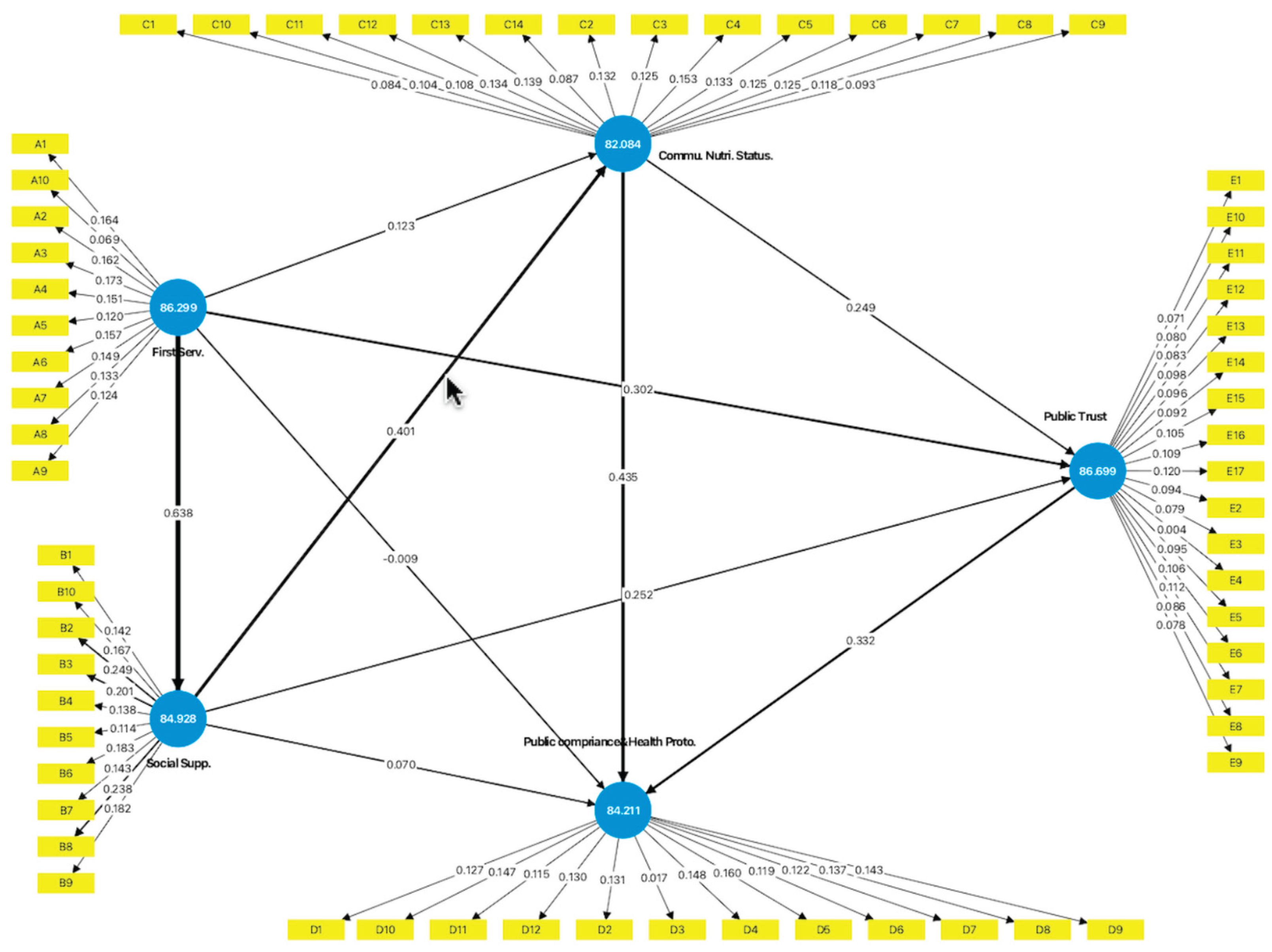

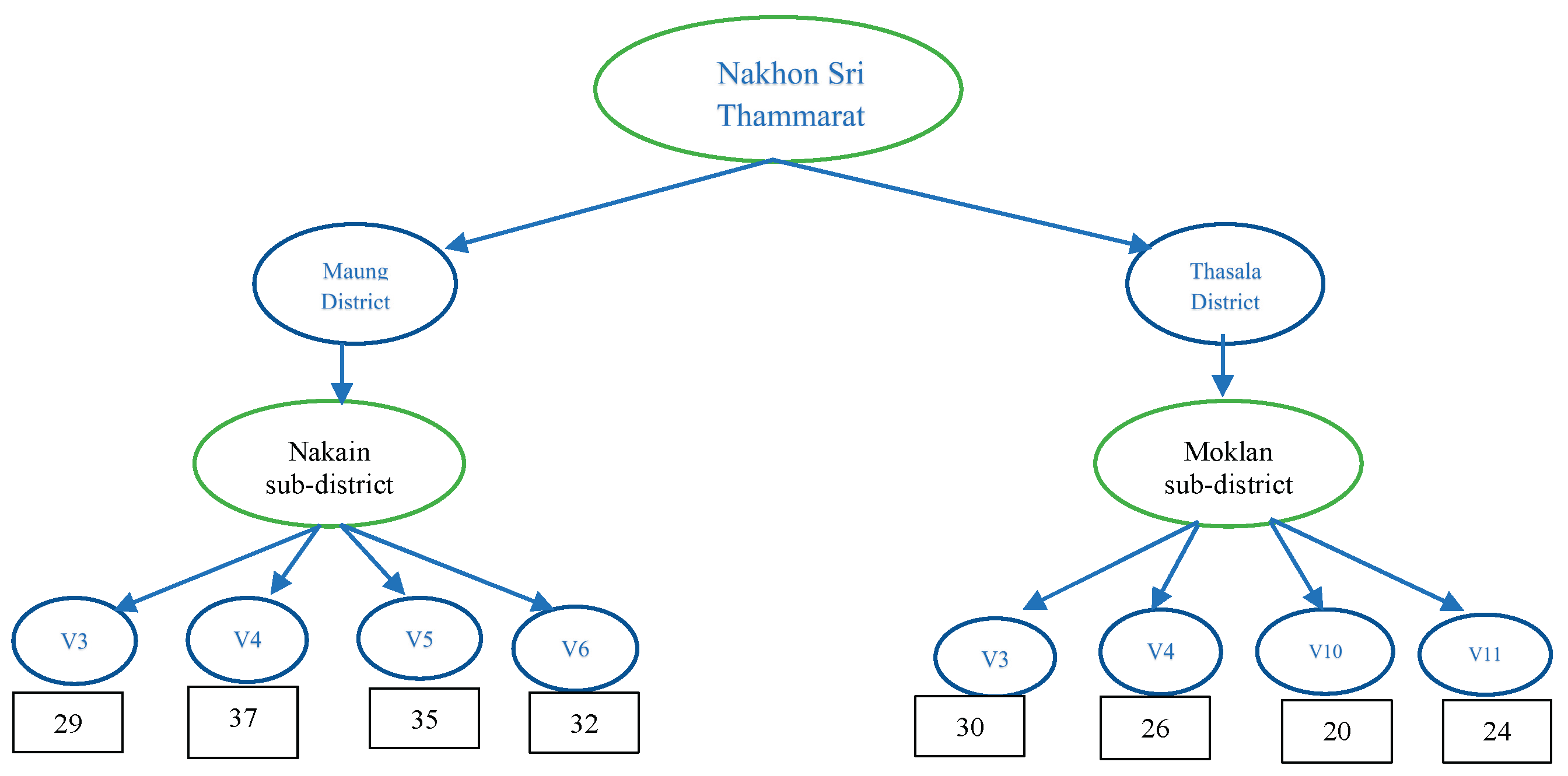

The 233 participants were selected as the samples for this study in accordance with the inclusion criteria. The sample population was predominantly female, with ages ranging from 30 to 50 years. Their educational background primarily consisted of completing primary and secondary schooling. The majority were employed as private sector employees or merchants, and most were married. The protective model is illustrated using Smart Partial Least Squares (Smart PLS).

