Submitted:

29 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Compensate for the absence of a useful mathematical model for describing a generalized finite-strain consolidation process. It advances the simulation of the finite-strain consolidation process of soft or very soft clay layers. Compared to traditional small-strain consolidation theories (e.g., [4]), the proposed mathematical model has more applications, such as estimating settlements of dredge fill deposits.

- Extend the application of the DGM to a partial differential equation with a problem domain subjected to large strains.

2. Related Works

2.1. Finite Strain Consolidation Theory

2.2. Deep Galerkin Method

3. Generalized Finite Strain Consolidation

3.1. Mathematical Model

3.1.1. Mass Balance for the Clay Grain Phase

3.1.2. Mass Balance for the Pore Water Phase

3.1.3. Momentum Balance for the Clay Grain Phase

3.1.4. Momentum Balance for the Pore Water Phase

3.2. DGM Formulation

| Algorithm 1 DGM algorithm |

|

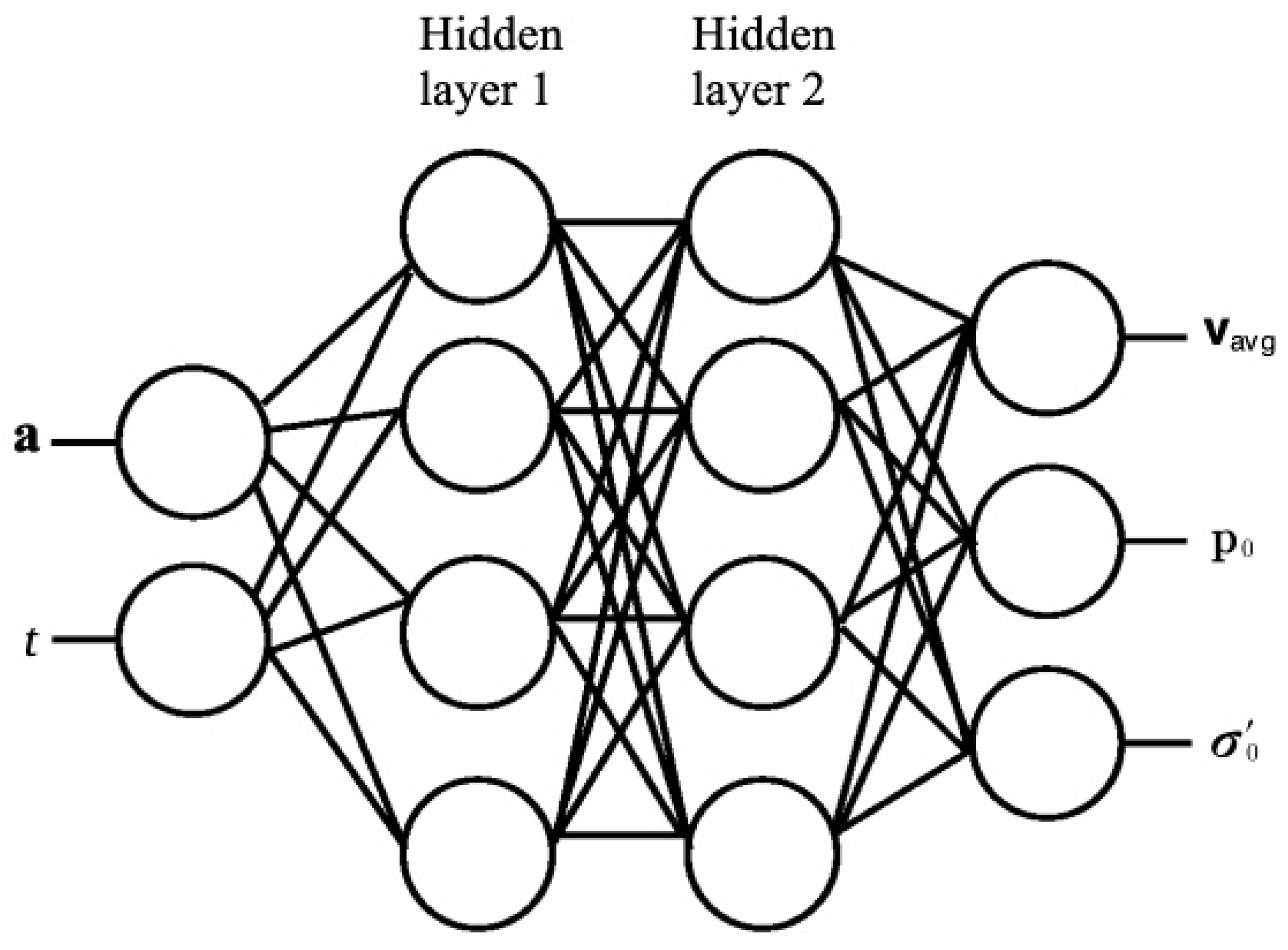

- Input layer: The neural network calculates:in which , is the intermediate hidden feature vector, represents the activation function, denotes the input weight matrix, and represents the input bias vector.

- Hidden layer: Suppose L hidden layers are generated. For each hidden layer, the neural network computes:where denotes the L-th hidden layer, is the gate vector, the subscripts f, r, and h denote the update gate, reset gate, and candidate hidden gate; respectively, represents the reset gate. represents the candidate hidden state, ⊙ is the Hadamard product, and tanh is the hyperbolic tangent function. This tanh function serves as a nonlinear activation function.

