Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

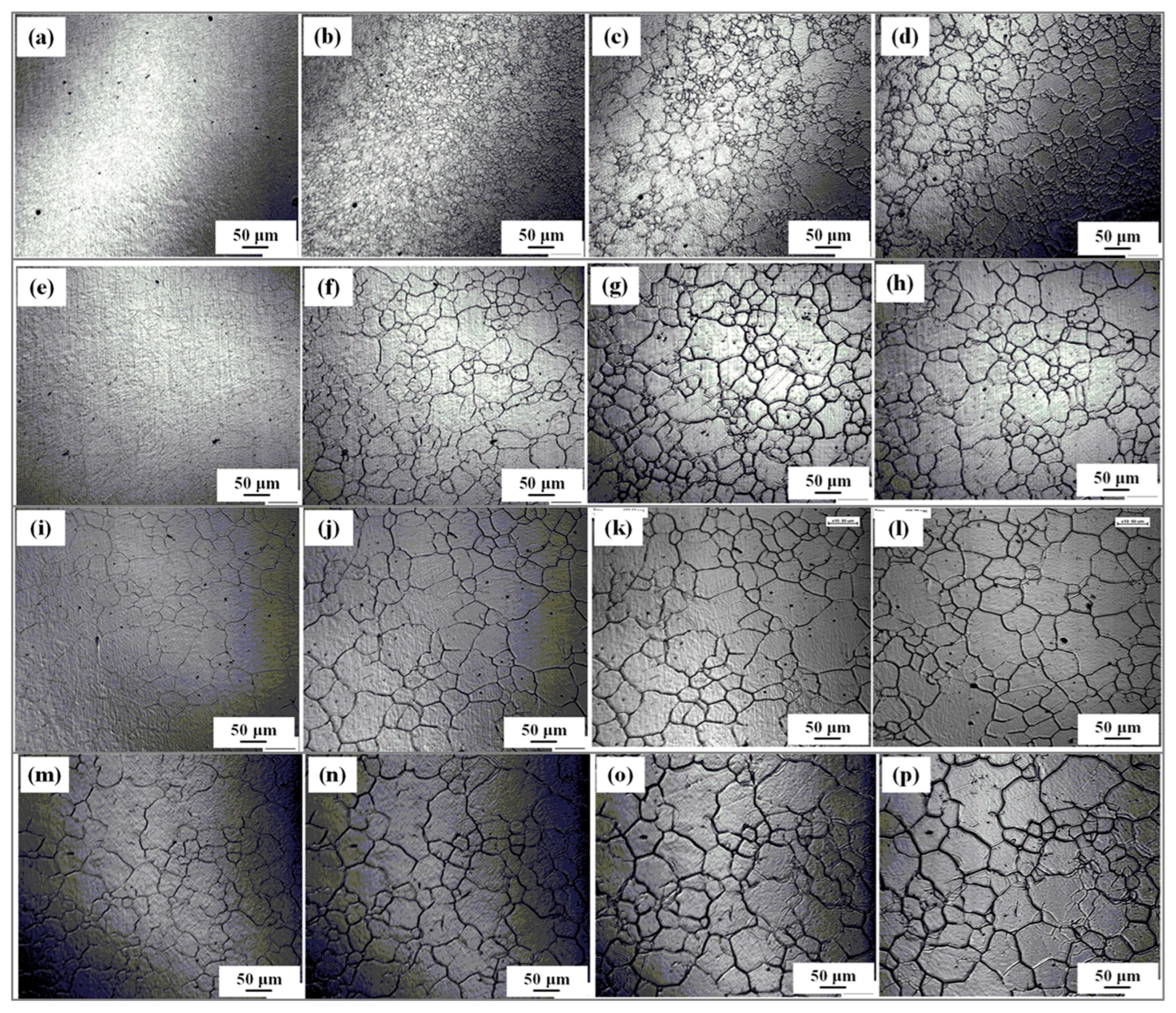

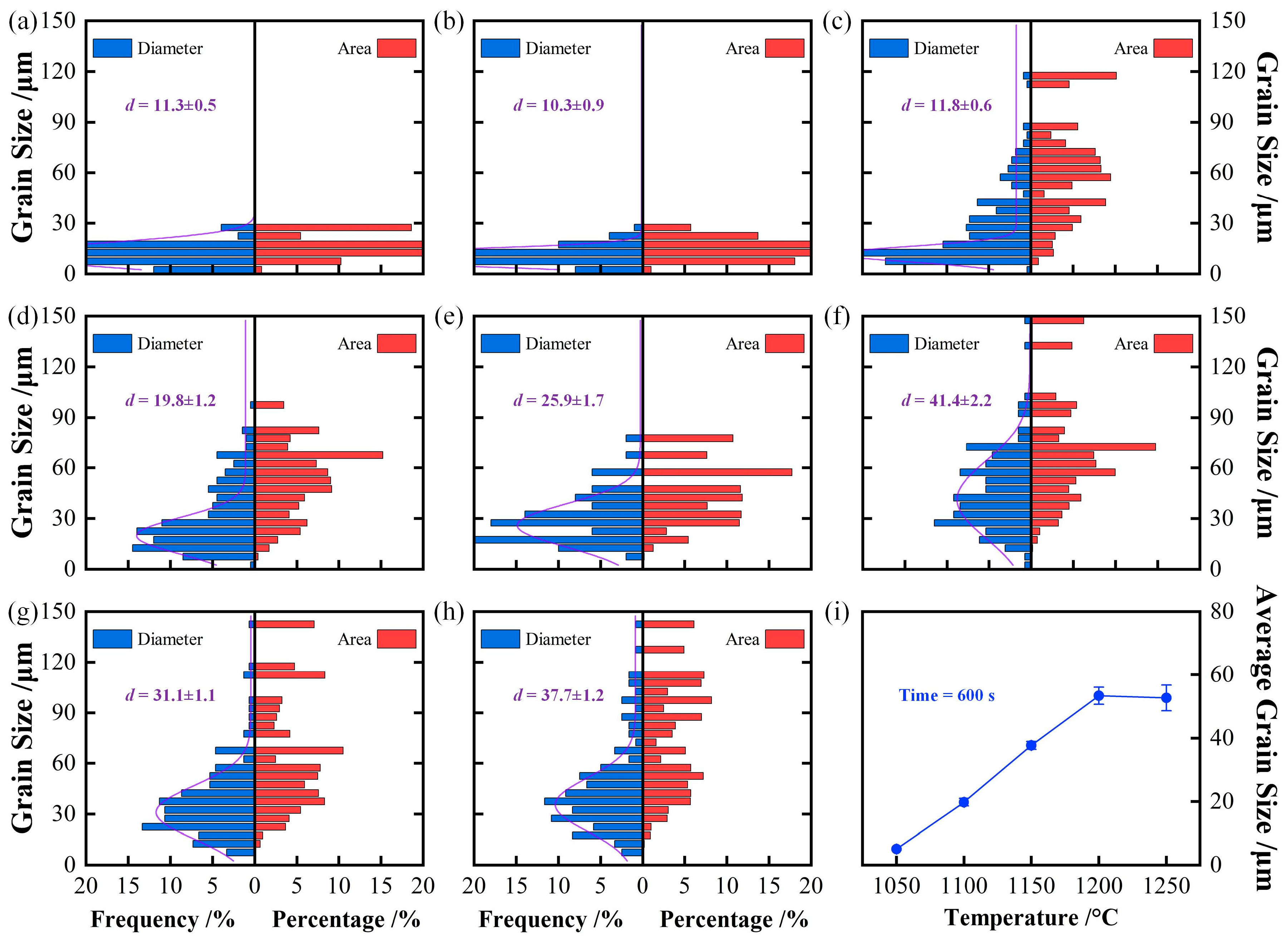

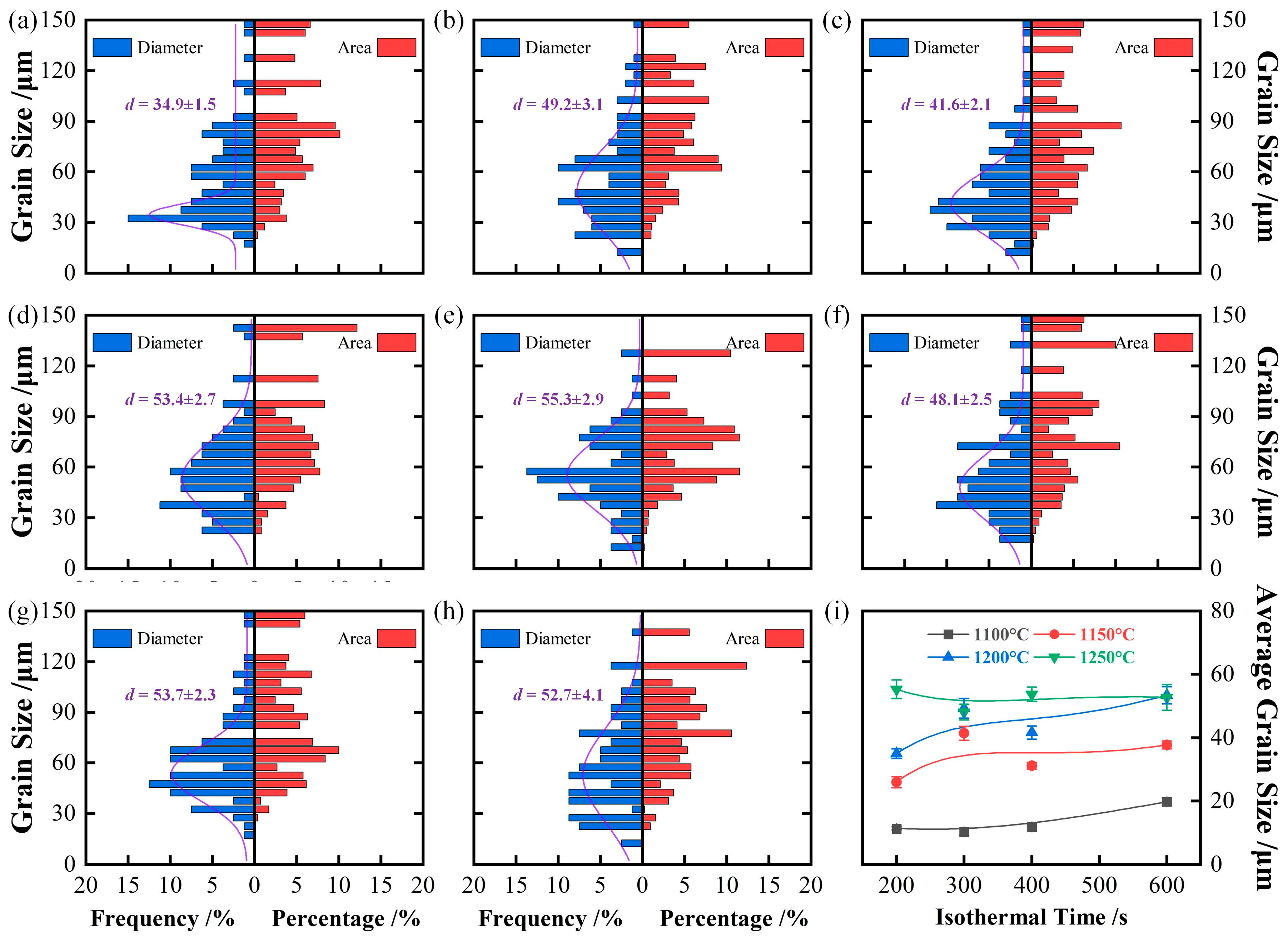

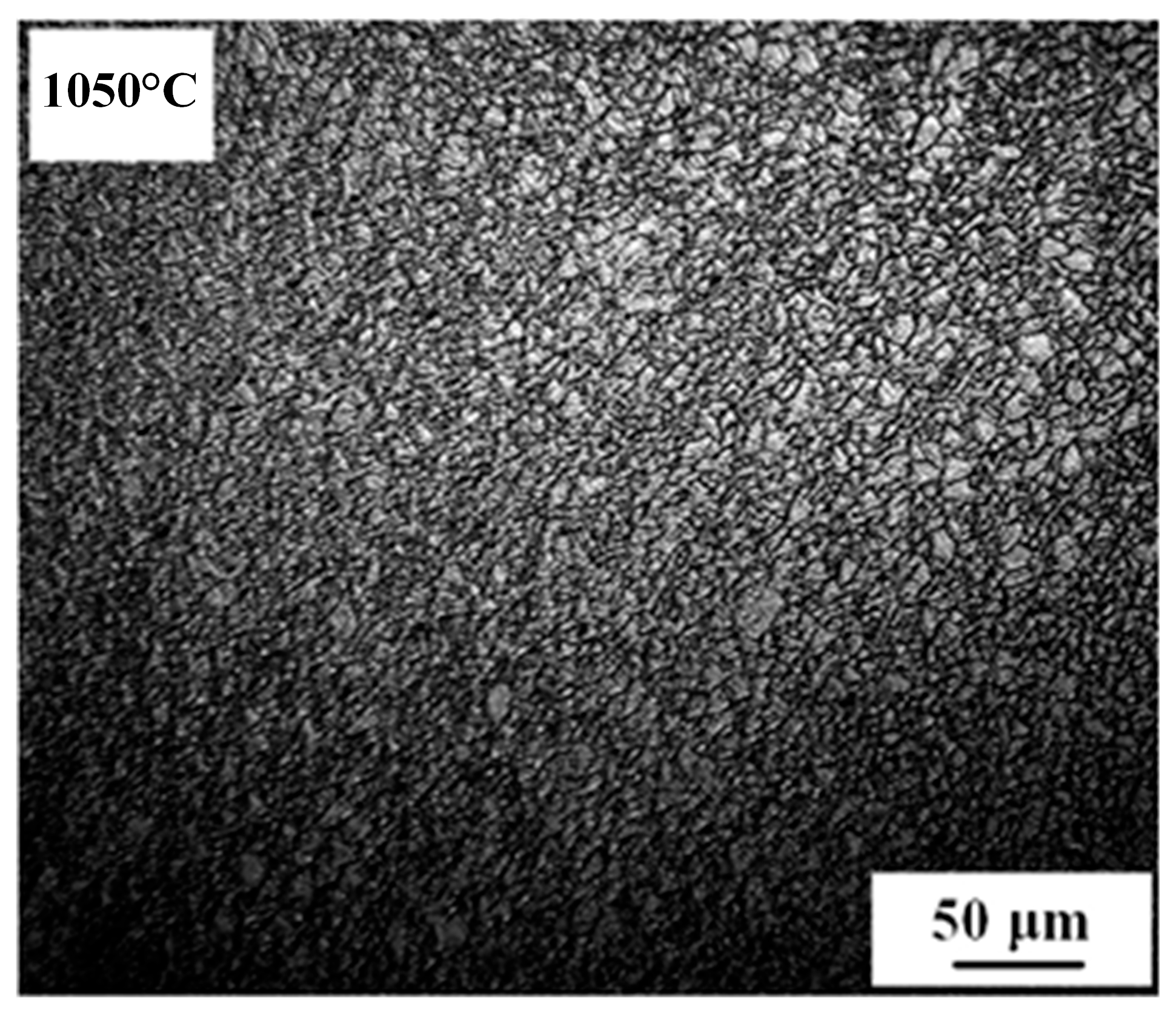

In this paper, the austenite grains growth behavior in the austenitizing process of Nb-Ti micro-alloyed medium manganese steel was studied through in-situ observation by high temperature laser confocal microscope. The results show that the average austenite grain sizes change from about 3 μm at 1050℃ to over 50 μm at 1250℃. When the grain boundary is a small angle grain boundary, one grain boundary will