Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

12 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

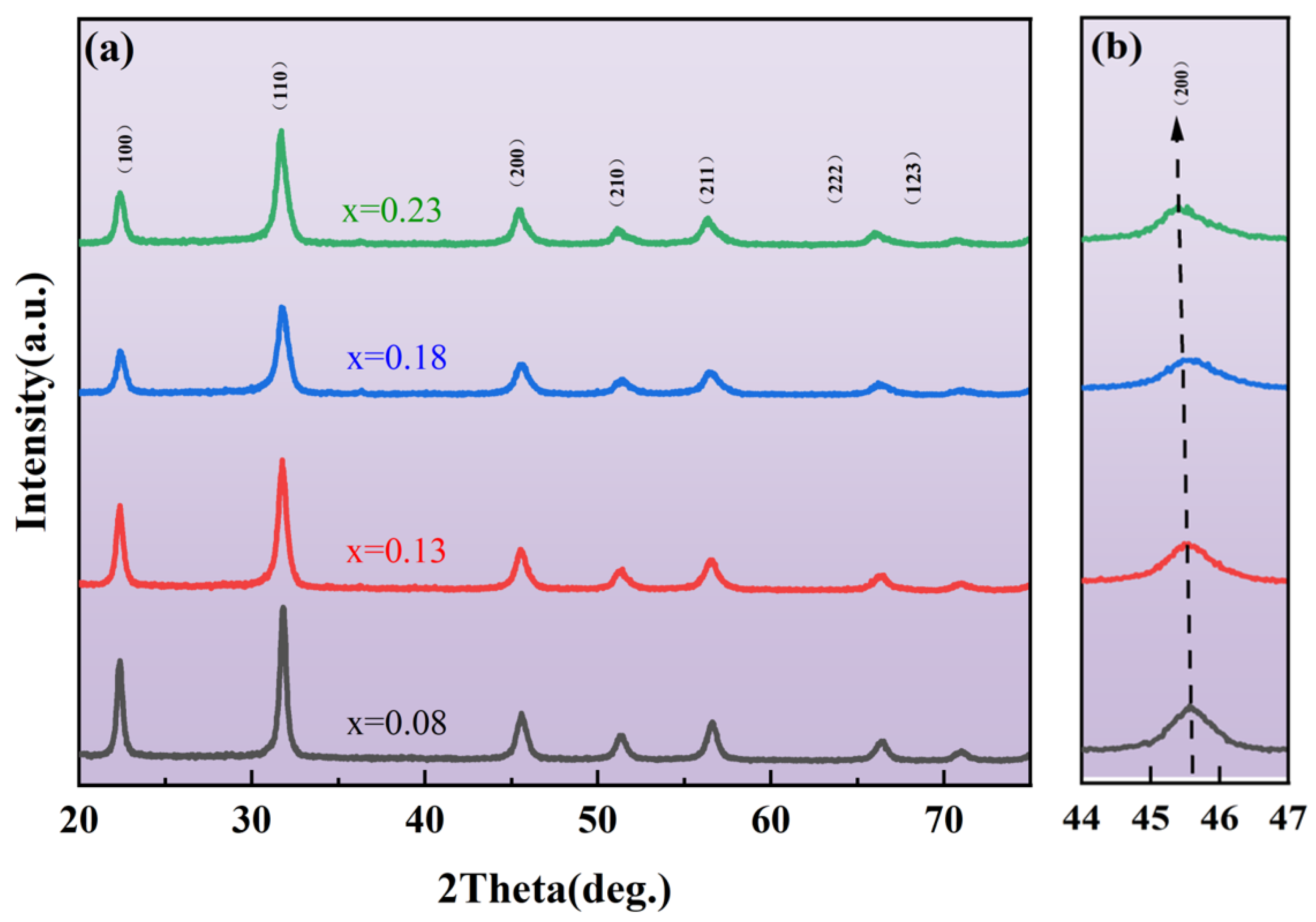

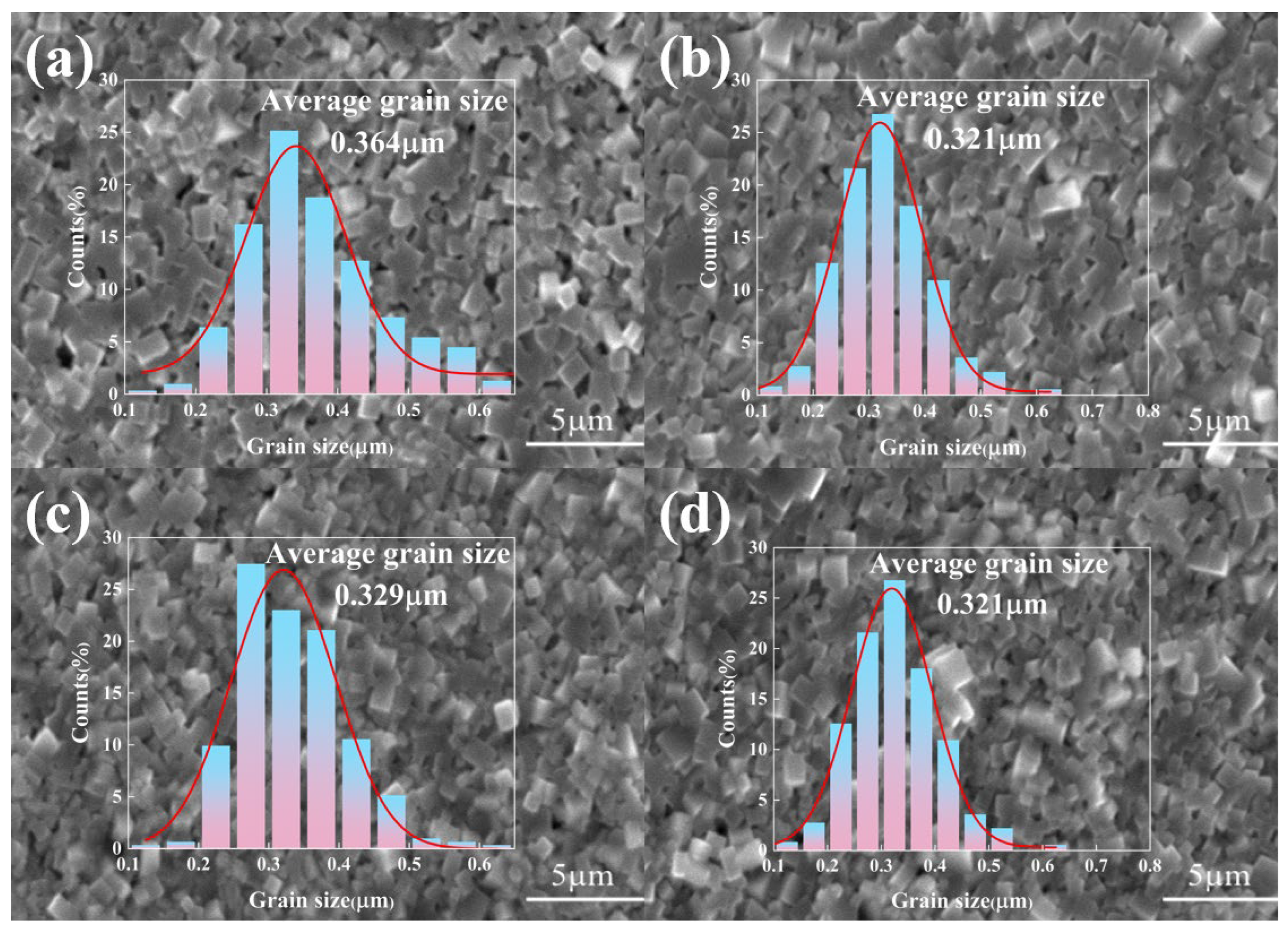

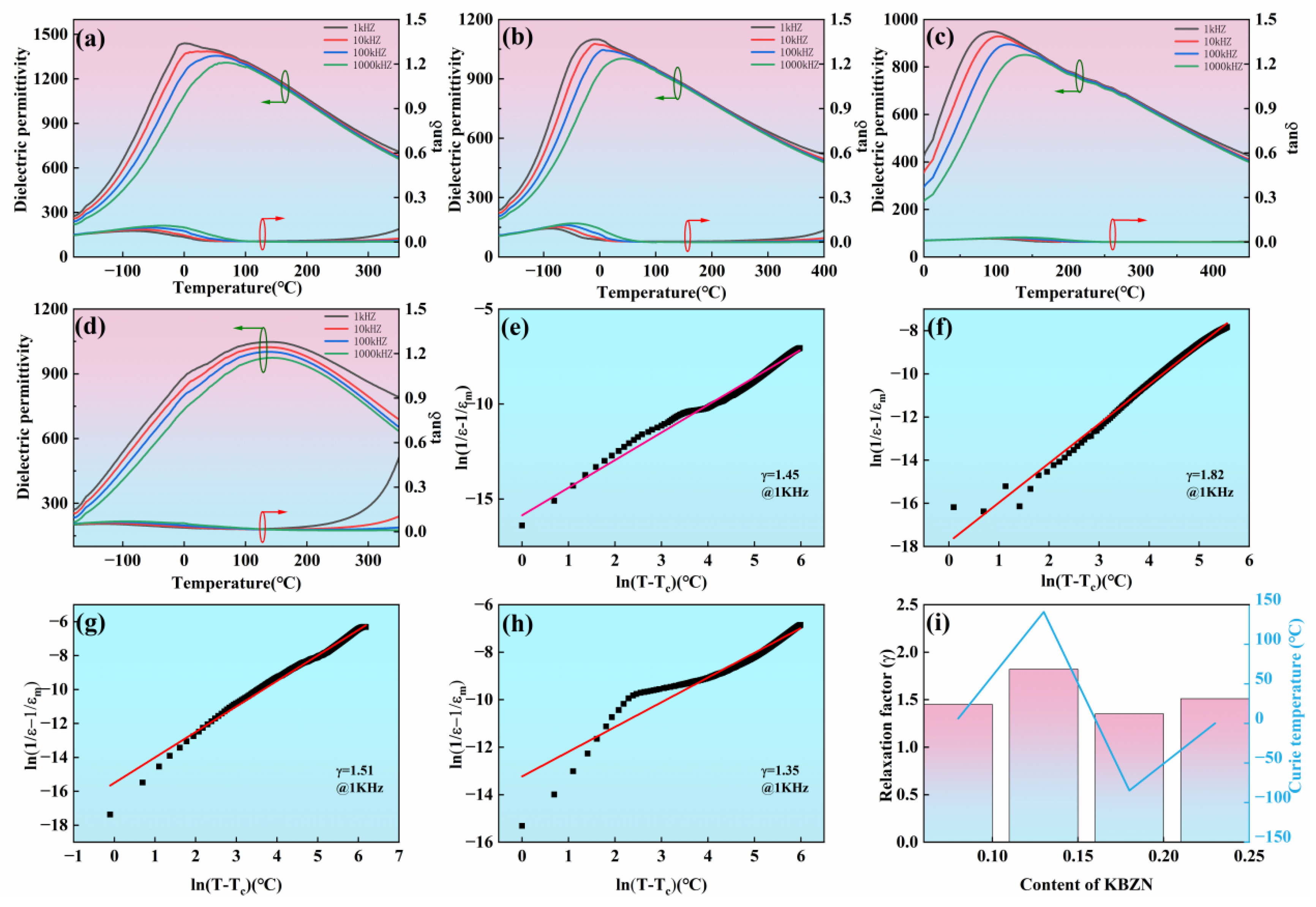

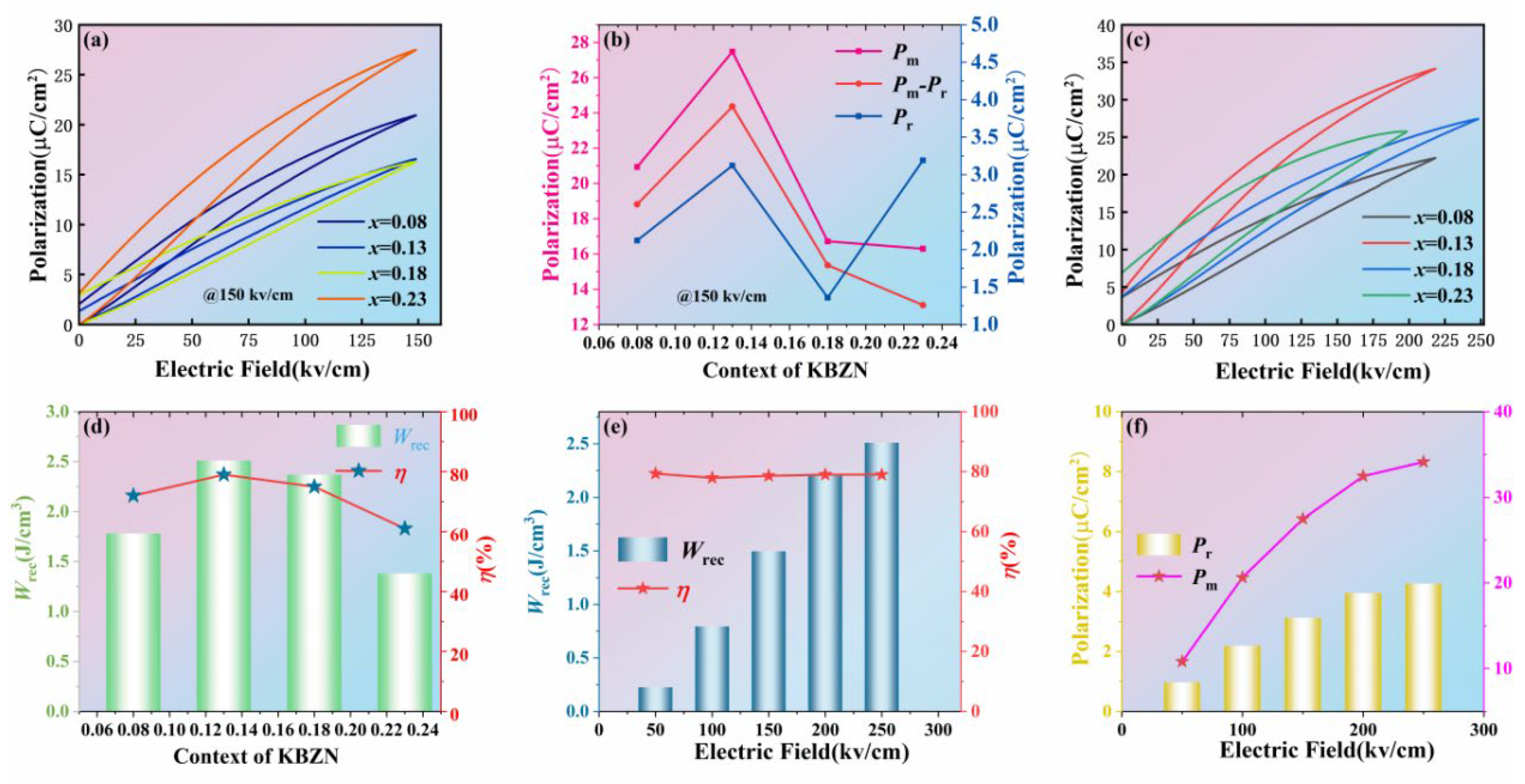

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, M.; Jiang, J.; Shen, Z.; Lin, Y.; Nan, C.-W.; Shen, Y. High-Energy-Density Ferroelectric Polymer Nanocomposites for Capacitive Energy Storage: Enhanced Breakdown Strength and Improved Discharge Efficiency. Mater. Today 2019, 29, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Cai, Z.; Chen, L.; Wu, L.; Huan, Y.; Guo, L.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Ultra-high energy storage performance in lead-free multilayer ceramic capacitors via a multiscale optimization strategy. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 4882–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Kong, X.; Li, F.; Hao, H.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, J.-F.; Zhang, S. Perovskite lead-free dielectrics for energy storage applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 102, 72–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Li, X.; Xu, D.; Chen, Q.; Gao, T.; Tan, Z.; Zhu, J. Intrinsic and extrinsic contributions to energy storage performance in potassium sodium niobate–based ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 4824–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Kong, X.; Li, Q.; Lin, Y.-H.; Zhang, S.; Nan, C.-W. Excellent Energy Storage Properties Achieved in Sodium Niobate-Based Relaxor Ceramics through Doping Tantalum. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 32218–32226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Sun, P.; Zheng, P.; et al. Significantly tailored energy-storage performances in Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-SrTiO3-based relaxor ferroelectric ceramics by introducing bismuth layer-structured relaxor BaBi2Nb2O9 for capacitor application. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 5234–5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Fu, B.; Zhang, J.; Du, H.; Zong, Q.; Wang, J.; Pan, Z.; Bai, W.; Zheng, P. Superb Energy Storage Capability for NaNbO3-Based Ceramics Featuring Labyrinthine Submicro-Domains with Clustered Lattice Distortions. Small 2023, 19, e2303915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Lin, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Du, H. Significant increase in comprehensive energy storage performance of potassium sodium niobate-based ceramics via synergistic optimization strategy. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 45, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dai, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Rafiq, M.N.; Tsukada, S.; Cong, Y.; Karaki, T.; Zhou, S. Preparation and investigation of K0.5Na0.5NbO3-Bi(Sr0.5Hf0.5)O3 transparent energy storage ceramic. J. Power Sources 2025, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Gao, F.; Du, H.; Jin, L.; Yan, L.; Hu, Q.; Yu, Y.; Qu, S.; Wei, X.; Xu, Z.; et al. Grain size engineered lead-free ceramics with both large energy storage density and ultrahigh mechanical properties. Nano Energy 2019, 58, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, B.; et al. Energy storage behavior in ErBiO3-doped (K, Na) NbO3 lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 3717–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Dan, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Huang, H.; He, Y. Recent advances in lead-free dielectric materials for energy storage. Mater. Res. Bull. 2019, 113, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Advances in Lead-Free Piezoelectric Materials; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, R.; Chen, Q.; Gao, T.; Zhu, J.; Xing, J.; Chen, Q. BaTiO3-based lead-free relaxor ferroelectric ceramics for high energy storage. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 3916–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chao, X.; Wu, D.; Liang, P.; Yang, Z. Evaluation of birefringence contribution to transparency in (1-x)KNN-xSr(Al0.5Ta0.5)O3 ceramics: A phase structure tailoring. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 798, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Huang, Y.; Wu, B.; et al. Energy storage behavior in ErBiO3-doped (K, Na) NbO3 lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 3717–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, M.; Shao, S. Machine learning for halide perovskite materials. Nano Energy 2020, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Irshad, M.S.; Kong, X.; Panfilov, P.; Yang, L.; Guo, J. Potassium sodium niobate-based transparent ceramics with high piezoelectricity and enhanced energy storage density. J. Alloy. Compd. 2023, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Li, G.; Tao, H.; Wu, J.; Xu, Z.; Li, F. Full characterization for material constants of a promising KNN-based lead-free piezoelectric ceramic. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 5641–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Li, D.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Ren, X. A strategy for high performance of energy storage and transparency in KNN-based ferroelectric ceramics. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, N.; Du, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hao, X. Bi(Mg0.5Ti0.5)O3 addition induced high recoverable energy-storage density and excellent electrical properties in lead-free Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3-based thick films. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Huang, K.; Jiang, T.; Zhou, X.; Shi, Y.; Ge, G.; Shen, B.; Zhai, J. Significantly enhanced energy storage density and efficiency of BNT-based perovskite ceramics via A-site defect engineering. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 30, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. Energy storage performance of SrSc0.5Nb0.5O3 modified (Bi,Na)TiO3-based ceramic under low electric fields. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 106, 2366–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, R. Excellent energy-storage performances in La2O3 doped (Na,K)NbO3-based lead-free relaxor ferroelectrics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 5466–5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Xie, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Xi, Z.; Ren, X. Improved energy storage density and efficiency of (1−x)Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3-xBiMg2/3Nb1/3O3 lead-free ceramics. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Yang, H. Synergistically enhanced discharged energy density and efficiency achieved in designed polyetherimide-based composites via asymmetrical interlayer structure induced optimized interface effectiveness. Mater. Horizons 2024, 11, 4759–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, Q.; Yang, D.; Zhao, X.; et al. Lead-free (K, Na) NbO3-based ceramics with high optical transparency and large energy storage ability. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 101, 2321–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Li, Y.; Jia, P.; Wang, Y. The high nano-domain improves the piezoelectric properties of KNN lead-free piezo-ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 25035–25042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ge, G.; Zhu, K.; Bai, H.; Sa, B.; Yan, F.; Li, G.; Shi, C.; Zhai, J.; Wu, X.; et al. Simultaneously achieving high performance of energy storage and transparency via A-site non-stoichiometric defect engineering in KNN-based ceramics. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Du, H.; Jin, L.; Poelman, D. High-performance lead-free bulk ceramics for electrical energy storage applications: design strategies and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 18026–18085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Xie, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Li, J.; Ren, X. Effective Strategy to Achieve Excellent Energy Storage Properties in Lead-Free BaTiO3-Based Bulk Ceramics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 30289–30296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Xie, J.; Fan, X.; Ding, X.; Liu, W.; Zhou, S.; Ren, X. Enhanced energy storage properties and stability of Sr(Sc0.5Nb0.5)O3 modified 0.65BaTiO3-0.35Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3 ceramics. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H. Ultrahigh Dielectric Energy Density and Efficiency in PEI-Based Gradient Layered Polymer Nanocomposite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Ma, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Miao, F.; Huang, Y.; Chen, K.; Wu, W.; Wu, B. Coexistence of excellent piezoelectric performance and high Curie temperature in KNN-based lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Marcos, F.; Fernandez, J.F.; Ochoa, D.A.; García, J.E.; Rojas-Hernandez, R.E.; Castro, M.; Ramajo, L. Understanding the piezoelectric properties in potassium-sodium niobate-based lead-free piezoceramics: Interrelationship between intrinsic and extrinsic factors. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 37, 3501–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, Q.; Yang, H. Enhancement of recoverable energy density and efficiency of K0.5Na0.5NbO3 ceramic modified by Bi(Mg0.5Zr0.5)O3. Mater. Today Energy 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Bünzli, J.-C.; Yusoff, A.R.b.M.; Noh, Y.