- Output layer:where represents the output of the neural network, is the weight matrix of the output layer, and is the bias vector of the output layer.

3.3. Implementation of the DGM

4. Application

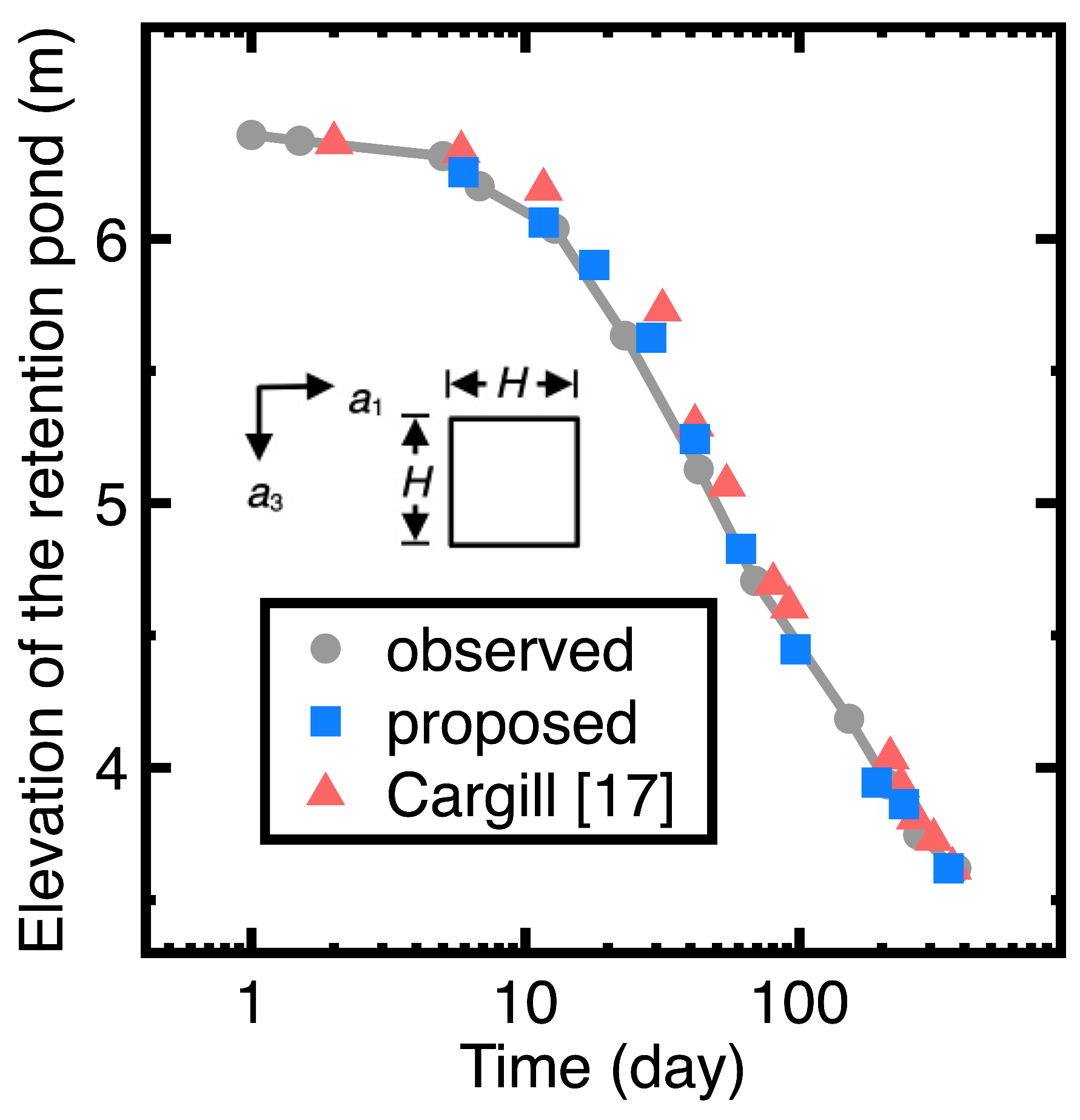

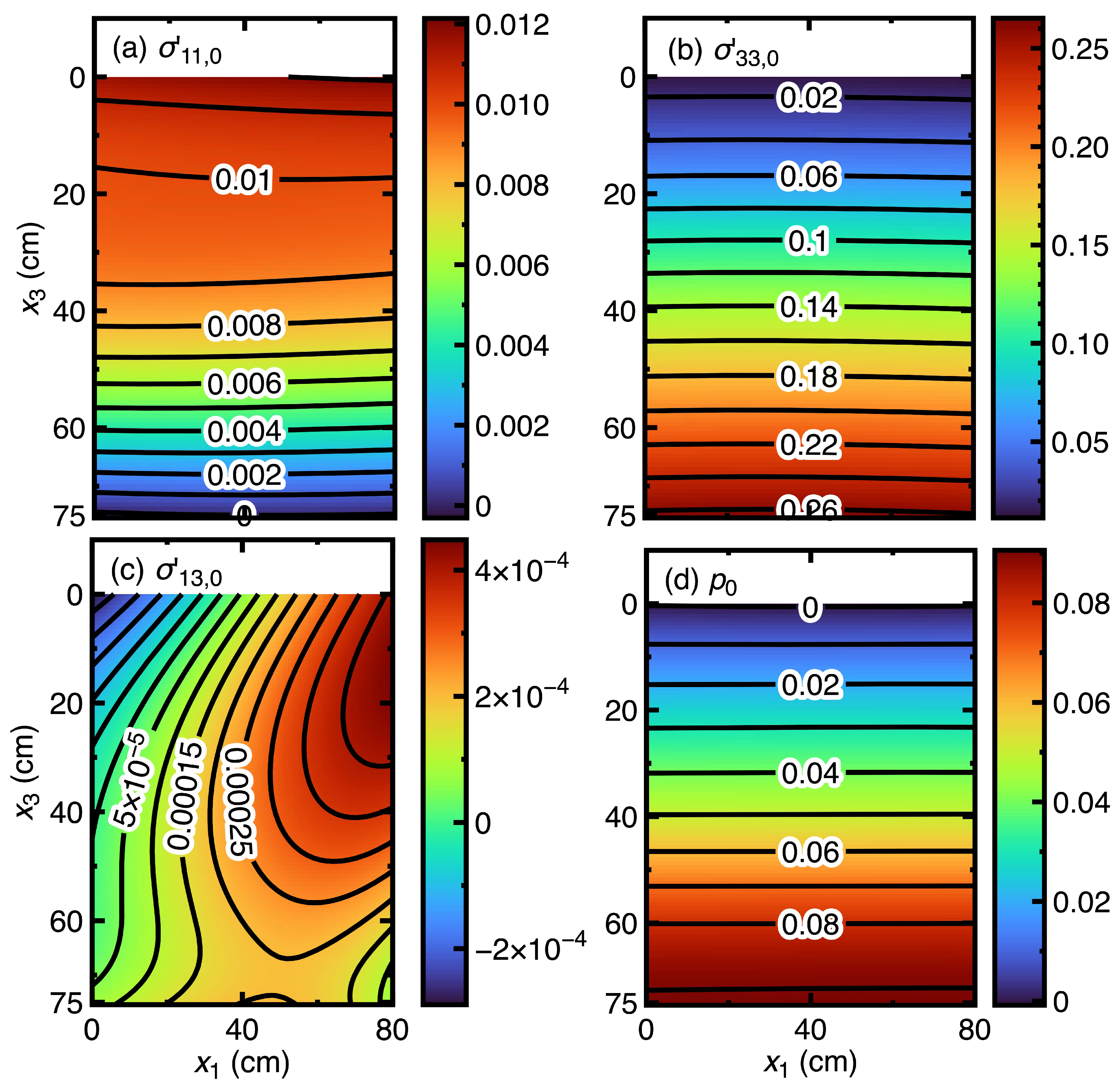

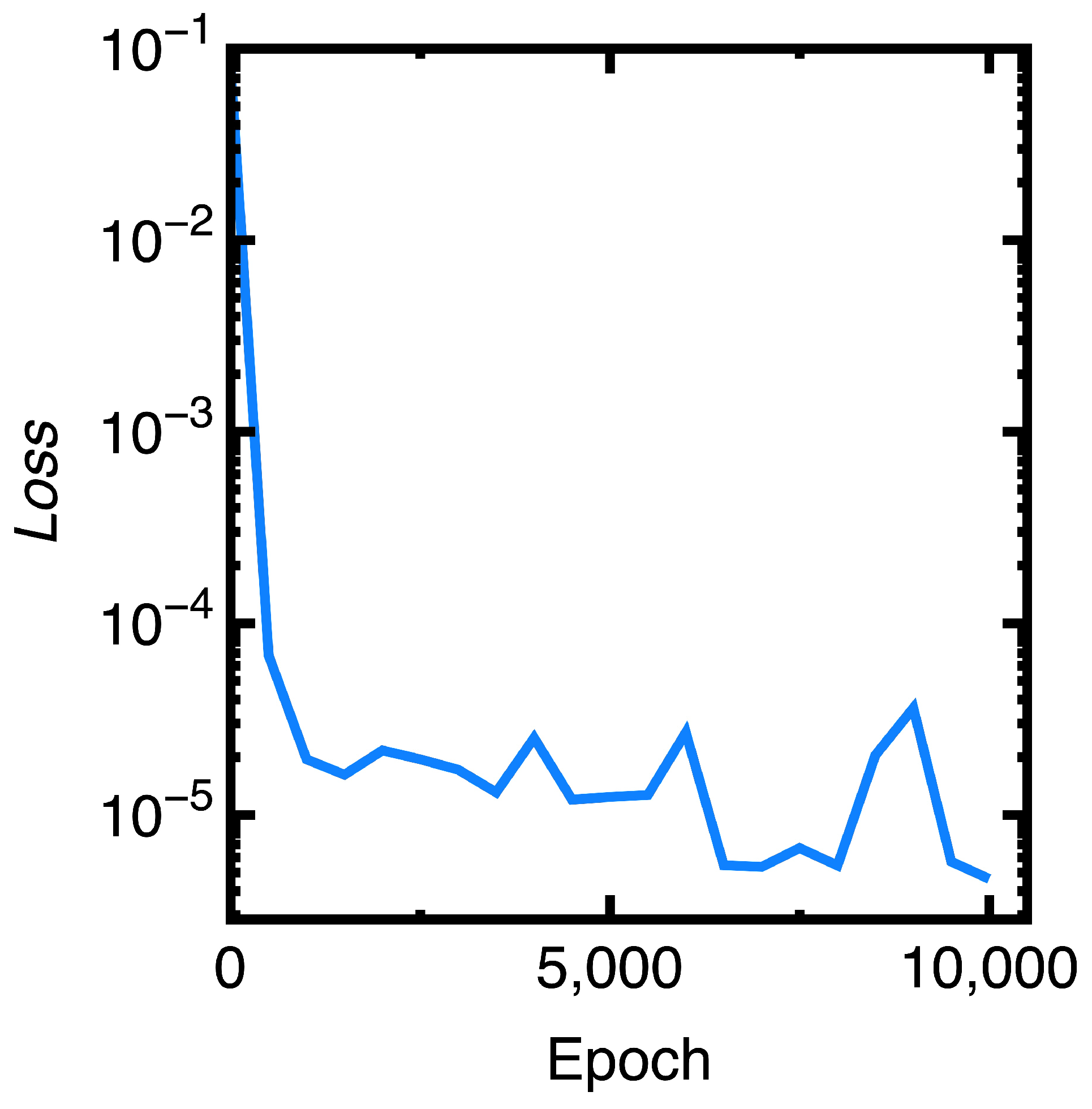

