Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Definitions and Measurements

2.3. Objectives

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Data Management

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Lp(A) | Lipoprotein(A) |

| LDL-C | Low density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HDL-C | High density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HR | Hazard Ration |

| STEMI | ST-Elevation myocardical infarction |

| NSTEMI | Non-ST- Elevation myocardical infarction |

| RR | Relative risk |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| P | P-value |

References

- Tsimikas S. A Test in Context: Lipoprotein(a): Diagnosis, Prognosis, Controversies, and Emerging Therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2017 Feb 14 [cited 2024 Sep 11];69(6):692–711. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28183512/.

- Meyers HP, Bracey A, Lee D, Lichtenheld A, Li WJ, Singer DD, et al. Comparison of the ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) vs. NSTEMI and Occlusion MI (OMI) vs. NOMI Paradigms of Acute MI. Journal of Emergency Medicine [Internet]. 2021 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Aug 25];60(3):273–84. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33308915/. [CrossRef]

- Buciu IC, Tieranu EN, Pircalabu AS, Istratoaie O, Zlatian OM, Cioboata R, et al. Exploring the Relationship Between Lipoprotein (a) Level and Myocardial Infarction Risk: An Observational Study. Medicina 2024, Vol 60, Page 1878 [Internet]. 2024 Nov 16 [cited 2024 Nov 18];60(11):1878. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/60/11/1878/htm. [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, F. Lipoprotein(a). Handb Exp Pharmacol [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Sep 13];270:201–32. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36122123/.

- Țieranu EN; Cureraru SI; Târtea GC; Vlăduțu V-C; Cojocaru PA; Piorescu MTL; Dincă D; Popescu R; Militaru C; Donoiu I;.; et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction and Diffuse Coronary Artery Disease in a Patient with Multiple Sclerosis: A Case Report and Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4304. [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru A; Zavaleanu AD; Călina DC; Gheonea DI; Osiac E; Boboc IKS; Militaru C; Militaru S; Buciu IC; Țieranu EN;.; et al. Different Age Related Neurological and Cardiac Effects of Verapamil on a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Health Sci. J. 2021, 47, 263–269. [CrossRef]

- Volgman AS, Koschinsky ML, Mehta A, Rosenson RS. Genetics and Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Lipoprotein(a)-Associated Cardiovascular Risk. J Am Heart Assoc [Internet]. 2024 Jun 18 [cited 2025 Aug 25];13(12):33654. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1161/JAHA.123.033654?download=true. [CrossRef]

- Zaheen M, Pender P, Dang QM, Sinha E, Chong JJH, Chow CK, et al. Myocardial Infarction in the Young: Aetiology, Emerging Risk Factors, and the Role of Novel Biomarkers. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 2025, Vol 12, Page 148 [Internet]. 2025 Apr 10 [cited 2025 Aug 25];12(4):148. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2308-3425/12/4/148/htm. [CrossRef]

- Młynarska E, Czarnik W, Fularski P, Hajdys J, Majchrowicz G, Stabrawa M, et al. From Atherosclerotic Plaque to Myocardial Infarction—The Leading Cause of Coronary Artery Occlusion. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, Vol 25, Page 7295 [Internet]. 2024 Jul 2 [cited 2025 Aug 25];25(13):7295. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/13/7295/htm. [CrossRef]

- Baumann AAW, Tavella R, Air TM, Mishra A, Montarello NJ, Arstall M, et al. Prevalence and real-world management of NSTEMI with multivessel disease. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther [Internet]. 2022 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Aug 25];12(1):11–11. Available from: https://cdt.amegroups.org/article/view/89578/html. [CrossRef]

- Patel D, Koschinsky ML, Agarwala A, Natarajan P, Bhatia HS, Mehta A, et al. Role of Lipoprotein(a) in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in South Asian Individuals. J Am Heart Assoc [Internet]. 2025 Jul 15 [cited 2025 Aug 25];14(14):eJAHA. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1161/JAHA.124.040361?download=true. [CrossRef]

- Buciu IC, Tieranu EN, Pircalabu AS, Zlatian OM, Donoiu I, Militaru C, et al. The Relationship between Lipoprotein A and the Prevalence of Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease in Young Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: An Observational Study. Biomedicines [Internet]. 2024 Sep 1 [cited 2024 Oct 13];12(9). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39335672/. [CrossRef]

- Lopes Almeida Gomes L, Forman Faden D, Xie L, Chambers S, Stone C, Werth VP, et al. Modern therapy of patients with lupus erythematosus must include appropriate management of their heightened rates of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events: a literature update. Lupus Sci Med [Internet]. 2025 Apr 8 [cited 2025 Aug 25];12(1):e001160. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11979607/.

- Reyes-Soffer G, Yeang C, Michos ED, Boatwright W, Ballantyne CM. High lipoprotein(a): Actionable strategies for risk assessment and mitigation. Am J Prev Cardiol [Internet]. 2024 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Aug 25];18:100651. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11031736/. [CrossRef]

- Shiyovich A, Berman AN, Besser SA, Biery DW, Kaur G, Divakaran S, et al. Association of Lipoprotein (a) and Standard Modifiable Cardiovascular Risk Factors With Incident Myocardial Infarction: The Mass General Brigham Lp(a) Registry. Journal of the American Heart Association: Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Disease [Internet]. 2024 May 31 [cited 2025 Aug 25];13(10):e034493. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11179826/. [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas S, Fazio S, Ferdinand KC, Ginsberg HN, Koschinsky ML, Marcovina SM, et al. NHLBI Working Group Recommendations to Reduce Lipoprotein(a)-Mediated Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Aortic Stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Jan 16;71(2):177–92. [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, P.A.; Țieranu, M.L.; Piorescu, M.T.L.; Buciu, I.C.; Belu, A.M.; Cureraru, S.I.; Țieranu, E.N.; Moise, G.C.; Istratoaie, O. Myocardical Infarction in Young Adults: Revisiting Risk Factors and Atherothrombotic Pathways. Medicina 2025, 61, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoiu I, Târtea G, Sfredel V, Raicea V, Țucă AM, Preda AN, Cozma D, Vătășescu R. Dapagliflozin Ameliorates Neural Damage in the Heart and Kidney of Diabetic Mice. Biomedicines. 2023 Dec 16;11(12):3324. [CrossRef]

- Dhankhar S, Chauhan S, Mehta DK, Nitika, Saini K, Saini M, Das R, Gupta S, Gautam V. Novel targets for potential therapeutic use in Diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023 Feb 13;15(1):17. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | STEMI n= 88 No. (%) Median(IQR) |

NSTEMI n= 63 No. (%) Median(IQR) |

CONTROL n=40 No. (%) Median(IQR) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender |

