1. Introduction

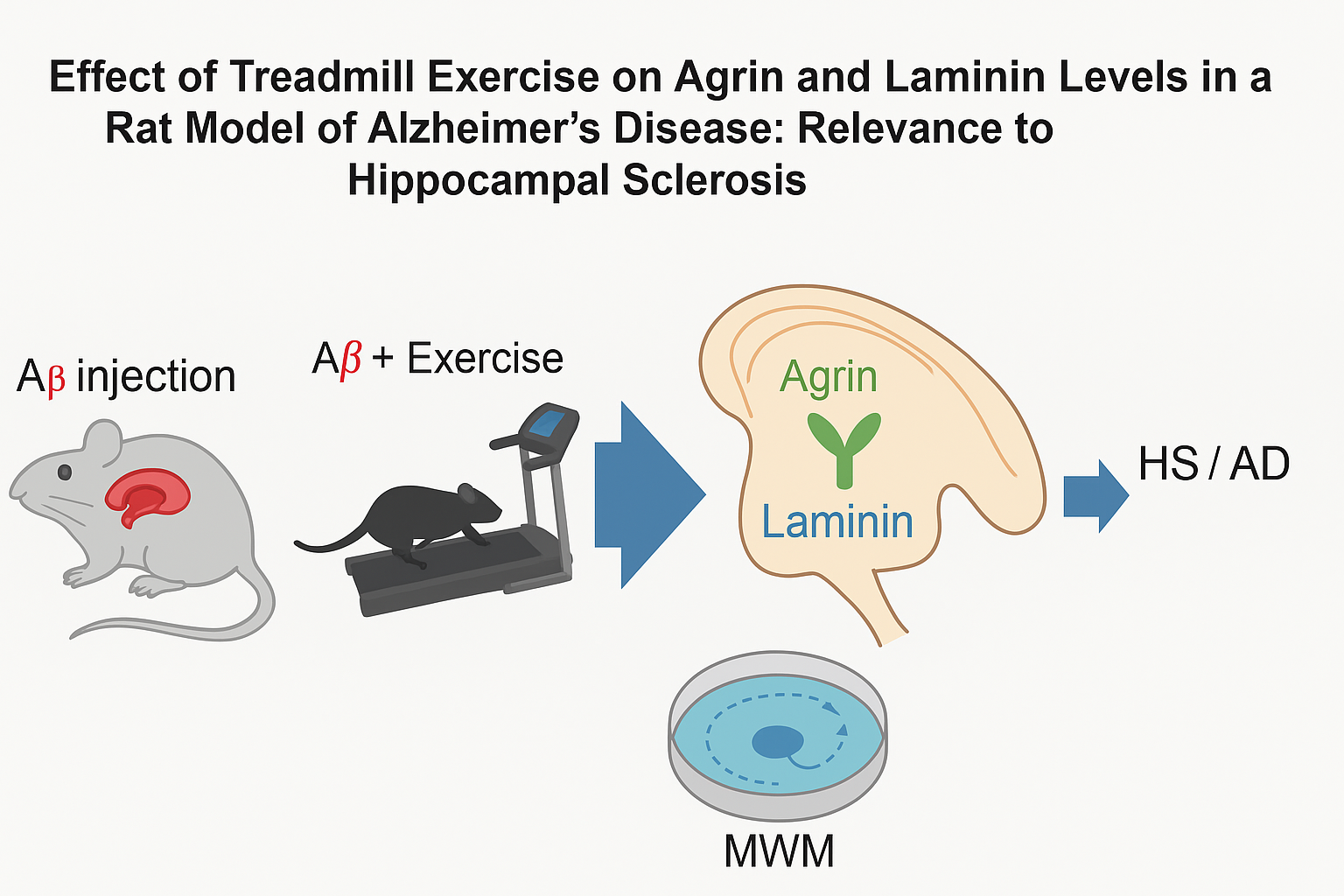

Alzheimer's disease (AD), a progressive multifactorial neurological disorder associated with age and lifestyle, is the most common form of dementia [

1]. A considerable loss of neurons and synapses with cognitive impairment is observed in patients with AD [

2,

3]. AD pathology is characterized by amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau tangles arising in the context of oxidative stress, inflammation, genetic susceptibility, and sedentary lifestyle [

4]. The hippocampus—critical for learning and memory—is among the earliest and most vulnerable regions to undergo neurodegenerative changes in AD [

5,

6].

Neurons and glia produce agrin, whose primary function is to maintain synapses in the central nervous system and at the neuromuscular junction [

7]. As a key component of the basal lamina, agrin regulates protein expression and blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability [

8,

9]; its degradation reduces synapse number in mature hippocampal cultures, underscoring its role in synaptogenesis [

8,

9]. Agrin is related to both senile plaques and tau tangles in the hippocampus [

10,

11]. Several studies suggest that soluble agrin in cerebrospinal fluid is involved in AD etiology as a heparan sulfate proteoglycan associated with fibrillar/non-fibrillar plaques, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and neurofibrillary tangles in autopsied AD tissue [

12,

13,

14].

Laminin, a basement-membrane glycoprotein, is widely distributed in the ECM and contributes to ECM assembly, synapse formation and guidance, neurite outgrowth, and growth-cone signaling [

15,

16].

Exercise enhances neuroplasticity; for example, voluntary wheel running increases cell proliferation in the rat hippocampus, while cognitive stimulation promotes survival of adult-born neurons [

17]. Exercise-induced neurotransmitters and neurotrophins support brain health. Evidence also indicates that agrin expression can be activity-dependent and that laminins help maintain BBB integrity and astrocyte endfoot polarization [

15,

16], [

18,

19].

Relevance to Hippocampal Sclerosis (HS). Hippocampal sclerosis is a neuropathologic entity defined by severe neuronal loss and gliosis predominantly in CA1 and subiculum [

20]. HS commonly co-occurs with late-life dementias—including pathologic AD—and is strongly associated with TDP-43 proteinopathy and accelerated hippocampal atrophy [

21,

22,

23]. While our model does not directly measure HS (e.g., neuronal loss/gliosis grading or TDP-43), agrin and laminin are core ECM constituents of the perivascular and perisynaptic compartments [

18,

24] and are altered in AD brains [

25,

26,

27]. Moreover, ECM remodeling is a recognized feature in hippocampal pathology, including epilepsy-related HS, where perineuronal-net integrity and matrix protease activity are disrupted [

28,

29,

30]. Therefore, quantifying agrin/laminin in this AD model provides mechanistic context potentially relevant to HS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

