1. Introduction

Bone loss of the maxilla and mandible can occur because of trauma, extractions, surgery or congenital malformations. Bone deficiency may cause issues and complications in oral restorative or rehabilitation therapies. After a tooth is extracted, a rapid bone remodeling process occurs, leading to 40-60% shrinkage in width and height of the alveolar ridge [

1]. Although most bone loss is expected in the first three months post-extraction, bone loss may continue for 2-3 years post-extraction [

2,

3]. This could endanger prosthodontic therapy and lower the edentulous site's restorability, due to the functional and esthetic deficiencies derived from volumetric bone loss [

1]. Considering the growing availability of dental implants and the interest for implant therapy, bone preservation and regeneration techniques are becoming increasingly impactful in restorative dentistry [

4]. Bone regeneration is a complex process that implies the migration and proliferation of particular cells to the healing area in order to provide the biological substrate for the growth of new tissue [

5]. To obtain an adequate volume of alveolar osseous tissue and high-quality regenerated bone, a variety of bone grafting materials are employed. Grafts including autogenous, allogenous, and xenogenous bone or alloplastic substances are used in reconstructive oral surgery [

6]. Autogenous bone remains the gold standard for bone regeneration due to their osteogenic potential, osteoinductivity and osteoconductivity [

7]. Osteoconductivity is the characteristic of xenogenous bone grafts [

6]. Allogenous bone is a material obtained from different individuals of the same species, it has osteoinductive potential thanks to residual growth factors, but it has no osteogenic potential due to sterilization and deproteinizing methods. Besides bone volume, bone quality is a very important vector for bone regeneration. Bone quality is defined by the National Institute of Health (NIH) as “the sum of all characteristics of bone that influence the bone’s resistance to fracture” [

8], being an umbrella term which encompasses bone architecture, bone turnover, bone mineralization, and micro-damage accumulation [

9]. Decreased bone quality is linked to osteoporosis, vitamin D deficiency and other conditions [

1].

Osteoporosis is a global condition that causes bone fragility by reducing bone mass and strength. Currently, the quantitative study of bone mineral density (BMD) by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) provides the basis for both osteoporosis diagnosis and fracture risk assessment. When DXA, BMD measurements are insufficient to diagnose osteoporosis, indicators such as bone turnover biomarkers can be helpful in providing an early assessment of the osteoporosis [

5]. According to reports, bone turnover biomarkers (BTMs) can identify high-risk individuals who may develop osteoporosis and track bone recovery following treatment [

6]. Complications of osteoporosis include compromised bone strength, fractures, accelerated bone loss and compromised microarchitecture [

10,

11]. While osteoporosis is not a firm contraindication for dental implants and bone regeneration oral surgery, caution and proper planning are advised, in part due to difficulty in osseointegration and the possibility of increased bone loss and implant failure [

12,

13]. However, there is high-quality evidence suggesting that nutritional factors such as Vit.D and calcium have a significant positive effect in preventing osteoporosis complications [

11].

Strongly linked with the outcome of bone regeneration, Vitamin D (Vit.D) is a steroid hormone produced by the skin when enough sun exposure occurs and which is then transformed into its active form in the liver and kidneys. Additional sources of Vit.D include foods like oily fish, liver (beef), eggs, milk, cheese, soy, and mushrooms. It promotes intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphate, which is important for maintaining mineral homeostasis. Furthermore, it intervenes in the regulation of bone metabolism and bone mineralization by activating osteoclasts and osteoblasts [

14]. Decreased levels of Vit.D are associated with accelerated bone turnover, reduction in bone density, and increased risk of bone fractures [

15]. A biologically active form of Vit.D, calcitriol (1,25(OH)2D3), is responsible for calcium-phosphate homeostasis and is essential to the mineralization of cartilage and bone matrix. Furthermore, it regulates osteoblast genes expression. Additionally, calcitriol regulates the adaptive immune response, suppressing T-lymphocytes proliferation and immunoglobulin secretion, thus promoting an environment which favors inflammation resolution [

17]. This suggests that adequate levels of Vit.D could positively influence the integration of bone grafts, bone regeneration and mineralization. A recent umbrella review concluded that while further clinical studies are necessary to establish a firm conclusion, vitamin D may have a positive effect and play an important role in the osseointegration and survival of dental implants, while also reducing bone loss [

17].

Although Vit.D has known systemic health benefits and proven positive effects on osteogenesis, its lipidic nature limits administration to oral or intramuscular injection routes. Furthermore, the half-life of Vit. D bioactive metabolites in systemic circulation are relatively short (a few hours), and local bioavailability may be a concern due to metabolic conversion of active forms [

18,

19]. Therefore, bone regeneration using Vit.D as an active substance might benefit from a controlled local release system, which could ensure constant bioactive concentrations of Vit.D locally available, in order to ensure optimal results. Recent studies have explored the possibilities of local delivery systems, using in vitro and animal models. Vitamin D-conjugated gold nano-particles and scaffolds based on polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) with added Vit.D were demonstrated to increase osteogenic differentiation in vitro [

20,

21]. Palmitic acid (PA)-based sterosomes loaded with Vit.D-3 have been used as an osteoinductive drug delivery system in mouse calvarial defects, significantly improving osteogenesis [

18]. Calcitriol-loaded polylactic acid (PLA) microspheres were successfully used to attenuate periodontal inflammation and decrease bone loss in diabetic rats with ligature-induced periodontitis [

22]. A Vit.D and curcumin-loaded polycaprolactone (PCL) nanofibrous membrane was used in rats with calvarial bone defects and has been demonstrated to increase osteosynthesis [

23]. Membranes loaded with Vit.D have been used to treat maxillary bone defects in rats successfully [

24].

Current bone regeneration techniques in dentistry use advanced technologies, such as nanobioengineering. Nanobioengineering is a developing field that can combine biological and engineering principles to regenerate damaged or lost bone tissue. This innovative field uses biomaterials with nanoscale features, stem cells, and growth factors to obtain three-dimensional scaffolds, to stimulate and improve bone tissue regeneration [

25]. For example, biomaterials used in bone tissue engineering can be of natural or synthetic origin, and can be applied in direct contact with living tissues, without causing any adverse immune reaction [

26]. Nanostructured materials usually contain an active substance, which can be incorporated in various ways: encapsulated in their substructure in the form of hybrid core-shell nanoparticles, incorporated in nano-scale porosities, or chemically linked to the material’s structure. Generally, the release of active substances occurs gradually and simultaneously with the degradation of the nanostructure in which they were loaded, a degradation rate that depends on several factors including: the composition of the material, the morphological features of the nanostructure and the tissue in which they are applied [

26]. Nanostructured membranes (NMs) are a type of nanomaterial widely used in regenerative therapy. They can be obtained from natural biomaterials (chitosan (CS)), and synthetic materials – e.g. polymers (polylactic acid (PLA), poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL) [

27]. Chitosan is a natural amino polysaccharide derived from chitin, that demonstrates exceptional biocompatibility, swelling ability and biodegradability. Chitosan-based membranes are similar to the backbone of glycosaminoglycan in their chemical structure, making them porous microstructures that allow stem cells to migrate, attach, and multiply. Therefore, bioactive substances including ions, medications, proteins, or growth factors (GFs) are added to chitosan membranes to improve their ability to promote bone regeneration [

28,

29].

Therefore, we questioned whether Vit.D supplementation, delivered locally, could improve and aid bone regeneration in an osteoporotic bone defect model, thereby improving predictability for osseointegration and bone regrowth, thus aiding regenerative dentistry techniques. In light of the aforementioned, the aim of the present study was to assess the bone regeneration potential of a new chitosan nanostructured membrane loaded with vitamin D, in an osteoporotic animal model. The animal model chosen for this study was the Wistar rats because it is the ideal option for preclinical experiments. Accessibility, morpho-physiological correspondence with the human race, and the possibility of obtaining relevant data in a short time make this model the most used species for experiments. This article was prepared in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines provided in the Supplementary Material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

The study received the Ethics Commission approval of Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj-Napoca (no. AVZ36/31.03.2023), as well as the Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Agency approval (no. 361/28.04.2023). The experiment was performed at the Centre for Experimental Medicine and Practical Skills (UMF Biobase) Cluj-Napoca, in accordance with institutional, national, and European guidelines (Directive 2010/63/EU).

The animal model selected for this study was the Wistar rat, due to its widespread use in in vivo studies and suitability for preclinical research. Its accessibility, the morphological and physiological similarities to the human species, and the ability to obtain reliable and relevant data within a relatively short timeframe make it one of the most frequently employed models in experimental biomedical studies. We used osteoporotic rats to simulate reduced osseous regenerative capacity. The experimental treatment is not estimated to be harmful to animals. The estimated required sample size was approximately 8–10 animals per group. To account for potential dropout or experimental variability, slightly larger group sizes were used, resulting in a total of 30 animals. Each animal had 2 sites of bone regeneration created (2 bone defects), hence doubling the number of assessed sites. This approach ensured adequate statistical power, while remaining consistent with ethical guidelines for animal research and minimizing animal use following the principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement).

