Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Setting

2.2. Sample Size and Recruitment Procedure

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Participants

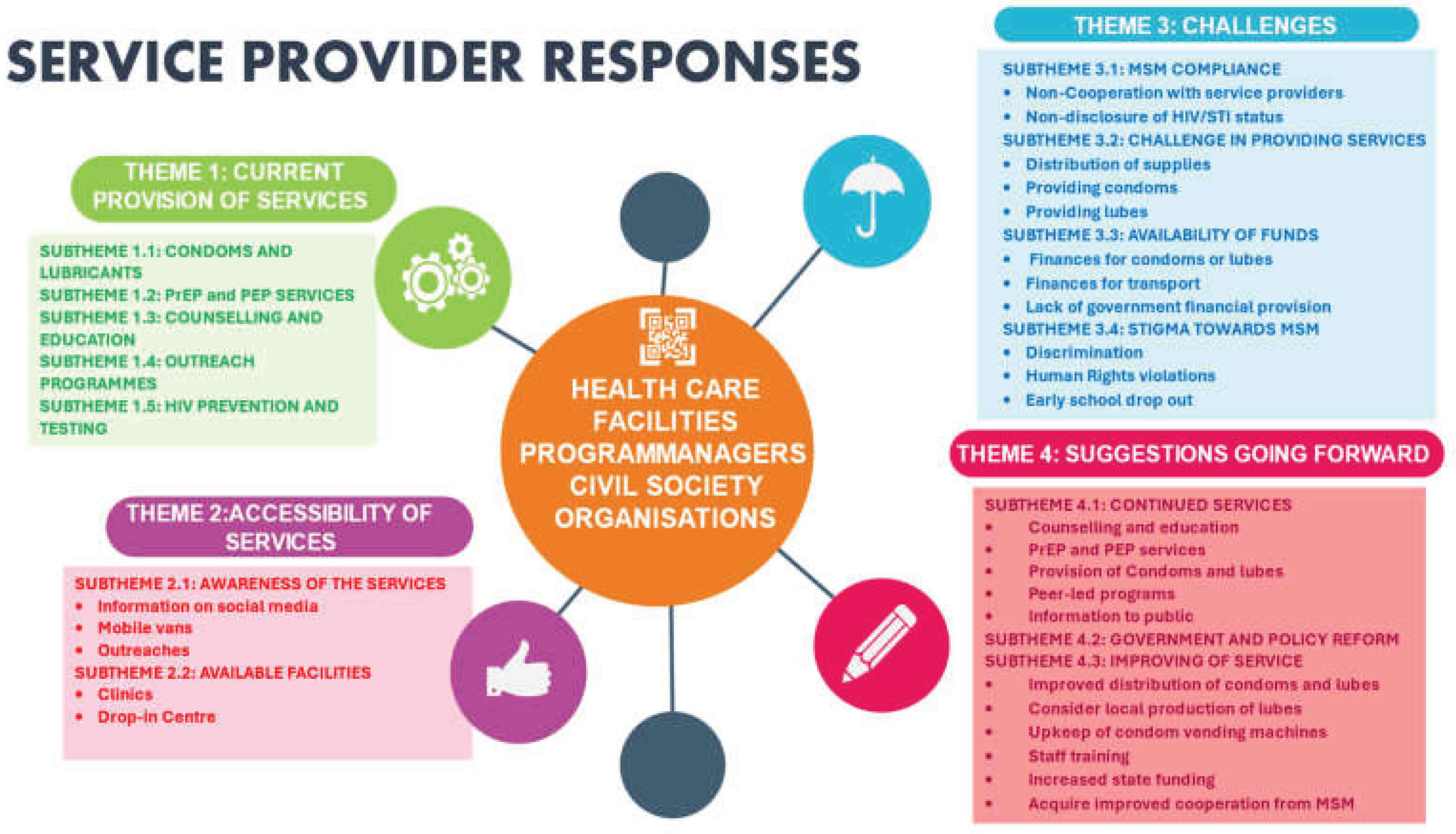

3.2. Interventions for Consistent and Correct Use of Condoms with Condom-Compatible Lubricants Among MSM in Ghana

“For the MSM, we do supply them with their condoms. The condoms that are available are already lubricated, so we don’t have plain condoms and lubes. There are lubricated condoms that are available that we give to them”. (Service provider H, 56 years old, female)

“We give them condoms and lubes, just that with the lubes we don’t have the quantity that we need, but for condoms, we have enough condoms”. (Service provider I, 45 years old, female)

“OK, so currently we have the flavoured condoms that are available at the Community level. We also have water-based lubricants, like in the sachet form, so the lubricants come in 5ml per sachet, and then we also have condoms. Usually, these condoms are no-label condoms, but they are they are flavoured condoms, so we have the strawberry flavour, we have banana flavour, and we have the lemon flavour. So, we have basically three main flavours that we use for our prevention programming”. (Service provider M, 39 years old, male)

“Apart from the condoms, we also give them the PrEP and the PEP”. (Service provider H, 56 years old, female)

“And you know that the major prevention intervention approach we have for the MSM community is condom and lubricant programming, even though we have PrEP as part of the prevention programme that we implement when it comes to combination prevention approaches”. (Service provider M, 39 years old, male)

“So basically, we do PrEP services at our end, and so when they come, it’s the whole package. So, we give them the PrEP medication in addition to the condom and lubricant programming”. (Service provider N, 31 years old, female)

“So, we have the peer educators, who are also MSMs who know their members very well and even where they can find them, and so we work through them to distribute condoms and lubricants and also educate them on how to use the condoms with the lubricants correctly and consistently. And we also do HIV sensitisation and screening among the population, making sure that they are properly educated on HIV and STIs preventive measures”. (Service provider P, 47 years old, male)