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

The data analysis utilizing the Smart Partial Least Squares (Smart-PLS-SEM) method elucidates the model concerning COVID-19 prevention. The model is delineated through: 1) Construct reliability and validity of the COVID-19 protection model' (refer to

Table 1); 2) Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations, which demonstrates discrimination validity (refer to

Table 2); 3) Presenting the power of the structural model using Path Coefficients (refer to

Table 3); 4) Presenting the power of the structural model using R

2 values (refer to

Table 4); 5) Fomell-Larcker Criterion (refer to

Table 5); 6) Inter-construct correlation matrix among the latent variables to assess validity (refer to

Table 6); 7) An evaluation of the structural model, including the examination of potential multicollinearity among predictor constructs, tolerance, and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) (refer to

Table 7); 8) The Model Fit used to illustrate the adequacy of the structural model (See in

Table 8); 9) Presenting the Predictive Relevance (Q²) of Endogenous Constructs (See in

Table 9); 10) Presentation of the hypotheses assessment of the Preventive Model (See

Table 10). Additionally, the PLS-ESM model used to illustrate the protective role of COVID-19 within the Thai Muslim community in Thailand is presented in

Figure 1, along with six hypotheses.

This table showed construct reliability and convergent validity. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.741 to 0.901, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.70 and indicating good internal consistency. Likewise, composite reliability (CR) values were above 0.80 for all constructs (0.811–0.917), further confirming measurement reliability. In contrast, the average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.314 to 0.491, below the usual benchmark of 0.50. These results suggest limitations in convergent validity, as the constructs only explain a modest portion of the variance explained by their indicators. Still, considering the strong reliability coefficients and evidence of discriminant validity from the HTMT criterion, the constructs were considered suitable for use in the structural model analysis.

Table 2.

The Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations Presenting the Discrimination Validity (HTMT).

Table 2.

The Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations Presenting the Discrimination Validity (HTMT).

| Construct Variables |

First Serv. |

Social Supp. |

Commu. Nutri. Status |

Public compriance&Health Proto. |

Public Trust |

| First Service |

– |

0.730 |

0.431 |

0.446 |

0.599 |

| Social Support |

0.730 |

– |

0.575 |

0.563 |

0.664 |

| Community Nutrition Status |

0.431 |

0.575 |

– |

0.719 |

0.546 |

| Public Compliance & Health Protocols |

0.446 |

0.563 |

0.719 |

– |

0.645 |

| Public Trust |

0.599 |

0.664 |

0.546 |

0.645 |

– |

The table demonstrates that discriminant validity was evaluated utilizing the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT). The HTMT values for all construct pairs ranged from 0.431 to 0.730, with 95% confidence intervals below the conservative threshold of 0.85 (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015). These results indicate that discriminant validity is established according to the HTMT criterion, even though the Fornell–Larcker criterion was not fully satisfied. This suggests that, although conceptual overlap exists among some constructs, they are empirically distinct and can be reliably used in the structural model.

Table 3.

Presenting the power of the structural model using Path Coefficients.

Table 3.

Presenting the power of the structural model using Path Coefficients.

