1. Introduction

Nurse managers are pivotal in translating organizational policies into frontline healthcare operations. Their competencies—including supervision, staff development, communication, fiscal management, and strategic planning—directly affect workforce stability, patient safety, and quality of care. [

1,

2]. Globally, nursing shortages have intensified due to increased demand, staff burnout, and heightened turnover, a trend accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic [

3,

4]. These workforce challenges have profound implications, including diminished patient outcomes, increased costs, and reduced organizational efficiency.

In Saudi Arabia, the healthcare system is undergoing significant transformation under Vision 2030, emphasizing leadership development, workforce sustainability, and quality improvement [

5,

6]. Nurse managers are central to achieving these goals; however, gaps often exist between managers’ self-perceived competencies and staff nurses’ perceptions, which may contribute to turnover intentions, reduced job satisfaction, and compromised care quality [

1,

3,

7].

While leadership competency is widely studied, few investigations have systematically explored perception gaps between managers and staff nurses in relation to retention, particularly in Middle Eastern healthcare settings. Studies addressing this misalignment are limited, highlighting a critical knowledge gap in understanding how leadership deficiencies directly influence turnover [

1,

3,

7].

This study addresses this gap by investigating perceived competency gaps in nurse leadership, their relationship to staff nurse turnover intentions, and the role of demographic characteristics, providing insights applicable globally.

1.1. Aim

To explore nurse manager competency gaps, their association with staff nurse turnover intentions, and the influence of demographic characteristics.

1.2. Research Questions

What competency gaps do staff nurses perceive in their nurse managers?

How do nurse managers’ self-perceptions compare with staff nurses’ perceptions?

How are competency gaps associated with staff nurse turnover intentions?

Do demographic characteristics (age, experience, education) influence perceptions of competency gaps and turnover intention?

1.3. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

The present study is grounded in a combination of leadership and behavioral theories that provide a comprehensive understanding of how nurse manager competencies affect staff nurse turnover intentions. The Three-Skills Approach to Management, originally proposed by Katz [

8], emphasizes that effective leadership requires a combination of technical, human, and conceptual skills [

8]. Technical skills reflect clinical knowledge and operational proficiency, human skills involve communication and interpersonal effectiveness, and conceptual skills encompass strategic thinking and problem-solving. In the context of nursing, these competencies are critical for ensuring safe, efficient, and high-quality care delivery. This framework supports the study by identifying the core competencies required for nurse managers to lead their teams effectively and highlights potential gaps that could influence staff retention.

Complementing this, the Transformational Leadership Theory [

9] underscores the importance of leaders who inspire, intellectually stimulate, and individually support their staff. Transformational leadership has been shown to foster engagement, commitment, and resilience among nursing personnel, which can directly influence staff satisfaction and intention to remain in their positions. The inclusion of this theory allows the study to examine not only the skills and tasks of nurse managers but also the relational and motivational aspects of leadership that shape nurses’ perceptions and behaviors.

Finally, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [

10] provides a behavioral lens for understanding how perceived leadership gaps translate into turnover intentions among staff nurses. TPB posits that behavioral intentions are influenced by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. This study helps explain how staff nurses’ perceptions of their managers’ competencies influence their intention to leave and why demographic characteristics, such as experience, age, and education, might alter these perceptions. The integration of TPB ensures that the study addresses both the managerial competencies themselves and the cognitive processes that mediate how these competencies affect turnover behaviors.

By combining these three theoretical perspectives, the study establishes a robust framework to examine the mechanisms by which leadership competencies—or the lack thereof—influence workforce retention in nursing.

