1. Introduction

1.1. Water Security Challenges and the Need for ICT Integration

Water scarcity and degradation have emerged as global challenges that threaten ecosystems, economic development, and human well-being. Increasing demographic pressures, unsustainable consumption patterns, and the intensifying impacts of climate change exacerbate the imbalance between water availability and demand, placing water security at the center of sustainability debates [

1,

2]. Addressing these issues requires integrated approaches that consider the hydrological cycle as a whole and adopt the watershed as the fundamental territorial unit for planning and management.

Watershed-based management allows for the integration of environmental, social, and economic factors by focusing on hydrological rather than administrative boundaries. Within this framework, water generation, storage, abstraction, treatment, distribution, reuse, and the impacts of human activities are considered in a systemic manner. Effective watershed management is, therefore, crucial for safeguarding water resources for present and future generations. In Brazil, for example, the National Water Resources Policy (Law Nº 9.433/1997) [

3] established watershed management as a core principle, promoting decentralized and participatory governance through Watershed Committees and long-term strategic planning instruments. Although specific to the Brazilian context, this example illustrates how the watershed scale has been institutionalized as a critical arena for sustainable water governance.

Central to this governance structure is the use of indicators derived from continuous data collection. Indicators translate raw data into simplified and accessible information, enabling managers to monitor water consumption, demand, and quality, and to anticipate risks associated with scarcity and degradation. Beyond their technical role, governance indicators also provide diagnostic value for assessing the performance of water policy regimes and identifying institutional weaknesses, making them indispensable tools to enhance adaptive and sustainable water governance [

4]. In this sense, comprehensive and interdisciplinary assessment frameworks, such as the “sustainability wheel,” highlight how indicators can integrate hydrological, ecological, social, and institutional dimensions, offering a holistic perspective to evaluate and strengthen water governance systems [

5]. Sustainable water management depends on the availability of robust and up-to-date information on both the quantity and quality of water bodies, ensuring that decision-making processes are based on reliable evidence.

However, current monitoring systems often face limitations related to the volume, quality, and timeliness of available data. Traditional Water Quality Indices (WQIs), although widely used to synthesize complex information into a single communicable metric, frequently presents shortcomings associated with parameter selection, subjectivity in classification schemes, and rigidity in adapting to local contexts. These challenges can undermine their diagnostic power and hinder their effectiveness in supporting decision-making, particularly in regions with diverse environmental and socio-economic conditions [

6]. This creates a gap between the demand for precise and continuous information and the capacity of traditional tools to supply it. To overcome this challenge, Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), including the Internet of Things (IoT) [

7], Big Data, Artificial Intelligence (AI) [

8], and Business Intelligence (BI) [

9] have been increasingly explored for their potential to enhance the collection, processing, and analysis of water-related information. Recent studies highlight that IoT devices, when combined with Machine Learning algorithms, enable real-time monitoring, predictive analytics, and early warning systems for water quality management, offering a cost-effective and scalable alternative to conventional methods. These technologies offer opportunities to strengthen water security indicators, provide real-time insights, and support adaptive and sustainable management practices.

This study aims to systematically review and synthesize recent scientific literature on the applications of ICT in water resource management, emphasizing their potential to enhance water security and promote sustainable practices. By combining bibliometric and qualitative approaches, the review identifies emerging trends, technological synergies, and persistent barriers, providing insights into how ICTs can contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to water.

1.2. Specific ICT Applications for Sustainable Water Resource Management

The integration of ICTs into water resource management can be understood across three complementary domains: monitoring, data processing, and decision-making support.

One first set of tools focuses on

environmental monitoring and sensing. Remote sensing enables the acquisition of information from hydrological systems without direct contact, providing large-scale and continuous coverage through orbital or aerial platforms [

10]. Complementarily, the Internet of Things (IoT) establishes networks of sensors that collect and transmit real-time data, expanding the capacity to monitor local variations in water quantity and quality [

11]. Together, these technologies address one of the main challenges in water governance: the scarcity of reliable and continuous data.

A second domain relates to

data storage, processing, and analytics. Big Data approaches encompass strategies for data extraction, modeling, and predictive algorithm development, enabling the handling of large, heterogeneous datasets [

12]. Data Mining adds value to this process by uncovering hidden patterns in extensive databases, thereby accelerating knowledge discovery and supporting decision-making [

13]. Business Intelligence (BI) builds upon these analytical capacities to generate reports and insights from organizational data, directly contributing to more transparent and evidence-based management [

14].

Finally, a third group of ICTs enhances

decision-making and predictive modeling. Artificial Intelligence (AI) comprises models and techniques for knowledge representation, perception, planning, and machine learning [

15]. Within this field, Machine Learning algorithms detect patterns from large datasets and predict outcomes [

16, 17], while Neural Networks replicate brain-like learning processes to improve supervised and unsupervised tasks [

18]. Deep Learning has advanced the discovery of complex data structures and improved predictive performance [

19]. Decision Support Systems (DSS) combine these analytical advances with user-oriented tools that facilitate scenario evaluation and policy optimization [

20]. Emerging technologies such as Machine Vision [

21], Virtual Reality, and Augmented Reality [

22], although still underexplored in water governance, hold potential to enhance participatory processes and improve communication of hydrological complexities to stakeholders.

Taken together, these technologies illustrate not only the diversification of ICT applications but also their synergistic role in addressing data limitations, strengthening monitoring, and supporting adaptive and sustainable water governance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Characterization

This study is characterized as a descriptive, document-based research project with an exploratory and applied nature. Given the limited literature on the application of innovative Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in watersheds, the primary objective is to generate knowledge for future investigations [

23]. This focus on generating knowledge and identifying potential applications directly aligns with

Sustainability's interest in

defining and quantifying sustainability.

