Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Entropy Functions

3.1. Entropy Functions and Image Thresholding

4. Proposed Method

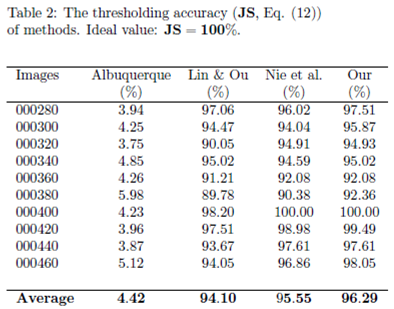

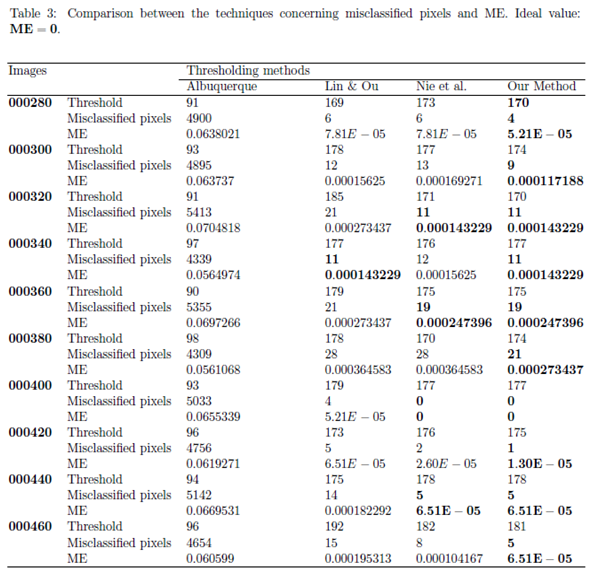

5. Experimental Results

-

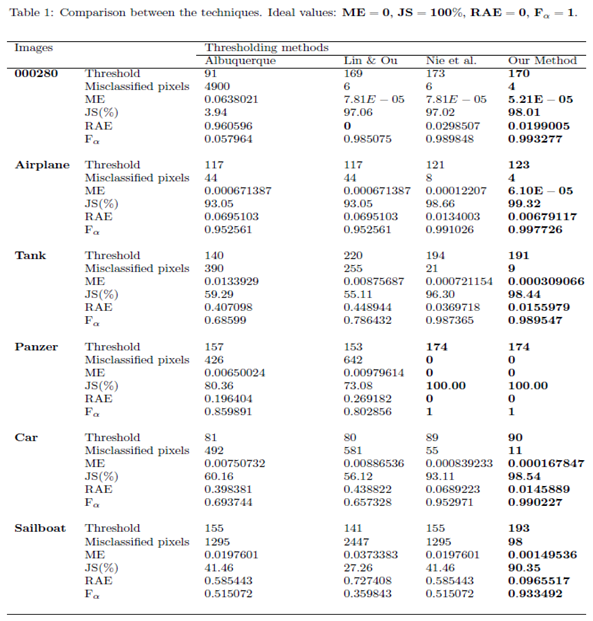

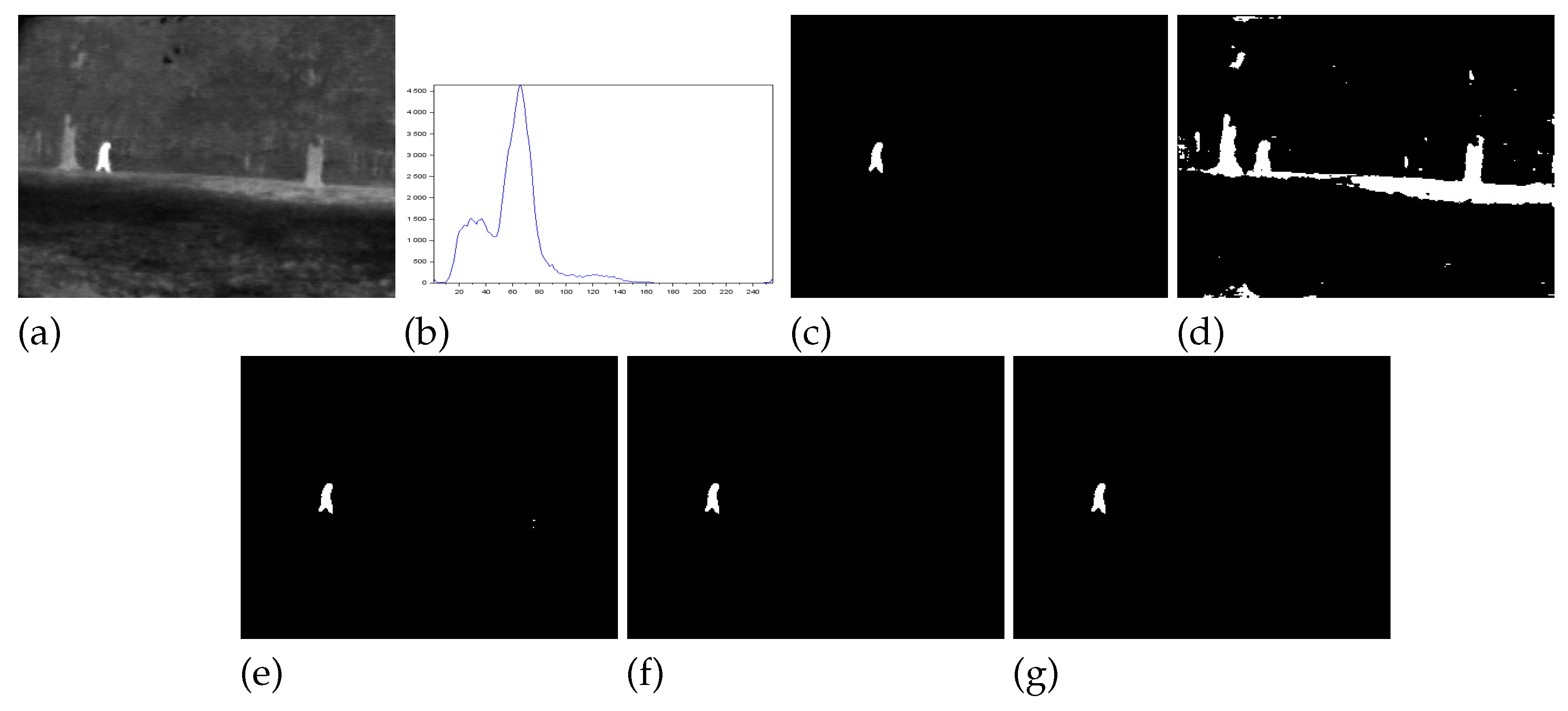

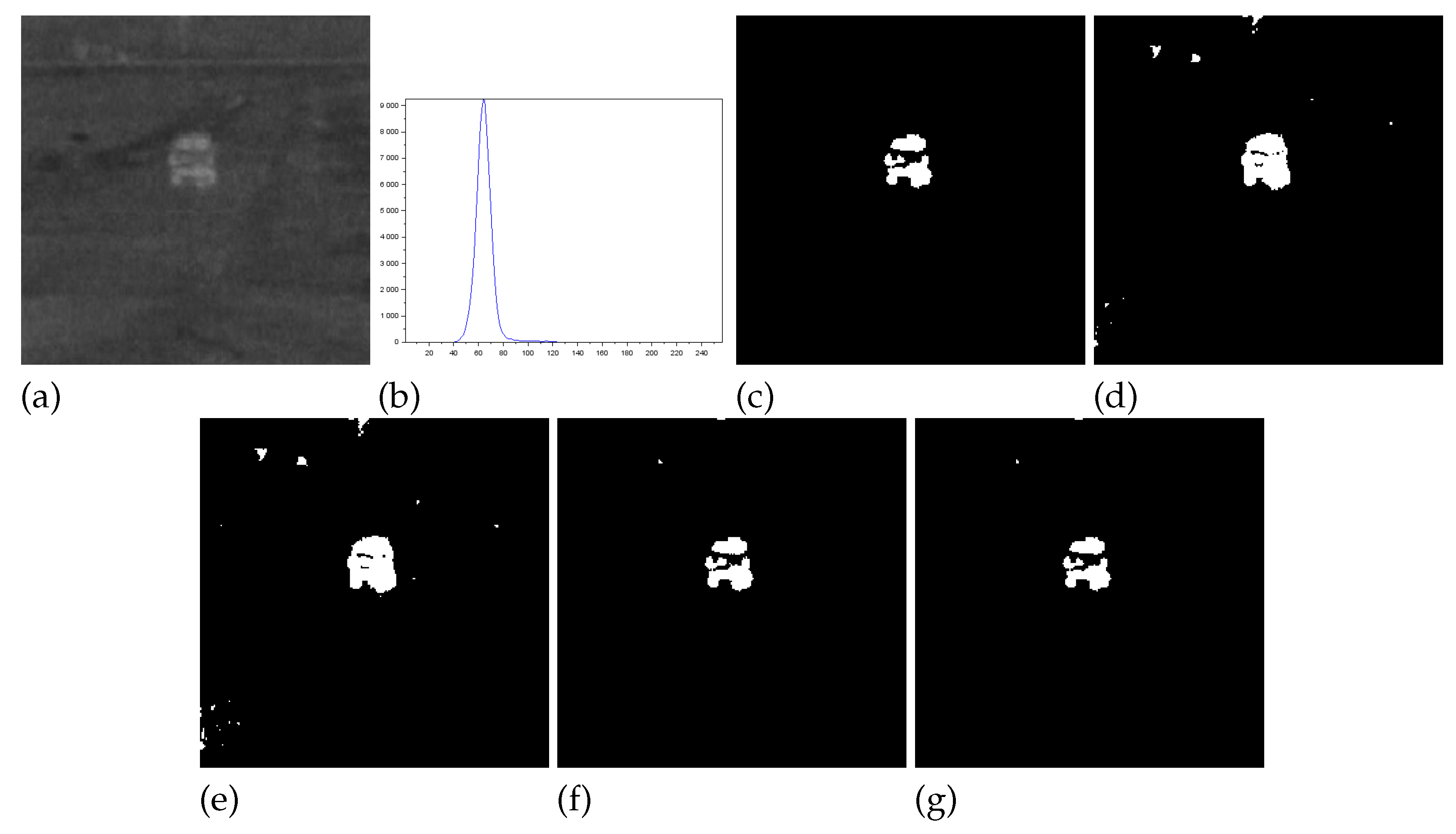

Figure 1 - 000280 image: We notice that Lin & Ou’s method had an RAE equal to zero which implies that the number of pixels in the foreground of ground truth matched the number of pixels in the foreground of the thresholded image. However, visually we can notice differences between the ground truth and the segmented image by the Lin & Ou’s method. The other measures corroborate this observation showing that the behavior of our method was slightly better than the Lin & Ou’s and the Nie et al. methods, whose results were similar. The proposed method exhibited the highest JS value for that image.

