Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Drug-Drug Interactions—Importance of Study in Pharmacology

Many-to-Many Associations: Issues and Solutions

Why Graph Attention Networks?

Literature Review

| Year | Title | Authors | Brief summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | Fine-Tuning BiomedBERT with LoRA and Pseudo-Labeling for Accurate Drug–Drug Interactions Classification | Gheorghita I-F; Bocanet V-I; Iantovics LB | Lightweight, polarity-aware DDI classifier (synergistic vs antagonistic) designed for efficient CDSS deployment with robust logging. |

| 2025 | GAINET: Enhancing drug–drug interaction predictions through graph neural networks and attention mechanisms | Das B; Dagdogen HA; Kaya MO; Akgul MS; Das R; et al. | Attention-enhanced GNN predicts DDIs with strong metrics (AUC ~0.95) and interpretable substructure highlights. |

| 2025 | Chat GPT vs. Clinical Decision Support Systems in the Analysis of Drug–Drug Interactions | Bischof T; al Jalali V; Zeitlinger M; Stemer G; Schoergenhofer C; et al. | In 30 polypharmacy cases, ChatGPT missed many clinically relevant pDDIs (esp. QTc risks) and was inconsistent vs established CDSSs. |

| 2025 | Towards Explainable Polypharmacy Risk Warnings Using Reinforcement Learning on Knowledge Graphs | Nguyen T-G-B; Le M-C; Nguyen V-K; Can D-C; Le H-Q; et al. | RL agent navigates a biomedical KG to predict DDIs with path-based explanations; promising ablations, needs clinical validation. |

| 2025 | MAVGAE: a multimodal framework for predicting asymmetric drug–drug interactions based on variational graph autoencoder | Deng Z; Xu J; Feng Y; Dong L; Zhang Y | Predicts asymmetric (order-dependent) DDIs by fusing heterogeneous data; shows high accuracy on large datasets. |

| 2025 | PolyLLM: polypharmacy side effect prediction via LLM-based SMILES encodings | Hakim S; Ngom A | Encodes drug SMILES with LLMs (e.g., ChemBERTa, GPT) and combines pair embeddings for side-effect prediction using MLP/GNN. ChemBERTa + GNN performs best. Demonstrates structure-only inputs can be highly effective when other entities (proteins, cell lines) aren’t available. |

| 2025 | Smart Pharmaceutical Monitoring System With Personalized Medication Schedules and Self-Management Programs for Patients With Diabetes (DUMS) | Xiao J; Li M; Cai R; …; Zhang J; Cheng S | Cloud-based system with 475 diabetes meds, 684 constraints, and 12,351 DDI rules generates personalized schedules and self-management plans. Expert ratings show DUMS > GPT-4 for accuracy/safety; pharmacist-refined outputs were best. Supports dosing times, education, diet, and lifestyle guidance. |

| 2024 | Autonomous Pharmaceutical Care with Large Language Models (Shennong-Agent) | Dou Y; Deng Z; Xing T; Xiao J; Peng S | Multi-agent LLM framework with multimodal inputs that segments and executes pharmacy-care tasks via reasoning, retrieval, and web tools. Expert evaluations indicate performance surpasses baseline LLMs; capabilities further improved with RLHF. Targets med safety issues like polypharmacy-related risks. |

| 2023 | Enhancing Primary Care for Nursing Home Patients with an AI-Aided Rational Drug Use Web Assistant | Yılmaz T; Ceyhan Ş; Akyön ŞH; Yılmaz TE | Evaluated nursing home regimens with a rational drug-use assistant: 89.9% had risky DDIs; 20.2% had contraindicated DDIs. The assistant reduced polypharmacy and projected a 9.1% monthly cost reduction; interaction detection time dropped from 2278 s to 33.8 s (~60× faster). |

| 2023 | Automated Detection of Patients at High Risk of Polypharmacy including Anticholinergic and Sedative Medications | Shirazibeheshti A; Ettefaghian A; Khanizadeh F; …; Radwan T; Luca C | On 300,000 records, computed weighted anticholinergic and DDI risk scores, then used mean-shift clustering to flag high-risk groups. Found scores are largely uncorrelated and outliers often high on only one metric—both should be considered to avoid misses. Integrated into a live management system. |