1.4. Conceptual Framework

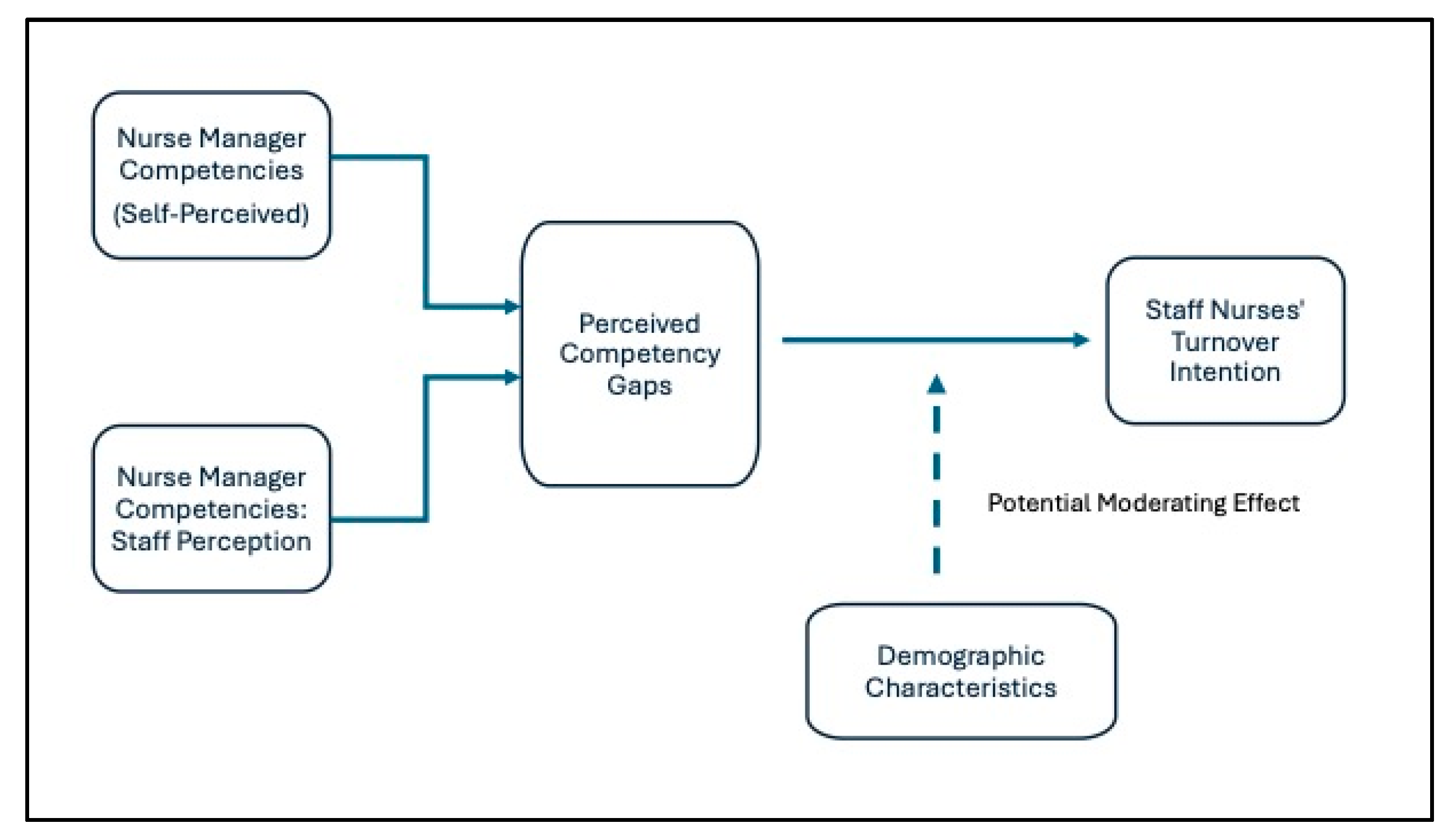

The conceptual framework of this study depicts the relationships among nurse manager competencies, perceived competency gaps, staff nurse turnover intention, and demographic characteristics as potential moderators. Nurse manager competencies—measured across domains such as recruitment, retention strategies, and supervisory responsibilities—form the independent variable. Perceived competency gaps, operationalized as differences between managers’ self-assessments and staff nurses’ perceptions, act as the primary explanatory variable influencing staff nurses’ turnover intentions, the dependent outcome.

Demographic characteristics—including age, experience, and education—are conceptualized as potential moderating factors that could influence the strength of the relationship between perceived gaps and turnover intention. For instance, less experienced nurses may be more sensitive to leadership deficiencies, which could intensify the impact of competency gaps on their intention to leave, whereas more experienced nurses may tolerate certain gaps. Although formal moderation analysis was not conducted in this study, incorporating demographics in the conceptual framework highlights avenues for future research to explore tailored interventions.

Figure 1 visually represents this framework: nurse manager competencies influence perceived gaps, which in turn affect turnover intention, with demographics positioned as potential moderators influencing the perceived gap–turnover link. This framework not only reflects the empirical focus of the study but also aligns with global and regional evidence suggesting that leadership gaps and individual nurse characteristics jointly shape retention outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

A cross-sectional, descriptive-correlational design was employed. Data were collected from two tertiary governmental hospitals located in Riyadh and Dammam, Saudi Arabia. This study used a dual-rater approach: nurse managers and staff nurses evaluated the same two constructs—(i) nurse-manager competencies and (ii) staff nurses’ turnover intention—providing complementary perspectives on leadership enactment and workforce outcomes.

2.2. Participants

The study included 225 staff nurses and 171 nurse managers (n = 396). Inclusion criteria required at least one year of experience, with staff nurses providing direct patient care and managers holding supervisory and administrative responsibilities. Managers were eligible if they had direct line responsibility for nursing staff; staff participants were eligible if they reported to a nurse manager. Participant characteristics, including age, gender, education, experience, and marital status, were collected (

Table 1).

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Nurse Manager Competency Inventory (NMCI): developed by DeOnna [

11] and measures competencies across 11 domains (staff retention, recruitment, supervisory responsibilities, patient safety, quality improvement, professional practice models, fiscal planning, communication, community/organizational outreach, and self-development). It contains 93 items scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). The NMCI has demonstrated high reliability (α = 0.93) and has been validated in previous studies [

11,

12,

13]. In the present study, analyses focused on unit-proximal domains most relevant to workforce stability and day-to-day leadership: Promote Staff Retention, Recruit Staff, Perform Supervisory Responsibilities, Ensure Patient Safety & Quality Care, Lead Quality Improvement, Conduct Daily Unit Operations, Manage Fiscal Planning, Facilitate Interpersonal/Group/Organizational Communication, and Facilitate Staff Development. Higher scores reflect higher perceived competency.

2.3.2. Expanded Multidimensional Turnover Intention Scale (EMTIS): developed by Ike et al. [

14], and measures turnover intention across five dimensions: subjective social status, organizational culture, personal orientation, expectations, and career growth. It contains 25 items, rated on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating a higher intention to turnover. Reliability (α = 0.93) and validity have been confirmed [

14]. In this study, both rater groups (managers and staff nurses) rated the same outcome lens—staff nurses’ turnover intention—on EMTIS; higher scores denote stronger perceived intention to leave.

2.3.3. Rater assignment and scoring (study-specific clarification). Nurse managers completed NMCI as self-ratings; staff nurses completed NMCI as ratings of their immediate managers. Both groups completed EMTIS regarding staff nurses’ turnover intention. Domain and total scores were computed as the mean of item responses for each scale/subscale. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was assessed for study scales/subscales prior to analysis.