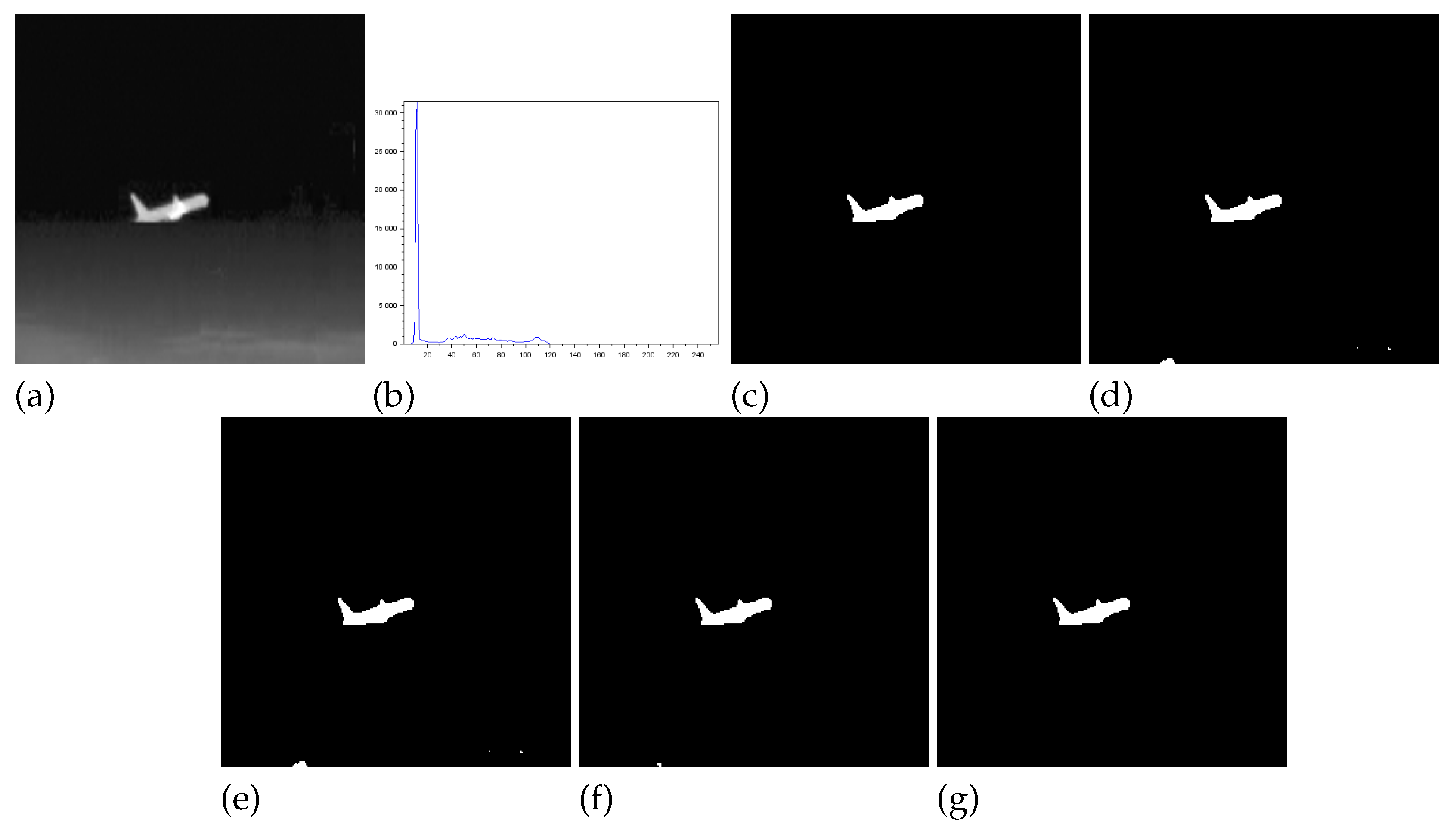

- Figure 2 - Airplane image: Our proposal surpasses all the others obtaining JS (Eq. (13)) greater than and a Fα value close to 1. Albuquerque’s and Lin & Ou’s methods match up and show inferior results if compared to the second best approach that is the Nie et al. in this case. The image obtained with the Lin & Ou’s method was generated with the alternative form given by Eq. (9). This should be an indication that the correlation in the region of background is most strongly captured by Tsallis entropy (see the sharp peak in the histogram in Figure 2(b)).