“There are other interventions, such as training peer educators to reach out to the community, to give education. So, the education is such that it is basically informing the volunteers about what HIV is and how to prevent it. So, we have something that we call prevention info as part of the education that we do. So, under prevention info, which is prevention information, they speak about HIV, the modes of transmission, and then how to prevent HIV, which is the usage, the correct and consistent use of condoms with lubricants, and the use of PrEP and then PEP”. (Service provider O, 29 years old, female)

“You know, we also give them education and sometimes even counsel them on the consistent and regular use of condoms and the lubricants. When you give them the condoms and you counsel and educate them, you know, they embrace everything. They absorb everything quickly, and then they feel the importance of using the lubricants with the condoms. So, the counselling and education go well. “ (Service providers J, 48 years old, female)

“So, during their refills, whenever they visit the clinic, we educate and remind them of the continuous use of these things, and then we supply them when they need be”. (Service provider L, 52 years old, female)

“The Commission (GAC) came out with several interventions to support MSMs, one of the key ones is the peer-led outreach that is using their own people to help them”. (Service provider K, 50 years old, female)

“OK, so we work on the Global Fund Grant Cycle 7 Projects and our target population, specifically, is MSM and transgender populations. And we have condom and lubricant programming, and the Community outreach intervention that we implement under the Global Fund Grant Cycle 7 Project. Now, basically, we are heavy on the condom and lubricant programming, and we rely on peer outreach volunteers as another form of interventional strategy, and the community outreaches to get condoms and lubricants to the MSM communities across the various districts that we work in “. (Service provider M, 39 years old, male)

“There are other interventions, such as training peer educators to reach out to the community, and outreach programmes by volunteers to give education. Apart from organising community outreach programmes where we distribute condoms and lubricants to them, and also give them education, the peer educators also used to do peer-led outreach to visit, educate, and distribute condoms and lubricants to them”. (Service provider O, 29 years old, female)

“We provide the full package, like testing for HIV, distributing flyers, and some of these Flyers educate them about condom and lubricant use”. (Service provider P, 47 years old, male)

“OK, so our major yielding point has been social media. There are trained cadres who are online on the various social media platforms, who get them to us, and who try to link them to us. We use digital platforms like social media. We also have Facebook, we have WhatsApp, and we have other dedicated platforms like Instagram”. (Service provider L, 52 years old, female)

“Ok, so some of the ways to reach out to them are community outreach programmes, the peer-led outreach programmes, that is, using their own people to help them; we train these peer-led groups to distribute condoms and water-based lubricant, directly to MSMs within their communities. The West African AIDS Foundation (WAAF) also uses the mobile spot to distribute condoms and lubricants to MSM. Well, for example, WAAF has a mobile van that goes out to provide services for their MSM clients”. (Service provider K, 50 years old, female)

“Ok. So, we mostly use peer educators and community outreach programmes to be able to distribute condoms and lubricants to them. So, you know, the MSM, they have something like cells or like circles. So, we have the peer educators, who are also MSMs who know their members very well and even where they can find them, and so we work through them to distribute condoms and lubricants”. (Service provider P, 47 years old, male)

“So as a clinical nurse at my place, it’s normally the walk-in that we do, but then we have the programming aspects that they also sometimes go do the distribution through community outreaches. But pertaining to me, we do give them the condoms and the lubricants when they come to the clinic”. (Service provider N, 31 years old, female)

“Another area that we’ve also leveraged is the drop-in centres. So, we have drop-in centres among the non-governmental and civil Society organisations implementing MSM programmes where it’s very convenient for the client or the person to go and access condoms and lubes”. (Service provider K, 50 years old, female)

“I see that if you have your preferred choice of sexual behaviour, and then you know that these are the risks that are involved, I think that you should even get your condom by yourself to protect yourself. You shouldn’t even wait for the health facilities to give it to you. We are giving it to them, but we still realise that the usage of the condom with lube is low. I have a typical story here where one person who was coming in as HIV negative MSM, we kept talking to him, giving him the condoms, and PrEP. We kept encouraging him to be coming, but little did we know that he was not using them consistently. We are giving them the condoms and PrEP, we are giving them the counselling, but the usage is low. Other challenges that we are facing, especially for my facility. I think that though we are doing a lot of education on protected sex, we don’t know whether it is really sinking in, or a behavioural thing that they still think that it’s better to do the lube alone without the condom. It’s something that is quite worrying “. (Service provider H, 56 years old, female)

“We do give them condom and lubricant education, but it’s not that intensive. So, the education that we give to them at the healthcare facility is not that detailed because most of them are usually in a hurry to leave”. (Service provider N, 31 years old, female)

“For those who quickly rush out because they are in a hurry to leave after receiving their condoms without the education and the counselling, the majority of them come with their partner, and you will see that all of them have tested either positive for STIs or even HIV”. (Service provider J, 48 years old, female)

“So when there are delays in the supply chain, it affects all of us. There will definitely be delays in bringing them into the country, and also when it comes to in-country, I think there’s also a delay between the FDA approval of these condoms and it being offloaded into the country. I heard we pay taxes and some charges at the port. We also have challenges sometimes with lubes. So, there are shortages, sometimes also with condoms, and therefore we may have an abundance of condoms here that we can distribute, but we wouldn’t have lubes to distribute, water-based lubricants to distribute, because sometimes there are shortages of lubes in the system”. (Service provider K, 50 years old, female)