split into several dislocations. With the extension of heating time, the lattice orientation difference further decreases, and the remaining dislocations may merge into new grain boundaries. The most suitable heating temperature for the medium manganese steel in this paper is from 1100℃ to 1150℃. This takes into account influences such as grain size, grain boundary damage, and deformation resistance.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Growth Behavior of Austenite Grains During Heating Process

3.2. Thermodynamics Calculation of Phase Zones and Carbides Average Diameter

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Isothermal Temperature on Austenite Grain Growth Behavior

4.2. Austenite Grain Growth Mechanism During Isothermal

4.3. Consideration of Heating Process for Medium Manganese Steel Continuous Casting Billet

5. Conclusions

- (1).

- The average austenite grain sizes of the specimen isothermal at 1050℃, 1100℃, 1150℃, 1200℃, and 1250℃ for 600 s are 3.2, 19.8, 37.7, 53.4, and 52.7 μm, respectively. The average austenite grain sizes change from about 3 μm at 1050℃ to over 50 μm at 1250.

- (2).

- When the grain boundary is a small angle grain boundary, one grain boundary will split into several dislocations. With the extension of heating time, the lattice orientation difference further decreases, and the remaining dislocations may merge into new grain boundaries. When the grain boundary is a large angle grain boundary, only grain boundary movement can occur.

- (3).

- The weight fraction of precipitates below 1000°C is about 0.065% and precipitate reduce to disappear from about 1000°C to 1200°C. A portion of the precipitates nucleate and grow during the heating and holding stage at a holding temperature of 1050~1150°C, and the precipitates dissolve completely during heating when the holding temperature exceeds 1200°C.

- (4).