Men |

72(81,8%) |

48(76,2%) |

20 (50%) |

< 0,001 |

| Women |

16 (18,2%) |

15( 23,8%) |

20 (50%) |

< 0,001 |

|

| AGE | 48,0 (43,8 – 54,2) | 50,0 (46,0 – 53,0) | 34,0 (29,0 – 40,0) | < 0,001 | |

|

BMI |

Standard |

27 (30,7 %) |

12 (19,0 %) |

20 (64,3 %) |

< 0,001 |

| Overweight |

16 (18,2 %) |

42 (66,7 %) |

10 (23,8 %) |

< 0,001 |

|

| Obesity | 45 (51,1 %) | 9 (14,3 %) | 10 (23,8 %) | < 0,001 | |

|

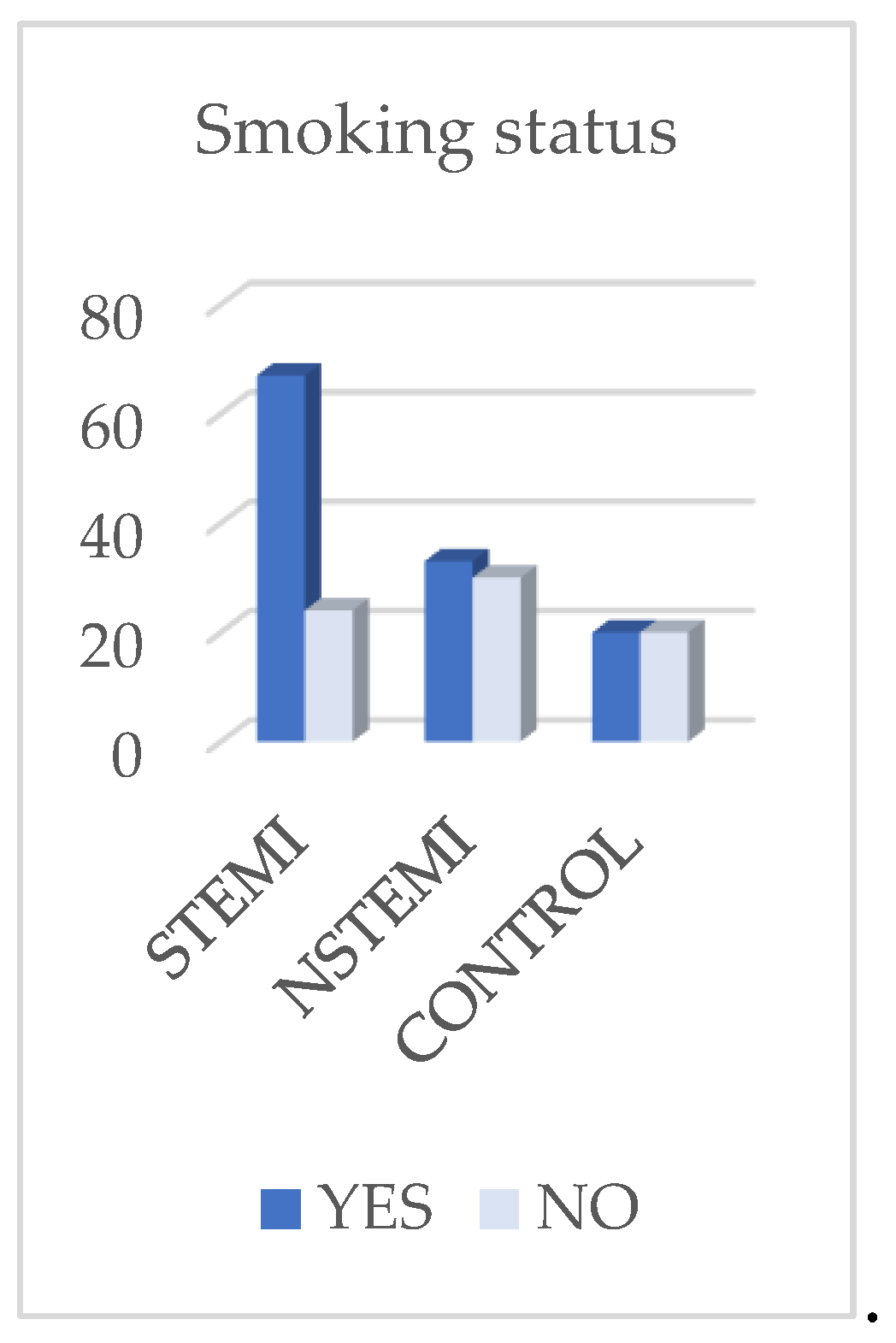

Smoking status |

Smoke | 67 (76,1%) | 33 (52,4%) | 20 (50,0 %) |