To identify relevant literature, this study employed bibliometric analysis. This quantitative approach systematically analyzes fundamental elements across various fields of study and is crucial for investigating literature related to factors that influence the search for innovative ICT applications. These ICT applications can be effectively implemented in the sustainable management of water resources, offering several significant contributions [

24]. This method is relevant to the journal's focus on

sustainability tools.

Bibliometrics, a statistical and quantitative approach, focuses on generating indicators about the production and dissemination of scientific knowledge [

25]. This technique enables the quantification of scientific knowledge through the analysis of publication patterns, examining aspects such as authorship and research behaviors in specific areas [

26], in addition to exploring the dynamics of publication and the authors involved [

27].

The theoretical contributions of Lotka, Bradford, Zipf, and Price provide essential foundations for bibliometrics [

28]. Lotka presented the law of the inverse, which applies to the evaluation of author productivity [

29]. Bradford explored the dispersion of authors among various publications [

30]. Zipf's law analyzes the frequency of words in extensive texts [

31], while Price focused on the dynamics of scientific activity. These laws help to provide a quantitative framework for assessing and understanding the dynamics of research in this area.

The bibliometric analysis applied in this study aims to detect research trends and emerging themes in the literature on innovative ICT and the sustainable management of water resources. It allows researchers and managers to identify areas of greater relevance and gaps that still need attention. This methodology analyzes the evolution of themes and trends over time, assisting in understanding changes in research and in identifying points of inflection and emerging themes [

32]. The analysis of keywords in articles, for example, makes it possible to identify patterns of co-occurrence, highlighting the main themes and research topics related to the challenges of sustainable water resource management [

33]. The ability to detect emerging trends is key for adaptive management of water resources.

The analysis of citations in scientific articles is crucial for understanding the influence of specific works and authors in the area. It is fundamental for researchers to identify relevant contributions and essential references for the advancement of knowledge. The methodology maps the network of knowledge, helping to recognize which authorships and studies exert greater influence and revealing gaps that still demand investigation [

34]. This emphasis on knowledge mapping aligns with the journal's interest in

sustainability science.

In this study, bibliometric analysis was applied with the purpose of verifying and quantifying the production of academic articles that addressed themes and contents about how innovative ICT applications can be effectively implemented in water resource management and in ensuring water security. In addition to the theoretical basis, the research included numerical treatment and statistical analysis of data, using the VosViewer software, which made possible, later, a more in-depth qualitative investigation [

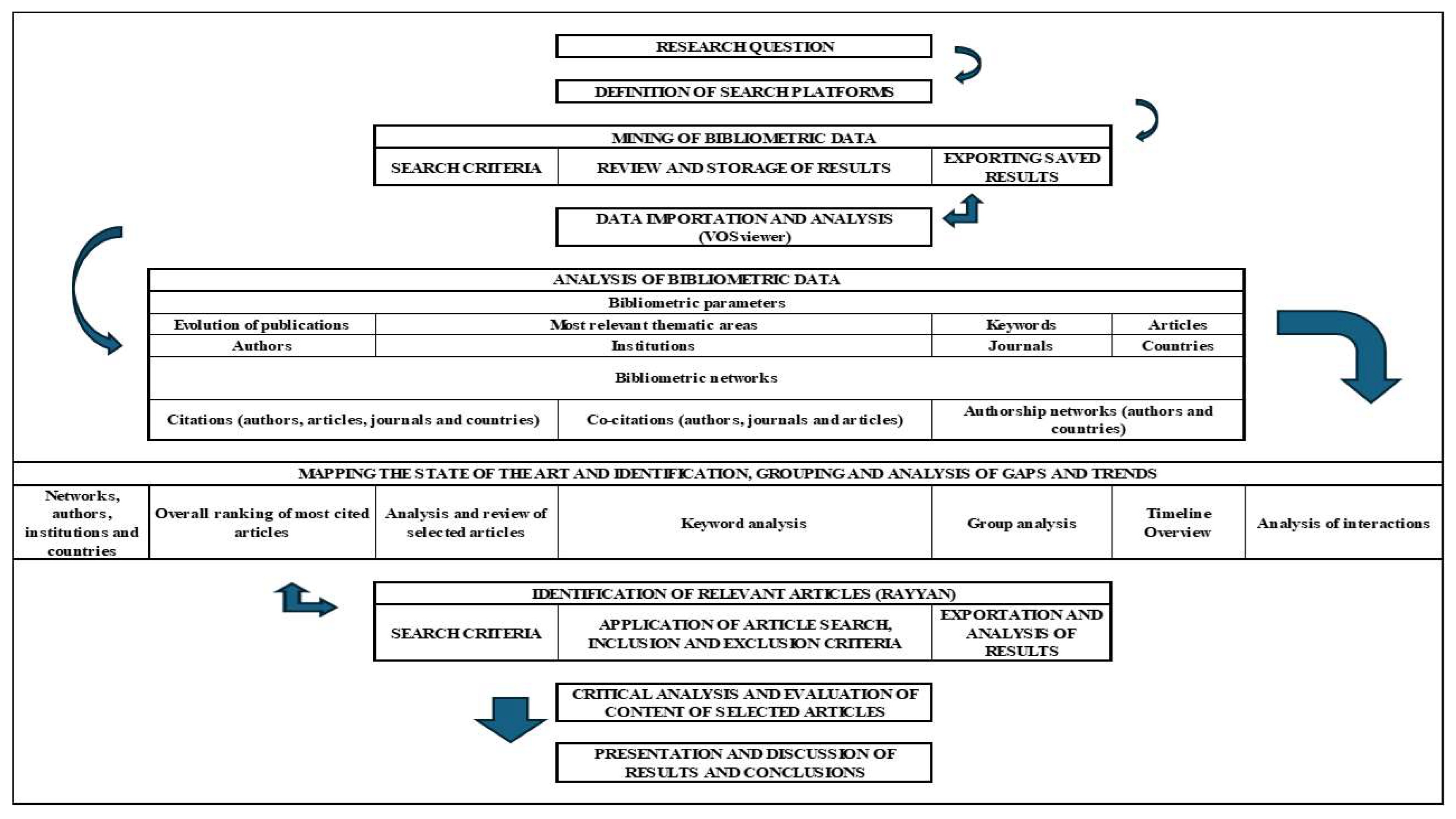

35], as illustrated in

Figure 01.