2.4. Data Collection

Data were gathered using an electronic survey (e-survey) distributed to eligible participants through a secure online platform. Prior to survey administration, several steps were taken to ensure compliance with ethical, legal, and institutional requirements:

2.4.1. Instrument Permission: Approval was obtained from the original authors of the Nurse Manager Competency Inventory (NMCI) and the Expanded Multidimensional Turnover Intention Scale (EMTIS) to use and adapt these tools for the study. Written consent was secured, ensuring adherence to copyright regulations and proper acknowledgment of the instruments’ developers.

2.4.2. Ethical Clearance: Formal approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Health Sciences Colleges Research on Human Subjects, King Saud University, in compliance with national ethical standards for research involving human participants.

2.4.3. Administrative Permissions: Official authorization was obtained from the administration of each participating hospital. The study objectives, methodology, and anticipated benefits were presented to nursing staff and hospital management to secure their cooperation and support during the data collection phase.

Following these approvals, the e-survey was sent to participants meeting the inclusion criteria via email. The invitation included a concise description of the study, assurance of anonymity, and a link to access the survey. Participants were required to provide electronic informed consent before proceeding. To maximize participation, a reminder was sent one week after the initial invitation, encouraging staff nurses to complete the survey and highlighting the importance of their input for improving nursing leadership practices and workforce policies. Separate survey links were used for managers and staff to ensure correct rater assignment; duplicate or incomplete responses were screened and removed according to a pre-specified quality-control protocol.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Health Sciences Colleges Research on Human Subjects, King Saud University (IRB No. E-24-8856 on 26/6/2024). Before participation, informed consent was collected electronically, ensuring that participants were fully informed about the study’s objectives, procedures, and their rights, including the right to withdraw at any time without consequence.

The anonymity and confidentiality of participants were strictly maintained throughout the data collection and analysis process. All data were stored securely and encrypted, with access limited exclusively to the research team. To address the specific ethical considerations of electronic surveys, each participant was assigned a unique identifier, and responses were stored on a secure, cloud-based platform that complies with regional and institutional data protection regulations.

The study adhered to ethical standards consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring the protection of participants and the integrity of the research process. Because both groups rated staff EMTIS, the consent form explicitly clarified the outcome lens and assured participants that responses would be analyzed at the aggregate level only.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics summarized participant demographics, competencies, and turnover intentions. Between-group differences (nurse managers vs. staff nurses) were tested using one-way ANOVA for NMCI domains and for EMTIS (overall and subscales), with two-tailed α = 0.05; assumptions (normality, homogeneity of variances) were evaluated prior to inference. Bivariate associations between perceived competencies and perceived staff nurses’ turnover intention were examined using Pearson’s r (two-tailed), at the domain-to-facet level (NMCI subscales -- EMTIS subscales) and for total scores. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was estimated for all multi-item scales/subscales. Exploratory models considered demographic variables for descriptive context; inferential emphasis remained on (i) cross-rater comparisons and (ii) domain-specific correlations, consistent with the study aims and results.

3. Results

This section presents findings from a dual-rater design in which nurse managers and staff nurses evaluated the same two constructs: (1) nurse-manager competencies (NMCI)—via manager self-ratings and staff nurses’ ratings of their managers—and (2) staff nurses’ turnover intention (EMTIS), as perceived by both rater groups. We first summarize the sample, then report cross-role comparisons for each construct, and finally quantify the bivariate associations between competency domains and perceived turnover intention. Unless otherwise specified, values are reported as mean (SD); group contrasts are tested with one-way ANOVA (two-tailed p < 0.05), and associations are Pearson’s r (two-tailed).

3.1. Perceptions of Nurse-Manager Competencies (NMCI): Nurse Managers’ Self-Ratings vs. Staff Nurses’ Ratings of Their Managers

Given the study’s dual-rater design, we first compared how nurse managers appraised their own competencies and how staff nurses appraised those same managers using the NMCI.

Table 2 reports means and standard deviations for each subscale and the overall score, alongside between-group tests. Because these are two vantage points on the same leadership behaviors, we emphasize both (a) descriptive gaps (what the two groups “see”) and (b) statistical tests (whether those gaps meet conventional significance thresholds).

Across NMCI subscales, nurse managers tended to rate their own competencies higher than staff nurses rated their managers (

Table 2). The largest descriptive gaps appeared for Promote Staff Retention (managers: M = 4.00, SD = 0.75; staff: M = 2.98, SD = 0.85), Recruit Staff (managers: M = 3.98, SD = 0.73; staff: M = 3.00, SD = 0.86), Perform Supervisory Responsibilities (managers: M = 4.08, SD = 0.70; staff: M = 3.23, SD = 0.80), and Facilitate Staff Development (managers: M = 4.07, SD = 0.72; staff: M = 3.43, SD = 0.87). The overall NMCI mean was higher for managers than for staff nurses (3.67 vs. 3.04), but between-group tests were not statistically significant (all p > 0.05; overall: F = 0.114, p = 0.73).

Descriptively larger gaps cluster in retention, recruitment, supervision, and staff development—competencies that are closest to staff nurses’ day-to-day experience of leadership. The absence of significant group differences indicates that, despite visible mean gaps, statistical evidence for role-group separation was not detected at conventional thresholds, consistent with small effects and shared variance across raters.

3.2. Perceptions of Staff Nurses’ Turnover Intention (EMTIS): Nurse Managers vs. Staff Nurses

Both groups rated the staff nurses’ turnover intention using EMTIS. Between-group differences in these perceptions were not statistically significant for any subscale or the overall EMTIS score (e.g., overall: managers M = 3.16, SD = 1.28; staff M = 3.00, SD = 1.15; F = 21.32, p = 0.173; subscales all p > 0.05). Descriptively, managers perceived slightly greater turnover intention than staff on Personal Orientation, Expectations, and Career Development, with very small mean gaps.

