1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a condition that carries a high burden of mortality and morbidity[

1]. Patients with severe COPD due to many different mechanisms, such as ventilatory constraints, impaired gas exchange, or haemodynamic limitation[

2]. Above all of them, expiratory flow limitation may be a key component to develop breathlessness and exercise limitation[

3]. This issue worsens as exercise progresses, and the patient tries to increase respiratory rate at the cost of shortening expiratory time. This situation will lead to an unavoidable dynamic hyperinflation, with the development of intrinsic end-expiratory positive pressure (PEEPi) [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Final consequence of this exercise dynamic hyperinflation is the development of a “neuro-ventilatory uncoupling”.[

6] Despite an increase in inspiratory effort, trying to meet the breathing demands induced by exercise, patients are unable to increase, in a proportional manner, the tidal volume. Thus, dyspnoea and inspiratory muscle activity (both closely linked) will increase while breathing efficiency will reach a plateau, limiting exercise capacity[

8].

The use of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) has been thoroughly researched as a tool to decrease such neural respiratory drive (NRD) uncoupling of severe COPD patients, firstly by decreasing inspiratory muscle use, outweighing PEEPi and increasing tidal volume, mostly in rest[

9,

10] , but also during exercise[

11].

Therefore, NIV has been proposed as a strategy to enhance exercise capacity of severe COPD patients to perform exercise. While early reports showed conflicting results and an initial meta-analysis did not showed evidence of benefit[

12], there is a wide heterogenicity on patient selection, protocols, outcome measures and NIV titration. So, some studies have focused in naïve NIV users, with poor results[

13], others have evaluated alternative ventilatory modes[

14,

15], others have focused on physiological improvements (for example, in muscle blood flow[

16] or in inflammatory profile[

17,

18]) , in the improvement of ventilatory efficiency and exercise capacity[

19] or in long term effects[

20,

21,

22,

23].

On the other hand, HFT is a relatively stablished technique that provides high flow (usually >30-40 L/m) of conditioned gas (air and oxygen mixture with selected FiO2, heated and humified to 100% relative humidity)[

24]. It has also been studied as a tool to increase the exercise capacity on COPD patients. While there is much less evidence of its benefits, and most of the studies are limited, it seems as a promising tool, with better tolerance, than NIV, to improve exercise capacity[

25].

More recent metanalysis have demonstrated the ability of NIV to improve exercise tolerance and many physiological measures, such as oxygen consumption, and dyspnoea, over HFT[

26].

While there have been several studies identifying physiological effects of adding NIV during exercise, the effect of HFT over NRD, compared with NIV has not been directly researched.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the way NIV and HFT may decrease NRD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

The inclusion criteria for the study consisted of patients with COPD who were on the lung transplant waiting list and already evaluated by the Lung Transplant Unit at 12 de Octubre University Hospital. Criteria to be included in waiting lung transplant list were according to national guidelines.[

27]. COPD was diagnosed according to GOLD guidelines, with plethysmography confirming air trapping (a residual volume greater than 120% of the predicted value). Evidence of dynamic air trapping during exercise was required, demonstrated by flow-volume curve analysis and the visual identification of expiratory flow limitation as previously described. Additionally, patients needed to be already adapted and adherent to home non-invasive ventilation (NIV) as a bridge to transplantation. A minimum use of >4h/day for more than 20 out of 30 days of the previous month was required.

Exclusion criteria included the presence of uncontrollable comorbidities that limited the ability to perform physical exercise (such as uncontrolled ischemic heart disease, severe pulmonary hypertension, or neuromuscular disorders), refusal to use NIV or to participate in the study, inability to carry out the proposed exercise protocol under baseline conditions or with ventilatory support, and the absence of reliable EMG signals for analysis.

2.2. Ethical and Data Management Protocol

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital 12 de Octubre (Resolution 18/025) and complied with the Spanish Organic Law on Data Protection 15/1999. All participants provided informed consent, and their inclusion in the study did not affect their status on the lung transplant waiting list.

An anonymized database, linked to clinical records through consecutive codes, was stored on a secure server within the Pneumology Department, accessible only to the principal investigator.

The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT04597606).

2.3. Study Design

Experimental, cross-sectional, controlled study, with one arm and three different conditions (NIV, conventional oxygen therapy -COT-, HFT) for the same cohort

2.4. Protocol

For the exercise testing, a semi-recumbent cycloergometer was used. The subjects were instructed to cycle with their arms relaxed along their trunk and avoid grasping the handlebars or support bars to avoid cross contamination with pectoral muscle activity (due to grip over the handlebar) [

28]. The exercise tests comprised 10 minutes of exercise and 5 minutes of recovery (unloaded cycle steadily decreasing pace until complete stop). They were conducted in three different days under the following conditions:

COT: Patients began with their usual home oxygen flow and then titrated to maintain an SpO2 >92% through all the exercise.

NIV: titrated as described above, with supplemental oxygen if needed, to maintain SpO2>92%.

HFT (Airvo 2®, Fisher &Paykel, Auckland, NZ): A flow of 40 litres per minute was selected. Supplemental O2 flow was initially set –before starting exercise- to maintain an estimated FiO2 similar to that obtained to achieve a SpO2>92% with COT[

29].