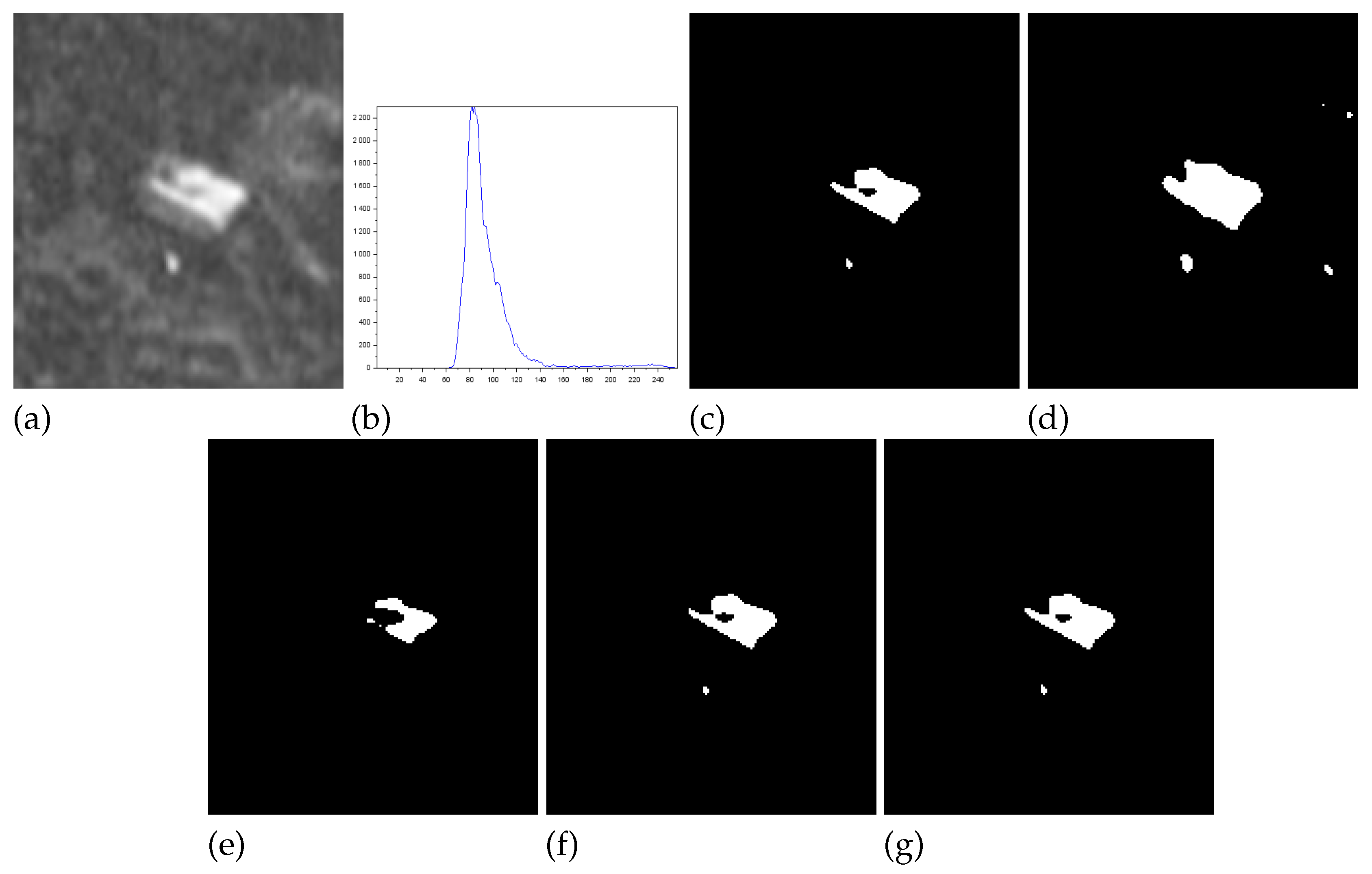

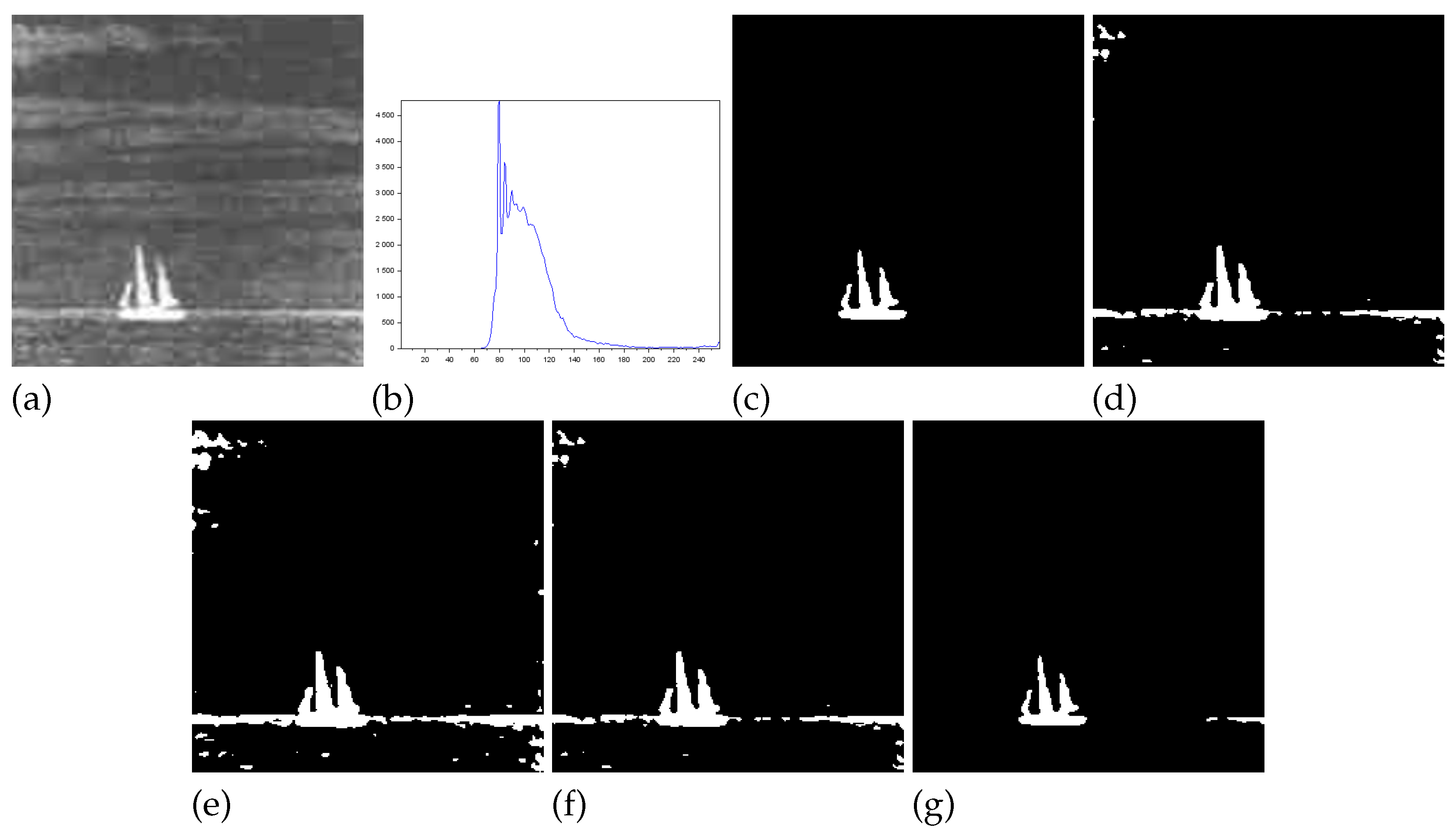

- Figure 3 - Tank image: Our method overcomes all other techniques and provides more than of Jaccard similarity (Eq. (13)). This example shows a significant difference with respect to the misclassified pixeis and JS value in relation to the second-best result, that of Nie et al. Albuquerque and Lin & Ou’s methods performs far from our technique for all the considered measures.