“The other challenge, too, is that of finance, because when it comes to them buying the lubricant, it’s really a challenge, so you give them condoms, ask them to go and buy the lubricants, and they are not able to buy them. And then another challenge, too, is how to even sometimes get TNT (transport fare). You know, some of them, because of the stigma, they’ve even lost their jobs, and when it comes to them picking up a car to your place, though, they might not spend any huge amount of money, but sometimes even what they will use to buy water, some of them don’t have”. (Service provider I, 45 years old, female)

“The Ghana Government does not make enough provision for funds to be allocated in the budget for such activities to be given free to these community members”. (Service provider K, 50 years old, female)

“I sometimes have to chase it from the National AIDS control programme, at times the Ghana AIDS Commission. So, with all these other areas that I’m looking at to get these supplies, I will need a vehicle, delivery, transportation, or something. But because it is not coming from the mainstream medical stores that the hospital knows, it becomes difficult because it looks like an extra burden going out of the usual way to get supplies. Sometimes it’s done with our money. Sorry to say, but that’s the reality”. (Service provider L, 52 years old, female)

“Ok. So, one of our main challenges currently is that, because of the USAID policy shift on aid, the CSOs who are implementing HIV prevention programmes and activities are having serious challenges because they are not supposed to target KPs such as the MSM. They can provide services to the general population but can’t target any key population; otherwise, they are breaching the agreement”. (Service provider P, 47 years old, male)

“Yeah, most of the challenge is that. They stigmatise themselves first, and they feel that if anybody sees them, it’s a problem. So, self-stigma and discrimination by others are a barrier, especially for those living with HIV. So, sometimes they stigmatise themselves, and others also stigmatise them. That alone doesn’t make most of them come out to access HIV intervention services”. (Service provider J, 48 years old, female)

“Well, the challenges are enormous, honestly. They cut across various angles, ranging from human rights violations, abuse, and one major challenge we have faced as an organisation is the Human Sexual Rights and Family Values Bill that was introduced in 2021 and was passed by Parliament in 2023, I think last year. The challenge is that it created a hostile environment, and it pushed a lot of the KP Community into hiding, so it became very difficult to reach them and provide them services and those who will even come forward to access services are always also kind of like afraid and agitated and all that, so these are some of the main challenges that we’ve encountered. Human rights violations in terms of physical abuse, emotional abuse and harassment towards the MSM community are some of the major challenges that we continue to face in our implementation, and in fact also the programme staff as well also tend to face a lot of challenges in terms of our safety and security as well”. (Service provider M, 39 years old, male)

“I think that education has to go down well to be able to eliminate the stigma. The sensitisation of the public has gone down; therefore, we need to sensitise the general public to know that everyone has what they want to do. So, you don’t need to look down on someone. Just like how some are doing on malaria and TB, the education has to be intensified so that people will accept it. We should also educate and sensitise both healthcare workers and the general public on the implications of the stigma and how bad it can be for all of us as a country in terms of achieving HIV epidemic control and eliminating STIs “. (Service provider I, 45 years old, female)

“The Ghana Government must make a provisional allocation of funds to be used in the budget for the procurement of condoms and lubricants to be given free to these community members in the short term”. (Service provider L, 52 years old, female)

“OK. So, as we talked about policies, I think policy reforms and constitutional reforms are very essential in addressing the stigma, discrimination, and the hostility. So in order to be able to address stigma and discrimination, human rights abuses and violations and all the issues that exist within the key population implementation space, we really need reforms and the reforms must include decriminalisation of existing laws that criminalise the activities of MSM and other communities that have been raised under these laws, otherwise, any other policy we implement will be in vain because if the very community you are implementing those programmes for, are criminalised of course everything will be in vain, we have instances where our team has gone for an outreach and police have arrested them because they are suspected to be part of a certain community or they are suspected to be provided services or supporting the activities of MSM”. (Service provider M, 39 years old, male)

“The provision of services to MSM communities must rely more on the use of peer educators to deliver their services. For instance, we, at the Ghana AIDs Commission, when we have condoms, we have ways in which we are able to channel some to the MSM community. That is where we mostly use their peer educators. So, it is necessary that more peer educators are trained for this purpose. Service providers also need to train their staff to be understanding and empathetic to handle MSM-related issues and provide services to them without any form of judgment or prejudice”. (Service provider P, 47 years old, male)

“Again, in terms of condoms and lubricant distribution, we can also use the condom vending machines at strategic places to deliver them. We must have the condom vending machines at strategic locations where we can feed the condoms in so that people could just put in a 20 pesewa coin and it dispenses it for them”. (Service provider P, 47 years old, male)

“The government should also incentivise some of the local manufacturing and pharmaceutical companies to start producing condoms and sachet lubricants to be used locally and stop relying on foreign AIDS”. (Service provider M, 39 years old, male)