| 2023 | AI-supported web application for reducing polypharmacy side effects and supporting rational drug use in geriatric patients | Akyon SH; Akyon FC; Yılmaz TE | Built a comprehensive tool covering 430 common geriatric drugs, integrating six PIM criteria plus drug–drug and drug–disease interactions. Achieved 75.3% PIM coverage and cut detection time from 2278 s to 33.8 s (~60×). Publicly available (fastrational.com) to support rational prescribing. |

| 2023 | A novel drug–drug interactions prediction method based on a graph attention network (HAG-DDI) | Tan X; Fan S; Duan K; …; Sun P; Ma Z | Treats interactions as nodes and connects them if they share a drug; trains on small subnetworks with semantic-level attention to capture mechanism differences. Achieves F1 = 0.952 and mitigates data sparsity/bias for new drugs. Code released for reproducibility. |

| 2022 | Minimization of the Drug and Gene Interactions in Polypharmacy Therapies Augmented with COVID-19 Medications | Lagumdzija-Kulenovic A; Kulenovic A | Uses PM-TOM to optimize polypharmacy regimens when adding dexamethasone, remdesivir, or colchicine. On Harvard PGP EMR + DrugBank/CTD, adding these drugs markedly increases drug/gene interactions in partially optimized regimens, but far less in fully optimized ones. Recommends rigorous optimization before adding high-interaction COVID meds. |

| 2021 | Implementation of pharmacogenomics and artificial intelligence tools for chronic disease management in primary care setting | Silva P; Jacobs D; Kriak J; …; Neal G; Ramos K | Describes a primary care platform combining weak clinical signals with PGx (~90 SNPs + CYP2D6 CNV) and PK to monitor drug–gene and drug–drug interactions. Validated via a virtual patient case; proposes a regional outcomes registry. Demonstrates feasibility of PGx-informed, proactive medication management CDS. |

Methods

Notation and setup

Augmentations

- (i)

- random channel dropout/masking,

- (ii)

- noise/perturbation in latent space, and

- (iii)

- paired-latent interpolation (PLI), an interaction-preserving interpolation between two augmented views of the same pair’s latent representations.

