Introduction

Energy security and global warming have become a fundamental challenge of humanity. Global efforts are increasingly focused on replacing traditional fossil fuels with renewable energy sources and advancing electrochemical technologies for efficient energy storage and conversion. Water electrolysers (ELs) and fuel cells (FCs) are in the centre of significant attention as promising devices to balance the seasonality of renewable energy production. FCs, which efficiently convert the chemical energy of high-density fuels like hydrogen directly into electricity with zero emissions, offer a promising solution to decarbonize the transport sector, a major contributor to global warming and responsible for nearly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions [

1].

The high capital expenditure (CAPEX) associated with state-of-the-art proton exchange membrane (PEM) FCs and ELs stands as an obstacle before widespread commercialization. It is caused by the use of platinum group metal (PGM) catalysts and perfluorinated membranes [

2]. As a result, there is a growing interest in complementary anion exchange membrane (AEM) technology, which operates under alkaline conditions and offers several advantages over PEMs: 1) kinetically more favorable oxygen evolution (OER) and reduction reactions (ORR) that reduces activation losses, 2) the possibility to use inexpensive non-precious metal catalysts, 3) sustainable membrane alternatives to traditional perfluorinated polymers, and 4) the use of inexpensive cell components due to the less corrosive operating environment [

3].

However, the wide-spread application of both AEMFCs and AEMWEs is currently hindered by the rapid degradation of AEMs under alkaline conditions, this challenge is further exacerbated at low hydration levels [

4]. In PEMs chemical degradation is mainly caused by electrophilic attack of oxidizing radicals formed during FC operation [

5]. In AEMs, however, it is predominantly caused by the nucleophilic attack of OH

− [

6]. Several OH

−-induced degradation pathways for AEMs have been proposed, including (1)

Hofmann elimination, (2) nucleophilic substitution, and (3) the formation of ylides, which may undergo further rearrangement via

Stevens or

Sommelet-Hauser mechanisms [

6]. These detrimental processes can occur simultaneously, significantly compromising membrane stability and prompting extensive research efforts aimed at enhancing the alkaline durability of AEMs.

Several studies have reported accelerated degradation under oxygen-saturated conditions, suggesting that reactive oxidising species (ROS) play a significant role in the degradation mechanisms of AEMs. Advancements in polymer backbones, quaternary ammonium headgroups, and crosslinking strategies have brought about a significant improvement in the alkaline stability of AEMs, however, strategies to improve the radical-induced degradation remain limited [

6].

Parrondo et al. were the first to observe a significantly higher loss in ion-exchange capacity during ex-situ stability tests of poly(

p-phenylene oxide)-based AEMs performed under oxygen saturated conditions compared to nitrogen degassed ones, highlighting the detrimental role of oxidative stress in AEM degradation [

7]. Experiments involving spin trapping and use of a fluorescent dye are interpreted by time-dependent formation of various ROS, such as HO

∙, HOO

∙ and O

2∙− [

7,

8].

The ex-situ stability test conducted by

Espiritu et al. also indicates increased IEC loss in vinylbenzyl chloride-grafted low-density polyethylene-based AEMs when exposed to oxygen [

9].

Wierzbicki and colleagues were the first to detect in-situ radical formation in various AEMs by operating a micro-AEM-FC within an Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) setup. This enabled spin trapping of HO

∙ and HOO

∙ radicals on the cathode side and H

∙ radicals on the anode side [

10]. Subsequent experiments revealed that radical formation occurs for both PGM-based and PGM-free electrocatalysts [

11]. Under the premise that radicals are involved in the degradation of AEMs, it becomes essential to evaluate the ex-situ stability of novel AEMs before subjecting them to time- and resource-intensive in-device testing.

To assess the alkaline stability of AEM headgroups or fabricated AEMs, a widely adopted approach involves exposing the materials to concentrated alkaline solutions, typically 1–12 M potassium hydroxide (KOH) or sodium hydroxide (NaOH), at elevated temperatures, i.e., 80–160 °C [

12].

In contrast, ex-situ degradation tests of PEMs, where degradation is driven by radicals,

Fenton’s reaction is the most common method to form oxidising radicals, HO

∙ and HOO

∙ via reactions (1) − (3) and evaluate stability.

While it may seem straightforward to subject AEMs to Fenton’s test to benchmark oxidative stability [

13]. at pH values above 5, highly oxidizing Ferryl radicals form rather than HO

∙ and HOO

∙ [

14,

15]. Reactivity and selectivity differ between Ferryl and HO

∙. Fenton chemistry, therefore, promotes misleading results in the study of HO

∙ radical-mediated degradation of AEMs.

Alternative approaches to generate radicals include thermal decomposition of dilute aqueous H

2O

2 solutions at elevated temperatures [

16]. or using UV activation. There are several limitations with these methods [

17]. First, thermal decomposition of H

2O

2 is not an efficient way to generate radicals [

18]. While radical formation is possible via reaction (4), at elevated temperatures the process is dominated by non-radical thermal decomposition pathways, reaction (5). Second, while UV activation of H

2O

2 can effectively generate radicals, it requires irradiation at wavelengths below 300 nm. At these wavelengths direct photochemistry of aromatic AEMs will certainly be non-negligible and may even constitute the main reaction pathway.