Subjects were included in the study base on the following criteria: 8–12 weeks old and weighing 200 ± 50 mg, born and raised at the same animal facility, without any genetic modification. The animals came from the Centre for Experimental Medicine and Practical Skills (UMF Biobase) Cluj-Napoca (authorization nr. 937/23.03.2022). The animals were kept at a temperature of 210 C and lived through a 12-hours/12-hours dark/light cycle. Standard pellet-food and water ad libitum was provided. The animals were monitored 24 hours a day.

2.2. The Method of Obtaining the Chitosan-Based NM

Nanostructured membranes of chitosan were fabricated by dissolving medium molecular weight chitosan (Sigma Aldrich) in 10% CH3-COOH at a final concentration of 20 mg/ml. A drop of chitosan solution was cast on a clean nanopatterned surface of a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) printed mold, and let to dry at 400 C overnight. After 24 h, the newly formed nanostructured thin membranes were carefully detached from the PDMS mold and UV-sterilized before the in vivo testing. The membranes were sputter-coated with 7 nm Pt/Pd in Agar Automated SputterCoater and examined by Scanning Electron Microscopy using a Hitachi SU9320 CFEG STEM.

2.3. In Vivo Experimental Design and Surgical Procedures

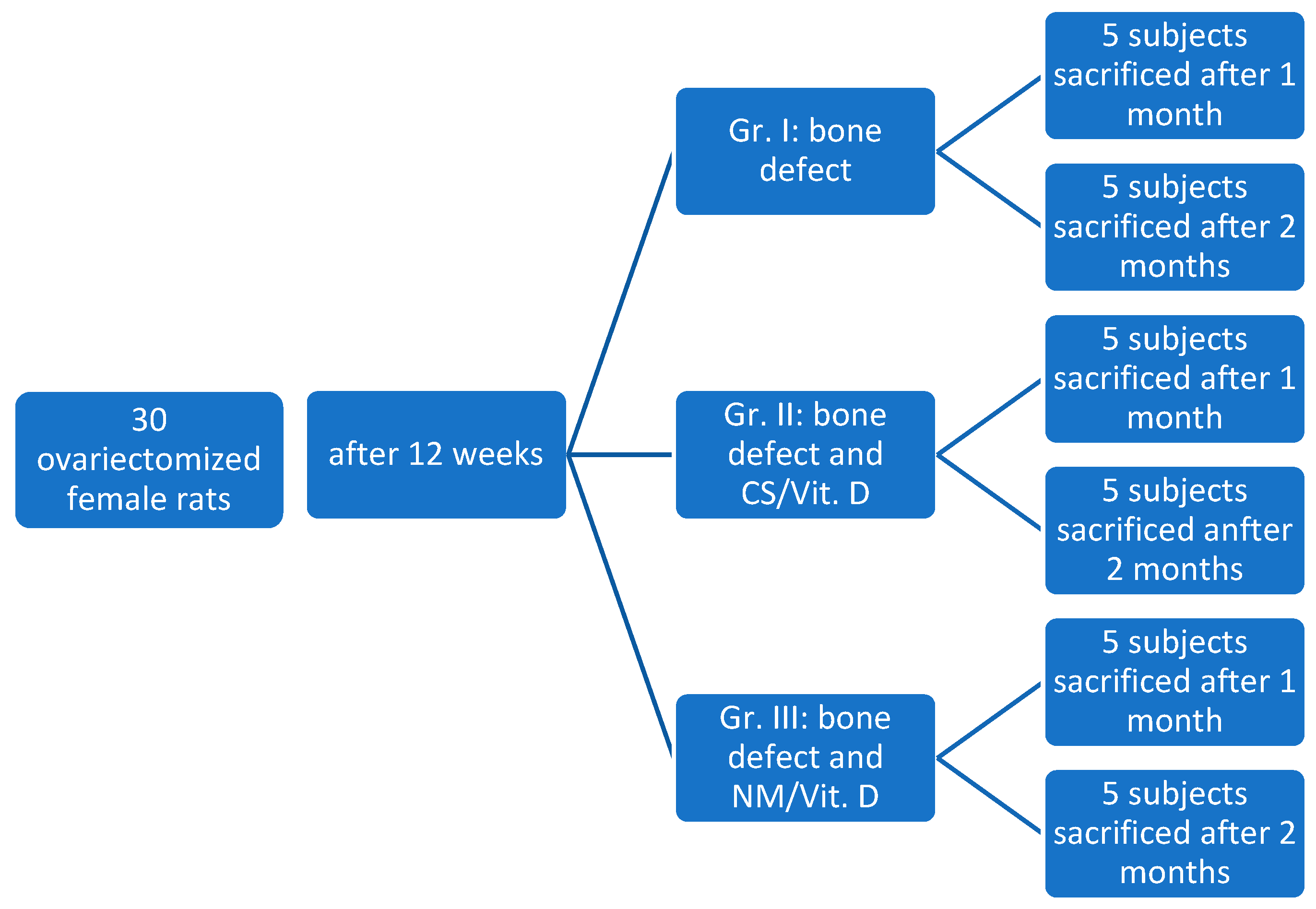

The rats were housed for acclimatization for about 1 week and then randomly assigned into the three study groups: Group I (control - 10 subjects), Group II (CS (collagen sponge)/Vit.D - 10 subjects), Group III (NM (nanostructured membrane) /Vit.D - 10 subjects).

The protocol of this study comprised three stages: Stage 1 - ovariectomy of all rats for the purpose of inducing osteoporosis; Stage 2 - creating bone defects in the jawbone and applying treatment according to study group; Stage 3 - euthanasia of rats, at one month or two months, and collection of tissue samples for histological examination (

Figure 1).

2.3.1. Ovariectomy (OVX) Procedure

After all the subjects were declared clinically healthy by a veterinary doctor, ovariectomy was performed for all subjects, in order to induce osteoporosis. General anesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (0.1 mg/kg, Ketamine 10% solution; Kepro B.V., Holland) in combination with xylazine (0.5 mg/kg, 2% solution; Xylazin Bio, Bioveta, Ivanovice na Hané, Czech Republic). The depth of anesthesia was carefully monitored throughout the procedure using multiple parameters, including the absence of the palpebral and pedal withdrawal reflexes, reduction in muscle tone, and evaluation of respiratory rate and depth. These indicators were assessed at standardized intervals to ensure adequate anesthesia and to prevent intraoperative pain perception or movement.

After anesthesia was induced, the animals were prepared for surgery by shaving the abdominal area and disinfecting the skin with betadine solution. To avoid making two lateral incisions, a midline surgical approach was chosen. The animals were placed in dorsal recumbency and properly restrained.An incision of approximately 2 cm was made along the midline (linea alba), allowing access to the abdominal cavity. The uterine horns were identified and exteriorized, followed by exposure of the ovaries. To reduce intraoperative bleeding and shorten the duration of anesthesia exposure, ovariectomy was performed using an electrocautery device. At the end of the procedure, all anatomical layers were sutured in separate planes.

Postoperatively, the subjects received analgesic treatment. Postoperative analgesia was achieved by administering meloxicam at a maximum dose of 0.37 mg/kg once daily, for three consecutive days. Antibiotic prophylaxis was implemented using enrofloxacin 5% at a maximum dose of 1 mg/animal/day, administered for five days postoperatively, in order to prevent systemic infections and ensure optimal recovery. The animals were monitored 24 hours a day. On the first day after the intervention, hourly controls were conducted.

2.3.2. Blood Samples

Blood samples from the retro-orbital artery were collected, to determine plasma levels of bone turnover biomarkers. The bone formation marker- osteocalcin (OC) was determined using Rat Osteocalcin ELISA Kit, FineTest (Wuhan Fine Biotech Co., Ltd.) and bone resorption markers- β-crosslaps (β-CTX) were determined using the Rat β-CTX ELISA Kit FineTest (Wuhan Fine Biotech Co., Ltd.). The blood samples were collected in two points: before ovariectomy (T0) and 12 weeks after ovariectomy (T1). The samples were incubated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance measurements were subsequently performed using an 800 TS ELISA microplate reader (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), and plate washing was conducted with a Biotek Microplate 50 TS washer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.3.3. Bone Defect Preparation and Treatment Application

To simulate a post-extraction alveolus, we created bone defects located on the mesial side of the maxillary first molar, bilaterally. The bone defects were performed 12 weeks after ovariectomy, once a positive osteoporosis diagnosis was established by the aforementioned bone turnover biomarkers.