| Path |

β |

T-statistic |

p-value |

| First Service → Social Support |

0.638 |

13.288 |

<0.001 |

| First Service → Public Trust |

0.557 |

8.874 |

<0.001 |

| First Service → Public Compliance&Health proto. |

0.385 |

5.018 |

<0.001 |

| Community Nutrition Status→ Public Compliance&Health proto. |

0.518 |

7.179 |

<0.001 |

| Community Nutrition Status→ Public Trust |

0.249 |

3.546 |

<0.001 |

| Social Support → Public Compliance&Health proto. |

0.361 |

4.062 |

<0.001 |

| Social Support → Community Nutrition Statatus |

0.401 |

5.203 |

<0.001 |

| Social Support → Public Trust |

0.352 |

4.078 |

<0.001 |

| Public Trust → Public Compliance&Health Proto. |

0.332 |

3.211 |

0.001 |

The analysis of the structural model revealed several significant pathways among the latent constructs. First, the 'First Service' exerted the most substantial influence on 'Social Support' (β = 0.638, T = 13.288, p < 0.001), emphasizing its vital role in activating community support mechanisms. Additionally, 'First Service' had a direct impact on 'Public Trust' (β = 0.302, T = 3.260, p = 0.001) and exhibited a moderate but significant effect on 'Public Compliance and Health Protocols' (β = 0.385, T = 5.018, p < 0.001). The 'Community Nutrition Status' significantly affected both 'Public Compliance' (β = 0.435, T = 5.135, p < 0.001) and 'Public Trust' (β = 0.249, T = 3.546, p < 0.001), underscoring the importance of community-level nutrition in influencing health-related behaviors. Moreover, 'Public Trust' was identified as a significant predictor of 'Public Compliance' (β = 0.332, T = 3.211, p = 0.001). 'Social Support' made significant contributions to 'Community Nutrition Status' (β = 0.401, T = 5.203, p < 0.001) and 'Public Trust' (β = 0.252, T = 3.222, p = 0.001), although its direct effect on compliance was non-significant (β = 0.070, T = 0.811, p = 0.418). Collectively, these findings highlight the interdependent mechanisms among service provision, nutrition, trust, and social support that drive public compliance with health protocols.

Table 4.

Presenting the power of the structural model using R2 values.

Table 4.

Presenting the power of the structural model using R2 values.

| Construct |

R² |

Interpretation |

| Community Nutrition Status |

0.435 |

Moderate |

| Public Trust |

0.494 |

Moderate |

| Public compliance&Health proto. |

0.232 |

Weak-to-moderate |

| Social Support |

0.593 |

Moderate-to-strong |

| |

|

|

The explanatory power of the model was evaluated using R² values for the endogenous constructs. Social Support achieved the highest explained variance (R² = 0.593), indicating a moderate to strong effect from its predictors. Public Trust (R² = 0.494) and Community Nutrition Status (R² = 0.435) both demonstrated moderate explanatory power, indicating that nearly half of the variance in these constructs was accounted for by the model. In contrast, Public Compliance with Health Protocols recorded a relatively lower R² value of 0.232, reflecting weak-to-moderate explanatory power. These findings suggest that while the model adequately explains social support, trust, and nutrition, compliance behaviors are more complex and likely influenced by additional factors beyond those included in the current framework.

Table 5.

Presenting the Discriminant validity using Fomell-Larcker Criterion.

Table 5.

Presenting the Discriminant validity using Fomell-Larcker Criterion.

| Latent variable |

Commu. Nutri. Status |

First Serv. |

Public compriance&Health Proto. |

Public-Trust |

Social Supp. |

| Commu. Nutri. Status |

0.553 |

|

|

|

|

| First Serv. |

0.430 |

0.661 |

|

|

|

| Public compliance&Health proto. |

0.716 |

0.434 |

0.641 |

|

|

| Public Trust. |

0.544 |

0.615 |

0.612 |

0.605 |

|

| Social Supp. |

0.588 |

0.770 |

0.672 |

0.559 |

0.485 |

This table indicates that none of the constructs satisfied the Fornell–Larcker criterion, as the correlations between specific construct pairs exceeded the square root of their respective AVE values, thereby suggesting an overlap among the latent constructs. Specifically, Community Nutrition Status demonstrated a correlation with Public Compliance and Health Protocols (r = 0.716) that exceeded its AVE square root (0.553). Similarly, First Service correlated highly with Social Support (r = 0.770), and Public Trust correlated with Social Support (r = 0.672), both exceeding their AVE square roots (0.661 and 0.612, respectively).

Table 6.

Presenting the inter-construct correlation matrix among the latent variables.

Table 6.