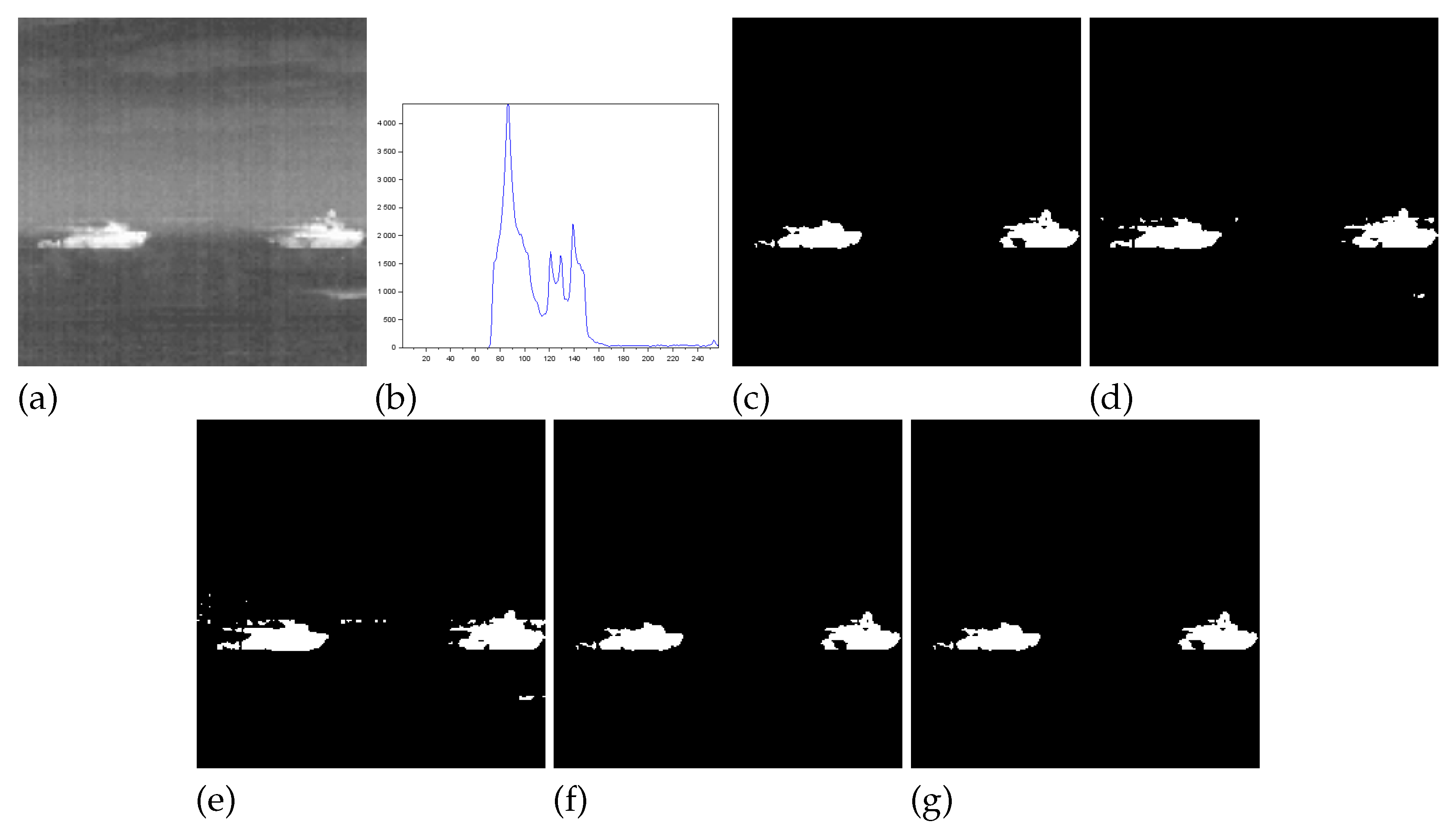

- Figure 4 - Panzer image: Our method and Nie et al. approach achieve perfect segmentation. The number of misclassified pixels, ME, and RAE values are zero. The image obtained with the Lin & Ou’s method was generated with the alternative form (9). However, both Albuquerque and Lin & Ou’s methods obtain segmentations far from the ground truth, as indicated by the values of the considered measures.

