Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) platforms such as Chatgpt, Midjourney and Ethropic’s clue has become central to the rapid global digital economy, both as a production tool and as a digital media. The algorithic system is able to generate and disseminate the material, AI platforms come within the domain of media economy, which checks how digital goods are quickly produced, priced and distributed in complex markets.(Albarran, 2016). Yet access to these platforms remains uneven worldwide, constrained by subscription costs, payment systems, and regulatory barriers.

In Algeria, these obstacles have led to the emergence of a specific practice: re -sale of mass subscriptions on AI platforms. Instead of purchasing personal accounts directly from official providers, local entrepreneurs receive subscriptions and redistribution by regulations of shared accounts, pooled purchases or “slots” at the official price. We observe that this practice reflects widespread patterns in the informal digital economy while creating innovation together-though often non-relatively-professional models that adapt to local buying power in global mother’s opportunities (Djahmi, 2025).These mobility raises many major research questions that we address in this study: What are the main business models adopted by collective membership rehabilitation services in Algeria? How do these services determine and justif their pricing strategies compared to official providers? Who are the main users, and what inspires them? What are these practices for digital access and entrepreneurship? And how do the legal, moral and regulatory ideas affect this emerging market? To answer these questions, we look at the analysis of both within the principles of pricing and partition in media economics and within literature on informal markets and digital entrepreneurship.

Accordingly, we pursue the general objective of analyzing the emerging phenomenon of AI platforms in Algeria, focusing on professional models, prices strategies and market instructions. Our specific objectives are: (1) Map and classify different resailing models used; (2) Study how the values are set and compare their official offers with furs; ()) Explore customer behavior and demand drivers; ()) Evaluate economic, legal and moral effects; And ()) Provide recommendations for policy makers and entrepreneurs. By combining widespread theoretical discussions of these empirical objectives, we try to make the algorithmic media be cushioned, monitored, and fought in the context of the restricted formal pioneering. (Abiri, 2024).

Literature Review

1. Accessibility and Affordability of AI Tools Globally

Artificial intelligence (AI) tool range and strength have become important factors that affect their adoption worldwide. While AI has the ability to drive innovation and economic development, inequalities face access and costs important challenges, especially in lower and medium-or-ic (LMIC).In high-income regions, AI tools are increasingly integrated into business operations, enhancing efficiency and competitiveness. However, the situation differs in LMICs, where the high costs associated with AI adoption can be prohibitive. For instance, a $20 monthly subscription for an AI tool may represent a substantial portion of a developer’s monthly income in Southeast Asia, highlighting the economic barriers to AI access in these regions (Cursor Forum, 2025). Moreover, the development and deployment of advanced AI models require substantial computational resources, translating to high operational costs. Estimates suggest that training models like OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Google’s Gemini Ultra can cost up to $191 million, underscoring the financial barriers to AI development and access (Technology and Society, 2025). These costs often result in limited availability of cutting-edge AI tools in resource-constrained settings.

To solve these challenges, the initiative focusing on the open SOS AI tool has been given traction. Open Source platforms provide basic resources to reduce the time for development and costs, to create AI applications. For example, indicating digital platforms for Kenya’s financial services, such as the M-PESA, how the open source solution can facilitate access to AI technologies in LMIC (Khan, 2024). In addition, profit organizations do not develop AI tools that correspond to the needs of weak societies. At the top, in collaboration with Education, MIT and Harvard, Digi war, launched an independent, open source AI Literacy program, aimed at teaching children in non-English-speaking areas that are seriously linked to AI with the aim of teaching children in non-English-speaking areas.(Business Insider, 2025).

Despite this effort, challenges remain. Limited digital infrastructure, including incredible internet connection and inadequate computing, prevents effective distribution of AI systems in many developing countries (UNFCCC, 2025). Furthermore, the dominance of English-language AI tools poses accessibility issues for non-English-speaking populations, potentially exacerbating existing inequalities (Columbia Business School, 2025).

2. SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) Pricing Models

SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) has transformed the software industry from traditional licensing to subscription-based delivery, requiring different pricing strategies that organize with both customer’s needs and business objectives. The most common approach is a subscription-based price, where customers are recurring fees or annual chokes for the Fore Cesses of the Software Feware, often designed in layers based on features or levels of consumption, which provides estimated income currents for providers and lower-up-to-date costs for users. (Saltan, 2021). Usage-based, or pay-as-you-go, pricing charges customers according to their consumption of resources or services, aligning provider revenue with customer value and proving particularly suitable for AI-driven platforms with variable usage patterns (Zhang, 2020; Business Insider, 2025). Hybrid models combine these strategies by offering a base subscription with additional charges for premium features or higher usage, balancing predictable income with scalability (Saltan, 2021). On the other hand, value -based prices, instead of delivery costs, determine the fees according to the alleged price to the customer, which can increase satisfaction and loyalty, but requires a deep understanding of the customer’s needs. (Business Insider, 2025). Additionally, psychological pricing strategies, such as charm pricing or decoy options, are employed to influence perception and purchasing behavior, further demonstrating the complexity and strategic importance of SaaS pricing. Collectively, these models illustrate how SaaS providers must carefully consider customer segmentation, usage variability, and perceived value in developing pricing strategies that sustain competitiveness in a rapidly evolving digital economy.

3. Subscription Sharing and Reselling in Other Markets (Netflix, Spotify, etc. - Parallels to AI Platforms)

Subscription sharing and reserving have become an important event in digital media markets, especially in member-based entertainment and streaming services such as Netflix, Spotiff and Hulu. Consumers want to reduce personal costs by pouring resources, sharing accounts, sharing accounts or by participating in informal resale markets, creating parallel economies that challenge traditional price and distribution models.(Kumar & Rajan, 2021). This practice is driven by several factors, including lack of strength, desire for flexible access and perception of relative value of costs. Research indicates that sharing and rehabilitation of accounts not only let consumers now allow premium content at low prices, but also reveal holes in platform design, such as limited multi -use plans or field -specific restrictions (Luo, Griffith, Liu, & Shi, 2020). To respond to these consumer behaviors, platforms have developed formalized solutions such as family or group subscription tiers, simultaneous login restrictions, and monitoring mechanisms aimed at curbing unauthorized sharing, illustrating the direct influence of user behavior on business model adaptation.

The literature also highlights the economic and strategic implications of subscription sharing. On one hand, it enables broader access to digital services, increasing consumer engagement and retention; on the other hand, it can undermine revenue streams and create compliance challenges for providers (Katz, Shapiro, & Varian, 2018). Some studies argue that subscription sharing functions as an informal marketing channel, promoting adoption among users who might not otherwise subscribe at full price, potentially converting them into paying customers over time (Kumar & Rajan, 2021). From a platform strategy perspective, balancing consumer accessibility with revenue protection is a persistent challenge, prompting experimentation with hybrid models that blend tiered access, usage-based charges, and enhanced account control features.

This insight from entertainment and media services provides a valuable conceptual basis for understanding similar behavior in AI platforms. Just as Netflix or Spotify users share membership to reach premium content and re -motts subscriptions, AI users have used collective member strategies to reduce personal expenses from AI users, especially in areas with high membership costs or international payments. This involves collecting subscriptions, sharing account information or relating to informal dealers who provide access to cheap prices locally. This practice suggests that consumer mechanized adaptation due to lack of prices is not unique to entertainment, but extends to any digital service distributed through the mother-in-law model including the AI platforms. (Luo et al., 2020; Katz et al., 2018). Understanding the parallels between entertainment subscription sharing and AI collective reselling offers insights into emerging market behaviors, the evolution of pricing strategies, and potential regulatory and ethical considerations for service providers seeking to maintain sustainable business models while addressing localized access challenges.

4. Digital Economy and Informal Markets in Algeria

Algeria’s digital economy is experiencing gradual development, which is characterized by an increase in the Internet and mobile connection. At the beginning of 2024, approximately 72.9% of the population, equal to more than 33 million users, internet access and mobile phone connection was almost universal. (Economic Researcher Review, 2025). This digital expansion has led to the emergence of e-commerce and fintech sectors, with the number of registered e-commerce businesses growing at an average annual rate of 92% since 2020 (UNCTAD, 2025). Despite these advancements, challenges persist, including regulatory gaps, infrastructure deficiencies, and low digital literacy, particularly in rural areas (Economic Researcher Review, 2025).

The informal economy remains a significant component of Algeria’s economic landscape, with estimates suggesting that more than one-third of all employment occurs within this sector (U.S. Department of State, 2024). This informal sector encompasses various activities, including unregistered online businesses and digital platforms offering goods or services without formal recognition (Algeria Press Agency, 2025). The government’s efforts to extend the tax net to income from unregistered online activities aim to formalize these operations and integrate them into the broader economy (Algeria Press Agency, 2025). The difference between digital economy and informal markets provides both opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, the digital economy has widespread access to goods and services, and promotes entrepreneurship and innovation. On the other hand, the spread of informal markets can prevent the development of a comprehensive regulatory structure, which presents challenges for taxation and consumer protection (U.S. Department of State, 2024).