The second part of the methodology involved a qualitative analysis of the selected studies to evaluate their contributions to the proposed research questions. The use of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology, specifically developed for the elaboration of systematic reviews [36, 37], facilitated a thorough evaluation of existing research, allowing an effective categorization of studies focused on the interactions between ICT and water resources management, evaluating their impacts through the analysis of the identified keywords.

2.2. Data Collection and Selection

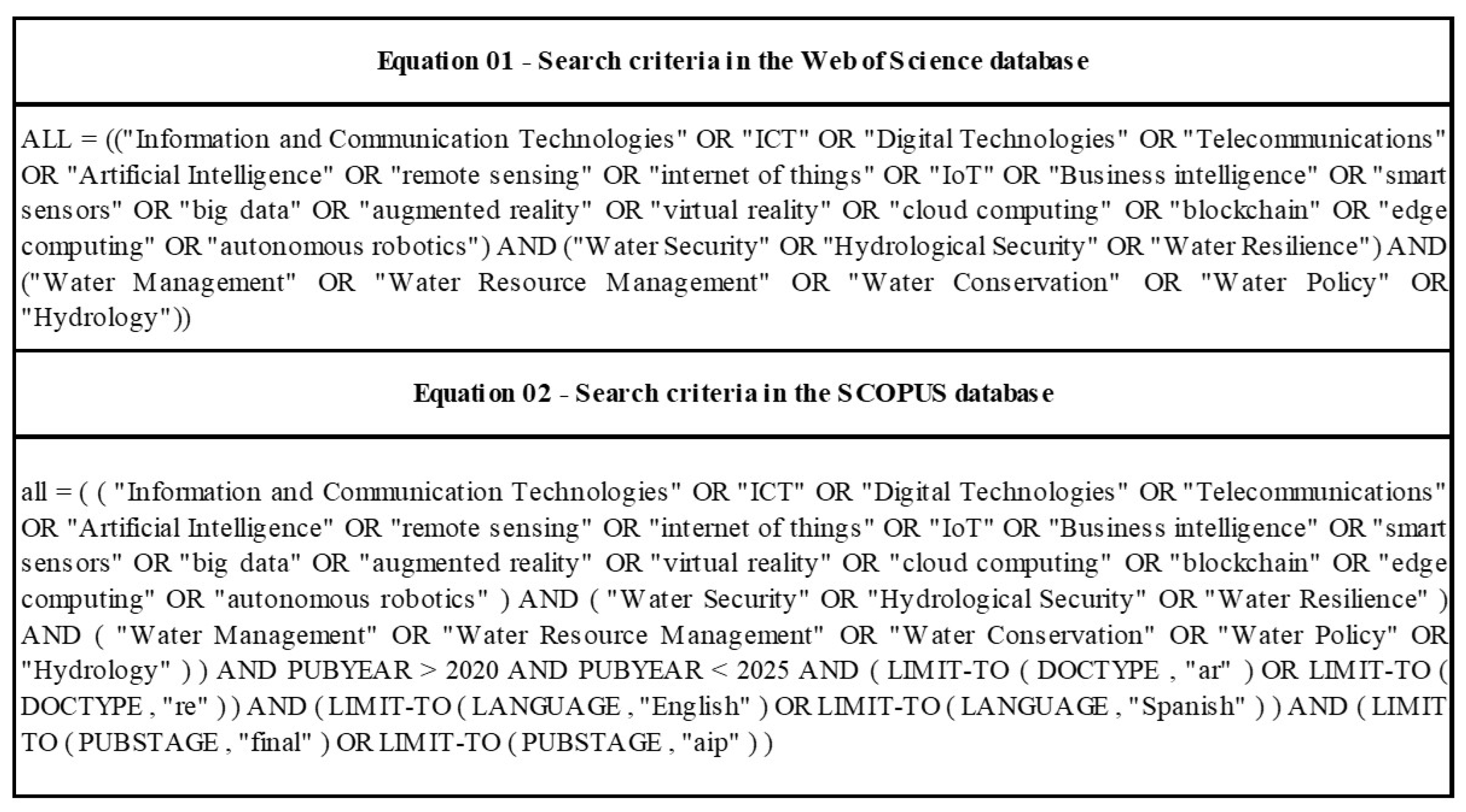

Studies that address innovative technologies related to water security were considered eligible for this research. The selection of primary sources was based on scientific articles published in the last five years (2020 to 2024) in English. The search was performed in the Web of Science and Scopus databases, using Boolean expressions with relevant key descriptors and their semantic variations, as shown in

Figure 2:

The information extracted from the selected articles included data on authors, titles, abstracts, and journals, and was organized in the Zotero bibliographic reference management platform.

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

The search for articles was conducted independently by four researchers and analyzed with the aid of the VOSViewer and Rayyan software.

The first analysis of a quantitative nature consisted of the identification of the co-occurrences of the main terms or keywords. For this, the data processed in the Zotero platform were imported into the VOSviewer Software, using the RIS format.