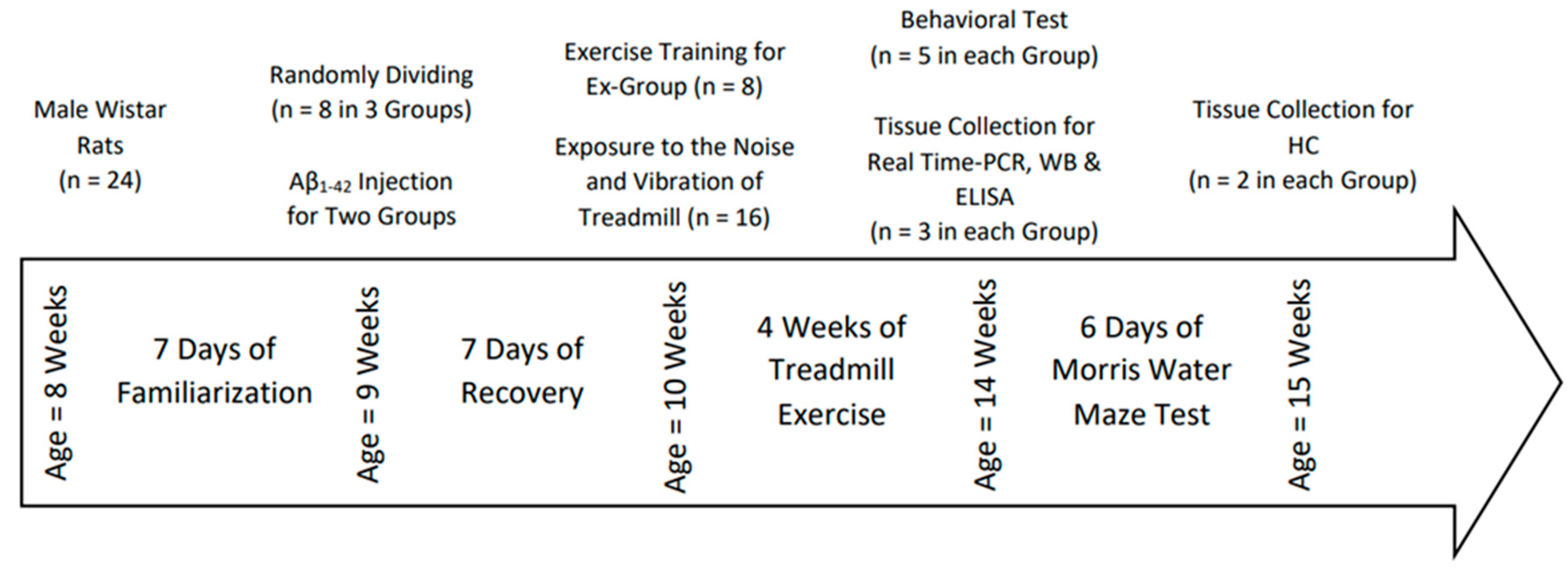

Male Wistar rats (n = 24; age = 8 weeks) were housed in a standard laboratory environment (12/12-h light/dark cycle at 22 ± 3°C, 45% relative humidity) with food and water available ad libitum. The Research Ethics Committee authorized all processes on Animal Experimentation at the University of Tehran.

After 1 week of familiarization, rats were acclimated to treadmill running (10 min, 10 m/min, 3 days/week). They were then randomized to Aβ1–42-injected (Aβ), Aβ + exercise (Aβ+Ex), or control groups (n=8/group). Seven days after injection to allow early AD-like changes [

31,

32], the Aβ+Ex group began 4 weeks of treadmill exercise; non-exercising groups were exposed to treadmill noise/vibration for equal durations.

- −

Exercise protocol: 5 days/week for 4 weeks; weeks 1–2: two 15-min intervals at 10 m/min; weeks 3–4: two 15-min intervals at 15 m/min.

- −

Behavior: The Morris water maze (MWM) and probe trial were performed to assess learning and memory. Twenty-four hours after the last session, a subset of rats was sacrificed for biochemical analyses; the remainder underwent behavioral testing followed by sacrifice.

- −

Biochemistry: Hippocampal agrin and laminin levels were measured using standard immunoassays (details as in original protocol).

Figure 1.

Timeline of Experimental for Aβ-injection, treadmill exercise, behavioral testing, and tissue collection.

Figure 1.

Timeline of Experimental for Aβ-injection, treadmill exercise, behavioral testing, and tissue collection.

The preparation procedure of Human β-amyloid1–42 (Abcam, cat. ab120301) included dissolving the peptide in 3% DMSO at 5 µg/µL, aliquoting (30 µL per vial), and storing at −80 °C until use. To induce fibril formation, aliquots were incubated at 37 °C for 7 days, as described previously[

33]. Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (25 mg/kg, i.p.) and secured in a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA). Burr holes were drilled at the hippocampal coordinates (AP: −3.8 mm, ML: ±2.2 mm from bregma; DV: −2.7 mm from skull surface)[

34]. Oligomerized Aβ1–42 was bilaterally infused at 5 µg/µL, 1 µL per hemisphere, using a 1 µL Hamilton syringe at ~0.2 µL/min (total 5 min infusion) followed by a 1 min dwell time before needle withdrawal to minimize backflow. The sham group underwent identical procedures, except that 1 µL/hemisphere of 3% DMSO vehicle was injected. Postoperative care was provided according to standard protocols.

2.2. Ethical Approval

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tehran in collaboration with the Pasteur Institute of Iran. The approval code was IR.UT.REC.1399.123. Animals were randomly assigned to experimental groups using a simple randomization procedure. Behavioral testing and histological analyses were performed by investigators blinded to group allocation to minimize bias.

2.3. Exercise Training Protocol

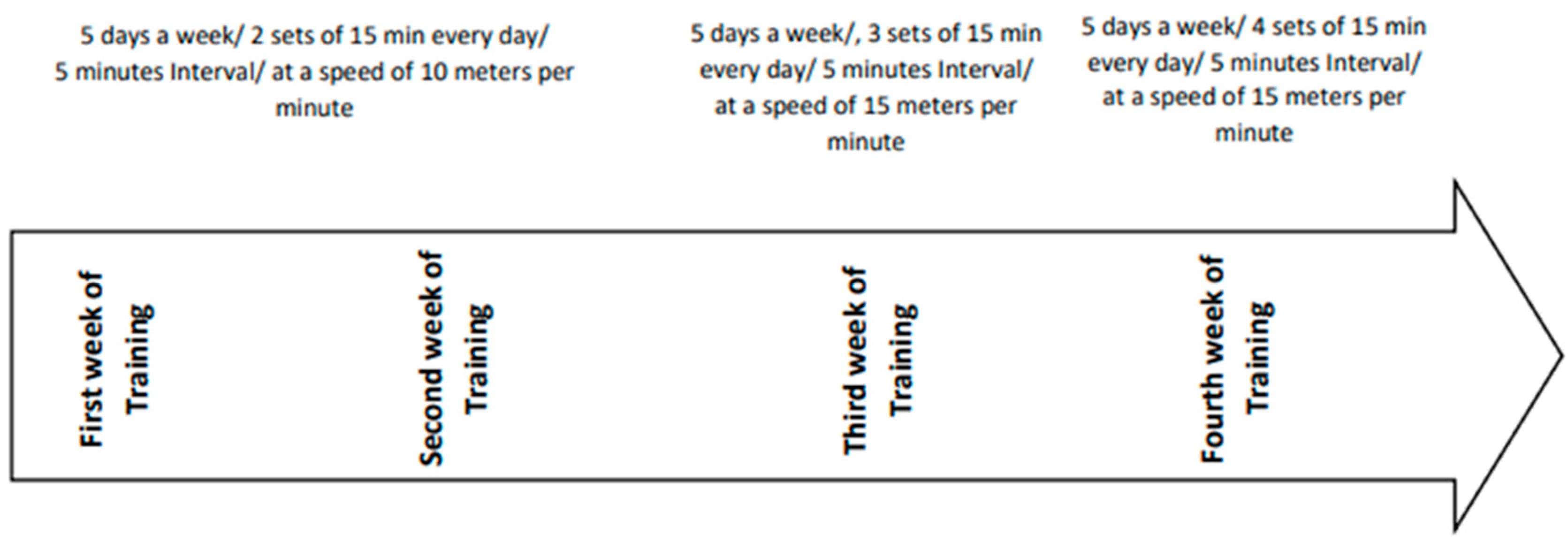

Rats performed forced Treadmill exercise at 0° incline between 9:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m., 5 days/ week, for 4 weeks with a previous protocol described by Zagaar et al [

18].