-Y.; Gao, P. Vitamin needed: Lanthanides in optoelectronic applications of metal halide perovskites. Mater. Sci. Eng. R: Rep. 2022, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Dai, Z.; Liu, C.; Yasui, S.; Cong, Y.; Gu, S. Enhanced photoelectric properties for BiZn0.5Zr0.5O3 modified KNN-based lead-free ceramics. J. Alloy. Compd. 2023, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.-E.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Qi, X.-W. Structure and electrical properties of SrZrO3-modified (K,Na,Li)(Nb,Ta)O3 lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 29, 3905–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kumar, R.; Singh, S. Coexistence of negative and positive electrocaloric effect in lead-free 0.9(K0.5Na0.5)NbO3 - 0.1SrTiO3 nanocrystalline ceramics. Scr. Mater. 2018, 143, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, N.; Du, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hao, X. Bi(Mg0.5Ti0.5)O3 addition induced high recoverable energy-storage density and excellent electrical properties in lead-free Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3-based thick films. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhu, Y.; Marwat, M.A.; Fan, P.; Xie, B.; Salamon, D.; Ye, Z.-G.; Zhang, H. Enhanced energy-storage performance with excellent stability under low electric fields in BNT–ST relaxor ferroelectric ceramics. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 7, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Yang, H.; Lin, Y.; Li, J. Improving the energy storage performances of Bi(Ni0.5Ti0.5)O3-added K0.5Na0.5NbO3-based ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 14920–14927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Yu, Y.; Lin, Y. Energy storage performance of K0.5Na0.5NbO3-based ceramics modified by Bi(Zn2/3(Nb0.85Ta0.15)1/3)O3. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).