The second analysis of a qualitative nature involved the export of previously selected articles and organized in the Zotero platform to RAYYAN [

38], a tool designed to assist in systematic reviews. This platform allowed the selection of articles based on the keywords chosen for inclusion, restricting the analysis to the population and outcomes of the articles evaluated, according to the interests of the research. After reading and analyzing the material, only the articles pertinent to the limits of the research were considered, since they addressed the presence and use of ICT related to water security and management.

3. Results

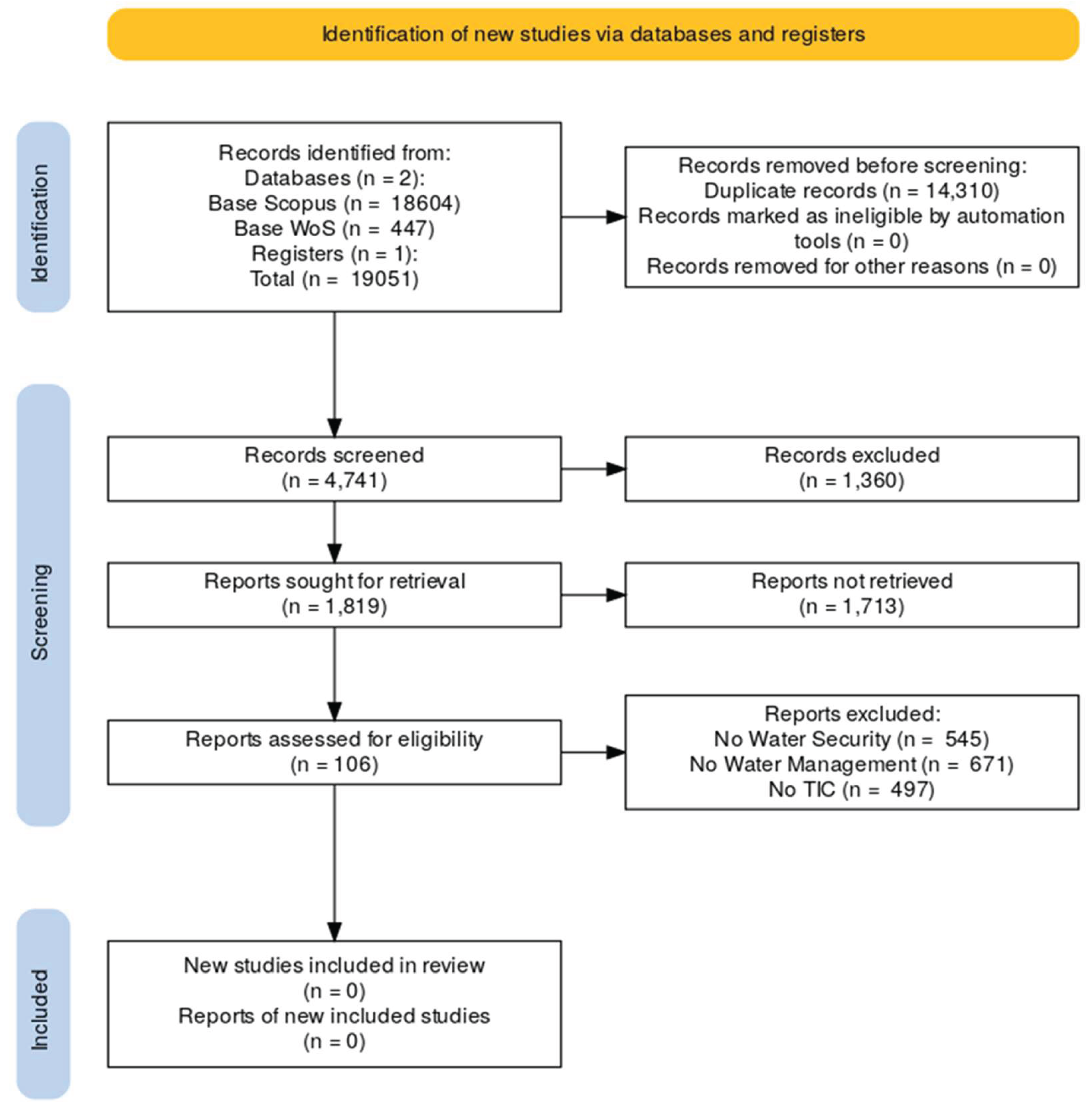

The search performed in the Web of Science database identified 447 articles independently by 04 researchers, while the Scopus database yielded 18,604 articles. All articles were processed using Zotero and the Rayyan platform, available at

https://new.rayyan.ai/reviews/1037979/overview. From the total of 19,051 articles collected, 14,310 were eliminated as duplicates, leaving 4,741 for preliminary analysis. This transparent and reproducible search strategy is crucial for ensuring the reliability of the research.

3.1. Analysis of Keywords

The keyword analysis performed in the VosViewer software initially considered a set of 2,800 distinct words, extracted from the 4,741 articles collected. Using a selection criterion based on the semantic association of the keywords with the general concepts linked to Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), a list of 28 relevant terms was compiled by the expert authors in the ICT area, as detailed in

Table 1. This selection process ensures that the analysis focuses on the most relevant technologies for sustainable water management.

As can be observed in

Table 1, the selection of keywords reflects the centrality and relevance of certain concepts within the analyzed corpus, which covers a broad spectrum of Information and Communication Technologies applied to water resources management. The table highlights the prevalence of themes such as 'machine learning', with a significantly high occurrence weight (336), indicating not only the frequency with which this term appears but also its importance in the current discussion on advanced technologies in water resources management. This is in line with the journal's focus on innovative technologies.