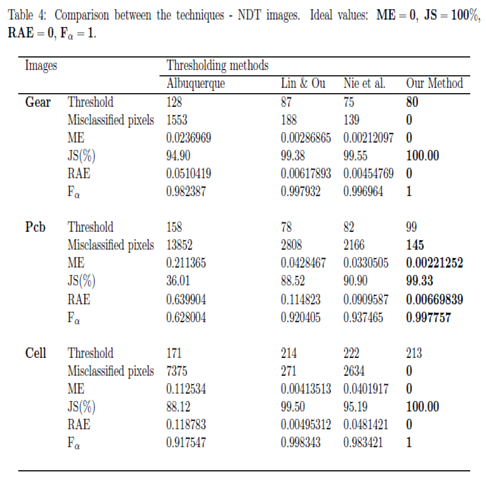

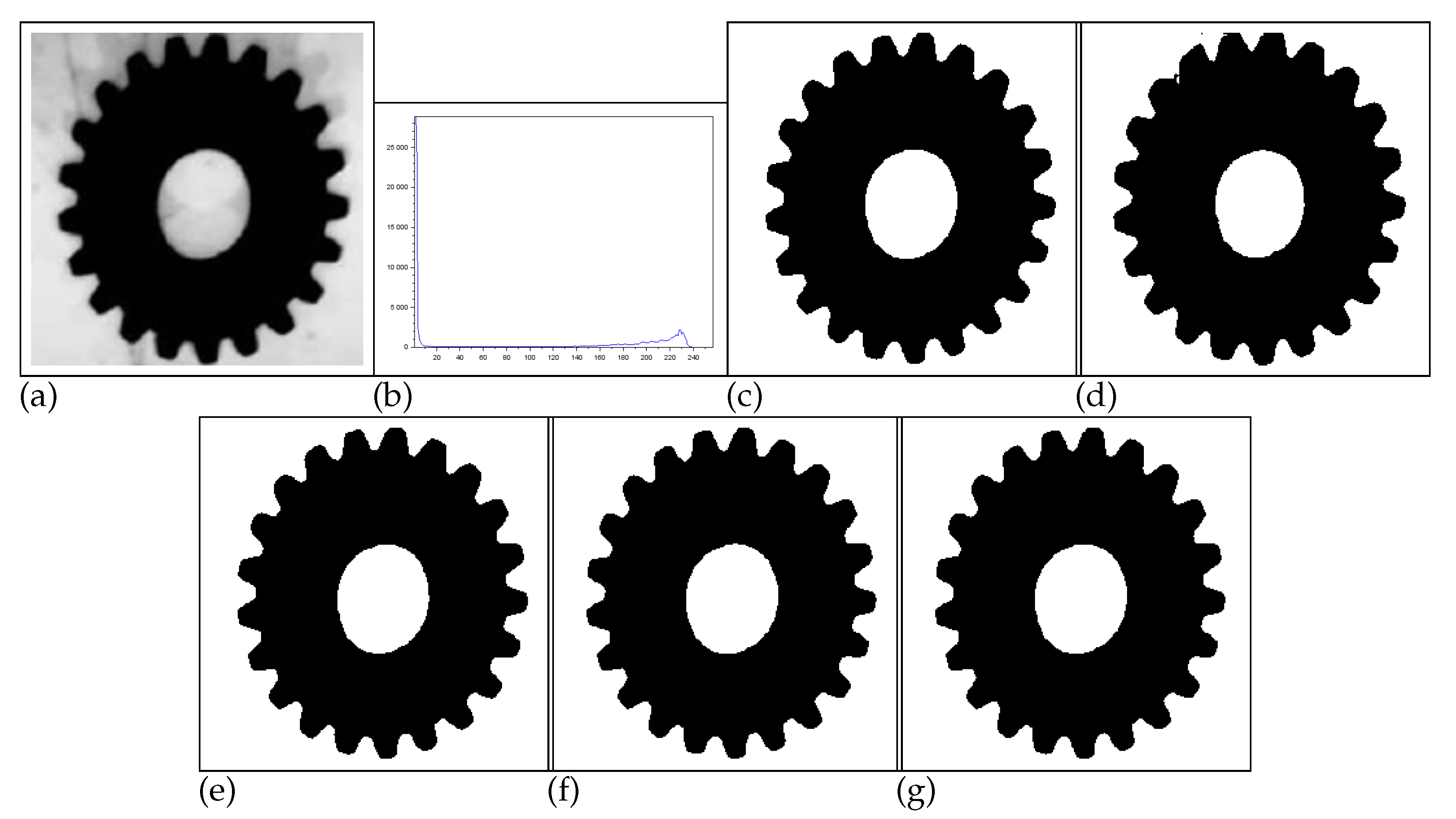

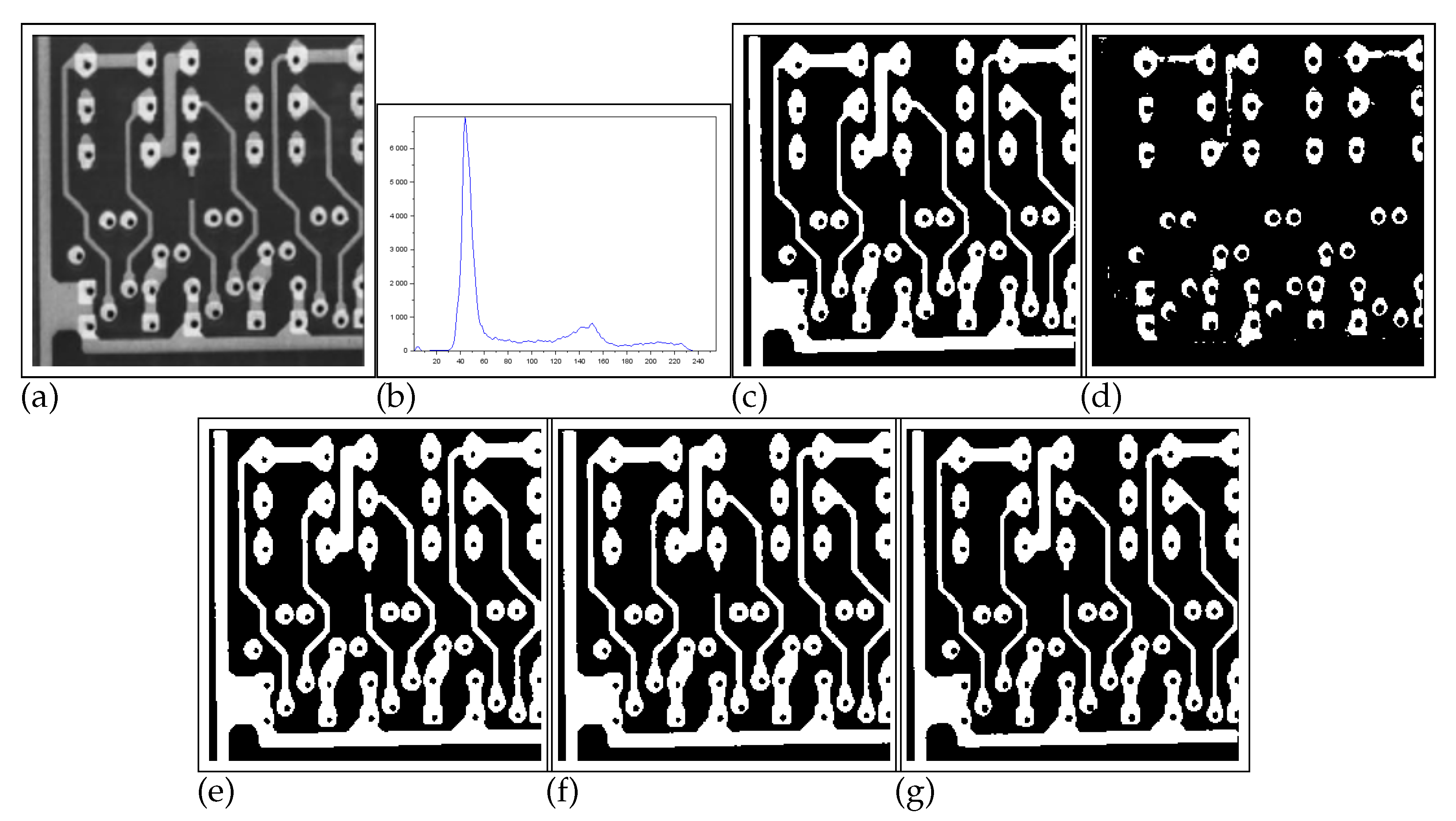

- Figure 8 - Gear image: Although the Lin & Ou’s and the Nie et al. methods have obtained a good visual approximation of the ground truth, the result of our technique matches the ground truth image with , according to Table 4. For this image, the computational experiments have shown that Albuquerque’s method is very sensitive to the variation of parameter q. Since this image was not applied in Lin & Ou’s paper, the q values were determined by trial-and-error to optimize the performance. This allowed Albuquerque’s result to be more than accurate according to JS. The image histogram itself suggests how easy it would be for the method to separate the regions of the image. As it is shown in Figure 8(b) below, there