- The most suitable heating temperature for the medium manganese steel in this paper is from 1100℃ to 1150℃. This takes into account influences such as grain size, grain boundary damage, and deformation resistance.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- J.P. Liu, S. Zhao, S.N. Ma, C. Chen, H.H. Ding, R.M. Ren, Research on the dynamic recrystallization mechanism of high manganese steel under severe wear conditions, Wear Pre-proof. [CrossRef]

- Z.H. Cai, H. Ding, R.D.K. Misra, Z.Y. Ying, Austenite stability and deformation behavior in a cold-rolled transformation-induced plasticity steel with medium manganese content, Acta Mater. 84 (2015) 229-236. [CrossRef]

- J. Hu, X.Y. Li, Q.W. Meng, L.Y. Wang, Y.Z. Li, W. Xu, Tailoring retained austenite and mechanical property improvement in Al-Si-V containing medium Mn steel via direct intercritical rolling Mater. Sci. Eng. A 855 (2022) 143904. [CrossRef]

- S. Wolke, M. Smaga, T. Beck, Influence of surface morphologies and defects on the high cycle fatigue life of high manganese TWIP steel, Int. J. Fatigue 200 (2025) 109089. [CrossRef]

- J.H. Chu, Z.Y. Cheng, P.J. Dou, X. Pan, Z.M. Wang, Y.Y. Li, N. Tao, Q. Yue, L.Z. Chang, Corrosion behaviour of magnesia-carbon refractories by high manganese steel melts, Corros. Sci. 246 (2025) 112753. [CrossRef]

- M. Soleimani, A. Kalhor, H. Mirzadeh, Transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) in advanced steels: a review, Mater. Sci. Eng., A 795 (2020), 140023. [CrossRef]

- F.J. Cai, H.S. Wang, Y. Wang, Y. Kong, R.Q. Fan, F.K. Yan, Enhanced stability of retained austenite to facilitate deformation compatibility of surrounding ferrite in a medium manganese steel, J. Mater. Res. Technol. 36 (2025) 3425-3435. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dong, B. Zhang, M.M. Zhao, Y. Du, R.D.K. Misra, L.X. Du, Investigation of austenite decomposition behavior and relationship to mechanical properties in continuously cooled medium-Mn steel, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 831 (2022) 142208. [CrossRef]

- X.Y. Qi, L.X. Du, J. Hu. R.D.K. Misra, High-cycle fatigue behavior of low-C medium-Mn high strength steel with austenite-martensite submicro-sized lath-like structure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 718 (2018) 471-482. [CrossRef]

- Y. Du, X.H. Gao, L.Y. Lan, X.Y. Qi, H.Y. Wu, L.X. Du, R.D.K. Misra, Hydrogen embrittlement behavior of high strength low carbon medium manganese steel under different heat treatments, Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 44 (2019) 32292-32306. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, L.X. Du, J. Hu, H.Y. Wu, X.H. Gao, R.D.K. Misra, Interplay between reversed austenite and plastic deformation in a directly quenched and intercritically annealed 0.04C-5Mn low-Al steel, J. Alloy Compd. 695 (2017) 2072-2082. [CrossRef]

- Z.H. Liao, Y. Dong, Y. Du, X.N. Wang, M. Qi, H.Y. Wu, X.H. Gao, L.X. Gao, Effects of different intercritical annealing processes on microstructure and cryogenic toughness of newly designed medium-Mn and low-Ni steel, J. Mater. Res. Technol. 23 (2023) 1471-1486. [CrossRef]

- B.H. Sun, D. Palanisamy, D. Ponge, B. Gault, F. Fazeli, C. Scott, S. Yue, D. Raabe, Revealing fracture mechanisms of medium manganese steels with and without delta-ferrite, Acta Mater. 164 (2019) 683–696. [CrossRef]

- S. Yu, L.X. Du, J. Hu, et al. Effect of hot rolling temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of ultra-low carbon medium manganese steel, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 731 (2018) 149-155. [CrossRef]

- R.T. van Tol, L. Zhao, J. Sietsma, Kinetics of austenite decomposition in manganese-based steel, Acta Mater. 64 (2014) 33-40. [CrossRef]

- H.L. Hu, M.J. Zhao, L.J. Rong, Retarding the precipitation of η phase in Fe-Ni based alloy through grain boundary engineering, J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 47 (2020) 152-161. [CrossRef]

- M. Baram, D. Chatain, W.D. Kaplan, Nanometer-thick equilibrium films: the interface between thermodynamics and atomistics, Science 332 (2011) 206–209. [CrossRef]

- P.C. Kokkula, S. Samanta, S. Mandal, S.B. Singh, Kinetics of pearlite transformation: The effect of grain boundary engineering, Acta Mater. 284 (2025) 120641. [CrossRef]

