Submitted:

02 September 2025

Posted:

03 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Analysis of the Current Power System

2.1.1. Types of Power Plants

2.2. Description of Thermal Power Plants

2.3. Technical Characteristics of Thermal Plants

2.3.1. Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) Plants

2.3.2. Gas Turbine Plants

2.3.3. Steam Turbine Plants

2.4. Identification of Opportunities and Challenges

- According to CELEC EP, thermal plants require relatively less maintenance.

- Thermal plants play a crucial role by replacing hydropower during climate events such as droughts.

- Their relatively simple deployment makes thermal plants widely used worldwide, offering lower costs compared to other generation technologies.

- Thermal generation is not weather-dependent, allowing adaptation to any environment.

- Thermal efficiency is key, as it enables higher energy conversion with minimal losses.

- The use of fossil fuels causes significant environmental damage, and fuel prices may fluctuate, directly affecting electricity production.

- Thermal plants have a considerable environmental impact, producing high levels of CO2 emissions regardless of plant type.

- High emissions not only harm the environment but also contribute to respiratory illnesses, affecting both operators and local populations.

- Maintenance—whether corrective or scheduled—can require long periods, sometimes months, to replace major components.

2.5. Principles and Foundations of the William Newman Model for Power System Decarbonization

2.5.1. Development of a Strategic Plan for Decarbonization

2.5.2. Strategic Plan Development with Photovoltaic Systems

2.5.3. Monitoring and Adjustment

2.6. Implementation of Mixed-Integer Linear Programming for Power System Decarbonization: Considerations and Constraints

2.6.1. Considerations

2.7. Distributed Resources

2.7.1. Photovoltaic Generation

2.7.2. Wind Power Generation

2.7.3. Diesel-Based Power Supply

2.7.4. Battery-Based Backup Systems

2.7.5. Charge and Discharge Index

2.7.6. DOD

2.7.7. DR

3. Problem Formulation

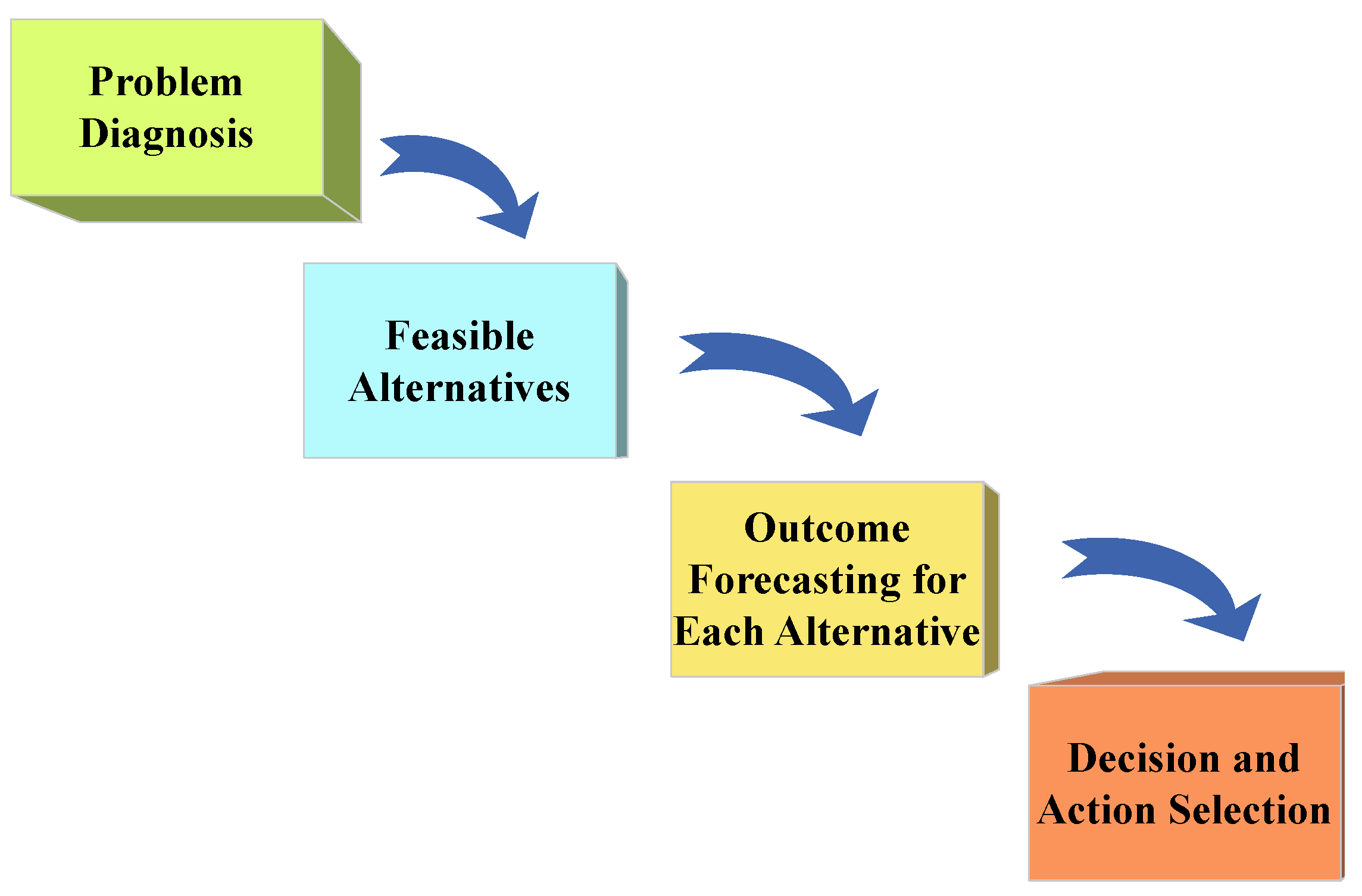

3.1. Decarbonization Process Using the William Newman Approach

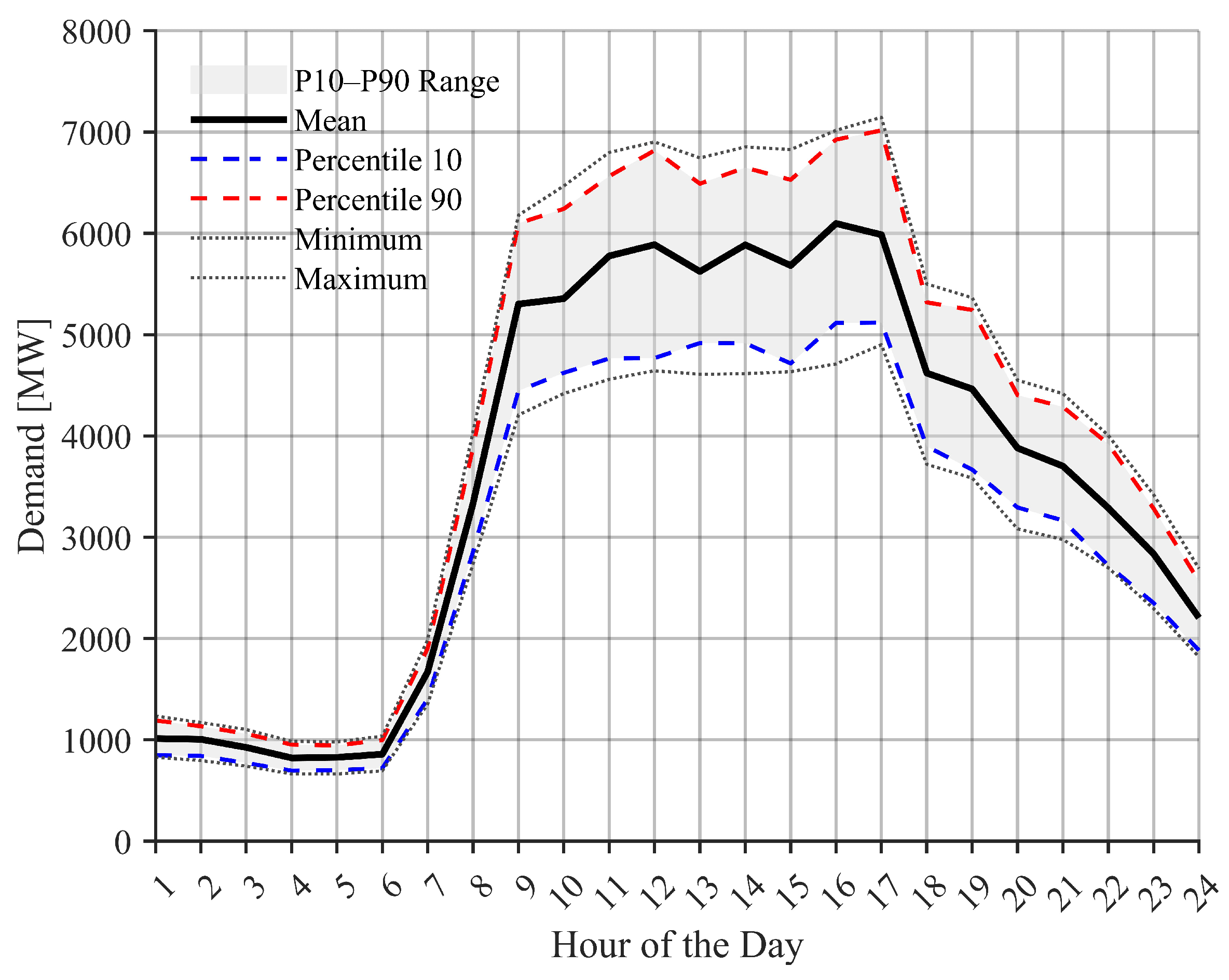

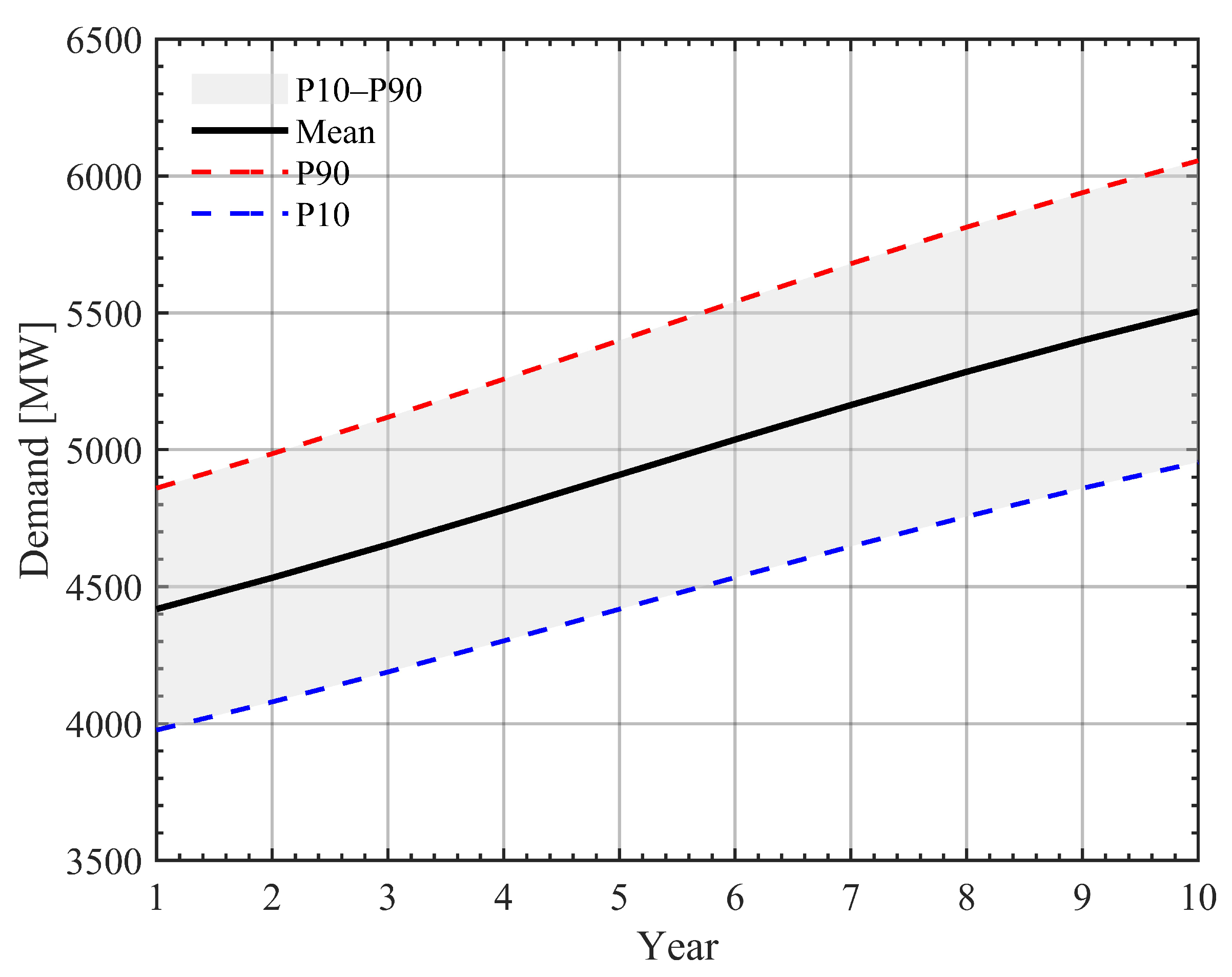

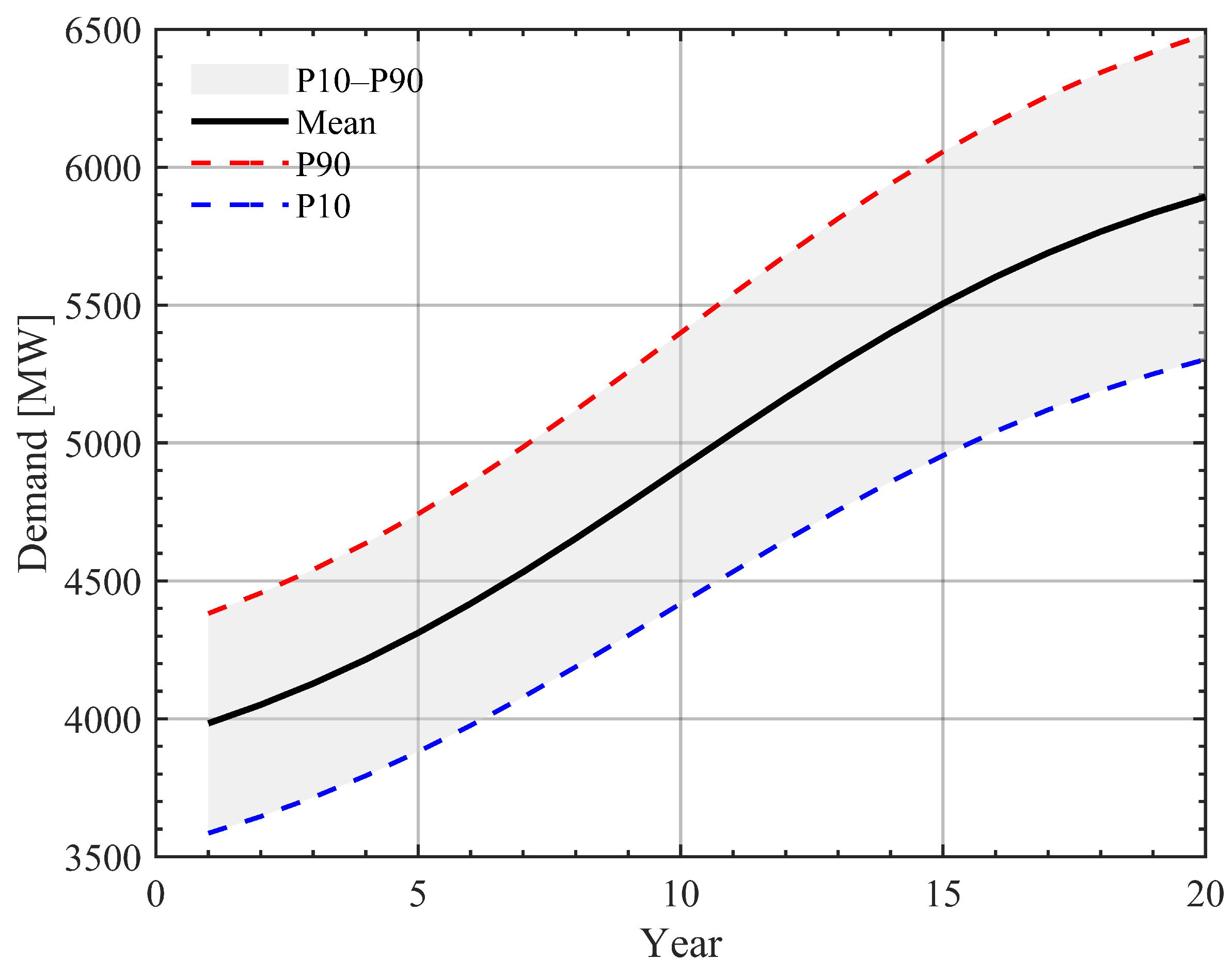

3.2. Demand Variability

3.2.1. Phase 1: Problem Diagnosis

3.2.2. Phase 2: Strategy Definition

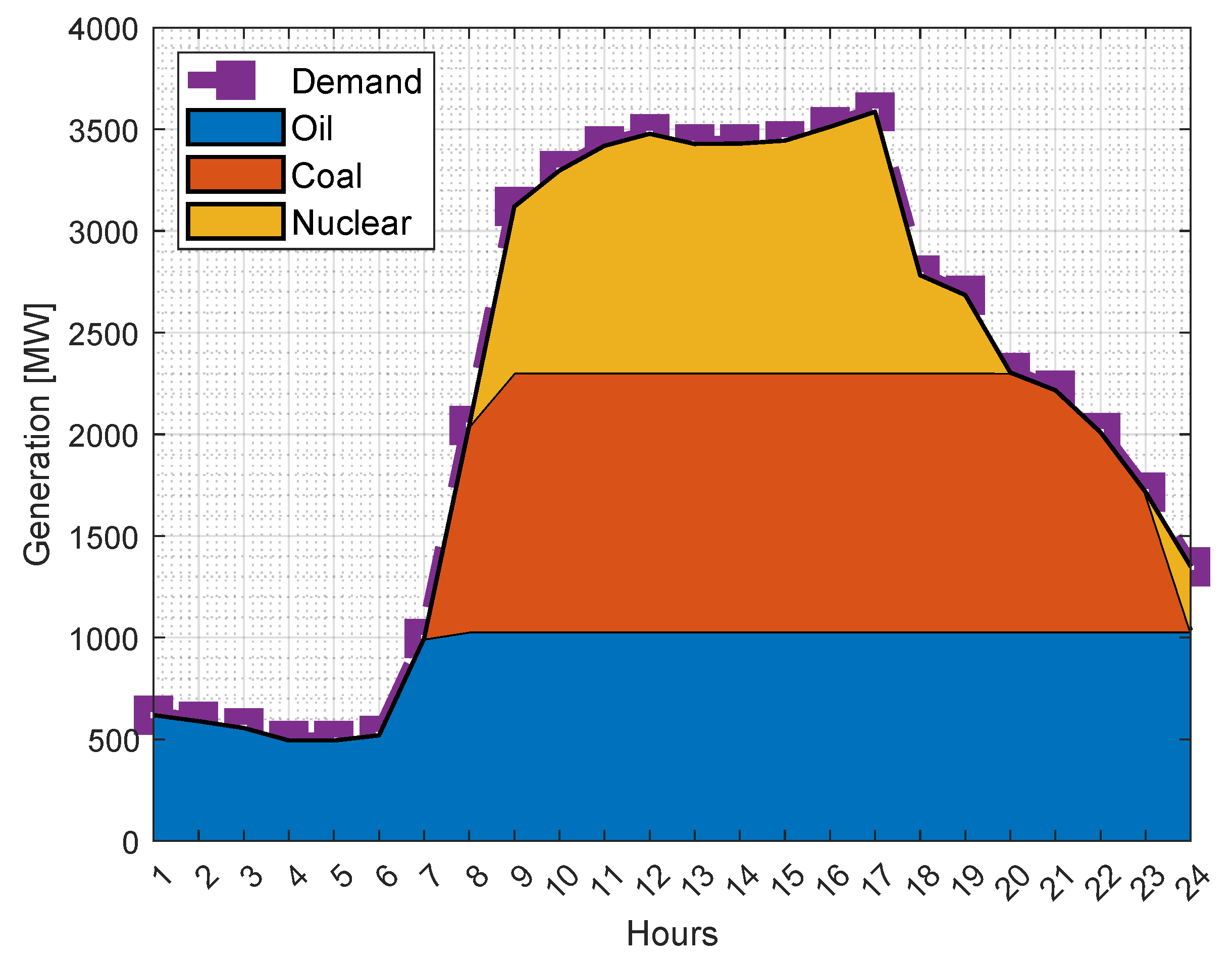

3.2.3. Case Study

| Fuel | Technology | Cost [$/MWh] |

FOM [$/MW] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil | Combustion turbine | 10.22 | 409 |

| Steam turbine | - | - | |

| Coal | Steam turbine | 24.52 | 1154 |

| Water | Nuclear steam | 54.84 | 2117 |

| Water | Hydraulic turbine | 0.92 | 1535 |

| Wind | Wind turbine | 60 | 1477 |

| Fuel | Technology | Cost [$/MWh] |

VOM [$/MWh] |

Fuel [$/MWh] |

ElecT [$/MWh] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil | Combustion turbine | 4.09 | 14.8 | 16.06 | 1.3 |