Presenting the inter-construct correlation matrix among the latent variables.

| Latent variable |

First Serv. |

Social Supp. |

Commu. Nutri. Status |

Public compliance & Health proto. |

Public Trust. |

| First Serv. |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

| Social Supp. |

0.384 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| Commu. Nutri. Status |

0.382 |

0.624 |

1.000 |

|

|

| Public compliance&Health proto. |

0.318 |

0.278 |

0.201 |

1.000 |

|

| Public Trust. |

0.541 |

0.585 |

0.492 |

0.379 |

1.000 |

Table 4 illustrates the inter-construct correlations among the latent variables. The analysis indicates moderate correlations across most constructs, thereby supporting their empirical distinctiveness

. 'First Service' exhibits a positive and moderate correlation with

'Public Trust' (r = 0.541), suggesting that access to frontline health services enhances trust in the healthcare system.

'Social Support' demonstrates the strongest association with

'Community Nutrition Status' (r = 0.624), emphasizing the significance of collective support mechanisms in maintaining community-level nutritional resilience. In comparison

, 'Public Compliance with Health Protocols' shows relatively weak correlations with other constructs (r = 0.201–0.379), implying that compliance behaviors may be less directly influenced by external factors such as services or support, and may instead rely on intrinsic determinants such as public trust. All correlations remain below the threshold of 0.70, thereby mitigating concerns of multicollinearity and confirming the distinctiveness of the constructs for subsequent structural model evaluation.

Table 7.

Structural Model Assessment presented the potential multicollinearity among the predictor constructs, tolerance, and variance inflation factor (VIF).

Table 7.

Structural Model Assessment presented the potential multicollinearity among the predictor constructs, tolerance, and variance inflation factor (VIF).

| Latent variable |

Tolerance |

VIF |

| First Serv. |

0.599 |

1.669 |

| Social Supp. |

0.510 |

1.963 |

| Commu. Nutri. Status |

0.583 |

1.714 |

| Public compliance&Health proto. |

0.558 |

1.792 |

| Public Trust. |

0.520 |

1.922 |

This table demonstrates that multicollinearity was assessed utilizing tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) metrics. The tolerance values ranged from 0.510 to 0.599, while the corresponding VIF values spanned from 1.669 to 1.963. All VIF figures remained significantly below the conservative threshold of 3.0, thereby indicating the lack of problematic multicollinearity among the predictor constructs. These findings suggest that each latent variable contributed unique explanatory power to the model, without redundancy, thereby supporting the robustness of the structural model estimation.

Table 8.

The Model Fit used to illustrate the adequacy of the structural model.

Table 8.

The Model Fit used to illustrate the adequacy of the structural model.

| Index |

Value |

Threshold |

| SRMR |

0.089 |

<0.10 |

| NFI |

0.472 |

>0.90

(CB-SEM standard) |

| d_ULS |

16.046 |

– |

| d_G |

4.627 |

– |

The model fit indices were assessed to evaluate the adequacy of the structural model. The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value was 0.086 for both the saturated and estimated models, which is below the recommended threshold of 0.10, indicating an acceptable fit. The squared Euclidean distance (d_ULS = 14.884) and the geodesic distance (d_G = 4.957) showed stable values between the saturated and estimated models, further confirming model adequacy. The chi-square statistic was 5067.678, a value expected to be inflated due to the model’s complexity and sample size. The normed fit index (NFI) was 0.472, which falls below conventional cut-offs (>0.90). However, it should be noted that NFI is less informative in the context of PLS-SEM, as the approach prioritizes prediction rather than exact model fit.

Table 9.

Presenting the Predictive Relevance (Q²) of Endogenous Constructs.

Table 9.

Presenting the Predictive Relevance (Q²) of Endogenous Constructs.

| Construct |

Q² Predict |

RMSE |

MAE |

| Community Nutrition Status |

0.120 |

0.947 |

0.776 |

| Public Compliance & Health Protocols |

0.126 |

0.946 |

0.730 |

| Public Trust |

0.266 |

0.868 |

0.637 |

| Social Support |

0.379 |

0.800 |

0.595 |

Predictive validity was evaluated using Stone-Geisser’s Q² values generated through PLSpredict. As shown in

Table 9, all endogenous constructs demonstrated Q² values greater than 0, thereby confirming their predictive relevance (Hair et al., 2019). Specifically, Community Nutrition Status (Q² = 0.120) and Public Compliance with Health Protocols (Q² = 0.126) indicated small-to-moderate predictive power, while Public Trust (Q² = 0.266) reflected moderate predictive power. Social Support showed the strongest predictive relevance (Q² = 0.379), surpassing the threshold for a significant predictive effect. These results collectively suggest that the structural model not only explains variance but also reliably predicts unseen data.

