Follesa, M.C.; Kapiris, K.; Mannini, A.; Markovic, O.; Micallef, R.; Ragonese, S.; Skarvelis, K.; Cau, A. Spatial and temporal patterns in the Mediterranean populations of Aristaeomorpha foliacea and Aristeus antennatus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Aristeidae) based on the MEDITS surveys. Scientia Marina 2019, 83S1, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onghia, G.; Maiorano, P.; Matarrese, A.; Tursi, A. Distribution, biology and population dynamics of Aristaeomorpha foliacea (Risso, 1827) (Crustacea, Decapoda) from the north-western Ionian Sea (Mediterranean Sea). Crustaceana 1998, 71(5), 518–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onghia, G.; Giove, A.; Maiorano, P.; Carlucci, R.; Minerva, M.; Capezzuto, F.; Sion, L.; Tursi, A. Exploring relationships between demersal resources and environmental factors in the Ionian Sea (Central Mediterranean). J. of Marine Biology 2012, 2, 279406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiorano, P.; Capezzuto, F.; Carluccio, A.; Calculli, C.; Cipriano, G.; Carlucci, R.; Ricci, P.; Sion, L.; Tursi, A.; D’Onghia, G. Food from the Depths of the Mediterranean: The Role of Habitats, Changesin the Sea-Bottom Temperature and Fishing Pressure. Foods 2022, 2022. 11, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soultani, G.; Sele, V.; Rasmussen, R.R.; Pasias, I.; Stathopoulou, E.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Sinanoglou, V.J.; Sloth, J.J. Elements of toxicological concern and the Arsenolipids’ profile in the giant-red Mediterranean shrimp, Aristaeomorpha foliacea. J. of Food Composition and Analysis 2021, 97, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Iglio, C. , Di Fresco, D. , Spanò, N., Albano, M., Panarello, G., Laface, F., Faggio, C., Capillo, G., Savoca, S., 2022. Occurrence of anthropogenic debris in three commercial shrimp species from south-western ionian sea. Biology 2022, 11, 1616. [Google Scholar]

- Chiacchio, L.; Cau, A.; Soler-Membrives, A.; Follesa, M.C.; Bellodi, A.; Carreras-Colom, E. Comparative assessment of microplastic ingestion among deep sea decapods: Distribution analysis in Sardinian and Catalan waters. Environ Res. 2025, 270, 120962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spedicato, M.T.; Massutí, E.; Mérigot, B.; Tserpes, G.; Jadaud, A.; Relini, G. 2019.The MEDITS TrawlSurvey Specifications in an Ecosystem Approach to Fishery Management. Sci. Mar. 2019, 83, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vietro, N.; Aresta, A.M.; Gubitosa, J.; Rizzi, V.; Zambonin, C. Assessing the conformity of plasticizer-free polymers for foodstuff packaging using solid phase microextraction coupled to gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Separations 2024, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lun, Y. Determination of sub-ppb level of phthalates in water by auto-SPME and GC–MS. Application 5989-7726EN; Agilent Technologies: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aresta, A.M.; De Vietro, N.; Mancini, G.; Zambonin, C. Effect of a chitosan-based packaging material on the domestic storage of “ready-to-cook” meat products: evaluation of biogenic amines production, phthalates migration, and in vitro antimicrobic activity’s impact on Aspergillus Niger. Separations 2024, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.A.; Coelho, L.A.; de Lourdes Cardeal, Z. Analysis of plasticiser migration to meat roasted in plastic bags by SPME–GC/MS. Food Chem. 2015, 178, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vietro, N.; Triggiano, F.; Cotugno, P.; Palmisani, J.; Di Gilio, A.; Zambonin, C.; de Gennaro, G.; Mancini, G.; Aresta, A.M.; Diella, G.; Marcotrigiano, V.; Trerotoli, P.; Marzocca, P.; Lorusso, L.; Spagnolo, A.M.; Sorrenti, G.T.; Lampedecchia, M.; Sorrenti, D.P.; D’Aniello, E.; Gramegna, M.; Nancha, A. Analytical investigation of phthalates and heavy metals in edible ice from vending machines connected to the Italian water supply. Foods 2024, 13, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, N.; Shaghel, J.A. A new analytical method for determination bisphenol A in canned meat. Reas. Square 2022, 1, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Salafranca, J.; Batlle, R.; Nerı́n, C. Use of solid-phase microextraction for the analysis of bisphenol A and bisphenol A diglycidyl ether in food simulants. J. of Chrom. A 1999, 864, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristiawan, Y.; Aryana, N.; Putri, D.; Styarini, D. Analytical method development for bisphenol A in tuna by using high performance liquid chromatography-UV. Proc. Chem. 2015, 16, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mita, L.; Bianco, M.; Viggiano, E.; Zollo, F.; Bencivenga, U.; Sica, V.; Monaco, G.; Portaccio, M.; Diano, N.; Colonna, A.; Lepore, M.; Canciglia, P.; Mita, D.G. Bisphenol A content in fish caught in two different sites of the Tyrrhenian Sea (Italy). Chemospere 2011, 82, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microbiologia Della Catena Alimentare—Metodo Orizzontale per la Conta dei Microrganismi—Parte 1: Conta Delle Colonie a 30 °C con la Tecnica Dell’inseminazione in Profondità. UNI EN ISO 4833-1:2013. 3 October 2013.