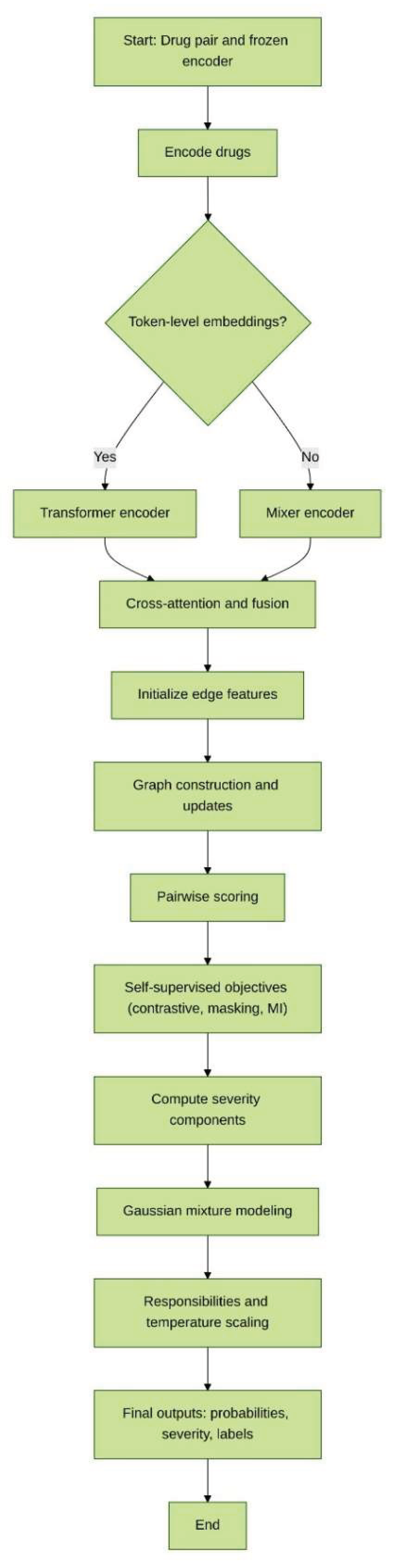

Steps

Discussion

Conclusion

References

- Sun, X.; Li, X. Editorial: Aging and Chronic Disease: Public Health Challenge and Education Reform. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1175898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, K.S.; Mody, R.; Lage, M.J.; Douglas, S.; Patel, H. Chronic Medication Burden and Complexity for US Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Treated with Glucose-Lowering Agents. Diabetes Ther. 2020, 11, 1513–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, J.E.; Moriarty, F.; Bennett, K.E.; Cahir, C. Drug–Drug Interactions and the Risk of Adverse Drug Reaction-Related Hospital Admissions in the Older Population. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Xie, F. Evaluation of Pharmacokinetic Drug-Drug Interactions: A Review of the Mechanisms, In Vitro and In Silico Approaches. Metabolites 2021, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.K.; Critchlow, C.W.; Dreyer, N.; Lash, T.L.; Reynolds, R.F.; Sørensen, H.T.; Lange, J.L.; Gatto, N.M.; Sobel, R.E.; Lai, E.C.; Schoonen, M.; Brown, J.S.; Christian, J.B.; Brookhart, M.A.; Bradbury, B.D. Advancing Principled Pharmacoepidemiologic Research to Support Regulatory and Healthcare Decision Making: The Era of Real-World Evidence. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 117, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, D.; Ishida, C.; Patel, P.; et al. Polypharmacy. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532953/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Alhumaidi, R.M.; Bamagous, G.A.; Alsanosi, S.M.; Alqashqari, H.S.; Qadhi, R.S.; Alhindi, Y.Z.; Ayoub, N.; Falemban, A.H. Risk of Polypharmacy and Its Outcome in Terms of Drug Interaction in an Elderly Population: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammar, T.; Hamqvist, S.; Zetterholm, M.; Jokela, P.; Ferati, M. Current Knowledge about Providing Drug-Drug Interaction Services for Patients—A Scoping Review. Pharm. 2021, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, R.R.; Khan, A. Assessing the Practicality of Designing a Comprehensive Intelligent Conversation Agent to Assist in Dementia Care. In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies—HEALTHINF, Rome, Italy, 18–20 February 2025; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2025; pp. 655–663, ISBN 978-989-758-731-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Straubinger, R.M.; Mager, D.E. Pharmacodynamic Drug-Drug Interactions. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 105, 1395–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palleria, C.; Di Paolo, A.; Giofrè, C.; Caglioti, C.; Leuzzi, G.; Siniscalchi, A.; De Sarro, G.; Gallelli, L. Pharmacokinetic Drug-Drug Interaction and Their Implication in Clinical Management. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.H. Interpretation of Drug Interaction Using Systemic and Local Tissue Exposure Changes. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Mi, K.; Hou, Y.; Hui, T.; Zhang, L.; Tao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, L. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Drug-Drug Interactions: Research Methods and Applications. Metabolites 2023, 13, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.; Brewer, L.; Williams, D. Drug Interactions. Med. 2016, 44, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deodhar, M.; Al Rihani, S.B.; Arwood, M.J.; Darakjian, L.; Dow, P.; Turgeon, J.; Michaud, V. Mechanisms of CYP450 Inhibition: Understanding Drug-Drug Interactions Due to Mechanism-Based Inhibition in Clinical Practice. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radu, A.-F.; Radu, A.; Tit, D.M.; Bungau, G.; Negru, P.A. Mapping the Global Research on Drug–Drug Interactions: A Multidecadal Evolution Through AI-Driven Terminology Standardization. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prueksaritanont, T.; Chu, X.; Gibson, C.; Cui, D.; Yee, K.L.; Ballard, J.; Cabalu, T.; Hochman, J. Drug-Drug Interaction Studies: Regulatory Guidance and an Industry Perspective. AAPS J. 2013, 15, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraynov, E.; Martin, S.W.; Hurst, S.; Fahmi, O.A.; Dowty, M.; Cronenberger, C.; Loi, C.M.; Kuang, B.; Fields, O.; Fountain, S.; Awwad, M.; Wang, D. How Current Understanding of Clearance Mechanisms and Pharmacodynamics of Therapeutic Proteins Can Be Applied for Evaluation of Their Drug-Drug Interaction Potential. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011, 39, 1779–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, J.E.; Yu, J.; Ragueneau-Majlessi, I.; Isoherranen, N. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling and Simulation Approaches: A Systematic Review of Published Models, Applications, and Model Verification. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 1823–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillinger, L.; Walter, S.; Ley, M.; Kęska-Izworska, K.; Ghasemi Dehkordi, L.; Kratochwill, K.; Perco, P. Computational Modeling Approaches and Regulatory Pathways for Drug Combinations. Drug Discov. Today 2025, 30, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Payra, S.; Singh, S.K. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Pharmacological Research: Bridging the Gap Between Data and Drug Discovery. Cureus 2023, 15, e44359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Many-to-Many Relationships. Microsoft Learn. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/ef/core/modeling/relationships/many-to-many (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Zantvoort, K.; Hentati Isacsson, N.; Funk, B.; Kaldo, V. Dataset Size versus Homogeneity: A Machine Learning Study on Pooling Intervention Data in E-Mental Health Dropout Predictions. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241248920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D.; Deserno, M.K.; Rhemtulla, M.; Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I.; McNally, R.J.; Robinaugh, D.J.; Perugini, M.; Dalege, J.; Costantini, G.; Isvoranu, A.-M.; Wysocki, A.C.; van Borkulo, C.D.; van Bork, R.; Waldorp, L.J. Network Analysis of Multivariate Data in Psychological Science. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, K.; DeCost, B.; Chen, C.; et al. Recent Advances and Applications of Deep Learning Methods in Materials Science. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osl, M.; Dreiseitl, S.; Kim, J.; Patel, K.; Baumgartner, C.; Ohno-Machado, L. Effect of Data Combination on Predictive Modeling: A Study Using Gene Expression Data. In Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium; 2010; pp. 567–571. [Google Scholar]