- P. Lejcek, M. Sob, V. Paidar, Interfacial segregation and grain boundary embrittlement: an overview and critical assessment of experimental data and calculated results, Prog. Mater. Sci. 87 (2017) 83e139. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, R. Janisch, G.K.H. Madsen, R. Drauz, First-principles study of carbon segregation in bcc iron symmetrical tilt grain boundaries, Acta Mater. 115 (2016) 259e268. [CrossRef]

- L. Huber, B. Grabowski, M. Militzer, J. Neugebauer, J. Rottler, Ab-initio modelling of solute segregation energies to a general grain boundary, Acta Mater. 132 (2017) 138e148. [CrossRef]

- G.S. Rohrer, The role of grain boundary energy in grain boundary complexion transitions, Curr. Opin. Solid St. M. 20 (2016) 231–239. [CrossRef]

- P. Lejček, S. Hofmann, Modeling grain boundary segregation by prediction of all the necessary parameters, Acta Mater. 170 (2019) 253-267. [CrossRef]

- J.E. Burke, D. Turnbull, Recrystallization and grain growth, London, Progress in Metal Physics Pergamon Press, 3 (1952) 220-224.

- K.T. Aust, J.W. Rutter, Grain boundary migration in high purity lead and lead–tin alloys. Trans. Metall. Soc. AIME, 215 (1959) 119-127.

- K. Lücke, H.P. Stüwe, On the theory of impurity controlled grain boundary motion. Acta Mater. 19 (1971) 1087-1099. [CrossRef]

- D. McLean, Grain boundaries in metals, Oxford University Press, (1957) 116-149.

- T. Nishizawa, Thermodynamics of microstructures, ASM International, (2008) 157-159.

- C. Zener, C. Smith, Grains, Phases and Interfaces: Interpretation of Microstructures. Transaction metallurgy Society of AIME, 175 (1948), 15-51.

- Y. Dong, L.Y. Xiang, C.J. Zhu, Y. Du, Y. Xiong, X.Y. Zhang, L.X. Du, Analysis of phase transformation thermodynamics and kinetics and its relationship to structure-mechanical properties in a medium-Mn high strength steel, J. Mater. Res. Technol. 27 (2023) 5411-5423. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dong, M. Qi, Y. Du, H.Y. Wu, X.H. Gao, L.X. Du, Significance of retained austenite stability on yield point elongation phenomenon in a hot-rolled and intercritically annealed medium-Mn steel, Steel Res. Int. 93 (2022) 2200400. [CrossRef]

- D.P. Yang, D.Wu, H.L.Yi, Reverse transformation from martensite into austenite in a medium-Mn steel, Scr. Mater. 161 (2019) 1-5.

- F. Moszner, E. Povoden-Karadeniz, S. Pogatscher, P.J. Uggowitzer, Y. Estrin, S.S.A. Gerstl, E. Kozeschnik, J.F. Lo¨ffler, Reverse α’→γ transformation mechanisms of martensitic Fe–Mn and age-hardenable Fe–Mn–Pd alloys upon fast and slow continuous heating, Acta Mater. 72 (2014) 99–109.

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Nb | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.08 | 0.25 | 4.52 | 0.011 | 0.0019 | 0.018 | 0.036 |

| 200 s | 300 s | 400 s | 600 s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1100°C | 11.3±0.5 | 10.3±0.9 | 11.8±0.6 | 19.8±1.2 |

| 1150°C | 25.9±1.7 | 41.4±2.2 | 31.1±1.1 | 37.7±1.2 |

| 1200°C | 34.9±1.5 | 49.2±3.1 | 41.6±2.1 | 53.4±2.7 |

| 1250°C | 55.3±2.9 | 48.1±2.5 | 53.7±2.3 | 52.7±4.1 |

| 200 s | 300 s | 400 s | 600 s | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter Frequency |

Area Percentage |

Diameter Frequency |

Area Percentage |

Diameter Frequency |

Area Percentage |

Diameter Frequency |

Area Percentage |

|

| 1100°C | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 22.6 | 2.0 | 11.0 |

| 1150°C | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.9 | 28.0 | 5.3 | 31.1 | 13.3 | 49.7 |

| 1200°C | 21.3 | 53.7 | 19.0 | 51.1 | 16.0 | 49.3 | 17.5 | 46.5 |

| 1250°C | 17.5 | 41.1 | 20.0 | 53.5 | 22.5 | 53.3 | 21.3 | 51.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).