is a sharp peak in the begining histogram. It can be considered as the strong correlations of the pixels in the foreground. Thus, as performed in Lin & Ou’s experiments, the alternative form, (9), was necessary for this image. The same occurred for our method in which we used an alternative form to Eq. (10) given by Eq. (11). This happens due to a weaker long-range correlation in the background composed by the lightest area of the image.

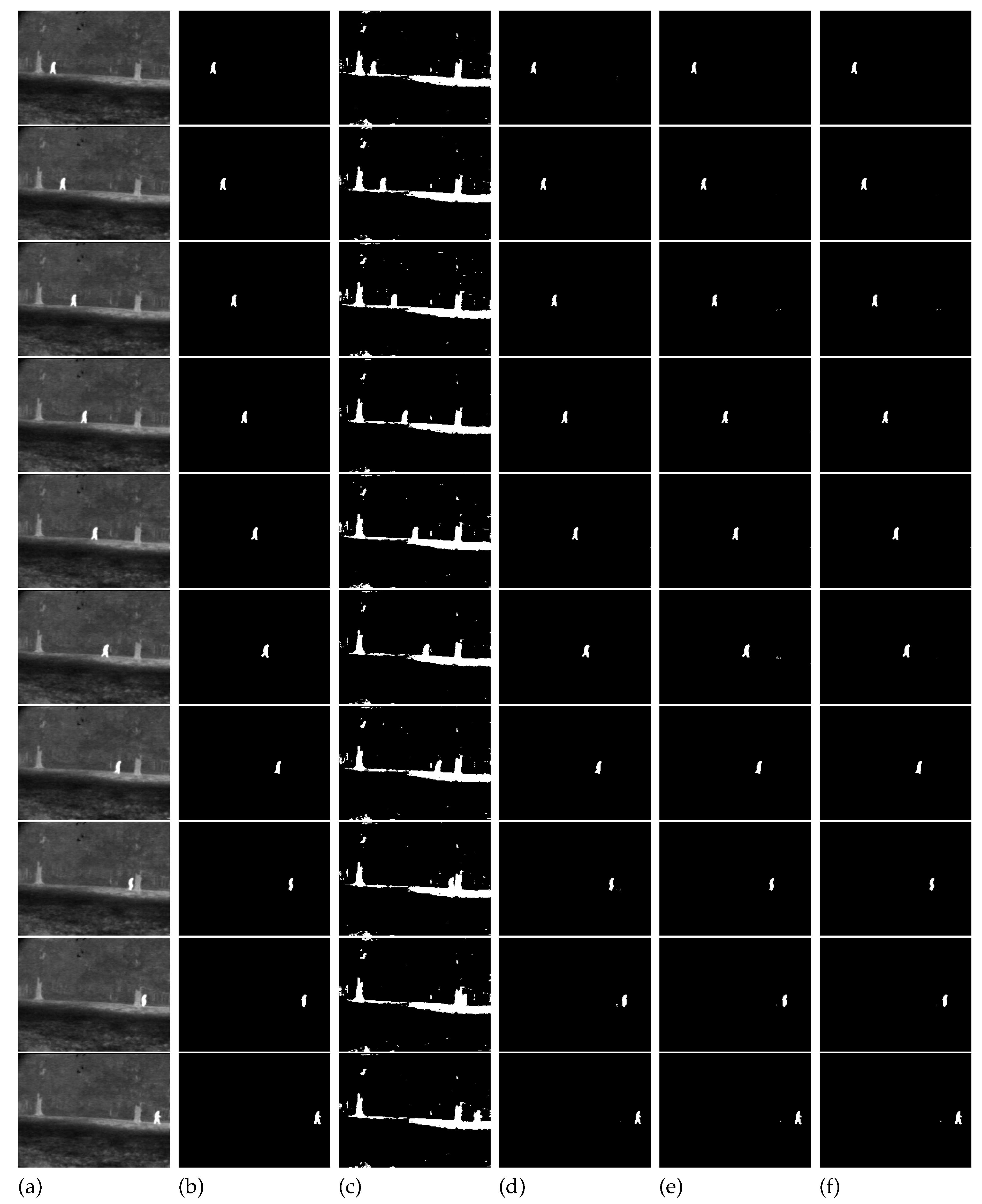

- Figure 9 - Pcb image: In this example, the Nie et al. technique surpasses the one of Lin & Ou’s, having more than of similarity with the ground truth image. The image obtained with the Lin & Ou’s method was generated with the alternative form (9). Even so, our method is more efficient than the others, making the accuracy of , as shown in Table 4.