- Bailly, A.; Blanc, C.; Francis, É.; Guillotin, T.; Jamal, F.; Wakim, B.; Roy, P. Effects of Dataset Size and Interactions on the Prediction Performance of Logistic Regression and Deep Learning Models. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 213, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Torras, A.; Duran-Frigola, M.; Bertoni, M.; Locatelli, M.; Aloy, P. Integrating and Formatting Biomedical Data as Pre-Calculated Knowledge Graph Embeddings in the Bioteque. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Hwang, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, H.; Peng, W.-C.; Chen, T.-F.; Wang, W. Time-IMM: A Dataset and Benchmark for Irregular Multimodal Multivariate Time Series. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamabo, A.K.; Yu, H.; Liu, Z.; Shi, J.-Y. Drug–Drug Interaction Prediction with Learnable Size-Adaptive Molecular Substructures. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.Y.; Song, J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.; Kim, I.-W.; Moon, B.; Oh, J.M. Machine Learning-Based Quantitative Prediction of Drug Exposure in Drug-Drug Interactions Using Drug Label Information. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinou, C.; Ellinas, G.; Panayiotou, C.; Polycarpou, M. Shortest Path Routing in Transportation Networks with Time-Dependent Road Speeds. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Computational Logistics; 2016; pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albattah, W.; Khan, R.U. Impact of Imbalanced Features on Large Datasets. Front. Big Data 2025, 8, 1455442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabasova, E.; Reid, J.; Wernisch, L. Clusternomics: Integrative Context-Dependent Clustering for Heterogeneous Datasets. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.X.; Rush, A.M. Contextual Document Embeddings. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Ain, Q.T.; Liu, Y.; Liang, B.; Qiang, X.; Kou, Z. GTAT: Empowering Graph Neural Networks with Cross Attention. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, C.; He, Y.; Peng, J.; Fu, D.; Tan, T.-P. ESNERA: Empirical and Semantic Named Entity Alignment for Named Entity Dataset Merging. arXiv 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zeighami, S.; Seshadri, R.; Shahabi, C. A Neural Database for Answering Aggregate Queries on Incomplete Relational Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 2790–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Lu, D.; Kan, M.-Y.; Cui, P. Understanding and Classifying Image Tweets. In Proceedings of the 2013 ACM Multimedia Conference, Barcelona, Spain; 2013; pp. 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, B. Combinatorial Tasks as Model Systems of Deep Learning. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 2024. Available online: https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37379085.