In short, the protocol was done on a treadmill with a speed of 10 m / min in the first and second weeks of exercise, in two 15 minutes intervals with 5 minutes rest between sets to prevent muscle fatigue in rats. Starting the third week, rats experienced an increase in duration and intensity of training to 3 intervals of 15 m / min, with 5 minutes breaks between each interval. In the fourth week, again, they encountered an increase in intensity and duration described as four 15-minute interval training following 5 minutes rest between each set of intervals. All rats during training protocols were carefully observed to ensure they have completed the exercise sessions and to monitor for any signs of pain or fatigue. To encourage the rats to continue completing the training, we used a weak electric shock (intensity 0.5 mA), which was not stressful to the animals [

18,

19]. The logic behind the reason why we have used this training protocol is that prior research has demonstrated this duration and intensity of exercise on rats' model of AD would have a preventive effect on memory and learning impairment [

35].

Figure 2.

Exercise Training Protocol during 4 weeks.

Figure 2.

Exercise Training Protocol during 4 weeks.

2.4. Behavioral Assessment

To assess the effect of forced exercise training on rats' cognitive and non-cognitive functions, we have conducted a series of behavioral tests in the following order; Morris Water Maze (MWM) is regularly used to measure the spatial memory and learning operation of the rat, and Probe test; is being used to measure total distance travel (cm), time spend in each quadrant (s), the number of platform crossing and time spend in platform zone (d) were recorded during the probe trail, and the visible platform test to assess the level of anxiety, locomotor activity , path finding, and navigation ability in rats, as previously described as previously described [

36]. The maze included a black-painted rounded pool (136 cm diameter, 60 cm height, depth 35 cm, and water temperature 22±2 °C). The pool was equally discrete into four quadrants (northeast (NE), northwest (NW), southeast (SE), and southwest (SW)). A Plexiglas hidden square platform (10 cm in diameter) was placed 1 cm under the surface of the water in the center of the (NW) quadrant (targeted area). Each experiment was recorded via a computerized video tracking system, and the data collected was analyzed using the EthoVision video tracking system (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands) by measuring time (escape latency), distance, and speed of swimming to find the platform. MWM was divided into two phases, Habituation phase: To familiarize the rats with the pool, they were allowed to swim for 60 s with no platform 24 h prior to the acquisition phase. Spatial Acquisition phase: Rats have been going under training to find the hidden platform located in the central NW quadrant. For this purpose, they were allowed to swim for 4 consecutive days; on each training day, the animals were given four trials of 60 s to find the platform. For each trial, the starting position was randomly selected, and each rat was given 90 s to detect the hidden platform. If the rats could reach the platform within the given time, they were authorized 20 s to stay on it. On the other hand, those who couldn't accomplish the task within 90 s were guided to the platform and given 20 s to rest. In order to minimize the effect of the Interfering variables, all the trials were performed each day roughly at the same time (6:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.). On day fifth, in order to evaluate the occupancy of the animal in the targeted quadrant proximity (hidden platform included), the post-training probe trial was performed. In the probe trial test, the hidden platform was removed; each rat was given 60 s to swim freely and was placed on the opposite side of the target quadrant in the pool. The ability to measure spatial memory was measured by the percentage of the time spent in the targeted quadrant and how many times the rats crossed the platform. To evaluate the visible test, by use of a piece of aluminum foil, the platform was covered and placed above the water surface in central (SE) quadrant.

Morris Water Maze (MWM). Spatial learning and memory were assessed using a circular pool with an invisible platform (submerged ~1–2 cm) in the target quadrant. Training consisted of 4 days of acquisition (4 trials/day, inter-trial interval ~60–90 s), followed 24 h later by a probe trial (platform removed). Primary outcomes were escape latency, path length, and % time in the target quadrant during the probe. Swimming trajectories were captured by a video-based tracking system and analyzed offline (software/version, blinded analysis). Exclusion criteria (e.g., floating or failure to engage) were predefined and applied prior to unblinding.

2.5. Method of Extract the Hippocampus and Measure Agrin, Laminin and Beta Amyloid

Analysis of genes and mRNA total RNAs was extracted from animals' hippocampus samples using a Tissue-Lyser LT (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and Trizol solution. Total RNA was specified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer to evaluate purity and concentration (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized among total RNA (Applied Biosystems, USA). By using the NCBI primer design device, primer sequences were designed.

All primers were bought from Pishgam Co., Iran. A 20 µl reaction mixture including10 µl SYBR-Green Master mix (Amplicon) and the proper concentrations of gene-specific primers added 1000 ng/µl of cDNA template were loaded in all well of a 96-well plate.

All PCR responses were performed in repetition. PCR was done under thermic conditions: 95 °C for 10 min, accompanied by 40 cycles 60 °C for 45s and of 95 °C for 15s. A division melt curve analysis was completed to verify the specificity of the PCR outcomes. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primers used to amplify the endogenous control output. The mRNA expression related values were examined using the formula -2

ΔΔCT[

37].

2.6. Molecular Analyses

qPCR. Total RNA was extracted from hippocampal tissue, reverse-transcribed to cDNA, and analyzed by quantitative PCR for MME, IDE, and LRP1, with GAPDH as the reference gene. Primer sequences/sources are listed in

Table 1. Reactions (total ~10–20 µL) were run under standard cycling conditions (e.g., 95 °C 10 min; 40 cycles of 95 °C 15 s, 60 °C 60 s). Relative expression was calculated using the 2^-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen).

Western Blot / ELISA. Hippocampal agrin and laminin were quantified by ELISA (manufacturer, catalog), following the supplier’s protocol; when applicable, protein normalization was performed to total protein (BCA) and signal linearity confirmed within the standard curve range. For any western blots, equal protein loads (~20–40 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF, probed with validated primary antibodies (vendor/clone/dilution), and detected chemiluminescently; band densities were normalized to housekeeping proteins.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were first screened for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and for homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test). For normally distributed outcomes, one-way ANOVA was applied, followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc comparisons when appropriate; effect sizes (η²) were reported for ANOVA. For non-normal data, the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons was used, with effect sizes (r) where applicable. All tests were two-tailed with α = 0.05. Analyses were conducted in SPSS v21 (IBM) and cross-checked in GraphPad Prism when needed.