Another relevant aspect is the distribution of keywords by clusters, or thematic categories. Thus, as an example, the terms within cluster 6, such as 'artificial intelligence', 'neural networks', and 'deep learning', which have high connection weights (966, 756, and 125 respectively), illustrate an intense focus on the application of advanced AI techniques in analysis and modeling in water management. This cluster, notably, deals with concepts that are crucial for the development of innovative solutions in predictive and automated technologies.

The presence of terms such as 'geographic information system' in cluster 4 with a connection weight of 485 demonstrates the importance of geolocalization and spatial analysis, which are fundamental for the effective implementation of water resource management on a broader and more detailed scale. In addition, the term 'cloud computing' in the same cluster with a connection weight of 227 reflects the growing integration of cloud-based platforms for the processing and storage of large volumes of water data.

Preliminarily, the analysis of these keywords not only identifies the predominant and emerging technologies but also highlights the research trends and potential areas for future investigations, as exemplified by terms such as 'fuzzy systems' and 'intelligent systems' with occurrence weights of 12 and 18, respectively. These emerging areas can provide valuable insights into future directions for sustainable water management.

3.2. Content Analysis of Relevant Articles

In the RAYYAN platform (available at

https://new.rayyan.ai/reviews/1037979/overview), of the 19,051 documents initially analyzed, 14,310 were identified as duplicates and automatically excluded, leaving 4,741 for initial analysis. Collaboratively, the authors discarded 2,922 articles whose abstracts did not contain the selected keywords, as indicated in

Table 1. Of the 1,819 articles remaining, 1,360 were eliminated for not presenting the keywords "water security", "water management" and the ICT in association. At the end of this screening process, 106 articles were considered potentially relevant and were submitted to the analysis of the full text to determine their eligibility, as illustrated in

Figure 3. This rigorous screening process ensures that the selected articles are highly relevant to the research question.

After reading and detailed analysis of the articles, 17 publications that effectively addressed the main innovative technologies applied to water security were selected. With the objective of gathering academic information and systematizing it for the elaboration of a document that specifies innovative Information and Communication Technologies, already in use or with potential for application in the task of automated monitoring of water security, we present the contribution of each of the seventeen selected articles, as described in

Table 2. This systematization provides a valuable resource for researchers and practitioners.

4. Discussion

This section presents a discussion and interpretation of the results. For clarity and systematization, the findings are organized by innovative technology: Remote Sensing enhanced with Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications, IoT with Big Data and/or Decision Support Systems (DSS), applications using only AI, and applications integrating IoT with AI. For each category, the applications, potential benefits, and limitations are described.

a) Remote Sensing Enhanced with Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Four relevant studies were identified in this category:

Raghul & Porchelvan [

39] describe a method for determining the concentration of optically active components in the upper layer of a water body, estimating water quality. This study highlights advancements in remote sensing technology, complemented by machine learning techniques to improve the accuracy and temporal applicability of models. However, the authors point out that the models are typically based on

in situ data and may not capture long-term trends and variations. This highlights the need for integrating diverse data sources to improve model robustness.

Matsui et al. [

40] proposes a method to estimate the spatial distribution of suspended solids and the nitrogen-phosphorus ratio, important indicators of water quality. The study combines satellite remote sensing data, water depth, and temperature to estimate phytoplankton conditions in water bodies, contributing to a better understanding of aquatic ecology. The proposed method significantly reduced the average error of suspended solids estimation to 4 mg/L. The results highlight the utility of the method in simulating complex water quality conditions, even with recreated data and in scenarios of scarce data. However, the study was unable to specifically identify the phytoplankton species present. This suggests the need for further research to improve the specificity of the models.

Souza et al. [

41] use remote sensing and machine learning to identify turbidity anomalies in the Três Marias reservoir, Brazil. The model was able to accurately identify regions with high turbidity, which is useful for large reservoirs and difficult-to-access regions. For the authors, the model is sensitive to climatic problems where the presence of clouds makes it difficult to capture satellite images, a well-known limitation in the use of images captured by remote sensing, especially orbital. This highlights the challenge of using remote sensing in regions with frequent cloud cover.

Guo et al. [

42] developed and validated Deep Learning models using reflectance data from remote sensing, along with synchronized measurements of water quality, to estimate the concentration of Chlorophyll-a, total phosphorus, and total nitrogen. The study was applied to Lake Simcoe in Canada and demonstrated the ability to make adequate estimates. However, the authors note that the performance of the model depends heavily on the quality and quantity of the data available, and that the lack of validation data from other water bodies may compromise the generalization of the results. This underscores the need for more comprehensive data collection and validation across diverse water bodies.

In addition to these, two works applied remote sensing and AI technologies to the study of groundwater. Nguyen et al [

43] developed a study in the North and Central region of Vietnam that can be improved with the integration of factors such as the rate of exploitation of groundwater resources, the quality of groundwater, the level of groundwater, among others, to predict the future potential of groundwater, to optimize the distribution of water resources. The authors point out that the machine learning model cannot be applied to domains outside the training range of the model and that in the prediction of future potential there is a strong influence from climate change and population growth.

Saha et al. [

44] presents a study to model and map the spatial variability of groundwater resources, along with the control dynamics of aquifers in urban and peri-urban areas. For the authors, the limitations include the accuracy of the data, since the DEM and field satellite data come from different platforms and scales, which may affect the location of the base layers and the lack of a detailed soil map on a scale of 1:50,000 also limits the accuracy of the forecasts.

An interesting work was found using remote sensing and AI applied to surface waters. Sun et al [

45] proposes a new framework for detection of river barriers, capable of identifying different types of infrastructures in rivers from satellite images. The study identified 11,864 valid barriers in the Lower Mekong (river in Asia), including dams, gates and weirs, which with the integration of data, the total reached 13,054 barriers, reaching the average accuracy of 86.7%. The authors report limitations regarding the quality of satellite images, as well as possible limitations in generalization to other regions with different environmental characteristics.