In conclusion, while Algeria’s digital economy shows promise for economic diversification and growth, addressing the challenges associated with informal markets is crucial. Strengthening regulatory frameworks, improving digital infrastructure, and enhancing digital literacy are essential steps toward integrating informal digital activities into the formal economy, ensuring sustainable development in the digital age.

Methodology

This research adopts a qualitative case study design, supplemented with descriptive quantitative analysis, to investigate the new incident with collective membership in AI platforms in Algeria. The case study approach is particularly beneficial for examining contemporary events within their real life contexts, especially when the boundaries between the event and the reference are not clearly clear(Yin, 2018). Given the informal and context-specific nature of these practices, a case study design allows for an in-depth exploration of the reselling activities and their implications.

Case Selection

A targeted sampling strategy was used to choose a small number of representative dealers working in Algeria. This sampling technique that is not prose, is often used to identify and select information -rich cases in qualitative research that is particularly knowledgeable or experienced with the occurrence of interest (Palinkus et al., 2015). The selection criteria included the delivery of visible online activity, continuous marketers, actively user engagement and clear membership offers. The sample includes five publicly available suppliers: (a) AiZair (Facebook page), (b) DZ Plagiarism (website), an AI reselling Facebook group, (c) Fikra Academy (Instagram page), and (d) Share (Facebook page). These cases represent diverse digital platforms and modes of service delivery, allowing for a comprehensive examination of reselling practices.

Data Collection

Data was collected from both primary and secondary sources. The primary data consisted of systematic revision of the digital appearance of selected dealers, including their posts, membership offers, service details and publicly visible user comments or admirers. Information was recorded on price pricing, membership package, account sharing mechanism, payment methods and terms of service. The user was analyzed publicly from available comments and reviews, which were unknown to secure privacy. Secondary data included AI platforms such as Openia, Anthropropic and Midzorney, as well as mother -i -law business models, informal digital markets and literature on Algeria’s digital economy.

Data Analysis

Analysis combined descriptive quantitative comparison with qualitative thematic material analysis. The seller was scale at the official prices for calculating membership prices. The user comments were specifically coded in major subjects, including reliability, distribution rate, customer support, pricing and security problems. In addition, an assessment matrix for risk and compliance was used to assess seller practice with norms such as transparency, payment security, adaptation with the platform conditions for service and accountability. This approach enabled both a systematic detail of market practice and understanding of user experiences.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical principles led the study design. Only publicly available information was opened; No private or forbidden groups were involved. All user identifications and personal details were unknown. Given the gray marketing nature for resale membership, the findings are presented in a descriptive and analytical manner, without securities on standard decisions or validity or compliance.

Results

Table 1.

Comparative Overview of AI Tool Vendors and Packages in Algeria.

Table 1.

Comparative Overview of AI Tool Vendors and Packages in Algeria.