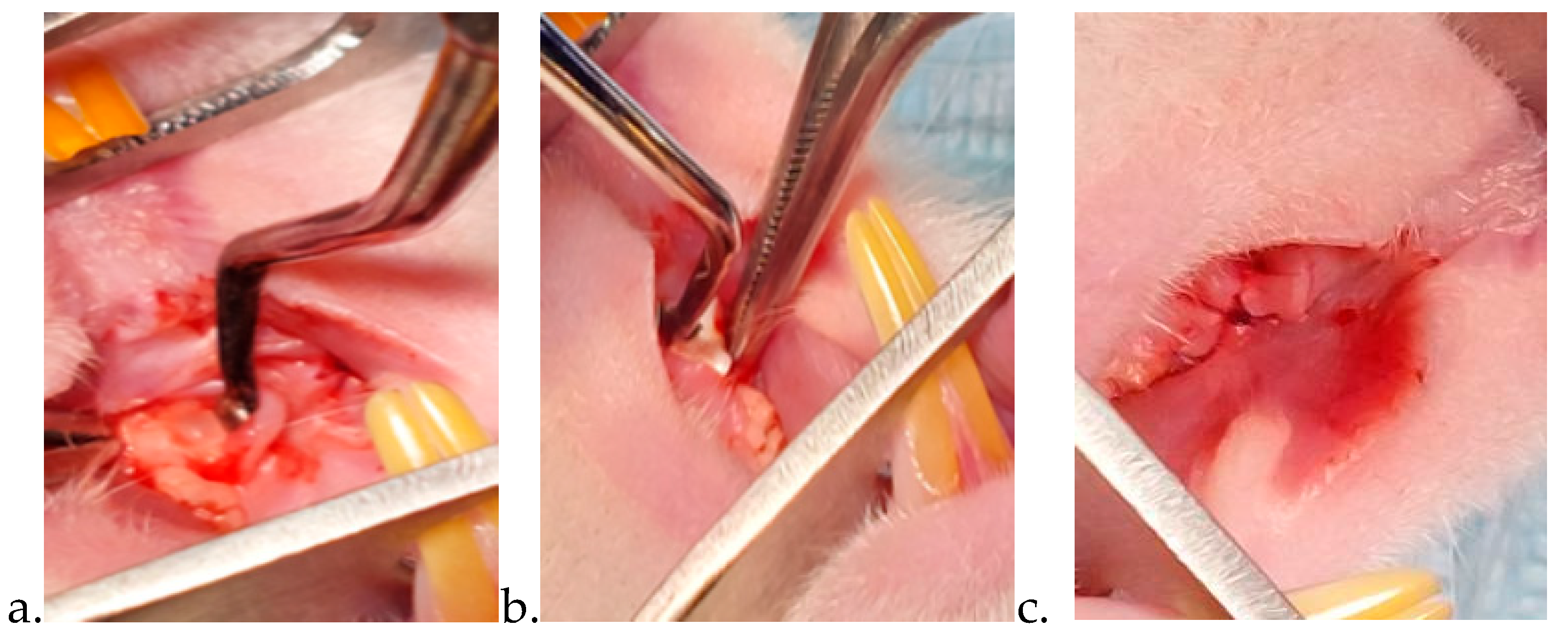

Following general anesthesia (using the same protocol previously described for the ovariectomy), the rats were weighed and placed on the operation table in a horizontal supine position. This position facilitated access to the area of interest. After crestal incision and full-thickness flap elevation, the bone defect (1 × 1 × 1 mm3 L W D) was made using sterile dedicated dental round drills, under continuous cooling with sterile saline. Surgery was performed using magnification loupes (2.5× magnification) with an incorporated light source, as well as under surgical lights. Treatment was applied in accordance to the study groups. For group I (control group) the bone defect was covered with the previously created flap, without the application of any drug substance. For group II a collagen sponge soaked with Vit. D was applied in the bone defect and then covered with the flap and sutured. For group III the novel nanostructured chitosan membrane loaded with Vit. D was applied in the bone defect. A commercial membrane (Bio-gide 25x25 Mm Geistlich) was applied on top of the defect, this having the role of a barrier. Afterwards, we covered the membrane with a vestibular flap. The flaps were closed using resorbable sutures (LUXCRYL 910 6/0, LUXSUTURES, Luxemburg) (

Figure 2).

After surgery, analgesia was introduced in the subjects’ drinking water supply. Throughout the duration of the study, the animals were constantly observed, to ensure optimal analgesic management and infection prevention.

Euthanasia of the subjects was conducted by anesthetic overdose (ketamine: 150-200 mg/kg, xylazine 10-15 mg/kg). Half of the subjects of each group were sacrificed at one month after bone defect treatment, and the second half at two months after bone defect treatment.

2.4. Histological Analysis

Rats were euthanized at 1- and 2-months post-bone defect surgery. Symmetrical 2x2x2 cm sections of the left and right maxilla were harvested. These were initially preserved in 10% formalin for 48 hours, followed by immersion in Osteodec—a bisodium EDTA acid-buffered decalcifying agent—for 72 hours to facilitate calcium chelation. Once macroscopically identifying the stigma, one targeted section was obtained from each sample, and afterwards processed using standard histological techniques. Each section was cut into 4-micrometer-thick slices, mounted on slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The slides were examined by a general pathologist using a Leica DM750 digital microscopy system (Leica Biosystems, IL, United States) with an integrated ICC50 digital camera and LAS EZ software. The pathologist was unaware of the subjects’ group assignments at the time of microscopic evaluation, since the slides were labeled using non-sequential numbers.

The microscopic analysis aimed to characterize the bone defect in each study group. For objective assessment, the original size of the bone defect was measured microscopically for each specimen. Using the optical microscope, the maximum length and width (in mm) of the defect were recorded, and the defect surface area was calculated (length × width). These morphometric measurements provided quantitative baseline data on the initial defect, facilitating a more rigorous comparison between groups. Afterwards, several parameters were meticulously evaluated using an adaptation of two previously published histological scoring systems [

30,

31]. The evaluation criteria and corresponding scoring intervals are presented in

Table 1. To enhance data consistency, histological scores from the left and right samples of the same subject were combined.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results were stored in a Microsoft Excel database. All data were analyzed using Social Science Statistics software (

https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/). Data set normality was tested with Shapiro-Wilk test with the significance level α=0.05. The mass is normally distributed as follows: initial mass p=0.78> α, the mass before bone defect produced (12 weeks after ovariectomy) p=0.964> α, at the time of sacrifice: group 3 p=0.329> α, group 2 p=0.656> α, group 1 p=0.285> α. T-test for two independent means was used to compare the mean mass between groups, and t- test for two dependent means was used to compare the mean mass in the same group in evolution. Also, Mann-Whitney U Test was used for non-normal data sets such as histological parameters. (www.statskingdom.com/shapiro-wilk-test-calculator.html. The morphometric data regarding the size of the bone defect were analyzed using one-way ANOVA to assess statistical differences in defect size across groups. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Animals

Two animals from the control group died due to anesthesia complications. Statistically significant weight gain was registered in all animals after ovariectomy (t=16.22887, p<.00001).

3.2. Characterization of Nanostructured Membranes

Nanostructured membranes were fabricated using chitosan biopolymer as a template material. Among the class of natural polymers, chitosan, a glucosamine polymer obtained by the deacetylation of chitin, was selected based on its demonstrated osteogenic properties but also due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability and renewed antibacterial activity [

32,

33,

34]. The nanostructured membranes were prepared by the method described above. Vitamin D (100 μg/mL in ethanol, Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted at the desired concentration (300nM solution- Vitamin D in ethanol) and dripped on the UV-sterilized polymeric membranes which act as a scaffold for its encapsulation and delivery at the place of insertion.