Finally, a work was found using remote sensing and AI applied to the monitoring of hydrographic basins. Al-Abadi et al [

46] present a study to map the susceptibility to drought in Iraq. It was used data from anomalous storage of terrestrial water from the GRACE satellite, combined with meteorological and topographical factors such as temperature, precipitation, wind speed, evapotranspiration and others, as input for the creation of five machine learning models, which presented high accuracy.

b) IoT with Big Data and/or DSS

Three analyzed studies used IoT and the concepts of DSS and/or Big Data.

The first of these is the work of Reljić et al [

47], which presented the Automated Continuous Monitoring System (ACMS) applied in the delta of the Neretva River, Croatia, which monitors water quality, soil salinity, surface water regime and climatic conditions with several sensors in real time. The authors emphasize that the data from each sensor was collected in real time with high temporal resolution and were managed through a database and a web portal, allowing the detection of sudden changes in water quality parameters because of natural and anthropogenic influences. This real-time monitoring is essential for adaptive management.

Jiang et al [

48] implemented a pilot system on the Maozhou River in Shenzhen, China, to improve water quality management in urban environments by combining sensors and model. According to the authors, the application proved to be efficient for monitoring large-scale water systems by offering early warning functions and identification of pollution sources. However, the authors observe that the model presented limitations in the identification of multi-source pollution incidents due to the similarity of pollutants emitted by industries. This highlights the challenge of accurately identifying pollution sources in complex urban environments.

Batista et al (2023) [

49] presents a methodology to automate the sustainable management of water in buildings by integrating the BIM (Building Information Modeling) model, IoT (Internet of Things) devices and facility management (FM) tools. The research presented a functional prototype, AquaBIM, which uses real-time data to improve efficiency in water consumption, identify leaks and support strategic decisions. For the authors, the initial cost and the need for technical training to operate AquaBIM are also barriers to its widespread adoption. The methodology still requires validation in different types of buildings and operational contexts. This underscores the importance of considering both the technical and economic feasibility of these solutions.

c) Applications Using Only AI

The following are four works that present AI applications, three of them applied to groundwater and one related to erosion detection.

Jung; Saynisch-Wagner & Schulz [

50] explore extensive data sets to elucidate the mechanisms of groundwater recharge on a global scale and improve the accuracy of estimates, using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to interpret the behavior of the recharge model. The authors identify non-linear relationships between the predictors and recharge rates, highlighting challenges such as multicollinearity, biases in the data and limitations in observational data, especially in less monitored areas, such as the polar regions. This highlights the need for improved data collection in underserved regions.

Sarkar (2024) [

51] maps the potential of groundwater in climate variability scenarios in Bangladesh. Given the complexity of aquifer recharge, influenced by factors such as rainfall intensity and soil characteristics, the accuracy of the maps can be challenging. The use of machine learning models requires attention to their limitations, including inherent assumptions and potential biases. This reinforces the need for careful validation and calibration of these models.

Xu et al, (2022) [

52] evaluates the relationship between erosion in ravines and environmental factors. Using three hybrid machine learning models (FR-RF, FR-SVM and FR-NB) to map susceptibility to erosion, the authors demonstrated the applicability of the approach in areas with similar environmental and anthropogenic conditions, such as those characterized by irregular rainfall, sloping terrain and fragile geology. This demonstrates the potential of machine learning for predicting and mitigating erosion risk.

d) Applications Integrating IoT and AI

The following are three works that address the application of AI and IoT sensors, one of them applied to water quality and another related to surface waters.

Lu et al [

53] present the Bacterial Risk Control System (BARCS), applied in a Chinese megacity. The system uses AI to predict the bacterial risk in urban water distribution systems, based on water quality parameters. BARCS acts on the regulation of the concentration of chlorine at the outlet of the treatment station, aiming to control the risks of bacteria and disinfection by-products. The authors point out that the study has limitations, such as the need to improve the relationships between TCl, bacterial risks and DBPs with a wider database, which restricts the generalization of the results. In addition, they highlight the importance of developing more advanced AI models, such as deep learning, to deal with more diverse and larger volumes of data, as well as optimizing the network of online monitoring sensors to increase accessibility and reduce the costs of the system. This highlights the need for continued innovation in both sensor technology and AI algorithms.

Benhmad et al [

54] propose an innovative approach to intelligent irrigation for southern Tunisia, based on the implementation of an IoT sensor network combined with artificial intelligence. The main objective is to optimize the efficiency in the use of water resources and accurately estimate the water needs of date palms. This smart irrigation system has the potential to significantly improve water use efficiency in arid regions.

Petri et al [

55] presents an intelligent analysis system to optimize the real-time management of watersheds and water resources. The system employs AI to predict the level of rivers, flow and precipitation. The authors report that the system achieved 93% accuracy in predicting the levels of rivers and water flow in the Usk River, Wales. However, they point out that the accuracy and effectiveness of the system depend on the availability of data in real time, which requires high-quality sensors and adequate coverage, as well as a sophisticated level of computing power. This underscores the importance of investing in both sensor infrastructure and computational resources to support effective real-time water management.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically reviewed the application of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in water resource management, emphasizing their potential to enhance water security and promote sustainable practices. Through a combination of bibliometric and qualitative analyses, the research identified key trends in the literature, focusing on innovative technologies like remote sensing, artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and Big Data. The study demonstrates that these technologies offer significant potential for improving water resource monitoring, management, and governance.