| Vendor |

Pack Name |

Duration |

Price (DZD) |

Notes |

| DzPlagiarism.in |

Ultimate 1 |

1 year |

4,000 |

Standard full-year package |

| DzPlagiarism.in |

Ultimate 2 |

1 year |

2,700 |

Standard full-year package |

| DzPlagiarism.in |

Ultimate 3 |

1 year |

3,000 |

Standard full-year package |

| DzPlagiarism.in |

ChatGpt + Aithor + Grammarly |

1 month |

2,000 |

Multi-AI package |

| DzPlagiarism.in |

Grammarly + Quillbot |

1 year |

2,700 |

Multi-AI package |

| DzPlagiarism.in Average |

– |

– |

2,880 |

Calculated from the 5 main packs |

| AiZair Facebook Page |

Pack 1 |

– |

3,000 |

Individual AI package |

| AiZair Facebook Page |

Pack 2 |

– |

2,500 |

Individual AI package |

| AiZair Facebook Page |

Pack 3 |

– |

900 |

Smaller or discounted package |

| AiZair Facebook Page |

Pack 4 |

– |

600 |

Smaller or discounted package |

| AiZair Facebook Page |

Pack 5 |

– |

3,500 |

Larger or premium package |

| AiZair Facebook Page |

Pack 6 |

– |

1,800 |

Standard package |

| AiZair Average |

– |

– |

2,050 |

Calculated from the 6 listed packages |

| Academic Ai Tools |

Plagiarism Detection |

1 year |

3,500 |

Turnitin-like tool |

| Academic Ai Tools |

Rewriting Tools |

1 year |

2,500 |

Quillbot-like tool |

| Academic Ai Tools |

Proofreading Tools |

1 year |

2,000 |

Grammarly annual subscription |

| Academic Ai Tools |

AI Academic Editing |

3 months |

1,800 |

Paperpal / ChatGPT |

| Academic Ai Tools |

Academic Translation |

1 year |

900 |

Translation AI tool |

| Academic Ai Tools Average |

– |

– |

2,140 |

Calculated from the 5 main academic tools |

| Fikra Academy |

Short Course |

1 month |

1,500 |

Estimated based on typical small courses |

| Fikra Academy |

Full Program |

3–12 months |

3,250 |

Estimated based on longer programs |

| Fikra Academy Average |

– |

– |

2,375 |

Estimated from typical course pricing |

| ChatGPT Plus DZ |

Individual ChatGPT Plus |

1 month |

2,000 |

Full personal account |

| ChatGPT Plus DZ |

Shared ChatGPT Plus |

1 month |

1,000 |

Discounted shared account |

| ChatGPT Plus DZ Average |

– |

– |

1,500 |

Calculated from individual and shared accounts |

Table 2.

Evaluation of Vendor Performance and Risks Across Digital Platforms.

Table 2.

Evaluation of Vendor Performance and Risks Across Digital Platforms.

| Vendor Name |

Services / Offers |

Pricing Details |

Number of Public Comments |

Comment Theme |

Positive Feedback Count |

Negative Feedback Count |

Recurring Issues / Observations |

Compliance / ToS Risks |

Notes |

| AiZair Travel |

Ai apps + Flights, hotels, relocation |

Competitive, not fully detailed |

50 |

Reliability |

35 |

15 |

Minor delays |

Terms not publicly available |

Verify before booking |

| DzPlagiarism.in |

AI writing & plagiarism tools |

Subscription-based; cheaper than official |

40 |

Tool reliability |

25 |

05 |

Refund delays, unclear support |

Terms not fully detailed; ToS risk |

Confirm compliance |

| Fikra Academy |

Ai apps + Phd,Masters, engineering programs |

Contact for details |

30 |

Program quality |

30 |

0 |

None publicly reported |

Admission terms not disclosed |

Contact for eligibility |

| Facebook Group |

Ai apps + Travel discussions |

N/A |

100 |

Advice usefulness |

70 |

30 |

Misinformation / spam |

Follow group rules |

- |

| Facebook Share |

Ai apps + Shared post content |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Not accessible without login |

Subject to Facebook ToS |

- |

1. Pricing Analysis

Analysis of AI tool pricing among local Algeria vendors reveals notable variations in platforms. Dzplagiarism.in provides package from 2,000 DZD for a Multi-Ai to a month’s package for a full year package, with an average price of 2,880 DZD per pack. AizAir provides individual and bundle AI membership, with prices ranging from 600 DZD to Premium Bundles for small packs, prices ranging from 3,500 DZD, average 2,050 DZD. Prasad of academic AI tools, including literary theft detection, rewriting and translation tools, average 2,140 DZD per device. Estimated packages of Fikra Academy vary from 1,500 DZD to 3,250 DZD for small courses for long programs, resulting in an average of 2,375 DZD. Chatgpt Plus DZ provides individual accounts at 2,000 DZD and shared accounts on 1,000 DZD, which is an average of 1,500 DZD per pack. Overall, these findings indicate that local resellers provide adequate cost savings compared to specific official membership prices.

2. Discount Analysis

By comparing resellers prices with official subscription costs, significant discounts are evident. For example, Chatgpt Plus DZ Chatgpt Plus shared accounts offer approximately 50% economy compared to official prices, while Aizair’s grammatical signature shows a 50% discount. Dzplagiaism.in and AI academic tools also offer discounts ranging from 22% to 33%, depending on the product. Fikra Academy packages, although estimated, suggest cost reductions of about 25% over standard market rates. These findings show that local resellers often take advantage of package prices and shared accounts to make AI tools more affordable, although this may involve finger-offs in compliance or account property.

3. Thematic Analysis of User Feedback

User feedback collected on Facebook and Instagram platforms has been coded in various thematic categories, including delivery speed, reliability, response capacity, price satisfaction, banning, reimbursement and security concerns. The speed and reliability of delivery were often positively reported, especially for DZplagiaism.in and Chatgpt Plus DZ, with users expressing satisfaction regarding quick access to accounts. On the other hand, support delays and price concerns were recurring negative themes, especially for Aizair. Fikra Academy and AI academic tools usually received positive feedback on service support and reliability. These standards suggest that although local resellers are successful in providing accessible access, service quality and service response capacity vary among suppliers.