- Microbiologia di Alimenti e Mangimi per Animali—Metodo Orizzontale per la Conta di Escherichia coli beta Glucuronidasi-positiva—Parte 2: Tecnica Della Conta Delle Colonie a 44 °C che Utilizza 5-bromo-4-cloro-3- Indolil beta-D-glucuronide. UNI ISO 16649-2:2010. 28 April 2010.

- Microbiologia di Alimenti e Mangimi per Animali—Metodo Orizzontale per la Conta di Stafilococchi Coagulasi-positivi (Staphylococcus Aureus e Altre Specie)—Parte 1: Tecnica che Utilizza il Terreno Agar Baird-Parker. UNI EN ISO 6888-1:2018. 27 September 2018.

- Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae—Part 2: Colony-count Technique. ISO 21528-2:2017. June 2017.

- Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria Monocytogenes and of Listeria spp. Detection Method. ISO 11290-1:2017. May 2017.

- Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella Detection of Salmonella spp. ISO 6579-1:2017. February 2017.

- Microbiologia della catena alimentare - Metodo orizzontale per la determinazione di Vibrio spp - Parte 1: Ricerca delle specie di Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio cholerae e Vibrio vulnificus potenzialmente enteropatogene UNI EN ISO 21872-1:2023. 04 May 2023.

- Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs — Horizontal method for the enumeration of yeasts and moulds Part 1: Colony count technique in products with water activity greater than 0,95. ISO 21527-1:2008.

- Weaver, J.A.; Beverly, B.E.J.; Keshava, N.; Mudipalli, A.; Arzuaga, X.; Cai, C.; Hotchkiss, A.K.; Makris, S.L.; Yost, E.E. Hazards of diethyl phthalate (DEP) exposure: A systematic review of animal toxicology studies. Environ. Int. 2020, 145, 105848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Kong, H.; Shen, C.; She, G.; Tian, S.; Liu, H.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Xia, Q.; Liu, K. Dimethyl phthalate induced cardiovascular developmental toxicity in zebrafish embryos by regulating MAPK and calcium signaling pathways. Sci. of The Tot. Environ. 2024, 926, 171902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Regulation (EU). No 10/2011 on plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with food. Off. J. Eur. Comm. 2011, 12, 1–1394. [Google Scholar]

- https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:ministero.salute:decreto:2003-03-28;123.

- https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1442/oj/eng.