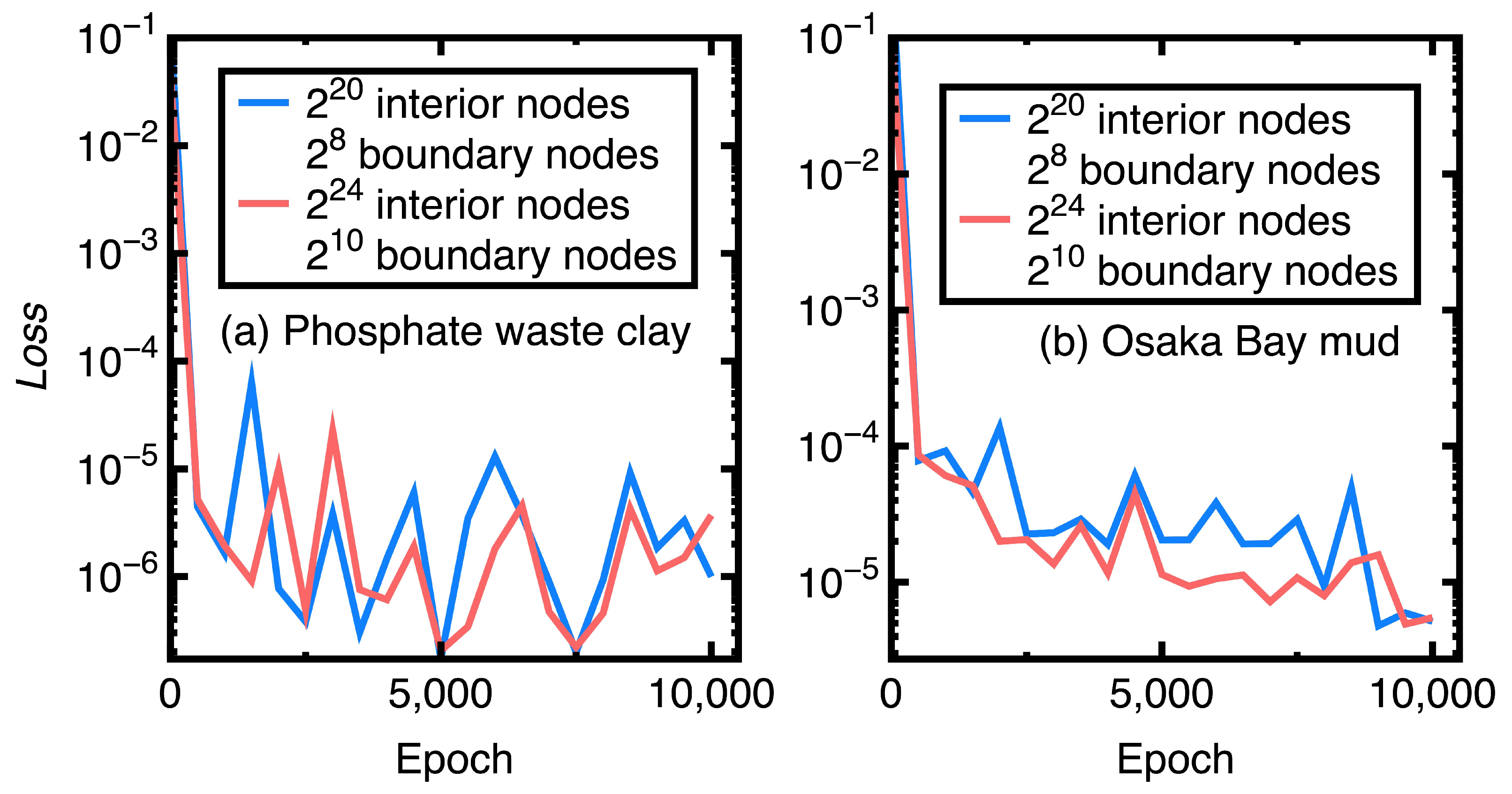

4.1. Phosphatic Waste Clay

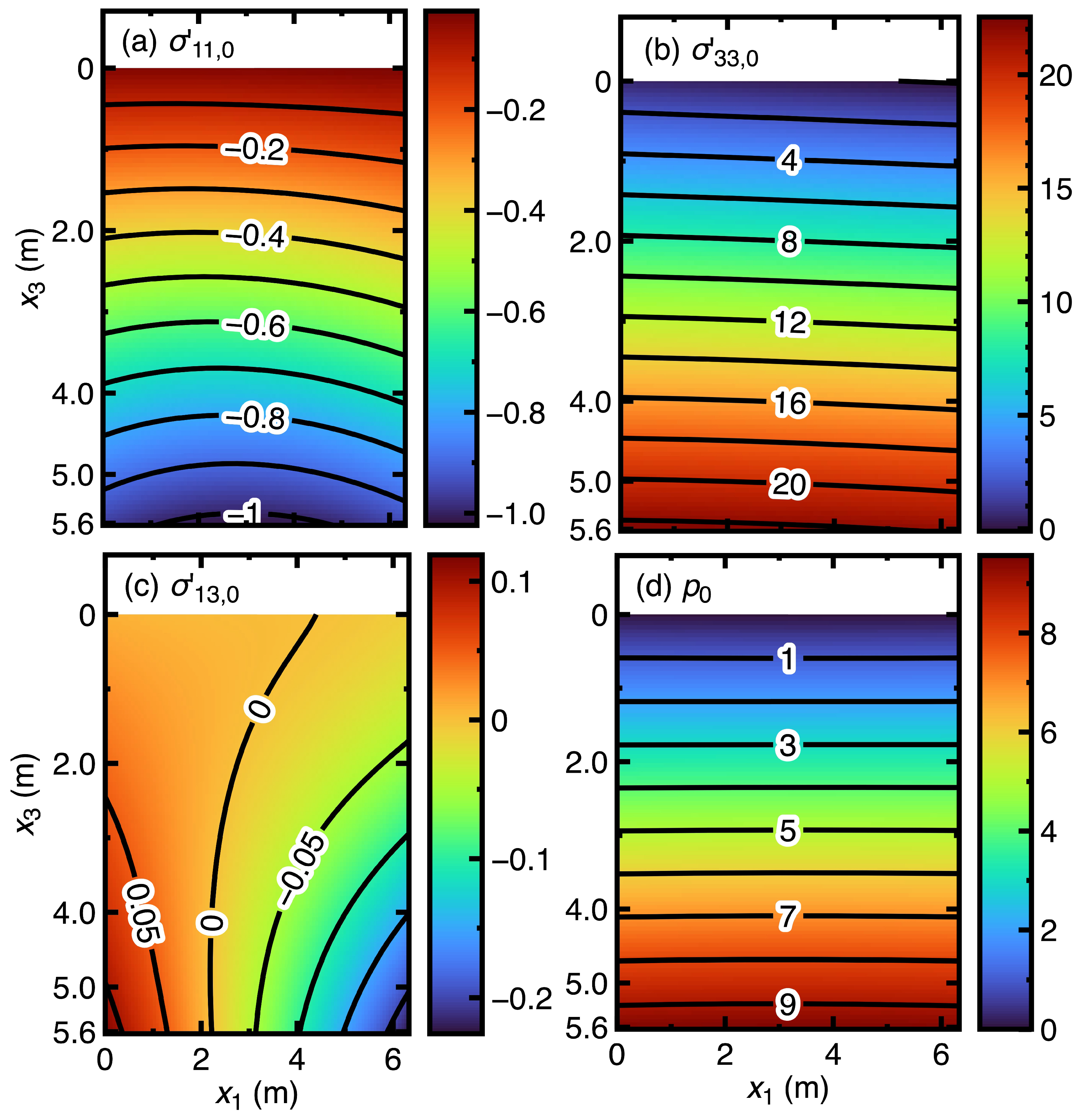

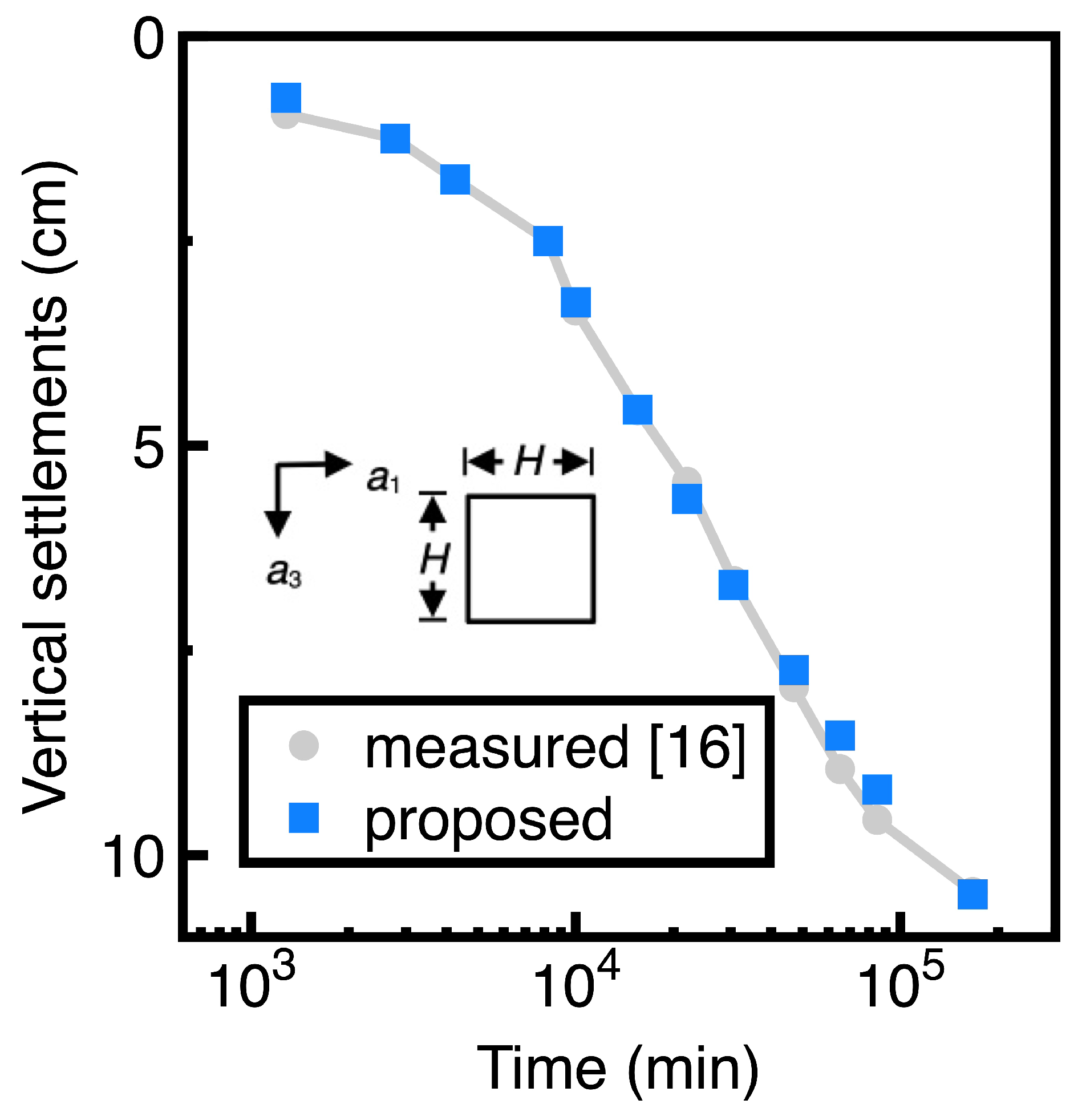

4.2. Osaka Bay Mud