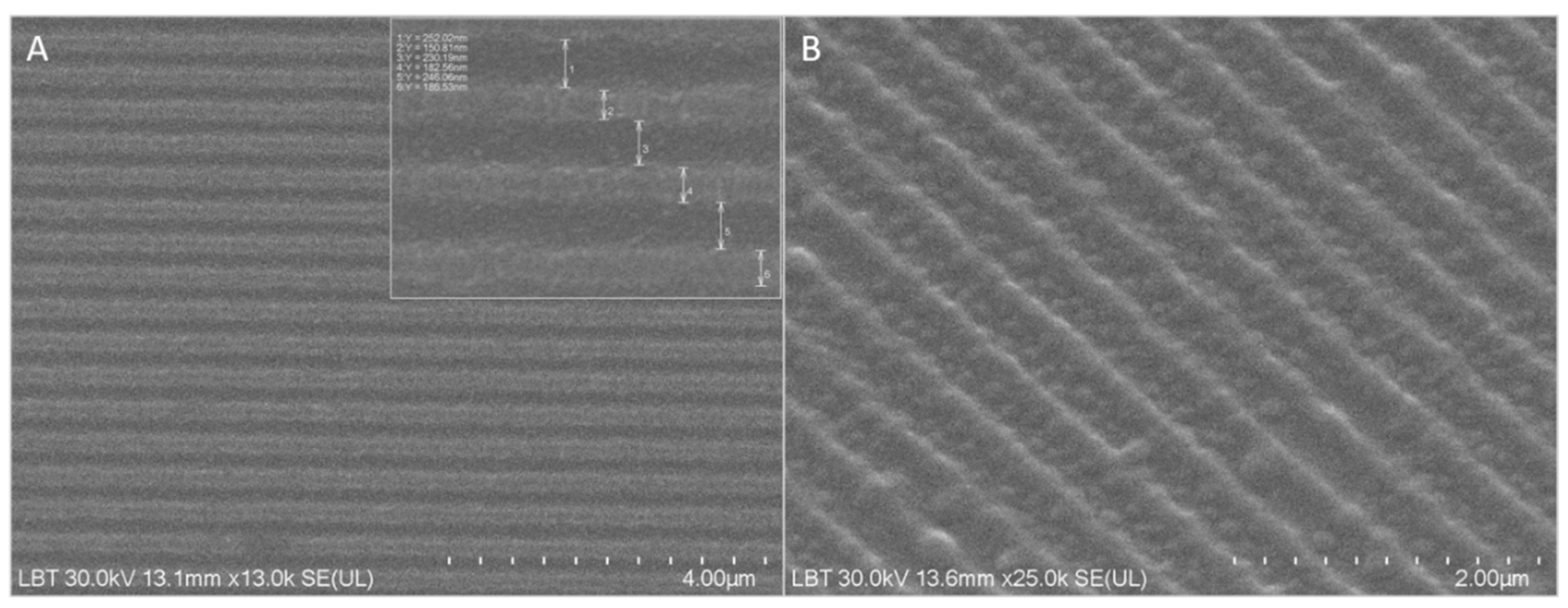

The fabricated nanostructured membranes were morphologically characterized by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). SEM images are presented in

Figure 3. A, B, and indicate the formation of equally spaced parallel rectangular grooves having a periodicity of 415±11 nm (242±8 nm width and 173±14 nm wall) and 200 nm depth.

3.3. Blood Samples Results

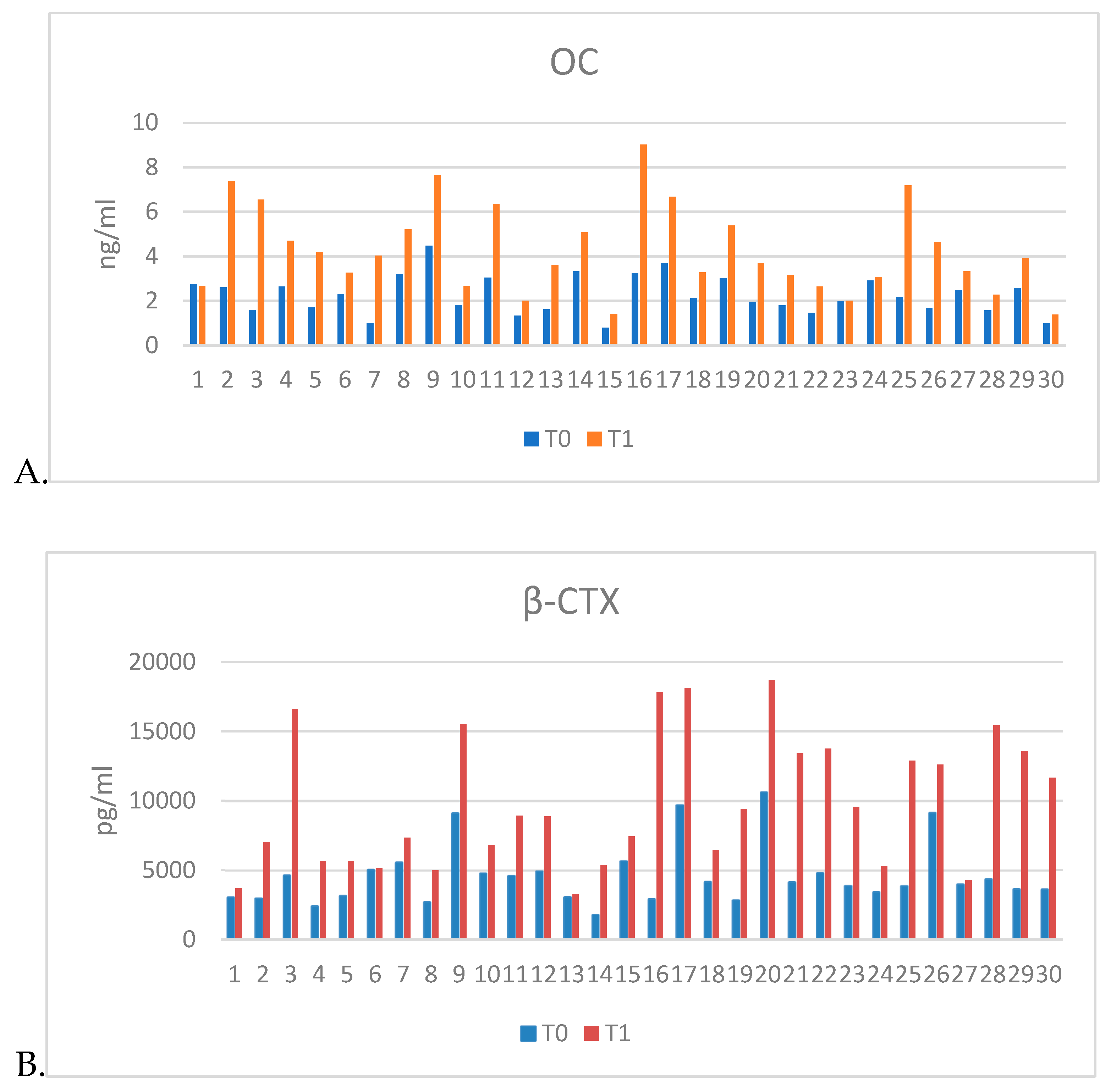

Results of serum biomarkers determination show an increase in levels of OC and β-CTX in plasma harvested 12 weeks after ovariectomy (T1) compared to plasma levels prior to ovariectomy (T0). These results, along with the histological results, confirmed the onset of osteoporosis (

Table 2,

Figure 4).

3.4. Histopathological assessment of bone regeneration:

3.4.1. Grossing

Bilateral (left and right) maxillary tissue samples were collected from 28 rats, divided across three groups: group I - 8 rats, Group II - 10 rats and group III - 10 rats. Due to improper fixation and resulting necrosis, 4 samples from group II and 6 samples from group III were excluded from scoring and statistical analysis. The statistical analysis was performed on 8 subjects with 16 induced bone defects from group I, 8 subjects with 16 bone defect sites from group II and 6 subjects with 12 bone defect sites from group III.

To enhance microscopic detail, the right maxilla was sectioned along the bone defect's longitudinal axis, while the left maxilla was sectioned perpendicularly. The bone defect was observed in all samples. The hemostatic foam in group II and nanostructure and protective membranes in group III were not detected in any sample.

3.4.2. Microscopic Findings

Morphometric evaluation of the bone defect dimensions revealed a progressive reduction in defect area from group I (control) to group III (NM/Vit.D). The mean surface area of the defect was 0.34 ± 0.19 mm² in group I, 0.28 ± 0.13 mm² in group II, and 0.21 ± 0.10 mm² in group III. Although a trend toward smaller defect sizes was observed in the therapeutic groups, particularly in group III, the differences did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.115).

Pathological scoring followed the aforementioned parameters described in

Table 1 (in the Materials and Methods chapter). The final scores obtained following the histopathological assessment are presented in

Table 3.

The Histopathology_Summary_Table is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Thin, disconnected bone trabeculae, indicative of severe osteoporosis, were observed in half of the rats in group I (control). Meanwhile, groups II (CS/Vit.D) and III (NM/Vit.D) displayed only mild osteoporotic changes. Overall, signs of mild osteoporosis were present in all groups, with severity decreasing from group I (control) to group III (NM/Vit.D).

The following tissue configurations were observed within the area of the bone defect (

Figure 5):

1. a peripheral rim of fibrous connective tissue with a central void (15.15% of samples);

2. fibrous connective tissue in both peripheral and central areas (21.21% of samples);

3. a combination of fibrous connective and osseous tissue (48.48% of samples);

4. osseous tissue alone (15.15% of samples).

When examined by group, osseous tissue alone or with connective tissue was observed in 18.18% of group I (control) samples, 75% of group II (CS/Vit.D) samples, and 83.33% of group III (NM/Vit.D) samples. Bone formation on the graft surface was significantly superior in groups II (CS/Vit.D) and III (NM/Vit.D) compared to group I (control) (p = 0.023). Mature bone was more frequently present in both peripheral and central areas in group III (NM/Vit.D), compared to groups I (control) and II (CS/Vit.D) (p = 0.016). No significant difference across groups was found in bone formation within the center of the defect or in immature bone formation. Both therapeutic groups (II and III) showed greater quantity and thickness of bone trabeculae in the graft's peripheral and central areas.