0,002 |

| Non-smoke | 21 (23,9 %) | 30 (47,6 %) | 20 (50,0 %) | ||

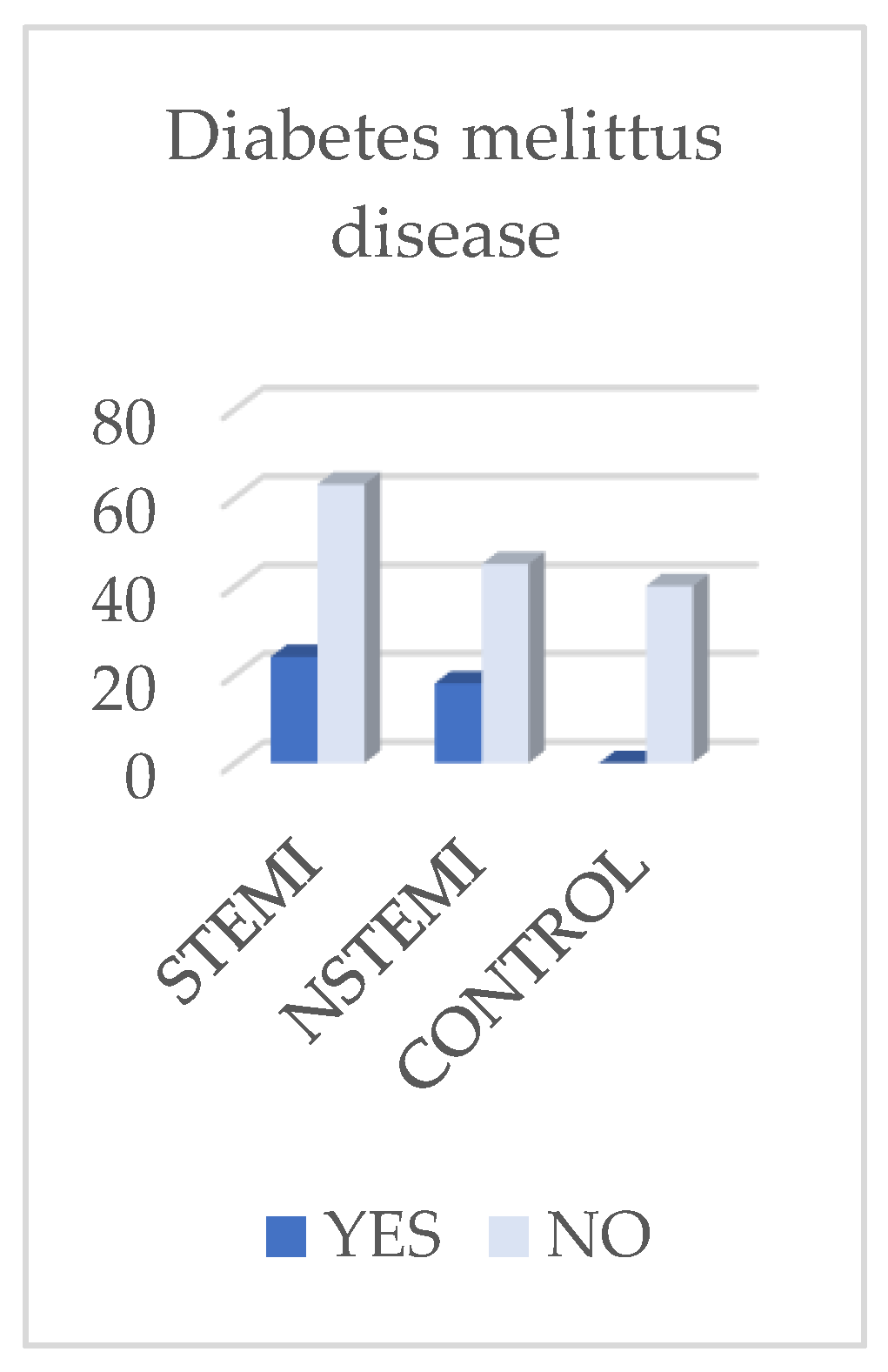

| Dibetes mellitus |

YES | 24 (27,3 %) | 18 (28,6 %) | 0 (0 %) |

< 0,001 |

| NO | 64 (72,7 %) | 45 (71,4 %) | 40 (100 %) | ||

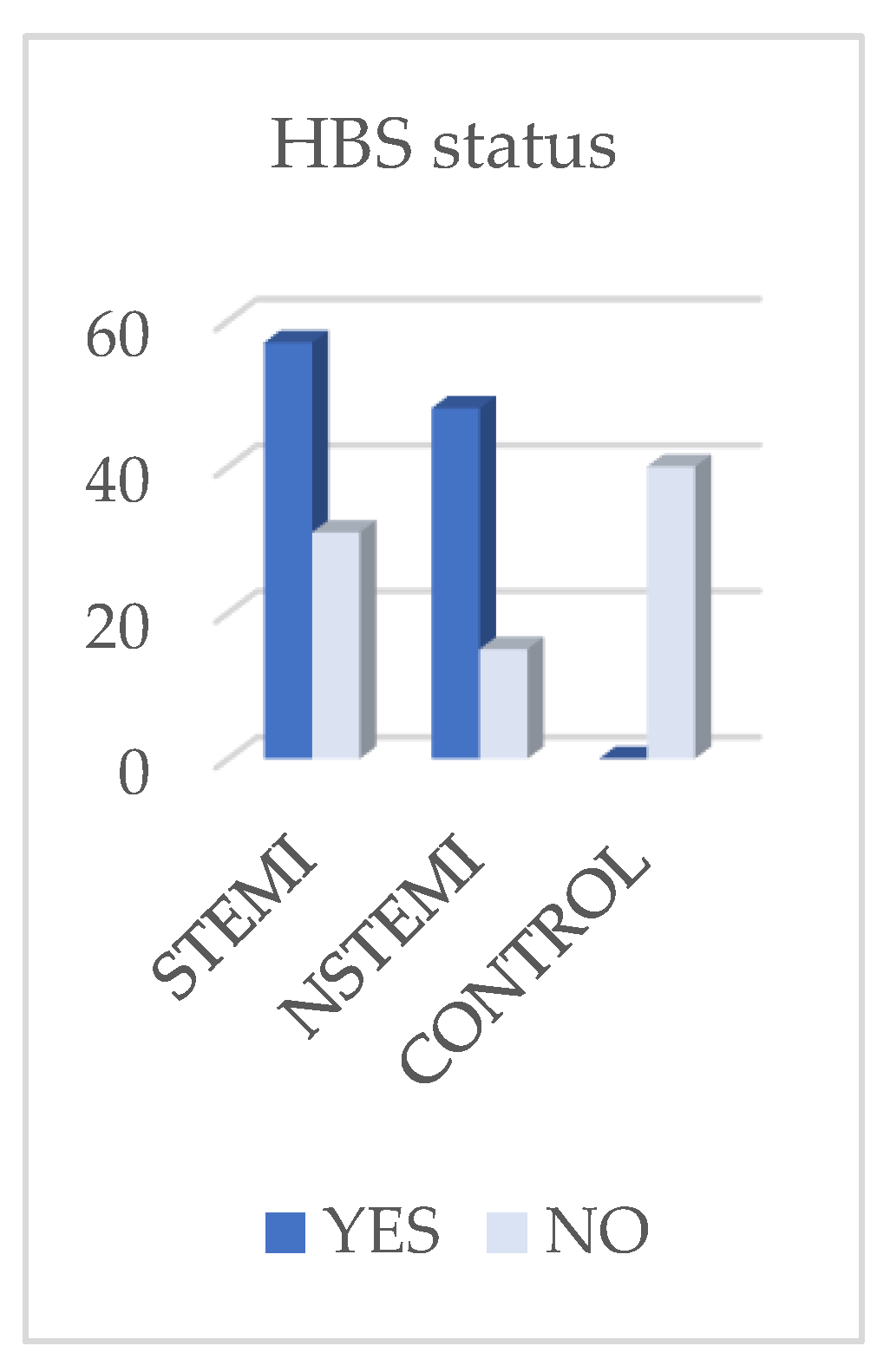

| HBP status | YES | 57 (64,8 %) | 48 (76,2 %) | 0 (0 %) |

< 0,001 |

| NO | 31 (35,2 %) | 15 (23,8 %) | 40 (100 %) | ||

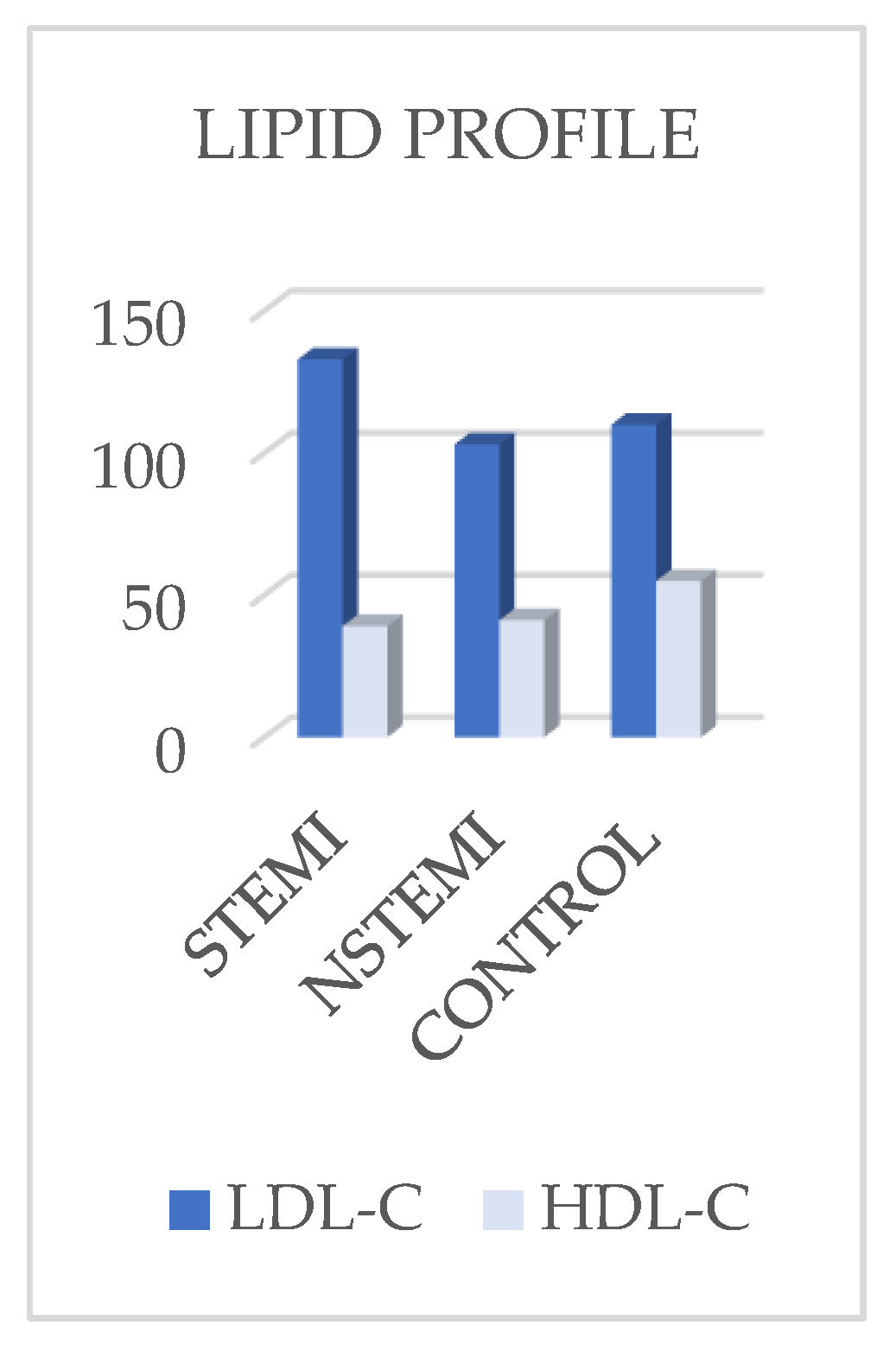

| LDL Cholesterol | 133 (100 – 168) | 103 (79,0 – 121) | 110 (90,0 – 123) | < 0,001 | |