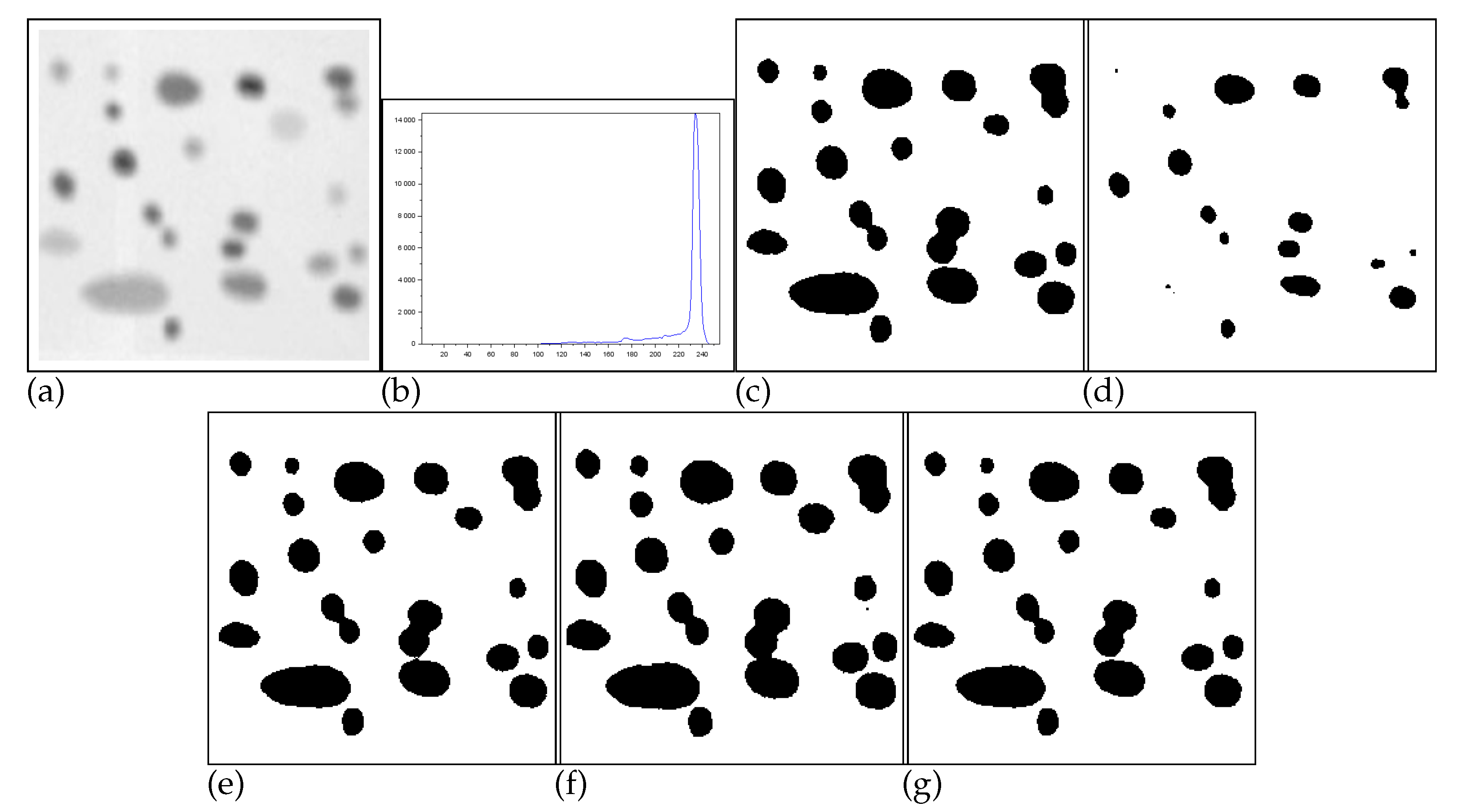

- Figure 10 - Cell image: Lin & Ou’s method is more effective than the Nie et al. method, in this case. However, it is still not possible to overcome our result, which is accurate (see Table 4).