3. Results

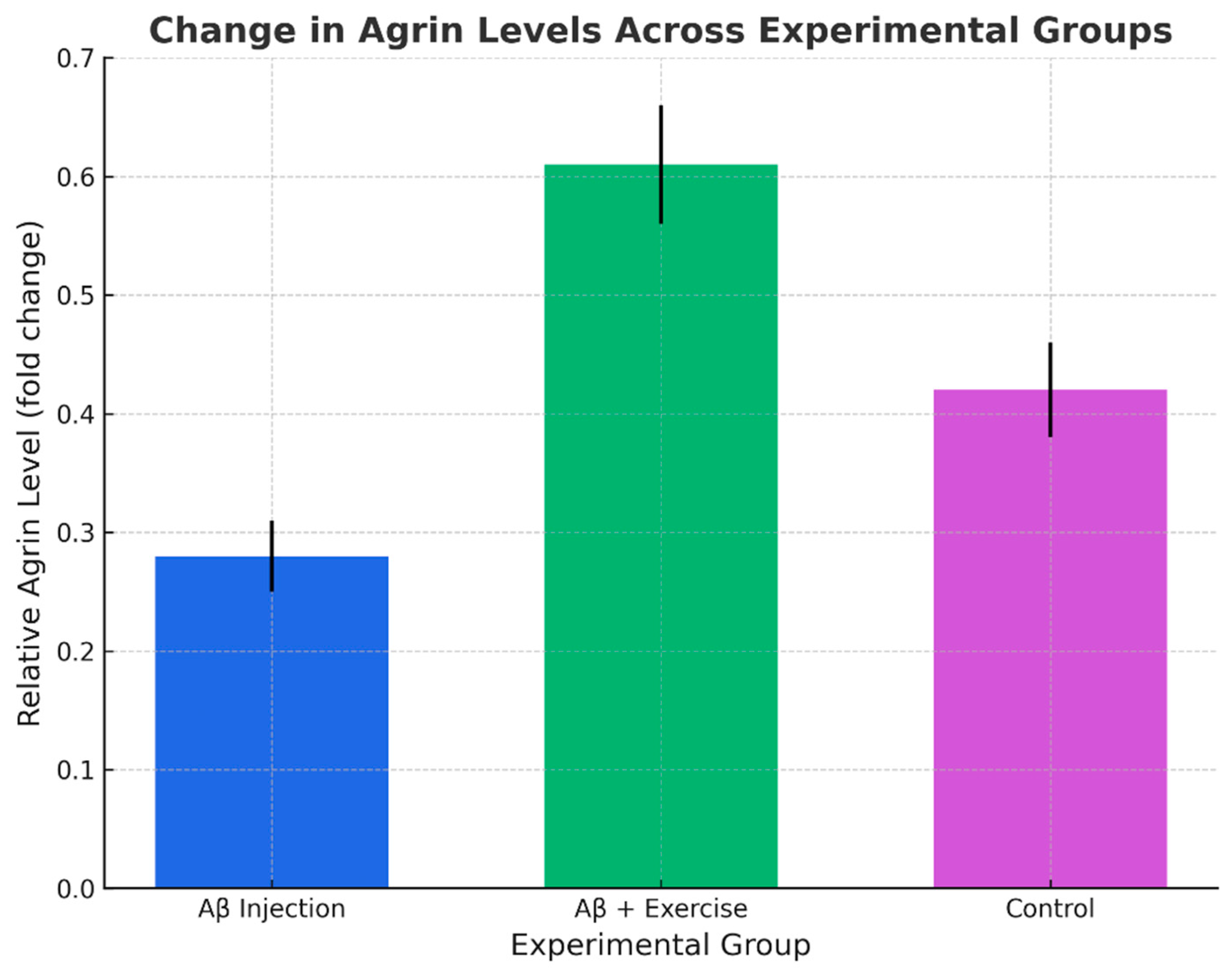

The one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in agrin levels among the three groups (p < 0.05, F(2,15) = 23.0932). Post hoc LSD tests indicated that the Aβ group had significantly lower agrin than both the Aβ+Ex group and controls (p < 0.05). In addition, the Aβ+Ex group also differed significantly from the control group (p < 0.05). These findings suggest that treadmill exercise following Aβ induction was able to partially restore agrin expression toward normal levels, despite the continued presence of amyloid pathology.

Quantitative PCR analysis revealed significant group differences in hippocampal expression of the ECM-related and Aβ-degrading genes MME, IDE, and LRP1. One-way ANOVA indicated a significant reduction in MME expression in the Aβ-injected group compared to both the Aβ+Ex and control groups (p < 0.01). Similarly, IDE levels were significantly lower in the Aβ group versus controls (p < 0.05), but partially restored in the Aβ+Ex group (p < 0.05 vs. Aβ). For LRP1, expression was also significantly downregulated by Aβ (p < 0.05) and partially rescued by exercise intervention. These results suggest that treadmill training mitigates Aβ-induced suppression of key genes involved in amyloid clearance and extracellular matrix maintenance.

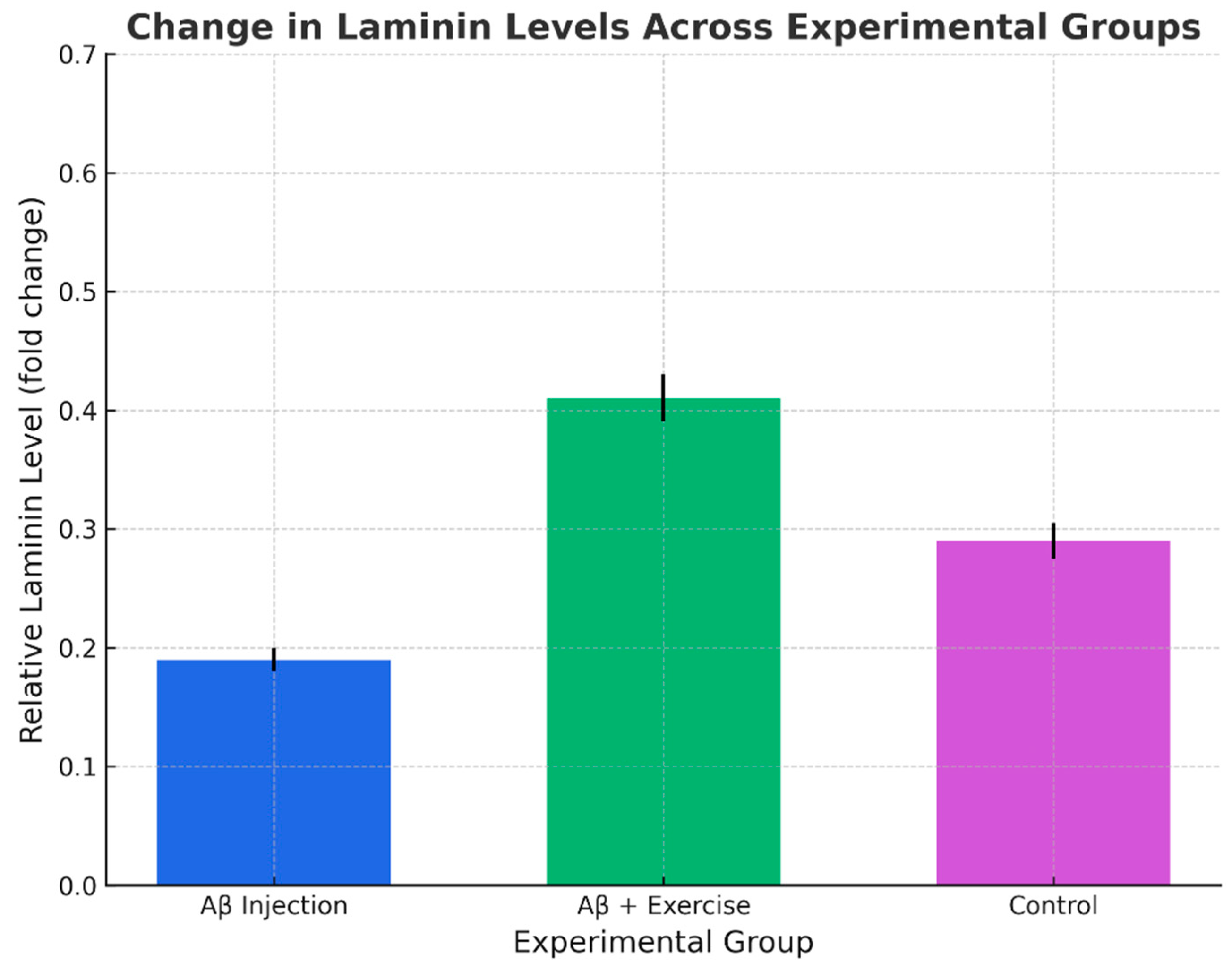

For laminin, there was a significant overall difference across the three groups (p < 0.002, F(2,15) = 10.129). Further LSD analysis showed that laminin was significantly higher in the Aβ+Ex group compared with Aβ (p < 0.001) and with controls (p < 0.010), whereas Aβ and control did not differ significantly (p = 0.164). Thus, laminin upregulation appears to be a specific response to exercise, rather than a direct effect of Aβ pathology.