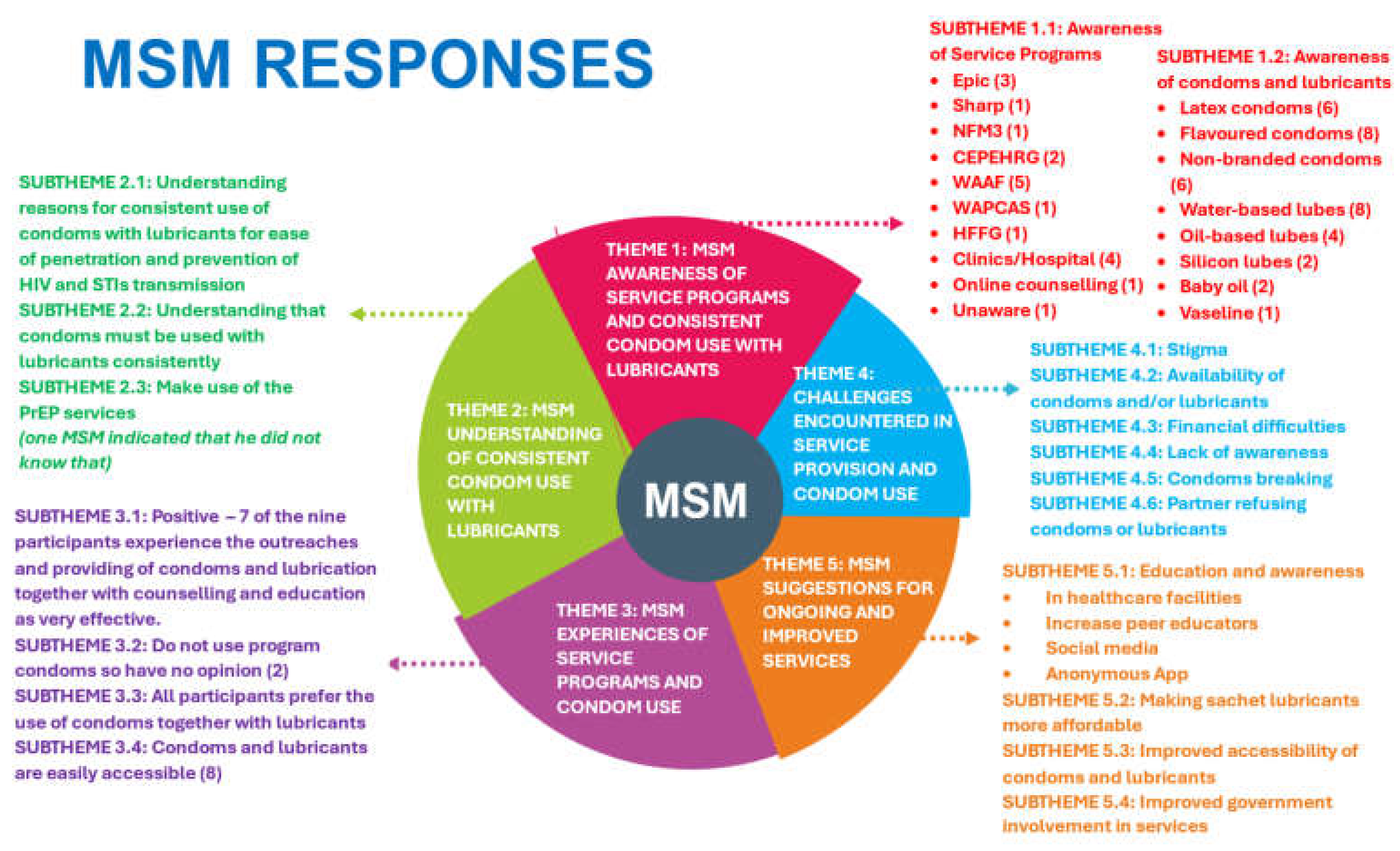

“OK, so I know about the Epic programme. I know sharper programmes. I know sharp programmes. And then there is a recent programme also going on, which is. I have forgotten the full name, but I know I also know about the NFM 3 projects. So, Epic focuses on interventions such as community outreaches or reaching out to MSM, or let’s say, MSM community members. Educating us on HIV, condoms, and the correct use of condoms and lubricants. The Epic programme also comes with distributing condoms and sometimes lubricants and counselling MSM community members. Also, those who are eligible to be enrolled on PrEP and those who test positive are also initiated on ARVs, and that applies to all the prevention programmes I have mentioned”. (MSM A, 28 years old, Gay)

“Yeah. Ok, I know about some NGO’s like WAAF and HFFG that have some interventions in place for the MSM community members. Emmm, because of the stigma, we prefer vulnerable populations so that we are not easily identified and harmed. Both WAAF and HFFG have interventions that enable the community members to use condoms and lube consistently and correctly so that we can protect ourselves from HIV and other STIs. They give us education on the correct and consistent use of condoms with lubricants. Again, they organise outreach programmes where they give us condoms and lube, that’s the water-based one. Apart from the education they give us and the sharing of the condoms and lubes, they also train some of the vulnerable people to become peer educators who also check on us and distribute condoms and lubricants to us. The peer educators always make sure that we have what we need to protect ourselves”. (MSM D, 30 years old, Gay)

“For the condoms, I only knew about those they sell in the pharmacy, like ..eemm the latex condoms, Durex, Fiesta Classic condoms, and flavoured condoms and also a UK-based condom called Skyn condom, until I started going for outreach programmes where we always get the programme condoms or the non-branded ones. And for the lubes, I know of water and oil-based lubes, but we don’t always get the lubes from our people”. (MSM B, 25 years old, Bisexual)

“As for the condoms and lubes, I know Durex, latex, flavoured, silicone lubricant, water-based lubricant ..eemm, but I personally use the programme condoms and the water-based lubricants. There are times that I don’t have water-based lubricants, so I also use oil-based lubricants. emmm.. that is baby oil that I buy from cosmetic shops”. (MSM E, 26 years old, Bisexual)

“Yeah. I know Durex, latex, the flavoured condoms, and the programme, or the non-branded condoms. Ok, and as for the lubricant, I know only about silicone and water-based ones. Yes, personally, I use the water-based lubricant. We get them without paying anything, but in most cases we don’t get the lubes from the store, so I buy my own lubes, but it’s expensive”(MSM D, 30 years old, Gay)

“I don’t think it would be comfortable or safe to use a condom without the lubricant. So yeah, I think it’s definitely better to use condoms with the lubricant every time. I mean, when you apply the right lubricant, it makes the penetration easy without friction; condoms also don’t break unless one doesn’t open them appropriately, and then sex becomes pleasurable. The most important thing is that using it together with the lubricant protects oneself from HIV and STIs, since there is no skin-to-skin contact, there can’t be transmission”. (MSM F, 30 years old, Queer)