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| F-measure | |

| IR | Infrared Images |

| JS | Jaccard Similarity |

| ME | Misclassification Error |

| NDT | Nondestructive Images |

| PDEs | Partial Differential Equations |

| RAE | Relative Foreground Area Error |

References

- Sezgin, M.; Sankur, B. Survey over image thresholding techniques and quantitative performance evaluation. Journal of Eletronic Imaging 2004, 13, 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- Pun, T. Entropic Thresholding: A New Approach. Computer Graphics and Image Processing 1981, 16, 210–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, M.P.; Esquef, I.A.; Gesualdi Mello, A.R.; Albuquerque, M.P. Image Thresholding Using Tsallis Entropy. Pattern Recognition Letters 2004, 25, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Wu, L.; Zheng, B.; Zan, H. Self-Adaptive Parameter Selection in One-dimensional Tsallis Entropy Thresholding with PARTICLE Swarm Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 3rd International Congress on Image and Signal Processing – CISP, Yantai, China, 2010; pp. 1460–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q.; Ou, C. Tsallis Entropy and the Long-range Correlation in Image Thresholding. Signal Processing 2012, 92, 2931–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, F.; Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Ding, D. A novel generalized entropy and its application in image thresholding. Signal Processing 2017, 134, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Cheng, Y. Statistical Thresholding Method for Infrared Images. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2011, 14, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Wenkang, S.; Liangzhou, C.; Yong, D.; Zhenfu, Z. Infrared Image Segmentation with 2-D Maximum Entropy Method Based on PARTICLE Swarm Optimization (PSO). Pattern Recognition Letters 2005, 26, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparvigna, A.C. Tsallis Entropy in Bi-level and Multi-Level Image Thresholding. International Journal of Sciences 2015, 4, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairuzzaman, A.K.; Chaudhury, S. Masi Entropy Based Multilevel Thresholding for Image Segmentation. Multimedia Tools Applications 2019, 78, 33573–33591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubham, S.; Bhandari, A.K. A Generalized Masi Entropy Based Efficient Multilevel Thresholding Method for Color Image Segmentation. Multimedia Tools Applications 2019, 78, 17197–17238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, A.B. A two-dimensional multilevel thresholding method for image segmentation. Applied Soft Computing 2017, 52, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, A.B. Choosing parameters for Rényi and Tsallis entropies within a two-dimensional multilevel image segmentation framework. Physica A 2017, 466, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Turk, M.; Li, W.; K-C. , L.; Wanga, G. A multilevel image thresholding segmentation algorithm based on two-dimensional K–L divergence and modified pARTICLE swarm. Applied Soft Computing 2016, 48, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathya, P.D.; Kayalvizhi, R. PSO-Based Tsallis Thresholding Selection Procedure for Image Segmentation. International Journal of Computer Applications 2010, 5, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunnava, A.; Naik, M.K.; Panda, R.; Jena, B.; Abraham, A. A novel interdependence based multilevel thresholding technique using adaptive equilibrium optimizer. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, J.N.; Sahoo, P.K.; Wong, A.K.C. A new method for gray-level picture thresholding using the entropy of the histogram. Computer Vision, Graphics, and Image Processing 1985, 29, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Wilkins, C.; Yeager, J. Thresholding Selection Using Rényi’s Entropy. Pattern Recognition 1997, 30, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparavigna, A.C. Shannon, Tsallis and Kaniadakis entropies in bi-level image thresholding. International Journal of Sciences 2015, 4, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, M.; Fang, D.; Zhang, B. Tank segmentation of infrared images with complex background for the homing anti-tank missile. Infrared Physics & Technology 2016, 77, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, M.; Fang, D.; Zhang, B. Unsupervised background-constrained tank segmentation of infrared images in complex background based on the Otsu method. SpringerPlus 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, Q.; Li, D.; Ríha, K. Infrared image segmentation using growing immune field and clone threshold. Infrared Physics & Technology 2018, 88, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.P.S.; Conci, A.; Pérez, M.G.; Andaluz, V.H. Segmentation of infrared images: A new technology for early detection of breast diseases. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT); 2015; pp. 1765–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yang, S.; He, P.; Nie, H. Infrared Electric Image Thresholding Using Two-Dimensional Fuzzy Renyi Entropy. Energy Procedia 2011, 12, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; He, Z.; Li, X.; Zheng, Y. PTB-TIR: A Thermal Infrared Pedestrian Tracking Benchmark. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2020, 22, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M. A step beyond Tsallis and Rényi entropies. Physics Letters A 2005, 338, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Fan, J. Image thresholding segmentation method based on minimum square rough entropy. Applied Soft Computing 2019, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Fan, J. Adaptive granulation Renyi rough entropy image thresholding method with nested optimization. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumiawi, W.A.H.; El-Zaart, A. Gumbel (EVI)-Based Minimum Cross-Entropy Thresholding for the Segmentation of Images with Skewed Histograms. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Upadhyay, M.; Sun, S.; Jiang, T. Automatic Image Thresholding Based on Shannon Entropy Difference and Dynamic Synergic Entropy. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 171218–171239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J. Image Thresholding Method Based on Tsallis Entropy Correlation. Multimed Tools Appl 2025, 84, 9749–9785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, E.; Gabr, M. Enhancng Image Thresholding with Masi Entropy: An Empirical Approach to Parameter Selection. Proceedings of 33rd International Conference in Central Europe on Computer Graphics, Visualization and Computer Vision’2025 (WSCG’2025) 2025, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.S.; Giraldi, G.A. Computing q-index for Tsallis Nonextensive Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of XXII Brazilian Symposium on Computer Graphics and Image Processing – SIBGRAPI, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2009; pp. 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. A Survey: Image Segmentation Techniques. International Journal of Future Computer and Communication, 2014; 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Minaee, S.; Boykov, Y.; Porikli, F.; Plaza, A.; Kehtarnavaz, N.; Terzopoulos, D. Image Segmentation Using Deep Learning: A Survey. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2021, PP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayed, M.E.; Islam, S.S.; Niha, S.I.; Jim, J.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M. Deep learning for medical image segmentation: State-of-the-art advancements and challenges. Informatics in medicine unlocked 2024, 47, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, S.; Bhatt, S.; Faezipour, M. A Systematic Review on Advancement of Image Segmentation Techniques for Fault Detection Opportunities and Challenges. Electronics 2025, 14, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, A.; Orts, S.; Oprea, S.; Villena-Martinez, V.; Martinez-Gonzalez, P.; Rodríguez, J.G. A survey on deep learning techniques for image and video semantic segmentation. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 70, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantaray, L.; Hembram, S.; Panda, R. A New Harris Hawks-Cuckoo Search Optimizer for Multilevel Thresholding of Thermogram Images. Rev. d’Intelligence Artif. 2020, 34, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachs-Lopes, G.A.; Santos, R.M.; Saito, N.; Rodrigues, P.S.S. Recent nature-Inspired algorithms for medical image segmentation based on tsallis statistics. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2020, 88, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Rajam, V. Water-body segmentation from satellite images using Kapur’s entropy-based thresholding method. Comput. Intell. 2020, 36, 1242–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z. An improved emperor penguin optimization based multilevel thresholding for color image segmentation. Knowl. Based Syst. 2020, 194, 105570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukanthi.; Murugan, S.; Hanis, S. Sukanthi.; Murugan, S.; Hanis, S. Binarization of Stone Inscription Images by Modified Bi-level Entropy Thresholding. Fluctuation and Noise Letters, 2021; 2150054. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, T. ; Kumar., S. A novel binarization technique based on Whale Optimization Algorithm for better restoration of palm leaf manuscript. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 2020; 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi, L.; Zaart, A.E. A survey of entropy image thresholding techniques. 2012 2nd International Conference on Advances in Computational Tools for Engineering Applications (ACTEA), 2012; 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, J.; Sahoo, P.; Wong, A. A new method for gray-level picture thresholding using the entropy of the histogram. Comput. Vis. Graph. Image Process. 1985, 29, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.; Wilkins, C.; Yeager, J. Threshold selection using Renyi’s entropy. Pattern Recognition 1997, 30, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rényi Entropies. In On Measures of Information and their Characterizations; Aczél, J.; Da’oczy, Z., Eds.; Elsevier, 1975; Vol. 115, Mathematics in Science and Engineering, pp. 134–172. [CrossRef]

- Tsallis, C. Possible Generalizations of Boltzmann-Gibbs Statistics. Journal of Statistical Physics 1988, 52, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsallis, C. Nonextensive statistics: Theoretical, experimental and computational evidences and connections. BRAZ.J.PHYS. 1999, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparvigna, A.C. Tsallis Entropy in Bi-level and Multi-Level Image Thresholding. International Journal of Sciences 2015, 4, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yang, J.; Zhao, X.; Liu, M.; Wu, D. Multispectral Image Segmentation Based on a Fuzzy Clustering Algorithm Combined with Tsallis Entropy and a Gaussian Mixture Model. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell system echcnical Journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar]

- Tsallis, C. Possible generalization of Boltzmann-Gibbs statistics. Journal of statistical physics 1988, 52, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Wu, L.; Zheng, B.; Zan, H. Self-adaptive parameter selection in one-dimensional tsallis entropy thresholding with Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2010 3rd International Congress on Image and Signal Processing; 2010; pp. 1460–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Fan, J. Adaptive Kaniadakis entropy thresholding segmentation algorithm based on particle swarm optimization. Soft Computing 2020, 24, 7305–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunnava, A.; Naik, M.; Panda, R.; Jena, B.; Abraham, A. A differential evolutionary adaptive Harris hawks optimization for two dimensional practical Masi entropy-based multilevel image thresholding. J. of King Saud University – Computer and Information Sciences, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Ray, N. Adaptive shape prior in graph cut image segmentation. Pattern Recognition 2013, 46, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Fan, J. Infrared pedestrian segmentation algorithm based on the two-dimensional Kaniadakis entropy thresholding. Knowledge-Based Systems 2021, 225, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Sun, J.; Zheng, N.; Tang, X.; Shum, H. Learning to Detect A Salient Object. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 33, 353–367. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.R.; Fowlkes, C.C.; Malik, J. Learning to Detect Natural Image Boundaries Using Local Brightness, Color, and Texture Cues. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2004, 26, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).