Each day, before starting the exercise, three maximum inspiratory manoeuvres were performed with simultaneous electromyography (EMG) recording to allow calibration and normalization. No other pulmonary function was measured during or after the exercise.

At baseline, participants underwent a “ramp test” with incremental loads up to their maximum tolerated workload. Then, a 75% load of that maximal tolerated one was selected to perform the tests.[

30,

31] Patients were already included in the exercise protocol for lung transplantation program, so they all have previously performed at least three sessions of exercise in cycloergometer under COT, thus, they can be considered already acclimated. Three constant load exercise tests were performed over three consecutive days. The first day was performed under COT, and at the end of the exercise testing, a 5 min trial with NIV, cycling under free protocol for pressure titration, was performed to titrate pressures. All of the patients underwent exercise with an Astral 150® ventilator (Resmed©, CA, USA®) under ST mode, as it has been tested previously capable of providing enough pressurization support and capable of different programs [

32]. Expiratory pressure was titrated to avoid ineffective efforts and trigger delay in online flow/pressure, and inspiratory pressure was titrated in order to diminish at least 20% of neural respiratory drive (NRD) as measured by parasternal EMG (online EMG Root Mean Square traces were continuously monitored to obtain that decrease, with no offline later calculations in that phase).

2.5. Signal Recording

During the test, patients were connected to a recording system equipped with the following sensors:

Parasternal and sternocleidomastoid surface EMG was performed with electrodes placed on both sides of the second parasternal space, as previously described[

33].

Combined transcutaneous CO2 and pulse oximetry oxygen saturation sensor (Sentec TCM®, Therwill, Switzerland).

Chest and abdominal respiratory inductance plethysmography (RIP) belts (Braebon QZ-RIP, Braebon Medical Corp, Ontario, Canada), for determining inspiratory and expiratory onset.

Flow (raw signal from a calibrated pneumotachograph placed between tubing and usual oronasal mask) was recorded by means of a differential pressure transducer (Powerlab Spirometer FE141, AD Instruments, Australia) and mask pressure (Powerlab MLT844 , AD Instruments, Australia)

All sensors were connected to a digital-to-analogue converter (PowerLab SP, ADInstruments, Australia). The sampling frequency was set to 2000 Hz.

EMG signal was processed to calculate NRD as previously described [

34]. Briefly, an 80 Hz high-pass filter was applied, and the root mean square (RMS) method was employed to normalize the signal, and it was referenced to the maximum peak obtained in a MIP manoeuvre. Both peak and area under the curve (AUC) of EMG contraction was calculated. We avoided non-respiratory tonic artefacts in the EMG by estimating the onset of inspiration from the belts signal. NRD was calculated as the product of the respiratory rate and both the peak and area under the peak RMS as described by Jolley et al.[

35].

2.6. Data Collection

Anthropometric variables were described, and functional parameters were collected from the last spirometry performed. Spirometry was performed according to current national guidelines[

36] and the closest test to the exercise day was selected (all within the previous 6 months).

The following data were collected at different time points during the exercise test: at baseline, and at minutes 1, 4, 7, and 10 of exercise, as well as at 3 and 5 minutes into the recovery period:

Respiratory variables: Respiratory rate (RR), dyspnoea perception measured by the BORG test scale, asked as the breathless sensation (n) and transcutaneous monitored CO2 (tcCO2, mmHg).

NRD as described by Jolley et al[

35]. Briefly, we choose to measure parasternal (EMGpara) and sternocleidomastoid (EMGscm) signal by attaching 2 electrodes as described previously[

11] . EMGpara and EMGscm signal was normalized and transformed through a RMS protocol. NRD for each point of the study was calculated as the product of respiratory rate by peak RMS EMGpara%max. For calculations, the non-respiratory tonic artifacts in the EMG were avoided, as inspiration was also signalled by the inductive plethysmography belts, and peak was referenced to the mean baseline EMG RMS activity[

37]. Peak of RMS signal of EMGpara and EMGscm (µv) and area under the curve AUC of both (µv) in every step of time by LabChart ® Software (ADInstruments, Australia) was analysed.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were described using mean and standard deviation.

A general linear model with repeated measures (mixed ANOVA) was used to analyse NRD variables, including the maximum parasternal RMS value across all measurements, with the signal normalized by transmissibility—both for the peak and the area under the parasternal EMG signal.

The same linear model was applied to repeated measures of the maximum sternocleidomastoid RMS value, also normalized, for both the peak and the area of the EMG signal. For the ANOVA, the F value, degrees of freedom, and corresponding p-value were reported to assess the statistical significance of differences across conditions.

It was considered that, in the analysis of the entire sample, the amplitude of the global EMG signal might have been underestimated due to patients who paused during exercise. Therefore, the same mixed factorial repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on a subset of patients who did not stop pedalling during the tests.

The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Chicago, Illinois).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

During the study period, 47 patients with COPD were enrolled in the lung transplant program. Of these, 23 were receiving home noninvasive ventilation (NIV) and met the criteria for inclusion. One patient underwent lung transplantation before the trial commenced, and two others were excluded due to consistently unreliable EMG signals despite multiple attempts. As a result, the final study cohort consisted of 20 patients with severe COPD, 30% of whom were women. Detailed anthropometric measurements, pulmonary function test results, and arterial blood gas values are presented in

Table 1.