The literature review revealed a prominent focus on remote sensing coupled with AI for water quality monitoring, allowing for early detection of potential problems and enabling rapid, data-driven decision-making. Moreover, this approach overcomes limitations associated with traditional in situ data collection, especially in remote and complex watersheds. This highlights the potential of these technologies to support adaptive water management strategies, a crucial element for addressing the challenges posed by climate change and increasing water scarcity.

However, the study also identified significant gaps and limitations in the current research landscape. The lack of real-world testing across diverse geographical contexts, the underutilization of emerging technologies like data mining and virtual reality, and the challenges associated with data integration and validation all represent opportunities for future investigation. Addressing these gaps is crucial for realizing the full potential of ICT in promoting sustainable water resource management.

Future investigations should focus on expanding the application of these technologies to different regions and geographical scales, examining robustness and adaptability to varied environmental and operational contexts, and addressing the challenges of integrating data from multiple sources, to ensure the reliability and quality of the information. Specifically, future research should examine the application of underutilized technologies such as data mining, machine vision, and virtual reality in water resource management.

Ultimately, the integration of innovative ICTs into water resource management holds significant promise for advancing sustainable development goals, particularly SDG 6, which aims to ensure access to water and sanitation for all. By embracing these technologies and addressing the challenges outlined in this study, we can move towards a more resilient and equitable water future. Continued research, collaboration, and innovation are essential to fully harness the power of ICT for sustainable water resource management, ensuring the availability of this essential resource for present and future generations.

Author Contributions

The individual author contributions were as follows: Conceptualization, D.M. and O.F.; methodology, D.M. and O.F.; software, D.M and S.C.; validation, O.F., D.C., and C.Q.; formal analysis, O.F. and B.B.; investigation, S.C.; resources, O.F.; data curation, O.F. and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review & editing, D.M.; visualization, B.B.; supervision, O.F.; project administration, O.F.; funding acquisition, O.F. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FAPESP - São Paulo Research Foundation, grant number 2023/10091-5. “The APC was funded by FAPESP”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created.

Acknowledgments

“During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used Gemini (version 2.5 Flash) for translation revision, New Rayyan (version 1.6.1) for systematic reviewing, VOSviewer Online (version 1.6.20) for the purpose of visualizing bibliometric networks, and Zotero (version 5.0.176) for the purposes of collecting, organizing, annotating, citing, and sharing research materials. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACMS |

Automated Continuous Monitoring System |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ANA |

National Water and Basic Sanitation Agency |

| BARCS |

Bacterial Risk Control System |

| BI |

Business Intelligence |

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling |

| DSS |

Decision Support Systems |

| FM |

Facility Management |

| ICT |

Innovative Information and Communication Technologies |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| PERH |

State Water Resources Plans |

| PNRH |

National Water Resources Plan |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| WRPs |

Water Resources Plans |

References

- Chen, X., Zhao, B., Shuai, C., Qu, S., & Xu, M. (2022). Global spread of water scarcity risk through trade. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 187, 106643. [CrossRef]

- Shemer, H., Wald, S., & Semiat, R. (2023). Challenges and solutions for global water scarcity. Membranes, 13(6), 612. [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Law Nº 9.433/1997. Institui a Política Nacional de Recursos Hídricos, cria o Sistema Nacional de Gerenciamento de Recursos Hídricos. Diário Oficial da União, 8 de janeiro de 1997. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9433.htm.

- Johns, C. (2021). Water governance indicators in theory and practice: Applying the OECD’s water governance indicators in the North American Great Lakes region. Water International, 46(7–8), 976–999. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F., Bonriposi, M., Graefe, O., Herweg, K., Homewood, C., Huss, M., Kauzlaric, M., Liniger, H., Rey, E., Reynard, E., Rist, S., Schädler, B., & Weingartner, R. (2014). Assessing the sustainability of water governance systems: The sustainability wheel. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. [CrossRef]

- Lukhabi, D. K., Mensah, P. K., Asare, N. K., Pulumuka-Kamanga, T., & Ouma, K. O. (2023). Adapted water quality indices: Limitations and potential for water quality monitoring in Africa. Water, 15(9), 1736. [CrossRef]

- Rahu, M. A., Shaikh, M. M., Karim, S., Soomro, S. A., Hussain, D., & Ali, S. M. (2024). Water quality monitoring and assessment for efficient water resource management through Internet of Things and Machine Learning approaches for agricultural irrigation. Water Resources Management, 38, 4987–5028. [CrossRef]

- Kamyab, H., Khademi, T., Chelliapan, S., SaberiKamarposhti, M., Rezania, S., Yusuf, M., Farajnezhad, M., Abbas, M., Jeon, B. H., & Ahn, Y. (2023). The latest innovative avenues for the utilization of artificial intelligence and big data analytics in water resource management. Results in Engineering, 20, 101566. [CrossRef]

- Alfwzan, W. F., Selim, M. M., Almalki, A. S., & Alharbi, I. S. (2024). Water quality assessment using Bi-LSTM and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) techniques. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 97, 346–359. [CrossRef]

- Negri, R.G.; Mendes, J.E.A. Sensoriamento remoto da qualidade da água: princípios e aplicações. Revista Brasileira de Cartografia 2020, 72, 1185–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; et al. A vision of IoT: Applications, challenges, and opportunities with China perspectives. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2013, 1, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, B.B.; Barcellos, C.; Pedroso, A.C. Ciência de dados para saúde: um panorama introdutório. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2021, 37, e00315120. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, L.C.; Machado, J.A. Mineração de dados: conceitos, métodos e aplicações. São Paulo: Érica, Brazil, 2008.