A recently developed protocol enables the simultaneous assessment of base- and radical-induced degradation of AEMs by immersion in oxygen-saturated aqueous alkaline solutions at elevated temperatures [

19]. While this method offers a more realistic simulation of operational conditions, it presents several limitations. First, the rate of radical formation is highly dependent on the concentration of dissolved oxygen. It decreases with both increasing temperature and hydroxide concentration, due to the salting-out effect [

20]. Second, because the protocol uses concentrated hydroxide solutions, it is not possible to distinguish between base-induced degradation and radical-induced degradation.

The concept of water radiolysis as a technique for selective production of specific radical species, using pulse- [

21]. gamma- or beta- irradiation [

22], is described in the literature in detail. These techniques allow for precise and quantitative control over radical formation, making them valuable tools for mechanistic studies. However, their application is limited by accessibility and costs, as they require specialized infrastructure which is unavailable in most research environments.

We recognized a need within the AEM research community for basic ex-situ degradation testing methods that are robust, affordable and accessible for standard laboratories. These should generate radical species representative of those produced in AEM FCs or ELs.

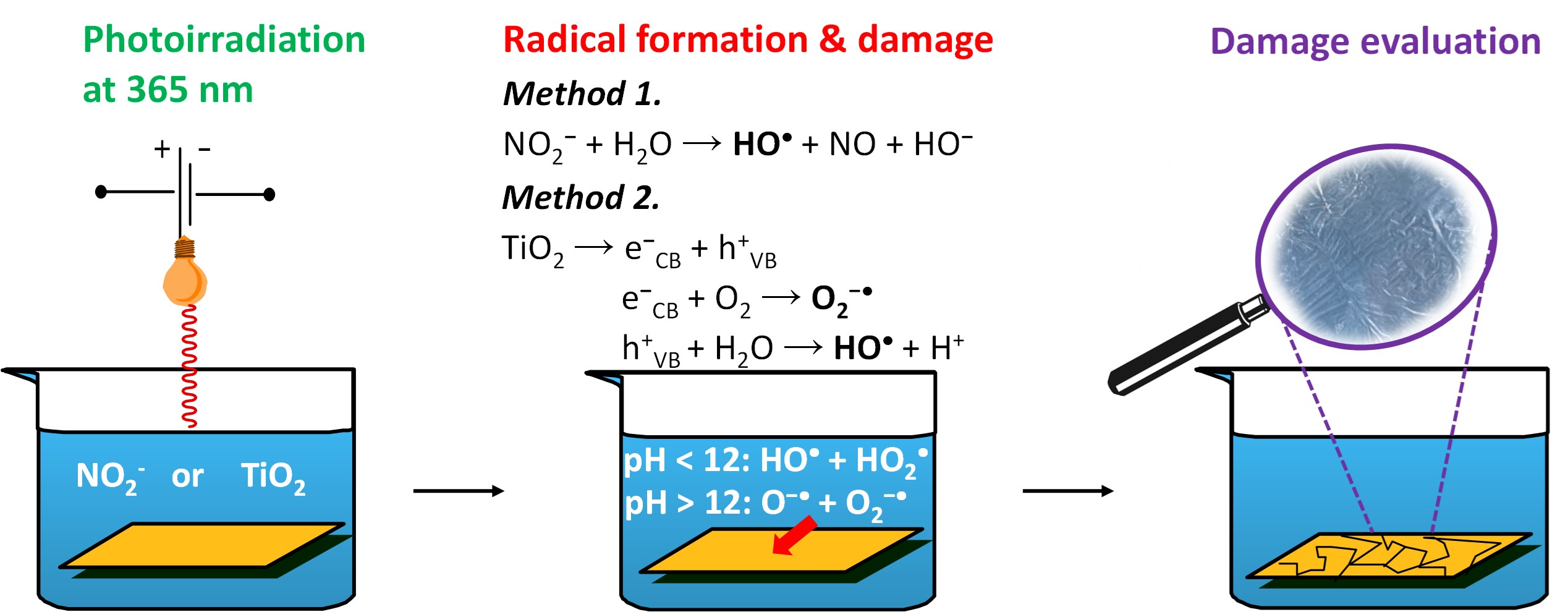

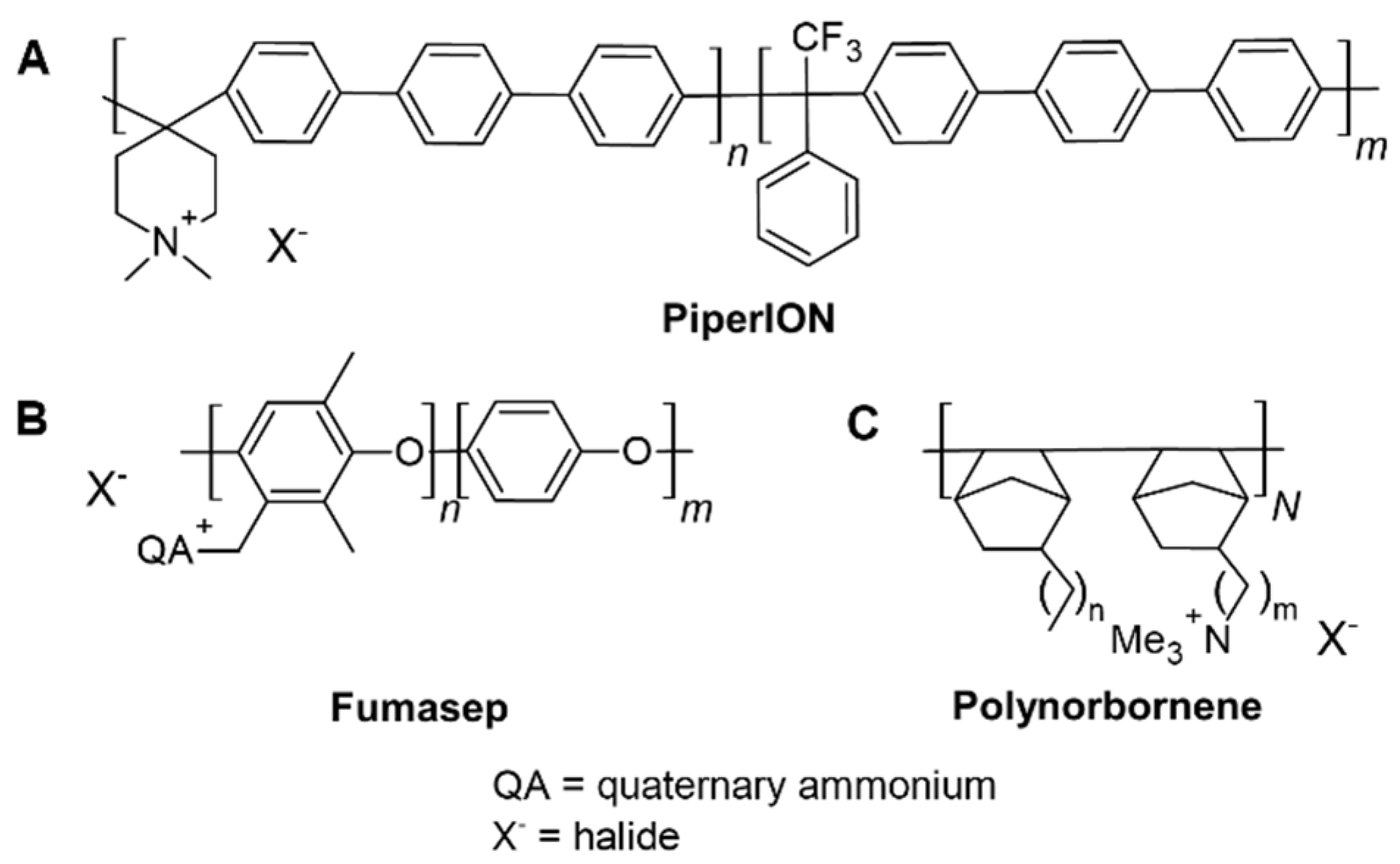

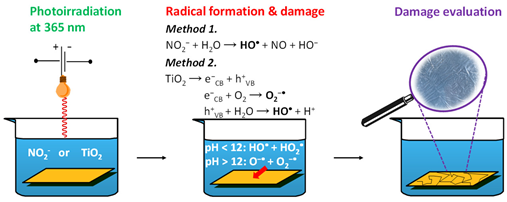

We adapt two known photochemical methods to generate radical species [

23,

24]. The effect of these treatments on AEMs is characterized. Both approaches rely on equipment that is either inexpensive or readily available in standard synthetic laboratories, making them highly accessible. Their practical applicability for ex-situ degradation studies will be demonstrated and discussed based on three commercially available, state-of-the-art AEMs: PiperION