“I think both are important because personally, I know people who are like, oh, the condom alone doesn’t make them have that sexual urge, it looks like it prevents them from having that intimate feeling. But when they are used with the lubricants, they become more, they have more of the body touch, more like the body touch. So, I think both work perfectly. Yes, yes, yes, it also allows for smooth penetration and in that case, there is little or no chance for the condom to break; hence, using both condoms with lubricants ensures safety and prevents someone from getting HIV or STIs from an infected person”. (MSM G, 26 years old, Bisexual)

“So, how well I understand it is that I know that I have to use the condom with the lubricant...emm, the water-based lubricant anytime that I sleep with someone. And it gives the opportunity not to be infected with STIs or HIV.”. (MSM A, 28 years old, Gay)

“For me, what I know is that if you use the condoms with the lubricants to protect yourself, it’s more protective than other stuff because even though we know about PrEP, which we also use but the PrEP can only prevent you from HIV and not other STIs you can get them. So, by using condoms with lube, I think you are free. So, we must always use the condoms with the lubes every time to protect ourselves. This is how I understand consistent and correct use”. (MSM E, 26 years old, Bisexual)

“Ok, like I said earlier, all the interventions that I know of are effective collectively. Just one single intervention cannot be that effective in making sure that condoms with lubes are used consistently and correctly. We need the education, giving out the free condoms and the lubes and the counselling to make it work”. (MSM D, 30 years old, Gay)

“Ok. As for the interventions, I will say that combining the education and the advice that they give us, counselling us, and also getting access to the condoms and lubes from outreach programmes, in my view, is effective. Because if I have the condom or lube and I don’t know how to use it properly, it cannot protect me from HIV or STIs. What I want to say is that the education, the counselling, and having the condoms and lubes all combined make it effective”. (MSM B, 25 years old, Bisexual)

“About the effectiveness of the various programmes or interventions, that will be very hard to say because it will be a bias for me to say that a particular programme is not really effective when I’m linked to a different programme and not that one. Well, I can’t speak much about what I don’t know”. (MSM C, 21 years old, Gay)

“Yes, I always use condoms and lubricants anytime. That’s more consistent and correctly, like using all the time, no matter who you are. I like to learn and do research, so I know the figures. I mean the HIV prevalence. I think that as of now, it is at 26.1. People are infected with HIV, so if you really want to protect yourself, you know, you have to use it always. So, for me personally, I use them always. Using condoms with lubricants is very good because when I started using them, I didn’t experience friction anymore during penetration…eemm and now the pleasure is much more enjoyable, especially with the Skyn condom, and I also don’t experience condom breakage when I use the condom with the water-based lube. When the condom doesn’t break, it saves me from any sexually transmitted infection and HIV”. (MSM B, 25 years old, Bisexual)

“Ok, personally, for me, I prefer to use condoms with lube, which is the best because it makes penetration easy, reduces friction, and even enhances pleasure. The condoms don’t break or tear when lubricants are used, so they prevent skin contact and prevent one from contracting STIs and HIV. “(MSM D, 30 years old, Gay)

“Yes. Wherever I need condoms and lubes, I call my peer educator, and he comes home to give me some, even if it’s midnight, because we stay in the same area. And for the lubricants, I make sure to buy some from the pharmacy because the lubes are not always available from him”. (MSM B, 25 years old, Bisexual)

“Yes, I have easy access to the condoms in particular. Immediately, I’m short on items, some of them I have their numbers, I just call them, and they bring me some, and even the peer educator who mostly comes to me, I have his contact, so anytime that I need something, I just have to contact him”. (MSM E, 28 years old, Bisexual)

“Sometimes there is self-stigma, especially when you are in a community where you feel shy to walk into a bar or a pharmacy to buy condoms and then also buy lubricant as well because they mean to buy condoms and lubricant, it tells the person you are going to have either anal sex or any other kind of sex”. (MSM A, 28 years old, Gay)

“Some of our community members wouldn’t want to come out for outreach programmes to be identified or something due to fear of stigmatisation, criminalisation, and others. “. (MSM C, 21 years old, Gay)

“Yeah, I do. And because of the intervention programmes in the MSM communities, we have volunteers that ...eemm share condoms and lubricants at a free space when we attend like outreach programmes, we get condoms free, and then we get lubricants free. It’s not for sale unless you are at a place where you need to get some, but you don’t have any peer educators or any volunteers who work within any of your friendly NGOs who have it; then you would have to buy it”. (MSM A, 28 years old, Gay)

“Sometimes people are not used to the brand that is being given out for free, and...eemm, your skin might react to what is being given for free. Sometimes, when you don’t have the funds to afford what is actually good for you, it becomes a challenge”. (MSM A, 28 years old, Gay)

“Like I said, sometimes we don’t have the lubricant, and buying it is also expensive. There are times that I have condoms, but when I call my peer educator, he does his best to get me at least what I will use for that day”. (MSM D, 30 years old, Gay)

“Some people are not aware that there are even organisations out there intervening on behalf of we in the community, and also most people don’t know about the benefits of these packages”. (MSM B, 25 years old, Bisexual)

“A first when I didn’t know about the water-based lube, I used to sometimes experience condom breakage or tear when I was not using lubes, so it some kind of prevent easy entry and some lubricants can also make the condom weak and cause it to break, probably due to the friction, and penetration gets difficult”. (MSM D, 30 years old, Gay)