Perceptions of staff nurses’ turnover intention were broadly convergent across roles: nurse managers’ and staff nurses’ ratings tracked closely, with only minor descriptive elevation among manager ratings that did not translate into statistically significant differences.

Table 3.

Comparison Between Staff Nurses and Nurse Managers in Relation to Turnover Intention.

Table 3.

Comparison Between Staff Nurses and Nurse Managers in Relation to Turnover Intention.

| Turnover Intention Subscales |

Mean (SD) |

F |

P-value* |

| Nurse Manager |

Staff Nurses |

| Subjective Social Status |

2.34 (1.2) |

2.32 (1,05) |

15.17 |

0.334 |

| Organizational Culture |

2.87 (1.9) |

2.72 (1.25) |

13.43 |

0.293 |

| Personal Orientation |

3.00 (1.4) |

2.88 (1.28) |

14.76 |

0.362 |

| Expectations |

2.98 (1.85) |

2.89 (1.48) |

15.11 |

0.281 |

| Career Development |

3.00 (1.44) |

2.83 (1.69) |

23.21 |

0.621 |

| Overall |

3.16 (1.28) |

3.00 (1.15) |

21.32 |

0.173 |

3.3. Correlations: Perceived Nurse-Manager Competencies vs. Staff Nurses’ Turnover Intention

Higher perceived nurse-manager competencies were generally associated with lower perceived staff nurses’ turnover intention, with small, significant inverse correlations concentrated in human- and development-focused domains: Promote Staff Retention, Recruit Staff, Facilitate Staff Development, Perform Supervisory Responsibilities, Ensure Patient Safety & Quality Care, and Lead Quality Improvement (typical r = − 0.11 to −0.19, p < 0.05). By contrast, Manage Fiscal Planning and Communication showed weaker, non-significant associations. The correlation between the total NMCI and overall EMTIS was small and non-significant (r = − 0.077, p = 0.124), indicating that specific competency domains, rather than a global aggregate, are most informative.

The consistent negative direction across multiple EMTIS facets suggests that staff perceive lower turnover intention where managers are seen as stronger in retention supports, day-to-day supervision, staff development, safety/quality leadership, and quality improvement. The lack of association for fiscal planning and broad communication, and the non-significant global correlation, underscores the domain specificity of the leadership signals most tied to turnover cognitions.

Table 4.

Correlation Between Nurse Manager Competencies and Staff Nurse Turnover Intention.

Table 4.

Correlation Between Nurse Manager Competencies and Staff Nurse Turnover Intention.

| Turnover subscales |

Managers’ competencies subscales |

| Promote Staff Retention |

Recruited Staff |

Facilitate Staff Development |

Perform Supervisory Responsibilities |

Ensure Patient Safety And Quality Care |

Conduct Daily Unit Operations |

Manage Fiscal Planning |

Facilitate Interpersonal, Group And Organizational Communication |

Lead Quality Improvement |

| Subjective Social Status |

r= -.15*

p = .002 |

r= -.14*

p = .007 |

r= -.14*

p = .005 |

r= -.15*

p = .005 |

r= - .12*

p = .01 |

r= - .09

p= .06 |

r= -.05

p = .24 |

r= -.06

p = .23 |

r= -.15*

p =.003 |

| Organizational Culture |

r= -.12*

p = .01 |

r= -.13*

p= .01 |

r= - .14*

p = .02 |

r= - .13*

p = .01 |

r= -.11*

p = .03 |

r= -.10

p =.05 |

r= -.03

p = .58 |

r= -.05

p = .42 |

r= -.13*

p = .01 |

| Personal Orientation |

r= -. 13*

p = .01 |

r= -.13*

p = .008 |

r= -.12*

p= .01 |

r= -.14*

p .007 |

r= -.14*

p = .007 |

r= -.11*

p = .02 |

r= -.05

p = .30 |

r= -. 04

p = .33 |

r= - .12*

p = .02 |

| Expectations |

r= -.13*

p = .01 |

r= -.14*

p= .005 |

r= - .18*

p= .01 |

r= -.14*

p= .006 |

r= -.12*

p = .01 |

R= -.10*

P = .03 |

r= -.04

p = .40 |

r= -.07

P= .16 |

r= - .13*

p = .008 |

| Career Growth |

r= -.19*

p = .01 |

r= -.13*

p = .01 |

r= - .12*

p = .02 |

r= -.13*

p = .01 |

r= -.13*

p = .008 |

r= - .08

p = .09 |

r= -.05

p= .31 |

r= -.08

p = .14 |

r= -.13*

p = .01 |

| |

Total Nurse Manager Competencies |

| Overall Turnover Intention |

r = -.077

p = .124

|

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that competency gaps in nurse leadership have direct and measurable effects on staff nurse turnover intentions. Among the competency domains, deficiencies in staff recruitment, retention strategies, and supervisory responsibilities were the most prominent. These results are congruent with international literature highlighting leadership quality as a key determinant of workforce stability [

1,

7], which found that inadequate managerial competencies were strongly associated with higher turnover intentions, reduced staff morale, and compromised unit performance. Alsadaan et al. and Goens & Giannotti similarly emphasized that transformational and competency-based leadership significantly influences nurses’ job satisfaction, retention, and patient safety outcomes [

1,

15]. Notably, the divergence between raters was comparatively smaller for safety/quality leadership, suggesting this domain may be more standardized and mutually visible in daily work and therefore easier to align through policy, audit, and routine practice [

12,

13]. In contrast, fiscal/operational and development-facing domains displayed the largest descriptive gaps, indicating where targeted leadership development may yield the greatest perceptual realignment [

13,

16].