| Steam turbine | - | - | - | - | |

| Coal | Steam turbine | 3.07 | 40 | - | 0.8 |

| Water | Nuclear steam | 0.43 | 0.4 | - | - |

| Water | Hydraulic turbine | 0.003 | - | - | - |

| Wind | Wind turbine | 26.67 | - | - | - |

4. Results Analysis

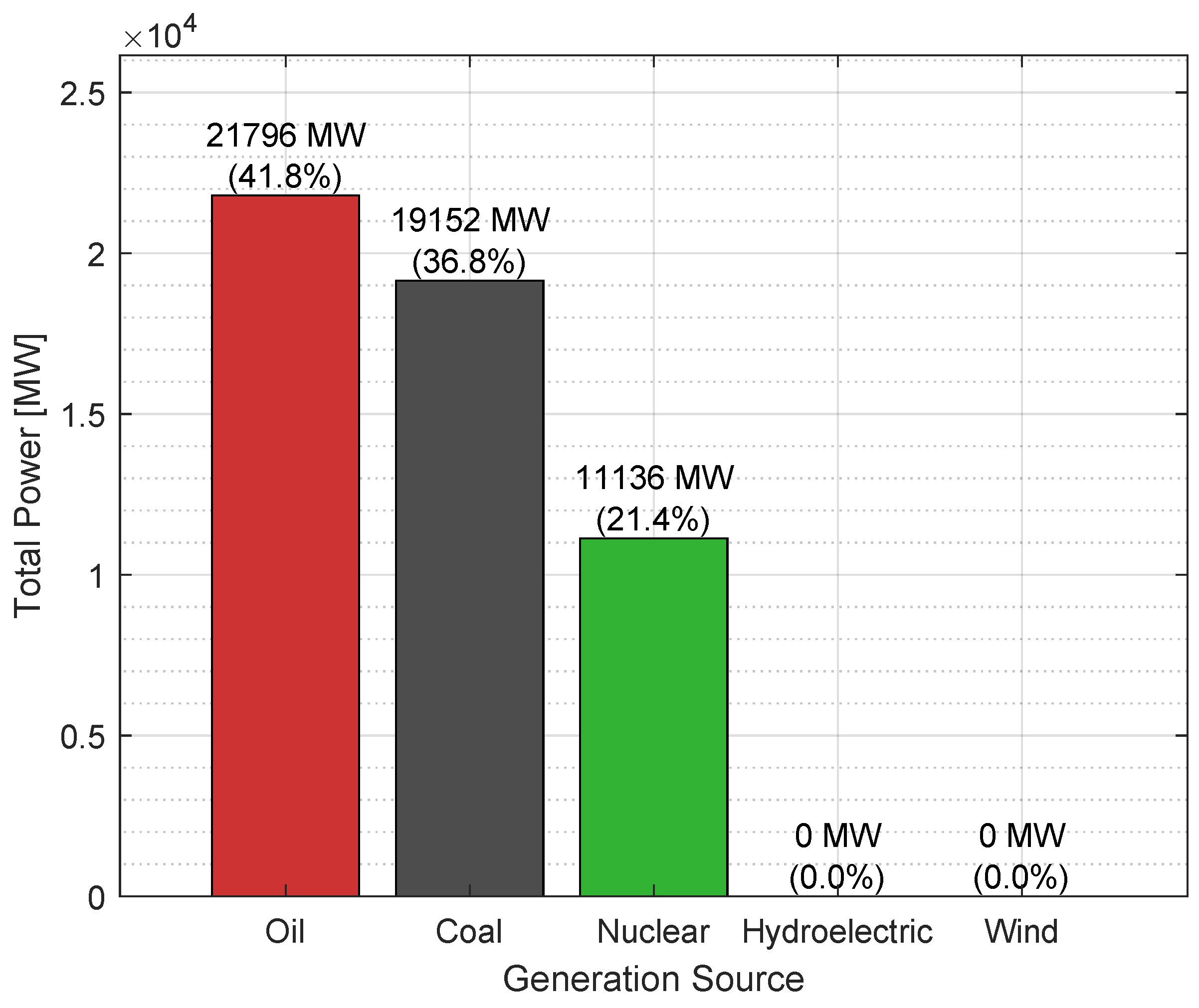

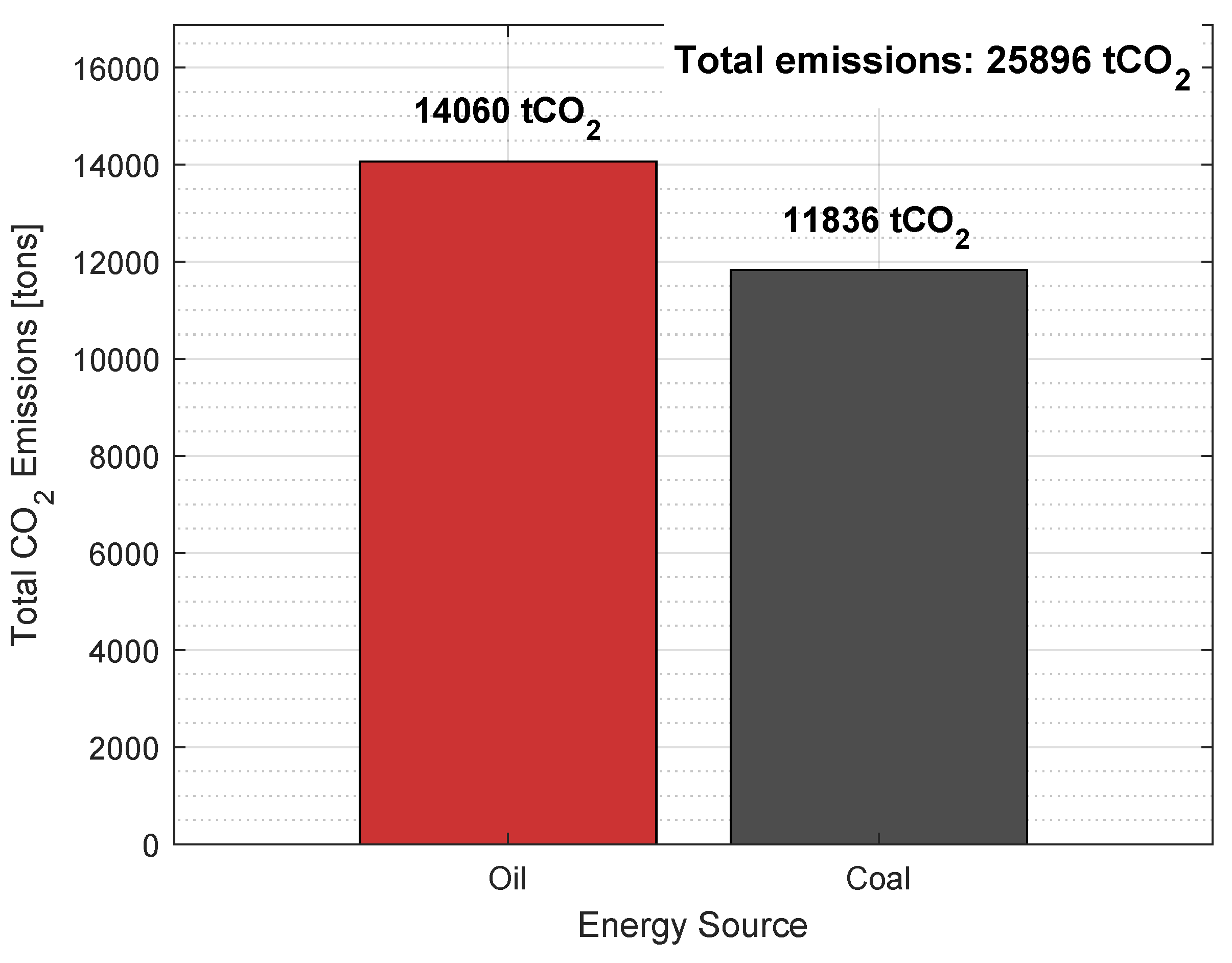

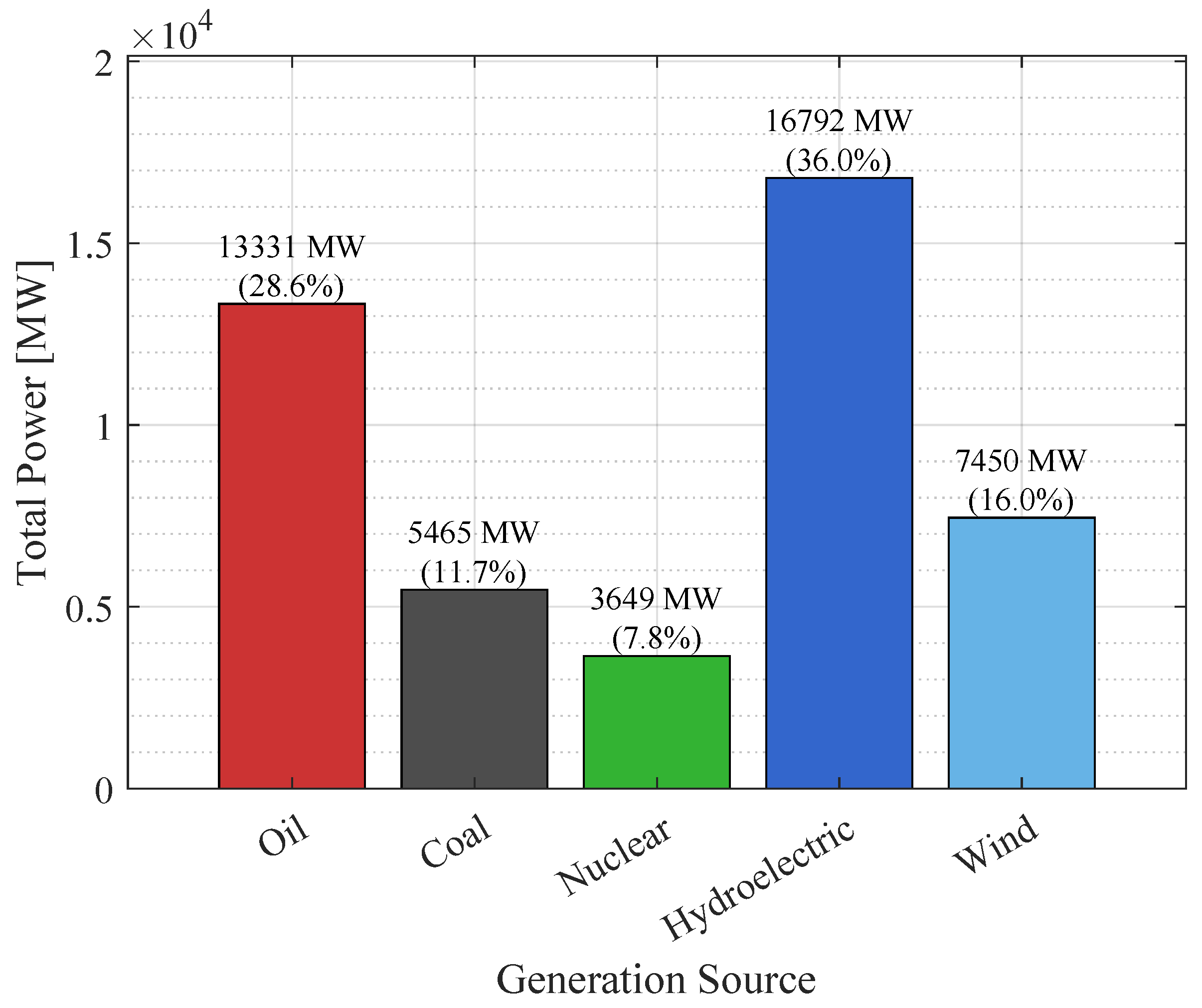

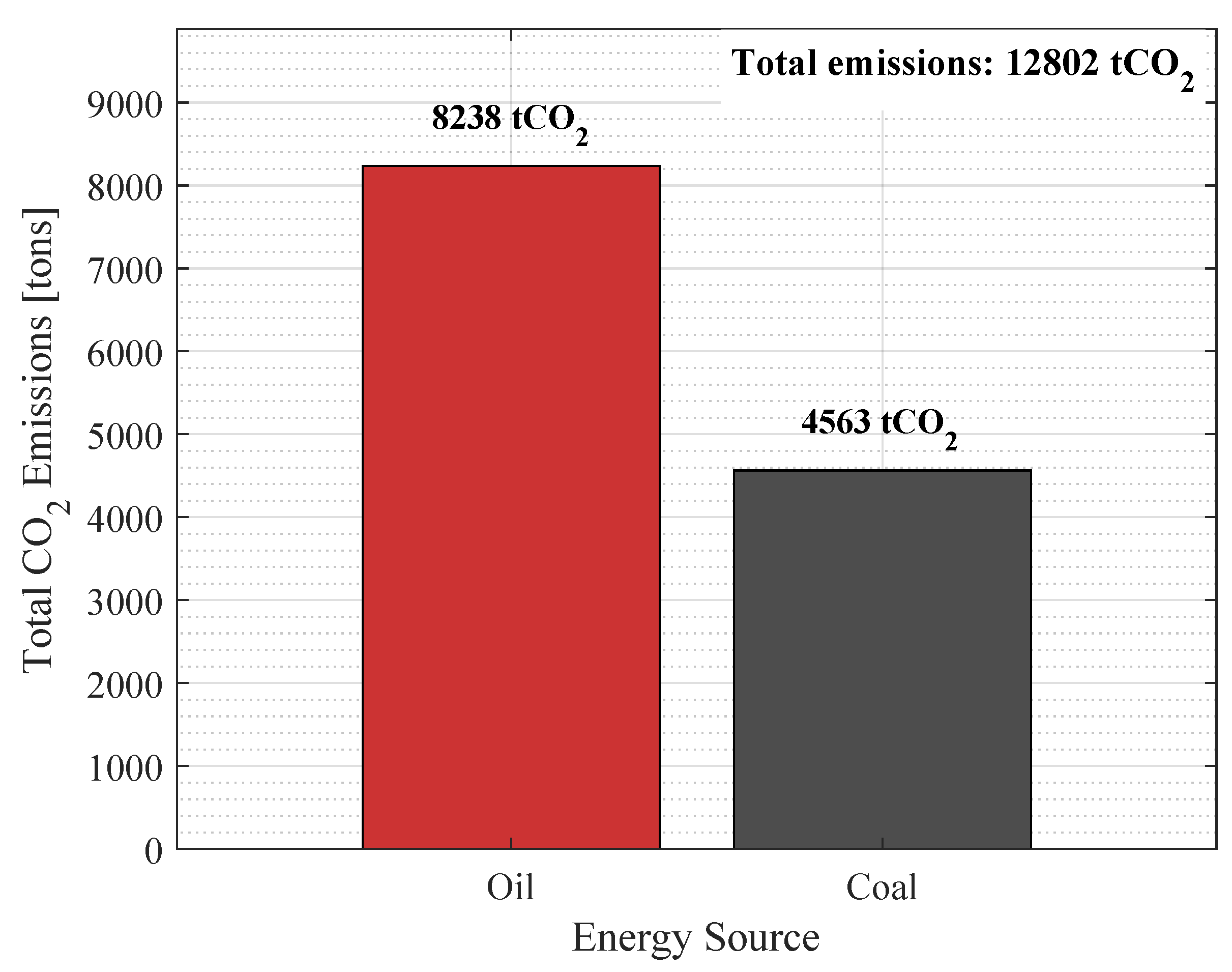

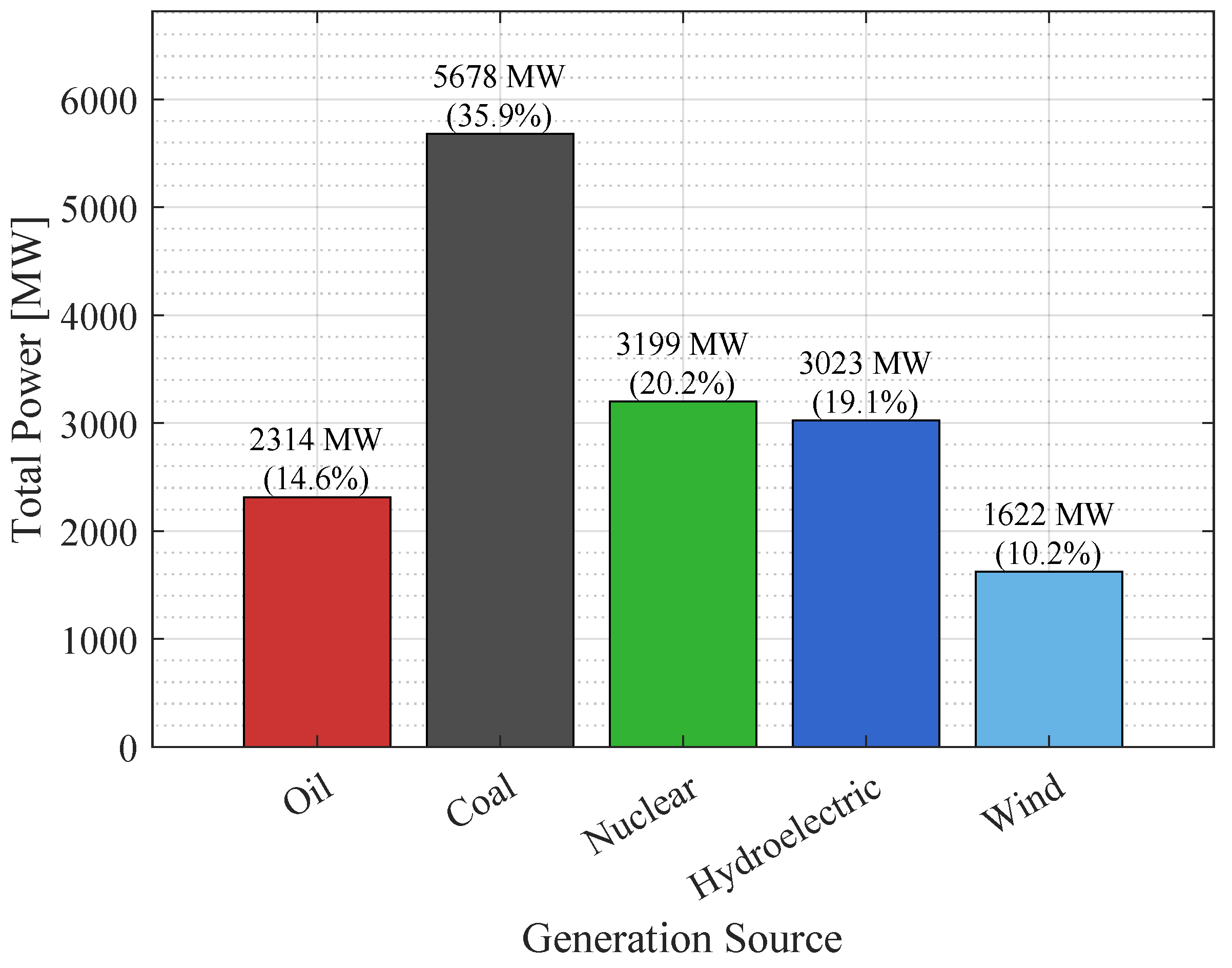

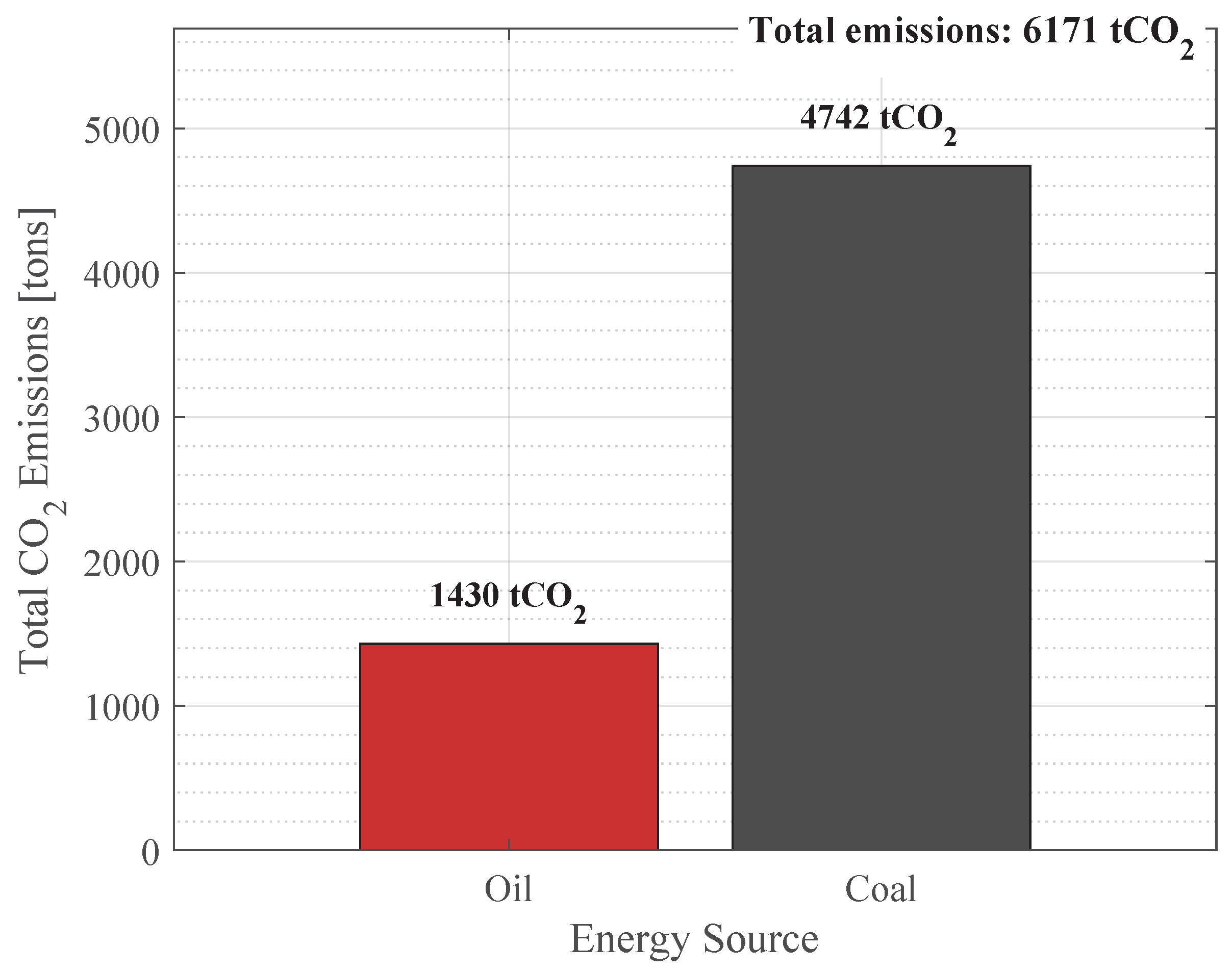

4.1. Current-Situation Analysis

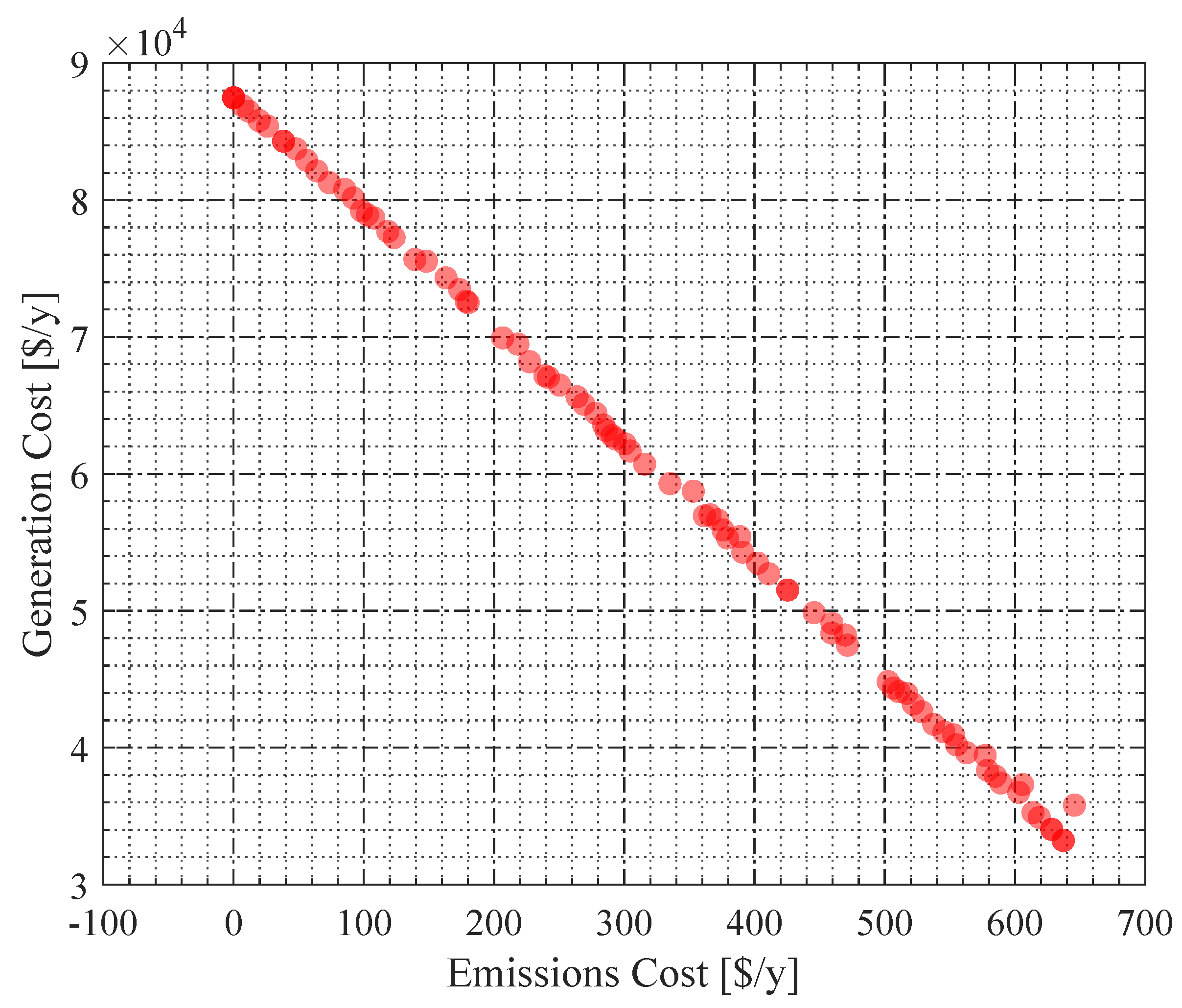

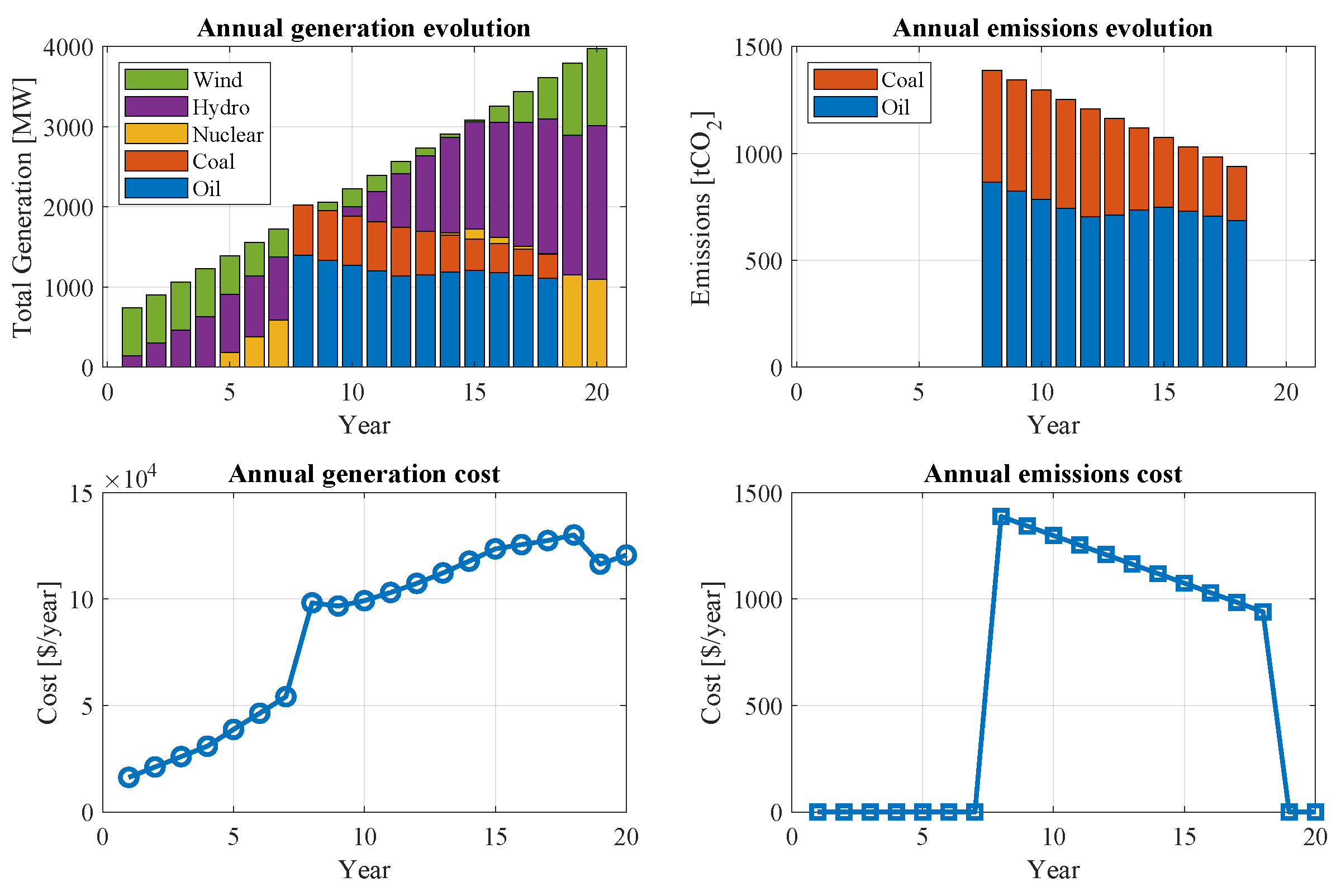

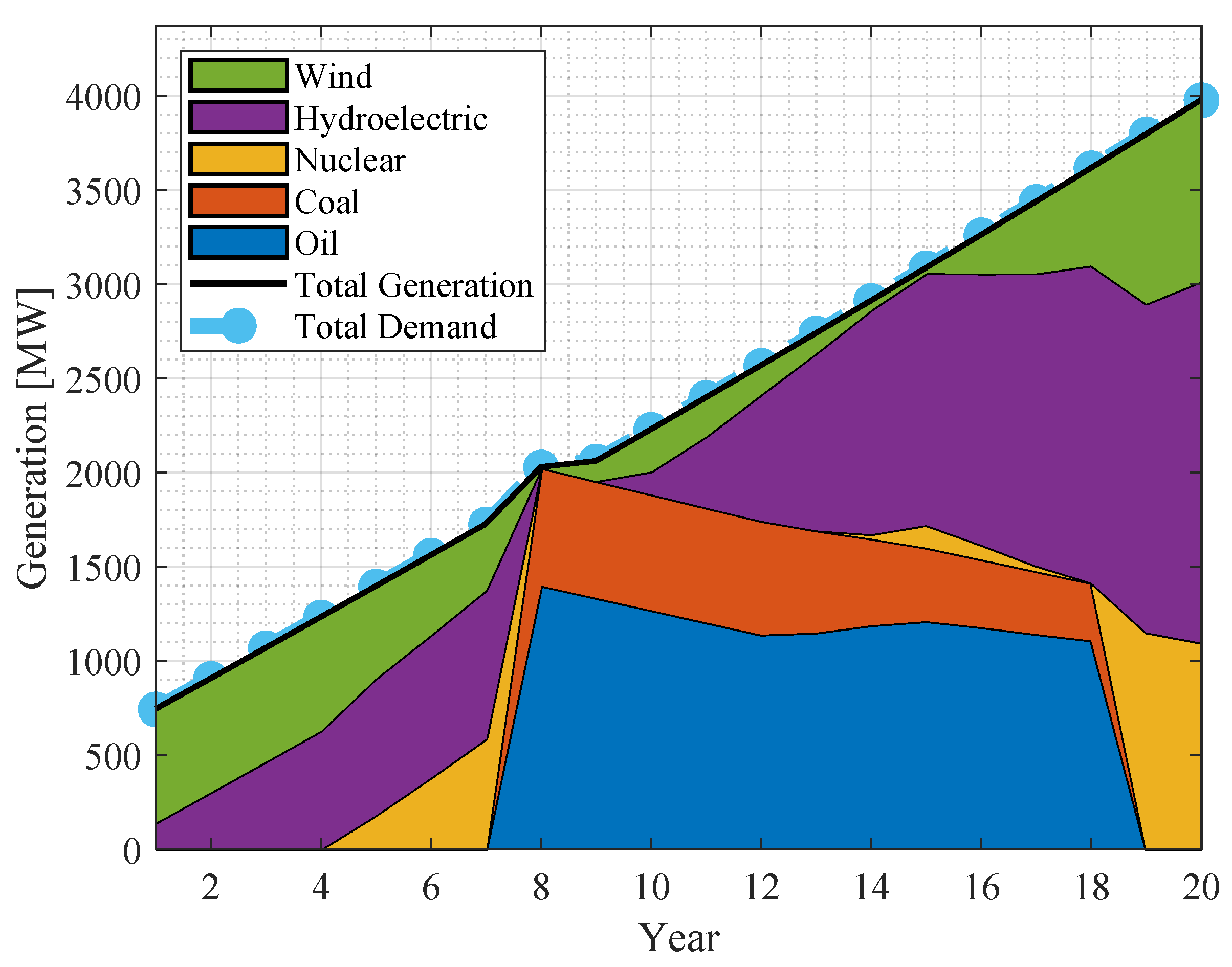

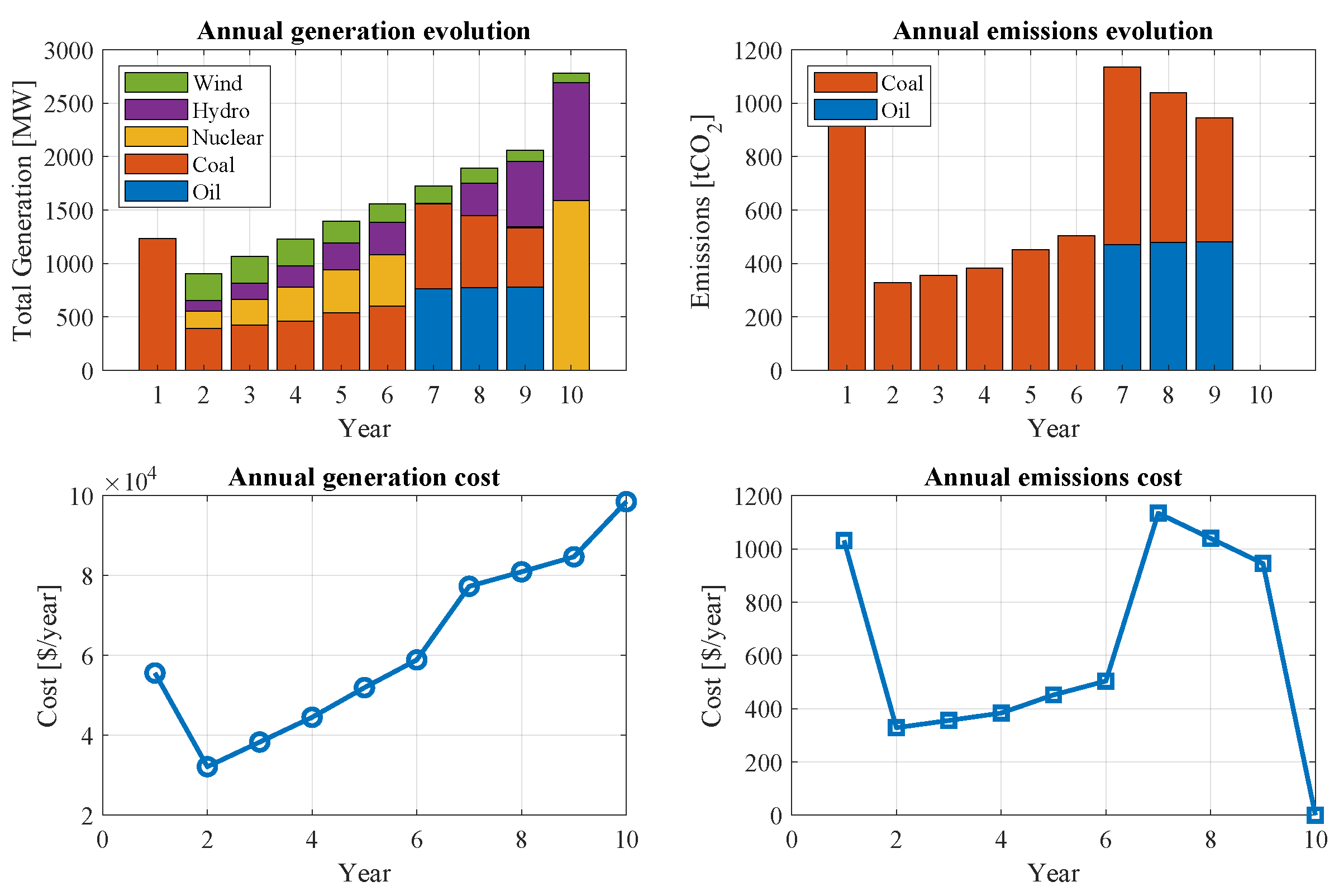

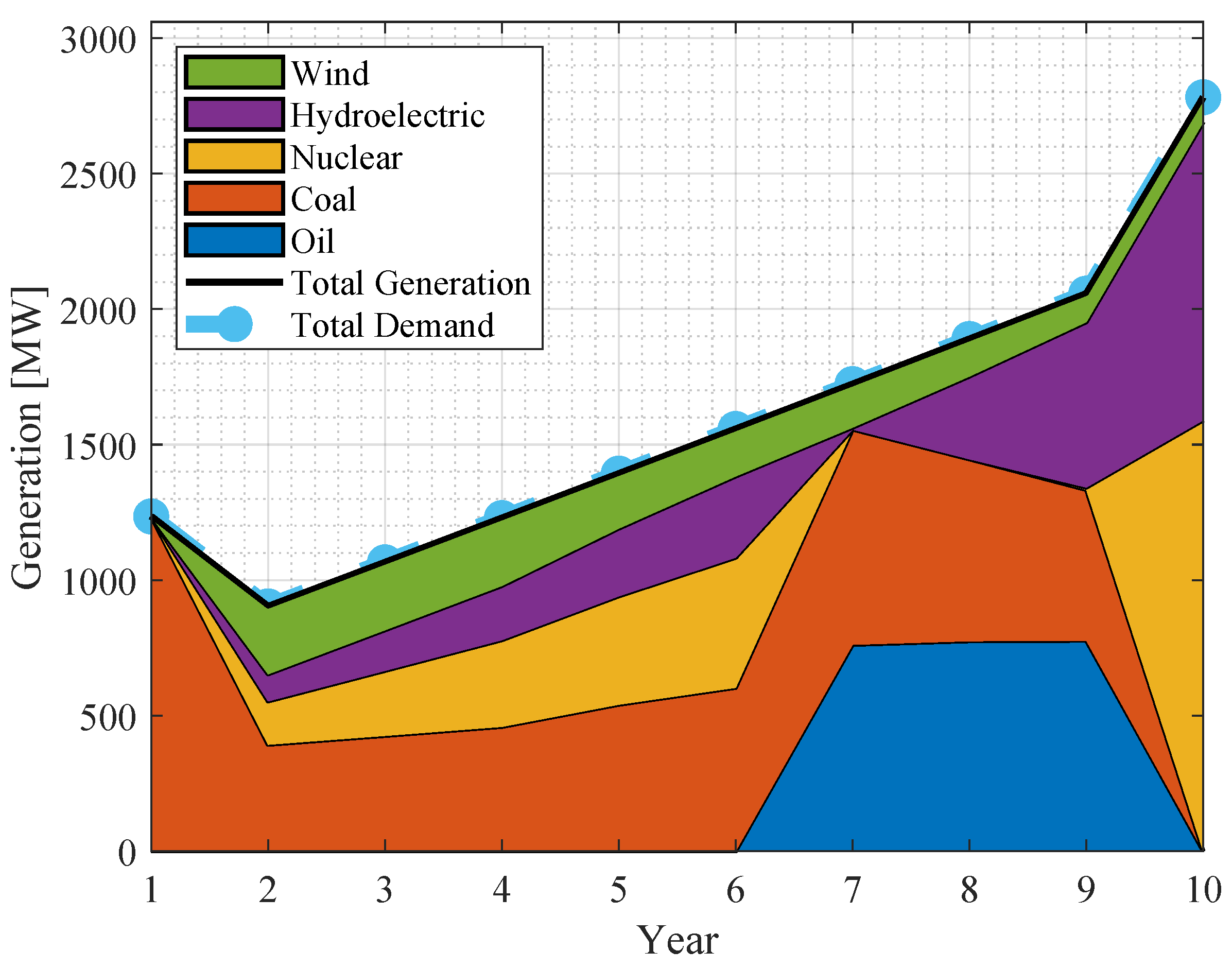