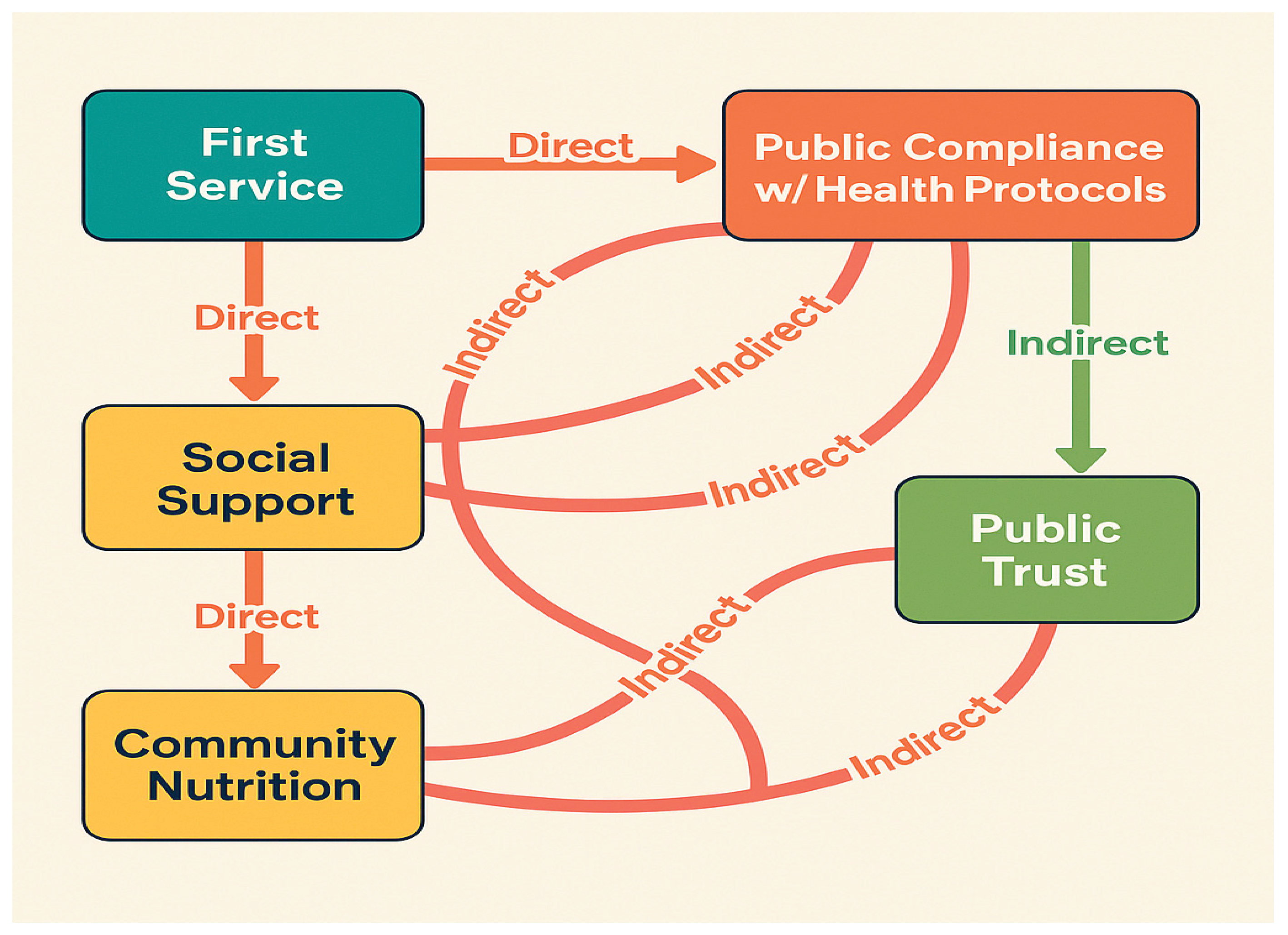

Mediation analysis indicated that First Service had a significant direct effect on Public Compliance (β = 0.385, p < 0.001), as well as an indirect impact via Public Trust (β ≈ 0.185, p < 0.01), confirming partial mediation. Similarly, Social Support significantly predicted Compliance directly (β = 0.361, p < 0.001) and indirectly through Community Nutrition (β ≈ 0.21, p < 0.01). These results suggest that both trust and nutrition function as important mediating mechanisms that enhance the impact of frontline services and social support on compliance with health protocols.