|

HDL Cholesterol |

39,1 (32,1 – 44,8) | 41,2 (36,3 – 51,9) |

55,0 (46,4 – 60,0) | < 0,001 | |

|

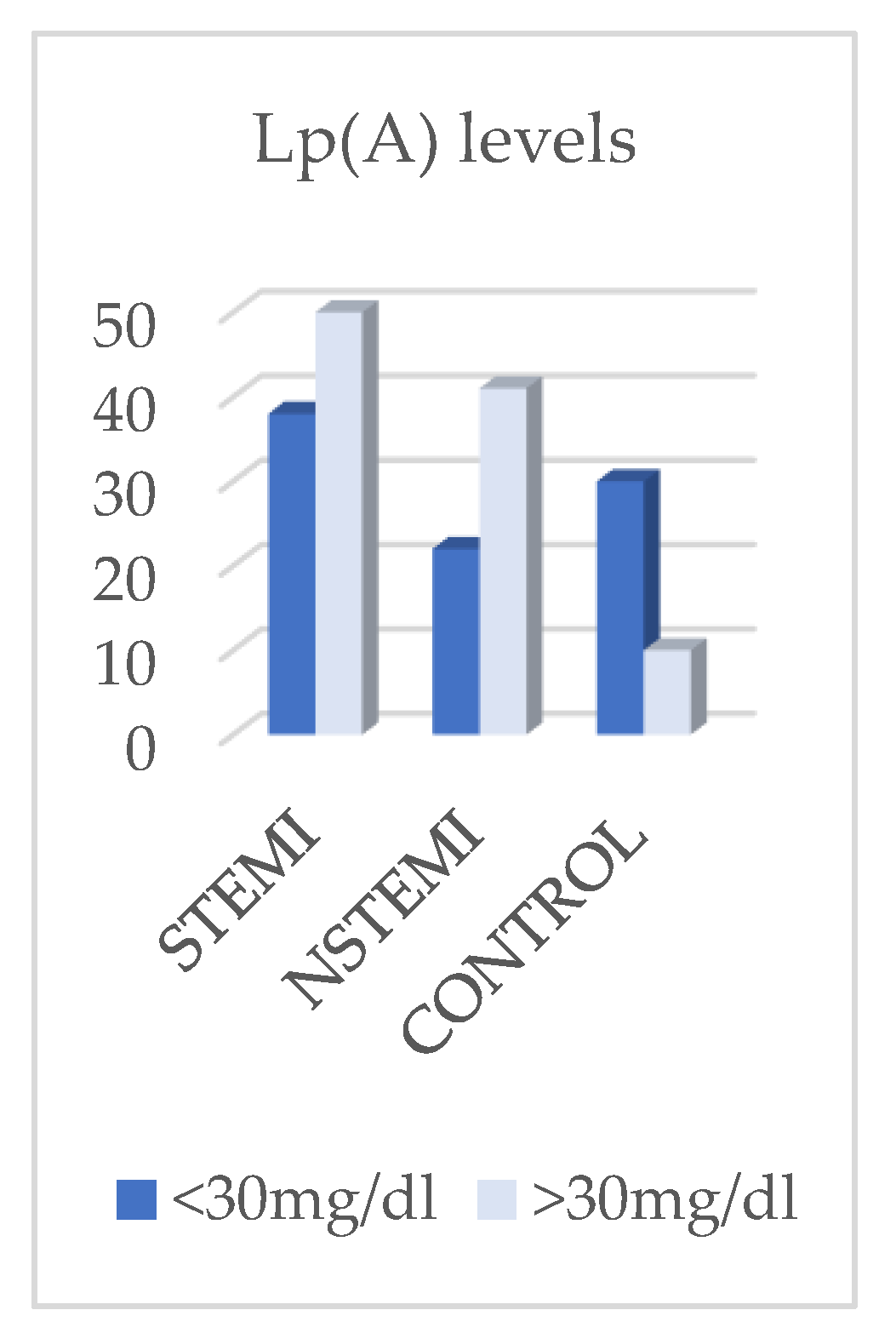

Lipoprotein (a) level |

Lp (a) ≤ 30 mg/dL |

38 (43,2 %) |

22 (34,9 %) |

30 (66,67 %) |

0,002 |

| Lp (a) > 30 mg/dL | 50 (56,8 %) |

41 (65,1 %) | 10 (33,33 %) | ||

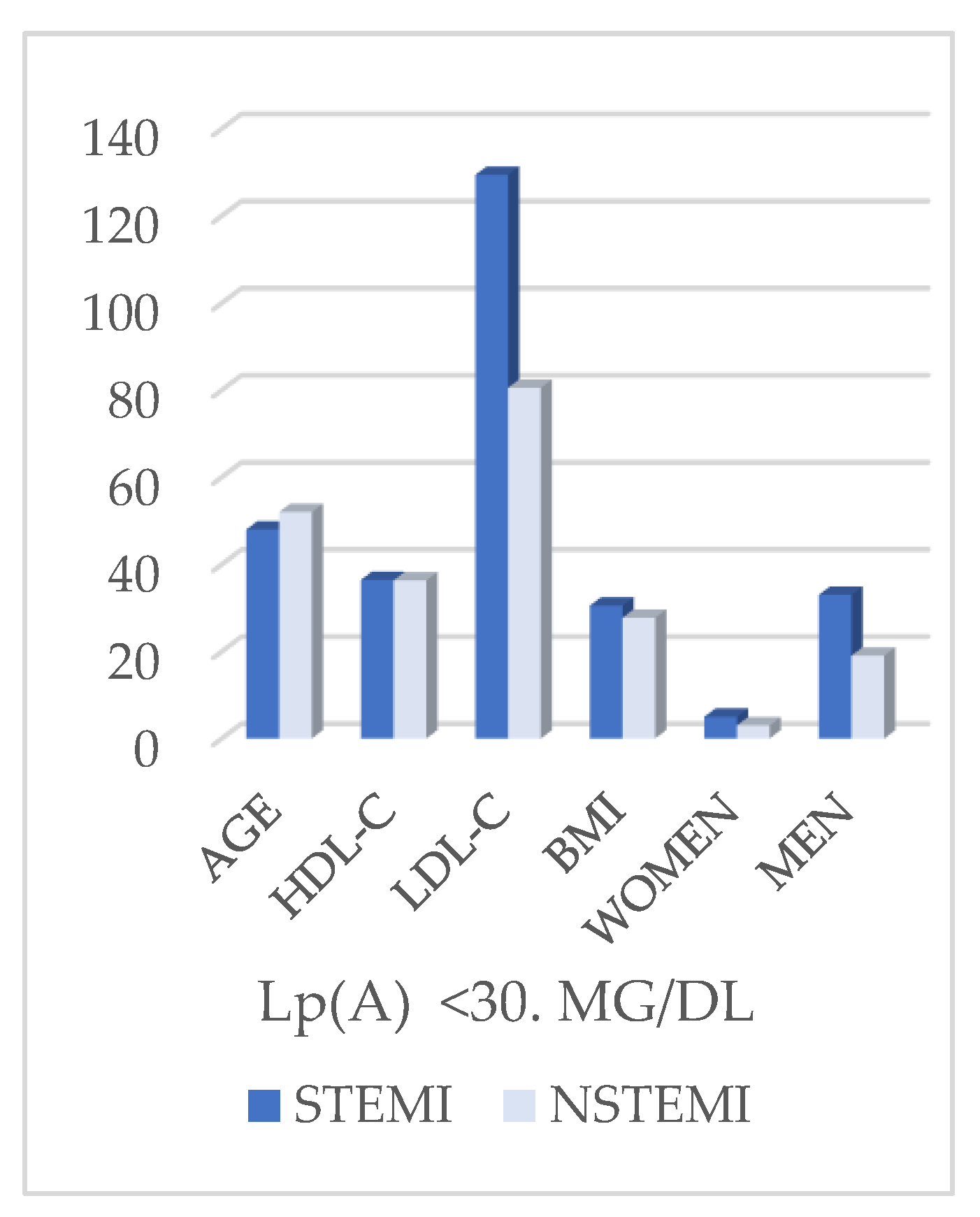

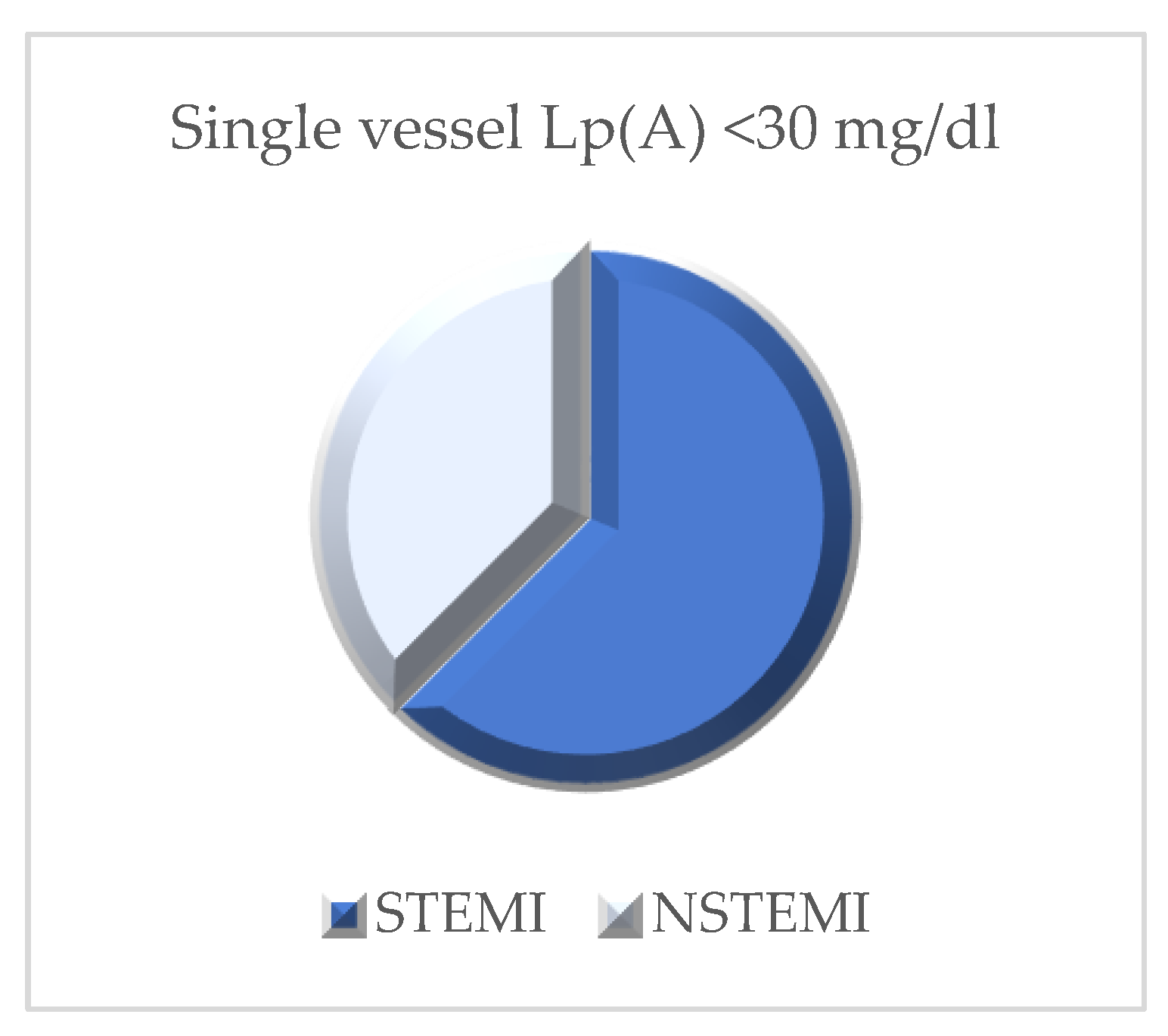

| Parameter | STEMI (n = 38) | NSTEMI (n = 22) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48,0 (43,0 – 54,0) | 52,0 (51,0 – 54,5) | 0,039 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 36,4 (31,7 – 44,5) | 36,3 (28,5 – 53,2) | 0,607 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 129,4 (89,2 – 157,0) | 80,5 (67,9 – 113,2) | < 0,001 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 30,5 (26,4 – 34,4) | 27,7 (26,4 – 28,6) | 0,021 |