4.2. Gradual Emission Reduction Analysis

4.3. Accelerated Emission Reduction Analysis

4.4. Phase 4: Evaluation and Validation of the Energy Transition

4.4.1. Emission Reduction Evaluation

4.4.2. Cost Validation

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| ARMA | AutoRegressive Moving Average |

| BRP | Balance Responsible Party |

| CELEC EP | Corporación Eléctrica del Ecuador |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| DOD | Depth of Discharge |

| DR | Demand Response |

| DSO | Distribution System Operator |

| ECEC | Electric System Carbon Emissions |

| EECC | Expected Cost of Unserved Energy |

| EGSC | Electric System Generation Cost |

| ELRC | Load Response Cost |

| EMF | Electromotive Force |

| HRES | Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| MCI | Internal Combustion Engine |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| MVA | Megavolt-ampere |

| MW | Megawatt |

| MWh | Megawatt-hour |

| NOCT | Nominal Operating Cell Temperature |

| PLM | Programación Lineal Mixta |

| RD | Demand Response |

| SEP | Power Electric System |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| TOU | Time of Use |

| TSO | Transmission System Operator |

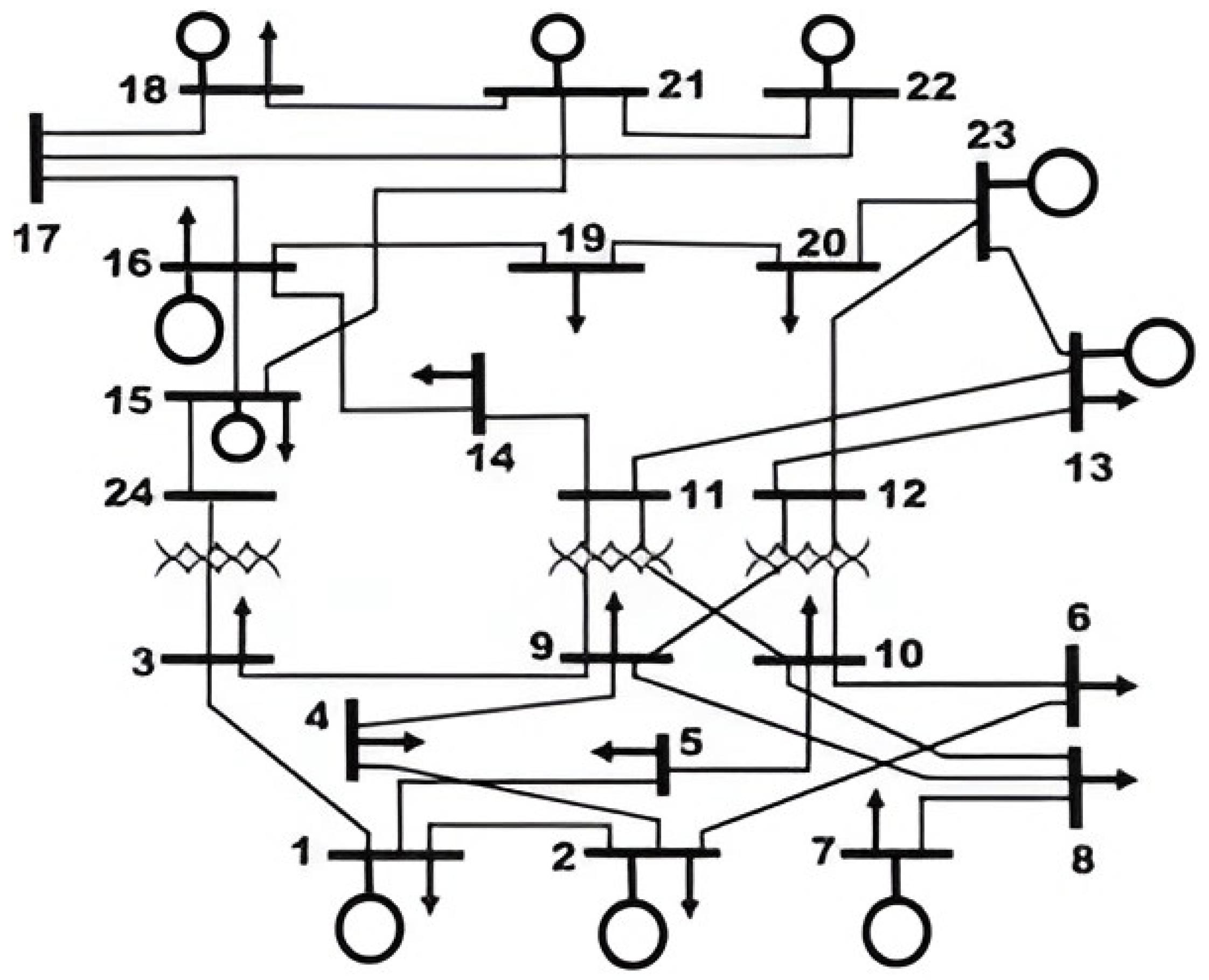

Appendix A. Technical Data of the Test System

| Unit # | Node | Pmaxi [MW] |

Pmini [MW] |

R+i [MW] |

R-i [MW] |

RUi [MW/h] |

RDi [MW/h] |

UT [h] |

DT [h] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 152 | 30.4 | 40 | 40 | 120 | 120 | 8 | 4 |

| 2 | 2 | 152 | 30.4 | 40 | 40 | 120 | 120 | 8 | 4 |

| 3 | 7 | 350 | 75 | 70 | 70 | 350 | 350 | 8 | 8 |

| 4 | 13 | 591 | 206.85 | 180 | 180 | 240 | 240 | 12 | 10 |

| 5 | 15 | 60 | 12 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 4 | 2 |

| 6 | 15 | 155 | 54.25 | 30 | 30 | 155 | 155 | 8 | 8 |

| 7 | 16 | 155 | 54.25 | 30 | 30 | 155 | 155 | 8 | 8 |

| 8 | 18 | 400 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 280 | 280 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | 21 | 400 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 280 | 280 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | 22 | 300 | 300 | 0 | 0 | 300 | 300 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 23 | 310 | 108.5 | 60 | 60 | 180 | 180 | 8 | 8 |