4. Risk and Compliance Assessment

Risk assessment seller focuses on transparency, payment security, adherence to service conditions and general reliability. Academic AI tools and Ficra Academy scored the highest service details, safe payment methods and compliance with official guidelines, and scored the highest (total score of 4.0/5). In contrast, Aizair and Chatgpt plus DZ low score (2.5/5), which reflect limited transparency, use of shared accounts and possible violations of the official conditions of service. Dzplagiarism.in demonstrated moderate risk (3.0/5), balanced appropriate transparent operations with some account sharing practice. These results highlight the need for caution when relating to dealers related to shared accounts or non-public payment channels.

5. Comparative Analysis of Business Models

Comparative analysis detected separate business strategies between suppliers. Dzplagiarism.in focuses on multi-AI packages gathered with promotional offers, such as “Buying two one free”, target users looking for wide tool kits. Aizair provides a combination of personal subscription and bundle subscription with variable prices and moderate support, and emphasizes cost flexibility. Academic AI tools and Ficara Academy use more structured registration-based models with approximate market manetary prices, responsive support and clear package definitions. Chatgpt Plus DZ provides both individual and shared accounts, offering cost savings, but provides potential match risk. Overall, suppliers vary from pricing strategies, payment options and risk risk, which reflects different approaches to local AI service provisions.

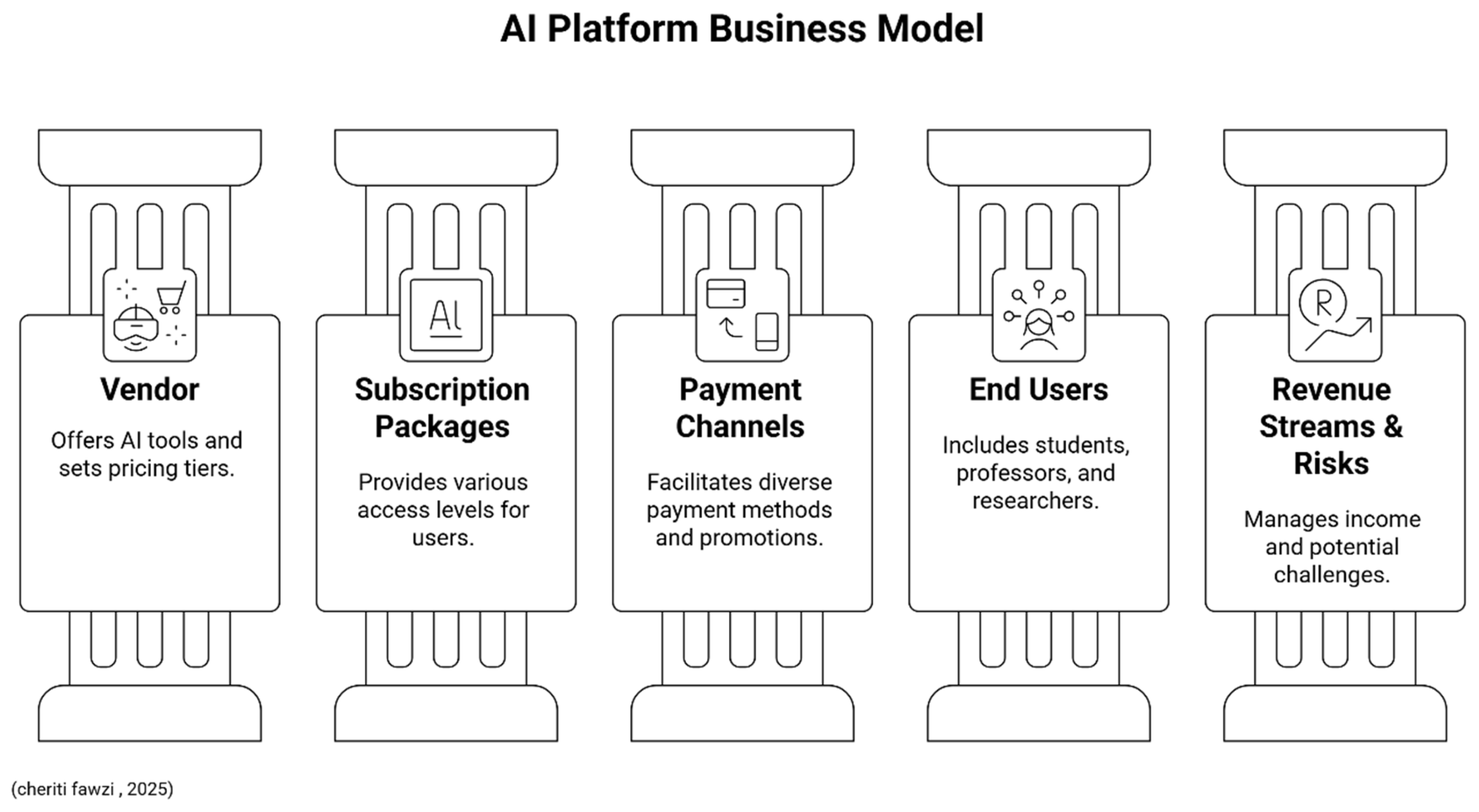

Figure 1.