Comparative analysis showed that ventilatory pressure parameters differed significantly between home NIV settings and exercise testing conditions. Specifically, the mean inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) increased from 19.57 ± 5.02 cmH₂O during home use to 21.93 ± 5.73 cmH₂O during exercise (p<0.01), indicating a clinically meaningful rise in pressure requirements during physical activity, as outlined in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Ventilator Parameters.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and Ventilator Parameters.

| Patient Characteristics |

|

| Variable |

Mean ± SD |

| Age (years) |

60.0 ± 3.9 |

| FEV₁ (mL; % predicted) |

580 ± 129; 19.3 ± 4.14 |

| FVC (mL; % predicted) |

2038.5 ± 739.6; 51.5 ± 18.01 |

| RV (mL; % predicted |

6240.6 ± 1242.5; 286.4 ± 28.19 |

| TLC (mL; % predicted) |

8563.9 ± 1358.9; 140.9 ± 28.19 |

| RV/TLC ratio (%) |

73.4 ± 7.84 |

| pO₂ (mmHg) |

60.7 ± 14.21 |

| pCO₂ (mmHg) |

51.1 ± 6.83 |

| pH (units) |

7.40 ± 0.06 |

| Ventilator Parameters |

|

| IPAP at baseline (cmH₂O) |

19.3 ± 5.0 |

| IPAP during exercise (cmH₂O) |

21.9 ± 5.7 |

| EPAP at baseline (cmH₂O) |

9.0 ± 2.7 |

| EPAP during exercise (cmH₂O) |

9.5 ± 3.1 |

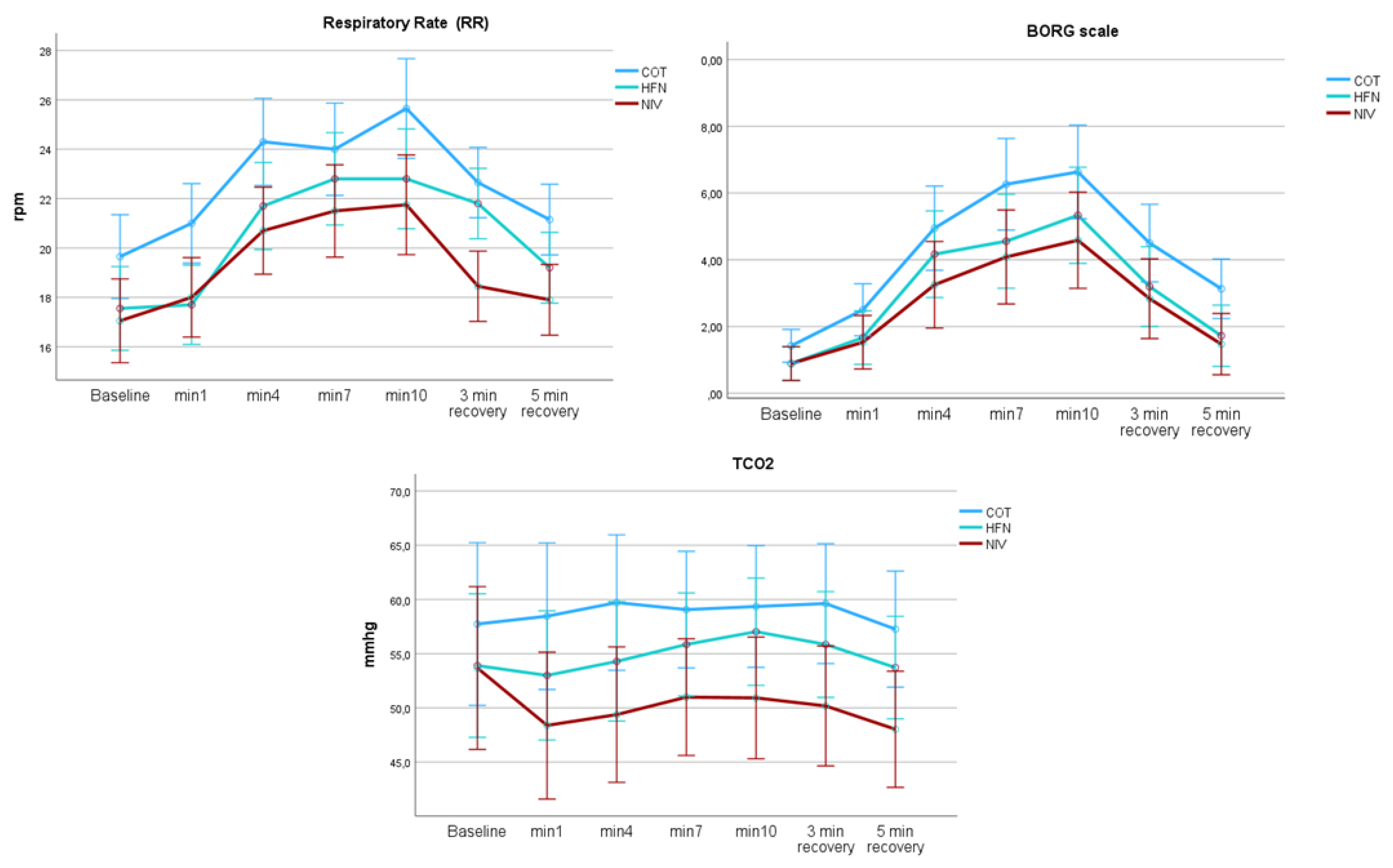

3.2. Comparative Study of Respiratory Variables