| Men | 33 (86,8 %) | 19 (86,4 %) | 1,000 — |

| Women | 5 (13,2 %) | 3 (13,6 %) | |

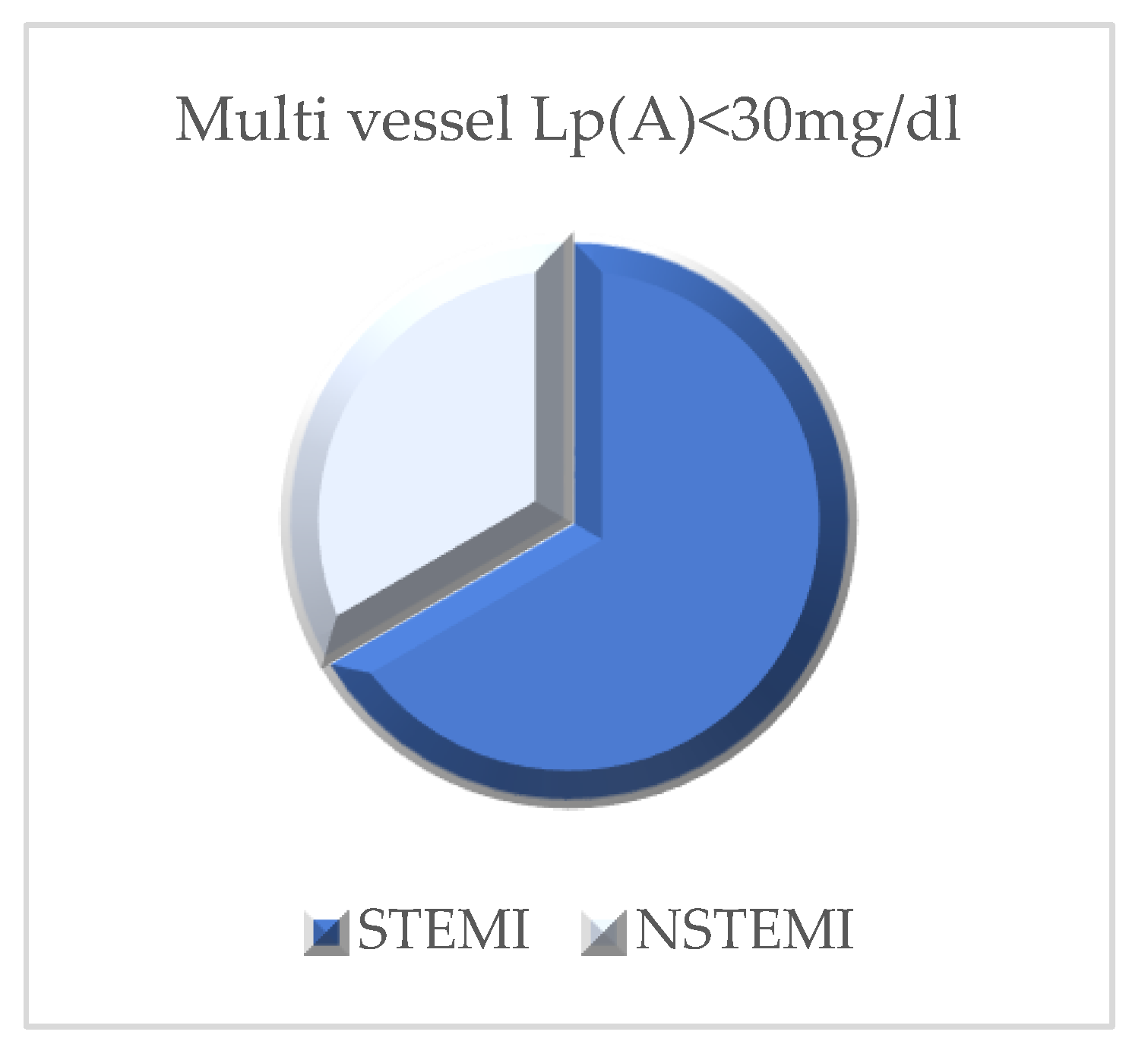

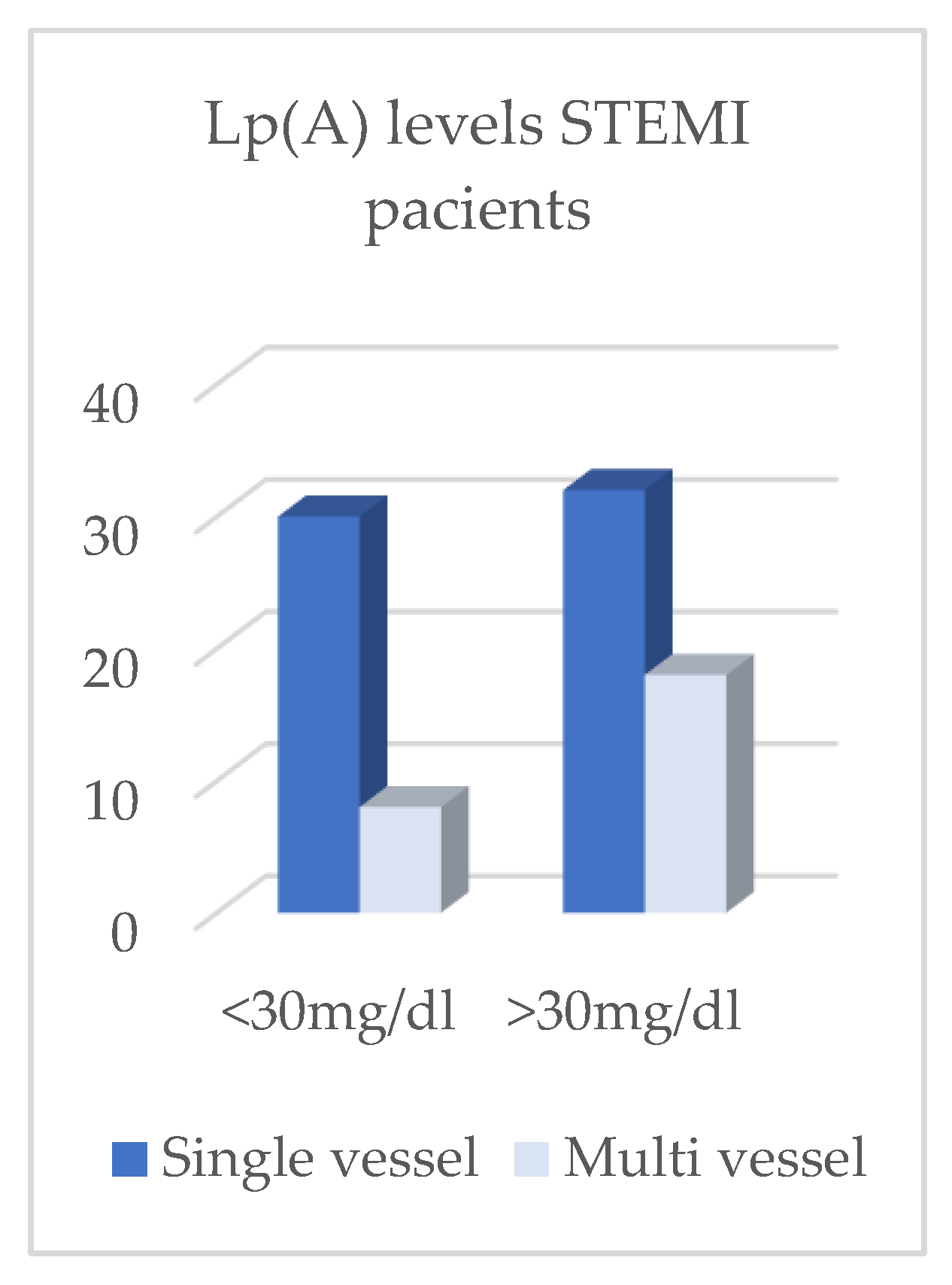

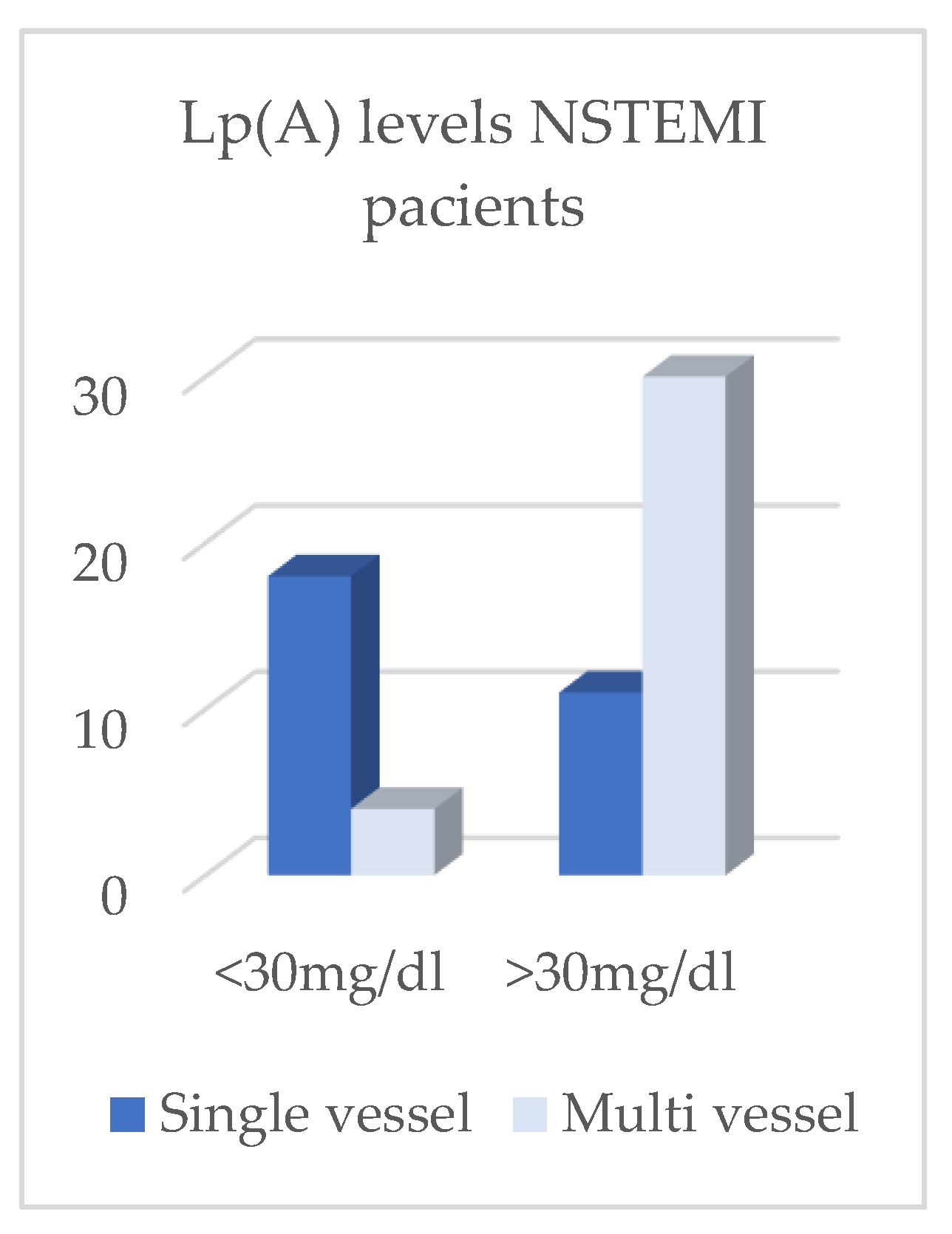

| Sigle-Vessel Disease | 30 (78,9 %) | 18 (81,8 %) | 1,000 |

| Multi-Vessel Disease | 8 (21,1 %) | 4 (18,2 %) |

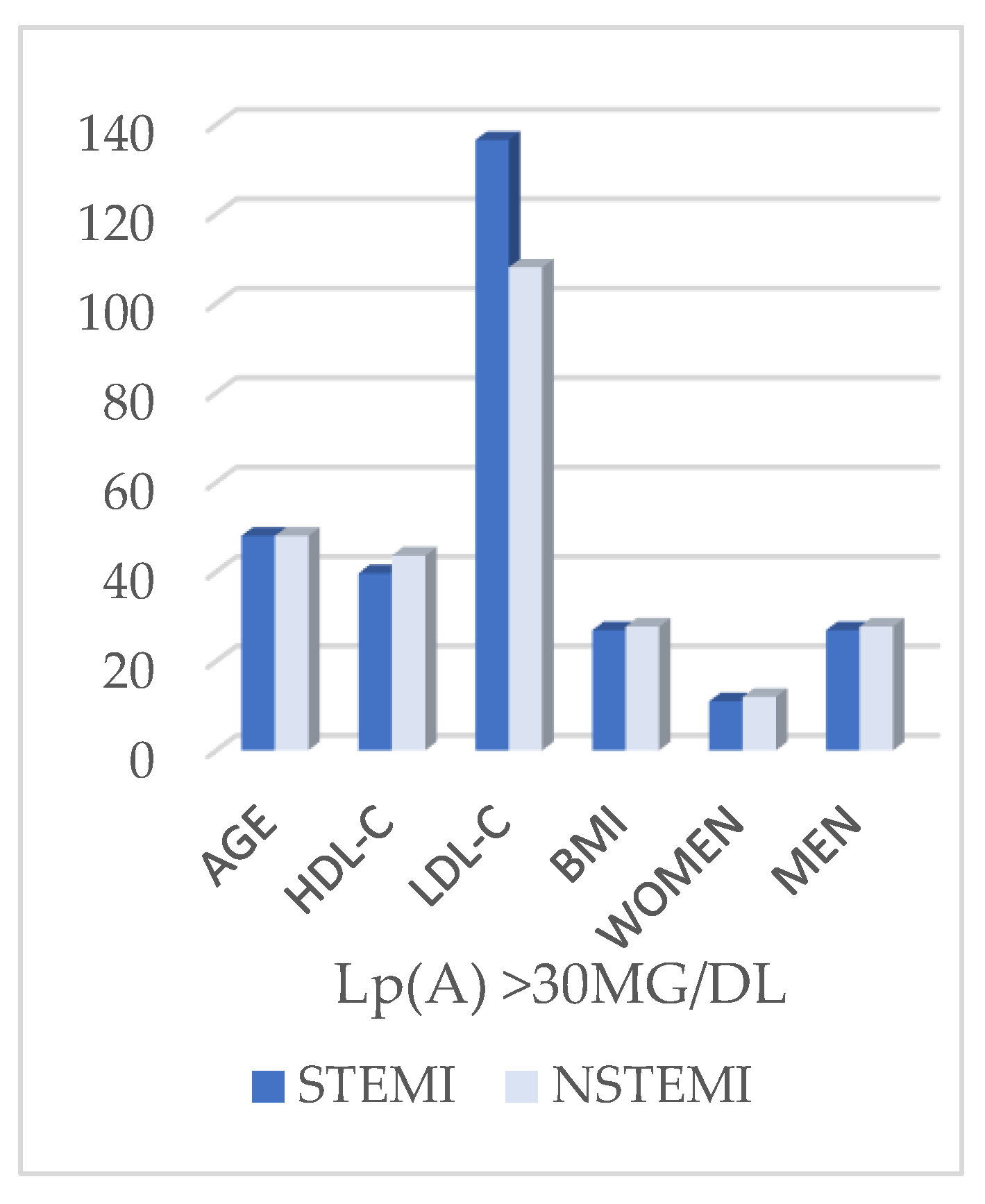

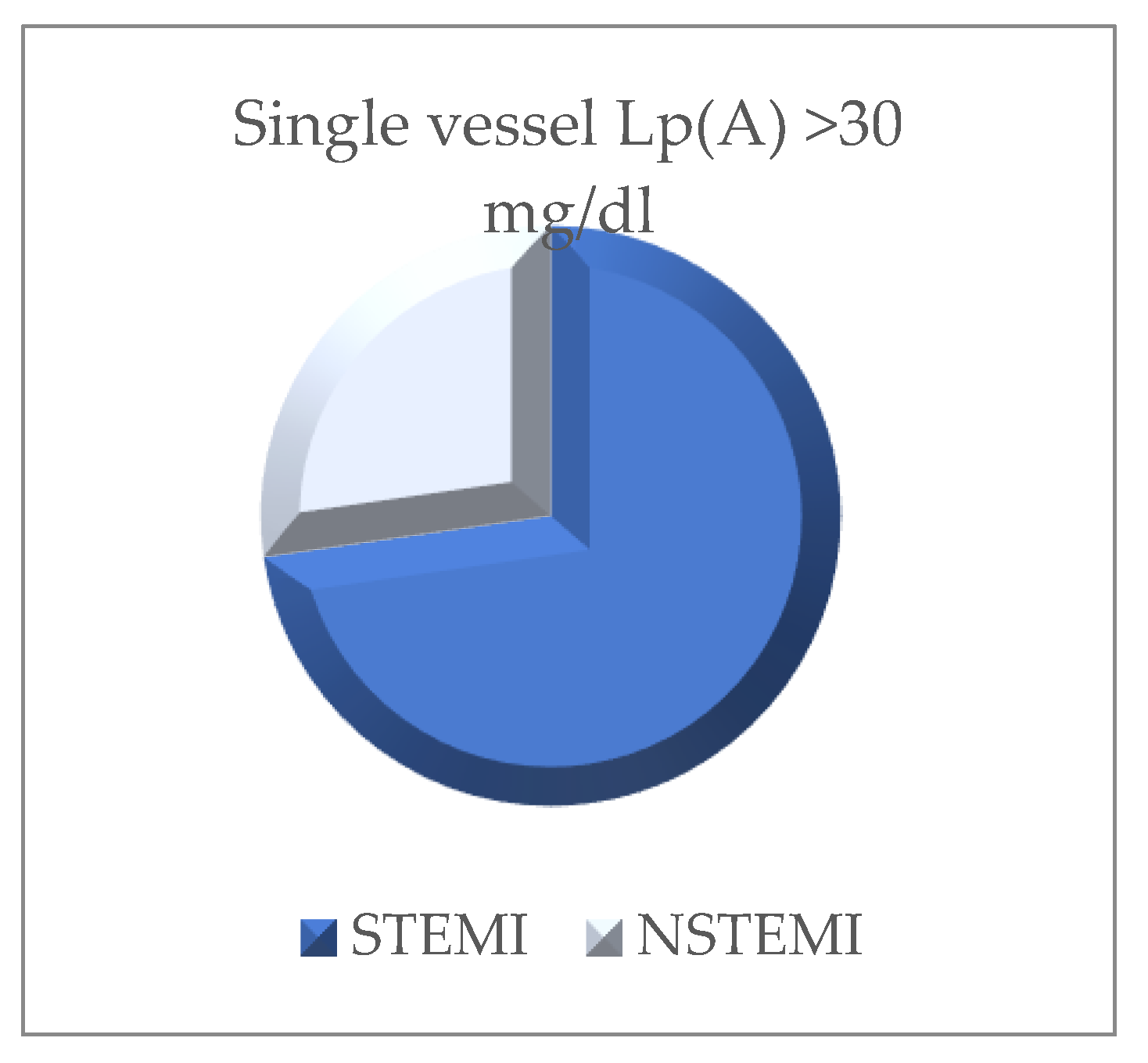

| Parameter | STEMI (n = 50) | NSTEMI (n = 41) | p-value ✧ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 48,0 (45,0 – 54,8) | 48,0 (43,0 – 50,0) | 0,251 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 39,6 (33,1 – 49,9) | 43,6 (38,8 – 44,9) | 0,089 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 137,5 (108,5 – 180,6) | 108,0 (93,0 – 145,0) | 0,004 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 26,9 (24,2 – 32,1) | 27,7 (24,9 – 29,4) | 0,808 |

| Men | 39 (78,0 %) | 29 (70,7 %) | 0,474 — |

| Women | 11 (22,0 %) | 12 (29,3 %) | |

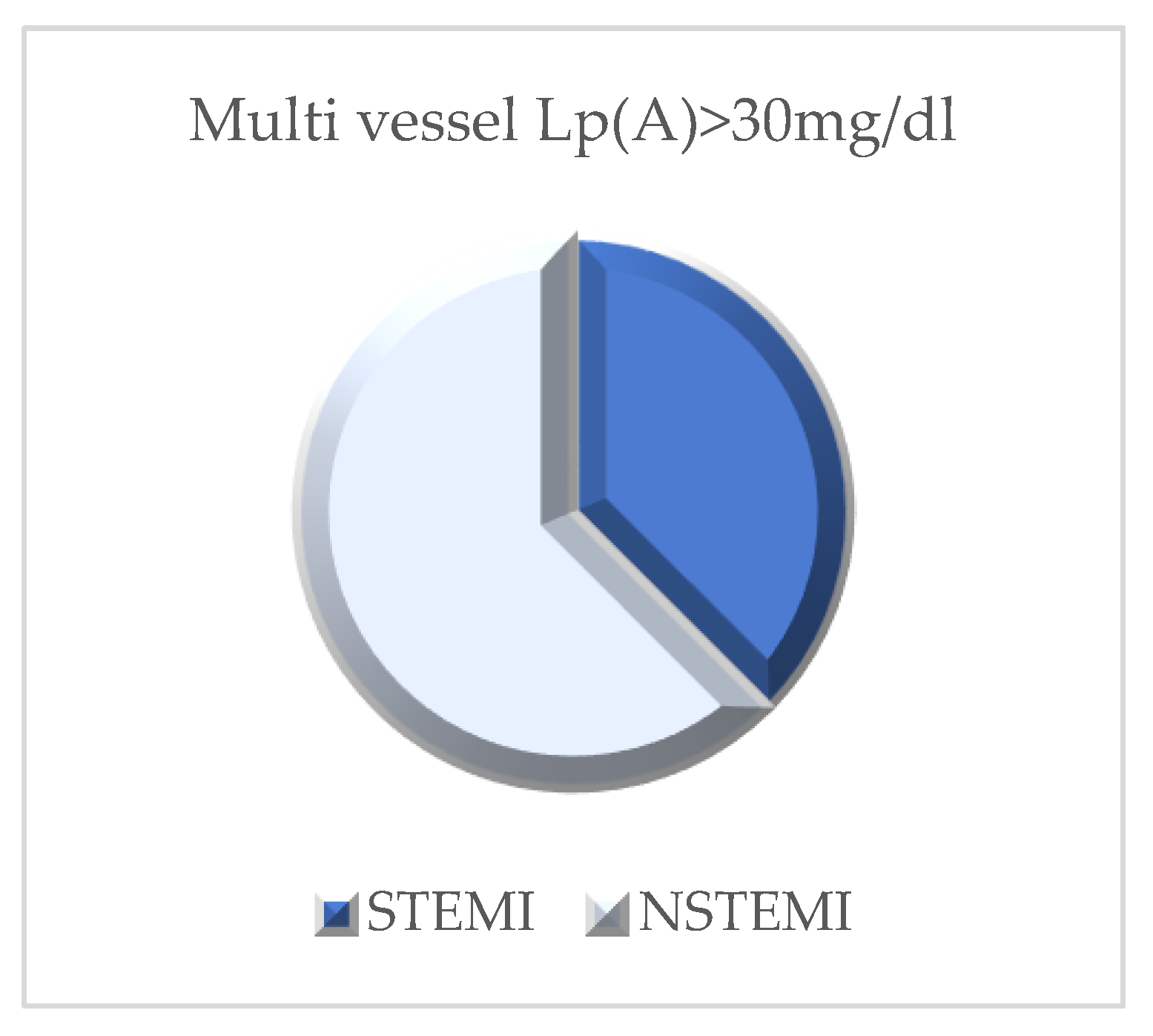

| Single-vassel disease | 32 (64,0 %) | 11 (26,8 %) | < 0,001 — |

| Multi-vessel disease | 18 (36,0 %) | 30 (73,2 %) |

| Predictor | RR | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lp(a) ≥30 mg/dl (vs <30) | 4.25 | 1.73–10.45 | 0.0016 |

| Gender (men vs women) | 1.54 | 0.88–2.68 | 0.130 |

| Diabetus mellitus (yes or no) | 1.29 | 0.81–2.05 | 0.285 |

| Age(+5 years) | 1.05 | 0.86–1.29 | 0.646 |

| LDL-C (+10 mg/dl) | 0.99 | 0.95–1.04 | 0.773 |

| IMC (+5 kg/m²) | 1.55 | 1.01–2.38 | 0.043 |

| Predictor | RR | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lp(a) ≥30 mg/dl (vs <30) | 1,78 | 1,10–2,90 | 0,020 |

| Gender (men vs women) | 1,37 | 0,73–2,56 | 0,329 |

| Diabetus mellitus (yes or no) | 1,71 | 1,07–2,74 | 0,026 |

| Age(+5 years) | 0,98 | 0,81–1,18 | 0,804 |

| LDL-C (+10 mg/dl) | 1,05 | 1,00–1,10 | 0,044 |

| IMC (+5 kg/m²) | 1,07 | 0,90–1,27 | 0,471 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).