The comparison between nurse managers’ self-perceptions and staff nurses’ evaluations highlights a critical misalignment, a phenomenon observed globally where managers often overestimate their effectiveness. In practical terms, this misalignment can result in staff nurses feeling unsupported, undervalued, or insufficiently guided, thereby increasing turnover intentions and contributing to chronic staffing challenges. These findings are aligned with Jooste & Cairns, Long & Sochalski, Moradi et al., Abd-Elmoghith & Abd-Elhady, and Perez-Gonzalez et al., who underscored the importance of feedback-informed leadership programs that integrate staff perceptions into competency assessments to identify and address hidden gaps [

12,

13,

17,

18,

19]. Equally important, managers and staff converged in their perceptions of staff nurses’ turnover intention (EMTIS), with no significant differences across the overall score or subscales—reducing concerns about single-source bias for the outcome and reinforcing the salience of the observed leadership gaps as likely antecedents rather than artifacts [

1,

15].

Demographic characteristics appear to influence both the perception of competency gaps and turnover intention, suggesting their potential moderating role. Less experienced nurses and those with higher educational attainment were more likely to detect leadership deficiencies and report higher turnover intentions. This aligns with findings from Falatah and Goens & Giannotti [

1,

3], indicating that novice nurses and highly educated staff may have elevated expectations for leadership support and organizational guidance. Age, experience, and education are therefore important considerations when developing tailored interventions, as these factors can alter the sensitivity to perceived competency gaps and the subsequent decision to remain in a position [

1,

3]. Given these patterns, stratifying leadership development and coaching by unit maturity and staff mix may improve intervention yield [

20,

21,

22].

These findings have critical implications in the context of current healthcare challenges, particularly in post-pandemic environments characterized by staff shortages, high turnover, and increased workload pressures. Ineffective leadership in recruitment and retention contributes to persistent staffing gaps, higher stress among remaining staff, and potential compromises in patient care quality. Globally, healthcare systems are grappling with similar issues, with leadership gaps often undermining workforce resilience, engagement, and retention [

16,

23,

24,

25]. In the Gulf region, including Saudi Arabia, where Vision 2030 emphasizes healthcare transformation and workforce development, these findings highlight the urgent need for structured, competency-based leadership development programs that integrate continuous staff feedback and performance evaluation to enhance retention [

20,

21,

22]. Consistent with our results, the most predictive signals were domain-specific (retention supports, supervision quality, staff development, safety/quality leadership, and quality improvement), whereas the global competency–turnover association was non-significant; thus, dashboards and development plans should prioritize these micro-competencies over composite indices [

13,

16,

20,

21,

22]. Conversely, fiscal planning and broad communication showed weak/variable links with turnover cognitions—plausibly because their effects are distal or contingent on translation into staffing/scheduling fairness—suggesting they require mediating pathways to influence retention [

13,

16].

The study further illuminates current phenomena in healthcare workforce dynamics, such as the high turnover of highly qualified nurses in critical care and high-acuity units. Perceived gaps in supervisory support, recruitment effectiveness, and retention measures contribute to rapid staff turnover, destabilizing teams and threatening patient safety. Addressing these gaps is therefore essential to foster organizational resilience, improve team cohesion, and sustain the quality of care in increasingly demanding healthcare environments.

Regionally, studies have shown that Saudi nurses often face challenges related to limited managerial support, inequitable workload distribution, and insufficient recognition, all of which can heighten turnover intentions. [

26,

27,

28]. Internationally, research in Europe and North America corroborates that perceived leadership deficiencies are associated with burnout, emotional exhaustion, and attrition, emphasizing the global relevance of these findings. [

7,

29,

30]. By identifying specific competency gaps and their differential effects across demographic groups, this study provides evidence-based guidance for leadership development initiatives that are sensitive to workforce composition and expectations. Given that effect sizes in the present study were small but directionally consistent across multiple EMTIS facets, organizations should favor continuous, unit-embedded improvement (e.g., coaching rounds, recognition cadence, structured development planning) over one-off workshops to accumulate impact over time [

20,

21,

22].

Overall, this study underscores the need for targeted leadership interventions that address both skill-based competencies and staff perceptions. Feedback-informed, competency-driven leadership programs, combined with strategic recruitment, retention, and supervision initiatives, can reduce turnover intentions, enhance staff satisfaction, and support workforce sustainability. Tailoring these interventions to the needs of novice, highly educated, or younger nurses may maximize their effectiveness, ultimately contributing to higher organizational performance and better patient outcomes.

4.1. Limitations

Despite the valuable insights gained from this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design constrains the ability to infer causality between nurse manager competencies, perceived competency gaps, and staff nurse turnover intentions. This design prevents the identification of changes over time, such as how perceptions of leadership or turnover intentions might evolve as nurses gain experience, encounter new organizational policies, or face prolonged crises. Future longitudinal studies could provide a more nuanced understanding of these dynamics, offering insight into how leadership perceptions and retention intentions fluctuate across different stages of professional development and organizational change. Additionally, quasi-experimental designs that target specific competency domains (e.g., retention supports, supervision, staff development) and track subsequent changes in EMTIS and observed turnover would more directly test causal pathways [

20,

21,

22,

30].

Second, the study relied on self-reported data, which may be subject to various biases, including social desirability or response bias. Staff nurses and nurse managers might have unintentionally over- or under-reported competencies or perceptions, potentially affecting the accuracy of the findings. Future research could address this limitation by incorporating mixed methods approaches, such as structured interviews, focus groups, or observational assessments, to validate and enrich self-reported data. Our dual-rater design (manager self-ratings and staff ratings of the same managers) partially mitigates single-source bias for competencies and, importantly, both groups rated the same outcome lens (staff EMTIS); nonetheless, role-lens variance remains possible and should be examined with measurement-invariance testing across raters [

12,

15].