Figure 2.

Demonstrates the Protective Model of COVID-19 Among the Thai Muslim Community in Thailand; Smart PLS-SEM Version 4.1.1.

Figure 2.

Demonstrates the Protective Model of COVID-19 Among the Thai Muslim Community in Thailand; Smart PLS-SEM Version 4.1.1.

The Bootstrap analysis demonstrated that First Service exerted the most decisive influence on Social Support (β = 0.838), underscoring the critical role of frontline service provision in fostering supportive community networks. Community Nutrition Status emerged as the most crucial direct predictor of Compliance with Health Protocols (β = 0.518), followed by Social Support (β = 0.361) and Public Trust (β = 0.332). Notably, the model highlights several indirect pathways: First Service indirectly promoted compliance through its impact on Social Support, Community Nutrition Status, and Public Trust. In terms of performance scores, Public Trust (86.499) and First Service (86.299) achieved the highest values, indicating that these constructs not only play a pivotal role but are also well-performing in the studied community context. These findings suggest that strengthening service accessibility and public trust, alongside promoting nutritional resilience, are central strategies for enhancing compliance with preventive measures.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing Results

The structural model was evaluated to examine the six hypothesized relationships. The findings demonstrated robust support for the proposed framework, with several key pathways achieving statistical significance as detailed in the subsequent table.

Table 10.

Presentation of the hypotheses assessment of the Preventive Model.

Table 10.

Presentation of the hypotheses assessment of the Preventive Model.

| Hypothesis |

Path |

β (Coefficient) |

T-value |

p-value |

| H1 |

First Service → Adaptation (via Compliance, Trust, Social Support) |

0.385–0.638 |

5.018–13.288 |

<0.001 |

| H2 |

Public Trust → Compliance/Adaptation |

0.332 |

3.211 |

0.001 |

| H3 |

Public Compliance → Adaptation |

0.435 |

5.135 |

<0.001 |

| H4 |

Social Support → Nutrition, Trust, Compliance |

0.361–0.401 |

5.203 |

<0.001 |

| H5 |

Community Nutrition Status → Compliance, Trust |

0.249–0.518 |

3.546–7.179 |

<0.001 |

| H6 |

Public Trust mediates Health Protocol → Adaptation |

– |

– |

– |

First, First Service exhibited a strong positive influence on adaptation and COVID-19 prevention through its direct impact on Public Compliance with Health Protocols (β = 0.385, p < 0.001), Social Support (β = 0.638, p < 0.001), and Public Trust (β = 0.557, p < 0.001), thereby supporting H1.

Second, Public Trust was shown to positively affect compliance and adaptation (β = 0.332, p = 0.001), lending support toH2.

Third, Public Compliance with Health Protocols significantly predicted adaptation to COVID-19 (β = 0.435, p < 0.001), confirmingH3.

Fourth, Social Support exerted significant effects on Community Nutrition Status (β = 0.401, p < 0.001), Public Trust (β = 0.352, p < 0.001), and Compliance (β = 0.361, p < 0.001), thereby validatingH4.

Fifth, Community Nutrition Status significantly enhanced compliance (β = 0.518, p < 0.001) and trust (β = 0.249, p < 0.001), confirmingH5.

Finally, mediation analysis suggested that Public Trust served as a mediator between health protocols and adaptation outcomes, thereby partially supporting H6. Overall, the results indicate that frontline service delivery, community nutrition, social support, and public trust are interdependent mechanisms that collectively drive compliance and adaptation to COVID-19.