A bone bridge could not be identified in 83.33% samples from group I (control), while the rest of 16.66% exhibited a thin bone bridge. In comparison with group I (control), all subjects in the therapeutic groups (II and III) showed thin or thick bone bridges (p = 0.001). No significant difference was found in bone bridge thickness between groups II (CS/Vit.D) and III (NM/Vit.D); however, histological scores were higher for group III (NM/Vit.D), with thick bone bridges in 66.66% of cases compared to thick bone bridges in 33.33% of cases in group II (CS/Vit.D) (

Figure 6). More abundant bone trabeculae were encountered in the targeted area in group II (CS/Vit.D) (p=0.01) and group III (NM/Vit.D) (p>0.05), compared to bone defects in group I (control). There was no statistically significant difference between groups concerning Havers canals.

Regarding bone-forming cells, osteoblasts were more numerous in the graft’s peripheral and central areas for group II (CS/Vit.D), in comparison to groups I (control) and III (NM/Vit.D). This was constant in both cases, rats sacrificed at one month (p = 0.045) and two months post-intervention (p = 0.019). Osteocyte scores were also more elevated in group II (CS/Vit.D) at both one (p = 0.025) and two months post-intervention (p = 0.012). Osteoclasts were present only in the graft periphery across all groups, with no statistically significant differences among groups.

In group I (control), vascularization was limited to the surface of the bone defect, in half of the samples. In contrast, vascularization penetrated the graft’s center in all samples for groups II (CS/Vit.D) and III (NM/Vit.D) (

Figure 7). Among rats sacrificed one-month post-intervention, vascularization occurred more rapidly in group III (NM/Vit.D) than in group II (CS/Vit.D) (p = 0.045).

Lower inflammation levels were observed in the therapeutic groups (II and III) compared to group I (control), in rats sacrificed after one month (p = 0.033) and two months post-intervention (p = 0.018). Two unilateral abscesses were noted: one in a single sample from group II (CS/Vit.D) and the other in a single sample from group III (NM/Vit.D) (

Figure 8). Complete degradation of the synthetic membrane was observed, with no microscopically detectable graft material in any subject. The extent of mature bone replacement in the grafted regions was highest in group III (NM/Vit.D) (p = 0.042).

4. Discussion

Vitamin D is an essential vitamin for bone mineral density, providing excellent opportunities to prevent and treat osteoporosis, as well as to maintain overall bone health [

35,

36]. Numerous studies have confirmed the role of Vitamin D in the process of osseointegration, suggesting that a deficiency in Vitamin D negatively affects bone regeneration and may impair implant osseointegration [

37].In most scientific literature, vitamin D is predominantly administered orally to treat systemic deficiency. The study conducted by Kwiatek J. et al. (2021) [

38] highlights that oral administration of Vitamin D prior to dental implant insertion may promote osseointegration by increasing bone density. However, the actual effectiveness of this method can vary significantly depending on the patient's metabolic and hormonal status.

As an alternative, the literature describes local applications of Vitamin D, either through implant surface modification to enhance bone–implant contact [

39], or via a single topical application. The latter approach is nonetheless considered to be insufficient in predictably stimulating bone regeneration [

40].

Nanostructured materials such as chitosan, PLGA, hydroxyapatite, or mesoporous silica allow the encapsulation of Vitamin D and other active substances, enabling their controlled and targeted release. Relevant studies confirm the scientific interest in such approaches. For example, Ghavimi M.A. et al. (2020) developed an asymmetric membrane with curcumin and aspirin for guided bone regeneration, indicating the potential of synergistic combinations [

41]. Ho M.H. et al. (2022) used a functionally graded membrane with doxycycline- and enamel matrix derivative (EMD)-based nanofibrous composites to coordinate anti-inflammatory and osteogenic responses [

42]. More recently, Zhou H. et al. (2024) proposed a Janus membrane with an asymmetric structure based on bacterial cellulose and Ti3C2Tx MXene, demonstrating its applicability in guided bone regeneration [

43]. However, the complexity of the materials used and the lack of long-term data are aspects that require a more rigorous and self-critical approach to validate these technologies.

In the present study, we explored the effect of Vitamin D loaded on a nanostructured chitosan membrane, compared to natural healing and to a single local application using a hemostatic sponge. The nanostructured topography and the functional groups of chitosan (–OH, −NH2) can influence not only the mechanical properties of the membrane, but also the biological behavior of the material, acting as a synergistic enhancer of Vitamin D efficiency [

44,

45].

We used an animal model with induced osteoporosis, known for its reduced bone regeneration capacity. While the effects of osteoporosis on the jawbones are still debated, growing evidence from both preclinical and clinical studies points to a link between overall bone density and that of the jaws. Moreover, retrospective research suggests that osteoporosis may adversely affect pre-prosthetic bone grafting procedures or sinus augmentation surgeries [

46]. Studies from the scientific literature confirm that a 12-week period post-ovariectomy is sufficient for the onset of bone changes characteristic of osteoporosis [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. This framework allowed us to test interventions in a more realistic but also more challenging biological context.

Histological analysis and bone turnover biomarker evaluation confirmed the presence of osteoporosis, and the timing for defect induction was justified by these data. However, it must be noted that the animal model has its own limitations in extrapolating results to the human clinical context.

The results suggest that both methods of local Vitamin D administration can stimulate bone regeneration; however, the Vitamin D-loaded nanostructured chitosan membrane (NM/Vit.D) performed better in terms of bone density and matrix maturation. Nevertheless, the group treated with the hemostatic sponge (CS/Vit.D) showed higher scores for osteoblasts and osteocytes, suggesting intense metabolic activity during the early phase. This discrepancy between cellular activity and the amount of bone formed suggests a complex dynamic that requires further investigation to be fully understood.

The presence of Haversian canals also varied over time among groups, indicating that bone remodeling is not linear but conditioned by multiple variables which are still unclear in the current literature.

Overall, although both methods that include the loading of the active ingredient on a solid scaffold appear more effective that the administration of the Vit.D without any support matrix, the chitosan-based NM loaded with Vit.D provides evidence of improved efficiency in comparison with the hemostatic sponge. We attribute this effect both to the morphological characteristics of the chitosan membrane, specifically the nanoscale surface topography but also to the biomaterial, known for its hygroscopic properties [

53]. Despite its strengths, our study also has a number of limitations: the lack of a functional placebo control (group only with the chitosan-based NM without vitamin D.), the relatively small number of subjects, and the fact that long-term effects of bone regeneration were not tracked.

Compared to well-established methods—autografts and allografts—which remain the gold standard in bone defect therapy, the use of functional biomaterials such as chitosan-based NM offers a viable alternative, with potential to reduce risks and complications (infections, morbidity, poor integration) [

37,

49]. However, clinical applicability remains a challenge, and further studies are needed for validation.

Our study results complement the research directions proposed by authors such as García-Gareta (2015) [

54] and Wang C.W. (2020) [

55], who emphasize the need to develop smart biomaterials with controlled delivery. The novelty lies in integrating Vit.D into a bioactive matrix that not only supports regeneration but also accelerates it even under adverse conditions such as osteoporosis.

The limitations of this study lie in the small number of animals used, but to improve this small number, bone defects were performed bilaterally leading to a doubling of the number of sites to be analyzed. A second limitation of this study was a further reduction in the number of defects, namely 4 samples from group II and 8 samples from group III, due to improper fixation and the occurrence of necrosis. The absence of local release data in the current study represents another limitation, which we aim to address in future in vitro and in vivo investigations. Regarding the validation of the osteoporotic model, this study primarily relied on findings from previously published literature, which constitutes a limitation of our research. This approach was chosen to reduce the number of animals used, in line with the 3Rs principle (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement). However, to support the induction of osteoporosis, we measured two bone turnover biomarkers. As a control group, we used samples collected prior to oophorectomy, which introduces an additional limitation to this study. Another limitation lies in the descriptive histopathological assessment. We fully recognize that our semi-quantitative scoring lacks the morphometric precision that digital image analysis could provide. However, the standard light microscope does not support morphometric calibration, such as integrated digital quantification tools that are necessary for accurate area or volume measurements. Retrofitting them for morphometry would require additional software and validation, which were beyond the scope and intended resources of this study. Future work incorporating digital morphometry or dedicated morphometric microscopy (e.g., using calibrated stage micrometers or specific software) would indeed provide higher precision and could be pursued as part of subsequent studies. Additionally, we plan to integrate Masson's Trichrome staining in future protocols, which offers superior contrast between mineralized bone, fibrous tissue, and unmineralized osteoid. This stain will facilitate more precise discrimination and quantification of regenerated bone matrix versus fibrotic or residual soft tissue components, further strengthening the morphometric assessment and histological evaluation of regenerative outcomes.