- Bordbar, L.; Sedlacek, P.; Anastasopoulou, A. Plastic pollution in the deep-sea Giant red shrimp, Aristaeomorpha foliacea, in the Eastern Ionian Sea; an alarm point on stock and human health safety. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162783. [Google Scholar]

| Area | Station code | Depth (m) | Latitude | Longitude |

| Southern Calabria | 9 | 543 | 3756163 N | 01611752 E |

| 21 | 656 | 3820496 N | 01651188 E | |

| Apulia | 57 | 592 | 3953622 N | 01738057 E |

| 67 | 527 | 3945234 N | 01844612 E |

| PAE | TR (min) | m/z |

| BBP DBP DEP DMP DnOP |

20.04±0.02 17.27±0.02 13.16±0.02 11.40±0.02 26.34±0.02 |

149, 206 [44] 149, 205, 223 [41,43,44,45] 105, 149, 177 [41,43,44,45] 135, 163, 194 [41,44,45] 149, 279 [44] |

| PAE | slope | Correlation coefficient (R2) | LOD (mg/Kg) | LOQ (mg/Kg) | Concentration level (mg/Kg) | |||||

|

Within-day 0.05 0.25 2.5 |

Between-day 0.05 0.25 2.5 |

|||||||||

| BBP | 707295 | 0.9940 | 0.030 | 0.100 | 22.1% | 21.0% | 19.7% | 30.7% | 28.8% | 27.6% |

| DBP | 501948 | 0.9965 | 0.023 | 0.076 | 20.3% | 21.6% | 22.0% | 33.8% | 34.3% | 30.2% |

| DEP | 6x106 | 0.9924 | 0.037 | 0.124 | 11.5% | 10.8% | 12.1% | 22.4% | 24.7% | 25.3% |

| DMP | 2x106 | 0.9940 | 0.033 | 0.110 | 13.7% | 12.5% | 11.9% | 23.5% | 25.5% | 22.3% |

| DnOP | 607682 | 0.9957 | 0.026 | 0.085 | 24.4% | 23.1% | 24.5% | 30.2% | 28.6% | 29.4% |

| MEDITERRANEAN SEA | BBP (MG/KG) | DBP (MG/KG) | DEP (MG/KG) | DMP (MG/KG) | DNOP (MG/KG) |

| ST_57 (SOUTH CALABRIA) | / | / | 0.145±0.003 | 0.162±0.003 | / |

| ST_67 (SOUTH CALABRIA) | / | / | 0.267±0.005 | 0.165±0.003 | / |

| ST_09 (APULIA) | / | / | 0.164±0.003 | 0.127±0.002 | / |

| ST_21 (APULIA) | / | 0.096±0.003 | 0.175±0.003 | 0.171±0.003 | / |

| MEDITERRANEAN SEA | BPA CONCENTRATION LEVEL (MG/KG) |

| ST_57 (SOUTH CALABRIA) | 0.0058±0.0003 |

| ST_67 (SOUTH CALABRIA) | 0.001±0.00006 |

| ST_09 (APULIA) | 0.0058±0.0003 |

| ST_21_ (APULIA) | 0.0075±0.0005 |

| Microorganism count (CFU/g) | ||||||

| Station | Total bacteria count | Total fungi count |

Escherichia coli |

Enterobacteriaceae |

positive-coagulase staphylococci |

Enterococci |

| 9 | 14000 | <1 | <1 | 160 | 3000 | <1 |

| 21 | 920 | <1 | <1 | 80 | 790 | <1 |

| 57 | 1610 | <1 | <1 | 220 | 1000 | 180 |

| 67 | 84000 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 7300 | 50 |

| Detection | ||||

| Station | Listeria monocytogenes | Salmonella spp. | Shiga Toxing-Producing E.coli | Vibrio spp. |

| 9 | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected |

| 21 | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected |

| 57 | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected |

| 67 | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).