A comparative analysis of respiratory interventions revealed distinct physiological effects. NIV showed superior performance, with a greater reduction in respiratory rate (mean difference: 4.2 breaths/min), lower perceived exertion (Borg score decrease: 1.8 points), and a more pronounced reduction in tCO₂ (decrease: 5.3 mmHg) compared to both COT and HFT during exercise testing (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). HFT demonstrated intermediate efficacy between COT and NIV. These findings are illustrated in

Figure 1. A summary of intra- and inter-condition statistics is presented in

Table 2.

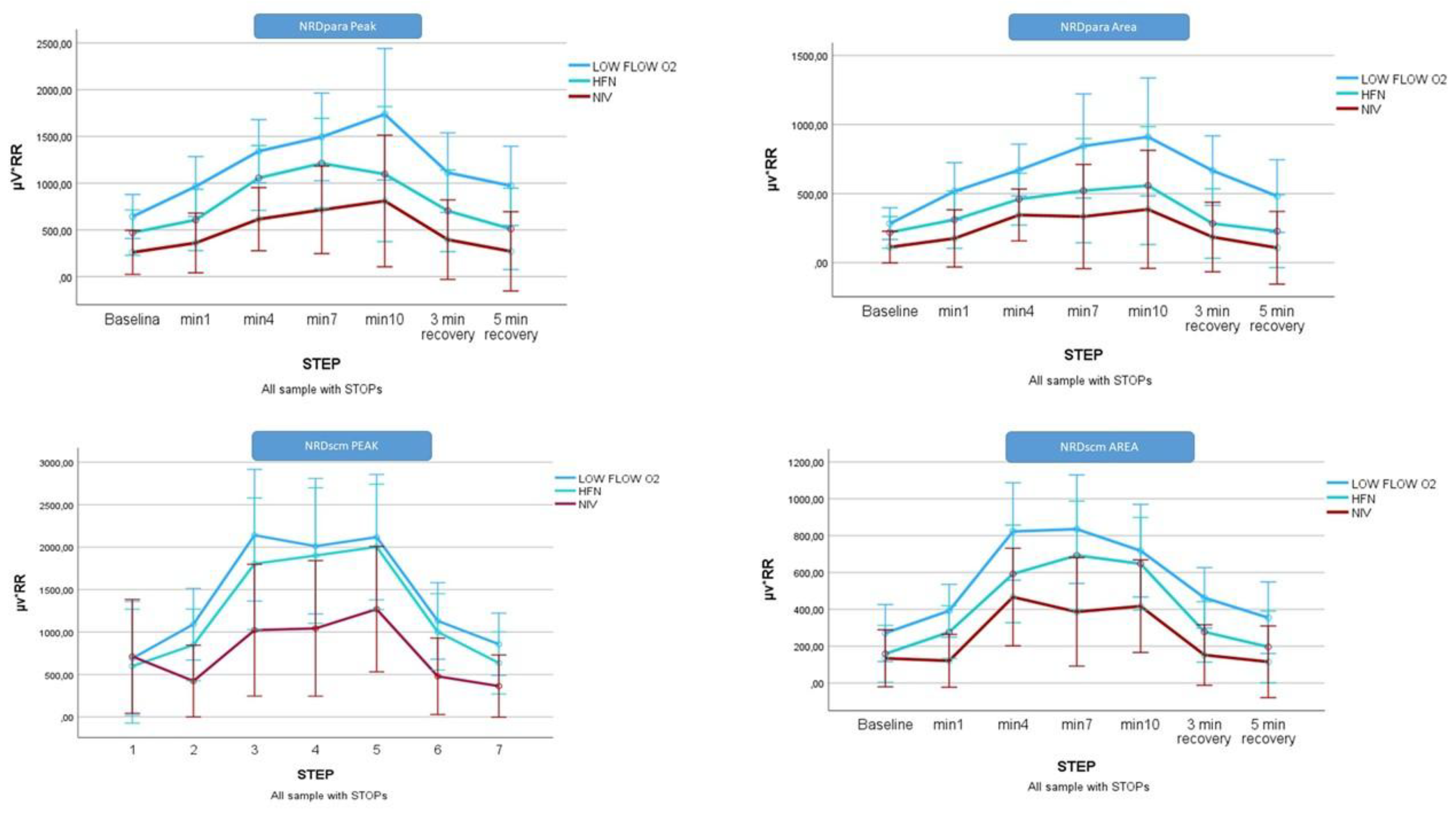

3.3. Comparative Study of Neuroventilatory Variables

During exercise, significant within-subject differences were observed in the degree of respiratory muscle activation. In the inter-condition analysis, NIV resulted in the greatest muscular unloading compared to COT, with HFT showing an intermediate effect. When analyzing the neural respiratory drive (expressed as µV × respiratory rate) across the three exercise conditions (COT, NIV, and HFT), a mixed repeated-measures ANOVA including the full cohort demonstrated significant differences. Specifically, peak EMGpara activity was lowest with NIV, indicating the most effective reduction in respiratory muscle load during exercise. However, the analysis of the EMG area (RMS area under the curve) for both the parasternal (EMGpara) and sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles showed no significant inter-condition differences, although significant within-subject changes were detected.