Third, the study was conducted in two tertiary governmental hospitals located in Saudi Arabia, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. While these hospitals represent significant clinical settings and provide insight applicable to similar healthcare environments in the region, the results may not fully reflect dynamics in smaller facilities, private hospitals, or healthcare systems in other countries. Expanding the geographic and institutional scope in future research would enhance generalizability and provide broader insights into how organizational structure, resource availability, and regional healthcare policies influence competency gaps and turnover intentions. Multi-site, multi-region sampling with multilevel models (e.g., unit- and hospital-level effects) can clarify contextual influences on leadership-turnover links. [

16,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]

Finally, while the study focused on nurse manager competencies and selected demographic characteristics, other potentially influential factors were not examined in depth. Variables such as organizational culture, staffing ratios, workload, support systems, and external stressors may interact with perceived competency gaps, shaping turnover intentions and staff satisfaction. Future research should explore these additional factors to provide a more holistic understanding of the determinants of nurse retention and workforce stability, particularly in high-pressure or crisis-prone healthcare settings. Future models should also probe mediating pathways that translate distal managerial work (e.g., fiscal planning) into proximal staff experiences (e.g., staffing/scheduling fairness), which may explain the weak/variable direct associations observed for fiscal/communication domains in this study [

13,

16]. Given that effect sizes were small but consistently patterned across EMTIS facets, adequately powered samples and repeated measures will be essential to detect meaningful, domain-specific changes over time [

20,

21,

22].

4.2. Implications and Recommendations

The findings of this study have important implications for nursing practice, healthcare management, education, and future research. They highlight the critical role of nurse leadership competencies in shaping workforce stability and the necessity of addressing gaps to enhance staff retention and patient care quality. Because managers and staff converged on perceived staff turnover intention while diverging on specific competency domains, organizations should prioritize domain-specific leadership improvement (retention supports, supervision quality, staff development, safety/quality leadership, and quality improvement) and de-emphasize reliance on global composite scores that may mask actionable signals [

13,

16,

20,

21,

22,

25]. Continuous, unit-embedded cycles (e.g., coaching rounds, recognition cadence, development planning) are preferable to one-off workshops when effects are small but consistent [

16,

24,

25].

4.2.1. Implications for Nursing Practice

Healthcare organizations should implement structured, competency-based leadership development programs that target the domains identified as gaps in this study, particularly staff recruitment, retention strategies, and supervisory responsibilities. These programs should be tailored to different staff groups, recognizing that novice and highly educated nurses may be more sensitive to leadership deficiencies. Operationalize this targeting with “dual-lens” diagnostics (manager self- vs. staff ratings) and track the gap on priority NMCI domains over time, linking gap-closure to EMTIS indicators and retention KPIs on service dashboards [

20,

21,

22].

Feedback-informed leadership evaluation systems can be instituted, whereby staff nurses’ perceptions are systematically collected and used to guide managerial development. This approach ensures that leadership improvements are aligned with the actual needs and expectations of the nursing workforce. Given the comparatively smaller manager–staff gap on safety/quality leadership, organizations can leverage existing policy/audit routines in this domain as a platform to spread alignment practices to supervision and staff-development routines [

12,

13].

Nurse managers should engage in continuous professional development focused on both technical skills (operational and clinical competencies) and relational skills (communication, mentoring, and motivational leadership), which are essential for fostering a supportive work environment and enhancing nurse satisfaction. Micro-skills should include equitable scheduling checks, structured one-to-one coaching, recognition cadence, and career-growth conversations—behaviors most closely associated with lower turnover cognitions in this study [

16,

20,

21,

22,

25].

4.2.2. Implications for Healthcare Policy

Policymakers can leverage these findings to establish national competency frameworks for nurse managers, integrating standardized assessment, evaluation, and certification processes. Such frameworks will help ensure leadership quality across healthcare institutions and support workforce sustainability in the long term. Frameworks should weight domains with demonstrated relevance to turnover cognitions (retention supports, supervision, staff development, safety/quality leadership, and quality improvement) and require dual-lens measurement as part of accreditation and performance review [

20,

21,

22,

23].

Retention strategies should be context-specific, recognizing differences in workforce demographics. For instance, targeted mentorship and recognition programs for less experienced nurses or newly qualified staff may mitigate turnover risks in critical care and high-acuity units. At the policy level, mandate reporting of unit-level gap metrics (manager–staff) on priority competencies and tie improvement to incentives, thereby aligning governance with workforce sustainability goals [

20,

21,

22].

4.2.3. Implications for Nursing Education

Nursing curricula should incorporate leadership development modules that prepare future nurse managers for the challenges of contemporary healthcare environments, emphasizing practical skills in supervision, retention strategies, and staff recruitment. Embed 360-style feedback and dual-lens audits early in training so that leaders learn to calibrate self-perceptions with staff perceptions and close gaps proactively. [

12,

13,

21]

Simulation-based and scenario-driven training can provide prospective nurse managers with opportunities to practice decision-making, conflict resolution, and team leadership in safe, controlled environments, bridging the gap between theory and real-world practice. Scenario design should mirror the micro-behaviors linked to EMTIS (e.g., coaching a struggling staff nurse, redesigning schedules for fairness, leading a safety huddle) and include structured debriefs tied to NMCI domains [

16,

20,

21,

22,

25].

4.2.4. Implications for Future Research

Future studies should explore the moderating effects of demographic characteristics (age, experience, education) through formal moderated regression analyses to understand how these factors influence the relationship between perceived leadership competency gaps and turnover intention. Cross-level moderation (unit, service line) should be examined using multilevel models to capture contextual influences [

16,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Longitudinal studies are recommended to examine changes in competency perceptions and turnover intention over time, particularly in the context of healthcare transformations or crises such as pandemics. Quasi-experimental trials that intensively develop specific competencies (e.g., supervision or staff development) can test whether improvements produce downstream reductions in EMTIS and actual turnover [

20,

21,

22,

30].