| 12 | 23 | 350 | 140 | 40 | 40 | 240 | 240 | 8 | 8 |

| From | To | Reactance [p.u.] |

Capacity [MVA] |

From | To | Reactance [p.u.] |

Capacity [MVA] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0.0146 | 175 | 11 | 13 | 0.0488 | 500 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.2253 | 175 | 11 | 14 | 0.0426 | 500 |

| 1 | 5 | 0.0907 | 350 | 12 | 13 | 0.0488 | 500 |

| 2 | 4 | 0.1356 | 175 | 12 | 23 | 0.0985 | 500 |

| 2 | 6 | 0.2050 | 175 | 13 | 23 | 0.0884 | 500 |

| 3 | 24 | 0.0840 | 400 | 14 | 16 | 0.0110 | 500 |

| 4 | 9 | 0.2550 | 400 | 15 | 16 | 0.0172 | 500 |

| 5 | 10 | 0.0940 | 350 | 16 | 17 | 0.0920 | 500 |

| 6 | 10 | 0.0642 | 350 | 16 | 21 | 0.0529 | 500 |

| 7 | 8 | 0.0652 | 250 | 17 | 22 | 0.0233 | 500 |

| 8 | 9 | 0.1762 | 250 | 18 | 21 | 0.0669 | 500 |

| 9 | 10 | 0.0840 | 400 | 19 | 20 | 0.0203 | 1000 |

| 10 | 11 | 0.0840 | 400 | 22 | 23 | 0.0355 | 500 |

| 10 | 12 | 0.0840 | 400 | 21 | 22 | 0.0692 | 500 |

| Hour | System demand [MW] |

Hour | System demand [MW] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1775.835 | 13 | 2517.975 |

| 2 | 1669.815 | 14 | 2517.975 |

| 3 | 1590.3 | 15 | 2464.965 |

| 4 | 1563.795 | 16 | 2464.965 |

| 5 | 1563.795 | 17 | 2623.995 |

| 6 | 1590.3 | 18 | 2650.5 |

| 7 | 1961.37 | 19 | 2650.5 |

| 8 | 2279.43 | 20 | 2544.48 |

| 9 | 2517.975 | 21 | 2411.995 |

| 10 | 2544.48 | 22 | 2199.915 |

| 11 | 2544.48 | 23 | 1934.865 |

| 12 | 2517.975 | 24 | 1669.815 |

| Load # | Node | % of system load | Load # | Node | % of system load |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 3.8 | 10 | 10 | 6.8 |

| 2 | 2 | 3.4 | 11 | 13 | 9.3 |

| 3 | 3 | 6.3 | 12 | 14 | 6.8 |

| 4 | 4 | 2.6 | 13 | 15 | 11.1 |

| 5 | 5 | 2.5 | 14 | 16 | 3.5 |

| 6 | 6 | 4.8 | 15 | 18 | 11.7 |

| 7 | 7 | 4.4 | 16 | 19 | 6.4 |

| 8 | 8 | 6.0 | 17 | 20 | 4.5 |

| 9 | 9 | 6.1 |

References

- Fu, P.; Pudjianto, D.; Zhang, X.; Strbac, G. Evaluating Strategies for Decarbonising the Transport Sector in Great Britain. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Milan PowerTech. IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Herenčić, L.; Melnjak, M.; Capuder, T.; Andročec, I.; Rajšl, I. Techno-economic and environmental assessment of energy vectors in decarbonization of energy islands. Energy Conversion and Management 2021, 236, 114064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Li, S.; Li, H. Large-scale Offshore Wind Farm Electrical Collector System Planning: A Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Approach. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 5th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1248–1253. [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, M.; Fioriti, D.; Berizzi, A.; Poli, D. Multi-Year Planning of a Rural Microgrid Considering Storage Degradation. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2021, 36, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornand, B.; Girardin, L.; Belfiore, F.; Robineau, J.L.; Bottallo, S.; Maréchal, F. Investment Planning Methodology for Complex Urban Energy Systems Applied to a Hospital Site. Frontiers in Energy Research 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.; Mao, Y.; Siebers, P.O. Optimising Decarbonisation Investment for Firms towards Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonthu, R.K.; Aguilera, R.P.; Pham, H.; Phung, M.D.; Ha, Q.P. Energy Cost Optimization in Microgrids Using Model Predictive Control and Mixed Integer Linear Programming. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1113–1118. [CrossRef]

- Uberti, V.A.; Adeyanju, O.M.; Bernardon, D.P.; Abaide, A.R.; Pereira, P.R.; Prade, L.R. Linear Programming Applied to Expansion Planning of Power Transmission System. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference - Latin America (ISGT Latin America). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, C.; Rider, M.J.; Lyra, C. Optimized Integration of a Set of Small Renewable Sources Into a Bulk Power System. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2021, 36, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Furtwängler, C. Managing combined power and heat portfolios in sequential spot power markets under uncertainty. SSRN Electronic Journal 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, A.; Poyrazoglu, G.; Ahmed, E.E.E. Capacity Planning for Forming Sustainable and Cost-Effective Nanogrids. In Proceedings of the 2023 13th International Conference on Power, Energy and Electrical Engineering (CPEEE). IEEE, 2023, pp. 217–222. [CrossRef]

- Pinzon, J.A.; Vergara, P.P.; da Silva, L.C.P.; Rider, M.J. Optimal Management of Energy Consumption and Comfort for Smart Buildings Operating in a Microgrid. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2019, 10, 3236–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar-Dominguez, O.D.; Pourakbari-Kasmaei, M.; Mantovani, J.R.S. Robust Short-Term Electrical Distribution Network Planning Considering Simultaneous Allocation of Renewable Energy Sources and Energy Storage Systems. In Robust Optimal Planning and Operation of Electrical Energy Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 145–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnaoui, A.; Omari, A.; Azzouz, Z.E. Optimization of Building Energy based on Mixed Integer Linear Programming. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Advanced Electrical Engineering (ICAEE). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.A.A.; López, J.C.; Arias, N.B.; Rider, M.J.; da Silva, L.C.P. An optimal stochastic energy management system for resilient microgrids. Applied Energy 2021, 300, 117435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerchio, M.; Gullì, F.; Repetto, M.; Sanfilippo, A. Hybrid Energy Network Management: Simulation and Optimisation of Large Scale PV Coupled with Hydrogen Generation. Electronics 2020, 9, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, D.V.; Martinez-Rico, J.; Carrion, M.; Cañas-Carreton, M. A Computationally Efficient Formulation for a Flexibility Enabling Generation Expansion Planning. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2023, 14, 2723–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basto-Gil, J.; Maldonado-Cardenas, A.; Montoya, O. Optimal Selection and Integration of Batteries and Renewable Generators in DC Distribution Systems through a Mixed-Integer Convex Formulation. Electronics 2022, 11, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, L.; Gabrielli, P.; Boldrini, A.; Kramer, G.J.; Gazzani, M. On the role of H2 storage and conversion for wind power production in the Netherlands. In Proceedings of the Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, 2019, pp. 1627–1632. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, F.; Brown, T. Heuristics for Transmission Expansion Planning in Low-Carbon Energy System Models. In Proceedings of the 2019 16th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Conejo, A.J.; Liu, P.; Omell, B.P.; Siirola, J.D.; Grossmann, I.E. Mixed-integer linear programming models and algorithms for generation and transmission expansion planning of power systems. European Journal of Operational Research 2022, 297, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallégol, A.; Khannoussi, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Lacarrière, B.; Meyer, P. Handling Non-Linearities in Modelling the Optimal Design and Operation of a Multi-Energy System. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleschutz, M.; Bohlayer, M.; Braun, M.; Murphy, M.D. Demand Response Analysis Framework (DRAF): An Open-Source Multi-Objective Decision Support Tool for Decarbonizing Local Multi-Energy Systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, V.; Driha, O.M.; Sevilla-Jiménez, M. Effects of renewables deployment in the Spanish electricity generation sector. Utilities Policy 2019, 56, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, M. Sharpening Focus on a Global Low-Carbon Future. Joule 2017, 1, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth, A.; Gençer, E. Highlighting regional decarbonization challenges with novel capacity expansion model. Cleaner Energy Systems 2023, 5, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, A.; Akkaya, M. Contribution of Renewable Energy Potential to Sustainable Employment. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2016, 229, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercure, J.F.; Pollitt, H.; Bassi, A.M.; Viñuales, J.E.; Edwards, N.R. Modelling complex systems of heterogeneous agents to better design sustainability transitions policy. Global Environmental Change 2016, 37, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdiwansyah.; Mahidin.; Husin, H.; Nasaruddin.; Zaki, M.; Muhibbuddin. A critical review of the integration of renewable energy sources with various technologies. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Agencia de Regulación y Control de Energía y Recursos Naturales No Renovables. Estadística Anual y Multianual del Sector Eléctrico Ecuatoriano. Technical report, 2023.

- Chiavenato, I.; Sapiro, A. Planeación Estratégica. Fundamentos y aplicaciones; McGRAW-HILL, 2017.

- Mintzberg, H.; Ahlstrand, B.; Lampel, J. Safari a la estrategia. Una visita guiada por la jungla del management estratégico; Granica, 2024.

- Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo. Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2017-2021-Toda una Vida. Technical report, 2017.

- Franke, G.; Schneider, M.; Weitzel, T.; Rinderknecht, S. Stochastic Optimization Model for Energy Management of a Hybrid Microgrid using Mixed Integer Linear Programming. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 12948–12955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, R.A.; López-Lezama, J.M. Power system restoration using a mixed integer linear programming model. Información Tecnológica 2021, 31, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosic, A.; Stadler, M.; Mansoor, M.; Zellinger, M. Mixed-integer linear programming based optimization strategies for renewable energy communities. Energy 2021, 237, 121559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda Sosa, J.R. Diseño de un modelo de planeación estratégica soportado en el sistema gerencial de Kaplan y Norton, aplicable a las mipymes de reciente creación originadas como proyectos formales de emprendimiento en Bogotá. Master’s thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2014.

- Páez, B. Análisis de los escenarios respecto al crecimiento de las energías no convencionales en el Ecuador para el año 2030. Master’s thesis, Escuela Politécnica Nacional, 2023.

- Adefarati, T.; Bansal, R.C. Integration of renewable distributed generators into the distribution system: A review. IET Renewable Power Generation 2016, 10, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haegel, N.; Kurtz, S. Global Progress Toward Renewable Electricity: Tracking the Role of Solar. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2021, 11, 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuma, J.; Ashley, D. Runoff estimates into the Weija reservoir and its implications for water supply to the Accra area, Ghana. Journal of Urban and Environmental Engineering 2013, 2, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Energy and exergy analyses of S–CO2 coal-fired power plant with reheating processes. Energy 2020, 211, 118651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CENACE. Informe Anual CENACE. Technical report, 2018.