Table 2 also summarizes NRD findings for NRD EMGpara and EMGscm.

Table 3 reflects the average values of NRD for each condition

Table 2.

Statistical analysis for Respiratory and Neural respiratory variables.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis for Respiratory and Neural respiratory variables.

| Parameter |

F-statistic |

p-value |

Effect Size (ⴄ²) |

Power (β⁻¹) |

| Respiratory Rate (RR) |

|

|

|

|

| - Intrasubject |

12.000 |

p < 0.05 |

0.20 |

0.88 |

| - Intersubject |

6.074 |

p < 0.01 |

0.20 |

0.86 |

| Borg Scale |

|

|

|

|

| - Intrasubject |

26.081 |

p < 0.001 |

0.77 |

1.00 |

| - Intersubject |

4221.596 |

p < 0.001 |

0.76 |

1.00 |

| TcCO₂ (mmHg) |

|

|

|

|

| - Intrasubject |

1191.236 |

p < 0.001 |

0.96 |

1.00 |

| - Intersubject |

26.081 |

p = 0.1 |

0.10 |

0.43 |

| Parasternal peak EMG |

|

|

|

|

| Intrasubject |

25.953 |

p < 0.001 |

0.68 |

1 |

| Intersubject |

2.56 |

0.05 |

0.09 |

0.56 |

| Parasternal area EMG |

|

|

|

|

| Intrasubject |

15.212 |

p<0.001 |

0.61, |

0.99 |

| Intersubject |

2.523 |

p=0.08 |

0.1 |

0.48 |

| SCM peak EMG |

|

|

|

|

| Intrasubject |

6.53 |

0.08 |

0.2 |

0.67 |

| Intersubject |

2.57 |

0.1 |

0.05 |

0.35 |

| SCM area EMG |

|

|

|

|

| Intrasubject |

28.046 |

p<0.001 |

0.32 |

1 |

| Intersubject |

2.772. |

0.07 |

0.1 |

0.52 |

Table 3.

Mean neural respiratory Drive Variable Analysis Across Exercise Conditions.

Table 3.

Mean neural respiratory Drive Variable Analysis Across Exercise Conditions.

| Parameter |

Condition |

Mean ± SD |

95 % CI |

| Parasternal NRD in µV. (peak) |

COT |

1180 ± 200.1 |

781.68 to 1579.58 |

| NIV |

488.81 ± 199.09 |

89.80 to 887.70 |

| HFT |

807.80 ± 204.32 |

398.50 to 1217.15 |

| SCM NRD in µV (peak). |

COT |

1434.24 ± 265.17 |

903.30 to 1965.24 |

| NIV |

758.90 ± 265.17 |

227.80 to 1289.80 |

| HFT |

1256.10 ± 265.17 |

725.15 to 1787.10 |

Finally,

Figure 2 represents the analysis of the NRD variables for the whole cohort.

3.4. Subgroup Analysis: Exercise Non-Limited Cohort (Patients Who Did Not Stop Pedalling, n = 7)

Significant time- and conditions- related differences were for the peak NRD factor (µV × respiratory rate) in both muscle groups analysed, with effects observed both within and between subjects (Figure 3). Among the three ventilatory support strategies, NIV was associated with the greatest reduction in respiratory muscle effort during exercise. This was reflected in highly significant decreases in both peak and area NRD values for the EMGpara compared COT and HFT:

-

EMGpara NRD peak:

- ▪

Within-subject: F(6,14) = 8.970, p < 0.001, η² = 0.79, β-1 = 0.99

- ▪

Between-subject: F(2,18) = 9.116, p < 0.01, η² = 0.50, β-1 = 0.94

EMGscm NRD peak:

▪ Within-subject: F(6,33) = 23.142, p < 0.001, η² = 0.41, β-1 = 0.99

▪ Between-subject: F(2,33) = 4.760, p < 0.01, η² = 0.22, β-1 = 0.75

For the patients who did not stop, the differences did not reach statistical significance (data not shown).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that NIV significantly reduces NRD during exercise in patients with severe COPD when compared to HFT and COT. NRD, quantified as the product of respiratory rate and normalized parasternal electromyography (EMGpara%max), was 60% lower with NIV than with COT (488.81 µV vs. 1180.63 µV, p<0.05), with HFT showing intermediate effects (807.8 µV). These results are consistent with previous meta-analyses indicating the superiority of NIV over HFT in improving exercise tolerance and alleviating dyspnoea[

21,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. The physiological basis for this advantage lies in NIV’s ability to unload inspiratory muscles by counteracting intrinsic PEEP, reducing dynamic hyperinflation, and increasing tidal volume—mechanisms that are only modestly engaged by HFT, which primarily enhances oxygenation and comfort.