®-40 (PiperION), FM-FAA-3-PK-75 (Fumasep), and PNB-R45 (Polynorbornene).

Results and Discussion

Photochemical Generation of Radicals

The speciation and reactivity of radicals relevant to AEM FCs and ELs depends on pH. The p

Ka of HO

∙ is 11.9 [

24], therefore, both its protonated and deprotonated forms, O

∙−, are present under the alkaline conditions of an AEM FC or EL, with the latter dominating. In contrast, the p

Ka of HOO

∙ is 4.8 [

25], thus, under strongly alkaline conditions it is present in its deprotonated form O

2∙−. We focus, therefore, on selective production of HO

∙/O

∙− and O

2∙− in presence of AEMs. Photolysis of nitrite produces HO

∙, reaction (6).

A critical review of the corresponding photochemistry was published by

Mack and Bolton [

26].

Takeda et al. recently showed a practical application of that reaction using dilute aqueous solutions of nitrite and a 365 nm UV-LED [

23]. The production rate of HO

∙ was estimated by the reaction with terephthalate, a highly sensitive and water-soluble fluorescent probe. Nitrite concentrations were limited to the micromolar range because, while nitrite serves as a photochemical source of hydroxyl radicals, reaction (6), it also acts as a highly efficient HO

∙ scavenger, reaction (7), with a reported rate constant of

k = 8 × 10

9 M

-1s

-1 [

27].

Maintaining nitrite concentrations in the micromolar range minimizes the effect of reaction (7). However, it also lowers the maximum achievable steady-state concentration of HO∙, as photolysis, reaction (6), is proportional to the absorption of photons. The latter is proportional to the availability and molar absorptivity of nitrite as a photochemical precursor.