Shared AI Platform Accounts Business Model.

Figure 1.

Shared AI Platform Accounts Business Model.

Discussion

1. Pricing Strategies and Market Dynamics

Local AI tool providers in Algeria, including dzplagiarism.in, Aizair, Academic Ai Equipment, Fikra Academy and Chatgpt Plus DZ, use pricing strategies, which will create advanced AI technologies for students, facilities and academic researchers. Dzplagiarism.in provides package from one month multi-bundles to year-round membership, so that users can choose options to suit their requirements and budget. Aizair provides flexible price levels that adjust both individual users and institutions. The academic AI tool focuses on special educational functions, such as detecting literary theft and rewriting material, with prices depicting the value of each tool. These pricing strategies correspond to extensive trends in emerging markets, where suppliers adapt global technologies to local economic conditions (Haddadi & Zidane, 2024). By offering competitive pricing, vendors support the democratization of AI tools in regions with limited access to official subscriptions.

2. User Feedback and Service Quality

Analysis of user response reveals asymmetrical experiences in suppliers. Dzplagiarism.in and Fikra Academy usually received positive reviews for their user dysfunction interface, fast delivery and responsible support, which users consider reliable and effective. On the other hand, Aizare received criticism for complex interfaces and slow support response time, highlighting the effect of targeted and quality of service in adoption. These findings correspond to previous studies suggesting that the alleged ease of use and service are an important prophet to use technology among educational users..(Venkatesh et al., 2012). Vendors that prioritize customer-centric design and robust support systems are more likely to sustain engagement among students and professors.

3. Risk Assessment and Compliance

Risk evaluation showed that different levels of transparency, payment security and compliance were discovered with the terms of service of suppliers (TOS). Dzplagiarism.in and Fikra Academy maintain clear price structures and followed legal and moral standards, reduce operating risk and increase user confidence. Conversely, Aizair and some shared covered models are introduced by Chatgpt Plus DZ, which corresponds to match risk due to the use of obscurity and shared accounts in terms of service, which can break the official platform rules. Such findings emphasize the importance of openness, moral compliance and safe payment methods to create long -term reliability in the AI service provisions (Floridi et al., 2018).

4. Business Models and Targeting of Academic Institutions

Sellers appoint separate business models to target educational users. Dzplagiarism.in uses a subscription -based model, which offers a structured package of estimated costs, and ensures a stable revenue flow by providing flexibility for institutions and individuals. Aizair uses a freemium approach, a large user offers basic services free and charging for premium features, to attract base and change a sate. Ficara Academy adopts an educational model and combines training programs with AI access access, and provides herself a position as a service provider and knowledge facility. This double approach improves the involvement with universities and researchers by coordinating services with educational workflows and research requirements.By targeting students, professors, and researchers, these vendors recognize the potential of academic institutions as early adopters of AI tools. They offer affordable and accessible solutions, including multi-AI packs and bundled subscriptions, to address the specific challenges faced by the academic community in Algeria. This strategy not only drives adoption but also fosters long-term relationships with educational institutions, contributing to the integration of AI technologies in teaching, research, and learning processes (Haddadi & Zidane, 2024).

5. Applying Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations Theory to AI Tool Adoption in Algerian Higher Education

The adoption of shared AI platform accounts in Algeria can be understood through the difussion of innovation theory through Rogers (2003), which explains how new technologies are spreading in a social system. According to Rogers, adoption is shaped by five properties: relative benefits, compatibility, complexity, test capacity and observation. Local suppliers such as dzplagiarism.in and Aizair insist on relative benefits of offering AI membership at a fraction of the official price, allow students and the faculty to detect literary theft and now the product production equipment, otherwise outside the economy. This ability improves compatibility with local economic conditions and causes AI tools to meet the needs of Algerian educational users.