The limited impact of HFT on NRD likely reflects its inability to provide sufficient and consistent positive pressure under high ventilatory demand. Although HFT can generate a degree of airflow-dependent positive airway pressure (~4 cmH₂O at 40 L/min), this is typically inadequate to overcome the elevated inspiratory threshold load encountered during exercise in severe COPD[

25]. In contrast, NIV offers adjustable inspiratory pressures, effectively reducing inspiratory effort, as demonstrated by decreases in both EMGpara and EMGscm activity. These findings reinforce the concept that pressure support, rather than flow delivery alone, is essential for effective respiratory muscle unloading in patients with significant expiratory flow limitation[

44].

Patient characteristics likely influenced the observed efficacy of NIV. Participants presented with severe airflow limitation with forced expiratory volume in first second (FEV₁) of 19.78% predicted and marked hyperinflation (residual volume/total lung capacity 160%), making them particularly suitable for NIV-assisted training.

Another key contributor to NIV success was participants’ prior acclimatization to home NIV. This familiarity likely enhanced both tolerance and adherence, in contrast to NIV-naïve patients who frequently experience mask-related discomfort and patient-ventilator asynchrony, often resulting in early discontinuation[

45]. In our cohort, acclimatized patients achieved optimal synchrony, allowing sustained pressure delivery even during peak exercise, which likely contributed to improved alveolar ventilation and lower transcutaneous CO₂ levels.

The use of a high-performance ventilator, with rapid pressurization capabilities (rise time <50 ms), also played a pivotal role in matching the ventilator's response to patients’ inspiratory demands during exercise. Unlike older or less responsive devices[46], this technology minimized flow demand and ensured consistent patient-ventilator synchrony even under rapidly changing ventilatory loads. This likely contributed to the consistent achievement of the study’s target of at least 20% NRD reduction, a result that would be harder to obtain with suboptimal equipment.

Finally, individualized titration of inspiratory pressure was key to achieving physiological optimization. IPAP was adjusted prior to testing to ensure a ≥20% reduction in NRD during unloaded cycling, thereby tailoring support to each patient's needs[

14,46,47]. Real-time feedback from EMG allowed for fine-tuning of pressure support, maximizing inspiratory muscle unloading.

The observed 13% increase in endurance time with NIV is consistent with previous findings, such as those by Xie et al.[48], who reported a 59% improvement in dyspnoea-adjusted exercise capacity using comparable protocols. In contrast, the absence of significant benefits with HFT diverges from the metanalysis by Candia et al.[

25], who observed functional improvements in patients with milder COPD. This contrast underscores HFT’s potential utility in moderate disease stages, while reinforcing the specific advantage of NIV in patients with more severe airflow limitation and hyperinflation.

These findings must also be interpreted in light of the practical demands associated with implementing NIV in clinical settings. Titration of pressure levels and EMG setup required approximately 45 minutes per session and involved personnel with specialized expertise. This requirement poses a significant barrier in rural or resource-limited environments where access to both equipment and trained professionals may be limited. The development of automated pressure adjustment algorithms and simplified EMG monitoring techniques could play a key role in facilitating broader implementation. Additionally, cost considerations remain an important factor. Future research should focus on evaluating whether the higher upfront costs of NIV and EMG monitoring are offset by long-term healthcare savings, particularly through reductions in hospital admissions following rehabilitation.

This study has some limitations that warrant consideration. The relatively small sample size (n=20) constrains statistical power. Although the cohort size is comparable to previous single-centre physiological trials, it limits the generalizability of the findings to broader COPD populations. The extensive pre-transplant assessment can rule out the presence of comorbidities that confound the response to ventilatory support. However, it limits the generalisability of these results to older populations or those with other accompanying diseases. Furthermore, the inclusion of patients previously acclimatized to home NIV may have introduced a selection bias, potentially overestimating tolerance and benefit during exercise sessions. To minimize the potential impact of comorbidities on study outcomes, all participants underwent a comprehensive pre-transplant evaluation. To confirm the reproducibility and external validity of these results, larger multicentre studies involving more heterogeneous patient groups and varying levels of disease severity are essential.

Future research should focus on several key areas to build on these findings. First, the development of personalized ventilatory support algorithms that integrate real-time EMG and tidal volume data could enable automatic pressure adjustments during exercise, enhancing both precision and feasibility. Second, rigorous cost-benefit analyses comparing the long-term outcomes of NIV and HFT across healthcare systems with differing resource availability are needed to inform clinical and policy decisions. Third, the potential of hybrid protocols—such as sequential HFT-NIV strategies—should be investigated to determine whether they could offer an optimal balance between patient comfort and physiological efficacy, particularly in populations with variable tolerance or access to equipment.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that EMG titrated NIV significantly reduces NRD during exercise in patients with severe COPD, compared to HFT and COT. These benefits are particularly evident in patients previously acclimatized to NIV and with no other comorbidities. Our findings support the integration of individualized NIV strategies into pulmonary rehabilitation programs for advanced COPD.