“Well, there are people who say they don’t like the condoms and the lubes. I meet people who say that they don’t use condoms, but it’s not my thing. So, I will insist on using condoms or no sex at all”. (MSM F, 30 years old, Queer)

“I don’t have difficulties in getting condoms because I’m in the city, and it’s easy to get condoms. There are about 5 pharmacies around me, so even if I don’t get it from my peer educators, I’m going to get it there, but the only challenge is that I meet people who are like they want raw sex, in that case, the conversation has to end right there”. (MSM G, 26 years old, Gay)

“There can be consistent public education to increase awareness among the MSM community members, using peer educators to reach out to members…eemm I’m a benefactor, so I know what I’m talking about. Public awareness can be done through social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Television channels”. (MSM B, 25 years old, Bisexual)

“…eemm producing lubes in sachet forms to reduce cost and increase availability. Yeah, that’s by making the sachet lubricants more affordable and available so that the pockets can afford”. (MSM A, 28 years old, Gay)

“The companies should also produce sachet lubricants that are affordable so that we can always buy them. It will be very good if sachet lubricants can flow just like the way condoms are always or mostly available”. (MSM D, 30 years old, Gay)

“To make the condoms easily accessible to us, there should be a continuous supply to our peer educators so that anytime we need some, we can contact them. Yes, they are close to us and getting it from them is very easy than going out to the public”. (MSM D, 30 years old, Gay)

“Also, the government must set up a company to produce locally produced sachet lubricants that are also affordable to the community members”. (MSM D, 26 years old, Bisexual)

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Ghana AIDS Commission. Ghana Aids Commission Ghana Men’s Study II. 2017; Available from: https://www.ghanaids.gov.gh/mcadmin/Uploads/Ghana Men%27s Study Report(2).pdf.

- Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC. HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. Int J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2010 Apr 20 [cited 2025 Jun 18];39(4):1048. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2929353/.

- Mayer KH, Wheeler DP, Bekker LG, Grinsztejn B, Remien RH, Sandfort TGM, et al. Overcoming biological, behavioral, and structural vulnerabilities: New directions in research to decrease HIV transmission in men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet]. 2013 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Jun 18];63(SUPPL. 2). Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jaids/fulltext/2013/07012/overcoming_biological,_behavioral,_and_structural.10.aspx.

- Jin F, Jansson J, Law M, Prestage GP, Zablotska I, Imrie JCG, et al. Per-contact probability of HIV transmission in homosexual men in Sydney in the era of HAART. AIDS [Internet]. 2010 Mar [cited 2025 Jun 18];24(6):907–13. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/fulltext/2010/03270/per_contact_probability_of_hiv_transmission_in.14.aspx.

- UNAIDS. Key Populations Atlas [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 18]. Available from: https://kpatlas.unaids.org/dashboard.

- Wiyeh AB, Mome RKB, Mahasha PW, Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS. Effectiveness of the female condom in preventing HIV and sexually transmitted infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–17.

- Giannou FK, Tsiara CG, Nikolopoulos GK, Talias M, Benetou V, Kantzanou M, et al. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on HIV serodiscordant couples. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res [Internet]. 2016 Jul 3 [cited 2024 Oct 20];16(4):489–99. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26488070/.

- USAID. Condom fact sheet. Usaid [Internet]. 2015;26(April):1–2. Available from: https://www.globalhealthlearning.org/sites/default/files/reference-files/condomfactsheet.pdf.

- Barcavage Shaun Haun. How well do condoms protect gay men from HIV? San Fr AIDS Found [Internet]. 2016;1–8. Available from: https://www.sfaf.org/collections/beta/how-well-do-condoms-protect-gay-men-from-hiv/.

- Ghana. Plans, Strategies & Reports - National Strategic Plans & Reports [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 May 19]. Available from: https://www.ccmghana.net/index.php/strategic-plans-reports.

- Nelson LRE, Wilton L, Agyarko-Poku T, Zhang N, Zou Y, Aluoch M, et al. Predictors of condom use among peer social networks of men who have sex with men in Ghana, West Africa. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015 Jan 30 [cited 2025 May 19];10(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25635774/.

- Abdulai R, Phalane E, Atuahene K, Kwao ID, Afriyie R, Shiferaw YA, et al. Consistency of Condom Use with Lubricants and Associated Factors Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Ghana: Evidence from Integrated Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2025 Apr 1 [cited 2025 May 19];22(4):599. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12026881/.

- CDC. Preventing HIV with Condoms [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 18]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/condoms.html.

- World Health Organization. Condoms Key facts [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 18]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/condoms.

- Stover J, Teng Y. The impact of condom use on the HIV epidemic. Gates Open Res. 2022;5.

- UNAIDS. Condom and lubricant programming in high HIV prevalence countries [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2025 May 18]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2015/Condomlubricantprogramming.

- Ghana AIDS Commission. National HIV & AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2021-2025. Angew Chemie Int Ed 6(11), 951–952. 2021;2013–5.

- Kushwaha S, Lalani Y, Maina G, Ogunbajo A, Wilton L, Agyarko-Poku T, et al. “But the moment they find out that you are MSM…”: a qualitative investigation of HIV prevention experiences among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Ghana’s health care system. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2017 Oct 3 [cited 2025 Feb 26];17(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28974257/.

- Beyrer C. Global prevention of HIV infection for neglected populations: men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2010 May 15 [cited 2024 Oct 20];50 Suppl 3(SUPPL. 3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20397938/.

- Fay H, Baral SD, Trapence G, Motimedi F, Umar E, Iipinge S, et al. Stigma, health care access, and HIV knowledge among men who have sex with men in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2011 Aug [cited 2024 Oct 20];15(6):1088–97. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21153432/.