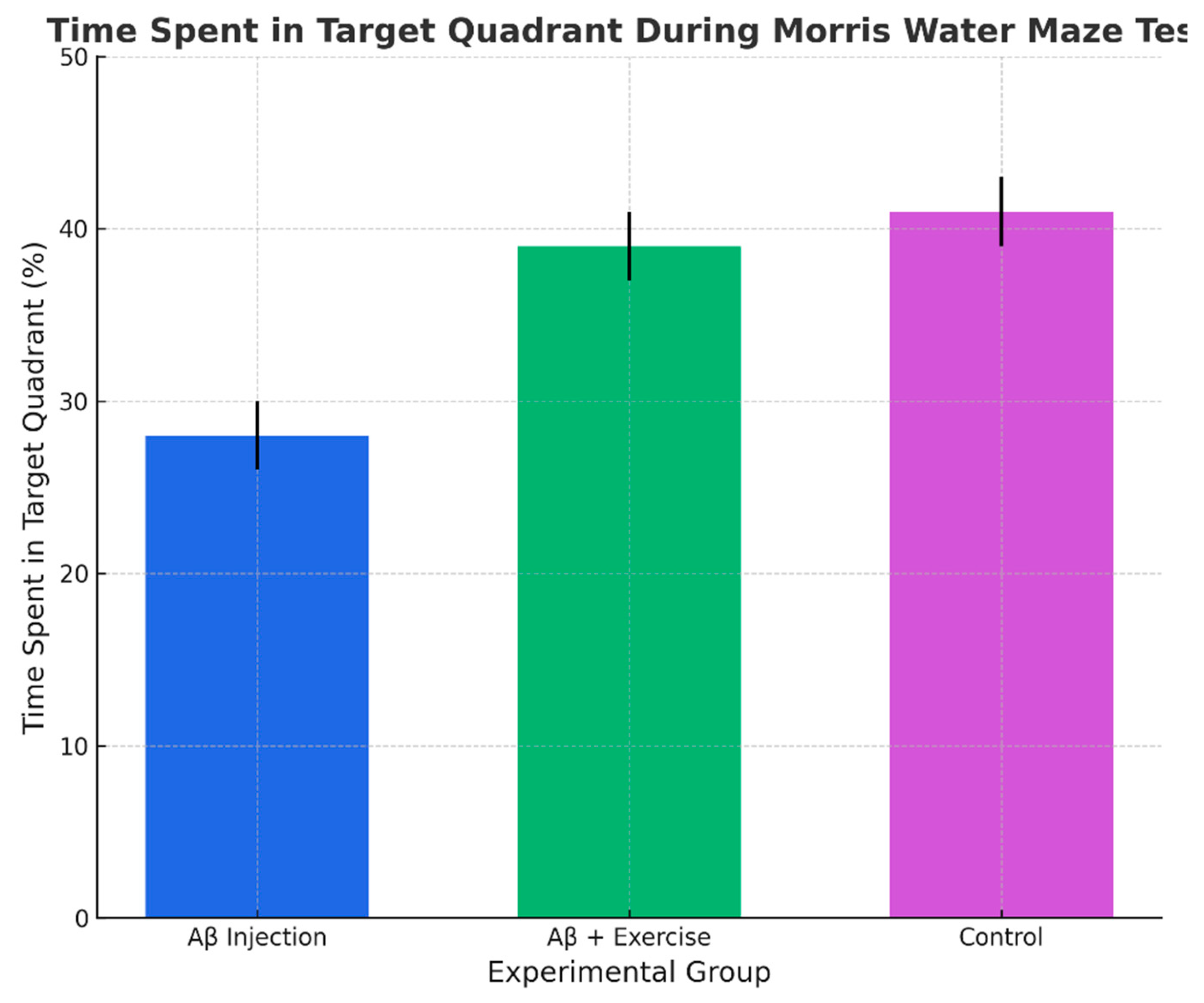

Analysis of the probe trial revealed a significant difference in the percentage of time spent in the target quadrant (p < 0.004, F(2,15) = 7.62). The Aβ+Ex group spent more time in the target quadrant than the Aβ group (p < 0.025) and controls (p < 0.005), but there was no difference between Aβ+Ex and controls (p = 1.000). This indicates that exercise attenuated the Aβ-induced impairment in spatial memory and restored performance to the level of healthy controls.

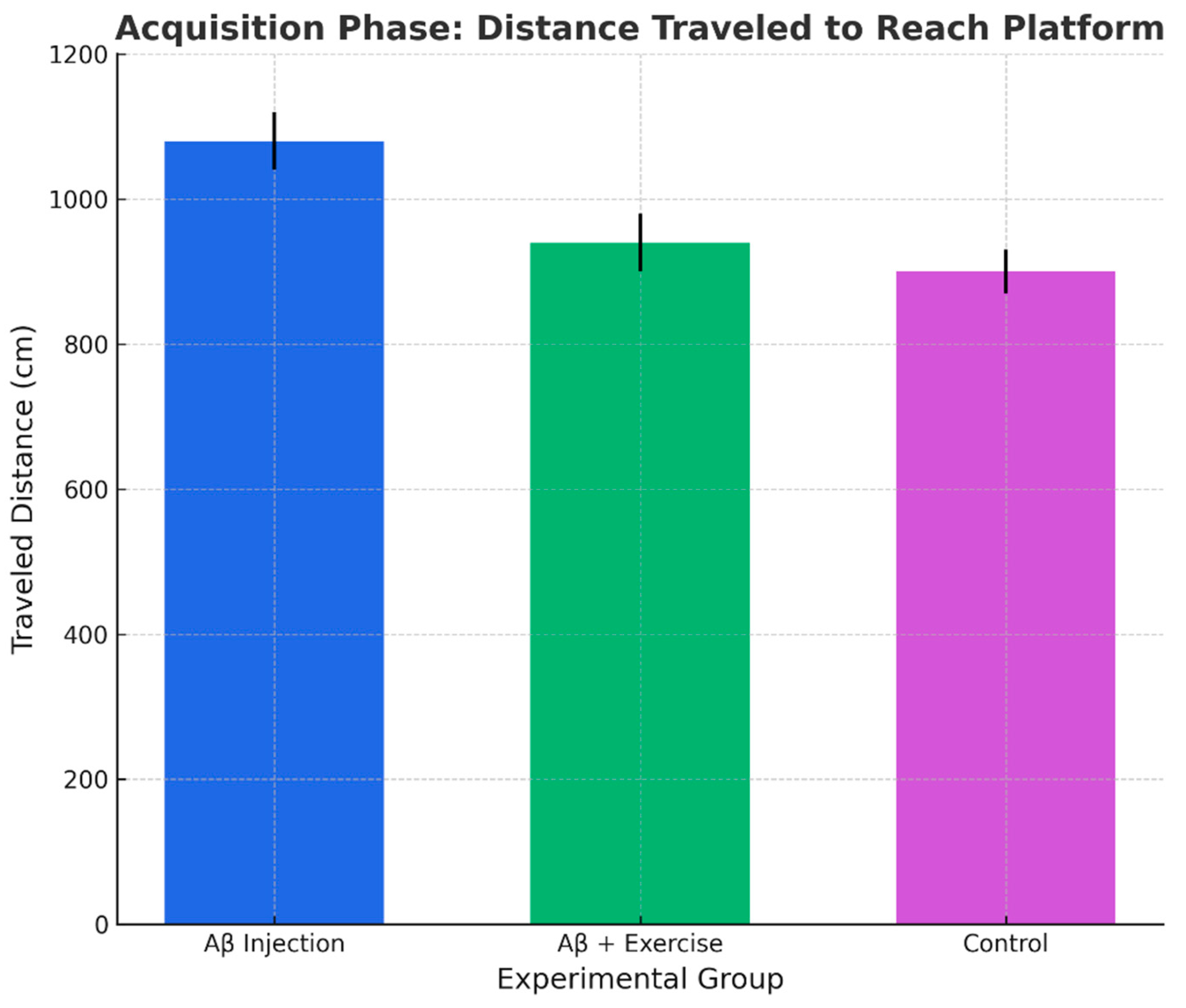

The distance traveled to reach the platform also differed significantly among groups (p < 0.000, F(2,15) = 34.64). Aβ rats traveled significantly longer distances than both Aβ+Ex and controls (p < 0.000), whereas Aβ+Ex did not differ from controls (p = 0.101). These data support the idea that treadmill exercise improved search efficiency and navigational accuracy.