Author Contributions

JSC, CLP, and MLT conceived and designed the study protocol, developed the analysis plan, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. AHV, MJG, MCB, and LGR contributed substantially to the setup and optimization of the signal processing protocols, conducted preliminary tests to refine the experimental procedures, performed all exercise trials, provided medical supervision during these sessions, contributed to the revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version. VVG provided essential infrastructure and logistical support for the execution of the study, contributed to the initial drafting of the manuscript, and participated in the critical revision and approval of the final version, enhancing its clarity and overall quality. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This research was supported by the Madrid Respiratory Society (Neumomadrid) and by an unrestricted grant from Menarini.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre under approval number 18/025. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre under approval number “18/025” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the biological nature of thesignals, and information related to inclusion in lung transplant list, data are not publicly available. Upon justified request, authors may share raw data of the flow/pressure/EMG and other biological variables tracings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families for their participation in this study. We also express our gratitude to the staff of the Lung Transplant Unit at Hospital 12 de Octubre for their invaluable support in patient care.

Conflicts of Interest

“The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”. JSC reports fees for educational activities and advisory boards for Philips and Resmed.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| COT |

Conventional Oxygen Therapy |

| NIV |

Non-Invasive Ventilation |

| HFT |

High-Flow Nasal Cannula Therapy (High-Flow Therapy) |

| NRD |

Neural Respiratory Drive |

| PEEPi |

Intrinsic End-Expiratory Positive Pressure |

| EMG |

Electromyography |

| EMGpara |

Parasternal Electromyography |

| EMGscm |

Sternocleidomastoid Electromyography |

| SCM |

Sternocleidomastoid Muscle |

| RIP |

Respiratory Inductance Plethysmography |

| SpO₂ |

Peripheral Oxygen Saturation |

| tcCO₂ |

Transcutaneous Carbon Dioxide |

| FEV₁ |

Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second |

| FVC |

Forced Vital Capacity |

| RV |

Residual Volume |

| TLC |

Total Lung Capacity |

| RV/TLC |

Residual Volume to Total Lung Capacity Ratio |

| IPAP |

Inspiratory Positive Airway Pressure |

| EPAP |

Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure |

| FiO₂ |

Fraction of Inspired Oxygen |

| MIP |

Maximal Inspiratory Pressure |

| RMS |

Root Mean Square |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| RR |

Respiratory Rate |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| ST mode |

Spontaneous/Timed Mode (ventilator setting) |

References

- Venkatesan, P. GOLD COPD report: 2025 update. Lancet Respir Med. 2025;13:e7-e8.

- O'Donnell DE, Revill SM, Webb KA. Dynamic hyperinflation and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:770-7. [CrossRef]

- Babb TG, Viggiano R, Hurley B, Staats B, Rodarte JR. Effect of mild-to-moderate airflow limitation on exercise capacity. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:223-30. [CrossRef]

- Duiverman ML, de Boer EW, van Eykern LA, et al. Respiratory muscle activity and dyspnea during exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;167:195-200. [CrossRef]

- Jolley C, Luo Y, Steier J, et al. Neural respiratory drive and symptoms that limit exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2015;385 Suppl 1:S51. [CrossRef]

- Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Gascon M, Sanchez A, Gallego B, Celli BR. Inspiratory capacity, dynamic hyperinflation, breathlessness, and exercise performance during the 6-minute-walk test in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1395-9. [CrossRef]

- Jolley CJ, Luo YM, Steier J, Rafferty GF, Polkey MI, Moxham J. Neural respiratory drive and breathlessness in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:355-64. [CrossRef]

- Babcock MA, Pegelow DF, Harms CA, Dempsey JA. Effects of respiratory muscle unloading on exercise-induced diaphragm fatigue. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:201-6. [CrossRef]

- Spahija J, de Marchie M, Albert M, et al. Patient-ventilator interaction during pressure support ventilation and neurally adjusted ventilatory assist. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:518-26. [CrossRef]

- Menadue C, Piper AJ, van 't Hul AJ, Wong KK. Non-invasive ventilation during exercise training for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD007714.

- Bonnevie T, Gravier FE. NIV Is not Adequate for High Intensity Endurance Exercise in COPD. 2020;9. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi L, Foglio K, Porta R, Baiardi R, Vitacca M, Ambrosino N. Lack of additional effect of adjunct of assisted ventilation to pulmonary rehabilitation in mild COPD patients. Respir Med. 2002;96:359-67. [CrossRef]

- Johnson JE, Gavin DJ, Adams-Dramiga S. Effects of training with heliox and noninvasive positive pressure ventilation on exercise ability in patients with severe COPD. Chest. 2002;122:464-72. [CrossRef]

- da Luz Goulart C, Caruso FR, Garcia de Araújo AS, et al. The Effect of Adding Noninvasive Ventilation to High-Intensity Exercise on Peripheral and Respiratory Muscle Oxygenation. Respir Care. 2023;68:320-9.

- Hannink JD, van Hees HW, Dekhuijzen PN, van Helvoort HA, Heijdra YF. Non-invasive ventilation abolishes the IL-6 response to exercise in muscle-wasted COPD patients: a pilot study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24:136-43.

- Lei Y, He J, Hu F, et al. Sequential inspiratory muscle exercise-noninvasive positive pressure ventilation alleviates oxidative stress in COPD by mediating SOCS5/JAK2/STAT3 pathway. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23:385. [CrossRef]

- Reuveny R, Ben-Dov I, Gaides M, Reichert N. Ventilatory support during training improves training benefit in severe chronic airway obstruction. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 2005;7:151-5.