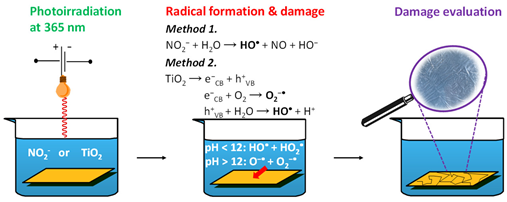

The stress-test of AEMs, on the other hand, requires elevated concentrations of HO

∙. We used 4.5 mM benzoic acid (BA) to probe for photochemically formed hydroxyl radicals, reaction (8), and observed the yield of reaction (8) as a function of the nitrite concentration which was varied between 0.1 mM and 2 mM.

We calculated the pseudo-first-order rate constants (

k’) for the reactions of hydroxyl radicals with nitrite and with BA by multiplying the reported second-order rate constants (

k) with the respective solute concentrations. The resulting

k’ values are proportional to the production rates of the respective processes, and their ratio is proportional to the relative product yields of the competing reactions (7) and (8), under various conditions,

Table 1.

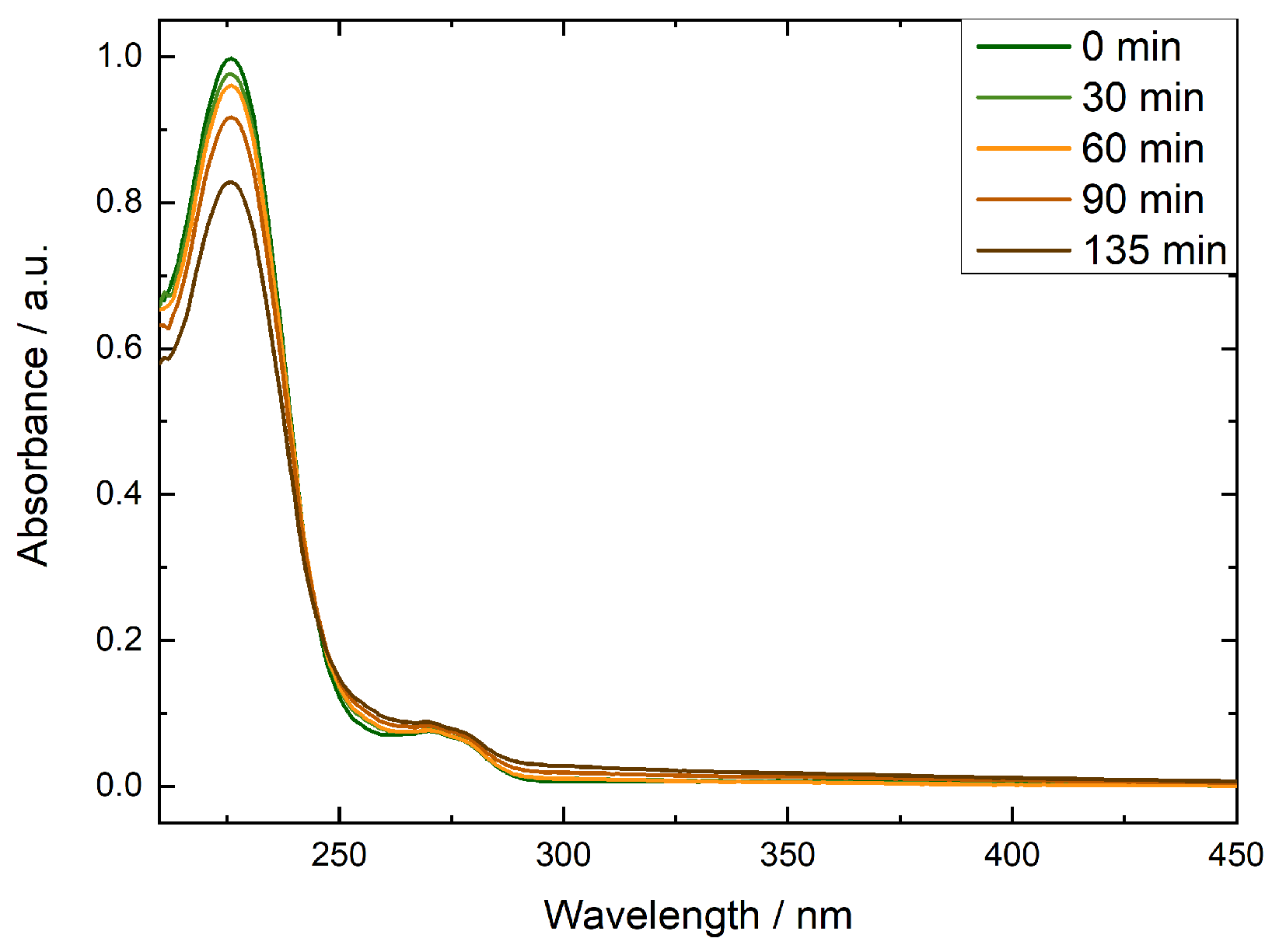

While approximately 92% of the formed HO∙ react with BA at a low nitrite concentration of 0.1 mM, only 36% will do so at a high nitrite concentration of 2 mM. The higher nitrite concentration significantly increases the production rate of HO∙ radicals (up to 20 times), which also increases BA degradation despite the lower relative yield of reaction (8).