Comparative studies across multiple countries or regions could investigate cultural and organizational influences on leadership perception, competency gaps, and retention outcomes, providing insights for global nursing workforce planning. Future work should also test mediating pathways (e.g., fiscal planning → staffing/scheduling fairness → EMTIS) and assess measurement invariance across rater groups to rule out artifactual differences [

13,

16].

4.2.4. Actionable Recommendations

Develop customized leadership development initiatives focusing on weak competency domains identified in this study. Prioritize retention supports, supervision quality, staff development, safety/quality leadership, and quality improvement over global composite improvements. [

16,

20,

21,

22,

25]

Implement regular staff feedback mechanisms to monitor leadership effectiveness and identify emerging competency gaps. Adopt dual-lens audits (manager self vs. staff ratings) each quarter and set explicit gap-closure thresholds for priority NMCI domains [

20,

21,

22].

Tailor retention strategies considering staff demographics to maximize engagement and reduce turnover risk. Differentiate content and coaching intensity by unit maturity and staff mix (e.g., novice vs. experienced, advanced-degree cohorts) [

1,

3,

20].

Promote a culture of continuous improvement in nurse leadership, integrating evidence-based strategies and benchmarking against best practices both regionally and internationally. Use unit-level dashboards that link NMCI domain gaps to EMTIS indicators and retention KPIs to sustain accountability and focus [

20,

21,

22].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that perceived gaps in nurse leadership competencies are a significant determinant of staff nurse turnover intentions. Deficiencies in recruitment, retention strategies, and supervisory responsibilities emerged as critical areas influencing workforce stability. Furthermore, demographic characteristics such as age, experience, and education may shape staff sensitivity to these gaps, suggesting the need for tailored leadership interventions. Notably, manager–staff divergence was smaller in safety/quality leadership, whereas the most consequential signals for turnover cognitions were domain-specific (retention supports, supervision, staff development, safety/quality leadership, quality improvement). The global competency–turnover association was non-significant, underscoring the value of granular, domain-level measurement and improvement.

Addressing these competency gaps through targeted, evidence-based leadership development programs can enhance staff retention, improve team cohesion, and strengthen workforce sustainability. These interventions are especially important in high-pressure healthcare settings and during periods of systemic transformation, such as those observed in the post-pandemic era. Given the small but patterned effects observed, continuous, unit-embedded improvement—supported by dual-lens measurement and explicit gap-closure targets linked to retention KPIs—offers a pragmatic route to sustained impact.

The findings have both regional and global relevance, informing strategies to optimize nurse leadership effectiveness, reduce turnover, and maintain high-quality patient care. Future research should explore longitudinal changes in perceptions of managerial competencies, examine additional organizational and environmental factors, and evaluate the effectiveness of tailored interventions to ensure the long-term stability and resilience of the nursing workforce. Priority next steps include quasi-experimental evaluations of targeted competency development, multilevel analyses across diverse settings, and mediation tests that connect distal managerial work (e.g., fiscal planning) to proximal staff experiences and retention outcomes.

5.1. What This Paper Added to the Literature/Field

Introduces a dual-rater design on a single outcome lens (EMTIS), reducing single-source bias while revealing manager–staff perceptual gaps in leadership competencies.

Demonstrates that domain-specific (micro-competency) signals—not global competency composites—are the actionable predictors of perceived turnover intention.

Identifies priority competency “pressure points” (retention supports, supervision, staff development, safety/quality leadership, and quality improvement) for precision leadership development.

Shows convergence of manager and staff perceptions on turnover intention, focusing attention on leadership enactment rather than rater artifact.

Provides a practical framework: dual-lens diagnostics, gap-closure targets, and retention-linked dashboards to operationalize leadership improvement in practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A. and D.A.; methodology, H.A.; software, D.A.; validation, H.A. and D.A.; formal analysis, D.A.; investigation, D.A.; resources, D.A.; data curation, H.A..; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing, H.A.; visualization, D.A.; supervision, H.A.; project administration, H.A.; funding acquisition, H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ongoing Research Funding Program for Project number (ORF-FT2025-xxx), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (protocol code XXX and date of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding Program – Fast Track for Project number (ORF-FT2025-xxx), at King Saud University, for supporting this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NMCI |

Nurse Manager Competency Inventory |

| EMTIS |

Expanded Multidimensional Turnover Intention Scale |

| TPB |

Theory of Planned Behavior |

References

References

- Goens, B.; Giannotti, N. Transformational Leadership and Nursing Retention: An Integrative Review. Nursing Research and Practice 2024, 3179141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Tong, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D. A Study on Nurse Manager Competency Model of Tertiary General Hospitals in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 8513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falatah, R. The Impact of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic on Nurses’ Turnover Intention: An Integrative Review. Nursing Reports (Pavia, Italy). 2021, 11, 787–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spetz, J.; Chu, L.; Blash, L. Forecasts of the Registered Nurse Workforce in California. San Francisco, CA: Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, August 2022. Available at: https://www.rn.ca.gov/pdfs/forms/forecast2022.pdf. Accessed August 2025.