- Duiverman ML, Wempe JB, Bladder G, et al. Nocturnal non-invasive ventilation in addition to rehabilitation in hypercapnic patients with COPD. Thorax. 2008;63:1052-7. [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino N, Cigni P. Non invasive ventilation as an additional tool for exercise training. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2015;10:14.

- Furlanetto KC, Pitta F. Oxygen therapy devices and portable ventilators for improved physical activity in daily life in patients with chronic respiratory disease. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2017;14:103-15. [CrossRef]

- Marrara KT, Di Lorenzo VAP, Jaenisch RB, et al. Noninvasive Ventilation as an Important Adjunct to an Exercise Training Program in Subjects With Moderate to Severe COPD. Respir Care. 2018;63:1388-98. [CrossRef]

- Elshof J, Duiverman ML. Clinical Evidence of Nasal High-Flow Therapy in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. Respiration. 2020;99:140-53. [CrossRef]

- Candia C, Lombardi C, Merola C, et al. The Role of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy in Exercise Testing and Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A Review of the Current Literature. J Clin Med. 2023;13. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Xu L, Li S, et al. Efficacy of respiratory support therapies during pulmonary rehabilitation exercise training in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2024;22:389. [CrossRef]

- Florez Solarana P, Lalmolda Puyol C, Corral Blanco M, et al. Automatic detection and monitoring of expiratory flow limitation in non-invasive ventilation. ERJ Open Research.10:64.

- Ramsook AH, Mitchell RA, Bell T, et al. Is parasternal intercostal EMG an accurate surrogate of respiratory neural drive and biomarker of dyspnea during cycle exercise testing? Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2017;242:40-4. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes S, Chowdhury YS. Fraction of Inspired Oxygen. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Lalmolda C, Flórez P, Corral M, et al. Does the Efficacy of High Intensity Ventilation in Stable COPD Depend on the Ventilator Model? A Bench-to-Bedside Study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:155-64.

- Williams S, Porter M, Westbrook J, Rafferty GF, MacBean V. The influence of posture on parasternal intercostal muscle activity in healthy young adults. Physiological measurement. 2019;40:01NT3. [CrossRef]

- Wu W, Guan L, Li X, et al. Correlation and compatibility between surface respiratory electromyography and transesophageal diaphragmatic electromyography measurements during treadmill exercise in stable patients with COPD. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2017;12:3273--80. [CrossRef]

- Sayas Catalán J, Lalmolda C, Hernández-Voth A, et al. Thoracoabdominal Asynchrony in Very Severe COPD: Clinical and Functional Correlates During Exercise. Arch Bronconeumol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Jolley CJ, Luo YM, Steier J, et al. Neural respiratory drive in healthy subjects and in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:289-97. [CrossRef]

- Lin L, Guan L, Wu W, Chen R. Correlation of surface respiratory electromyography with esophageal diaphragm electromyography. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2019;259:45-52. [CrossRef]

- Hudson AL, Butler JE. Assessment of 'neural respiratory drive' from the parasternal intercostal muscles. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2018;252-253:16-7. [CrossRef]

- Alex JvtH, Alex JvtH, Alex Van 't H, et al. The acute effects of noninvasive ventilatory support during exercise on exercise endurance and dyspnea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation. 2002.

- Chen X, Xu L, Li S, Yet al. Efficacy of respiratory support therapies during pulmonary rehabilitation exercise training in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC medicine. 2024;22:389. [CrossRef]

- Costes F, Agresti A, Court-Fortune I, Roche F, Vergnon JM, Barthélémy JC. Noninvasive ventilation during exercise training improves exercise tolerance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23:307-13. [CrossRef]

- Deniz S, Tuncel Ş, Gürgün A, Elmas F. Adding Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation to Supplemental Oxygen During Exercise Training in Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Randomized Controlled Study. Thorac Res Pract. 2023;24:262-9. [CrossRef]

- François M, François M, François M, et al. Pressure support reduces inspiratory effort and dyspnea during exercise in chronic airflow obstruction. 1995.

- Köhnlein T, Schönheit-Kenn U, Winterkamp S, Welte T, Kenn K. Noninvasive ventilation in pulmonary rehabilitation of COPD patients. Respir Med. 2009;103:1329-36. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu K, He Y, Ding H. Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation versus High-Flow Nasal Cannula for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: An Updated Narrative Review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2024;19:2415-20. [CrossRef]

- Bonnevie T, Gravier FE, Fresnel E, Kerfourn A, Medrinal C, Prieur G, et al. NIV Is not Adequate for High Intensity Endurance Exercise in COPD. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [CrossRef]

- Tristan B, Tristan B, Francis-Edouard G, Francis-Edouard G, Emeline F, Emeline F, et al. NIV Is not Adequate for High Intensity Endurance Exercise in COPD. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020.

- Anekwe D, de Marchie M, Spahija J. Effects of Pressure Support Ventilation May Be Lost at High Exercise Intensities in People with COPD. Copd. 2017;14:284-92. [CrossRef]

- Xie S, Li X, Liu Y, Huang J, Yang F. Effect of home noninvasive positive pressure ventilation combined with pulmonary rehabilitation on dyspnea severity and quality of life in patients with severe stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease combined with chronic type II respiratory failure: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulm Med. 2025;25:185. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).