Future studies should consider the inclusion of additional control groups—such as sponge with vitamin D plus Bioguide—and extended observation periods to further clarify the role of each material component in bone healing.

5. Conclusions

The present study proves that, Vit. D loaded on chitosan NM has positive effects in the regenerative therapy of bone tissue, compared to hemostatic sponge and natural healing. Local, sustained and targeted release of vitamin D on a bioactive carrier such as chitosan NM can provide a relevant therapeutic strategy in bone regeneration, with potential for clinical translation. However, this hypothesis needs to be validated through rigorous clinical trials to confirm long-term efficacy and safety.

Supplementary Material: The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org: The ARRIVE guidelines: author checklist and Histopathology_Summary_Table.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.G.M., O.L. and M.H.; methodology: M.H., C.G.M., O.L., L.M.G., C.M.M. and S.B.; validation: O.L., M.H., F.O., S.B. and C.M.M.; formal analysis: N.P., S.A.L.I, E.V., E.O., A.C. and B.A.A.; investigation: C.G.M., L.P.M., M.M.O., R.M.P. and L.B.T. ; resources: C.G.M., O.L. and N.P..; data curation: C.G.M., S.B. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation: C.G.M., O.L., S.B., L.P.M. and R.M.P.; writing—review and editing: M.H., C.M.M., F.O, L.B.T. and L.M.G.; visualization: C.G.M., S.A.L.I., E.O., A.C., B.A.A and B.A.B.; supervision: O.L., M.H., S.B., F.O. and C.M.M.; project administration: C.G.M., O.L., M.H. and S.B.; funding acquisition: C.G.M., M.H., S.B., L.P.M., M.M.O., R.M.P. and L.M.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by project PNRR-III-C9-2023-I8, "Technologically Enabled Advancements in Dental Medicine (TEAM)", CF.80/31.07.2023, number 760235/28.12.2023.

Acknowledgments

Sanda Boca acknowledges financial support from MCID through the Nucleu Program within the National Plan for Research, Development and Innovation 2022–2027, project PN 23 24 01 02.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Park, G.; Jalkh, E.B.; Boczar, D.; Bergamo, E.T.; Kim, H.; Kurgansky, G.; Torroni, A.; Gil, L.F.; Bonfante, E.A.; Coelho, P.G.; Witek, L. Bone regeneration at extraction sockets filled with leukocyte-platelet-rich fibrin: An experimental pre-clinical study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2022, 27, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagni, G.; Pellegrini, G.; Giannobile, W.V.; Rasperini, G. Postextraction alveolar ridge preservation: biological basis and treatments. Int J Dent. 2012, 151030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schropp, L.; Wenzel, A.; Kostopoulos, L.; Karring, T. Bone healing and soft tissue contour changes following single-tooth extraction: a clinical and radiographic 12-month prospective study. Int J Periodontics Restor Dent. 2003, 23, 313–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.G. Advancements in alveolar bone grafting and ridge preservation: a narrative review on materials, techniques, and clinical outcomes. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024, 46, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.R.; Chen, C.H. Bone biomarker for the clinical assessment of osteoporosis: recent developments and future perspectives. Biomark Res. 2017, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Ye, J.; Liang, R.; Yao, X.; Wu, X.; Koh, Y.; Wei, W.; Zhang, X.; Ouyang, H. Advanced Strategies of Biomimetic Tissue-Engineered Grafts for Bone Regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Apablaza, J.; Prieto, R.; Rojas, M.; Fuentes, R. Potential of Oral Cavity Stem Cells for Bone Regeneration: A Scoping Review. Cells. 2023, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH, C. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. NIH consensus statement. 2000, 17, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroshima, S. , Kaku, M., Ishimoto, T., Sasaki, M., Nakano, T., Sawase, T. A paradigm shift for bone quality in dentistry: A literature review. J Prosthodont Res 2017, 61, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aspray, T.J.; Hill, T.R. Osteoporosis and the Ageing Skeleton. Subcell Biochem. 2019, 91, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avenell, A.; Mak, J.C.; O'Connell, D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014, CD000227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibli, J.A.; Naddeo, V.; Cotrim, K.C.; Kalil, E.C.; de Avila, E.D.; Faot, F.; Faverani, L.P.; Souza, J.G.S.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fernandes, G.V.O. Osteoporosis' effects on dental implants osseointegration and survival rate: a systematic review of clinical studies. Quintessence Int. 2025, 56, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, C.A.A.; de Oliveira, A.S.; Faé, D.S.; Oliveira, H.F.F.E.; Del Rei Daltro Rosa, C.D., Bento, V.A.A.; Verri, F.R.; Pellizzer, E.P. Do dental implants placed in patients with osteoporosis have higher risks of failure and marginal bone loss compared to those in healthy patients? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2023, 27, 2483–2493. [CrossRef]

- Targonska., S.; Dominiak, S.; Wiglusz, R.J.; Dominiak, M. Investigation of Different Types of Micro- and Nanostructured Materials for Bone Grafting Application. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2022, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357, 266–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, E.M. The role of vitamin D in periodontal health and disease. J Periodontal Res. 2023, 58, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallon, E.; Macedo, J.P.; Faria, A.; Tallon, J.M.; Pinto, M.; Pereira, J. Can Vitamin D Levels Influence Bone Metabolism and Osseointegration of Dental Implants? An Umbrella Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024, 12, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Wen, J.; Ye, W.H.; Li, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, S.; Ma, J.C.; Wu, Y.; Chen, R.; Cui, Z.K. A facile and smart strategy to enhance bone regeneration with efficient vitamin D3 delivery through sterosome technology. J Control Release. 2024, 370, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, I. Vitamin D Metabolism and Guidelines for Vitamin D Supplementation. Clin Biochem Rev. 2020, 41, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, H.; Lee, D.; Heo, M.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.J.; Heo, D.N.; Seong, J.; Lim, H.N.; Lee, Y.H.; Moon, H.J.; Hwang, Y.S.; Kwon, I.K. Vitamin D-conjugated gold nanoparticles as functional carriers to enhancing osteogenic differentiation. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2019, 20, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cui, J.; Feng, W.; Lv, S.; Du, J.; Sun, J.; Han, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, X.; Yimin Oda, K.; Amizuka, N.; Li, M. Local administration of calcitriol positively influences bone remodeling and maturation during restoration of mandibular bone defects in rats. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2015, 49, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, B.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, X.M.; Li, W. Attenuation of inflammatory response by 25- hydroxyvitamin D3-loaded polylactic acid microspheres in treatment of periodontitis in diabetic rats. Chin J Dent Res. 2014, 17, 91–8. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bishari, A.M.; Al-Shaaobi, B.A.; Al-Bishari, A.A.; Al-Baadani, M.A.; Yu, L.; Shen, J.; Cai, L.; Shen, Y.; Deng, Z.; Gao, P. Vitamin D and curcumin-loaded PCL nanofibrous for engineering osteogenesis and immunomodulatory scaffold. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 975431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, D.S.; Jung, J.W.; Kim, J.H; Baek, S.W.; You, S.; Hwang, D.Y.; Han, D.K. Multifunctional vitamin D-incorporated PLGA scaffold with BMP/VEGF-overexpressed tonsil-derived MSC via CRISPR/Cas9 for bone tissue regeneration. Mater Today Bio. 2024, 28, 101254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Liu, W.; Deng, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, L. Angiogenesis and bone regeneration of porous nano-hydroxyapatite/coralline blocks coated with rhVEGF165 in critical-size alveolar bone defects in vivo. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015, 10, 2555–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werny, J.G.; Sagheb, K.; Diaz L, Kämmerer, P.W.; Al-Nawas, B.; Schiegnitz, E. Does vitamin D have an effect on osseointegration of dental implants? A systematic review. Int J Implant Dent. 2022, 8, 1. [CrossRef]