- Rebe K, Semugoma P, McIntyre J. New HIV prevention technologies and their relevance to MARPS in African epidemics. Sahara J [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2024 Oct 20];9(3):164–6. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17290376.2012.744168.

- Osse L. Ghanaians are united and hospitable but intolerant toward same-sex relationships. 2021;(Afrobarometer Dispatch Dispatch No. 461):1–9.

- Ghana. Human Dignity Trust [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 18]. Available from: https://www.humandignitytrust.org/country-profile/ghana/.

- Persson A, Ellard J, Newman C, Holt M, De Wit J. Human rights and universal access for men who have sex with men and people who inject drugs: A qualitative analysis of the 2010 UNGASS narrative country progress reports. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2011 Aug 1 [cited 2025 May 18];73(3):467–74. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277953611003376?via%3Dihub.

- Williamson R, Wondergem P, J. RAH& HR, 2014 U. Using a reporting system to protect the human rights of people living with HIV and key populations: a conceptual framework. 2014 [cited 2025 May 18]; Available from: https://www.hhrjournal.org/2014/07/01/using-a-reporting-system-to-protect-the-human-rights-of-people-living-with-hiv-and-key-populations-a-conceptual-framework/.

- Ayala G, Makofane K, Santos GM, Beck J, Do TD, Hebert P, et al. Access to Basic HIV-Related Services and PrEP Acceptability among Men Who Have sex with Men Worldwide: Barriers, Facilitators, and Implications for Combination Prevention. J Sex Transm Dis [Internet]. 2013 Jul 8 [cited 2025 May 18];2013:953123. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4437423/.

- Poteat T, Diouf D, Drame FM, Ndaw M, Traore C, Dhaliwal M, et al. HIV Risk among MSM in Senegal: A Qualitative Rapid Assessment of the Impact of Enforcing Laws That Criminalize Same Sex Practices. PLoS One [Internet]. 2011 Dec 14 [cited 2025 May 18];6(12):e28760. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0028760.

- Abdulai R, Phalane E, Atuahene K, Phaswana-Mafuya RN. Consistent and Correct Use of Condoms With Lubricants and Associated Factors Among Men Who Have Sex With Men from the Ghana Men’s Study II: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Res Protoc [Internet]. 2024 Dec 3 [cited 2024 Dec 26];13(1):e63276. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39626229.

- Abdulai R, Phalane E, Atuahene K, Phaswana-Mafuya RN. Consistent Condom and Lubricant Use and Associated Factors Amongst Men Who Have Sex with Men in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Sexes 2024, Vol 5, Pages 796-813 [Internet]. 2024 Dec 23 [cited 2024 Dec 26];5(4):796–813. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2411-5118/5/4/51/htm.

- Colorafi KJ, Evans B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. Heal Environ Res Des J [Internet]. 2016 Jul 1 [cited 2025 May 19];9(4):16–25. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26791375/.

- Ghana. Republic of Ghana: Key facts. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 30].African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Available from: https://achpr.au.int/en/member-states/ghana.

- Rosenberg NE, Graybill LA, Wesevich A, McGrath N, Golin CE, Maman S, et al. The Impact of Couple HIV Testing and Counseling on Consistent Condom Use among Pregnant Women and their Male Partners: An Observational Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet]. 2017 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jun 14];75(4):417. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5493523/.

- Bom RJM, Van Der Linden K, Matser A, Poulin N, Schim Van Der Loeff MF, Bakker BHW, et al. The effects of free condom distribution on HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2019 Mar 4 [cited 2025 Jun 14];19(1):1–10. Available from: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-019-3839-0.

- Boily MC, Pickles M, Lowndes CM, Ramesh BM, Washington R, Moses S, et al. Positive impact of a large-scale HIV prevention programme among female sex workers and clients in South India. AIDS [Internet]. 2013 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jun 14];27(9):1449. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3678895/.

- Rachakulla HK, Kodavalla V, Rajkumar H, Prasad SPV, Kallam S, Goswami P, et al. Condom use and prevalence of syphilis and HIV among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India – following a large-scale HIV prevention intervention. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2025 Jun 14];11(Suppl 6):S1. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3287547/.

- Halperin DT, Mugurungi O, Hallett TB, Muchini B, Campbell B, Magure T, et al. A Surprising Prevention Success: Why Did the HIV Epidemic Decline in Zimbabwe? PLoS Med [Internet]. 2011 Feb [cited 2025 Jun 14];8(2):e1000414. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3035617/.

- Johnson LF, Hallett TB, Rehle TM, Dorrington RE. The effect of changes in condom usage and antiretroviral treatment coverage on human immunodeficiency virus incidence in South Africa: a model-based analysis. J R Soc Interface [Internet]. 2012 Jul 7 [cited 2025 Jun 14];9(72):1544. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3367823/.

- Carvalho FT, Gonçalves TR, Faria ER, Shoveller JA, Piccinini CA, Ramos MC, et al. Behavioral interventions to promote condom use among women living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Sep 7;2012(2).

- Jommaroeng R, Richter KA, Chamratrithirong A, Soonthorndhada A. The effectiveness of national HIV prevention education program on behavioral changes for men who have sex with men and transgender women in Thailand. J Heal Res. 2020 Jan 14;34(1):2–12.

- Sabin LL, Semrau K, Desilva M, Le LTT, Beard JJ, Hamer DH, et al. Effectiveness of community outreach HIV prevention programs in Vietnam: A mixed methods evaluation. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2019 Aug 16 [cited 2025 Jun 14];19(1):1–17. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-019-7418-5.