The reaction model was tested using 4.5 mM BA in 0.1 mM NaOH (pH 10) and nitrite concentrations in the range of 0.6–2 mM. Experiments were performed under continuous irradiation at 365 nm. To selectively focus on radical-induced degradation, with limited influence from HO

−, irradiations were conducted at 80 °C and pH 10. BA degradation was monitored by its absorbance at 227 nm,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

The formation of HO

∙ can be assessed by photochemical probes via quantification of specific reaction products [

28], such as hydroxylated derivatives of BA. However, this method may underestimate HO

∙ formation if multiple parallel reaction pathways are present and the product concentrations are low. A more reliable, albeit less selective, alternative is to monitor the overall consumption of BA.

In all cases we observed a decrease of BA concentration over time. At shorter irradiation times BA degradation was larger at lower nitrite concentrations, after 135 min of continuous irradiation, the average degree of degradation increased with increasing nitrite concentration,

Figure 2. To inflict appreciable damage to commercial AEMs, we chose to use a higher nitrite concentration of 2 mM. The controls showed no BA degradation in the absence of irradiation or nitrite.

Not only HO

∙ but also O

2∙− is relevant for the degradation of AEM systems. Since nitrite irradiation forms HO

∙ and NO

∙, we looked for alternative approaches that generate O

2∙− instead. We adapted a photocatalytic method which forms radicals from TiO

2 suspension [

24]. Various ROS are generated in photocatalytic processes on TiO

2 surface when exposed to UV irradiation, reactions (9)-(11). Conduction band electrons react with dissolved oxygen forming superoxide radicals, and valance band holes react with water to produce HO

∙. Radical generation is dependent on TiO

2 crystal phase. Anatase type TiO

2 is more efficient at radical generation than rutile due to better charge separation and enhanced absorption of intermediate species [

29].

Irradiation with a 365 nm (3.4 eV) light source is sufficient to form radicals in a suspension of anatase-phase TiO

2, which has a band gap of approximately 3.2 eV [

30]. Accordingly, we irradiated aqueous solutions containing 4.5 mM BA, 0.1 mM NaOH (pH 10) and anatase TiO

2 at 365 nm for 30, 60 90 and 135 min at 80 °C. At an optimized TiO

2 concentration of 1mg mL

-1, time-dependent degradation of BA was observed,

Figure 2. In subsequent experiments, we implemented the two methods to evaluate the stability of commercial AEMs against radical attack.

Radical-Induced Degradation of AEMs

To evaluate and compare the two photochemical methods for studying radical-induced degradation of AEMs, we selected three commercially available, state-of-the-art AEMs: PiperION, Fumasep, and Polynorbornene,

Figure 3. The structural diversity of these membranes is the basis to demonstrate the broad applicability of the methods. While PiperION and Fumasep feature aromatic backbones [

31,

32]. Polynorbornene is based on a non-aromatic structure [

33]. Additionally, Fumasep and Polynorbornene incorporate mechanical reinforcement, whereas PiperION does not.

Practical Considerations

Before subjecting the AEMs to degradation tests, all samples were converted to the hydroxide form by ion-exchanging three times in 1 M KOH. It is important to note that when membranes are in the halide form, common for commercial AEMs such as Polynorbornene or Fumasep, the generated HO

∙ radicals react diffusion controlled with the halides via reactions (12) and (13) [

34,

35]. PiperION is shipped in the bicarbonate form. The reported rate constant for the reaction between carbonate and HO

∙, reaction (14), is one order of magnitude slower [

36]. Consequently, a portion of the generated HO

∙ will be consumed in these side reactions, reducing its availability for the primary reaction pathway. Formed X

2∙− and carbonate anion radicals are potent oxidants, however, not relevant for AEMs.

Accordingly, we performed all experiments with AEMs in the hydroxide form. Radical reactivity is known to be influenced by ionic strength [

37]. Therefore, we used 0.333 M sodium sulfate to establish the same ionic strength as at pH 14, typical of the environment in AEM FCs and ELs.

Although the reaction rate constants between hydroxide and HO

∙ are also relatively high, reaction (15), the reaction product is O

∙−, i.e., the deprotonated form of HO

∙ that dominates under the highly alkaline conditions typical for AEMs (pH > 12) [

38].

Next, we reacted the solution-immersed AEMs with primary radicals that were produced by irradiating the solution of 2 mM nitrite, 0.1 mM NaOH and 0.333 M Na2SO4, or a suspension of 10 gL-1 TiO2 in 0.1 mM NaOH and 0.333 M Na2SO4 at 365 nm for 30, 60 90 and 135 min.

Following irradiation, we performed a visual inspection of the AEM samples to assess their stability against radical attack, Figures S1-S3. We found that the colour of the PiperION samples darkened after prolonged irradiation with both methods, Figure S1. In contrast, a colour change was observed for both the Polynorbornene and Fumasep AEM samples only in the cases of the irradiated nitrite-containing solutions, Figures S2-S3.

Both chemical and mechanical degradation of ion-exchange membranes are strongly influenced by the presence of reinforcements and the material thickness. Thicker membranes generally exhibit a lower degree of degradation, as radicals penetrate less deeply, resulting in slower degradation rates. Additionally, reinforced membranes tend to better resist both mechanical and chemical degradation [

39].