- Muresan, G.C.; Boca, S.; Lucaciu, O.; Hedesiu, M. The Applicability of Nanostructured Materials in Regenerating Soft and Bone Tissue in the Oral Cavity-A Review. Biomimetics (Basel). 2024, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, D.; Sekaran, S. In Vitro Biocompatibility Assessment of a Novel Membrane Containing Magnesium-Chitosan/Carboxymethyl Cellulose and Alginate Intended for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Cureus. 2024, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Ye, Y.; Wu, J.; Ma, Y.; Fang, Y.; Jiang, F.; Yu, J. Phosphoserine-loaded chitosan membranes promote bone regeneration by activating endogenous stem cells. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1096532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solchaga, L. A.; Yoo, J. U.; Lundberg, M.; Dennis, J. E.; Huibregtse, B. A.; Goldberg, V. M.; Caplan, A. I. Hyaluronan-based polymers in the treatment of osteochondral defects. J Orthop Res. 2000, 18, 773–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucaciu, O.; Gheban, D.; Soriţau, O.; Băciuţ, M.; Câmpian, R. S.; Băciuţ, G. (2015). Comparative assessment of bone regeneration by histometry and a histological scoring system/Evaluarea comparativă a regenerării osoase utilizând histometria și un scor de vindecare histologică. Revista Romana de Medicina de Laborator 1515, 23, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M. S.; Montero, M.; Staffolo, M. D.; Martino, M.; Bevilacqua, A.; Albertengo, L. Chitosan influence on glucose and calcium availability from yogurt: In vitro comparative study with plants fibre. Carbohydrate Polymers 2008, 74, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhuang, S. Antibacterial activity of chitosan and its derivatives and their interaction mechanism with bacteria: Current state and perspectives. European Polymer Journal, 2020, 138, 109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Selvaraj, V.; Saravanan, S.; Abullais, S.S.; Wankhade, V. Exploring the osteogenic potential of chitosan-quercetin bio-conjugate: In vitro and in vivo investigations in osteoporosis models. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024, 274, 133492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temova Rakuša, Ž.; Pišlar, M.; Kristl, A.; Roškar, R. Comprehensive Stability Study of Vitamin D3 in Aqueous Solutions and Liquid Commercial Products. Pharmaceutics. 2021, 13, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.H.; Yen, T.H.; Hong, A.; Chou, T.A. Association of vitamin D3 with alveolar bone regeneration in dogs. J Cell Mol Med. 2015, 19, 1208–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B.C.; Sacramento, C.M.; Sallum, E.A.; Monteiro, M.F.; Casarin, R.C.V.; Casati, M.Z.; Silvério, K.G. 1,25(OH)2D3 increase osteogenic potential of human periodontal ligament cells with low osteoblast potential. J Appl Oral Sci. 2024, 32, e20240160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatek, J.; Jaroń, A.; Trybek, G. Impact of the 25-Hydroxycholecalciferol Concentration and Vitamin D Deficiency Treatment on Changes in the Bone Level at the Implant Site during the Process of Osseointegration: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomó-Coll, O.; Maté-Sánchez de Val, J.E.; Ramírez-Fernandez, M.P.; Hernández-Alfaro, F.; Gargallo-Albiol, J.; Calvo-Guirado, J.L. Topical applications of vitamin D on implant surface for bone-to-implant contact enhance: A pilot study in dogs part II. Clin. Oral. Implants Res 2016, 27, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fügl, A.; Gruber, R.; Agis, H.; Lzicar, H.; Keibl, C.; Schwarze, U.Y.; Dvorak, G. Alveolar bone regeneration in response to local application of calcitriol in vitamin D deficient rats. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghavimi, M.A.; Bani Shahabadi, A.; Jarolmasjed, S.; Memar, M.Y.; Maleki Dizaj, S.; Sharifi, S. Nanofibrous asymmetric collagen/curcumin membrane containing aspirin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles for guided bone regeneration. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 18200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, M.H.; Huang, K.Y.; Tu, C.C.; Tai, W.; Chang, C.H.; Chang, Y.C.; Chang, P.C. Functionally graded membrane deposited with PDLLA nanofibers encapsulating doxycycline and enamel matrix derivatives-loaded chitosan nanospheres for alveolar ridge regeneration. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022, 203, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zha, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Ren, R.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhao, L. A Janus, robust, biodegradable bacterial cellulose/Ti3C2Tx MXene bilayer membranes for guided bone regeneration. Biomater Adv. 2024, 161, 213892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handrea-Dragan, I.M.; Botiz, I.; Tatar, A.S.; Boca, S. Patterning at the micro/nano-scale: Polymeric scaffolds for medical diagnostic and cell-surface interaction applications. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2022, 218, 112730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Reddy, K.P.; Datta, P.; Barui, A. Vitamin D3-incorporated chitosan/collagen/fibrinogen scaffolds promote angiogenesis and endothelial transition via HIF-1/IGF-1/VEGF pathways in dental pulp stem cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023, 253, 127325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Cui, X.; Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Gao, F.; Ma, M., Wang, Z. Antiosteoporosis effect of geraniin on ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis in experimental rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2021, 35, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X.; Ji, C.; Qu, S.; Wang, S.; Luo, Y. Cyclin G2 suppresses estrogen-mediated osteogenesis through inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. PLoS One. 2014, 9, 89884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Xiaoying, Z.; Xingguo, L. Ovariectomy-associated changes in bone mineral density and bone marrow haematopoiesis in rats. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009, 90, 512–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostu, D.; Lucaciu, O.; Mester, A.; Oltean-Dan, D.; Gheban, D.; Rares, Ciprian, Benea, H. Tibolone, alendronate, and simvastatin enhance implant osseointegration in a preclinical in vivo model. Clin Oral Implants Res 2020, 31, 655–668. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.H.; Zhang, X.B.; Lu, Y.B.; Hu, Y.C.; Chen, X.Y.; Yu, D.C.; Shi, J.T.; Yuan, W.H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.Y. Calcitonin gene-related peptide and brain-derived serotonin are related to bone loss in ovariectomized rats. Brain Res Bull. 2021, 176, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrijantini, N.; Suisan, Y.C.; Megantara, R.W.A.; Tumali, B.A.S.; Kuntjoro, M.; Ari, M.D.A.; Sitalaksmi, R.M.; Hong, G. Bone Remodeling in Mandible of Wistar Rats with Diabetes Mellitus and Osteoporosis. Eur J Dent. 2023, 17, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroso, A.L.; Canal, R.; Gehrke, S.A.; da Costa, E.M.; Scarano, A.; Zanelatto, F.B.; Pelegrine, A.A. The Validation of an Experimental Model in Wistar Female Rats to Study Osteopenia and Osteoporosis. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, S.N.M.; Hashim, N; Isa, I.M.; Bakar, S.A.; Saidin, M.I.; Ahmad, M.S.; Mamat, M.; Hussein, M.Z.; Zainul, R. The impact of a hygroscopic chitosan coating on the controlled release behaviour of zinc hydroxide nitrate–sodium dodecylsulphate–imidacloprid nanocomposites. New J. Chem 2020, 44, 9097–9108. [CrossRef]

- García-Gareta, E.; Coathup, M.J.; Blunn, G.W. Osteoinduction of bone grafting materials for bone repair and regeneration. Bone. 2015, 81, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.W.; Yu, S.H.; Fretwurst, T.; Larsson, L.; Sugai, J.V.; Oh, J.; Lehner, K.; Jin, Q.; Giannobile, W.V. Maresin 1 Promotes Wound Healing and Socket Bone Regeneration for Alveolar Ridge Preservation. J Dent Res. 2020, 99, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Distribution of study subjects (Wistar rats) in the study.

Figure 1.

Distribution of study subjects (Wistar rats) in the study.

Figure 2.

(a) bone defect; (b) membrane placement;(c) the defect closed by suturing the flap.

Figure 2.

(a) bone defect; (b) membrane placement;(c) the defect closed by suturing the flap.

Figure 3.

SEM images of various magnification (A-B) illustrating chitosan nanostructured mem- branes with periodic grooves of 242±8 nm width and 200 nm depth (inset

Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

SEM images of various magnification (A-B) illustrating chitosan nanostructured mem- branes with periodic grooves of 242±8 nm width and 200 nm depth (inset

Figure 3A).

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of the results of the determination of bone biomarkers: A. Osteocalcin (OC), B. Beta-Crosslaps (β-CTX).

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of the results of the determination of bone biomarkers: A. Osteocalcin (OC), B. Beta-Crosslaps (β-CTX).

Figure 5.

Descriptive histopathological findings in the area of the bone defect: a. Group I – after 1 month - Lack of bone tissue with a rim of dense, fibrous connective tissue and a central void (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20X); b. Group II – after 1 month - dense fibrous connective tissue, rich in plump, metabolically active fibroblasts (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20X); c. Group III - after 1 month- association of dense irregular connective tissue and osseous tissue (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20X); d. Group III - after 2 months - osseous tissue (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20X).

Figure 5.

Descriptive histopathological findings in the area of the bone defect: a. Group I – after 1 month - Lack of bone tissue with a rim of dense, fibrous connective tissue and a central void (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20X); b. Group II – after 1 month - dense fibrous connective tissue, rich in plump, metabolically active fibroblasts (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20X); c. Group III - after 1 month- association of dense irregular connective tissue and osseous tissue (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20X); d. Group III - after 2 months - osseous tissue (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20X).

Figure 6.

Representative microscopic images from the area of the bone defect, comparing different aspects of bone regeneration: a. Histological aspect one month after executing the bone defect, demonstrating a thin, delicate bone bridge with a limited number of thin trabeculae - arrow (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, magnification 20 X) and b Histological aspect 2 months after performing the bone defect, with a thick bone bridge, with wider bone trabeculae displaying a rim of osteoblasts- arrow (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20 X). In both examples, the space between the bone tissue is occupied by a well-vascularized dense irregular connective tissue.