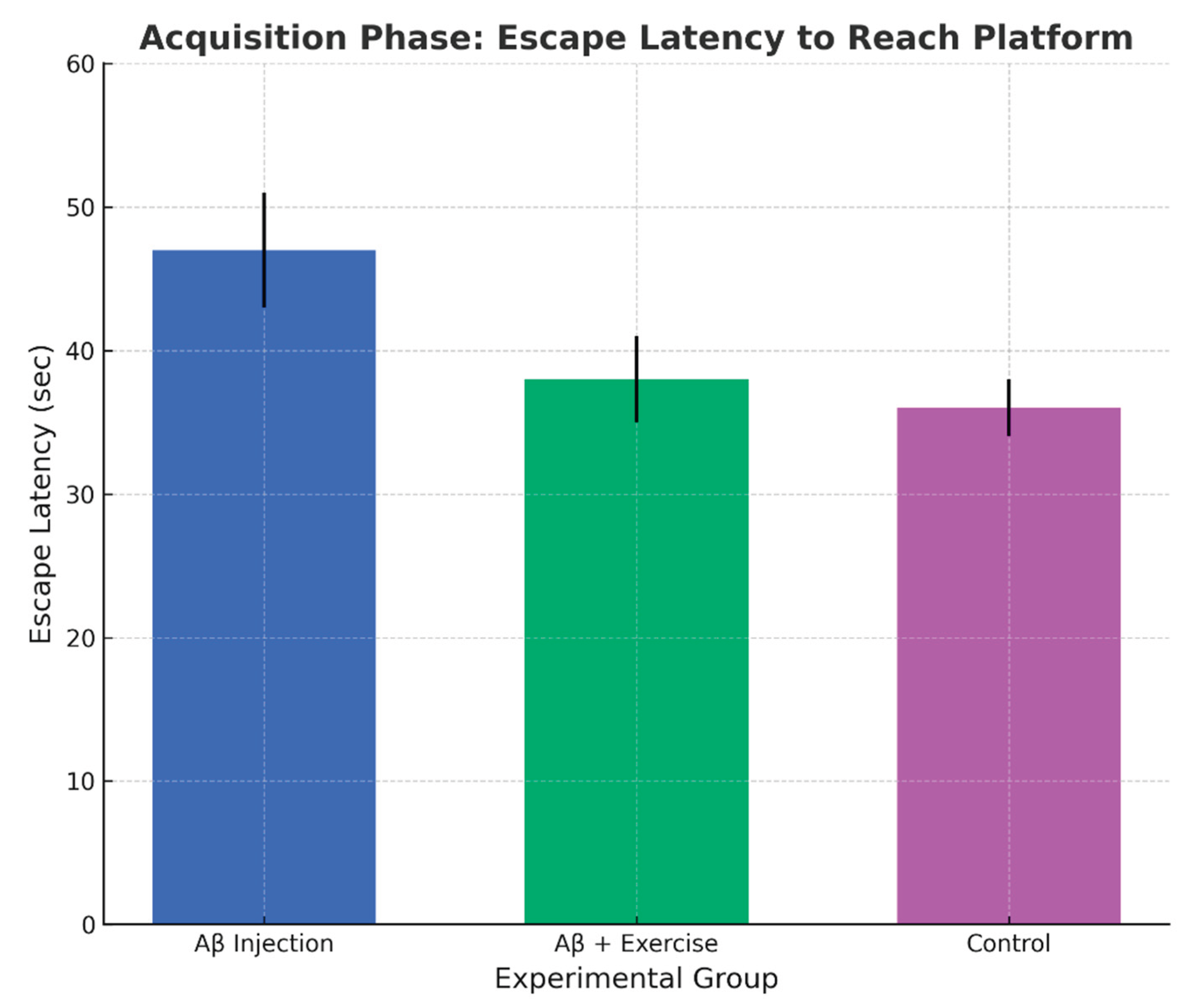

Finally, escape latency analysis showed a significant effect of group (p < 0.001, F(2,15) = 11.139). The Aβ+Ex group reached the platform faster than Aβ (p < 0.002) and controls (p < 0.000), but did not differ from controls (p = 0.351). Taken together, the behavioral measures converge to show that exercise mitigated Aβ-associated learning deficits.

Although hippocampal sclerosis was not directly assessed in this study (e.g., neuronal loss/gliosis or TDP-43 pathology), the observed exercise-induced increases in agrin and laminin provide indirect evidence of extracellular-matrix remodeling in the hippocampus. Such ECM changes are increasingly recognized as contributors to HS pathology, suggesting that the present findings may have relevance to hippocampal sclerosis.

Figure 3.

Change in hippocampal Agrin levels across groups (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group).

Figure 3.

Change in hippocampal Agrin levels across groups (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group).

Figure 4.

Change in hippocampal Laminin levels across groups (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group).

Figure 4.

Change in hippocampal Laminin levels across groups (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group).

Figure 5.

Percentage of time in target quadrant during probe (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group).

Figure 5.

Percentage of time in target quadrant during probe (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group).

Figure 6.

Distance traveled to reach the platform in acquisition (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group).

Figure 6.

Distance traveled to reach the platform in acquisition (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group).

Figure 7.

Escape latency to reach the platform in acquisition (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group). Note. Bars show mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. For outcomes that are not normally distributed, data are presented as median (IQR), and bars represent the median with IQR.

Figure 7.

Escape latency to reach the platform in acquisition (mean ± SEM, n = 8/group). Note. Bars show mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. For outcomes that are not normally distributed, data are presented as median (IQR), and bars represent the median with IQR.

4. Discussions

Our findings demonstrate that post-induction treadmill exercise significantly increased hippocampal agrin and laminin levels in an Aβ-based rat model of AD, alongside improvements in spatial learning and memory. These results are consistent with the growing body of literature suggesting that physical activity exerts neuroprotective effects through modulation of extracellular-matrix (ECM) components and synaptic remodeling.

Agrin has long been recognized as a key organizer of the neuromuscular junction [

38], [

39], but accumulating evidence extends its role to the central nervous system. It is expressed by both neurons and glia [

12], participates in synaptogenesis, and contributes to blood–brain barrier integrity [

8,

9]. In the context of AD, agrin colocalizes with amyloid plaques and tau tangles [

12,

13,

14], [

15,

16], and may facilitate Aβ fibrillization while limiting its clearance [

40]. Human post-mortem studies have reported altered agrin levels in the hippocampus of AD patients [

8,

9], although results remain somewhat inconsistent [

41]. The present study supports the hypothesis that physical exercise can enhance agrin expression in the hippocampus, which in turn may stabilize synaptic contacts and mitigate Aβ-related synaptic toxicity.