4.3. Discussion and Conclusions

The findings of this study emphasized the crucial role of community nutrition status and public trust in predicting adherence to COVID-19 health protocols. While first-line health services did not exert a direct impact on compliance, their influence was mediated through enhanced nutritional well-being and trust in health systems. Similarly, social support significantly improved both community nutrition and trust, although its direct effect on compliance was not statistically significant. These results suggest that indirect pathways—particularly through public trust and nutritional resilience—are more influential in shaping adherence behaviors than direct service provision alone.

Discriminant validity was evaluated utilizing the HTMT criterion. All HTMT values ranged from 0.431 to 0.730, which are comfortably below the conservative threshold of 0.85, thereby affirming adequate discriminant validity among the latent constructs. This result holds significance, especially considering that the Fornell–Larcker criterion produced mixed outcomes. Nevertheless, consistent with prevailing PLS-SEM methodological guidelines (Henseler et al., 2015; Hair et al., 2021), the HTMT evaluation offers more robust evidence that the constructs examined in this study are empirically distinct.

These findings emphasize the importance of addressing both direct and indirect pathways to enhance compliance. In accordance with WHO guidelines, it is essential to enhance frontline health services, ensure adequate nutrition, and promote public trust as key strategies to sustain adherence to preventive measures. The integration of these approaches can enhance community resilience and lead to a more effective response to the pandemic.

The combined assessment indicates that the measurement and structural models are adequate for predictive modeling, though not without limitations. While HTMT results support discriminant validity, the Fornell–Larcker criterion reveals overlap between constructs such as Social Support, Community Nutrition, and Public Trust, which may be expected given their conceptual interrelatedness in the context of community health behavior. Cross-loadings suggest that items may capture multidimensional aspects of health prevention, reflecting the complexity of behavioral constructs in pandemic settings. Despite these overlaps, the absence of multicollinearity (VIF < 3.5) reinforces the robustness of the indicators. Regarding model fit, the SRMR confirms an acceptable approximation of observed data. In contrast, the low NFI reflects a known limitation of PLS-SEM, where predictive relevance and variance explanation are prioritized over global fit indices. These findings align with methodological recommendations (Hair et al., 2019; Sarstedt et al., 2022) and suggest that the model remains valid for examining community-based COVID-19 prevention behaviors.

The predictive validity results highlight the robustness of the proposed COVID-19 prevention model. The consistently positive Q² values support the view that the model possesses sufficient predictive relevance across behavioral constructs, particularly for Public Trust and Social Support, which emerged as the strongest predictors. This finding aligns with the WHO's recommendations, which emphasize strengthening community networks and building trust as core strategies for enhancing compliance with health protocols during pandemics (WHO, 2020). Furthermore, the predictive relevance of Community Nutrition Status underscores the broader role of social determinants of health in shaping preventive behavior, reinforcing evidence that adequate nutrition contributes not only to physical resilience but also to psychological readiness for health adherence (Marmot & Allen, 2020). Taken together, the results confirm that the model is not only explanatory but also predictive, thereby providing a strong empirical basis for designing public health interventions that integrate frontline services, social support, and nutrition in pandemic response strategies.

The mediation analysis verified significant indirect effects in the proposed model. The influence of First Service through Public Trust aligns with the World Health Organization’s focus on trust as a crucial element of effective pandemic response (WHO, 2020). Accessible, dependable primary health services not only provide care but also reinforce legitimacy and confidence in health policies, encouraging adherence to preventive behaviors.

Figure 3.

direct determinants and indirect pathways created by the authors using AI-assisted design (OpenAI, 2025).

Figure 3.

direct determinants and indirect pathways created by the authors using AI-assisted design (OpenAI, 2025).

Similarly, the indirect pathway from Social Support to Compliance via Nutrition underscores the interconnectedness between social determinants of health and behavioral outcomes. Supportive networks facilitate access to nutritional resources, promote healthier dietary practices, and cultivate a collective sense of resilience. Consistent with international research (Marmot & Allen, 2020; Islam et al., 2021), the findings emphasize that improving nutritional well-being serves as a mechanism through which community support enhances compliance.