Figure 6.

Representative microscopic images from the area of the bone defect, comparing different aspects of bone regeneration: a. Histological aspect one month after executing the bone defect, demonstrating a thin, delicate bone bridge with a limited number of thin trabeculae - arrow (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, magnification 20 X) and b Histological aspect 2 months after performing the bone defect, with a thick bone bridge, with wider bone trabeculae displaying a rim of osteoblasts- arrow (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, 20 X). In both examples, the space between the bone tissue is occupied by a well-vascularized dense irregular connective tissue.

Figure 7.

Group I- after 1 month- dense, fibrous irregular connective tissue fills the bone defect area along an abrupt border of the osseous tissue. The dense connective tissue displays a high cellularity, with numerous fibroblasts and a rich, diffuse capillary network, that can be identified throughout the surface of the section, in both the periphery and the central part of the graft area. Low amounts of chronic immune cells and erythrocyte extravasation are also noted (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, magnification 20 X).

Figure 7.

Group I- after 1 month- dense, fibrous irregular connective tissue fills the bone defect area along an abrupt border of the osseous tissue. The dense connective tissue displays a high cellularity, with numerous fibroblasts and a rich, diffuse capillary network, that can be identified throughout the surface of the section, in both the periphery and the central part of the graft area. Low amounts of chronic immune cells and erythrocyte extravasation are also noted (Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, magnification 20 X).

Figure 8.

Group III- 1 month- sequestrum, a hallmark of osteomyelitis, displazying nonviable bone encircled by a dense inflammatory infiltrate rich in polymorphonucleated neutrophils. The bone fragment is separated from the surrounding osseous tissue (arrow): a. Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, magnification 5X; b. Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, magnification 10X.

Figure 8.

Group III- 1 month- sequestrum, a hallmark of osteomyelitis, displazying nonviable bone encircled by a dense inflammatory infiltrate rich in polymorphonucleated neutrophils. The bone fragment is separated from the surrounding osseous tissue (arrow): a. Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, magnification 5X; b. Hematoxylin and Eosine stain, magnification 10X.

Table 1.

Histopathological assessment and scoring of samples, with emphasis on the bone defect area and alterations induced by the synthetic graft.

Table 1.

Histopathological assessment and scoring of samples, with emphasis on the bone defect area and alterations induced by the synthetic graft.

| No. |

Parameter |

Score |

Microscopic aspect |

| 1. |

Osteoporosis |

0 |

Not discernable |

| 1 |

Subtle |

| 2 |

Evident |

| 2. |

Bone formation at the surface of the graft |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present at the periphery |

| 2 |

Present in the center |

| 3 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| 3. |

Bone formation in the graft area |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present in the surface of the graft area |

| 2 |

Present in the center of the graft area |

| 4. |

Bone bridge |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Thin |

| 2 |

Thick |

| 5. |

Bone trabeculae |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present at the periphery |

| 2 |

Present in the center |

| 3 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| 6. |

Immature bone |

0 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| 1 |

Present in the center |

| 2 |

Present at the periphery |

| 3 |

Absent |

| 7. |

Mature bone |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present at the periphery |

| 2 |

Present in the center |

| 3 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| 8. |

Osteoblasts |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present at the periphery |

| 2 |

Present in the center |

| 3 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| 9. |

Osteocytes |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present at the periphery |

| 2 |

Present in the center |

| 3 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| 10. |

Osteoclasts |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present at the periphery |

| 2 |

Present in the center |

| 3 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| 11. |

Havers canals |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present at the periphery |

| 2 |

Present in the center |

| 3 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| 12. |

Inflammation |

0 |

Present, abundant |

| 1 |

Present, scant |

| 2 |

Absent |

| 13. |

Vascularization |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present in the surface of the graft area |

| 2 |

Present in the center of the graft area |

| 14. |

Granulation tissue |

0 |

Present |

| 1 |

Absent |

| 15. |

Graft |

0 |

Detected |

| 1 |

Not detected |

| na |

Not applicable |

| 16. |

Osteoclastic degradation of the graft |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present at the periphery |

| 2 |

Present in the center |

| 3 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| na |

Not applicable |

| 17. |

Replacement of graft by mature bone |

0 |

Absent |

| 1 |

Present at the periphery |

| 2 |

Present in the center |

| 3 |

Present at the periphery and in the center |

| na |

Not applicable |

Table 2.

Levels of bone biomarkers.

Table 2.

Levels of bone biomarkers.

| Bone Biomarkers |

T0 |

T1 |

| Ostecalcin [ng/ml] |

2.265 ± 0.85 |

4.279 ± 1.96 |

| β-crosslaps [ng/ml] |

4609.103 ± 2214.88 |

9842.555 ± 4766.71 |

Table 3.

The final scores of the groups using the healing score (histological parameters).

Table 3.

The final scores of the groups using the healing score (histological parameters).

| Hisological bone healing parameters |

Group frequency (%) |

| Gr. I-1 |

Gr. I- 2 |

Gr. II- 1 |

Gr. II- 2 |

Gr. III- 1 |

Gr. III- 2 |

| Osteoporosis |

not discernable |

0 |

0 |

0,67 |

0,67 |

0,67 |

0,67 |

| subtle |

0,5 |

1 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

| evident |

0,5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Bone formation at the surface of the graft |

absent |

0 |

0,17 |

0,1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| peripheral |

0,6 |

0,83 |

0,4 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0,34 |

| central |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central and peripheral |

0,4 |

0 |

0,5 |

0,67 |

0,67 |

0,67 |

Bone formation

in the depth of the graft |

absent |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| surface |

0 |

0 |

0,3 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0,17 |

| profound |

0 |

0 |

0,7 |

0,67 |

0,67 |

0,83 |

| Bone bridge |

absent |

0,8 |

1 |

0 |

0,17 |

0,17 |

0,17 |

| thin |

0,2 |

0 |

0,6 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0,16 |

| thick |

0 |

0 |

0,4 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

0,67 |

| Bone trabeculae |

absent |

0 |

0,17 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| peripheral |

0,8 |

0,83 |

0 |

0,17 |

0,17 |

0,33 |

| central |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central and peripheral |

0,2 |

0 |

1 |

0,83 |

0,84 |

0,67 |

| Immature bone |

absent |

0,2 |

0 |

0,4 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

0,33 |

| peripheral |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central |

0,8 |

1 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

| central and peripheral |

0 |

0 |

0,1 |

0 |

0 |

0,17 |

| Mature bone |

absent |

0,3 |

0,33 |

0,1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| peripheral |

0,4 |

0,67 |

0,7 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

0,33 |

| central |

0,1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central and peripheral |

0,2 |

0 |

0,2 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

0,67 |

| Osteoblasts |

absent |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| peripheral |

0,6 |

1 |

1 |

0,2 |

0,5 |

0,33 |

| central |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central and peripheral |

0,4 |

0 |

0 |

0,8 |

0,5 |

0,67 |

| Osteocytes |

absent |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| peripheral |

0,6 |

1 |

0 |

0,17 |

0,17 |

0,33 |

| central |

0 |

0 |

0,1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central and peripheral |

0,4 |

0 |

0,9 |

0,83 |

0,833 |

0,67 |

| Osteoclasts |

absent |

0,6 |

0,83 |

0,9 |

1 |

1 |

0,5 |

| peripheral |

0,4 |

0,17 |

0,1 |

0 |

0 |

0,5 |

| central |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central and peripheral |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Havers canal |

absent |

0,7 |

1 |

0 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0 |

| peripheral |

0,2 |

0 |

0,1 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

| central |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central and peripheral |

0,1 |

0 |

0,9 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0,67 |

| Inflammation |

present, abundant |

0,1 |

0,17 |

0 |

0,17 |

0,17 |

0 |

| present, scant |

0,5 |

0,33 |

0,1 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0,17 |

| absent |

0,4 |

0,5 |

0,9 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

0,83 |

| Vascularization |

absent |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| surface of the graft |

0,4 |

0,67 |

0,5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| depth of the graft |

0,6 |

0,33 |

0,5 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Granulation tissue |

absent |

0 |

0,5 |

0,1 |

0,33 |

0,33 |

0 |

| present |

1 |

0,5 |

0,9 |

0,67 |

0,67 |

1 |

| Graft |

detected |

na |

na |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| not detected |

na |

na |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| not applicable |

na |

na |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Osteoclast degradation

of the scaffold |

absent |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| peripheral |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0,5 |

0,33 |

| central |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central and peripheral |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0,5 |

0,667 |

Scaffold replacement

with mature bone |

absent |

na |

na |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| peripheral |

na |

na |

0,7 |

1 |

0,5 |

0,33 |

| central |

na |

na |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| central and peripheral |

na |

na |

0,3 |

0 |

0,5 |

0,67 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).