- MARIBEL, M.; RAMOS, I. Business intelligence: Uma abordagem conceitual. Revista de Administração de Empresas 2006, 46, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sichman, J.S. Inteligência artificial: o que é, para que serve, onde se aplica. São Paulo: Blucher, Brazil, 2021.

- Ludemir, T.B. Aprendizado de máquina: fundamentos e aplicações. Rio de Janeiro: LTC, Brazil, 2021.

- Paixão, L.F. Machine learning: guia prático com Python. São Paulo: Novatec, Brazil, 2022.

- Ferneda, E. Redes neurais artificiais: fundamentos e aplicações. São Paulo: Atlas, Brazil, 2006.

- Souza, W.M.; Gomes, H.M.; Barroso, R.C.; Miranda, R.M.; Gurgel-Gonçalves, R. Deep learning para classificação de imagens: uma revisão bibliográfica. Revista Brasileira de Computação Aplicada 2020, 12, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Clericuzi, E.; Almeida, F.A.; Costa, S.M. Sistemas de apoio à decisão: conceitos e aplicações. São Paulo: Atlas, Brazil, 2006.

- Sausen, J.M. Machine vision para a indústria 4.0. São Paulo: SENAI, Brazil, 2020.

- Botega, L.C.; Cruvinel, P.E. Realidade virtual e realidade aumentada na agricultura de precisão. Engenharia Agrícola 2009, 29, 864–877. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and conducting mixed methods of research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, USA, 2015.

- Vanti, N. A. Da bibliometria à webometria: uma exploração conceitual dos mecanismos utilizados para medir o registro da informação e a difusão do conhecimento. Ciência da Informação 2002, 31, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo-Silva, F.; et al. Bibliometria e análise de redes sociais em periódicos científicos da área de administração: um estudo comparativo. Revista de Administração da UFSM 2016, 9, 470–491. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, E.G.; et al. Mapeamento da produção científica sobre gestão do conhecimento na área de administração: uma análise bibliométrica. Revista de Administração da UFSM 2010, 3, 224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Fidelis, M.V.; et al. Produção científica brasileira sobre gestão ambiental: uma análise bibliométrica da produção científica. Revista de Administração da UFSM 2009, 2, 242–258. [Google Scholar]

- PRICE, D.J. De S. A general theory of bibliometric and other cumulative advantage processes. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 1976, 27, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbizagastegui, R. Análise bibliométrica da produção científica sobre bibliotecas digitais. Ciência da Informação 2008, 37, 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, R.U. A bibliometric analysis of the literature on corporate social responsibility: a review of two decades of research. Intangible Capital 2016, 12, 479–521. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas, P.; Papanicolaou, G. Zipf’s law for word frequencies in natural language: A critical review. Journal of Informetrics 2020, 14, 101096. [Google Scholar]

- Waltman, L.; Van Eck, N.J. A smart local moving algorithm for large-scale modularity-based network optimization. European Physical Journal B 2013, 86, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and new paradigms in science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousha, K.; Thelwall, M. Google Scholar citations and Web of Science: a comparative analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 2007, 58, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, T.F.; et al. Elaboração de revisão sistemática da literatura. Brasília Med 2015, 52, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 1–10.

- Raghul, S.; Porchelvan, P. Water quality assessment using remote sensing and machine learning techniques. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2024, 196, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, T.; et al. Estimation of suspended solids and nitrogen-phosphorus ratio in Lake Biwa using satellite remote sensing. Limnology 2022, 23, 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, T.O.; et al. Detection of turbidity anomalies in a tropical reservoir using remote sensing and machine learning. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2023, 31, 100999. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; et al. Estimating chlorophyll-a, total phosphorus, and total nitrogen concentrations in Lake Simcoe using remote sensing and deep learning. Remote Sensing of Environment 2021, 264, 112625. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P.T.; et al. Groundwater potential mapping using remote sensing data and deep neural networks: A case study in the North and Central Vietnam. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 906, 167640. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A.; et al. Modelling and mapping spatial variability of urban groundwater resources integrating remote sensing data, machine learning algorithms and hydrogeological dynamics. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; et al. A framework for automated detection of river barriers using satellite imagery. Nature Sustainability 2024, 7, 620–631. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abadi, A.M.; et al. Drought susceptibility mapping using GRACE/GRACE-FO and GLDAS data with machine learning algorithms: A case study in Iraq. Advances in Space Research 2024, 73, 1151–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Reljić, D.; et al. Application of Automated Continuous Monitoring System for the Assessment of Environmental Parameters in the Neretva River Delta. Water 2023, 15, 3874. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; et al. Pilot study of a water quality management system by combining in situ sensors and model for urban rivers. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 419, 138285. [Google Scholar]

- Batista. L., T.; et al. BIM-IoT-FM integration: strategy for implementation of sustainable water management in buildings. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment 2023, 13, 1096–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.; Saynisch-Wagner, J.; Schulz, S. Global scale groundwater recharge data-driven modelling and interpretation. Hydrological Processes 2024, 38, e14992. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, S.; et al. Mapping groundwater potential zones in climate variability scenarios using machine learning approaches. Sustainable Water Resources Management 2024, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; et al. Gully erosion susceptibility mapping using hybrid machine learning models: A case study in the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2022, 218, 106541. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; et al. Predicting Bacterial Risk in Urban Water Distribution Systems Using Machine Learning and Sensors. Environmental Science & Technology 2023, 57, 16576–16586. [Google Scholar]

- Benhmad, F.; et al. Smart irrigation system using Internet of Things and artificial intelligence for efficiency water resource management in Tunisian oases. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 216, 108530. [Google Scholar]

- Petri, E.; et al. An intelligent support system for real-time management of hydrographic basins and water resources. Environmental Modelling & Software 2018, 109, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).