- Alasiri, A.A.; Mohammed, V. Healthcare Transformation in Saudi Arabia: An Overview Since the Launch of Vision 2030. Health Services Insights. 2022, 15, 11786329221121214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, Z.A.; Goniewicz, K. Transforming Healthcare in Saudi Arabia: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Vision 2030’s Impact. Sustainability. 2024, 16, Article 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdELhay, E.S.; Taha, S.M.; El-Sayed, M.M.; Helaly, S.H.; AbdELhay, I.S. Nurses’ retention: The impact of transformational leadership, career growth, work well-being, and work-life balance. BMC Nursing. 2025, 24, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R.L. Skills of an Effective Administrator. Harvard Business Review. 1974, 52, 90–102, https://hbr.org/1974/09/skills-of-an-effective-administrator. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics. 1985, 13, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeOnna, J. Developing and Validating an Instrument to Measure the Perceived Job Competencies Linked to Performance and Staff Retention of First-Line Nurse Managers Employed in a Hospital Setting—Blacklight [Dissertation] 2006. https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/catalog/7168.

- Abd-Elmoghith, N.; Abd-Elhady, T. Nurse Managers’ Competencies and its relation to their Leadership Styles. Assiut Scientific Nursing Journal 2021, 9, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Gonzalez, S.; Marques-Sanchez, P.; Pinto-Carral, A.; Gonzalez-Garcia, A.; Liebana-Presa, C.; Benavides, C. Characteristics of leadership competency in nurse managers: A scoping review. Journal of Nursing Management 2024, 5594154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, O.; Ugwu, L.; Enwereuzor, I.; Eze, I.; Omeje, O.; Okonkwo, A. Expanded-multidimensional turnover intentions: Scale development and validation. BMC Psychology 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadaan, N.; Salameh, B.; Reshia, F.A.A.E.; Alruwaili, R.F.; Alruwaili, M.; Awad Ali, S.A.; Alruwaili, A.N.; Hefnawy, G.R.; Alshammari, M.S.S.; Alrumayh, A.G.R.; Alruwaili, A.O.; Jones, L.K. Impact of Nurse Leaders Behaviors on Nursing Staff Performance: A Systematic Review of Literature. Inq. A J. Med. Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2023, 60, 00469580231178528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.A.; Gee, P.M.; Butler, R.J. Impact of nurse burnout on organizational and position turnover. Nursing Outlook. 2021, 69, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jooste, K.; Cairns, L. Comparing nurse managers and nurses’ perceptions of nurses’ self-leadership during capacity building. Journal of Nursing Management. 2014, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, N.H.; Sochalski, J. Discrepancies between supervisor self-evaluations and staff perceptions of leadership: A cross-sectional study in healthcare. BMC Nursing. 2025, 24, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, T.; Mehraban, M.A.; Moeini, M. Comparison of the perceptions of managers and nursing staff toward performance appraisal. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 2017, 22, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mutair, A.; Al Bazroun, M.I.; Almusalami, E.M.; Aljarameez, F.; Alhasawi, A.I.; Alahmed, F.; Saha, C.; Alharbi, H.F.; Ahmed, G.Y. Quality of Nursing Work Life among Nurses in Saudi Arabia: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Nursing Reports (Pavia, Italy) 2022, 12, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, A.; Rasmussen, P.; Magarey, J. Clinical nurse managers’ leadership practices in Saudi Arabian hospitals: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Journal of Nursing Management 2021, 29, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawafi, A.A.; Yahyaei, A.A.; Azri, N.H.A.; Sabei, S.D.A.; Maamari, A.-M.A.; Battashi, H.A.; Ismaili, S.R.A.; Maskari, J.K. A. Bridging the Leadership Gap: Developing a Culturally Adapted Leadership Program for Healthcare Professionals in Oman. Journal of Healthcare Leadership. 2025, 17, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, A.M.; Pascua, G.P.; Alsaleh, S.A.; Sabry, W.; Ahajan, S.N.; Abdulla, J.; Abdulalim, A.; Salih, S.S. Factors Influencing Nurses Turnover in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. Nursing Forum 2024, 4987339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-Y.; Sunaryo, E.Y.A.B.; Kristamuliana, K.; Lee, H.-F.; Chen, C.-M. Factors influencing nurses’ turnover: An umbrella review. Nursing Outlook. 2025, 73, 102464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattali, S.; Sankar, J.P.; Al Qahtani, H.; Menon, N.; Faizal, S. Effect of leadership styles on turnover intention among staff nurses in private hospitals: The moderating effect of perceived organizational support. BMC Health Services Research. 2024, 24, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alilyyani, B.; Althobaiti, E.; Al-Talhi, M.; Almalki, T.; Alharthy, T.; Alnefaie, M.; Talbi, H.; Abuzaid, A. Nursing experience and leadership skills among staff nurses and intern nursing students in Saudi Arabia: A mixed methods study. BMC Nursing. 2024, 23, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, M.J.; Bindahmsh, A.A.; Baker, O.G.; Alaqlan, A.; Almotairi, S.M.; Elmohandis, Z.E.; Qasem, M.N.; AlTmaizy, H.M.; du Preez, S.E.; Alrafidi, R.A.; Alshodukhi, A.M.; Al Nami, F.N.; Abuzir, B.M. Burnout combating strategies, triggers, implications, and self-coping mechanisms among nurses working in Saudi Arabia: A multicenter, mixed methods study. BMC Nursing. 2025, 24, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, Z.T.; Aslanoğlu, A.; Elshatarat, R.A.; Al-Za’areer, M.S.; Almagharbeh, W.T.; Alhejaili, A.A.; Alhumaidi, B.N.; Al-Akash, H.Y.; Al-Momani, M.M.; Alfanash, H.A.; Alasmari, A.A. Exploring the reasons and significant influencing factors of serious turnover intentions among nurses in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2025, 14, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, R.; Smith, P. Global nursing workforce challenges: Time for a paradigm shift. Nurse Education in Practice. 2023, 69, 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofei, A.M.A.; Poku, C.A.; Paarima, Y.; Barnes, T.; Kwashie, A.A. Toxic leadership behaviour of nurse managers and turnover intentions: The mediating role of job satisfaction. BMC Nursing. 2023, 22, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).