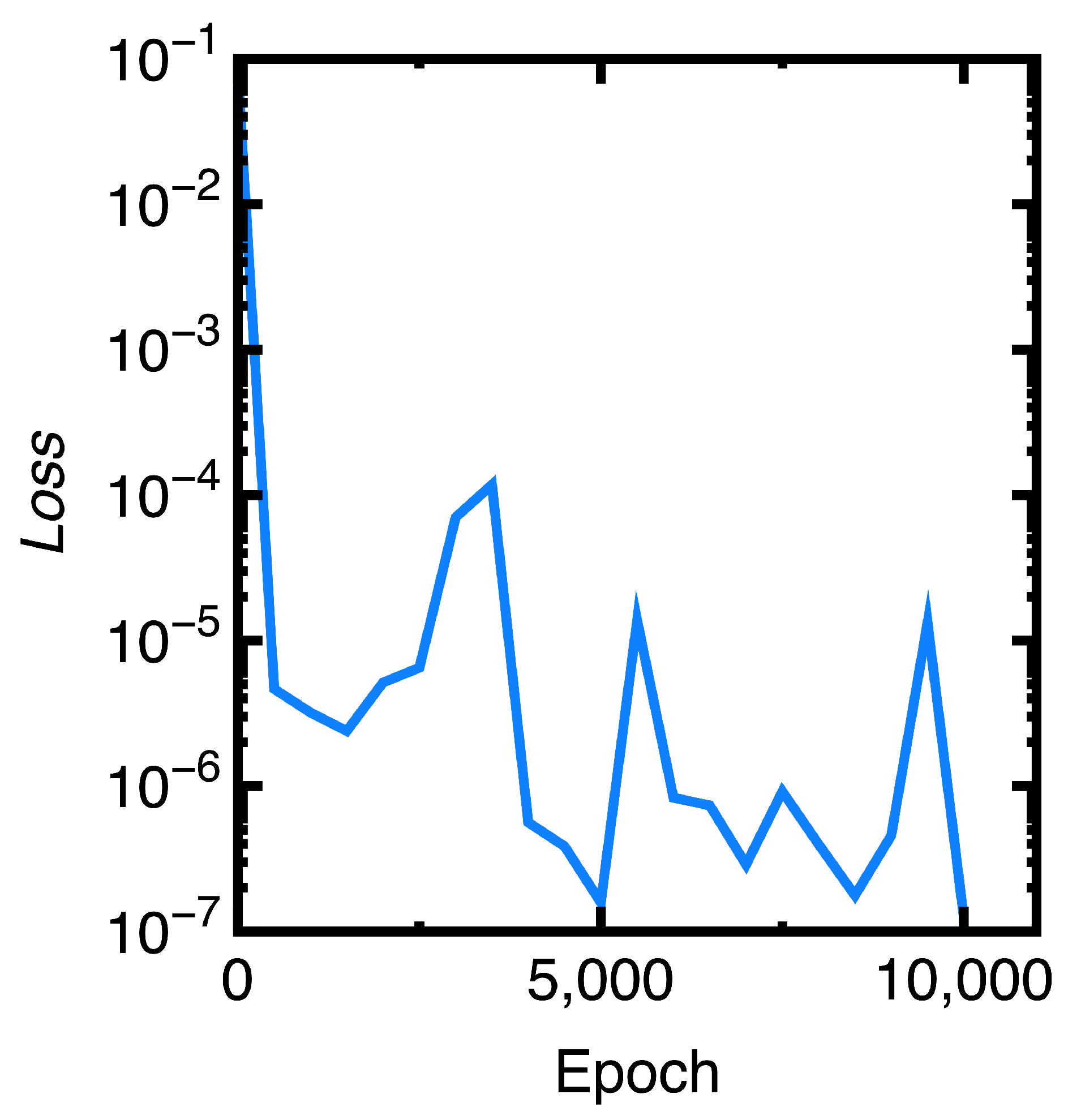

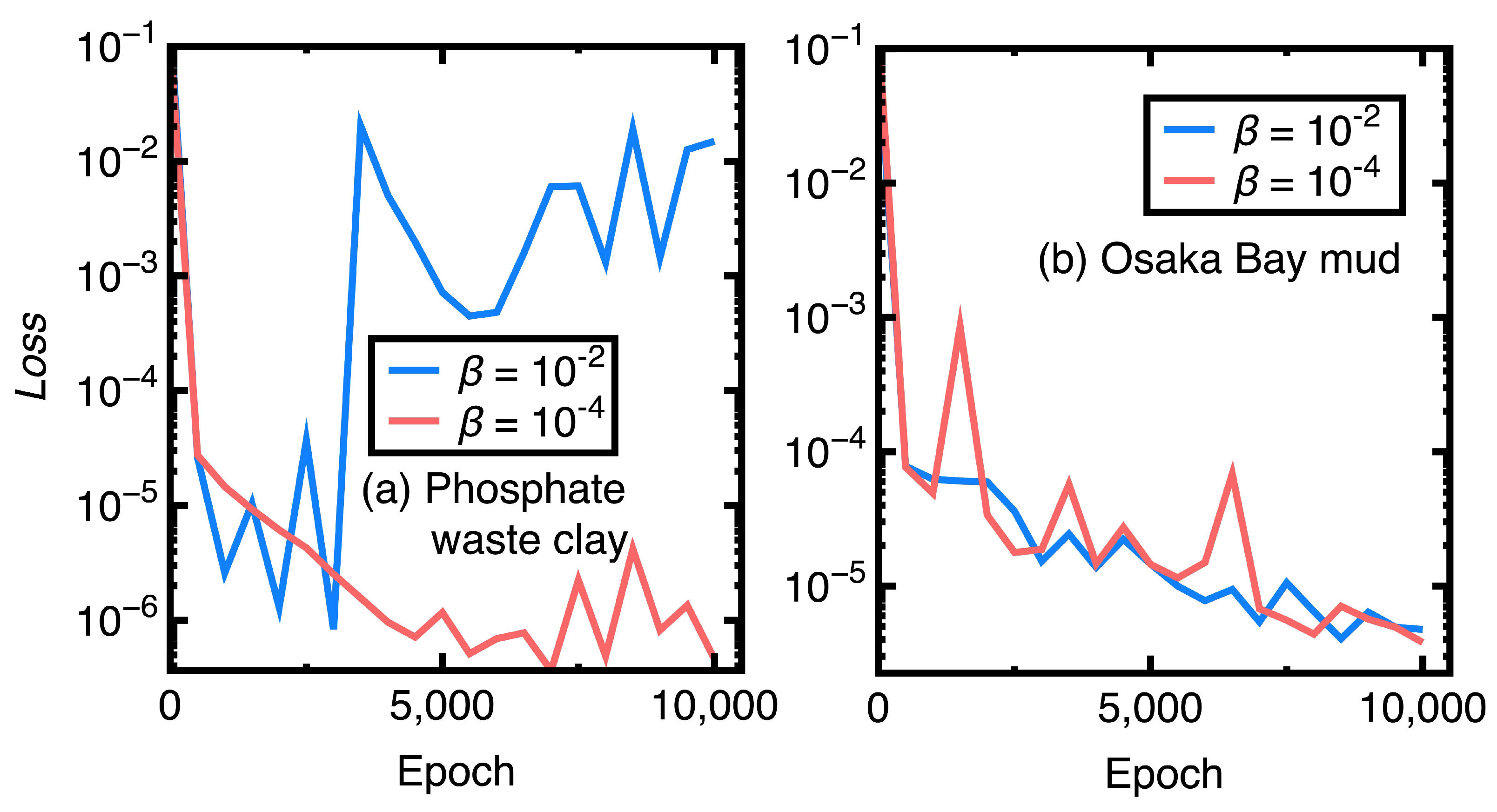

4.3. Ablation Study

5. Discussion

- The first difficulty is the challenge of balancing the number of assumptions and the simplicity of the corresponding governing equations. This study eliminates the assumption that a clay layer consolidates only in the vertical direction in modeling a finite strain consolidation process; however, the current governing equation (Equation (29)) is not complex.