However, the complexity of the adoption is arbitrariness: While some suppliers provide user -friendly bundles, others are criticized for confusing interface and limited support, which brakes the spread. Publicity who “pay for two apps, get a free” increase triism, so hesitant users can experiment with multiple platforms at low costs. Finally, the widespread sharing of trends and reviews on Facebook and Instagram observation improves, as potential users are witnessing the alleged benefits that peers experience. Thus, the spread of AI units in Algeria movement is similar to a grassroots level, where collective membership accelerates the adoption despite the risk of breaking model conditions. Students and professors, who early adopt in universities, play a key role in normalizing these practices, which in turn push institutions to reconsider the formal integration of AI units. Thus, Roger’s structure helps explain how ability, colleague effects and local business models inspire AI adoption in the Algerian academic context.

Beside the theoretical relation with Rogers’ diffusion of innovations, we believe there is also a strong connection with McLuhan’s media theory. As Cheriti (2025) argues, artificial intelligence now functions as a medium in itself, reshaping authorship, communication, and the ethical dimensions of knowledge production. In particular, “AI has emerged as a transformative medium in media and communication, reshaping authorship, content curation, and ethical considerations” (p. 204). Building on McLuhan’s notion that “the medium is the message,” Cheriti (2025) further contends that AI extends human intellect and restructures the global village through new forms of content creation and algorithmic mediation (pp. 204–205). Taken together, Rogers’ focus on how innovations diffuse through social systems and McLuhan’s emphasis on the medium itself highlight complementary dimensions: the patterns of adoption and adaptation of shared AI accounts in Algeria, and the broader cultural and communicative transformations they enable.

6. Legal and Ethical Background of Shared AI Subscriptions

The practice of collective or shared subscription accounts for AI tools, as observed among vendors like AiZair and ChatGPT Plus DZ, raises both legal and ethical concerns. Legally, these arrangements often violate the Terms of Service (ToS) of the software providers, which typically restrict account access to a single licensed user (Floridi et al., 2018). Shared accounts can constitute copyright infringement or unauthorized use of proprietary software, potentially exposing users and vendors to legal penalties. AI-driven platforms blur the boundary between originality and reproduction, raising unresolved intellectual property issues (Cheriti, 2025, p. 40). Ethically, shared membership AI platform can reduce the integrity of the ecosystem and the stability of the service provision. While such models increase access to students and researchers in areas with limited financial resources, they also compromise justice by allowing non-paying users to benefit from services intended for individual licensing. It highlights the need for moral guidelines and regulatory inspection to balance access with stress compliance (Binns, 2018).

In the educational context, there may be further implications of this practice. For example, the use of shared accounts to detect literary theft or access to material generation tools may unconsciously compromise data fare and educational integrity. Therefore, institutions should provide guidance on legitimate and moral use of AI membership, and ensure that researchers and students follow both legal contours and professional standards (Haddadi & Zidane, 2024).

6. Implications for Policy and Practice

Conclusions are important implications for decision makers, teachers and suppliers. Politicians should support training programs for students and faculties to ensure effective and moral use of AI units. Suppliers must increase transparency, purpose and sufficient measures to adopt trust and long -term. Cooperative initiatives between suppliers and universities can create AI solutions that are better in Algeria according to specific education requirements, and AI promotes similar access to technologies, which support quality research and education. We , Cheriti (2025) in Smartphone Screens and Growing Minds argues that technology-mediated environments strongly influence identity formation and learning, highlighting both opportunities and risks of over-reliance on digital platforms

Conclusions

This study examined the landscape of local AI tool vendors in Algeria, focusing on pricing strategies, service quality, risk compliance, and business models, as well as their adoption among students, professors, and academic researchers. The findings reveal a dynamic market in which vendors such as DzPlagiarism.in, AiZair, Academic Ai Tools, Fikra Academy, and ChatGPT Plus DZ are actively adapting global AI technologies to local economic and educational contexts.

Pricing strategies vary across vendors, with subscription-based models, freemium offerings, and bundled multi-AI packages aimed at making these tools accessible to a wide range of academic users. Service quality plays a critical role in adoption, with positive user experiences linked to responsive support, intuitive interfaces, and reliability, while usability issues and slow customer service limit engagement for some platforms.

Risk and compliance assessments indicate that transparency, ethical adherence, and secure payment mechanisms are essential for building trust in AI tools, particularly in academic environments where shared accounts or ambiguous terms of service could compromise both users and vendors. Business models reflect a strategic focus on academic institutions, with vendors tailoring their offerings to meet the needs of students and faculty, thereby fostering early adoption and potential long-term engagement.