Laminins are large heterotrimeric glycoproteins that form a major structural component of the basal lamina. They regulate neuronal adhesion, axonal growth, and synapse formation [

42] [

43], [

44], [

45]. In the peripheral nervous system, laminins are critical for Schwann cell function and neuromuscular junction maintenance [

46,

47]. Within the brain, laminin expression is upregulated in response to injury and in neurodegenerative conditions such as AD and Down syndrome [

34]. Notably, laminin has been shown to modulate Aβ polymerization and may act as an inhibitor of amyloid fibril formation [

18,

24]. Our results show that treadmill exercise further increases hippocampal laminin in Aβ-injected rats, suggesting that exercise promotes ECM remodeling that counteracts AD-related pathology.

The biochemical changes observed were paralleled by behavioral improvements. Exercised rats exhibited shorter escape latencies and reduced path lengths in the Morris water maze, as well as increased time in the target quadrant during the probe trial. These findings indicate that treadmill exercise not only altered ECM protein expression but also translated into functional gains in spatial memory. Together, the results reinforce the view that exercise is a potent non-pharmacological intervention for preserving cognitive function in AD.

Hippocampal sclerosis (HS) is a common age-related neuropathology, characterized by CA1/subiculum neuronal loss and gliosis, and frequently comorbid with late-life dementia [

20]. HS is strongly associated with TDP-43 pathology [

21,

22,

23], which accelerates hippocampal atrophy and worsens cognitive decline. ECM dysregulation has been implicated in HS, particularly in temporal lobe epilepsy, where alterations in laminin and perineuronal nets contribute to synaptic reorganization and neuronal vulnerability [

28,

29,

30].

Although we did not directly assess HS-defining features (neuronal loss, gliosis, or TDP-43 pathology), the observed exercise-induced increases in agrin and laminin provide indirect evidence of ECM stabilization processes that may also be relevant to HS. By strengthening perisynaptic and perivascular microenvironments, exercise may counteract molecular cascades that underlie HS progression.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

The study has limitations. We did not quantify neuronal survival, astrocytic or microglial activation, or TDP-43 deposition, which are essential for a direct diagnosis of HS. We also did not localize agrin and laminin changes to specific hippocampal subregions (e.g., CA1 vs. dentate gyrus) using immunohistochemistry. Future studies should integrate stereological assessments, ECM mapping, and HS staging to determine whether exercise prevents or delays the onset of HS-like pathology in AD and epilepsy models. Longitudinal designs in aged animals or in transgenic AD models would also help establish the temporal relationship between ECM remodeling, HS markers, and cognitive outcomes.

6. Conclusions

In summary, treadmill exercise after Aβ induction enhances hippocampal agrin and laminin levels and improves memory performance in rats. These findings reinforce the role of ECM remodeling as a mediator of exercise-induced neuroprotection in AD. Moreover, they suggest a potential link to hippocampal sclerosis, highlighting the importance of investigating exercise as a strategy not only for AD but also for related pathologies where HS is a key contributor.

Author Contributions

Supervision: AliAsghar Ravasi, Siroos Choobineh. Project administration: AliAsghar Ravasi, Siroos Choobineh. Conceptualization: Maryam Sadeghi, Anali Kanani. Methodology: Maryam Sadeghi, Anali Kanani. Investigation: Anali Kanani. Formal analysis: Maryam Sadeghi. Data curation: Maryam Sadeghi. Writing—original draft: Maryam Sadeghi, Anali Kanani. Writing—review & editing: Maryam Sadeghi. Visualization (figures/graphic design): Maryam Sadeghi. Funding acquisition: Anali Kanani.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tehran in collaboration with the Pasteur Institute of Iran (Approval ID: IR.UT.REC.1399.123).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the University of Tehran. We thank the laboratory staff for their technical assistance and all colleagues who provided helpful discussions during the course of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| BBB |

Blood–brain barrier |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ECM |

Extracellular matrix |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FASEB |

Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology |

| GABAA |

Gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor |

| GAPDH |

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GCSF |

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

| HC |

Hippocampus |

| HS |

Hippocampal sclerosis |

| IDE |

Insulin-degrading enzyme |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| KUMC |

University of Kansas Medical Center |

| LRP1 |

Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 |

| LSD |

Least significant difference |

| MME |

Membrane metallo-endopeptidase (neprilysin) |

| MWM |

Morris water maze |

| NCBI |

National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NMDA |

N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| REM |

Rapid eye movement |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| SEM |

Standard error of the mean |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TDP-43 |