Accordingly, when we examined changes in IEC of the AEMs subjected to degradation tests, we observed a gradual decrease in IEC across all methods and membrane samples (

Table 2). However, in the case of Fumasep, degradation was significantly suppressed. This can be attributed to the fact that this AEM was both reinforced and thicker than the other tested membranes, with a dry thickness of 75 µm compared to 40 µm for PiperION and 45 µm for Polynorbornene. We found that Polynorbornene lost approximately 17% and 22% of its IEC after 135 min of continuous irradiation of the nitrite- and TiO

2-containing solutions, respectively. In contrast, PiperION exhibited IEC losses of approximately 18% and 46% under the same conditions. It was surprising that degradation of PiperION showed an “induction phase” with the TiO

2 model. Up to 90 minutes irradiation, there was almost no change in the IEC. However, during the next 45 minutes there was a loss of almost 50%. This observation was confirmed several times.

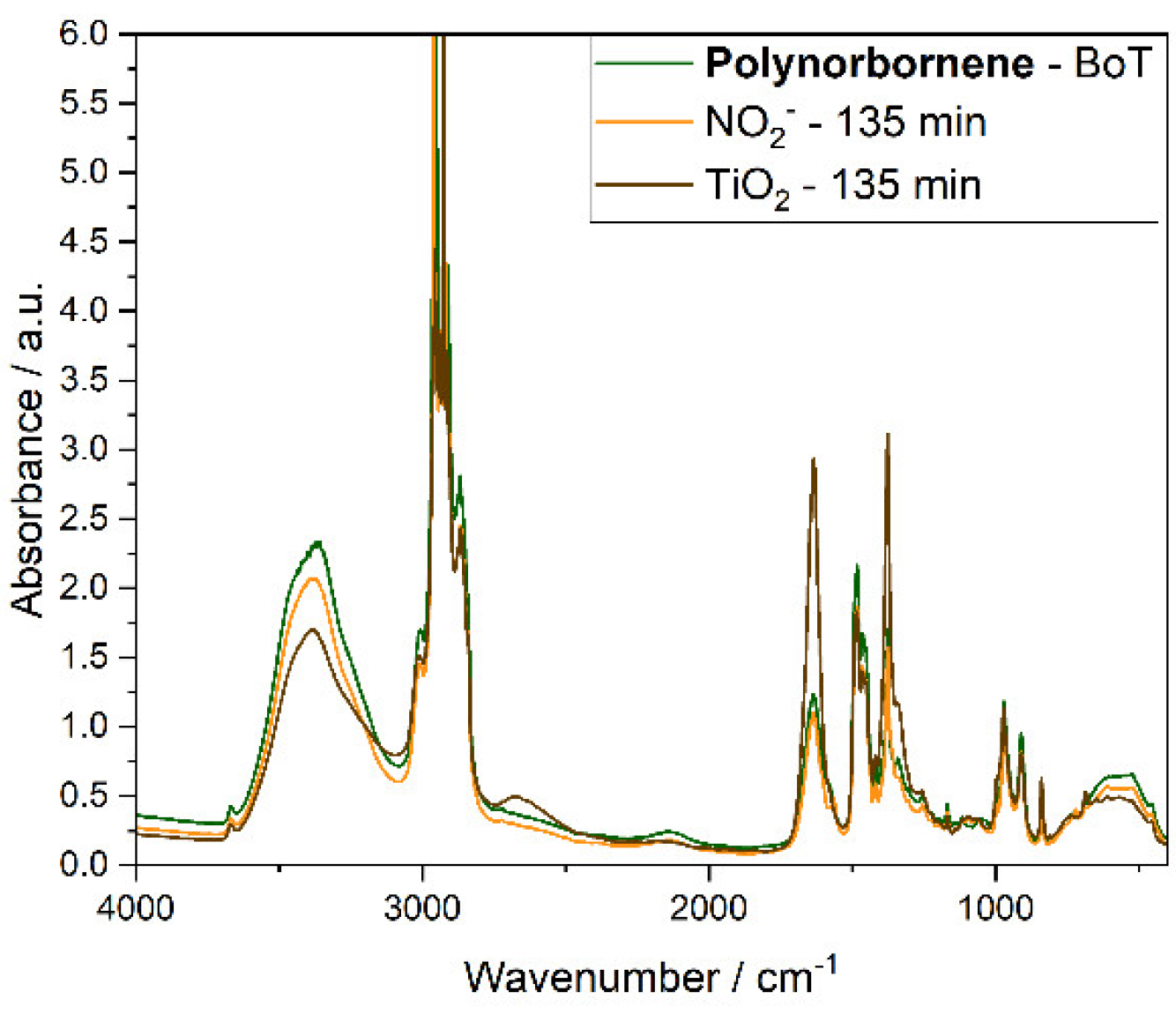

To qualitatively assess AEM degradation, we compared the FT-IR spectra recorded before (BoT) and after 135 minutes of degradation,

Figure 4 and Figures S4 and S5.

Consistent with the small change in IEC (

Table 2), no significant structural changes could be observed in the reinforced Fumasep samples following the degradation tests (

Figure S4). It is important to note that FT-IR measurements are semi-quantitative, and structural changes at the few-percent level may be difficult to detect.

In contrast, the Polynorbornene samples exhibited structural changes, particularly in the absorbance bands associated with C–N stretching vibrations, specifically at 836, 910, 970, and 1076 cm

−1 [

33].