- Ostman, F.; Toivonen, H.T. Adaptive Cylinder Balancing of Internal Combustion Engines. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2011, 19, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.; Silva, C. Combustion of Emulsions in Internal Combustion Engines and Reduction of Pollutant Emissions in Isolated Electricity Systems. Energies 2022, 15, 8053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Pandey, K.M. Static Structural and Modal Analysis of Gas Turbine Blade. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2017, 225, 012102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukur, N.; Osigwe, E.O. A model for booster station matching of gas turbine and gas compressor power under different ambient conditions. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, Z.N.; Papić, L.R.; Milovanović, S.Z.; Janičić Milovanović, V.Z.; Dumonjić-Milovanović, S.R.; Branković, D.L. Qualitative analysis in the reliability assessment of the steam turbine plant. In The Handbook of Reliability, Maintenance, and System Safety through Mathematical Modeling; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 179–313. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Kim, B.G.; Kwon, S.K. Efficient Depth Data Coding Method Based on Plane Modeling for Intra Prediction. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 29153–29164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazas-Niño, F.A.; Ortiz-Pimiento, N.R.; Montes-Páez, E.G. National energy system optimization modelling for decarbonization pathways analysis: A systematic literature review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 162, 112406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia Azcona, K.; Stendorf Sorensen, S.; Molina Costa, P.; Flores Abascal, I. Smart zero carbon city: key factors towards smart urban decarbonization. DYNA 2019, 94, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Grenville, J.; Buckle, S.J.; Hoskins, B.J.; George, G. Climate Change and Management. Academy of Management Journal 2014, 57, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaesmaeeli, H.; Elkamel, A.; Douglas, P.L.; Croiset, E.; Gupta, M. A multi-period optimization model for energy planning with CO2 emission consideration. Journal of Environmental Management 2010, 91, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alstone, P.; Gershenson, D.; Kammen, D.M. Decentralized energy systems for clean electricity access. Nature Climate Change 2015, 5, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Guo, J.; Liu, J. An economic load dispatch of wind-thermal power system by using virtual power plants. In Proceedings of the Chinese Control Conference, 2016, pp. 8704–8709. [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Xie, J.; Yue, D.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, L. A distributed gradient algorithm based economic dispatch strategy for virtual power plant. In Proceedings of the Chinese Control Conference, 2016, pp. 7826–7831. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; et al. Techno economic analysis of a wind-photovoltaic-biomass hybrid renewable energy system for rural electrification: A case study of Kallar Kahar. Energy 2018, 148, 208–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpooya, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Ahmadi, E. Techno-economic-environmental study of hybrid power supply system: A case study in Iran. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2018, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, G.B.A. Óptima Respuesta a la Demanda y Despacho Económico de Energía Eléctrica en Micro Redes Basados en Árboles de Decisión Estocástica. Master’s thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, 2018.

- Moyón, R.A.F. Planeación de Despacho Óptimo de Plantas Virtuales de Generación en Sistemas Eléctricos de Potencia mediante Flujos Óptimos de Potencia AC. Master’s thesis, Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, 2020.

- Hosseinalizadeh, R.; Shakouri, H.; Amalnick, M.S.; Taghipour, P. Economic sizing of a hybrid (PV–WT–FC) renewable energy system (HRES) for stand-alone usages by an optimization-simulation model: Case study of Iran. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 54, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shamma’a, A.A.; Alturki, F.A.; Farh, H.M.H. Techno-economic assessment for energy transition from diesel-based to hybrid energy system-based off-grids in Saudi Arabia. Energy Transitions 2020, 4, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, C.; Chungpaibulpatana, S. Techno-economic analysis of hybrid system for rural electrification in Cambodia. Energy Procedia 2017, 138, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, B.; Félix, G.T.; Miguel, A.R. Model predictive Control of Microgrids; 2019.

- Murnane, M.; Ghazel, A. A Closer Look at State of Charge (SOC) and State of Health (SOH) Estimation Techniques for Batteries. Technical report, 2017.

- Vahid-Ghavidel, M.; Javadi, M.S.; Gough, M.; Santos, S.F.; Shafie-Khah, M.; Catalão, J.P.S. Demand response programs in multi-energy systems: A review. Energies 2020, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.; Vettikalladi, H.; Song, S.H.; Choi, H.J. Implementation of a demand-side management solution for South Korea’s demand response program. Applied Sciences 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Billanes, J.D.; Jørgensen, B.N. Aggregation potentials for buildings-Business models of demand response and virtual power plants. Energies 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprinos, I.; Hatziargyriou, N.D.; Kokos, I.; Dimeas, A.D. Making Demand Response a Reality in Europe: Policy, Regulations, and Deployment Status. IEEE Communications Magazine 2016, 54, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, W.C.; Teh, J.; Lai, C.M. Integration of Wind and Demand Response for Optimum Generation Reliability, Cost and Carbon Emission. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 183606–183618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plants | Energy Sources | Nominal Capacity [MW] |

Effective Capacity [MW] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydropower | Renewable | 5,106.85 | 5,072.26 |

| Photovoltaic | Renewable | 27.70 | 26.80 |

| Wind | Renewable | 21.20 | 21.20 |

| Biogas | Renewable | 8.40 | 7.25 |

| Biomass | Renewable | 144.40 | 136.45 |

| Thermal | Non-renewable | 3,426.15 | 2,836.90 |

| GUANGOPOLO II THERMAL POWER PLANT | |

|---|---|

| SUPERVISOR: | CELEC-EP/TERMOPICHINCHA |

| TECHNOLOGY TYPE: | Thermal Plant |

| GENERAL DATA | |

| Country | Ecuador |

| Province | Pichincha |

| City | Quito |

| Location | X X |

| TECHNICAL DATA | |

| Installed Capacity: | 52.38 MW |

| Type: | ICE |

| Number of Units: | 7 Units |

| Capacity per Unit: | 8.73 MW |

| Fuel Type: | Diesel–Bunker |

| Voltage: | - |

| Annual Energy: | 582.58 GWh |

| Plant Factor: | 3.82% |

| Engine: | |

| Type: | MITSUBISHI-MAN |

| Performance: | - |

| Rating: | 18 |

| RPM: | 5,200 kW |

| Quantity: | 400 |

| Frequency: | 60 Hz |

| Number of Phases: | 3 |

| Number of Poles: | - |

| Power Factor: | 0.80 |

| Engine: | |

| Type: | WÄRTSILÄ DIESEL |

| Performance: | 8SW28 |

| Rating: | 17 |

| RPM: | 1,980 kW |

| Quantity: | 900 |

| Frequency: | 60 Hz |

| MACHALA II THERMAL POWER PLANT | |

|---|---|

| SUPERVISOR: | CELEC-EP/TERMOMACHALA |

| TECHNOLOGY TYPE: | Gas Turbine |

| GENERAL DATA | |

| Country | Ecuador |

| Province | El Oro |

| City | Machala |

| Location | X X |

| TECHNICAL DATA | |

| Installed Capacity: | 252 MW |

| Type: | Gas Turbine (GT) |

| Number of Units: | 8 Units |

| Capacity per Unit: | 6 of 20 MW and 2 of 66 MW |

| Fuel Type: | Natural Gas |

| Voltage: | - |

| Plant Factor: | 37.50% |

| Average Energy: | 406.70 |

| Gas Turbine | |

| Type: | General Electric |

| Model: | TM2500 |

| Rating: | - |

| RPM: | 1,980 kW |

| Quantity: | 900 |

| Frequency: | 60 Hz |

| TRINITARIA THERMAL POWER PLANT | |

|---|---|

| SUPERVISOR: | CELEC-EP/ELECTROGUAYAS |

| TECHNOLOGY TYPE: | Steam Turbine Thermal Plant |

| GENERAL DATA | |

| Country | Ecuador |

| Province | Guayas |

| City | Guayaquil |

| Location | X X |

| TECHNICAL DATA | |

| Installed Capacity: | 133 MW |

| Type: | Steam Turbine (ST) |

| Number of Units: | 1 Unit |

| Capacity per Unit: | 133 MW |

| Fuel Type: | Fuel Oil #4 |

| Efficiency: | 16% |

| Voltage: | - |

| Plant Factor: | 54.10% |

| Average Energy: | 629.50 |

| Turbine | |

| Type: | DKY2-INDRI |

| Manufacturer: | ASEA BROWN BOVERI |

| Rating: | 133 kW |

| Quantity: | 1 |

| Rated Current: | 6.60 A |

| Frequency: | 60 Hz |

| Temperature: | 583 °C |

| Pressure: | 140 |

| Phases: | 3 |

| Poles: | 2 |

| Speed (RPM): | 3,600 |

| Actors | Offers | Users |

|---|---|---|

| BRP | Energy loss payments; Market access; DR incentives | Consumer |

| Aggregator | Ancillary services; Tariffs; Grid balancing services | TSO; DSO |

| Supplier/Retailer | Incentive packages and contracts for implicit DR programs; DR incentives | Consumers |

| Regulator | DR regulations; Knowledge for DR management | All actors |

| Consumer | Demand profile; Direct control; Large consumers can provide flexibility directly | Aggregator; Supplier/Retailer; DR market |

| Power System Decarbonization Process | |

| Step 1 |

Initialization Define main parameters: - Population size N - Maximum number of iterations or convergence criterion - Coefficient of variation of EECC < 5% - Parameters of genetic operators Initialize random solution population: Define binary variables: (installation of wind farm at node ) (ON/OFF status of generator at t) (activation of DR at node ) |

| Step 2 |

Evaluation of each solution in the population For each individual x in the population: Wind simulation and wind power generation: Use ARMA model for Calculate wind power output: Load modeling and demand response: Modify load curve: |

| Step 3 |

Calculation of optimization objectives Cost of Unserved Energy (EECC): Generation Cost (EGSC): Demand Response Cost (ELRC): Carbon Emissions (ECEC): |

| Continued on next page | |

| Continuation of Table 6 | |

| Step 4 |

Verification of constraints Generation-demand balance: Technical loss limit: Generation limits: Load shedding: Generator activation: Demand Response activation: |

| Step 5 |

Solution selection Identify non-dominated solutions in the population |

| Step 6 |

Fuzzy selection of the best solution For each individual x in the solution pool: For each objective : Normalize objective values Select the solution with the smallest error as optimal |

| Step 7 |

Genetic Operators Apply selection, crossover, and mutation on the solution set |

| Step 8 |

Convergence criterion If verification coefficient < 5% or iterations ≥ 100,000: Terminate algorithm Else: Update population and repeat from Step 2 |

| Step 9 |

Final result Return the solution set and the best solution |

| Step 10 | End |

| End of table | |

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| N | Population size | - |

| Wind penetration coefficients for each generator | - | |

| Percentage of load to be shifted in each load sector | - | |

| Wind speed | m/s | |

| Cut-in, rated, and cut-out wind speeds of the turbine | m/s | |

| Rated power of the wind turbine | MW | |

| Coefficients of the wind power function | - | |

| Load demand at time t | MW | |

| Power shifted by demand response | MW | |

| Set of simulation periods | - | |

| Power generated by the wind farm | MW | |

| Unserved energy losses | MW | |

| Value of Lost Load | $/MW | |

| Energy reduced by demand response | MWh | |

| Incentive cost for load reduction | $ | |

| Oil-fired generation cost | $/MWh | |

| Fixed cost of oil-fired generation | $ | |

| Energy generated with oil | MWh | |

| Oil generation emission factors | ton CO2/MWh | |

| Power generated by unit g | MW | |

| Power demanded in sector l | MW | |

| Minimum and maximum generation limits | MW |

| Fuel | Technology | Node | Capacity [MW] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil | Combustion turbine | 1 | 40 |

| 2 | 40 | ||

| Steam turbine | 7 | 300 | |

| 13 | 591 | ||

| 15 | 60 | ||

| Coal | Steam turbine | 15 | 155 |

| 16 | 155 | ||

| 23 | 660 | ||

| Water | Nuclear steam | 18 | 400 |

| 21 | 400 | ||

| Water | Hydraulic turbine | 22 | 300 |

| Fuel | Technology | CE [tonCO2/MWh] |

EC [$/tonCO2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil | Combustion turbine | 0.618 | 35 |

| Steam turbine | - | - | |

| Coal | Steam turbine | 0.743 | 35 |

| Water | Nuclear steam | 0.835 | - |

| Water | Hydraulic turbine | - | - |

| Wind | Wind turbine | - | - |

| Load type | IC [$/MWh] |

|---|---|

| Residential | 150 |

| Industrial | 13930 |

| Commercial | 12870 |

| Large consumers | 13930 |

| Agriculture | 650 |

| Government | 3460 |

| Office | 3460 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 1996 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).