- Johansson K, Persson KI, Deogan C, El-Khatib Z. Factors associated with condom use and HIV testing among young men who have sex with men: a cross-sectional survey in a random online sample in Sweden. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2018 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Dec 17];94(6):427–33. Available from: https://sti.bmj.com/content/94/6/427.

- Ako EY. Same-sex relationships and recriminalisation of homosexuality in Ghana. Socioling Stud [Internet]. 2023 Nov 4 [cited 2025 Jun 3];17(1–3):45–65. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1558/sols.24077?download=true.

- Fiaveh DY. LGBQ+ in Ghana: Analysing local and Western discourses. Socioling Stud. 2023 Aug 7;17(1–3):21–43.

- Coleman TE, Ako EY, Kyeremateng JG. A human rights critique of Ghana’s Anti-LGBTIQ+ Bill of 2021. African Hum Rights Law J [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 3];23(1):96–125. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1996-20962023000100006&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en.

- Dibble KE, Baral SD, Beymer MR, Stahlman S, Lyons CE, Olawore O, et al. Stigma and healthcare access among men who have sex with men and transgender women who have sex with men in Senegal. SAGE Open Med [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jun 15];10:20503121211069276. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9066634/.

- UNAIDS. Criminalising Homosexuality and Public Health: Adverse Impacts on the Prevention and Treatment of HIV and AIDS 3 2. 2014 [cited 2025 Jun 15]; Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf.

- Olakunde BO, Adeyinka DA, Ozigbu CE, Ogundipe T, Menson WNA, Olawepo JO, et al. Revisiting aid dependency for HIV programs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Public Health [Internet]. 2019 May 1 [cited 2025 Jun 15];170:57–60. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0033350619300526.

- UNAIDS. Condoms and lubricants in the time of COVID-19 — Sustaining supplies and people-centred approaches to meet the need in low- and middle-income countries — A short brief on actions, April 2020. 2020;(April):1–3. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/condoms-lubricants-covid19_en.pdf.

- Madiba S, Letsoalo B, Madiba S, Letsoalo B. Disclosure, Multiple Sex Partners, and Consistent Condom Use among HIV Positive Adults on Antiretroviral Therapy in Johannesburg, South Africa. World J AIDS [Internet]. 2014 Feb 26 [cited 2025 Jun 18];4(1):62–73. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=43584.

- Ajayi AI, Ismail KO, Akpan W. Factors associated with consistent condom use: a cross-sectional survey of two Nigerian universities. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2019 Sep 2 [cited 2025 Jun 18];19(1):1207. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6719351/.

- Wei C, Lim SH, Guadamuz TE, Koe S. HIV Disclosure and Sexual Transmission Behaviors among an Internet Sample of HIV-positive Men Who Have Sex with Men in Asia: Implications for Prevention with Positives. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2012 Oct [cited 2025 Jun 15];16(7):1970. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3340458/.

- Ngure K, Mugo N, Celum C, Baeten JM, Morris M, Olungah O, et al. A Qualitative Study of Barriers to Consistent Condom Use among HIV-1 Serodiscordant Couples in Kenya. AIDS Care [Internet]. 2011 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Jun 15];24(4):509. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3932299/.

- Thapa S, Ogunleye TT, Shrestha R, Joshi R, Hannes K. Increased Stigma, and Physical and Sexual Violence Against Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis Analyzing Social and Structural Barriers to HIV Testing and Coping Behaviors. J Homosex [Internet]. 2024 Jan 28 [cited 2025 Jun 15]; Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00918369.2024.2320237.

- Operario D, Sun S, Bermudez AN, Masa R, Shangani S, van der Elst E, et al. Integrating HIV and mental health interventions to address a global syndemic among men who have sex with men. lancet HIV [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jun 15];9(8):e574. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7613577/.

| Participants | • MSM, HIV healthcare service providers, programme or technical coordinators, and programme managers from HIV-focused CSOs who provide MSM with interventions to ensure consistent and correct use of condoms with lubricants. |

| Inclusion criteria | • Healthcare workers, programme or technical coordinators, programme managers in HIV prevention, and aged eighteen years and above. • Individuals who provided informed consent to participate in the study. • Those working in the area of HIV prevention and care among Key populations for at least 1 year. • Those who could speak English or at least one local dialect. |

| Exclusion criteria | • Individuals who were below eighteen years old. • Individuals who did not give their consent to participate in the study. • Service providers with less than a year of experience in HIV control and prevention among key populations. • Individuals who could not speak English or at least one local dialect. |

| Service Providers and MSM respondents | Age | Gender/sexual orientation | Employment | Role |

| A | 28 | Gay | Self-employed | Buys and sells electrical appliances |

| B | 25 | Bisexual | National Service personnel | Internship |

| C | 21 | Gay | Unemployed | None |

| D | 30 | Gay | Employed | Insurance agent |

| E | 28 | Bisexual | Self-employed | Hairstylist |

| F | 30 | Queer | Employed | Operations manager |

| G | 26 | Gay | Employed | Event organiser on Social Media Marketer |

| H | 56 | Female | Employed | Data manager at the ART unit and a Counsellor. |

| I | 45 | Female | Employed | Public Health Nurse |

| J | 48 | Female | Employed | Clinical and Public Health Nurse |

| K | 50 | Female | Employed | Regional Technical Coordinator at the Technical Support Unit, Ghana AIDS Commission, Accra. |

| L | 52 | Female | Employed | Public Health Nurse |

| M | 39 | Male | Employed | Programme Manager |

| N | 31 | Female | Employed | Clinical Nurse |

| O | 29 | Female | Employed | Monitoring and Evaluation |

| P | 47 | Male | Employed | Regional Technical Coordinator, Ghana AIDS Commission, Accra. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).