Figure 4. Additionally, changes in the peaks at 1486, 1637, 2146, and 2870 cm

−1 suggest oxidative degradation of the polymer backbone and side chains, likely involving the formation of unsaturated and carbonyl-containing species. Both Fumasep and Polynorbornene samples were insoluble in common deuterated solvents, which precluded quantitative NMR analysis.

In the case of PiperION AEM, increased absorbance at 1633, 1380, 2657, and 2940 cm−1 indicates oxidative degradation, likely involving the formation of unsaturated and carbonyl-containing species and side-chain fragmentation. Notably, significant structural changes were observed at these frequencies in samples irradiated in the presence of TiO2 (Figure S5), whereas samples irradiated in the presence of nitrite showed minimal spectral changes.

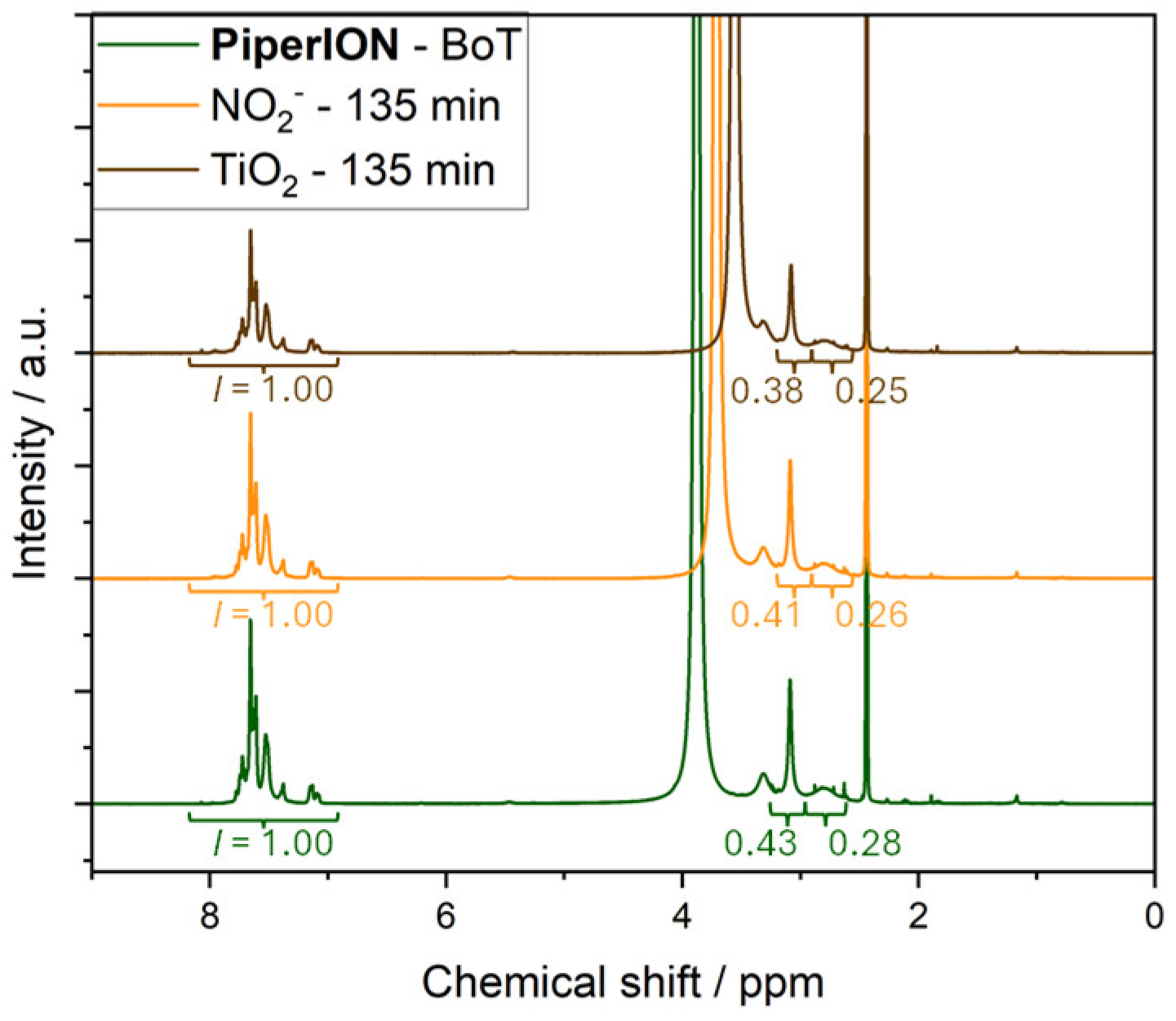

Next, we performed NMR analysis to further analyse degradation of PiperION. Addition of a small amount of TFA served to separate the protonated piperidine signals and downfield shift the water signal. We compared the ratio of the integrals for the piperidinium ring and quaternary ammonium headgroup, peaks at 2.88 and 3.13 ppm, and of the aromatic protons between 6.7 and 8.2 ppm,

Figure 5. Overlap of the water signal with the piperidinium protons at 3.4 ppm prevented integration of this latter peak. We found that the ratio of aliphatic-to-aromatic protons decreased in the case of both PiperION samples that were irradiated for 135 min in the presence of nitrite or TiO

2. This indicates loss of aliphatic protons, probably related to degradation of the quaternary ammonium headgroups, in good agreement with the ion-exchange capacity loss in

Table 2. Moreover, we observed decreased solubility and pronounced brittleness in both degraded PiperION samples, which may indicate crosslinking [

40].