TAR DNA-binding protein 43 |

| WB |

Western blot |

References

- Musiek, E.S.; Holtzman, D.M. Three dimensions of the amyloid hypothesis: time, space and 'wingmen'. Nat Neurosci 2015, 18, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow, K.; de Leon, M.J.; Zetterberg, H. Alzheimer's disease. The Lancet 2006, 368, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeKosky, S.T.; Scheff, S.W. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer's disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol 1990, 27, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, A.; Keegan, R.M.; Deshmukh, R. Recent advances in the neurobiology and neuropharmacology of Alzheimer's disease. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 98, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.M.; Kelly, A.M. Exercise as a pro-cognitive, pro-neurogenic and anti-inflammatory intervention in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev 2016, 27, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufson, E.J.; Mahady, L.; Waters, D.; Counts, S.E.; Perez, S.E.; DeKosky, S.T.; Ginsberg, S.D.; Ikonomovic, M.D.; Scheff, S.W.; Binder, L.I. Hippocampal plasticity during the progression of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience 2015, 309, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, L.T.; Lauterborn, J.C.; Gall, C.M.; Smith, M.A. Localization and alternative splicing of agrin mRNA in adult rat brain: transcripts encoding isoforms that aggregate acetylcholine receptors are not restricted to cholinergic regions. The Journal of Neuroscience 1994, 14, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskery, S.; Bailey, A.; Lin, L.; Daniels, M.P. Transmembrane agrin regulates dendritic filopodia and synapse formation in mature hippocampal neuron cultures. Neuroscience 2009, 163, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ksiazek, I.; Burkhardt, C.; Lin, S.; Seddik, R.; Maj, M.; Bezakova, G.; Jucker, M.; Arber, S.; Caroni, P.; Sanes, J.R.; et al. Synapse loss in cortex of agrin-deficient mice after genetic rescue of perinatal death. J Neurosci 2007, 27, 7183–7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.H.; Cummings, B.J.; Cotman, C.W. Localization of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan and proteoglycan core protein in aged brain and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience 1992, 51, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gool, D.; David, G.; Lammens, M.; Baro, F.; Dom, R. Heparan sulfate expression patterns in the amyloid deposits of patients with Alzheimer's and Lewy body type dementia. Dementia 1993, 4, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Hilgenberg, L.G. Agrin in the CNS: a protein in search of a function? Neuroreport 2002, 13, 1485–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, M.M.; Otte-Höller, I.; van den Born, J.; van den Heuvel, L.P.W.J.; David, G.; Wesseling, P.; de Waal, R.M.W. Agrin Is a Major Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan Accumulating in Alzheimer's Disease Brain. The American Journal of Pathology 1999, 155, 2115–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, J.E.; Berzin, T.M.; Rafii, M.S.; Glass, D.J.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Fallon, J.R.; Stopa, E.G. Agrin in Alzheimer's disease: altered solubility and abnormal distribution within microvasculature and brain parenchyma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 6468–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venstrom, K.A.; Reichardt, L.F. Extracellular matrix. 2: Role of extracellular matrix molecules and their receptors in the nervous system. FASEB J 1993, 7, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luckenbill-Edds, L. Laminin and the mechanism of neuronal outgrowth. Brain Research Reviews 1997, 23, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curlik, D.M., 2nd; Shors, T.J. Training your brain: Do mental and physical (MAP) training enhance cognition through the process of neurogenesis in the hippocampus? Neuropharmacology 2013, 64, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagaar, M.; Alhaider, I.; Dao, A.; Levine, A.; Alkarawi, A.; Alzubaidy, M.; Alkadhi, K. The beneficial effects of regular exercise on cognition in REM sleep deprivation: behavioral, electrophysiological and molecular evidence. Neurobiol Dis 2012, 45, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, A.T.; Zagaar, M.A.; Alkadhi, K.A. Moderate Treadmill Exercise Protects Synaptic Plasticity of the Dentate Gyrus and Related Signaling Cascade in a Rat Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Mol Neurobiol 2015, 52, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, P.T.; Smith, C.D.; Abner, E.L.; Wilfred, B.J.; Wang, W.X.; Neltner, J.H.; Baker, M.; Fardo, D.W.; Kryscio, R.J.; Scheff, S.W.; et al. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta Neuropathol 2013, 126, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Yu, L.; Capuano, A.W.; Wilson, R.S.; Leurgans, S.E.; Bennett, D.A.; Schneider, J.A. Hippocampal sclerosis and TDP-43 pathology in aging and Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2015, 77, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, B.D.; Wilson, R.S.; Boyle, P.A.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Bennett, D.A.; Schneider, J.A. TDP-43 stage, mixed pathologies, and clinical Alzheimer's-type dementia. Brain 2016, 139, 2983–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneses, A.; Koga, S.; O'Leary, J.; Dickson, D.W.; Bu, G.; Zhao, N. TDP-43 Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease. Mol Neurodegener 2021, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, A.T.; Zagaar, M.A.; Alkadhi, K.A. Correction to: Moderate Treadmill Exercise Protects Synaptic Plasticity of the Dentate Gyrus and Related Signaling Cascade in a Rat Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Mol Neurobiol 2018, 55, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtomaki, S.; Risteli, J.; Risteli, L.; Koivisto, U.M.; Johansson, S.; Liesi, P. Laminin and its neurite outgrowth-promoting domain in the brain in Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome patients. J Neurosci Res 1992, 32, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfman, F.C.; Garrido, J.; Alvarez, A.; Morgan, C.; Inestrosa, N.C. Laminin inhibits amyloid-β-peptide fibrillation. Neuroscience Letters 1996, 218, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.; Inestrosa, N.C. Interactions of laminin with the amyloid beta peptide. Implications for Alzheimer's disease. Braz J Med Biol Res 2001, 34, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifeld, J.; Förster, E.; Reiss, G.; Hamad, M.I.K. Considering the Role of Extracellular Matrix Molecules, in Particular Reelin, in Granule Cell Dispersion Related to Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 917575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitaš, B.; Bobić-Rasonja, M.; Mrak, G.; Trnski, S.; Krbot Skorić, M.; Orešković, D.; Knezović, V.; Petelin Gadže, Ž.; Petanjek, Z.; Šimić, G.; et al. Reorganization of the Brain Extracellular Matrix in Hippocampal Sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoddevik, E.H.; Rao, S.B.; Zahl, S.; Boldt, H.B.; Ottersen, O.P.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M. Organisation of extracellular matrix proteins laminin and agrin in pericapillary basal laminae in mouse brain. Brain Struct Funct 2020, 225, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.J.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, K.L.; Jung, J.S.; Huh, S.O.; Suh, H.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Song, D.K. Protection against beta-amyloid peptide toxicity in vivo with long-term administration of ferulic acid. Br J Pharmacol 2001, 133, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Medhi, B.; Chopra, K. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) improves memory and neurobehavior in an amyloid-beta induced experimental model of Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2013, 110, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doost Mohammadpour, J.; Hosseinmardi, N.; Janahmadi, M.; Fathollahi, Y.; Motamedi, F.; Rohampour, K. Non-selective NSAIDs improve the amyloid-beta-mediated suppression of memory and synaptic plasticity. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2015, 132, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner-Ennever, J. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 3rd edn. By George Paxinos and Charles Watson. (Pp. xxxiii+80; illustrated; f$69.95 paperback; ISBN 0 12 547623; comes with CD-ROM.) San Diego: Academic Press. 1996. Journal of Anatomy 1997, 191, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, A.T.; Zagaar, M.A.; Levine, A.T.; Salim, S.; Eriksen, J.L.; Alkadhi, K.A. Treadmill exercise prevents learning and memory impairment in Alzheimer's disease-like pathology. Curr Alzheimer Res 2013, 10, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heysieattalab, S.; Naghdi, N.; Zarrindast, M.R.; Haghparast, A.; Mehr, S.E.; Khoshbouei, H. The effects of GABAA and NMDA receptors in the shell-accumbens on spatial memory of METH-treated rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2016, 142, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, J.; Barzaghi, P.; Lin, S.; Bezakova, G.; Lochmuller, H.; Engvall, E.; Muller, U.; Ruegg, M.A. An agrin minigene rescues dystrophic symptoms in a mouse model for congenital muscular dystrophy. Nature 2001, 413, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanes, J.R.; Marshall, L.M.; McMahan, U.J. Reinnervation of muscle fiber basal lamina after removal of myofibers. Differentiation of regenerating axons at original synaptic sites. J Cell Biol 1978, 78, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotman, S.L.; Halfter, W.; Cole, G.J. Agrin binds to beta-amyloid (Abeta), accelerates abeta fibril formation, and is localized to Abeta deposits in Alzheimer's disease brain. Mol Cell Neurosci 2000, 15, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossenkoppele, R.; Mattsson, N.; Teunissen, C.E.; Barkhof, F.; Pijnenburg, Y.; Scheltens, P.; van der Flier, W.M.; Rabinovici, G.D. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and cerebral atrophy in distinct clinical variants of probable Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2015, 36, 2340–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gingras, J.; Rassadi, S.; Cooper, E.; Ferns, M. Agrin plays an organizing role in the formation of sympathetic synapses. J Cell Biol 2002, 158, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domogatskaya, A.; Rodin, S.; Tryggvason, K. Functional diversity of laminins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2012, 28, 523–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajevardi, M.; Behnam-Rassouli, M.; Mahdavi-Shahri, N.; Abdolmaleki, A.; Mahdizadeh, A.H. Biocompatibility of Blastema Cells Derived from Rabbit’s Pinna on Chitosan/Gelatin Micro-Nanofiber Scaffolds. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, R.W. Response of sensory neurites and growth cones to patterned substrata of laminin and fibronectin in vitro. Developmental Biology 1987, 121, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, B.L. Laminins of the neuromuscular system. Microscopy Research and Technique 2000, 51, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimune, H.; Sanes, J.R.; Carlson, S.S. A synaptic laminin-calcium channel interaction organizes active zones in motor nerve terminals. Nature 2004, 432, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Used for Gene Expression Analysis.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Used for Gene Expression Analysis.

| Gene |

F/R |

Primer (5′→3′) |

Accession Number |

| MME |

F |

GCCTCAGCCGAAACTACAAG |

XM_017590630.1 |

| MME |

R |

ATAAAGCCTCCCACAGCAT |

|

| IDE |

F |

AACACCTCGGCTACCAGGA |

XM_017588831.1 |

| IDE |

R |

AGAAGGTTCACCTGCTGTT |

|

| LRP-1 |

F |

CTACAACGAGTTGCTCAGCC |

XM_008765393.1 |

| LRP-1 |

R |

GTTTCCCAGTGCGTCCAGTA |

|

| GAPDH |

F |

AAGTTCAACGGCACAGTCAAGG |

XM_017593963.1 |

| GAPDH |

R |

CATACTCAGCACCCAGCATCACC |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).