Overall, this study highlights the intersection of technology, media, and academic practices in Algeria, emphasizing the need for institutional support, comprehensive training, and regulatory oversight to ensure effective, ethical, and equitable use of AI tools. Future research could explore longitudinal impacts of AI adoption on academic productivity, learning outcomes, and scholarly integrity, as well as comparative studies across other emerging markets in North Africa.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study focuses publicly on a selected set of visible AI suppliers and depends on social media and website data, which cannot occupy all member details or private institutional agreements. In addition, the user’s answers may be biased for more vocal respondents, and the findings are specific in the context of Algerian higher education, and generally limits. Future research can extend the extent of longitudinal adopted patterns, comparative studies in North Africa, institutional collaboration and user satisfaction, compliance and educational productivity and integrity to involve quantitative studies to assess the large effect of AI units on educational productivity and integrity.

Disclosure Statement

The author declares no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Funding Statement

This research received no financial support or grants from universities, government agencies, funding organizations, or other entities.

References

- Abiri, G. (2024). Generative AI as digital media. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4878339.

- Albarran, A. B. (2016). The media economy (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Algeria Press Agency. (2025, May 5). Algeria extends tax net to income from unregistered online activities. Retrieved from https://apanews.net/algeria-extends-tax-net-to-income-from-unregistered-online-activities/.

- Binns, R. (2018). Fairness in machine learning: Lessons from political philosophy. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 149–159. [CrossRef]

- Business Insider. (2025, July). Nonprofits develop AI tools to combat global educational inequities. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/nonprofits-ai-tools-edtech-global-inequities-2025-7.

- Cheriti, F. (2025). Legal challenges of AI-generated journalism: Intellectual property rights and regulations. Revue Algérienne des Sciences Juridiques et Politiques, 62(2), 203–217. https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/270606.

- Cheriti, F. (2025). McLuhan Today: AI as Medium, Shaping the Global Village and Extending Human Intellect. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Cheriti, F. (2025). Smartphone Screens and Growing Minds: The Benefits and Risks of Teaching Kids in a Digital World. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Columbia Business School. (2025, September). AI’s global adoption gap: Insights from non-English-speaking countries. Retrieved from https://business.columbia.edu/research-brief/global-ai-adoption-gap.

- Cursor Forum. (2025, May). AI pricing: An unfair burden on users in developing nations. Retrieved from https://forum.cursor.com/t/ai-pricing-an-unfair-burden-on-users-in-developing-nations/95963.

- Djahmi, M. (2025). The impact of the informal economy on economic diversification in Algeria. Algerian Scientific Journals Platform. https://asjp.cerist.dz/en/downArticle/440/9/1/269804.

- Economic Researcher Review. (2025). Digital economy and its role in enhancing financial institutions in Algeria. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393440829_Economic_Researcher_Review_Digital_Economy_and_Its_Role_in_Enhancing_Financial_Institutions_in_Algeria.

- Floridi, L., Cowls, J., Beltrametti, M., Chatila, R., Chazerand, P., Dignum, V., ... & Vayena, E. (2018). AI4People—An ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds and Machines, 28(4), 689–707. [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L., Cowls, J., Beltrametti, M., Chatila, R., Chazerand, P., Dignum, V., … & Vayena, E. (2018). AI4People-An ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds and Machines, 28(4), 689–707. [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, W., & Zidane, K. (2024). Teachers’ perceptions towards using artificial intelligence applications in Algerian higher education. ATRAS Journal, 5(1), 253–270.

- Katz, M., Shapiro, C., & Varian, H. (2018). Network effects and the economics of sharing digital subscriptions. Journal of Media Economics, 31(2), 65–78.

- Khan, M. S. (2024). Artificial intelligence for low-income countries. Nature Communications, 15(1), 1234.

- Kumar, V., & Rajan, B. (2021). Consumer behavior and informal markets: Insights from subscription sharing. Journal of Business Research, 130, 404–414. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X., Griffith, D., Liu, S., & Shi, Y. (2020). Subscription sharing and platform strategy in digital services. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 37(1), 144–159. [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. [CrossRef]

- Technology and Society. (2025, February). Unraveling the true cost of the global AI skills gap. Retrieved from https://technologyandsociety.org/the-hidden-multiplier-unraveling-the-true-cost-of-the-global-ai-skills-gap/.

- U.S. Department of State. (2024). 2024 Investment Climate Statements: Algeria. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-investment-climate-statements/algeria/.

- UNCTAD. (2025, August 26). Harnessing Africa’s digital economy for regional integration and shared prosperity. Retrieved from https://unctad.org/news/harnessing-africas-digital-economy-regional-integration-and-shared-prosperity.

- UNFCCC. (2025, July). AI and climate action: Opportunities, risks, and challenges for developing countries. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/news/ai-and-climate-action-opportunities-risks-and-challenges-for-developing-countries.

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).