Method Applicability to Compare AEMs

While both methods support the study of radical-induced degradation of AEMs, minimizing influence from HO

−-mediated pathways, they exhibit limitations. In the case of the irradiation of nitrite-containing solutions, there is effective competition between nitrite and the AEMs for the generated HO

∙ radicals. As a result, nitrite concentrations must be kept relatively low. However, excessively low nitrite concentrations inherently restrict the steady-state concentration of HO

∙ that can be generated, thereby limiting the extent of AEM degradation. In the authors’ opinion, using 2 mM nitrite offers a good balance between minimizing competition and maintaining sufficient radical generation for meaningful degradation. We note that at high oxygen concentrations, highly reactive NO

2∙ radicals form via reaction (16) [

41]. However, the high ionic strength established in our experiments, limited the availability of oxygen and minimised the interference of reaction (16).

In the case of TiO

2 suspensions, the rate of radical formation upon irradiation depends on both the crystal structure and the particle size [

42]. We observed effective radical generation using anatase-type TiO

2 with mesh 325. Vigorous stirring of the suspension is essential to maintain the photochemical generation of radicals, as insufficient stirring may cause the TiO

2 particles to sediment, reducing their exposure to light and thus limiting reaction efficiency. In contrast, for radical generation from nitrite solutions, if the nitrite concentration remains uniform, stirring will not affect the quantum yield of radicals. Both methods of radical production show a larger impact on relatively thin AEMs, as our results show that thicker and reinforced membranes tend to degrade less. This is likely due to the limited penetration depth of radicals, which limits degradation in more robust membrane structures.

Experimental Section

Chemicals and Reactants

Benzoic acid (>99.9%, EMSURE® ACS, Reag. Ph Eur), NaOH (>99%, pellets for analysis EMSURE®), potassium nitrite (ACS reagent, ≥96.0%) and anatase titanium(IV) dioxide (≥99%, 325 mesh) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. The AEMs used in this study, PiperION®-40 (PiperION), FM-FAA-3-PK-75 (Fumasep), and PNB-R45 (Polynorbornene), were purchased from Fuel Cell store. AEMs were exchanged into the hydroxide form following the procedures of the supplier. During the irradiation experiments, 365 nm light sources with a rated power of 3 W (Alonefire SV98-365nm, Shenzen ShiWang Technolgy Co. Ltd.) were used, with the charging cable continuously connected. The light source was mounted on top of 25 mL transparent glass vials in such a way that it was positioned 1 cm from the surface of the solution.

Small molecule study: In the experiments involving potassium nitrite, aqueous solutions containing 4.5 mM BA in 0.1 mM NaOH (pH 10) and varying potassium nitrite concentration of 0.6–2 mM were irradiated for 30, 60, 90 or 135 min at 365 nm at 80 °C. In the experiments involving TiO2, we irradiated at 80 °C aqueous solutions containing 4.5 mM BA, 0.1 mM NaOH (pH 10) and 1–10 mg mL-1 anatase TiO2 at 365 nm for 30, 60 90 and 135 min.

AEM study: before the irradiation experiments, commercial AEMs were converted to the hydroxide form by ion-exchanging three times in 1 M KOH and subjected immediately to irradiation to minimize the ion-exchange to carbonate form. AEMs were placed in a solution of 2 mM nitrite, 0.1 mM NaOH and 0.333 M Na2SO4, or a suspension of 10 mg mL-1 TiO2 in 0.1 mM NaOH and 0.333 M Na2SO4, and irradiated at 365 nm for 30, 60 90 and 135 min. Solutions were stirred at 80 °C at 400 rpm. Following the irradiation, the AEMs were placed in 1 M KOH, then washed successively in water and used directly to measure ion-exchange capacity.

Ion-exchange capacity (IEC) was measured by back titration of the membranes with 0.01 M KOH. AEM samples were placed into 1 M KOH solution for 1 h, washed successively with water, and placed in 0.01 M HCl solution for at least 4 h. Finally, the solutions were titrated with a standard 0.01 M KOH solution using a TitroLine

® 5000 automatic titrator. Samples were dried in the oven at 80 °C for overnight and the dry weight was measured. The IEC (expressed as mmol g

−1 dry polymer) was calculated according to the following equation:

UV-vis measurements were performed using a Thermo Scientific Evolution 220 UV apparatus. An automatic background subtraction was done prior to data analysis. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) measurements were performed using a Bruker vortex 80v apparatus. Measurements were performed under vacuum to suppress water absorption of the AEMs. Every measurement consisted of 20 scans that were averaged. Scanning was done from 400 to 4000 cm-1 with a spectral resolution of 2 cm-1. An automatic background subtraction was done prior to data analysis. Changes in the chemical structure of PiperION samples were analysed by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR, AVANCE NEO 400 MHz, Bruker, German) spectroscopy. The sample was dissolved in 500 µL DMSO-d6 and 2 µL trifluoroacetic acid was added. Chemical shifts were referenced to the DMSO-d6 solvent signal, 2.44 ppm.

Entry for the Table of Contents

Caption:

Ex-situ methods for evaluating the radical stability of anion exchange membranes. Radicals were generated by irradiation of an aqueous potassium nitrite solution or a TiO2 suspension, with the membranes immersed during exposure.