- The second difficulty is the harassment of choosing a suitable numerical method for solving a real-world problem. For this study, it is difficult to define some boundary conditions of a natural soft clay layer; nevertheless, boundary conditions are prerequisites for implementing existing numerical methods (for example, the finite element method). Section 4.1 provides an example. Probably due to the lack of field measurements, some boundary conditions were unavailable in the previous study [17]. However, the DGM can resolve this difficulty since its goal is to minimize the value at random nodes.

- The third difficulty is the requirement that the total number of governing equations equals the total number of unknowns. The DGM helps eliminate this requirement. In Section 4.1 and Section 4.2, two governing equations are available, but six unknowns (pore water pressure, two average velocity components, and three effective stress components) exist. If this study does not adopt the DGM, reducing the total number of unknowns must be implemented using available material properties (for example, a void ratio-stress relationship). The author’s Ph.D. thesis provided an example in which the void ratio is the unknown of a single and complex governing equation.

- The fourth difficulty is the non-homogeneity of clay’s properties. This difficulty represents the limitation of this study. Natural clay’s properties are non-homogeneous. Although we can create a particular probability model to regress the distribution of a clay’s property, there must be enough clay samples to provide accurate regression points. However, gathering clay samples of a natural soft clay layer is not easy. Probably due to this reason, it is unavoidable that the accuracy of predicted consolidation settlements is limited.

6. Conclusions and Concluding Remark

- Deriving the current mathematical model advances the modeling of a finite-strain engineering problem. The current governing equation is simple but adapts to the changes of the problem domain. Based on it, we can predict more accurate settlements.

- The DGM is a promising numerical method for resolving the difficulties of deducing sufficient governing equations or specifying full initial and boundary conditions in solving a partial differential equation.

- To obtain the desired accuracy of numerical results provided by the DGM, adopting a lower learning rate in training a deep neural network is preferred.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DGM | Deep Galerkin Method |

References

- Loktev, K.A.; Ulanov, I.; Shishkina, I.; Savulidi, M.; Klekovkina, N.; Kuznetsov, A. Determination of settlement parameters of highway embankment and base consolidation time depending on soil characteristics. Transp. Res. Proc. 2022, 63, 946–955. [CrossRef]

- Kamash, W.E.; Hafez, K.; Zakaria, M.; Moubarak, A. Improvement of soft organic clay soil using vertical drains. KSCE. J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25(2), 429–441. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.F.; Chang, M.-F.; Teh, C.I. and Na, Y.M. Back-calculation of consolidation parameters from field measurements at a reclamation site. Can. Geotech. J. 2001, 38(4), 755–769. [CrossRef]

- Biot, M.A. General theory of three-dimensional consolidation. J. Appl. Phys. 1941, 12(2), 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.E.; England, G.L.; Hussey, M.J.L. The theory of one-dimensional consolidation of saturated clays. Géotechnique 1967, 17(3), 261–273.

- Gibson, R.E.; Schiffman, R.L.; Cargill, K.W. Back-calculation of consolidation parameters from field measurements at a reclamation site. Can. Geotech. J. 2001, 38(4), 755–769. [CrossRef]

- Jeeravipoolvarn, S.; Scott J.D.; Chalaturnyk R. Multi-dimensional finite strain consolidation theory: Modeling study. In Proceedings of the 61st Canadian Geotechnical Conference and the 9th Joint CGS/IAH-CNC Groundwater Conference, Edmonton, AB, Canada, September 21-24, 2008; 167–175.

- Sheu, G.Y. A general finite strain consolidation theory. Ph.D. Thesis, National Cheung Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan, 1997.6.30.

- Malvern, L.E. Introduction to the Mechanics of a Continuous Medium, Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA, 1977.

- Justin S.; Konstantinos S.: DGM: A deep learning algorithm for solving partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2018, 375, 1339–1364.

- Huerta, A.; Rodriguez, A.: Numerical analysis of nonlinear large-strain consolidation and filling. Degree-Comput. Struct. 1992, 44(1), 357–365.

- Liu, S.J.; Sun, H.L.; Pan, X.D.; Shi, L.; Cai, Y.Q.; Geng, X.Y.: Analytical solutions and simplified design method for large-strain radial consolidation. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 134, 103987. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Yadav, N.; Nagar, A.K.: Numerical solution of Generalized Burger-Huxley & Huxley’s equation using deep Galerkin neural network method. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105289.

- Matsumoto, M.: Application of deep Galerkin method to solve compressible Navier-Stokes equations. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2021, 64(6), 348–357. [CrossRef]

- McVay, M.; Townsend, F.; Bloomquist, D.: Quiescent consolidation of phosphatic waste clays. J. Geotech. Eng. 1986, 112(11), 1033–1049. [CrossRef]

- Zen, K.; Umehara, Y. (2019). A new consolidation testing procedure and technique for very soft soils. In Consolidation of Soils: Testing and Evaluation; R. N. Yong; F. C. Townsend, Eds.; American Society for Testing and Materials: Philadelphia, USA; pp. 405–432.

- Cargill, K. W.: Prediction of consolidation of very soft soil. J. Geotech. Eng. 1984, 110(6), 775–795. [CrossRef]

- Hiroyuki T.; Jacques L.: A microstructural investigation of Osaka Bay clay: the impact of microfossils on its mechanical behaviour. Can. Geotech. J. 1999, 36(3), 493–508.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).