- Mahler, B.I. Contagion Dynamics for Manifold Learning. Front. Big Data 2022, 5, 668356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerritse, E.J.; Hasibi, F.; de Vries, A.P. Graph-Embedding Empowered Entity Retrieval. arXiv 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huo, H.; Hou, Z.; Bu, L.; Mao, J.; Wang, Y.; Lv, X.; Bu, F. Co-Embedding of Edges and Nodes with Deep Graph Convolutional Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, A. A Hybrid Attention Mechanism for Multi-Target Entity Relation Extraction Using Graph Neural Networks. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2023, 11, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrahatis, A.G.; Lazaros, K.; Kotsiantis, S. Graph Attention Networks: A Comprehensive Review of Methods and Applications. Future Internet 2024, 16, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Lakizadeh, A. GADNN: A Graph Attention-Based Method for Drug-Drug Association Prediction Considering the Contribution Rate of Different Types of Drug-Related Features. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2024, 44, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Valle, J.; Correia, R.B.; Camacho-Artacho, M.; Lepore, R.; Mattos, M.M.; Rocha, L.M.; Valencia, A. Prevalence and Differences in the Co-Administration of Drugs Known to Interact: An Analysis of Three Distinct and Large Populations. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zou, Q.; Niu, M.; Ding, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, Y. DrugDAGT: A Dual-Attention Graph Transformer with Contrastive Learning Improves Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction. BMC Biol. 2024, 22, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.; Assiri, A. A Rule-Based Inference Framework to Explore and Explain the Biological Related Mechanisms of Potential Drug-Drug Interactions. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 9093262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghita, I.-F.; Bocanet, V.-I.; Iantovics, L.B. Fine-Tuning BiomedBERT with LoRA and Pseudo-Labeling for Accurate Drug–Drug Interactions Classification. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Bisong, E.; Bhatt, S.; Wagner, T.; Elliott, R.; Mosconi, F. BioMedBERT: A Pre-Trained Biomedical Language Model for QA and IR. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Barcelona, Spain (Online), 2020; pp. 669–679. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, S.; Ngom, A. PolyLLM: Polypharmacy Side Effect Prediction via LLM-Based SMILES Encodings. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1617142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithrananda, S.; Grand, G.; Ramsundar, B. ChemBERTa: Large-Scale Self-Supervised Pretraining for Molecular Property Prediction. arXiv 2020. [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Dagdogen, H.A.; Kaya, M.O.; Tuncel, O.; Akgul, M.S.; Das, R. GAINET: Enhancing Drug–Drug Interaction Predictions through Graph Neural Networks and Attention Mechanisms. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2025, 259, 105337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Xu, J.; Feng, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Y. MAVGAE: A Multimodal Framework for Predicting Asymmetric Drug-Drug Interactions Based on Variational Graph Autoencoder. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2025, 28, 1098–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Fan, S.; Duan, K.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Sun, P.; Ma, Z. A Novel Drug-Drug Interactions Prediction Method Based on a Graph Attention Network. Electron. Res. Arch. 2023, 31, 5632–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.G.B.; Le, M.-C.; Nguyen, V.-K.; Nguyen, H.-S.; Nguyen, C.-V.T.; Le, D.-T.; Can, D.-C.; Le, H.-Q. Towards Explainable Polypharmacy Risk Warnings Using Reinforcement Learning on Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Development of Biomedical Engineering in Vietnam, BME 2024; Vo, V.T., Nguyen, T.H., Vong, B.L., Pham, T.T.H., Doan, N.H., Eds. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 122, pp. 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Deng, Z.; Xing, T.; Xiao, J.; Peng, S. Autonomous Pharmaceutical Care with Large Language Models. Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, T.; Al Jalali, V.; Zeitlinger, M.; Jorda, A.; Hana, M.; Singeorzan, K.N.; Riesenhuber, N.; Stemer, G.; Schoergenhofer, C. Chat GPT vs. Clinical Decision Support Systems in the Analysis of Drug-Drug Interactions. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 117, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, M.; Cai, R.; Huang, H.; Yu, H.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Yu, T.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, S. Smart Pharmaceutical Monitoring System with Personalized Medication Schedules and Self-Management Programs for Patients with Diabetes: Development and Evaluation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e56737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, T.; Ceyhan, Ş.; Akyön, Ş.H.; Yılmaz, T.E. Enhancing Primary Care for Nursing Home Patients with an Artificial Intelligence-Aided Rational Drug Use Web Assistant. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyon, Ş.H.; Akyon, F.C.; Yılmaz, T.E. Artificial Intelligence-Supported Web Application Design and Development for Reducing Polypharmacy Side Effects and Supporting Rational Drug Use in Geriatric Patients. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1029198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazibeheshti, A.; Ettefaghian, A.; Khanizadeh, F.; Wilson, G.; Radwan, T.; Luca, C. Automated Detection of Patients at High Risk of Polypharmacy Including Anticholinergic and Sedative Medications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagumdzija-Kulenovic, A.; Kulenovic, A. Minimization of the Drug and Gene Interactions in Polypharmacy Therapies Augmented with COVID-19 Medications. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2022, 289, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Jacobs, D.; Kriak, J.; Abu-Baker, A.; Udeani, G.; Neal, G.; Ramos, K. Implementation of Pharmacogenomics and Artificial Intelligence Tools for Chronic Disease Management in Primary Care Setting. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusak, E.; Reizinger, P.; Juhos, A.; Bringmann, O.; Zimmermann, R.S.; Brendel, W. InfoNCE: Identifying the Gap Between Theory and Practice. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Huang, W.; Luo, M.; Zheng, Q.; Rong, Y.; Xu, T.; Huang, J. Graph Representation Learning via Graphical Mutual Information Maximization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.01169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, R.; Vats, A.; Vats, A.; Majumder, A. A Comprehensive Review on Harnessing Large Language Models to Overcome Recommender System Challenges. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.21117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.R.; Khan, A. Modernizing Medicine Through a Proof of Concept that Studies the Intersection of Robotic Exoskeletons, Computational Capacities and Dementia Care. In Health Informatics and Medical Systems and Biomedical Engineering, CSCE 2024, Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol. 2259; Alsadoon, A., Shenavarmasouleh, F., Amirian, S., Ghareh Mohammadi, F., Arabnia, H.R., Deligiannidis, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.R.; Khan, A. Machine Learning-Based Clinical Decision Support Systems in Dementia Care. In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies—HEALTHINF.; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2025; pp. 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | One-to-One Mapping | Many-to-Many Mapping |

|---|---|---|

| Fusion Complexity | Low | High |

| Need for Aggregation | No | Yes |

| Suitable Methods | Pairwise concatenation /attention | Attention over neighbors, graph embeddings |

| Ambiguity | None | Present (multiple matches per entity) |

| Loss | Niche (Where it fits) | Function (What it enforces) |

|---|---|---|

| Contrastive loss | Applied to drug pair embeddings after encoding and fusion. | Encourages consistent representations of positive (true) pairs while pushing apart negatives. |

| Masked prediction loss | Applied to hidden node/edge attributes within the graph. | Trains the model to reconstruct masked features, improving robustness and capturing local detail. |

| Mutual information loss | Applied between local pair representations and global graph summary. | Maximizes shared information, ensuring that pair embeddings remain aligned with global context. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).